1. Introduction

The terms trafficking in persons and human trafficking (HT) are often used interchangeably as umbrella terms to describe criminal activities where traffickers abuse and profit from adults or children [

1]. Trafficking involves taking control and ownership of individuals, treating them as property. Those who participate, directly or indirectly, aim to exploit others for their own gain, whether through forced labor, the sexual exploitation of adults or children, the removal of organs, and domestic servitude [

2,

3].

In the United States, two main forms of trafficking are recognized: forced labor and sex trafficking. Forced labor involves exploiting someone’s services through force, fraud, or coercion. Domestic servitude is a type of forced labor where victims work in private residences, often in isolation. Forced child labor refers to schemes where traffickers compel children to work due to their vulnerability. Sex trafficking involves using force, fraud, or coercion to compel individuals into commercial sex acts, including exploiting children. Despite legal prohibitions and widespread condemnation, forms of slavery persist, such as the sale of children, forced child labor, and debt bondage [

1].

Human trafficking is a pervasive and lucrative criminal activity worldwide. Based on some reports, human trafficking ranks as the third-largest criminal activity globally, following drug trafficking and counterfeiting [

4]. Given the minimal expenses and substantial profits at stake, traffickers have a compelling motivation to persist in this abhorrent criminal activity [

5].

Human trafficking generates an estimated annual global profit of

$150 billion, victimizing around 25 million people worldwide [

6]. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, a child is trafficked for sexual exploitation in the United States every two minutes [

7].

Sexual exploitation is the most prevalent form of human trafficking, accounting for 79% of cases. The majority of victims of sexual exploitation are women and girls. Notably, in 30% of the countries that provided data on the gender of traffickers, women and girls constituted the largest group of traffickers. In certain regions, it is common for women to traffic other women [

8]. The second most prevalent form of human trafficking is forced labor, representing 18% of cases, though this figure may be underestimated due to underreporting compared to trafficking for sexual exploitation. Globally, nearly 20% of all trafficking victims are children; however, in some areas of Africa and the Mekong region, children constitute the majority of victims, reaching up to 100% in parts of West Africa [

8].

The global approach to combating human trafficking revolves around the “3P” paradigm—prosecution, protection, and prevention. This framework is endorsed by the United States, as evident in international agreements such as the Palermo Protocol and domestic legislation such as the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000. The U.S. Department of State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (TIP Office) employs diplomatic and programmatic measures to promote the 3P paradigm worldwide. Additionally, a fourth “P” for partnership is recognized as a supplementary strategy to mobilize all segments of society in the fight against modern slavery [

9].

Given its humanitarian implications, it is crucial to raise awareness and educate the public about human trafficking, not only to bridge the knowledge gap but, more importantly, to enhance the identification of victims and hold perpetrators accountable. Moreover, increased awareness can empower individuals to identify and report potential cases of human trafficking [

5]. More importantly, it can lead to the early detection and education of potential victims, which can help them make informed decisions that can prevent them from being trafficked [

10,

11].

In particular, educational serious games hold prospects in tackling the scourge and prevalence of human trafficking, offering engaging tools that can raise widespread awareness and empower individuals. A serious game refers to a digital game designed to entertain while also accomplishing at least one additional objective, such as learning or health promotion. Although some equate serious games with educational games, digital games can serve “serious” purposes beyond learning. They can motivate individuals to exercise, be employed in medical treatment, or function as a marketing tool [

12].

Serious games have become a promising educational method in diverse fields. For example, according to research conducted by Sharifzadeh et al. [

13], serious games are increasingly used for health education. D’Errico et al. [

14] investigate how playing a serious game impacts adolescents’ perception of risks in home, school, and work environments. Results showed that playing the game increased engagement, the internal locus of control, risk perception, and protective behavioral intentions. Engagement and internal locus of control also acted as predictors for the other outcomes, highlighting the game’s role in promoting safety and health awareness.

In the cybersecurity domain, most developed games focus on education, training, and raising awareness to enhance knowledge about cybersecurity [

15]. For example, Phishy is an online serious game designed to train enterprise users in phishing awareness. It was shown that the Phishy game significantly enhances players’ ability to identify phishing links while also providing an enjoyable gaming experience [

16]. Gounaridou and colleagues present the development of a traffic safety educational game in which players follow road rules as pedestrians or drivers. The study demonstrates that well-designed educational games can enhance engagement, improve traffic awareness, and foster social responsibility through experiential learning [

17]. Additionally, serious games have been successfully applied in various educational fields, including science [

18], circular economy [

19], management [

20], programming [

21], cultural heritage [

22], cognitive skill development [

23], nursing education [

24], etc.

In certain domains, more effort is needed to apply serious games to supplement traditional educational methods. For instance, while numerous apps assert to offer information on preventing child sexual abuse (CSA), the majority fall short on incorporating key features such as game-based learning or serious games for teaching children, involving parents in the education process, and providing age- and gender-specific education. The most effective methods for teaching children about sexual abuse prevention involve game-based approaches like gamification, game-based learning, and serious games [

25].

Utilizing online games as a tool to raise awareness is an innovative approach. This method proves beneficial in educating individuals, particularly children and teenagers, about the intricacies of human trafficking in an interactive way. Through engaging in interactive games, users can familiarize themselves with various aspects and stages of human trafficking, ranging from recruitment, exploitation, and escape from trafficking rings to recovery, social reintegration, and the challenges faced in exercising the rights of trafficking victims. Employing video games becomes especially impactful when educating a younger audience about the realities of human trafficking [

5].

In this research, to bridge the gap in the extant literature, we thoroughly investigated and evaluated existing serious games related to human trafficking to illuminate the current state of the art, identify gaps, and suggest future research directions. Specifically, we conducted an investigation into academic publications, gray literature, and commercial games related to human trafficking. Additionally, a comprehensive review of evaluation criteria and heuristics for assessing serious games was undertaken. After reviewing and incorporating evaluation metrics and heuristics, the games underwent evaluation by both players and experts. Following both qualitative and quantitative analyses, the results are discussed, and their implications are presented.

The research questions addressed in this paper are as follows:

RQ1: What is the current state of publications on serious games relating to human trafficking?

RQ2: How can existing human trafficking games be evaluated?

