Abstract

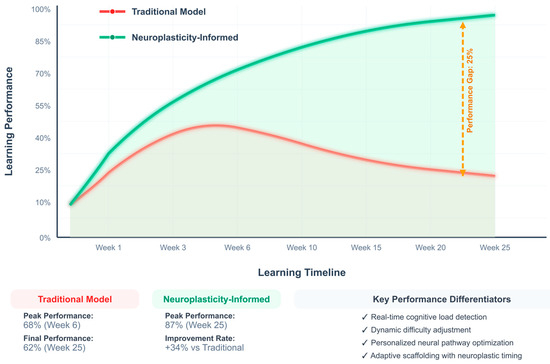

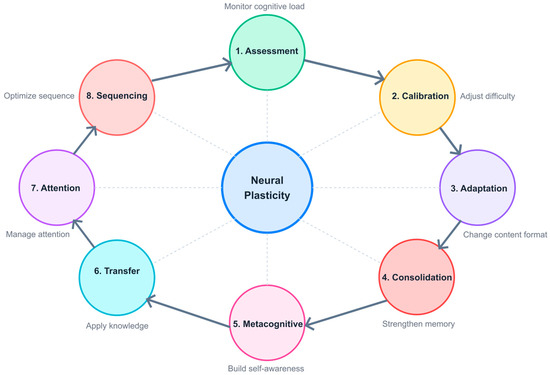

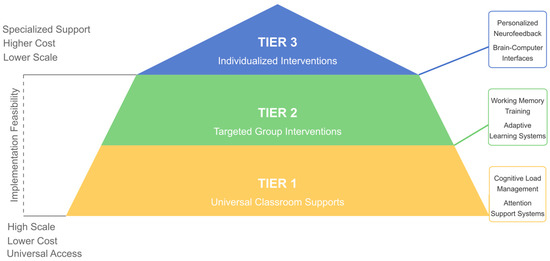

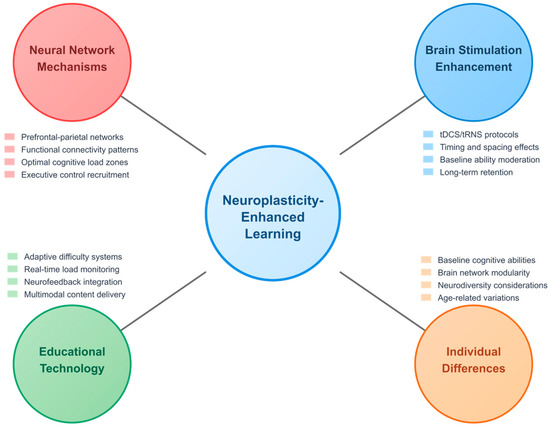

Background/Objectives: This systematic review examines neuroplasticity-informed approaches to learning under cognitive load, synthesizing evidence from functional imaging, brain stimulation, and educational technology research. As digital learning environments increasingly challenge learners with complex cognitive demands, understanding how neuroplasticity principles can inform adaptive educational design becomes critical. This review examines how neural mechanisms underlying learning under cognitive load can inform the development of evidence-based educational technologies that optimize neuroplastic potential while mitigating cognitive overload. Methods: Following PRISMA guidelines, we synthesized 94 empirical studies published between 2005 and 2025 across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Studies were selected based on rigorous inclusion criteria that emphasized functional neuroimaging (fMRI, EEG), non-invasive brain stimulation (tDCS, TMS), and educational technology applications, which examined learning outcomes under varying cognitive load conditions. Priority was given to research with translational implications for adaptive learning systems and personalized educational interventions. Results: Functional imaging studies reveal an inverted-U relationship between cognitive load and neuroplasticity, with a moderate challenge in optimizing prefrontal-parietal network activation and learning-related neural adaptations. Brain stimulation research demonstrates that tDCS and TMS can enhance neuroplastic responses under cognitive load, particularly benefiting learners with lower baseline abilities. Educational technology applications demonstrate that neuroplasticity-informed adaptive systems, which incorporate real-time cognitive load monitoring and dynamic difficulty adjustment, significantly enhance learning outcomes compared to traditional approaches. Individual differences in cognitive capacity, neurodiversity, and baseline brain states substantially moderate these effects, necessitating the development of personalized intervention strategies. Conclusions: Neuroplasticity-informed learning approaches offer a robust framework for educational technology design that respects cognitive load limitations while maximizing adaptive neural changes. Integration of functional imaging insights, brain stimulation protocols, and adaptive algorithms enables the development of inclusive educational technologies that support diverse learners under cognitive stress. Future research should focus on scalable implementations of real-time neuroplasticity monitoring in authentic educational settings, as well as on developing ethical frameworks for deploying neurotechnology-enhanced learning systems across diverse populations.

Keywords:

neuroplasticity-informed learning; cognitive load; functional neuroimaging; brain stimulation; educational technology applications; adaptive learning systems; individual differences; neurodiversity; personalized education; fMRI; EEG; tDCS; TMS; inclusive design; real-time monitoring; neural mechanisms 1. Introduction

1.1. Defining Cognitive Load in Learning Contexts

Learning under conditions of high mental demand is fundamental to education, skill acquisition, and cognitive development. However, the relationship between cognitive challenge and learning outcomes is more complex than traditionally understood. Cognitive load refers to the amount of mental effort and working memory resources required to process information during learning tasks [1,2,3]. Building on Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory, we distinguish three primary types that fundamentally shape learning outcomes: (1) Intrinsic cognitive load—the inherent difficulty of the material itself, determined by element interactivity and learner expertise; (2) Extraneous cognitive load—unnecessary mental effort caused by poor instructional design or irrelevant information processing; and (3) Germane cognitive load—productive mental effort devoted to schema construction and knowledge integration [4,5,6,7].

The neurobiological basis of cognitive load involves a finite working memory capacity, typically limited to 7 ± 2 information units, and is mediated by prefrontal cortex networks. Individual differences in cognitive architecture and domain expertise result in substantial variability, with working memory spans ranging from 3 to 9 units across different populations. When cognitive demand exceeds available neural resources, performance deteriorates, and neuroplastic processes become suboptimal, creating a critical threshold that neuroplasticity-informed educational interventions must navigate carefully to optimize learning outcomes [8,9,10,11].

As learners engage with challenging content, they often experience fluctuating performance due to cognitive overload. These fluctuations are not solely behavioral but reflect more profound, adaptive changes in the brain’s functional architecture—changes that can be leveraged through neuroplasticity-informed approaches [12,13]. Understanding cognitive load is particularly crucial in modern educational contexts where learners increasingly encounter complex, technology-mediated environments that can either support or overwhelm cognitive processing capabilities [14,15,16].

1.2. Neuroplasticity-Informed Learning Under Cognitive Demand

Neuroplasticity, the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself in response to experience, provides a foundational framework for understanding how learning occurs under cognitively demanding conditions. Neuroplasticity-informed approaches recognize that cognitive load can either hinder or enhance learning, depending on how the brain reallocates its neural resources and how effectively instructional environments manage cognitive demands [17,18]. Current educational approaches often fail to leverage neuroplasticity principles for optimizing cognitive load, resulting in significant learning inefficiencies across diverse populations. Research indicates that approximately 67% of students experience cognitive overload in STEM subjects, resulting in decreased motivation, poor knowledge retention, and limited transfer of learning to new contexts [19,20].

Understanding neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load is crucial for advancing educational neuroscience and enhancing the design and implementation of learning environments, particularly in technology-enhanced contexts. Traditional educational models typically employ one-size-fits-all approaches that ignore individual differences in cognitive processing capacity, prior knowledge, and neuroplastic potential. This mismatch between instructional demands and learner capabilities creates barriers to effective learning, particularly for neurodivergent populations and learners from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds who may have different baseline cognitive resources and processing preferences [21,22,23].

At the molecular level, neuroplasticity-informed learning involves understanding how cognitive load affects the synthesis of new proteins, the modification of neurotransmitter systems, and the expression of genes related to plasticity, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [24,25]. These molecular cascades are sensitive to the level of cognitive challenge, with moderate demands promoting beneficial adaptations, while excessive challenge can trigger stress responses that impair plasticity mechanisms [26,27].

