Abstract

This study investigates whether incorporating highlighted information in discharge notes improves the quality of the summaries generated by Large Language Models (LLMs). Specifically, it evaluates the effect of using highlighted versus unhighlighted inputs for fine-tuning LLaMA2-13B model for summarization tasks. We fine-tuned LlaMA2-13B in two variants using MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset: one variant fine-tuned with the highlighted discharge notes (H-LLaMA), and the other on the same set of notes without highlighting (U-LLaMA). Highlighting was performed automatically using a Cardiology Interface Terminology (CIT) presented in our previous work. H-LLaMA and U-LLaMA were evaluated on a randomly selected test set of 100 discharge notes using multiple metrics (including BERTScore, ROUGE-L, BLEU, and SummaC_CONV). Additionally, LLM-based judgment via ChatGPT-4o rated coherence, fluency, conciseness, and correctness, alongside a manual completeness evaluation on a random sample of 40 notes. H-LLaMA consistently outperformed U-LLaMA across all metrics. H-summaries, generated using H-LLaMA, in comparison to U-summaries, generated using U-LLaMA, achieved higher BERTScore (63.75 vs. 59.61), ROUGE-L (23.43 vs. 21.82), BLEU (10.4 vs. 8.41), and SummaC_CONV (67.7 vs. 40.2). Manual review also showed improved completeness for H-summaries (54.8% vs. 47.6%). All improvements were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Moreover, LLM-based evaluation indicated higher average ratings across coherence, correctness, and conciseness.

1. Introduction

Electronic Health Records (EHRs) contain a wide range of clinical information, including details of a patient’s hospital stay, progress notes, medical history, medications, vital signs, and diagnostic reports [1]. The exponential growth of EHRs has revolutionized medical data management, enhancing access to patient records, interoperability, and aiding healthcare professionals in making informed decisions [2,3].

However, EHRs are often perceived as cluttered and difficult to navigate, which can significantly hinder healthcare providers’ ability to efficiently extract relevant insights, potentially impacting clinical decision-making and patient safety [4,5]. Several factors contribute to this complexity, including the vast amount of abbreviations and medical jargon, variability in how different healthcare providers document data in EHRs, copy–pasting practices that clutter records with redundant information, and the design of EHR systems themselves.

Summarization of EHRs can solve this problem to a great extent by enabling healthcare providers to quickly access the most relevant information, reducing errors and supporting informed clinical decisions [2,6].

Given the complexity and volume of EHR data, automated summarization methods have become increasingly important. There has been a notable shift from traditional text summarization methods to techniques that use Large Language Models (LLMs) [7,8,9]. These models have evolved from pre-training and fine-tuning approaches to prompt-based methods [10,11,12]. While LLMs demonstrate strong potential in summarization tasks, several challenges persist. One critical issue is “hallucination,” where LLMs generate plausible but factually incorrect information. In the healthcare domain, such inaccuracies can lead to misdiagnoses, inappropriate treatment plans, or worse [13,14]. Additionally, LLMs may overlook crucial clinical details, potentially compromising patient care [15].

Fine-tuning LLMs for EHR summarization offers a promising solution to mitigating these challenges by enhancing its understanding of medical terminology and context [16,17,18]. Fine-tuning is a process that allows LLMs to adapt their general knowledge to specific domains by training them on smaller, domain-relevant datasets, enabling them to learn task-specific patterns and terminology. During fine-tuning, the model’s pre-trained weights are updated to optimize its performance for the target task, allowing it to learn task-specific features and improve accuracy [19,20].

By adapting LLMs to healthcare-specific datasets, fine-tuned models can better grasp domain-specific terminologies and contextual nuances, leading to improved performance in summarization tasks [21]. Moreover, fine-tuning can reduce hallucinations by reinforcing factual content through curated training data [17,18,22,23]. This approach also ensures the inclusion of essential clinical details that might otherwise be overlooked in generic LLM outputs.

The process of fine-tuning LLMs for EHR summarization relies on high-quality datasets [24]. Studies have shown that training models on domain-specific data significantly enhances their ability to interpret and summarize clinical narratives effectively [25,26]. The quality of the dataset used for fine-tuning directly impacts the model’s summarization performance [27].

The MIMIC-IV-BHC dataset, a curated collection of discharge notes that are a key component of EHRs, and corresponding Brief Hospital Course (BHC) summaries, has been introduced [28,29]. This study benchmarked five models (GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Clinical-T5-Large, Llama2-13B, and FLAN-UL2) using both prompting-based and fine-tuning adaptation strategies. The reported results demonstrate that fine-tuned Llama2-13B achieved the highest quantitative scores (BLEU, BERT-Score, ROUGE-L).

However, although fine-tuning can help reduce the frequency of hallucinations by training the model on domain-specific data, it does not entirely eliminate the risk of generating inaccurate information, as the underlying architecture of LLMs can still lead to hallucinations [30]. These studies [30,31] emphasize that while fine-tuning LLMs can improve their performance, there are still challenges, including the potential loss of previously acquired knowledge during the fine-tuning process, which can lead to missing critical information in the generated summaries.

In our previous study [32], we demonstrated that providing discharge notes with automatically highlighted fine-granular clinical details, using the Cardiology Interface Terminology (CIT) curated through machine learning-supported methods [33,34,35], improves the accuracy of LLM-generated summaries when used at inference time via prompt engineering. Highlighted inputs reduced both hallucination and omission errors compared to unhighlighted inputs. Motivated by these findings, the present study examines whether incorporating the same highlighting directly into the fine-tuning process enables the model to internalize these patterns rather than relying solely on prompt-level cues. To this end, we fine-tune LLaMA2-13B (via LoRA) on the MIMIC-IV-BHC dataset using either highlighted or unhighlighted discharge notes and compare the resulting summary quality across multiple evaluation dimensions.

To evaluate our approach, we analyze the resulting summaries, from both approaches, using BLEU, BERT-Score, and ROUGE-L metrics. Additionally, we assess the completeness of the summaries through manual review and employ LLMs as judges to evaluate summaries’ quality based on coherence, fluency, conciseness, and correctness. We aim to enhance the clarity and usability of clinical records by systematically examining how highlighting input notes affects the performance of a fine-tuned LLaMA2-13B model in discharge note summarization. This, in turn, can support better healthcare decision-making and improve patient outcomes.

To guide this investigation, we address the following research questions. (1) Does incorporating automatically highlighted detailed information into the fine-tuning data improve the quality of discharge note summaries generated by LLaMA2-13B? (2) How does highlighting affect different dimensions of summary quality, including semantic similarity (BERTScore), content overlap (ROUGE-L, BLEU), factual consistency (SummaC-CONV), and completeness? (3) Does highlighted fine-tuning also lead to perceptibly higher-quality summaries when evaluated by LLM-based judgments?