RQ3: What are the outcomes and insights derived from the evaluation of serious games addressing human trafficking?

RQ4: What are the gaps in the current serious game landscape related to human trafficking?

RQ5: What future research directions should be explored to advance the field of serious games in the context of human trafficking?

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews and discusses academic publications related to human trafficking and serious games that address this issue. Additionally, this section provides a comprehensive exploration of serious game evaluation criteria and heuristics.

Section 3 details the proposed game evaluation method, including the selection of human trafficking-related serious games, the determination of evaluation criteria, and the subsequent evaluation, examination, and analysis.

Section 4 presents and discusses the results of both player-based and expert-based evaluations. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the findings and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Human Trafficking

Smith and colleagues [

26] examine the scope of human trafficking, its negative impact on global society, and the relationship between human trafficking and corruption. The authors estimate that there are between 12 million and 30 million slaves worldwide, with approximately 50% of trafficking victims being children and 70–80% being female. Their findings imply that human trafficking is a global problem that generates an estimated

$32 billion in revenue annually, making it one of the most profitable crime industries in the world. The authors find a significant positive correlation between corruption and human trafficking, suggesting that countries with higher levels of corruption are more likely to experience higher levels of human trafficking. This study concludes that ending human trafficking requires changing people’s attitudes and actions, as well as reducing corruption and increasing awareness of the issue.

The study by Khan et al. [

27] reviews human trafficking prevalence in Asian countries, encompassing forced labor, forced marriage, and sex trafficking affecting men, women, and children. Analyzing 64 studies from 2015 to 2022, the authors identify key contributing factors such as poverty, unemployment, political instability, corruption, and natural disasters. The review indicates an estimated 40.3 million trafficking victims in Asia as of 2016, with 30% from South Asia, East Asia, and the Pacific. The authors emphasize the need for effective strategies and comprehensive legislation to address underlying causes. Recommendations include enhancing law enforcement, increasing public awareness, and improving socio-economic conditions to reduce trafficking risks.

Olisah et al. [

28] present a thorough examination of human trafficking trends worldwide over a 20-year period. The study utilizes a robust dataset from the Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC) and employs time-series analysis, predictive modeling, and data visualization techniques to identify patterns and trends in human trafficking. The research reveals a complex global landscape of human trafficking, with varying trends and patterns across different regions. The study identifies Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe as significant regions for human trafficking, with distinct patterns of exploitation and demographic vulnerabilities. The study emphasizes the need for targeted anti-trafficking efforts, cooperation among nations, and continuous research to combat human trafficking effectively.

The study conducted by Martin and her colleagues [

29] shows that human trafficking is a significant problem in the United States, with demographic factors such as population, corruption, and religiosity playing a role in the prevalence of trafficking. The authors suggest that anti-trafficking efforts should focus on areas with high populations and high levels of corruption, and that education and awareness-raising efforts may be effective in reducing trafficking.

Albanese et al. [

30] analyzed 27 studies involving interviews with over 3500 victims and offenders from 22 countries, highlighting the nuances of consent, coercion, and fraud in these relationships. They found that many adult victims consent to exploitative arrangements due to desperate situations, such as financial instability or family pressures. However, this consent is often tainted by coercion, manipulation, or deception. Moreover, coercion can be implicit, involving pressure, threats, or debt, rather than explicit physical force. Victims may be coerced by perpetrators, but also by circumstances, such as a lack of access to education, employment, or social services. This study shows that fraud is a common tactic used by traffickers to recruit and exploit victims. This can involve false promises of employment, education, or a better life, as well as the manipulation of victims’ financial insecurity. The authors identify larger structural and social factors that contribute to human trafficking, including economic insecurity, housing insecurity, education gaps, and migration.

The paper by Saner et al. [

31] discusses the challenges of measuring and monitoring human trafficking within the context of the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It highlights the difficulties in collecting data on an invisible crime like human trafficking, which is often intertwined with issues like poverty, injustice, and weak institutions. The paper concludes that human trafficking, as an under-monitored issue, requires urgent attention and innovative solutions to improve data collection and policy responses. The authors recommend increasing awareness and citizen engagement in identifying trafficking.

Li et al. [

32] propose a natural language processing method to identify potential human trafficking in massage business reviews. The authors created a keyword lexicon for human trafficking, building two classification models alongside BERT and Doc2Vec embeddings. Using a labeled dataset of Yelp reviews, they applied preprocessing techniques such as contractions, spelling corrections, and stop word removal. The models aim to automate the review screening process, reducing manual efforts by law enforcement. The study demonstrates the potential of natural language processing techniques in detecting human trafficking.

The current approach to addressing human trafficking, which focuses on due diligence and reporting, is insufficient, and a more holistic approach is needed. The limitations of the current due diligence approach include its focus on first-tier suppliers and its failure to address the root causes of human trafficking. A social connection and political responsibility model have been proposed, which emphasizes the need for businesses to take responsibility for their role in perpetuating human trafficking. Businesses have a responsibility to go beyond due diligence and to take affirmative action to prevent human trafficking in their supply chains [

2].

Hodkinson et al. [

33] argue that the UK government’s efforts to combat modern slavery are flawed and counterproductive due to its hostile environment and policies toward migrants. The authors contend that the Modern Slavery Act 2015 focuses too narrowly on the immediate act of coercion between the victim and the perpetrator, ignoring the broader structural factors that contribute to migrant vulnerability and exploitation. They argue that the UK’s hostile environment policies, which aim to deter irregular migration, actually create conditions that facilitate forced labor and exploitation. The UK government’s hostile environment policies are incompatible with its efforts to combat modern slavery, and a more comprehensive approach is needed to address the root causes of migrant vulnerability and exploitation. A range of policy interventions have been proposed, including the provision of safe and legal migration routes, the restoration of rights and protections for asylum seekers, and the strengthening of labor market regulations to prevent exploitation [

33].

The study by Chamber and colleagues [

34] discusses the importance of trauma-informed care for survivors of human trafficking, who often experience complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and trauma-coerced attachment (TCA). The authors, who are healthcare providers, share their experience and observations from working with survivors of human trafficking at a medical safe haven (MSH). The study concludes that trauma-informed care is essential for survivors of human trafficking, and that a comprehensive approach that addresses physical, psychological, and psychosocial healthcare needs is necessary.

