Abstract

On GPU-based clusters, the training workloads of machine learning (ML) models, particularly neural networks (NNs), are often structured as Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) and typically deployed for parallel execution across heterogeneous GPU resources. Efficient scheduling of these workloads is crucial for optimizing performance metrics such as execution time, under various constraints including GPU heterogeneity, network capacity, and data dependencies. DAG-structured ML workload scheduling could be modeled as a Nonlinear Integer Program (NIP) problem, and is shown to be NP-complete. By leveraging a positive correlation between Scheduling Plan Distance (SPD) and Finish Time Gap (FTG) identified through an empirical study, we propose to develop a Running Time Gap Strategy for scheduling based on Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) and Reinforcement Learning, referred to as WORL-RTGS. The proposed method integrates the global search capabilities of WOA with the adaptive decision-making of Double Deep Q-Networks (DDQN). Particularly, we derive a novel function to generate effective scheduling plans using DDQN, enhancing adaptability to complex DAG structures. Comprehensive evaluations on practical ML workload traces collected from Alibaba on simulated GPU-enabled platforms demonstrate that WORL-RTGS significantly improves WOA’s stability for DAG-structured ML workload scheduling and reduces completion time by up to 66.56% compared with five state-of-the-art scheduling algorithms.

1. Introduction

On GPU-based clusters for machine learning (ML) training, a significant portion of resources is dedicated to long-running workloads, often modeled as Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) [1,2]. These workloads, prevalent in large-scale ML applications such as Deep Neural Network (DNN) training, consist of tasks with complex dependencies, managed by resource orchestration frameworks such as Kubernetes [3], Apache Hadoop YARN [4], or Apache Mesos [5]. The nodes in a DAG represent tasks, while the edges denote data dependencies, making efficient scheduling critical for optimizing performance metrics such as execution time. Despite extensive efforts, scheduling DAG-structured ML tasks in GPU environments remains challenging due to the trade-offs between data transfer overheads in distributed schedules and task waiting times in centralized ones.

Deploying ML workloads on a GPU cluster faces unique scheduling difficulties, particularly when relying on heuristic rules or ML-driven decision-making. Reinforcement Learning (RL) approaches, including Deep Q-Networks (DDQN) [6], attempt to discover effective policies by capturing task dependencies and the dynamics of resource availability. However, these methods face drawbacks such as expensive training costs, large data requirements, and poor adaptability when applied to heterogeneous GPU platforms or varied DAG topologies. Whereas heuristic-based strategies such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [7] offer computationally lightweight solutions, they frequently stagnate in non-optimal states or perform poorly in discrete and high-dimensional DAG scheduling, where conventional distance measures fail to represent plan similarity effectively.

In our previous research [8], we modeled the scheduling of DAG-structured workloads as a Nonlinear Programming (NLP) problem, termed as Long-Running Workload Task Scheduling (LRW-TS), and proved its NP-completeness. We identified a positive correlation between Scheduling Plan Distance (SPD) and Finish Time Gap (FTG), and by leveraging this finding, we designed RTGS, a hybrid approach combining WOA with a Greedy strategy. Our work in this paper extends that foundation to GPU-based ML training, replacing the Greedy algorithm with a Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) to establish a novel scheduling solution, referred to as WORL-RTGS. By exploiting the SPD-FTG correlation, we redefine Scheduling Plan Distances, enabling WOA to effectively handle complex DAG dependencies in heterogeneous GPU environments. The WORL-RTGS integration mitigates the limitations of standalone RL (e.g., slow convergence) and traditional heuristics (e.g., local optima traps), achieving superior makespan and resource utilization. Key challenges addressed include

- Measuring Scheduling Plan Distances: We use FTG as a proxy for distance, converting it to SPD via the identified correlation.

- Generating controlled scheduling plans: DDQN dynamically generates plans with precise distances, improving over the rigidity of a Greedy approach.

Empirical evaluations using real-world ML workload traces from Alibaba in simulated GPU environments demonstrate that WORL-RTGS reduces completion time by up to 66.56% compared with state-of-the-art baselines. The proposed approach excels on heterogeneous GPU clusters, adapting to diverse DAG structures and resource constraints while maintaining stability. Our key contributions are summarized as follows:

- Formulate the Neural Network with Hybrid Parallel (N2HP) scheduling problem and prove its NP-completeness.

- Leverage the SPD-FTG correlation to redefine Scheduling Plan Distances for GPU-based ML tasks.

- Design WORL-RTGS, a hybrid scheduler combining WOA’s global search with DDQN’s adaptive decision-making, outperforming traditional heuristics and RL methods.

- Introduce a generalizable framework for DAG-structured ML task scheduling, opening new research directions.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 surveys related work, highlighting limitations of swarm intelligence for task scheduling. Section 3 formulates the N2HP problem and analyzes its complexity. Section 4 details the design of the WORL-RTGS algorithm, leveraging the SPD-FTG correlation. Section 5 evaluates performance against baselines. Section 6 concludes our work and sketches future efforts.

2. Related Work

Recent advancements in intelligent task scheduling for cloud computing and deep learning (DL) environments address resource optimization and quality of service (QoS). In three-tier cloud marketplaces, SaaS providers aim to minimize VM leasing costs while ensuring QoS for dynamic workloads. A two-layer DQN-based framework integrates QoS-aware task assignment with elastic VM auto-scaling, improving resource utilization and reducing costs [9]. For DAG-structured workloads in heterogeneous real-time systems, novel node-priority assignment strategies leveraging global DAG structures achieve up to 14.35% makespan improvement over baselines [10].

In GPU-based distributed DL training, Chronus [11] supports deadline-constrained and best-effort jobs by exploiting DL workload characteristics like predictability and preemptibility, enhancing SLO satisfaction and completion time. Datacenter-level analysis, such as SenseTime’s trace study, informs quasi-shortest-service-first policies and energy-saving managers, boosting cluster utilization and reducing latency [12]. For hybrid clouds, DRL-based VM selection optimizes execution cost and QoS under fluctuating workloads [13].

For safety-critical tasks on many-core platforms, DAG-Order [14] uses non-preemptive scheduling on SLT NoC architectures, ensuring safe response times and outperforming state-of-the-art methods. Multi-core systems face multi-DAG interference, addressed by improved scheduling schemes that model core allocation constraints, enhancing schedulability [15]. In DNN training, DAPPLE [16] combines data and pipeline parallelism with intelligent scheduling, improving throughput and memory efficiency over GPipe and PipeDream.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) schedulers show promise in dynamic environments. The A2C Scheduler [17] reduces gradient estimation variance, outperforming policy gradient methods. DRL-based edge computing solutions using DQNs adaptively schedule workloads, improving service time and task success rates [18]. For GPU datacenters, DL2 [19] integrates supervised and RL to reduce job completion times, while a survey [20] categorizes DL workload characteristics and future scheduling directions.

Large-scale Transformer models benefit from TeraPipe’s token-level pipeline parallelism, reducing training time via dynamic programming [21]. PipePar [22] enhances load balancing on heterogeneous GPU clusters by considering performance diversity and bandwidth. DRL-based schedulers handle dynamic resource demands, with workload clustering to improve scalability [23] and Spark cluster scheduling to optimize cost and performance [24].

Multi-objective optimization in cloud scheduling, such as Pareto-efficient schedulers, minimizes makespan and communication costs [25]. MORL-WS [26] uses multi-objective RL for workflow scheduling, improving makespan and energy efficiency. Systems like Liquid [27] and Horus [28] enhance GPU resource sharing by addressing interference, improving job completion times and utilization.

In High-Performance Computing (HPC), DRAS [29] employs hierarchical DRL scheduling, outperforming heuristics by up to 50% on real workloads. Hierarchical partitioning for GPU co-scheduling achieves 1.87× throughput improvement [30]. Multi-agent RL frameworks [31] and mDRL [32] reduce job completion time and power consumption on large-scale GPU clusters. DeepShare [33] mitigates network contention, cutting job completion times by up to 20.7%.

These studies highlight the trend toward hybrid, learning-based, and system-aware scheduling, leveraging RL and workload characteristics to optimize performance across diverse computing platforms. Our work proposes a novel scheduling approach, WORL-RTGS, to deal with complex task dependencies in heterogeneous cloud environments by integrating the WOA algorithm with the DDQN algorithm. A key discovery is the positive correlation between two critical variables, enabling variable transformation to adapt WOA for efficiently handling intricate task scheduling with strict dependencies. This hybrid WORL-RTGS method overcomes limitations of traditional heuristic algorithms, such as local optima traps, and standalone RL approaches, which often suffer from high computational overhead and slow convergence. The synergy of WOA’s global search capability and DDQN’s adaptive decision-making ensures robust performance, achieving superior makespan and resource utilization compared with existing methods.

