Abstract

Brain electrical activity, as recorded through electroencephalography (EEG), displays scale-free temporal fluctuations indicative of fractal behavior and complex dynamics. This study explores the use of the Higuchi Fractal Dimension (HFD) as a proxy of two complementary aspects of EEG temporal organization: local signal irregularity, interpreted within a Kolmogorov-type framework, and persistence related to temporal structure, associated with statistical complexity. The latter can be used to evidence persistence in the EEG signal, serving as an alternative to previously used approaches for estimating the Hurst exponent. Thirty-eight healthy participants underwent resting-state EEG recordings in open- and closed-eyes conditions. HFD was computed for the original signals to assess Kolmogorov complexity and for the signals’ cumulative envelopes to evaluate statistical complexity and, consequently, persistence. The results confirmed that HFD values align with theoretical expectations: higher for random noise in the Kolmogorov model (~2) and lower in the statistical model (~1.5). EEG data showed condition-dependent and topographically specific variations in HFD, with parieto-occipital regions exhibiting greater complexity and persistence. The HFD values in the statistical model fall within the 1–1.5 range, indicating long-term correlation. These findings support HFD as a reliable tool for assessing both the local roughness and global temporal structure of brain activity, with implications for physiological modeling and clinical applications.

1. Introduction

Brain electrical activity, as detected by electroencephalography (EEG), exhibits intrinsic temporal fluctuations that exhibit scale-free properties, meaning that similar statistical patterns are observed across different time scales [1,2]. These dynamics reflect nonlinear interactions and have been interpreted in some frameworks as consistent with critical-like operating regimes [1,3]. Nevertheless, alternative generative mechanisms that do not require criticality have also been demonstrated, and the link between scale-free temporal dynamics and criticality remains an active area of research [3,4]. These dynamics are not adequately captured by classical spectral methods, prompting the use of nonlinear metrics to gain a deeper understanding of brain function [5]. In particular, when EEG signals show self-similar fluctuations over time, they are said to have fractal properties. This scale-free behavior can be quantified through measures such as the fractal dimension, which has been widely used to estimate the complexity of brain dynamics [6]. However, its direct relationship to neural complexity remains a topic of debate. Various methods have been developed to assess the fractal nature of EEG signals, particularly during resting-state and task conditions, in both physiological and neurological/psychiatric disease contexts. Among them, the Higuchi algorithm [7] is notable for directly estimating fractal dimension in the time domain, offering a high computational efficiency. It performs reliably even on short, noisy EEG segments and has been proven to be effective in both simulated and real data [8,9].

Complexity can be understood through at least two fundamentally different lenses, each rooted in distinct ideas about what makes a system ‘complex’. One widely known interpretation is algorithmic complexity, also referred to as Kolmogorov complexity [10,11]. This notion defines complexity as the length of the shortest computer program that can reproduce a given dataset. According to this framework, complexity increases with the degree of randomness in the data. The rationale is straightforward: if a dataset appears random, the most concise way to describe it is to directly encode the data itself, meaning the shortest program is nearly as long as the data. In this context, complexity refers to the temporal organization of EEG signals, which typically lies between two extremes: perfectly constant signals and random noise. Reduced complexity in brain signals has been linked to several neurological disorders, supporting the idea that complexity may reflect the brain’s functional efficiency.

Higuchi Fractal Dimension (HFD), when applied to raw EEG signals, has been widely used as a practical proxy for algorithmic irregularity, with values ranging from 1 (constancy) to 2 (random noise) [8,12]. Nevertheless, if taken strictly, Kolmogorov’s view would imply that a brain composed of randomly connected neurons is more complex than a functioning brain, or that white noise is more complex than meaningful neural activity. To address this point, an alternative framework, i.e., the ‘statistical complexity’, was proposed. This perspective focuses on the effort required to build a statistical complexity model of the data and tends to yield complexity values that peak at intermediate levels of randomness [13,14,15,16]. Canonical formulations of statistical complexity include the López-Ruiz–Mancini–Calbet (LMC) statistical complexity, which combines entropy and disequilibrium to quantify structured order in stochastic systems [14], and the Crutchfield–Young framework, which defines statistical complexity as the amount of information required for optimal prediction, formalized in terms of causal states and ε-machines [11,17]. These measures are explicitly model-based and require estimating probability distributions and/or state-space reconstructions.

Previously, the Hurst exponent (H) has been used to quantify long-range temporal correlations and self-affinity in a time series [18,19]. It can be considered a measure of long-term correlation or persistence in a time series, i.e., the extent to which past values influence future values. A Hurst exponent value of 0.5 indicates random behavior (no long-term correlation or trend), while values above 0.5 suggest a persistent or trending series (long-term correlation; the higher the value, the stronger the trend), and values below 0.5 suggest mean reversion. For a self-affine signal, the Hurst exponent H (being 0 < H < 1) and fractal dimension FD (being 1 < FD < 2) are associated by the relationship H + FD = 2. Under the assumptions of self-affinity and monofractality, HFD values between 1 and 1.5 are consistent with persistence, values between 1.5 and 2 with anti-persistence, and HFD = 1.5 may reflect no trend (random noise). However, HFD should be interpreted as an approximate, scale-dependent proxy, and its mapping to persistence or anti-persistence is not deterministic but model- and scale-dependent. The Hurst exponent can correlate with aspects of statistical complexity, as it captures temporal dependence: higher values of H, indicative of persistent dynamics, often correspond to a greater degree of structural organization, which may increase statistical complexity up to a certain point. Thus, H can serve as a proxy for specific aspects of EEG statistical complexity, particularly in self-affine signals. Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA) is the most widely used method to estimate the Hurst exponent in EEG time series, as it reliably quantifies long-range temporal correlations in nonstationary physiological signals [20,21].

To our knowledge, the Higuchi Fractal Dimension (HFD) has not been used to quantify the persistence of EEG signals and, consequently, to evaluate a proxy measure of their statistical complexity. This work aims to verify that HFD can reliably quantify both Kolmogorov complexity and persistence (statistical complexity) in EEG data from healthy adults at rest, thereby retrieving long-term correlation properties in the latter case, as previously documented by other methods. HFD computed from the raw EEG signal is interpreted as a proxy for algorithmic irregularity, whereas HFD calculated from the cumulative sum of the EEG amplitude envelope is used to probe persistence-related temporal structure, commonly associated with statistical complexity.

The estimation of long-range temporal structure associated with persistence in this study relies on applying the HFD to the cumulative sum of the EEG amplitude envelope. This approach is motivated by the theoretical relationship between fractal dimension and long-range temporal dependence in self-affine stochastic processes, in which the Hurst exponent H and the fractal dimension FD are asymptotically related by H + FD = 2. While this relationship is strictly valid only for ideal self-affine monofractal processes such as fractional Brownian motion, it provides a practical modeling framework for interpreting persistence in empirical time series over restricted scale ranges. In EEG signals, long-range temporal correlations are known to be more robustly expressed in slow amplitude fluctuations than in the fast oscillatory carrier. For this reason, the amplitude envelope is commonly used to isolate slow dynamics associated with large-scale neuronal coordination [22]. In contrast, oscillatory components dominate short temporal scales and violate self-affine assumptions. Applying HFD to the cumulative sum of the envelope emphasizes these slow fluctuations and suppresses local oscillatory structure, thereby enabling a scale-dependent approximation of persistence-related dynamics.

Importantly, in the present work, self-affinity is not assumed as a global or intrinsic property of EEG signals, but rather as a scale-restricted modeling approximation. The validity of this approximation is empirically assessed by evaluating the convergence between HFD-based estimates and DFA-derived Hurst exponents at sufficiently large temporal scales. Under these conditions, the HFD of the cumulative envelope provides an operational proxy for long-range temporal dependence.