2.2. Serious Games on Human Trafficking

In this study, a comprehensive selection of academic databases was employed as primary sources to identify publications on serious games related to human trafficking. These databases included Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, Springer, Elsevier, Wiley, and PubMed. Additionally, we considered publications that cited the extracted records. The searches were conducted using targeted search terms pertinent to the title, keywords, and abstract sections.

The inclusion criteria for this review required that research be published in English and retrieved through the established search query. In cases where multiple papers reported the same study, only the most recent versions were considered, including theses, derived papers, and extended journal articles. Conversely, the exclusion criteria eliminated studies unrelated to the research questions, articles not written in English, and non-peer-reviewed sources such as opinion pieces and non-scholarly articles to uphold the research’s reliability and credibility. The search query was as follows:

((Human Traffick* OR Traffick* in persons OR Modern Slavery OR Sexual exploit* OR Enslave* OR Debt bond* OR Forced labor OR Domestic servitude OR Organ traffick* OR Child exploit* OR Child soldier* OR Sex traffick* OR Forced prostitut* OR Forced marriage OR Forced Begg* OR Forced Criminal) AND (Serious game* OR Video game* OR Digital game* OR VR OR Virtual Reality OR Augmented Reality OR Simulation OR Educational game* OR Game-based learning OR Mobile game* OR Interactive game*))

A number of researchers have carried out some important work on serious games focused on addressing human trafficking.

Toftedahl et al. [

35] delve into the design and reception of a serious game called Missing, available on Google Play, with the goal of raising awareness about trafficking and its societal impact. The focus is on analyzing player metrics and Google Play app store data to understand player reception, emphasizing three key contributions: highlighting the tension between a designer’s intention and game mechanics in conveying the message, addressing the complexity of finding relevant reviews for the serious theme, and examining the tension between star ratings and review content. A noteworthy finding is that even negative reviews can contribute positively to fulfilling the game’s intended purpose. A review analysis on Google Play indicates overall appreciation for the storyline, but challenges arise in finding game mechanics that comprehensively align with all narrative aspects. Players, in particular, face difficulties related to progression and encounter bugs that impact the game mechanics [

35].

O’Brien and Berents [

36] explore three online games released in the past five years aimed at increasing awareness about human trafficking. The analysis highlights the prevalence of persistent tropes portraying ideal victims without agency, emphasizing individualized issues over structural causes. Despite this trend, the diverse approaches employed by the games showcase the potential for nuanced storytelling and complexity within the realm of digital games.

The Cybersecurity Institute has embraced the challenge of developing an immersive anti-trafficking training program that goes beyond mere awareness education [

37]. It is designed to assess the specific skillsets of law enforcement and first responders. This comprehensive program aims to integrate all aspects of “serious gaming” within the framework of law enforcement and humanitarian communication. Given the dynamic nature of trafficking, the program, known as ATVRIT, will adapt and incorporate new insights into trafficking tactics and typologies as they emerge from law enforcement, academia, and victims’ services organizations. Future iterations of ATVRIT will continually enhance the simulation environment to accurately mirror the evolving nature of trafficking situations. The programmers of ATVRIT recognize the increasing demand not only for effective and precise training but also for the inclusion of reflexive, harm-reducing techniques, addressing implicit biases and stereotypes in programming [

37].

The first three studies reviewed serious games focused on human trafficking, while the subsequent two studies involved the development of a serious game related to this issue.

Koney and colleagues [

38] focus on the application of art therapy to manage trauma in children rescued from trafficking at the Volta Lake at the Touch-a-Life-Care-Centre in Ghana. The objectives include exploring existing therapies at the center, examining current intervention methods, and testing the efficacy of a game-based intervention for trauma management in children. Using a case study approach with questionnaires, observations, and interviews, the study designed a game intervention using Scratch software. Results indicate that the game-based intervention in art therapy positively impacts traumatized children, enhancing their concentration and sustaining their interest in art classes. Children at the Touch-a-Life-Care-Centre welcomed the new intervention. The study recommends incorporating the Game Intervention in Art Therapy into the school curriculum and advocates for the recruitment of art therapy specialists in public health facilities to enhance effective interventions and improve the well-being of children in clinical art therapy sessions.

A game designed to simulate the challenges faced in real-life escape and rescue operations was introduced by Sanchawala et al. [

39]. Drawing on established principles from educational literature, the authors aim to create a transformative experience that enables players to comprehend the obstacles that victims encounter and to gain insight into their mindset and thought processes. Their evaluation focuses on the game’s effectiveness in educating players about socio-economic situations, cultural predicaments, and latent conditions influencing human trafficking. To assess learning, they employ a two-phase survey process, consisting of a pre-test gauging players’ knowledge about the current state of human trafficking and a post-test where players rate the game’s experience, gameplay, and educational effectiveness regarding the trafficking scenario. Social activists engaged in rescuing trafficked individuals tested and validated the game, recognizing its potential impact on raising awareness.

In response to RQ1, we summarize the review of publications on serious games in the field of human trafficking in

Table 1.

In response to RQ1, the current serious games addressing human trafficking that we found in academic literature do not mention any game development process/framework information to explain how the games are developed. User-centered design for the development of serious games focused on human trafficking has not been applied [

40,

41]. Moreover, the reviewed games have not been thoroughly evaluated. The game presented by Borrelli and Greer [

37] has not been evaluated. Serious games need to be evaluated based on both their serious and game components [

42]. Only both parts of the Unlocked game [

39] have been evaluated; however, the authors have not applied any statistical tests, standard usability metrics, or serious game evaluation heuristics. Koney et al. [

38] only evaluated the emotions of the players, and again, the results have not been statistically tested. The human trafficking information provided by the current educational games is very limited. For example, Unlocked [

39] only provides limited information about factors possibly hindering a victim’s escape and how serious the situation of human trafficking is in India. Missing [

35], ACT, BAN, and (UN)TRAFFICKED [

36] have not been presented in academic research papers by their developers. We evaluate these commercial/non-academic serious games about human trafficking in this paper. We identified only five publications related to human trafficking games, of which two studies involved the development of a game, and the total number of citations is 17. This suggests a scarcity of academic research in the field.

