Abstract

Most people struggle to articulate the reasons why a promotional email they are exposed to influences them to make a purchase. Marketing experts and companies find it beneficial to understand these reasons, even if consumers themselves cannot express them, by using neuromarketing tools, specifically the technique of eye tracking. This study analyses various types of email campaigns and their metrics and explores neuromarketing techniques to examine how email recipients view promotional emails. This study deploys eye tracking to investigate and also verify user attention, gaze, and behaviour. As a result, this approach assesses which elements of an email influence consumer purchasing decisions and which elements capture their attention the most. Furthermore, this study examines the influence of salary and the multiple-choice series of emails on consumer purchasing choices. The findings reveal that only the row that people choose to see in an email affects their purchasing decisions. Regarding promotional emails, the title and brand play a significant role, while in welcome emails, the main factor is primarily the title. Through web eye tracking, it is found that, in both promotional and welcome emails, large images captivate consumers the most. Finally, this work proposes ideas on how to improve emails for similar campaigns.

1. Introduction

Companies in the fashion industry strive to have a strong social presence across various traditional and digital promotion channels for their products. However, their choice to advertise through emails seems to be one of the most profitable options. Knowing that when a consumer is exposed to a stimulus, their buying decision depends on both the characteristics of the stimulus (colours, light, layout, etc.) and factors related to the consumer themselves, such as age, gender, culture, knowledge, experience, and others. Through neuromarketing tools and especially eye tracking, experts can learn more about how to improve their advertising strategies through email.

The roots of this specific advertising method date back to 1971 when the first email was sent by Ray Tomlinson. Seven years later, in 1978, Gary Thuerk created the first mass email campaign (email blast), which was sent to 400 people and generated USD 13 million in sales. By 1991, the internet became accessible to everyone and by 1998, the first email software (Hotmail, etc.) and HTML, enriching email content with colour and graphics, had emerged [1]. Now there are more than 4.26 billion email users worldwide and 70% of consumers prefer companies to communicate with them via email [2]. Furthermore, 99% of active email users check their emails at least once a day, with some checking up to 20 times a day [3]. On average, they spend ten seconds reading promotional emails from companies [4], and 47% of subscribers decide whether to read an email based solely on its subject line [5]. Nearly 59% of consumers claim that their purchasing decisions are influenced by the promotional emails they receive [6]. Furthermore, studies show that multimodal content and respective analysis of marketing intent is a very advantageous means for effective marketing campaigns, such as advertising [7]. Enablers include sensory modalities such as visual and auditory, as well as multi-sensory such as IoT-based techniques [8].

Based on the above, the following research questions are formulated for the basis of this work:

RQ1: How consumers perceive the promotional emails they receive and what elements prompt them to engage in the process of selection and viewing.

RQ2: Which elements in an email capture the participants’ attention the most, and whether what consumers claim to be the persuasive factors are indeed the ones they remember.

RQ3: How the content of emails could be improved to achieve the intended marketing goals.

To address the above, this work assesses which elements of an email influence consumer purchasing decisions and which elements capture their attention the most. Furthermore, this study examines the influence of salary and the multiple-choice series of emails on consumer purchasing choices. The findings reveal that only the row that people choose to see in an email affects their purchasing decisions. Regarding promotional emails, the title and brand play a significant role, while in welcome emails, the main factor is primarily the title. Through a web eye tracker, it is found that, in both promotional and welcome emails, large images captivate consumers the most. Finally, this work proposes ideas on how to improve emails for similar campaigns.

The experimental study measures the user perception of promotional emails and user attention to the email elements using eye tracking. After recording the eye movements of the participants based on six emails with presentation times of 15 s, the participants reported on the elements that attracted their attention the most. The eye tracking data was analysed for three elements (title, discount code, and image size) to suggest improvements for emails in each category.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the related work on email marketing, neuromarketing techniques, and eye tracking. Section 3 presents the experiment design and methodology. Section 4 presents the results derived from the user study and the data analysis. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Email Marketing

For some, email marketing is seen as a means of connection and communication between customers and companies, while for others it is considered a marketing tool with limited intrusive power [9]. Experts utilise email as an advertising tool to strengthen the relationship between companies and consumers, attract new customers, and increase sales. For consumers, subscribing to receive messages aims to receive offers and news, as well as to demonstrate loyalty to the company.

There are six types of email campaigns that any company can use, but, regardless of the quality of the message content and the communication purpose of the company with the customer, this advertising strategy requires the consumer’s consent first, reducing the chance of messages being considered “spam” or deleted [10].

Cold emails are not a popular form of email marketing as they involve the companies’ attempt to introduce and promote products to recipients who have not requested information [11]. The most used email types are welcome, promotional, and newsletter emails. The first are emails that the consumer receives within 24 h of subscribing to a company’s mailing list with the purpose of establishing a positive initial relationship between the company and the customer [12]. The message may include images, videos, links to the company website, or a discount code. Statistically, such emails have an average open rate of 14.4%, while other types of campaigns gather only a 2.7% open rate [13]. Promotional emails have the goal of driving consumers toward purchasing, informing them of a seasonal discount, discount coupons, etc. Newsletter and survey emails have a more “informative” character, with the former being to inform consumers about the releasing of a new product, events, and other activities, and the latter being to inform the company about the costumer’s satisfaction. Finally, there are campaigns designed to reconnect the companies with those customers who remain on the subscriber list but, for some reason, remain inactive in terms of making purchases or actively searching for products. In these emails, the title plays a crucial role [14].

To see if the above email campaigns are effective, companies must monitor in combination seven relevant Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). The open rate indicates how many people open the email which was received, and the click through rate indicate how many people have clicked at least one link contained in the email [15]. The range of this rate is calculated to be from 1% to 5% and can give information about the quality of the context. Click to open rate is a combination of the two above rates, indicating the percentage of subscribers who opened the received email and clicked on a link contained in the message. The average value of the indicator is influenced by factors such as the industry, the time of sending, the country, etc. The highest average value is found in the financial sector, with a percentage of approximately 16.68. The conversation rate shows how many people completed a specific action, which is the goal of the company, and it could be either the purchase of a product or the participation in a contest. The bounce rate shows the percentage of emails that were not delivered to the costumers. The unsubscribe rate is the number people that decided to unsubscribe from the subscriber list. The average value of the two aforementioned indicators is influenced by factors such as the industry type, the time of sending, the country, and others. The last indicator that companies must study is the return of investment, which indicates how profitable the current campaign is. The average return on investment is calculated at USD 36 per USD 1 spent [16]. It varies across industries, with the highest average return being found in the retail, the e-commerce sectors, and the consumer goods sector.

