Abstract

Sustainable natural resource management is a high priority in the 21st century as it plays a crucial role in mitigating climate change and preventing some of its consequences like loss of biodiversity, land degradation, desertification, and the exhaustion of natural resources. This concern is reflected in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which emphasize, among other factors, sustainable cities and communities, responsible production and consumption, and climate action. Achieving sustainable natural resource management begins with raising awareness and educating the next generation. Therefore, it is essential to develop educational initiatives that prepare young people to become responsible and proactive adults in promoting environmental sustainability across industries and communities. Additionally, these initiatives should develop critical and analytical thinking skills, nurture innovative mindsets for creating environmentally sound solutions, and enhance the ability to collaborate within multidisciplinary teams. The NATURE project addressed these needs by designing and developing a serious educational game that fosters this set of skills. The results of the pilot testing show that the game is an effective tool and contributes to the education and awareness of the younger generation.

1. Introduction

The responsible management of natural resources, including land, water, air, minerals, forests, and biodiversity, has a direct impact on the quality of life of present and future generations as it creates a balance between social, economic, and environmental factors. It leads to the well-being of people and communities, the preservation of jobs, and the protection of biodiversity. The growing interest in the socioenvironmental problems that affect the world today led the United Nations General Assembly to publish in 2015 the action plan for the following decade [1]. The core of this Agenda is the set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) associated with 169 specific targets intended to transform society and mobilize people and countries in relation to a complex range of social, economic, and environmental challenges, which require major changes in the functioning of societies and economies. From this perspective, the SDGs seek to provide guidance for action to ensure a sustainable, peaceful, prosperous, and equitable life through universal, transformative, and inclusive approaches [2].

Subsequently, in November 2018, the European Commission presented its long-term strategic vision for a modern, competitive, and climate-neutral European economy by 2050 [3]. The European Commission’s vision for future EU policies was based on sustainable development, defined as a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. This was thought to be achievable with the harmonization of three key elements: economic growth, social inclusion, and the protection of the environment. The management of natural resources was expected to move towards responsible, fair, and sustainable production and consumption models. The European Green Deal aimed to protect, conserve, and enhance the EU’s natural capital and to protect the health and well-being of citizens from environment-related risks and impacts [4].

The increase in concern about the unsustainable exploitation of natural resources has promoted the appearance of a multitude of initiatives by diverse institutions and associations aimed at fostering the development of approaches of Education for a Sustainable Development (ESD) in all levels of formal, informal, and non-formal education [5]. ESD means including key sustainable development issues into teaching and learning, such as rural and urban development, economy, production, and consumption patterns, corporate responsibility, environmental protection, natural resource management, and biological and landscape diversity [6].

1.1. Current Approaches for Education for a Sustainable Development

For the initial levels of education, the formal education sector plays a vital role in raising the awareness of the younger generation by exposing them to the information and issues of sustainable development. As such, in most EU countries, educational state organizations (like Ministries of Education) created initiatives for promoting environmental education. Through them, students can learn to use their knowledge to interpret and evaluate the surrounding reality, formulate and discuss arguments, and support positions and options—fundamental skills for active participation in making informed decisions in a democratic society—regarding the effects of human activities on the environment. For instance, in Italy, the Ministry of the Environment and the Protection of the Territory and the Sea (MATTM) and the Ministry of Education, University, and Research (MIUR) jointly created the “Guidelines for environmental education and sustainable development” to provide some innovative guidelines for the elaboration of curricula by schools and the organization of educational and didactic activities based on students’ age, knowledge, and skills, structured into articulated learning paths:

- Protection of water and the sea (preschool, primary).

- Protection of biodiversity: flora and fauna (preschool, primary).

- Sustainable nutrition (preschool, primary, first-grade secondary, second-grade secondary school).

- Waste management (preschool, primary, first-grade secondary school).

- Protection of biodiversity: ecosystem services (first-grade secondary, second-grade secondary school).

- Green economy: green jobs and green talent (secondary school).

- The sustainable city: pollution, land and waste consumption (second-grade secondary school).

- Adaptation to climate change: hydrogeological instability (second-grade secondary school).

A wide range of private entities dedicated to informal and non-formal environmental education (environmental education companies and environmental NGOs) are also active in the process of creating and providing open content as a method directed at changing habits, attitudes, and social practices, seeking solutions for the social–environmental degradation afflicting the contemporary world. For instance, in Portugal, the Eco-Schools project is a program of education for sustainable development, promoted by the European Blue Flag Association (ABAE), the Portuguese section of the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE), and it has been running in more than 1500 schools throughout the country. There are also television and radio programs, such as “Minuto Verde” (Green Minute) on the public broadcast television RTP or “Um Minuto pela Terra” (One Minute for the Earth) on the public radiobroadcast Antena 1, that aim to raise awareness about the issue. In Greece, the Hellenic Oceanographers’ Association organized environmental education laboratories in primary and secondary schools, as well as environmental education laboratories for teachers, in collaboration with Centers of Environmental Education (CEE). In Spain, the Ministry of Ecological Transition is carrying out work through the National Reference Center for Environmental Education (CENEAM), introducing environmental education and volunteer programs. The NGO FSC Espana delivers training and communication projects focused on forest certification and the promotion of the Galician forestry industry while promoting good environmental practices in its forests and plantations.

