Abstract

The microstructure of polyurethane (PU) grouting material is the key determinant of its macroscopic dielectric properties. In this study, based on its microscopic fractal characteristics and combined with effective medium theory and the Menger sponge structure, an n-stage fractal dielectric model was constructed. This model correlates the material’s dielectric response with its fractal dimension and porosity. The fractal dimensions of PU specimens with densities ranging from 0.29734 g/cm3 to 0.41817 g/cm3 were calculated using the box-counting method. Within this density range, the fractal dimension of the PU specimens showed no significant variation, with a calculated value of approximately 2.7355. By approximating the microscopic unit as an n-stage fractal cube based on the Menger sponge structure and incorporating series-parallel dielectric models, an analytical expression for the dielectric constant was derived. A comparison with experimental data shows that the model’s predictions are in good agreement with the measured values, with a mean relative error (MRE) of only 4%.

1. Introduction

In the detection and evaluation of PU grouting effects, non-destructive testing techniques such as ground-penetrating radar are commonly used. The key parameter obtained from these detections is the dielectric constant, which is influenced not only by environmental changes but also varies with the porosity of the material. The PU grouting material possesses a high porosity foam structure, and its microscopic pore structure affects the macroscopic dielectric properties and durability of the material. Therefore, studying the pore characteristics of materials is of great significance and serves as the foundation for non-destructive testing and dielectric property research. Fractal theory is widely employed to characterize porous media [1,2,3,4,5,6], with its fractal dimension serving to quantify the material’s self-similarity. Based on this theory, a fractal model can be applied to simulate the pore structure of PU grouting materials and analyze their dielectric properties. This facilitates the establishment of a dielectric model that bridges the microstructure and macroscopic dielectric response, thereby correlating the microscopic fractal characteristics with the dielectric properties. Ultimately, this achieves a multiscale characterization from the microscale to the macroscale.

Scholars both domestically and internationally have applied fractal theory to study the fractal characteristics of porous media in various fields. Krohn et al. [7] first used scanning electron microscope (SEM) images to accurately measure the fractal dimension of various sandstone microstructures, which ranged from 2.55 to 2.75. They also defined and measured the length limit of the fractal state. Li et al. [8] used synchrotron radiation micro-angle X-ray scattering technology to study the fractal structure of porous silica materials and found that the material exhibits fractal characteristics both macroscopically and microscopically. Lv et al. [9] discovered through multifractal spectra that as the concentration of nitric acid increases, the number and width of nanofibers inside the material change with the concentration of nitric acid, revealing the fractal characteristics of the material. Peng et al. [10] used digital image processing methods combined with fractal theory to analyze industrial CT scans of rock slices. They concluded that the fractal dimension of rock pore structures increases with the increase in the porosity ratio, verifying and illustrating that the fractal dimension calculated from CT images can appropriately represent the characteristics of rock pores. Liu [11] studied the preparation and performance of superhydrophobic wood based on fractal theory. Bird et al. [12] studied the fractal and multifractal analysis of soil profile images. Their results showed that the extraction of fractal dimensions and multifractal spectra from images is not affected by local density and pore fractal structure. Liu et al. [13] applied a multi-scale fractal method to analyze the relationship between the porosity ratio and the fractal dimension of pore structures in shale. Pesquet-Popescu et al. [14] proposed several stochastic fractal models for describing the structure and characteristics of images. By simulating the fractal characteristics of images, they provided direction and ideas for the field of image processing.

To describe the fractal characteristics of different media, various fractal models have been proposed successively. Wen et al. [15] established a correlation model between GCLC pore structure and macroscopic mechanical properties based on fractal theory. Perrier et al. [16] proposed a model for the hydraulic characteristics of soil with fractal pore structure. Jain et al. [17] and Hatte et al. [18] proposed a fractal model to describe the wettability on multi-scale random rough surfaces. Wei et al. [19] proposed a mineral resource prediction model. Zhang et al. [20] proposed a fractal model for describing gas permeation in porous membranes. In addition, fractal models have also been applied in the study of soil water retention curves [21], the macroscopic elastic properties of stochastic porous media [22], and the microstructure of cement samples [23]. Atzeni et al. [24] obtained pore data of 13 different subgrade materials by the mercury intrusion method in the laboratory, and compared the prediction results of two fractal geometry models. It is concluded that the Menger sponge model is more representative in predicting fractal dimensions.

The application of fractal theory in the field of porous media research is not limited to exploring the pore structure of materials, but also involves studying the thermal conductivity characteristics of materials. Pitchumani et al. [25,26] proposed a unified treatment method using local fractal dimension as an analytical tool. By simplifying the analysis of the cells within the material, they developed a thermal model that demonstrates the effectiveness of fractal theory in predicting the electrical conductivity of composites with both ordered and disordered fiber arrangements. Zhang et al. [27,28] proposed a self-similar model for the effective thermal conductivity of porous media based on thermo-electric analogy technology and the statistical self-similarity of porous media. This model includes parameters such as porosity and area. After comparative analysis with other models, they found that the predicted values of this model are consistent with the measured values.

In terms of dielectric properties, most research by scholars both domestically and internationally has focused on composite materials. Rayleigh [29] hypothesized that the polarization behavior in dielectric materials is due to the orientation of molecules in an external electric field, establishing the Rayleigh model. Subedi et al. [30] constructed a dielectric model for multiphase asphalt mixtures (SC model) based on experimental data. Garnett [31] obtained the MG dielectric model by modifying the Clausius–Mossotti equation, which is mainly used to predict the effective dielectric constant of composites containing small particles dispersed in another dielectric material (matrix). This model has wide applications in materials science, nanotechnology, and optics. Mironov et al. [32] established a soil dielectric model that includes soil moisture, texture, mineral content, and frequency, providing an important reference for studying the relationship between soil dielectric properties and factors such as soil type, moisture, and mineral content. It has broad application prospects in soil electromagnetics, agricultural science, environmental monitoring, and other fields. Domestically, the team led by Academician Wang Fuming [33,34] has established a physical model of asphalt mixture based on the microstructure analysis of asphalt mixture, considering the interfacial transition zone between asphalt and mineral aggregates as well as the gradation of mineral aggregates. By combining effective medium theory with the composite sphere method, this model has higher computational accuracy compared to classical models. Fang et al. [35,36] and Zhang et al. [37] have applied the concept of flexible anti-seepage to study and develop new polymer grouting materials for dam reinforcement, and established a dielectric property calculation model for PU grouting materials based on ground-penetrating radar electromagnetic wave measurement results. Zhong [38] established a forward propagation model of ground-penetrating radar electromagnetic waves with complex dielectric properties. Li [39] has explored the influence of multiphase volume ratios of asphalt mixtures on dielectric properties through experimental research and model establishment, and established a forward model of ground-penetrating radar electromagnetic wave propagation based on the dielectric model.