3. Problem Formulation

3.1. Cost Model for Neural Network Training with Hybrid Parallelism

The distribution of neural network training across multiple GPUs and servers depends on the adopted parallelization strategy. In distributed parallel processing systems, three main types of parallelism are commonly employed as follows: data parallelism, model parallelism, pipeline parallelism, and hybrid parallelism, as briefly described below.

- Data Parallelism: The entire neural network model is replicated on each GPU/server. Different subsets of data are distributed to each GPU. After each forward and backward pass, gradients from all GPUs are averaged (or summed) across the devices (e.g., via AllReduce [34]) before updating the model. This parallelism is considered when the model fits in a single GPU’s memory, but training data is large.

- Model Parallelism: The model is split spatially by layers or by tensor dimensions across multiple GPUs. The splitting method is usually structure-agnostic or based on tensor shapes or layer sizes, not the functional purpose of model components. Forward/backward pass is conducted sequentially across GPUs. The purpose of this parallelism is to train a large model that does not fit in a single GPU.

- Pipeline Parallelism: This parallelism divides the model into stages, and each GPU handles a stage. Splitting into stages is conducted intentionally, with functional awareness (e.g., grouping layers that form logical blocks or stages of computation). To improve GPU utilization, the input mini-batch of training samples is divided into smaller micro-batches, which are fed into the pipeline in a staggered fashion, allowing different micro-batches to flow through different GPUs concurrently. Pipeline parallelism is useful when training large models that do not fit in a single GPU but also require efficient hardware usage.

- Hybrid Parallelism: A hybrid approach combines two or more parallelization strategies: data parallelism, model parallelism, and pipeline parallelism, to efficiently train large-scale models on multi-GPU and multi-server systems. It is used when no single type of parallelism is sufficient alone, especially for very large neural networks such as GPT-3 [35] or GPT-4 [36] that far exceed the memory and compute capacity of a single GPU.

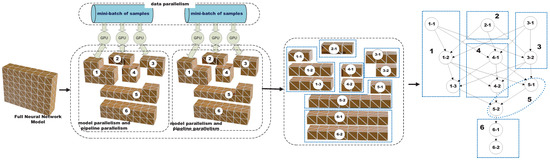

We define the cost model to support the scheduling of neural network (NN) training workloads on multi-GPU, multi-server platforms using hybrid parallelism, which combines data parallelism, model parallelism, and pipeline parallelism. A computational unit represents either a complete layer, a partitioned sublayer due to model parallelism, or a group of layers or sublayers forming a pipeline stage. Note that a computational unit may contain neurons from multiple layers. We represent each layer within a computational unit as a single node, as shown in Figure 1. The nodes belonging to the same computational unit should be scheduled onto the same GPU for processing. A neural network training job is modeled as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) , where is the set of n nodes, defines the forward/backward computational dependencies between nodes, is the computational workload, e.g., in unit of FLoating point OPerations (FLOPs) [37], for the n nodes, represents the GPU memory requirement of each node, and is the size of the data such as activations or gradients transferred between dependent nodes. Let denote the set of computational units. Each unit consists of a subset of nodes that must be co-located on the same GPU. The exact granularity of each and depends on the adopted parallelization strategy. Figure 1 illustrates an example of a neural network training job that incorporates data parallelism, model parallelism, and pipeline parallelism, respectively.

Figure 1.

An example of a neural network training job with data parallelism, model parallelism, and pipeline parallelism.

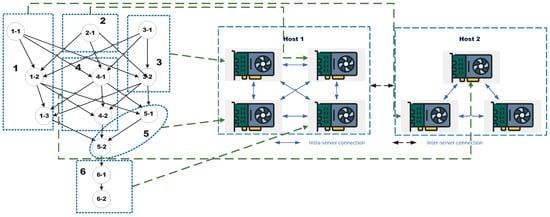

We model the training platform as a GPU cluster , where denotes the set of m available GPUs across all servers on the training platform, denotes the set of k servers, denotes the set of interconnections between GPUs, denotes the set of computational capabilities of each GPU, e.g., in unit of Tera FLoating point OPerations Per Second (TFLOPS) [38], and denotes the bandwidth between two connected GPUs and . We define a function that maps each GPU to a server and a mapping function that assigns each node to a GPU for execution. For any pair of nodes that belong to the same computational unit, we enforce . For each pair , if , the interconnection is classified as intra-server; otherwise, if , it is classified as inter-server. The value of depends on the type of interconnect. If and are on the same server and connected via NVLink, then reflects the NVLink bandwidth (e.g., 50–600 GB/s depending on hardware generation). If and reside on different servers, then represents the inter-server communication bandwidth, typically provided by Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) technologies or high-speed Ethernet. Figure 2 illustrates a GPU cluster consisting of two servers, along with an example of computational unit allocation.

Figure 2.

A GPU cluster with two servers and an example of computational unit allocation.

The total training time for a mini-batch depends on the following factors:

- Node Execution Time: Each node has an execution time dependent on its computational workload and the GPU capability of the assigned GPU .

- Data Transfer Time: For two dependent nodes , if they are placed on different GPUs and , the data transfer time is governed by and bandwidth between and .

- Stall Time: In both pipeline and model parallelism, adjacent stages or model partitions may experience stall time due to imbalances in execution time across stages or model parts.

- Synchronization Time: In data parallelism, all GPUs must synchronize gradients at the end of each backward pass, hence introducing communication overheads.

The optimization goal is to minimize hybrid parallel training cost for one iteration (mini-batch) by scheduling computational units to GPUs in a way that balances workloads, minimizes inter-GPU communication, and avoids stall time caused by pipeline and model parallelism.

3.2. Formulation of the Scheduling Problem for NN Training

We investigate how a DAG-structured neural network training task executes, formulate the scheduling problem as a nonlinear integer programming model, and prove its NP-completeness.

A node is considered as an entry node if it has no predecessors, i.e., there is no with . For such a node, the earliest start time is 0; otherwise, is determined by the maximum arriving time () among all data produced by its immediate predecessors:

Equation (1) defines the earliest start time of node l. If l is an entry node with no predecessors, then , meaning that it can start execution immediately without waiting for any input; otherwise, depends on the latest arrival time of data produced by all its immediate predecessor nodes , using the maximum to ensure that l can begin to execute only after all dependency data are ready, thereby enforcing the topological order constraints in the DAG.

The data arrival time from a predecessor node is given by the actual finish time plus the transmission delay required to transfer results from the GPU executing to the GPU assigned to its successor :

Equation (2) computes the data arrival time from predecessor node to successor node , which equals the actual finish time of plus the cross-GPU data transmission delay . This equation captures the direct impact of communication overhead on task start time, particularly in model parallelism or pipeline parallelism scenarios, where significant delay may occur if and are on different GPUs, potentially postponing the execution of .

The data transmission time from the GPU running node to the GPU running node is calculated as

where represents the volume of data transferred from predecessor to successor , denotes the bandwidth between the GPUs executing and , and specifies the GPU assigned to node . Equation (3) provides the precise calculation of data transmission time : the data volume , such as activations or gradients, divided by the actual bandwidth between the GPUs executing and . This formula highlights the strong correlation between communication cost and scheduling mapping: if two nodes are mapped to the same GPU, (theoretically no transmission delay); if across servers, b is small, leading to large delays, and hence incentivizing the scheduler to prioritize placing strongly dependent nodes on high-bandwidth links.

If GPU g has sufficient Available Resources () to run node l at its earliest start time , then the actual start time is ; otherwise, the execution of l is delayed until GPU g provides Sufficient Resources (). The value of is calculated as

where represents the memory available on GPU g at time . Equation (4) determines the actual start time of node l, considering the dynamic availability of GPU memory resources. If, at the earliest possible start time , the available memory on the target GPU g exceeds the memory required by node l (), then no delay is needed and execution starts immediately; otherwise, it must be postponed until the time when the GPU releases sufficient memory. This mechanism prevents memory over-allocation and simulates execution blocking due to insufficient GPU memory in real training scenarios.

We determine for GPU g at a given time point as

where denotes the occupied memory on GPU g at . Equation (5) straightforwardly defines the available memory on GPU g at any time : total memory capacity minus the currently occupied memory . This expression serves as the foundation for subsequent memory scheduling decisions, ensuring that tasks exceeding remaining memory are not assigned to the GPU, avoiding runtime Out-of-Memory (OOM) errors.