We selected LLaMA-2-13B for this study for three reasons. First, prior benchmark results on the MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset show that fine-tuned LLaMA-2-13B outperforms other open-source models, including Clinical-T5-Large and FLAN-UL2, and achieves performance closest to proprietary GPT-4 [28]. Second, LLaMA-2-13B offers an optimal balance between model size and computational feasibility for local fine-tuning on protected clinical data, whereas newer models (e.g., LLaMA-3 and Qwen [36]) require substantially more resources for reproducible fine-tuning.

2. Background

2.1. Text Summarization and Related Work

Text summarization techniques can be broadly classified into three categories: extractive summarization, abstractive summarization, and LLM-based summarization [37].

Extractive summarization [38] selects key sentences or phrases directly from the original text without modifying their wording. It relies on ranking mechanisms to identify the most informative parts of the content. However, such techniques contend with some disadvantages, including a potential lack of coherence, as extracted sentences may not flow naturally, and the inability to paraphrase or generalize information [37].

Unlike extractive methods, abstractive summarization [39] generates new text that conveys the key ideas of the original content in a more concise and coherent manner. It offers enhanced fluency and improved contextual understanding, but it also carries the risk of introducing factual inconsistencies, increasing computational costs, and requiring large-scale training datasets to ensure accuracy [37].

With the advent of LLMs, and due to their strong performance in summarization tasks [7,40,41,42], there has been a significant shift toward using LLMs for text summarization. LLM-based summarization utilizes pre-trained transformer models to generate summaries based on prompts or fine-tuning. These models can perform both extractive and abstractive summarization, adapting their output based on the task requirements. As a result, numerous research efforts have focused on developing automated summarization methods for medical texts.

Five LLMs were tested in generating summaries for discharge notes using MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset [28]. The study covers both open-source models (Clinical-T5-Large, FLAN-UL2, and Llama2-13B) and proprietary models (GPT-3.5 and GPT-4). These models were adapted using different strategies, including fine-tuning and in-context learning. The results showed that fine-tuned Llama2-13B achieved the best performance among open-source models based on quantitative metrics such as BLEU and BERT-Score. However, GPT-4 with in-context learning demonstrated the most robustness across varying input lengths and was preferred over human summaries in a clinical reader study, where five clinicians compared its summaries to those written by human experts. The results also emphasized that while open-source models like Llama2-13B performed well and could match human-written summaries, proprietary models, like GPT-4, had a clear edge in producing summaries that clinicians preferred.

Furthermore, a framework for radiology report summarization, using ChatGPT-3.5, has been proposed [41]. In-context learning and iterative optimization were used to improve the Automatic Impression Generation (AIG) task, which involves summarizing the “Findings” section of a radiology report into the “Impression” section. Instead of fine-tuning the model, prompts using similar reports retrieved via a similarity search technique were dynamically constructed. These retrieved examples provide contextual information, allowing ChatGPT to better generate relevant summaries. The method was evaluated on MIMIC-CXR and OpenI datasets, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance in radiology report summarization without requiring additional training data.

Finally, a system for EHR summarization, using the Google Flan-T5 model, has also been proposed [2] to generate clinician-focused summaries based on clinician-specified topics. Flan-T5 were fine-tuned on an EHR question-answering dataset formatted in the Stanford Question Answering Dataset (SQuAD) style. The fine-tuning process utilized the Seq2SeqTrainer from the Hugging Face Transformers library [43], with optimized hyperparameters to enhance performance. The results achieved are an Exact Match (EM) score of 81.81%, ROUGE scores (ROUGE-1: 96.03%, ROUGE-2: 86.67%, ROUGE-L: 96.10%), and a BLEU score of 63%.

Recent work in clinical NLP has also explored knowledge-guided summarization methods that use clinical concepts, ontologies, or highlight signals to guide LLMs [44,45,46,47]. Examples include models that use Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) [48] or SNOMED tags [49], entity-aware attention, or concept constraints to reduce hallucinations and improve factual accuracy. Highlight-based approaches mark details of the note to steer the model toward clinically relevant content. Our study builds on this line of work by examining whether automatically generated highlights, using CIT, can be incorporated directly into the fine-tuning process to improve summarization quality.

2.2. Dataset

The MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset [28,29] is a collection of Brief Hospital Course (BHC) summaries paired with their corresponding discharge notes extracted from the MIMIC-IV-Note database [50,51]. MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC is created by preprocessing discharge summaries from MIMIC-IV-Note, which contains 331,794 de-identified clinical notes from 145,915 patients admitted to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center between 2008 and 2019. Both datasets are hosted on PhysioNet [29,50] and can be accessed after signing a Data Use Agreement and completing the required training. The collection of patient information and the creation of these research resources were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) [52] at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, which granted a waiver of informed consent and approved the data-sharing initiative.

The MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset is designed to facilitate research on hospital course summarization, addressing the challenge of extracting concise and relevant information from lengthy clinical narratives. This dataset covers a diverse patient population reflective of the broader MIMIC-IV cohort, which includes various age groups, genders, and medical conditions.

To create the MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset, the MIMIC-IV notes are preprocessed through tokenization, section identification, normalization, and cleaning. This process separated the BHC from the rest of the clinical note.

To validate data quality, a manual review of 100 randomly sampled clinical notes was conducted and a clinical team reviewed 30 note–summary pairs, reporting no significant issues with the extracted content.

The MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset, consisting of 270,033 discharge note–BHC pairs, contains the columns note_id, input, target, input_tokens, and target_tokens. Note_id is the unique identifier for each row in the dataset, which matches the note_id column from the original MIMIC-IV-Note dataset. The input field includes preprocessed discharge note texts excluding the BHC section. The target field includes the standardized and cleaned BHC text, providing a concise summary of the patient’s hospital course. Input_tokens and target_tokens columns store the tokenized lengths of the clinical notes and BHC summaries.

2.3. Automatic Highlighting

In our previous work [33,34,35], we presented a multi-stage method for curating Cardiology Interface Terminology (CIT), tailored through an automatic method for highlighting information in discharge notes of cardiology patients. Highlighting details in discharge notes enables fast skimming, enhances summarization and simplification, and improves research and interoperability [3,32,33,34,35,53,54,55,56]. This process of CIT curation consists of two main phases. In the first stage, we constructed an initial version of the CIT, referred to as ICIT, by incorporating concepts from 11 cardiology-related subhierarchies of SNOMED CT [57]. However, ICIT alone did not sufficiently capture all detailed information present in the discharge notes. To address this, in the second stage, we employed a semi-automatic, iterative approach to enrich ICIT. Specifically, we mined fine-granularity phrases from discharge notes that contained ICIT concepts. All the mined phrases are reviewed both automatically and manually, and the legitimate ones are added to CIT, forming a new version of CIT. All the illegitimate phrases, structurally or semantically, are added to a reject list (R). In each iteration, we used the latest version of CIT to highlight the build dataset and evaluated its performance by measuring two metrics: coverage and breadth. Coverage is defined as the percentage of total number of words highlighted in a note; and breadth is defined as the average number of words of highlighted concepts.