In conclusion, scholars both domestically and internationally have applied fractal theory to study the pore structure or thermal conductivity characteristics of porous media, mainly focusing on rocks, soils, wood, silica, etc. However, there is relatively little research on the dielectric properties of PU grouting materials.

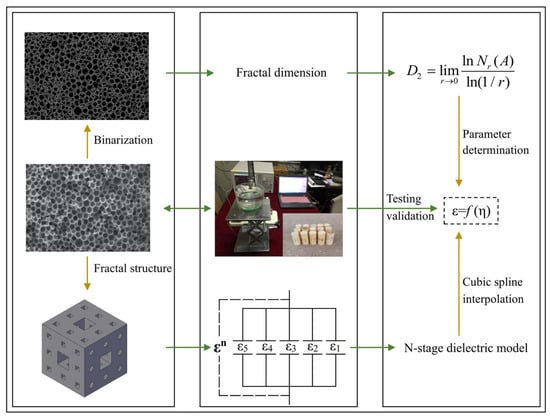

Based on the fractal characteristics of PU grouting material, this study approximates the microscopic unit as a Menger sponge structure and establishes an n-stage fractal dielectric model according to series-parallel dielectric models. The deterministic and highly ordered Menger sponge fractal structure is correlated with the porous structure of PU grouting materials featuring random pore size distributions. This approach facilitates the analysis of dielectric properties at the level of the material’s microscopic pore structure. First, a box-counting dimension method based on binary images was developed on the Python 3.10 platform to calculate the fractal dimension of the PU grouting material. Subsequently, trial calculations were performed with various parameter relationships, and the discrete model predictions were fitted using cubic spline interpolation to derive a continuous function between the dielectric constant and porosity. This function was then compared with experimental data to determine the model parameters, ultimately yielding the final fractal dielectric model. The research roadmap is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Roadmap.

2. Fractal Dimension Calculation of Polyurethane Grouting Materials

2.1. Fractal Theory

In Euclidean geometry, integer dimensions are used to describe the dimensions of regular geometric shapes, with points, lines, surfaces, and solids having dimensions of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively, known as topological dimensions. For regular geometries, each dimension is associated with a corresponding measure: length for one dimension, area for two dimensions, and volume for three dimensions, referred to as characteristic scales. These measures are independent of the units of measurement used. However, most objects in nature are disordered and irregular, such as coastlines, clouds, rivers, mountains, and islands. Their corresponding scales depend on the measurement units. For example, in the measurement of coastline length, the shorter the yardstick used, the longer the coastline appears. Clearly, this does not conform to the description of Euclidean geometry.

To describe these disordered and irregular objects, the concept of fractal dimension was introduced by Mandelbrot. This is defined as a non-integer dimension used to characterize complex, irregular geometric shapes in nature that exhibit self-similarity across different scales.

2.2. Box-Counting Method Based on Binary Image

PU grouting material is a type of porous material, and its microscopic structure exhibits self-similarity across different scales, which is known as fractal characteristics. These fractal characteristics can be quantitatively described by the fractal dimension, which reflects the complexity and irregularity of the internal structure of porous materials, such as porosity, pore size distribution, and pore shape. A higher fractal dimension indicates a higher porosity, more uneven pore size distribution, greater self-similarity, and more complex pore shapes.

2.2.1. Box-Counting Method

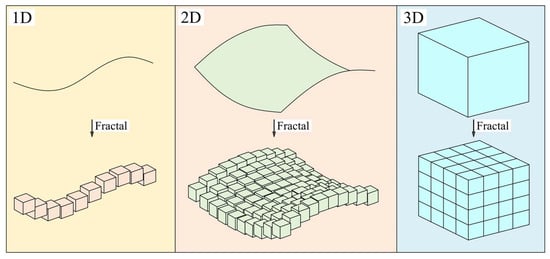

The Box-counting method is one of the methods for calculating fractal dimension [40]. It has a solid theoretical foundation, strong versatility, and simple calculation, as shown in Equation (5). Using small cubes (boxes) with a side length

to cover a line segment of unit length, a square with unit side length, and a cube, requires

,

, and

boxes, respectively, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cubes (boxes) covering the geometric body diagram.

Assuming the object to be covered by the boxes is

, representing any non-empty bounded subset of

space, then:

where

is the minimum number of n-dimensional cubes (boxes) with edge length

required to cover

;

is the edge length of the cube (box);

is the Box-counting dimension of

.

If and only if there exists a positive number

such that:

Taking the logarithm of both sides of the equation gives:

Since

,

and

. The calculation of the fractal dimension can be transformed into Equation (5).

According to Equation (5), the fractal dimension is determined as the slope of the fitted straight line obtained by performing a least-squares linear regression on the data points (,

) in a log-log plot.

2.2.2. Box Counting Method Based on the Binary Image and Algorithm Validation

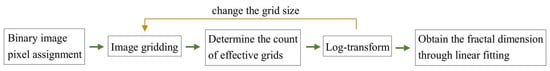

This article employs the Box-counting method based on binary images to calculate the fractal dimension of PU grouting materials. This algorithm is an adaptive threshold method that utilizes spatial constraints and considers the local intensity characteristics of the image, making it applicable to any shape. It mainly consists of five steps, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Calculation process of fractal dimension.

(1) The microscopic image ( pixels) was binarized using its mean gray value as the threshold.

(2) The binary image is partitioned into non-overlapping blocks of size

pixels, where

is a positive integer.

