Abstract

The significant heterogeneity of continental shale reservoirs within the Permian Lucaogou Formation of the Jimsar Sag presents a major challenge for shale oil exploration. This study aims to quantitatively characterize the pore structure complexity of different lithofacies to identify favorable “sweet spots.” By integrating geochemical, petrological, and high-resolution pore characterization data with fractal theory, we introduce a comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) for evaluation. Five distinct lithofacies are identified: massive felsic siltstone (MFS), bedded dolostone (BD), bedded felsic dolostone (BFD), laminated dolomitic felsic shale (LDFS), and laminated mud felsic shale (LMFS). Pore structures vary significantly: MFS is dominated by mesopores (100–2000 nm), BD and BFD exhibit a bimodal distribution (<30 nm and >10 μm), while LDFS and LMFS are characterized by nanopores (<50 nm). Dc analysis reveals a descending order of pore structure complexity: BFD > LMFS > LDFS > MFS > BD. Furthermore, Dc shows positive correlations with clay mineral and feldspar contents but a negative correlation with carbonate minerals. A significant negative correlation between Dc and measured permeability confirms its effectiveness in characterizing reservoir heterogeneity. We propose that MFS and LDFS, with higher pore volumes and relatively lower Dc values, represent the most favorable targets due to their superior storage and seepage capacities. This study provides a theoretical foundation for the efficient development of continental shale oil reservoirs.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, the increasing global emphasis on clean and efficient utilization of unconventional energy resources has elevated shale oil to a prominent alternative, establishing it as a major worldwide research focus [1,2,3,4,5,6]. According to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA, 2022), the global technically recoverable resources of shale oil and gas are comparable to the undiscovered volumes of conventional oil and gas, highlighting the substantial exploration potential of shale hydrocarbons [7,8]. China possesses abundant shale oil resources, with estimated geological resources of approximately 33.54 billion metric tons and technically recoverable resources of about 4.393 billion metric tons, ranking behind only Russia and the United States and accounting for roughly 6% of the global total [7,8]. In contrast to the predominantly marine shale oils in North America, China’s shale oil resources are primarily located in large continental sedimentary basins, such as the Ordos, Songliao, and Junggar Basins [7,9,10]. Significant exploration breakthroughs have been achieved in various formations, including the Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin, the Qingshankou Formation in the Songliao Basin, the Paleogene strata in the Bohai Bay Basin, the Lucaogou Formation in the Junggar Basin, the Qianjiang Formation in the Jianghan Basin, the Jurassic strata in the Sichuan Basin, the Ganchaigou Formation in the Qaidam Basin, and the Paleogene strata in the Subei Basin [11,12,13]. These advances confirm shale oil as a practical and strategic alternative for increasing petroleum reserves and production in China.

Continental shale in China predominantly comprises fine-grained lacustrine deposits characterized by rapid facies changes, multisource sediment supply, and highly heterogeneous mineral compositions. These inherent depositional features give rise to diverse lithofacies types with frequent vertical variations, resulting in significant heterogeneity within the resultant reservoir spaces [10,14,15,16]. The heterogeneous pore system, which often incorporates various pore types and microfractures, forms complex network structures [17,18]. This complexity considerably increases the tortuosity of hydrocarbon flow pathways, thereby posing significant challenges for efficient resource extraction. Consequently, the quantitative characterization of storage space heterogeneity across different lithofacies is crucial for accurately evaluating continental shale reservoirs and identifying favorable “sweet spots.”

Fractal theory, pioneered by Mandelbrot, has proven to be a powerful tool for quantitatively characterizing the heterogeneity and complexity of pore systems in porous media such as shale [19]. This approach captures the self-similarity and structural irregularity of pore networks, offering critical insights into the mechanisms governing microscale heterogeneity [20]. Various methods have been employed to analyze the fractal characteristics of shale pores, including image analysis based on scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [21], the Frenkel–Halsey–Hill (FHH) model applied to nitrogen adsorption data [22,23], thermodynamic models [24], and techniques such as ultrasmall-angle X-ray scattering (USAXS) and small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) [25,26]. However, a significant knowledge gap remains, as most existing studies rely on single-method or single-parameter analyses focused on specific pore ranges [27,28]. Given that continental shale pore systems inherently span multiple scales from nanometers to micrometres, fractal analysis confined to a single scale fails to capture the overall heterogeneity of the storage space fully. Consequently, the multi-scale coupling mechanisms governing this heterogeneity and their systematic impact on fluid mobility in continental shale remain poorly understood, underscoring the need for integrated, full-scale fractal modeling and multi-factor interaction analysis.

The study area, comprising the Lucaogou Formation within the Jimsar Sag of the Junggar Basin, presents an ideal natural laboratory for addressing this research gap. This formation was deposited in a typical saline lacustrine environment influenced by multiple sediment sources, including terrigenous clastics, chemical precipitates, and volcanic ash, resulting in a complex mixosedimentite series [29,30]. Regionally, the Jimsar Sag forms part of the larger Junggar Basin, a significant hydrocarbon-bearing basin in northwestern China. The Lucaogou Formation shales are characterized by diverse mineralogy, well-developed laminated structures, and frequent vertical lithological variations, having undergone complex diagenetic alterations that further promoted the formation of distinct lithofacies [31,32,33]. Although previous studies have yielded valuable insights into the sedimentology and pore systems of the area [34,35], a comprehensive analysis integrating overall reservoir heterogeneity, the variations in multi-scale fractal characteristics of storage space among different lithofacies, and the underlying controlling mechanisms remains inadequate.

Therefore, to address this research gap, the present study concentrates on the continental shale reservoirs of the Lucaogou Formation in the Jimsar Sag. The primary objectives are as follows: (1) to systematically characterize the pore structure development across different lithofacies using a multi-method approach that integrates field emission scanning electron microscopy, low-temperature nitrogen adsorption, and high-pressure mercury intrusion; (2) to introduce and calculate a comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) that quantifies heterogeneity across multiple pore scales; (3) to quantitatively compare the multi-scale fractal characteristics of various lithofacies and elucidate their relationships with key geological factors and measured permeability; and (4) to establish a lithofacies-based evaluation framework that integrates storage capacity (pore volume) with flow capacity (pore complexity and permeability), thereby forming a robust criterion for assessing reservoir quality. This study is expected to provide a theoretical basis for the practical evaluation and efficient development of continental shale oil reservoirs.

2. Geological Setting

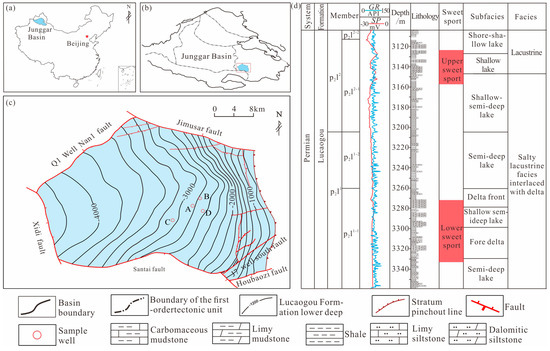

The Jimsar Sag is situated at the southwestern terminus of the eastern uplift zone within the Junggar Basin. This dustpan-shaped depression developed during the Early to Middle Permian, characterized by a fault-bounded western margin and an overlapping (or onlapping) eastern margin [31,36] (Figure 1a,b). The sag is delineated by thrust faults along its southern, western, and northern boundaries, which converge towards the sag center. The present-day structural configuration is relatively simple, forming a semi-annular monocline. Within the central part of the sag, strata dip at angles ranging from 3° to 5°, and faults are sparsely developed [30,34,37] (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area. (a) Geographic pattern of the Junggar Basin in NW China; (b) The tectonic unit of Junggar Basin and the location of Jimsar sag; (c) Structural isoline and well location distribution map of Permian Lucaogou Formation in Jimsar Sag; (d) Study on comprehensive stratigraphic histogram (Modified from. [29,30]). In the figure, A, B, C, and D refer to the four sampling wells.

The Lucaogou Formation, widely distributed across the Jimsar Sag, serves as the primary exploration target. It predominantly comprises fine-grained mixosediments deposited in a saline lacustrine environment [35]. The main lithologies include shale, mudstone, argillaceous siltstone, dolomite, dolomitic siltstone, and siltstone to fine-grained sandstone [38]. The formation exhibits a thickness ranging from 200 to 350 m, with a distribution area exceeding 800 km2 where the thickness surpasses 200 m. Generally, the formation thickens toward the southern and western parts of the sag and thins northward and eastward. [31,32]. Based on lithological and geophysical logging characteristics, the Lucaogou Formation is subdivided into the First Member (lower) and the Second Member (upper). Two shale oil “sweet spot” intervals have been identified within these members, both of which have yielded significant industrial oil flows [36].

