Abstract

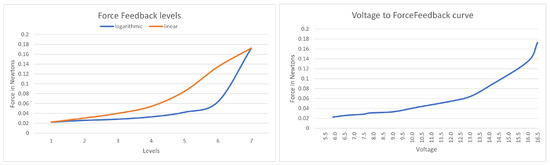

This paper investigates the versatility of force feedback (FF) technology in enhancing user interfaces across a spectrum of applications. We delve into the human finger pad’s sensitivity to FF stimuli, which is critical to the development of intuitive and responsive controls in sectors such as medicine, where precision is paramount, and entertainment, where immersive experiences are sought. The study presents a case study in the automotive domain, where FF technology was implemented to simulate mechanical button presses, reducing the JND FF levels that were between 0.04 N and 0.054 N to the JND levels of 0.254 and 0.298 when using a linear force feedback scale and those that were 0.028 N and 0.033 N to the JND levels of 0.074 and 0.164 when using a logarithmic force scale. The results demonstrate the technology’s efficacy and potential for widespread adoption in various industries, underscoring its significance in the evolution of haptic feedback systems.

1. Introduction

In the fundamental paper “The Intelligent Hand” presented by Klatzky Lederman [1], the authors begin the presentation of the general theory of haptic apprehension with the following two statements: “Haptics is very poor at apprehending spatial-layout information in a two-dimensional plane”, and “Haptics is very good at learning about and recognizing three-dimensional objects”. We seek to understand our primary research question: Do these statements continue to be valid in regard to what is experienced through a single touch?

Let us imagine that the finger pad is a small window on the fascinating world of sensations. But before a human is able to comprehend the endless variety of sensations, they must learn to explore and properly interpret cues available at a single point of touch by linking this afferent flow to that of haptic imagination. When a person’s haptic imagination is at a mature enough level, it is no longer necessary to stimulate the finger pad to induce the sense, as it will be possible to do so directly in the person’s imagination.

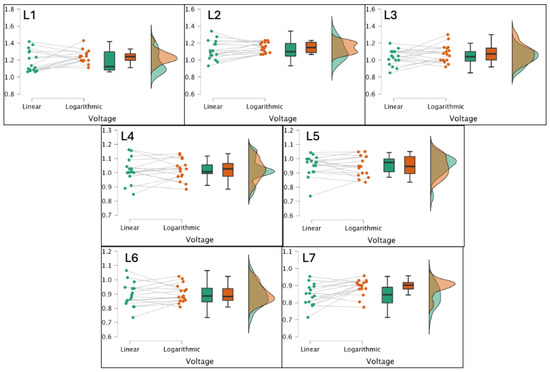

It is well known that human finger pads have thousands of receptors (mechanoreceptors, nociceptors and thermoreceptors). However, there are no special organs (cells or formations) in the human skin specifically sensitive to vibration, acceleration, gravity or other physical parameters, including electrical current or magnetic fields, as one might erroneously believe. Most mechanoreceptors located inside the dermis can perceive only mechanical energy as pressure force and micro-displacements translated by surrounding dermal tissues to the nerve endings and special cells/corpuscles (Meissner, Merkel, Pacinian, Ruffini and Krause end bulb) aggregated into heterogeneous receptive fields (Figure 1) with multiple highly sensitive zones distributed within an area typically covering five to ten fingerprint ridges [2].

Figure 1.

A schematic imaging of the fingerprint area, with skin ridges (a) and receptive fields (b) of sensory neurons (adapted from Jarocka et al. [2]).