(3) The number of effective grid blocks is denoted as

, yielding a data point (,

).

(4) By varying the value of

, steps (2) and (3) were repeated to generate a set of data points.

(5) A linear regression of the data points was performed in a double-logarithmic plot using the least-squares method. According to fractal theory, the slope of the resulting fitted line corresponds to the two-dimensional (2D) fractal dimension of the microstructure of the PU grouting material.

Based on the above steps, programming is performed on the Python 3.10 platform. The primary libraries utilized included NumPy, OpenCV, xlwt, os, matplotlib, and Pillow. First, the SEM image is converted to RGB format using OpenCV functions. Then, the RGB image is converted to a grayscale image using the weighted average method with weights of 0.2989, 0.5870, and 0.1140. The grayscale image is then subjected to binarization processing to obtain the binarized image, and its 2D fractal dimension is calculated.

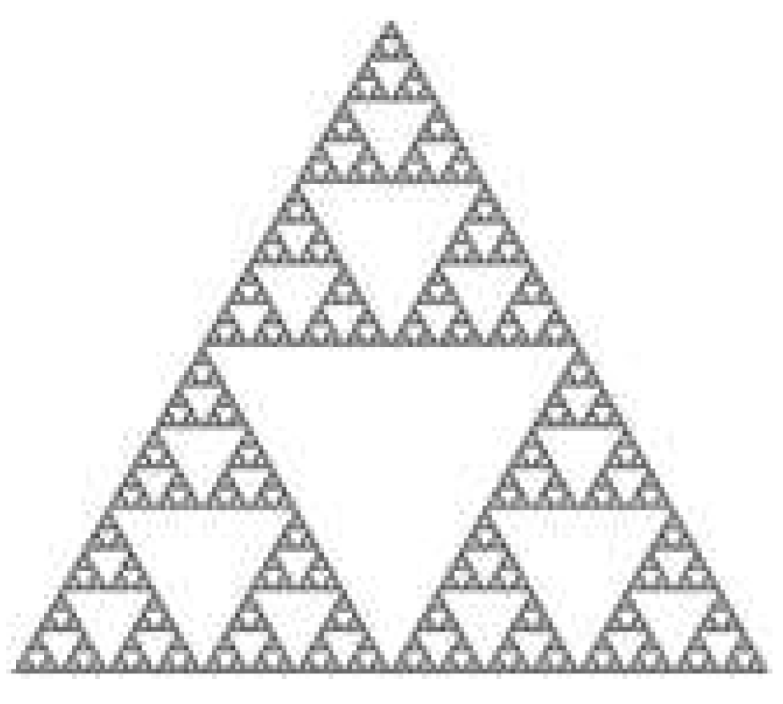

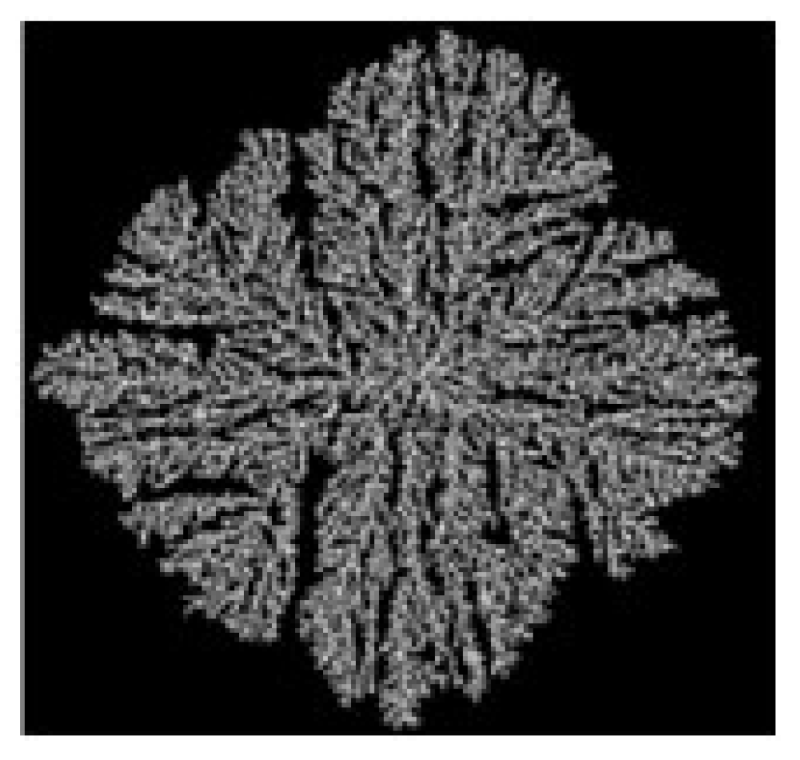

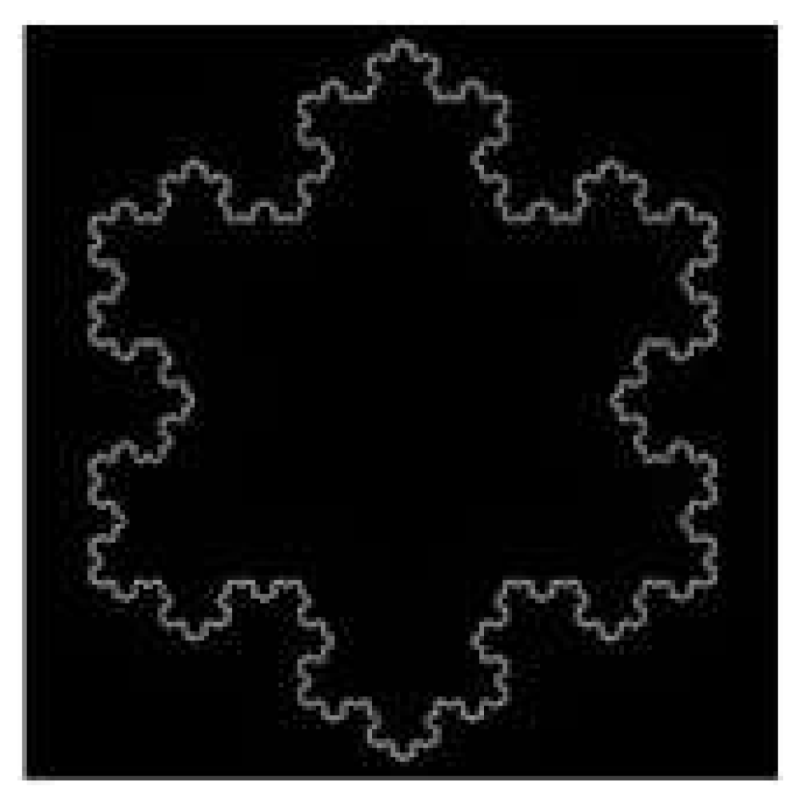

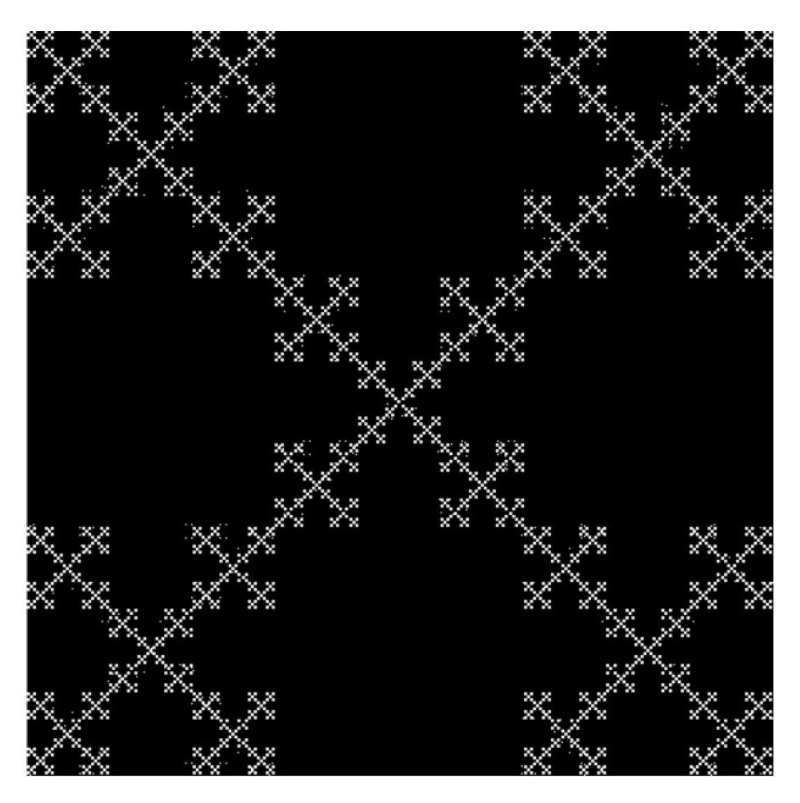

To verify the applicability of the BC algorithm, select common fractal geometries such as the Sierpinski triangle, DLA fractal, Koch fractal, Vicsek fractal, and Square to calculate their fractal dimensions, and compare them with theoretical values, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Common fractal geometries and BC algorithm verification.

As shown in Table 1, the errors between the values calculated by the BC algorithm and the theoretical values for various fractal geometries are all below 3%. Notably, the errors for the Sierpinski triangle, Koch fractal, Vicsek fractal, and Square are even smaller, all under 1%. These results demonstrate the high accuracy of the algorithm and confirm its feasibility for determining the 2D fractal dimension of PU grouting materials.