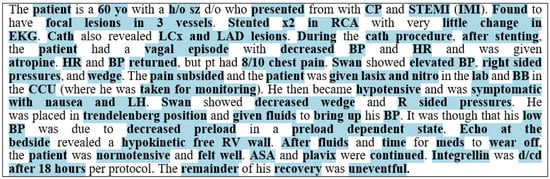

This iterative process continued until further improvements in coverage became negligible. The output of the second stage serves as the training data for the third stage. All concepts included in the resulting CIT at the end of stage two were considered as positive samples (labeled as 1), while all phrases in the rejection list R were considered as negative samples (labeled as 0). The third stage proceeded as follows: first, we embedded the labeled phrases of training data using Clinical BioBERT [58], and then we trained a neural network (NN) classifier on the embedded dataset. After conducting a grid search [59] to fine-tune the hyperparameters, we ended up having an NN model consisting of a single hidden layer with 100 neurons, ReLU activation function [60], and Adam optimizer [61]. Once trained, the model was used to classify newly extracted phrases from discharge notes as either legitimate concepts or illegitimate phrases. Phrases classified as legitimate were added to CIT, resulting in the final terminology, referred to as CITML. CITML demonstrated a coverage of 74.21% and a breadth of 1.68 for the test dataset. Figure 1 shows an excerpt of a discharge note highlighted by CITML, with information highlighted in blue background color.

Figure 1.

An excerpt of a discharge note highlighted by CITML with coverage of 68.01% and breadth of 1.8.

3. Method

For this study, we fine-tuned two variants of the LLaMA 2 (13B) model separately: one using highlighted discharge notes, which we refer to as H-LLaMA, and the other one using the same notes without highlighted content, which we refer to as U-LLaMA. Fine-tuning was performed on the High-Performance Computing (HPC) cluster at the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), located in Newark, NJ, USA. The fine-tuning procedure was identical in both settings, with the only difference being whether the input included highlighted information. We will delve into the details of data preparation and the fine-tuning procedure in the following sections.

3.1. Data Preparation

As described in the Section 2, the MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset consists of clinical note–summary pairs, where each pair represents a complete discharge note text and its corresponding condensed BHC summary. Each row in this dataset includes a note_id which is a unique identifier matching the note_id column from the original MIMIC-IV-Note database.

In our previous work, we developed CIT to highlight the detailed information of discharge notes of cardiology patients. Therefore, to identify cardiology-related records in MIMIC-IV-Note, we focused on two Intensive Care Units (ICUs) associated with cardiology: Coronary Care Unit (CCU) and Cardiac Vascular Intensive Care Unit (CVICU). We queried the “discharge” table in MIMIC-IV-Note for patients admitted to CCU or CVICU. This resulted in approximately 18,600 records, from which we extracted their note_id values. Next, we filtered MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC to retain only the rows where the note_id matched those from patients admitted to CCU or CVICU in MIMIC_IV. This resulted in approximately 14,000 records.

From the 14,000 cardiology-related records, we randomly selected 1000 records for fine-tuning the model, which we refer to as training data, and another 100 records for evaluating summaries generated by the fine-tuned model, which we refer to as test data.

We have highlighted the discharge notes of training data and test data using the automatic highlighting method we proposed and reported on in [33,34,35], which automatically generates highlights for each note into an HTML file. The highlighted information is enclosed in <span> tags with the background color #ADD8E6. To prevent the model from being confused by HTML tags, each HTML file was converted into plain text, and the highlighted information was enclosed within square brackets (‘[’ and ‘]’). The brackets are treated as additional tokens by the tokenizer, allowing the model to learn that bracketed spans correspond to clinically important information rather than noise, consistent with our earlier findings.

Please note that although multiple CIT concepts may overlap in the raw terminology, text highlighting by nature cannot display overlapping or nested mappings. Therefore, in such cases, we must choose one of the potential CIT concept mappings for the highlight. In [3,62], we describe an algorithm that selects a highlight which maximizes the coverage and breadth measures. This approach prioritizes longer, multi-word concepts, as they tend to better capture the semantics of the sentence.

We prepared four datasets for model training and evaluation:

Unhighlighted Training Set (UTrain): This set consists of 1000 original discharge notes without any highlighted information, each paired with its corresponding BHC summary.

Unhighlighted Test Set (UTest): This set includes 100 original, unhighlighted discharge notes along with their corresponding BHC summaries and was used for evaluation purposes.

Highlighted Training Set (HTrain): This set contains the same 1000 discharge notes, those used in UTrain, but with detailed information highlighted. The highlighted content was enclosed within square brackets (‘[’ and ‘]’). Each note is paired with its corresponding BHC summary.

Highlighted Test Set (HTest): This set includes 100 discharge notes, the same ones used in UTest, with highlighted information enclosed within square brackets. Each note is paired with its associated BHC summaries.

We converted both UTrain and HTrain into JSON format. Each training example was represented as a JSON object with three fields, “instruction”, “input”, and “output”, resulting in two separate JSON datasets.

The UTrain dataset used the instruction: “Summarize the clinical note into a brief hospital course.”

The HTrain dataset used the instruction: “Summarize the clinical note into a brief hospital course, focusing on the information enclosed within ‘[’ and ‘]’.”

For both datasets, the prompt (i.e., instruction + input) and the output (i.e., BHC) were tokenized, concatenated, and padded or truncated to a fixed length of 4096 tokens. As in MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset, the input token length averaged 2267 ± 914 and the output token length averaged 564 ± 410 [29], the combined prompt and output length typically remained within this limit, and truncation was rarely needed.

3.2. Fine-Tuning Procedure

For fine-tuning, we used the HuggingFace Transformers library [43] in combination with PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning) [63] and LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) [64]. The model was initialized from a pre-trained LLaMA-2 13B checkpoint in HuggingFace format. The tokenizer was also loaded from the same checkpoint and extended to include the custom discharge note section tags. Special tags of the input discharge notes such as <SEX>, <SERVICE>, <ALLERGIES>, <CHIEF COMPLAINT>, etc., were explicitly added to the tokenizer as special tokens. These tags preserved semantic structure and helped guide the model’s understanding of discharge note organization.

The model was fine-tuned on our institution’s High-Performance Computing (HPC) cluster. Jobs were executed using a SLURM scheduler on a single computer node configured with 2 NVIDIA GPUs, 66 CPU cores, and 256 GB RAM. This environment ensured secure, local processing of clinical text and provided sufficient computational resources for stable fine-tuning of the 13B-parameter LLaMA-2 model. Fine-tuning was performed using LoRA with rank = 8, α = 32, and dropout = 0.10. LoRA adaptation was applied specifically to the query and value projection layers of the attention mechanism, referred to as q_proj and v_proj in the model implementation. Training was conducted for nine epochs using the AdamW optimizer [65] with a learning rate of 2 × 10−4 and weight decay of 0.005. We used a per-device batch size of 5, and gradient accumulation over 8 steps. The dataset was split into 90% for training and 10% for evaluation.