Moreover, it should be explicitly and unambiguously stated that the terminology adopted in this work reflects an interpretative framework that is widely and consistently adopted in the EEG fractal-analysis literature [6,8,23], rather than implying any formal or theoretical equivalence with algorithmic Kolmogorov-like complexity, as defined in information theory [10,14]. In this empirical context, HFD is used to characterize signal irregularity and geometric roughness in the time domain, which has been repeatedly interpreted as an operational approximation of algorithmic randomness in neurophysiological signals, while remaining conceptually distinct from formal definitions of algorithmic complexity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. EEG Recordings and Pre-Processing

Thirty-eight healthy volunteers (aged 19–45 years, including 14 females) were enrolled in this study. All subjects were right-handed and were not receiving any pharmacological treatment at the time of recordings. Restricting the sample to right-handed participants was intended to minimize inter-individual variability related to hemispheric dominance and functional lateralization, which can modulate the spatial organization and time-frequency dynamics of EEG activity [24,25]. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Provinces of Chieti and Pescara (Project identification code: rich0ct4h) on 7 September 2017. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Five-minute open-eyes and five-minute closed-eyes EEG recordings were acquired with a sampling frequency of 250 Hz by a 128-channel system (Electrical Geodesic). Data were filtered between 1 and 40 Hz and sub-sampled at 125 Hz for offline processing. Six peripheral electrodes (neck and face reference sensors) were excluded, leaving 122 channels for analysis. A semiautomatic procedure based on Independent Component Analysis [26,27] was applied to identify and eliminate artifacts (e.g., eye movements, cardiac activity, scalp muscle contractions). The average number (standard deviation) of rejected ICs across recordings was 12 ± 5. Data were referenced to the common average.

2.2. Higuchi Fractal Dimension

Fractal dimension (FD) was calculated for each EEG channel to estimate Kolmogorov complexity. We used the algorithm proposed by Higuchi [7], which directly estimates the mean length of the curve L(k) in units of measure formed by a segment of k samples. From any given time series of N samples , k new time series with initial time sample m and time step k can be derived as follows:

where the symbol denotes the nearest integer less than or equal to the number, m = 1,2, … k and k = 1, 2, … kmax, being kmax a free parameter. The length of each curve can be estimated as follows:

For each k, the mean length of the curve L(k) is calculated as follows:

The calculation of the curve length L(k) in Equation (3) is repeated for k = 1, 2, … kmax.

Complexity properties depend on the temporal fluctuations in the amplitude of EEG signals. The curve is said to have fractal dimension β if:

The plot of log(L(k)) against log(k) should fall on a straight line with slope equal to HFD so that a least-squares linear best-fitting procedure can obtain HFD. Since HFD is highly dependent on the value of kmax, this parameter, together with the length of the signal, has a crucial role in HFD estimation. Several methods have been proposed to choose the value of kmax. To compare the effect of different sizes of kmax, we calculated the HFD values in non-overlapping windows of 2 s, 5 s, 60 s, and 300 s, with a kmax equal to 1/5 of the window size, to obtain a reliable estimate of the mean of Equation (3) (corresponding to kmax = 60, 125, 1500 and 7500, respectively). The HFD values of the windows were averaged. As a global HFD value, the HFD for each EEG channel was averaged.

In the original 1988 paper where Higuchi introduced his method, the algorithm was validated using simulated data with a fractal dimension of 1.5. These data were generated as the cumulative sum of Gaussian noise with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1. Because, for white noise, a fractal dimension of 1.5 corresponds to a Hurst exponent of 0.5 (from the relationship HFD + H = 2), we replicated this approach by applying the HFD algorithm to the cumulative sum of the envelope of EEG signals to estimate their persistence. In this context, values near 1.5 indicate no memory, values above 1.5 suggest an anti-persistent effect, and values below 1.5 point to persistence in the time series. Using this method to estimate the statistical complexity and long-term correlation properties of EEG signals, the HFD was calculated from the cumulative sum of the EEG signal envelope. The envelope was obtained from the magnitude of the Hilbert transform of the time series. In this case as well, the overall HFD value was determined by averaging the HFD across EEG channels.

Finally, to provide reference values confirming the method’s feasibility for calculating both Kolmogorov and statistical complexity, HFD values were obtained from 38 white-noise and 38 pink-noise realizations with the same sampling frequency and length as the EEG signals. Noise simulations were included solely for methodological benchmarking and parameter calibration, rather than for validating EEG complexity per se, as they provide reference signals with well-defined theoretical scaling properties that enable systematic evaluation of estimator behavior and parameter sensitivity under controlled conditions. HFD was calculated directly on the raw signal (Kolmogorov complexity) and on the detrended cumulative sum of its envelope (statistical complexity), as performed for EEG signals. Since HFD values range from 1 to 2 for white noise, we expect similar values near 2 for pink noise. In fact, 1/fβ noise can be associated with a fractal dimension D = (5 − β)/2, which, for β = 1, yields D ≈ 2. For the second model, we expect HFD values close to 1.5 for white noise and approximately 1 for pink noise.

2.3. Detrended Fluctuation Analysis

The Hurst exponent was calculated using the Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA) [20], which quantifies long-range temporal correlations while requiring less stringent assumptions about signal stationarity. Specifically, DFA computes the detrended fluctuations of the amplitude envelope across multiple time scales n, i.e., the fluctuation function F(n). For each EEG signal, the amplitude envelope was obtained as the modulus of the analytic signal, derived via the Hilbert transform. Finally, the cumulative sum of the envelope was computed for subsequent DFA. The cumulative sum obtained from the amplitude envelope was subsequently divided into Ns non-overlapping windows of equal length s. Within each window, the local trend was estimated using a least-squares linear fitting procedure, as described by [21]. Let xj,s (i) denote the ordinate of the fitted line in the j-th segment of length s at time bin i (for i = 1,2, … s), the scale function for the j-th segment represents the root-mean-square deviation from the local trend and is computed as:

To compute the fluctuation function, the average root-mean-square deviation from the local trend was calculated across all segments for each temporal scale s, following the procedure described by [21]:

The scaling behavior of the fluctuation function can be evaluated by constructing a log–log plot of F(s) as a function of the time scale s. If the signal exhibits long-range power-law correlations, the following relationship holds:

where H represents the Hurst exponent [28]. In this case, the log–log plot yields a linear relationship, with slope H.

At small scales, systematic deviations from scaling-law behavior can be observed [29]. Thus, we empirically selected the minimum scale value as 8. For large scales, the number Ns becomes very small, and too few segments can be averaged for a statistically reliable estimate of the scale function F(s). Thus, we excluded scales log2(s) > 13 from the fitting procedure. We considered 20 values of log2(s), equally spaced between 8 and 13, for the scaling function. These values correspond to segments ranging from s = 28 = 256 time points (i.e., a length of approximately 2 s) to s = 213 = 8196 time points (corresponding to segments with a duration of about 65 s).

The goodness of the log-log linear fits was quantified using the coefficient of determination (R2), computed from the residual sum of squares. While a high R2 indicates a good linear approximation over the selected scale range, it does not by itself imply true scale invariance and should be interpreted as a descriptive measure of fit quality. Although no universal threshold exists, R2 values exceeding 0.95 are commonly reported in EEG scaling analyses and are generally considered indicative of a satisfactory linear approximation within the analyzed scale range [22]. In our sample, the R2 means (±standard deviation) across channels and subjects were 0.975 ± 0.008 and 0.974 ± 0.008 for open-eyes and closed-eyes conditions, respectively.