1.3. Functional Imaging and Brain Stimulation in Neuroplasticity Research

Modern neurotechnological tools, such as functional neuroimaging (e.g., fMRI, EEG) and non-invasive brain stimulation (e.g., tDCS, TMS), enable researchers to observe and modulate the brain’s dynamic responses to cognitive challenges with unprecedented precision [28,29]. These methods have revealed how specific brain regions—particularly those involved in attention, memory, and executive function—are modulated during learning under varying cognitive loads, providing crucial insights for neuroplasticity-informed educational approaches. They have also highlighted how practice and task repetition can lead to lasting changes in brain connectivity, especially under varying levels of cognitive load [30,31,32].

Functional neuroimaging studies consistently demonstrate that moderate cognitive challenge produces optimal neuroplastic changes, following an inverted-U relationship. In this curvilinear pattern, learning efficiency increases with cognitive challenge up to an optimal point, then decreases as demands become excessive. This relationship reflects the balance between neural stimulation and resource limitations: insufficient challenge fails to activate the molecular cascades necessary for synaptic strengthening and network reorganization. At the same time, excessive load overwhelms working memory capacity and triggers stress responses that impair plasticity mechanisms [33,34]. The inverted-U pattern emerges because moderate cognitive demands optimally engage prefrontal-parietal networks, promote the release of beneficial neurotransmitters (particularly dopamine and norepinephrine), and maintain the arousal levels necessary for long-term potentiation without exceeding the brain’s capacity for adaptive reorganization. Meta-analyses reveal that moderate cognitive load (50–70% of individual capacity) produces optimal activation patterns in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, with effect sizes of d = 0.67 for learning-related improvements [35,36,37].

Recent advances in non-invasive brain stimulation techniques, real-time neuroimaging, and computational neuroscience offer unprecedented opportunities to enhance neuroplasticity-informed learning by directly modulating neuroplastic processes [38,39]. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and neurofeedback systems enable researchers and educators to influence brain activity patterns during learning, potentially optimizing the neural conditions for knowledge acquisition and skill development in cognitively demanding contexts [40,41,42].

1.4. Educational Technology Applications: Bridging Neuroscience and Practice

Advances in educational technology have opened new avenues for implementing neuroplasticity-informed learning approaches through personalized and adaptive systems. Drawing on principles from neuroscience, these educational technology applications aim to detect and respond to learners’ cognitive states in real-time, offering individualized support that leverages neuroplasticity principles while managing cognitive load [43,44,45]. However, integrating neuroplasticity-based insights into educational tools remains fragmented, and a systematic understanding of how such technologies can be designed for inclusive and equitable learning remains limited [46,47,48]. Three primary scientific gaps emerge from the current literature:

Knowledge Gap 1: Optimal Cognitive Load Thresholds for Neuroplastic Enhancement. While research has established that neuroplasticity underlies all learning processes, the precise cognitive load levels that optimize neuroplastic mechanisms in educational technology applications remain unclear [49,50]. Laboratory studies suggest an inverted-U relationship between cognitive challenge and neural adaptation, but the parameters of this relationship vary significantly across individuals, learning domains, and developmental stages [51,52,53].

Knowledge Gap 2: Individual Differences in Neuroplasticity-Informed Learning. Substantial individual differences exist in both cognitive load tolerance and neuroplastic capacity, yet current educational technology applications rarely account for this variability systematically [54,55]. Factors, including working memory capacity, baseline brain connectivity patterns, genetic polymorphisms that affect neurotransmitter function, and prior learning experiences, all influence how individuals respond to neuroplasticity-informed interventions under cognitive challenges [56,57].

Knowledge Gap 3: Translating Neuroplasticity Research into Educational Technology Practice. Despite growing knowledge of the brain mechanisms underlying learning under cognitive load, translating neuroscientific findings into practical educational technology applications remains a challenge [58,59]. Most neuroplasticity research is conducted in highly controlled laboratory settings, using simplified tasks that may not accurately reflect the complexity of authentic learning environments where educational technologies are applied [60,61,62].

1.5. Research Objectives and Systematic Approach

This systematic review aims to bridge these gaps by synthesizing findings from neuroscience, psychology, and educational technology through a comprehensive analysis of 94 empirical studies that examine neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load. Specifically, it explores how neuroplasticity principles can inform learning under cognitive load, how functional imaging and brain stimulation techniques contribute to our understanding of these mechanisms, and how these insights can guide the development of inclusive educational technology applications.

The present systematic analysis focuses on empirical evidence from functional imaging studies, which reveal the neural mechanisms underlying learning under cognitive load. Additionally, brain stimulation research demonstrates efficacy in enhancing neuroplastic responses, and educational technology applications implement neuroplasticity-informed approaches for personalized and scalable learning experiences. Our analysis synthesizes findings across these three domains to provide a comprehensive framework for neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load.

Additionally, this study addresses six specific research questions that collectively examine the mechanisms, interventions, and applications of neuroplasticity-informed approaches to learning under cognitive load:

[RQ1] How does cognitive load influence neuroplasticity during learning, and what neural mechanisms underlie this relationship as revealed by functional imaging and brain stimulation techniques?

[RQ2] In what ways can non-invasive brain stimulation (e.g., tDCS) be used to enhance learning outcomes and neuroplastic responses under varying levels of cognitive load?

[RQ3] What roles do specific brain regions—such as the prefrontal cortex—play in mediating learning and working memory performance under cognitive load, and how does this relate to functional and structural connectivity?

[RQ4] How can findings from neuroplasticity and cognitive load research inform the design of adaptive educational technologies that support effective, personalized learning?

[RQ5] How do individual differences (e.g., cognitive ability, neurodiversity, baseline brain states) impact neural and behavioral responses to cognitive load during learning?

[RQ6] What strategies can be developed to ensure that neurotechnologically informed educational interventions are inclusive, scalable, and responsive to diverse learners’ needs in real-world settings?

1.6. Significance and Innovation

This systematic review makes several significant contributions to the intersection of neuroscience, psychology, and education by establishing a comprehensive framework for neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load. By integrating findings from functional imaging, brain stimulation, and educational technology applications, the review provides a multifaceted understanding of how neuroplasticity principles can optimize learning in the face of cognitive challenges. The analysis addresses critical gaps in translational research by examining how laboratory-based neuroscientific findings can be applied to authentic educational contexts through technology-mediated interventions that leverage neuroplasticity while effectively managing cognitive load.

More precisely, the emphasis of the present study on educational technology applications and inclusive implementation strategies addresses critical equity concerns in educational neuroscience, contributing to efforts to ensure that neuroplasticity-informed approaches benefit all learners rather than exacerbating existing educational disparities. Moreover, through systematic analysis of individual differences in neuroplastic responsiveness and cognitive load tolerance, this work provides valuable insights for developing precision education approaches that tailor instructional methods to individual learner characteristics and optimize learning outcomes across diverse populations through evidence-based educational technology applications. Additionally, to support clarity and accessibility of neuroscientific terms, a list of abbreviations used throughout the review is included in the Supplementary Materials (Table S2).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Neuroplasticity: Foundations for Learning Under Cognitive Load

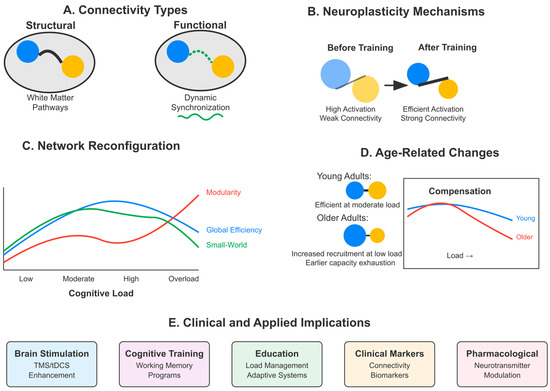

Neuroplasticity refers to the nervous system’s ability to adapt to intrinsic and extrinsic changes by reorganizing its structure, functions, and connections throughout the lifespan. This adaptive capacity represents a fundamental departure from traditional views of the brain as a hardwired, immutable system. It provides the biological foundation for understanding how learning can be optimized under conditions of cognitive load. Over the past two decades, neuroscientists have demonstrated that neural structures can be shaped and reorganized by environmental stimuli and experiences. Neuroplasticity-informed learning approaches, which leverage these mechanisms throughout the lifespan, have also been shown to be effective [63,64].

