Abstract

A modified Enzyme Action Optimizer (mEAO) is proposed to tune a Fractional-Order Proportional–Integral–Derivative (FOPID) controller for precise temperature regulation of a nonlinear continuous stirred tank reactor (CSTR). The nonlinear reactor model, adopted from a standard benchmark formulation widely used in CSTR control studies, is employed as the simulation reference. The tuning framework operates in a simulation-based manner, as the optimizer relies solely on the time-domain responses to evaluate a composite cost function combining overshoot, settling time, rise time, and steady-state error. Comparative simulations involving EAO, Starfish Optimization Algorithm (SFOA), Success History-based Adaptive Differential Evolution with Linear population size reduction (L-SHADE), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) demonstrate that the proposed mEAO achieves the lowest cost value, the fastest convergence, and superior transient performance. Further comparisons with classical tuning methods, Rovira 2DOF-PID, Ziegler–Nichols PID, and Cohen–Coon PI, confirm improved tracking accuracy and smoother actuator behavior. Robustness analyses under varying set-points, feed-temperature disturbances, and measurement noise confirm stable temperature regulation without retuning. These findings demonstrate that the mEAO-based FOPID controller provides an efficient and reliable optimization framework for a nonlinear thermal-process control, with strong potential for future real-time and multi-reactor applications.

1. Introduction

The continuous stirred tank reactor (CSTR) is a conventional reactor configuration widely used in chemical [1,2], pharmaceutical [3,4], energy [5,6], and other industries. A CSTR operates under steady-state conditions with continuous addition of substrates and withdrawal of products. Internal coils or external jackets are typically employed to maintain the desired reactor temperature by circulating heat-transfer fluid (HTF). To achieve the desired reaction process and product quality, as well as to mitigate the safety concerns (e.g., sudden temperature rises during exothermic reactions), it is critically important to utilize practical and robust control approaches to regulate the temperature of the reactor.

The on–off (bang–bang) control method is one of the earliest techniques used to regulate reactor temperature by simply opening or closing the HTF flow based on deviation from the setpoint [7,8]. Although this method is simple and cost-effective, it often results in poor control precision, especially in systems with long response delays, and frequent actuator switching can lead to mechanical wear. To address process delays and nonlinearities in the regulation, Model Predicted Control (MPC) has been employed for CSTR temperature regulation. This approach offers high adaptability and good performance by discretizing the control process and using multiple linearization techniques [9,10]. As a model-based control methodology, adaptive control has also been implemented for the regulation of reaction temperature [11,12]. The technique performed with zero steady-state error, even with the presence of noise, and characterized competitive resilience in coping with uncertainties in tracking the reference signal. Sliding Mode Control (SMC), another model-based approach, enables direct shaping of system dynamics through a defined sliding surface [13,14]. Owing to its fast response and simple design, SMC has been widely applied and further enhanced for CSTR temperature control. However, accurate modeling of the CSTR remains challenging due to its complex nonlinear dynamics, arising from coupled mass and heat-transfer processes [2]. Moreover, these model-based control schemes often require significant computational resources [15]. To overcome the dependence on detailed process models, intelligent control approaches have emerged in recent years for CSTR temperature regulation. Refs. [16,17] designed a fuzzy logic-based controller to adjust coolant flow and maintain reactor temperature with promising industrial applicability. Refs. [18,19] proposed a Neural Network-based controller to obtain high accuracy in temperature control by addressing unknown system dynamics through data training. In addition, Artificial Intelligence (AI) approaches, such as machine learning and reinforcement learning, have also been applied to develop efficient controllers for regulating CSTR temperature, achieving improved temperature regulation and reduced energy consumption [20,21]. Despite these advancements, large-scale industrial deployment of these intelligent control methods remains challenging due to high operational costs, data dependency, and maintenance requirements.

PID controllers are widely used across numerous industrial domains due to their simplicity, reliability, and ease of implementation [22,23]. Beyond chemical reactors, PID-based schemes play a central role in motor-speed regulation, electrical-machine drives, power-system excitation control, HVAC temperature management, fluid-flow regulation in pipelines, and liquid-level stabilization in storage tanks. Recent studies demonstrate the broad utility of PID and fractional-order PID variants in applications ranging from PMSM speed servo drives [24] to generator excitation control [25] and advanced HVAC temperature regulation in industrial environments [26]. However, efficient performance of the PID heavily depends on appropriate parameter tuning. To enhance control accuracy, numerous studies have explored powerful tuning techniques for PID controllers. Ref. [27] applied fuzzy logic theory to determine PID gain values and demonstrated that the fuzzy-based PID controller achieved superior setpoint tracking compared with the conventional PID and Ziegler–Nichols (ZN) methods. To further improve parameter identification and control precision, intelligent optimization algorithms have also been used. Ref. [28] integrated an improved Firefly Algorithm and an enhanced Sparrow Search Algorithm into the PID framework for the accurate control of CSTR temperature. A hybrid tuning method combining ZN based initialization with intelligent optimization algorithms was reported in [29]. The results showed that the controller parameters were best optimized by Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) irrespective of the disturbances compared with the Genetic Algorithm. The integration of Neural Network (NN) and PSO into the tuning of a PID controller was further investigated in [30]. The proposed PSO-tuned NN-PID controller achieved faster rise time, reduced overshoot, and shorter settling time than both NN-PID controller and conventional ZN-tuned PID controller. In [31], a nonlinear PID controller combined with a Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN) was proposed for CSTR temperature control. Simulation studies demonstrated notable improvements in setpoint tracking, disturbance rejection, and parameter variation compared with the adaptive RBFNN-based PID controller.

Recently, fractional-order PID (FOPID) controllers have emerged as promising alternatives to the classical control method in the industry [32]. Compared to the conventional integer-order (IO) PID controllers, the FOPID controller possesses more tuning freedom and wider range of parameters for stable control, leading to the improvement in control robustness [22,33]. In this context, the FOPID has been adopted for stabilizing the temperature of the CSTR and to maintain optimal reaction processes. Ref. [34] developed an efficient FOPID controller tuned by a Modified Grey Wolf Optimizer (MGWO) to regulate the temperature of a CSTR. Comparative results showed that the proposed MGWO-FOPID achieved a significantly lower fitness value compared with the conventional GWO-PID controller. In [35], four different structures of FOPID were proposed by combining NN and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), and the robustness of these controllers was investigated. The findings demonstrated that the FOPIDNN controller with a three-layer structure had a decent ability to rapidly minimize the variance between real and desired routes. Ref. [36] investigated the hybridization of the State of Matter Search (SMS) algorithm with chaotic maps and elite oppositional-based learning. This hybrid algorithm was used to find optimal parameters of the FOPID controller for the temperature control of a CSTR and presented superior and optimum performance compared with FOPID controllers based on SMS-FOPID, PSO-FOPID, and Cuckoo Search (CS). Although these approaches improve transient performance, most existing optimizers either converge prematurely or exhibit limited precision near the optimal region when applied to strongly nonlinear thermal systems.

Recent studies have shown that the original Enzyme Action Optimizer (EAO), although competitive, exhibits several structural limitations, including early loss of population diversity, weak exploitation near the optimum, and stagnation in flat or shallow regions of the search landscape. These issues reduce its reliability when applied to strongly nonlinear thermal systems such as CSTR temperature regulation, which demand both reliable global exploration and precise local refinement.