Hurst exponent was calculated for each EEG channel, and the average over channels was then computed as a global measure.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The average of HFD values across channels, derived from both EEG signals and the cumulative sum of their envelopes, was compared across different window lengths and corresponding kmax values. Additionally, physiological differences between the open- and closed-eyes conditions were examined. To achieve this, a 4 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA was used on HFD values, with Kmax (four levels: 60, 125, 1500, and 7500) and Condition (two levels: open-eyes, closed-eyes) as within-subject factors. Mauchly’s test checked the assumption of sphericity [30]. Post hoc comparisons employed paired-samples t-tests with a Tukey correction for multiple comparisons.

Values of HFD evaluated from realizations of white and pink noise were reported as mean and 5th–95th percentile.

Given that the spectral content of EEG signals differs between open-eyes and closed-eyes conditions, with significant changes in band power and overall power spectrum across resting states in healthy subjects, EEG spectral features vary systematically between these conditions and should be accounted for in complexity analyses [31]. Indeed, differences in HFD values between the two conditions could be driven by spectral properties rather than by temporal organization beyond the power spectrum. Thus, a control analysis was performed to test whether observed differences reflect non-linear dynamics rather than linear spectral differences. Phase-randomized surrogate EEG signals were generated for each subject and condition by preserving the amplitude (Fourier) spectrum while randomizing the Fourier phases, a well-established surrogate data method that conserves the linear spectral properties of a time series and removes higher-order temporal dependencies [32]. HFD was then computed on surrogate data, using the same parameter settings and analysis pipeline as for the original recordings, for both Kolmogorov complexity and statistical complexity models. An ANOVA design identical to that used for the original data was applied to surrogate data. This procedure enabled a direct comparison of original and surrogate data under open- and closed-eye conditions to assess whether HFD differences exceed those expected from linear spectral differences alone.

To evaluate whether specific EEG channels consistently showed higher or lower values compared to the overall scalp distribution, each participant’s HFD value was first converted into Z-scores across the 122 channels. This normalizes inter-individual differences in overall amplitude while maintaining topographical patterns. For each channel, the resulting Z-scores from all 38 participants were subjected to a one-sample t-test against zero to determine if the mean significantly deviated from the group’s spatial average. Since 122 × 2 statistical tests were conducted (one for each channel under both open and closed eyes conditions), multiple comparison correction was performed using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method, following the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure [33]. Channels with corrected p-values below the significance threshold were considered to show reliable deviations from the global scalp distribution, indicating consistent topographical features across participants. To characterize the spatial distribution of the open- versus closed-eyes contrast, channel-wise effect sizes were computed for each EEG channel, separately for each tested kmax value and for both complexity formulations. In addition, condition differences at each channel were assessed using paired-sample t-tests (open- vs. closed-eyes). To control for multiple comparisons across channels, p-values were corrected using FDR procedure. Effect-size values were visualized as scalp topographies.

Finally, the HFD values, obtained from the cumulative sums of the EEG envelope signals for different kmax, were correlated with Hurst exponents derived from Detrended Fluctuation Analysis. Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship. To verify that the relationship HFD + H = 2 holds, the sum of HFD values and Hurst exponents was calculated for each subject. These values were then compared to 2 using a one-sample t-test.

Effect sizes are reported as generalized eta squared () for ANOVA effects, and as Cohen’s dz (hereafter referred to as Cohen’s d, Lakens 2013 [34]) for paired comparisons and one-sample tests against a reference value.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of kmax and Condition on HFD in Empirical EEG Data

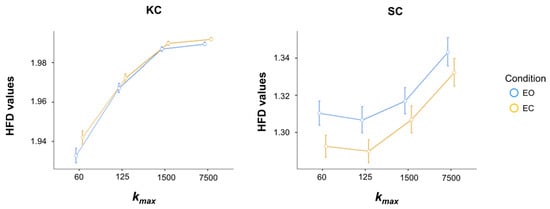

ANOVA on the HFD values for the Kolmogorov complexity model revealed a significant main effect of Kmax [F(3, 111) = 483.41; p < 0.001; = 0.716, with HFD values increasing as kmax increased, based on post hoc comparisons (Figure 1, left). There was also a significant main effect of Condition [F(1, 37) = 9.54; p = 0.004; = 0.032], indicating that complexity was higher in the eyes-open condition compared to the eyes-closed condition, regardless of kmax values (Figure 1, left). However, a significant Kmax × Condition interaction was observed [F(3, 111) = 6.36; p < 0.001; = 0.010], as the difference between eyes closed and eyes open conditions diminishes as kmax increases (mean ± standard deviation: for Kmax = 60: 9.1 × 10−3 ± 3.1 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.466; for Kmax = 125: 5.1 × 10−3 ± 1.8 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.469; for Kmax = 1500: 2.9 × 10−3 ± 0.9 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.522; for Kmax = 7500: 2.4 × 10−3 ± 0.6 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.634; p < 0.007, consistently).

Figure 1.

Mean (standard deviation) of HFD values for the Kolmogorov complexity model (KC, left) and for the statistical complexity model (SC, right) in eyes open (EO, cyan) and eyes closed (EC, yellow) conditions for different kmax values.

In the case of statistical complexity, HFD values between 1 and 1.5 indicate long-term correlation in EEG signals. Also in this case, HFD values increased with kmax, as assessed by the significant Kmax main effect [F(3, 111) = 70.82; p < 0.001; = 0.121, Figure 1, right]. HFD values were lower in the eyes closed than in the eyes open condition [significant Condition main effect: F(1, 37) = 5.05; p = 0.031; = 0.027, Figure 1, right]. No significant interaction was found (p > 0.200).

3.2. Control Analysis Using Phase-Randomized Surrogate Data

ANOVA on the HFD values of surrogate data for the Kolmogorov complexity model revealed a significant main effect of Kmax [F(3, 111) = 198.52; p < 0.001; = 0.470]. HFD values increased as kmax increases (marginal means: 1.966 ± 0.003; 1.973 ± 0.002; 1.990 ± 0.001; 1.973 ± 0.001, for kmax = 60, 125, 125, 1500 and 7500, respectively). HFD values were higher in the open-eyes condition compared to the closed-eyes condition, regardless of kmax [Condition effect, F(1, 37) = 8.17; p = 0.007; = 0.028]. A significant Kmax × Condition interaction was also found [F(3, 111) = 9.78; p < 0.001; = 0.010]. The difference between open-eyes and closed-eyes conditions diminishes as kmax increases (mean ± standard deviation: for kmax = 60: 7.3 × 10−3 ± 2.4 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.485; for kmax = 125: 5.3 × 10−3 ± 1.7 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.472; for kmax = 1500: 2.3 × 10−3 ± 0.8 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.439; for kmax = 7500: 1.4 × 10−3 ± 0.6 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.359; p < 0.033, consistently).

For statistical complexity model, HFD values of surrogate data increased with kmax [Kmax main effect, F(3, 111) = 429.6; p < 0.001; = 0.420; marginal means: 1.379 ± 0.006; 1.375 ± 0.006; 1.406 ± 0.005; 1.435 ± 0.004, for kmax = 60, 125, 125, 1500 and 7500, respectively]. HFD values were lower in the closed-eyes than in the open-eyes condition [significant Condition main effect: F(1, 37) = 36.8; p < 0.001; = 0.125]. A significant Kmax × Condition interaction was also found observed [F(3, 111) = 25.5; p < 0.001; = 0.008], as the difference between eyes closed and eyes open conditions diminishes as kmax increases (mean ± standard deviation: for kmax = 60: 0.029 ± 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.485; for kmax = 125: 0.029 ± 0.005, Cohen’s d = 0.472; for kmax = 1500: 0.021 ± 0.005, Cohen’s d = 0.439; for kmax = 7500: 0.016 ± 0.003, Cohen’s d = 0.359; p < 0.001, consistently).

