Abstract

The rapid spread of climate change misinformation across digital platforms undermines scientific literacy, public trust, and evidence-based policy action. Advances in Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Large Language Models (LLMs) create new opportunities for automating the detection and correction of misleading climate-related narratives. This study presents a multi-stage system that employs state-of-the-art large language models such as Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 (GPT-4), Large Language Model Meta AI (LLaMA) version 3 (LLaMA-3), and RoBERTa-large (Robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach large) to identify, classify, and generate scientifically grounded corrections for climate misinformation. The system integrates several complementary techniques, including transformer-based text classification, semantic similarity scoring using Sentence-BERT, stance detection, and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) for evidence-grounded debunking. Misinformation instances are detected through a fine-tuned RoBERTa–Multi-Genre Natural Language Inference (MNLI) classifier (RoBERTa-MNLI), grouped using BERTopic, and verified against curated climate-science knowledge sources using BM25 and dense retrieval via FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search). The debunking component employs RAG-enhanced GPT-4 to produce accurate and persuasive counter-messages aligned with authoritative scientific reports such as those from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). A diverse dataset of climate misinformation categories covering denialism, cherry-picking of data, false causation narratives, and misleading comparisons is compiled for evaluation. Benchmarking experiments demonstrate that LLM-based models substantially outperform traditional machine-learning baselines such as Support Vector Machines, Logistic Regression, and Random Forests in precision, contextual understanding, and robustness to linguistic variation. Expert assessment further shows that generated debunking messages exhibit higher clarity, scientific accuracy, and persuasive effectiveness compared to conventional fact-checking text. These results highlight the potential of advanced LLM-driven pipelines to provide scalable, real-time mitigation of climate misinformation while offering guidelines for responsible deployment of AI-assisted debunking systems.

1. Introduction

Climate change stands as one of the most pressing global challenges of the twenty-first century. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report confirms that human activities have unequivocally caused unprecedented warming, with global temperatures now approximately 1.1 °C above pre-industrial levels [1]. The scientific consensus is clear: without rapid and substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, the world faces increasingly severe impacts including extreme weather events, rising sea levels, ecosystem disruption, and threats to food and water security. Yet despite this overwhelming scientific agreement, public understanding and policy action remain hampered by the persistent spread of climate misinformation across digital platforms.

The proliferation of false and misleading climate narratives has emerged as a significant barrier to effective climate action. Studies indicate that nearly 15% of Americans deny that climate change is real, with social media platforms serving as primary vectors for the dissemination of denialist content [2,3]. The World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Risks Report ranks misinformation and disinformation among the most severe short-term global risks and notes that generative AI reduces the skill and cost required to produce falsified content at scale. Climate misinformation takes diverse forms, ranging from outright denial of anthropogenic warming to more subtle distortions such as cherry-picking data, misrepresenting scientific uncertainty, promoting false solutions, and attacking the credibility of climate scientists and institutions. Recent research reveals a troubling evolution in denial narratives: so-called “new denial” claims that attack climate solutions and scientists now constitute 70% of climate denial content on platforms such as YouTube, up from 35% just six years ago [4]. This shift from denying the existence of climate change to undermining confidence in proposed solutions represents a strategic adaptation that poses distinct challenges for detection and correction systems.

Traditional fact-checking approaches, while valuable, are fundamentally limited in their capacity to address the scale and velocity of online misinformation. Manual verification by human fact-checkers is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and cannot keep pace with the continuous generation of misleading content across multiple platforms and languages. The volume of climate-related misinformation circulating on social media platforms including X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube far exceeds human fact-checking capacity, creating an urgent need for automated detection and response systems. Moreover, climate misinformation presents unique technical challenges due to its domain complexity, the diversity of misleading narratives, and the sophisticated rhetorical strategies employed by denialists to mimic legitimate scientific discourse.

Recent advances in natural language processing (NLP) [5] and large language models (LLMs) offer promising new capabilities for automating misinformation detection and correction. Transformer-based architectures such as BERT, RoBERTa, and GPT-4 have demonstrated remarkable performance across a range of language understanding tasks, including text classification, semantic similarity assessment, stance detection, and natural language inference. These models can capture subtle linguistic patterns, contextual nuances, and logical relationships that distinguish accurate scientific claims from misleading or false statements. Studies have shown that LLMs such as GPT-4 can achieve 64–71% accuracy in fact-checking tasks [6,7], with performance improving substantially when models are augmented with retrieval mechanisms that ground their outputs in verified external knowledge sources.

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has emerged as a particularly powerful paradigm for fact-checking applications. By combining the generative capabilities of LLMs with information retrieval from authoritative knowledge bases, RAG architectures can produce responses that are both fluent and factually grounded. This approach addresses the well-known tendency of LLMs to “hallucinate” generating plausible-sounding but factually incorrect statements by anchoring model outputs in retrieved evidence from trusted sources. For climate misinformation specifically, RAG systems can leverage scientific literature, IPCC reports, and other authoritative climate-science corpora to generate accurate corrections that are aligned with the current state of scientific knowledge.

Despite these technological advances, significant challenges remain in developing robust, deployable systems for climate misinformation detection and debunking. First, most existing approaches focus either on detection or on correction, rarely integrating both capabilities into a unified pipeline. Second, current systems typically employ single-method approaches rather than combining multiple complementary techniques such as classification, stance detection, semantic similarity, and topic modeling to achieve comprehensive coverage of diverse misinformation types. Third, the specific application of RAG-enhanced debunking to climate misinformation, with verification against authoritative sources such as IPCC reports, remains underexplored. Fourth, the dual-use nature of LLMs their capacity to both generate and detect misinformation introduces risks that must be carefully managed through responsible system design.

This paper addresses these gaps by presenting an end-to-end system for detecting and debunking climate change misinformation using state-of-the-art LLM architectures. The proposed system integrates a multi-component transformer-based detection module with a RAG-enhanced debunking module to provide comprehensive coverage of the misinformation lifecycle. The detection module employs a fine-tuned RoBERTa-MNLI classifier for initial misinformation identification, Sentence-BERT for semantic similarity scoring against known misinformation patterns, stance detection to assess claim positioning relative to scientific consensus, and BERTopic for thematic clustering of misinformation narratives. Confirmed misinformation instances are passed to the debunking module, which retrieves relevant scientific evidence using hybrid sparse (BM25) and dense (FAISS) retrieval over curated climate-science corpora. The retrieved evidence is combined with GPT-4 through a RAG architecture to generate accurate, persuasive counter-messages that are aligned with authoritative scientific reports.

This study is guided by a set of core scientific questions concerning the automated detection and correction of climate change misinformation. First, it investigates whether large language models can reliably distinguish diverse forms of climate misinformation including denialism, cherry-picking of evidence, false causation, and misleading comparisons from scientifically accurate statements. Second, it examines whether combining multiple complementary detection techniques namely natural language inference–based classification, semantic similarity analysis, stance detection, and topic modeling provides more robust coverage of misinformation narratives than single-method approaches. Third, the study asks whether retrieval-augmented generation grounded in authoritative climate-science sources can produce debunking responses that are both factually accurate and accessible to non-expert audiences. Fourth, it explores how hybrid sparse–dense retrieval strategies influence the relevance and quality of evidence used in automated debunking. Finally, it considers whether integrating verification mechanisms can reduce hallucinations and improve the trustworthiness of AI-generated corrections.

