Abstract

The pore complexity and heterogeneity in porous media display obvious fractal characteristics, which can be characterized by the fractal dimension for the pore tortuosity (DT) and the fractal dimension for the pore size (Df). Correspondingly, a three-dimensional (3D) fractal permeability model for porous media is proposed based on the DT and Df. The accuracy of the proposed model is verified by the classical theoretical relation of the permeability versus porosity, the measured permeability, and the previous study. The sensitivity analysis of model parameters (Df, DT, λmin and λmax) based on elasticity coefficient indicates that the proposed model is much more sensitive to Df and DT than λmin and λmax, and more sensitive to Df than DT. The proposed model is much more sensitive to λmin than λmax. Furthermore, the proposed model is compared with the modified Kozeny–Carman equation. The root mean square error (RMSE) analysis shows that the RMSE of the proposed model and the modified Kozeny–Carman equation in predicting permeability are 8.9857 × 10−4 and 0.5082, exhibiting high prediction accuracy of the proposed model. The proposed fractal permeability model achieves a more accurate characterization of the fluid transport by more comprehensively describing the complexity and tortuosity of pore structure, which can also provide the prospective theoretical significance and method reference for predicting the permeability of 3D porous media.

1. Introduction

The pore structure characteristics in porous media influence the transport and mass transfer behavior of fluids, and the permeability is one of the critical quantitative parameters for characterizing fluid transport and mass transfer in porous media [1]. The theoretical achievements of permeability were obtained by the traditional Euclidean geometry to depict the flow and macroscopic transport characteristics of porous media with simple and regular microstructures [2,3]. However, the above achievements fail to accurately match the complexity and heterogeneity of the pore structure distribution in irregular/disordered porous media in actual situations [4,5]. Therefore, accurate analysis and characterization of the heterogeneity and complexity of pore structure in porous media are key to effectively improving the permeability models.

According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) pore classification, the pores of porous media can be divided into micropores (<2 nm), mesopores (2–50 nm), and macropores (>50 nm) [6]. The impact of pore structures at different scales on gas transport behavior varies. Micropores have a high specific surface area, which mainly influences gas adsorption [7,8,9]. Mesopores, as the intermediate structure connecting micropores and macropores, mainly affect gas desorption–diffusion behavior [10,11], while macropores mainly affect gas seepage behavior [12,13]. Related studies have indicated that the complexity and heterogeneity of multi-scale pore structure is reflected in the irregularity of pore morphology [14,15], the heterogeneous distribution of pore number and size, the tortuosity of pore structure [16,17], etc. Furthermore, the complexity and heterogeneity of the pore structure display the obvious fractal characteristics on pore size and pore tortuosity [18,19], which can be described by the fractal dimension for the pore size (Df) and the fractal dimension for pore tortuosity (DT), respectively [20,21]. For the fractal dimension of the pore size (Df) in porous media, the box dimension theory is a commonly used fundamental theory for calculating the fractal dimension (Df) [22,23]. For example, the fractal Menger sponge model is mainly used for calculating the fractal dimension (Df) of macropore size distribution (>50 nm) in high-pressure mercury intrusion characterization, including sandstone [24], coal [25], and shale [26]. The Frenkel–Halsey–Hill (FHH) fractal model shows good adaptability with the low-temperature nitrogen adsorption test, which is mainly used for fractal research on mesopore (2–50 nm) structures’ distribution in adsorbent materials, such as graphene [27], coal [28], and activated carbon [29]. Jaroniec et al. derived a fractal calculation model for micropore (<2 nm) structures’ distribution [30], which shows the good adaptability with the low-temperature CO2 adsorption test [31]. For the fractal dimension for pore tortuosity (DT) in porous media, Wheatcraft and Tyler developed a fractal tortuosity relationship (LT(ε) = ε1−DTL0DT) for flow through heterogeneous media [32]. Furthermore, Yu et al. found that the diameter of capillary pore is similar to the length scale ε, and established a fractal quantitative relationship of tortuosity between capillary pore diameter and length [33], which achieved effective calculation of the fractal dimension for pore tortuosity (DT). Yun and Yu et al. further comprehensively reviewed the tortuosity fractal dimension DT, 1 < DT < 2 in two dimensions and 1 < DT < 3 in three dimensions [34,35]. They found that the tortuosity fractal dimension decreases with the increase in porosity, and DT = 1 represents a straight capillary. When porosity is unity, there is no solid particle in a volume and the streamlines are straight and thus DT = 1. A higher value of DT corresponds to a highly tortuous capillary. DT = 2 or 3 corresponds to a highly tortuous line that fills a two-dimensional plane or a three-dimensional space, respectively.

Accordingly, the two-dimensional (2D) fractal permeability models on porous media have been derived based on the fractal dimension Df (1 < Df < 2) and DT (1 < DT < 2), achieving a breakthrough in the characterization of fluid transport in the 2D plane porous media [33,34,35]. Actually, the pore in porous media displays obvious three-dimensional (3D) structure characteristics, and the pore size fractal dimension and pore tortuosity fractal dimension are 2 < Df < 3 and 1 < DT < 3, respectively [36,37]. Therefore, Pape et al. established the modified Kozeny–Carman (KC) equation based on the fractal dimension for the pore size (Df) [38], which was applied to predict the permeability of sandstone and coal reservoirs [39,40,41]. However, the above modified KC equation has empirical parameters and does not fully consider the impact of pore tortuosity on permeability.

Given that establishing a fluid transport model based on fractal dimensions Df and DT can better characterize fluid transport and mass transfer behavior in porous media. It is worth further exploring a 3D improved fractal permeability model based on the fractal dimensions for pore size (Df) (2 < Df < 3) and for pore tortuosity (DT) (1 < DT < 3). Therefore, we propose a 3D fractal permeability model for porous media based on the fractal dimensions for pore size (Df) and for pore tortuosity (DT) in this study. The accuracy of the proposed model is verified by the measured permeability on sandstone as a classical porous medium and the relation of the permeability versus porosity. The proposed fractal permeability model is compared with the modified Kozeny–Carman equation based on the fractal dimension for pore size (Df), which accurately characterizes the fluid transport and mass transfer in sandstone porous media. Ultimately, the proposed 3D fractal permeability model can provide the prospective theoretical significance and method reference for predicting the permeability of 3D porous media.

