Fractal Analysis of Trabecular Bone Before and After Orthodontic and Surgical Extrusion: A Retrospective Case–Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Participants

2.4. Clinical Procedures

- Presence of adjacent teeth or anchorage elements for positioning the orthodontic appliance.

- Presence of sufficient clinical crown for the placement of orthodontic brackets.

- Orthodontic extrusion was, when possible, performed on single-rooted teeth, as higher forces are required for orthodontic movements of multi-rooted teeth [14].

- Patient’s possibility to undergo orthodontic treatment (e.g., attending follow-up visits).

- Patient’s need for shorter treatment (surgical extrusion).

- Patient’s inability to undergo surgical procedures (surgical extrusion) due to systemic conditions.

- Intrusion compared to the occlusal plane level (teeth that have suffered intrusive trauma or retained and/or included teeth).

- Need for a prosthetic restoration, but with insufficient ferrule and/or restorations that violate the biological width.

- Presence of a favorable crown/root ratio.

- Presence of a coronal fracture.

- Presence of subgingival carious lesions.

- All teeth were subject to circumferential supracrestal fiberotomy performed at the beginning of the extrusive treatment, using a 15C micro-blade parallel to the root along the perimeter of the gingival sulcus.

- All teeth were subjected to a vitality test prior to the beginning of the extrusive treatment, and endodontic treatment was performed on those that responded negatively.

- The employed extrusive technique was the SW (Straight-Wire) Technique.

- The patients followed a two-week follow-up recall, in order to check the amount of extrusion, reactivate the orthodontic appliance, and adjust the occlusion if necessary.

- The extrusive treatment lasted until the desired quantity of extrusion was achieved, which was a sufficient ferrule for placing a prosthetic restoration.

- Twenty-one orthodontically-extruded teeth were restored by placing an endocanalar fiberglass post and a lithium disilicate single crown; the remaining tooth helped with the development of the implant site.

- All teeth were subjected to a vitality test prior to the beginning of the extrusive treatment, and endodontic treatment was performed before or during the extrusive procedures for those that responded negatively.

- All teeth were atraumatically luxated using microsyndesmotomes and elevators and repositioned coronally to their original position, in order to achieve sufficient ferrule for placing a prosthetic restoration.

- The extruded tooth was splinted to the adjacent tooth (or teeth), where composite resin and a passive stainless-steel wire were placed, and was kept in situ for 10 days; if necessary, the tooth was adjusted in its occlusion as well.

- All surgically extruded teeth were restored by placing an endocanalar fiberglass post and a lithium disilicate prosthetic restoration (18 were single crowns, and the remaining 4 were part of a fixed dental prosthesis supported by natural teeth).