2.3. Box-Counting Method Based on Binary Image

2.3.1. Fractal Dimension Calculation

In the fractal analysis of porous media, 3D fractal properties are often investigated using 2D cross-sections. This method is based on the sectional dimension theorem, which states that the fractal dimension of a 2D section is one less than that of the 3D object [41,42], as shown in Equation (6).

where

and

represent the 2D and 3D fractal dimensions, respectively.

Equation (6) requires that the 3D medium has axial symmetry and is uniformly self-similar at all scales, with similar self-similar characteristics in different directions. In addition, the cross-sections in all directions have similar fractal characteristics. Apparently, the PU grouting material meets this requirement.

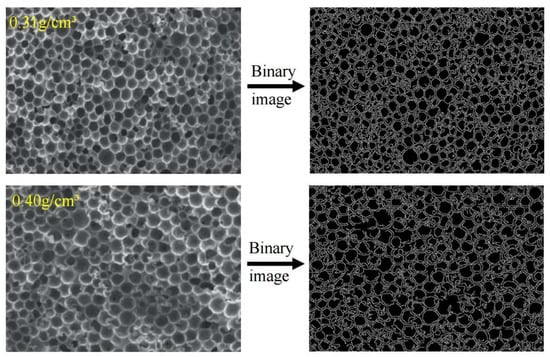

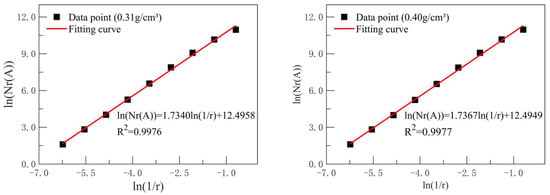

Due to the differences in the size, quantity, and regularity of the pores in PU grouting materials at different densities, it is necessary to explore the fractal dimensions of the materials at different densities. Since the density range of the PU grouting material specimens prepared in this paper is 0.29734 g/cm3 to 0.41817 g/cm3, SEM images [43] at densities of 0.31 g/cm3 and 0.4 g/cm3 were selected for 2D fractal dimension calculation and comparison. The binary image and the calculated fractal dimension are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively. The r values and the number of scales (Nr) used are listed in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Microscopic SEM images and binary images of PU grouting materials (17.4×).

Figure 5.

Calculation of the fractal dimension of PU grouting material.

Table 2.

The r values and the number of scales.

Table 2.

The r values and the number of scales.