2. Principle and Methodology

2.1. Principle

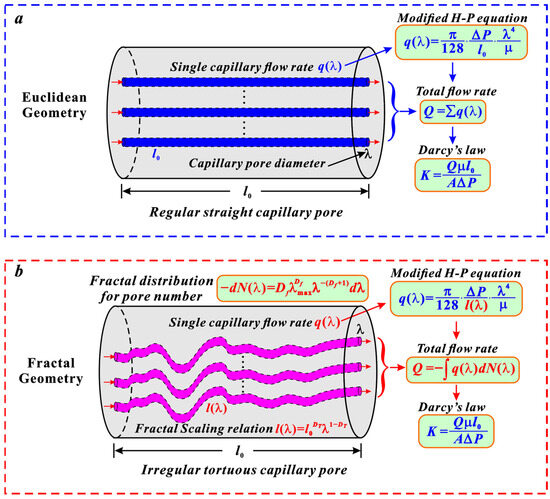

Figure 1a shows the calculation principle for the permeability of regular straight capillary pores in Euclidean geometry. The flow rate q(λ) in a single regular straight capillary pore can be calculated by the Hagen–Poiseuille (H-P) equation, as shown in previous studies [42,43]. However, the traditional Euclidean geometry fails to characterize the fluid transport in irregular tortuous capillary pores due to the fractal characteristics in its size/number distribution and tortuosity.

Figure 1.

Principle of the fractal permeability model on porous media: (a) seepage behavior in regular straight capillary pores, (b) seepage behavior in irregular tortuous capillary pores.

Figure 1b displays the principle of the fractal permeability model based on the fractal dimension Df and DT for porous media. The distribution of irregular tortuous capillary pores in porous media satisfies the fractal scaling relation l(λ) that is a function of the fractal dimension DT (Figure 1b). The pore number fractal distribution −dN(λ) can be described by the fractal dimension Df. Therefore, the flow rate q(λ) through a single irregular tortuous capillary pore can be described by the modified Hagen–Poiseuille (H-P) equation and the fractal scaling relationship l(λ). Further, the total flow rate Q through the entire porous medium can be achieved by integrating the flow rate q(λ) and the fractal distribution for the pore number −dN(λ). Finally, the fractal permeability model based on the fractal dimensions Df and DT can be obtained by inserting the total flow rate Q into the Darcy law.

2.2. Methodology

The Hagen–Poiseuille (H-P) equation is commonly used to describe the characteristics of fluid flow in pipelines [44]. According to the principle of the fractal permeability model for porous media (Figure 1), the flow rate q(λ) through a single tortuous capillary can be described by the modified Hagen–Poiseuille (H-P) equation by Yu and Cheng [33], as shown in Equation (1).

where λ is the diameter of a single capillary pore; l(λ) is the actual length of a tortuous capillary pore; and μ is the fluid viscosity, which reflects the interaction forces between fluid molecules. The higher the viscosity, the more difficult the fluid flow, exhibiting stronger internal friction; ∆P is the pressure gradient.

The actual length l(λ) of a tortuous capillary pore can be determined by a fractal scaling relationship between the diameter and length of the porous media [33], as shown in Equation (2).

where l(λ) is the actual length of a tortuous capillary pore; DT is the fractal dimension pore tortuosity in 3D space porous media with a range of 1 < DT < 3; and l0 is the straight length of porous media.

Therefore, the flow rate q(λ) through a single tortuous capillary can be calculated by inserting Equation (2) into Equation (1), as shown in Equation (3) [33].

Furthermore, the total flow rate Q can be calculated by integrating the single tortuous capillary flow rate q(λ) over the cumulative number of pores from the minimum pore diameter λmin to the maximum pore diameter λmax in a unit cell, as shown by Equation (4) [33].

The cumulative number of pores in Equation (4) of a pore diameter range of λ to λ + dλ in porous media can be expressed as follows [33].

where λmax is the maximum pore diameter and Df is the pore fractal dimension in the 3D space with a range of 2 < Df < 3.

Therefore, the total flow rate Q is shown as Equation (6) by inserting Equations (3) and (5) into Equation (4) [33].

Since 2 < Df < 3, λmin/λmax~10−2, and (λmin/λmax)Df ≈ 0, (λmin/λmax)3+DT−2Df > 0. Therefore, Equation (6) can be reduced to Equation (7) [33].

According to the Darcy law, the expression for the permeability in porous media is calculated in Equation (8) [33], and the unit of permeability is μm2.

When the fluid passes through the porous media with a cross-sectional area of A and a length of l0, the porosity φ of the porous media can be determined by the ratio of VP to Vm, as shown in Equation (9).

where φ is the porosity of porous media; VP is the total pore volume in porous media; Vm is the porous media volume; and A and l0 are the cross-sectional area and the length of the porous media, respectively.

The total pore volume in Equation (9) of the fractal tortuous capillary in porous media can be integrated by combining Equations (2) and (5), as shown in Equation (10) [45].

The porosity ϕ of the porous media can be calculated by inserting Equation (10) into Equation (9), as shown in Equation (11).

The porosity φ of a 3D fractal porous medium can also be obtained as Equation (12) [36].

By integrating Equations (11) and (12), the cross-sectional area A of porous media can be estimated by Equation (13).

Finally, by inserting the cross-sectional area A of porous media (Equation (13)) into Equation (8), the fractal permeability calculation model for porous media can be obtained, as shown Equation (14), which indicates the permeability is a function of the fractal dimensions Df and DT and the structural parameters (l0, λmin and λmax).