At the higher education level, most initiatives are directed at formal programmes, and there is a limited availability of resources for informal education. As examples, in Portugal, the University of the Azores, the University of Lisbon, and the University of Evora provide Masters programmes in Nature Management and Conservation; the Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra provides a graduate degree in Management and Conservation of Ecosystems, and another in Environmental Technology and Management; in Italy, several Universities offer environmental education programs, such as the Università degli Studi di Napoli Suor Orsola Benincasa, the Università degli Studi di Roma “Tor Vergata”, the Università di Bologna, the Università di Siena, the VIU—Venice International University, and others; in Latvia, several Universities offer programmes in Environmental Science, like the University of Latvia, Riga Technical University, Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies, Daugavpils University, Liepaja University, and Rēzekne Academy of Technologies; in Estonia, formal education programmes are provided by Tallinn University, University of Tartu, Tallinn University of Technology, and the Estonian University of Life Sciences; and in Greece, environmental science study programs are provided in various universities such as the University of Aegean, the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the American College of Greece, and others. Unfortunately, although these are high-quality programmes that do provide the right perspective on environmental sustainability, they only cater to a very limited audience, and one that is already aware of the issue and wants to explore it scientifically.

1.2. Digital Approaches for Education

At the same time, the world has become increasingly digital, and digital technologies have assumed an increasingly important role in education, constituting themselves as important tools in the “acquisition and transfer of knowledge”, as well as in the “reform and transformation of the educational process” [7], and they have emerged as alternatives to face-to-face environmental education activities. The digital learning modality made it easier to access a diverse range of information and activities and allows us to explore these resources in an informal way in higher education [8,9,10].

The use of mobile technology, simulations, serious games, augmented reality, and virtual reality are some examples of advanced digital technologies that can be used for educational purposes to increase students’ interest in the topics covered [11,12,13]. Serious educational games can motivate users and allow for the study of various subjects in a stimulating and challenging way that generates immediate feedback [14]. In addition, game-based learning (defined as the use of serious games to foster learning) can improve skills such as critical thinking, creative problem solving, and teamwork, as well as increasing cognitive development, learning retention, and social learning [15,16,17]. Games provide opportunities for users to perform activities “in a safe environment where consequences are not real and where hypothesis testing is possible without fear” [18], which is quite relevant for ESD [19]. Students, as digital natives, find these learning methods more attractive [20,21].

The transition to an increasingly digital educational methodology brings, in turn, challenges for teachers in taking advantage of these more customizable and adaptable tools for learning [22]. In fact, the implementation of digital technologies in education is dependent on whether or not teachers are trained to include these tools in school activities. A study on the improvement of teachers’ ICT skills concluded that the use of these tools was often limited due to the teachers’ inadequate preparation in handling them [23]. In this sense, we can affirm that it is essential that teachers have adequate training in the use of technological educational materials in order to be able to apply them properly in the classroom. According to Neves, the integration of games and gamified activities in teaching practices is seen as “an alternative in which ICT is combined with the development of skills” [24].

1.3. The NATURE Project Concept

Environmental education in higher education often relies on traditional teaching methods that offer limited opportunities for practical, hands-on learning and fail to provide interactive experiences that help students develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills. The NATURE project addresses this need for new education tools by creating a serious educational game that allows students to apply their knowledge in simulated real-world scenarios. This experiential learning intervention builds awareness, knowledge, and skills in responsible natural resources management through digital experimentation that engages students in scenarios that they would not be exposed to through off-line activities. Through this approach, the project aimed to achieve the following objectives:

- Educating students: Building theoretical knowledge and soft skills applicable to responsible natural resources management. Building their awareness of the importance of sustainable natural resources management for the well-being of communities and plant and animal species.

- Training instructors: Supporting the seamless integration of the proposed experiential learning design and digital learning games in existing instructional practices through reference material in diverse media.

- Modernizing higher education through digital technologies: Developing an open digital game developed specifically for learning purposes that promotes interactive exploration, fosters motivation in learning, promotes long-term student engagement, and helps students understand the link between certain actions and their effects on the environment.

1.4. The Scope of the Article

The scope of this article centers on the development and application of the NATURE project as a serious educational game designed to promote environmental education and sustainable natural resource management. This article explores how the game-based learning approach is used to address pressing environmental challenges, such as pollution, waste management, and urban sustainability. By immersing students in simulated real-world scenarios, the NATURE project is intended to foster critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration, aiming to equip students with the necessary skills to manage natural resources responsibly. This article emphasizes the importance of experiential learning through interactive games to enhance understanding of the environmental impact of human activities.

In addition to highlighting the game’s educational benefits, this article also examines the effectiveness of NATURE in different educational settings across several countries and underscores the role of the game in bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and its real-world application, demonstrating how it can be a valuable tool for fostering environmental awareness and encouraging sustainable practices in higher education and beyond.