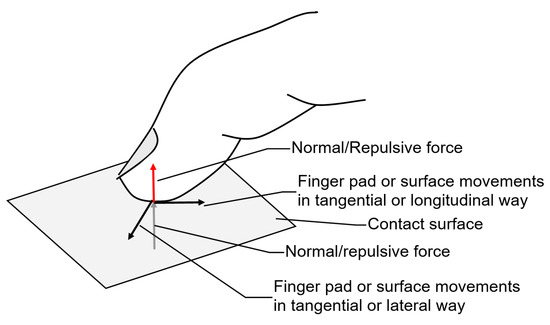

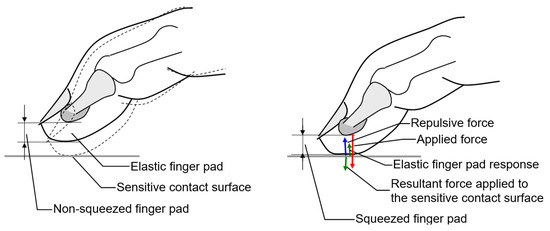

As such, we have not found related research on the comparative morphology or evolution of receptive fields on the finger pads of primates vs. humans. Since receptive fields are morphological formations [3], we can suppose that they emerged and evolved due to the optimization of afferent flow processing during continuous exploration of external objects. The exploration of objects relies on a limited number of available parsing signals or physical parameters, namely, the force applied during exploration. The exploration of the contact surface may happen when a sensitive surface of the finger pad comes into a direct contact with the external object by pushing against the contact location or when the contact surface of the object moves with respect to the finger pad. In these cases, the finger pad produces the initial force against the contact surface in the direction of the surface, thus generating repulsive force according to the surface or object physical properties (Figure 2). Exploration movements or finger pad relative displacements in the vicinity of the contact location might happen at least in two orthogonal directions (lateral and longitudinal) both tangential in respect of the applied normal force.

Figure 2.

The force accompanying the finger pad interactions with a contact surface.

Let us consider in more detail the forces acting at the contact location. We could refer to a structural biomechanics presented by Wu and co-authors [4] and Gerling and Thomas [5], or anatomical details disclosed by Bolanowski, and Pawson [6], but what is more important in further considerations is the dynamic ratio of force components acting within the finger pad and in vicinity of the contact location (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forces exerted by the finger pad and experienced by the user at the point of contact.

The finger pad, or fingertip, is acting against a contact surface featuring embedded pressure sensors to detect parameters of the physical impact at the place of contact. Tools such as doppler scanners are able to detect the surface deformation and micro-displacements at the place of contact with high resolution and accuracy in micrometers and in the absence of direct contact [7].

Nevertheless, the elasticity of the fingertip experiences strain by squeezing the tissues against the bone of the distal phalanx and the nail [8]. And, as the authors rightly pointed out, “Encoding fingertip forces in afferents that terminate dorsally in the fingertip might be advantageous because fine-form features of the contacted surfaces would influence the afferent signals less than with afferents terminating in the finger pulp”. Thus, the resultant force applied to the contact surface is the vector sum of the applied force by the user at exploration minus the repulsive force exerted by the contact surface and the elastic finger pad’s response. The array of resultant forces distributed within vicinity of the finger pad contact location or fingertip contact point dynamically changes by generating a complex ensemble of afferents [9] of the nearest dermal receptive fields and tactile afferents, conveying information about contact forces in sync with the kinesthetic flow in accordance to exploration behavior [8].

Force discrimination ability is an important perceptual sense that can maintain high-precision dexterous manipulations due to the force feedback (FF) loop directly at the level of skin mechanoreceptors [2], as well as due to the proprioceptors embedded in the muscles, tendons and ligaments. FF is important for many types of surgical manipulations, especially in microsurgery when performing delicate manipulations with thin living structures, for instance, as in assisted reproductive technology. Forces applied in in vivo experiments with soft tissue and minimally invasive surgeries can vary between 0 and 2.5 N [10,11], including, in some neurosurgical tasks, forces smaller than 0.3 N [12].

Psychophysics quantitatively sets the relationship between the physical signals inducing the sensations and the cognitive processes shaping perception, i.e., between the parameters related to physical world exploration and psychological concepts. In psychophysics, just-noticeable difference (JND) is a quantitative measure that is defined as the relative smallest change () in regard to the stimulus intensity () inducing changes in stimulus perception [13]. JND usually has no unit of measurement (JND = /()). According to Weber’s law, at least, at forces greater than 2 N, the human ability to perceive changes in a stimulus is proportional to the intensity of the stimulus, and it is a constant value known as Weber fraction, according to Gescheider [14]. However, the detection of stimuli at very low intensities does not adhere to Weber’s law [9]. Close to the absolute threshold, JND is significantly large and exhibits an inverse relationship with the intensity of the stimulus.

A group of researchers from University of Toronto [15] examined the human hand’s force perception abilities in subjects having different hand sensitivity by virtue of their vocational training, i.e., surgeons and non-surgeons, near the absolute perceptual threshold for the forces that do not follow Weber’s law (0.1 N, 0.3 N, 0.6 N and 0.8 N).

The equation presented below suggests that the difference threshold for low-intensity forces does not maintain a steady proportion of the reference force. Instead, this proportion is inherently dependent on the reference stimulus itself. Consequently, employing the model of JND as a basis for developing the force scaling function is a logical approach.

A similar approach was also recently pursued by Botturi et al. [16]. The proposed force feedback scaling function is

As explained by Botturi, is the force at the slave-environment interface, and is the force fed back to the master device (). The function () indicates that the scaling factor is a function of the sensed force at the slave interface.