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57,537 | 25,804 | 8765 | 2663 | 711 | 192 | 56 | 17 | 5 | |

| 57,898 | 25,925 | 8731 | 2630 | 690 | 188 | 54 | 17 | 5 |

From Figure 5, it can be observed that:

(1) The PU grouting materials with densities of 0.31 g/cm3 and 0.4 g/cm3 have 2D fractal dimensions of 1.7340 and 1.7367, respectively, with coefficients of determination above 0.99. This indicates that within the density range of 0.29734 g/cm3 to 0.41817 g/cm3, the influence of density variation on the fractal dimension is minimal. Therefore, the average value is taken to represent the 2D fractal dimension within this density range, which is 1.7355. Based on Equation (6), the 3D fractal dimension of the PU grouting material is 2.7355.

(2) The fractal dimension increases slightly with the increase in density. This is because during the process of density increase, the volume of the pores decreases and the number of pores increases, making the microstructure more complex, which leads to a small increase in the fractal dimension.

2.3.2. Fractal Dimension Verification

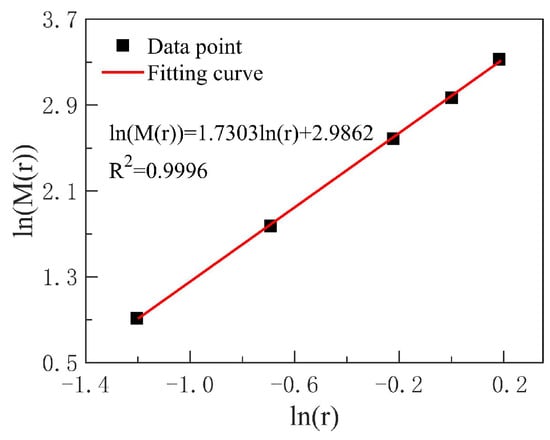

To further validate the accuracy of the fractal dimension, it was calculated using the metric relationship and then compared with that obtained from the box-counting method, taking the sample with a density of 0.31 g/cm3 as a case study.

The number of pores () in the PU grouting material is related to the measurement scale () as follows:

There exists a proportional constant

such that:

Take the logarithm on both sides:

According to Equation (9), the fractal dimension is the slope value. The number of pores in the SEM images of the PU grouting material was calculated at scales of 0.3 mm, 0.5 mm, 0.8 mm, 1 mm, and 1.2 mm. The logarithms of each scale and the corresponding pore count were taken, and the least squares method was used for fitting, as shown in Figure 6. The resulting 2D fractal dimension is 1.7303, which is slightly different from the result calculated by the Box-counting method, indicating that the calculated value for the PU grouting material is highly reliable.

Figure 6.

Double logarithmic fitting of the number of pores under different measurement scales.

3. Dielectric Model of Polyurethane Grouting Material Based on Fractal Geometry

3.1. Series-Parallel Dielectric Model

Various dielectric models have been proposed for the study of multiphase materials, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Traditional dielectric models.

Among them, the Li Jianhao model, Maxwell-Garnett model, and Rayleigh model predict the dielectric constant of mixtures through the volume fraction and dielectric constant of each phase. The Series-parallel model connects multiphase media in series or parallel to form a series or parallel structure.

In the analysis of dielectric properties of the PU grouting material, predictions from the series model alone tend to underestimate the effective dielectric constant, whereas those from the parallel model alone tend to overestimate it. This indicates that the dielectric constant of the PU grouting material falls within the prediction range of the series and parallel models [6]. Therefore, to better analyze the dielectric characteristics of PU grouting materials, both series and parallel structures must be considered simultaneously.

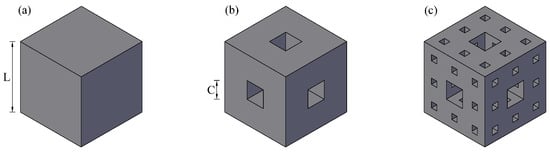

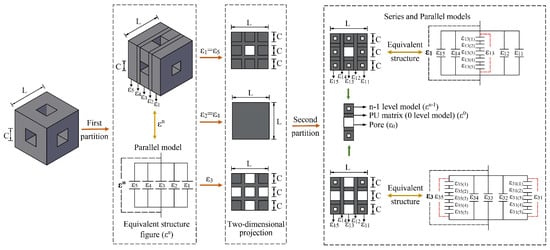

3.2. Menger Sponge Fractal Model

To analyze the dielectric constant of PU grouting materials, the Menger sponge fractal concept is introduced to predict the dielectric properties of the materials. The Menger sponge is a classic fractal model composed of a series of nested cubes. The construction begins by removing smaller cubes from the center and the center of each of the six faces of the initial cube. This process is then repeated iteratively to create higher-order fractal structures, as shown in Figure 7. In the figure, the shaded part represents the continuous PU matrix, and the hollowed-out part represents the closed pores inside the continuous matrix.

is the side length of the cube, and

is the cut-out size.

Figure 7.

Menger sponge model. (a) Zero-stage model; (b) one-stage model; (c) two-stage model.

As shown in Figure 7, the one-stage Menger sponge model involves hollowing out a smaller cube with a side length of

from the center of each of the six faces and the volume center of a cube with a side length of

. The hollowed-out volume is

, and the remaining volume is

. According to the iterative relationship, the hollowed-out volume and remaining volume of the n-stage Menger sponge model are given by Equations (10) and (11).

The volume fractal dimension is:

The ratio of the volume removed from the model to the original total volume is the porosity. For the n-stage model, its porosity is:

During the iterative process of the Menger sponge model, it is required that

to satisfy subsequent iterations. However, due to the high porosity of the PU injection molding material, which is composed of closed pores and a continuous matrix, and the fact that each pore exists independently [44], the use of the Menger sponge model to simulate the micro-porous structure of the material requires

. In addition, as shown in Equation (12), when the fractal dimension is determined, there is a certain relationship between

and

.

3.3. n-Stage Dielectric Model Construction

To construct a fractal dielectric model based on the Menger sponge fractal concept, the one-stage PU grouting material microscopic unit is initially divided into five parallel columns. Each of these columns is further subdivided into five parallel sub-columns, forming a parallel structure. Subsequently, each sub-column is partitioned into five rows, establishing a series structure within each column. Finally, a series-parallel dielectric model is applied to analyze its dielectric properties, thereby constructing an n-stage dielectric model. The model construction process is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Establishment process of the dielectric model for n-stage PU grouting material.