2. Materials and Methods

The level of use of game-based learning in higher education is still quite low, although it has increased in recent years [25]. In fact, regarding environmental education, the materials found are mainly aimed at younger people (10–16 years-old) and address the following topics: waste collection [26,27]; recycling [28]; forest protection [29]; circular economy [30]; animal welfare and species protection; sustainability and biodiversity [31,32]. These tools have proven to be very useful in developing critical thinking and environmental awareness, but they are mainly used in a classroom context or disseminated in schools. Some of these resources as presented below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Digital game resources for environmental education.

This range of educational games promote environmental awareness and sustainable practices through interactive learning. They use scenarios that encourage players to reflect on the environmental impact of their decisions, such as in managing resources responsibly or reducing carbon emissions. By simulating real-world environmental challenges, these activities aim to raise awareness about issues like climate change, pollution, and the importance of sustainability in daily life.

Games like these often involve tasks like cleaning up polluted areas, managing natural resources, or making strategic decisions to minimize environmental damage. These activities are designed not only to educate but also to engage players in thinking critically about their role in environmental conservation. By placing players in virtual environments where their choices directly affect outcomes, these tools help illustrate the complex relationship between human actions and environmental health.

Through interactive gameplay, participants—especially younger audiences—can develop a deeper understanding of environmental issues and the importance of sustainable practices. These games serve as valuable educational tools that combine entertainment with learning, fostering a sense of responsibility and encouraging positive behavioral change towards the environment.

2.1. The NATURE Educational Game

The NATURE project (Available at: https://ctll.e-ce.uth.gr/index.php/nature/ accessed on 29 October 2024) included the design and development of the following:

- An active, game-based learning methodology for environmental education through exploration, collaboration, and experimentation.

- A digital serious game that challenges students to engage in scenarios related to responsible natural resource management inspired by real-life. The game should introduce clear learning objectives, interesting roles, and rich actions that students could undertake to design environmentally sustainable solutions. The game should provide real-time feedback on the consequences of their choices, thus developing awareness and knowledge on the effects of human activity to natural ecosystems.

- Educator support content in the form of learning activities, videos, and a reference guide that facilitates the integration of project outcomes into teaching practices.

The scope for intervention was guided by a preliminary survey to assess the status point in natural resource management awareness conducted in Italy, Latvia, Estonia, Portugal, Spain, and Greece. A total of 162 participants (higher education educators and students) provided their views on the needs of students on natural resource management and on the educator skills and gaps in the delivery of engaging environmental education activities. Participants determined that such a game should include references to water sustainability, ecosystems, minerals, biomass types, and biodiversity. The game should also develop several aspects of knowledge and skills related to natural resource management: sustainable use of natural resources, ethical and sustainable thinking, ecosystem health knowledge, environmental problems, basic science concepts related to resource use and management responsible environmental behavior, situation assessment skills, water management skills, biodiversity conservation knowledge, critical thinking skills, people–natural landscapes interaction knowledge, collaboration skills, land use and planning, analytical skills and creativity.

The major identified challenge was training teachers and creating a context in which they could develop themselves by becoming sustainable educators. Teachers showed a clearly pro-environmental attitude but also a greater distance from an excessively “naturalistic” view of the environment; hence, they essentially defended an ecocentric conception of nature conservation to the detriment of the anthropocentric one.

From the educators’ point of view, the game should also offer rich functionality in structuring educational activities that address the specific needs of a given environmental education class. Therefore, it should allow to accomplish the following:

- Clearly and precisely define learning objectives and student learning actions.

- Setup the environment of a scenario in a manner that supports learning objectives by precisely customizing the problem to meet certain educational needs. This could be achieved either by using existing material or by creating the layout of land formations, bodies of water, sources of minerals, habitats, residences and economic activity, industries, educational organizations, recreational areas, small businesses, malls, public services, and infrastructures.

- Monitor student progress.

- Expose students to different learning scenarios that should encourage them to think critically and entrepreneurially with respect to solutions that respect the environment.

The game should also promote digital practice in education as a high-quality, open educational software and increase the relevance of environmental higher education.

The created game (Figure 1) belongs to the city builder game genre. In it, users manage scenarios involving natural resource management inspired by real life. The game offers a very flexible environment for scenario planning, including a rich library of urban fabric composition objects, such as residential, industrial, small business, parks, industrial buildings, schools, cultural buildings, and others; objects related to the natural environment, such as trees, forests, flora and fauna species, and landscaping tools; and the creation of mounds, volumes of water, and other formations.

Figure 1.

Main menu of the NATURE game.

Using this library, faculty and other stakeholders can design rich scenarios that encourage students to achieve development goals alongside responsible environmental management goals. For example, students may be called upon to manage a city by building housing, running businesses and industry, and providing public services by addressing needs such as electricity supply and access to water, as well as quality of life goals such as education, health, and others. To develop the city, students must exploit available natural resources, such as trees, forests, or minerals, that must be managed responsibly; trees must be replanted, pollution must be addressed, biodiversity must be conserved.