3.3. Noise Benchmarks for HFD Estimation

As expected, the HFD values for white noise are close to 2 and 1.5 for the Kolmogorov and statistical complexity models, respectively (Table 1). HFD values for random noise remained constant with increasing kmax values in both complexity models. Values near 2 were also observed for pink-noise realizations (Kolmogorov complexity), whereas HFD values for the statistical complexity model were approximately 1.25. Additionally, for pink noise, the HFD values were independent of kmax.

Table 1.

Mean (5th–95th percentile) of HFD values of the 38 realizations of white noise and pink noise for the 2 models of complexity (Kolmogorov: KC, Statistical, SC), for different kmax values.

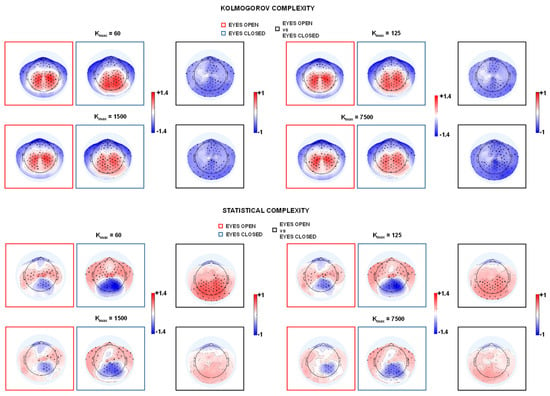

3.4. Topographic Organization of HFD Values

The scalp topography of Z-scores for HFD values exhibited a consistent spatial organization across the tested kmax values in both eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions, and across both complexity formulations. As illustrated by the highlighted panels in Figure 2 (red and blue boxes), Z-score distributions showed systematic regional differences: higher standardized HFD values were localized predominantly over parieto-occipital channels, whereas lower Z-scores were more prominent over frontal and lateral temporal regions. This pattern was reproducible across parameter settings, indicating that the observed regional contrast in HFD values is stable and not driven by a specific choice of kmax. Channel-wise effect-size maps for the open-eyes versus closed-eyes contrast revealed a spatially heterogeneous distribution of effects across the scalp. Larger positive effect sizes were consistently observed over centro-parietal and parieto-occipital regions, with bilateral symmetry and maxima along posterior midline areas, whereas frontal and lateral temporal channels showed smaller effects, often close to zero. The paired-sample t-tests identified clusters of channels that remained significant after FDR correction (indicated by stars), which were largely co-localized with regions showing larger effect sizes. Importantly, the overall topographic organization, particularly the posterior dominance of the contrast, was preserved across different kmax values and across both complexity models.

Figure 2.

HFD topography (mean across subjects, Z-score) in closed-eye (blue box) and open-eye (red box) conditions for different values of kmax in the case of Kolmogorov complexity (top) and statistical complexity (bottom). Stars indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05, FDR-corrected) of one-sample t-tests against 0, i.e., they indicate reliable deviations (red: higher, blue: lower) from the global scalp distribution, indicating consistent topographical features across participants. In the black boxes, the topographic maps display Cohen’s d values for the open- vs. closed-eyes comparison to illustrate effect size. Asterisks indicate channels that reached statistical significance (after FDR correction for multiple comparisons) based on paired t-tests. Positive Cohen’s d values indicate higher values in the open-eyes condition relative to the closed-eyes condition, whereas negative values indicate higher values in the EC condition.

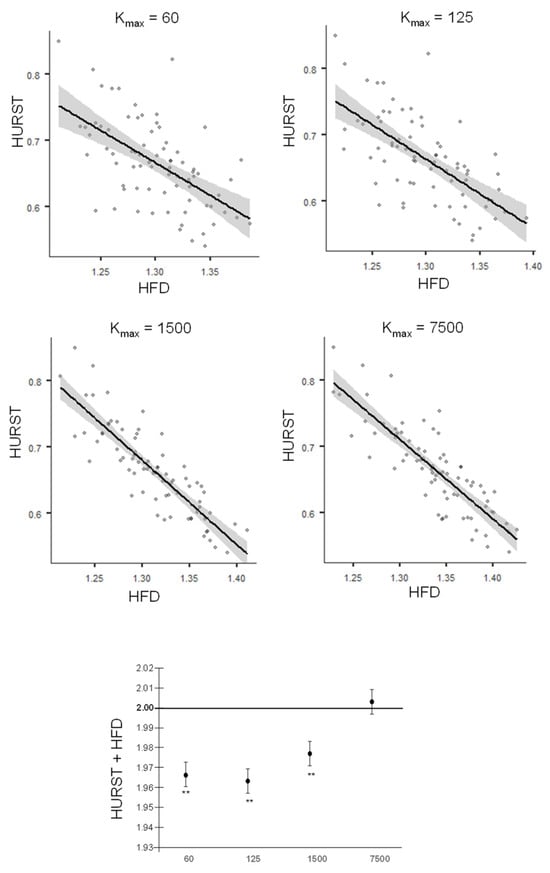

3.5. Relationship Between HFD and the Hurst Exponent

A strong correlation was observed between HFD values, calculated from the cumulative sum of the envelope of EEG signals, and the Hurst exponent (H) estimated by Detrended Fluctuation Analysis. The Pearson correlation coefficient values increased with kmax: r = −0.578, p < 0.001 for kmax = 60; r = −0.656, p < 0.001 for kmax = 125; r = −0.861, p < 0.001 for kmax = 1500; r = −0.843, p < 0.001 for kmax = 7500 (Figure 3, top). The lower part of Figure 3 shows the mean (standard error) of the sum of HFD and H for different kmax values. A one-sample t-test comparing these sums with 2 showed significant differences for kmax = 60 [t(75) = −5.43; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = −0.623], kmax = 125 [t(75) = −5.43; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = −0.736], and kmax = 1500 [t(75) = −5.43; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = −0.643]. Only for kmax = 7500 did the test indicate that the sum was not significantly different from 2 (p > 0.200).

Figure 3.

Top: Topoplot of the Hurst exponent values obtained by Detrended Fluctuation Analysis over HFD values for the statistical model (average across channels), for different values of kmax. Bottom: mean (standard error) of the sum between the Hurst exponent and the HFD values for different kmax. Stars indicate significance of one-paired t-test against.

4. Discussion

Our results showed that the Higuchi fractal dimension can reliably measure not only the complexity but also the persistence of temporal correlations in brain electrical activity. Therefore, HFD can evaluate different aspects of EEG signals: a local aspect, assessing the “roughness” of a signal (such as “mild” or “wild” randomness), and a global trait, indicating the long-term correlation within the time series.

A classical method for estimating these latter properties is the Hurst exponent, via DFA. We demonstrated that the HFD values of EEG time series obtained in the case of the statistical complexity model (between 1 and 1.5) are consistent with those found to estimate Hurst exponent H in the EEG time series using DFA (between 0.5 and 1), as predicted by the relationship H + FD = 2.

