Abstract

There is growing worldwide concern about eating healthily and consuming local food. Consequently, urban agriculture has become a topical issue, especially in light of increasing demographics. The present article investigates and assesses how urban agriculture can be implemented to ensure greater food security and achieve sustainable development goals. The methodology consisted in distributing a worldwide survey, along with interviews with project managers of two urban agricultural practices in the cities of Valladolid and Segovia (Spain). The survey gathered 250 responses from nearly all continents, ensuring a diverse and global perspective and that most respondents were familiar with the concept of urban agriculture (80%) rather than food security (57.4%). The survey also revealed that 88.1% of respondents expressed their willingness to be engage in such projects. The interviews brought out a number of common points, such as ensuring that residents are properly aware about the value of integrating the food sector into cities and the benefits it provides, such as organizing activities and workshops, etc. However, promoting small organizations and start-ups linked to local production and consumption and integrating urban planning experts is crucial to ensure more resilient and sustainable cities. This research uniquely integrates quantitative survey data with in-depth qualitative case studies, linking global perceptions of urban agriculture and food security with local realities.

Keywords:

urban agriculture; food security; sustainable development goals; survey; interviews; Spain 1. Introduction

Nowadays, it is extremely important to ensure sustainable urban food systems, given that urban areas are experiencing rapid population growth, intensive food commercialization and unhealthy nutritional patterns [1,2]. Indeed, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme estimates that 60% of the population will live in urban areas by 2030 [3,4], and where rapid urbanization and increasing industrial agricultural production exist, they have led to a growing disconnection between urban dwellers, their food sources and their connection with nature, distancing people from recent contact with each other [5,6]. Moreover, we live in a time of concern for people’s mental health and well-being, as depression is now the leading cause of ill health and disability, with over 300 million people affected, according to the World Health Organization in 2017 [7,8]. However, there is a growing realization that connection with nature contributes significantly to our mental health and well-being [9].

Considering this current situation, policymakers and scientific researchers, therefore, see urban agriculture (UA) as a promising pillar of food security (FS) and urban resilience [9,10]. UA has been defined by the FAO as “the cultivation of plants and the raising of animals for food and other uses in and around cities, along with related activities such as production and delivery of inputs, processing and marketing of products” [11,12]. Based on this definition, we clearly understand that UA is the cultivation, processing and distribution of food products by growing plants in and around cities serving to feed local inhabitants [13,14,15]. It is also characterized by the systematic and extensive occupation of unused land in urban areas, with the establishment of individual, community or collective gardens and allotments [11,16].

The success of UA has been widely recognized for its benefits, which are aligned with aspects of sustainable development [5]. The social aspect includes social inclusion and integration, along with raising awareness; the environmental aspect relates to environmental protection, biodiversity preservation and climate regulation; and the economic aspect is linked to cost savings and healthy produce at a lower price [17,18]. Moreover, the successful implementation of UA is strongly linked to its positive perception by the public for those who live within urban areas and for the wider community in general [19]. UA contributes to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably FS and improved nutrition (SDG 2), the promotion of sustainable and resilient cities (SDG 11) and the preservation of terrestrial ecosystems (SDG 15) [20,21]. Additionally, it also promotes sustainable consumption and, to a greater extent, production patterns (SDG 12), and it can strengthen social inclusion and equitable access to food resources (SDG 10) [22,23].

This research aims to achieve two objectives which, combined, are perfectly complementary and lead us to a main and comprehensive result. Firstly, a quantitative survey to provide an overview of perceptions of the role of urban agriculture in food security; secondly, an analysis of two qualitative case studies has been conducted in Spain to deepen this understanding by exploring in a more concrete and real way how urban agriculture is practiced and experienced at a local level. By combining these two approaches, the research allows us to capture global trends in perceptions of urban agriculture while grounding them in the lived experiences of project leaders in two Spanish cities, thus linking general attitudes to specific urban governance and implementation dynamics. Moreover, despite the growing number of research studies on urban agriculture and food security, a comprehensive understanding integrating both large-scale perceptions and site-specific case studies remains limited, and this is precisely where the present research makes a significant contribution, by providing a more qualified and comprehensive perspective on the role of urban agriculture in achieving sustainable food security.

This research paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology used to carry out this study, including the implementation and distribution of the survey, as well as the approach taken in the interviews. Section 3 presents the results obtained from the two research sections, outlining the findings with diagrams and tables to make them more comprehensible, leading on to the Section 4, which is based on an evaluation of the results, drawing contrasts with the work of other researchers, followed by a series of conclusions and findings, together with recommendations for future studies.

2. Materials and Methods

The purpose of this investigation is to gain a precise understanding of the population’s perception of UA, while establishing direct contact with project leaders to gain a more detailed insight into how such initiatives operate, the obstacles they face and their main challenges. To address our research problematics, a mixed-methods approach was adopted, involving different research methodologies, including a questionnaire survey and semi-structured interviews. The combination of these approaches enabled us to obtain a precise and in-depth understanding of the actual situation, featuring a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative analysis [24].

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This investigation has involved the integration of several theories that are essential for the proper performance of this research and for a complete and accurate assessment of our problematics. The survey comprised a series of questions that helped to better identify the population being evaluated, which allowed us to base our answers around this target population. Moreover, the development of the questions in relation to the adoption and influencing factors were underpinned by the Theory of Planned Behavior [25] and the COM-B model [26]. Regarding the interviews, the theory used was that of social practices [27]. It offered a very precise approach to understanding the behavior of individuals in the face of our problem, by examining the words of our participants. This theory allowed to better explore and evaluate the results through the responses collected, by assessing the participants’ engagement in specific practices, their applications in their daily lives and how changes in materials, skills and meanings can influence their behavior. Analysis using Social Practice Theory shows how changes in practices can contribute to lasting changes in behavior and attitudes.

Besides the above-mentioned theories, a complementary analysis of the interview and survey data allowed us to provide an understanding of the psychological factors that influence individuals’ behavior and attitudes in different contexts, as well as their decision-making in terms of actions, which will be further elaborated on and discussed in the following subsections [25,28].