2.2. Neuromarketing

According to Cruz et al., neuromarketing combines techniques from neuroscience, psychology, and marketing to study and record how individuals make conscious and subconscious decisions when faced with stimuli [17]. Various perspectives regarding the role and scientific domain of neuromarketing have been supported in the literature. In 2008, it was described as a research field [18] and as part of neuroscience [19], while in 2010, it was mentioned as part of marketing [20]. Concerning its role, it has been characterized as the application of neuroimaging methods for marketing purposes [21]. Lee, Broderick, and Chamberlain state that neuromarketing, using neuroscientific methods, tends to understand the thinking and behaviour of people in relation to purchasing decisions [22]. Additionally, it has been viewed as a tool that measures consumer desire for a product by examining the brain [23].

Neuromarketing techniques have assisted experts and companies in understanding various aspects of advertising, product packaging, brand value, etc. For instance, a study by Hubert and Kenning showed that advertisements featuring famous or attractive individuals influence consumer purchasing choices by activating an area of their brains involved in building trust with the companies [24]. The Frito-Lay company used EEG to understand how consumers felt after consuming orange Cheetos, finding that customers associated the orange residues on their hands with a pleasant yet guilty pleasure. This insight led to a highly acclaimed advertisement encouraging consumers to indulge in a similar and guiltily enjoyable act [25]. Companies like Yahoo (Sunnyvale, CA, USA), Ford (Dearborn, MI, USA), and Microsoft (Redmond, DC, USA) have also utilised neuromarketing techniques for marketing.

2.2.1. Neuromarketing Techniques

Neuromarketing techniques are categorized into two categories. The first category consists of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and Electroencephalography (EEG), two techniques which measure brain activity. The second category includes eye tracking, Εlectromyogram (EMG), Galvanic Skin Response, and the Electrocardiogram (ECG), techniques which measure neurological and psychophysiological changes [26]. The fMRI technique is a non-invasive imaging technology that captures the brain’s activity by recording oxygenation levels in the blood flow [27]. The visual output of this monitoring, produces images that are refreshed every 2–5 s and consist of 3D cubes called voxels representing thousands of neural cells (neurons) [28]. Brain regions, when activated, are visually presented in colour to distinguish them from inactive areas. EEG measures an individual’s brain activity by detecting electrical brain waves using electrodes placed on the scalp or through a specialized helmet equipped with sensors and electrodes. The major advantage is that brain signals can be measured quickly, up to 10,000 times per second [29], revealing subconscious processes and reactions occurring before conscious awareness. A disadvantage is that electrodes measure electrical activity near the surface of the brain and not in deeper layers.

Eye tracking is a technique that allows for the study and recording of eye movements which are decoded into a series of data related to the time an individual spends looking at a specific stimulus, the time taken to shift from one visual point to another, the trajectory of eye movement, etc. Recording eye movement can be achieved through various tools and software, including specialized contact lenses with mirrors or magnetic field sensors, monitoring glasses, web cameras, etc. This technique is revealing, but it cannot connect emotions with visual fixation [30]. Electromyography is a technique that records both voluntary and involuntary muscle movements in the face, reflecting emotional reactions to a marketing stimulus [31]. Electrodes are placed on the frontalis muscle, eye muscles, and zygomatic region to measure this activity. It is a portable technology, and its cost depends mainly on the number of integrated sensors. One limitation is the challenge of studying and recording facial muscles due to the potential negative impact on participants’ emotions [32]. Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) measures the electrical conductivity of the skin, reflecting changes in sweat gland activity due to emotional states (joy, sorrow, stress, etc.). One disadvantage is that GSR measures only the intensity of the emotions. Electrocardiogram (ECG) measures the electrical activity of the heart, recording changes in heart rate in response to stimuli experienced by the consumer. Some advantages of ECG include its low cost, short average time of 15 min required for the experiment, and the ability to collect real-time information about participants’ non-conscious emotional arousal [33].

2.2.2. Ethical Concerns

Neuromarketing is a burgeoning field of research that has both supporters and sceptics. Some researchers liken neuromarketing to a “holy grail” that will help unravel the mystery of how people choose to consume goods and services. On the contrary, opposing views argue that marketing experts will gain complete control over consumers’ minds [34]. Concerns and objections mainly focus on companies’ ability to predict consumer decisions, issues of privacy, and the potential for addiction. There are also fears that consumers might be deceived and subjected to experiments without their consent. These concerns arose after studies demonstrated that tools like fMRI and EEG can predict consumer preferences [35,36,37]. On the other side, there are researchers and experts who advocate the opposite view. Stanton, Sinnott-Armstrong and Huettel argued that concerns about neuromarketing are based on a perceived exaggeration of its power compared to other forms of marketing [38]. Support for this perspective comes from other studies as well, which assert that the consumer decision-making process is a result of multiple factors [39,40]. Additionally, it is argued that while there are brain regions associated with reward and value, there is no clear indication that the “buy button” of consumers can be directly influenced [41,42].

2.3. Eye Tracking Technique

Eye tracking is one of the many tools in neuromarketing that studies eye movements and analyses consumer behaviour based on these movements [43]. The collected data can provide valuable insights into questions related to the stimuli consumers are exposed to, such as (a) which part of the stimulus captured their gaze the most, (b) the duration of fixation, (c) the sequence of eye fixations, and more.