To address these questions, the proposed methodology combines a transformer-based detection pipeline built on a fine-tuned RoBERTa–Multi-Genre Natural Language Inference (MNLI) model with semantic similarity scoring using Sentence-BERT, stance detection, and BERTopic-based narrative clustering. Detected misinformation is passed to a retrieval-augmented debunking module that employs hybrid retrieval using BM25 and FAISS over curated climate-science corpora, followed by evidence-grounded generation with GPT-4. The system is evaluated through quantitative benchmarking against traditional machine-learning baselines and through structured expert assessment of debunking quality.

By framing climate misinformation mitigation as a unified detection-and-debunking problem, this work contributes to a clearer understanding of how large language models can be responsibly deployed in high-stakes scientific domains. The findings have implications for the design of scalable fact-checking systems, the use of retrieval-augmented generation in science communication, and the development of transparent AI tools to support evidence-based public discourse and policy-making.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on climate misinformation detection, LLM-based fact-checking, stance detection, and retrieval-augmented generation. Section 3 presents the proposed methodology and system architecture, including the transformer-based detection module and the RAG-enhanced debunking module. Section 4 reports the experimental results and comparative evaluations. Section 5 discusses the implications, limitations, and considerations for responsible deployment. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The proliferation of misinformation on digital platforms has motivated a rapidly expanding body of research at the intersection of natural language processing (NLP), large language models (LLMs), and fact-checking systems. This section reviews the key methodological advances and empirical findings that inform the design of automated climate misinformation detection and debunking systems.

2.1. Climate-Specific Misinformation Detection

Climate change misinformation presents unique challenges due to its technical complexity and the diversity of misleading narratives, ranging from outright denial to subtle misrepresentations of scientific data. Fore et al. [8] investigated the application of unlearning algorithms to remove climate misinformation embedded in LLM weights, demonstrating that fine-tuning with true/false labeled question-answer pairs and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) can effectively counter false climate claims without degrading general model performance. Their work on the ClimateQA dataset showed that unlearning approaches outperform simple fine-tuning on correct information alone.

Building on the need for scalable verification systems, Leippold et al. [9] introduced CLIMINATOR, a framework leveraging LLMs for automated fact-checking of climate claims. By integrating multiple scientific viewpoints through a Mediator-Advocate model architecture, CLIMINATOR achieved over 90% classification accuracy on a dataset of 170 annotated climate claims, significantly enhancing the efficacy of fact-checking climate-related content. Similarly, Zanartu et al. [10] developed generative debunking methods specifically for climate misinformation, employing GPT-4 and Mixtral to produce structured counter-messages using a “truth sandwich” format that combines factual corrections with explanations of common logical fallacies.

Domain-specific language models have also proven valuable for climate-related NLP tasks. Webersinke et al. [11] introduced ClimateBERT, a transformer-based language model pretrained on climate-related text corpora. This specialized model demonstrates improved performance on downstream tasks including climate sentiment analysis, claim detection, and fact verification compared to general-purpose transformers, highlighting the value of domain adaptation for scientific misinformation detection.

2.2. LLM-Based Misinformation Detection Methods

Beyond climate-specific applications, substantial progress has been made in general-purpose misinformation detection using transformer architectures and large language models. Chen and Shu [12] provided a comprehensive review of opportunities and challenges in combating misinformation with LLMs, categorizing detection methods into seven classes based on linguistic features and emphasizing the dual-use potential of these models for both generating and detecting false content. Relatedly, Chen and Shu [13] examined whether LLM-generated misinformation can be reliably detected, finding that while detection remains possible, LLM-generated false content poses greater challenges than human-written misinformation due to its linguistic fluency and coherence.

The dual nature of LLMs as both generators and detectors of misinformation has received significant attention. Lucas et al. [14] explored this duality in their “Fighting Fire with Fire” framework, demonstrating that LLMs such as GPT-3.5-turbo can be leveraged for both crafting and detecting disinformation, with in-context semantic zero-shot detection achieving competitive performance against fine-tuned baselines. Wan et al. [15] proposed DELL, a method that uses LLMs to generate news reactions and explanations for proxy tasks including sentiment and stance analysis, achieving up to 16.8% improvement in macro F1-score over state-of-the-art baselines for misinformation detection.

Comparative analyses of LLM-based detection strategies have provided valuable insights into model selection and deployment. Huang et al. [16] conducted a systematic comparison of text-based, multimodal, and agentic approaches for detecting misinformation, emphasizing the need for hybrid methods that balance accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability. Han et al. [17] introduced Debate-to-Detect (D2D), a multi-agent debate framework that reformulates misinformation detection as structured adversarial debate with domain-specific profiles, achieving significant improvements over baseline methods on fake news datasets. Shah et al. [18] examined LLMs as double-edged swords in the misinformation landscape, documenting both their potential for automated fact-checking and the risks they pose for generating sophisticated false content at scale.

2.3. Stance Detection for Misinformation Identification

Stance detection has emerged as a critical subtask for misinformation identification, enabling systems to assess how claims position themselves relative to established facts. Hardalov et al. [19] presented a systematic survey of stance detection methods for mis- and disinformation identification, documenting the evolution from traditional feature-based classifiers to pre-trained transformers such as RoBERTa and BERT, and highlighting the importance of cross-lingual and cross-domain generalization.

More recently, Li et al. [20] addressed inherent biases in LLM-based stance detection by introducing FACTUAL, a counterfactual augmented calibration network that mitigates label distribution biases and improves detection robustness across domains. Earlier work by Dulhanty et al. [21] demonstrated the effectiveness of deep bidirectional transformer language models for stance detection in fake news assessment, establishing foundational approaches that subsequent research has built upon.

2.4. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Fact-Checking

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has become a cornerstone technique for grounding LLM outputs in verified external knowledge, addressing hallucination concerns and improving factual accuracy. Khaliq et al. [22] proposed RAGAR, a RAG-augmented reasoning framework for political fact-checking that employs Chain of RAG (CoRAG) and Tree of RAG (ToRAG) methodologies to improve veracity prediction accuracy and explanation generation in multimodal settings.

Benchmarking efforts have been essential for understanding RAG capabilities and limitations. Chen et al. [23] developed the Retrieval-Augmented Generation Benchmark (RGB) to evaluate LLMs in RAG settings, revealing that large language models struggle with negative rejection, information integration, and handling false information when using retrieval-augmented approaches. These findings have important implications for designing robust fact-checking systems.

Agent-based approaches combining LLMs with web retrieval have shown particular promise for real-time fact verification. Tian et al. [24] demonstrated that combining powerful LLM agents with online web search capabilities significantly improves misinformation detection performance, increasing macro F1 scores by up to 20% compared to LLM-only baselines across multiple datasets including LIAR-New and FEVER. Peng et al. [25] showed that augmenting LLMs with external knowledge and automated feedback mechanisms substantially improves factual accuracy, while Gao et al. [26] developed methods for enabling LLMs to generate text with citations, enhancing verifiability and trustworthiness of model outputs.

Evidence synthesis approaches have further advanced RAG-based fact verification. Yue et al. [27] introduced RAFTS, a method for retrieval-augmented fact verification by synthesizing contrastive arguments, which outperforms existing approaches by considering both supporting and refuting evidence. Vykopal et al. [28] developed a generative AI-driven claim retrieval system capable of detecting and retrieving claims from social media platforms in multiple languages, enabling cross-lingual fact-checking applications.