Sedimentary facies are dominated by lacustrine deposits, with deltaic facies also present [39]. The lower sweet spot interval was deposited in a generally closed saline lake that experienced short-term open-water conditions, primarily consisting of delta-front subfacies and shore-shallow to semi-deep lacustrine mudstones. In contrast, the upper sweet spot interval formed in a persistently closed saline lake environment, mainly comprising shore-shallow lake to semi-deep lake subfacies deposits [39,40] (Figure 1d).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

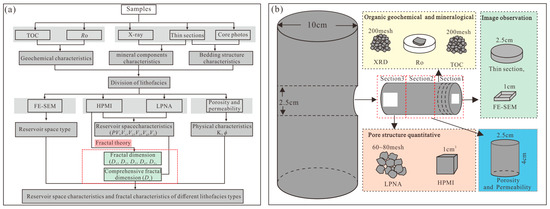

In this study, 15 columnar samples (diameter: 2.5 cm; length: 8–9 cm) were selected from four typical shale oil exploration wells (Well A: 5 samples; Well B: 2 samples; Well C: 4 samples; Well D: 4 samples) penetrating the Lucaogou Formation in the Jimsar Sag. The distribution of these wells is shown in Figure 1c. The selected samples represent the primary lithologies and bedding structures encountered in the study area. The overall experimental workflow is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Workflow for analyzing pore structure and fractal characteristics of continental shale reservoirs. (a) Experimental design flowchart (b) Sample preparation procedure and specifications. Parameters in red boxes in (a) represent calculated values.

Following retrieval, each core sample was subdivided into three segments according to the experimental scheme outlined in Figure 2b. The first segment (approximately 2 cm in length) was dedicated to the preparation of thin sections, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), and vitrinite reflectance (Ro) measurement. This segment was then crushed for total organic carbon (TOC) content determination and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The second segment (~4 cm long) was used for porosity and permeability measurements. The third segment (~2 cm long) was reserved for low-pressure nitrogen adsorption (LPNA) and high-pressure mercury intrusion porosimetry (HPMI) experiments.

3.2. Methods

TOC and Ro: The TOC content was determined using a LECO CS-230 carbon/sulfur analyzer (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, Michigan, USA). Sample preparation and analytical procedures strictly adhered to the Chinese standard GB/T 19145-2022 [41]. Prior to analysis, the samples were ground to a fine particle size of 200 mesh. To remove inorganic carbonate minerals, the powdered samples were treated with 5% dilute hydrochloric acid, followed by repeated washing with deionized water at 30 min intervals until neutralization was achieved. This process typically lasted three days, after which the samples were dried in an oven at 80 °C. Ro measurements were performed on a Zeiss Axioskop 40A Pol microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a 50× oil-immersion objective, operating under reflected light. All measurements were conducted in a controlled environment maintained at 23 °C and 40% relative humidity, in accordance with the standard SY/T 5124-2012 [42].

XRD and Thin-Section Analysis: XRD analysis was conducted using a Bruker D8 Advance instrument (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with Co Kα radiation operated at 45 kV. The scanning range was set from 5° to 50° (2θ) with a step size of 0.02°. For thin-section petrography, rock samples were ground to a standard thickness of 30 μm. To enhance the visibility of pores and micro-fractures, the thin sections were impregnated with blue epoxy (Fortuneibo-tech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) under vacuum. Additionally, alizarin red S staining was applied to differentiate carbonate minerals, specifically calcite, ferrocalcite, and ankerite. Mineral identification and textural characterization were performed using a Zeiss Axio Imager A2 POL polarized light microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Ober-kochen, Germany).

Prior to FE-SEM imaging, the samples were polished using argon broad ion beam (BIB) milling to achieve an artifact-free surface. A thin carbon coating (approximately 10 nm thick) was deposited to enhance surface conductivity. FE-SEM observations were performed with a Zeiss GeminiSEM 500 instrument (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany), which provides a resolution of 0.8 nm and an adjustable accelerating voltage from 0.02 to 30 kV. Mineral composition was further characterized by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

LPNA measurements were performed using a TriStar II 3020 surface area and porosity analyzer (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA) in accordance with the Chinese standard GB/T 21650.2-2008 [43]. Prior to analysis, the samples were crushed and sieved to obtain particles ranging from 60 to 80 mesh (0.18–0.25 mm). Subsequently, 0.5–1.0 g of each sample was subjected to vacuum degassing at 150 °C for 3 h. The degassed samples were then analyzed by measuring N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms at liquid nitrogen temperature across a relative pressure (P/P0) range of 0.010 to 0.998. The specific surface area (SSA) was calculated from the adsorption data using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, while the pore volume (PV) and pore size distribution (PSD) were derived from the adsorption branch using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) model [44].

HPMI analysis was conducted using an AutoPore IV 9510 mercury porosimeter (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA) with a maximum pressure of 413 MPa (60,000 psi), in accordance with the Chinese standard GB/T 21650.1-2008 [45]. Prior to the HPMI test, the shale sample was cut into a cubic piece measuring 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm, dried in an oven at 60 °C for 48 h, and subsequently cooled to room temperature (approximately 23 °C) in a desiccator. During the experiment, the external pressure was progressively increased from 0.034 MPa (5 psi) to 413 MPa (60,000 psi), enabling mercury to intrude into the pore spaces of the shale. The relationship between pore throat size and intrusion pressure was determined based on the Washburn equation [46].

The porosity and permeability of the cylindrical core plug (2.5 cm in diameter and 5 cm in length) were measured using a PoroPDP-200 overburden porosity and permeability tester (Core Laboratories, Houston, Texas, USA) in accordance with the Chinese standard GB/T 34533-2023 [47]. Helium was employed as the intrusion gas for porosity measurement, while nitrogen was used for the permeability determination via the pulse decay method. All experiments were conducted at a constant temperature of 23 °C. Prior to testing, the entire sample was scanned using an ATOS CORE 135 3D scanner (GOM, Brunswick, Lower Saxony, Germany). The acquired data were processed with GOM Inspect V8 software to calculate the total sample volume. The permeability measurement was performed under a confining pressure of 1500 psi and a pore pressure of 1000 psi.

Continental shale exhibits significant heterogeneity attributable to its complex mineral composition, pronounced vertical structural variations, and well-developed laminated structures. This heterogeneity leads to substantial variations in pore structure development among different shale formations. To minimize the influence of such heterogeneity on experimental results, horizontal core plug samples from consistent stratigraphic intervals were analyzed using the parallel experimental methods described previously (Figure 2).

3.3. Fractal Dimension Calculation

Fractal theory establishes a power-law relationship between the number of structural elements and the observation scale [48,49]. This relationship can be expressed for pore systems as follows: the number N of pores with a specific radius r is given by Equation (1):

Based on the capillary model, the fractal dimension derived from HPMI data can be expressed as follows in Equation (2) [50,51,52,53]:

where is the capillary pressure (MPa), is the minimum capillary pressure corresponding to the maximum pore throat size (MPa), is the mercury saturation (%) at capillary pressure, and D is the fractal dimension.

Taking the logarithm of both sides of Equation (2) yields:

Equation (3) indicates that if the pore size distribution in shale conforms to fractal theory, a linear relationship between log N (≥r) and log r will be observed in a double-logarithmic coordinate system. The slope (K) of this linear trend, obtained through regression analysis, is used to calculate the fractal dimension from high-pressure mercury intrusion data [50,51,54].

The fractal dimension of porous rocks typically ranges from 2 to 3. A value closer to 2 indicates a more homogeneous pore system with relatively smooth pore surfaces and simple structure, whereas a value approaching 3 reflects greater heterogeneity, characterized by increased pore structure complexity and surface roughness.

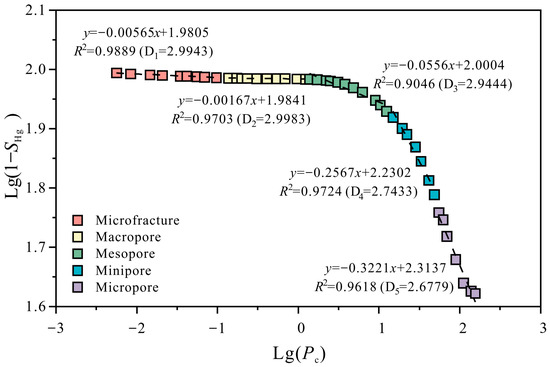

3.4. Comprehensive Fractal Dimension Calculation

Traditional fractal theory encounters a significant limitation when characterizing the full-scale pore structure of complex porous media such as shale: the pore system often exhibits distinct fractal characteristics across different scale ranges rather than conforming to a single fractal rule [53,54]. This phenomenon is particularly evident in the double-logarithmic plot of lg(1 − SHg) versus lg(Pc) derived from HPMI data, where multi-segment linear trends reflect varying fractal behaviors of the pore structure within specific pore size intervals (Figure 3). Consequently, a single fractal dimension fails to comprehensively capture the overall complexity of the multi-scale pore system in shale and can lead to suboptimal fitting results across the full-scale range for some samples. In evaluating shale reservoir heterogeneity, reliance on a single fractal parameter is insufficient to represent the overall structural characteristics of the reservoir space effectively. Although multiple independent parameters can be used for separate assessments, this approach tends to be cumbersome and lacks systematic integration. Therefore, introducing a parameter capable of comprehensively characterizing the global heterogeneity of the pore system is particularly necessary.

Figure 3.