2.2. Methods

The NATURE learning intervention was validated in practice through piloting activities with students in Latvia, Greece, Portugal, Spain, Estonia, and Italy. The main research questions that were addressed were the following:

- To what extent does the game-based learning environment increase student engagement and motivation in addressing environmental issues?

- In what ways does the game environment enhance students’ understanding of complex environmental concepts and their ability to apply theoretical knowledge in practical scenarios?

- How relevant is the game environment for teaching and learning about natural resource management among students?

The piloting sessions took place mostly during September and October of 2023 and involved more than 400 students and about 50 teachers. After the piloting activities, participants were asked to answer a questionnaire, and some of them were selected to contribute to a focus group discussion (one in each country). All study participants were competent adults. No personal or private information was kept. Answers were anonymous and could not be traced back to the individual.

Partners were free to select the learning scenarios that were used in each session, and they tended to use the ones they were more familiar with, namely, the ones created locally.

In Portugal, the chosen learning scenarios used were related to the city of Porto:

- Reviving Porto: Porto, a vibrant city in Portugal, historically thrived on its industrial activities. In recent years, the city has faced challenges due to its limited green spaces and increasing air pollution. The heavy reliance on industrial activities has resulted in a decline in urban green areas, adversely impacting the environment and quality of life. The European Union has allocated significant funds for urban redevelopment with a focus on increasing green spaces and reducing pollution, aiming to transform Porto into a model of sustainable urban living. Porto’s current state is unsustainable, marked by poor air quality and a lack of green spaces amidst a growing industrial backdrop. The challenge is to revitalize the city, balancing industrial growth with environmental health and community well-being.

- Porto’s Energy Revolution: Porto faces energy sustainability challenges, including high energy demand and reliance on non-renewable sources. This scenario explores transitioning Porto to sustainable energy use, balancing economic growth and environmental protection. Porto’s growing energy needs, driven by urban expansion, require innovative solutions for sustainable energy production, distribution, and consumption. The city aims to adopt renewable energy sources, improve energy efficiency, and integrate smart city technologies.

In Italy, two learning scenarios were prepared for the piloting phase related to waste crisis, environmental pollution, and natural resources management. Both scenarios presented similarities regarding the combination of three climates (temperate, boreal, and tropical) and the coastal geographical aspect. This was undertaken to let the students deal with the same difficulties during the piloting phase. And, of course, the learning scenarios provided had specific objectives generally aligned to the curriculum so they could be used in different courses. The students were engaged in several activities. First, they had to conduct in-depth research on the environmental crisis described in the scenario provided to assess its impact on a possible real-life situation through a plan to be implemented to solve the situation. The plan had to be presented to other colleagues or environmental experts. They used the game-based environment to simulate their resolution plan during this task. Most activities in the game-based environment were organized in face-to-face modality; thus, the instructors could immediately receive the students’ feedback and performances. The result of this combination was an increase in the student engagement level.

In Latvia, the local project team provided the teachers with brief online training and resources on how to use the NATURE game effectively during the piloting implementation. Consultations with the game developing partner were encouraged so that they might acquire hands-on information and support. Two learning scenarios were tested, focusing on issues such as the waste crisis, environmental pollution, natural resources management, and citizens’ overall well-being. These scenarios incorporated a combination of three climates, with the first scenario featuring temperate, boreal, and tropical climates, while the second included temperate, boreal, and dry climates. Both scenarios ensured ample water access. Throughout the pilot, students confronted various challenges, with each learning scenario presenting specific objectives that were generally aligned with the curriculum. The students actively participated in diverse activities, beginning with conducting thorough research on the environmental crisis outlined in the given scenario. Their objective was to evaluate the impact on a potential real-life situation and devise an implementation plan to address the issue. Subsequently, they presented their plans to their peers and lecturers. The game-based environment served as a simulation platform for executing and demonstrating their resolution plans during this task. Most of the in-game activities were conducted in face-to-face sessions, providing instructors with immediate access to student feedback and performance evaluations. This combination led to an increased level of student engagement.

In Greece, the scenarios were centered on the management of cities, inspired by real-life settings, where participants were tasked with improving their urban environments to meet the objectives of each scenario. The game challenged students to tackle complex urban issues such as waste management, pollution control, energy sustainability, and resource allocation. These city management scenarios aimed to reflect the real-world challenges faced by Greek municipalities, giving participants a realistic and relatable context in which to apply their knowledge. Throughout the scenarios, students were required to evaluate the current state of their assigned city, identify environmental issues, and propose innovative solutions to enhance urban sustainability. Each scenario had specific goals, such as reducing pollution levels, improving waste disposal systems, or ensuring a sustainable water supply, all of which aligned with local environmental priorities. Participants worked collaboratively to implement their plans within the game, simulating real-world decision-making processes while receiving feedback from their instructors.

In Estonia, the learning scenario was related to green and sustainable energy, quality of living, and managing pollution and revenue production. This learning scenario begins with a situation where the people are actively leaving their industrial home town because of poor living conditions and high pollution levels. The player is challenged to upgrade the city’s energy source from coal-based energy to a source that does not produce as much pollution in order to keep the citizens from leaving their city. However, one of the objectives requires the player to maintain the city’s ability to extract coal, which is symbolic of the self-sufficiency and production of the city. This puts the student face to face with a wicked problem—how to find a balance between economic success and social welfare.