The selected hyperparameters were chosen based on established best practices for fine-tuning LLaMA-2 models and to ensure stable training on long clinical notes. LoRA settings (rank = 8, α = 32, dropout = 0.10) follow commonly adopted configurations shown to balance parameter efficiency and preservation of base-model knowledge in prior clinical NLP studies [66,67,68]. The learning rate (2 × 10−4), weight decay (0.005), and batch/gradient accumulation settings were selected after small-scale exploratory runs that demonstrated stable loss curves without overfitting. While more extensive hyperparameter tuning is possible, it is computationally expensive for 13B-parameter models and was beyond the scope of this study.

3.3. Generating Summary from Fine-Tuned Models

After fine-tuning, each of the two fine-tuned LoRA adaptors were separately merged with the base LLaMA-2 13B model to produce standalone fine-tuned models for inferences. Inferences used generation prompt structures consistent with the training format. Following best practices in recent clinical text generation literature [69,70,71], inference was performed using nucleus sampling [72] with temperature = 0.7 and top-p = 0.9. We refer to the summaries generated by U-LLaMA as U-summaries, and those from H-LLaMA as H-summaries.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

Evaluation involves assessing the quality of the generated summaries in relation to the golden standard summary, in this case, BHC. Summaries should be evaluated from different perspectives. In most related studies, extensive manual work has been conducted to assess summary quality alongside automatic metrics. We performed evaluation in three different categories:

Manual evaluation, automatic evaluation, and LLM-based evaluation. Automatic and LLM-based evaluations were conducted on all 100 notes in the test dataset, and a manual evaluation was performed on a random subset of 40 notes.

3.4.1. Manual Evaluation

Completeness: Measures how well the summary captures the information from the reference BHC summary. A high completeness score means the summary includes more information with fewer missing critical details. Completeness is calculated using Equation (1).

We evaluate the completeness of the generated summaries based on the reference summary, rather than the entire discharge note. This is because much of the information in the discharge note is not expected to appear in the summary. When gold-standard reference summaries are available, we assume that only the information contained in the reference summary is necessary to include in the generated summary.

3.4.2. Automatic Evaluation

BERTScore: BERTScore [73] uses contextual embeddings from a pre-trained BERT model to compute semantic similarity between the generated and reference summaries. Unlike traditional n-gram overlap methods, BERTScore compares the similarity of words in the generated and reference texts based on their meaning rather than exact word matches.

BERTScore provides three main scores:

Precision: How much of the generated text is semantically supported by the reference.

Recall: How much of the reference is captured by the generated text.

F1 score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, often used as the main BERTScore. In this study we also report F1 score as the BERTScore.

ROUGE-L (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation—Longest Common Subsequence): ROUGE metrics [74] measures how much of the reference summary appears in the generated summary by measuring the overlap of n-grams, word sequences, and longest common subsequences between the generated summary and reference summaries. One common variant of ROUGE is ROUGE-L, which measures the longest common subsequence to capture fluency and coherence. Its ability to reflect holistic similarity rather than just local n-gram matches makes it more suitable for evaluating summary-level similarity.

BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy): BLEU metric [75] measures how much of the generated summary appears in the reference summary by measuring n-gram overlap between the generated summary and reference summary. BLEU is widely used for assessing machine translation and text generation tasks, including summarization.

Sumac_CONV: SummaC-CONV [76], specifically designed for the summarization task, is a factual consistency evaluation metric that leverages Natural Language Inference (NLI) [77] to assess whether a generated summary is factually consistent with its reference text. Unlike naive sentence-level approaches, SummaC-CONV does not assume a one-to-one alignment between source and summary sentences. Instead, it compares each summary sentence with multiple relevant sentences from the reference text, aggregating entailment scores. By mapping each summary sentence to multiple sentences, it correctly evaluates cases where multiple facts are summarized into a single sentence or appear in a different order than in the original document.

3.4.3. LLM-Based Evaluation

LLMs have shown great potential as evaluators for LLM-generated summaries, evaluating various aspects of the generated texts [78,79]. In this study, we use ChatGPT 4o (through Azure) to evaluate generated summaries of each discharge note. We crafted and refined a prompt to instruct ChatGPT 4o to evaluate each summary based on four criteria, and then assign a score from 1 to 5 for each, where 1 indicates the lowest and 5 the highest. Here is the final version of the prompt:

“Act as a cardiologist and read a discharge note (A) alongside its reference summary (B) and two LLM-generated summaries (C and D). Your task is to grade both summaries on a scale of 1 to 5 for the following four metrics:

Coherence: Does the summary maintain a logical flow of ideas and present information clearly?

Fluency: Is it grammatically well-formed and easy to read?

Conciseness: Does it effectively condense information, keeping only the most relevant clinical details?

Correctness: Does the summary accurately reflect the content of the discharge note (A) and the reference summary (B), without introducing false or misleading information?

Assign a score (1–5) for each metric for both summaries (C and D). A score of 1 indicates the lowest quality, while 5 indicates the highest.”

4. Results

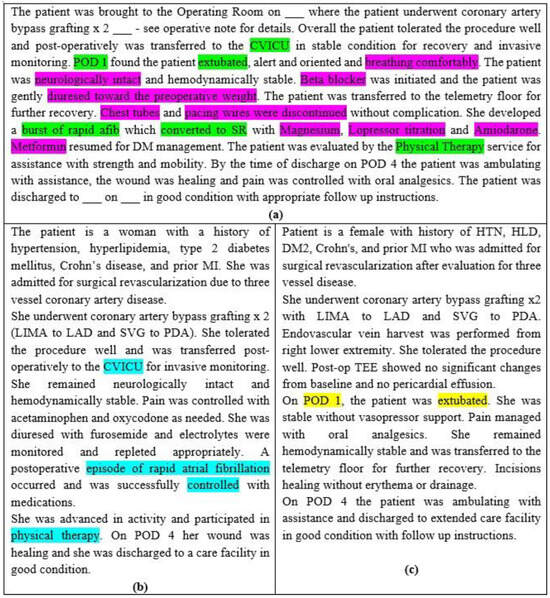

Figure 2a shows an example of a BHC summary of one discharge note, containing 181 words, alongside the H-summary (Figure 2b) and U-summary of its corresponding discharge note (Figure 2c), which contain 126 and 135 words, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) A BHC summary with 181 words, (b) the H-summary of the corresponding discharge note with 135 words and 56.5% completeness, BERTScore 67.7, ROUGE-L 38.2, BLEU 13.9, and Sumac_CONV 61.4, (c) the U-summary of the same note with 126 words and 47.8% completeness, BERTScore 66.1, ROUGE-L 33.4, BLEU 12.2, and Sumac_CONV 34.7. Green highlights in (a) indicate the information appeared in one of (b) or (c). The pink highlight in (a) indicates missed information in both summaries. The blue highlight in (b) indicates information form (a) that is missing in (c). The yellow highlights in (c) indicate information items from (a) that are missing in (b).