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Samples

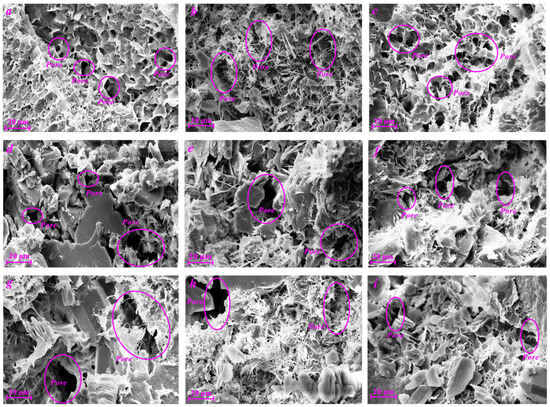

A total of 9 sandstone samples with no obvious fractures were collected from the Linxing Block in the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin, China. For each sandstone sample, a horizontal core column 25 mm in diameter and 50 mm in height was prepared by linear cutting. The 9 core columns were numbered with LX1, LX2, …, LX8, LX9. These core columns are used for permeability measurement and high-pressure mercury intrusion. Figure 2 shows the scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the selected sandstone samples LX1, LX2, …, LX8, LX9. Compared with previous studies on sandstone pores by SEM [46], the pores in sandstone are mainly intergranular pores. In addition, the pores in Figure 2 display the obvious irregularity and tortuosity.

Figure 2.

SEM images of selected sandstone samples: (a) LX1, (b) LX2, (c) LX3, (d) LX4, (e) LX5, (f) LX6, (g) LX7, (h) LX8, (i) LX9.

3.2. Permeability Measurement

The coal/rock permeability measurement device is employed to perform the permeability measurement of the sandstone samples in the Collaborative Innovation Center of Coalbed Methane and Shale Gas for Central Plains Economic Region. The apparatus consists of a pressure system, a sample holder, a gas flowmeter, a loading pump, and a computerized system for process control and data acquisition. The core column samples were dried in a drying oven at 70 °C for 24 h and vacuumed for 8 h to prepare for permeability measurements. Then the column sample was placed into the sample holder connected to a pressurized helium cylinder. Before the permeability test, all the joints, valves, pipelines, and core holder were checked with helium to ensure that the entire apparatus was well sealed with no gas leakage. The measurements were performed with a confining pressure of 2.75 MPa and a helium pressure of 2.50 MPa, and the permeability test error of this permeability measurement device is ±0.001 mD.

3.3. Measurement of High-Pressure Mercury Intrusion

The high-pressure mercury intrusion is a widely used method for obtaining the pore structure parameters, and its main principle is to analyze the pore distribution with the help of the Washburn equation [47], as shown Equation (15). The high-pressure mercury intrusion measurement of the sandstone samples was carried out under the standard ISO 15901-1:2016 [48]. The experimental instrument is the American AutoPore IV9505 mercury intrusion porosimeter, with a maximum experimental pressure of 200 MPa. The pore size range for AutoPore IV9505 mercury intrusion porosimeter testing is usually between 0.003 μm and 100 μm. According to the measurement data of high-pressure mercury intrusion, the pore structure parameters can be derived, including pore radius/diameter, pore volume, pore surface area, and pore size distribution, which are the crucial parameter to calculate the fractal dimensions Df and DT for sandstone in the 3D space.

where P is the mercury intrusion pressure, r is the pore radius when mercury enters at the pressure P, θ is the contact angle, and σ is the interfacial tension of the mercury.

3.4. Calculation of Pore Fractal Dimension Df

According to the Washburn equation and fractal sponge model, the relationship between the cumulative mercury intrusion volume, mercury intrusion pressure, and fractal dimension Df of sandstone can be described as shown Equation (16) [49,50].

where V is the cumulative volume of mercury intrusion at a pressure P and Df is the pore fractal dimension by mercury intrusion data.

3.5. Calculation of Pore Tortuosity Fractal Dimension DT

The pore tortuosity fractal dimension DT can be estimated by the average pore diameter λav and the average capillary tortuosity τav from the high-pressure mercury intrusion data, which is shown in Equation (17) [51].

The average pore diameter λav in Equation (17) can be obtained by Equation (18) [52].

where λav is the average pore diameter; Df is the pore fractal dimension; and λmin and λmax are the minimum and maximum pore diameter, respectively.

Furthermore, the average tortuosity τav in Equation (17) is the function of the porosity of porous media, as shown Equation (19) [53].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Estimation of Fractal Dimension for Pore Structure

4.1.1. Estimation of Fractal Dimension Df for Pore Size

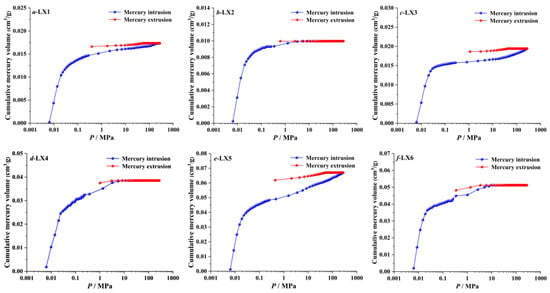

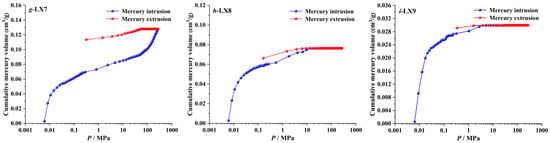

Figure 3 shows the curves of the mercury intrusion–extrusion for the nine sandstone samples. As the mercury injection pressure increases, the cumulative mercury intrusion volume continues to increase, and the final cumulative mercury intrusion volume reflects the development of pores in the porous media. The larger the cumulative mercury intrusion volume, the more developed the pores in the sandstone. Significantly, the mercury intrusion data is the basis for calculating the fractal dimension (Df and DT) of pore structure. According to Figure 3 and Equation (16), the relation between log(dV/dP) and log P of nine sandstone samples is fitted, which is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Curves of the mercury intrusion–extrusion of samples (a) LX1, (b) LX2, (c) LX3, (d) LX4, (e) LX5, (f) LX6, (g) LX7, (h) LX8, (i) LX9.