Based on the equivalent structure diagram of

, the total dielectric constant of the n-stage fractal model can be derived by applying the parallel dielectric model.

where

represents the total dielectric constant of the n-stage fractal model;

and

represent the dielectric constant and volume fraction of the

-th row, respectively;

,

,

and

,

,

is the dielectric constant value for the 0-stage model, that is, the dielectric constant value of the matrix.

3.3.1. ε1 and ε3 Calculation

In the equivalent structure diagram of

,

,

,

,

,

represent the dielectric constants of the first to fifth column models after the second division, belonging to a parallel structure.

,

,

,

,

represent the dielectric constants of the first to fifth rows in the second column, respectively, which is a series structure.

As shown in the equivalent structure diagram,

,

. According to the Series dielectric model, it can be obtained that:

where

,

;

.

For

,

,

. Based on the Series model, Equation (16) is derived.

where

,

,

,

.

Similarly, it can be shown that:

where

,

,

,

represents the dielectric constant value of air;

,

.

Substituting Equations (16) and (17) into Equation (15) yields:

where

.

Similarly, it can be shown that:

3.3.2. n-Stage Dielectric Model

Substituting Equations (18) and (19) into Equation (14), the calculation model of the dielectric constant for n-stage PU grouting material is obtained.

According to Equation (20), the unknown parameters in the model are

and

, and

. Once the values of

and

are determined, the dielectric model of n-stage PU grouting material can be established. To initially verify the accuracy of the model, consider two extreme scenarios where PU grouting material is entirely in the matrix or pores.

(1) When the material consists entirely of the matrix, the model is a zero-stage model (n = 0). At this time,

,

, that is, the dielectric constant of the model is the dielectric constant of the matrix, which is consistent with the actual situation.

(2) When the material consists entirely of the pores,

. At this time,

, and the dielectric constant of the model is the dielectric constant of air, which is consistent with the actual situation.

Therefore, the fractal dielectric model exhibits a certain degree of accuracy.

4. Model Parameter Calculation and Model Validation

4.1. Dielectric Property Testing

Dielectric property tests were conducted to determine the model parameters and validate the model’s accuracy.

4.1.1. Raw Materials

The raw materials used in the preparation of PU grouting material specimens include polyether polyols, isocyanates, foaming agents, catalysts, and various other additives that play auxiliary roles. These materials are divided into two components, A and B. Component A consists of polyether polyol (designated as 330N) and a curing agent, while Component B is composed of isocyanate (designated as PM200) and other additives. The main physical parameters of the polyether polyol and isocyanate are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Physical parameters of polyether polyol and isocyanate.

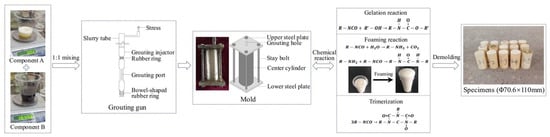

4.1.2. Specimen Fabrication

The specimen fabrication process is shown in Figure 9. To facilitate demolding, a layer of grease is applied to the inner wall of the mold before casting. During specimen fabrication, the two-component PU raw material is mixed in a 1:1 ratio, rapidly stirred, and injected into the pre-fabricated mold using a grouting gun. By controlling the grouting volume, 40 PU specimens with different densities are obtained. After casting, the specimens are allowed to stand for 1.5 to 2 h. Demolding is performed once the material has fully reacted and cooled to room temperature. Uneven or damaged parts are then trimmed. The final specimens are cylindrical with a diameter of 70.6 mm and a height of 110 mm, and the density range is 0.29734 g/cm3 to 0.41817 g/cm3. The dimensional error for each specimen is within 0.1 mm.

Figure 9.

Fabrication of PU specimens [45,46].

4.1.3. Experimental Methods and Equipment

The experiments were conducted in accordance with the standard specifications: Method for Determination of Dimensional Stability of Rigid Foam Plastics (GB/T 8811-2008) [47] and Determination of Apparent Density of Foam Plastics and Rubber (GB/T 6343-2009) [48].

The measurements were conducted using the coaxial probe method with an Agilent E5071C vector network analyzer (VNA) equipped with an open-ended coaxial probe. To ensure measurement accuracy, air calibration, short-circuit calibration, and pure water calibration must be performed prior to measurement.

During the experiment, an automated frequency sweep was performed over the 500 MHz to 6000 MHz range, with measurements taken at 111 discrete frequency points. To minimize measurement errors, attention should be paid to the following two points:

(1) To ensure high conformity between the probe and the specimen, the test surface should be selected to be flat and free of holes or bubbles.

(2) Select ten measurement points on the measurement plane. After discarding the highest and lowest values, calculate the average of the remaining values. This average is taken as the dielectric constant of the specimen.

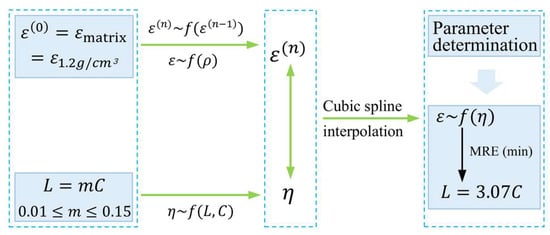

4.2. Model Parameter Determination

PU grouting material is a porous material composed of a matrix and cells. At a density of 1.2 g/cm3, the material can be considered to consist entirely of the matrix, corresponding to a zero-stage model. In this case, its dielectric constant is equivalent to that of the matrix. The calculation can be performed by fitting the relationship between dielectric constant and density, as described in reference [49] and given by Equation (21). The raw materials and components of the specimens used in the reference are identical to those used in this paper.

According to Equation (20), the unknown parameters are

and

, with the constraint

. To determine these parameters, an investigation was conducted using the parametric relationship:

, where

was varied from 0.01 to 0.15 in increments of 0.01. The parameter determination process is illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Flowchart for determining parameter relationships.

(1) The dielectric constant value of the zero-stage model is predicted by Equation (21).

(2) Using the zero-stage model, the dielectric constant values of the remaining multi-stage models are iteratively obtained through Equation (20), and the porosity of the corresponding stage models is calculated according to Equation (13).