The study of eye movements first emerged in the 19th century, initially using natural observation by researchers studying reading behaviour. The first experiment in this regard was conducted in 1870 by the French ophthalmologist Louis Émile Javal, who demonstrated that the reading process involves short movements, fixations, and rapid eye alternations, challenging the linear model of continuous eye movement along a line [44]. In the 1980s, the field of marketing began using eye tracking to measure the effectiveness of advertisements in magazines, providing information to specialists about fixation duration, focus areas, and more [45]. Edmund Huey, in 1908, developed the first intrusive eye-tracking device resembling contact lenses with a small opening in the iris area. Subsequently, Dodge and Cline created a non-intrusive device based on corneal reflection, recording only horizontal eye movements. Charles H. Judd improved this device to capture both horizontal and vertical eye movements [46]. In 1948, Hartridge and Thompson developed the first head-mounted eye-tracking device, and nearly 40 years later, in 1980, the study and real-time recording of eye movements began using computers [47].

Considered more reliable than self-reported responses from consumers, eye tracking has found applications in various marketing studies, including product packaging, advertisements, website design, etc. [48] For example, studies on baby product companies revealed that when babies in ads make direct eye contact with the consumer, the consumer’s attention is directed towards them without necessarily noticing the advertised product [49].

2.3.1. Basic Elements of Eye Tracking Measurements

Eye movements studied by experts depend on the type of stimulus. For static stimuli like an image or text, the examined eye movements are fixations and saccades. Conversely, for dynamic stimuli like a video, smooth pursuit is recommended [50].

Fixation is the gaze staying on a specific element of the stimulus and its duration ranging between 100 and 600 milliseconds. It is the primary function of the eyes, providing useful information on how the consumer interprets and interacts with data [51]. The interpretation of longer fixations depends on the experiment’s goal. The most common calculations for this measurement include frequency (fixation count), duration (fixation duration), and location. Saccades involve rapid eye movements between points of interest (fixations) and usually last between 30 and 80 milliseconds [52]. They are visually represented by straight lines and common measurements focus on saccadic amplitude, duration, and velocity. Furthermore, smooth pursuit is the continuous tracking of a moving stimulus, characterized by eye movements that are not considered unconscious, as participants can choose whether to follow the moving stimulus or not [53]. Smooth pursuit can track a stimulus at speeds of approximately 30%. Last, experts measure pupil dilation because it is a reliable measure of cognitive and emotional states [54]. Pupil dilation is influenced by various factors such as exposure to emotionally charged stimuli, processing difficulty, brightness, etc. [55]. Common measurements include pupil diameter and the percentage change in dilation [56].

2.3.2. Data Visualizations

There are four types of visualization for the eye tracking data. The most common is the heat map of fixation [57]. Primarily, four basic colours (red, yellow, green, or blue) are used to represent areas and the degree of consumer focus during exposure to a stimulus. Colours indicate the level of consumer fixation, with red indicating the most interesting area and green–blue indicating the least interesting area. Another one is a click heat map, which helps experts to understand the points where consumers clicked and how many times. Visualization is conducted using warm and cool colours (red, yellow, green, and blue), employing the same interpretation as in the fixation heat map [58]. This technique is mainly used to enhance the user experience on websites and web pages. Lastly, a mouse heat map uses colours in order to represent the directions the user’s mouse took during exposure to a stimulus. Research has shown a 64% correlation between where people look and mouse movements [59]. Like the fixation heat map, data representation uses the aforementioned colour palette, with red indicating the area where the computer mouse lingered the longest. Finally, there are the scan path maps where both fixations and saccades are visualized. Fixation points are represented by numbered dots, and transitions are depicted by straight lines connecting the fixations. Numbered dots indicate areas where the consumer focused more, with the size of each dot proportional to the duration of fixation [60]. The lines, on the other hand, relate to the distance and speed between fixations.

2.3.3. Factors Influencing Purchasing Decisions

Purchasing decision is a process involving various factors. When a consumer is exposed to a stimulus, their attachment to it depends on both the characteristics of the stimulus (colours, lighting, layout, etc.) and factors related to the consumer themselves (age, gender, culture, knowledge, experience, etc.) [61]. Rathee and Rajain demonstrated that both colours and the reputation of a company directly influence the purchasing choices of the public [62]. A single colour alone can shape the consumer’s perception of the quality, price, and value of a product. Rambabu and Porika showed that colours like gold and silver are often associated with higher prices, while white and green are associated with lower prices [63]. Ozkul et al. revealed that in the fashion industry, consumers prefer to buy brightly coloured clothes during the summer months due to the emotional connection between light-coloured clothing and good weather [64]. Conversely, during winter months, consumers prefer darker-coloured garments for emotional comfort and warmth. Numerous studies have examined how consumer behaviour varies based on gender. Firstly, the initial difference lies in how the two genders perceive colours during clothing purchases. Puccinelli and Rajesh showed that during purchases, men perceive price tags in red as a sign of spending less money, unlike women who become more cautious in their spending when faced with this colour [65]. Conversely, for women, price tags in black are associated with thriftiness. The same research revealed that the female gender has better memory regarding clothing prices. Moreover, according to recent studies, women tend to be more positive towards online shopping and are more influenced by online reviews [66,67]. Lastly, Tifferet and Herstein stated that the commitment of both genders to company brands is related to risk aversion, with women being more attached to companies they are familiar with compared to men [68].

3. Materials and Methods

This section provides participant information and describes the experiment design and data analysis methods that this work followed.

3.1. Participants

The participants in the survey came mainly from the academic community, including university students, and from other communities. The survey link was shared to them via academic email. As shown in Table 1, a total of 54 individuals participated, of whom 35 (64.8%) were females and 19 (35.2%) were males.

Table 1.

Gender distribution of respondents.

The ages of male participants ranged from 23 to 54 years, while female participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 60 years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Age distribution of respondents.

A total of 68.5% of the participants stated that they are employed in the private sector, 16.7% indicated they are public servants, while only 3.7% reported working as freelancers. Three participants stated that they were students and another three mentioned that they were unemployed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Profession distribution of respondents.

Regarding monthly income, 75.9% of the participants reported that their monthly earnings ranged from EUR 650 to EUR 1499 and only 9 participants stated that their earnings exceeded EUR 1500 and reached EUR 1999 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Monthly income distribution of respondents.