2.2. Sampling Frame and Sampling Technique

The sample frame targeted individuals with direct or indirect involvement in UA, encompassing practitioners, researchers, policymakers and community members. Given the exploratory nature of the study, the selection process sought to capture a broad and diverse range of perspectives, ensuring the inclusion of both experienced and novice participants. This approach allows for a better understanding of the dynamics of the different contexts [29].

A random sampling method was used to maximize respondent diversity and avoid selection bias [30,31]. Although no strict stratification was applied, efforts were made to encourage responses from diverse demographic and professional groups to improve the robustness of the results. The survey was disseminated worldwide via our institutional and professional networks and our international research team, as well as our collaborators in several projects, enabling broad geographic and demographic coverage and diverse participation across all continents, offering a global visualization and perception of the worldwide perspective of urban agriculture and food security, not only at local and national levels, but also on an international scale. In addition, this approach involved voluntary participation while ensuring the representation of the various UA communities.

2.3. Data Collection and Administration

The survey was distributed between May and June 2022 in an online manner and at the national and international level, through our networks, via e-mail, colleagues and projects, etc., and its establishment was performed through the Google Form platform, for its efficiency, simplicity and feasibility. It should be emphasized that, given the purpose of this survey, no reliability analysis was applied, since such tests were not necessary and the questions were essentially descriptive and aimed at capturing perceptions, experiences and practices, rather than measuring hidden concepts or performing parametric analyses. The interviews, on the other hand, were conducted during the same period, focusing on two urban agricultural initiatives located in Spain, namely “Alimenta Conciencia” in the city of Segovia” and “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid”.

The questionnaire was completed in full anonymity, with respondents’ consent and acceptance of the general rules prior to the start of the survey, regarding the use of data in this investigation. The interviews with the project leaders of both initiatives were recorded with their consent vocally (in Spanish), transcribed and professionally translated into English for in-depth interpretation of the results. These transcriptions were subsequently coded using NVivo 14 Software, which enabled to better structure the results, and thus obtain all the information needed for interpretation.

2.4. Content of the Questionnaire and Interviews

Different variables were defined and targeted to better understand the content of these questionnaires and interviews. Indeed, this theory, employed by Ajzen in 1991 [25], provides an in-depth understanding of human behavior, since it identifies three interdependent and identifiable dimensions: ability, opportunity and motivation, which are considered essential for the behavior to occur [26]. Ability refers to the skills and knowledge required by the individual; opportunity encompasses the environment and external conditions that enable the individuals to better identify themselves, while motivation includes intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Consequently, this analysis provides a comprehensive basis for analyzing the behavior of the individuals concerned. Table 1 provides a more detailed explanation of each of these variables and presents some of the questions that were asked, both in the questionnaires and in the interviews:

Table 1.

Main questions employed in the survey and throughout the interview.

Table 1 provides a very clear explanation of the different variables highlighted in this research, as well as presenting the questions that were asked to our interviewees and survey respondents. We can clearly see that this is a very good method of bringing the two approaches together, ensuring that they are both brought coherently into one overall framework.

Besides the above series of questions, other aspects were addressed, such as the definition of “urban agriculture,” “food security” and other aspects related to their integration with the SDGs, all through their own understanding, via a series of proposed answers. Indeed, on the basis of their answers, we can better frame the population being assessed, better understand how they assimilate this knowledge and, therefore, better draw appropriate conclusions for our investigation. Furthermore, based on these responses, it would be more accurate to assess the current state of knowledge regarding the integration of the food sector in cities through UA, and thus, in the case of negative responses or lack of interest on the part of stakeholders, to determine what needs to be enacted to address this situation.

3. Results

The results obtained from the questionnaires and interviews are presented and explained in the following subsections, illustrated with tables and figures to make their understanding and interpretation more effective and straightforward.

3.1. Results from the Survey

As previously mentioned in the methodology, the survey was distributed using a random sampling method to ensure a representative sample. This multi-faceted distribution approach allowed us to reach a wide range of potential respondents from different professional backgrounds and geographical locations, with a total of 250 respondents from all over the world. This diversity ensures the robustness and generalizability of our results, as it encompasses the perspectives of individuals from different cultural, social and economic backgrounds.

3.1.1. Characteristic of the Respondents

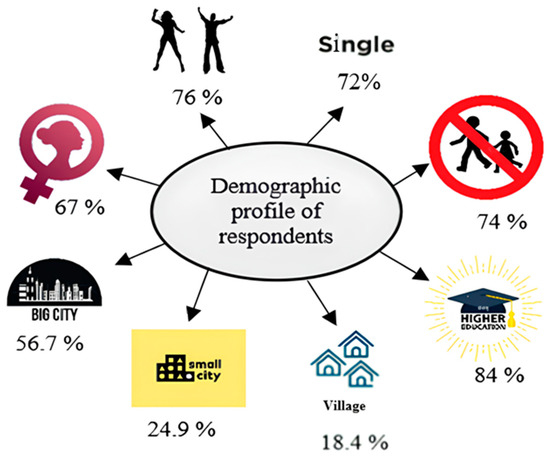

Identifying the characteristics of the respondents was the first step in designing the median profile studied in this study. Indeed, Figure 1 clearly and easily presents all the details required about our respondents.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the survey respondents.

From Figure 1, it can be seen that the number of female respondents far exceeds the number of male respondents, with 67% female responses. Moreover, 72% of our respondents are single and in the 18–35 age range, and the majority have no children. In terms of place of residence, most of our respondents live in cities and only 18% live in villages. According to Figure 1, the demographic profile of the respondent appears to be that of a young, single woman without children, with a higher level of education and who lives in the city.

3.1.2. Geographic Distribution of the Respondents

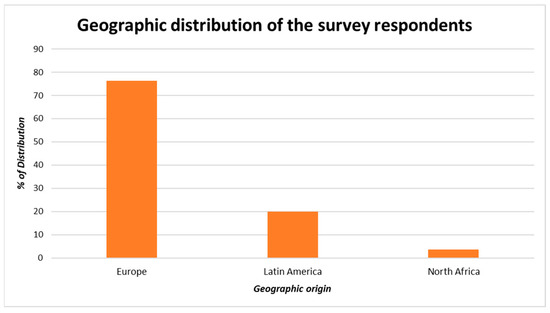

Regarding the residence of our respondents, it should be noted that the survey was conducted on a global scale, bringing together participants from a variety of geographical regions. Figure 2, therefore, presents the geographical distribution of respondents to illustrate the geographic diversity of the sample and to support the global character of the study, rather than to perform a specific comparative country analysis.