Figure 4.

Calculation for fractal dimension Df of samples (a) LX1, (b) LX2, (c) LX3, (d) LX4, (e) LX5, (f) LX6, (g) LX7, (h) LX8, (i) LX9.

Figure 4 displays the relation of log(dV/dP) and log P can be well fitted by Equation (16) from the high-pressure mercury intrusion data, and the correlation coefficient (R2) is greater than 0.90. The fractal dimension Df for the pore size of the samples ranges from 2.4211 to 2.7861. According to Figure 3 and Figure 4, we can obtain the maximum pore diameter λmax, minimum pore diameter λmin, and fractal dimension Df of the samples, as shown in Table 1. These are the crucial parameters for calculating the permeability of samples by Equation (14).

Table 1.

The basic fractal parameters of the samples.

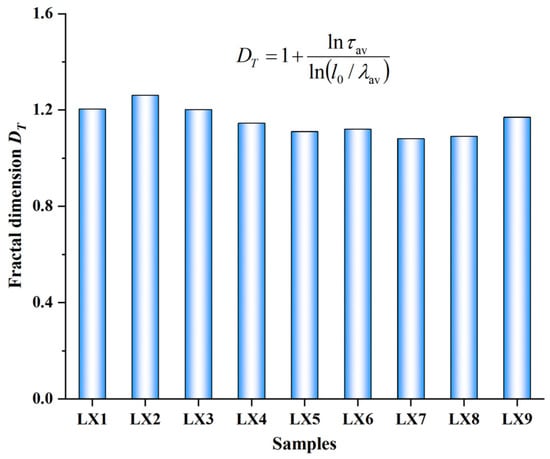

4.1.2. Estimation of Pore Tortuosity Fractal Dimension DT

The porosity of the pore fractal region from the high-pressure mercury intrusion is taken into Equation (19) to obtain the pore average tortuosity (τav). The average pore diameter (λav) can be obtained by inserting the parameters (maximum pore diameter λmax, minimum pore diameter λmin, and fractal dimension Df) in Table 1 into Equation (18). The pore tortuosity fractal dimension DT can be calculated by introducing the basic parameters (l0, τav, λav) into Equation (17). Table 2 and Figure 5 display that the pore tortuosity fractal dimension DT of the samples, which ranges from 1.0813 to 1.2611. The larger the pore tortuosity fractal dimension DT the more tortuous the pore structure is, which is not conducive to fluid transportation.

Table 2.

The basic parameters for calculating pore tortuosity fractal dimension DT.

Figure 5.

Pore tortuosity fractal dimension DT of samples.

4.2. Model Accuracy Analysis

4.2.1. Model Accuracy Analysis from the Theoretical Relation of the Permeability and Porosity

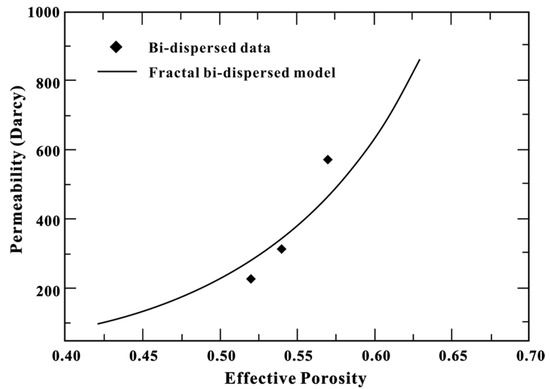

Figure 6 displays the theoretical relation of permeability and porosity that was demonstrated in the study of Yu et al. [33]. Inspired by this, we carried out the model accuracy analysis from the theoretical relation of the permeability and porosity, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

The relation of permeability and porosity from the fractal model and experimental data. [33].

Figure 7.

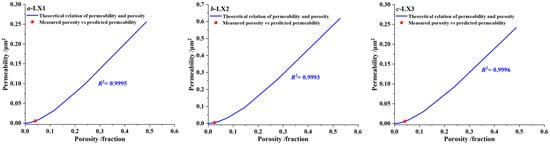

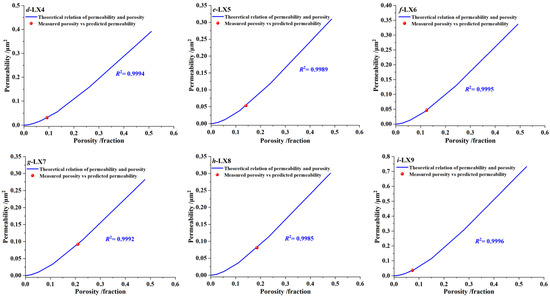

Permeability vs. the porosity: (a) LX1, (b) LX2, (c) LX3, (d) LX4, (e) LX5, (f) LX6, (g) LX7, (h) LX8, (i) LX9.

The procedures for the theoretical relation of the permeability and porosity in Figure 7 are as follows: (a) obtain the pore scale parameters (λmin and λmax) of samples in Table 1, and calculate the theoretical porosity with different setting values of Df using Equation (12); (b) estimate the theoretical pore tortuosity fractal dimension DT using Equations (17)–(19) and the parameters (Df, l0, ϕ, λmin and λmax); (c) insert the parameters (Df, DT, λmin, λmax and l0) into Equation (14) to obtain the theoretical relation of permeability and porosity. Figure 7 indicates that the measured porosity from Section 3.3 vs. predicted permeability (red dot) of all the samples satisfies the theoretical relation of permeability and porosity (blue line), which further reflects the high accuracy of the proposed fractal permeability model Equation (14).