3.2. Experiment Design and Data Analysis

Given that consumers need to have given their consent to receive promotional emails from companies, it was assumed that at some point in the past, the participants had taken such an action. Additionally, to explore the reasons influencing consumers’ selection of emails, it was hypothesized that users received the same emails on the same day and in the same order in their email inbox.

The experiment consisted of two phases: the first involved the process of eye tracking and the second involved completing the questionnaire. The experiment was conducted remotely. For the eye tracking part, we used an online remote eye tracker, which was more affordable than laboratory eye tracking equipment. Additionally, the remote eye tracker allowed the experiment to be conducted with two or more people simultaneously. The eye tracking was carried out through the RealEye.io platform, which is supported by many universities, such as Stanford.

RealEye.io is an online platform that provides tools for eye-tracking research, enabling studies using a simple webcam. The sampling rate is 30 Hz, meaning data is collected every 33 ms, with an average measurement accuracy of 110 px. One limitation of this platform is the eye tracker recording eye movements only in horizontal motion and it plays only to the Google web browser. Furthermore, surveys can be conducted on mobile phones only by purchasing the platform’s premium package. In our case, we selected an affordable package, which excluded people who wanted to participate in the survey using their mobile phone. This means that the data which have been collected are only from participants who used their laptop or PCs.

The second part of our experiments involves the questionnaire which is set up using the Google Forms platform. The link was shared with university colleagues and professors via academic email.

At the beginning of the experiment, participants viewed the following email titles: (a) Tommy Hilfiger: Tommy Outlet Days: Ladies First! (b) Pink Woman: New Now, (c) Nash: Welcome to NASH! (d) About You: Congratulations, you are now a member of the ABOUT YOU family! (e) Lacoste: You just gained −10% for your next purchase! (f) Prince Oliver: Super Prices from EUR 29.99. These titles correspond to two different types of email campaigns (promotional and welcome) from six different clothing companies. All 6 emails were from real companies’ campaigns. The emails were carefully selected as the most representative to each campaign’s core target, and they were for the most part different to one another. These email campaigns included elements such as large clothing images, discount codes, prices, prices with different colour, catchy titles, etc. According to Thomas et al. [3], people spend almost 10 s of their time viewing promotional emails. Keeping this in mind and wanting to avoid making participants bored, we decided that 6 emails in total would be appropriate for the user study as well as sufficient to draw conclusions on the research questions. Participants were asked to choose and view up to 3 emails. By clicking on an email, they were redirected to the Realeye.io program. After completing the necessary instructions for calibration, which involves identifying the user’s gaze for accurate coordinate production on the screen, the content of the selected emails started to be displayed, one email at a time, with a maximum duration of 15 s (Figure 1). After the 15 s interval, the presentation of the content ended. As the final requirement, participants were asked to fill in their gender, age, and name.

Figure 1.

Emails set as stimuli for the experiment in the order they appeared to the consumers.

In the second phase, participants were required to answer nearly 15 questions regarding the content of the emails they viewed. The first question asked participants to provide the name they had used in the eye tracking stage to facilitate the matching of eye tracking data with their questionnaire responses.

4. Results

In order to examine the habits and behaviour of individuals when receiving promotional and informational emails, participants were asked about the timing of when they read such emails. The majority of the participants (31.5%) stated that they primarily check their emails in the evening. The next significant percentage, 24.1%, indicated that they choose the afternoon to read promotional emails, while only 1 in 10 participants reads emails at noon. It is worth noting that only 14 participants out of the total 54 stated a preference for checking promotional emails at two different times of the day with 8 of them mainly choosing the afternoon and evening. Additionally, beyond the timing, participants were questioned about the frequency with which they check the promotional emails they receive. A total of 43.4% of participants reported that they rarely open promotional emails while 30.2% of them mentioned that they check them frequently. Furthermore, 18.9% of participants mentioned that they open such emails every time they receive them while only 3 participants said they do not see them at all.

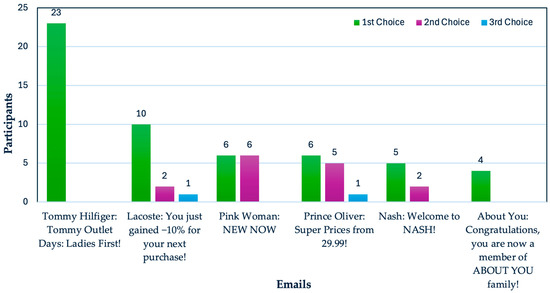

In the continuation of this study, with the aim of examining what motivates recipients to click and read such an email, participants were questioned about the number and sequence of emails they chose to view. A total of 27 people chose to see only 1 email, 23 of them viewed the email from Tommy Hilfiger and the remaining 4 viewed the email from About You. The other 15 participants viewed 2 emails, and only 2 people viewed 3 emails (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sequence of emails.

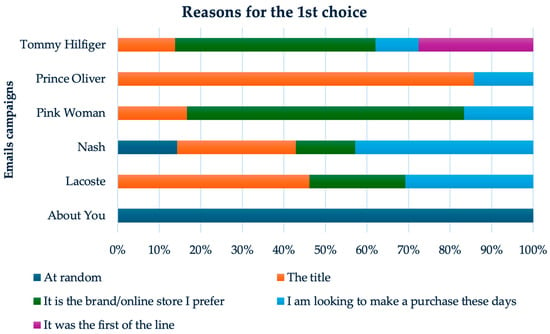

For the Tommy Hilfiger company, participants stated that the main reasons were primarily the brand/name and the title, with appearance percentages of 43.3% and 18%, respectively. For the Pink Woman company, the main reason was the brand (66%), while for the Lacoste and Prince Oliver companies the main reason was the email title with appearance percentage of 41% and 85,7% respectively. For the Nash company’s email, the main reasons were that people were looking to make a purchase during this period (43%) and the email title (29%). For the About You company, 100% of those who chose it first mentioned that the choice was made by chance (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reasons why participants chose to view their first choice.