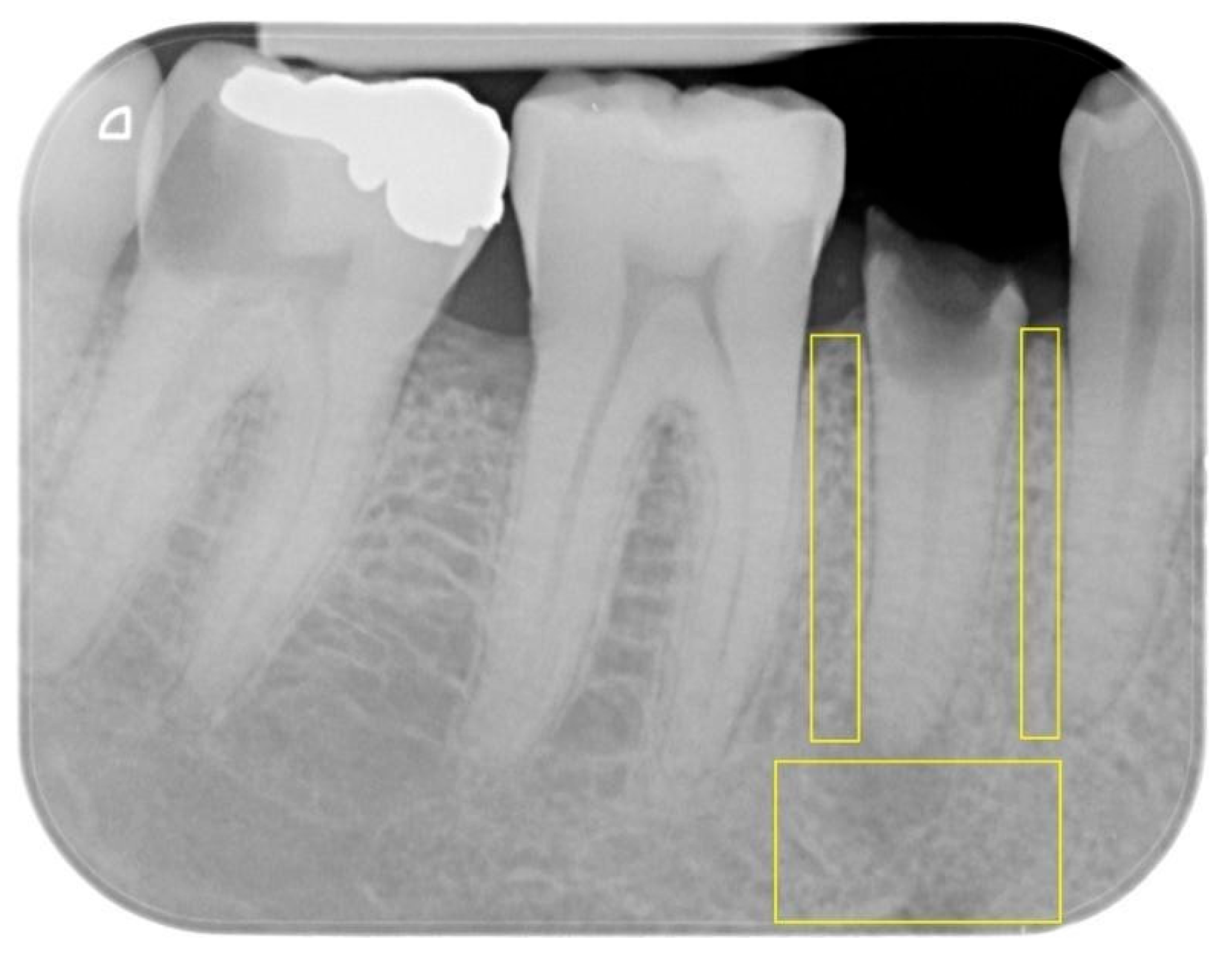

2.5. Protocol and Measurements

- Apical ROI: extending horizontally between the mesial and distal root surfaces of the tooth and vertically between the root apex and the lower edge of the image.

- Mesial proximal ROI: extending vertically from the mesial alveolar ridge to the tooth apex and horizontally between the root surfaces of the two adjacent teeth.

- Distal proximal ROI: extending vertically from the distal alveolar ridge to the tooth apex and horizontally between the root surfaces of the two adjacent teeth.

2.6. Study Timeline

- T0: pre-treatment.

- T1: post-treatment, which was set at the removal of the splint for SE and at the reaching of the desired amount of extrusion for OE.

- T2: follow-up at 3 months.

- T3: follow-up at 6 months.

2.7. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Baseline (T0)

3.2. Post-Extrusion (T1)

3.3. Three-Month Follow-Up (T2)

3.4. Six-Month Follow-Up (T3)

4. Discussion

4.1. OE Group

4.2. SE Group

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

4.5. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cordaro, M.; Staderini, E.; Torsello, F.; Grande, N.M.; Turchi, M.; Cordaro, M. Orthodontic Extrusion vs. Surgical Extrusion to Rehabilitate Severely Damaged Teeth: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, B.A.S.; Duarte, C.A.B.; Silva, J.F.; Batista, W.; Douglas-de-Oliveira, D.W.; de Oliveira, E.S.; Soares, L.G.; Galvao, E.L.; Rocha-Gomes, G.; Gloria, J.C.R.; et al. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of the Periodontium with biologic width invasion. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, E.S.; Cho, S.C.; Garber, D.A. Crown lengthening revisited. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 1999, 20, 527–532, 534, 536–538 passim; quiz 542. [Google Scholar]