The HFD quantifies the geometric complexity of a time series by measuring the roughness of its trajectory in the time-amplitude plane. For uncorrelated Gaussian white noise, which represents the maximally irregular case, the estimated HFD approaches the upper theoretical limit, typically HFD ≈ 1.9–2.0 for finite realizations [6,7,35]. Also, for pink noise, we confirmed HFD values near 2.0. The HFD of the cumulative sum of the envelope of white noise was near 1.5, similar to the value found for the cumulative sum of white noise and corresponding to a Hurst exponent of 0.5. For reference, ideal pink noise, when modeled as a stationary fractional Gaussian noise process, is theoretically associated with a Hurst exponent close to unity (H ≈ 1), indicating strong long-range persistence in the signal [36]. However, in finite-length realizations or empirical data, the estimated Hurst exponent is often slightly lower (typically H ≈ 0.8–1.0) due to finite-size effects and deviations from ideal 1/f scaling [36]. Our data support these findings, with HFD values for statistical complexity evaluation of approximately 1.25. According to the relationship HFD + H = 2, these values correspond to Hurst exponents of 0.75.

A central methodological issue concerns the strong dependence of HFD estimates on both window length and the choice of the algorithm’s tuning parameter kmax, which determines the range of temporal scales included in the HFD estimation. Since Higuchi’s original formulation does not prescribe a universal criterion for selecting kmax [7], subsequent methodological and EEG studies have emphasized that HFD estimates are sensitive to this parameter and that inappropriate parameter choices may introduce bias or saturation effects, particularly when kmax approaches the length of the time series and the number of available averages for Lm(k) (see Equation (2)) becomes critically small [37,38,39]. Specifically, for each scale k, the HFD algorithm estimates the curve length by averaging Lm(k) over multiple starting points m, and reliable estimation therefore requires a sufficiently large number of such averages. As k increases, the number of available starting points decreases, leading to increased variance and reduced stability of the estimated scaling slope. Consequently, excessively large kmax values can result in curve-length saturation and inflated variance due to insufficient averaging at large scales, whereas overly small kmax values overemphasize short-scale fluctuations and bias HFD toward lower values [39,40]. Moreover, increasing kmax progressively incorporates coarser temporal scales into the log-log regression of curve length, thereby shifting the estimator’s baseline without necessarily reflecting changes in the underlying signal dynamics.

In the present study, kmax was selected as a conservative fraction of the analysis window (approximately one-fifth of the signal length), a choice intended to ensure adequate sampling of coarse temporal scales while maintaining a sufficient number of Lm(k) averages for a stable estimation. Larger kmax values were explored to probe the asymptotic properties of the estimator and to assess convergence, particularly with respect to the relationship between HFD and DFA-derived Hurst exponents. Our choice of kmax = 1/5 of the window length follows a conservative, empirically grounded heuristic, sometimes adopted in the HFD literature, aimed at balancing the inclusion of sufficiently large temporal scales to capture long-range structure with the avoidance of instability and saturation effects that arise when kmax approaches the signal length.

Importantly, although not framed as a separate sensitivity analysis, robustness with respect to kmax is implicitly addressed by the systematic evaluation of four markedly different values spanning more than two orders of magnitude. As expected, absolute HFD values increased monotonically with kmax in both the Kolmogorov and statistical complexity formulations, reflecting the intrinsic scale dependence of the estimator. This observation implies that, for EEG signals, absolute HFD values should not be interpreted independently of the scale range under analysis. Instead, physiological interpretation should rely primarily on condition contrasts, spatial topography, and cross-method convergence, particularly agreement with DFA-derived Hurst exponents, rather than on raw HFD magnitude alone [18,21]. Indeed, condition-related effects (open- vs. closed-eyes) remained statistically significant across all tested values, with preserved effect direction and comparable effect sizes, indicating that the physiological contrast is not driven by a specific parameter choice. The extremely small effect size of the kmax × Condition interaction in the Kolmogorov complexity model, together with its absence in the statistical complexity formulation, further suggests that variations in kmax primarily modulate the baseline level of HFD estimates rather than their condition dependence. This interpretation is directly supported by the surrogate data analysis. For statistical complexity, phase-randomized surrogate data exhibit a pronounced scale dependence, absent in the original data: specifically, the open-eyes versus closed-eyes effect size progressively decreases with increasing kmax, indicating a strong attenuation of condition-related differences at longer temporal scales when only spectral properties are preserved. The absence of a comparable decay in the original data suggests that genuine temporal structure counteracts this scale-dependent attenuation, resulting in a more stable condition effect across scales rather than an artificial amplification of effect magnitude. Taken together, these results support the practical recommendation to select kmax as a fixed fraction of the analysis window (approximately 15–25%), while emphasizing that absolute HFD values should be interpreted on a scale-aware basis and that robustness should be verified when the window length or sampling rate is changed.

Notably, our simulations on both white- and pink-noise benchmarks demonstrated that HFD estimates remained stable across the tested kmax values, indicating low parameter sensitivity of the estimator in controlled reference signals and supporting the use of these simulations as methodological checks of estimator stability and interpretability.

For both models, HFD values were influenced by physiological conditions and showed a topographic distribution that was independent of kmax. In the Kolmogorov complexity model, our results indicated that the parieto-occipital and central regions exhibit higher HFD values during the closed-eyes condition than during the open-eyes condition, suggesting lower cortical activity complexity when visual input is present. In the statistical complexity model, our findings are consistent with previous research on the Hurst exponent of alpha- and beta-rhythm amplitude during resting-state EEG. Interestingly, the absence of a significant Kmax × Condition interaction indicates that, across the tested range, the open- versus closed-eyes difference behaves approximately as an additive offset on the HFD metric, with kmax modulating the baseline level of the estimate without differentially affecting the condition contrast. Mechanistically, this is plausible because envelope-based persistence is dominated by slow amplitude modulations spanning seconds to tens of seconds, a regime that is similarly sampled in both conditions once sufficiently large scales are included, while the open-/closed-eyes difference may reflect a relatively stable shift in persistence associated with changes in sensory drive or arousal. By contrast, in the Kolmogorov complexity model, HFD is applied directly to raw EEG, in which scale-dependent changes in rhythmic content, particularly alpha activity, can differentially influence local roughness at smaller scales and compress open-eyes vs. closed-eyes differences as kmax increases. This compression at larger kmax values may reflect scale-dependent characteristics of the Higuchi method rather than a true absence of physiological contrast. Finite-length effects and deviations from ideal scale invariance can lead to saturation or bias at coarser scales, which tend to compress condition differences in absolute terms even if the qualitative contrast remains [37]. This perspective suggests that the diminishing difference with increasing kmax may be driven by estimator properties and scale effects rather than a genuine loss of physiological information at longer scales.

However, the use of phase-randomized surrogate data is essential to disentangle changes driven by spectral and amplitude modulations from those arising from temporal organization, allowing the contribution of scale-dependent temporal structure beyond the power spectrum to be explicitly assessed. Absolute HFD values in phase-randomized surrogate data were systematically shifted toward values characteristic of stochastic, spectrally matched processes (e.g., colored noise), indicating that phase randomization effectively suppresses non-linear temporal dependencies (and thus values approaching 2 for Kolmogorov complexity model and 1.5 for the statistical complexity model). Taken together, the surrogate analysis reveals differential roles for spectral and temporal contributions across the two complexity formulations. In the Kolmogorov complexity model, the persistence of the open- versus closed-eyes effect in phase-randomized surrogates indicates a strong spectral contribution, whereas the attenuation of the effect at longer temporal scales relative to the original data suggests an additional scale-dependent component not fully explained by power-spectrum preservation. In contrast, for statistical complexity, the open-eyes versus closed-eyes differences are largely accounted for by spectral and amplitude-related changes, as no scale-dependent modulation is observed in the original data; such modulation emerges only in surrogate signals, where temporal correlations beyond the spectrum are destroyed.