To address these limitations, this study introduces a modified Enzyme Action Optimizer (mEAO) that incorporates four dedicated enhancements:

- A sinusoidal adaptive factor for dynamic step-size modulation;

- Randomized enzyme concentration to enhance population diversity;

- A dual-candidate update strategy for reinforced exploitation;

- A lightweight local search step for fine-grained refinement.

These mechanisms are absent in the original EAO and collectively enhance both global search capability and local convergence precision in nonlinear thermal systems. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of an enhanced EAO variant for tuning FOPID controllers in CSTR temperature regulation. Additionally, a complete simulation-based tuning framework is constructed using normalized multi-objective performance metrics, supported by extensive comparative and robustness analyses, which further reinforce the methodological contribution of this work.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the nonlinear CSTR model and its parameters. Section 3 describes the structure and implementation of the FOPID controller. Section 4 introduces the proposed mEAO algorithm, while Section 5 outlines the mEAO-based FOPID control framework. Section 6 and Section 7 provide comparative simulation and robustness analyses, respectively. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

2. Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor

A CSTR represents one of the most fundamental configurations in chemical and process industries for investigating reaction dynamics under continuous operation [37]. It is composed of a well-mixed vessel in which the reactant stream enters at a constant volumetric flow rate, while the outlet stream leaves at the same rate, maintaining a constant liquid level inside the reactor. Such a configuration ensures spatial homogeneity, meaning that the composition and temperature of the effluent are identical to those within the reactor bulk. This “perfect-mixing” assumption allows the CSTR to serve as an idealized benchmark system for studying nonlinear thermal behavior and for developing and validating advanced control algorithms.

The reactor considered in this study performs an irreversible, first-order exothermic reaction in the liquid phase. The system is equipped with an external cooling jacket surrounding the vessel, through which a heat-exchange medium circulates to remove the heat released during the chemical reaction. The cooling jacket acts as the manipulated unit of the process, by regulating the coolant temperature or flow rate, the rate of heat removal can be adjusted, thereby maintaining the reactor temperature within safe and optimal limits. Because of the strong coupling between the reaction rate and the temperature, the CSTR exhibits highly nonlinear behavior and may possess multiple steady-state solutions, including regions prone to thermal runaway if the temperature is not tightly controlled.

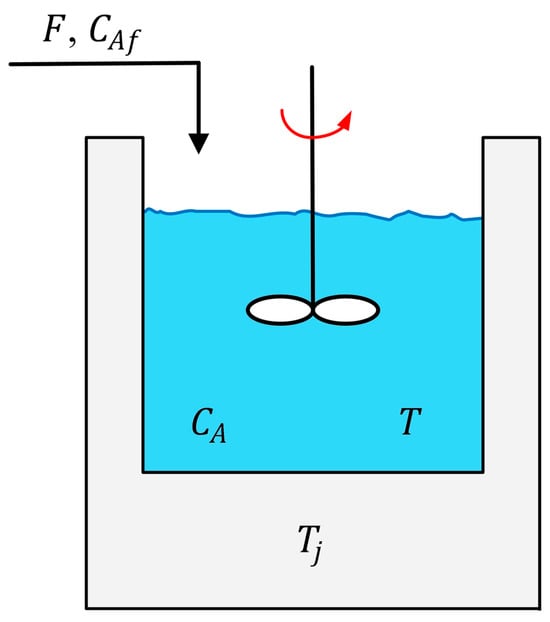

A schematic representation of the jacketed CSTR considered in this work is shown in Figure 1, where the main process variables (reactor temperature, reactant concentration, and jacket temperature) are indicated. The thermal dynamics of this configuration form the basis for the development of the mathematical model presented in the following subsection, which is later utilized for controller design and performance evaluation.

Figure 1.

Continuous stirred tank reactor with cooling jacket.

2.1. Mathematical Modeling

To capture the nonlinear dynamic behavior of the reactor, material and energy balance equations are formulated under several realistic yet simplifying assumptions. The liquid phase is perfectly mixed, so the temperature and composition are spatially uniform. Physical properties such as density, specific heat, and overall heat-transfer coefficient are considered constant. The reaction follows a first-order, irreversible, exothermic mechanism of the form A → B and vapor-phase effects are neglected. In addition, the reactor volume remains constant due to the equality between inflow and outflow rates. The cooling-jacket temperature

is regarded as the manipulated variable and is assumed to respond much faster than the reactor temperature, allowing its dynamic behavior to be represented as a direct input.

The rate of reaction per unit volume is described by the Arrhenius law:

where r is the reaction rate,

is the pre-exponential factor, E is the activation energy, R is the universal gas constant, T is the reactor temperature, and

is the concentration of the reactant.

Applying the principle of conservation of mass to component A and conservation of energy to the reactor contents yields the following nonlinear differential equations that govern the transient behavior of the system:

where the parameters are defined as follows: F is the volumetric feed flow rate, V is the reactor volume,

and

are the feed concentration and feed temperature,

is the density of the reacting fluid,

is the specific heat capacity,

is the heat of reaction (negative for exothermic systems),

is the overall heat-transfer coefficient, and A is the heat-exchange surface area. The last term in Equation (3) represents the heat transferred through the reactor wall to the cooling jacket, which serves as the thermal control mechanism.

Equations (2) and (3) jointly describe the nonlinear coupling between concentration and temperature. The exponential temperature dependence of the reaction rate introduces significant sensitivity and potential multiplicity of steady states. Even small perturbations in jacket temperature or feed conditions can cause abrupt changes in the reactor temperature, making accurate temperature control essential for maintaining safe and efficient operation. These nonlinear characteristics make the CSTR a canonical testbed for advanced controller design and optimization studies.

2.2. Model Parameters and Nominal Conditions

The physical, thermal, and kinetic parameters adopted in this work are summarized in Table 1. They correspond to a standard benchmark scenario frequently used in CSTR temperature-control studies [37,38].

Table 1.

Physical and kinetic parameters of the CSTR and its steady-state operating point.

The computed steady-state operating conditions—obtained by setting

and

in Equations (2) and (3)—are T = 304.17 K and CA = 0.9774

. These serve as the nominal equilibrium point around which the control system performance is evaluated in subsequent simulations.

3. Structure of FOPID Controller

The FOPID control (also expressed as

) extends the conventional PID framework by allowing the integral and derivative operators to assume non-integer orders

and

. This generalization introduces two additional tuning parameters that significantly enlarge the stabilizing region and enable refined frequency-response shaping. By tuning the fractional orders

and

, the open-loop phase response of a FOPID controller can be made locally flatter near the gain-crossover frequency, achieving the iso-damping effect in which the closed-loop overshoot remains almost constant for moderate variations in the loop gain [39]. This phase-flattening capability helps maintain the desired phase margin and transient damping under parametric uncertainty. When designed with suitable filtering of the fractional-derivative path, such controllers provide improved robustness compared with classical PID schemes [40]. These attributes have motivated the growing use of FOPID controllers in industrial applications, including electromechanical drives, process–thermal systems, and other nonlinear plants, where wide-range robustness and precise frequency-domain tuning are of particular importance [40,41].

The continuous-time FOPID controller in parallel form

is written as

where

,

, and

denote the proportional, integral, and derivative gains in the Laplace domain, respectively. The parameters

and

represent the fractional orders of integration and differentiation. The conventional integer-order PID controller is recovered when

, while the other classical forms (for P is

, PI is

, and PD is

) arise as special cases for appropriate values of λ and μ.