Figure 2.

Percentage share of survey respondents’ geographical distribution.

The results from Figure 2 show that 76.3% of responses came from European countries, including Spain, with the highest percentage of responses (20.4% out of 76.3%), followed by Ukraine, the United Kingdom, France and a few other countries from the rest of Europe. The second main category with participants who responded to our survey was from the Central American countries, mainly the Dominican Republic, with 20% of responses, and, finally, the third category was from North African countries, mainly Morocco, with 3.7% of responses. These results underline the broad geographical distribution of our survey (Figure 2).

3.1.3. Knowledge of UA and FS

In order to address our research question about the public’s perception of UA and FS, numerous questions were asked to our interviewees, including their knowledge of UA and FS, the link between the two concepts and their importance in ensuring healthy and sustainable food systems, their willingness or not to support the implementation of these practices in cities and their level of interest in participating in such projects, etc. These findings are presented below:

- Definitions and concepts

One of the main questions asked to our respondents as part of the survey concerned their knowledge of UA and FS. Indeed, we presented a series of definitions relating to each of the two concepts, and they had to choose the right ones. According to the results obtained, 78.80% of responses concerning the definition of UA were correct, meaning, according to Olsson et al., in 2016: “an agricultural production system that is integrated into urban and peri-urban landscapes and is in line with the perspective of sustainable development” [32]. Regarding FS, only 57.40% of the population surveyed knew the correct answer, which is, according to Capone et al., in 2014, “having access for all people at all times to enough food to lead an active and healthy life” [33], while 42.60% had the wrong answer, thinking it was an international law or organization;

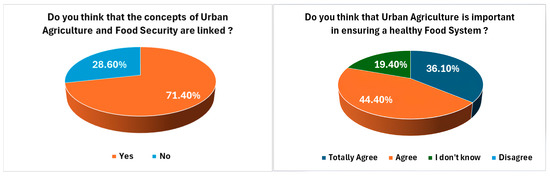

- Link between UA and FS

Respondents to this survey were asked a series of questions to better understand their perception of the link between UA and FS, along with their opinion on the importance of UAP in ensuring a sustainable food system. These findings will enable a better understanding of our audience’s attitudes towards these two concepts, and will, therefore, allow to draw relevant conclusions. This information is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Urban agriculture and its link to food security (left); urban agriculture in ensuring a healthy and sustainable food system (in %) (right).

Regarding the link between UA and FS, Figure 3 shows that 71.40% of the respondents confirm agreement that both concepts are linked, while 28.60% believe that this link does not exist. Moreover, 80.50% of the respondents agree that this link will ensure a healthy and sustainable food system, while 19.40% disagree with this achievement. The percentages of disagreements present quite a small percentage compared to the majority, but this should still be considered and evaluated;

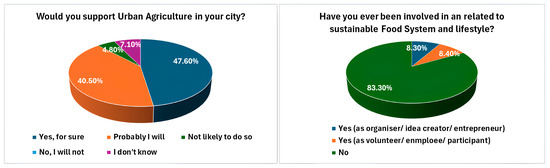

- Implementation of UA in cities

Another important aspect that needs to be addressed in this study is the integration of UA in cities and whether our respondents have ever participated in such projects. The results are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Supporting urban agriculture within cities (in %); involvement in urban agricultural practices and projects (in %).

Figure 4 shows that almost 47.60% of respondents are willing to support the inclusion of UA areas and practices in their city, and 40.50% are likely to do so (88.10% in total). However, 11.90% of respondents would not be ready to do so, which is a fairly low percentage compared to the rest of the responses. Moreover, Figure 4 shows that most of the responses would support the implementation of initiatives in their cities, but most of them have never been involved in an UA initiative.

Recognizing the differentiations of all the above-mentioned results enables greater understanding of the attitudes and multiple perspectives surrounding the involvement of UA in cities, allowing for better-informed decision-making and policymaking in this area.

3.2. Results from the Interviews

In order to make our results more concrete and realistic, we selected two UA initiatives from Spain, in order to evaluate their objectives, benefices, improvement and obstacles and, therefore, to draw conclusions and recommendations. The selection of the two urban agriculture initiatives was based on their compatibility with the objectives of our research problematics, respecting criteria that were aligned with our inquiries into the transition to sustainable food systems, as well as on the availability of relevant data and institutional contacts, which enabled an in-depth qualitative analysis. The following sections illustrate the previous points in further detail, enabling us to gain a better understanding of each of the two initiatives and to draw appropriate and relevant conclusions.

Interviews were carried out with the project managers of two initiatives, namely “Alimenta Conciencia” in the city of Segovia” and “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” in the city of Valladolid. These interviews allowed us to obtain a considerable amount of information about two projects in Spain, which allowed us to gain a general ideal about the situation in Spain, as well as gathering, through the project managers’ own statements, information about the activities carried out, the objectives they would like to achieve and the obstacles they are encountering.

3.2.1. “Alimenta Conciencia” in Segovia City

Segovia is an active city in terms of health and equity, education and participation. To achieve a sustainable and healthy food system, Segovia’s sustainable food strategy has the objectives of coordinating between the different administrations and promoting better administrative coordination

- Presentation of the initiative

The “Alimenta Conciencia” initiative was launched in 2019. However, due to the far-reaching effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the expected timeframe for completion of the project was postponed from 2022 to the end of 2023. This delay was imposed due to major unexpected challenges posed by the pandemic, such as limited access to resources, restricted supply chains and the necessity to adjust project activities to ensure the safety of the participants. The interview was conducted with the coordinator of the “Alimenta Conciencia” project, who was very helpful and who agreed to answer to our questionnaire without any problem;

- Objectives and motivations

The main objectives of this initiative are to better know what is produced and consumed and how this affects the local economy and depopulation, as well as promoting a more sustainable, local, healthy and seasonal diet. Indeed, with the aim of combating food insecurity and promoting awareness, it was necessary to ask our interviewee about the motivation of creating and working on such an initiative. The motivations are therefore the following: “I am aware of the importance of food in this area”, which means to ensure a sustainable development and: “I have a conception of the university academy as an information transfer”, which means to contribute as much as possible to a better world for all, along with reconnecting people with nature and eating locally. Indeed, these statements by the project manager show and explain the reasons and motivations that led them to get involved and manage such urban agriculture projects, as well as the implementation and its benefits, something that allowed them to fight for its realization and thus have this motivation to implement it in the best possible way.