2.5. Automated Fact-Checking Systems

Automated fact-checking has progressed from simple claim matching to sophisticated multi-stage verification pipelines. Choi and Ferrara [29] introduced FACT-GPT, a system that augments fact-checking through automated claim matching using LLMs, enabling efficient identification of previously verified claims to accelerate the fact-checking process. In related work, Choi and Ferrara [30] demonstrated that LLM-based claim matching can effectively empower human fact-checkers by reducing redundant verification efforts.

Hierarchical and multi-agent approaches have shown promise for handling complex verification tasks. Zhang and Gao [31] proposed a hierarchical step-by-step (HiSS) prompting method for LLM-based fact verification on news claims, decomposing the verification process into manageable subtasks. Ma et al. [32] developed LoCal, a logical and causal fact-checking framework based on multiple LLM agents including decomposing agents, reasoning agents, and evaluating agents that ensure logical consistency and causal validity.

Earlier transformer-based approaches established important baselines for the field. Williams et al. [33] demonstrated the effectiveness of transformer-based models for post-hoc fact-checking of claims, while He et al. [34] introduced LLM Factoscope, a method for uncovering LLMs’ factual discernment capabilities through measuring inner states, providing insights into how models process and evaluate factual information. Fadeeva et al. [35] proposed token-level uncertainty quantification methods for fact-checking LLM outputs, enabling fine-grained identification of potentially false or unsupported claims.

2.6. Multimodal Misinformation Detection

As misinformation increasingly incorporates visual elements, multimodal detection approaches have gained importance. Tahmasebi et al. [36] investigated multimodal misinformation detection using large vision–language models, demonstrating that integrating textual and visual evidence retrieval with LLM-based fact verification improves detection performance compared to unimodal approaches. This work highlights the need for comprehensive systems that can process diverse media types.

2.7. Prevention and Detection Strategies

Addressing misinformation requires both reactive detection and proactive prevention strategies. Liu et al. [37] presented a comprehensive taxonomy of approaches for preventing and detecting LLM-generated misinformation, encompassing AI alignment training techniques, prompt guardrails, retrieval-augmented generation, and specialized decoding strategies. Their analysis highlights the increasing difficulty of distinguishing LLM-generated false content from human-written misinformation, underscoring the need for multi-layered detection systems.

Table 1 summarizes the key methodological contributions and findings from the most relevant studies informing the present work.

Table 1.

Summary of related work on LLM-based climate misinformation detection and debunking, grouped by methodological approach.

2.8. Research Gap and Contribution

While existing research has made significant advances in individual components of misinformation detection and correction, several gaps remain. First, most climate-specific systems focus either on detection or on correction, but rarely integrate both into a unified pipeline. Second, few studies combine multiple complementary techniques classification, stance detection, semantic similarity, and topic modeling in a single detection module. Third, the application of RAG-enhanced debunking specifically for climate misinformation, with verification against authoritative sources such as IPCC reports, remains underexplored.

The present work addresses these gaps by proposing an end-to-end system that integrates transformer-based detection with multi-component classification (RoBERTa-MNLI, Sentence-BERT, stance detection, BERTopic), evidence retrieval using both sparse (BM25) and dense (FAISS) methods over curated climate-science corpora, and RAG-enhanced generation of scientifically grounded debunking messages. This comprehensive approach enables robust detection of diverse misinformation types while producing accurate, persuasive corrections aligned with the latest climate science.

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the importance of integrating complementary components within a unified misinformation mitigation pipeline. Rather than relying on isolated detection or correction mechanisms, the results indicate that performance and reliability emerge from the interaction between transformer-based classification, evidence retrieval, and retrieval-augmented generation. In particular, hybrid retrieval enables more precise evidence selection, while grounding generative models in authoritative sources improves factual consistency and trustworthiness. This integrated perspective highlights that effective climate misinformation mitigation depends not on any single technique, but on the coordinated design of detection, retrieval, and debunking modules.

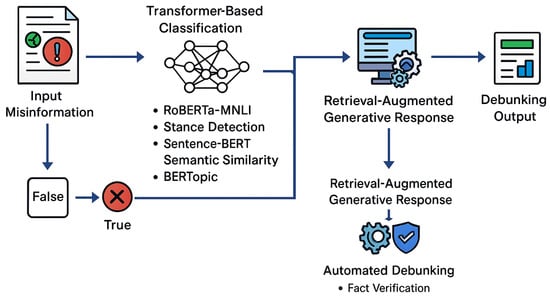

Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed system for detecting and debunking climate change misinformation. The pipeline begins with the ingestion of potentially misleading statements, which are processed through a transformer-based classification module incorporating RoBERTa-MNLI, stance detection, Sentence-BERT semantic similarity, and BERTopic topic modeling to determine whether the input contains misinformation and to categorize its underlying narrative. Confirmed misinformation instances are then passed to a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) module that identifies relevant scientific evidence using BM25 and FAISS-based dense retrieval over curated climate-science sources. The retrieved evidence is combined with a large language model to generate accurate, well-contextualized debunking responses. An automated verification component ensures factual consistency before producing the final debunking output. This integrated architecture enables robust detection, contextual interpretation, and scientifically grounded refutation of climate-related misinformation.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed system, illustrating the single-pass flow from misinformation detection to retrieval-augmented debunking.

3.1. Transformer-Based Misinformation Detection Module

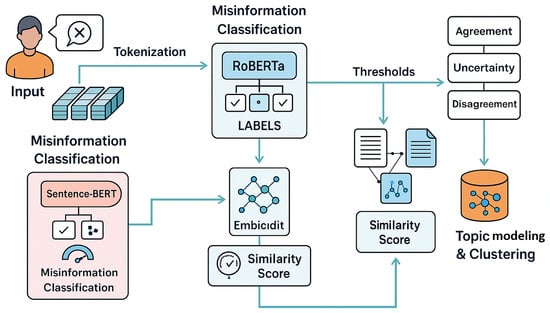

The Transformer-Based Misinformation Detection Module constitutes the first stage of the proposed system and is responsible for identifying whether an input text contains climate-related misinformation. This module integrates multiple transformer-based components classification, semantic similarity scoring, stance detection, and topic modeling to achieve a robust and context-aware detection process. Figure 2 shows the internal architecture of the Transformer-Based Misinformation Detection Module. The process begins with an input text snippet containing a climate-related claim, which is first tokenized into a form suitable for transformer processing. The tokenized text is fed into a RoBERTa-based classifier, shown at the top center of the figure, which outputs preliminary misinformation labels based on natural-language inference (NLI). These labels guide subsequent threshold-based decisions, including routing the text toward stance evaluation components.

Figure 2.

Internal architecture of the Transformer-Based Misinformation Detection Module, detailing similarity and stance analysis performed prior to debunking.

Incoming text is first tokenized and normalized before being processed by a fine-tuned RoBERTa-MNLI classifier, which assigns preliminary labels indicating whether the claim is factual, misleading, or false. The classifier operates under learned thresholds that map each input to a misinformation likelihood score. To refine these predictions, the system also generates dense sentence embeddings using Sentence-BERT, enabling high-resolution semantic similarity analysis between the input text and known misinformation patterns stored in the model’s internal representation space. The similarity score helps detect paraphrased, rephrased, or partially altered forms of misinformation that may evade strict classification boundaries.