2.3. Serious Game Evaluation

In this section, we review studies related to the evaluation of serious games. These studies are categorized into three main types: player-based evaluations, expert-based evaluations, and studies focusing on various evaluation methodologies, frameworks, and models. Each category is further explored in the following subsections.

2.3.1. Player-Based Evaluation Studies

Calderón and Ruiz provide a comprehensive summary of the current state of assessing serious games, drawing from a systematic literature review. The review identifies key assessment methods, application domains, game categories, features considered for educational effectiveness, assessment procedures, and participant population sizes. The research highlights that questionnaires and interviews are the predominant techniques for evaluating serious games. The primary quality characteristics assessed include game design, user satisfaction, usability, usefulness, understandability, motivation, performance, playability, pedagogical aspects, and user experience, among others [

43].

Fu et al. introduce a comprehensive scale for evaluating user enjoyment in e-learning games, encompassing eight dimensions: immersion, social interaction, challenge, goal clarity, feedback, concentration, control, and knowledge improvement [

44]. To validate the scale, four learning games from the university’s online course “Introduction to Software Application” were employed as instruments. Survey questionnaires were distributed to course participants, resulting in 166 valid samples. The outcomes indicated satisfactory validity and reliability for the proposed scale, named EGameFlow.

While many researchers acknowledge serious games as effective tools for teaching and learning, the literature lacks cohesion and/or consensus concerning the factors that influence users’ experiences and perspectives. Fokides et al. introduce a tool designed to assess a game’s effectiveness while concurrently comparing user viewpoints [

45]. The report details the creation and validation of a scale initially comprising seventy-two items distributed across thirteen factors. A total of 542 university students engaged in two serious games, with the administered questionnaire capturing their responses. The exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis determined that twelve factors and fifty-three items should be retained in the final scale.

Moizer et al. [

46] aim to articulate and evaluate an approach to assess user experience within the framework of a dedicated serious game designed to meet the training requirements of individuals in social enterprises. Their paper details the creation of a survey instrument, rooted in an extensive literature review, to capture the multi-dimensional aspects of user experience. The evaluation process is elucidated, and findings from surveys conducted among individuals in social enterprises are analyzed and discussed. The outcomes underscore the effectiveness of the proposed method for evaluating user experience [

46].

2.3.2. Expert-Based (Heuristic) Evaluation Studies

Heuristic evaluation stands out as the preferred method for assessing usability in games, especially when conducted by experts. Moreover, heuristics serve as design guidelines that are valuable tools for both designers and usability professionals.

The heuristic evaluation for playability (HEP) is an exhaustive set of heuristics designed for assessing playability [

47]. These heuristics draw inspiration from the literature on productivity and playtesting, specifically tailored for the evaluation of video games, computer games, and board games. To gauge their face validity and effectiveness in comparison to traditional user testing methodologies, these heuristics were applied to an evolving game design. The findings indicate that HEP successfully identified qualitative similarities and differences when compared to user testing. Moreover, HEP proved most effective for evaluating general issues during the early phases of development, particularly with prototypes or mock-ups. When combined with user studies, HEP introduces a novel method for the HCI game community, contributing to the creation of more usable and playable games.

To render HEP heuristics applicable across various game genres and delivery methods, another study concentrates on a refined set known as the heuristics of playability (PLAY) [

48]. Designed for early implementation in game development and to assist developers in the interim between formal usability/playability research phases, these heuristics were derived from effective scores on metacritic.com, a popular game review website. Fifty-four gamers assessed high- and low-ranked games against 116 potential heuristics. The study explores the implications of these heuristics in enhancing game quality, emphasizing their utility in design evaluation and self-report survey formats.

GAP is another set of principles focused on first-time players, tutorial use, and initial game play [

49]. Results showed that heuristics are more effective than “unassisted intuition” not only in identifying problems but also in inspiring recommendations for enhancements to the games’ player experience [

49].

A book chapter outlines an approach to evaluate user experience in video games using heuristics [

50]. The authors provide a concise overview of video games, introduce the concept of user-centered design for games, and delve into the history of heuristics for video games and the broader role of user experience in gaming. They propose a refined framework comprising two sets of heuristics (gameplay/game story, virtual interface) aimed at identifying critical issues in games. To assess its effectiveness in measuring user experience factors, they compare expert evaluations of six current games with user experience-based ratings from various game reviews. The findings suggest a correlation between the satisfaction of their framework and the average rating of the game.

The dual purpose of serious games, involving the simultaneous attainment of intended educational effects (the serious aspect) and entertainment value (the game aspect), is insufficiently addressed in existing studies on serious game evaluation. Caserman et al. sought to outline essential quality criteria for serious games [

42]. The primary objective of this research is to identify crucial factors in serious games and to align existing principles and requirements from game-related literature to enhance the effectiveness and appeal of serious games. In addition to a literature review, workshop results are also incorporated. The authors propose quality criteria for both the serious and game aspects, with particular attention to maintaining a balanced integration between them.

The primary objective of the research conducted by Jerzak and Rebelo [

51] was to delineate the essence of serious games and the evaluation process. The authors leveraged existing heuristics for games, along with their inherent weaknesses and strengths. They consolidated and presented the most crucial heuristic elements for games, forming three sets of heuristic evaluations to pinpoint areas of convergence.

In another research, authors have synthesized diverse heuristics into a succinct framework for gaming enjoyment, organized around the concept of flow [

52]. Flow, a widely acknowledged enjoyment model, comprises eight elements that encapsulate various heuristics found in the literature. The proposed model, GameFlow, delineates eight elements: concentration, challenge, skills, control, clear goals, feedback, immersion, and social interaction. Each element is accompanied by a set of criteria for attaining enjoyment in games. To initiate the exploration and validation of the GameFlow model, expert reviews were conducted on two real-time strategy games—one highly rated and one poorly rated—using the GameFlow criteria. This process yielded a more profound comprehension of enjoyment in real-time strategy games, shedding light on the strengths and weaknesses of the GameFlow model as an evaluation tool.