Exact implementation of the fractional operators

and

is not directly realizable in finite-dimensional systems because they correspond to non-local, memory-dependent dynamics. In practice, band-limited rational approximations are used. The most widely adopted method is the Oustaloup recursive filter, which distributes poles and zeros logarithmically over a defined frequency band to emulate the desired fractional slope while maintaining stability [42]. The resulting approximation can then be discretized for embedded or digital realization. Typical industrial implementations employ moderate filter orders (e.g.,

pole-zero pairs with

) within the operating-frequency range, which keeps the computational cost modest relative to modern controller hardware. In this study, an 11th-order (

) Oustaloup recursive approximation was implemented within the frequency band

rad/s, which is a commonly adopted range in FOPID applications to ensure accurate representation of the fractional dynamics across the controller’s operating spectrum. A block diagram of the FOPID controller is shown in Figure 2.

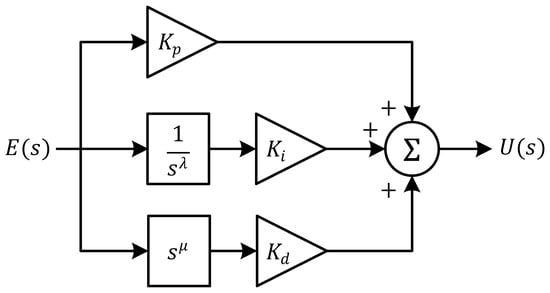

Figure 2.

Block diagram of FOPID controller.

The error signal,

, is processed in three parallel paths: the proportional path

, the fractional-integral path

, and the fractional-derivative path

. The outputs of these paths are summed to produce the control signal

. In actual implementation, each fractional path is replaced by a stable, band-limited rational filter (e.g., Oustaloup) before discretization. This parallel architecture preserves the intuitive structure of classical PID, while embedding fractional dynamics that enhance tuning flexibility and disturbance robustness.

In the context of the CSTR, the closed-loop objective is to maintain the reactor temperature within safe bounds despite rapid and nonlinear heat-release dynamics. The two fractional orders ( and

) introduce additional degrees of freedom that allow precise phase and gain shaping of the loop, resulting in improved disturbance rejection and reduced actuator effort compared with an integer-order PID. Moreover, the FOPID’s ability to sustain nearly constant damping across a wide operating range mitigates oscillatory and unstable behavior, ensuring smoother thermal responses. Recent studies [40,41] have shown that these attributes make fractional-order controllers particularly well suited for industrial thermal processes such as CSTR systems, where robustness and energy efficiency are critical.

Despite their enhanced flexibility, FOPID controllers also introduce certain practical complexities. Accurate selection of the fractional orders

and

increases the computational burden, and rational approximation of fractional operators may introduce modeling errors outside the designed frequency band. If these approximations or tuning ranges are not properly handled, the closed-loop performance can degrade, particularly in highly nonlinear systems.

4. Proposed Modified Enzyme Action Optimizer (mEAO)

4.1. Overview of the Original EAO Algorithm

The Enzyme Action Optimizer (EAO) is a bio-inspired metaheuristic that imitates the catalytic behavior of enzymes during biochemical reactions. In biological systems, enzymes accelerate reactions by binding selectively to substrates and lowering the activation energy required for transformation. This adaptive catalytic process, capable of maintaining high efficiency under different environmental conditions, forms the conceptual basis of EAO, which dynamically balances global exploration and local exploitation within a multidimensional search space [43].

EAO starts with a population of N candidate solutions, called substrates, each representing a potential point in the decision space. The

substrate is randomly initialized within its lower () and upper (

) bounds as

where ri is a uniformly distributed random vector in

and

denotes element-wise multiplication. The fitness of each substrate is evaluated by the objective function

and the best candidate

is designated as the enzyme that guides subsequent updates.

During iteration t, an adaptive factor controls the transition from exploration to exploitation and is expressed as

where t is the current iteration number and

represents the maximum number of iterations. The value of

increases monotonically, leading to finer convergence as the search proceeds.

Each substrate generates two trial solutions:

- 1

- Sine-based exploitation step:

- 2

- Difference-based exploration step:

The better of the two candidate positions replaces the previous substrate:

The global best

is updated whenever a superior fitness value is found, and boundary control ensures every component

remains within

.

The computational complexity of EAO is

where M is the maximum number of reactions, N the population size, d the problem dimension, and F the cost of a single objective-function evaluation.

Through its dual-update strategy and adaptive regulation via

and EC, EAO achieves a smooth transition from global exploration to refined exploitation. These mechanisms provide strong global search capability, rapid convergence, and robustness against local minima, making EAO an effective optimizer for engineering applications such as controller tuning and system identification [43].

4.2. Proposed Modification and Mechanism

This study proposes a modified Enzyme Action Optimizer (mEAO) that enhances the baseline EAO (Section 4.1) by improving convergence precision, maintaining diversity, and stabilizing solution quality.

The mEAO introduces four lightweight yet effective enhancements:

- •

- A sinusoidally varying adaptive factor;

- •

- A randomized enzyme concentration schedule;

- •

- An improved dual-candidate generation strategy;

- •

- A lightweight local search applied to the best solution.

4.2.1. Sinusoidally Adaptive Factor

At iteration

, the adaptive factor

is defined as

where

denotes the maximum number of iterations (equivalently, the maximum number of reactions in the algorithmic cycle). Unlike the monotonic schedule used in the original EAO, this sinusoidal modulation periodically varies exploration intensity, enabling wide exploration in the early phase and refined exploitation near convergence.

4.2.2. Randomized Enzyme Concentration

To avoid premature convergence and maintain population diversity, the enzyme concentration factor becomes iteration-dependent:

where

. Thus

, providing bounded stochastic variation that dynamically scales the coefficients used in candidate generation. The adaptive

enables the optimizer to self-adjust its search radius according to the landscape topology.

4.2.3. Candidate Generation and Selection

For each substrate

in the population

, two candidate solutions are produced, and the best one replaces

- 1

- First candidate (exploration-oriented):

- 2

- Second candidate (differential update):

Two distinct indices

are selected, and two trial vectors are formed:

where

and

are D-dimensional random vectors generated per dimension to introduce directional exploration, whereas

and

are scalar coefficients drawn uniformly from

, enabling a uniform contraction/expansion step for exploitation.

After evaluation, the better vector between A and B is selected as

. The substrate updates as follows:

with boundary enforcement:

This dual-update mechanism strengthens both diversification and exploitation without enlarging the population.