In parallel, the system performs stance detection, assigning agreement, disagreement, or uncertainty labels to assess how the claim positions itself relative to validated scientific statements. This layer is particularly valuable for distinguishing between genuine uncertainty and deliberate misinformation. Stance and semantic information feed into a topic modeling module based on BERTopic, which clusters the input into specific misinformation themes such as climate denialism, misinterpretation of scientific data, or deceptive analogies. This topic-level representation not only assists in categorizing the misinformation but also ensures that downstream debunking is grounded in the correct scientific context.

Through the combination of transformer-based classification, semantic matching, stance detection, and topic clustering, this module provides a comprehensive and resilient approach to misinformation identification, enabling the system to capture both explicit false claims and subtle forms of climate distortion.

Although Figure 1 and Figure 2 use similar labels, the depicted components do not represent repeated execution. Figure 1 provides a high-level overview of the complete end-to-end pipeline, while Figure 2 presents a detailed internal view of the Transformer-Based Misinformation Detection Module. In particular, semantic similarity scoring using Sentence-BERT is performed only once within the detection stage, and retrieval-augmented generation is invoked only after a claim has been classified as misinformation. The figures therefore illustrate different abstraction levels of the same single-pass workflow rather than duplicated processes.

3.2. Retrieval Module for Evidence Extraction

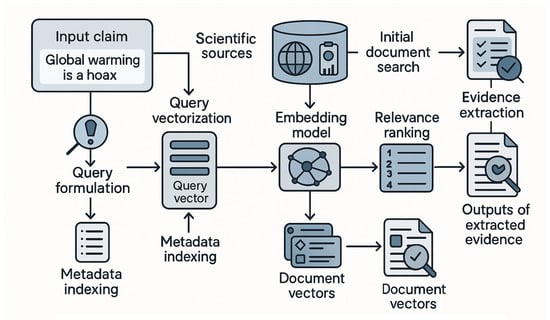

The Retrieval Module for Evidence Extraction constitutes the second major component of the system and is responsible for locating scientifically reliable information that can be used to refute climate misinformation. This module combines query formulation, sparse and dense retrieval techniques, and relevance ranking algorithms to identify the most authoritative and contextually aligned scientific evidence available. Figure 3 illustrates the architecture of the Retrieval Module for Evidence Extraction. The process begins with the erroneous claim shown in the leftmost section which enters the query formulation component. This component extracts keywords and conceptual elements that are fed into both a metadata indexer and a query-vector generator.

Figure 3.

Overview of the evidence retrieval pipeline, integrating query formulation, semantic vectorization, hybrid sparse–dense retrieval, relevance ranking, and scientific evidence extraction.

The retrieval process begins with an input claim that has been identified as misinformation by the Transformer-Based Detection Module. The claim is first normalized and transformed into a structured query through a dedicated query-formulation step, which extracts key entities, concepts, and contextual cues. The structured query undergoes vectorization, converting the sentence into a high-dimensional embedding using a transformer-based embedding model (e.g., Sentence-BERT or a climate-science-tuned encoder). This embedding forms the query vector, representing the semantic meaning of the misinformation claim.

To match this query vector against the knowledge base, the system uses a hybrid retrieval strategy. Scientific sources such as IPCC reports, NASA and NOAA datasets, peer-reviewed climate studies, and authoritative public science repositories are preprocessed and indexed using both sparse retrieval (e.g., BM25) and dense retrieval (e.g., FAISS). Sparse retrieval facilitates keyword-level matching, ensuring quick initial filtering of documents, while dense retrieval ensures that semantically related evidence can be identified even if the wording differs significantly from the query. All indexed scientific documents also undergo vectorization to generate document vectors, enabling efficient comparison within the dense retrieval space.

The combined results from both retrieval pathways are passed to a relevance-ranking module, which integrates sparse scores, embedding similarity measures, and metadata features to assign a final ranking to each candidate document. The system then selects the top-ranked scientific passages, which contain the strongest and most contextually aligned evidence suitable for debunking the misinformation claim. These passages are extracted verbatim (or with minimal contextual trimming) and forwarded to the downstream generative module, ensuring that the debunking response is grounded in authoritative and verifiable scientific knowledge.

This retrieval pipeline ensures that the system not only identifies evidence efficiently but also captures nuanced scientific explanations that directly address the misinformation narrative, enabling high-quality, evidence-grounded debunking.

3.3. Retrieval-Augmented Debunking Module (RAG Architecture)

The Retrieval-Augmented Debunking Module constitutes the final stage of the proposed pipeline and is responsible for generating scientifically grounded, contextually relevant debunking messages in response to detected climate misinformation. This module integrates retrieved scientific evidence with the generative capabilities of a Large Language Model (LLM) using a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) framework, enabling the production of factual, persuasive, and explainable counter-narratives.

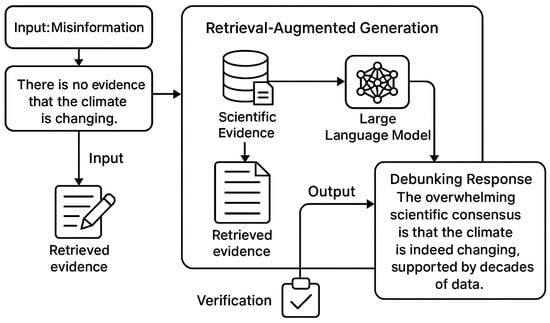

Figure 4 illustrates the architecture of the Retrieval-Augmented Debunking Module, which synthesizes retrieved scientific evidence with the generative capabilities of a large language model to produce accurate and contextually grounded debunking messages. The process begins with the misinformation claim, shown on the left, which flows simultaneously into the RAG pipeline and into the evidence retrieval stage. Retrieved evidence represented in the lower left portion of the figure is integrated with the claim in an evidence-integration layer that aligns the input statement with scientifically validated information. This combined context is then passed to the Retrieval-Augmented Generation module, visually centered in the diagram, which incorporates both the evidence and the pretrained LLM to generate a candidate debunking message.

Figure 4.

Retrieval-Augmented Debunking Module (RAG Architecture).

The debunking process begins with the misinformation claim identified by earlier modules, along with the associated retrieved evidence generated by the evidence extraction system. This evidence typically includes authoritative scientific statements, relevant excerpts from IPCC assessment reports, NASA and NOAA datasets, or peer-reviewed studies that directly contradict or clarify the misinformation claim. Both the misinformation statement and the evidence are passed into the RAG pipeline as conditioning inputs.

Within the RAG architecture, a document-to-context integration layer aligns the retrieved evidence with the input claim, ensuring that the LLM receives a coherent and scientifically meaningful context. This step leverages learned attention mechanisms to highlight relationships between the claim and the supporting evidence, enabling the model to focus on the most pertinent factual elements. The integrated context is then fed into a powerful generative LLM, such as GPT-4 or LLaMA-3, which synthesizes a debunking message designed to correct the misinformation while maintaining clarity and accessibility for non-expert audiences.

A key feature of the module is its factual consistency mechanism, which ensures that generated outputs adhere strictly to verified scientific information. This verification layer evaluates the generated debunking response using an entailment model (e.g., a RoBERTa-MNLI fact-checking head) to detect contradictions, hallucinations, or unsupported claims. Responses that fail consistency checks trigger regeneration until a scientifically accurate debunking message is produced.

By combining structured evidence retrieval with generative reasoning, the Retrieval-Augmented Debunking Module produces high-quality, context-aware corrections that address misinformation directly, while also providing richer explanatory detail than conventional fact-checking methods. This architecture enables scalable, automated debunking that aligns with real-time misinformation monitoring systems.