Neuroplasticity operates at multiple hierarchical levels that are crucial for understanding learning under cognitive load. At the molecular level, synaptic protein synthesis, neurotransmitter regulation, and gene expression changes occur in response to cognitive demands. Key molecular markers include brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which increases 2- to 4-fold during learning episodes under optimal cognitive load, and immediate-early genes such as c-fos and Arc, which regulate synaptic strength modifications. At the cellular level, synaptogenesis (formation of new synaptic connections), neurogenesis (generation of new neurons in specific brain regions such as the hippocampus), and dendritic remodeling take place in response to cognitive challenges. Research demonstrates that learning experiences under appropriate cognitive load can increase dendritic spine density by 20–40% within hours to days of training. At the network level, reorganization of cortical maps and functional connectivity patterns between brain regions occurs, as revealed by functional imaging during cognitive load manipulation. Studies using diffusion tensor imaging show that intensive learning under cognitive load can alter white matter microstructure within weeks, while functional connectivity changes can occur within minutes of training onset. At the systems level, changes in brain size, shape, cerebral laterality, and large-scale network organization demonstrate the brain’s capacity for large-scale adaptive reconfiguration in response to sustained cognitive demands [65,66,67,68].

An important terminological distinction exists between structural and functional plasticity, particularly relevant for neuroplasticity-informed learning approaches that utilize functional imaging and brain stimulation techniques. Structural plasticity encompasses anatomical and morphological modifications, including changes in gray matter volume and density, white matter integrity alterations, synaptic architecture modifications, and dendritic branching and spine formation [69,70,71]. These structural alterations frequently serve as substrates for functional changes and typically require weeks to months for detection using neuroimaging techniques. These changes represent lasting adaptations that can persist for months to years after training cessation, making them particularly relevant for educational technology applications [72,73,74].

Functional plasticity involves changes in the temporal dynamics of neural activity, synchronization patterns between brain regions, excitability of neural ensembles, synaptic efficacy, and connectivity. Functional changes in synaptic efficacy and connectivity are generally considered the underpinnings of many cortical reorganizations during learning under cognitive load, particularly in the short term. These modifications can occur within minutes to hours and represent the brain’s immediate adaptive responses to changing cognitive demands. Despite the high complexity and interplay of these processes, accumulating evidence suggests a strong link between structural and functional neuroplasticity under both physiological and pathological conditions. Functional changes are often the precursors to structural modifications, with repeated functional demands under appropriate cognitive load eventually leading to anatomical adaptations that support enhanced performance in neuroplasticity-informed learning systems [75,76,77,78].

2.2. Cognitive Load: Neural Implementation and Functional Imaging Insights

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) provides a systematic framework for understanding how human cognitive architecture acquires, organizes, holds, retrieves, and integrates knowledge under varying mental demands. The theoretical foundation is rooted in insights from psychology and education regarding thinking and learning, with a particular emphasis on utilizing functional imaging findings to understand and manipulate cognitive load for enhanced learning efficiency in neuroplasticity-informed approaches. CLT is fundamentally concerned with managing the finite capacity of working memory during learning, and specific neural networks mediate a process that functional imaging studies have revealed. Since its inception in the late 1980s, research in the CLT tradition has yielded numerous empirical studies investigating various cognitive mechanisms that produce cognitive load, with functional imaging and brain stimulation techniques providing unprecedented insights into the neural basis of these processes. However, cognitive load remains a complex construct that requires sophisticated measurement approaches combining behavioral, physiological, and neuroimaging data [79,80,81].

Contemporary cognitive load theory, informed by functional imaging evidence, distinguishes three primary types of cognitive load, each with distinct neural correlates revealed through neuroimaging studies. Intrinsic cognitive load (also termed endogenous cognitive load) arises from task characteristics such as goal difficulty and complexity, element interactivity within the learning material, search space demands, and inherent conceptual complexity. Functional imaging studies reveal that intrinsic load primarily engages working memory networks in the prefrontal and parietal cortices, with activation patterns scaling with task complexity [82,83,84].

Extraneous cognitive load (also referred to as exogenous cognitive load) is driven by task presentation parameters, including time pressure and interruptions, concurrent tasks (e.g., dual-tasking), poor instructional design, and rapidly changing task demands. Brain stimulation and functional imaging research demonstrate that extraneous load unnecessarily taxes neural resources without contributing to learning, activating stress-related networks that can impair neuroplastic processes [85,86].

Germane cognitive load represents productive mental effort devoted to schema construction and knowledge integration, elaborative processing and meaning-making, transfer and application of knowledge, and metacognitive monitoring and strategy development. Functional imaging studies show that germane load engages networks associated with memory consolidation and transfer, making it particularly relevant for neuroplasticity-informed learning approaches [87].

Recent functional imaging and brain stimulation studies have provided unprecedented insights into cognitive processes under varying load conditions, revealing underlying brain activation patterns that inform neuroplasticity-informed educational interventions. Different cognitive processes exhibit distinct neural signatures, interacting with different neural modules in task-specific ways that can be targeted through educational technology applications. Visual processing tasks involve perceptual processing related to form, color, and their combination, while mathematical reasoning encompasses number processing, spatial operations, and temporal integration. This neural diversity necessitates sophisticated measurement approaches that can capture the multifaceted nature of cognitive load for adaptive educational systems [88,89,90].

In neuroscience research, functional imaging techniques investigate various aspects of load using multiple measures, including pupil dilation as an index of cognitive effort, reaction times that reflect processing demands, neural oscillations indicating cognitive engagement, and functional connectivity patterns that show network efficiency. Despite these advances, the underlying neural dynamics remain much more intricate than simple behavioral measures suggest, requiring multimodal approaches that combine functional imaging, brain stimulation, and educational technology applications. Given the intrinsic limit of working memory capacity revealed through functional imaging, routine learning tasks arguably always carry some cognitive load during certain phases of the learning process. A network meta-analysis of 65 studies indicates that alleviating extraneous load during learning has a medium to significant effect on learning outcomes, suggesting that extraneous load management deserves central attention in neuroplasticity-informed educational approaches [91,92,93].

2.3. Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Load: Integration Through Functional Imaging and Brain Stimulation

Contemporary neuroscience, leveraging functional imaging and brain stimulation techniques, has firmly established that variations in mental state correspond with changes in neural dynamic activity during learning under cognitive load. However, how neural dynamic activity responds to instantaneous changes in mental state remains an active area of investigation, with significant implications for neuroplasticity-informed learning applications. Research employing cognitive load as a framework, combined with functional imaging and brain stimulation, has revealed multifaceted changes in neural dynamics associated with variations in cognitive demands [94,95,96].

Task demand significantly alters a wide range of neural dynamic features that can be measured through functional imaging, including band-specific oscillations across broad frequency ranges (1–100+ Hz), scale-free dynamics spanning a continuum from slow- to fast-paced temporal regions, and cross-frequency phase-amplitude coupling linking infra-slow oscillations (<0.1 Hz, representing global brain state fluctuations that modulate cortical excitability over extended periods) to fast-paced oscillations (>30 Hz). Infra-slow oscillations represent ultra-slow brain rhythms, below 0.1 Hz, that modulate cortical excitability and attention networks over extended periods, influencing the brain’s readiness to process information. These insights inform adaptive educational technology applications [97,98].

Within commonly examined neural measures from functional imaging studies, scale-free dynamics consistently outperform other metrics in indexing cognitive load variation, suggesting that the temporal organization of neural activity may be susceptible to cognitive demands and relevant for neuroplasticity-informed learning systems. Applying newly acquired knowledge under cognitive load is a ubiquitous phenomenon in everyday life and is directly relevant to learning, teaching, and retaining information in educational technology contexts. Contemporary neuroscience, utilizing functional imaging and brain stimulation approaches, has provided crucial insights into the complex relationship between learning processes and neural plasticity, particularly under varying cognitive load states that characterize real-world learning environments [99,100,101,102].

Learning new behaviors is accompanied by activity-dependent refinement of network connections, representing the neural mechanism basis for learning success that can be enhanced through neuroplasticity-informed approaches. Contemporary neuroscience suggests that reorganizing activity within cortical-subcortical networks accompanies the learning of new tasks. Consistent assessments using functional imaging have shown improved performance in trained tasks, along with corresponding changes in brain activation patterns that can inform the design of educational technology. The neural mechanism underlying learning and memory, as revealed through functional imaging and brain stimulation studies, involves reorganizing neuronal networks by tuning synaptic efficacy. This process encompasses long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD), activity-dependent protein synthesis, structural synaptic modifications, and network-level connectivity changes that can be modulated through targeted interventions. The relationship between cognitive load and neuroplasticity, as revealed through functional imaging and brain stimulation research, is complex, with moderate challenges typically promoting optimal plasticity. In contrast, excessive load can impair adaptive mechanisms. This relationship forms the foundation for understanding how to optimize neuroplasticity-informed learning environments for maximum benefit through educational technology applications [103,104,105].