Determination of multi-scale fractal dimensions for the reservoir pore system based on HPMI data, demonstrated for sample A2, MFS.

The comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) is a global index proposed to quantitatively characterize the overall complexity of multi-scale pore systems [55]. Its conceptual foundation lies in the weighted average principle, which integrates heterogeneity information from distinct pore size intervals into a single representative parameter. In this study, the weighting factor is defined as the proportion of pore volume within each scale interval relative to the total pore volume. This factor is used to compute a weighted average of the fractal dimensions corresponding to different intervals, thereby deriving a Dc value that reflects the overall complexity of the reservoir space. The specific calculation procedure can be summarized as follows:

(1) Based on established classification schemes for shale oil reservoir pore structure, the multi-scale pore system was divided into four distinct intervals: micropores (<25 nm), small pores (25–100 nm), mesopores (100 nm–1 μm), and macropores (1–10 μm) [38,56].

(2) The pore volume ratio for each interval (Vi), defined as the proportion of the pore volume within a specific interval to the total pore volume, was calculated using the incremental pore volume data derived from HPMI experiments.

(3) The segmented linear segments evident in the double-logarithmic plot of lg(1 − SHg) versus lg(Pc) from the HPMI data were subjected to linear regression using the least squares method. The fractal dimension (Di) for each pore-size interval was subsequently calculated based on Equation (4) (Figure 3). A goodness-of-fit threshold (R2 > 0.85) was established; only intervals where the data points yielded an R2 value exceeding this threshold were considered to possess significant fractal characteristics, and their corresponding Di values were retained for further analysis. Intervals with R2 values below 0.85, indicating a lack of robust fractal behavior, were excluded from the subsequent calculation.

(4) The Dc was ultimately determined by computing the weighted average of the validated Di values, using Vi as the weighting factor, as formulated in Equation (5).

where Dc is the comprehensive fractal dimension; Di is the fractal dimension of different pore scales (micropores, small pores, mesopores, macropores, microfractures); Vi is the percentage of pore volume of each scale relative to the total pore volume (%).

4. Results

4.1. Geochemical Parameters

The key organic geochemical parameters evaluated in this study are summarized in Table 1. Organic matter abundance is a fundamental parameter for assessing source rock quality and forms the basis for evaluating hydrocarbon generation potential. Primary evaluation indicators include TOC content, hydrocarbon generation potential (S1 + S2), chloroform bitumen “A” content, and total hydrocarbon content. Among these, TOC is the most representative measure of organic matter abundance and is readily measurable. Experimental data from this study indicate that the TOC values of source rocks in the Lucaogou Formation within the Jimsar Sag range from 0.76% to 8.33%, with an average of 2.69%. The Lucaogou Formation was deposited in a saline to brackish lacustrine environment [33]. Based on the established evaluation standards for lacustrine source rocks in China, over 88% of the analyzed samples exhibit TOC values exceeding 1.0%, indicating that the majority of the Lucaogou Formation source rocks are classified as “good” to “excellent”. Thermal maturity is another crucial indicator for source rock assessment. The measured Ro values for the Lucaogou shale predominantly range from 0.45% to 0.94%, averaging 0.75%. These values suggest that the source rocks are generally within the low to mature stage.

Table 1.

Measured geochemical, mineralogical, and petrophysical parameters of shale samples from the Lucaogou Formation, Jimsar Sag.

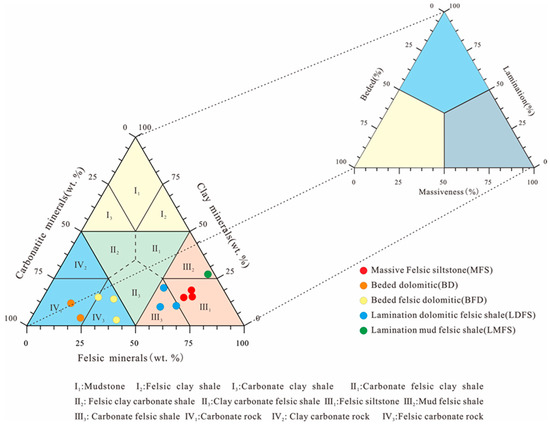

4.2. Characteristics of Mineral Composition and Classification of Lithofacies

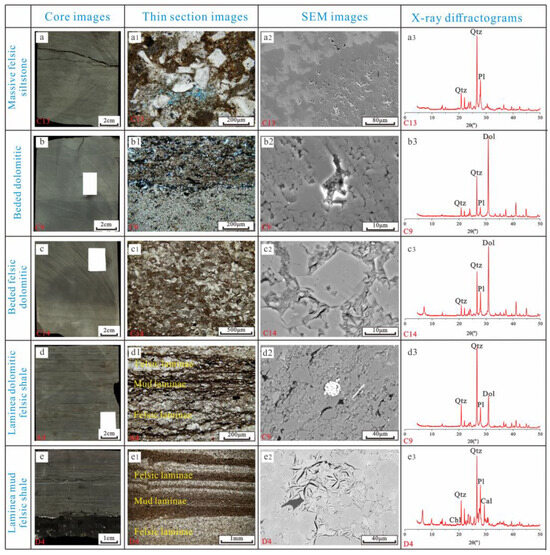

Shale lithofacies are defined by the integrated characteristics of organic matter abundance, sedimentary structures, grain size, and mineral composition, which collectively reflect specific depositional environments [57]. XRD analysis reveals that the Lucaogou Formation in the Jimsar Sag is predominantly composed of quartz, plagioclase, and dolomite. Quantitative analysis indicates average contents of 22.8% quartz, 23.4% feldspar (primarily plagioclase), and 30.5% dolomite. In contrast, clay mineral content is comparatively low, averaging 11.4% (Table 1). By integrating data from drill core observations, thin-section analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images, mineral grain size, laminar characteristics, and mineral ternary diagrams (Figure 4), the lithofacies of the Lucaogou Formation were systematically identified and classified. The predominant lithofacies types include massive felsic siltstone (MFS), bedded dolomite (BD), bedded felsic dolomite (BFD), laminated dolomitic felsic shale (LDFS), and laminated mud felsic shale (LMFS).

Figure 4.

Lithofacies type division chart of Lucaogou Formation in Jimsar Sag.

MFS displays a dark gray color and exhibits a thick, massive structure characterized by uniform texture and absence of distinct bedding. It contains over 70% quartz and feldspar minerals, with coarse-grained terrigenous clastic particles indicating a proximal transport-deposition system (Figure 5a–a3). BD shows light gray hues and a homogeneous micritic/microcrystalline dolomite composition, containing more than 70% dolomite with fine-grained textures (Figure 5b–b3). BFD is dark gray with millimeter-scale layering (1–10 mm thickness), primarily consisting of sparry dolomite (56.4% average carbonate content) and subordinate felsic minerals (29.1%) (Figure 5c–c3). LDFS exhibits alternating light and dark laminae under 1 mm thick, containing approximately 26.8% feldspar, 29.8% quartz, and 30.0% carbonate. Coarse felsic mineral layers are intercalated with fine-grained mixed matrix components (Figure 5d–d3). LMFS displays well-developed lamellar structures dominated by felsic minerals, with high clay content (>25%) and 4.3% pyrite, featuring uniformly fine mineral particles (Figure 5e–e3).

Figure 5.

Characteristics of different lithofacies types of Lucaogou Formation in Jimsar Sag: (a–a3) C13, MFS; (b–b3) C9, BD; (c–c3) C14, BFD; (d–d3) A4, LDFS; (e–e3) D4, LMFS. Qtz: quartz; Pl: plagioclase; Cal: calcite; Dol: dolomite.

4.3. Pore Types of Shale Reservoirs

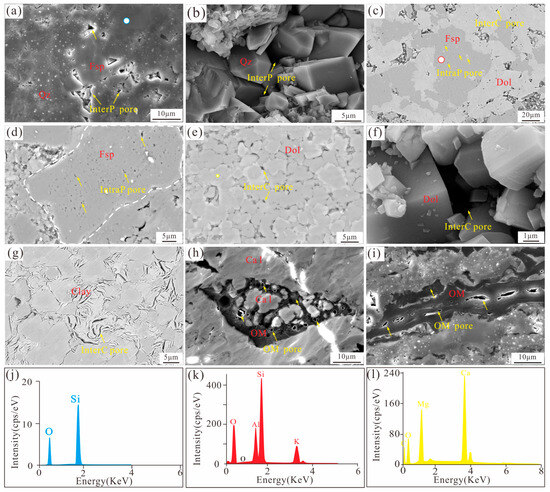

The shale oil reservoirs of the Lucaogou Formation in the Jimsar Sag exhibit multiscale pore systems ranging from nanometers to micrometers. According to Loucks’ classification scheme [57], the reservoir spaces are categorised into three types: inorganic mineral pores, organic matter pores, and microfractures. The pores of inorganic minerals include intergranular pores, intragranular pores, and intercrystalline pores. Organic pores include kerogen-related pores and solid asphalt-related pores. Microfractures include three types: tectonic microfractures (TMFs), shrinkage microfractures (SMFs), and bedding-parallel microfractures (BPMFs).