These challenging objectives are being achieved through a carefully designed framework, consisting of four key steps that are presented in the following Table 2:

Table 2.

Four key steps to achieve the challenging goals of the “Alimenta Conciencia” initiative.

From Table 2, we can clearly see that the “Alimenta Conciencia” initiative has many objectives that can be classified into four aspects. Collaboration and cooperation are the first main step, which should be enacted among all the social actors involved in the projects, as the success of such an initiative depends on collective efforts, and meaningful engagement and partnerships are essential for the overall impact of the project. Next comes the step of increasing organic production, as it offers many benefits, including environmental sustainability, improved soil regeneration and healthier food production for consumers (Table 2). Then comes the consumption aspect, where this UA initiative encourages citizens to prioritize products grown in or near the city, known as “Segovia Eco Kilo 0”, along with supporting the local economy, contributing directly to the livelihoods of local farmers and producers, sustaining rural communities and creating jobs. Finally, there is the communication and education aspect, which is considered a fundamental aspect and where the project aims to raise awareness and encourage people to adopt sustainable practices, ensuring a more sustainable and healthy future for current and future generations.

In terms of motivations, our interviewee mentioned that “I am aware of the importance of food in this area”, which means helping to ensure sustainable development, and she also mentioned that she would like this to be available for “current and future generations”. Indeed, these motivations are aligned with the objectives of sustainable development, in particular improving nutrition (SDG 2), the promotion of sustainable and resilient cities (SDG 11), the promotion of sustainable consumption (SDG 12), and being able to strengthen social inclusion and equitable access to food resources (SDG 10);

- Activities carried out

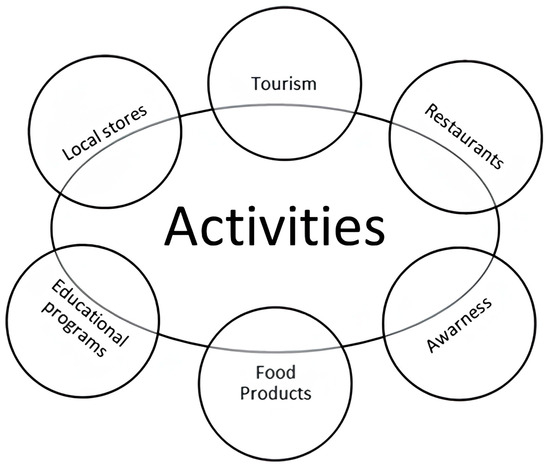

In order to promote a sustainable and healthy food system in and around the city of Segovia, “Alimenta Conciencia” is deeply involved with a series of actions and activities, which are presented with further details in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Activities realized in “Alimenta Conciencia” initiative.

The “Alimenta Conciencia” initiative aims to implement actions and activities to ensure a more sustainable and healthier food system. This objective is being achieved through a number of activities shown in Figure 5. Indeed, the aforementioned initiative has established three local stores in Segovia, encouraging farmers in the province to sell their local produce in these stores, and encouraging consumers to avoid traveling to other distant markets, while still having access to healthy local groceries. In addition, “Alimenta Conciencia” is committed to ensuring sustainable gastronomic tourism by organizing various awareness-raising activities to improve local knowledge, while encouraging local production and consumption. Finally, our interlocutor stressed that “it is necessary to carry out numerous educational activities with students to clarify the importance of healthy, local food” (Figure 5);

- Main challenges and problems encountered

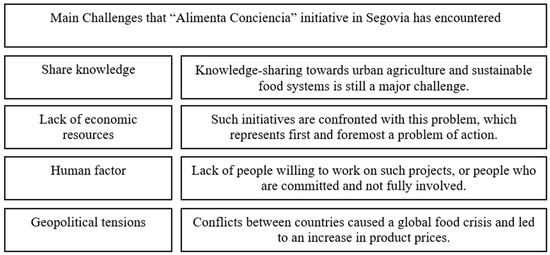

In addition to all the positive impacts that the “Alimenta Conciencia” initiative is bringing to the residents and the city of Segovia, it faces some challenges that are worth highlighting, and which are presented in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Main challenges that “Alimenta Conciencia” initiative in Segovia has encountered.

Figure 6 emphasizes that, in addition to the activities carried out, knowledge-sharing and a more positive attitude towards food systems are still a major challenge. Furthermore, our interviewee pointed out that “it’s difficult to change people’s consumption patterns, switching to the consumption of local and nearby products”, which means that the “Segovia Eco Km0” is still a work in progress and should be further promoted and shared with everyone.

Regarding the problems encountered, our interlocutor emphasized the lack of economic resources, which the current and other similar initiatives face, and which is, above all, a problem in the conduct of action. Another important factor is the human factor; there is a lack of people willing to work on such projects or people who are committed and not fully involved. One other major aspect that was mentioned was the geopolitical tensions. Indeed, our interlocutor mentioned that “this has caused a global food crisis and led to an increase in product prices”. It is currently necessary to find alternatives and create a healthy and comfortable environment to provide people with local produce (Figure 6).

3.2.2. “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” in Valladolid City

The city of Valladolid has developed a process of reflection on the local agri-food system. This process of research and reflection has led to a participatory process to draw up a food strategy for the city, which will then be translated into an action plan. Meanwhile, the strategy evaluated in this research study has entered its implementation phase, which is currently underway.

- Presentation of the initiative

The Valladolid City Council, the Entretantos Foundation and the University of Valladolid, joined in 2019 by the MercaOlid and VallaEcolid associations, launched the project “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” Project in 2016. Regarding the conducted interview, it was carried out with the Councilor of the Environment and the fourth Deputy Mayor of the Valladolid City Council (Ayuntamiento de Valladolid, in Spanish), to whom we would like to thank for the warm welcome and for answering all our interview questions in a smooth and efficient way. Moreover, the city of Valladolid and its surroundings have been developing a process of reflection on the local agri-food system over the last few years to start launching a participatory process for the development of a food strategy of its own and ensure new strategies such as “Valladolid’s Agri-Food Strategy: participatory process”;

- Objectives and motivations

According to our interviewee, the main aim of the “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” is to promote a space for collective processing of the food system, to work with other sectors for a more prolonged use of processed foods, along with broadening sales channels. Moreover, opening up a niche in catering with the possibility of developing new allergen-free products and innovation is considered one of the main objectives of these initiatives. Indeed, achieving these objectives would generate very positive learning, relationships and synergies for the local food system.