2. Research on Force Feedback Applications at JND Level

As demonstrated in [17] (Evreinov, 2005), the two-handed manipulation of analog buttons (by pressing them with the thumbs) can provide accurate target (12 × 12 pixels or 4 × 4 mm) acquisition within the working field of the screen (768 × 768 pixels 252 × 252 mm) when bimanual cursor pointing (on the X- and Y-axes accordingly) does not exceed a range ±2 mm of physical button displacements. This implies that FF as low as 0.15 N of the JND step in a range between 0.1 N and 1.5 N can provide only 10% of input accuracy based on FF and button displacements of ±0.2 mm. When combined with visual feedback, the system can achieve a resolution accuracy within ±5 pixels, or approximately ±1.3%. This means that by using additional feedback methods, the precision of using both hands to point the cursor can be improved to around 3.9%, which matches a force feedback intensity of 60 mN.

By exploring JND force perception during the pressing of a button in the range 0.5–2.5 N of the reference force, Doerrer and Werthschützky (2002) [18] revealed that on average, participants were able to perceive a sudden change in FF larger than 100 mN. However, in relation to the reference forces between 0.5 N and 2.5 N, the just-noticeable relative force differences were of 20% to 5% lower. Within the range of 1.5 N–2.5 N, the determined mean JND was lower by 7.5% and 5.5%. These results were consistent with the earlier-presented values of 5%–10% as stated by Tan et al. (1992) [19].

The study of the psychophysical perception of distributed pressure forces upon exploration by fingertips has long been of interest [7,19,20,21,22,23]. Rørvik and co-authors [24] investigated whether untrained people could locate and determine by palpation the shapes and hardness of irregularities rendered between two compliant layers by using the ferrogranular jamming principle.

Evreinov and Raisamo (2005) [25] investigated how untrained subjects were able to memorize and reproduce a week later a sequence of four dynamic patterns of distributed pressure profiles (Figure 1). The pressure levels varied within compression and dilatation phases from 10 N to 0.15 N, taking in total about 300 ms for each of four behavioral patterns of distributed pressure profiles. The study proved that untrained subjects were able to memorize the four dynamic patterns of self-sense profiles of the fingertip and reproduce them a week later with high accuracy.

In their PopTouch thin-film array of dynamically reconfigured physical buttons, Firouzeh [26] used hydraulically amplified self-healing electrostatic (HASEL) stretchable caps. Each button produced a 1.5 mm out-of-plane displacement and supported holding force up to 1.5 N before sudden snap-through, providing an instinctive “click” sensation akin to that of a pushbutton.

Recently, Shultz and Harrison [27] introduced a haptic display that utilizes a series of electro-osmotic micropumps, each dedicated to a single button. This device is capable of producing an out-of-plane displacement of up to 6 mm, and it can exert a force exceeding 1 N for a button cap with a diameter of 10 mm. However, the device’s stiffness, its 5 mm thickness and substantial energy demand (1–2 W/) restrict its practical applications. Additionally, the device’s lack of transparency hinders its incorporation into touchscreen interfaces.

Using multi-layered dielectric elastomer (MLDE), Lee and colleagues [28] developed a 20 mm diameter, 1.5 mm thick haptic actuator that can generate 2 mm out-of-plane displacement at 250 mN holding force. While being effective in providing skin stimulation at direct contact, a higher holding force (around 1 N) is required to simulate actions over various physical buttons.

Rekimoto and co-authors (2003) [29] proposed to complement the pressure-based input with a capacitive sensor at the contact location. However, as stated earlier by Hinckley and Sinclair (1999) [30] regarding capacitive sensors that require zero activation force to trigger the contact, “they may be prone to accidental activation due to inadvertent contact”. Therefore, to differentiate inadvertent pressure changes from JND signals that must support precise dexterous control in some applications, other authors have studied the specific conditions of use in mobile devices and interaction techniques, when pressure variation can impact the interpretation of the perceived force signals.

For instance, Stewart et al. [31] shared findings from a preliminary investigation into accidental changes in grip pressure on mobile devices, observed under both stationary laboratory conditions and while walking, with significant pressure fluctuations noted in each scenario. The study utilized the FSR-402 sensor in experimental setups, observing pressure variations from 0.1 N to 3–10 N, a range supported by the sensor and deemed ergonomically suitable for fingertip pressure examinations. However, to make use of pressure inputs effectively, they suggested filtering out accidental variations by integrating pressure measurements with accelerometer data. Given that unintentional pressure changes typically fell between 0 and 0.6 N, setting thresholds beyond 0.6 N was recommended for reliable detection of deliberate pressure inputs.