4.3.1. Inorganic Mineral Pores

Intergranular pores represent a fundamental type of reservoir space within the Lucaogou Formation, predominantly occurring between brittle mineral grains such as quartz and feldspar (Figure 6a,b,l). Their diameters typically range from 50 nm to 2 μm. In specific lithofacies, dissolution processes significantly enlarge these pores, resulting in diameters spanning from 100 nm to 10 μm. Intragranular pores are chiefly developed within minerals, including feldspar, calcite, and dolomite (Figure 6c,d). Feldspar exhibits the highest density of intragranular pores, characterized by dissolution pores aligned in a beaded pattern along cleavage planes (Figure 6d,j). These pores are generally small (5–400 nm), predominantly isolated, and exhibit poor connectivity. Intercrystalline pores are mainly observed between mineral particles, such as those in clay and dolomite. Dolomite intercrystalline pores, found between dolomite crystal clusters (Figure 6e,f,k), typically have diameters of 10–200 nm. Clay mineral intercrystalline pores often display crescent, arc, wedge, or irregular polygonal shapes and tend to occur in interconnected or semi-connected clusters (Figure 6g).

Figure 6.

This figure illustrates the diverse microscopic pore systems developed in the Lucaogou Formation shale within the Jimsar Sag. (a) Well C, 3541.71 m, MFS, intergranular pore; (b) Well D, 3179.11 m, LDFS, intergranular pore; (c) Well B, 3389.84 m, MFS, intragranular pore; (d) Well A, 3300.72 m, LMFS, intragranular pore; (e) Well A, 3325.67 m, BD, dolomite intercrystalline pores; (f) Well A, 3318.69 m, BFD, dolomite intercrystalline pores; (g) Well D, 3295.36 m, LMFS, clay mineral intercrystalline pores; (h) Well C, 3461.35 m, LDFS, OM pore; (i) Well C, 3541.71 m, MFS, OM pore; (j) The energy spectrum corresponding to the blue point in (a); (k) The energy spectrum image corresponding to the red point in (c); (l) The energy spectrum corresponding to the yellow point in (e).

4.3.2. Organic Matter Pores

Organic matter (OM) pores are defined as nanoscale pore systems within organic particles or residual voids formed during hydrocarbon generation and expulsion. Their development, distribution, and size are primarily controlled by the abundance, type, and thermal maturity of the organic matter present in the shale. In contrast to typical marine shales, continental shale reservoirs generally exhibit less developed and more heterogeneous OM porosity, with significant variations in pore development among different organic macerals and their occurrences. These pores are predominantly elliptical or irregular in shape (Figure 6h,i). In certain organic matter particles, high thermal maturity has resulted in the development of honeycomb-like pore clusters (Figure 6h), with pore sizes ranging widely from approximately 5 nm to 1200 nm.

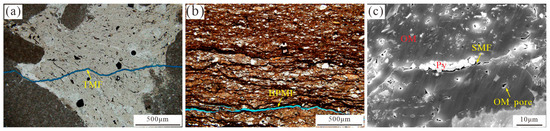

4.3.3. Microfractures

Microfractures within the shale oil reservoir of the Lucaogou Formation in the Jimsar Sag can be genetically and morphologically categorized into three principal types: TMF, BPMF, and SMF. TMF predominantly develops in lithofacies enriched with brittle minerals such as quartz and dolomite. These fractures typically exhibit straight trajectories and possess relatively larger apertures. Observations indicate that their lengths range from 0.1 mm to 4 mm, with apertures varying between 0.3 μm and 20 μm (Figure 7a). BPMF is commonly associated with laminated shales. Their genesis is closely linked to interfacial separation resulting from compositional contrasts between adjacent laminae and overpressure generated during hydrocarbon generation [58]. Given the well-developed lamination characteristic of the Lucaogou Formation, BPMF is extensively distributed within these laminated intervals. These fractures generally align parallel to the bedding planes. Statistical analysis from thin sections reveals that their apertures are predominantly less than 10 μm, while their lengths frequently exceed 4 mm (Figure 7b). Overall, these fractures exhibit low degrees of filling and thus maintain good effectiveness. SMF primarily initiates within clay minerals, likely triggered by dehydration shrinkage and mineral transformation during early diagenesis. Microscopic examination shows that these fractures often display curved morphologies, with lengths typically under 20 μm and exhibiting variable orientations and dip angles. Their apertures generally range from 0.01 μm to 2 μm (Figure 7c).

Figure 7.

Characteristics of microfracture development in the Lucaogou Formation of the Jimsar Sag. (a) Well A, 3325.62 m, BD, TMF; (b) Well C, 3591.86 m, BFD, BPMF; (c) Well C, 3461.35 m, LDFS, SMF. TMF: tectonic microfractures; BPMF: bedding-parallel microfractures; SMF: shrinkage microfractures.

4.4. Pore Size Distribution Characteristics

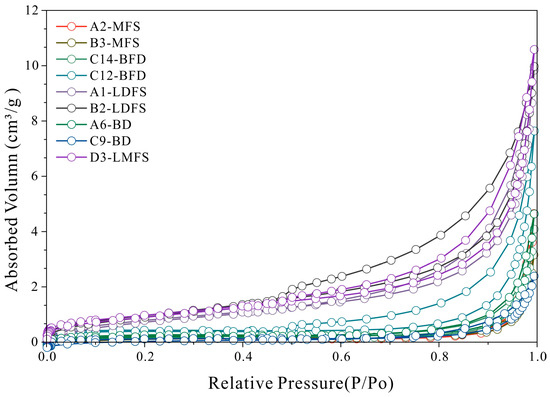

In this study, LPNA and HPMI techniques were utilized to characterize the pore systems within the shale reservoirs of the Lucaogou Formation in the Jimsar Sag. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms are widely applied to investigate pore structure characteristics in nanoporous media [59,60]. Samples representing different lithofacies of the Lucaogou Formation exhibit Type II adsorption isotherms (Figure 8). The hysteresis loops observed in these isotherms display relatively flat profiles. Classified as composite H3–H4 types under the IUPAC system, these loops indicate the prevalence of slit-shaped pores with parallel plates and wedge-shaped pore structures in the Lucaogou Formation reservoirs [60,61].

Figure 8.

LPNA adsorption–desorption curve of Lucaogou Formation shale in Jimsar sag. For detailed data, please refer to the Supplementary Materials.

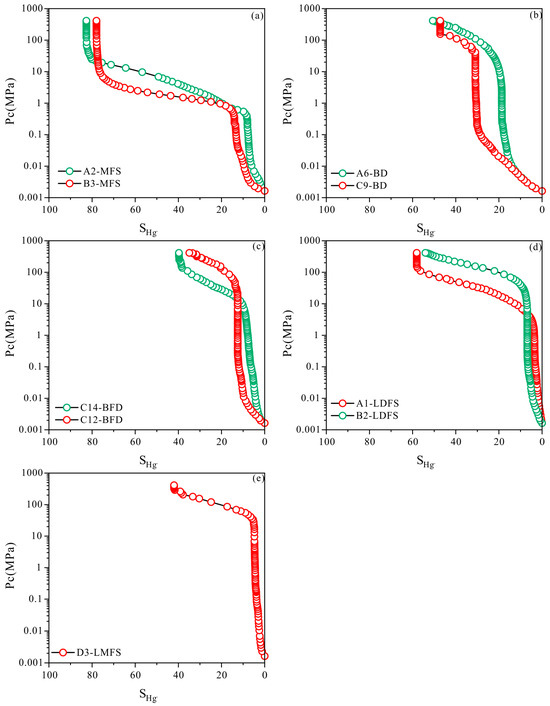

Based on the distribution characteristics of mercury saturation, the capillary pressure curves can be classified into three distinct types. For the MFS lithofacies, the mercury intrusion curve exhibits a gradual increase in mercury volume during the initial low-pressure stage (<0.6 MPa). A pronounced platform appears abruptly at approximately 0.6 MPa, beyond which the mercury volume stabilizes as the pressure increases to 25 MPa, indicating a predominantly concentrated pore-size distribution within this lithofacies (Figure 9a). In contrast, the mercury saturation curves for BFD and BD increase slowly during the initial low-pressure stage. When the pressure reaches approximately 0.1 MPa, the mercury saturation remains largely constant. As the pressure further increases to 100 MPa, the mercury saturation begins to rise slowly in response to the elevated pressure. This pattern reflects the presence of two distinct pore-size distribution intervals with significant differences in pore throat radii within the carbonate-rich lithofacies (Figure 9b–c). For the LDFS and LMFS, the mercury saturation remains essentially unchanged during the initial stage of mercury intrusion. When the inlet pressure exceeds 25 MPa, the mercury saturation increases rapidly. This curve type suggests that the pore-size distribution in LDFS and LMFS is relatively concentrated (Figure 9d,e).

Figure 9.

Distribution map of mercury saturation curves for different lithofacies types of Lucaogou Formation shale in Jimsar sag. (a) MFS; (b) BD; (c) BFD; (d) LDFS; (e) LMFS.