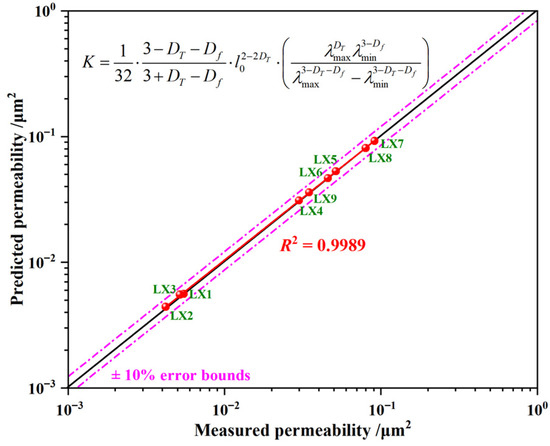

4.2.2. Model Accuracy Analysis from the Measured Permeability

As shown in Figure 8, the measured permeability from Section 3.2 of the sandstone samples ranged from 0.0044 to 0.0919 μm2, which is consistent with the previous study indicating that the permeability values of the sandstone in Linxing block are mainly distributed from 9.8692 × 10−7 to 0.0987 μm2 [54]. Furthermore, the predicted and the measured permeability values fall on the y = x line, indicating the predicted permeability values from Equation (14) are in good agreement with that of the measured permeability. Therefore, it can be concluded that the proposed fractal permeability model can accurately predict the permeability values.

Figure 8.

Comparison between measured and predicted permeability for Linxing sandstone samples.

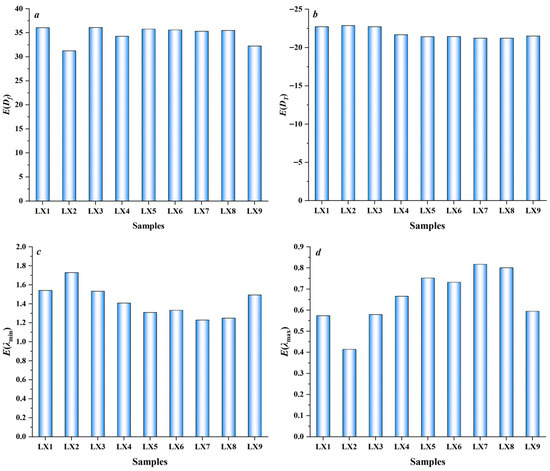

4.2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of the Influence of Model Parameters on Permeability

According to Equation (14), the parameters (Df, DT, λmin, and λmax) are key factors that affect permeability. To further analyze the impact of the above parameters on permeability, sensitivity analysis is conducted using the elastic coefficient E(x), as shown in Equation (20). When the E(x) is greater than 0, indicating a positive correlation between two variables, the E(x) is less than 0, indicating a negative correlation between two variables. The larger the absolute value of the E(x), the more sensitive the dependent variable f(x) is to the independent variable x. The sensitivity analysis process of the above parameters (Df, DT, λmin, and λmax) is as follows: fixing the other three parameters, increasing another parameter by 1%, and using Equation (20) to calculate the E(x) of the parameter.

The elasticity coefficient E(x) of model parameters (Df, DT, λmin, and λmax) of the influence on permeability is shown as Figure 9. The elasticity coefficient E(x) of the model parameters Df of the samples LX1, LX2, …, LX8, LX9 ranges from 31.2275 to 36.0694 (Figure 9a), with an average value of 34.6537. The elasticity coefficient E(x) of model parameters DT of the samples LX1, LX2, …, LX8, LX9 ranges from −22.8702 to −21.2212 (Figure 9b), with an average value of −21.8682. The elasticity coefficient E(x) of model parameters DT is a negative value, which indicates that permeability decreases with the increase in DT. The elasticity coefficient E(x) of model parameters λmin of the samples LX1, LX2, …, LX8, LX9 ranges from 1.2286 to 1.7288 (Figure 9c), with a average value 1.4250. The elasticity coefficient E(x) of model parameters λmax of the samples LX1, LX2, …, LX8, LX9 ranges from 0.4142 to 0.8173 (Figure 9d), with a average value 0.6590. The comparison of the absolute values of the average sensitivity coefficients of model parameters (Df, DT, λmin and λmax) shows that the proposed model is much more sensitive to Df and DT than λmin and λmax, and more sensitive to Df than DT. The proposed model is much more sensitive to λmin than λmax.

where E(x) is elasticity coefficient for sensitivity analysis. f(x1) is a dependent variable when the independent variable is x1. f(x0) is a dependent variable when the independent variable is x0.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis of model parameters (Df, DT, λmin and λmax) of the influence on permeability: (a) parameter Df, (b) parameter DT, (c) parameter λmin, (d) parameter λmax.

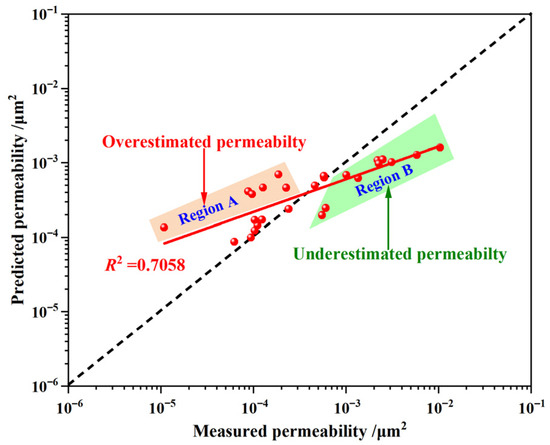

4.2.4. Comparison with the Measured Permeability from the Previous Study

The proposed model in Equation (14) has been further analyzed by predicting sandstone permeability on the Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin of China, from the previous study [55]. The predicted permeability and the measured permeability is shown in Figure 10. The root mean square error (RMSE) is used to analyze the error of the proposed model in predicting permeability, and the RMSE of the proposed model in predicting permeability is 2.0434 × 10−3, which indicates the predicted values of sandstone permeability from Equation (14) display an overall consistent variation trend with that of the measured sandstone permeability from the previous study [55]. Figure 10 also indicates the phenomenon of the overestimated permeability (Region A) and underestimated permeability (Region B). The reason is that we adopted the pore diameter 100 nm (0.1 μm) as the minimum pore diameter (λmin) in this permeability prediction, due to the fact that the minimum pore diameter (λmin) in the pore fractal region is not given in Wang’s study [55]. Although the pore diameter 100 nm is widely accepted as the lower bound of the seepage pore range [12,56,57,58,59], it needs the determined values of the minimum pore diameters. Therefore, the accuracy of predicting permeability by Equation (14) can be improved by obtaining the accurate value of the minimum pore diameter in applications.

where RMSE is the root mean squared error, n is the sample number, ym is the measured value, and yp is the predicted value.

