Abstract

In this manuscript, we investigate a fractional-order conformable three-dimensional chaotic financial model with interest rate, investment demand, and price index compartments. On the application of fixed-point theorems and nonlinear analysis, we establish theoretical results regarding the existence and uniqueness of a solution and also study Ulam–Hyers criteria for the stability of the solution of the considered system. Further, we use the fractional-order Runge–Kutta (RK-4) method to approximate the solution of our problem. Also, deep neural network (DNN) techniques are applied to investigate the model from artificial intelligence (AI) perspectives. Numerical simulation shows that it reproduces accurately the qualitative dynamics and confirms the theoretical stability results of the mentioned system. Subsequently, for the DNN analysis, we follow the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm using Matlab 2023. Different quantities like the root-mean-square error (RMSE), mean squared error (MSE), and regression coefficient and a comparison with numerical data are presented graphically. Also, absolute errors between numerical values and those predicted by DNNs corresponding to different fractional orders are presented.

1. Introduction

The chaotic model for financial problems (finance chaotic theory) is an approach that was developed in the 20th century to discuss the volatile and unpredictable behaviour of financial markets. It proposes that markets of financial activities are inherently chaotic systems, represented by dynamics of nonlinear nature and a delicate dependence on the initial state [1]. After the worldwide financial catastrophe of 2008, the idea achieved boundless recognition when many existing economic models failed to explain the consequences of the crisis. The crisis highlighted how the interrelationship between various institutions and departments could enhance risks and create logical weakness. The complete history of the chaotic model for financial problems shows an interest in guessing and reconciling the complex and irrational nature of financial activities in markets. This subject is a continued and important area of research for finance professionals, economists, and mathematicians. Chaos in a system refers to a behaviour that follows mathematical rules but still shows an unpredictable or random nature. Many systems exhibiting chaotic behaviour have been suggested in recent studies for financial problems; for instance, refer to [2,3,4,5].

Modelling of deterministic chaotic attractors has gained a lot of interest from researchers in recent time. Problems with self-similarities cannot be accurately studied by the application of integer-order derivative. Therefore, in recent studies, Atangana and his co-author(s) have studied chaos in dynamical problems with the help of fractal derivative [6], and numerical schemes have also been developed to demonstrate a chaotic problem [7]. On the application of ABC derivatives, the authors in [8] discuss chaos in nonlinear systems. The fractional-order chaotic behaviour of a dynamical system was studied through circuit modelling [9]. In [10], the authors utilized bifurcation analysis to analyse chaotic fractional-order model under the Caputo derivative of fractional order. The authors in [11] developed the financial chaos model using a fractal–fractional operator in the Riemann–Liouville sense. They studied the model theoretically as well as numerically; on fixed-point theory, the qualitative behaviour and Adams–Bashforth method were utilized for numerical discussion. The model in integer-order derivative presented in [11] is defined as follows:

where and are the state variables of the model and represent the interest rate, investment demand, and price index, respectively. The variable is affected by the pricing of the product and the inconsistencies in the investment of the market. On the other hand, the rate of change in investment demand is affected by investment cost and interest rate. The inflation rate, demand, and supply in the market affect the changes in price index. The parameter represents the saving rate, shows the rate of investment per unit cost, and represents the elasticity of the demand.

Alternatively, fractional calculus (FC) is currently one of the best concepts of research which extends the notion of integer-order derivative to any real or complex order. By changing the integer-order derivatives with a conformable fractional operator, the system can explain memory and hereditary properties of financial markets. The fractional formulation under a conformable derivative provides a good mathematical structure for modelling the dynamics of chaotic financial markets. It has been shown that FC can model problem with irrational and complex behaviour more accurately than the classical concept. Examples include the analysis of novel nonlinear fractional-order financial system [12], application of fractional derivative in signal processing within the financial stock market [13], the effect of market confidence using fractional calculus [14], and FC and continuous-time finance [15]. Model (1) under the considered conformable fractional concepts is expressed as follows:

with the same initial conditions:

In dynamical systems, the existence of solutions and their stability are important concepts. The answers to the following queries matter: whether a mathematical model for a real-world problem is accurate or not, whether the solution(s) of the system exist(s) or not, and whether the solution of the system is stable or not. For the answer to such questions, researchers have used the definitions and results of qualitative concept. The existence of solution(s) has been discussed using fixed-point theory, while the stability of the model is considered in the sense of Ulam–Hyer’s concept. The mentioned concept of stability was introduced for the first time by S. M. Ulam in a talk in 1940 at the University of Wisconsin, where he explained the stability of functional equations [16]. Further, the concept was generalized by Hyers, who applied the definition for the first time in Banach spaces in 1941 [17]. The suggested stability in the recent past have been studied by numerous researchers for some important problems of applied sciences [18,19,20]. The Ulam–Hyer definition of stability ensures that for small perturbations in the initial state, the solution of the model remains nearly equal to the exact curve, thus ensuring the robustness of the system.