In Spain, the approach followed a similar structure, with scenarios tailored to the local setup of Vigo. Students were tasked with improving the sustainability of the city and its surrounding areas, focusing on real-life environmental and urban challenges faced by the region. The scenarios addressed a range of issues, including waste management, air quality improvement, energy efficiency, and the protection of natural resources, all within the context of Vigo’s urban and coastal environment. Participants were encouraged to analyze the current environmental state of the city, identifying key areas for improvement and formulating strategies to enhance its sustainability. Each scenario had specific goals related to reducing pollution, optimizing energy usage, and promoting eco-friendly infrastructure development. Students were also asked to consider the impact of their decisions on both the urban population and the natural habitats surrounding the city, particularly Vigo’s coastal ecosystems, which are crucial to the region’s environmental health. Working in teams, students developed detailed action plans and implemented them within the NATURE game, simulating the real-world effects of their solutions on Vigo’s sustainability. The game’s interactive platform allowed them to experiment with different strategies, adjusting their approaches based on immediate feedback from their instructors and the game’s simulated outcomes. This hands-on experience not only helped students understand the complexity of managing an urban environment but also reinforced the importance of making decisions that balance human activity with ecological preservation.

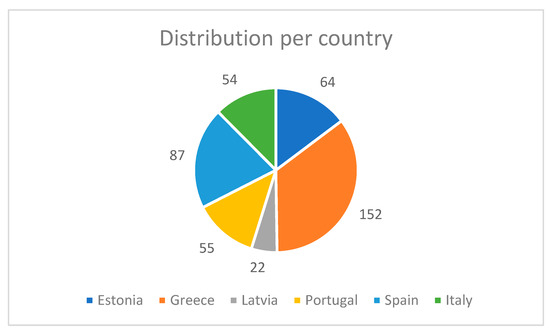

After the testing, 434 participants answered a questionnaire assessing the usability, playability, and effective educational value of the game. The distribution of participants per country was as follows (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Participant distribution per country.

There was a relatively even distribution of the participants in Portugal (55), Estonia (64), and Italy (54). However, there was a much larger number of participants from Greece (152) and Spain (87), and a limited participation in Latvia (22). Therefore, the results must be analyzed with care as there are differences in the cultural or educational context that might have influenced the results in each country

- Distribution per knowledge area

Concerning the knowledge area of the participants, the distribution is presented in Table 2 below. The most-represented domains were Engineering (47.7%) and Educational Sciences (21.2%), immediately followed by Business and Economics (15.4%). However, this distribution was not homogeneous across each country, which, again, might influence the final results (in grey in the table and the most-represented domains in each country). For Greece and Portugal, the predominant domain was Engineering; for Estonia, it was Information Technology; for Latvia, Arts and Culture; for Italy, Business and Economics; and for Spain, Educational Sciences.

Table 2.

Knowledge areas of participants per country.

3. Results

As mentioned above, the game was assessed in terms of its usability, playability, and effectiveness in learning and awareness raising.

- Usability and User Experience

The usability of the game was evaluated according to a standard tool assessing the following variables with a 7-point scale (from 0 to 6):

- Obstructive—supportive

- complicated—easy

- inefficient—efficient

- confusing—clear

- boring—exciting

- not interesting—interesting

- conventional—inventive

- usual—leading edge

The obtained results per country are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Usability results per country.

In each variable, the scale goes from the highly negative extreme (value of 0) to the highly positive extreme (value of 6), with an average of 3. The most positive evaluations (over 4.5) are presented in grey. The Greek and Italian participants were very positive about the game (in all the aspects). The Spanish participants were almost as positive but were not so thrilled about the easiness of the game. The Latvian and Portuguese participants were the least positive (but still positive in all the aspects). Overall, the most positive aspects were the efficiency and interest domains. But the game was also considered supportive, exciting, and inventive.

- Playability and User Engagement

The playability of the game and the engagement of the player were measured using the Game Experience Questionnaire (GEQ) using a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 to 4) using the following statements:

- I was interested in the game’s story;

- I felt successful;

- I felt bored;

- I found it impressive;

- I forgot everything around me;

- I felt frustrated;

- I found it tiresome;

- I felt irritable;

- I felt skillful;

- I felt completely absorbed;

- I felt content;

- I felt challenged;

- I had to put a lot of effort into it;

- I felt good.

The collected answers are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Playability and engagement results.

Again, the highly positive results (above 3 for positive statements and below 1 for negative statements) appear in grey. The most positive participants were the Italians, who considered the game quite engaging and playable. Greek and Estonian participants also had a very positive view of the game. In general, participants did not feel bored, frustrated, or tired; on the contrary, they felt good playing the game.

- Learning and Awareness Raising Effectiveness

Concerning the learning and pedagogical aspects, a specific tool was created using a 5-point Likert scale (1—totally disagree to 5—totally agree).