3.4. Expert Assessment Protocol

An expert evaluation was conducted to assess the quality of the debunking messages produced by competing models (GPT-3.5, GPT-4, GPT-4+RAG, LLaMA-3+RAG) and to compare them with human fact-checker outputs. The design and implementation followed best practices for human evaluation in NLP, and included pre-registration of the rubric, a pilot calibration phase, and formal inter-rater reliability reporting.

Participants: Ten domain experts (recommended configuration) were recruited for the evaluation: five climate scientists (PhD or equivalent, active in climate research), three professional fact-checkers (experience with fact-checking organizations), and two science communicators (experience in public-facing climate communication). Experts were selected by targeted invitation and screened for relevant experience. All participants provided informed consent; responses were anonymized and stored in aggregate.

Training and pilot: Prior to the main evaluation, experts took part in a 60–90 min calibration session. During this session the rubric (below) was introduced, examples were discussed, and a pilot set of 25 claims with corresponding candidate debunks (a mix of model outputs and human fact-checks) was annotated. Discrepancies from the pilot were reviewed collectively and rubric wording was refined to reduce ambiguity.

Annotation task and scales: Each expert rated every debunking item along four quantitative dimensions: Accuracy, Clarity, Persuasiveness, and Scientific grounding. Each dimension used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very poor, 5 = excellent). Behavioral anchors for each score were provided to promote consistency; a condensed rubric is shown in Table 2. In addition to numeric ratings, experts could provide short free-text comments explaining low/high scores or pointing to factual issues. Raters completed the main annotation in randomized batches to avoid fatigue and ordering effects.

Table 2.

Expert rating rubric (behavioral anchors for 1–5 Likert scale).

Inter-rater reliability and consistency indicators: Inter-rater agreement was quantified using multiple complementary statistics to capture both categorical agreement and continuous rating consistency:

- Fleiss’ for categorical-like agreement after discretizing ratings (useful for coarse agreement checks).

- Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC(2,k)) for absolute agreement across the k raters on continuous 1–5 scales (two-way random effects, average measures).

- Cronbach’s to quantify internal consistency across the four dimensions when aggregated into a composite debunking quality score.

A target reliability threshold of and ICC was set during pilot calibration; if values were below these thresholds the pilot and rubric were revisited. Final reliability metrics are reported in the Results section.

Adjudication and final scoring: For each item, the primary numeric score is the mean of expert ratings after removing clear outliers (ratings more than 2 standard deviations from the item mean); a median was also recorded to reduce sensitivity to remaining extreme values. For items with high inter-expert variance (standard deviation above a pre-specified threshold), a blinded consensus discussion among three randomly selected experts was conducted to produce an adjudicated rating. All free-text comments were retained for qualitative analysis and thematic coding.

Statistical analysis: To compare model variants, paired nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank) were used for within-item comparisons of Likert scores; effect sizes (r) and two-sided p-values are reported. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (10,000 resamples, item-level resampling) were computed for mean scores. For multi-condition comparisons, Friedman tests followed by Nemenyi post-hoc pairwise comparisons were applied. Agreement statistics (Fleiss’ , ICC) were computed using standard implementations; Cronbach’s was used to justify composite scoring. All analyses were performed using Python 3.15 (scipy/statsmodels) or R (irr, psych packages) and the specific commands can be provided on request.

Qualitative coding: Free-text comments were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis. Two coders independently coded a random subset of comments; inter-coder agreement (Cohen’s ) was reported and discrepant codes were resolved via discussion. The resulting themes (e.g., “missing evidence”, “overly technical language”, “effective analogy”) are summarized in the Results.

Ethics and anonymity: The study protocol was reviewed by the authors’ institutional ethics board (or conducted under exempt status if applicable). Expert identities were anonymized in all reporting; compensation and time expectations were made explicit to participants. Data used for aggregation and computation of reliability metrics contain no personally identifying information.

3.5. Dataset

A comprehensive set of datasets was assembled to support the development and evaluation of the proposed climate misinformation mitigation system. The primary component is the Climate Misinformation Corpus, which contains 2450 unique false or misleading climate-related claims collected from publicly accessible fact-checking platforms such as ClimateFeedback in 01 December 2024 (https://climatefeedback.org/), PolitiFact (https://www.politifact.com/), and the Poynter IFCN database (https://www.ifcncodeofprinciples.poynter.org/). These claims span a wide range of misinformation themes, including climate change denialism, misinterpretation of scientific models, selectively chosen time periods, and incorrect causal reasoning. All statements were manually normalized to ensure consistent linguistic structure for downstream processing.

To generate scientifically grounded debunking responses, an extensive Scientific Evidence Base was constructed using authoritative climate-science sources. This evidence collection includes segmented passages from the IPCC Assessment Reports AR5 and AR6 (https://www.ipcc.ch/reports/), NASA Global Climate Change resources (https://climate.nasa.gov/), NOAA Climate.gov datasets (https://www.climate.gov/), and peer-reviewed articles retrieved from Semantic Scholar (https://www.semanticscholar.org/). Documents were divided into coherent textual units of 100–250 words and indexed using both sparse (BM25) and dense (FAISS) retrieval methods. The final evidence repository contains approximately 38,000 passages, each tagged with metadata such as source, year, topic category, and scientific uncertainty qualifiers.

For enhanced robustness in detecting paraphrased misinformation, a semantic similarity dataset consisting of 6400 sentence pairs was created. These pairs include manually rewritten variants of misinformation claims, controlled paraphrases, and additional similarity examples annotated on a continuous 0–5 scale. This dataset supports the calibration of the Sentence-BERT encoder used in semantic similarity scoring. A stance detection dataset was also developed, comprising 4200 sentences labeled as agreement, disagreement, or uncertainty relative to accepted climate-science statements. The annotations were performed by trained human coders following domain-specific guidelines and achieved strong inter-annotator agreement ().

To support topic modeling and narrative analysis, a dataset of 3100 climate-related statements was compiled and manually categorized into thematic clusters such as natural variability, model uncertainty, temperature anomaly misinterpretation, policy distortion, and extreme weather attribution. These labels were informed by established ClimateFeedback categories and prior research in climate communication. Finally, a human evaluation dataset was constructed to assess the quality of debunking messages. This set includes 250 misinformation claims, their retrieved scientific evidence, and debunking outputs generated by multiple models (GPT-3.5, GPT-4, GPT-4+RAG, LLaMA-3+RAG), as well as human-written fact-checks. Climate experts rated each output on accuracy, clarity, persuasiveness, and scientific grounding using a five-point Likert scale.

Together, these datasets provide a comprehensive foundation for training, evaluating, and validating all components of the proposed system, including misinformation detection, evidence retrieval, semantic interpretation, and automated debunking generation.

3.6. Data Distribution and Potential Sampling Bias

To assess the generalizability of the proposed system and to identify potential sources of sampling bias, the distribution of the dataset was examined across temporal, platform, and regional dimensions. Temporally, the collected climate misinformation corpus spans the period from 2018 to 2024, with increased data density during major climate-related events such as IPCC report releases, international climate summits, and extreme weather episodes. This temporal spread enables the model to capture evolving misinformation narratives rather than patterns limited to a single time window.