The aim of this research work was to study the above financial chaotic model using qualitative theory and a numerical solution under a conformable fractional derivative. The selection of the conformable derivative of real order was motivated by its closed connection with integer-order differential calculus. Unlike, operators with non-singular and nonlocal kernels (like Riemann–Liouville, Caputo, Atangana–Baleanu, Caputo–Fabrizio, etc.), the proposed operator preserves various essential properties of the classical derivative, such as linearity, the product rule, the chain rule, the quotient rule, and the fact that the derivative of a constant function is zero. These characteristics make the analysis regarding qualitative theory and numerical approximation easy and allows us to directly apply classical methods to the fractional concept under the mentioned derivative. In addition, the derivative of conformable type provides a physical interpretation and avoids kernels of singular type. Because of its simple definition, it provides stable and simple numerical schemes with less computational cost. In the DNN approximation, the unavailability of memory kernels hides the numerical error accumulation and boosts convergence during execution. On the other hand, the conformable fractional derivative is local, but the fractional order brings an effective scaling of memory effects in the system. For smaller values of , the evolution is slowed down, providing that past states of the system influence the dynamics of the system more in the present time. This behaviour allows the mathematical model to catch the hereditary nature and market memory in a clear way. Further, when , the model reduces to an integer-order financial model, and when , fractional order effects arise. This fractional parameter is thus important for investigating the impact of hereditary and memory effects on financial activities.

Additionally, the fractional order in the derivative acts as a memory index that shows and controls how the present state depends on the past evolution of the system. Specifically, if the financial model under the mentioned derivative is formulated, then the solution curves take a time-scaled nonlinear form of the integer-order model, which means the past behaviour influences the current state of the dynamical system through the real order. Smaller values of the fractional order increase the genetic influence of market conditions, such as delayed reactions of traders, long-term dependence in prices, hence uncovering the hereditary behaviour of financial activities. Therefore, the conformable fractional derivative attaches memory through fractional-time deformation, which allows the system to show faster or slower responses according to the values encoded in . These techniques extend the ordinary model for representing market memory without using complicated kernels of integral type. In financial models, the parameter represents a quantitative value of market memory, past events, adjustment speed. For example, when , the nature of the market is almost classical with the absorption of fast information, and for smaller values of , the model shows the slower information diffusion, delayed responses, and long-term dependence detected during crises and uncertainty. A higher value of the parameter means a short memory of the market; hence, investors react directly about the current situation to produce stability and order in the dynamics of financial activity.A smaller value of the fractional parameter means long-memory effects and past events affecting the present activity of the market more strongly. The parameter acts as a bifurcation that can change the qualitative dynamics of a system. The transition of the model from smooth trajectories to an oscillatory and irregular behaviour occurs when the value of the fractional order decreases. The market behaves stably and efficient for higher fractional orders. Hence, by selecting various values of , the system can be economically meaningful.

Recently, AI-based DNNs have attracted a lot attention because they have the ability to interpret data without knowing their dynamical behaviours. In the last two years, researchers have published very fruitful results using DNNs. For instance, recently, authors [21] have used DNNs to investigate a biological model of mental disease. Also, researchers [22] have applied DNNs to investigate an epidemic disease model. A model representing the coupled dynamics of materials recycling was studied by using a fractional-order derivative and DNNs recently [23]. These approaches have been extensively used in investigating various problems related to fluid mechanics and other fields; refer to [24,25]. The DNNs consist on multiple layers interconnected by nodes. There are multiple hidden layers together with input and output layers. Input layers take data and process them through hidden layers to yield an output through output layers. The mentioned process in mathematical form can be described by a function which takes input and outputs , where are the dimensions of input and output elements.

or in a more sophisticated way, we can also describe it as follows:

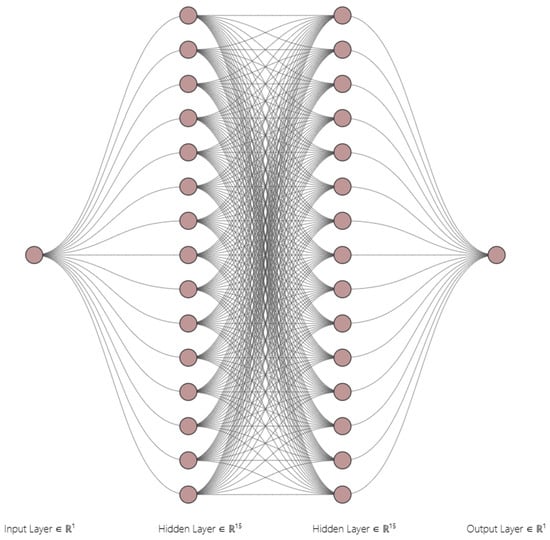

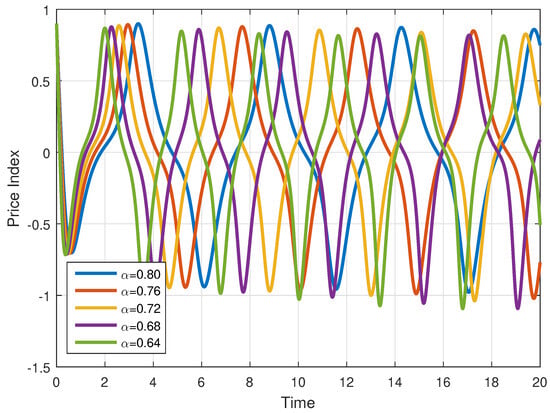

where stands for an activation function. In our analysis, the tangent hyperbolic function was utilized as the activation function in the hidden layers of DNNs. The considered activation function was used due to various reasons: the function is differentiable and smooth, showing a stable nature which is necessary for gradient-based optimization methods. Further, the nonlinear nature of the function provides sufficient nonlinearity to approximate complex nonlinear dynamical systems accurately by keeping the output in a controlled range for numerical stability. The convergence rate of the mentioned activation function is better than that of other activation functions. The considered DNN structure can be presented diagrammatically as in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Architecture of DNNs.

In Figure 1, the DNN has one input, two hidden layers with a total of 30 neurons, and one output.With the help of DNNs, we analyzed our considered model and computed various metrics including the RMSE, MSE, regression coefficient, and function data best fitting each compartment. We present these quantities graphically. Also, a comparison between the predicted and numerical data for all three classes is presented. The absolute errors for all three classes were computed and are presented graphically.

2. Basic Definitions and Results

Here, some basic results are presented.

Definition 1

([26]). The fractional conformable derivative of a function with order is given by

Definition 2

([26]). The fractional conformable integral of a function with order is given by

Lemma 1

([26]). For the continuous function , the result presented below in the context of a conformable fractional derivative holds.

Lemma 2

([26]). Additionally, the result given below also holds under the conformable fractional derivative.

3. Existence Theory

In this part of the manuscript, the qualitative aspect of our proposed model is discussed. By applying fixed-point theorems, sufficient results for the existence of at least one solution and unique solution are developed. The stability theory is discussed in the light of Ulam–Hyer’s concept. For simplification, we assume that

Using Equation (5), the model of our study can be written as,

where the functions , and are formulated as follows:

Using the definition of fractional integral in the conformable sense, the equivalent integral of Equation (6) is calculated as follows,

Additionally, let denote a Banach space with a norm on defined by Function is defined by

Further, the following assumptions are key to our results.

- (A1)

- The constant exists, with the property that

- (A2)

- The constant exists, with the property that

Theorem 1.

Proof.

Consider a closed, convex, and bounded subset of Δ; then, for any , we have

Hence, , which ensures that Ψ is bounded, and for , Also, the function is continuous, and as a result, the function Ψ is continuous. For equi-continuity, let , such that

Now, from assumption , and , we have

Therefore,

which implies that Ψ is equi-continuous; hence, Ψ is uniformly continuous. Now, by applying Arzela–Ascoli theorem and Schauder’s fixed-point theorem, function Ψ has at least one fixed point; consequently, model (6) has at least on solution. □

Theorem 2.