- Nugala, B.; Kumar, B.S.; Sahitya, S.; Krishna, P.M. Biologic width and its importance in periodontal and restorative dentistry. J. Conserv. Dent. 2012, 15, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadi, A.; Rangarajan, V.; Savadi, R.C.; Satheesh, P. Biologic perspectives in restorative treatment. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2011, 11, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, A.; Krajewski, J.; Gargiulo, M. Defining biologic width in crown lengthening. CDS Rev. 1995, 88, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ingber, J.S.; Rose, L.F.; Coslet, J.G. The “biologic width”—A concept in periodontics and restorative dentistry. Alpha Omegan 1977, 70, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.C.; Sahrmann, P.; Weiger, R.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Walter, C. Biologic width dimensions—A systematic review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padbury, A., Jr.; Eber, R.; Wang, H.L. Interactions between the gingiva and the margin of restorations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2003, 30, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, S.; Caton, J.G.; Albandar, J.M.; Bissada, N.F.; Bouchard, P.; Cortellini, P.; Demirel, K.; de Sanctis, M.; Ercoli, C.; Fan, J.; et al. Periodontal manifestations of systemic diseases and developmental and acquired conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 3 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S237–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicari, F.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Scotti, R.; Naert, I. Effect of ferrule and post placement on fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth after fatigue loading. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juloski, J.; Radovic, I.; Goracci, C.; Vulicevic, Z.R.; Ferrari, M. Ferrule effect: A literature review. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankiewicz, N.R.; Wilson, P.R. The ferrule effect: A literature review. Int. Endod. J. 2002, 35, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Martin, O.; Solano-Hernandez, B.; Torres Munoz, A.; Gonzalez-Martin, S.; Avila-Ortiz, G. Orthodontic Extrusion: Guidelines for Contemporary Clinical Practice. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2020, 40, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, N.; Baylard, J.F.; Voyer, R. Orthodontic extrusion: Periodontal considerations and applications. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 70, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Plotino, G.; Abella Sans, F.; Duggal, M.S.; Grande, N.M.; Krastl, G.; Nagendrababu, V.; Gambarini, G. Clinical procedures and outcome of surgical extrusion, intentional replantation and tooth autotransplantation—A narrative review. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 1636–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardaropoli, G.; Araujo, M.; Lindhe, J. Dynamics of bone tissue formation in tooth extraction sites. An experimental study in dogs. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2003, 30, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.C.; de Molon, R.S.; Martins, R.P.; Ribeiro, F.S.; Pontes, A.E.F.; Zandim-Barcelos, D.L.; Leite, F.R.M.; Benatti Neto, C.; Marcantonio, R.A.C.; Cirelli, J.A. Effects of orthodontic tooth extrusion produced by different techniques, on the periodontal tissues: A histological study in dogs. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020, 116, 104768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolinario, A.C.; Sindeaux, R.; de Souza Figueiredo, P.T.; Guimaraes, A.T.; Acevedo, A.C.; Castro, L.C.; de Paula, A.P.; de Paula, L.M.; de Melo, N.S.; Leite, A.F. Dental panoramic indices and fractal dimension measurements in osteogenesis imperfecta children under pamidronate treatment. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2016, 45, 20150400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goller Bulut, D.; Bayrak, S.; Uyeturk, U.; Ankarali, H. Mandibular indexes and fractal properties on the panoramic radiographs of the patients using aromatase inhibitors. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20180442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, S.; Goller Bulut, D.; Orhan, K.; Sinanoglu, E.A.; Kursun Cakmak, E.S.; Misirli, M.; Ankarali, H. Evaluation of osseous changes in dental panoramic radiography of thalassemia patients using mandibular indexes and fractal size analysis. Oral Radiol. 2020, 36, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demiralp, K.O.; Kursun-Cakmak, E.S.; Bayrak, S.; Akbulut, N.; Atakan, C.; Orhan, K. Trabecular structure designation using fractal analysis technique on panoramic radiographs of patients with bisphosphonate intake: A preliminary study. Oral Radiol. 