We observed an HFD topography aligned with a higher Hurst exponent over posterior (parieto-occipital) regions, where alpha activity is strongest, and a lower Hurst exponent over frontal areas, reflecting reduced long-range temporal correlations in the anterior regions [22,41]. Additionally, a persistent temporal structure when visual input is minimized (closed-eyes condition), and arousal is lower, has also been documented previously [22]. Conversely, opening the eyes systematically reduces the Hurst exponent that indicates long-range dependence, consistent with increased sensory input and arousal disrupting the development of temporal persistence in the EEG signal. The channel-wise analyses confirm that the significant global open-eyes versus closed-eyes contrast is accompanied by region-dependent variations in effect magnitude rather than uniform changes across the scalp. Larger effects concentrated over centro-parietal and parieto-occipital regions suggest that the condition-related modulation is spatially structured, while smaller effects over frontal and temporal areas likely reflect weaker expression of the same contrast rather than a reversal in effect direction. The consistency of the effect-size topographies across parameter settings, together with the convergence between regions of larger effects and FDR-corrected significance, argues against the interpretation that the global contrast is driven by a small subset of electrodes or by parameter-specific artifacts. Instead, the results support a distributed physiological modulation with region-dependent strength, highlighting the complementary roles of global summary metrics for methodological comparisons and channel-wise analyses for interpreting regional expression.

Several authors have emphasized that HFD and DFA should not be considered interchangeable, as the two measures are based on different assumptions and respond differently to the properties of physiological signals. One major advantage of HFD is that it can be applied directly to short, nonstationary time series, such as EEG, without the need for segmentation or detrending [8]. In contrast, DFA assumes at least weak stationarity of fluctuations after detrending and generally requires longer recordings to obtain stable scaling estimates. DFA also tends to overestimate the Hurst exponent for short time series [29]. In practice, EEG epochs lasting only a few seconds, especially in clinical or event-related settings, may not provide sufficient spectral range for reliable DFA fitting. Conversely, HFD can capture the signal’s geometric complexity even within limited windows. Additionally, DFA involves dividing the signal into multiple windows and fitting polynomial trends across scales, thereby requiring decisions about window sizes, detrending orders, and frequency content. These choices can bias the estimated exponent, particularly when the data include mixed oscillatory and aperiodic components or significant low-frequency drifts [29,41]. HFD avoids many of these issues by estimating fractal characteristics directly in the time domain, thereby reducing sensitivity to contamination, physiological artifacts, and transient non-stationarities. Its computational simplicity also makes HFD more suitable for real-time or high-density applications, like neurofeedback and BCI, where speed and noise robustness are critical.

Our approach to evaluating statistical complexity is based on the idea that if an EEG time series can be modeled as a fractional Gaussian noise process, its cumulative series exhibits fractional Brownian motion behavior. Indeed, envelope extraction of EEG signals shifts the analysis from carrier oscillations and phase-related structure toward slow amplitude fluctuations, which are the signal component most commonly used to quantify long-range temporal correlations in EEG via DFA [42]. Subsequent cumulative summation further emphasizes low-frequency components by integrating the amplitude fluctuations, such that the slope estimated by the HFD method in the log–log relationship between curve length and scale becomes predominantly sensitive to long-range, global persistence of the signal rather than to local, short-scale irregularities. In this context, the HFD can be used as an estimate of the signal’s graph dimension, which in turn serves as an indirect measure of the Hurst exponent H. This idea was present in Higuchi’s original study, in which he validated his method by computing the fractal dimension of a white-noise realization after computing its cumulative sum. The HFD obtained was 1.5, indicating a Hurst exponent of 0.5.

Although the relationship between the Hurst exponent and the Fractal Dimension is widely reported, it is strictly valid only for strictly self-affine and monofractal processes such as fractional Brownian motion [43,44]. Therefore, applying this relationship to empirical signals like EEG requires caution, as real-world data are often non-stationary, noisy, or multifractal [23,45]. For this reason, in the present study the relationship between HFD and DFA-derived Hurst exponents is interpreted empirically, based on scale-dependent convergence, rather than assumed as a strict theoretical property of the EEG signal. More generally, the assumption that H = 2 − FD should not be considered universally valid unless the underlying scaling properties and self-affinity of the signal are explicitly confirmed. Additionally, interpreting EEG as a self-affine time series is supported but not definitively proven. Prior research has shown that resting-state EEG exhibits scale-invariant dynamics and long-range temporal correlations, consistent with fractal or self-affine processes. Early work by [41] demonstrated long-range temporal correlations in human EEG alpha-band oscillations, consistent with self-affinity. Power-law and scaling behaviors described by [5,46] suggest that EEG fluctuations lack a characteristic timescale and may exhibit fractal dynamics. Reviews by [8] further support the view that the EEG exhibits scale-invariant properties. Moreover, the observation that resting-state EEG exhibits a characteristic power-law decay of spectral power has long been recognized in electrophysiology. Early work by [47] showed that the human EEG exhibits a 1/f-like frequency distribution, supported by evidence of scale-invariant activity in related neurophysiological signals [48]. Theoretical and computational models propose that such aperiodic scaling may originate from intrinsic neural circuit properties or network-level phenomena [49,50]. Empirical evidence from invasive recordings supports the idea that the spectral slope reflects core features of neural population dynamics and can change with functional engagement [51]. Finally, several studies also note variability in the exponent across individuals, brain regions, and behavioral states, suggesting that resting-state spectral slope reflects both physiological constraints and cognitive context, and that its alteration may indicate neural dysfunction [52,53,54,55,56,57].

Taken together, these findings support an approximately self-affine organization of EEG signals across specific temporal scales and have encouraged the use of models such as fractional Gaussian noise and fractional Brownian motion in electrophysiological research.

We showed that the Hurst exponent H and HFD follow the relationship H = 2 − HFD in both open- and closed-eye conditions, consistent with self-affine dynamics. This relationship holds for long window lengths and high kmax values in HFD evaluation, that is, for windows similar to the maximal scale used in the DFA procedure. Indeed, the increasing correlation between HFD and H with kmax reflects the asymptotic nature of long-range dependence: persistence emerges only at sufficiently large temporal scales, and HFD converges toward DFA-derived H only when kmax allows the estimator to probe the same scaling regime. For shorter windows, the sum of H and HFD is significantly less than 2. Both the DFA and the Higuchi method estimate scaling exponents from log-log relationships evaluated over discrete ranges of scales. However, they differ in how the scaling regime entering the fit is selected and weighted. In DFA, short window sizes, where oscillatory components, trends, and nonstationarities dominate, are explicitly excluded, and the Hurst exponent is estimated over a restricted range of larger window sizes chosen to approximate the asymptotic scaling regime. In contrast, the Higuchi method estimates fractal dimension from the scaling of curve length with step size k over a finite range up to kmax, such that contributions from both short and long temporal scales are jointly weighted in the log-log plot slope estimation. As a consequence, for small to intermediate kmax, the HFD estimate can remain influenced by short-scale amplitude fluctuations, residual oscillatory structure, and local irregularities, which are not expected to follow the same scaling law captured by DFA. This difference in scale weighting provides a plausible explanation for the reduced correspondence between HFD and DFA-derived Hurst exponents at smaller kmax values. However, even in the case of small or intermediate kmax, the strong correlations between HFD and H values indicate that HFD is suitable for assessing long-term correlations in shorter windows, and thus for EEG signals of brief duration.