- I learnt something related to natural resources management;

- The game represents well real life situations;

- The game improved my soft-skills on responsible natural resources management;

- The game promotes interactive exploration;

- The game fosters motivation in learning;

- The game helped me to understand the link between actions and effects on the environment.

The obtained results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Learning and awareness raising effectiveness results.

Greek, Estonian, and Italian participants were very positive about the learning achieved using the game. In general, all aspects were quite positive. Only the acquired soft skills were considered to have been less successful.

- Qualitative comments

A set of open questions allowed participants to voice their opinions and suggestions in a qualitative format. The results (Table 6) were grouped by their frequency and scope. Players were particularly drawn to the game’s realistic simulation of environmental issues, the ability to make meaningful decisions that impact the environment, and the opportunity to explore real-life scenarios related to resource management. The game’s design, graphics, and the sense of accomplishment from strategic decision-making also received praise. However, some players noted areas for improvement, such as the need for clearer guidance and better optimization. Overall, the game was valued for its ability to engage users in learning about sustainability through an interactive and immersive experience.

Table 6.

Positive qualitative comments.

Players also suggested several improvements to enhance the game experience, focusing on tutorial enhancements, performance optimization, and user interface upgrades. They recommended adding detailed tutorials and guides to help players understand the UI, gameplay, and resource management better. Performance improvements, such as faster game speed and better optimization for various hardware, were also highlighted. Suggestions for user experience included a more intuitive interface, clearer indicators, and better accessibility options. Players also expressed a desire for richer game content, including more varied tasks, a more engaging storyline, and a wider range of scenarios. Additionally, they emphasized the need for improvements in resource management, the resolution of technical issues, and the inclusion of more educational content related to environmental sustainability. Some players also called for multiplayer features and community-driven content creation, alongside aesthetic and functional enhancements for a more streamlined and visually appealing experience. The full set of required improvements is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Requested improvements.

Players suggested a variety of potential scenarios to add to the game, emphasizing environmental, urban planning, and educational themes (Table 8). They proposed scenarios focused on managing natural disasters, conserving biodiversity, and addressing climate-specific challenges, such as desert or polar environments. Urban and rural planning scenarios were also popular, with ideas for high-density cities, agricultural settings, and transitioning industrial areas to clean energy. Educational scenarios were recommended to teach problem-solving and sustainable practices. Additionally, players expressed interest in historical settings, geographical diversity, and futuristic environments, including space colonization. Economic challenges, societal and cultural management, and scenarios that reflect real-world environmental issues were also highlighted. Adventure and exploration scenarios in extreme locations, as well as collaborative multiplayer options, were suggested to enhance gameplay diversity. Creative scenarios, including those with pop culture references or unique challenges like managing a ski resort, were also mentioned to engage a broader audience.

Table 8.

New potential scenarios.

In the end of each piloting setup, a focus group was organized with teachers and students randomly selected. According to an established protocol, participants discussed and reflected on the following aspects: Relevance, Acceptance, Quality, Value, and Effectiveness. The combined feedback from all the countries is summarized in Table 9 below.

Table 9.

Summary of the focus group results.

4. Discussion

The NATURE serious game emerges as an innovative educational tool, aiming to revolutionize the way environmental management is taught in academic settings. Developed to engage students in a meaningful exploration of sustainability and environmental stewardship, this game leverages the principles of serious gaming to deliver impactful educational experiences. Table 10 shows the main insights collected in comparison with other pedagogical approaches.

Table 10.

Main insights collected.

The pilot sessions were designed to evaluate the game’s utility as a pedagogical instrument meticulously, particularly focusing on its ability to immerse students—many of whom were novices in serious gaming—within an interactive, virtual environment that simulates pressing environmental challenges.

4.1. User Experience and Educational Impact

During the pilot sessions, the response from participants provided invaluable insights into the game’s educational impact. Students, while navigating the roles of city or project managers, engaged deeply with the game’s content, applying their knowledge to make decisions aimed at promoting environmental sustainability. This active engagement, facilitated by the game’s immersive and interactive setup, significantly bolstered students’ enthusiasm and motivation, allowing them to delve into environmental issues with greater curiosity and commitment.

Participants noted that the NATURE game was instrumental in facilitating a form of learning that was both engaging and effective, enhancing their ability to internalize complex environmental concepts. By providing a platform where theoretical knowledge could be applied in practical, scenario-based contexts, the game enabled students to better grasp the nuances of environmental management, witnessing firsthand the outcomes of their strategies and decisions.

4.2. Technical Performance and Usability

Despite the game’s strong educational potential, certain technical challenges were identified that could impede its effectiveness as a learning tool. Participants encountered issues related to the game’s responsiveness and overall technical performance, particularly when used on less capable devices or unreliable internet connections. These issues were found to distract from the learning experience, emphasizing the necessity for improved technical optimization and support.

The feedback also pointed to areas for enhancement in user interface design and overall usability. Ensuring that the game is accessible and user-friendly across a range of devices was highlighted as crucial for maintaining student engagement and facilitating a smooth, uninterrupted learning process.