Figure 10.

Predicted permeability from Equation (14) vs. the measured permeability from the previous study [55].

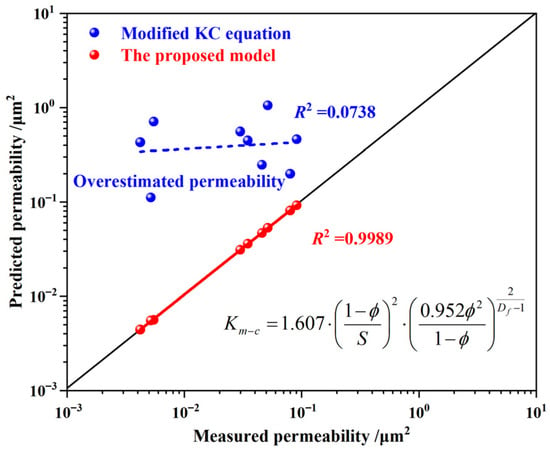

4.2.5. Comparison with the Modified Kozeny–Carman Equation

According to the Kozeny–Carman (KC) equation and the grain packing model with fractal pore space geometry, the modified KC equation in Equation (22) was proposed by Pape et al. [38]. The model was applied to predict the permeability of sandstone and coal reservoirs [39,40,41].

where rg is the average grain radius, τ is the tortuosity, ϕ is the porosity of porous media, and Df is the pore fractal dimension for pore size.

The ratio of the tortuosity τ to the porosity ϕ of porous media is given by Archie’s first law [60], as shown in Equation (23). On average, a = 0.7 and m = 2 for sandstone.

The average grain radius rg can be determined by the specific surface S and porosity ϕ of porous media in the following Equation (24) [39,40,41].

Therefore, the modified KC equation in Equation (25) can be obtained by inserting Equations (23) and (24) into Equation (22), which is a function of the fractal dimension Df, porosity ϕ and specific surface S.

The specific surfaces of the nine sandstone samples from the high-pressure mercury intrusion are shown in Table 3. The sandstone permeability predicted by the modified KC equation can be obtained by substituting the parameters in Table 2 and Table 3 into Equation (25).

Table 3.

The specific surface of the sandstone samples.

Figure 11 shows that the relation between the predicted permeability and the measured permeability from Section 3.2 is parallel to the line y = x, but the predicted values from Equation (25) are greater than the measured values, indicating that the permeability values predicted by Equation (25) overestimate the permeability compared with the measured values. The overestimated permeability is due to that the fractal dimension Df in Equation (25) reflects the complexity of the distribution of pore size and number, and a = 0.7 and m = 2 in Equation (23) are the average values for calculating the pore tortuosity τ of sandstone, which result in poor adaptability and universality of the calculated pore tortuosity for the diverse porous media. The related studies indicate that the fluid transport capacity is negatively correlated with pore tortuosity [61], and the calculation of pore tortuosity fractal dimension DT in Section 3.4 does not have empirical parameters, which can effectively reflect the pore structure tortuosity in porous media from a fractal perspective. Moreover, Equation (25) contains two fitting constants (1.607 and 0.957), which make Equation (25) a less scientific mechanism and less adaptable for predicting the permeability of different sandstone reservoirs. Therefore, the above analysis indicates that Equation (14) can better characterize the actual fluid transport in the fractal porous media by comprehensively describing the complexity and tortuosity of pore structure.

Figure 11.

Predicted permeability from Equation (25) vs. measured permeability from Section 3.2.

Furthermore, the root mean square error (RMSE) from Equation (21) is applied to quantify the error of the proposed model and the modified KC equation in predicting permeability. According to the measured permeability of sandstone samples and the predicted permeability from the proposed model and the modified KC equation, the RMSE of the proposed model in predicting permeability is 8.9857 × 10−4, and the RMSE of the modified KC equation in predicting permeability is 0.5082. The RMSE generated by the proposed model in predicting permeability is significantly smaller than that of the modified KC equation, further demonstrating that the proposed model has high accuracy in predicting permeability.

4.3. Implications

The core implications and application of this proposed fractal permeability model focus on the quantitative characterization and prediction of permeability in complex porous media, especially in the study of unconventional reservoirs such as sandstone reservoirs, which have irreplaceable advantages.

The application scenarios of the proposed model can be extended from basic theoretical research (correlation between microstructure and seepage mechanism) to engineering practice (production capacity prediction, and unconventional oil and gas development plan optimization), and gradually integrated deeply with multi-field coupling and multi-process collaboration (adsorption-diffusion-seepage), providing important theoretical tools and technical support for the efficient development of unconventional oil and gas resources.

Future research hotspots can focus on the construction of multifractal permeability models, the dynamic fractal dimension coupling mechanisms, the model optimization under multi-field coupling, and the fractal permeability model coupled pore and fracture dual-porosity systems, further enhancing their applicability in complex development scenarios.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a novel fractal permeability prediction model for porous media was proposed. The conclusions are summarized as follows:

(1) A 3D fractal permeability prediction model for porous media was proposed, and the principle and methodology for this model were derived and summarized in detail. The accuracy of the proposed model was analyzed and verified by the classical theoretical relation of the permeability versus porosity and the measured permeability.