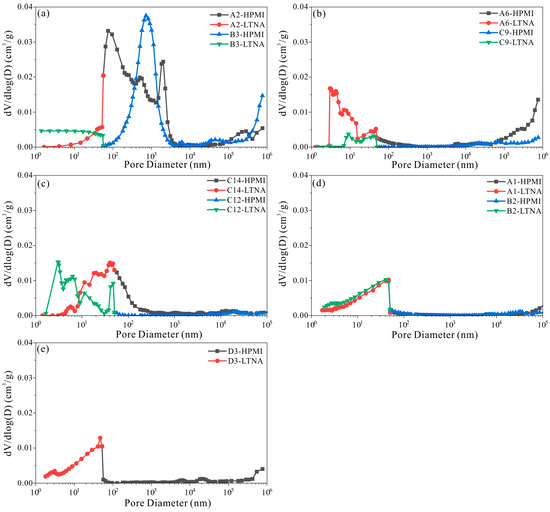

Integrated analysis utilizing LPNA and HPMI techniques, combined with full-scale pore size characterization, reveals that the PV of the Lucaogou Formation shale reservoir ranges from 0.0036 to 0.0421 cm3/g, with an average of 0.0216 cm3/g. The full-aperture pore size distribution demonstrates that the reservoir space is primarily contributed by three distinct pore size ranges: micropores (<30 nm), mesopores to macropores (100–1000 nm), and macropores to microfractures (>10 μm). Notably, pore volumes exceeding 10 μm are predominantly associated with microfractures. Detailed lithofacies analysis indicates that the MFS exhibits a pore volume ranging from 0.0275 to 0.4207 cm3/g (average 0.0348 cm3/g), displaying a distinct, dominant unimodal pore size distribution concentrated within the 100–2000 nm range (Figure 10a). The BFD and BD exhibit measured pore volumes of 0.0108–0.0170 cm3/g (mean 0.0139 cm3/g) and 0.0036–0.0176 cm3/g (mean 0.0106 cm3/g), respectively. Both lithofacies are characterized by a bimodal pore size distribution pattern, dominated by pores <30 nm and >10 μm (Figure 10b,c). The LDFS and LMFS show pore volumes of 0.0085–0.0184 cm3/g (mean 0.0134 cm3/g) and 0.0019–0.0211 cm3/g (mean 0.0210 cm3/g), respectively. These lithological units possess pore systems predominantly composed of nanoscale pores <50 nm (Figure 10d,e).

Figure 10.

Full-scale pore size distribution curves of the Lucaogou Formation in Jimsar Sag: (a) MFS; (b) BD; (c) BFD; (d) LDFS; (e) LMFS.

4.5. Fractal Dimension Characteristics

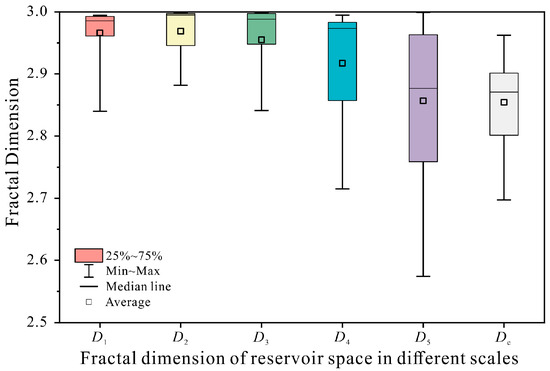

Analysis of the fractal dimensions across different pore scales in the Lucaogou Formation revealed significant variations (Table 2). The fractal dimension of micropores (D5) ranged from 2.5742 to 2.9991 (average: 2.8401); minipores (D4) from 2.7151 to 2.9948 (average: 2.9182); mesopores (D3) from 2.8412 to 2.9991 (average: 2.9615); macropores (D2) from 2.9459 to 2.9995 (average: 2.9792); and microfactures (D1) from 2.9309 to 2.9944 (average: 2.9662). The fractal dimensions of micropores and minipores exhibited broader distributions, whereas macropores and microfactures showed narrower, more concentrated values. Overall, the mean fractal dimensions decreased in the order: D2 (macropores) > D1 (microfractures) > D3 (mesopores) > D4 (minipores) > D5 (micropores), indicating that macropores possess the most complex spatial distribution and highest heterogeneity, while micropores are relatively more homogeneous. The comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) ranged from 2.7488 to 2.9623 (average: 2.8539), reflecting substantial overall heterogeneity in the storage space of the Lucaogou Formation shale (Figure 11).

Table 2.

Fractal parameters of multi-scale pore systems in the Lucaogou Formation shale reservoirs, Jimsar Sag.

Figure 11.

Box plot showing the distribution of fractal dimensions in reservoir space across different scales. D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5 represent the fractal dimensions of micro-fractures, macro-pores, meso-pores, micro-pores, and micropores, respectively; Dc indicates the comprehensive fractal dimension.

5. Discussion

5.1. Control of Lithofacies on Reservoir Space System and Heterogeneity

The pore structure and heterogeneity variations among different lithofacies in the Lucaogou Formation are fundamentally controlled by the interplay between initial sedimentary mineral assemblages and subsequent diagenetic evolution. This study demonstrates that the observed differences in reservoir space and heterogeneity are primarily attributable to lithofacies-specific diagenetic responses, a characteristic that distinguishes the Lucaogou Formation from typical marine shale systems.

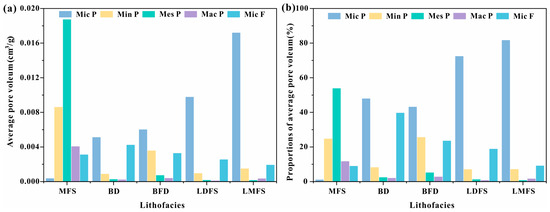

The pore volume in the MFS is predominantly contributed by mesopores (100–1000 nm), which account for 53.76% of the total pore volume; macropores and microfractures also represent significant proportions (Figure 12). The Dc of MFS averages 2.8662, indicating a relatively low overall complexity of the reservoir space compared to other lithofacies. In contrast to clay-rich shales, where intense compaction substantially reduces porosity, the high content of quartz and feldspar in MFS plays a critical role in preserving and enhancing porosity. Although strong compaction in the Lucaogou Formation of the Jimsar Sag is identified as a major factor causing damage to reservoir space [62], the coarse-grained terrigenous quartz in MFS provides a rigid framework that effectively resists compaction-induced pore destruction [14,63]. The preservation of these primary intergranular pores facilitated the migration of diagenetic fluids, which in turn led to multi-stage dissolution of soluble minerals such as feldspar under alternating acidic and alkaline diagenetic conditions, consequently generating substantial secondary porosity along cleavage planes [64]. Consequently, the pore system in MFS consists of well-preserved interparticle pores and dissolution-enhanced secondary pores, exhibiting moderate complexity overall. This genetic mechanism fundamentally differs from that of marine shales, where pore development depends more prominently on hydrocarbon generation from organic matter and dissolution along bedding planes [65,66].

Figure 12.

Pore volume distribution characteristics of different lithofacies in the Lucaogou Formation, Jimsar Sag. (a) Absolute pore volume distribution across distinct pore-size ranges. (b) Relative percentage distribution of each pore-size range normalized to the total pore volume. Abbreviations: Mic P, micropores (<25 nm); Min P, minipores (25–100 nm); Mes P, mesopores (100–1000 nm); Mac P, macropores (1–10 μm); Microfractures (>10 μm).

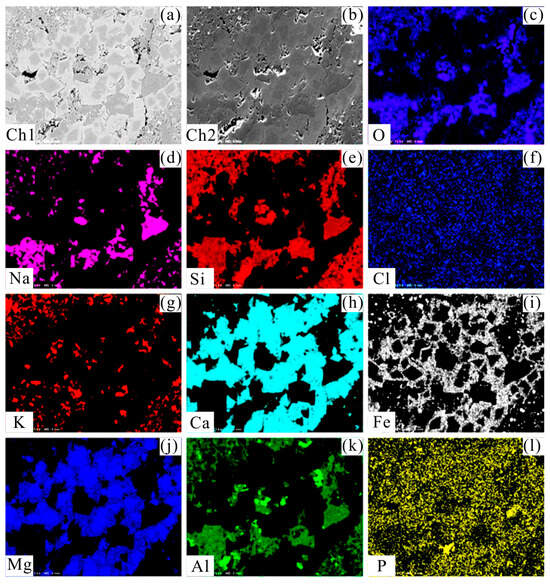

The formation and evolution of reservoir spaces in both the BD and BFD are controlled by diagenetic processes; however, they exhibit significant differences in mineral composition and pore structure. The reservoir space of BD is dominated by micropores (47.86%) and microfractures (39.62%) (Figure 12), with an average comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) of 2.8108, indicating a relatively homogeneous reservoir with low heterogeneity. This characteristic primarily stems from the well-developed microcrystalline dolomite texture in BD, which contains uniformly distributed intercrystalline pores. In contrast, BFD exhibits higher structural complexity, with an average Dc of 2.9048. Its pore-size distribution is dominated by micropores (43.08%) and small pores (25.55%), with microfractures accounting for 23.49% (Figure 13). The higher content of brittle minerals in BFD not only effectively resists compaction-induced pore destruction during diagenesis, preserving dolomite intercrystalline pores, but also enhances reservoir quality through the presence of residual interparticle pores between quartz and feldspar grains. However, this multi-type pore system results in more tortuous fluid flow paths compared to the pure dolomite facies, leading to a higher Dc value. Ankeritization is widespread within the Lucaogou Formation. SEM images reveal that dolomite commonly exhibits distinct “bright rim” structures, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis confirms higher iron (Fe) content in these rims (Figure 13). The formation of ankerite enhances rock brittleness and improves the compressive resistance of the crystal framework, thereby effectively inhibiting pore collapse caused by compaction and favoring the preservation of intercrystalline pores [67,68]. Simultaneously, the increased brittleness of the dolomite promotes the development of microfractures, collectively optimizing the reservoir space [58].