4.2.4. Lightweight Local Search Around

At the end of each iteration, a fine local refinement is performed around

:

If

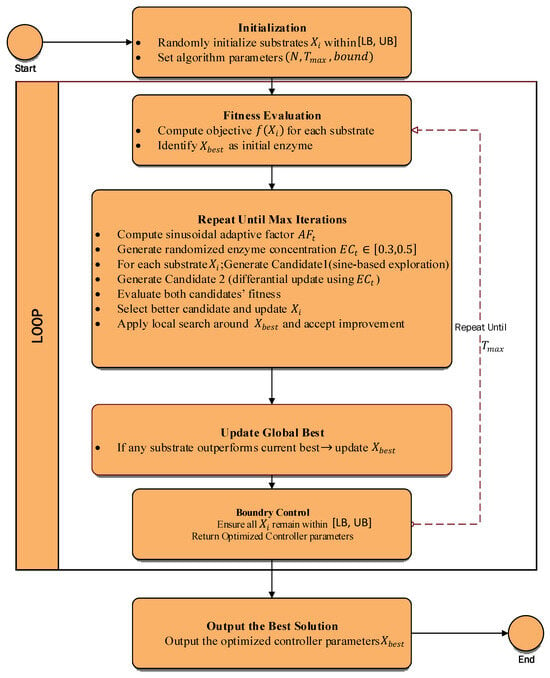

, the new candidate is accepted. This step introduces subtle exploitation capability with negligible computational cost. The flowchart of the mEAO algorithm presented in Figure 3. The algorithm begins with random initialization and fitness evaluation of substrates, followed by iterative updates controlled by

and

. Two candidate solutions are generated at each iteration, the

is updated, and a lightweight local search is applied to enhance convergence before termination.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of proposed mEAO algorithm.

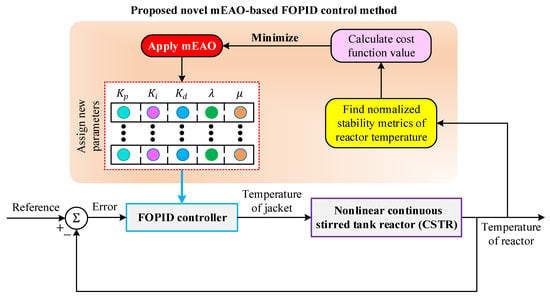

5. Proposed mEAO-Based FOPID Control Method

In the present study, the nonlinear CSTR model described in Section 2 was controlled by a FOPID controller whose parameters were optimally tuned using the mEAO. The overall optimization and control framework is illustrated in Figure 4, showing the interaction between the optimizer, the FOPID controller, and the reactor model.

Figure 4.

Proposed novel mEAO-based FOPID control method.

As shown in Figure 4, the error signal (“Error”) is obtained as the difference between the reference and the actual reactor temperature. The FOPID controller processes this error and generates the temperature setpoint for the cooling jacket. Accordingly, the controller output corresponds to the “Temperature of jacket”, while the closed-loop system output is the “Temperature of reactor”. This cascaded thermal interaction, where the manipulated variable is the jacket temperature and the controlled variable is the reactor temperature, forms a closed-loop structure typical of practical CSTR temperature regulation systems. Unity feedback is used (confirming that no additional gain is required in the feedback path), which is consistent with standard thermal CSTR control architectures [44].

At the initial operating point, the reactor temperature was T = 304.16755 K. To evaluate the transient and steady-state performance of the designed control system, the reference temperature was increased by

at

, i.e., to

. This step-change scenario allowed the investigation of the controller’s ability to reject the strong nonlinearity and heat-release dynamics of the exothermic reaction.

The tuning objective was to determine the optimal set of FOPID parameters () that minimize a composite performance index as formulated in [45,46]. The employed cost function is given by

The balance factor was fixed at

, consistent with previous work [47], which showed that this value provides a stable and well-defined weighting between transient and steady-state performance terms. Therefore,

is not treated as an additional optimization variable in this study. Here,

represents the normalized percent overshoot,

the normalized steady-state error (evaluated at

),

the normalized settling time within a ∓2% tolerance band and

the normalized rise time. A lower

value corresponds to faster response, smaller overshoot, and better steady-state accuracy, thereby ensuring both stability and energy-efficient thermal control. This composite structure is adapted from time-domain performance indices commonly used in PID/FOPID tuning, particularly the formulations presented in [45,47].

During optimization, the mEAO algorithm iteratively adjusts the FOPID gains based on the feedback obtained from the reactor-temperature response. Each candidate parameter set is evaluated by simulating the CSTR system and computing its

value. The best-performing set is preserved as the global best, and the process continues until the termination criterion () is reached. Once convergence is achieved, the optimal FOPID parameters are applied to the closed-loop system for verification.

The parameter search ranges used in this study are summarized in Table 2. These limits were determined empirically to ensure system stability and adequate search-space diversity during the mEAO optimization process.

Table 2.

Search-space boundaries for FOPID controller parameters tuned by the proposed mEAO.

The mEAO algorithm minimizes the cost function

to optimally tune the controller parameters based on the normalized dynamic performance metrics of the reactor temperature. The obtained optimal controller parameters will be validated through comparative simulations in Section 6 and robustness analysis under various disturbances as presented in Section 7.

6. Comparative Simulation Results

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed mEAO-based FOPID controller, extensive comparative simulations were carried out against four benchmark optimizers-EAO [43], SFOA [48], L-SHADE [49], and PSO [46]. Each algorithm was executed for 25 independent runs with a population size of 30 and a maximum of 100 iterations to ensure a fair comparison. All simulations were performed using identical CSTR model parameters and cost-function settings defined in Section 5.

6.1. Statistical Verification

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison, the parameter settings of all benchmark algorithms were standardized. Table 3 summarizes the population size, total iteration count, and method-specific hyperparameters used for EAO, SFOA, L-SHADE, and PSO. These parameter choices follow the recommendations of the original studies for each optimizer and are consistent with typical configurations used in control-oriented metaheuristic benchmarking.

Table 3.

Parameter settings for compared algorithms.

The statistical results of the 25 independent runs are summarized in Table 4, which reports the best, worst, mean, and standard deviation (SD) values of the cost function

. Among the tested algorithms, mEAO yielded the lowest best, worst, and mean values (0.3993, 0.4118, and 0.4040, respectively), and the smallest SD (0.0031), demonstrating both superior accuracy and remarkable repeatability.

Table 4.

Statistical comparison of cost-function results over 25 runs.

EAO ranked second, whereas the remaining algorithms (SFOA, L-SHADE, PSO) exhibited higher dispersion, implying less stable convergence behavior. These findings verify that the proposed modifications introduced in mEAO successfully enhance exploration–exploitation balance and convergence reliability.

In addition, a compact ablation analysis was conducted to isolate the contribution of the added mechanisms. Two reduced variants of mEAO (one without the sinusoidal adaptive factor and one without the lightweight local search) were evaluated. Both variants exhibited noticeably slower convergence and higher stagnation frequency compared with the full mEAO design. These results confirm that the introduced components contribute measurably to convergence reliability and local refinement.

To statistically validate the performance differences among the algorithms, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted. This non-parametric test evaluates whether mEAO offers a better cost-function value than the benchmark optimizers. Table 5 summarizes the p-values and statistical winners for all pairwise comparisons.

Table 5.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test-based performance evaluation.

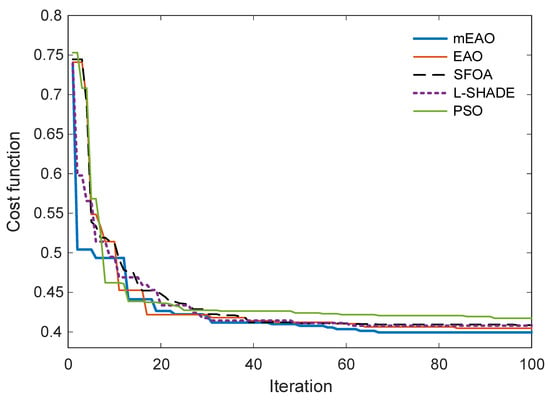

The convergence characteristics of

across iterations are presented in Figure 5. All algorithms show a rapid decline in the early stages, yet the mEAO curve achieves the minimum cost earlier and remains consistently below the others throughout the entire 100-iteration horizon. This behavior confirms that mEAO converges faster and avoids premature stagnation commonly observed in standard metaheuristics such as PSO and L-SHADE.