Regarding motivations, our interviewee mentioned many aspects, such as “People who work the land are the local producers of Valladolid and the surrounding area of Castilla y León and can develop their activities in a politically responsible manner”. Indeed, this aspect is fundamental since farmers complain about this issue, and always mention that they wish to have more facilities from local authorities. Another aspect was mentioned: “People can have access to food close to their homes, without having to travel, called “Km 0”.” Indeed, this aspect is nowadays necessary since ensuring local and closed products to the inhabitants is benefitting both the city and its inhabitants.

Furthermore, these objectives and motivations are entirely in line with a number of SDGs, which cover improving nutrition (SDG 2), promoting sustainable and resilient cities (SDG 11), fostering sustainable consumption (SDG 12) and strengthening social inclusion and equitable access to food resources (SDG 10);

- Activities carried out

The “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” is carrying out numerous activities to achieve its objectives and improve the progress of the project. Table 3 below gives a more detailed description of the activities carried out:

Table 3.

Main activities realized at the “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid”.

According to our interviewee, the main activity organized is the setting up of local markets. This market will connect the community by highlighting the diversity of the town’s products, creating a thriving and dynamic local market for visitors and guests alike. Secondly, educational activities will be organized to highlight the importance of good nutrition. These activities will enable students to learn more about good nutrition and the positive impact it has on our well-being. To this end, a number of practical exercises are organized, such as practical advice on meat planning from experts, nutritional information and healthy cooking techniques and how these can improve our health and daily lives. The final main activity of “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” is to encourage local consumption in the community, supporting local businesses and raising awareness of the benefits of buying local produce. To achieve this, various events, open days and activities are organized to show the local population the positive impact on the environment and its impact on our daily lives (Table 3);

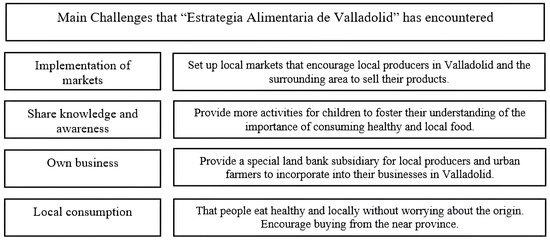

- Main challenges and problems encountered

Based on interviews with our initiative representative, it was possible to identify the main challenges facing the project during its implementation and progress. These aspects are further illustrated in the following Figure 7, which lists each challenge along with its explanation.

Figure 7.

Main challenges that “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” has encountered.

Figure 7 clearly demonstrates that one of the major challenges of “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” is the creation of permanent local markets within the city where local farmers can sell their produce to local consumers. The project will also encourage them to open their own businesses in the city, securing land to make it easier for them to own property and start marketing to the community. Furthermore, the project seeks to organize more knowledge-sharing and awareness-raising activities, to emphasize the importance of local food and to encourage residents to buy at local markets, instead of traveling, and thus respect the “Km0” concept (Figure 7).

Regarding the challenges, the urban initiative “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” pointed out that it is very difficult to share knowledge with residents, to enable them to change their way of thinking about consumption and where they produce. Another aspect that was mentioned was increasing the number of participants in events and how to make these concepts more mainstream in cities, where one interviewee mentioned that “today we need more initiatives on UA and growing food in cities while consuming it, in order to make a change in citizens’ daily diets” (Figure 7).

4. Discussion

This investigation focuses on two main research lines. The first one is related to the public’s perception towards UA and its implementation, and the second was conducted through interviews with project managers. These investigations resulted in many findings that respond to our problematics. Indeed, from the in-depth analysis of the results presented above, there is clear evidence that there is an urgent need for action to create a healthy and sustainable urban environment that meets the needs of current and future generations.

The results of the survey brought the total number of respondents to 250 from all over the world, most of whom were women, living in cities, single and with university and higher education. In terms of their responses to the questions, one very impressive result is that the majority of respondents are familiar with the concept of UA, but this remains at a theoretical level, since when it comes to practical implementation, there is a notable lack of active engagement but the respondents are, nonetheless, interested. This is in line with the work carried out by Kirby et al., in 2021, in many European cities and in the United States, assessing the gap between theoretical knowledge of urban agriculture and practical commitment, where the results of their investigation revealed that many urban participants express a motivation to engage in these practices, but that structural obstacles or a lack of know-how limit their real involvement [34]. This can be considered along with the research carried out in Malaysia by Azmi et al. in 2024, highlighting the gap between theoretical knowledge of UA and practical engagement, which could an obstacle to future project implementation [35]. Another aspect is that most interviewees associate UA with sustainability and bio-products, which is correct, but less so with personal well-being and health issues, which is an essential aspect of UA, since it is seen as a public good for society rather than an individual good. This is fully in line with the work carried out in France by Boukharta et al. in 2023, underlining the impact that the implementation of urban agriculture projects has on both the population and the city, all linked to sustainable development and its goals, along with the connection that exists between these aspects [5]. Furthermore, Hallett’s findings in 2013 also highlight the importance of implementing urban agriculture in cities, which guarantees a really important social impact in people’s daily lives and for their psychological selves [36], something that was also founded in 2023 by Nicholas et al., thanks to an investigation carried out in Singapore, underlining the social benefits that urban agriculture brings to the population, such as creating new friendships and learning to communicate more effectively with people from different backgrounds, as well as the psychological benefits that enhance self-awareness, gratitude and stress reduction [37].

The survey results also showed that rural residents tend to be more familiar with agricultural concepts, as they are often directly involved in food production, and are aware of their daily benefits and advantages. Urban respondents, on the other hand, may not yet be fully aware of the need for this daily link, but the growing awareness and interest in urban agriculture and its influence on moral and physical well-being is now influencing their perception of its value; this finding has also been made by many researchers across different developed and developing countries [34].