4.3. Alignment with Curriculum and Learning Objectives

The feedback from educators and students alike underscored the game’s strong alignment potential with existing educational curricula. By integrating NATURE into classroom activities, educators can provide students with a more dynamic and applied learning experience, which is particularly effective in conveying the complexities of environmental management.

However, for the game to be truly effective, it must be seamlessly integrated into the educational framework, with clear connections to specific learning objectives and real-world applications. This integration requires educators to have a thorough understanding of the game mechanics and the ability to guide students in translating their virtual experiences into concrete learning outcomes.

4.4. Feedback Summary and Recommendations

Aggregating feedback from the pilot sessions yielded several actionable recommendations for enhancing the NATURE game:

- Addressing and resolving technical issues to ensure a stable and responsive gaming environment.

- Enriching the game’s educational content with a broader array of scenarios, each designed to highlight different aspects of environmental management.

- Improving the user interface and interaction design to make the game more intuitive and engaging.

In response to the feedback, the following recommendations were formulated:

- Optimize the game for varying levels of hardware performance, ensuring a consistent experience across different devices.

- Develop a comprehensive tutorial or introductory session to acquaint users with the game mechanics and objectives, facilitating a smoother entry into the game environment.

Moving forward, the development team plans to expand the scope of the NATURE game’s application, exploring its potential integration into a wider range of educational contexts. This expansion includes adapting the game for secondary education curricula and exploring its use in interdisciplinary settings, where it can contribute to a holistic understanding of sustainability and environmental management.

Additionally, future iterations of the game will consider user feedback for further enhancements, potentially incorporating features such as multiplayer collaboration, broader scenario diversity, and more nuanced feedback mechanisms to track and encourage student progress

5. Conclusions

This study offers valuable insights into the effectiveness of educational tools in fostering environmental awareness, highlighting the potential for significant positive impacts. The NATURE serious game exemplifies this potential by representing a significant advancement in environmental management education. It demonstrates how serious gaming can transform traditional learning paradigms through immersive simulation and interactive gameplay. NATURE effectively engages students, fostering a deep and meaningful connection to environmental stewardship and sustainability. The game’s seamless integration into educational curricula and its ability to enhance comprehension of complex environmental issues underscores its pedagogical value.

Feedback from the pilot sessions highlights the game’s success in motivating students and enhancing their learning experience. By allowing students to act as managers within the game, NATURE empowers them to make critical decisions, apply theoretical knowledge in practical contexts, and witness the consequences of their actions. This experiential learning approach not only bolsters engagement and retention but also cultivates essential skills in problem-solving, critical thinking, and strategic decision-making.

While this study acknowledges certain challenges, such as the relatively small sample size and our reliance on self-reported measures, these factors also provide opportunities for further exploration. The variations in perceived effectiveness across different demographics underscore the importance of tailoring educational interventions to diverse learning styles and backgrounds. This aligns with the broader feedback from NATURE’s pilot sessions, which indicate the necessity for continuous improvement, particularly in addressing technical challenges and enhancing usability.

By focusing on optimizing technical performance, expanding scenario diversity, and refining user interfaces, NATURE can maximize its educational impact, accommodating a broad range of learners and technological infrastructures. This study’s focus on short-term impacts serves as a foundation for future research to explore long-term retention of knowledge and behavioral changes. In this context, the NATURE game is poised to play a pivotal role in such future studies, offering a robust platform for assessing the sustained impact of environmental education.

Looking forward, NATURE’s broader integration into diverse educational settings, with a focus on adaptability and interdisciplinary application, represents a promising direction. By incorporating user feedback into ongoing development, the game can evolve to meet emerging educational needs, offering tailored experiences that resonate with students and educators alike.