Though Rekimoto and Schwesig (2006) [32] demonstrated only a 3-level pressure-based button (“not pressed”, “light-pressed” and “hard-pressed”), providing tactile feedback upon crossing these levels, the results of various studies of the pressure sense as an auxiliary input modality [17,31,33,34,35,36] have shown that users can distinguish and apply up to 10 pressure levels with high degrees of accuracy when navigating through different types of menus with visual and audio feedback.

Stewart and their team [35] conducted a series of experiments to understand fundamental aspects of pressure-based interaction. In particular, they tried to assess a single-sided input [25] against grasping pressure delivered through a two-sided interaction paradigm, studying the controllability of pressure by the fingertip at different levels for a greater period of time (e.g., for five seconds rather than a single pressure pattern). In (Evreinov 2005) [17], dwell time for target acquisition was used for an uninterrupted period of only 300 ms. The results [35,37] suggested that using a grasping motion is more effective than a one-sided input and rivals the efficiency of pressure input when applied to solid surfaces.

Liao and colleagues developed the Button Simulator [38], a device that can simulate the physical button action by employing any given force–displacement curve. The Button Simulator had a low average error offset of around 0.034 N, meaning that the simulated force was very close to the actual force expected. However, the simulated sensation was not perceived as realistic when the button was pressed too fast. Additional research demonstrated that the deformation of the skin caused by the tangential force on the fingertip can be expressed by using a spring–mass–damper model, indicating a linear relationship between deformation and force [39]. Research by Kaaresoja at Nokia focused on the implementation of vibrotactile feedback accompanied by visual and audio feedback to find latency thresholds required to make virtual button presses feel natural [40].

Recent studies have reinforced the value of force feedback systems across various applications, particularly in enhancing user experience and performance in high-precision tasks. For instance, the integration of force feedback in virtual reality for medical planning has shown promise in simulating surgical procedures like clamping in colorectal surgery, highlighting the system’s potential in medical training [41]. Moreover, a meta-analysis on robot-assisted surgery quantified the benefits of haptic feedback, revealing significant improvements in surgical accuracy and a reduction in the force applied by surgeons [42]. Another innovative approach involves a sensorless feedback system that aids surgeons in distinguishing among different tissue types during laparoscopic surgery, with a high success rate in tumor identification [43]. These studies show the effectiveness of force feedback technologies in providing realistic tactile sensations that can improve outcomes in medical settings.

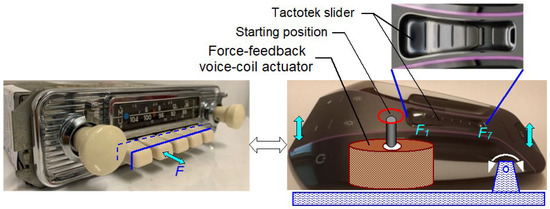

These diverse approaches, ranging from tactile feedback mechanisms to advanced sensory stimulation technologies, collectively advance the field of virtual button design, offering innovative solutions that enhance user interaction in multimedia applications, especially in contexts where visual attention is limited, like driving. We hypothesized that the repulsive FF at the JND level can be used for simulating the sense of pushbutton bank switches.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