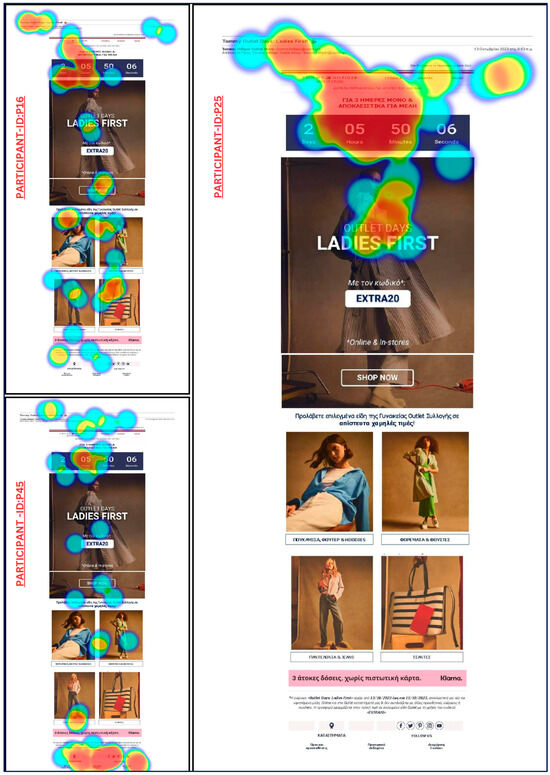

After the eye-tracking experiment, we asked participants which elements of the email’s content captured their interest the most and whether they would proceed to visit the respective online store. The 23 individuals who chose to view the email from Tommy Hilfiger stated that they were primarily attracted by the title, the discount code, and the images. However, only 16 of them would proceed to visit the online store.

Furthermore, it is observed that the average fixation duration for individuals who stated that they were attracted by the title is 0.2 s (Aver. Time spent = 0.2 s), while the average time required for the initial detection of the title is 0.97 s (aver. FFTG = 0.97 s). Regarding the discount code, the average fixation duration for individuals who mentioned that they were attracted by the code is 0.8 s (aver. time spent = 0.8 s), and the average duration for the first detection is calculated at 4.02 s (aver. FFTG = 4.0 s). Additionally, for large images, the average fixation duration is calculated at 4.63 s (aver. Time spent = 4.63 s) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Eye tracking data for the Tommy Hilfiger email.

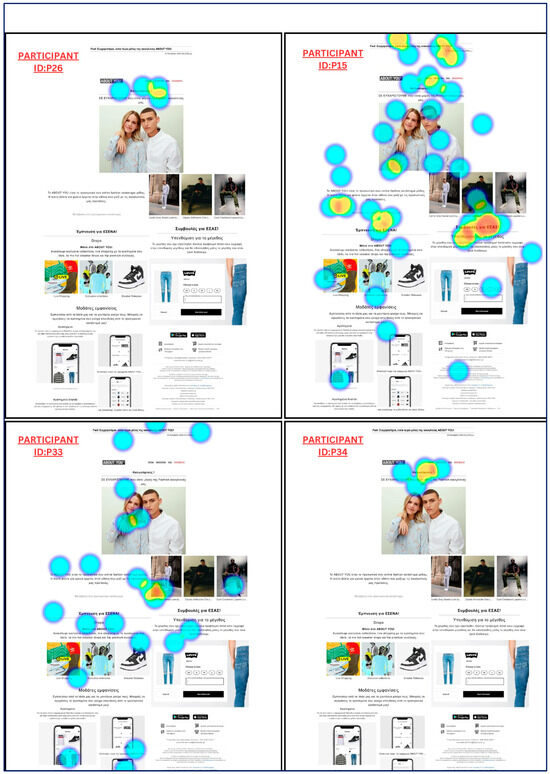

Additionally, there are seven participants who stated that they were attracted either by the discount code or the email title, but no gaze fixation was recorded (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Heatmaps for participants who stated that they were captivated by the discount code in the Tommy Hilfiger email without measurements.

As for the company Nash, five individuals stated that they were captivated by the large image inside the email, while only three individuals mentioned that the discount code captured their interest. Only two people would proceed to visit the online store (Table 6).

Table 6.

Eye tracking data for the Nash email.

The average duration of fixation on the image and clothing suggestions (in this case, the large image is the same as the clothing suggestions) reaches a total of 3.27 s (Aver. Time spent = 3.27 s); one of the two consumers who will proceed to purchase ultimately remembers the discount code, which has an average fixation duration of 0.9 s (Aver. Time spent = 0.9 s), a shorter duration compared to the images that captured their interest.

For the company Lacoste, 58.8% of participants stated that they were primarily drawn to the discount code, while 29.4% liked the title of the email (Table 7).

Table 7.

Eye tracking data for the Lacoste email.

The average fixation duration of participants in the area of the discount code is calculated at 0.43 s (Aver. Time spent = 0.43 s), while for the title of the email, it is 0.53 s (Aver. Time spent = 0.53 s). It is worth noting that the large image in the centre of the email captured participants’ attention for approximately 3.16 s (Aver. Time spent = 3.16 s). Additionally, almost half of the 13 participants who viewed this specific email stated that they would visit the company’s online store, with 55.6% of them supporting that what they ultimately remember is the discount. Finally, it is worth mentioning that in this case, there are five individuals who stated that they liked the title, but there are no eye-tracking measurements to confirm this claim (Table 7).

For the Pink Woman company’s email, the elements that captured people’s interest the most were the clothing suggestions and the prices (44.4% and 33.3%, respectively) (Table 8). The average fixation duration in the area of prices is calculated at 2.26 s (Aver. Time spent = 2.26 s), while the clothing suggestions have an average fixation duration of 2.06 s (Aver. Time spent = 2.06 s). Additionally, 58.3% of participants stated that they would not visit the company’s online store, while the remaining 41.7% said they would. Finally, among the 41.7% of people who were positive about visiting the online store, 25% remembered the images, while only 16.66% remembered the prices. The title was considered relatively uninteresting.

Table 8.