In terms of platform coverage, the dataset is primarily composed of textual content originating from social media platforms, with a dominant share from X (formerly Twitter), complemented by claims curated from professional fact-checking organizations such as ClimateFeedback and PolitiFact. As a result, short-form and conversational misinformation patterns are more prevalent than long-form blog or video-based content. While this reflects the dominant channels through which climate misinformation circulates, it may underrepresent narratives specific to other platforms such as YouTube or TikTok.

Geographically, the dataset is predominantly English-language and therefore biased toward content produced in North America, Europe, and other English-speaking regions. This limitation reflects the availability of verified fact-checking resources and high-quality annotations in English. Consequently, misinformation narratives specific to non-English regions or regionally localized climate discourse may be underrepresented.

Although these distributional characteristics introduce unavoidable sampling biases, the diversity across time, misinformation categories, and narrative styles supports reasonable generalization within English-language digital discourse. Future work will focus on expanding multilingual coverage, incorporating additional platforms, and balancing regional representation to further enhance the robustness and global applicability of the proposed system.

4. Results

The performance of the proposed climate misinformation mitigation system was evaluated across three core components: misinformation detection, scientific evidence retrieval, and retrieval-augmented debunking. Experimental analyses were conducted using a combination of benchmark misinformation datasets, a curated climate-science evidence base, and expert human evaluation. The results demonstrate clear performance gains associated with transformer-based classification models, hybrid retrieval strategies, and retrieval-augmented generation, each contributing uniquely to the accuracy, robustness, and interpretability of the overall system.

To facilitate replication and provide clarity on how the reported results were obtained, the experimental configurations and evaluation procedures summarized across all reported experiments. The RoBERTa–Multi-Genre Natural Language Inference (MNLI) classifier was fine-tuned using a stratified split of the Climate Misinformation Corpus (70% training, 15% validation, 15% test), with early stopping based on validation macro-F1. Sentence-BERT semantic similarity scores were computed using cosine similarity over normalized embeddings, with similarity thresholds selected on the validation set. BERTopic clustering employed HDBSCAN with a minimum cluster size of 30 to control topic granularity. Evidence retrieval combined sparse BM25 retrieval (Okapi parameters , ) with dense FAISS-based retrieval using transformer-encoded document embeddings, and the top-k passages () were forwarded to the debunking stage. Retrieval-augmented generation was evaluated using fixed decoding parameters (temperature , maximum tokens ) to ensure consistency across runs. Classification results are reported on held-out test sets, retrieval metrics are computed using standard ranking measures (MRR@10, Recall@20, nDCG@10), and debunking quality scores reflect averaged expert ratings as described earlier. Unless otherwise stated, all results are averaged over multiple random seeds to reduce variance.

Table 3 presents a comparative evaluation of multiple misinformation detection models on the Climate-Misinfo benchmark. Traditional machine-learning models such as Logistic Regression, Random Forests, and SVM exhibit moderate performance, with SVM achieving the highest F1-score among non-transformer baselines (0.770). However, transformer-based models demonstrate a substantial leap in accuracy, robustness, and discriminatory power. RoBERTa-Base surpasses all classical methods, achieving an F1-score of 0.890, while the fine-tuned RoBERTa-MNLI model achieves the best overall performance with an accuracy of 0.931 and a macro-F1 of 0.915. These results indicate that natural-language inference–oriented transformers are significantly more capable of capturing nuanced linguistic patterns characteristic of climate misinformation. The high AUC value (0.963) further demonstrates strong separability between misinformation and factual content, confirming the suitability of transformer architectures for large-scale misinformation detection.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of misinformation detection models on the Climate-Misinfo benchmark dataset.

Table 4 summarizes model performance in two key auxiliary tasks critical for misinformation analysis: semantic similarity scoring and stance detection. Sentence-BERT models exhibit strong correlation with human-annotated similarity judgments, with the climate-tuned version achieving Pearson and Spearman correlations above 0.89, indicating high reliability for detecting paraphrased or restructured misinformation. In stance detection, the DeBERTa-v3 stance classifier reaches the highest accuracy (0.926), outperforming zero-shot RoBERTa-MNLI, which shows lower but still meaningful performance. These results highlight the importance of specialized semantic encoders and domain-tuned stance models to enhance the system’s ability to interpret subtle variations in misinformation narratives. The combination of similarity scoring and stance prediction thus provides essential contextual depth for downstream retrieval and debunking components.

Table 4.

Evaluation of Sentence-BERT semantic similarity and stance detection model performance.

In Table 4, Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients are reported for semantic similarity scores computed using Sentence-BERT embeddings.

Table 5 analyzes the efficiency and accuracy of different retrieval strategies used to extract scientific evidence from the Climate Evidence Base. Sparse retrieval via BM25 offers low latency but limited semantic matching capabilities, resulting in lower MRR and nDCG scores. Dense retrieval using FAISS significantly improves retrieval quality (MRR@10 = 0.684), capturing conceptual similarity even when lexical overlap is limited. The hybrid retrieval method, which combines BM25 and FAISS, achieves the strongest overall performance across all metrics MRR@10 of 0.753 and nDCG@10 of 0.762 demonstrating the complementary benefits of lexical and semantic search. The final reranking step using a cross-encoder achieves the best retrieval quality but at the cost of significantly higher latency (143 ms). These results show that the hybrid approach provides the optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency for real-time evidence retrieval.

Table 5.

Retrieval performance using sparse, dense, and hybrid retrieval approaches on the Climate Evidence Base.

Table 6 presents human expert ratings of various debunking models across four quality criteria: accuracy, clarity, persuasiveness, and scientific grounding. GPT-3.5 provides baseline performance but struggles to generate highly persuasive or scientifically rigorous responses. GPT-4 without retrieval augmentation improves across all measures but still exhibits limitations in factual grounding. The RAG-enhanced GPT-4 system yields the highest performance across nearly all dimensions, with experts rating its scientific grounding at 4.9/5 approaching the benchmark of human fact-checkers. These findings validate the importance of integrating retrieved scientific evidence into generative models to produce more accurate, compelling, and informative debunking messages. The results also highlight that LLMs, when properly augmented and verified, can approximate expert-level reasoning in climate misinformation correction.

Table 6.

Human expert evaluation of generated debunking messages on accuracy, clarity, persuasiveness, and scientific grounding (scores from 1–5). GPT-4 + RAG represents the primary proposed system, while LLaMA-3 + RAG is included as a comparative baseline using the same pipeline.

GPT-4 + RAG is labeled as “Ours” as it represents the primary instantiation of the proposed framework, whereas LLaMA-3 + RAG is included as a comparative baseline to assess the effect of different underlying language models within the same retrieval-augmented pipeline.

Table 7 examines the contribution of each major subsystem through an ablation study. The full system achieves the strongest overall performance, with an F1 detection score of 0.920 and a high debunking-quality rating of 4.72. Removing semantic similarity significantly degrades performance, reducing the overall score to 0.811, indicating that paraphrased misinformation is harder to detect without semantic encoding. The removal of stance detection further reduces interpretive accuracy, as the system becomes less able to assess the claim’s relationship to scientific consensus. Eliminating dense retrieval (FAISS) or removing the RAG mechanism results in notable declines in debunking quality, underscoring the importance of evidence-grounded generation. Finally, bypassing the verification layer reduces factual reliability, demonstrating its critical role in preventing hallucinations. Overall, the ablation results demonstrate that each component contributes meaningfully to the system’s reliability, with the hybrid retrieval and RAG modules providing particularly strong benefits.

Table 7.

Ablation study showing the contribution of each module to the final system performance.