2019, 35, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kursun-Cakmak, E.S.; Bayrak, S. Comparison of fractal dimension analysis and panoramic-based radiomorphometric indices in the assessment of mandibular bone changes in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Oral Surg. Oral. Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2018, 126, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesur, E.; Bayrak, S.; Kursun-Cakmak, E.S.; Arslan, C.; Koklu, A.; Orhan, K. Evaluating the effects of functional orthodontic treatment on mandibular osseous structure using fractal dimension analysis of dental panoramic radiographs. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.C.; Rudolph, D.J. Alterations of the trabecular pattern of the jaws in patients with osteoporosis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1999, 88, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, C.N.; Barra, S.G.; Tavares, N.P.; Amaral, T.M.; Brasileiro, C.B.; Mesquita, R.A.; Abreu, L.G. Use of fractal analysis in dental images: A systematic review. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2020, 49, 20180457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, I.; Uzcategui, G. Fractals in dentistry. J. Dent. 2011, 39, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soylu, E.; Cosgunarslan, A.; Celebi, S.; Soydan, D.; Demirbas, A.E.; Demir, O. Fractal analysis as a useful predictor for determining osseointegration of dental implant? A retrospective study. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2021, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulec, M.; Tassoker, M.; Ozcan, S.; Orhan, K. Evaluation of the mandibular trabecular bone in patients with bruxism using fractal analysis. Oral Radiol. 2021, 37, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, P.; Sami, S.; Yaghini, J.; Golkar, E.; Riccitiello, F.; Spagnuolo, G. Application of Fractal Analysis in Detecting Trabecular Bone Changes in Periapical Radiograph of Patients with Periodontitis. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 3221448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, R.J.; Slabbert, J.C.; Kathree, H.; Owen, C.P.; Crombie, K.; Delport, P. The use of fractal analysis to reveal remodelling in human alveolar bone following the placement of dental implants. Arch. Oral Biol. 1995, 40, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciavarella, D.; Lorusso, M.; Fanelli, C.; Ferrara, D.; Esposito, R.; Laurenziello, M.; Esperouz, F.; Lo Russo, L.; Tepedino, M. The Efficacy of the RME II System Compared with a Herbst Appliance in the Treatment of Class II Skeletal Malocclusion in Growing Patients: A Retrospective Study. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, S.; Korkmaz, Y.N.; Buyuk, S.K.; Tekin, B. Effects of reverse headgear therapy on mandibular trabecular structure: A fractal analysis study. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2022, 25, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darawsheh, A.F.; Kolarovszki, B.; Hong, D.H.; Farkas, N.; Taheri, S.; Frank, D. Applicability of Fractal Analysis for Quantitative Evaluation of Midpalatal Suture Maturation. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muftuoglu, O.; Karasu, H.A. Assessment of mandibular bony healing, mandibular condyle and angulus after orthognathic surgery using fractal dimension method. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2024, 29, e620–e625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperouz, F.; Ciavarella, D.; Lorusso, M.; Santarelli, A.; Lo Muzio, L.; Campisi, G.; Lo Russo, L. Critical review of OCT in clinical practice for the assessment of oral lesions. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1569197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavarella, D.; Lorusso, M.; Fanelli, C.; Cazzolla, A.P.; Maci, M.; Ferrara, D.; Lo Muzio, L.; Tepedino, M. The Correlation between Mandibular Arch Shape and Vertical Skeletal Pattern. Medicina 2023, 59, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gili, T.; Di Carlo, G.; Capuani, S.; Auconi, P.; Caldarelli, G.; Polimeni, A. Complexity and data mining in dental research: A network medicine perspective on interceptive orthodontics. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2021, 24, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association (AMM). Helsinki Declaration. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Assist. Inferm. Ric. 2001, 20, 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, H.; Almutairi, M.S.; Alrajhi, S.; Almotairy, N. Effect of Orthodontic Movement on the Periapical Healing of Teeth Undergone Endodontic Root Canal Treatment: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolaro, A.; Miranda, D.A.O.; Consolaro, R.B. Orthodontics and Endodontics: Clinical decision-making. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2020, 25, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Installation & Operating Instructions, DBSWIN 5.17 Dental Imaging Software; Dürr Dental SE: Bietigheim-Bissingen, Germany; Air Techniques, Inc.: Melville, NY, USA, 2022.