Eye tracking data for the Pink Woman email.

For the company Prince Oliver, 58.3% of participants stated that, after seeing the content of the email, the element that captured their interest was the title of the message, of which only 8.3% have recorded eye-tracking results (Table 9). Participants who mentioned that the clothing suggestions captured their interest had an average fixation duration of 5.47 s (Aver. Time spent = 5.47 s), and it took them an average of 4.34 s to locate that specific area (Aver. TTFG = 4.34 s). Regarding the price area, participants fixated their gaze for an average of 1 s (Aver. Time spent = 1 s). Specifically, only 50% of the sample would visit the company’s online store.

Table 9.

Eye tracking data for the Prince Oliver email.

Finally, the longest average fixation duration (time spent) is found in the clothing area (9.59 s), while the shortest is in the price area (0.78 s). Participants took approximately the same amount of time to first locate both the price area and the clothing suggestions (Aver. FFTG = 4.5 s and Aver. FFTG = 4.34 s, respectively). Additionally, no difference is observed between what initially captured their interest and what they ultimately stated they remembered.

For the company About You, three out of the four participants stated that nothing from the content of the email they were exposed to, captured their interest (Table 10).

Table 10.

Eye tracking data for the About You email.

Their responses are visually confirmed, as shown in the image below (Figure 5), where participants looked at the content but did not focus on any specific area. Only one out of the four mentioned that the central image captured his interest, with a maximum fixation duration of 0.45 s (Aver. Time spent = 0.45 s). It is worth noting that, only one person would proceed to visit the online store without remembering anything from the content they saw.

Figure 5.

Heat maps for participants of “About You” email.

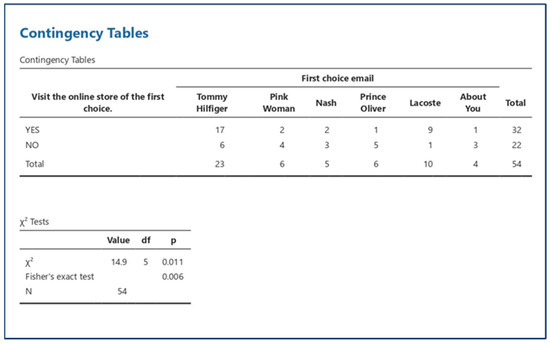

In terms of the factors, we examined whether salary influenced the participants regarding their first choice of the title, but there did not seem to be a correlation between these two variables. With the help of a χ2 test, we demonstrated that there is a correlation between their first choice of email and their final decision to visit the respective store (p-value = 0.011 < 0.05) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The results of the Chi-square (χ2) test for the variables: (a) final intention to visit the online store, and (b) first choice of email.

In order to suggest a few improvements, we compared the average fixation and average time to first fixation for three elements (title, discount, and large image) in the emails between participants who stated they would visit the respective online store and those who would not. Regarding the companies that sent welcome emails (Nash, About You, and Lacoste), we observed that for the Nash company, the discount code was not immediately identified by consumers, as five out of seven individuals who would potentially make purchases needed an average of 6.70 s (Av. TTFG = 6.70 s) to locate it (Table 11).

Table 11.

The average fixation duration and time to first fixation for the title, discount code, and images of companies with welcome emails (left). The average fixation duration and first gaze time for the title, discount code, prices, and images of companies with promotional emails (right).

The same applies to the Lacoste company, where 7 out of 13 participants needed an average of approximately 4.80 s (Av. TTFG= 4.80 s). As for the large images, in all three companies, they seem to be located relatively quickly by both categories of participants. The Nash company’s image exhibits the longest fixation, while About You’s image shows the shortest fixation.

Regarding the companies of promotional emails, two of them chose to display some indicative prices of their products in the email content, while Tommy Hilfiger chose to offer a discount through a code. Large images seem to capture the attention of consumers more than the discount code or the prices that may appear. As for the prices of the two companies, in both cases, consumers took a considerable amount of time on average to locate them. Specifically, consumers of Pink Woman and Prince Oliver, who would visit the respective online stores, needed an average of 8.33 s and 4.90 s, respectively. This means that Pink Woman consumers had difficulty detecting indicative prices on the right side of the message, unlike Prince Oliver consumers who saw the prices on the left side of the message in less time. It is worth noting that the prices in the first case were in black colour, while in the case of Prince Oliver, they were in red (Table 11).

In the case of Tommy Hilfiger, the fact that consumers focused more on the image with a fixation duration of 4.43 s compared to the code, which gathered an average fixation duration of 0.88 s, is likely due to the position of the code, which was placed at the end of the large image.

5. Discussion

The aim of this work was to study how consumers perceive promotional emails and identify the factors that influence their decision to open and view such emails. Additionally, through eye tracking, this study aimed to determine which elements of an email captured participants’ attention and what consumers remembered after visiting the corresponding online store. Finally, based on eye-tracking results, the research intended to propose ideas on how to improve emails for similar campaigns.

Other studies and general marketing beliefs had considered that discount coupons and their positions are the main attraction for potential buyers [69,70]. This study found that larger images overwhelm the users’ attraction, resulting in underwhelmed attraction to the other visual bits, such as the discount images.

Regarding RQ1, which focused on consumer behaviour and the factors influencing their decision to click and view an email, this study revealed that in promotional emails, the title and brand play a significant role, while in welcome emails, the title is the primary factor.

Regarding RQ2, which aimed to identify the elements of an email that attract consumers’ attention, eye-tracking showed that both in promotional and welcome emails, large images captured more of the consumers’ interest.

Finally, concerning RQ3, which focused on the promotional email content provision for improved efficiency, it is recommended for welcome emails to pay attention to the placement of discount codes, as they may be overshadowed by a large image. Moreover, suggesting the inclusion of more prominent images of clothing in welcome emails is advised, as they tend to capture consumers’ attention more effectively. Regarding promotional emails containing indicative prices, attention should be paid to their placement within the text. The research demonstrated that prices on the right side of the message and in red colour are more easily perceived than those placed on the left side and in black colour.