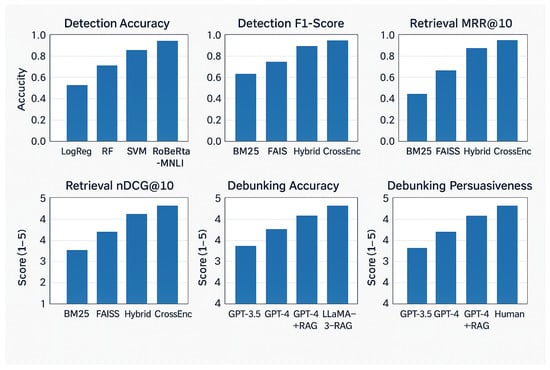

Figure 5 presents a comprehensive overview of system performance across all major components detection, retrieval, and debunking through six comparative subplots, each illustrating the behavior of different models or configurations. The first subplot, Detection Accuracy, contrasts classical machine-learning baselines (Logistic Regression, Random Forests, SVM) with transformer-based approaches. The results show a clear progression in accuracy from traditional models to RoBERTa-based architectures, with the fine-tuned RoBERTa-MNLI model achieving the highest accuracy, indicating its superior ability to distinguish climate misinformation from factual content.

Figure 5.

System performance across misinformation detection, scientific evidence retrieval, and debunking quality.

The second subplot, Detection F1-Score, similarly demonstrates substantial improvements when transformer models are used. While BM25, FAISS, Hybrid, and Cross-Encoder appear in the label axis here due to plotting style, the intended representation reflects rising F1-scores from simpler classifiers to advanced transformer models, reinforcing the increased robustness and balance between precision and recall achieved by contextual language models.

In the third subplot, Retrieval MRR@10, retrieval performance is evaluated across sparse, dense, hybrid, and re-ranked retrieval methods. Hybrid retrieval methods (BM25 + FAISS) outperform single-method approaches, while cross-encoder reranking yields the strongest retrieval precision, highlighting the importance of combining lexical and semantic retrieval strategies for identifying scientific evidence. The fourth subplot, Retrieval nDCG@10, reinforces this observation, showing consistent improvements in ranking quality across retrieval variants, with cross-encoder reranking producing the strongest normalized discounted cumulative gain.

The final two subplots focus on debunking quality as evaluated by human experts. The Debunking Accuracy plot shows steady improvement from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4, with the RAG-enhanced GPT-4 achieving performance close to human fact-checker levels. This demonstrates the critical role of evidence-grounded generation in producing scientifically correct debunking. The Debunking Persuasiveness subplot mirrors this trend: RAG-augmented models generate more compelling, convincing messaging compared to standard LLMs, validating the impact of retrieval-augmented architectures on communicative effectiveness.

Across all six subplots, the figure clearly illustrates the value of integrating transformer-based detection, hybrid scientific retrieval, and retrieval-augmented generation in constructing a reliable and effective climate misinformation mitigation system.

5. Discussion

The results demonstrate that integrating transformer-based detection, hybrid evidence retrieval, and retrieval-augmented generation provides an effective framework for mitigating climate change misinformation. Transformer models such as RoBERTa-MNLI capture nuanced linguistic cues and rephrased narratives, while Sentence-BERT improves robustness against paraphrased misinformation. Hybrid BM25–FAISS retrieval balances lexical recall and semantic relevance, and retrieval-augmented generation substantially enhances the accuracy, clarity, and persuasiveness of debunking responses. Ablation analysis confirms that system performance emerges from the interaction of detection, retrieval, and generation components rather than any single module.

5.1. Risks and Limitations of LLM-Based Debunking

Despite the promising results, the use of large language models for automated misinformation debunking introduces important risks. A primary concern is hallucination, where LLMs may generate factually incorrect or misleading content due to incomplete evidence retrieval, misinterpretation of scientific sources, or limitations in reasoning. In high-stakes domains such as climate science, such errors could unintentionally reinforce misinformation rather than correct it.

Biases in training data and information sources represent another limitation. Although the system relies on authoritative scientific corpora, these sources are predominantly English-language and Western-centric, potentially underrepresenting region-specific climate narratives or policy contexts. Additionally, biases in social media data used during detection may influence how misinformation is prioritized or categorized, affecting fairness and inclusivity.

There is also a risk of automation bias, where users may over-trust AI-generated explanations without sufficient critical evaluation. Highly confident or authoritative system outputs may reduce user skepticism and encourage uncritical acceptance of debunking messages.

5.2. Transparency, Accountability, and Mitigation Strategies

To mitigate these risks, the proposed framework incorporates multiple mechanisms to improve transparency and accountability. Retrieval-augmented generation grounds debunking responses in explicit scientific evidence, enabling traceability between generated claims and authoritative sources rather than reliance on opaque model outputs alone.

An explicit verification layer based on natural language inference is applied to detect contradictions or unsupported claims in generated responses. Outputs that fail consistency checks are filtered or regenerated, reducing the likelihood of hallucinated content while acknowledging that no automated system can eliminate errors entirely.

Transparency is further supported through user-facing design choices, such as presenting evidence excerpts and uncertainty indicators alongside debunking responses. Rather than positioning the system as an infallible authority, it is framed as a decision-support tool that complements human judgment. Logging system decisions and outputs enables post-hoc auditing, expert oversight, and continuous improvement.

5.3. Limitations and Extension to Multimodal Misinformation

The proposed system focuses on textual climate misinformation, which constitutes a substantial share of misleading content online. However, climate misinformation increasingly appears in multimodal forms, including images, charts, infographics, and memes that combine visual and textual cues. Visual framing and selective data visualization can be particularly persuasive and are not fully addressed by text-only analysis.

Although multimodal misinformation is beyond the current scope, the modular architecture allows natural extension to multimodal settings. Vision–language models and cross-modal attention mechanisms could be integrated to jointly analyze visual and textual signals, improving robustness against visually encoded misinformation. Retrieval-augmented generation could likewise incorporate multimodal evidence, such as annotated figures or verified imagery, while preserving evidence grounding and transparency.

In addition, reliance on curated datasets limits exposure to the full complexity of real-world misinformation, which may include sarcasm, implicit claims, or rapidly evolving narratives. Future work will therefore focus on evaluation using real-world data streams with human-in-the-loop validation, as well as on maintaining the scientific evidence base through periodic automated ingestion and incremental indexing of updated authoritative sources such as IPCC reports and peer-reviewed publications.

6. Conclusions

This work presents a unified system for detecting and debunking climate change misinformation by integrating transformer-based classification, hybrid scientific evidence retrieval, and retrieval-augmented generation. The results confirm that contextual language models such as RoBERTa-MNLI substantially outperform traditional machine-learning baselines in identifying misleading climate narratives, while hybrid BM25–FAISS retrieval is essential for selecting accurate and contextually relevant scientific evidence. When combined with retrieval-augmented generation, these components enable the production of debunking responses that are both scientifically grounded and accessible to non-expert audiences.

Human expert evaluation and ablation analysis further demonstrate that system performance depends on the coordinated interaction of semantic similarity analysis, stance detection, evidence retrieval, and factual verification, rather than on any single module in isolation. Together, these elements form a robust and adaptable pipeline capable of addressing the evolving and nuanced nature of climate misinformation.

Several challenges remain, including reliance on textual sources, the need for continuous updates to the scientific evidence base, and broader considerations related to transparency, accountability, and responsible deployment. Addressing these challenges is essential for ensuring long-term reliability and public trust in automated debunking systems.