Proof.

Let ; then, we have

Thus, Ψ is a contraction, and on the basis of Banach’s fixed-point theorem, Ψ has a unique fixed point. Therefore, model (6) has a unique solution. □

Ulam–Hyer’s Stability

Finally, the stability in the Ulam–Hyer sense of the solution of the proposed model is discussed here. The perturbed problem corresponding to Equation (6) is formulated as

Here, with property . The equivalent integral form of the above perturbed problem (13) is calculated as follows, using the definition of a conformable fractional integral:

4. Approximate Solution of the Model

In this section, we apply the fractional-order RK-4 (Runge-Kutta) method addressed in [25,27] to obtain the approximate solution to model (3). For , where on the studied interval , let the interval be divided into subintervals ; then, the method is expressed for the model

as follows:

where

Using the above method, the solution of model (3) is calculated as

where

and

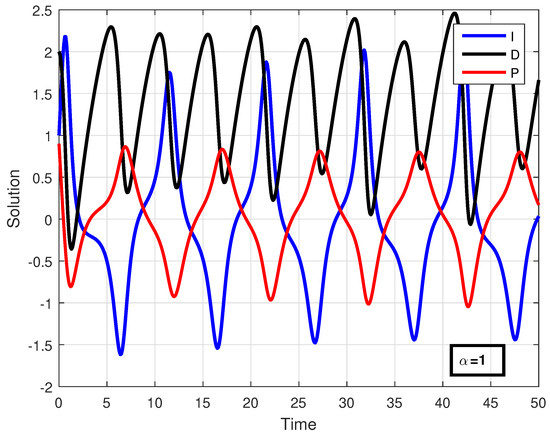

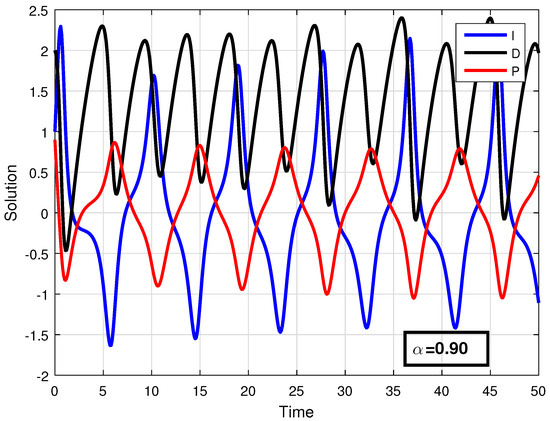

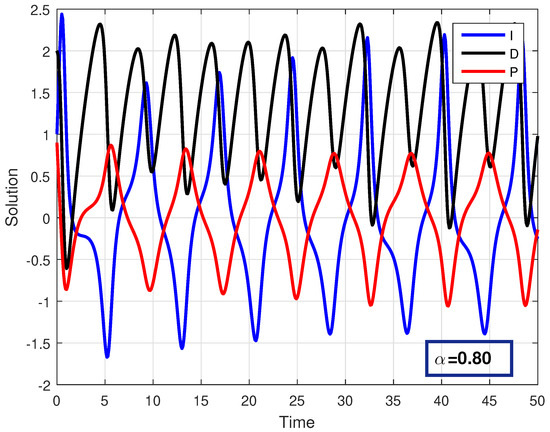

Using the developed numerical algorithm, the solution of problem (3) was simulated in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 with step size and . For the approximate solution, the values of all compartments and parameters are given in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Solution of all compartments for .

Figure 3.

Solution of all compartments for .

Figure 4.

Solution of all compartments for .

Table 1.

Numerical values of compartments and parameters.

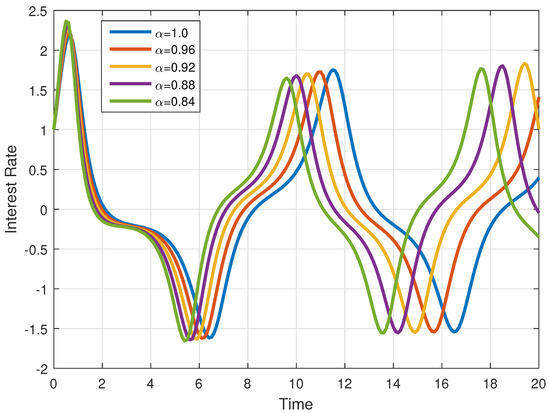

Figure 5.