The value of is calculated as

where is the memory required for node l, and is 1 if node l is assigned to GPU g, and 0, otherwise. Meanwhile, indicates the earliest time when GPU g has sufficient resources to execute node l. Equation (6) accurately accounts for the used memory on GPU g at time : for all nodes l assigned to this GPU (marked by ), if their actual finish time (i.e., still executing or just completed but memory not yet released), their memory requirement is included in the sum; otherwise, it contributes 0. This piecewise function simulates the lifecycle of memory occupancy via sign judgment, counting memory only during the active period of tasks, reflecting the dynamic allocation and release behavior of intermediate results such as activations and gradients in training.

The value of is computed as

Equation (7) provides the earliest executable time that node l must wait for when GPU g has insufficient memory: among all tasks already assigned to g, find the completion time such that after finishes, the available memory on the GPU first meets the demand of l, and take the minimum of such . This equation essentially identifies the critical points of memory release, ensuring that l does not start earlier than resource readiness, embodying the serialization scheduling constraints in resource-constrained environments.

Additional constraints on DAG workload execution include the following:

Constraints (8)–(16) form the core integer linear constraint system of the scheduling problem. Among them, Equations (8) and (9) declare and as binary assignment variables; Equation (10) ensures that each node l is assigned to exactly one GPU; Equation (11) ensures that each GPU belongs to exactly one server; Equations (12) and (13) define the mapping functions and via weighted sums, facilitating reference to actual devices in the objective; Equation (14) computes the execution time of node l on its assigned GPU, i.e., workload divided by the compute capability of that GPU, reflecting performance differences in heterogeneous hardware; Equation (15) obtains the finish time from actual start time plus execution time; and Equation (16) forces all nodes within the same computational unit to be mapped to the same GPU, preserving locality in model parallelism or pipeline stages and preventing communication explosion due to unnecessary cross-device partitioning.

The objective of a scheduler is to minimize the final finish time () of a DAG-structured neural network training job:

The objective function in Equation (17) defines the ultimate metric of scheduling optimization as the maximum of the actual finish times of all nodes in the DAG, i.e., the total time to train one mini-batch. Minimizing is equivalent to compressing the critical path length while balancing various bottlenecks from computation, communication, and memory contention, making it the core optimization goal of the hybrid parallel training scheduling problem.

We formally define the Neural Network with Hybrid Parallel (N2HP) scheduling problem as follows:

3.3. Analysis of Computational Complexity

In this section, we show that N2HP is NP-complete. We begin by presenting the set partition problem, one of Karp’s 21 NP-complete problems [39], and then show a polynomial-time reduction from it to N2HP.

Set Partition Problem: The problem is to split a set Q into two disjoint subsets with equal sums. Let have sum . The problem asks if the remaining elements form a subset with sum such that .

Theorem 1.

N2HP belongs to the class of NP-complete problems.

Proof.

For the decision version of N2HP, we consider a DAG-structured job defined by , a GPU-based parallel computing system , and a performance limit l. The question is if a scheduling approach exists that achieves .

To demonstrate that N2HP belongs to NP, we begin by confirming that can be computed in polynomial time under any given schedule. Starting with a DAG, we apply topological sorting to arrange its vertices in linear time, as described in Cormen et al. [40]. Using this order, we compute the longest paths from a chosen starting vertex by processing each vertex and determining the maximum path length through its incoming edges, also in linear time [41]. The is then derived by identifying the longest path among all entry nodes in polynomial time. Thus, for any scheduling plan, we can efficiently calculate , compare it to the threshold l, and verify the solution, thereby confirming that N2HP is in NP.

To establish the NP-hardness of N2HP, we consider a simplified instance of N2HP with a specific network structure. The simplified job consists of n task nodes, including entry nodes and a single exit node. The computing platform comprises two identical GPUs on a server. The execution time of the exit node, as well as all data transfer costs from the entry nodes to the exit node, are considered negligible. Under these conditions, the DAG reduces to a star topology, while the platform becomes two homogeneous GPUs without bandwidth limitations. This abstraction eliminates the effects of communication delays and dependency overheads, isolating the node placement problem for analysis. Although not encompassing complete intricacy of practical N2HP situations, this treatment demonstrates that computational difficulty endures even in this severely simplified scenario. The goal of minimizing the job’s completion time can be reduced to the problem of splitting the entry nodes’ execution times into two collections with matching sums. This specific case of N2HP can be directly transformed to the classic set partition problem [39]: the set Q denotes the execution times of entry nodes, subset A represents those entry nodes allocated to one GPU, and represents those entry nodes assigned to the other. This reduction establishes that N2HP is computationally not easier than the set partition problem. Given that the reduction executes in polynomial time and N2HP ∈ NP, we prove that N2HP is NP-complete. □

4. Design of the Proposed Algorithm

Given the NP-completeness of N2HP established in Section 3.3, no polynomial-time algorithm exists that guarantees optimal solutions unless . This section presents the design of the Whale Optimization and Reinforcement Learning-based Running Time Gap Strategy (WORL-RTGS). First, we introduce a variable to quantify the gap between scheduling strategies and demonstrate its positive correlation with the running time difference between two scheduling schemes. Then, inspired by the hunting behavior of humpback whales, we design a time-difference Whale Optimization method to control the positioning of new whales during the generation of candidate scheduling schemes. The time-difference Whale Optimization method consists of three components, each representing a mechanism by which the scheduling plan iteratively approaches the optimal solution. Finally, based on the inference results of the time-difference Whale Optimization method, we design a Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN)-based method to locate the position matrix of new whales.

4.1. Introduction to the WOA

The WOA is a nature-inspired metaheuristic modeled on the social hunting behavior of humpback whales, especially their Bubble-Net Feeding Strategy. The WOA iteratively transitions between exploration (global search) and exploitation (local search). Using different mathematical formulations for these phases, WOA maintains a balance between wide-ranging search and precise local optimization. The algorithm simulates key behaviors such as the Spiral Bubble-Net Attack and Prey Encircling through subsequent procedures:

- Encircling Prey:

Whales identify the position of their prey and proceed to envelop it. This behavior is represented mathematically as

where represents the current best solution’s position, is the position vector of a whale, and and are coefficient vectors given by

where linearly decreases from 2 to 0 over iterations and .

- Bubble-Net Attacking (Exploitation Phase):

The Bubble-Net Strategy is modeled through a spiral movement, allowing whales to refine their search around high-quality solutions. This motion is expressed by the spiral update equation:

where , the parameter b controls the spiral’s shape, and l represents a uniformly distributed random variable within the interval .

- Search for Prey (Exploration Phase):

To maintain diversity and avoid premature convergence, whales perform random searches across the global space. When , the update is modeled as

where represents a randomly chosen whale’s position from the current population.

The Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) starts by generating an initial set of candidate solutions, representing whales, with random placements across the search domain. During every cycle, the fitness of these potential solutions is evaluated through a problem-specific objective function. Subsequently, the whales adjust their locations either by approaching the current best-known solution or by exploring new regions, according to a probabilistic rule. This iterative process continues until a stopping criterion is reached, such as a maximum number of iterations or attainment of a convergence threshold.

Task scheduling in distributed systems with DAG-structured workloads constitutes a challenging combinatorial optimization problem. It involves assigning heterogeneous tasks to diverse resources while adhering to constraints on execution time, resource utilization, and data locality. Effective solutions must strike a balance between broad exploration of the search space and fine-grained exploitation of promising regions. WOA is well suited to this requirement because its mathematical model alternates naturally between exploration and exploitation, thereby mitigating premature convergence and enabling near-optimal schedules to be discovered. In this formulation, the position of each whale encodes a mapping of tasks to resources, offering a direct and intuitive representation of scheduling decisions. Compared with alternative metaheuristics such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), WOA requires fewer control parameters and relies on simpler update mechanisms, which reduces computational overhead and accelerates convergence. Furthermore, its flexible structure allows seamless integration of domain-specific heuristics, such as awareness of data locality and task precedence. Consequently, we employ WOA as the optimization backbone of this work, with additional problem-driven enhancements incorporated to further improve scheduling efficiency. These refinements are elaborated in the following subsections.

4.2. Analysis of Positive Correlation

This section analyzes the relationship between Scheduling Plan Distance (SPD) and Finish Time Gap (FTG) using both theoretical arguments and experimental evidence. To highlight their inherent positive correlation, we begin by analyzing a representative workload with a clearly defined network structure as described in Section 3.3. In this scenario, we derive an analytical expression showing that , revealing a direct linear dependency between the two metrics. This theoretical insight lays the foundation for our subsequent experimental validation across a range of diverse scheduling cases.