6. Conclusions

We conducted a human study with 54 participants, using an eye tracker to examine how people perceive welcome and promotional emails. The primary finding is that large images of clothing capture the attention more than promotional codes and prices.

This research has some limitations. One of those is that this study focused on the average fixation duration of participants regarding the title, the discount code, images, and prices but did not map out in what sequence consumers’ gaze wandered through the content. Additionally, the images in the studied emails were static; therefore, it is suggested to study emails with image variations to achieve more reliable results. Finally, another limitation is that we studied the discount codes and prices concerning their position and did not examine how their colour and font may have influenced consumers’ detection. It is recommended that a more thorough investigation be conducted regarding these aspects. In the end, the above outcomes might differ if the same survey were conducted on mobile devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and D.S.; methodology, E.S. and D.S.; software, E.S.; validation, E.S. and D.S.; formal analysis, E.S.; investigation, E.S.; resources, E.S.; data curation, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S. and D.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S. and D.S.; visualization, E.S.; supervision, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Neapolis University of Pafos (date of approval: 13 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this work are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the anonymous participants that took part in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Silic, M.; Back, A.; Silic, D. Email: From Hero to Zero–the Beginning of the End? J. Inf. Technol. Teach. Cases 2015, 5, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.; Wakefield, K.L. Modeling the Consumer Journey for Membership Services. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.S.; Chen, C.; Iacobucci, D. Email Marketing as a Tool for Strategic Persuasion. J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 57, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, B.; Carneiro, R. Opening E-Mail Marketing Messages on Smartphones: The Views of Millenial Consumers. In Proceedings of the CBU Economics and Business 2022, Prague, Czech Republic, 16 March 2022; Volume 3, pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Tsou, M. The Impact of Incentive Framing Format and Language Congruency on Readers’ Post-Reading Responses to Email Advertisements. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3037–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligaraba, N.; Chuchu, T.; Nyagadza, B. Opt-in e-Mail Marketing Influence on Consumer Behaviour: A Stimuli–Organism–Response (S–O–R) Theory Perspective. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2184244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yu, L. Multimodal Marketing Intent Analysis for Effective Targeted Advertising. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 24, 1830–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirandazi, P.; Bamakan, S.M.H.; Toghroljerdi, A. A Review of Studies on Internet of Everything as an Enabler of Neuromarketing Methods and Techniques. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 7835–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, J.; Daniels, D. Email Marketing: An Hour a Day; Wiley Publication: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-470-38673-6. [Google Scholar]