Existing evaluation methods for games are inadequate in assessing serious games due to a lack of understanding and a failure to encompass the seriousness of the content [

53]. As a response to this gap, Jerzak and Rebelo introduced the Heuristic Evaluation for Serious Games (HESG), which comprises three modules: Game Play, Entertainment and Usability, and Game Mechanics. Each module is designed for remote and autonomous use, allowing for flexibility to accommodate the specific requirements of designers and evaluators. The primary objective of the HESG is to establish a comprehensive and easily applicable tool for evaluating various types of serious games. The HESG has demonstrated its effectiveness as a versatile and accessible method, serving as a valuable tool for evaluating serious games designed for specific training purposes [

53].

While numerous heuristic guidelines tailored to the specifics of games have been introduced, they often concentrate on particular subsets of games or platforms. In response to this limitation, Yanez-Gomez et al. [

54] proposed a modular approach that involves classifying existing game heuristics using metadata. They also introduce a tool called MUSE (Meta-heUristics uSability Evaluation tool) for games. This tool enables the reconstruction of heuristic guidelines based on metadata selection, catering to the unique requirements of each evaluation case.

2.3.3. Evaluation Methodologies/Frameworks Studies

A literature gap in game-based learning (GBL) evaluation, arising from the inconsistent use of elements, is addressed in a study [

55]. By establishing terminology and scope across four conceptual levels, the study systematically categorizes GBL evaluation elements based on scope, definition, and usage. Utilizing directed content analysis of GBL evaluation literature from a prior systematic review, the research dimensionalizes GBL and breaks it down into factors/sub-factors according to theoretical constructs. This results in a structured and clear pattern for educational game evaluation. The further codification of metrics and mapping of relationships among GBL dimensions contribute to a conceptual framework offering enhanced insights into the learning process with educational games, guiding focus areas and evaluation criteria.

Abdellatif and colleagues [

56] divided the identified quality characteristics of serious games into primary and secondary categories based on their utilization in existing literature. A framework was then proposed to assess various dimensions of serious games by selecting and combining relevant quality characteristics. A programming serious game, Robocode, was chosen as a case study. In this study, the framework was applied as fifteen students at Queen’s University Belfast played the game and evaluated different quality characteristics according to the proposed framework. The results indicated an overall positive evaluation of Robocode; however, the framework suggested certain changes to enhance the game’s understandability, making it more accessible for users to play without the need for supervision or tutors.

Martinez et al. introduced the Gaming Educational Balanced (GEB) Model, addressing limitations in serious game evaluation [

56]. Built upon the Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics Framework and the Four Pillars of Educational Games Theory, the GEB Model offers a metric for assessing serious games and guiding their development. Tested with three indie serious games focused on mental health awareness, the evaluation highlighted that while gameplay was commendable, the integration of educational content was lacking. Statistical and machine learning validation of the GEB metric was performed, confirming its clarity and players’ ability to evaluate it accurately.

Employing suitable mechanisms for gameplay experience (GX) evaluation and measurement facilitates the validation of positive gameplay experiences. Nacke and colleagues introduced an approach to formalize evaluative methods and outline a roadmap for implementing these mechanisms in the realm of serious games [

57]. The authors advocate for a three-layer framework for GX, each layer accompanied by a range of measurement methodologies. They highlight the potential application of this framework in the domains of game-based learning and serious gaming, particularly in sports and health contexts.

Usability testing, though frequently overlooked in serious game development, holds significant importance, as issues in usability can significantly impact user experience and, consequently, the learning outcomes of serious games. Olsen et al. [

58] offered serious game developers a streamlined approach to incorporate usability testing efficiently and effectively into their development process. The authors advocate a three-tiered assessment approach that includes not only traditional usability but also evaluations of playability and learning. The authors believe that learning is the primary objective of serious games, and enjoyment is often crucial in achieving usage goals; hence, their proposed approach provides step-by-step procedures and associated measures for assessing usability, playability, and learning outcomes concurrently during game development.

According to Caserman et al. [

42], there are three primary types of procedures for serious game evaluation: simple, pre/post, and pre/post/post. In the simple procedure, authors conduct a session with the serious game, and after gameplay, evaluation mechanisms are provided to the players. The pre/post procedure involves two stages of evaluation, one before using the serious game and another after. This procedure is commonly employed by authors assessing the level of knowledge acquisition that players gained through the serious game. The pre/post/post procedure is similar to the pre/post procedure but includes an additional stage. This new stage occurs after a period of weeks or months from the end of the second stage, aiming to evaluate the retention of learned knowledge. The simple procedure stands out as the most prevalent evaluation method. A total of 55% of studies applied a population size of up to 40 people for serious game evaluation. Consequently, evaluations of serious games did not typically involve a large number of participants.

4. Results

4.1. Player-Based Evaluation Results

In the fall term of 2023, thirty-one students enrolled in a 300-level human–computer interaction (HCI) course at a Canadian university were recruited to participate in a study. This opportunity allowed them to experience a usability study from a participant’s perspective, complementing their course requirement to conduct usability studies. As a token of appreciation, participants received a 2.5-mark bonus. The participants ranged in age from 15 to 30 and included 25 males and six females. In terms of ethnicity, 16 identified as Asian, 5 as Middle Eastern or North African, 3 as White, and 5 chose not to disclose their ethnicity. The research was approved by York University’s Research Ethics Review Committee.