In this example, six key pieces of information are highlighted in green in Figure 2a. Among these green highlights, the blue highlights in Figure 2b indicate information that is present in the original note (Figure 2a) but missing from the U-summary (Figure 2c). Conversely, yellow highlights denote information present in the U-summary (Figure 2c) but absent from the H-summary (Figure 2b). Pink highlights in Figure 2a indicate information that does not appear in either summary. All unhighlighted pieces of information in (Figure 2a) correspond to information that appears in both summaries. The H-summary achieves a completeness score of 56.6%, while the U-summary achieves a completeness score of 47.8%.

Manual Evaluation: For random 40 notes, the average completeness of the U-summaries is 47.6%, while the H-summaries demonstrated a higher average completeness of 54.8%, an increase of 6 percentage points. Additionally, for 33 notes, the completeness of the H-summary is higher than the corresponding U-summary, for 4 notes, the completeness is equal, and for 3 notes, the completeness of U-summary is higher. Using Fisher Exact test [80,81], we compared the completeness of H-summary group (33 notes) and the U-summary group (7 notes) with a significance level of 0.05. The statistical value was less than 0.00001, indicating a statistically significant result (p < 0.05).

Automatic evaluation: As shown in Table 1, the average BERTScore of the U-summaries for 100 notes is 59.61, while that of the H-summaries is 63.75, with 91 notes having higher BERTScore for H-summaries than U-summaries. Using Fisher Exact test, we compared the BERTScore of H-summary group (91 notes) and the U-summary group (9 notes) with a significance level of 0.05. The statistical value was less than 0.00001, indicating a statistically significant result (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

The average results of automatic evaluations for U_summaries (U_S) and H_summaries (H_S).

The average ROUGE-L score for the U-summaries is 21.82, whereas it is 23.43 for the H-summaries, with 90 notes having higher ROUGE-L score for H-summaries than U-summaries. Using Fisher Exact test, we compared the ROUGE-L score of H-summary group (90 notes) and the U-summary group (10 notes) with a significance level of 0.05. The statistical value was less than 0.00001, indicating a statistically significant result (p < 0.05).

Also, the average BLEU score of the U-summaries is 8.41, compared to 10.4 for the H-summaries, with 81 notes having higher BLEU score for H-summaries than U-summaries. Using Fisher Exact test, we compared the BLEU score of H-summary group (81 notes) and the U-summary group (19 notes) with a significance level of 0.05. The statistical value was less than 0.00001, indicating a statistically significant result (p < 0.05).

Finally, the average Sumac_CONV score is 40.2 for the U-summaries and 67.7 for the H-summaries, with 98 notes having higher Sumac_CONV score for H-summaries than U-summaries. Using Fisher Exact test, we compared the Sumac_CONV score of H-summary group (98 notes) and the U-summary group (2 notes) with a significance level of 0.05. The statistical value was 0.0002, indicating a statistically significant result (p < 0.05).

LLMs evaluation: ChatGPT 4o generally rated both U_summaries and H_summaries highly across all four criteria (Coherence, Fluency, Conciseness, and Correctness), indicating that both types of summaries are overall well written. However, H_summaries received slightly higher average scores than U_summaries across three criteria (Coherence, Conciseness, and Correctness), and for Fluency, the averages were almost equal.

The average scores for Coherence are 4.84 (U_summaries) and 4.91 (H_summaries), for Fluency are 4.91 (U_summaries) and 4.92 (H_summaries), for Conciseness are 4.65 (U_summaries) and 4.81 (H_summaries), and for Correctness are 4.79 (U_summaries) and 4.91 (H_summaries). When considering the overall average across all criteria, H_summaries scored 4.88, slightly outperforming U_summaries, which scored 4.79.

Also, as shown in Table 2, the average length of BHC summaries for these 100 notes is 393.19, while the average length of U-summaries is 300.38 and that of H-summaries is 331.67, indicating that H-summaries tend to include more information.

Table 2.

The results of LLM evaluation for U_summaries (U_S) and H_summaries (H_S).

5. Discussion

In this study, we fine-tuned LLaMA 2 (13B) twice, separately, under the same conditions: once using unhighlighted discharge notes and once more using the same notes but highlighted. By keeping everything else constant, we aimed to isolate and measure the effect of highlighting on fine-tuning. Results (Table 3) show that using highlighted discharge notes for fine-tuning improves the quality of the generated summaries compared to fine-tuning with unhighlighted notes across all evaluation metrics. For the completeness, BERTScore, ROUGE-L, BLEU, and SummaC_CONV metrics, we achieved a statistical significance of (p < 0.05) using Fisher Exact test with a significance level of 0.05.

Table 3.

Minimum, maximum, and standard deviation for evaluation metrics for U_summaries (U_S) and H_summaries (H_S).

While the improvements in ROUGE-L and BLEU (lexical similarity measures) and BERTScore (a semantic similarity measure) are numerically modest, the much larger gain in SummaC_CONV suggests that highlighting may have a stronger effect on improving factual correctness than on general similarity. SummaC_CONV assesses whether a summary omits or contradicts clinical details, which may explain why it shows a clearer distinction between the two models.

For statistical testing, we converted each metric into a per-note comparison (whether the H-summary scored higher than the U-summary for that specific note) and applied Fisher Exact test to the resulting win/loss counts. We chose this approach because it makes no assumptions about score distributions and is reliable for small sample sizes. However, we acknowledge that this method is less conventional for continuous metrics such as BERTScore or ROUGE, because it only captures whether H > U, not how large the difference is. Therefore, the test reflects consistency of improvement rather than effect size. Even so, the overall conclusion is unchanged when looking directly at the average scores and the large number of per-note wins, which both strongly favor the highlighted model.

In our previous study [32], we demonstrated that summarizing discharge notes with highlighted information, using a prompt engineering strategy, improves the accuracy of summaries compared to summarizing unhighlighted discharge notes. Unlike our previous work, where highlighting was provided only at inference time through the prompt, the present study incorporates highlight signals directly into the fine-tuning data. This allows the model to internalize and learn from highlighted patterns during training, rather than relying solely on external prompt cues. Demonstrating improvements under this training regime shows that highlight information is beneficial not just as contextual guidance during prompting, but also as an embedded feature that shapes the model’s learned representation.

The BHC section in discharge notes offers a concise narrative of the patient’s clinical journey. Composing this section is widely recognized as a cognitively demanding and time-intensive task for clinicians since it requires synthesizing a large volume of notes and reports generated throughout the patient’s hospitalization into a coherent summary [82,83]. This process is not only laborious but also susceptible to errors, given the high documentation burden [82,84]. Furthermore, BHCs exhibit significant variability in both style and content. Authored by different clinicians, they reflect diverse writing habits, and they frequently alternate between extractive and abstractive summarization strategies [83]. Prior research has shown that discharge summaries and their BHC sections may omit critical information or introduce excessive, redundant, or even erroneous content [84,85]. Also, sometimes new or summary-only information is added to BHC that are not documented elsewhere clearly.