The Finish Time Gap () represents the absolute difference in completion times between two scheduling strategies, formulated as

where is the final finish time for scheduling plan , . This metric reflects the performance gap between two scheduling strategies in terms of makespan.

Scheduling Plan Distance () is a novel metric introduced in this work to quantify the distance between two scheduling plans, denoted as and . It captures the degree of difference in workload distribution across GPUs between the two plans. The metric is formally defined as

where n is the total number of nodes in the neural network, and denotes the cumulative execution time computed according to Equation (14) of all nodes mapped to the same GPU as node l under scheduling strategy with i being either 1 or 2. To compute , we first determine, for each node l, the absolute difference in workload between the GPUs to which l is assigned in the two scheduling plans. These differences reflect how much the GPU workloads vary between the two plans from the perspective of each node. Finally, we take the average of these absolute differences over all nodes to obtain the overall value. This metric provides an intuitive and quantitative means of comparing scheduling plans, especially in terms of their impact on load balancing and GPU utilization.

In WORL-RTGS algorithm, we utilize the Finish Time Gap () as a measure of dissimilarity between two scheduling plans. This metric provides an intuitive and direct reflection of how the overall performance differs between two scheduling approaches. Although serves as a useful evaluation metric, it is not directly applicable for steering the creation of new scheduling strategies in iterative optimization. To address this, we investigate the mathematical connection between and the Scheduling Plan Distance (), a novel structural measure introduced here. Our findings indicate a robust positive correlation, where an increase in typically corresponds to a proportional rise in . This finding is crucial, as it allows us to indirectly control and optimize by manipulating . Leveraging this relationship, we treat as a proxy objective that is differentiable and structurally informative, making it suitable for guiding the search process. In particular, we use the functional form of to derive directions for generating next step scheduling plans, elaborated in Section 4.3.

To explore the connection between and , we analyze a distinct workload scenario featuring a clear network structure. The workload consists of n task nodes, including entry nodes and a single exit node. The computing platform comprises two identical GPUs on a server. The execution time of the exit node, as well as all data transfer costs from the entry nodes to the exit node, are considered negligible. Under these conditions, the DAG reduces to a star topology, while the platform becomes two homogeneous GPUs without bandwidth limitations. Each entry node requires 1 s of execution time. In the baseline scheduling strategy , the entry nodes are split evenly, with each GPU handling nodes. Conversely, in the second strategy , GPU processes entry nodes, while GPU manages nodes, where and . Let represent the degree of imbalance between the two plans. We then derive the Scheduling Plan Distance as

Since each node has a unit execution time, the Finish Time Gap between the two scheduling plans is determined solely by the workload imbalance across the GPUs. In particular, as balances the workload equally, and does not, the Finish Time Gap is given by

Substituting Equation (29) into Equation (28), we obtain the following:

This reveals a clear linear relationship between and within this particular workload context. This theoretical result supports the idea that can be used as a proxy for controlling during scheduling optimization.

Furthermore, to comprehensively investigate the relationship between and , we conduct a series of large-scale experiments using both real-world data from the Alibaba Cluster Trace Program (https://github.com/alibaba/clusterdata, accessed on 6 November 2025) and synthetically generated workloads. The dataset from Alibaba’s operational clusters contains detailed job scheduling information, including DAG structures for both batch workloads and long-running online services, making it highly suitable for evaluating task scheduling strategies.

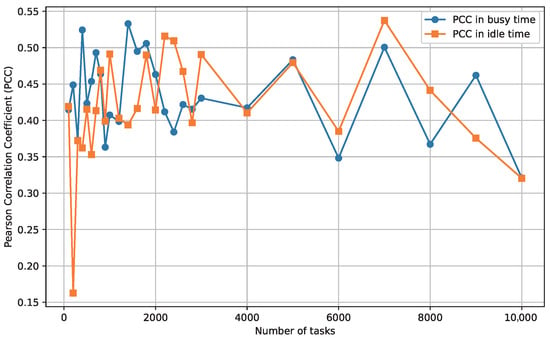

Real-World Data Experiments. The experimental analysis using the Alibaba Cluster Trace data is divided into two groups based on server status: busy and idle, to reflect different practical workload conditions. In the busy state, each GPU’s resource usage rate is randomly sampled from the range , while in the idle state, it is sampled from . Jobs are randomly selected from the trace across various computational scales. Specifically, the number of nodes ranges from 100 to 1000 in increments of 100 for small-scale jobs, from 1200 to 3000 in increments of 200 for medium-scale jobs, and from 4000 to 10,000 in increments of 1000 for large-scale jobs. We simulate six cluster environments with 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 GPUs, each capable of processing multiple nodes concurrently. For each combination of GPU count, system state (busy/idle), and job scale (small/medium/large), we perform 1000 repetitions to ensure statistical reliability. In each repetition, two distinct scheduling plans, and , are randomly generated, and and are computed according to Equations (25) and (26). The resulting pairs are recorded for correlation analysis. After completing all repetitions for each combination of GPU count, system state and job scale, we compute the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) [42] to quantify the strength of the correlation between and .

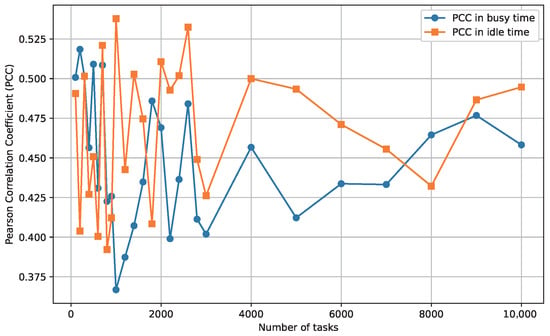

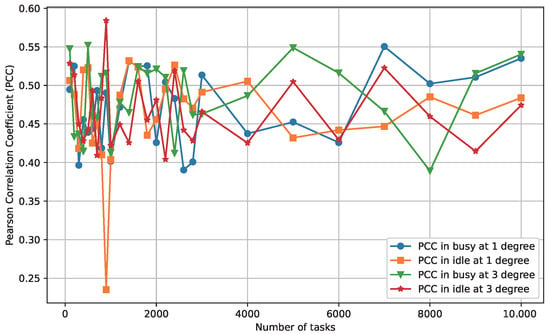

The experimental results in Table 1 report the PCC values between and across different GPU count, workload scales, and system states, based on real-world Alibaba cluster data. Each PCC value in Table 1 represents the mean correlation calculated for a specific combination of GPU count, system state, and job scale. Overall, the results indicate a consistent positive correlation across all configurations, suggesting that higher SPD values generally correspond to higher FTG values. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show this trend specificly for 50-GPU and 500-GPU clusters, respectively. Both line charts show a clear positive relationship between and , reinforcing that the SPD metric can serve as a reliable indicator for FTG across different cluster scales. Notably, while the correlation strength fluctuates slightly depending on job scale and system state, no negative correlations are observed, highlighting the robustness of SPD as a predictive metric. These PCC values indicate a moderate correlation strength, aligning well with benchmarks in the scheduling literature where proxy metrics for makespan (e.g., load imbalance or resource utilization) typically yield PCCs in the range of 0.3–0.6 [43,44]. For instance, PCC was used for load correlation detection in VM placement decisions to minimize Service Level Agreement (SLA) violations and migration counts. Experiments show that PCC-guided load balancing can reduce energy consumption by 15% to 20%, with PCC values in the range of 0.4–0.55 considered sufficient for dynamic optimization [43]. Higher PCCs (>0.7) are rarer in such complex, dynamic environments and often limited to synthetic, low-variability benchmarks; thus, our results are not only comparable but also indicative of SPD’s suitability as a proxy for FTG in practical DAG scheduling, where full linear predictability is not required.

Table 1.

PCC for and on real-world workloads.

Figure 3.

Positive correlation between FTG and SPD for Alibaba workflows with 50 GPUs.

Figure 4.

Positive correlation between FTG and SPD for Alibaba workflows with 500 GPUs.

We acknowledge that the average PCC of 0.4603 reflects moderate rather than strong linear correlation (where PCC > 0.7 is conventionally considered strong). However, in complex DAG scheduling under resource contention and precedence constraints, there may not exist perfect linearity and consistent directional alignment is of more practical significance: SPD and FTG monotonically co-vary across all tested conditions. To further validate this non-parametric robustness, we supplement SPD and FTG with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (), which measures monotonicity without the assumption on linearity.