Figure 5.

Convergence of

cost function for different optimization algorithms.

The optimal FOPID parameters obtained by each algorithm after convergence are provided in Table 6. The parameter values show that mEAO-based tuning produces balanced gain distributions with slightly higher integral and fractional-derivative coefficients, indicating stronger steady-state precision and smoother transient response. By contrast, EAO- and SFOA-based designs required comparatively larger derivative terms, which may lead to higher control effort.

Table 6.

Optimized FOPID parameter values obtained by different algorithms.

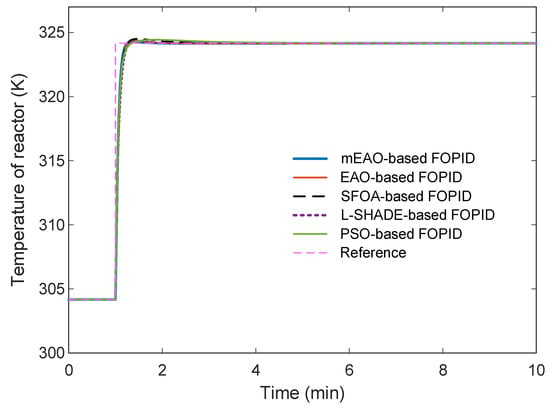

6.2. Closed-Loop Response

The closed-loop temperature-control responses of the nonlinear CSTR system are depicted in Figure 6, where the reactor temperature rises from 304.17 K to 324.17 K following a 20 K reference step at

. All controllers achieve stable tracking; however, the proposed mEAO-based FOPID exhibits the fastest settling and the smallest overshoot.

Figure 6.

Time-response comparison of reactor temperature for different algorithms.

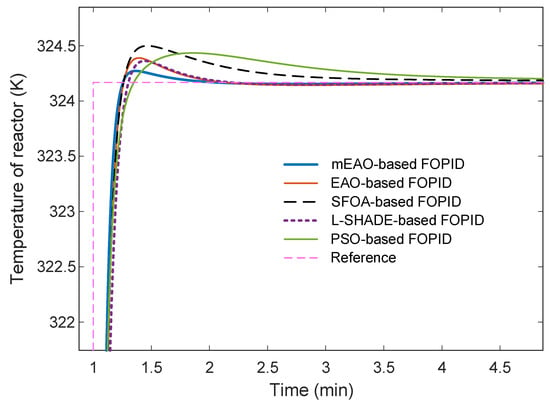

To highlight the transient differences, a zoomed-in view of the same response is shown in Figure 7, revealing that mEAO achieves a smoother rise and lower peak deviation than the other methods.

Figure 7.

Zoomed-in view of reactor-temperature transient.

Quantitative performance indices derived from these responses are listed in Table 7, including the normalized rise time (), settling time (), overshoot (), peak time (), and steady-state error (). mEAO-based FOPID yields the lowest values in every category, specifically, the smallest normalized rise time (0.115 min) and overshoot (0.5222%), which indicate rapid and well-damped operation. These metrics confirm that the proposed controller achieves a superior compromise between fast tracking and minimal overshoot compared to EAO-, SFOA-, L-SHADE-, and PSO-based FOPID designs.

Table 7.

Comparison of normalized transient-performance indices for different algorithms.

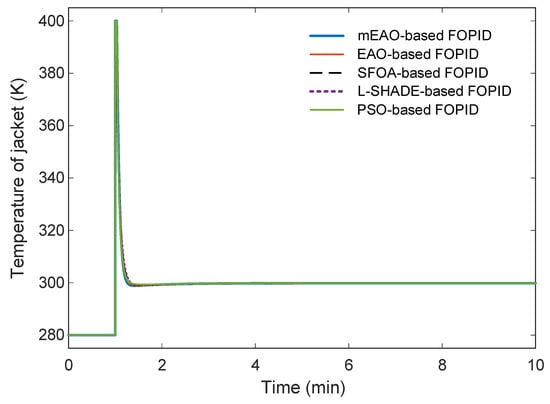

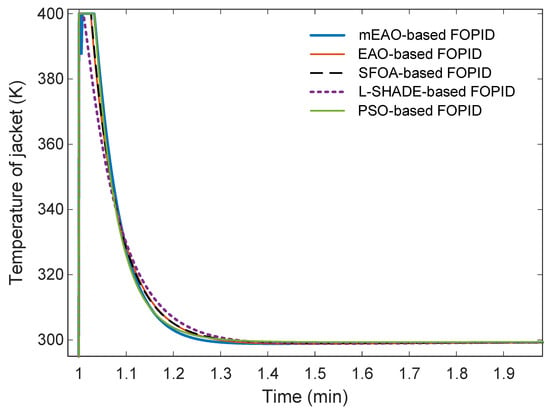

The controller-output trajectories presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9 demonstrate that all optimization algorithms yield almost identical jacket-temperature responses, indicating highly similar control efforts. The mEAO-based FOPID controller, represented by the blue curve, exhibits a slightly smoother transient with minimal fluctuation at the start of the response. Although the differences among all methods are marginal, the mEAO-tuned controller maintains marginally improved smoothness without inducing additional actuator stress.

Figure 8.

Time response of controller output (temperature of jacket).

Figure 9.

Zoomed-in view of controller-output response.

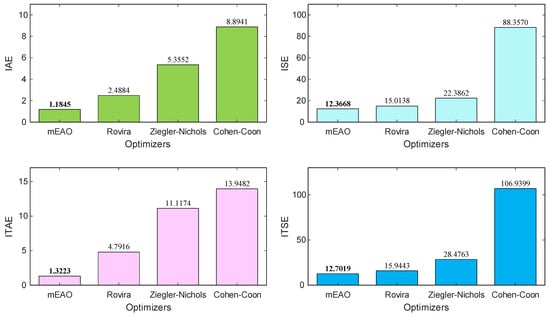

6.3. Error-Based Performance Indicators

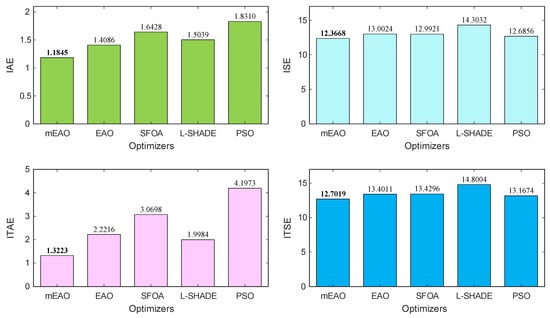

To provide a quantitative assessment of control quality beyond transient indices, four classical error-based performance indicators were employed: Integral of Absolute Error (IAE), Integral of Squared Error (ISE), Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error (ITAE), and Integral of Time-weighted Squared Error (ITSE). These indices evaluate the accumulated Error between the reference signal and the actual reactor temperature over the simulation period. Each index captures different aspects of control behavior, such as energy efficiency, smoothness, and sensitivity to long-term deviations.

The corresponding mathematical formulations are expressed as follows:

where

denotes the simulation duration.