Interest rate for various fractional orders .

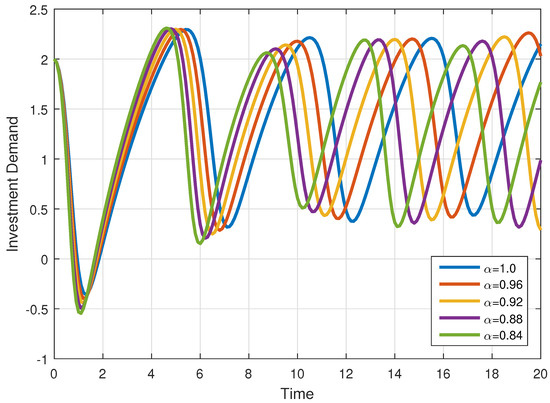

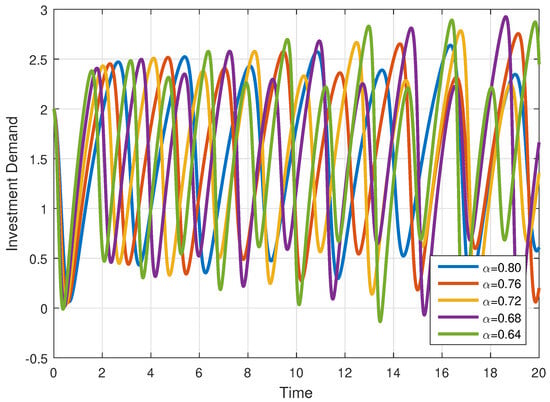

Figure 6.

Investment demand for various fractional orders .

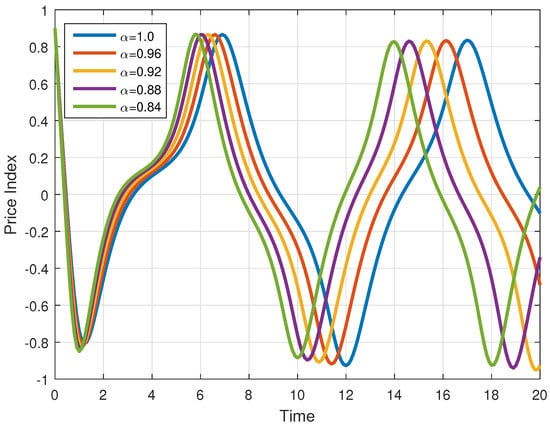

Figure 7.

Price index for various fractional orders .

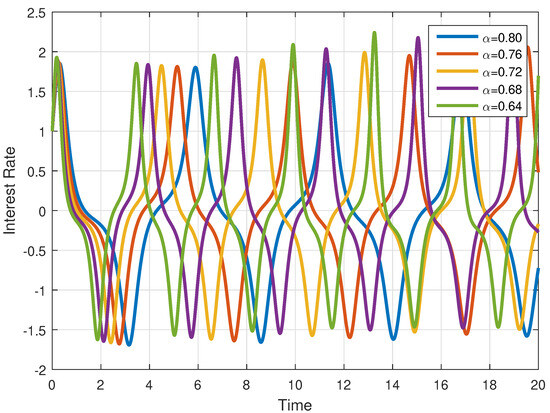

Further, for and , the solution of each compartment is simulated in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 8.

Interest rate for various fractional orders .

Figure 9.

Investment demand for various fractional orders .

Figure 10.

Price index for various fractional orders .

In Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, the solution of all compartments are presented for different fractional orders with the same step size . In Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, the solution of each variable is presented for various fractional orders with step size . Similarly, in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, the solution of each variable is presented for various fractional orders with step size . From these figures, we observe that when the fractional order , the trajectories are approaching the classical-order model () with weak memory, and when the fractional order is smaller, the system diverges from the classical order, causing the dynamics to oscillate more and to slow down, showing irregular behaviour. This means that when decreases, the curves exhibit oscillatory behaviour and slowed convergence. Hence, past data continue to affect current market activities. All variables of the model are influenced by the same fractional parameter, but they represent different financial thoughts and hence respond differently. Further, the numerical method we used in our analysis shows fast convergence for smaller values of the step size and larger values of the fractional parameter, while for large step sizes and lower values of the fractional parameter, the convergence of the method is slowed down significantly. Economically, when the values of fractional order increase, that is, when they tend to one, the memory becomes weak, and both interest rate and investment demand variables behave as integer-order models, producing less differences. For small values of fractional order , the memory becomes stronger, and the investment variable is impacted more by past incidents, whereas the interest variable stays more sensitive to sudden changes, producing divergence in the curves.