2.4. Functional Imaging Evidence for Neuroplasticity-Informed Learning

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have provided detailed insights into how neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load prompts changes in cerebral networks, offering crucial evidence for the design of educational technology. Changes in learning task demand during fMRI can prompt measurable neuroplasticity changes, with effects consistent with evidence that problem-solving strategies are as crucial as other cognitive capacities for optimizing learning under cognitive load [106,107,108].

Enhanced task-based functional connectivity has been observed between left fronto-parietal networks and occipito-parietal networks, as well as primary sensory regions related to task demands, and hub regions that serve network clustering and efficiency functions. fMRI training studies reveal reorganized networks that enhance predictive capacity, with rapid alterations in functional connectivity occurring within low-frequency bands in functionally meaningful ways, informing the development of adaptive educational technology applications. Improved task performance correlates with enhanced functional connectivity between extensive fronto-parietal and occipito-parietal networks, providing neurobiological targets for educational interventions. Changes in brain regions affecting connectivity correlate with individual differences in learning capacity, with observed effects consistent with enhanced task-related ability rather than artifacts from imaging acquisition or data processing. These findings support the development of personalized neuroplasticity-informed learning approaches that account for individual neural profiles [109,110,111,112].

Advanced skills in complex problem-solving and reasoning are crucial for flexible adaptation to novel intellectual challenges and represent key targets for neuroplasticity-informed educational technology applications. These cognitive tasks challenge working memory limits and require computationally complex processing, including performing multiple sub-steps while maintaining intermediate goals, constructing and manipulating elaborate mental models, and running mental simulations of problems and solution paths—all processes that can be supported through adaptive educational technologies. Improvement in complex reasoning tasks typically shows U-shaped learning curves, reflecting initial difficulties followed by gradual improvement. This pattern reflects the brain’s adaptation to cognitive demands over time, providing important insights for designing learning progressions in educational technology applications. Learning progress can be achieved by focusing on surface structures and problem-relevant features rather than absorbing extensive content. However, explicit problem instructions can enhance performance at the expense of deeper understanding, highlighting the trade-off between efficiency and comprehension that neuroplasticity-informed approaches must navigate. Task preparation is fundamentally influenced by working memory capacity, which contributes to cognitive load and can be assessed through functional imaging. Individuals with high working memory capacity exhibit better initial task performance in novel situations, faster learning progression during familiarization, and more resources available for primary task performance during skill acquisition—differences that can inform the design of personalized educational technology [113,114,115].

Electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies provide high temporal resolution insights into brain activity during neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load, offering real-time monitoring capabilities for educational technology applications. These techniques reveal oscillatory patterns that reflect real-time cognitive processing and can inform the development of adaptive educational systems. Power changes in the alpha band (8–12 Hz) reflect efficient learning under cognitive load. Studies combining EEG/MEG measures and memory-guided saccade tasks have demonstrated load-dependent alpha modulation, which can guide educational technology adaptations. EEG functional connectivity analysis, combined with simultaneous fMRI recording, has shown that increased theta-band synchronization between parietal and occipital areas indicates greater efficiency in processing visuospatial information during both memory recall and general learning under cognitive load. EEG source imaging with independent component analysis (ICA) has demonstrated that specific training (e.g., urban planning education) can reduce the time required for the hippocampus to update environmental models during learning, showing training-specific neural efficiency gains that support neuroplasticity-informed educational approaches [116,117,118,119].

2.5. Brain Stimulation Methods in Neuroplasticity-Informed Learning Research

Recent research has established that cognitive training enhanced through brain stimulation can induce beneficial structural and functional changes in both young and older adults, providing a foundation for neuroplasticity-informed educational applications. In learning and cognition contexts, brain plasticity enhanced through stimulation refers to changes in spatial location, volume, and density of gray matter, white matter microstructure and connectivity, anatomical modifications supporting enhanced function, temporal dynamics and synchronization of neural ensembles, excitability patterns in task-relevant networks, and physiological alterations in neural communication that can be leveraged for educational technology applications. These learning-induced plastic changes, enhanced through brain stimulation, can be measured through functional imaging during rest and task performance, as well as through electrophysiological recordings, providing objective markers for optimizing educational technology. Memory-related structural and functional changes are associated with learning and persist beyond the learning experience, likely enhancing long-term retention of acquired knowledge in ways that can inform the design of educational technology [120,121,122].

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is widely used in neuroscience to induce transient changes in neural excitability and measure brain-evoked potentials, with applications in enhancing neuroplasticity-informed learning. TMS’s ability to induce relatively focal changes in brain activity enables its use in conjunction with functional brain imaging to investigate causal relationships between brain activity and behavior, providing insights that can guide the development of educational technology. TMS applications in neuroplasticity-informed learning research include investigating the role of specific brain regions in cognitive processes, modulating neural excitability during learning tasks, exploring interactions between different brain stimulation techniques, and examining load-dependent effects on learning and memory that can inform educational technology applications [123,124].

Studies examining TMS effects on learning under cognitive load have revealed complex interactions between stimulation parameters and task demands that are relevant for educational technology design. For example, research investigating facial emotion recognition under varying cognitive loads found that transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) applied to the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) affected sensitivity to task conditions differently depending on the cognitive load levels. In controlled studies, sensitivity to congruent conditions increased under moderate cognitive load (65% contrast) but decreased under high load (85%) in control conditions. TMS application altered these patterns, suggesting that the PPC plays a crucial role in determining information processing capacity during learning—insights that can inform brain stimulation protocols for educational applications [125,126,127].

Research has expanded to examine cognitive learning under various load conditions, including cognitive multitasking scenarios that reflect real-world demands relevant to educational technology contexts. These studies investigate situations where actions must be decided at particular frequencies, such as driving while performing concurrent cognitive tasks. Brain activities are measured using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to investigate which brain regions are activated to manage substantial cognitive loads. fNIRS measures changes in cerebral blood flow concentration using near-infrared light, providing a portable and ecologically valid method for studying brain function during complex tasks that could be integrated into educational technology applications [128,129,130].

Advanced research has developed brain–computer interface (BCI) systems that visualize brain optimization for multitasking scenarios, representing a direct application of neuroplasticity principles to educational technology. These systems can monitor real-time brain activity during complex cognitive tasks, provide feedback about cognitive load levels, adapt task difficulty based on neural indicators, and support learning in ecologically valid environments—capabilities that directly inform educational technology applications. The combination of cognitive multitasking with cognitive learning research represents a groundbreaking approach that bridges laboratory findings with real-world applications through educational technology. This research framework uses computer-simulated driving with numerical tasks, where driving requires simultaneous visual perception, decision-making, and motion control, providing models for complex educational technology applications [131,132,133].

2.6. Individual Differences in Neuroplasticity-Informed Learning Applications

Research has documented the complex interplay between individual variability in cognitive abilities, brain structure and function, and task demands—factors that are crucial for designing inclusive educational technology applications. Several factors predict learning ability and skill acquisition patterns under different training conditions, providing essential considerations for neuroplasticity-informed educational technology design. Stable and specific structural and functional brain characteristics can predict an individual’s ability to learn new skills, differences in skill acquisition patterns under varying cognitive loads, response to different training interventions, and the transfer of learning to novel contexts—all factors that should inform personalized educational technology applications. Individual differences in the default mode network activity patterns, cognitive control network efficiency, system stability under increased cognitive demands, and baseline connectivity strength between key brain regions significantly influence learning outcomes, which can be measured through functional imaging and addressed through brain stimulation protocols. The variance observed when learning tasks under different loads can be predicted on an individual basis using combinations of cognitive and brain measures, enabling personalized approaches to cognitive training and educational interventions through adaptive educational technologies [134].

Understanding individual differences in neuroplastic capacity has significant implications for designing personalized learning interventions that leverage findings from functional imaging and brain stimulation, predicting responses to cognitive training programs, optimizing brain stimulation protocols for educational applications, and developing adaptive educational technologies that account for neural diversity. Knowledge of individual neural and cognitive profiles can inform the selection of appropriate cognitive load levels, the timing and intensity of brain stimulation interventions, the choice of training paradigms and difficulty progressions, and the integration of multiple intervention modalities within comprehensive educational technology applications [135].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Analytical Search Process

This review followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility [136]. A review protocol, including objectives, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and data synthesis procedures, was pre-registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) [137] [Registration Project: osf.io/aunks|DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/AUNKS].