Table 2 reports Spearman’s for the same experimental configurations. Values range from 0.49 to 0.55 with mean = 0.52 and variance = 0.004, consistently higher than PCC and uniformly positive, confirming that the relationship between SPD and FTG is even stronger than linear trends. This is expected because structural divergence SPD influences makespan FTG through cumulative, nonlinear dependency chains, precisely the regime where rank-based metrics outperform Pearson’s. Critically, no configuration yields negative , and the gap holds in 92% of the cases, reinforcing that SPD provides reliable monotonic guidance even when linear fit is moderate. In optimization contexts such as WORL-RTGS, this ensures that minimizing SPD would reduce FTG on average. Edge cases with lower PCC (e.g., 0.386) still yield , preserving directivity.

Table 2.

Spearman’s between and .

Synthetic Workload Experiments. The experimental analysis with synthetically generated workloads, also divided into busy and idle states. GPU resource usage is sampled in the same ranges as in the real-world experiments. We simulate the same six cluster environments, with job scales and node counts as previously described. Execution times for jobs are sampled from normal distributions: for small-scale, for medium-scale, and for large-scale jobs. DAG topologies are generated using the Erdos–Rényi model [45], with the average in-degree/out-degree set to either 1 or 3, resulting in 54 workloads in total: 27 with degree 1 and 27 with degree 3. For each combination of system state, job scale, GPU count, and average degree, we perform 1000 independent repetitions. In each repetition, two scheduling plans, and , are randomly created, and and are computed. The pairs are recorded for correlation analysis, and the PCC is computed for each combination to measure the correlation strength between and .

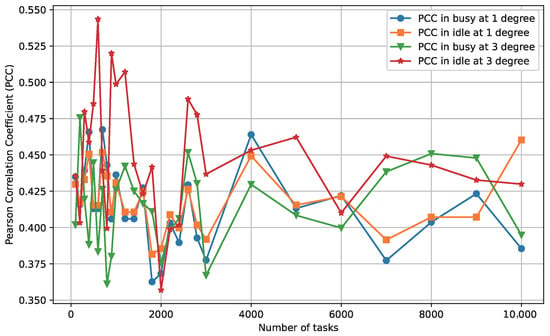

Table 3 reports the PCC values between and under synthetic workloads across different system states, job scales, GPU counts, and average in-degree/out-degree. Overall, the results demonstrate a consistently positive correlation, with PCC values ranging approximately from 0.39 to 0.55. Stronger correlations are observed for medium and large workloads in the busy state, especially when the correlation degree is 3 (e.g., 0.550 at 20 GPUs and 0.534 at 200 GPUs). In the idle state, small workloads exhibit greater variability, while medium and large workloads remain relatively stable, often exceeding 0.45 and reaching above 0.54 in several cases. Figure 5 and Figure 6 further show the positive trend, showing consistent correlation of 50 GPUs and 500 GPUs. These PCC values indicate a moderate correlation strength, aligning well with benchmarks in the scheduling literature where proxy metrics for makespan (e.g., load imbalance or resource utilization) typically yield PCCs in the range of 0.3–0.6 [43,44], particularly in heterogeneous or variable-degree topologies. In our case, the slightly higher PCCs for (e.g., up to 0.550) underscore SPD’s enhanced predictiveness in denser graphs, where inter-task dependencies amplify load-makespan sensitivity, ideal for our proxy’s role in WORL-RTGS, as it enables reliable indirect minimization of FTG amid topological variability.

Table 3.

PCC for and on synthetic workloads.

Figure 5.

Positive correlation between FTG and SPD for synthetic workflows with 50 GPUs.

Figure 6.

Positive correlation between FTG and SPD for synthetic workflows with 500 GPUs.

As in the real-world data, we compute Spearman’s for synthetic workloads. Across all 108 configurations, ranges from 0.42 to 0.59 with mean = 0.508 and variance = 0.004, again outperforming PCC and uniformly positive. The improvement is most pronounced in high-degree () topologies, where dependency chains amplify effects (e.g., vs. PCC = 0.550 at 20 GPUs, medium scale, busy state). This further validates SPD’s robustness as a proxy in topologically complex scenarios.

Furthermore, the positive correlation observed in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 has profound implications: it empirically substantiates that greater structural divergence in scheduling plans (SPD) reliably predicts larger makespan disparities (FTG), enabling SPD to steer search toward balanced, low-makespan solutions without exhaustive FTG evaluations. This not only accelerates convergence in metaheuristic frameworks but also enhances load balancing, as higher SPD correlates with imbalance-induced delays, directly tying to energy efficiency and SLA compliance on GPU clusters.

The results shown in the experiments of real-world data and synthetic workloads confirm a persistent positive correlation between and across varying conditions. In all cases, the PCC value remains above zero. From a statistical perspective, the PCC values ranging from 0.16 to 0.57 with the average of 0.4603 and variance around 0.003 suggest a consistent trend: as increases, tends to increase as well. These experiments clearly illustrate the increasing trend of with larger values of . This persistent positive correlation, spanning workload scale, topology, cluster size, and utilization, validates SPD as a reliable proxy for FTG. The moderate PCC strength (mean 0.46) is reasonable for DAG scheduling problems, where exact linearity may not exist due to precedence constraints and resource heterogeneity [43,44]; instead, it ensures directional guidance for optimization, reducing makespan by aligning structural adjustments with performance gaps. Notably, the absence of negative correlations across diverse setups and the low variance (0.003) make SPD a computationally tractable surrogate in iterative algorithms such as WORL-RTGS. We report global Spearman’s , reinforcing stability and predictability. In WORL-RTGS, we exploit this relationship to indirectly optimize makespan by minimizing SPD via differentiable, structural updates (Section 4.3). The data and code used to generate these visualizations are publicly available in our GitHub repository (https://github.com/AIprinter/WORL-RTGS.git, accessed on 6 November 2025). This observed correlation plays a crucial role in our algorithm design. It provides theoretical and empirical support for using as a proxy to indirectly control and optimize , thereby improving the efficiency of our scheduling strategy.

4.3. Whale Optimization and Reinforcement Learning-Based Running Time Gap Strategy

We design WORL-RTGS by integrating the WOA with a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) framework. WOA is a nature-inspired meta-heuristic optimization algorithm introduced by Seyedali et al. [7] in 2016, modeled on the unique hunting behavior of humpback whales [46].

In the context of WORL-RTGS, each humpback whale metaphorically represents a candidate scheduling plan. This plan is encoded as an n-dimensional vector, where each dimension specifies the GPU assigned to a corresponding task node. A population of whales is maintained across iterations, with each whale representing a different scheduling plan. Following the core principles of WOA, the optimization process in WORL-RTGS is divided into three phases. Encircling Prey phase simulates the convergence towards an optimal solution, Spiral Bubble-Net Feeding Maneuver balances exploration and exploitation through a logarithmic spiral, and Search for Prey phase diversifies the search space by moving whales randomly. In each iteration, every whale updates its position by executing one of these three directions. However, the traditional WOA mechanism is insufficient for accurately determining the position matrix of a new whale when applied to complex task scheduling problems, especially in high-dimensional GPU assignment spaces. To overcome this limitation, WORL-RTGS integrates a Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) module within the DRL framework. Based on the direction selected by WOA, the DDQN is responsible for predicting the next-step position matrix for each whale, thereby enhancing the quality and precision of the scheduling plan evolution.

4.3.1. Encircling Prey

Humpback whales are able to detect prey and move around it. In WORL-RTGS, the prey’s position is analogous to the Optimal Scheduling Plan (OSP). Since the exact OSP is unknown beforehand, the algorithm instead designates the best available scheduling plan at each step as the target prey, represented by the leading whale. Once this leader is identified, the remaining whales adjust their positions in relation to it, which is expressed mathematically as

where k denotes the iteration index, while A and C are coefficients obtained from Equations (33) and (34). The term represents the leader’s position, i.e., the best scheduling plan in iteration k. Each whale in the population is represented by , and its updated position in the next iteration is given by . The symbol indicates element-wise absolute values, and the operator · refers to element-wise multiplication. The distance between a whale and the leader is expressed as D. The definitions of A and C are provided below:

where is a random value uniformly sampled from the interval . The parameter introduces stochasticity into both A and C, ensuring population diversity and preventing premature convergence. Its value in represents the normalized probability range for random behavior: corresponds to no influence from the leader (pure exploration), whereas enforces complete attraction toward the leader (pure exploitation). This probabilistic modulation helps balance the two phases during optimization. The coefficient controls the exploration–exploitation transition. As Equation (35) shows, decreases linearly from 2 to 0 as the iteration index k increases, meaning that early iterations favor exploration (larger A range) and later iterations emphasize exploitation (smaller A). Consequently, A is confined to the range , gradually shrinking to zero as convergence progresses. denotes the maximum number of iterations and governs the temporal decay of . Together, dynamically adjust the search pressure toward the best scheduling plan .