Although BHCs are commonly used as reference summaries for training summarization models, they are inherently noisy. Their variability in coherence, completeness, and potential misrepresentation of clinical facts introduce significant challenges for model training and evaluation [83,85]. After reviewing several examples, we noted that some BHCs are very short, shallow, and lack important details, while others are overly long and include too much information. There is no consistent structure or style among them. Indeed, the BHC targets have a mean token length of 564 with a standard deviation of 410 [29], which is notably high, indicating substantial variation in target length. This inconsistency makes it harder for the language model to learn what kind of summary it is supposed to generate. If all BHCs followed a similar pattern, both the highlighted and unhighlighted models would have a clearer target during training.

Another factor that impacts the quality of the generated summaries is the presence of errors or mismatches between the original discharge notes and their corresponding BHCs. In some cases, the BHC includes information that does not appear in the original note. For example, in note “11874424-DS-9,” the “atorvastatin 80 mg” is mentioned in the BHC, but the original discharge note only refers to a prior dose of atorvastatin 40 mg, with no indication of a change to 80 mg. Similarly, the original note states that the patient was accompanied by his son, while the BHC refers to a daughter. These kinds of inaccuracies or additions in the BHCs negatively affect the quality of the summaries generated by the LLM. Since the model generates summaries based only on the original note, it should not include information that was never there. As a result, when these summaries are evaluated against BHCs, the evaluation scores decrease, not because the model failed, but because the reference summaries are flawed.

While LLM-based evaluation provides a scalable and cost-effective complement to manual review, it also introduces potential biases and limitations, particularly in clinical or safety-critical domains. LLMs may overestimate summary quality because they are sensitive to fluency and coherence, sometimes rewarding well-written text even when factual omissions are present. Their judgments can also reflect the biases of the underlying training data or misinterpret specialized clinical details. Furthermore, LLMs may implicitly favor summaries that resemble their own generative style, creating an alignment bias rather than an objective assessment. For these reasons, LLM-based scores should be interpreted as supportive evidence rather than definitive clinical validation, and future work should incorporate more extensive clinician-based evaluation to mitigate these limitations.

This work should be interpreted as a proof-of-concept study rather than a full-scale evaluation. The training set (1000 notes) and test set (100 notes) are relatively small compared to the full MIMIC-IV corpus and come exclusively from cardiology units (CCU and CVICU). This domain specificity limits the ability to generalize findings to other specialties, where documentation patterns, terminology, and summary structures may differ substantially. The reduced dataset size also increases the risk of overfitting, even with parameter-efficient fine-tuning, and may amplify the influence of noise or inconsistencies in the BHC targets. Therefore, while the observed improvements from highlighted fine-tuning are robust within this subset, broader validation across larger and more diverse clinical domains is necessary to assess generalizability.

Future work: For future work, we plan to fine-tune the model using a larger dataset and to reduce variability in the training data. In particular, we will stratify samples based on the BHC-to-note length ratio or other style consistency criteria, allowing us to select example BHCs that follow a more uniform structure. This will help reduce heterogeneity, improve representativeness, and make it easier to evaluate model performance. We also aim to conduct a preliminary evaluation of BHCs using LLMs, assessing them based on their corresponding discharge notes to determine which are more comprehensive and less erroneous. This evaluation will help identify BHCs suitable to serve as gold-standard summaries. BHCs with higher ratings, along with their corresponding discharge notes, form the training dataset for fine-tuning the model. We also plan to conduct a hybrid training where we fine-tune LLaMA using a mixed dataset that includes both highlighted and non-highlighted inputs. This will allow us to observe how the model behaves when trained with both types of data. Also, we plan to increase the test set for manual evaluation to 100 notes in order to achieve a more accurate assessment. Additionally, the clinical significance of the observed metric improvements remains uncertain, and future work will include clinician-based evaluation and deeper analysis of why factual consistency measures show larger gains than lexical overlap or semantic similarity metrics.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates the effect of highlighting information in discharge notes on the summaries generated by Large Language Models (LLMs). Highlighting is performed automatically using a Cardiology Interface Terminology (CIT) proposed in our previous work. To carry out our experiment, we fine-tuned the LLaMA2-13B model twice using the MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC dataset: once with the highlighted discharge notes and once more with the same set of discharge notes without highlighting.

Our results demonstrate that incorporating highlighted information into the fine-tuning process improves the quality of discharge note summarization. That is, summaries generated from highlighted inputs consistently outperformed those from unhighlighted inputs across all evaluation metrics, including BERTScore, ROUGE-L, BLEU, SummaC_CONV, completeness, and LLM-based judgments.

This work provides a scalable framework for improving discharge notes’ summarization using fine-tuned LLMs. By enhancing the clarity and completeness of clinical summaries, this approach has the potential to support more effective healthcare delivery and better informed decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.H.D.; methodology, M.K.H.D.; software, M.K.H.D.; validation, M.K.H.D.; data curation, M.K.H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.H.D.; writing—review and editing, M.K.H.D., Y.P., F.P.D., H.L.; supervision, Y.P.; project administration, Y.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The code used for fine-tuning the LLaMA 2–13B model is publicly available at: https://github.com/mahshadkoohihd/Fine_tuning_LLaMA2 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Menachemi, N.; Collum, T.H. Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2011, 4, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madzime, R.; Nyirenda, C. Enhanced Electronic Health Records Text Summarization Using Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.09628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, H.; Sen, P.; Perl, Y.; Dehkordi, M.K. CFC annotator: A cluster-focused combination algorithm for annotating electronic health records by referencing interface terminology. In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025), Porto, Portugal, 19–21 February 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S. Impact of electronic health record systems on information integrity: Quality and safety implications. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2013, 10, 1c. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, A.S.; Grossman, J.M.; Cohen, G.R.; Kemper, N.M.; Pham, H.H. Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apathy, N.C.; Rotenstein, L.; Bates, D.W.; Holmgren, A.J. Documentation dynamics: Note composition, burden, and physician efficiency. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Ting, D.S.J.; Elangovan, K.; Gutierrez, L.; Tan, T.F.; Ting, D.S.W. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi, M.U.; Qureshi, R.; Shah, A.; Irfan, M.; Zafar, A.; Shaikh, M.B.; Akhtar, N.; Wu, J.; Mirjalili, S. A survey on large language models: Applications, challenges, limitations, and practical usage. Authorea Prepr. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwag, K.H.; González-Lorenzo, M.; Banzi, R.; Bonovas, S.; Moja, L. Providing doctors with high-quality information: An updated evaluation of web-based point-of-care information summaries. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestov, A.; Levichev, R.; Mussabayev, R.; Maslov, E.; Zadorozhny, P.; Cheshkov, A.; Mussabayev, R.; Toleu, A.; Tolegen, G.; Krassovitskiy, A. Finetuning large language models for vulnerability detection. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 38889–38900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallapalli, S.; Gallagher, S.; Mellinger, A.O.; Ratchford, J.; Sinha, A.; Brooks, T.; Nichols, W.R.; Winski, N.; Brown, B. Fine-Tuning LLMs for Report Summarization: Analysis on Supervised and Unsupervised Data. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.10676. [Google Scholar]