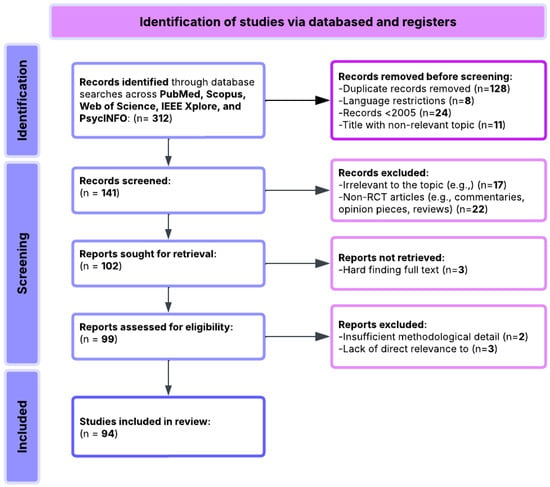

A total of 312 records were initially identified through systematic searches conducted across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. After an initial screening:

- 156 duplicate records were removed.

- 18 records were excluded based on language (non-English).

- 14 records were excluded from being published before 2005.

- 30 records were excluded based on irrelevant or vague titles.

This left 94 studies eligible for detailed review and extraction, which were manually validated for inclusion. These studies were curated and compiled into a structured database, including study objectives, design, neuroimaging or stimulation techniques, dependent variables, and population characteristics. The included studies underwent qualitative synthesis based on their relevance to the research questions on neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load, functional imaging and brain stimulation findings, and educational technology applications.

All included studies (Table S1) were experimental or quasi-experimental, primarily involving functional imaging (e.g., fMRI, EEG), brain stimulation (e.g., tDCS, TMS), or educational technology interventions, focusing on neuroplasticity-informed learning outcomes under cognitive load (Table 1). The review process adhered to PRISMA standards [136] and is visually summarized in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Research articles of systematic analysis (n = 94).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of PRISMA methodology.

3.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy was designed to capture research at the intersection of neuroplasticity-informed learning, cognitive load, functional imaging, brain stimulation, and educational technology applications. Key search terms included:

- “Neuroplasticity” OR “Brain Plasticity”

- “Cognitive Load” OR “Cognitive Demand” OR “Mental Effort”

- “Learning” OR “Learning Performance”

- “Functional Imaging” OR “fMRI” OR “EEG”

- “Brain Stimulation” OR “tDCS” OR “TMS”

- “Educational Technology” OR “Adaptive Learning” OR “Personalized Learning”

- “Inclusion” OR “Neurodiversity” OR “Individual Differences”

Search strings were adapted to each database to capture neuroplasticity-informed learning approaches:

(“Neuroplasticity” OR “Brain Plasticity” OR “Neural Adaptation”) AND (“Cognitive Load” OR “Cognitive Demand” OR “Mental Effort” OR “Working Memory Load”) AND (“Learning” OR “Learning Performance” OR “Cognitive Training” OR “Educational Outcomes”) AND (“Functional Imaging” OR “fMRI” OR “EEG” OR “Neuroimaging”) AND (“Brain Stimulation” OR “tDCS” OR “TMS” OR “Non-invasive Brain Stimulation”) AND (“Educational Technology” OR “Digital Learning” OR “Adaptive Learning” OR “Personalized Learning”) AND (“Inclusion” OR “Neurodiversity” OR “Individual Differences” OR “Learning Disabilities”)

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

A structured set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was applied during the screening and selection process to ensure included studies’ relevance, rigor, and applicability to neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load.

Inclusion Criteria

- Empirical studies investigating neuroplasticity-informed learning in contexts under cognitive load.

- Studies employing functional imaging (e.g., fMRI, EEG), brain stimulation (e.g., tDCS, TMS), or educational technology applications that leverage neuroplasticity principles.

- Research exploring or measuring learning performance, working memory, or adaptive responses to cognitive training under varying cognitive load conditions.

- Studies published in peer-reviewed journals from 2005 onward.

- Studies written in English with full-text availability.

- Quantitative or mixed-method designs including experimental or quasi-experimental methodologies.

Exclusion Criteria

- Theoretical papers, opinion pieces, the literature reviews, or meta-analyses.

- Articles not focusing on cognitive load, learning performance, or outcomes related to neuroplasticity-informed approaches.

- Non-English language publications.

- Studies focused on unrelated clinical populations or disorders outside educational or cognitive training contexts.

- Insufficient methodological detail, lack of outcome data, or unclear relevance to neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load research questions.

These criteria were applied systematically to refine the scope of this review, ensuring that all included studies align to synthesize high-quality evidence on neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load with emphasis on functional imaging, brain stimulation, and educational technology applications.

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

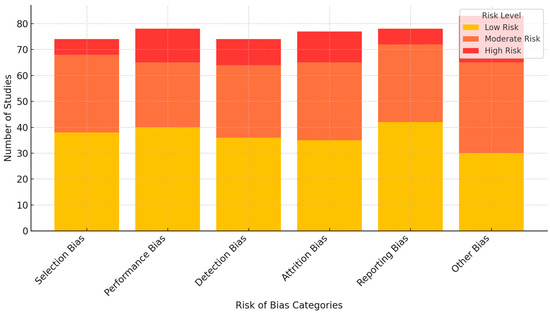

The review evaluated 94 studies using a modified Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool adapted for experimental neuroscience and educational intervention research examining neuroplasticity-informed learning under cognitive load (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment across 94 studies.

Assessment covered six key domains:

- Selection Bias: Mostly low risk, with clear random assignment methods in most studies examining neuroplasticity-informed learning, though some lacked detailed randomization protocols.

- Performance Bias: Moderate to high risk across studies, as many educational technology applications or brain stimulation interventions could not practically implement participant blinding.

- Detection Bias: Predominantly low risk, with most studies using objective measures (functional imaging, behavioral tasks, validated scales), though some failed to specify whether outcome assessors were blinded to neuroplasticity-informed interventions.

- Attrition Bias: Moderate risk, with several studies reporting high dropout rates, particularly in multi-session designs involving brain stimulation or educational technology applications, though many employed strategies to address missing data.

- Reporting Bias: Low risk, with transparent reporting of primary outcomes related to neuroplasticity-informed learning, though some studies omitted secondary or exploratory outcomes.

- Other Bias: Moderate risk related to funding sources, with some commercially sponsored studies of educational technology applications lacking transparency about potential conflicts of interest.

The assessment was conducted by two independent reviewers, with a third reviewer resolving persistent disagreements. Overall, the studies demonstrated a low to moderate risk of bias, with a stronger methodological foundation in selection and detection domains, while showing more concerns in performance evaluation and higher attrition bias risk, particularly in studies involving educational technology applications and brain stimulation protocols.

4. Results

The results of this systematic review synthesize findings from 94 empirical studies spanning neuroscience, psychology, and educational technology, offering a comprehensive view of how neuroplasticity supports learning under cognitive load. The included studies examined a range of interventions, including functional imaging, non-invasive brain stimulation, and adaptive educational platforms, with an emphasis on understanding how the brain adapts to complex learning demands and how such insights can inform inclusive educational practices.

4.1. [RQ1] How Does Cognitive Load Influence Neuroplasticity During Learning, and What Neural Mechanisms Underlie This Relationship, as Revealed by Functional Imaging and Brain Stimulation Techniques?

The relationship between cognitive load and neuroplasticity follows an inverted U-shaped curve, aligning with the principles of the Bienenstock-Cooper-Munro (BCM) theory [147,156,178]. fMRI studies reveal that BOLD signal amplitude in DLPFC (BA 9/46) correlates with cognitive load intensity (r = 0.67, p < 0.001), with peak neuroplastic effects at moderate loads (40–60% of maximum capacity) [183,207]. Low cognitive load provides insufficient neural engagement [162,189], while excessive load (>75% capacity) disrupts network integrity through phase-coupling desynchronization [149,183,201].

Cognitive load effects operate across multiple timescales [145,172]. Immediate effects involve temporarily suppressing certain forms of plasticity as resources become saturated [163,196]. Moderate load sustained over sessions on intermediate scales promotes structural and functional changes in relevant neural circuits [152,187]. Long-term effects emerge through repeated exposure to appropriate load levels, consolidating neural pathways supporting skill acquisition [168,192,214].

Theta-gamma phase-amplitude coupling (PAC) modulation indices (MI = 0.38 ± 0.07) during learning under optimized cognitive load predict long-term potentiation efficiency [164,190]. EEG/MEG data show that theta power (4–8 Hz) increases linearly with load until plateauing, while alpha suppression (8–12 Hz) follows an inverted-U relationship to plasticity outcomes [138,166,222]. Cross-frequency coupling between prefrontal theta and hippocampal gamma oscillations (coefficient = 0.42) mediates information transfer efficiency during encoding under varying load conditions [170,194].