In practice, Equation (31) can measure the actual distance between humpbacks, but applying it directly to scheduling plans is not meaningful. Each dimension of a plan corresponds to a GPU index, and subtracting one index from another provides no useful interpretation. To resolve this, we introduce , defined in Equation (25), as a metric for quantifying differences between humpbacks. However, by itself is insufficient for directly producing new scheduling plans. To overcome this limitation, we leverage its positive correlation with , as discussed in Section 4.2. By translating into , we derive a more actionable metric that facilitates the generation of new humpback positions—corresponding to scheduling plans—throughout the iterative procedure.

It is not feasible to directly generate the next-step humpback whale location, , using Equation (32) based solely on a given value of , as computed from Equation (25). The challenge stems from the fact that is a single scalar capturing only the absolute gap in final finish times, while scheduling plans are inherently high-dimensional vectors. As a result, lacks the necessary structure and dimensionality to guide the generation of a new scheduling plan vector directly. To overcome this challenge, we must find a function that not only reflects the behavior of but also supports extension into a multidimensional space consistent with the representation of scheduling plans. This is where our earlier analysis proves useful: we have observed a medium positive correlation between and in Section 4.2, meaning that as the between two scheduling plans increases, the corresponding also tends to increase. This correlation enables us to indirectly control by manipulating . Therefore, in the optimization process, we replace the original abstract distance term D in Equation (32) with to guide the humpback’s movement. Unlike , is computable based on the structural differences between scheduling plans and can be naturally expanded to a higher dimensions. This allows us to use not only as a proxy for but also as a foundation for deriving new, high-dimensional scheduling plans through Reinforcement Learning-driven methods.

The next position of a humpback whale, , is obtained by first deriving a set of target values, referred to as . Each represents the expected workload which is the total execution time of the GPU that task node is expected to be assigned to in the upcoming scheduling plan . Formally, this is expressed as

where indicates the GPU to which task node is mapped, and computes the total execution time of tasks assigned to that GPU under the new plan.

To construct this list of hope values for all task nodes , we rely on both the leader whale’s location and the current whale’s position in iteration k. Specifically, denotes the current load on the GPU handling task node in the leader whale’s scheduling plan :

represents the current load on the GPU handling in the given humpback’s current location :

With both and known, the algorithm derives based on the relative influence of the leader and current humpback states guided by the coefficients defined in the WOA mechanism. This hope value list then serves as a basis for reassigning task nodes in order to construct the whale’s next-step scheduling plan .

Substituting Equation (31) into Equation (32) and comparing with Equation (25), we obtain the following:

Here, D is substituted with to quantify the gap between two scheduling plans. As shown in Equation (39), the gap between the leader whale and its follower in the next step is scaled by factor A. During this stage, the randomness term C is omitted; assigning effectively removes stochasticity and ensures the leader humpback’s position remains deterministic.

Since Section 4.2 shows a positive correlation between and , we suggest employing as a substitute for . By making this substitution in Equation (39), we bridge the distance with a more interpretable and extendable metric in multidimensional scheduling space. Thus, the distance between the leader’s load distribution and the hope distribution in the next-step schedule can be expressed as

To derive the above expressions, we make a simplifying assumption: for each task node , the corresponding terms on both sides of the equation are equal, that is

Under this assumption, the hope load for each GPU node at the next position can be calculated through the following transformation:

Equation (43) expresses the estimated load on the GPU hosting task node at the humpback whale’s next position. It is calculated based on a weighted difference between the leader whale’s load and the current whale’s load, scaled by the factor A. The ± sign introduces a bifurcation in movement direction, which aligns with the behavior modeled by the WOA algorithm enabling the search to either approach or diverge from the leader, depending on the optimization dynamics in a given iteration. WORL-RTGS feeds the value of from Equation (43) into the DDQN module detailed in Section 4.3.4, which then determines the next humpback position according to the optimization objective.

In WORL-RTGS, every humpback whale chooses a unique direction for movement in each iteration. For each selected path, a distinct derivation process is applied to assess the computational demand on the GPU hosting each task node at the whale’s anticipated next location. For instance, in the Encircling Prey phase, this estimation is formulated in Equation (43), which provides the predicted load values referred to as hope values, based on the current and leader positions. In the subsequent sections, namely Section 4.3.2 and Section 4.3.3, we apply a similar derivation methodology to the other two behavioral strategies: Bubble-Net Attacking Method and Search for Prey. These derivations likewise yield a list of hope values tailored to each phase, enabling us to generate updated scheduling plans that reflect the selected movement strategy within the WOA-inspired optimization framework.

4.3.2. Bubble-Net Feeding Strategy (Exploitation Phase)

Humpback whales employ a distinctive hunting technique known as Bubble-Net Feeding [47]. They submerge approximately 12 m, then generate bubbles along a path resembling a ‘9’ to encircle a school of fish, ascending toward their target. This Bubble-Net Feeding behavior comprises two key mechanisms: a shrinking encirclement process and a spiral position update.

Shrinking encirclement process. In Equation (32), the coefficient A is randomly generated from the interval , with a decreasing linearly as the iteration index k grows. Consequently, the absolute value of A gradually reduces over the course of the iterations. This gradual reduction causes the search area around the the leader solution to contract progressively. In the context of the Encircling Prey phase, this mechanism reflects the humpback whale’s strategy of narrowing its focus and moving closer to the optimal solution as the optimization progresses. The shrinking encirclement helps guide the algorithm toward exploitation by reducing randomness and encouraging convergence in the later stages of the search process.

Spiral position update. Seyedali et al. [7] proposed a spiral equation to emulate the distinctive helical motion of humpback whales. The procedure first measures the distance between a whale at and the current leader at . Based on this distance, a new position along a spiral path between and is computed using the following formulation:

where represents the distance between the whale’s current position and that of the leader, b is a constant parameter, and l is a random value sampled from the interval . The random variable controls the direction and amplitude of the spiral motion. Values of l close to produce outward spirals (encouraging exploration), while values near 1 generate inward spirals that contract toward the leader (favoring exploitation). Sampling l symmetrically around zero allows the algorithm to maintain a balanced probabilistic tendency between expansion and contraction around the current best solution.

As in the Encircling Prey strategy, the Spiral Bubble-Net Movement determines the whale’s next position by first estimating the hope load on the GPU assigned to task node at that location. Using a derivation approach analogous to that in the encircling phase, we obtain the following expression for the hope value:

Humpbacks reduce the circle while following a spiral trajectory at the same time. To replicate this dual behavior, a random variable is introduced to decide the movement pattern. If , the whale updates its position using the shrinking-encircling mechanism; otherwise, the spiral updating rule is applied as follows:

4.3.3. Searching for Prey (Exploration Phase)

In natural hunting scenarios, humpback whales know the prey’s location and head straight toward it. However, in the context of discovering a suboptimal scheduling plan, whales in WORL-RTGS are not always guaranteed to converge on a globally optimal solution. Instead, they may become trapped in a local optimum by repeatedly moving toward a currently best-known solution.

To enhance global exploration and avoid local optima, WORL-RTGS adopts a strategy where a humpback whale is forced to explore new regions of the solution space when . Under this condition, the current leader whale is no longer followed. Instead, a random whale is selected to act as a temporary guide, and the current whale at position is repelled from this randomly chosen whale. This mechanism increases diversity in the population and encourages exploration of unvisited scheduling plans. The corresponding position update rule is given by

where represents the scheduling plan of a randomly chosen whale, while D is the distance to this whale from the current whale, scaled by the random factor C.

To derive the expected workload which is the hope value on the GPU that hosts task node at the next-step location , we apply the same transformation used in other movement strategies. The resulting expression is

where is the current total execution time of all task nodes mapped to the GPU processing in the randomly selected whale. This equation allows WORL-RTGS to estimate the updated task distribution under the exploration-driven movement and facilitates the generation of new scheduling candidates with greater diversity.

Having introduced the three behavioral mechanisms of the humpback whale: Encircling Prey, Bubble-Net Attacking, and Search for Prey, we have derived three corresponding sets of target values, denoted as . Each set represents the desired workload outcomes for task nodes under one of the three movement strategies, guiding how the whale (i.e., the scheduling plan) should evolve in the next iteration. The next step is to translate these hope values into a concrete next-step scheduling plan, i.e., the whale’s updated position. To achieve this, the WORL-RTGS algorithm employs a Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) framework. The DDQN is used to generate a scheduling plan that aligns as closely as possible with the desired workload distribution specified in the corresponding list, thereby guiding the whale or scheduling plan toward more optimal solutions in a structured and adaptive manner.