Figure 13.

Different element surface distribution observed under scanning electron microscope in Lucaogou Formation of Jimsar Sag, A6, BD. (a) Backscattered electron (BSE) image; (b) Secondary electron (SE) image; (c–l) Elemental distribution maps for oxygen (O), Sodium (Na), Silicon (Si), chlorine (Cl), Kalium (K), Calcium (Ca), Ferrum (Fe), Magnesium (Mg), Aluminum (Al), and Phosphorus (P).

Both the LDFS and LMFS exhibit typical binary laminated structures characterized by alternating argillaceous and felsic laminae. However, influenced by differences in lamina architecture and diagenetic evolution, they display significant distinctions in reservoir space characteristics and heterogeneity. LDFS possesses a high TOC content, averaging 2.5%. During diagenesis, organic acids generated from the thermal maturation of organic matter within the argillaceous laminae migrate along microfractures to adjacent felsic laminae, dissolving feldspar grains and forming secondary dissolution pores [17,58,69]. Concurrently, secondary clay minerals formed by feldspar dissolution cement primary interparticle pores, thereby damaging the primary porosity. Under the combined effects of dissolution and cementation, LDFS ultimately developed a pore system predominantly composed of micropores (72.34%) (Figure 12). Its comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) averages 2.8535, indicating moderate overall heterogeneity. In comparison, LMFS contains a higher proportion of micropores (81.59%) (Figure 12) and exhibits more substantial heterogeneity, with an average Dc of 2.8818. This is primarily attributed to the lower TOC content, higher clay mineral content, finer-grained felsic minerals, and thinner laminae in LMFS. These characteristics result in weaker organic acid dissolution during diagenesis, extensive cementation of primary interparticle pores by clay minerals, and poor development of secondary pores. Therefore, within the laminated shales of the Lucaogou Formation, acid dissolution driven by higher TOC content is the key diagenetic factor contributing to the superior reservoir quality of LDFS compared to LMFS.

5.2. Factors Influencing the Comprehensive Fractal Dimension

5.2.1. TOC and Ro

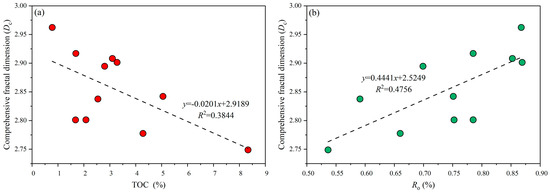

This study investigated the correlation between the Dc and both the TOC content and Ro in the shale reservoirs of the Lucaogou Formation within the Jimsar Sag. The results reveal a significant negative correlation between Dc and TOC (Figure 14a), indicating a decrease in pore structure complexity with increasing organic matter abundance. This finding contrasts with observations in high- to over-mature marine shales, where well-developed organic matter pores typically enhance reservoir space complexity [69,70,71]. The distinct behavior in the Lucaogou Formation may be attributed to the specific mechanisms by which organic matter influences continental shale reservoirs. In the study area, the overall high TOC content, combined with the fact that the organic matter is in the oil-generation window, generally results in poorly developed organic pores. Furthermore, the organic matter and the bitumen generated during its thermal evolution can infill and clog primary inorganic pores, thereby reducing the overall complexity and heterogeneity of the pore system. Conversely, Dc exhibits a significant positive correlation with Ro (Figure 14b), suggesting that the complexity and heterogeneity of the pore structure increase with thermal maturity. This enhancement is likely driven by hydrocarbon generation from organic matter and associated diagenetic processes, such as the development of secondary dissolution pores and microfractures.

Figure 14.

Correlations between organic geochemical parameters and the comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) in the shale reservoirs of the Lucaogou Formation, Jimsar Sag. (a) TOC; (b) Ro.

5.2.2. Minerals

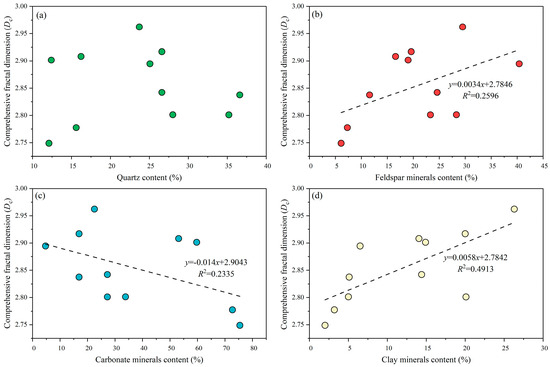

The relationship between the Dc and the mineral composition of the Lucaogou Formation shales was analyzed to elucidate the controlling effects of different minerals on reservoir space development and heterogeneity. Dc shows no significant correlation with quartz content (Figure 15a), suggesting that although quartz provides a crucial rigid framework for pore preservation, its intrinsic contribution to pore complexity is limited and plays a comparatively minor role in this reservoir system. In contrast, Dc exhibits a positive correlation with feldspar content (Figure 15b), reflecting the fact that feldspar, as a readily dissolvable mineral, generates secondary pores through organic acid dissolution, thereby significantly enhancing pore system complexity and heterogeneity. This observation aligns with findings reported in other siliciclastic and mixed shale reservoirs [72,73]. Dc is negatively correlated with carbonate mineral content (Figure 15c), primarily due to the relatively simple and uniform structure of the intercrystalline pore systems associated with micritic to cryptocrystalline dolomite and calcite. The most pronounced positive correlation exists between Dc and clay mineral content (Figure 15d). The underlying mechanism is that clay minerals not only contribute abundant nanoscale intercrystalline pores but are also commonly associated with intense laminated structures and heterogeneous depositional backgrounds. The combination of multiple micropore types significantly increases pore morphological complexity, resulting in higher Dc values. In summary, mineral composition collectively governs the complexity of the reservoir pore structure through direct participation in diagenetic reactions and indirect influences on pore morphology. Among the major mineral components, clay minerals and feldspar significantly enhance pore heterogeneity, whereas carbonate minerals tend to simplify the pore structure.

Figure 15.

Correlations between mineral composition and the comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) in the shale reservoir of the Lucaogou Formation, Jimsar Sag. (a) Quartz content; (b) Feldspar content; (c) Carbonate mineral content; (d) Clay mineral content.

5.3. Heterogeneity of Pore Systems in Different Lithofacies and Its Impact on Hydrocarbon Accumulation

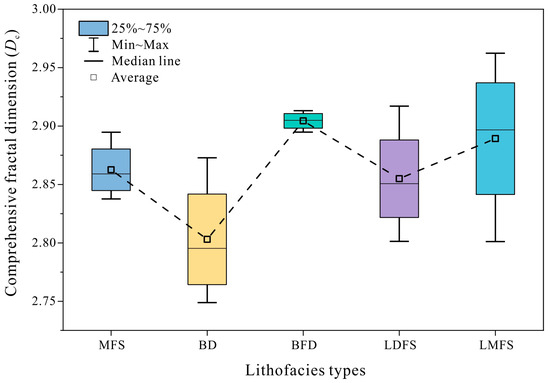

The Dc effectively overcomes the limitations of conventional single-scale fractal analysis by integrating the heterogeneity inherent to multi-scale pore systems. Using the pore volume proportion (Vi) of distinct pore-size intervals as weighting factors ensures that intervals contributing more significantly to the total pore volume exert a greater influence on the Dc value, thereby providing a more rational representation of the overall pore system complexity. Based on the Dc analysis, the heterogeneity of the reservoir space among different lithofacies in the Lucaogou Formation of the Jimsar Sag can be ranked in descending order as follows: BFD > LMFS > LDFS >MFS >BD. This sequence quantitatively characterizes the pore structure complexity of each lithofacy (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Box plot illustrating the distribution of comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) values across different lithofacies in the Lucaogou Formation, Jimsar Sag.