(2) According to the sensitivity analysis of model parameters (Df, DT, λmin and λmax), the proposed model is much more sensitive to Df and DT than λmin and λmax and more sensitive to Df than DT. The proposed model is much more sensitive to λmin than λmax.

(3) The proposed fractal permeability model is compared with the modified Kozeny–Carman equation, exhibiting high permeability prediction accuracy, which reflects that comprehensively considering the fractal characteristics of pore structure can more accurately predict permeability.

(4) The proposed fractal permeability can provide the important theoretical tools and technical support for predicting the permeability of 3D fractal porous media, such as sandstone reservoirs. The future research can focus on the construction of multifractal permeability models, the dynamic fractal dimension coupling mechanisms, the model optimization under multi-field coupling, and the fractal permeability model coupled pore and fracture dual-porosity systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z., G.L. and P.C.; methodology, Z.Z., Y.H., H.L., X.W., G.B. and P.C.; formal analysis, Z.Z., Y.H., H.L., X.W. and G.B.; data curation, Z.Z., Y.H., H.L., X.W. and G.B.; writing—original draft, Z.Z. and G.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z. and G.L.; supervision, G.L.; funding acquisition, Z.Z. and G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Taiyuan University of Science and Technology Scientific Research Initial Funding (20252100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42230814 and No. 42372204), and the China Scholarship Council (No. 202308410549).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations and Symbols

| Df | fractal dimension for the pore size |

| DT | fractal dimension for the pore tortuosity |

| q(λ) | flow rate |

| λ | pore diameter |

| l(λ) | actual length of a tortuous capillary pore |

| μ | fluid viscosity |

| ∆P | pressure gradient |

| l0 | straight length of porous media |

| Q | total flow rate |

| −dN(λ) | cumulative number of pores of a pore diameter range of λ to λ + dλ in porous media |

| λmax | maximum pore diameter |

| λmin | minimum pore diameter |

| K | permeability from proposed model |

| A | cross-sectional area |

| ϕ | porosity of porous media |

| VP | total pore volume in porous media |

| Vm | porous media volume |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