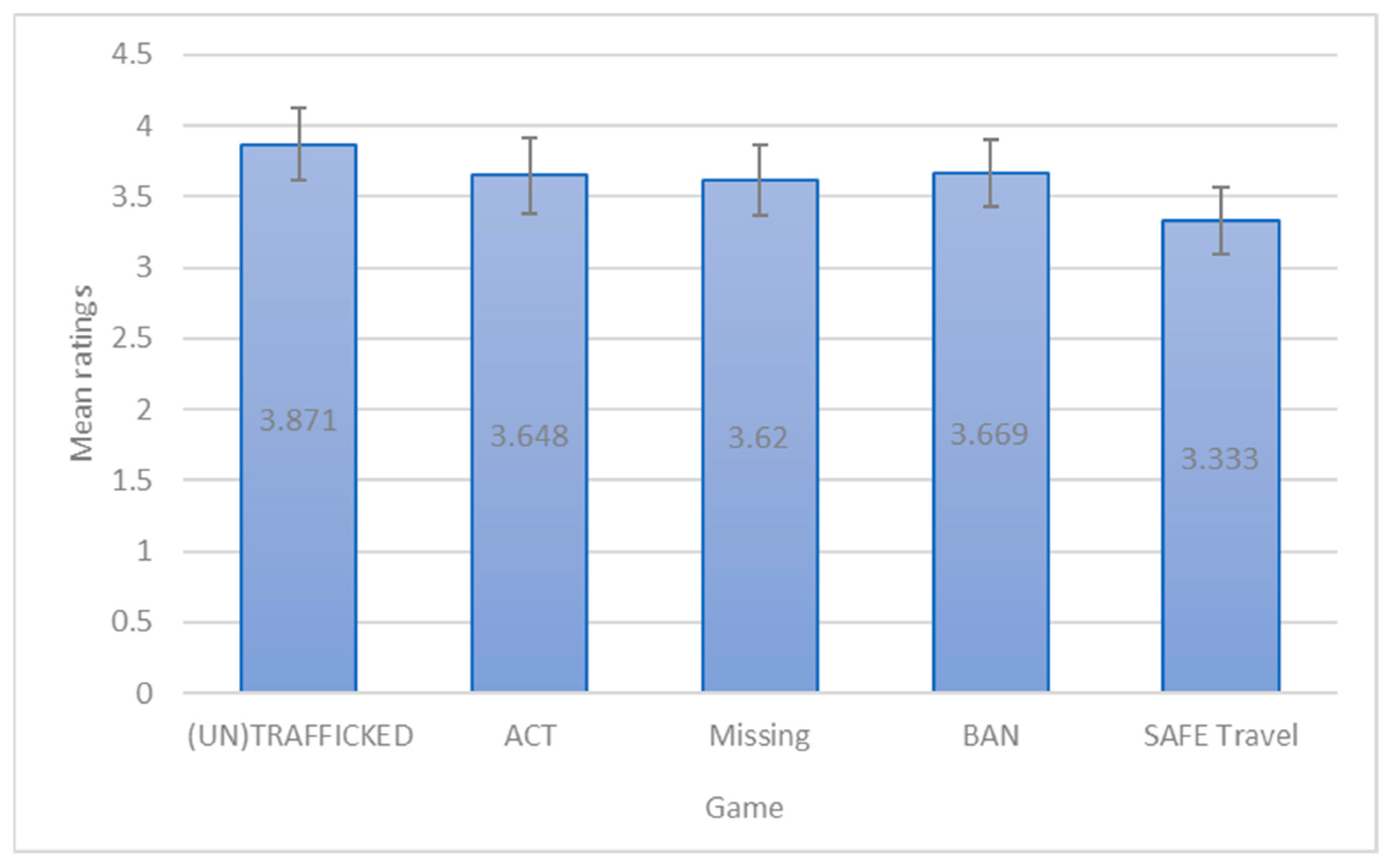

Figure 3 illustrates the mean ratings and confidence intervals of serious games addressing human trafficking (HT). The highest mean rating is associated with (UN)TRAFFICKED, while Safe Travel has the lowest mean rating. The results for ACT, Missing, and BAN demonstrate comparable mean ratings.

Figure 4 displays mean player ratings corresponding to each factor across HT games. The mean values for immersion, audiovisual adequacy, realism, personal interests, and challenge are below 3.5, indicating that the games perform poorly in these factors and there is an opportunity to improve these features of serious games addressing human trafficking. The low value for personal interest suggests that players have little interest in human trafficking information, emphasizing the importance of raising awareness and fostering interest in the subject. The mean values for enjoyment, motivation, narration/storyline, usefulness, and autonomy range between 3.56 and 3.96, indicating moderate ratings for the games in these factors, highlighting opportunities for enhancement. Finally, the mean values for ease of use, feedback, and goal clarity are above 4, signifying the strength of the games in these particular factors.

Figure 5 depicts the mean ratings associated with each factor for human trafficking (HT) games, and

Table 6 presents the top- and bottom-performing games associated with each factor (numbers in parentheses represent the mean ratings). Concerning PF1 to PF7 and PF10 to PF12, (UN)TRAFFICKED outperforms the other games. The top-performing games for PF8, PF9, and PF13 are Missing, ACT, and Safe Travel, respectively. Regarding player-based evaluation, we can infer that (UN)TRAFFICKED is the best-performing game, while Safe Travel is the least favored.

Table 7 highlights the highest- and lowest-performing games for each factor.

We conducted repeated measures ANOVA to compare the players’ game ratings and PF1–PF13 values. Regarding games’ ratings, PF1, and PF3–PF13, the assumption of sphericity was met, and therefore, no correction was applied to the degrees of freedom.

A repeated measures ANOVA determined that mean ratings differed statistically significantly between the games (F(4, 120) = 2.751,

p < 0.031). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the mean game rating was statistically significantly decreased from (UN)TRAFFICKED to Safe Travel 0.538 (95% CI,

p < 0.029).

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10 show the details of ANOVA tests for comparing mean ratings of the games.

To avoid overwhelming the readers, we provide a summary of the results.

A repeated measures ANOVA determined that mean Enjoyment differed statistically significantly between the games (F(4, 116) = 3.565, p < 0.009). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the mean of Enjoyment statistically significantly decreased from (UN)TRAFFICKED to Safe Travel by 0.80 (95% CI, p < 0.021).

A repeated measures ANOVA determined that mean Immersion differed statistically significantly between the games (F(4, 120) = 3.126, p < 0.017). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the mean of Immersion statistically significantly decreased from (UN)TRAFFICKED to Safe Travel by 1.0 (95% CI, p < 0.023).

A repeated measures ANOVA determined that mean Feedback differed statistically significantly between the games (F(4, 120) = 3.328, p < 0.013). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the mean of Feedback statistically significantly decreased from (UN)TRAFFICKED to Missing by 0.774 (95% CI, p < 0.009).

A repeated measures ANOVA determined that mean Narration/storyline differed statistically significantly between the games (F(4, 120) = 3.403, p < 0.011). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the mean of Narration/storyline statistically significantly decreased from (UN)TRAFFICKED to Safe Travel by 0.968 (95% CI, p < 0.010).