- Valenti, A.; Srinivasan, S.; Yildirim, G.; Pauwels, K. Direct Mail to Prospects and Email to Current Customers? Modeling and Field-Testing Multichannel Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2024, 52, 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabab’ah, G.; Yagi, S.; Alghazo, S.; Malkawi, R. Persuasive Strategies in Email Marketing: An Analysis of Appeal and Influence in Business Communication. J. Intercult. Commun. 2024, 24, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsnorth, S. Digital Marketing Strategy: An Integrated Approach to Online Marketing; KoganPage: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-7494-8422-4. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, R.; Gupta, S.; Hamilton, R. Marketing Insights from Multimedia Data: Text, Image, Audio, and Video. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 58, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, Y.J. Digital Marketing Strategy to Increase Sales Conversion on E-Commerce Platforms. J. Contemp. Adm. Manag. ADMAN 2023, 1, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.P.; De’Villiers, R. Elaboration of Marketing Communication through Visual Media: An Empirical Analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goic, M.; Rojas, A.; Saavedra, I. The Effectiveness of Triggered Email Marketing in Addressing Browse Abandonments. J. Interact. Mark. 2021, 55, 118–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.M.L.; Medeiros, J.F.D.; Hermes, L.C.R.; Marcon, A.; Marcon, É. Neuromarketing and the Advances in the Consumer Behaviour Studies: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2016, 17, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.R.; Illes, J.; Reiner, P.B. Neuroethics of Neuromarketing. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrachione, T.K.; Perrachione, J.R. Brains and Brands: Developing Mutually Informative Research in Neuroscience and Marketing. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.E.; Chin, L.; Klitzman, R. Defining Neuromarketing: Practices and Professional Challenges. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariely, D.; Berns, G.S. Neuromarketing: The Hope and Hype of Neuroimaging in Business. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Broderick, A.J.; Chamberlain, L. What Is ‘Neuromarketing’? A Discussion and Agenda for Future Research. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2007, 63, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, M. Some Ethical Issues in Brain Imaging. Cortex 2011, 47, 1272–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.; Kenning, P. A Current Overview of Consumer Neuroscience. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Neuromarketing: The New Science of Advertising. Univers. J. Manag. 2015, 3, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta-Olearnik, M.; Szulga, P. The Importance of Emotions in Consumer Purchase Decisions—A Neuromarketing Approach. Mark. Sci. Res. Organ. 2022, 44, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, A.K. The Buying Brain: Secrets of Selling to the Subconscious Mind; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-60177-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zurawicki, L. Neuromarketing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-540-77828-8. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, C. Neuromarketing: The New Science of Consumer Behavior. Society 2011, 48, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, V.C.R.; Giraldi, J.D.M.E.; De Oliveira, J.H.C. A Review of Studies on Neuromarketing: Practical Results, Techniques, Contributions and Limitations. J. Manag. Res. 2014, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubino, P.; Martinez-Levy, A.C.; Caratù, M.; Cartocci, G.; Di Flumeri, G.; Modica, E.; Rossi, D.; Mancini, M.; Trettel, A. Consumer Behaviour through the Eyes of Neurophysiological Measures: State-of-the-Art and Future Trends. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 2019, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda Calero, J.A.; Paez-Montoro, A.; Lopez-Ongil, C.; Paton, S. Self-Adjustable Galvanic Skin Response Sensor for Physiological Monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 3005–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Sebastião, R. Using the Electrocardiogram for Pain Classification under Emotional Contexts. Sensors 2023, 23, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Bush-Evans, R.; Arden-Close, E.; Bolat, E.; McAlaney, J.; Hodge, S.; Thomas, S.; Phalp, K. Transparency in Persuasive Technology, Immersive Technology, and Online Marketing: Facilitating Users’ Informed Decision Making and Practical Implications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telpaz, A.; Webb, R.; Levy, D.J. Using EEG to Predict Consumers’ Future Choices. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wang, Y. Using Neural Data to Forecast Aggregate Consumer Behavior in Neuromarketing: Theory, Metrics, Progress, and Outlook. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 2142–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzir, M.; Chakir Lamrani, H.; Bradley, R.L.; El Moudden, I. Neuromarketing and Decision-Making: Classification of Consumer Preferences Based on Changes Analysis in the EEG Signal of Brain Regions. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 87, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, S.J.; Sinnott-Armstrong, W.; Huettel, S.A. Neuromarketing: Ethical Implications of Its Use and Potential Misuse. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Mohd Isa, S. Revolutionizing Consumer Insights: The Impact of fMRI in Neuromarketing Research. Future Bus. J. 2024, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Rana, G.A.; Behl, A.; Gallego De Caceres, S.J. Exploring the Boundaries of Neuromarketing through Systematic Investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, C.; Lee, N. A Manifesto for Neuromarketing Science. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg-Martin, E.S.; Feng, Y.-Y.; Ogasawara, T.; White, J.K.; Zhang, K.; Monosov, I.E. A Neural Mechanism for Conserved Value Computations Integrating Information and Rewards. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iloka, B.C.; Anukwe, G.I. Review of Eye-Tracking: A Neuromarketing Technique. Neurosci. Res. Notes 2020, 3, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wang, X.; Xu, H. Eye-Tracking in Interpreting Studies: A Review of Four Decades of Empirical Studies. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 872247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macele, P.; Mueggenburg, J. Playing with the Eyes. A Media History of Eye Tracking. In Disability and Video Games; Spöhrer, M., Ochsner, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 117–143. ISBN 978-3-031-34373-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, F.; Liu, R.; Sokolikj, Z.; Dahlstrom-Hakki, I.; Israel, M. Using Eye-Tracking in Education: Review of Empirical Research and Technology. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 1383–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhilo, T.; Al-Sakaa, A. Eye Tracking Review: Importance, Tools, and Applications. In Emerging Trends and Applications in Artificial Intelligence; García Márquez, F.P., Jamil, A., Hameed, A.A., Segovia Ramírez, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 960, pp. 383–394. ISBN 978-3-031-56727-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ursu, R.M.; Erdem, T.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q. Prior Information and Consumer Search: Evidence from Eye Tracking. Manag. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, N.; Singh, J. Understanding Online Consumer Behavior at E-Commerce Portals Using Eye-Gaze Tracking. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.; Nyström, M.; Andersson, R.; Stridh, M. Detection of Fixations and Smooth Pursuit Movements in High-Speed Eye-Tracking Data. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2015, 18, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn, D.; Hepburn, J. Eye-Tracking in Map Use, Map User and Map Usability Research: What Are We Looking For? Int. J. Cartogr. 2023, 9, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llapashtica, E.; Sun, T.; Grattan, K.T.V.; Barbur, J.L. Effects of Post-Saccadic Oscillations on Visual Processing Times. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulsham, T. Eye Movements and Their Functions in Everyday Tasks. Eye 2015, 29, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startsev, M.; Zemblys, R. Evaluating Eye Movement Event Detection: A Review of the State of the Art. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 55, 1653–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, R.; Milshtein, D.; Henik, A. The Contribution of Temporal Analysis of Pupillometry Measurements to Cognitive Research. Psychol. Res. 2023, 87, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Pieters, R.; Van Der Lans, R. Modeling Eye Movements During Decision Making: A Review. Psychometrika 2023, 88, 697–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Lv, J. Review of Studies on User Research Based on EEG and Eye Tracking. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Duffy, M.C.; Lajoie, S.P.; Zheng, J.; Lachapelle, K. Using Eye Tracking to Examine Expert-Novice Differences during Simulated Surgical Training: A Case Study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 144, 107720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, J.Š.; Masner, J.; Benda, P.; Šimek, P.; Merunka, V. Eye Tracking, Usability, and User Experience: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peysakhovich, V.; Hurter, C. Scan Path Visualization and Comparison Using Visual Aggregation Techniques. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootjen, J.W.; Weingärtner, H.; Mayer, S. Highlighting the Challenges of Blinks in Eye Tracking for Interactive Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications, Tubingen, Germany, 30 May–2 June 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rathee, R.; Rajain, P. Role Colour Plays in Influencing Consumer Behaviour. Int. Res. J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 12, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambabu, L.; Porika, R. Packaging Strategies: Knowledge Outlook on Consumer Buying Behaviour. J. Ind.-Univ. Collab. 2020, 2, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkul, E.; Boz, H.; Bilgili, B.; Koc, E. What Colour and Light Do in Service Atmospherics: A Neuro-Marketing Perspective. In Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research; Volgger, M., Pfister, D., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 223–244. ISBN 978-1-83867-071-9. [Google Scholar]

- Puccinelli, N.M.; Chandrashekaran, R.; Grewal, D.; Suri, R. Are Men Seduced by Red? The Effect of Red Versus Black Prices on Price Perceptions. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraj, D.; Qureshi, I.H.; Singh, G.; Nazir, N.A.; Basheer, S.; Nissa, V.U. Green Marketing Practices and Green Consumer Behavior: Demographic Differences among Young Consumers. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2023, 6, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, V.; Joshi, P.; Chatterjee, K.N.; Pal Singh, G. Effect of Demographic Factors and Apparel Product Categories on Online Impulse Buying Behaviour of Apparel Consumers. Text. Leather Rev. 2023, 6, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tifferet, S.; Herstein, R. Gender Differences in Brand Commitment, Impulse Buying, and Hedonic Consumption. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2012, 21, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, M.; Wen, X. Optimal Distribution Strategy of Coupons on E-Commerce Platforms: Sufficient or Scarce? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 266, 109031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Deng, S.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y. Optimal Promotion Strategies of Online Marketplaces. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 1264–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).