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Lee, H.J. Surgical extrusion of a maxillary premolar after orthodontic extrusion: A retrospective study. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 45, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhnke, M.; Beuer, F.; Bose, M.W.H.; Naumann, M. Forced orthodontic extrusion to restore extensively damaged anterior and premolar teeth as abutments for single-crown restorations: Up to 5-year results from a pilot clinical study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 129, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, F.; Schulz, P. Multiple correlations and Bonferroni’s correction. Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 44, 775–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argueta, J. Surgical extrusion: A reliable technique for saving compromised teeth. A 5-years follow-up case report. G. Ital. di Endod. 2018, 32, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conserva, E.; Fadda, M.; Ferrari, V.; Consolo, U. Predictability of a New Orthodontic Extrusion Technique for Implant Site Development: A Retrospective Consecutive Case-Series Study. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 4576748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, E.; Aoun, G.; Bassit, R.; Nasseh, I. Correlating Radiographic Fractal Analysis at Implant Recipient Sites with Primary Implant Stability: An In Vivo Preliminary Study. Cureus 2020, 12, e6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, L.; Maurino, V.; Vinci, R.; Croveri, F.; Boggio, A.; Tagliabue, A.; Silvestre-Rangil, J.; Tettamanti, L. ADULT syndrome: Dental features of a very rare condition. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Azzi, L.; Croveri, F.; Vinci, R.; Maurino, V.; Boggio, A.; Mantegazza, D.; Farronato, D.; Tagliabue, A.; Silvestre-Rangil, J.; Tettamanti, L. Oral manifestations of selective IgA-deficiency: Review and case-report. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frost, H.M. A 2003 update of bone physiology and Wolff’s Law for clinicians. Angle Orthod. 2004, 74, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teichtahl, A.J.; Wluka, A.E.; Wijethilake, P.; Wang, Y.; Ghasem-Zadeh, A.; Cicuttini, F.M. Wolff’s law in action: A mechanism for early knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaitsas, R.; Paolone, M.G.; Paolone, G. Guided orthodontic regeneration: A tool to enhance conventional regenerative techniques in implant surgery. Int. Orthod. 2015, 13, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucchi, A.; Bettini, S.; Fiorino, A.; Maglio, M.; Marchiori, G.; Corinaldesi, G.; Sartori, M. Histological and histomorphometric analysis of bone tissue using customized titanium meshes with or without resorbable membranes: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2024, 35, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivolella, S.; Meggiorin, S.; Ferrarese, N.; Lupi, A.; Cavallin, F.; Fiorino, A.; Giraudo, C. CT-based dentulous mandibular alveolar ridge measurements as predictors of crown-to-implant ratio for short and extra short dental implants. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, W.E. The ALARA-principle. Backgrounds and enforcement in dental practices. Ned. Tijdschr. Tandheelkd. 2015, 122, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.E.B.; Dos Santos, H.S.; Ruhland, L.; Rabelo, G.D.; Badaro, M.M. Fractal analysis of dental periapical radiographs: A revised image processing method. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2023, 135, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.K.; Oviir, T.; Lin, C.H.; Leu, L.J.; Cho, B.H.; Hollender, L. Digital imaging analysis with mathematical morphology and fractal dimension for evaluation of periapical lesions following endodontic treatment. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2005, 100, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D.; Levin, L. In the dental implant era, why do we still bother saving teeth? Dent. Traumatol. 2019, 35, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinans, H.; Huiskes, R.; Grootenboer, H.J. The behavior of adaptive bone-remodeling simulation models. J. Biomech. 1992, 25, 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.-J.; Jeong, S.-W.; Jo, B.-H.; Kim, Y.-D.; Kim, S.S. Observation of trabecular changes of the mandible after orthognathic surgery using fractal analysis. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 38, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Male (%) | Female (%) | Mean Age (SD) | Single-Rooted Teeth (%) | Multi-Rooted Teeth (%) | Maxillary Teeth (%) | Mandibular Teeth (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE group | 22 | 12 (54.5%) | 10 (45.4%) | 36.6 (7.7) | 21 (95.5%) | 1 (4.5%) | 15 (68.2%) | 7 (31.8%) |