The results obtained for all optimization algorithms are depicted in Figure 10. Among the five tested approaches, the mEAO-based FOPID controller achieved the lowest values across all four indices, demonstrating superior tracking precision and control effort efficiency. In particular, the minimum IAE (1.1845) and ITAE (1.3223) values confirm that mEAO delivers faster convergence to steady states with minimal sustained error. Similarly, the smallest ISE (12.3668) and ITSE (12.7019) values indicate reduced energy consumption in error correction, reflecting smoother and more economical control actions. Although the differences among other methods are moderate, mEAO consistently provides the most balanced performance without sacrificing response speed or robustness.

Figure 10.

Visual comparison of error-based performance indicators for different optimization algorithms.

6.4. Comparison with Classical Methods

For further validation, the proposed mEAO-based FOPID controller was compared with three conventional tuning strategies: Rovira-based 2DOF-PID, Ziegler–Nichols-based PID, and Cohen–Coon-based PI controllers. The two-degrees-of-freedom (2DOF) controller provides additional setpoint weighting flexibility, allowing independent adjustment of tracking and disturbance-rejection characteristics.

The relationship between the controller output

and its two inputs

and

can be expressed in parallel form [50]:

where

is the derivative-filter time constant, b denotes the setpoint weight on the proportional term, and c is the setpoint weight on the derivative term. When

, Equation (23) reduces to the standard PID structure, and by further setting

, a classical PI controller is obtained. Detailed derivations of these formulations can be found in Rovira et al. [51], Ziegler–Nichols [52], and Cohen–Coon [53].

The numerical parameters for each classical controller are summarized in Table 8. The Rovira-based 2DOF-PID includes additional proportional and derivative weights ( and

) to enhance setpoint tracking, while the Ziegler–Nichols and Cohen–Coon methods rely on empirical step-response tuning.

Table 8.

Parameter values of classical control methods.

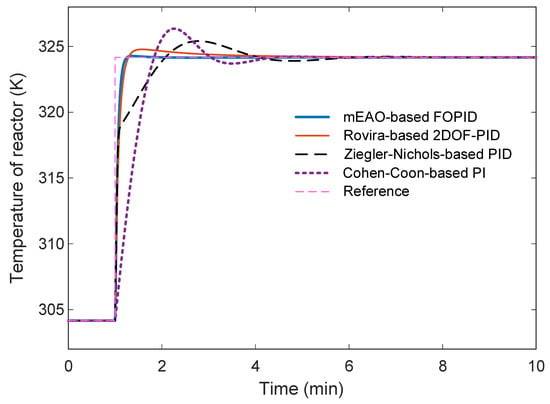

The closed-loop reactor-temperature responses of these three controllers were compared with the proposed mEAO-based FOPID system, as depicted in Figure 11. All controllers achieve stable tracking of the 20 K temperature increase, yet the mEAO-based FOPID (blue curve) exhibits a faster rise and notably reduced overshoot compared with the classical designs. The Cohen–Coon based PI shows the largest overshoot, while the Ziegler–Nichols PID yields the slowest response of rise time.

Figure 11.

Time response of reactor temperature for the proposed and classical control methods.

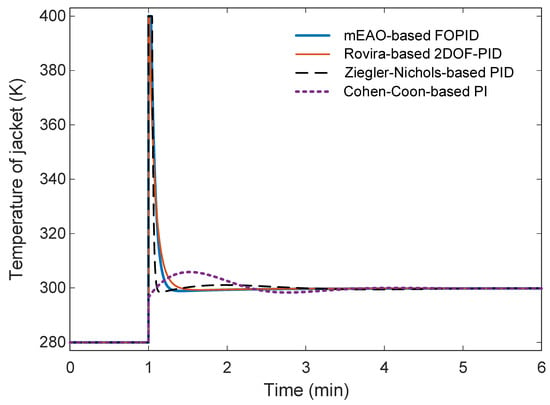

The corresponding controller-output profiles (jacket-temperature trajectories) are illustrated in Figure 12. All controllers display similar transient behavior, but the mEAO-based FOPID and Rovira 2DOF-PID generate smoother control signals with lower amplitude variations, implying more stable actuation.

Figure 12.

Time response of controller output (jacket temperature).

Quantitative transient-performance indices are listed in Table 9, including normalized rise time (), settling time (), overshoot (), peak time (), and steady-state error (). The proposed controller achieved the lowest

(0.115 min) and

(1.1914 min), together with a minimal

(0.5222%), demonstrating significantly faster and better-damped dynamics than all classical counterparts. The Rovira-based 2DOF-PID ranked second in performance, benefiting from its additional tuning parameters, whereas Ziegler–Nichols and Cohen–Coon controllers exhibited slower settling and higher overshoot.

Table 9.

Comparative transient-performance indices of the proposed and classical controllers.

Error-based indicators computed for each controller are visually summarized in Figure 13. The mEAO-based FOPID achieves the lowest IAE, ISE, ITAE, and ITSE values, confirming its superior overall precision and energy efficiency. In particular, the smallest ITAE (1.3223) and ITSE (12.7019) reflect both rapid error decay and minimal sustained oscillation, whereas classical tuning approaches accumulate considerably higher error magnitudes, especially the Cohen–Coon PI.

Figure 13.

Visual comparison of performance indicators between the proposed and classical methods.

7. Robustness Analysis of mEAO-Based FOPID Controller

The robustness of the optimized controller was assessed under three practical scenarios: reference variations, feed-temperature disturbances, and measurement-noise injection. The aim was to evaluate the controller’s ability to maintain satisfactory reactor-temperature regulation without retuning.

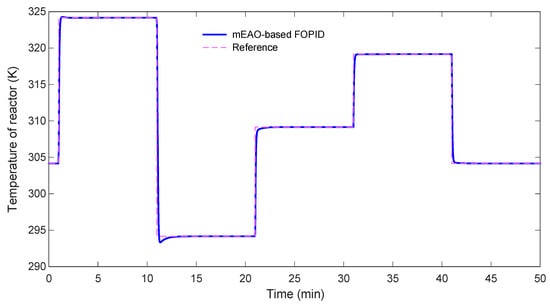

7.1. Tracking Performance Under Varying References

To verify reference-tracking capability, the setpoint of the reactor temperature was changed successively following this path: 304 K → 324 K → 294 K → 309 K → 319 K → 304 K, as illustrated in Figure 14. The proposed mEAO-based FOPID controller (blue curve) follows all reference levels with negligible steady-state error and smooth transitions. No significant overshoot or undershoot occurs even after large amplitude changes, confirming that the fractional-order structure tuned by the improved hybrid optimizer provides sufficient phase-margin preservation across the operating range. These results demonstrate the controller’s strong adaptability and its capability to preserve accuracy under continuously varying operating points.

Figure 14.

Reference-tracking performance of the mEAO-based FOPID controller for multiple setpoint changes.

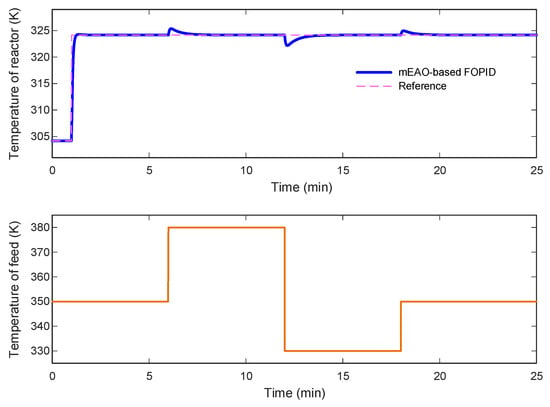

7.2. Disturbance Rejection

In real CSTR systems, the feed temperature

often exhibits unpredictable variations that act as thermal disturbances. To test disturbance-rejection ability, a sequence of step-type

changes was introduced while maintaining a constant reactor-temperature reference.