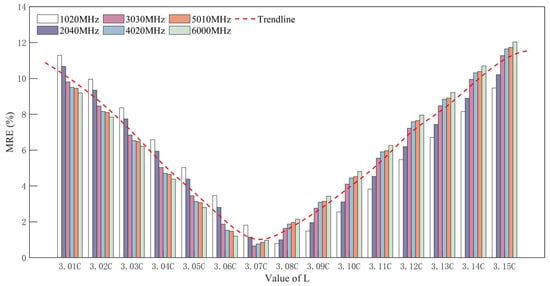

(3) Due to the fact that the order of an n-stage model is an integer, the prediction of the effective dielectric constant is discrete. Furthermore, each fractal model corresponds to a single density point and cannot represent a continuous density range. Therefore, it is necessary to establish continuous functions between these models to characterize PU grouting materials of arbitrary densities, referred to as “non-integer” fractal stages. Therefore, cubic spline interpolation is employed to fit the data, thereby obtaining a continuous function between the effective dielectric constant and porosity. The MRE between the predicted and measured values under different relationships between

and

is shown in Figure 11. The relationship between

and

is selected when the MRE is relatively small.

Figure 11.

MRE under different relationships between

and

.

According to literature [43], there is a significant linear relationship between the porosity of PU grouting material and its density:

Based on Equation (22), the density of the specimen is converted into the corresponding porosity. Combined with the dielectric property test data, the MRE between the predicted and measured values of the dielectric model established in this paper at various typical frequencies is shown in Figure 11.

As shown in Figure 11, the proposed model has a small error when L = 3.07C. According to Equation (12),

and

, substitute them into Equation (20), and derive the final dielectric model, as shown in Equation (23).

4.3. Model Validation

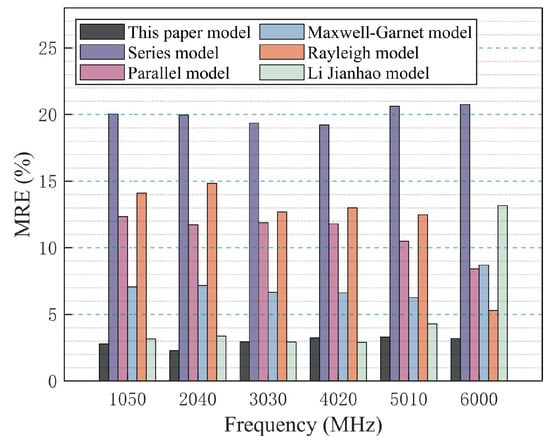

Compare the model built in this paper with the Series model, Parallel model, Li Jianhao model, Maxwell–Garnett model, and Rayleigh model. The MRE between the predicted values of each model and the measured values is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

MRE of each model.

From Figure 12, it can be seen that the MRE of the model established in this paper is the smallest compared to other models, within 4%. Traditional dielectric models are primarily constructed based on the volume fractions of the phases in multiphase materials, often neglecting the pore structural characteristics of high-porosity materials. In contrast, the Series-parallel dielectric model accounts for the connectivity of the material skeleton by regarding it as a combination of series and parallel structures, which aligns well with the Menger sponge fractal. By integrating the series-parallel dielectric model with the Menger sponge fractal, this paper constructs a multi-stage structure capable of describing the dielectric properties of materials with complex pore structures. This approach bridges the microstructure and the macroscopic dielectric constant, effectively reflecting the material’s dielectric properties. Therefore, the model established in this paper is more suitable for PU grouting materials with complex pore structures.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a dielectric model for PU grouting material was developed using the Menger sponge fractal concept to predict the correlation between porosity and dielectric constant. The model was subsequently validated by experimental tests. The primary findings are summarized below:

(1) The 3D fractal dimension of the PU grouting material was found to be approximately 2.7355 within the density range of 0.29734~0.41817 g/cm3. Employing the box-counting method on a Python 3.10 platform, the fractal dimensions at densities of 0.31 g/cm3 and 0.40 g/cm3 were determined to be 1.7340 and 1.7367, respectively, which are close to the value of 1.7303 derived from the measure relationship. Ultimately, the 3D fractal dimension of the PU grouting material was calculated via the sectional dimension theorem.

(2) A fractal dielectric model for an n-stage PU grouting material was established, and its discrete predictions were subsequently fitted using cubic spline interpolation. The model’s results converge to the dielectric constants of the matrix and air as the porosity approaches 0 and 1, respectively, which is consistent with physical reality.

(3) The dielectric constant of the specimens was predicted using a continuous function of porosity, which was established through cubic spline interpolation. The predictions were then compared with the measured values. The model parameters

and

were determined when the MRE was minimized. In comparison with conventional dielectric models and validated against experimental data, the proposed model achieves an MRE of less than 4%, demonstrating its high accuracy.

This study analyzed the fractal characteristics of PU grouting materials. However, the density range of the prepared specimens was limited. For high-density PU grouting materials, the increased density results in a higher proportion of the polymer matrix and a smaller volume fraction of pores. This alteration in microstructure leads to a deviation in prediction accuracy. Furthermore, the material was treated as a solid–gas two-phase system, neglecting the liquid phase.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.M.; software, S.S.; investigation, M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; supervision, M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51608197) and Key Research Projects of Henan Higher Education Institutions (No. 23B570001) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51679091).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because it will be used in subsequent research. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PU | polyurethane |