| SE group | 22 | 11 (50%) | 11 (50%) | 46.1 (9.2) | 16 (72.7%) | 6 (27.3%) | 15 (68.2%) | 7 (31.8%) |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Adult subjects > 18 years with permanent dentition | Growing patients or patients with deciduous teeth |

| Presence of pre- and post-extrusive treatment and follow-up periapical radiographs | Absence of radiographic records of the extrusive treatment |

| Extrusive (orthodontic or surgical) treatment (with a minimum quantity of extrusion of 2 mm), performed in the presence of structurally compromised teeth | Patients undergoing the surgical crown lengthening technique (SCC) to achieve sufficient ferrule and biological width |

| Signed informed consent form to participate in the study | Patients not willing to participate in the study |

| Variable | Orthodontic Extrusion N = 22 | Surgical Extrusion N = 22 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 10 (45%) | 11 (50%) | 1.0 a |

| Age (years) | 42.1 ± 7.7 | 46.1 ± 9.2 | 0.121 b |

| Smokers | 8 (36%) | 9 (41%) | 1.0 a |

| Upper teeth | 15 (68%) | 16 (73%) | 1.0 a |

| Molars | 1 (5%) | 5 (23%) | 0.185 b |

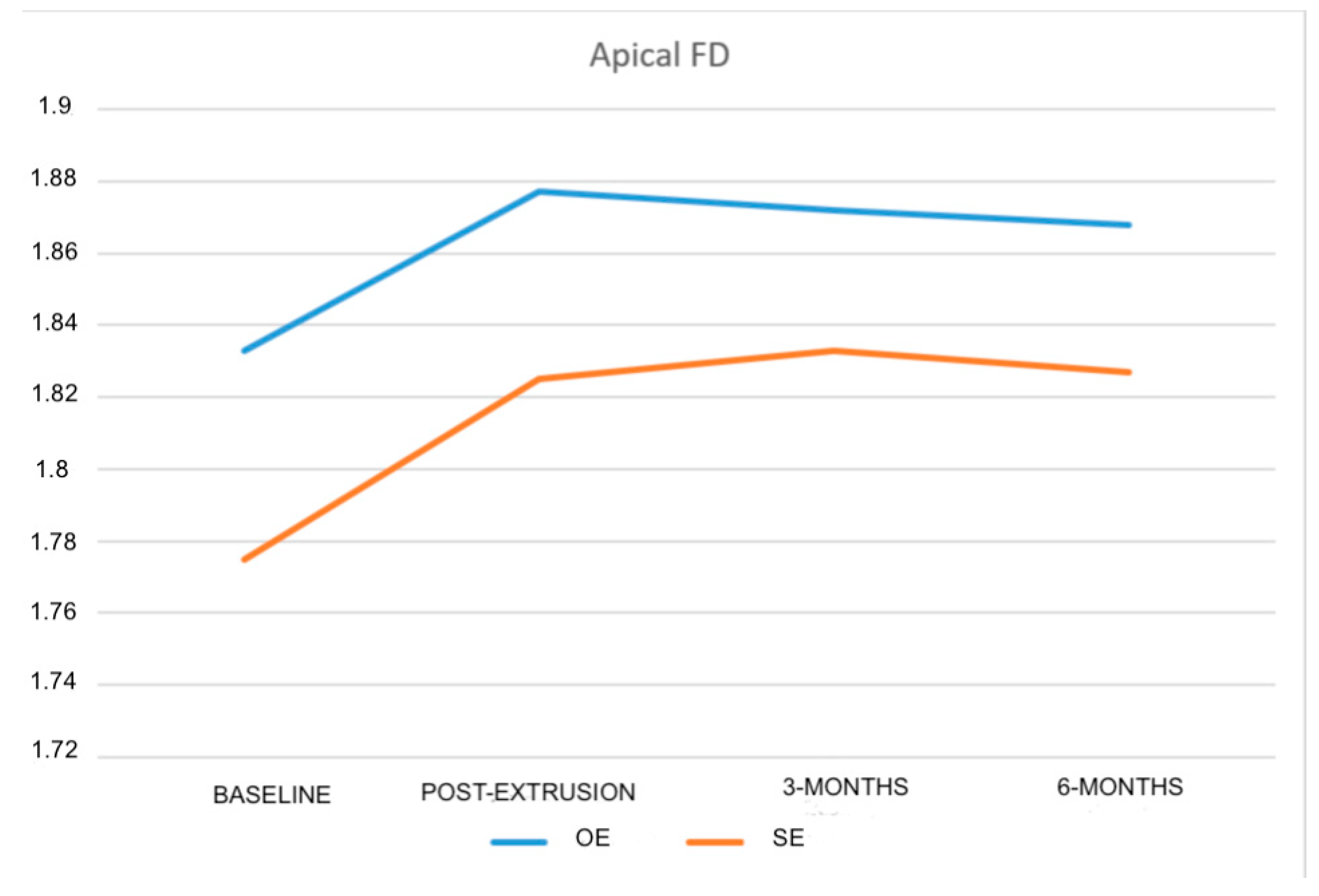

| Apical FD | 1.833 ± 0.046 | 1.775 ± 0.064 | 0.001 b* |

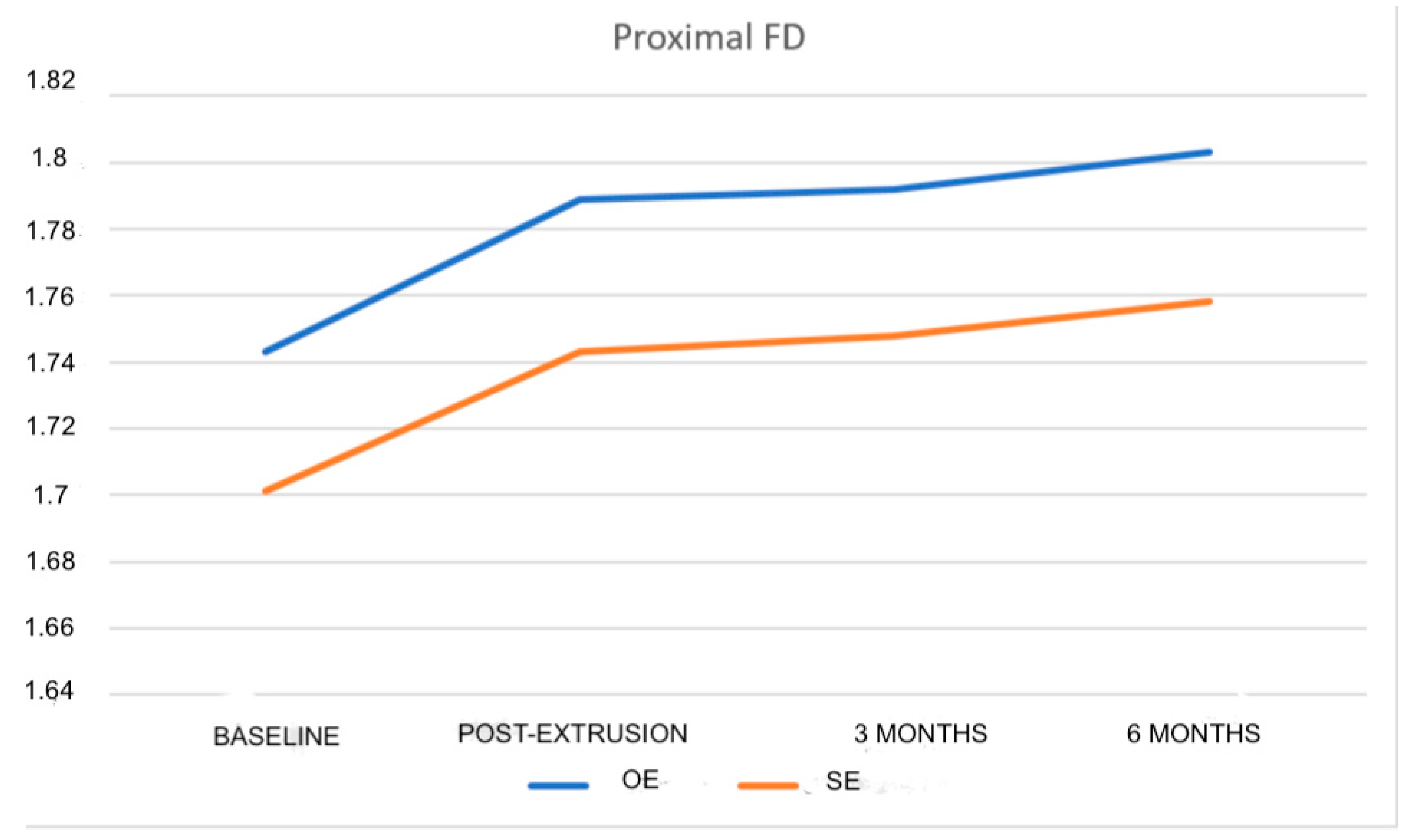

| Proximal FD | 1.743 ± 0.056 | 1.701 ± 0.057 | 0.018 b* |

| Orthodontic Extrusion N = 22 | Surgical Extrusion N = 22 | |

|---|---|---|

| Post-extrusion apical FD | 1.877 ± 0.047 | 1.825 ± 0.054 |

| Apical baseline FD vs. post-extrusion FD | 0.044 ± 0.054 | 0.049 ± 0.050 |

| 95%CI (intra-group) | 0.020; 0.068 | 0.027; 0.072 |

| p-value (intra-group) | 0.001 * | <0.001 * |

| Effect size (intra-group) | 0.48 | 0.43 |

| Orthodontic Extrusion N = 22 | Surgical Extrusion N = 22 | |

|---|---|---|

| Post-extrusion proximal FD | 1.789 ± 0.044 | 1.743 ± 0.051 |