However, EEG is also known to be nonstationary and potentially multifractal, especially under different cognitive states, pathological conditions, or across frequency bands [8]. Therefore, while assuming approximate self-affinity is methodologically reasonable for extracting fractal metrics or scaling exponents and for using the relationship between the Hurst exponent and Fractal Dimension, such assumptions should be seen as modeling choices rather than definitive descriptions of the underlying neural activity. Future research should directly test self-affinity in EEG rather than assuming it, and compare monofractal methods with multifractal or state-dependent analyses. In this regard, the present results should be interpreted as capturing an effective, scale-averaged description of temporal organization, rather than as a definitive characterization of potentially multifractal EEG dynamics. Despite these limitations, we empirically demonstrated that the Hurst exponent estimated by Detrended Fluctuation Analysis is strongly associated with the Hurst exponent of cumulative EEG time series, making HFD a reliable and efficient method for detecting long-range correlations in EEG signals. Therefore, the proposed approach may be regarded as a practical and computationally efficient proxy for long-range dependence in EEG amplitude dynamics, whose validity is supported by its empirical agreement with DFA rather than by a strict theoretical equivalence.

Combining the two methods for evaluating Kolmogorov and statistical complexity using HFD may, in the future, offer valuable insights for developing meaningful physiological models of brain activity and its changes in neurological diseases. HFD estimation of EEG signals has proven vital for analyzing brain dynamics: its speed, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness distinguish it from commonly used linear methods for physiological EEG assessment and medical diagnosis [9]. Additionally, applying HFD directly to raw signals, alongside techniques that capture long-term correlations, may yield more precise insights into various neurophysiological signals and neurological conditions. Since the present analysis is based on resting-state EEG data, extending this framework to sensorimotor and cognitive task paradigms represents a necessary step toward broader generalization [58]. In this context, evaluating the proposed approach’s ability to distinguish mental or cognitive states is particularly relevant [59]. Future work will focus on addressing these aspects.

The advantage of HFD over DFA is particularly clear for very short time series, where HFD produces more accurate results than DFA. Although extending the present analysis to older or clinical populations would be highly informative for assessing potential clinical relevance, the current study was deliberately designed as a methodological investigation in a homogeneous sample of healthy young adults. This choice was motivated by the need to minimize confounding from age, neurological pathology, medication, and cognitive impairment, thereby enabling a clearer evaluation of the methodological properties of HFD. Accordingly, the primary aim of this work is not to propose clinical biomarkers, but to assess whether HFD, implemented in two distinct operational modes, can reliably capture local signal irregularity and persistence-related temporal structure, and whether the latter converges with established DFA-based Hurst exponent estimates. Establishing this methodological validity under controlled conditions is a necessary prerequisite for future applications in more heterogeneous or pathological populations, in which alterations in long-range temporal correlations have been widely reported.

5. Conclusions

This study supports the use of the Higuchi Fractal Dimension as a proxy measure of signal complexity and temporal persistence in EEG time series. Quantitative analysis shows that HFD yields stable estimates and exhibits systematic variation with the parameter kmax, which defines the range of temporal scales included in the computation, while preserving relative physiological differences across conditions. HFD values exhibit a relationship with the Hurst exponent obtained via Detrended Fluctuation Analysis, with greater consistency observed at longer temporal scales. These results indicate that HFD values are inherently scale-dependent and support the use of HFD as a computationally efficient proxy for jointly characterizing signal irregularity and temporal persistence when the analysis parameters are explicitly defined.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C. and F.Z.; methodology, F.Z.; software, P.C. and F.Z.; validation, P.C. and F.Z.; formal analysis, F.Z.; investigation, F.Z.; data curation, P.C. and F.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C. and F.Z.; writing—review and editing, P.C. and F.Z.; funding acquisition, F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received external funding from “PRIN: PROGETTI DI RICERCA DI RILEVANTE INTERESSE NAZIONALE—Bando 2022 PNRR, D.D. n. 1409/2022, Prot. P20225HWLZ, funded by European Union—NextGenerationEU. Research project title: “EEG connectivity as an innovative biomarker to improve QUAlity of LIfe and The burden of disease in people with drug resistant epilepsY (EQUALITY)”, CUP: D53D23019080001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the pro-tocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Provinces of Chieti and Pescara (Project identification code: rich0ct4h) on 7 September 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access to the dataset will be granted for research purposes in compliance with institutional and ethical regulations. For data analysis, EEG preprocessing was performed using EEGLAB [60] running under MATLAB R2024b. Higuchi Fractal Dimension was computed using a MATLAB implementation based on a publicly available script [61], with parameter settings explicitly reported in the Methods section. Detrended Fluctuation Analysis was implemented by adapting MATLAB scripts described in [62], following the original methodological specifications. All statistical analyses were performed using jamovi, version 2.4 [63].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| HFD | Higuchi Fractal Dimension |