5. DNN Analysis of Our Model

This section is devoted to investigating the proposed model using DNNs. The reason for using DNNs is to provide an efficient way for approximating nonlinear fractional-order models. This method has the ability to capture the combined effects of many parameters in a very simple way. DNNs can approximate the solution of complex problems with more accuracy in less time. They can predict the solution of a system after generating a small perturbation in initial conditions, and due to their continuous approximation, the stability of the model can also be highlighted. The DNN concept was used in our study to accurately approximate the solutions of our proposed model since DNNs are excellent at learning from observed data. For one input, the corresponding output can be obtained by processing the data through multiple connected layers. We used 55 hidden layers with 47 neurons to produce a single output. We used the same structure for each compartment. To prevent over-fitting, different strategies were used, like early stopping, regularization, training/validation split, and data normalization. In Figure 11, we present the structure of a DNN.

Figure 11.

Diagram of a DNN.

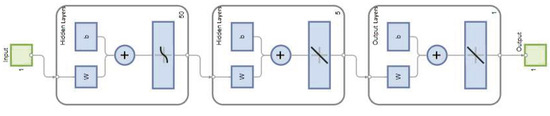

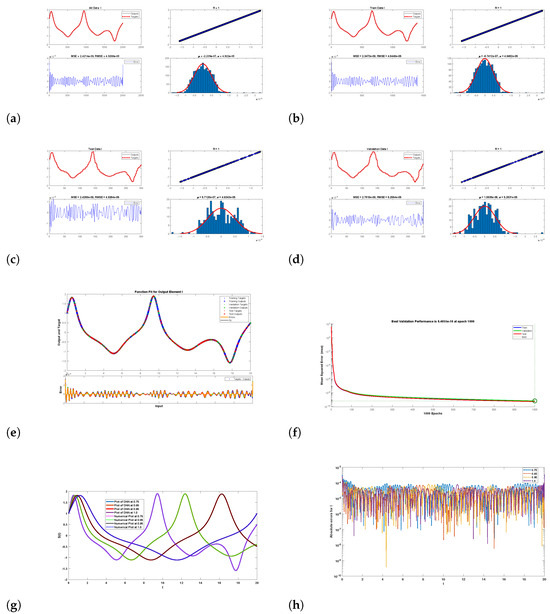

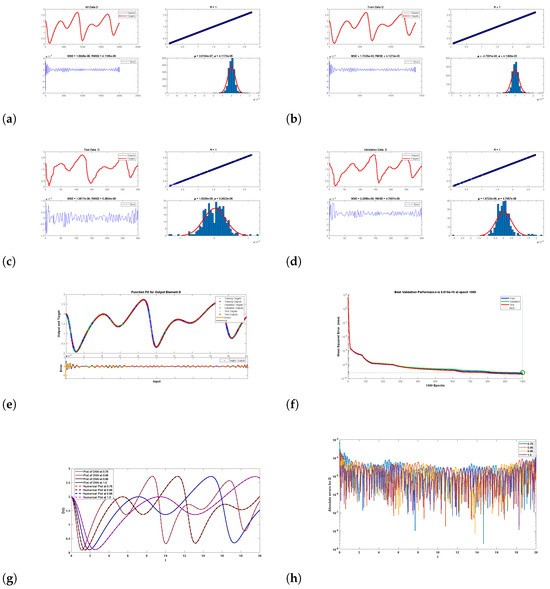

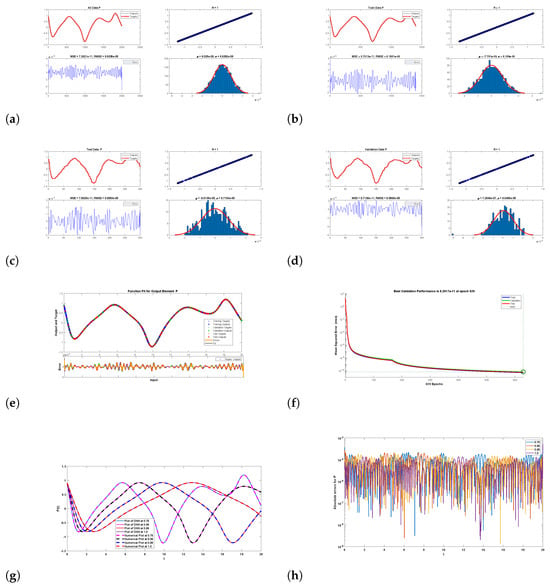

In the following, we present the analysis of the various compartments using DNNs. In Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, test data, validation data, training data, and all data together are presented with performance analysis and absolute errors.