Regarding FS, we can see that it is a term that is not well understood by our population, contrary to UA. Indeed, according to the survey outcomes, only half of the respondents understand exactly the definition of FS, something that attracts our attention in this research, since it is a term that should be very common, given its importance and usefulness in our daily life. These findings are in line with the work carried out by Gallegos et al. in 2023 in high income countries, notably Australia and the United States, and in 2017 by Arcari in Australia, which underlines the fact that the general public’s understanding of FS is very limited and/or vague, and that it needs to be more effectively explained to the public at large [38,39]. Another important dimension underlining the results of this survey assessment through our respondents is the link between UA and FS, and most responses agree that the two concepts are linked and believe that this link will guarantee a healthy and sustainable food system. This was explained and proven by Siegner et al. in 2018, through a systematic review highlighting that UA and FS are complementary and that their link is really important for having access to food produced in urban areas [40,41], and also by Optiz et al. in 2016, who analyzed the existing link between the contribution of urban and peri-urban agriculture to food security in the Global North countries [42].

Secondly, from the interviews conducted with project managers from the Spanish urban initiatives “Alimenta Conciencia” in Segovia city and “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid” in Valladolid city, it emerged that the two Spanish initiatives had several points in common and some differences that concern more ways of implementation and solving issues. Indeed, both initiatives are willing to implement UAP within the cities, while combating food insecurity and providing local produce from local farmers and local cultivation, without having the need to go far to other cities. This fact is totally aligned with the work carried out in Canada, United States and United Kingdom by Sonnino (2016) and in various American cities by Siegner (2018), which emphasizes the importance of UA in tackling food insecurity, and which links it directly to both local food production and the resilience of cities [40,43]. Another objective that has been mentioned by both initiatives’ project managers is awareness, considering that it is the key to success of the progress of such an initiative. This progress should start with children, since they are the future generations, so they can influence their parents. This is related to the findings of Russ and Gaus carried out in the United States, underlining the importance of UA education in raising young people’s awareness, commitment and understanding of the benefits to their moral and dietary health [44].

In terms of activities, the two initiatives have set up local markets, enabling local farmers to sell their produce directly to city consumers on the one hand, and allowing residents to buy their produce nearby on the other, thus supporting the local economy while eating healthily and properly. In 2001, Trobe carried out a study in the United Kingdom on the creation of local markets by urban farmers, and also found that most customers visit markets firstly out of curiosity, and then to buy fresh, healthy food, expressing a preference for organic produce [45]. Moreover, awareness-raising is a key activity that both initiatives and other similar ones carry out as much as possible in order to share knowledge about UA, FS and the importance of eating healthy, local food. A similar conclusion is drawn by Orsini: in urban gardens, children spend time playing and helping their parents grow plants, acquiring knowledge about agricultural practices and enabling an intergenerational transfer of knowledge [46]. These activities therefore encourage residents to consume locally, thereby contributing to making cities more resilient [47,48]. This is in line with the findings of Ferreira et al. regarding an investigation carried out in Portugal, who point out that UA and support for local consumption contribute to raising levels of food sovereignty and resilience, as well as implementing new strategies for education, participation and citizenship [49,50].

Many challenges have been mentioned in our analysis; sharing more knowledge is considered the main one for both initiatives, as well as organizing more activities and engaging as many participants as possible. In addition, another aspect is the economic one: the initiatives hope to receive more financial contributions in order to improve these projects and implement other related initiatives. Another aspect is to involve more participants in these UAP and to make them aware of the benefits of setting up urban farming areas in the city, thus ensuring more sustainable and resilient cities. Finally, both initiatives confirmed that they want to help people to open their own business, so that needs to be considered, as well as encouraging the km0 consumption, instead of having to travel to another city.

5. Conclusions

Urban agriculture has become a key research area and a sustainable solution due to its relevance to the current challenges of urbanization, continued population growth, drought and climate change [46,51]. A number of studies underline the importance of urban agriculture in reinforcing food security in urban areas, guaranteeing food self-sufficiency, reconnecting with nature and acquiring new knowledge in this field and, therefore, ensuring self-sufficient and resilient cities [52,53]. Integrating urban agricultural practices has thus been recognized as a strategic approach to promoting sustainable urban development, while encompassing its various objectives, including promoting food security and improved nutrition (SDG 2) and promoting sustainable and resilient cities (SDG 11) with the preservation of terrestrial ecosystems (SDG 15) [20,21]. Furthermore, the involvement of these urban practices within cities fosters sustainable consumption and, to a wider extent, sustainable production patterns (SDG 12) and strengthens social inclusion and equitable access to food resources (SDG 10) [22,23].

Through a survey distributed worldwide, this study assessed the public’s perception of urban agriculture and food security, its implementation, integration and knowledge of the subject. Although the majority of respondents are young, urban and highly educated, the geographic diversity of the sample mitigates potential biases and provides valuable information on general perceptions of urban agriculture, particularly for this category, which represents the future generations. It would therefore be very interesting to hear from them in order to improve their knowledge on the subject. However, the fact that certain demographic groups are over-represented may limit the direct generalization of results to other populations with different demographic profiles, such as people with low levels of education or others who are not in this field. Regarding the interviews, they were conducted with two urban agriculture practices in Spain, namely “Alimenta Conciencia” and “Estrategia Alimentaria de Valladolid”, both located in the Castilla y Leon region (Spain), in order to assess in a concrete and precise manner how these urban practices operate, the obstacles they face, their main challenges and limitations, etc.

Using this combination of approaches resides in the fact that, while the global survey identifies general trends and awareness gaps, the interviews provide concrete and complementary information in specific contexts. This dual approach is considered a strength, as it enables a broad, multi-angled understanding of key terms and thus addresses our problematic issues. Indeed, in this context, this mixed approach has shown that both the global survey and the local case studies indicate a common recognition and affirmation of urban agriculture as a valuable contributor to food security, given its various benefits linked to its role in improving access to fresh food, promoting social links between citizens, protecting the environment and so on. In addition, both approaches emphasize the need for local authorities to support these initiatives and back them up to ensure their long-term viability.