| FD | Fractal Dimension |

| H | Hurst Exponent |

| DFA | Detended Fluctuation Analysis |

| KC | Kolmogorov Complexity |

| SC | Statistical Complexity |

References

- He, B.J. Scale-Free Brain Activity: Past, Present, and Future. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzsáki, G.; Mizuseki, K. The Log-Dynamic Brain: How Skewed Distributions Affect Network Operations. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, M.A.; Chu, C.J. A General, Noise-Driven Mechanism for the 1/f-Like Behavior of Neural Field Spectra. Neural Comput. 2024, 36, 1643–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shew, W.L.; Plenz, D. The Functional Benefits of Criticality in the Cortex. Neuroscientist 2013, 19, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, C.J. Nonlinear Dynamical Analysis of EEG and MEG: Review of an Emerging Field. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2005, 116, 2266–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardo, A.; Affinito, M.; Carrozzi, M.; Bouquet, F. Use of the Fractal Dimension for the Analysis of Electroencephalographic Time Series. Biol. Cybern. 1997, 77, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T. Approach to an Irregular Time Series on the Basis of the Fractal Theory. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1988, 31, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesić, S.; Spasić, S.Z. Application of Higuchi’s Fractal Dimension from Basic to Clinical Neurophysiology: A Review. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2016, 133, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moaveninejad, S.; Cauzzo, S.; Porcaro, C. Fractal Dimension and Clinical Neurophysiology Fusion to Gain a Deeper Brain Signal Understanding: A Systematic Review. Inf. Fusion 2025, 118, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Three Approaches to the Quantitative Definition of Information *. Int. J. Comput. Math. 1968, 2, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitin, G.J. On the Length of Programs for Computing Finite Binary Sequences. J. ACM 1966, 13, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armonaite, K.; Conti, L.; Balsi, M.; Paulon, L.; Tecchio, F. Analysis of Power Law Behavior of Local Cortical Neurodynamics. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2025, 477, 134733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberman, B.A.; Hogg, T. Complexity and Adaptation. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1986, 22, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, J.P.; Young, K. Inferring Statistical Complexity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 63, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ruiz, R.; Mancini, H.L.; Calbet, X. A Statistical Measure of Complexity. Phys. Lett. A 1995, 209, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.P.; Crutchfield, J.P. Structural Information in Two-Dimensional Patterns: Entropy Convergence and Excess Entropy. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 67, 051104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, J.P. The Calculi of Emergence: Computation, Dynamics and Induction. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1994, 75, 11–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardstone, R.; Poil, S.-S.; Schiavone, G.; Jansen, R.; Nikulin, V.V.; Mansvelder, H.D.; Linkenkaer-Hansen, K. Detrended Fluctuation Analysis: A Scale-Free View on Neuronal Oscillations. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.L.; Vásquez-Coronel, J.A. Analyzing Monofractal Short and Very Short Time Series: A Comparison of Detrended Fluctuation Analysis and Convolutional Neural Networks as Classifiers. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.K.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.E.; Goldberger, A.L. Quantification of Scaling Exponents and Crossover Phenomena in Nonstationary Heartbeat Time Series. Chaos 1995, 5, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantelhardt, J.W.; Zschiegner, S.A.; Koscielny-Bunde, E.; Havlin, S.; Bunde, A.; Stanley, H.E. Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis of Nonstationary Time Series. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2002, 316, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulin, V.V.; Brismar, T. Long-Range Temporal Correlations in Electroencephalographic Oscillations: Relation to Topography, Frequency Band, Age and Gender. Neuroscience 2005, 130, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, Z.J.; Pham, T.; Chen, S.H.A.; Makowski, D. Brain Entropy, Fractal Dimensions and Predictability: A Review of Complexity Measures for EEG in Healthy and Neuropsychiatric Populations. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 56, 5047–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, R.M.; Van der Haegen, L.; Fisher, S.E.; Francks, C. On the Other Hand: Including Left-Handers in Cognitive Neuroscience and Neurogenetics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAssey, M.; Dowsett, J.; Kirsch, V.; Brandt, T.; Dieterich, M. Different EEG Brain Activity in Right and Left Handers during Visually Induced Self-Motion Perception. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbati, G.; Porcaro, C.; Zappasodi, F.; Rossini, P.M.; Tecchio, F. Optimization of an Independent Component Analysis Approach for Artifact Identification and Removal in Magnetoencephalographic Signals. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004, 115, 1220–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, P.; Zappasodi, F.; Marzetti, L.; Merla, A.; Pizzella, V.; Chiarelli, A.M. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Feature-Less Automatic Classification of Independent Components in Multi-Channel Electrophysiological Brain Recordings. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 66, 2372–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jens, F. Fractals; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpena, P.; Gómez-Extremera, M.; Bernaola-Galván, P.A. On the Validity of Detrended Fluctuation Analysis at Short Scales. Entropy 2022, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauchly, J.W. Significance Test for Sphericity of a Normal n-Variate Distribution. Ann. Math. Stat. 1940, 11, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.J.; De Blasio, F.M. EEG Differences between Eyes-Closed and Eyes-Open Resting Remain in Healthy Ageing. Biol. Psychol. 2017, 129, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, T.; Schmitz, A. Improved Surrogate Data for Nonlinearity Tests. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilatate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteller, R.; Vachtsevanos, G.; Echauz, J.; Lilt, B. A Comparison of Fractal Dimension Algorithms Using Synthetic and Experimental Data. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Orlando, FL, USA, 30 May–2 June 1999; pp. 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, A.; Malamud, B.D. Quantification of Long-Range Persistence in Geophysical Time Series: Conventional and Benchmark-Based Improvement Techniques. Surv. Geophys. 2013, 34, 541–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasić, S.; Kalauzi, A.; Culić, M.; Grbić, G.; Martać, L. Estimation of Parameter Kmax in Fractal Analysis of Rat Brain Activity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1048, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalauzi, A.; Bojić, T.; Rakić, L. Extracting Complexity Waveforms from One-Dimensional Signals. Nonlinear Biomed. Phys. 2009, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanliss, J.A.; Wanliss, G.E. Efficient Calculation of Fractal Properties via the Higuchi Method. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 109, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, C.; Mediavilla, A.; Hornero, R.; Abásolo, D.; Fernández, A. Use of the Higuchi’s Fractal Dimension for the Analysis of MEG Recordings from Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Med. Eng. Phys. 2009, 31, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkenkaer-Hansen, K.; Nikouline, V.V.; Palva, J.M.; Ilmoniemi, R.J. Long-Range Temporal Correlations and Scaling Behavior in Human Brain Oscillations. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, D.J.A.; Linkenkaer-Hansen, K.; de Geus, E.J.C. Long-Range Temporal Correlations in Resting-State Alpha Oscillations Predict Human Timing-Error Dynamics. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 11212–11220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Van Ness, J.W. Fractional Brownian Motions, Fractional Noises and Applications; SIAM Review: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, K.J. Fractal Geometry—Mathematical Foundations and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eke, A.; Herman, P.; Kocsis, L.; Kozak, L.R. Fractal Characterization of Complexity in Temporal Physiological Signals. Physiol. Meas. 2002, 23, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinov, M.; Sporns, O.; van Leeuwen, C.; Breakspear, M. Symbiotic Relationship between Brain Structure and Dynamics. BMC Neurosci. 2009, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, W.S.; Duke, D.W. Measuring Chaos in the Brain: A Tutorial Review of Nonlinear Dynamical EEG Analysis. Int. J. Neurosci. 1992, 67, 31–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novikov, E.; Novikov, A.; Shannahoff-Khalsa, D.; Schwartz, B.; Wright, J. Scale-Similar Activity in the Brain. Phys. Rev. E 1997, 56, R2387–R2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, C.; Kröger, H.; Destexhe, A. Does the 1/f Frequency Scaling of Brain Signals Reflect Self-Organized Critical States? Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 118102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, C.; Destexhe, A. Macroscopic Models of Local Field Potentials and the Apparent 1/f Noise in Brain Activity. Biophys. J. 2009, 96, 2589–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.J.; Sorensen, L.B.; Ojemann, J.G.; Den Nijs, M. Power-Law Scaling in the Brain Surface Electric Potential. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, N.; Bédard, C.; Cash, S.S.; Halgren, E.; Destexhe, A. Comparative Power Spectral Analysis of Simultaneous Elecroencephalographic and Magnetoencephalographic Recordings in Humans Suggests Non-Resistive Extracellular Media. J. Comput. Neurosci. 2010, 29, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.J.; Rosen, B.Q.; Belger, A.; Voytek, B.; Campbell, A.M. Aperiodic Neural Activity Is a Better Predictor of Schizophrenia than Neural Oscillations. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2023, 54, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.A.; Napolitani, M.; Boly, M.; Gosseries, O.; Casarotto, S.; Rosanova, M.; Brichant, J.-F.; Boveroux, P.; Rex, S.; Laureys, S.; et al. The Spectral Exponent of the Resting EEG Indexes the Presence of Consciousness during Unresponsiveness Induced by Propofol, Xenon, and Ketamine. Neuroimage 2019, 189, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzone, J.; Colombo, M.A.; Sarasso, S.; Zappasodi, F.; Rosanova, M.; Massimini, M.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Assenza, G. EEG Spectral Exponent as a Synthetic Index for the Longitudinal Assessment of Stroke Recovery. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 137, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, T.; Haller, M.; Peterson, E.J.; Varma, P.; Sebastian, P.; Gao, R.; Noto, T.; Lara, A.H.; Wallis, J.D.; Knight, R.T.; et al. Parameterizing Neural Power Spectra into Periodic and Aperiodic Components. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Ren, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, R.; Sun, L.; Ma, Q. Decoding Alzheimer’s: The Role of EEG Rhythms and Aperiodic Components in Cognitive Decline. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2025, 181, 2111437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valjarevic, S.; Paunovic Pantic, J.; Cumic, J.; Corridon, P.R.; Pantic, I. Fractal Analysis of Auditory Evoked Potentials: Research Gaps and Potential AI Applications. Fractal Fract. 2026, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentim, C.A.; Inacio, C.M.C.; David, S.A. Fractal Methods and Power Spectral Density as Means to Explore EEG Patterns in Patients Undertaking Mental Tasks. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An Open Source Toolbox for Analysis of Single-Trial EEG Dynamics Including Independent Component Analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Complete Higuchi Fractal Dimension Algorithm. Available online: https://it.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/30119-complete-higuchi-fractal-dimension-algorithm (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Ihlen, E.A.F. Introduction to Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis in Matlab. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamovi Desktop—Jamovi. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org/download.html (accessed on 12 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.