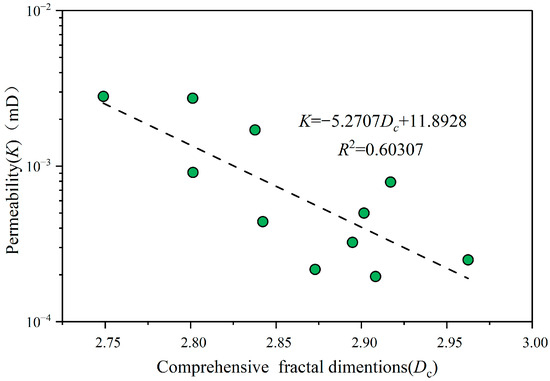

A significant negative correlation is observed between the Dc and permeability (Figure 17), indicating that rock permeability decreases exponentially with increasing overall complexity and heterogeneity of the pore structure. This relationship elucidates the control mechanism of pore system fractal characteristics on fluid flow: a high Dc value typically corresponds to a complex pore network dominated by nanoscale micropores with high tortuosity, resulting in elevated flow resistance and consequently extremely low permeability. This finding demonstrates that Dc can serve as an effective indicator for quantitatively evaluating reservoir flow capacity, underscoring its significant geological relevance.

Figure 17.

Correlation between measured permeability (K) and the comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) of shale reservoirs in the Lucaogou Formation, Jimsar Sag.

Based on a comprehensive evaluation of storage capacity and pore space complexity across different lithofacies in the Lucaogou Formation, the MFS and LDFS are identified as favorable lithofacies for shale oil exploration in the Jimsar Sag. The MFS lithofacies exhibits a substantial pore volume and a relatively homogeneous pore system dominated by mesopores, which facilitates efficient fluid flow. Although the LDFS lithofacies displays higher structural complexity, its moderate Dc values, combined with well-developed laminae and high organic matter content, indicate favorable storage potential. In contrast, the BFD and LMFS possess certain storage space but exhibit complex pore networks and significant heterogeneity, potentially restricting oil mobility and challenging shale oil production. The BD features a simple pore structure but limited storage capacity. The lithofacies ranking framework established in this study, integrating storage capacity (pore volume) with flow capacity (pore complexity and permeability), provides a scientific basis for predicting shale oil “sweet spots” in the Lucaogou Formation.

Finally, while this study establishes the comprehensive fractal dimension (Dc) as an effective quantitative indicator for statistically characterizing pore structure complexity in continental shale reservoirs, several limitations should be acknowledged. (1) The samples were primarily collected from a limited number of key wells within the Jimsar Sag. Although the major lithofacies are represented, the spatial distribution and vertical stratigraphic coverage remain constrained. Consequently, extrapolating these findings to the entire basin or analogous basins requires caution. (2) This research focuses on the static characterization of pore structures and does not address the dynamic evolution of pore systems during hydrocarbon generation and migration.

6. Conclusions

(1) The significant heterogeneity observed in the shale reservoirs of the Lucaogou Formation fundamentally reflects a multi-scale pore system governed by the combined effects of mineral composition and sedimentary architecture. Despite a high TOC background (averaging 2.69%) and relatively low thermal maturity, the reservoir space is predominantly composed of inorganic pores, including interparticle, intraparticle dissolution, and intercrystalline pores, while organic matter-hosted pores are underdeveloped. At the microscopic scale, pores ranging from micrometers to nanometers interconnect with microfractures, collectively forming an intricate pore-fracture network.

(2) The complexity of the pore structure is collectively controlled by thermal maturity, soluble mineral content, and the extent of laminated structure development. Heterogeneity varies significantly across different lithofacies, with BFD exhibiting the highest degree of heterogeneity, whereas BD is the most homogeneous.

(3) Analysis reveals a significant negative correlation between the Dc and permeability in the Lucaogou Formation, indicating that increased pore structure heterogeneity enhances fluid flow resistance and thereby restricts overall reservoir flow capacity. Among the various lithofacies, the MFS and LDFS are characterized by higher pore volumes and lower Dc values, which correspond to superior storage capacity and seepage potential. Consequently, these lithofacies are identified as priority “sweet spot” targets for shale oil exploration in the region.

(4) This study develops a quantitative framework for evaluating reservoir quality based on lithofacies classification and fractal dimension analysis, establishing a foundation for identifying favorable zones in highly heterogeneous shale reservoirs. While the current research is primarily based on core-scale experiments, future work should focus on correlating the Dc with well-logging responses to create a regional heterogeneity assessment method utilizing log data. This approach would further facilitate a comparative analysis of the physical significance of different fractal methods, contributing to the development of a unified multi-scale fractal framework.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fractalfract9110703/s1, Table S1: Figure 8 data LPNA adsorption-desorption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and L.Z.; methodology, L.Z. and J.L.; validation, J.L., W.Y. and G.L.; formal analysis, W.Y.; investigation, X.C.; resources, Q.L.; data curation, M.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and W.Y.; visualization, Q.L.; supervision, L.Z. and G.L.; project administration, Q.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. and G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Cooperation Technology Projects of CNPC and CUPB (ZLZX2020-01-06), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42302148), the CNPC Innovation Fund (No. 2023DQ02-0103), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42090025).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yingyan Li and Xiaoxuan Chen were employed by Research Institute of Exploration and Development, Xinjiang Oilfield Company—PetroChina. The remaining authors declare that they have no knowncompeting financial interest or personal relationships that might have influenced the work presented in this article.

References

- Abouelresh, M.O.; Slatt, R.M. Lithofacies and sequence stratigraphy of the Barnett Shale in east-central Fort Worth Basin, Texas. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, M.E.; Cardott, B.J.; Sondergeld, C.H.; Rai, C.S. Development of organic porosity in the Woodford Shale with increasing thermal maturity. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 103, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Wen, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; He, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N. Analysis of the world oil and gas exploration situation in 2021. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvie, D.M.; Hill, R.J.; Ruble, T.E.; Pollastro, R.M. Unconventional shale-gas systems: The Mississippian Barnett Shale of north-central Texas as one model for thermogenic shale-gas assessment. AAPG Bull. 2007, 91, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S.A.; Gil-Alana, L.A.; Lafuente, C. An investigation of long range reliance on shale oil and shale gas production in the U.S. market. Energy 2020, 195, 116933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, E.; He, W. The development and utilization of shale oil and gas resources in China and economic analysis of energy security under the background of global energy crisis. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2024, 14, 2315–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhao, W.; Hou, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Wu, S.; Bai, B.; Jin, X. Development potential and technical strategy of continental shale oil in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Hu, S.; Zhenglian, P.; Senhu, L.; Lianhua, H.; Rukai, Z. The types, potentials and prospects of continental shale oil in China. China Pet. Explor. 2019, 24, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Hu, S.; Hou, L.; Yang, T.; Li, X.; Guo, B.; Yang, Z. Types and resource potential of continental shale oil in China and its boundary with tight oil. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Bai, Z.; Gao, B.; Li, M. Has China ushered in the shale oil and gas revolution? Oil Gas Geol. 2019, 40, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Liang, X. Exploration and Development of Shale Oil in China: State, Challenges, and Prospects. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2024, 65, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Tang, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, K.; Liu, J.; Du, D. A review of commercial development of continental shale oil in China. Energy Geosci. 2022, 3, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, B.; Chen, X. Status, trends and enlightenment of global oil and gas development in 2021. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 1210–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, T.; Yan, B.; Liu, R. Analysis of Controlling Factors of Pore Structure in Different Lithofacies Types of Continental Shale—Taking the Daqingzi Area in the Southern Songliao Basin as an Example. Minerals 2024, 14, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Bai, B.; Tao, S.; Bian, C.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhu, R.; Jia, J.; et al. Heterogeneous geological conditions and differential enrichment of medium and high maturity continental shale oil in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, X. A Comparison of Geological Characteristics of the Main Continental Shale Oil in China and the U.S. Lithosphere 2021, 2021, 3377705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, C.; Cao, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Han, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Distribution patterns of storage space and diagenesis in lacustrine shale controlled by laminae combinations—A case study from Jiyang depression. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2025, 180, 107488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qiao, J.; Zeng, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Kong, Z.; Liu, X. Heterogeneity of Micro- and Nanopore Structure of Lacustrine Shales with Complex Lamina Structure. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Stochastic models for the Earth’s relief, the shape and the fractal dimension of the coastlines, and the number-area rule for islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 3825–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guan, P.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X.; Ding, X.; You, Y. A review of the progress on fractal theory to characterize the pore structure of unconventional oil and gas reservoirs. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2023, 59, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, C.E.; Thompson, A.H. Fractal sandstone pores: Automated measurements using scanning-electron-microscope images. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 33, 6366–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Liu, G.; Yang, W.; Zou, H.; Sun, M.; Wang, X. Multi-fractal distribution analysis for pore structure characterization of tight sandstone—A case study of the Upper Paleozoic tight formations in the Longdong District, Ordos Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 92, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, L.; Gong, X. Nanoscale pore structure and fractal characteristics of a marine-continental transitional shale: A case study from the lower Permian Shanxi Shale in the southeastern Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 88, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, P.; Wu, Y.; Cole, M.W.; Krim, J. Multilayer adsorption on a fractally rough surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 62, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Pang, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, P.; Chen, D.; Shen, W.; Zhao, Z. Pore structure and fractal characteristics of organic-rich shales: A case study of the lower Silurian Longmaxi shales in the Sichuan Basin, SW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 80, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.-z.; Howard, J.; Lin, J.-S. Surface Roughening and the Fractal Nature of Rocks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Lin, W.; Han, D.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, X. Pore structure and fractal characteristics of coal-bearing Cretaceous Nenjiang shales from Songliao Basin, Northeast China. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2024, 9, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Dang, W. Pore Structure and Fractal Characteristics of Deep Shale: A Case Study from Permian Shanxi Formation Shale, from the Ordos Basin. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 9229–9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, K.; Hou, J.; Yan, L.; Chen, F. Diagenetic controls on the quality of the Middle Permian Lucaogou Formation tight reservoir, southeastern Junggar Basin, northwestern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2019, 178, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jin, Z.; Zeng, L.; Huang, L.; Ostadhassan, M.; Du, X.; Lu, G.; Zhang, Y. Natural fractures in deep continental shale oil reservoirs: A case study from the Permian Lucaogou formation in the Eastern Junggar Basin, Northwest China. J. Struct. Geol. 2023, 174, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Pang, X.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Ding, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Li, H. Oil content evaluation of lacustrine organic-rich shale with strong heterogeneity: A case study of the Middle Permian Lucaogou Formation in Jimusaer Sag, Junggar Basin, NW China. Fuel 2018, 221, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, K.; Huo, X.; Lin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K. Genetic mechanism of multi-scale sedimentary cycles and their impacts on shale-oil distribution in Permian Lucaogou Formation, Jimusar Sag, Junggar Basin. Unconv. Resour. 2023, 3, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Cao, Z.; Tao, S.; Felix, M.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, Y. Characteristics and formation mechanism of multi-source mixed sedimentary rocks in a saline lake, a case study of the Permian Lucaogou Formation in the Jimusaer Sag, northwest China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 102, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jin, Z.; Zhu, R.; Liu, K.; Bai, J. Comprehensive evaluation of the organic-rich saline lacustrine shale in the Lucaogou Formation, Jimusar sag, Junggar Basin, NW China. Energy 2024, 294, 130786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K.; Gao, Y.; Qin, Z. Fractal characteristics of the pore structures of fine-grained, mixed sedimentary rocks from the Jimsar Sag, Junggar Basin: Implications for lacustrine tight oil accumulations. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 182, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L.; Tang, Y.; Lei, D.; Chang, Q.; Ouyang, M.; Hou, L.; Liu, D. Formation conditions and exploration potential of tight oil in the Permian saline lacustrine dolomitic rock, Junggar Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2012, 39, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, D.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y.; Du, W.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; et al. Oil Mobility Evaluation of Fine-Grained Sedimentary Rocks with High Heterogeneity: A Case Study of the Lucaogou Formation in the Jimusar Sag, Junggar Basin, NW China. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 7679–7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Xu, C.; Qin, J.; Peng, S.; Yang, L.; et al. Effect of lithofacies on differential movable fluid behaviors of saline lacustrine fine-grained mixed sedimentary sequences in the Jimusar sag, Junggar Basin, NW China: Forcing mechanisms and multi-scale models. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 150, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Wan, M.; Jia, X.; Cao, Y.; Lei, D.; Qu, C. Depositional model for a salinized lacustrine basin: The Permian Lucaogou Formation, Jimsar Sag, Junggar Basin, NW China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2019, 178, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; Qiu, L.; Cao, Y.; Yang, S. Sedimentary characteristic and facies evolution of Permian Lucaogou formation in Jimsar sag, Junggar basin. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2015, 36, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T19145-2022; Determination for Total Organic Carbon in Sedimentary Rock. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 8.