This qualitative and quantitative analysis highlighted a number of conclusions that should be emphasized, and which are as follows. First, education and awareness-raising initiatives are needed to highlight the importance of urban agriculture and its role in achieving food security. These could include school courses, community workshops and public open days to disseminate information and promote understanding among the population, and so on. Second, there should be encouragement of the creation of local stores by local producers, as their creation can make a significant contribution to the development of urban agriculture and the improvement of food security. To achieve this, it is important to ensure financial support, provide training and technical assistance and stimulate new calls for projects. Finally, expert urban planning is crucial to the successful integration of urban agriculture and the creation of sustainable urban environments. For this, urban planners need to draw on their expertise as well as that of architects, designers and other skilled professionals to integrate agriculture into urban spaces, as collaboration is essential to developing inclusive and sustainable urban plans.

Local authorities and urban planners have an important role in integrating urban agricultural practices in cities. Indeed, based on the results of this study, we recommend that municipal authorities and NGOs give high priority to supporting urban agriculture in land-use planning by allocating dedicated spaces, encouraging urban farming zones and community gardens. Moreover, they should provide support by offering technical training, facilitating access to funding and acting as intermediaries between local communities and public institutions, thus integrating urban agriculture into climate adaptation and food security plans, all aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals. Furthermore, the results underline that urban planners should implement participatory approaches and strategies that include urban agriculture professionals in the decision-making process, and design multifunctional green spaces that fulfill both an ecological and a food production function.

This study enabled us to gain a general understanding of people’s perception of urban agriculture, its effects and its contribution to the population, as well as to deepen our understanding of this concept in relation to food security and self-sufficiency. Furthermore, the interviews highlighted several common points, such as the desire to ensure good education and awareness of the value of integrating the food sector into cities, as well as the appropriate organization of activities and workshops. It should be noted that the evaluation of these two urban agricultural practices provides lessons and a better understanding of the implementation of urban practices, not only in these cities, but also in other areas of Europe and the world, as the results of this investigation provide a better understanding of the changes that may have occurred in citizens’ lives during the implementation of these initiatives, across all three dimensions of sustainable development—social, economic and environmental—while emphasizing their experiences and techniques as part of a collective learning process.

The responses from the interviews with the project managers of the two urban agriculture projects in Spain and the global pilot survey are positive in terms of knowledge of the subject, but the survey still needs to be developed to make it more accessible and understandable to all, particularly by encouraging small organizations and start-ups linked to local production. Finally, this investigation can be considered as a basis for future studies aimed at assessing the general public’s perception of urban agriculture, as well as for conducting interviews with experts in the field, since this methodology allowed responses to our problematic, and could provide the basis for other investigations in Spain or worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.F.B., L.M.N.G., L.C.S. and A.C.G.; methodology, O.F.B., L.C.S., A.C.G. and L.M.N.G.; software, O.F.B.; validation, O.F.B., L.C.S., A.C.G. and L.M.N.G.; formal analysis, O.F.B. and L.C.S.; investigation, O.F.B. and L.C.S.; resources, L.M.N.G. and L.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.F.B.; writing—review and editing, O.F.B., L.C.S., L.M.N.G. and A.C.G.; visualization, O.F.B., L.C.S., A.C.G. and L.M.N.G.; supervision, L.C.S. and L.M.N.G.; project administration, L.M.N.G.; funding acquisition, L.M.N.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present work is related to the FUSILLI Project, which is funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under the grant agreement No. 101000717 (https://fusilli-project.eu/) (accessed on 28 February 2025).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. Our research study was conducted in full compliance with the University of Valladolid’s Code of Ethics. The latest version of this code was approved by the Governing Council on 22 July 2022, which can be consulted at the following link: https://secretariageneral.uva.es/wp-content/uploads/III.6.-Codigo-Etico-de-la-UVa.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025.). At the time this research was conducted, the approval processes followed were in accordance with all institutional requirements and regulations for studies involving human participants, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Moreover, informed consent was obtained from all participants through the online survey platform, where participants were informed that, by taking the survey, they indicated they had read and understood the data protection and consent statement and had agreed to participate. For focus groups and interviews, participants provided verbal consent after reviewing data protection information. All participants were informed of data confidentiality measures and their rights under GDPR requirements, including the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Data were anonymized during analysis and reporting to protect the participants’ identities. In conclusion, all aspects of the research, including participant recruitment, informed consent procedures, data collection, anonymization and storage, were conducted in accordance with institutional ethical standards and European data protection regulations.

Acknowledgments

Ouiam Fatiha Boukharta has been financed under the call for the University of Valladolid’s 2021 predoctoral contracts, co-financed by Banco Santander.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UA | Urban Agriculture |

| UAP | Urban Agricultural Projects |

| FS | Food Security |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

References

- Oliveira, G.M.; Vidal, D.G.; Ferraz, M.P. Urban lifestyles and consumption patterns. In Sustainable Cities and Communities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 851–860. [Google Scholar]

- Alemu, M.H.; Grebitus, C. Towards sustainable urban food systems: Analyzing contextual and intrapsychic drivers of growing food in small-scale urban agriculture. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogar, M.I.; Álvarez, G. United Nations Human Settlements Programme, Background Guide 2024. In Proceedings of the National Model United Nations, San Cristóbal Island, Ecuador, 22 November–1 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat (United Nations Human Settlements Programme). Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III), 44813 (August). 2011. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/habitat-iii (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Boukharta, O.F.; Pena-Fabri, F.; Chico-Santamarta, L.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Sauvée, L. Governance structures and stakeholder’s involvement in Urban Agricultural projects: An analysis of four case studies in France. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2023, 27, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, R.E.; Lupolt, S.N.; Kim, B.F.; Burrows, R.A.; Evans, E.; Evenson, B.; Synk, C.M.; Viqueira, R.; Cocke, A.; Little, N.G.; et al. Characteristics and growing practices of Baltimore City farms and gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radfar, A.; Ferreira, M.M.; Sosa, J.P.; Filip, I. Emergent crisis of COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health challenges and opportunities. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 631008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Guide for Integration of Perinatal Mental Health in Maternal and Child Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Passmore, H.A.; Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Dopko, R.L. Flourishing in nature: A review of the benefits of connecting with nature and its application as a wellbeing intervention. Int. J. Wellbeing 2015, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, S.; Wu, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, F.; Wang, N. Technological Innovations in Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture: Pathways to Sustainable Food Systems in Metropolises. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, E.; Jayo, M. Agriculturas urbanas em São Paulo: Histórico e tipología Agricultures urbaines à São Paulo: Histoire et typologie Urban agricultures in São Paulo: History and typology. Confins 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. “Food Security,” Policy Brief, Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2007; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mougeot, L.J. Growing Better Cities: Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Development; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, S.; Vinatier, F.; Hannachi, M.; Sanz, E.S.; Rudi, G.; Zamberletti, P.; Tixier, P.; Papaïx, J. How can models foster the transition towards future agricultural landscapes? In Advances in Ecological Research; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 64, pp. 305–368. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Moreau, M.; Ménascé, D. Urban agriculture: Another way to feed cities. Field Actions Sci. Rep. 2019, 20, 7–119. [Google Scholar]