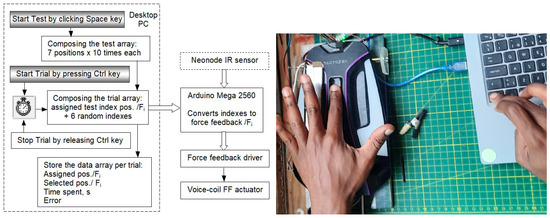

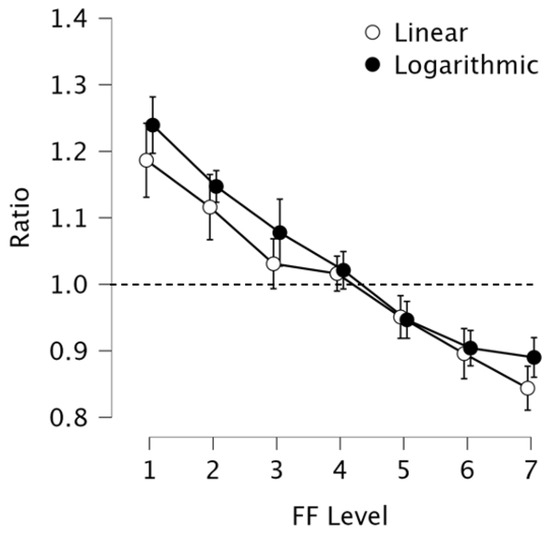

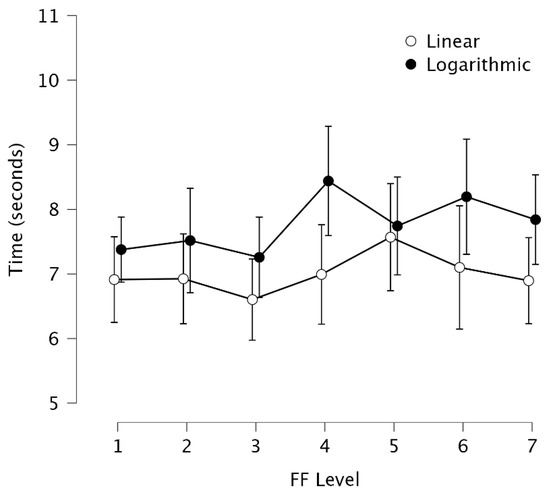

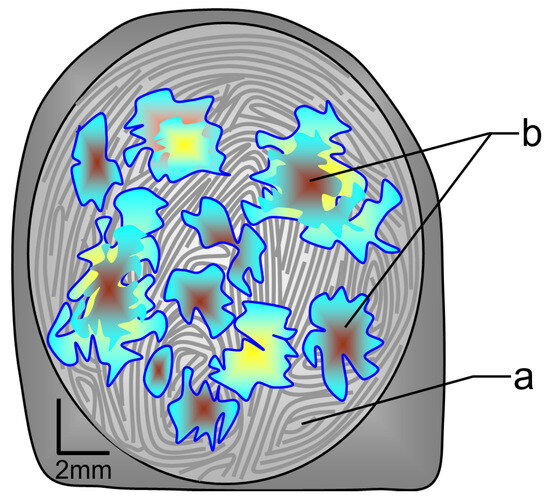

In this paper, we investigated the repulsive force feedback (FF) at the JND level used for simulating the sense of pushbutton bank switches and the performance of participants interacting with a touch-sensitive slider. The participants were asked to locate and select different zones on the slider based on the FF levels they felt. The participants could identify accurately FF levels that were between 0.04 N and 0.054 N at the JND levels of 0.254 and 0.298 for the linear scale and those that were between 0.028 N and 0.033 N at the JND levels of 0.074 and 0.164 for the logarithmic scale. They overestimated values below this range and underestimated values above this range. The NASA-TLX scores indicate that the participants experienced a moderate level of workload during the task. While mental demand was slightly above average, physical demand and temporal demand were relatively low, suggesting that the task was more mentally taxing than physically demanding or time-pressured. The modest scores in performance and the mild effort level indicate that participants found the task somewhat challenging but not overly so. The low level of frustration further suggests that the task did not induce significant emotional strain.

Integrating these results, the system demonstrates a high level of practical efficacy. The accuracy in identifying FF levels, despite some perceptual challenges at specific levels, indicates robust sensory response capabilities. The consistent response times across varying FF intensities ensure reliable and predictable interaction, which is crucial to user satisfaction and system reliability. Moreover, the moderate workload reported by the participants suggests that the system is user-friendly and does not impose excessive cognitive or physical stress.

In the automotive industry, FF technology is being used to create more intuitive and safer control systems for drivers. For example, haptic feedback can improve the effectiveness of touch screens and controls, reducing driver distraction and increasing engagement [66]. The current trajectory in automotive design indicates a continued and widespread adoption of capacitive touch controls in consumer vehicles, a trend that is expected to persist well into the future [67]. Despite advancements, the reality of consumer-accessible Level IV autonomous vehicles, which would eliminate the need for an attentive driver, remains distant [68]. This underscores the critical need for ongoing research into making existing touch controls safer and more user-friendly for drivers. Our study contributes to this area by demonstrating the potential of force feedback across the Tactotek touch-sensitive slider’s seven distinct locations to enhance the user interface.

External factors, such as ambient noise, lighting and environmental stressors, can significantly impact the effectiveness of force feedback systems. Our experiment was conducted in a controlled laboratory environment, allowing the participants to concentrate solely on the task and the interface. However, real-world driving involves several distractions and environmental factors—traffic, weather conditions, radio noise, passengers, etc. Ambient noise, for instance, can distract users or mask the auditory feedback that often accompanies haptic interfaces, potentially reducing the user’s ability to respond to tactile cues. Inadequate lighting may strain the user’s vision, leading to fatigue and decreased interaction accuracy with the force feedback system. Moreover, environmental stressors, including temperature fluctuations and vibrations, could interfere the user’s sensory perception, thus affecting performance. To ensure optimal deployment of force feedback systems under real-world conditions, it is essential to consider these external factors. Guidelines could include recommendations for noise-dampening features, adjustable lighting and robust system designs that can withstand environmental variances.