| Proximal baseline FD vs. post-extrusion FD | 0.046 ± 0.031 | 0.042 ± 0.045 |

| 95%CI (intra-group) | 0.032; 0.060 | 0.022; 0.062 |

| p-value (intra-group) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * |

| Effect size (intra-group) | 0.41 | 0.84 |

| Orthodontic Extrusion N = 22 | Surgical Extrusion N = 22 | Adjusted Difference | 95%CI (Inter-Group) | p-Value ANCOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-month apical FD | 1.872 ± 0.055 | 1.833 ± 0.044 | - | - | - |

| Apical baseline FD vs. 3 months | 0.039 ± 0.062 | 0.058 ± 0.049 | 0.016 | −0.016; 0.047 | 0.303 |

| 95%CI (intra-group) | 0.011; 0.066 | 0.036; 0.080 | - | - | - |

| p-value (intra-group) | 0.008 * | <0.001 * | - | - | - |

| Effect size (intra-group) | 0.39 | 0.54 | |||

| Orthodontic Extrusion N = 22 | Surgical Extrusion N = 22 | Adjusted Difference | 95%CI (Inter-Group) | p-Value ANCOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-month proximal FD | 1.792 ± 0.051 | 1.748 ± 0.048 | - | - | - |

| Proximal baseline FD vs. 3 months | 0.050 ± 0.034 | 0.047 ± 0.042 | 0.017 | −0.005; 0.038 | 0.122 |

| 95%CI (intra-group) | 0.035; 0.065 | 0.029; 0.066 | - | - | - |

| p-value (intra-group) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | - | - | - |

| Effect size (intra-group) | 0.43 | 0.2 | |||

| Orthodontic Extrusion N = 22 | Surgical Extrusion N = 22 | Adjusted Difference | 95%CI (Inter-Group) | p-Value ANCOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-month apical FD | 1.868 ± 0.054 | 1.827 ± 0.044 | - | - | - |

| Apical baseline FD vs. 6 months | 0.034 ± 0.072 | 0.051 ± 0.053 | 0.027 | −0.007; 0.060 | 0.113 |

| 95%CI (intra-group) | 0.003; 0.066 | 0.028; 0.075 | - | - | - |

| p-value (intra-group) | 0.036 * | <0.001 * | - | - | - |

| Effect size (intra-group) | 0.35 | 0.48 | |||