The upper subplot of Figure 15 shows that the reactor temperature rapidly returns to its nominal value after each disturbance, while the lower subplot displays the imposed

profile. Despite abrupt ∓25 K feed-temperature shifts, the controller suppresses deviations within a few seconds, preventing any sustained offset. This confirms the proposed mEAO-based FOPID controller’s superior rejection capability against external heat-input perturbations.

Figure 15.

Disturbance rejection against feed-temperature fluctuations.

To complement the visual robustness results, integral error indices were evaluated to provide a quantitative performance comparison under disturbance rejection. Table 10 reports the IAE, ISE, ITAE, and ITSE values for all controllers. The proposed mEAO-based FOPID achieves the lowest values across all four metrics, indicating faster error decay, improved disturbance suppression, and smoother long-term tracking performance compared with the alternative methods.

Table 10.

Comparison of error-based performance indicators in the case of disturbance rejection.

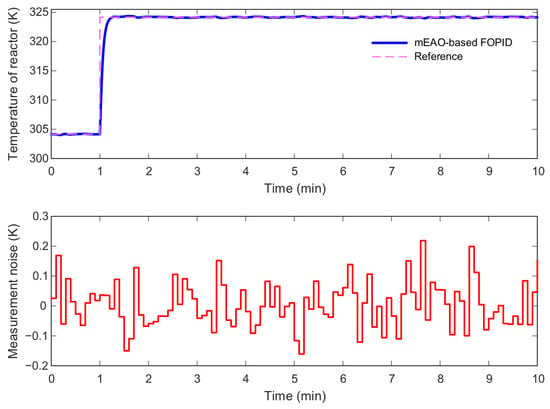

7.3. Noise Attenuation Capability

Measurement noise is inevitable in temperature sensors, especially in industrial environments. To assess noise robustness, a zero-mean random noise signal (∓0.2 K amplitude) was superimposed on the measured reactor temperature.

As depicted in Figure 16, the upper subplot illustrates that the reactor-temperature output remains almost unaffected, with the control signal maintaining smoothness and minimal oscillation, while the lower subplot shows the injected noise pattern. The negligible propagation of measurement noise to the control output confirms that the derivative-filter term

and the fractional-order derivative

effectively limit high-frequency amplification, enhancing the controller’s resilience to sensor disturbances.

Figure 16.

Noise attenuation performance of the mEAO-based FOPID controller.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

This study presented an mEAO-based FOPID controller for precise temperature regulation of a nonlinear CSTR system. The detailed reactor model, adopted from the standard benchmark formulation widely used in CSTR control studies, served as a reference for simulation, while the tuning process itself retained simulation-based tuning, relying solely on time-domain data to evaluate the performance index

. The fractional-order controller provided enhanced flexibility in gain and phase shaping, enabling improved stability margins and dynamic response compared with classical PID schemes.

Comparative simulations demonstrated that the proposed approach consistently outperformed EAO, SFOA, L-SHADE, and PSO in terms of convergence speed, cost-function minimization, and transient-performance indices such as rise time, settling time, and overshoot. In addition, comparisons with classical tuning strategies, including Rovira-based 2DOF-PID, Ziegler–Nichols PID, and Cohen–Coon PI controllers, verified the superior tracking accuracy and smoother control effort of the proposed method. Robustness analyses under varying set-points, feed-temperature disturbances, and measurement noise confirmed the ability of the controller to maintain stability under varying conditions without re-adjustment.

Overall, the mEAO provides an efficient balance between exploration and exploitation through adaptive enzyme-reaction parameters, allowing faster and more reliable convergence. When combined with the FOPID controller, it forms a flexible, accurate, and noise-tolerant control framework suitable for nonlinear chemical and thermal systems.

Future extensions may involve experimental implementation using a laboratory-scale CSTR to validate real-time feasibility, multi-objective formulations of mEAO to handle performance-energy trade-offs, as well as hybrid adaptive or learning-based schemes for online parameter tuning. Application of the proposed strategy to multi-reactor networks and thermally coupled processes is also foreseen to further enhance its industrial relevance.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.E.; Software, C.T., S.E. and G.Y.; Validation, C.T. and S.E.; Formal analysis, C.T. and D.L.; Writing — original draft, C.T.; Writing — review & editing, G.Y. and D.L.; Supervision, S.E.; Project administration, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) of the United Kingdom (Grant No. EP/T022701/1).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EAO | Enzyme Action Optimizer |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| FO | Fractional-Order |

| CSTR | Continuous stirred tank reactor |

| SFOA | Starfish Optimization Algorithm |

| L-SHADE | Success History-based Adaptive Differential Evolution with Linear population size reduction |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| MPC | Model Predicted Control |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| ZN | Ziegler–Nichols |

References

- Sinnott, R.; Towler, G. (Eds.) Chapter 4—Flow-Sheeting. In Chemical Engineering Design, 6th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 141–213. ISBN 978-0-08-102599-4. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Xie, Y.; Gui, W.; Yang, C. Weighted-Coupling CSTR Modeling and Model Predictive Control with Parameter Adaptive Correction for the Goethite Process. J. Process Control 2018, 68, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Mannan, M.S.; Wilhite, B.A. Towards Efficient and Inherently Safer Continuous Reactor Alternatives to Batch-Wise Processing of Fine Chemicals: CSTR Nonlinear Dynamics Analysis of Alkylpyridines N-Oxidation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 137, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alsten, J.G.; Jorgensen, M.L.; Ende, D.J.A. Hydrogenation of a Pharmaceutical Intermediate by a Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor System. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2009, 13, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Arya, S.K. Hydrogen from Algal Biomass: A Review of Production Process. Biotechnol. Rep. 2017, 15, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lu, T.; Yu, Z.; Song, W.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y. Experimental Investigation on the Promotion of CO2 Hydrate Formation for Cold Thermal Energy Storage—Effect of Gas-Inducing Stirring under Different Agitation Speeds. Green Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, M.; Nishimura, Y.; Takahashit, N. Periodic Operation of CSTR-II Practical Control. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1973, 28, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirizsek, P. Control 03 Stirred Tank Reactors in Open-Loop Unstable States; Pergamon Press Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1980; Volume 35. [Google Scholar]