To build upon our findings and address these real-world complexities, we propose several avenues for future research. One key area involves exploring various configurations of the touch-sensitive slider, particularly experimenting with different numbers of zones to identify an optimal setup that maximizes user experience and performance.

It is essential to consider the interplay between user comfort and control accuracy. Tactile experience is greatly influenced by the materials used; soft-touch materials often enhance comfort for prolonged use, while harder materials might be favored for their precise feedback capabilities. Investigating the impact of different overlay materials on the slider could offer insights into how these materials influence the perception and discrimination of FF levels. For instance, Teflon has shown potential in enhancing vibrotactile signals [7], suggesting that material choice could be a critical factor in design considerations.

The study’s exploration into the realm of FF technology could be significantly enriched by delving into additional applications, such as virtual reality (VR) and remote surgery. In VR, FF can transcend the visual and auditory immersion by introducing a tangible dimension, allowing users to "feel" the virtual environment, thus enhancing the realism and depth of the experience. Similarly, in the context of remote surgery, FF becomes a pivotal component, providing surgeons with the necessary tactile feedback that is otherwise lost in teleoperated procedures. This haptic information can be crucial to delicate surgical maneuvers, potentially increasing precision and reducing the risk of errors. By expanding the scope of research to include these applications, research could uncover new insights into the capabilities and limitations of FF technology.

These directions aim not only to refine touch interface technology for current vehicles but also to prepare for the evolving landscape of automotive user experience as we progress towards higher levels of vehicle autonomy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C. and G.E.; software, P.C. and G.E.; validation, P.C., G.E. and M.Z.; formal analysis, P.C., G.E. and M.Z.; investigation, P.C.; resources, R.R.; data curation, G.E. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.; writing—review and editing, G.E., M.Z. and R.R.; visualization, G.E. and M.Z.; supervision, G.E. and R.R.; project administration, R.R.; funding acquisition, R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by project Adaptive Multimodal In-Car Interaction (AMICI), funded by Business Finland grant number [1316/31/2021].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Klatzky, R.L.; Lederman, S.J. The intelligent hand. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; Volume 21, pp. 121–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jarocka, E.; Pruszynski, J.A.; Johansson, R.S. Human touch receptors are sensitive to spatial details on the scale of single fingerprint ridges. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 3622–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detorakis, G.I.; Rougier, N.P. Structure of receptive fields in a computational model of area 3b of primary sensory cortex. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Dong, R.G.; Rakheja, S.; Schopper, A.; Smutz, W. A structural fingertip model for simulating of the biomechanics of tactile sensation. Med. Eng. Phys. 2004, 26, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerling, G.J.; Thomas, G.W. The effect of fingertip microstructures on tactile edge perception. In Proceedings of the First Joint Eurohaptics Conference and Symposium on Haptic Interfaces for Virtual Environment and Teleoperator Systems. World Haptics Conference, Pisa, Italy, 18–20 March 2005; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bolanowski, S.J.; Pawson, L. Organization of Meissner corpuscles in the glabrous skin of monkey and cat. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 2003, 20, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, P.; Evreinov, G.; Raisamo, R. The Impact of Different Overlay Materials on the Tactile Detection of Virtual Straight Lines. Multim. Tech. Inter. 2023, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birznieks, I.; Macefield, V.G.; Westling, G.; Johansson, R.S. Slowly adapting mechanoreceptors in the borders of the human fingernail encode fingertip forces. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 9370–9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.A. Matching forces: Constant errors and differential thresholds. Perception 1989, 18, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, P.; Székely, G.; Kósa, G. Miniature tri-axial force sensor for feedback in minimally invasive surgery. In Proceedings of the 2012 4th IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), Rome, Italy, 24–27 June 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Peirs, J.; Clijnen, J.; Reynaerts, D.; Van Brussel, H.; Herijgers, P.; Corteville, B.; Boone, S. A micro optical force sensor for force feedback during minimally invasive robotic surgery. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2004, 115, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.S.; Zareinia, K.; Lama, S.; Maddahi, Y.; Yang, F.W.; Sutherland, G.R. Quantification of forces during a neurosurgical procedure: A pilot study. World Neurosurg. 2015, 84, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenstein, W.H.; Ehrenstein, A. Psychophysical methods. In Modern Techniques in Neuroscience Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 1211–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Gescheider, G.A. Psychophysics: The Fundamentals; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khabbaz, F.H.; Goldenberg, A.; Drake, J. Force discrimination ability of the human hand near absolute threshold for the design of force feedback systems in teleoperations. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2016, 25, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botturi, D.; Galvan, S.; Vicentini, M.; Secchi, C. Perception-centric force scaling function for stable bilateral interaction. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 4051–4056. [Google Scholar]