| MRE | mean relative error |

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

References

- Thovert, J.F.; Wary, F.; Adler, P.M. Thermal conductivity of random media and regular fractals. J. Appl. Phys. 1990, 68, 3872–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.M. Transports in fractal porous media. J. Hydrol. 1996, 187, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yu, B.; Hu, Y.; Cai, J.; Feng, Y.; Xu, P. A self-similarity model for dielectric constant of porous ultra low-k dielectrics. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2007, 40, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedus, L.L.; Pereira, C.J. Reaction engineering for catalyst design. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1990, 45, 2027–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.H.; Katz, A.J.; Krohn, C.E. The microgeometry and transport properties of sedimentary rock. Adv. Phys. 1987, 36, 625–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. Studies on the Microstructure and Its Impact on Electrical and Thermal Properties of Porous Low-K Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krohn, C.; Thompson, A. Fractal sandstone pores: Automated measurements using scanning-electron-microscope images. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 33, 6366–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gong, Y.; Wao, D.; Sun, Y.; Hong, X.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Z. Fractal characteristics of mesoporous silica. Nucl. Tech. 2004, 1, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Dai, J.; Song, X.; Sun, Z. Multi-fractal spectra of TEM images of MoO3nanofibres. J. Funct. Mater. 2008, 6, 1056–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.; Yang, Y.; Ju, Y.; Mao, L.; Yang, Y. Computation of fractal dimension of rock pores based on gray CT images. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 3346–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. Preparation and Properties of Superhydrophobic Wood Based on Fractal Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, N.; Díaz, M.C.; Saa, A.; Tarquis, A.M. Fractal and multifractal analysis of pore-scale images of soil. J. Hydrol. 2006, 322, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ostadhassan, M. Multi-scale fractal analysis of pores in shale rocks. J. Appl. Geophys. 2017, 140, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesquet-Popescu, B.; Vehel, J.L. Stochastic fractal models for image processing. Signal Process. Mag. IEEE 2011, 19, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y. Mechanical properties and pore structure research of geopolymer cold-bonded lightweight aggregate concrete using fractal theory. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2025, 42, 5122–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, E.; Rieu, M.; Sposito, G.; De Marsily, G. Models of the water retention curve for soils with a fractal pore size distribution. Water Resour. Res. 1996, 32, 3025–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Pitchumani, R. Fractal Model for Wettability of Rough Surfaces. Langmuir 2017, 33, 7181–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatte, S.; Pitchumani, R. Fractal Model for Drag Reduction on Multiscale Nonwetting Rough Surfaces. Langmuir 2020, 36, 14386–14402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Pengda, Z. Theoretical study of statistical fractal model with applications to mineral resource prediction. Comput. Geoences 2002, 32, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-Z. A fractal model for gas permeation through porous membranes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2008, 51, 5288–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, R. Evaluation of soil water retention curve with the pore–solid fractal model. Geoderma 2005, 127, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, X.; Tian, W.; Xu, F.; Shou, D. A fractal model of effective mechanical properties of porous composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 213, 108957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pia, G.; Sanna, U. A geometrical fractal model for the porosity and thermal conductivity of insulating concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzeni, C.; Pia, G.; Sanna, U.; Spanu, N. A fractal model of the porous microstructure of earth-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1607–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitchumani, R.; Yao, S.C. Correlation of Thermal Conductivities of Unidirectional Fibrous Composites Using Local Fractal Techniques. J. Heat Transf. 1991, 113, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitchumani, R. Evaluation of Thermal Conductivities of Disordered Composite Media Using a Fractal Model. J. Heat Transf. 1999, 121, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jin, F.; Shi, M.; Yang, H. Heat Conduction in Fractal Porous Madia. J. Appl. Sci. 2003, 3, 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, H.; Shi, M. Important problems of fractal model in porous media. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2002, 5, 692–697. [Google Scholar]

- Rayleigh, L. On the influence of obstacles arranged in rectangular order upon the properties of a medium. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1892, 34, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, P.; Chatterjee, I. Dielectric Mixture Model for Asphalt-Aggregate Mixitures. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Energy 1993, 28, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, J.C.M. Colours in Metal Glasses and in Metallic Films. Proc. R. Soc. Lond 1904, 73, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, V.L.; Dobson, M.C.; Kaupp, V.H.; Komarov, S.A.; Kleshchenko, V.N. Generalized refractive mixing dielectric model for moist soils. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2004, 42, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, F.; Zhong, Y.; Li, X. Composite Dielectric Model of Asphalt Mixtures Considering Mineral Aggregate Gradation. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 04019091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, J. Road surface material dielectric constant non-uniform model radar electromagnetic wave simulation. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. 2009, 49, 571–575. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Dong, Z.; Xue, B.; Lei, J. Analysis of Ground Penetrating Radar Wave Field Characteristics of Dam Face Disengaging Repaired by Polymer Grouting. J. Zhengzhou Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2024, 45, 1–6+13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Liu, K.; Du, X.; Wang, F. Experiment and numerical simulation of water plugging law of permeable polymer in the water-rich sand layer. Sci. Sin. Technol. 2023, 53, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Pan, W.; Fang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Du, M. Research Progress of the Cell Structure Characteristics and Compressive Properties of Polyurethane Foam Grouting Rehabilitation Materials. Mater. Rep. 2024, 38, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y. Inverse Analysis of Dielectric Properties of Layered Structuresand the Applications in Engineering. Ph.D.Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. The Multiclass Inverse Analysis of the Multiphase VolumeRatio of Asphalt Mixtures Based on Dielectric Modelingand Its Engineering Applications. Ph.D.Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Ji, C. Fractal Theory and Its Applications; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, M.C.; Sammis, C.G.; Sahimi, M.; Martin, A.J. Fractal analysis of 3D spatial distributions of earthquakes with a percolation interpretation. J. Geophys. Res. 1995, 100, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.R.; Lin, H.; Bruns, M.A. A comparison of fractal analytical methods on 2- and 3-dimensional computed tomographic scans of soil aggregates. Geoderma 2006, 134, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C.; Fang, H.; Deng, Y. Quantitative analysis of the representative volume element of polymer grouting materials based on geometric homogenization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300, 124223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.L.; Zhao, X.; Yao, J.H.; Yang, M.L. Polymer Strength Prediction Model Based on Dielectric Constant. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2025, 2025, 7762703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Research on Anchoring Characters of Non-Water Reacted Polymer Grouting Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Su, Y.; Du, X.; Wang, F.; Li, B. Experimental and Numerical Investigation on Repairing Effect of Polymer Grouting for Settlement of High-Speed Railway Unballasted Track. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 8811-2008; Rigid Cellular Plastics—Test Method for Dimensional Stability. National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 6343-2009; Cellular Plastics and Rubbers—Determination of Apparent Density. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Meng, M.; Chen, Z. Construction of Dielectric Model of Nonaqueous Reactive Polyurethane Grouting Materials. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2022, 2022, 1398724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.