Figure 12.

Graphical illustration of results when using DNNs for the investment class: (a) all data, (b) training data, (c) test data, (d) validation data, (e) best function fit for data of I, (f) performance analysis, and (g) comparison between predicted and numerical data. (h) Absolute error at various fractional orders.

Figure 13.

Graphical illustration of results when using DNNs for the demand class: (a) all data, (b) training data, (c) test data, (d) validation data, (e) best function fit for the data of D, (f) performance analysis, and (g) comparison between predicted and numerical data. (h) Absolute error at various fractional orders.

Figure 14.

Graphical illustration of results when using DNNs for the price index: (a) all data, (b) training data, (c) test data, (d) validation data, (e) best function fit for data of I, (f) performance analysis, and (g) comparison between predicted and numerical data. (h) Absolute error at various fractional orders.

In Figure 12, sub-figures (a)–(h), we provide the graphical representations of all data, training data, validation data, and test data using 1000 epochs. The initial value for the performance analysis was used by machine 36 with stopping value −10. The gradient’s initial value was 596, and the stopping value was −6 with a target value of −7. ’s starting value was , and its stopping value was −7 with a target value predicted as 10. At the target value, there were six validations checks. The absolute maximum error was found to be less than , which is a very small amount demonstrating that the numerical scheme was in close agreement with the data predicted by the DNNs.

In Figure 12, sub-figures (a)–(h), we provide the graphical representations of all data, training data, validation data, best function fit for class d, and a comparison of absolute errors at various fractional orders with the test data using 1000 epochs. The starting value for the performance analysis used by the machine was 38.8 with a stopping value of −10. The gradient’s initial value was and its stopping value was −7 with a target value of −7. ’s starting value was predicted to be , and its stopping value was with a target value predicted to be 10. At the target value, there were six validations checks. The numerical scheme was found to be in close agreement with the data predicted by the DNNs, because the absolute maximum error was less than , which is a very small amount.

Figure 14 and its sub figures (a)–(h) present various results including test data, all data, validation, and training data. Also, the comparison between numerical and predicted data are provided. The best function fit for class P and absolute errors at various fractional orders are presented. Theese results were obtained by using 629 epochs. The initial value for performance was 17.1, and the stopping value was −11. The gradient value was with a stopping value of −8 and a target value of −7. The value of was same in all three classes. The maximum absolute error was very small, less than , which shows that the predicted value and numerical value closely agreed.