- SY/T5124-2012; Determination of Vitrinite Reflectance in Sedimentary Rocks. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB/T21650.2-2008; Pore Size Distribution and Porosity of Solid Materials by Mercury Porosimetry and Gas Adsorption—Part 2: Analysis of Mesopores and Macropores by Gas Adsorption. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2008; p. 28.

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T21650.1-2008; Pore Size Distribution and Porosity of Solid Materials by Mercury Porosimetry and Gas Adsorption—Part 1: Mercury Porosimetry. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2008; p. 20.

- Washburn, E.W. The Dynamics of Capillary Flow. Phys. Rev. 1921, 17, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T34533-2023; Determination of Porosity, Permeability and Saturation of Shale. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2023; p. 20.

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; W. H. Freeman & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 51, p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Passoja, D.; Paullay, A.J. Fractal Character of Fracture Surfaces of Metal. Nature 1984, 308, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Weller, A. Fractal dimension of pore-space geometry of an Eocene sandstone formation. Geophysics 2014, 79, D377–D387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. Analytical derivation of Brooks–Corey type capillary pressure models using fractal geometry and evaluation of rock heterogeneity. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2010, 73, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broseta, D.; Barré, L.; Vizika, O.; Shahidzadeh, N.; Guilbaud, J.-P.; Lyonnard, S. Capillary Condensation in a Fractal Porous Medium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 5313–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Xie, M.; Hou, H.; Jiang, Z.; Song, Y.; Bao, S.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Peng, S.; Miao, K.; et al. Multifractal Characteristics of Heterogeneous Pore-Throat Structure and Insight into Differential Fluid Movability of Saline-Lacustrine Mixed Shale-Oil Reservoirs. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zheng, M.; Bi, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, X. Pore throat structure and fractal characteristics of tight oil sandstone: A case study in the Ordos Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 149, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Qu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lü, X. Microscopic Pore Structure Heterogeneity on the Breakthrough Pressure and Sealing Capacity of Carbonate Rocks: Insight from Monofractal and Multifractal Investigation. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Xue, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Z. Classification of microscopic pore-throats and the grading evaluation on shale oil reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, R.G.; Reed, R.M.; Ruppel, S.C.; Hammes, U. Spectrum of pore types and networks in mudrocks and a descriptive classification for matrix-related mudrock pores. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 1071–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jin, Z.; Zeng, L.; Chen, X.; Ostadhassan, M.; Wang, Q.; Lu, G.; Du, X. Laminar controls on bedding-parallel fractures in Permian lacustrine shales, Junggar Basin, northwestern China. GSA Bull. 2025, 137, 3512–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.C.; Peffer, L.A.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Pore size determination in modified micro- and mesoporous materials. Pitfalls and limitations in gas adsorption data analysis. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labani, M.M.; Rezaee, R.; Saeedi, A.; Hinai, A.A. Evaluation of pore size spectrum of gas shale reservoirs using low pressure nitrogen adsorption, gas expansion and mercury porosimetry: A case study from the Perth and Canning Basins, Western Australia. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 112, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Hou, J.; Dou, L.; Ma, K.; Wang, X. Lithological and diagenetic variation of mixed depositional units in the middle permian saline lacustrine deposition, Junggar Basin, NW China. Unconv. Resour. 2024, 4, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, F.; Yun, N.; Zeng, H.; Han, Y.; Hu, X.; Diao, N. Pore Structure Characteristics and Permeability Stress Sensitivity of Jurassic Continental Shale of Dongyuemiao Member of Ziliujing Formation, Fuxing Area, Eastern Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2022, 12, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yuan, B.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, E.; Ma, C.; Zhang, B. Genesis and pore development characteristics of Permian Lucaogou migmatites, Jimsar Sag, Junggar Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2022, 44, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, X.-F.; Zhang, D.-D.; Wang, Q.-T.; Luo, H.-Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, Z.-L.; Chen, Z.-X.; Liu, W.-H. Pore formation and evolution mechanisms during hydrocarbon generation in organic-rich marl. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjigin, T.; Lu, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Pan, A.; Shen, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Z. Formation, preservation and connectivity control of organic pores in shale. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Lai, F.; Gao, X.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, N.; Luo, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Peng, S.; Luo, X.; et al. Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of Pore Throat Structure of Shale Oil Reservoir in Saline Lake—A Case Study of Shale Oil of the Lucaogou Formation in Jimsar Sag, Junggar Basin. Energies 2021, 14, 8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Shen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, R.; Hou, H.; Li, Z.; Ding, M.; Hu, H.; Feng, F.; Xie, M. Comparative study on pore-connectivity and wettability characteristics of the fresh-water and saline lacustrine tuffaceous shales: Triggering mechanisms and multi-scale models for differential reservoir-forming patterns. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1410585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Fan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Wan, C.; Chen, Z. Differential impact of clay minerals and organic matter on pore structure and its fractal characteristics of marine and continental shales in China. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 216, 106334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yan, D.; Yao, C.; Su, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Pore Structure and Multi-Scale Fractal Characteristics of Adsorbed Pores in Marine Shale: A Case Study of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Shale in the Sichuan Basin, China. J. Earth Sci. 2022, 33, 1278–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Cheng, H. Gas Adsorption Characterization of Pore Structure of Organic-rich Shale: Insights into Contribution of Organic Matter to Shale Pore Network. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 30, 2377–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. Fractal Analysis of Pore–Throat Structures in Triassic Yanchang Formation Tight Sandstones, Ordos Basin, China: Implications for Reservoir Permeability and Fluid Mobility. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, T.; Chen, S.; Hu, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhuang, D. Pore Structure and Its Fractal Dimension: A Case Study of the Marine Shales of the Niutitang Formation in Northwest Hunan, South China. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).