- Pivovarov, R.; Elhadad, N. Automated methods for the summarization of electronic health records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzynski, E.; Hashmi, H.; Subramanian, J.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Polverento, M.; Simmons, M.; Brooks, K.; Given, C. Opportunities to improve clinical summaries for patients at hospital discharge. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.A.; Schwartz, B.S.; Stewart, W.F.; Adler, N.E. Using electronic health records for population health research: A review of methods and applications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2016, 37, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-K.; Chen, M.; Li, W.; Wang, R.; Lu, L.; Liu, J.; Hwang, K.; Hao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Meng, Q. LLM Fine-Tuning: Concepts, Opportunities, and Challenges. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; He, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, C.; King, I. Mitigating large language model hallucination with faithful finetuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.11267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumiantsau, M.; Vertsel, A.; Hrytsuk, I.; Ballah, I. Beyond Fine-Tuning: Effective Strategies for Mitigating Hallucinations in Large Language Models for Data Analytics. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.20024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, K.; Zhou, Q.; Duan, Y.; Shu, J.; Kan, H.; Gu, Z.; Hu, J. CPMI-ChatGLM: Parameter-efficient fine-tuning ChatGLM with Chinese patent medicine instructions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzah, F.; Sulaiman, N. Optimizing Llama 7B for Medical Question Answering: A Study on Fine-Tuning Strategies and Performance on the MultiMedQA Dataset. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/osf/g5aes_v1 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Li, I.; Pan, J.; Goldwasser, J.; Verma, N.; Wong, W.P.; Nuzumlalı, M.Y.; Rosand, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chang, D. Neural natural language processing for unstructured data in electronic health records: A review. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2022, 46, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perković, G.; Drobnjak, A.; Botički, I. Hallucinations in llms: Understanding and addressing challenges. In Proceedings of the 2024 47th MIPRO ICT and Electronics Convention (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 20–24 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S.; Jha, S.K.; Lincoln, P.; Bastian, N.D.; Velasquez, A.; Neema, S. Dehallucinating large language models using formal methods guided iterative prompting. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Assured Autonomy (ICAA), Laurel, MD, USA, 6–8 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, V.B.; Zafar, A.; Khan, A.; Shahid, A. The ultimate guide to fine-tuning llms from basics to breakthroughs: An exhaustive review of technologies, research, best practices, applied research challenges and opportunities. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.N.; Liu, Y.; Khan, K.; Jiang, T.; Burhan, U. BIR: Biomedical Information Retrieval System for Cancer Treatment in Electronic Health Record Using Transformers. Sensors 2023, 23, 9355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Pfaff, E.; Guo, S.J.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tao, C.; Stiglic, G.; Bian, J. Enriching real-world data with social determinants of health for health outcomes and health equity: Successes, challenges, and opportunities. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2023, 32, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdik, Z.P.; Graham, S.S.; Shiva Edward, J.C.; Rodriguez, S.N.; Karnes, M.S.; Jensen, J.T.; Barbour, J.B.; Rousseau, J.F. Sample Size Considerations for Fine-Tuning Large Language Models for Named Entity Recognition Tasks: Methodological Study. JMIR AI 2024, 3, e52095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aali, A.; Van Veen, D.; Arefeen, Y.I.; Hom, J.; Bluethgen, C.; Reis, E.P.; Gatidis, S.; Clifford, N.; Daws, J.; Tehrani, A.S. A dataset and benchmark for hospital course summarization with adapted large language models. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2024, 32, ocae312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aali, A.; Van Veen, D.; Arefeen, Y.I.; Hom, J.; Bluethgen, C.; Reis, E.P.; Gatidis, S.; Clifford, N.; Daws, J.; Tehrani, A.S. MIMIC-IV-Ext-BHC: Labeled Clinical Notes Dataset for Hospital Course Summarization. 2024. Available online: https://physionet.org/content/labelled-notes-hospital-course/1.1.0/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Du, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chuang, Y.-W.; Yang, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Hong, P.; Bates, D.W. Generative large language models in electronic health records for patient care since 2023: A systematic review. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Shrestha, S.; Chen, A.; Conte, J.; Avramovic, S.; Sikdar, S.; Anastasopoulos, A.; Das, S. Clinical risk prediction using language models: Benefits and considerations. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2024, 31, ocae030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohi Habibi Dehkordi, M.; Perl, Y.; Deek, F.P.; He, Z.; Keloth, V.K.; Liu, H.; Elhanan, G.; Einstein, A.J. Improving Large Language Models’ Summarization Accuracy by Adding Highlights to Discharge Notes: Comparative Evaluation. JMIR Med. Inform. 2025, 13, e66476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dehkordi, M.K.H.; Einstein, A.J.; Zhou, S.; Elhanan, G.; Perl, Y.; Keloth, V.K.; Geller, J.; Liu, H. Using annotation for computerized support for fast skimming of cardiology electronic health record notes. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Istanbul, Turkey, 5–8 December 2023; pp. 4043–4050. [Google Scholar]