- Maćkiewicz, B.; Puente Asuero, R.; Garrido Almonacid, A. Urban agriculture as the path to sustainable city development. Insights into allotment gardens in Andalusia. Quaest. Geogr. 2019, 38, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Subedi, D.R.; Dahal, K.; Hu, Y.; Gurung, P.; Pokharel, S.; Kafle, S.; Khatri, B.; Basyal, S.; Gurung, M.; et al. Urban agriculture matters for sustainable development. Cell Rep. Sustain. 2024, 1, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, R.; Palmer, A.; Kim, B. Vacant lots to Vibrant Plots: A Review of the Benefits and Limitations of Urban Agriculture; Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grebitus, C.; Chenarides, L.; Muenich, R.; Mahalov, A. Consumers’ perception of urban farming—An exploratory study. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukharta, O.F.; Huang, I.Y.; Vickers, L.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Chico-Santamarta, L. Benefits of Non-Commercial Urban Agricultural Practices—A Systematic Literature Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardía, A.; Gómez-Villarino, M.T. Green infrastructure in cities for the achievement of the un sustainable development goals: A systematic review. Urban Ecosyst. 2023, 26, 1693–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.; Caton Campbell, M.; Judelsohn, A.; Born, B.; Morales, A. Planning for Equitable Urban Agriculture in the United States: Future Directions for a New Ethic in City Building; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, J. Introducing Just Sustainabilities: Policy, Planning, and Practice; Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman, N. Mixed methods communication research: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in the study of online journalism. SAGE Res. Methods Cases 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Watson, M.; Pantzar, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; Sage: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, N. Qualitative Research Methods in Psychology: Combining Core Approaches 2e; McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Button, C.; Seifert, L.; Chow, J.Y.; Araújo, D.; Davids, K. Dynamics of Skill Acquisition: An Ecological Dynamics Approach; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Riyaz, A.; Musthafa, H.S.; Raheem, R.A.; Moosa, S. Survey sampling in the time of social distancing: Experiences from a quantitative research in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. Maldives Natl. J. Res. 2020, 8, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Bengart, P.; Shaltoni, A.M.; Lehmann, S. The use of sampling methods in advertising research: A gap between theory and practice. Int. J. Advert. 2018, 37, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E.G.; Kerselaers, E.; Søderkvist Kristensen, L.; Primdahl, J.; Rogge, E.; Wästfelt, A. Peri-urban food production and its relation to urban resilience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, R.; El Bilali, H.; Debs, P.; Cardone, G.; Driouech, N. Food system sustainability and food security: Connecting the dots. J. Food Secur. 2014, 2, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, C.K.; Specht, K.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Hawes, J.K.; Cohen, N.; Caputo, S.; Ilieva, R.T.; Lelièvre, A.; Poniży, L.; Schoen, V.; et al. Differences in motivations and social impacts across urban agriculture types: Case studies in Europe and the US. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 212, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, N.S.N.; Ng, Y.M.; Masud, M.M.; Cheng, A. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of farmers towards urban agroecology in Malaysia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, S.; Hoagland, L.; Toner, E. Urban agriculture: Environmental, economic, and social perspectives. Hortic. Rev. 2016, 44, 65–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, S.O.; Groot, S.; Harré, N. Understanding urban agriculture in context: Environmental, social, and psychological benefits of agriculture in Singapore. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 1446–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D.; Booth, S.; Pollard, C.M.; Chilton, M.; Kleve, S. Food security definition, measures and advocacy priorities in high-income countries: A Delphi consensus study. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 1986–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcari, P. Normalised, human-centric discourses of meat and animals in climate change, sustainability and food security literature. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegner, A.; Sowerwine, J.; Acey, C. Does urban agriculture improve food security? Examining the nexus of food access and distribution of urban produced foods in the United States: A systematic review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, M.; McClintock, N.; Hoey, L. The intersection of planning, urban agriculture, and food justice: A review of the literature. In Planning for Equitable Urban Agriculture in the United States: Future Directions for a New Ethic in City Building; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Opitz, I.; Berges, R.; Piorr, A.; Krikser, T. Contributing to food security in urban areas: Differences between urban agriculture and peri-urban agriculture in the Global North. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R. The new geography of food security: Exploring the potential of urban food strategies. Geogr. J. 2016, 182, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, A.; Gaus, M.B. Urban agriculture education and youth civic engagement in the US: A scoping review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 707896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trobe, H.L. Farmers’ markets: Consuming local rural produce. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2001, 25, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, F.; Kahane, R.; Nono-Womdim, R.; Gianquinto, G. Urban agriculture in the developing world: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 695–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triboi, R.M. Urban Pastoralism around Bucharest: Between Preserving Livelihoods and Adapting to Pressure from Urban Sprawl. Martor. Rev. D’anthropologie Du Musée Du Paysan Roum. 2024, 29, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. The paths to improve china’s urbanization strategy. Chin. J. Urban Environ. Stud. 2021, 9, 2175001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.J.; Guilherme, R.I.; Ferreira, C.S. Urban agriculture, a tool towards more resilient urban communities? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 5, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J.; Madrid-Lopez, C.; Beltran, A.M.; Mendez, G.V. Urban agriculture—A necessary pathway towards urban resilience and global sustainability? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artmann, M.; Sartison, K. The role of urban agriculture as a nature-based solution: A review for developing a systemic assessment framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, H. Urban Agriculture for Food Security? A Qualitative Study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Master’s Thesis, University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ajisope, T. Enabling Urban Agriculture in the Global North and South: A Comparative Study of the UK and Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Salford, Salford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).