A repeated measures ANOVA determined that mean Audiovisual adequacy differed statistically significantly between the games (F(4, 120) = 7.128, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the mean of Audiovisual adequacy statistically significantly decreased from Missing to BAN by 1.226 (95% CI, p < 0.001), and from Missing to Safe Travel by 1.194 (95% CI, p < 0.001).

A repeated measures ANOVA determined that mean Challenge differed statistically significantly between the games (F(4, 120) = 5.892, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the mean of Challenge statistically significantly decreased from (UN)TRAFFICKED to Missing by 0.903 (95% CI, p < 0.005) and from Missing to BAN by 0.806 (95% CI, p < 0.024).

Table 11 outlines the results of thematic analysis based on players’ comments.

4.2. Expert-Based Evaluation Results

Table 12 depicts the results of the correlation analysis conducted on expert ratings. A Pearson correlation of 0.849 indicates a strong correlation between experts’ evaluations. The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level.

Figure 6 illustrates the expert ratings corresponding to serious games addressing human trafficking (HT). The highest mean rating is associated with Missing, while Safe Travel has the lowest mean rating. The mean scores of ACT, BAN, and Safe Travel are below 3.0, indicating poor performance of the games according to expert opinion.

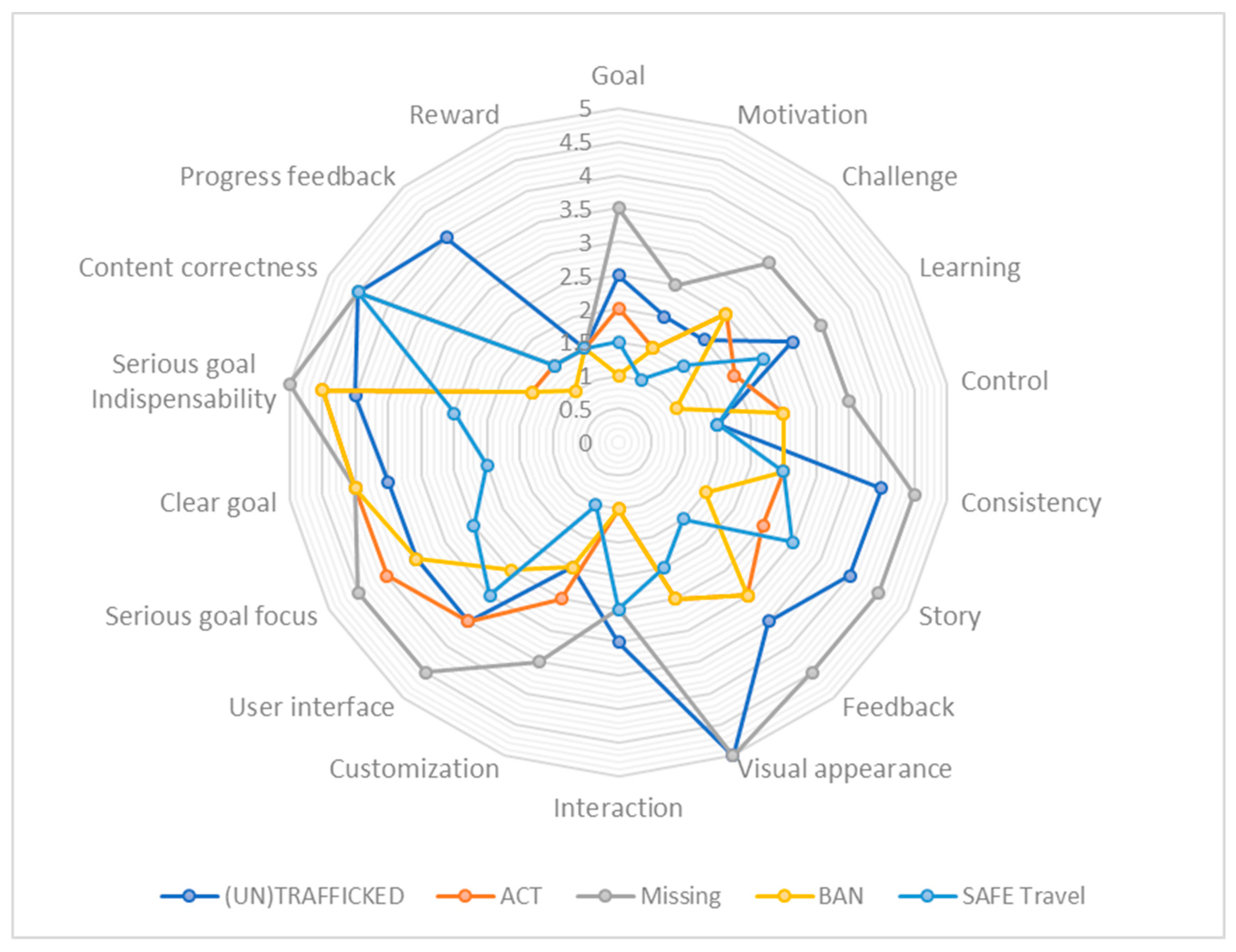

Figure 7 displays mean expert ratings corresponding to each factor across the HT games. The mean values for goal, motivation, challenge, learning, control, interaction, customization, progress feedback, and reward are below 3.0, indicating that the games perform poorly in these factors. The mean value for serious goal indispensability is above 4, signifying the strength of the games in the indispensability of the serious goal. Regarding consistency, story, feedback, visual appearance, user interface, serious goal focus, clear goal, and content correctness, the mean values range from 3.1 to 3.6, indicating moderate ratings for the games in these areas and highlighting opportunities for improvement.

Figure 8 depicts the experts’ mean ratings associated with each factor for human trafficking (HT) games.

Table 13 summarizes expert evaluation comments.

4.3. Discussion

In response to RQ3, based on player and expert evaluations, “(UN)TRAFFICKED” and “Missing” were identified as the best games, respectively. Conversely, “SAFE Travel” was rated the worst by both players and experts. The mean ratings for all games were 3.61 for players and 2.73 for experts, indicating that players rated the games higher than experts did.