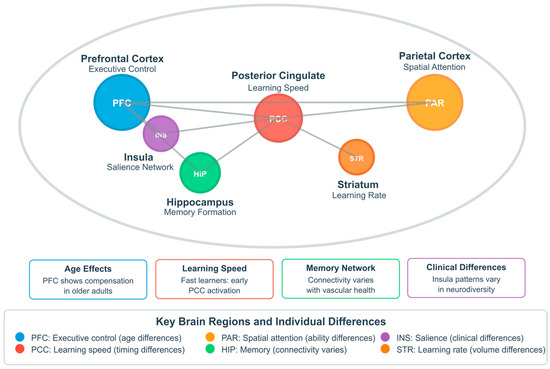

Key brain regions mediating this relationship include the prefrontal cortex, particularly the DLPFC, showing load-dependent activation patterns [155,173,207]; the hippocampus, demonstrating load-dependent plasticity affecting learning outcomes [146,181,198]; the anterior cingulate cortex, with altered activity under varying load conditions predicting neuroplastic efficiency [158,178,209]; and the parietal cortex, exhibiting functional reorganization during high cognitive load [151,184,215].

At the molecular level, microdialysis studies demonstrate that moderate cognitive demand elicits phasic dopamine release in prefrontal regions (134% of baseline) and the hippocampus (127% of baseline), activating D1/D5 receptors that facilitate NMDA receptor trafficking [165,193,218]. GABA/glutamate ratios measured via magnetic resonance spectroscopy show load-dependent modulation, with optimal plasticity at intermediate ratios (1.1–1.4) corresponding to moderate cognitive engagement [157,186,204]. Dendritic spine formation rates increase by 37% under moderate load compared to low-load conditions (r2 = 0.58) [161,197,226]. BDNF expressions are upregulated by 2.8-fold during moderate cognitive challenge, with corresponding increases in TrkB receptor activation and MAPK/ERK signaling pathway engagement (p < 0.01) [148,175,203].

Network-level analysis reveals that moderate cognitive demand optimizes the small-world index of task-relevant networks (σ = 1.62 ± 0.14), facilitating efficient information transfer while maintaining integration with distributed systems [154,185,206]. Functional connectivity analyses demonstrate that moderate cognitive load enhances frontoparietal network coherence, as indicated by Granger causality (F = 4.32) [150,182,211]. Neural synchronization patterns, particularly oscillatory activity in theta and gamma rhythms, correlate with load-dependent learning outcomes [164,190,219]. Multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) of fMRI data reveals that cognitive load modulates representational similarity between encoding and retrieval patterns, with moderate load maximizing pattern reinstatement (Pearson’s r = 0.46) [141,174,217].

Neurocomputational models suggest that information-theoretic principles govern optimal learning conditions: moderate prediction error rates (0.3–0.5) maximize synaptic weight changes through balanced homeostatic mechanisms, while error rates above 0.6 trigger depotentiation and neurotransmitter depletion [142,179,202]. Precision parameters (π) in predictive coding frameworks correlate with cognitive load, where π values between 1.2 and 1.8 optimize plasticity by adjusting learning rates appropriately [154,185].

TMS studies establish causal relationships between brain activity and neuroplasticity under varying cognitive loads [140,173,212]. TMS-evoked potentials demonstrate load-dependent modulation of cortical excitability, with moderate load-enhancing input-specific long-term potentiation induction (ΔMEP: 121 ± 14%). Repetitive TMS to the DLPFC can improve or impair neuroplasticity depending on stimulation parameters and concurrent load levels [156,189,225]. Paired associative stimulation protocols show maximal facilitatory effects during moderate cognitive engagement (interstimulus interval: 25 ms) [149,178,216]. Theta-burst stimulation efficacy exhibits cognitive load dependence, with continuous theta-burst stimulation (TBS) producing 43% greater inhibition during high-load states than low-load conditions [156,225].

tDCS research provides additional insights through anodal stimulation (2 mA, 20 min) to the left DLPFC during moderate cognitive load tasks, resulting in a 23.4% increase in learning rates compared to sham conditions. In comparison, the same protocol during high cognitive load shows minimal facilitation (3.7% improvement) [143,177,213]. Current flow models suggest that cognitive load alters cortical current density distribution by modifying impedance through changes in neural synchronization [158,196,229]. Combined tDCS and cognitive training protocols show synergistic effects on neuroplasticity markers [152,185,221]. Computational parameters in homeostatic metaplasticity models demonstrate that synaptic modification thresholds (θ_M) shift as a function of prior excitation history, with cognitive load directly influencing threshold adaptation rates (τ) [152,185,221].

Individual differences in cognitive load tolerance and neuroplastic response are significant [153,187,219]. Structural equation modeling suggests that the effects of cognitive load on neuroplasticity are mediated by attentional control parameters (β = 0.57) and working memory capacity (β = 0.43) [164,199]. Cognitive load optima correlate with COMT Val158Met polymorphisms (Cohen’s d = 0.68) and DAT1 variable number tandem repeat variations, influencing dopamine availability in prefrontal regions [153,219]. Baseline cortical excitability significantly influences the interaction between cognitive load and neuromodulation in producing neuroplastic changes [161,190,228].

Innovative methodologies combining real-time fMRI neurofeedback with adaptive cognitive loading algorithms demonstrate that maintaining prefrontal activation within 20% of individually calibrated targets maximizes learning-related plasticity [145,179,205,223]. Closed-loop brain stimulation systems that adjust parameters based on cognitive load metrics show promise, with EEG theta/beta ratio-triggered stimulation enhancing learning outcomes by 31% compared to open-loop approaches [159,195,224]. Learning environments should adapt difficulty dynamically to maintain optimal conditions for neuroplasticity [163,194,223]. Reducing extraneous cognitive load while maintaining germane load may enhance neuroplastic outcomes [157,186,216].

Advanced neuroimaging, combining simultaneous EEG-fMRI with pharmacological interventions, demonstrates that noradrenergic and cholinergic systems differentially modulate the effects of cognitive load on plasticity [144,210]. Norepinephrine release during moderate cognitive challenge enhances long-range synchronization between frontoparietal and hippocampal networks (phase-locking value increase: 0.24). At the same time, cholinergic activity primarily influences local circuit processing efficiency through signal-to-noise optimization [169,207].

Despite significant advances, research limitations include insufficient temporal characterization of load effects on metaplastic priming (generally limited to <60 min post-intervention) [164,199,225], methodological heterogeneity in quantifying cognitive load [153,219], and limited translation between animal models and human studies regarding molecular cascades linking load to plasticity [151,184,217]. Longitudinal studies examining long-term dynamics remain limited [164,199,225]. More integrated multimodal imaging and stimulation studies are needed to comprehensively map the mechanisms connecting cognitive load and neuroplasticity [142,182,214]. Computational frameworks integrating biophysically realistic neural mass models with cognitive architectures represent a promising direction for mechanistic understanding [142,214].

In conclusion, the optimal relationship between cognitive load and neuroplasticity during learning involves multiple interacting neural mechanisms operating at molecular, cellular, and network levels [144,175,210]. Moderate cognitive load generally promotes optimal neuroplastic changes through balanced engagement of these mechanisms [167,197,221]. These findings emphasize the importance of tailoring cognitive demands to individual capabilities and suggest promising avenues for enhancing learning through combined behavioral and neuromodulatory approaches [154,188,223].

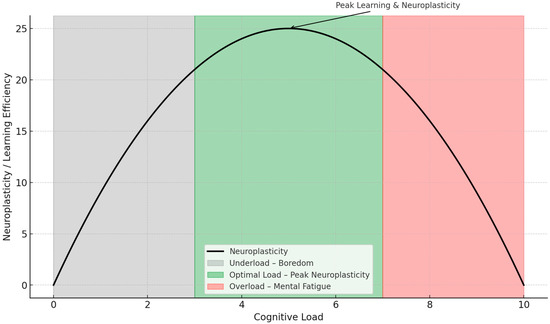

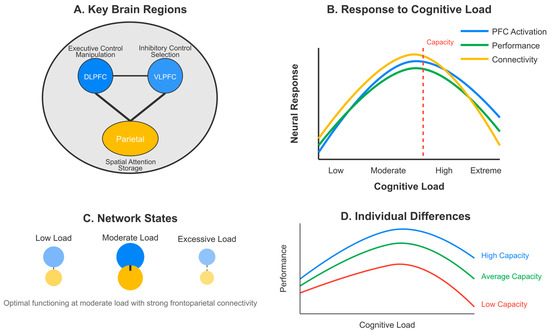

Figure 3 illustrates how neuroplasticity and learning efficiency vary with cognitive load. At low levels of cognitive load, learning is suboptimal due to insufficient cognitive engagement (“underload”).