| P | mercury intrusion pressure |

| r | pore radius when mercury enters at the pressure P |

| θ | contact angle |

| σ | interfacial tension of the mercury |

| λav | average pore diameter |

| τav | average capillary tortuosity |

| E(x) | elasticity coefficient for sensitivity analysis |

| Km−c | permeability from modified Kozeny–Carman equation |

| rg | average grain radius |

| τ | tortuosity |

| S | specific surface |

| RMSE | root mean square erro |

| n | sample number |

| ym | measured value |

| yp | predicted value |

References

- Pan, Z.; Connell, L.D. Modelling permeability for coal reservoirs: A review of analytical models and testing data. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 92, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrava, S.; Tahmasebi, P.; Sahimi, M. Linking morphology of porous media to their macroscopic permeability by deep learning. Transp. Porous Media 2020, 131, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Mohanty, K. Permeability of spatially correlated porous media. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2000, 55, 5393–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Anna, P.; Quaife, B.; Biros, G.; Juanes, R. Prediction of the low-velocity distribution from the pore structure in simple porous media. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2017, 2, 124103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommel, J.; Coltman, E.; Class, H. Porosity–permeability relations for evolving pore space: A review with a focus on (bio-) geochemically altered porous media. Transp. Porous Media 2018, 124, 589–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, J.; Baron, G.; Denoyel, R.; Giesche, H.; Groen, J.; Klobes, P.; Levitz, P.; Neimark, A.V.; Rigby, S.; Skudas, R. Liquid intrusion and alternative methods for the characterization of macroporous materials (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2012, 84, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, X. Effect of pore characteristics on coalbed methane adsorption in middle-high rank coals. Adsorption 2017, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, M.M.; Pal, B.K. Sorption behavior of coal for implication in coal bed methane an overview. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, J.; Barakos, G.; Chang, P. Fractal characterization on methane adsorption in coal molecular structure. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 126611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Mou, J.; Cheng, Y. Impact of pore structure on gas adsorption and diffusion dynamics for long-flame coal. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 22, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Wei, C.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Lv, X. Experimental study on identification diffusion pores, permeation pores and cleats of coal samples. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2016, 138, 021201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Liu, D.; Tang, D.; Tang, S.; Huang, W.; Liu, Z.; Che, Y. Fractal characterization of seepage-pores of coals from China: An investigation on permeability of coals. Comput. Geosci. 2009, 35, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Miao, J.; Lv, R.; Lin, X. Quantitative 3D spatial characterization and flow simulation of coal macropores based on μCT technology. Fuel 2017, 200, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Chang, P.; Wang, X.; Lin, J. Fractal characteristics for coal chemical structure: Principle, methodology and implication. Chaos Solit. Fractals 2023, 173, 113699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Gray, F.; Crawshaw, J.; Boek, E. Micro-computed tomography pore-scale study of flow in porous media: Effect of voxel resolution. Adv. Water Resour. 2016, 95, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Guanhua, N.; Yan, W.; Hehe, J.; Yongzan, W.; Haoran, D.; Mao, J. Semi-homogeneous model of coal based on 3D reconstruction of CT images and its seepage-deformation characteristics. Energy 2022, 259, 125044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Zhu, H.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Li, Y. A fractal analytical model for Kozeny-Carman constant and permeability of roughened porous media composed of particles and converging-diverging capillaries. Powder Technol. 2023, 420, 118256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, N.; Liu, G.; Lin, J.; Chang, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H. Effects of CS2 Solvent Extraction on Nanopores in Coal. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 13799–13809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yang, Z.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Wei, W.; Yang, F.; Cai, J. Fractal analysis of pore structure differences between shale and sandstone based on the nitrogen adsorption method. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 1759–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhang, L.; Rao, B.; Qiu, S.; Shen, Y.; Wang, M. A fractal scaling law between tortuosity and porosity in porous media. Fractals 2020, 28, 2050025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Liu, H. Fractal characterization on fracture volume in coal based on Ct scanning: Principle, methodology, and implication. Fractals 2022, 30, 2250124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martínez, M.; Sánchez-Granero, M. Fractal dimension for fractal structures. Topol. Appl. 2014, 163, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan-pour, K.; Dutilleul, P.; Smith, D.L. Advances in the implementation of the box-counting method of fractal dimension estimation. Appl. Math. Comput. 1999, 105, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G. Fractal analysis of tight gas sandstones using high-pressure mercury intrusion techniques. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 24, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zou, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, W. Fractal analysis of high rank coal from southeast Qinshui basin by using gas adsorption and mercury porosimetry. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 156, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, J.; Du, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; Feng, W.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Y. Classification evaluation of gas shales based on high-pressure mercury injection: A case study on Wufeng and Longmaxi formations in southeast Sichuan, China. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 9382–9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhou, W.; Wu, J.; Huang, T. Fractal characterization of graphene oxide nanosheet. Mater. Lett. 2018, 220, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Lv, R.; Wang, X.; Chang, P.; Lin, J.; Barakos, G. Fractal Strategy for Improving Characterization of N2 Adsorption–Desorption in Mesopores. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H. Evolution of pore structures and fractal characteristics of coal-based activated carbon in steam activation based on nitrogen adsorption method. Powder Technol. 2023, 424, 118522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroniec, M.; Gilpin, R.; Choma, J. Correlation between microporosity and fractal dimension of active carbons. Carbon 1993, 31, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pan, J.; Cheng, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W. Relationship between micropore structure of different coal ranks and methane diffusion. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 2901–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatcraft, S.W.; Tyler, S.W. An explanation of scale-dependent dispersivity in heterogeneous aquifers using concepts of fractal geometry. Water Resour. Res. 1988, 24, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Cheng, P. A fractal permeability model for bi-dispersed porous media. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2002, 45, 2983–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, M.; Yu, B.; Cai, J. A fractal model for the starting pressure gradient for Bingham fluids in porous media. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2008, 51, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B. Analysis of flow in fractal porous media. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2008, 61, 050801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Li, J. Some fractal characters of porous media. Fractals 2001, 9, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzio, R.; Boragno, C.; Biscarini, F.; Buatier De Mongeot, F.; Valbusa, U. The contact mechanics of fractal surfaces. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, H.; Clauser, C.; Iffland, J. Variation of permeability with porosity in sandstone diagenesis interpreted with a fractal pore space model. Fractals Dyn. Syst. Geosci. 2000, 157, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Jiao, L.; Liu, Z.; Tan, X.; Wang, C.; Gao, J. Fractal analysis of pore structures in low permeability sandstones using mercury intrusion porosimetry. J. Porous Media 2018, 21, 1097–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, D.; Pan, Z.; Che, Y.; Liu, Z. Investigating the effects of seepage-pores and fractures on coal permeability by fractal analysis. Transp. Porous Media 2016, 111, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Si, G. Evaluation of coal petrophysics incorporating fractal characteristics by mercury intrusion porosimetry and low-field NMR. Fuel 2020, 263, 116802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xu, Y.; Gu, H.; Qiu, S.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Xu, P. Thermal-hydraulic performance of flat-plate microchannel with fractal tree-like structure and self-affine rough wall. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2023, 17, e2153174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, D.K.; Teklu, H.; Subbiah, S. Analysis of reverse osmosis process in hollow fiber module with and without secondary permeate outlet. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 36, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denn, M.M. Process Fluid Mechanics; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Cai, J.; Zou, M. On the physical properties of apparent two-phase fractal porous media. Vadose Zone J. 2009, 8, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jiang, Z.; Ji, W.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, L.; Yin, L. Heterogeneity of intergranular, intraparticle and organic pores in Longmaxi shale in Sichuan Basin, South China: Evidence from SEM digital images and fractal and multifractal geometries. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 72, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, E.W. The dynamics of capillary flow. Phys. Rev. 1921, 17, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 15901-1:2016; Evaluation of Pore Size Distribution and Porosity of Solid Materials by Mercury Porosimetry and Gas Adsorption—Part 1: Mercury Porosimetry. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Dou, W.; Liu, L.; Jia, L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, M.; Du, C. Pore structure, fractal characteristics and permeability prediction of tight sandstones: A case study from Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 123, 104737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, W.I.; Mikula, R.J. Mercury porosimetry of coals: Pore volume distribution and compressibility. Fuel 1988, 67, 1516–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B. Fractal character for tortuous streamtubes in porous media. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2005, 22, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yu, B. Fractal dimension for tortuous streamtubes in porous media. Fractals 2007, 15, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Li, J. A geometry model for tortuosity of flow path in porous media. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2004, 21, 1569–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Tian, T.; Wu, Z. Developmental characteristics and distribution law of fractures in a tight sandstone reservoir in a low-amplitude tectonic zone, eastern Ordos Basin, China. Geol. J. 2020, 55, 1546–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yang, K.; You, J.; Lei, X. Analysis of pore size distribution and fractal dimension in tight sandstone with mercury intrusion porosimetry. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Cheng, Y.; Pan, Z. Classification methods of pore structures in coal: A review and new insight. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 110, 204876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, S.; Li, J.; Chen, C.; Xue, H.; Zhang, J. Petrophysical characterization of oil-bearing shales by low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 89, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xiao, C.; Ni, H.; Gao, Q.; Han, L.; Xiao, D.; Jiang, S. Pore structure and pore size change for tight sandstone treated with supercritical CO2 fluid. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 2286–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Li, H.; Jin, W. Experimental study on the pore structure characteristics of tight sandstone reservoirs in Upper Triassic Ordos Basin China. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2016, 34, 418–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archie, G.E. Electrical resistivity an aid in core-analysis interpretation. AAPG Bull. 1947, 31, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Lin, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, Q. Pore characteristics of pervious concrete and their influence on permeability attributes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).