6. Conclusions

From the above study, the conformable fractional operator provides a good mathematical way to model complex chaotic financial problems. Our study showed that the problem had at least one solution, a unique solution that was stable within the Ulam–Hyers framework. Also, the approximate solution of the model was simulated using matlab software version 2023. Therefore, the fractional concept can be applied to study mathematical problems in more realistic and accurate way. DNNs was utilized to investigate the financial model from different perspectives. We graphically presented various probabilistic measurements like the RMSE, MSE, regression coefficient, error histograms, and absolute errors for various fractional orders. The presented results showed that the numerical data closely agreed with the results predicted by DNNs. Although DNNs are important and find significant use in treating real-world problems, due to uncertainty in the data, finding an accurate DNN is still being pursued. In the future, the present study can be extended to nonlinear models of the real world. Many complex mathematical models can be studied under more generalized framework using time delays, nonlocal conditions, and advanced complex fractional operators like Caputo–Fabrizio, Atangana–Baleanu, -Hilfer, generalized Atangana–Baleanu, ensuring the existence, uniqueness, and Ulam–Hayer type stability of solutions, especially in financial systems with long-memory and hereditary effects. Such extensions will not only strengthen the theoretical base of the model but also offer a more accurate and realistic structure for examining complex financial models with delayed reactions and hereditary aspects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.J. and G.A.; methodology, G.A.; software, M.B.J.; validation, M.B.J. and G.A.; formal analysis, G.A.; writingorigi nal draft preparation, M.B.J.; writing review and editing, G.A.; funding acquisition, G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the deanship of scientific research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2504).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hsieh, D.A. Chaos and nonlinear dynamics: Application to financial markets. J. Financ. 1991, 46, 1839–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Ma, J. Chaos and Hopf bifurcation of a finance system. Nonlinear Dyn. 2009, 58, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Cai, L.; Cao, J. Linear control for synchronization of a fractional-order time-delayed chaotic financial system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2018, 113, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xie, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Fang, J.A. Chaos projective synchronization of the chaotic finance system with parameter switching perturbation and input time-varying delay. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2015, 38, 4279–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Cai, G.; Li, Y. Dynamic analysis and control of a new hyperchaotic finance system. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 67, 2171–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A.; Qureshi, S. Modeling attractors of chaotic dynamical systems with fractal–fractional operators. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 123, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toufik, M.; Atangana, A. New numerical approximation of fractional derivative with non-local and non-singular kernel: Application to chaotic models. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2017, 132, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A.; Koca, I. Chaos in a simple nonlinear system with Atangana–Baleanu derivatives with fractional order. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2016, 89, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammouch, Z.; Mekkaoui, T. Circuit design and simulation for the fractional-order chaotic behavior in a new dynamical system. Complex Intell. Syst. 2018, 4, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sene, N. Analysis of a fractional-order chaotic system in the context of the Caputo fractional derivative via bifurcation and Lyapunov exponents. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2021, 33, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghrebi, Y.S.; Raslan, K.R.; Abd El Salam, M.A.; Ali, K.K. A novel fractal-fractional approach to modeling and analyzing chaotic financial system. Res. Math. 2025, 12, 2468528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, A.; Tavakoli, H. Analysis and circuit simulation of a novel nonlinear fractional incommensurate order financial system. Optik 2016, 127, 10643–10652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Research on application of fractional calculus in signal real-time analysis and processing in stock financial market. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 128, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.B.; Jahanshahi, H.; Abba, O.A.; Solís-Pérez, J.E.; Bekiros, S.; Gómez-Aguilar, J.F.; Yousefpour, A.; Chu, Y.M. The effect of market confidence on a financial system from the perspective of fractional calculus: Numerical investigation and circuit realization. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 140, 110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalas, E.; Gorenflo, R.; Mainardi, F. Fractional calculus and continuous-time finance. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2000, 284, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullam, S.M. Problems in Modern Mathematics; Chapter VI; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Hyers, D.H. On the stability of the linear functional equation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1941, 27, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, X. A uniform method to Ulam–Hyers stability for some linear fractional equations. Mediterr. J. Math. 2016, 13, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.V.D.C.; de Oliveira, E.C.; Rodrigues, F.G. Ulam-Hyers stabilities of fractional functional differential equations. Aims Math 2020, 5, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.W. Generalized Ulam–Hyers stability for fractional differential equations. Int. J. Math. 2012, 23, 1250056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, M.; Shah, K.; Mofarreh, F.; Abdeljawad, T. Mathematical Modeling of Psychological Disease by Using Artificial Intelligence Tools. Fractals 2025, 34, 2550101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Jia, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, X.A.; Chen, F. Epi-DNNs: Epidemiological priors informed deep neural networks for modeling COVID-19 dynamics. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 158, 106693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Abdeljawad, T.; Abdalla, B.; Ali, Z. Analyzing a coupled dynamical system of materials recycling in chemostat systems with artificial deep neural network. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, A.; Çolak, A.B.; Sindhu, T.N.; Lone, S.A.; Alsubie, A.; Jarad, F. Comparative study of artificial neural network versus parametric method in COVID-19 data analysis. Results Phys. 2022, 38, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, M.; Shah, K.; Ali, Z.; Abdeljawad, T.; Alqudah, M. Using deep neural network in computational analysis of coupled systems of fractional integro-differential equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2025, 474, 116912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, M.; Shah, K.; Sarwar, M.; Alqudah, M.A.; Abdeljawad, T. Mathematical analysis of fractional order alcoholism model. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 78, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.R.; Mohapatra, S.N.; Jena, P. Variable-Order Conformable Fractional Derivatives using 2-stage Runge-Kutta and Euler Methods. Res. Sq. 2023; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).