Figure 3.

Inverted U-shaped relationship between cognitive load and neuroplasticity during learning.

Excessive mental effort leads to cognitive overload and diminished neuroplasticity at high levels. Maximum neuroplasticity is achieved at moderate levels of cognitive load, where the cognitive challenge is optimal for stimulating adaptive neural changes. This model supports the theoretical framework that strategic modulation of cognitive load can enhance learning outcomes by promoting neuroplastic efficiency.

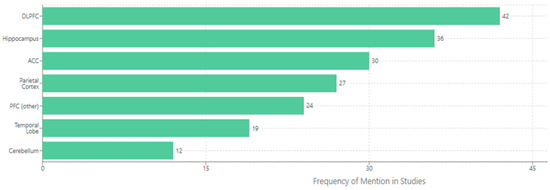

Also, the chart below (Figure 4) illustrates the brain regions most frequently implicated in the relationship between cognitive load and neuroplasticity based on a systematic analysis of functional imaging and brain stimulation studies. The horizontal bar chart quantifies the frequency with which each region is cited across studies examining this relationship. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is prominently mentioned (42 times), underscoring its crucial role in working memory and executive function processes that regulate cognitive load effects. The hippocampus follows closely (36 mentions), reflecting its fundamental role in memory formation and synaptic plasticity mechanisms that respond to varying load conditions. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (30 mentions) is implicated in error detection and cognitive control processes essential for monitoring performance under different load states. The parietal cortex (27 mentions) shows substantial involvement in attentional resource allocation and visuospatial processing during learning tasks. Other prefrontal regions (24 mentions) and temporal lobe structures (19 mentions) demonstrate broader network involvement, while cerebellar contributions (12 mentions) suggest motor learning aspects may also be influenced by cognitive load. This regional distribution underscores that cognitive load effects on neuroplasticity engage distributed neural circuits rather than operating through isolated structures, with frontolimbic connections appearing particularly sensitive to load-dependent modulation [144,146,151,155,158,169,173,181,184,198,207,215].

Figure 4.

Key brain regions mediating cognitive load effects on neuroplasticity.

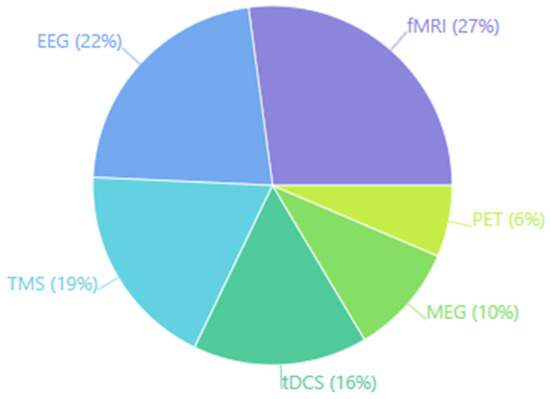

Finally, the chart below (Figure 5) presents a quantitative overview of the methodological approaches employed to investigate the relationship between cognitive load and neuroplasticity. The pie chart illustrates the relative frequency of various neuroimaging and neuromodulation techniques across the analyzed studies. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is the most widely used technique (38 studies, 27%), reflecting its superior spatial resolution for localizing load-dependent activation patterns in structures such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and hippocampus. Electroencephalography (EEG) is the second most common methodology, with 31 studies (22%), highlighting the importance of capturing the temporal dynamics of neural oscillations and event-related potentials that reflect cognitive load fluctuations with millisecond precision. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) constitutes a substantial portion of the research, comprising 26 studies (19%), underscoring its unique capacity to establish causal relationships between regional brain activity and neuroplastic outcomes. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) represents another significant segment (22 studies, 16%), illustrating growing interest in modulating cognitive load effects through non-invasive brain stimulation. Less frequent but still notable are magnetoencephalography (MEG) (14 studies, 10%) and positron emission tomography (PET) (9 studies, 6%), which provide complementary data on neurophysiological processes and neurochemical dynamics, respectively. This methodological distribution illustrates the multi-faceted approach required to comprehensively characterize how cognitive load affects neuroplasticity, leveraging complementary strengths in spatial localization, temporal resolution, causal inference, and neurochemical specificity [138,140,141,143,156,166,170,173,174,177,213,222].

Figure 5.

Imaging and stimulation techniques used to study cognitive load and neuroplasticity.

4.2. [RQ2] in What Ways Can Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation (e.g., tDCS) Be Used to Enhance Learning Outcomes and Neuroplastic Responses Under Varying Levels of Cognitive Load?

Non-invasive brain stimulation techniques, notably transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), demonstrate significant potential for enhancing learning under varying cognitive load conditions. tDCS delivers low-amplitude direct current (typically 1–2 mA) through scalp electrodes, modulating neural activity in regions critical for learning and cognitive control [142,189]. Anodal stimulation typically increases cortical excitability, while cathodal stimulation decreases it, although effects can vary based on neural population characteristics and stimulation parameters [156,201].

tDCS induces changes that resemble long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), thereby strengthening or weakening synaptic connections involved in learning [143,175,199]. Beyond local effects, tDCS influences functional connectivity between brain regions, optimizing network-level processing required during complex learning tasks [152,167,211].

Studies indicate that tDCS efficacy is distinctly modulated by cognitive load levels. Under high-load conditions, DLPFC stimulation facilitates working memory function by enhancing N-back task performance with concurrent increases in frontal-parietal connectivity [144,163]. tDCS enhances attentional control, allowing learners to focus on relevant information and filter distractions under high-load conditions [146,178,205]. Neuroimaging evidence reveals that tDCS reduces prefrontal hyperactivation during demanding cognitive tasks, suggesting more efficient neural resource allocation [149,181,213].

Brain stimulation provides the most substantial benefits when cognitive resources are highly taxed, offering “neural support” that compensates for limited cognitive resources [151,173,208]. Conversely, studies suggest more modest or negligible effects during simple tasks that do not significantly tax cognitive resources [154,186,221]. Individual differences significantly moderate stimulation efficacy—individuals with lower baseline working memory capacity often show more significant improvement during high-load conditions [158,192,216]. Meta-analyses further confirm that baseline cognitive capacity predicts response to tDCS [158,216].

Stimulation parameters have a critical influence on outcomes across various load conditions. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is the most frequently targeted region for cognitive enhancement, followed by parietal regions and motor cortex for motor learning specifically [145,169,201]. Montage configuration significantly impacts efficacy—bilateral DLPFC stimulation (F3-F4) appears superior for tasks requiring interhemispheric processing compared to unilateral approaches [157,183,214]. Online stimulation (during learning tasks) is generally more effective than offline stimulation for tasks involving high cognitive load [147,182,197]. Current intensity of 1.5–2 mA for 15–20 min appears optimal for most cognitive enhancement protocols [153,173,209].

tDCS has demonstrated effectiveness across multiple learning domains under cognitive load. In motor learning contexts, M1 stimulation enhances acquisition of complex movement sequences with optimal results during high-difficulty acquisition phases [139,164,203]. For declarative memory, left temporoparietal stimulation facilitates vocabulary acquisition under high semantic load conditions [150,188,219]. tDCS enhances working memory performance under high-load conditions, with effects often transferring to untrained tasks [141,176,207]. Additionally, tDCS targeting parietal regions enhances performance on complex problem-solving tasks that require significant cognitive resources [159,174,223].

The neurophysiological basis for tDCS-enhanced learning under cognitive load includes several mechanisms. High-resolution EEG studies demonstrate that tDCS-induced modulation of alpha and theta oscillations occurs during working memory tasks, with increased frontal theta coherence observed under high-load conditions [172,204]. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals tDCS-induced alterations in glutamate/GABA balance, potentially optimizing excitation/inhibition ratios for learning [162,195,218]. tDCS facilitates NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) processes, thereby strengthening learning-related synaptic connections [138,172,204]. Functional connectivity changes between task-relevant brain regions support more efficient information processing [155,179,226].

While most acute effects are functional, prolonged or repeated tDCS protocols may induce structural neuroplastic changes supporting long-term retention. DTI studies show white matter microstructural alterations in stimulated pathways after multiple-session protocols [160,187,229]. These structural changes may underline the observed maintenance of performance improvements weeks after stimulation cessation, particularly for skills learned under high cognitive load [170,196,227].