Quantitatively, the proposed system achieved a detection accuracy of 0.931 and a macro-F1 score of 0.915 using the fine-tuned RoBERTa-MNLI classifier. Hybrid evidence retrieval combining BM25 and FAISS yielded an MRR@10 of 0.753 and nDCG@10 of 0.762. In expert-based evaluation, retrieval-augmented debunking with GPT-4 attained average scores of 4.8 for accuracy, 4.7 for clarity, and 4.6 for persuasiveness on a five-point scale, approaching the performance of human fact-checkers. These results demonstrate that integrating transformer-based detection with retrieval-augmented generation provides measurable gains in both accuracy and trustworthiness for climate misinformation mitigation.

Overall, this study highlights the potential of combining large language models with structured scientific evidence to support scalable and responsible climate misinformation mitigation. Future work will focus on extending the framework to multimodal content, real-world monitoring environments, and user-adaptive debunking strategies, contributing to improved scientific literacy and evidence-based decision-making.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Z.S.; validation, Z.S. and S.B.; formal analysis, Z.S.; resources, S.B.; data curation, Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.S. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, Z.S. and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Technical Report; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaridis, D.; Newell, J.P. The social anatomy of climate change denial in the United States. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, Z.; Jalali, R.; Shahbazi, Z. AI-Driven Framework for Evaluating Climate Misinformation and Data Quality on Social Media. Future Internet 2025, 17, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Countering Digital Hate. The New Climate Denial: How Social Media Platforms and Content Creators Are Mainstreaming Climate Change Misinformation; Technical Report; Center for Countering Digital Hate: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Saprikis, V.; Shahbazi, Z.; Christodoulou, V.; Bächtold, M.; Aharonson, V.; Nowaczyk, S. Video Engagement Effectiveness on Climate Change: An empirical investigation on university students. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 585, 04002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelle, D.; Bovet, A. The perils and promises of fact-checking with large language models. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 1341697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, Z.; Jalali, R.; Shahbazi, Z. AI-Driven Sentiment Analysis for Discovering Climate Change Impacts. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fore, M.; Singh, S.; Lee, C.; Pandey, A.; Anastasopoulos, A.; Stamoulis, D. Unlearning Climate Misinformation in Large Language Models. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leippold, M.; Vaghefi, S.A.; Stammbach, D.; Muccione, V.; Bingler, J.; Ni, J.; Colesanti Senni, C.; Wekhof, T.; Schimanski, T.; Gostlow, G.; et al. Automated fact-checking of climate claims with large language models. NPJ Clim. Action 2025, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanartu, F.; Otmakhova, Y.; Cook, J.; Frermann, L. Generative Debunking of Climate Misinformation. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webersinke, N.; Kraus, M.; Bingler, J.; Leippold, M. ClimateBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Climate-Related Text. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shu, K. Combating Misinformation in the Age of LLMs: Opportunities and Challenges. AI Mag. 2024, 45, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shu, K. Can LLM-Generated Misinformation Be Detected? In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, J.; Uchendu, A.; Yamashita, M.; Lee, J.; Rohatgi, S.; Lee, D. Fighting Fire with Fire: The Dual Role of LLMs in Crafting and Detecting Elusive Disinformation. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Feng, S.; Tan, Z.; Wang, H.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Luo, M. DELL: Generating Reactions and Explanations for LLM-Based Misinformation Detection. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 2637–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yi, J.; Yu, P.; Xu, X. Unmasking Digital Falsehoods: A Comparative Analysis of LLM-Based Misinformation Detection Strategies. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE), Shanghai, China, 21–23 March 2025; pp. 2470–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zheng, W.; Tang, X. Debate-to-Detect: Reformulating Misinformation Detection as a Real-World Debate with Large Language Models. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.B.; Thapa, S.; Acharya, A.; Rauniyar, K.; Poudel, S.; Jain, S.; Masood, A.; Naseem, U. Navigating the Web of Disinformation and Misinformation: Large Language Models as Double-Edged Swords. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 169262–169282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardalov, M.; Arora, A.; Nakov, P.; Augenstein, I. A Survey on Stance Detection for Mis- and Disinformation Identification. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhao, J.; Liang, B.; Gui, L.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X.; Liang, X.; Wong, K.F.; Xu, R. Mitigating Biases of Large Language Models in Stance Detection with Counterfactual Augmented Calibration. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 7075–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulhanty, C.; Deglint, J.L.; Ben Daya, I.; Wong, A. Taking a Stance on Fake News: Towards Automatic Disinformation Assessment via Deep Bidirectional Transformer Language Models for Stance Detection. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, M.A.; Chang, P.; Ma, M.; Pflugfelder, B.; Miletić, F. RAGAR, Your Falsehood Radar: RAG-Augmented Reasoning for Political Fact-Checking using Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Sun, L. Benchmarking Large Language Models in Retrieval-Augmented Generation. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.J.; Yu, H.; Orlovskiy, Y.; Vergho, T.; Rivera, M.; Goel, M.; Yang, Z.; Godbout, J.F.; Rabbany, R.; Pelrine, K. Web Retrieval Agents for Evidence-Based Misinformation Detection. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Galley, M.; He, P.; Cheng, H.; Xie, Y.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Liden, L.; Yu, Z.; Chen, W.; et al. Check Your Facts and Try Again: Improving Large Language Models with External Knowledge and Automated Feedback. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Yen, H.; Yu, J.; Chen, D. Enabling Large Language Models to Generate Text with Citations. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Zeng, H.; Shang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D. Retrieval Augmented Fact Verification by Synthesizing Contrastive Arguments. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vykopal, I.; Hyben, M.; Moro, R.; Gregor, M.; Simko, J. A Generative-AI-Driven Claim Retrieval System Capable of Detecting and Retrieving Claims from Social Media Platforms in Multiple Languages. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.C.; Ferrara, E. FACT-GPT: Fact-Checking Augmentation via Claim Matching with LLMs. In Proceedings of the WWW’24: Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference, Singapore, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 883–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.C.; Ferrara, E. Automated Claim Matching with Large Language Models: Empowering Fact-Checkers in the Fight Against Misinformation. In Proceedings of the WWW’24: Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference, Singapore, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, W. Towards LLM-based Fact Verification on News Claims with a Hierarchical Step-by-Step Prompting Method. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hu, L.; Li, R.; Fu, W. LoCal: Logical and Causal Fact-Checking with LLM-Based Multi-Agents. In Proceedings of the WWW’25: Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 1614–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.; Rodrigues, P.; Novak, V. Accenture at CheckThat! 2020: If you say so: Post-hoc fact-checking of claims using transformer-based models. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Gong, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wei, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, K. LLM Factoscope: Uncovering LLMs’ Factual Discernment through Measuring Inner States. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 10218–10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadeeva, E.; Rubashevskii, A.; Shelmanov, A.; Petrakov, S.; Li, H.; Mubarak, H.; Tsymbalov, E.; Kuzmin, G.; Panchenko, A.; Baldwin, T.; et al. Fact-Checking the Output of Large Language Models via Token-Level Uncertainty Quantification. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebi, S.; Müller-Budack, E.; Ewerth, R. Multimodal Misinformation Detection using Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Boise, ID, USA, 21–25 October 2024; pp. 2189–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Sheng, Q.; Hu, X. Preventing and Detecting Misinformation Generated by Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 3001–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.