According to player evaluations, the games performed well in terms of usability, feedback, and the clarity and usefulness of perceived goals. However, they scored poorly on audiovisual adequacy, realism, relevance to personal interests, and challenge. The low rating for relevance to personal interests suggests that players have limited interest in information about human trafficking, underscoring the need to raise awareness and foster interest in the subject. The thematic analysis of player feedback highlighted issues such as low control, boredom, and low engagement as recurring themes.

From the expert perspective, the games received high ratings only for the indispensability of the serious goal. They were rated very low in areas such as goals, motivation, challenge, learning, control, interaction, customization, appropriate feedback on progress, and appropriate reward.

In response to RQ4, the lack of personalization and customization is evident in HT games, which could be tailored to individual player characteristics to improve effectiveness and user experience. Incorporating social game elements, such as inviting friends and multiplayer options, is vital for raising awareness about human trafficking and enhancing the player experience. Currently, these social game mechanics are absent from HT games. Additionally, it is crucial to develop HT serious games specifically designed for various demographics, including children, adolescents, males, females, parents, therapists, and law enforcement personnel.

Many of the games reviewed suffer from a lack of essential game mechanics. Players often have minimal control over the game, which undermines the interactive experience. The learning effectiveness of these games is questioned, with the impact being described as short term. The games fail to assess or reinforce the learning outcomes, which hinders the long-term retention of HT concepts. Furthermore, the educational content is often incomplete, focusing narrowly on human trafficking signs and outcomes without covering prevention, detection, therapy, or rescue. The games are criticized for their weak visuals and lack of sound effects or background music, which detracts from the immersive experience. Some games are so visually and audibly bland that they are compared to slideshows, failing to engage players on a sensory level.

There is a noticeable absence of reward systems or feedback mechanisms that could reinforce learning and motivate players. The unclear consequences of player choices and the lack of immediate feedback further reduce the effectiveness of these games in educating players about human trafficking. The overall user experience is described as poor, with several games failing to engage or interest the players. The combination of limited interactivity, slow pacing, and a lack of game elements like points, challenges, and badges contributes to this negative assessment.

In response to RQ5, to improve the effectiveness of serious games in combating human trafficking, several avenues for future work are proposed.

The future development of serious games should prioritize incorporating realistic scenarios and narratives that resonate with players, thereby increasing engagement and relevance. Personalization based on player preferences and characteristics, such as personality, culture, and player type, using models like the Hexad Player Type Model [

64], can significantly enhance both the gaming experience and its educational impact. Adding social features, such as multiplayer modes and options to invite friends, can boost player interaction and expand the games’ reach and effectiveness.

Additionally, developing games tailored to specific demographics—such as children, adolescents, men, women, parents, therapists, and law enforcement personnel—can improve the games’ relevance and efficacy in educating diverse audiences. Efforts must also focus on raising awareness about human trafficking to enhance players’ intrinsic interest and the perceived relevance of these games.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study assessed serious games designed to address the critical issue of human trafficking. We conducted a comprehensive investigation of both academic and gray literature to explore the landscape of HT serious games thoroughly. In addition, we examined player and expert evaluation criteria and proposed optimal evaluation metrics for these games. Our method, which combines player and expert evaluations, could be applied to assess other serious games.

In this study, we explored five key research questions related to serious games and human trafficking. First, we examined the current state of publications on serious games addressing human trafficking (RQ1). Next, we investigated how existing human trafficking games can be effectively evaluated (RQ2). We also analyzed the outcomes and insights derived from these evaluations (RQ3). Additionally, we identified gaps in the current serious game landscape related to human trafficking (RQ4). Finally, we proposed future research directions to advance the field of serious games in this context (RQ5).

Our study has highlighted a scarcity of academic publications on serious games related to human trafficking, with only five publications identified. This indicates a need for more research and development in this field. Existing human trafficking games lack thorough evaluation, particularly in applying user-centered design and comprehensive evaluation metrics. Serious games should be evaluated based on both their educational and entertainment components.

Quantitative and qualitative assessments were conducted using both player and expert participants, allowing us to identify the strengths and weaknesses of current game offerings. Notably, the game “(Un)TRAFFICKED” was preferred by players, while “Missing” was favored by experts, highlighting differences in evaluation criteria between these groups. Despite these differences, both groups agreed that “SAFE Travel” was the least effective game.

Players generally rated the games higher than experts, suggesting that while games are user-friendly and offer clear goals, they fall short in terms of realism, relevance, and challenge. The discrepancy highlights a critical gap between engaging gameplay and educational efficacy. Furthermore, the thematic analysis of players’ comments revealed recurring issues such as a lack of control, low engagement, and uninteresting gameplay.

Experts rated the games highly only in terms of goal indispensability, with significant criticism directed at the games’ ability to motivate, challenge, and educate. The lack of personalization and customization was a significant drawback, indicating that serious games need to be more adaptive to individual player needs and preferences.

The future development of serious games should focus on creating realistic scenarios and narratives to increase player engagement and relevance. Developing personalized serious games about human trafficking based on player type, culture, personality, and dominant persuasive strategies can enhance the gaming experience and educational effectiveness. Adding social elements such as multiplayer modes can improve interaction and broaden the game’s impact. Moreover, designing games for specific groups—like children, adolescents, adults, parents, therapists, and law enforcement—can boost their effectiveness in educating varied audiences. Efforts should also aim to raise awareness about human trafficking to heighten players’ interest and the perceived importance of these games.

This study has several limitations. The evaluation of games was based on partial gameplay rather than full engagement, which may have influenced the results. Engaging players in the full game could provide more comprehensive insights into user experience, motivation, and learning outcomes. Additionally, the sample size for player and expert evaluations may not fully represent the diverse demographics intended for these games. Future studies should consider longitudinal evaluations and larger, more diverse participant groups to obtain more generalizable findings.

Some of the survey questions that operationalized the user experience variables were double-barreled. This might have impacted participants’ responses, as some participants might agree to one part of a question to a certain extent but not to the other part. This must have made it difficult for the participants to decide and settle on a specific rating for the double-barreled questions. In future work, we plan to eliminate the double-barreled questions by streamlining and refining them to increase the reliability of participants’ responses.