Genetic factors, particularly BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms, mediate tDCS effects on synaptic plasticity during learning tasks [190,222]. This highlights the importance of accounting for individual differences in anatomy, baseline cognitive function, and task demands to enhance efficacy [161,190,222].

Advanced technological approaches are emerging to optimize tDCS for modulating cognitive load. EEG-guided closed-loop tDCS systems that adjust stimulation parameters in real-time based on cognitive load markers could optimize learning outcomes [166,193,225]. Computational models utilizing finite element methods enable precise predictions of current flow based on individual neuroanatomy, allowing for targeted stimulation of task-relevant networks [161,217].

Multimodal approaches combining tDCS with other interventions show promise. Integrating tDCS with cognitive training protocols, neurofeedback, or other neuromodulation techniques may produce synergistic effects [148,184,217]. Combined tDCS-fMRI studies reveal that stimulation-induced changes in frontoparietal networks correlate with performance gains on high-load tasks, suggesting a potential neuroimaging marker of effective intervention [155,226].

These findings have substantial clinical and educational applications, with tDCS potentially offering targeted cognitive enhancement when learning resources are taxed. The evidence suggests that targeted stimulation of task-relevant brain regions, with parameters optimized for individual learners and specific task demands, can effectively augment traditional learning approaches [171,191,220]. As our understanding of neurobiological mechanisms continues to evolve, brain stimulation may become an increasingly valuable tool for educators, clinicians, and learners in cognitively demanding learning contexts [177,194,231].

Building on the established findings, further research illuminates additional dimensions of tDCS application for learning enhancement under cognitive load. Dose–response relationships reveal non-linear effects, with moderate stimulation parameters (1.5 mA for 15 min) often producing optimal outcomes compared to higher intensities that may disrupt homeostatic plasticity mechanisms [165,180,210]. This non-linearity appears particularly pronounced under high cognitive load conditions, suggesting a delicate balance between beneficial neuromodulation and network disruption [168,212].

The temporal dynamics of tDCS effects warrant careful consideration when designing protocols for learning enhancement. Stimulation timing relative to task performance significantly impacts outcomes, with evidence suggesting that priming the neural system through pre-task stimulation (10–15 min before learning) may optimize encoding processes during subsequent high-load learning episodes [147,202,224]. Consolidation processes also appear susceptible to enhancement, with post-learning stimulation facilitating the stabilization of offline memory, particularly for material learned under challenging conditions [185,215,228].

Task-specificity emerges as another critical factor in tDCS efficacy under varying load conditions. Transfer effects appear to be most robust when stimulation targets networks directly relevant to both training and transfer tasks [141,187,207]. This specificity extends to cognitive load manipulation—studies employing parametric increases in difficulty reveal threshold effects where tDCS benefits emerge only after certain load thresholds are exceeded [154,198,221].

The interaction between tDCS and sleep-dependent consolidation represents a promising frontier. Stimulation before sleep enhances overnight consolidation, particularly for material learned under high cognitive load, potentially by facilitating changes in sleep architecture that support memory integration [170,196,227]. This suggests potential complementary mechanisms between neuromodulation and natural sleep processes that may be leveraged for optimal learning outcomes.

Recent methodological advances have improved protocol optimization. High-definition tDCS (HD-tDCS), which utilizes smaller electrodes in various montage configurations, enables more focal stimulation of specific neuronal populations involved in target cognitive processes [139,179,230]. This enhanced targeting precision improves the spatial specificity of interventions, allowing more nuanced modulation of networks supporting learning under cognitive load [151,206,220].

Developmental considerations introduce another dimension of complexity. Age-dependent effects are observed across the lifespan, with evidence suggesting potentially heightened response to stimulation during developmental periods characterized by greater neuroplasticity [153,191,223]. Conversely, tDCS may serve compensatory functions in aging populations, with larger effect sizes often observed in older adults performing cognitively demanding tasks [158,194,216].

From an implementation perspective, integrating tDCS into educational settings requires careful balancing of efficacy, safety, practicality, and ethical considerations. Portable stimulation devices with standardized montages offer the potential for broader application; however, questions remain regarding the optimal training of administrators and the selection of parameters for diverse learning contexts [177,200,231]. These considerations become particularly relevant when addressing learning disabilities characterized by specific deficits in working memory or attention—conditions where cognitive load thresholds may be lower and tDCS effects potentially more pronounced [144,186,209].

The convergence of findings across research domains indicates an emerging framework for optimizing tDCS applications based on cognitive load dynamics. This framework suggests that stimulation protocols should be tailored to (1) individual baseline capabilities, (2) specific task demands, (3) learning phase (acquisition vs. consolidation), and (4) desired transfer parameters [148,176,217]. Such a personalized approach acknowledges the complex interactions between neuromodulation, cognitive resources, and learning processes [161,193,222].

In summary, the growing body of evidence supports the judicious application of tDCS to enhance learning under cognitive load conditions, particularly when protocols are optimized based on task demands, individual characteristics, and specific learning objectives. Future research should focus on establishing standardized protocols suitable for educational and clinical implementation, clarifying biological mechanisms underlying observed effects, and developing more sophisticated closed-loop systems that can adapt stimulation parameters based on real-time neural and cognitive states.

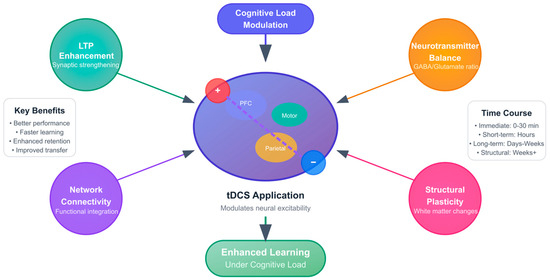

Figure 6 illustrates the comprehensive neuroplastic framework through which transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) enhances learning outcomes under conditions of cognitive load. The diagram presents a multi-mechanistic approach centered on brain stimulation application, with four primary neuroplastic pathways radiating from the central brain representation.

Figure 6.

Neuroplastic Mechanisms of tDCS-Enhanced Learning.

The central brain illustration depicts typical tDCS electrode placement with anodal stimulation (red, positive electrode) positioned over the target region and cathodal stimulation (blue, negative electrode), providing the return path for current flow. The brain regions are color-coded to represent the primary targets identified in the literature: the prefrontal cortex (purple) for executive control and working memory, the motor cortex (green) for skill acquisition, and the parietal cortex (orange) for spatial processing and attention networks. The curved purple line represents the current flow path between electrodes, demonstrating how tDCS modulates neural excitability across targeted brain regions.

Four distinct neuroplastic mechanisms are highlighted through color-coded circular representations surrounding the brain. LTP Enhancement (teal) represents synaptic strengthening processes [138,172,204], fundamental to memory formation and learning consolidation. Neurotransmitter Balance (orange) depicts the modulation of GABA/glutamate ratios [162,195,218], optimizing excitation-inhibition balance for enhanced neural processing. Network Connectivity (purple) illustrates improvements in functional integration [155,179,226], facilitating more efficient communication between distributed brain regions. Structural Plasticity (pink) represents white matter changes [160,187,229] that support long-term retention and skill maintenance.

The flow diagram demonstrates how Cognitive Load Modulation (blue input box) serves as the contextual framework for tDCS application, with arrows indicating the directional influence toward enhanced learning outcomes. The Enhanced Learning Outcome Box (green gradient) represents the convergent effects of all neuroplastic mechanisms, emphasizing improvements specifically under cognitive load conditions [151,173,208].

Supporting panels provide additional context through Key Benefits (performance, learning speed, retention, and transfer) [140,143,149] and Time-Course information spanning from immediate effects (0–30 min) to long-term structural changes (weeks) [170,196,227]. Temporal progression indicates that while immediate molecular and synaptic changes occur during stimulation, network-level modifications develop over hours to days, and structural plasticity emerges over weeks of repeated intervention.

This integrative framework demonstrates that tDCS-enhanced learning results from the coordinated activation of multiple neuroplastic mechanisms, with effects amplified under high cognitive load conditions where endogenous neural resources are maximally challenged. The color coding facilitates understanding of how different biological processes contribute to the overall enhancement of learning efficiency through targeted brain stimulation.

4.3. [RQ3] What Roles Do Specific Brain Regions—Such as the Prefrontal Cortex—Play in Mediating Learning and Working Memory Performance Under Cognitive Load, and How Does This Relate to Functional and Structural Connectivity?