- Evreinov, G. Bimanual Input and Patterns of User Behavior. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Methods and Techniques in Behavioral Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 30 August–2 September 2005; pp. 571–572. [Google Scholar]

- Doerrer, C.; Werthschuetzky, R. Simulating push-buttons using a haptic display: Requirements on force resolution and force-displacement curve. In Proceedings of the EuroHaptics, Edinburgh, UK, 8–10 July 2002; pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.Z.; Pang, X.D.; Durlach, N.I. Manual resolution of length, force, and compliance. Adv. Robot. 1992, 42, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, M.A.; LaMotte, R.H. Tactual discrimination of softness. J. Neurophysiol. 1995, 73, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederman, S.J.; Klatzky, R.L. Extracting object properties through haptic exploration. Acta Psychol. 1993, 84, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelevé, A.; McDaniel, T.; Rossa, C. Haptic training simulation. Front. Virtual Real. 2020, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, P.; Evreinov, G.; Ziat, M.; Raisamo, R. A Universal Volumetric Haptic Actuation Platform. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rørvik, S.B.; Auflem, M.; Dybvik, H.; Steinert, M. Perception by palpation: Development and testing of a haptic ferrogranular jamming surface. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 745234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evreinov, G.; Raisamo, R. One-directional position-sensitive force transducer based on EMFi. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2005, 123, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzeh, A.; Mizutani, A.; Groten, J.; Zirkl, M.; Shea, H. PopTouch: A Submillimeter Thick Dynamically Reconfigured Haptic Interface with Pressable Buttons. Adv. Mater. 2023, 36, 2307636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, C.; Harrison, C. Flat Panel Haptics: Embedded Electroosmotic Pumps for Scalable Shape Displays. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Cohen, A.J.; Vogt, D.M.; Kollosche, M.; Lansberry, G.; Mengüç, Y.; Israr, A.; Clarke, D.R.; Wood, R.J. A wearable textile-embedded dielectric elastomer actuator haptic display. Soft Robot. 2022, 9, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekimoto, J.; Ishizawa, T.; Schwesig, C.; Oba, H. PreSense: Interaction techniques for finger sensing input devices. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–5 November 2003; pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hinckley, K.; Sinclair, M. Touch-sensing input devices. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 15–20 May 1999; pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, C.; Hoggan, E.; Haverinen, L.; Salamin, H.; Jacucci, G. An exploration of inadvertent variations in mobile pressure input. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, San Francisco, CA, USA, 21–24 September 2012; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rekimoto, J.; Schwesig, C. PreSenseII: Bi-directional touch and pressure sensing interactions with tactile feedback. In Proceedings of the CHI’06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 April 2006; pp. 1253–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Evreinov, G.; Evreinova, T.; Preusche, C.; Hulin, T.; Raisamo, R. Surgical Knot Tying Skills: Training the Novices in an Asymmetric Bimanual Task. In Proceedings of the SKILLS09-Enaction on SKILLS: The International Conference on Multimodal Interfaces for Skills Transfer, Bilbao Éxhibition Center, Barakaldo, Spain, 15–16 December 2009; pp. 187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, S.A.; Hughes, M. Pressure-based text entry for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Bonn, Germany, 15–18 September 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, C.; Rohs, M.; Kratz, S.; Essl, G. Characteristics of pressure-based input for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; pp. 801–810. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.; Brewster, S.A.; Halvey, M.; Crossan, A.; Stewart, C. The effects of walking, feedback and control method on pressure-based interaction. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Stockholm, Sweden, 30 August–2 September 2011; pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Essl, G.; Rohs, M.; Kratz, S. Squeezing the sandwich: A mobile pressure-sensitive two-sided multi-touch prototype. In Proceedings of the Demonstration at UIST’09, Victoria, BC, Canada, 4–7 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.C.; Kim, S.; Oulasvirta, A. One button to rule them all: Rendering arbitrary force-displacement curves. In Proceedings of the Adjunct: Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Berlin, Germany, 14–17 October 2018; pp. 111–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S.; Okamoto, S.; Matsuura, Y.; Yamada, Y. Wearable finger pad deformation sensor for tactile textures in frequency domain by using accelerometer on finger side. ROBOMECH J. 2017, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaaresoja, T.; Brewster, S.; Lantz, V. Towards the temporally perfect virtual button: Touch-feedback simultaneity and perceived quality in mobile touchscreen press interactions. Acm Trans. Appl. Percept. 2014, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bici, M.; Guachi, R.; Bini, F.; Mani, S.F.; Campana, F.; Marinozzi, F. Endo-Surgical Force Feedback System Design for Virtual Reality Applications in Medical Planning. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholz, M.; Ferle, M.; Weber, B.M. The benefits of haptic feedback in robot assisted surgery and their moderators: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Nelson, C.A. A sensorless force-feedback system for robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2019, 24, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kwon, S.; Heo, J.; Lee, H.; Chung, M.K. The effect of touch-key size on the usability of In-Vehicle Information Systems and driving safety during simulated driving. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzinger, A. Finger instead of mouse: Touch screens as a means of enhancing universal access. In Proceedings of the ERCIM Workshop on UI for All, Paris, France, 23–25 October 2002; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, B.; Conzola, V. Designing touch screen numeric keypads: Effects of finger size, key size, and key spacing. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1 October 1997; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1997; Volume 41, pp. 360–364. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Ye, Z. Automotive display trend and tianma’s directions. In Proceedings of the 2019 26th International Workshop on Active-Matrix Flatpanel Displays and Devices (AM-FPD), Kyoto, Japan, 2–5 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 26, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Frediani, G.; Carpi, F. Tactile display of softness on fingertip. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landymore, F. Death to Car Touchscreens, Buttons Are Back, Baby! 2023. Available online: https://futurism.com/the-byte/car-touchscreens-buttons-back (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Zipper, D. The Glorious Return of an Old-School Car Feature. 2023. Available online: https://slate.com/business/2023/04/cars-buttons-touch-screens-vw-porsche-nissan-hyundai.html (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Suh, Y.; Ferris, T.K. On-road evaluation of in-vehicle interface characteristics and their effects on performance of visual detection on the road and manual entry. Hum. Factors 2019, 61, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, D.; Yuan, J.; Liu, S.; Qu, X. Effects of button design characteristics on performance and perceptions of touchscreen use. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2018, 64, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.S.; Im, Y. Touchable area: An empirical study on design approach considering perception size and touch input behavior. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 49, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Park, J.; Dai, S.; Tan, H.Z. Design and evaluation of identifiable key-click signals for mobile devices. IEEE Transac. Haptics 2011, 4, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Visual-Manual NHTSA Driver Distraction Guidelines for in-Vehicle Electronic Devices; Docket No. NHTSA-2014-0088; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vikström, F.D. Physical buttons outperform touchscreens in new cars, test finds. Vi Bilägare, 20 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nayyar, A.; Puri, V. A review of Arduino board’s, Lilypad’s & Arduino shields. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom); New Delhi, India, 16–18 March 2016, IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1485–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, P. Force Sensors. In Selected Sensor Circuits: From Data Sheet to Simulation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck, P.J.; Schultz, P.W.; O’brien, P.C. Quantitation of touch-pressure sensation. Arch. Neurol. 1972, 26, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindblom, U. Touch perception threshold in human glabrous skin in terms of displacement amplitude on stimulation with single mechanical pulses. Brain Res. 1974, 82, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neonode. Specifications Summary. Available online: https://support.neonode.com/docs/display/AIRTSUsersGuide/Specifications+Summary (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Shao, Y.; Hayward, V.; Visell, Y. Spatial patterns of cutaneous vibration during whole-hand haptic interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4188–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enferad, E.; Giraud-Audine, C.; Giraud, F.; Amberg, M.; Semail, B.L. Generating controlled localized stimulations on haptic displays by modal superimposition. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 449, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantera, L.; Hudin, C. Sparse actuator array combined with inverse filter for multitouch vibrotactile stimulation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE World Haptics Conference (WHC), Tokyo, Japan, 9–12 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hudin, C.; Lozada, J.; Hayward, V. Localized tactile feedback on a transparent surface through time-reversal wave focusing. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2015, 8, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banter, B. Touch screens and touch surfaces are enriched by haptic force-feedback. Inf. Disp. 2010, 26, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C. Design of the In-Vehicle Experience; Technical Report, SAE Tech. Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shladover, S.E. The truth about “self-driving” cars. SCI AM, 1 December 2016; Volume 314. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).