4.3.4. DDQN-Based Whale Position Generation

To generate an optimized scheduling plan , we design a Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) module that predicts the optimal GPU assignment for each task node based on its expected workload, denoted as . The DDQN agent is trained to learn a mapping strategy that minimizes the deviation between the actual and expected GPU workloads, thereby enhancing scheduling efficiency in high-dimensional task allocation scenarios. The corresponding Markov Decision Process (MDP) is defined as follows.

- State Space :

Each state characterizes the scheduling environment of task node and includes the following components: the index of the current task node ; the expected workload vector , where n denotes the total number of task nodes, and each entry corresponds to the desired total load on the GPU to which is expected to be assigned; the computational workload vector for all task nodes (e.g., measured in FLOPs); and the current GPU load vector , where m is the number of GPUs. Thus, each state is represented as

- Action Space :

The action space consists of all available GPUs:

Each action corresponds to assigning task node to a specific GPU.

- Reward Function :

The reward function encourages the agent to minimize the deviation between the predicted and desired GPU workloads:

Here, denotes the predicted load on GPU a after assigning task node to it. The closer this predicted load is to the desired workload value , the higher (i.e., less negative) the reward.

- Training Objective:

The training objective is to derive a scheduling policy that reduces the overall Load Deviation () once all task nodes have been allocated. The is defined as

where denotes the total runtime of all tasks assigned to the same GPU as in the final plan, and represents the expected workload prior to scheduling.

- DDQN Architecture:

The DDQN module is implemented using a lightweight multilayer perceptron (MLP) architecture. The network receives a state vector as input, which encodes the scheduling environment of the current task node. The output is a Q-value vector , where each element corresponds to the estimated cumulative reward of assigning task node to one of the m available GPUs. The network consists of an input layer of size . This is followed by two hidden layers containing 128 and 64 units, respectively, each using the ReLU activation function. The final output layer has m units and uses a linear activation to produce Q-values for each possible GPU assignment.

During training, we employ experience replay and the Double DQN target update strategy to stabilize learning. The Q-value update is computed as

with the corresponding loss function defined as

To mitigate overestimation bias, the parameters of the target network are periodically synchronized with those of the online network.

The pseudocode of the DDQN-based whale position generation method is presented in Algorithm 1. This method is applied in conjunction with the three behavioral mechanisms of the humpback whale: Encircling Prey, Bubble-Net Attacking, and Search for Prey, each of which yields a corresponding set of target values, denoted as . The complete pseudocode of the overall WORL-RTGS algorithm is provided in Algorithm 2. We begin by presenting the pseudocode of Algorithm 1, followed by the full process of the WORL-RTGS algorithm as shown in Algorithm 2. Algorithm 1 presents the DDQN-based task-to-GPU scheduling method. In each training episode, task nodes are scheduled sequentially according to a topological order. For each task node, the current state is constructed and used as input to the online Q-network to select the GPU with the highest predicted Q-value. The selected action is applied by assigning the task to the chosen GPU and updating the current load. A reward is computed based on the deviation between the expected and predicted GPU load, and the transition tuple is stored in the replay buffer. Mini-batches drawn from the buffer are employed to update the online network through Q-learning, with target Q-values computed using the Double DQN approach. The target network is synchronized with the online network at regular intervals. After training, the learned Q-network is used to generate the final scheduling plan . Algorithm 2 outlines the integrated optimization procedure of the WORL-RTGS algorithm, which combines the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) with a DDQN-based scheduling module. The algorithm begins by initializing a population of humpback whales and evaluating their fitness values using Equation (17). The best-performing whale is selected as the current leader. At each iteration, whale positions are updated according to one of three behaviors: Encircling Prey, Searching for Prey, or Spiral Bubble-Net Attack, determined by the randomly chosen control parameters r and p. For each behavior, a corresponding hope value list is computed, and the DDQN module as Algorithm 1 is invoked to guide the position update. After all whales are updated, their fitness values are re-evaluated and the leader is updated accordingly. The process continues until the maximum iteration limit is reached, at which point the optimal solution is delivered. As iterations progress, the magnitude of steadily declines from 2 to 0, facilitating a shift from exploration to exploitation. In each cycle, WORL-RTGS chooses between a spiral or circular trajectory based on a randomly determined parameter p. Once a humpback whale selects its movement pattern, a set of hope values is computed. Guided by a Q-network, a new whale position is established by fulfilling these hope values. Successful fulfillment of the hope values ensures that the metric is also met, owing to its positive correlation with , as discussed in Section 4.2. For reference, the primary parameters utilized in the algorithm are outlined in Table 4.

| Algorithm 1 DDQN-Based Task-to-GPU Scheduling Algorithm. |

|

Table 4.

Notations and parameter descriptions used in the algorithm.

The overall computational complexity of the WORL-RTGS algorithm is determined by the interaction between the Whale Optimization loop and the DDQN-based scheduling procedure embedded within each iteration. In the DDQN-based whale next-position generation method Algorithm 1, let denote the batch size used in the replay buffer during training and n denote the number of task nodes. Let denote the number of training episodes. For each episode, the algorithm iterates over all n task nodes. For each task node, it performs: state construction and action selection using the Q-network: , where m is the number of GPUs; reward computation and buffer update: ; and backpropagation on the sampled batch of size : . Thus, the total complexity of the DDQN module per episode is , and the overall complexity across episodes is . In the WORL-RTGS optimization loop Algorithm 2, let denote the number of whales in the population, and the total number of optimization iterations. In each iteration, the algorithm evaluates and updates the position of each whale using one of three behavioral strategies. Each position update invokes the DDQN module once. Therefore, the total complexity of the WORL-RTGS algorithm is This reflects the nested nature of the hybrid metaheuristic–learning framework, where each metaheuristic update is guided by a learned scheduling policy.

| Algorithm 2 WORL-RTGS Integrated Optimization Procedure. |

|

The space complexity of the DDQN-based scheduler mainly consists of three parts: the parameters of the online and target Q-networks, the experience replay buffer, and auxiliary data structures for state and load tracking. Assuming an -layer neural network with hidden dimension h, the space for network parameters is . Since both and are maintained, the total becomes . The replay buffer stores experience tuples, each with state, action, reward, and next state, leading to space , where is the state vector dimension. Additionally, the scheduling plan and GPU load tracking introduce negligible overhead . In total, the space complexity is .

5. Performance Evaluation

5.1. Experiment Setup

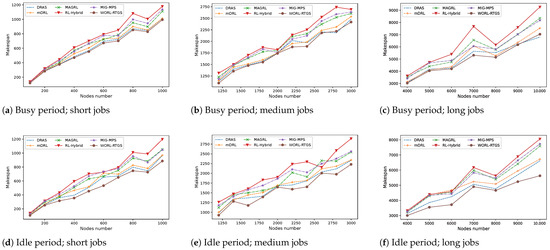

In this section, we first analyze the sensitivity of four key parameters: the number of training episodes , the discount factor , the maximum number of iterations , and the spiral coefficient b. We then conduct comparative experiments between WORL-RTGS and five baseline scheduling algorithms, using both real-world workloads from the Alibaba Cluster Trace v2018 (https://github.com/alibaba/clusterdata, accessed on 6 November 2025) and synthetic DAG-structured workloads. The Alibaba Cluster Trace v2018, collected from Alibaba’s production environment, spans approximately 4000 machines over eight days. It provides DAG-structured workloads, machine status snapshots at each timestamp, and detailed execution logs. To cover short-, medium-, and long-duration workloads, we select jobs from the trace with roughly 100–1000 tasks in steps of 100 for small-scale workloads, 1200–3000 tasks in steps of 200 for medium-scale workloads, and 4000–10,000 tasks in steps of 1000 for large-scale workloads, noting that task counts are approximate. Our evaluation consists of four experimental sets based on DAG-structured workloads, examining system performance under both high-load and low-load server conditions.

The WORL-RTGS algorithm and all baseline scheduling methods are implemented in Java. Workload scheduling tests are executed on a cluster of nine local servers running Ubuntu 20.04.6 LTS with Java 1.8.0_191. Data processing and visualization of results are conducted using Python 3.14.0 on a Windows-based PC. All source code, datasets, and selected instance configurations are openly accessible on GitHub (https://github.com/AIprinter/WORL-RTGS.git, accessed on 6 November 2025).