- Kvasnica, M.; Herceg, M.; Čirka, Ľ.; Fikar, M. Model Predictive Control of a CSTR: A Hybrid Modeling Approach. Chem. Pap. 2010, 64, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekaf, J.; Havlena, V. Control of CSTR using model predictive controller based on mixture distribution. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2004, 37, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosanovich, K.A.; Piovoso, M.J.; Rokhlenko, V.; Guez, A. Nonlinear Adaptive Control with Parameter Estimation of a CSTR. J. Process Control 1995, 5, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abougarair, A.J.; Shashoa, N.A.A. Model Reference Adaptive Control for Temperature Regulation of Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Signal, Control and Communication, SCC 2021, Hammamet, Tunisia, 20–22 December 2021; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York City, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 276–281. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, A.; Mishra, R.K. Temperature Regulation in a Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor Using Event Triggered Sliding Mode Control. IFAC-Paper 2018, 51, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, S.; Ma, S.; Lu, Q.; Song, J.; Qing, X. Sliding Mode Control for Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor with Mismatched Disturbances: A Genetic-Algorithm-Optimized GESO Approach. In Proceedings of the Chinese Control Conference, CCC, Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2021; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 2354–2359. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, A.; Patil, B.V.; Nataraj, P.S.V.; Maciejowski, J.; Ling, K.V. Model Predictive Control of a CSTR: A Comparative Study among Linear and Nonlinear Model Approaches. Chem. Pap. 2010, 64, 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, D.; Li, D. Adaptive Fuzzy Fault-Tolerant Control for CSTR With State Constraints Dependent on Temperature and Concentration. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2025, 35, 2119–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakule, A.D.; Kerkar, P. Implementation of Temperature Regulation and Concentration Tracking of CSTR with Fuzzy. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS 2018), Madurai, India, 14–15 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 758–764. [Google Scholar]

- Putrus, K.M. Implementation of Neural Control for Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR). Al-Khwarizmi Eng. J. 2011, 7, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- MShahriari-kahkeshi, M.; Askari, J. Nonlinear Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR) Identification and Control Using Recurrent Neural Network Trained Shuffled Leaping Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Control, Instrumentation and Automation (ICCIA), Shiraz, Iran, 27–29 December 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikx, J. Application of Reinforcement Learning for Continuous Stirred Tank (CSTR) Temperature Control; UHasselt: Hasselt and Diepenbeek, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Peters, D.; Çıtmacı, B.; Alnajdi, A.; Morales-Guio, C.G.; Christofides, P.D. Machine Learning-Based Predictive Control of an Electrically-Heated Steam Methane Reforming Process. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbaky, M.A.; Emara, H.M.; El-Hawwary, M.I.; Bahgat, A.; Liu, X. Implementation of Fractional-Order PID Controller Using Industrial DCS with Experimental Validation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration: Connecting the Grids Towards a Low-Carbon High-Efficiency Energy System, EI2 2020, Wuhan, China, 20–23 October 2020; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York City, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 4407–4413. [Google Scholar]

- Benoît, N.; Motto, B.; Nkodo, L. Adaptive Temperature Control in Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2015, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. A Simplified Fractional Order Pid Controller’s Optimal Tuning: A Case Study on a Pmsm Speed Servo. Entropy 2021, 23, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankhwar, P. Excitation System, Proportional and Integral Controls of a Synchronous Generator for Reducing Adverse Impacts to Power System from Voltage Fluctuations. Int. J. Electr. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 11, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Wang, X.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, H.; Xin, Y. An Effective PID Control Method of Air Conditioning System for Electric Drive Workshop Based on IBK-IFNN Two-Stage Optimization. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobalan, S.; Prabhu, K.; Bhaskaran, V.M.; Scholar, P.G. Fuzzy Based Temperature Controller For Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2013, 2, 5835–5842. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Zhao, C.; Song, Y. CSTR Parameter Identification and PID Control Optimization Based on Improved Swarm Intelligence Algorithm. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 016001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, S.; Dewan, L. A Comparative Study of PID Based Temperature Control of CSTR Using Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, R. A PSO-Optimized Novel PID Neural Network Model for Temperature Control of Jacketed CSTR: Design, Simulation, and a Comparative Study. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 4759–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jin, G.G.; So, G.B. Adaptive Nonlinear Proportional–Integral–Derivative Control of a Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor Process Using a Radial Basis Function Neural Network. Algorithms 2025, 18, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashishtha, T.K.; Singh, V.P.; Yadav, U.K.; Sahu, U.K. Fractional-Order PID Controllers and Applications: A Comprehensive Survey. Annu. Rev. Control 2025, 60, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepljakov, A.; Alagoz, B.B.; Yeroglu, C.; Gonzalez, E.; HosseinNia, S.H.; Petlenkov, E. FOPID Controllers and Their Industrial Applications: A Survey of Recent Results. IFAC-Paper 2018, 51, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kar, M.K.; Goud, H. A Novel MGWO-Based FOPID Controller for CSTR System. IETE J. Res. 2025, 71, 1396–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, Z.S.; Mohamed, M.J. FOPID Neural Network Controller Design for Nonlinear CSTR System. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2023, 16, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanduja, N.; Bhushan, B. Optimal Design of FOPID Controller for the Control of CSTR by Using a Novel Hybrid Metaheuristic Algorithm. Sadhana 2021, 46, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bequette, W. Dynamics Process: Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Henson, M.A.; Seborg, D.E. Nonlinear Process Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, S.; Das, S.; Ghosh, R.; Goswami, B.; Balasubramanian, R.; Chandra, A.K.; Das, S.; Gupta, A. Design of a Fractional Order Phase Shaper for Iso-Damped Control of a PHWR under Step-Back Condition. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2010, 57, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirören, A.; Ekinci, S.; Hekimoğlu, B.; Izci, D. Opposition-Based Artificial Electric Field Algorithm and Its Application to FOPID Controller Design for Unstable Magnetic Ball Suspension System. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2021, 24, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepljakov, A.; Alagoz, B.B.; Yeroglu, C.; Gonzalez, E.A.; Hassan Hosseinnia, S.; Petlenkov, E.; Ates, A.; Cech, M. Towards Industrialization of FOPID Controllers: A Survey on Milestones of Fractional-Order Control and Pathways for Future Developments. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 21016–21042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Dehghan, S.; Chen, Y.Q.; Xue, D. A Review and Evaluation of Numerical Tools for Fractional Calculus and Fractional Order Controls. Int. J. Control 2017, 90, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, A.; Al-Tamimi, A.-K.; Al-Alnemer, L.; Mirjalili, S.; Tiňo, P. Enzyme Action Optimizer: A Novel Bio-Inspired Optimization Algorithm. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Yang, H.; Zhu, C. A Fractional Order Proportional-Integral-Derivative Controller for Series Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor System. Teh. Vjesn. 2021, 28, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaing, Z.L. A Particle Swarm Optimization Approach for Optimum Design of PID Controller in AVR System. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2004, 19, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tan, D.; Liu, L. Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm: An Overview. Soft Comput. 2018, 22, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekimoğlu, B. Optimal Tuning of Fractional Order PID Controller for DC Motor Speed Control via Chaotic Atom Search Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 38100–38114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, G.; Meng, Z.; Li, H.; Yildiz, A.R.; Mirjalili, S. Starfish Optimization Algorithm (SFOA): A Bio-Inspired Metaheuristic Algorithm for Global Optimization Compared with 100 Optimizers. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 3641–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A.S. Improving the search performance of SHADE using linear population size reduction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Beijing, China, 6–11 July 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014. ISBN 9781479914883. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro, V.M.; Vilanova, R.; Arrieta, O. Considerations on Set-Point Weight Choice for 2-DoF PID Controllers. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2009, 42, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovira, A.A.; Murrill, P.W.; Smith, C.L. Tuning Controllers for Set Point Changes; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, J.G.; Nichols, N.B. Optimum Settings for Automatic Controllers; American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME): New York, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Isdaryani, F.; Feriyonika, F.; Ferdiansyah, R. Comparison of Ziegler-Nichols and Cohen Coon Tuning Method for Magnetic Levitation Control System. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1450, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).