- Dehkordi, M.K.H.; Kollapally, N.M.; Perl, Y.; Geller, J.; Deek, F.P.; Liu, H.; Keloth, V.K.; Elhanan, G.; Einstein, A.J. Skimming of Electronic Health Records Highlighted by an Interface Terminology Curated with Machine Learning Mining. In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024), Rome, Italy, 21–23 February 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, M.K.; Kollapally, N.M.; Perl, Y.; Geller, J.; Deek, F.P.; Liu, H.; Keloth, V.K.; Elhanan, G.; Einstein, A.J. Curation of a Cardiology Interface Terminology for Highlighting Electronic Health Records using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024), Rome, Italy, 21–23 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Islam, S.; Datta, P.P.; Kabir, I.; Chowdhury, N.U.R.; Haque, A. Qwen 2.5: A comprehensive review of the leading resource-efficient llm with potentioal to surpass all competitors. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, D.; Wang, J.; Tan, J. A comprehensive survey on process-oriented automatic text summarization with exploration of llm-based methods. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.02901. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, M.; Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Qiu, X.; Huang, X. Extractive summarization as text matching. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.08795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.K. Abstractive summarization: An overview of the state of the art. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 121, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veen, D.; Van Uden, C.; Blankemeier, L.; Delbrouck, J.-B.; Aali, A.; Bluethgen, C.; Pareek, A.; Polacin, M.; Reis, E.P.; Seehofnerová, A. Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, F.; Jiang, X.; Guo, L.; Cai, X. An Iterative Optimizing Framework for Radiology Report Summarization with ChatGPT. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 4163–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hake, J.; Crowley, M.; Coy, A.; Shanks, D.; Eoff, A.; Kirmer-Voss, K.; Dhanda, G.; Parente, D.J. Quality, Accuracy, and Bias in ChatGPT-Based Summarization of Medical Abstracts. Ann. Fam. Med. 2024, 22, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M. Huggingface’s transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.03771. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z. Knowledge-guided aspect-based summarization. In Proceedings of the 2023 International conference on communications, computing and artificial intelligence (CCCAI), Shanghai, China, 23–25 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Duan, M.; Gong, P.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Han, B. Cross-modal knowledge guided model for abstractive summarization. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, S.; Guo, Y.; Kilicoglu, H. Towards Knowledge-Guided Biomedical Lay Summarization using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Patient-Oriented Language Processing (CL4Health), Albuquerque, NM, USA, 3–4 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-Y.; Chun, S.A.; Geller, J. Perspective-Based Microblog Summarization. Information 2025, 16, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenreider, O. The unified medical language system (UMLS): Integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D267–D270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, K. SNOMED-CT: The advanced terminology and coding system for eHealth. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 2006, 121, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.E.; Bulgarelli, L.; Shen, L.; Gayles, A.; Shammout, A.; Horng, S.; Pollard, T.J.; Hao, S.; Moody, B.; Gow, B. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.; Bulgarelli, L.; Pollard, T.; Horng, S.; Celi, L.A.; Mark, R. Mimic-iv. PhysioNet. 2020. Available online: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/1.0/ (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Grady, C. Institutional review boards: Purpose and challenges. Chest 2015, 148, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, M.K.H.; Zhou, S.; Perl, Y.; Deek, F.P.; Einstein, A.J.; Elhanan, G.; He, Z.; Liu, H. Enhancing patient Comprehension: An effective sequential prompting approach to simplifying EHRs using LLMs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Lisbon, Portugal, 3–6 December 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollapally, N.M.; Dehkordi, M.K.H.; Perl, Y.; Geller, J.; Deek, F.P.; Liu, H.; Keloth, V.K.; Elhanan, G.; Einstein, A.J.; Zhou, S. Using clinical entity recognition for curating an interface terminology to aid fast skimming of EHRs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Lisbon, Portugal, 3–6 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dehkordi, M.K.H.; Lu, J.; Perl, Y.; Deek, F.P. Enhancing Patient Comprehension of Discharge Notes with a Retrieval-Augmented LLM Approach. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Wuhan, China, 15–18 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dehkordi, M.K.H.; Perl, Y.; Deek, F.P. Optimizing Manual Review Using Machine Learning in Interface Terminology Curation for Automatic EHR Highlighting. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Wuhan, China, 15–18 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- SNOMED International Homepage. Available online: http://www.snomed.org/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Alsentzer, E.; Murphy, J.R.; Boag, W.; Weng, W.-H.; Jin, D.; Naumann, T.; McDermott, M. Publicly available clinical BERT embeddings. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.03323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liashchynskyi, P.; Liashchynskyi, P. Grid search, random search, genetic algorithm: A big comparison for NAS. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.06059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarap, A.F. Deep learning using rectified linear units (relu). arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.08375. [Google Scholar]

- Jais, I.K.M.; Ismail, A.R.; Nisa, S.Q. Adam optimization algorithm for wide and deep neural network. Knowl. Eng. Data Sci. 2019, 2, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Dehkordi, M.K.H.; Perl, Y.; Deek, F.P.; Liu, H. Enhancing Electronic Health Records Annotation with a Cluster-Focused Combination Algorithm and Interface Terminologies. In Springer Book of HEALTHINF, Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025), Porto, Portugal, 20–22 February 2025; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberger, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.Q. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for large models: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14608. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Llugsi, R.; El Yacoubi, S.; Fontaine, A.; Lupera, P. Comparison between Adam, AdaMax and Adam W optimizers to implement a Weather Forecast based on Neural Networks for the Andean city of Quito. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Fifth Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ETCM), Cuenca, Ecuador, 12–15 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Han, J.; Liu, C.; Gao, P.; Zhou, A.; Hu, X.; Yan, S.; Lu, P.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y. Llama-adapter: Efficient fine-tuning of language models with zero-init attention. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.16199. [Google Scholar]

- Gema, A.; Minervini, P.; Daines, L.; Hope, T.; Alex, B. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning of llama for the clinical domain. In Proceedings of the 6th Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop, Mexico City, Mexico, 21 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lermen, S.; Rogers-Smith, C.; Ladish, J. Lora fine-tuning efficiently undoes safety training in llama 2-chat 70b. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.20624. [Google Scholar]

- Koraş, O.A.; Bahnan, R.; Kleesiek, J.; Dada, A. Towards Conditioning Clinical Text Generation for User Control. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.17571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Lan, T.; Wang, Y.; Yogatama, D.; Kong, L.; Collier, N. A contrastive framework for neural text generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 21548–21561. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Yang, X.; Chen, A.; Smith, K.E.; PourNejatian, N.; Costa, A.B.; Martin, C.; Flores, M.G.; Zhang, Y.; Magoc, T. A study of generative large language model for medical research and healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, A.; Buys, J.; Du, L.; Forbes, M.; Choi, Y. The curious case of neural text degeneration. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09751. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. Bertscore: Evaluating text generation with bert. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09675. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text Summarization Branches Out; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.-J. Bleu: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–12 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Laban, P.; Schnabel, T.; Bennett, P.N.; Hearst, M.A. SummaC: Re-visiting NLI-based models for inconsistency detection in summarization. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2022, 10, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCartney, B. Natural Language Inference. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Cox, D.; Yang, Y.; Gan, C. Principle-driven self-alignment of language models from scratch with minimal human supervision. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36, 2511–2565. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Bhasuran, B.; Jin, Q.; Tian, S.; Hanna, K.; Shavor, C.; Arguello, L.G.; Murray, P.; Lu, Z. Quality of Answers of Generative Large Language Models vs Peer Patients for Interpreting Lab Test Results for Lay Patients: Evaluation Study. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.01693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, G.J. Fisher’s exact test. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1992, 155, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test, F.E. Fisher Exact Test. Available online: https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/fisher/default2.aspx (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Adams, G.; Zuckerg, J.; Elhadad, N. A meta-evaluation of faithfulness metrics for long-form hospital-course summarization. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, New York, NY, USA, 11–12 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, G.; Alsentzer, E.; Ketenci, M.; Zucker, J.; Elhadad, N. What’s in a summary? Laying the groundwork for advances in hospital-course summarization. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Virtual, 6–11 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, T.; Ibrahim, Z.; Teo, J.; Dobson, R.J. Discharge summary hospital course summarisation of in patient electronic health record text with clinical concept guided deep pre-trained transformer models. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 141, 104358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G. Generating Faithful and Complete Hospital-Course Summaries from the Electronic Health Record. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.