| Orthodontic Extrusion N = 22 | Surgical Extrusion N = 22 | Adjusted Difference | 95%CI (Inter-Group) | p-Value ANCOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-month proximal FD | 1.803 ± 0.053 | 1.758 ± 0.056 | - | - | - |

| Proximal baseline FD vs. 6 months | 0.060 ± 0.031 | 0.057 ± 0.044 | 0.014 | −0.009; 0.037 | 0.228 |

| 95%CI (intra-group) | 0.046; 0.073 | 0.037; 0.076 | - | - | - |

| p-value (intra-group) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | - | - | - |

| Effect size (inter-group) | 0.47 | 0.1 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Staderini, E.; Guglielmi, F.; Alessandri Bonetti, A.; Cavalcanti, I.; Grande, N.M.; Castagnola, R.; Gallenzi, P. Fractal Analysis of Trabecular Bone Before and After Orthodontic and Surgical Extrusion: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120818

Staderini E, Guglielmi F, Alessandri Bonetti A, Cavalcanti I, Grande NM, Castagnola R, Gallenzi P. Fractal Analysis of Trabecular Bone Before and After Orthodontic and Surgical Extrusion: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):818. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120818

Chicago/Turabian StyleStaderini, Edoardo, Federica Guglielmi, Anna Alessandri Bonetti, Irene Cavalcanti, Nicola Maria Grande, Raffaella Castagnola, and Patrizia Gallenzi. 2025. "Fractal Analysis of Trabecular Bone Before and After Orthodontic and Surgical Extrusion: A Retrospective Case–Control Study" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120818

APA StyleStaderini, E., Guglielmi, F., Alessandri Bonetti, A., Cavalcanti, I., Grande, N. M., Castagnola, R., & Gallenzi, P. (2025). Fractal Analysis of Trabecular Bone Before and After Orthodontic and Surgical Extrusion: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120818