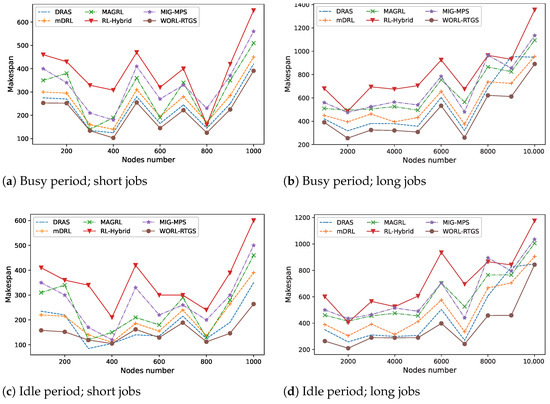

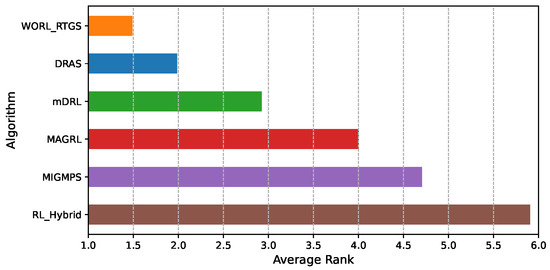

5.2. Comparison Algorithms

- DRAS algorithm [29]: A hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) framework designed for High-Performance Computing (HPC) clusters. It learns a dynamic scheduling policy via Deep Reinforcement Learning (RL), outperforming traditional heuristics by up to 45%.

- mDRL algorithm [32]: This approach leverages multi-agent Reinforcement Learning combined with graph neural networks to schedule deep learning jobs in large GPU clusters. The method focuses on minimizing job completion time by encoding cluster topology and modeling interference. It achieves over 20% improvements compared to stateless schedulers.

- MAGRL algorithm [31]: A topology-aware scheduling framework for large-scale GPU clusters. It uses multiple cooperative RL agents and a hierarchical graph neural network to model both intra-server and inter-scheduler structures. To handle limited feedback, MAGRL incorporates a learned interference model to predict co-location performance. Experiments show it reduces average job completion time by over 20%.

- RL-Hybrid algorithm [33]: This work models GPU cluster scheduling by explicitly accounting for network contention. A Reinforcement Learning agent learns to delay or reorder jobs to reduce network bottlenecks. Experiments show an 18.2% reduction in average job completion time and a 20.7% decrease in tail completion times compared to conventional schedulers.

- MIG+MPS algorithm [30]: Focusing on co-locating multiple tasks on a single GPU using NVIDIA’s MPS/MIG partitioning, this method employs deep RL to jointly optimize partition configuration and job co-location. It achieves up to 1.87× throughput improvement over traditional time-sharing scheduling.

We unify the notation across all the six algorithms to present a concise and consistent time and space complexity analysis. Let n denote the number of task nodes or jobs, m the number of available GPUs, the number of neural network layers, h the hidden layer width, the batch size or replay buffer size, the dimensionality of the input state vector, the dimensionality of the action vector, the total number of training episodes, E the number of edges in a topology graph, and N the number of agents for multi-agent frameworks. For MAGRL, let be the GNN embedding dimension. For WORL-RTGS, let be the number of Whale Optimization iterations and the number of whales.

Although the theoretical time complexity of WORL-RTGS appears higher due to the presence of multiplicative constants such as , , , and as shown in Table 5, these values are typically small and fixed in practice. As a result, the actual runtime scaling of WORL-RTGS is primarily linear in the number of tasks n and GPUs m, making it computationally efficient in real-world deployments. In contrast, algorithms such as MAGRL and mDRL involve high-dimensional GNN embeddings , large agent populations N, or complex state or action vectors with dimensionality and , which can easily exceed hundreds of features. This leads to higher-order polynomial complexity terms like or , significantly increasing both computational and memory requirements. Therefore, from a practical perspective, WORL-RTGS achieves a balance by keeping model dimensionality compact and avoiding agent duplication, leading to competitive time and space efficiency in large-scale scheduling scenarios.

Table 5.

Time and space complexity of six scheduling algorithms.

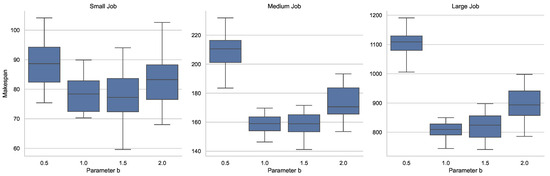

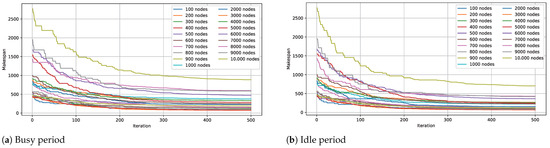

5.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the robustness and performance impact of the WORL-RTGS scheduling algorithm under different hyperparameter configurations, we conduct a parameter sensitivity analysis. We focus on four key parameters from both the DDQN and WOA components of the algorithm: number of training episodes , discount factor , maximum number of iterations , and the spiral coefficient b in the WOA model.

In each experiment, we vary one parameter at a time while keeping the others fixed at their default values. For each configuration, we run the scheduling algorithm 10 times and report the average results of key performance metrics, including the final makespan and convergence behavior. This helps assess the sensitivity and stability of the WORL-RTGS algorithm with respect to changes in each parameter. The design of the sensitivity analysis is summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Experimental design for parameter sensitivity.

5.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis on Training Episodes

To investigate how the number of training episodes affects the performance of the WORL-RTGS algorithm, we conduct a sensitivity analysis by varying while keeping all other parameters fixed at their default values. Specifically, the parameters , , and spiral coefficient are held constant.

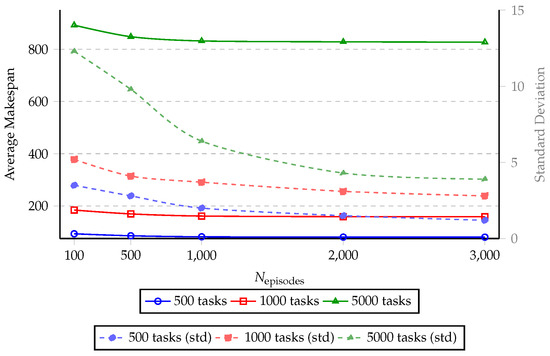

The training episodes control how many times the DDQN agent learns from scheduling experiences for each task node. Intuitively, a small number of episodes may lead to underfitting, while a very large number may cause unnecessary computation without further improvement. Therefore, we test five different values of : 100, 500, 1000, 2000, and 3000. For each configuration, we run the WORL-RTGS algorithm on three benchmark DAG workloads consisting of 500, 1000, and 5000 task nodes selected from the Alibaba Cluster Trace v2018. We collect performance metrics including the final makespan of the generated schedule and the convergence behavior of the learning process. To mitigate the effects of randomness, each test is repeated ten times. The average results and standard deviation are reported in Table 7.

Table 7.

Average makespan and standard deviation under different training episodes.

Figure 7 illustrates the impact of the number of training episodes on the scheduling performance of the WORL-RTGS algorithm. The left y-axis shows the average makespan of the generated schedules across three workloads of different sizes: 500, 1000, and 5000 tasks, while the right y-axis displays the corresponding standard deviations, reflecting the stability of the scheduling results.

Figure 7.

Effect of on makespan (left axis) and standard deviation (right axis).

As increases from 100 to 3000, all three workload sizes exhibit a clear reduction in makespan, especially within the range of 100 to 1000 episodes. For example, in the 500-nodes workload, the average makespan drops from 93.2 to 81.7 as the number of episodes increases from 100 to 1000. However, beyond 1000 episodes, the improvement becomes marginal, e.g., only a 1.4 reduction between 1000 and 3000, suggesting a diminishing return from further training. Meanwhile, the standard deviation decreases steadily across all workload sizes, indicating that more training episodes lead to more stable scheduling decisions. For instance, the standard deviation for the 5000-nodes workload decreases from 12.3 at 100 episodes to 3.9 at 3000 episodes. This confirms that increased training helps the DDQN component converge to more consistent policies.

In summary, increasing improves both scheduling quality and stability up to a certain point, beyond which additional training yields little benefit. A value around 1000 to 2000 appears to offer a good trade-off between performance and training cost.

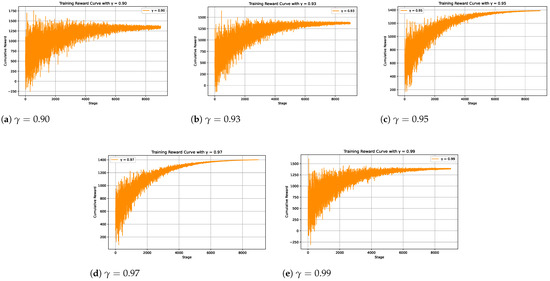

5.3.2. Impact of Discount Factor