In conclusion, NATURE stands out as a unique and valuable tool in environmental education, poised to make significant contributions to cultivating environmental awareness and responsibility among students. Its continued development and integration into educational frameworks heralds a new era of interactive learning, where engagement, innovation, and real-world application converge. This synergy equips students with the knowledge and skills necessary to navigate and address the environmental challenges of the future, building on the solid foundation laid by current educational tools and studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.; methodology, H.T. and C.V.d.C.; software, O.H.; validation, G.S., M.T., A.M.D., T.J., J.T., H.T., M.C.-R. and C.V.d.C.; formal analysis, C.V.d.C.; investigation, G.S., M.T., A.M.D., T.J., J.T., H.T., M.C.-R. and C.V.d.C.; resources, G.S.; data curation, C.V.d.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V.d.C.; writing—review and editing, J.T., M.C.-R. and A.M.D.; supervision, C.V.d.C.; project administration, G.S.; funding acquisition, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Commission through the Erasmus+ programme, grant number: 2021-1-LV01-KA220-HED-000032033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated by this study are publicly available via request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, 2050 Long-Term Strategy. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2050-long-term-strategy_en (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Pineiro-Villaverde, G.; García-Álvarez, M. Sustainable Consumption and Production: Exploring the Links with Resources Productivity in the EU-28. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchieta, R.B. Educação Ambiental Através do Lúdico para o Público Infantil. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development for 2030 Toolbox. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/education/toolbox (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Angélico, M.J.; Rocha, A. Tecnologias de Informação (TI) na Educação. RISTI Rev. Ibérica De Sist. E Tecnol. Da Informação 2015, 16, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Alenezi, M. Digital Learning and Digital Institution in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, E.; Familyarskaya, L. Use of Digital Technologies in the Educational Environment of Higher Education. Open Educational E-Environment of Modern University. In Proceedings of the International Conference on New Pedagogical Approaches in STEAM Education, Kyiv, Ukraine, 26–27 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caeiro-Rodriguez, M.; Manso-Vazquez, M.; Mikic-Fonte, F.A.; Llamas-Nistal, M.; Fernandez-Iglesias, M.J.; Tsalapatas, H.; Heidmann, O.; De Carvalho, C.V.; Jesmin, T.; Terasmaa, J.; et al. Teaching Soft Skills in Engineering Education: An European Perspective. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 29222–29242. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, F.; Maia, N.; Cavalcante, C.; Rodrigues, M.; Cabral, J.; Ferreira, V. Promoção da educação ambiental através de jogos didáticos. In INNODOCT/14: Strategies for Education in a New Context; Editorial Universidad Politécnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 861–870. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; Manso, A.; Patrício, J. Design of a Mobile Augmented Reality Platform with Game-Based Learning Purposes. Information 2020, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videnovik, M.; Trajkovik, V.; Kiønig, L.; Vold, T. Increasing quality of learning experience using augmented reality educational games. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 23861–23885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz de Carvalho, C.; Durão, R.; Llamas-Nistal, M.; Rodriguez, C.M.; Heidmann, O.; Tsalapatas, H. Desenvolvimento de Competências Profissionais no Ensino Superior através de Aprendizagem Ativa e Jogos Sérios: O Caso Português. In Proceedings of the 14th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Coimbra, Portugal, 19–22 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, A.; Vaz de Carvalho, C. Game-Based Learning, Gamification in Education and Serious Games. Computers 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairi, I.; Dhiab, M.; Mzoughi, K.; Mrad, I.; Abdessalem, I.; Kraiem, S. Serious Game Design with medical students as a Learning Activity for Developing the 4Cs Skills: Communication, Collaboration, Creativity and Critical Thinking: A qualitative research. La Tunis. Médicale 2021, 99, 714–720. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeja, I.; Bushati, J. Gamification and serious games methodologies in education. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Symposium GRID 2022, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 3–5 November 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.A.; Araújo, I.; Fonseca, A. Das Preferências de Jogo à Criação do Mobile Game Konnecting: Um estudo no ensino superior. RISTI Rev. Ibérica De Sist. E Tecnol. Da Informação 2015, 16, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Novo, C.; Zanchetta, C.; Goldmann, E.; Vaz de Carvalho, C. The Use of Gamification and Web-Based Apps for Sustainability Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Ho, M.; Pham, T.; Nguyen, M.; Nguyen, K.; Vuong, T.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, T.; Khuc, Q.; et al. How Digital Natives Learn and Thrive in the Digital Age: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, N.; Ford, W.; Manzo, C. Engaging Digital Natives through Social Learning. J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2017, 15, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, X.Y.; Aas, E.; Medgard, M. Teachers’ use of digital learning tool for teaching in higher education: Exploring teaching practice and sharing culture. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 11, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.L. Dificuldades e Desafios na Integração das Tecnologias Digitais na Formação de Professores—Estudos de Caso em Portugal. Rev. Contrapontos 2018, 19, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A. A Utilização de Jogos Digitais, como Estratégia de Motivação no Ensino das Ciências Naturais (Project Report); Escola Superior de Educação e Ciências Sociais, Politécnico de Leiria: Leiria, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzálvez, E.; Kikot, T.; Fernandes, S.; Costa, G. Potencial da aprendizagem baseada-em-jogos: Um caso de estudo na Universidade do Algarve. RISTI Rev. Ibérica De Sist. E Tecnol. Da Informação 2015, 16, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckert, A.; Bogner, F. Cognitive learning about waste management: How relevance and interest influence long-term knowledge. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.K.; Vidal, D.G.; Dinis, M.A.P. Raising Awareness on Solid Waste Management through Formal Education for Sustainability: A Developing Countries Evidence Review. Recycling 2021, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhonto, B.; Mnguni, L. The Impact of a Rural School-Based Solid Waste Management Project on Learners’ Perceptions, Attitudes and Understanding of Recycling. Recycling 2021, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiplady, L.S.; Menter, H. Forest School for wellbeing: An environment in which young people can ‘take what they need’. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2021, 21, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiippana-Usvasalo, M.; Pajunen, N.; Maria, H. The role of education in promoting circular economy. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2023, 16, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, J.; Reinders, H. Sustainable learning and education: A curriculum for the future. Int. Rev. Educ. 2020, 66, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herodotou, C.; Ismail, N.; IBenavides Lahnstein, A.; Aristeidou, M.; Young, A.N.; Johnson, R.F.; Higgins, L.M.; Ghadiri Khanaposhtani, M.; Robinson, L.D.; Ballard, H.L. Young people in iNaturalist: A blended learning framework for biodiversity monitoring. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2024, 14, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).