Abstract

Urban parks are essential components of sustainable cities, providing vital health, social, and environmental benefits. Using weekly smartphone-based visitation data for 182 parks in Las Vegas from 2019 to 2022, this study quantifies how the COVID-19 pandemic altered park use and identifies the socio-economic, environmental, and infrastructural determinants of these changes. Park visitation in Las Vegas showed a marked early pandemic decline followed by uneven recovery, with socially vulnerable neighborhoods lagging behind. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Random Forest (RF) models were used to capture both linear and nonlinear relationships. The RF model explained 81% of the variance in standardized visitation (R2 = 0.81, RMSE = 0.0415), substantially outperforming the OLS benchmark (R2 = 0.24, RMSE = 0.0656). Domain-specific RF models show that socio-economic variables alone achieve an R2 of 0.88, compared with about 0.70 for housing, environmental/health, and lighting variables, while demographic variables explain only 0.39, indicating that social vulnerability is the dominant driver of visitation inequalities. Phase-specific analyses further reveal that RF performance increases from R2 = 0.84 before the pandemic to R2 = 0.87 after it, as park visitation becomes more strongly coupled with socio-economic and health-related burdens. After COVID-19, poverty, uninsured rates, and asthma prevalence emerge as the most influential predictors, while the relative importance of demographic composition and environmental exposure diminishes. These findings demonstrate that pandemic-era inequalities in park visitation are driven primarily by reinforced socio-economic and health vulnerabilities, underscoring the need for targeted, equity-oriented green-infrastructure interventions in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

1. Introduction

Urban parks are widely recognized as essential infrastructure for urban livability, resilience, and sustainability. A large body of research has documented their contributions to physical and mental health, air-quality improvement, microclimate regulation [1], and everyday social interaction. At the same time, unequal access to parks and green spaces remains a persistent feature of urban inequality, with disadvantaged communities often facing lower availability of, and poorer quality in, nearby recreational environments. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified these dynamics by radically altering the relationship between residents, public space, and urban planning [2]. Restrictions on indoor activities and shifts toward outdoor recreation reshaped how, when, and where people used parks.

International studies show that park visitation sharply declined during the strictest lockdown periods and then partially rebounded as parks substituted for closed indoor facilities [3,4,5], yet these changes were far from uniform across cities, park types, and user groups. Empirical evidence from diverse contexts highlights the strongly context-dependent nature of pandemic-era park-use patterns [6,7,8,9]. In New York City, overall park visits declined by about 50% between 2019 and 2020, while nature reserves and less crowded green spaces attracted relatively more visitors, suggesting substitution toward perceived safer environments [3]. Comparative studies in European cities, such as Edinburgh, report heterogeneous recovery trajectories: playgrounds and social areas regained popularity, whereas forested areas attracted more solitary visitors [4,10]. Research from rapidly growing Asian cities similarly illustrates that some small and peripheral parks gained users during the pandemic, particularly among population groups with limited indoor alternatives [11,12]. Taken together, these findings indicate that COVID-19 did not produce a single global pattern of park use, but rather amplified pre-existing differences in park supply, quality, and user preferences [3,5,11,13,14].

Beyond aggregate trends, the pandemic exposed and often deepened long-standing socio-economic and environmental inequalities in park access. Studies from U.S. and international cities show that low-income and minority neighborhoods experienced larger and more persistent declines in park visitation, despite depending more heavily on public open space for recreation and relief [11,13]. These inequalities are frequently operationalized using composite measures of social vulnerability, such as the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index, which capture poverty, unemployment, lack of health insurance, disability, vehicle access, and household structure. Recent environmental health research further emphasizes that socio-economically vulnerable communities also bear disproportionate burdens of air pollution and chronic disease, including long-term exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and higher prevalence of asthma and poor mental health [15,16]. Such evidence underscores the need to jointly consider social, environmental, and health-related vulnerabilities when analyzing park visitation inequalities, particularly during crises that heighten both health risks and mobility constraints.

The Las Vegas metropolitan region provides a critical setting for examining these intertwined dynamics. As a prototypical desert metropolis, Las Vegas combines rapid suburban expansion, extreme heat, low canopy cover, and highly uneven green-space distribution [17,18,19,20,21]. Previous studies have identified limited park accessibility, lower-quality recreational environments, and pronounced demographic diversity across neighborhoods [19,20]. These conditions are closely linked to environmental health stressors such as urban heat-island effects and elevated air-pollution exposure, as well as sharp socio-economic disparities in income, housing burden, and health insurance coverage [17,18]. Against this backdrop, the COVID-19 pandemic presents an opportunity to investigate how an external shock interacts with existing social and environmental vulnerabilities to reshape park visitation patterns in an already constrained green-infrastructure system.

Despite the quickly growing literature on COVID-19 and urban parks, several critical gaps remain. First, most empirical studies focus on short-term effects during 2019–2020, providing limited insight into how park visitation evolved across multiple years or pandemic phases [22,23,24]. Less is known about whether pandemic-induced inequalities persisted, intensified, or attenuated during the recovery period. Second, while individual predictors of park use such as income, race, or proximity to green space have been widely examined, few studies systematically compare the relative explanatory strength of different domains, including demographic, socio-economic, housing, environmental/health, and infrastructural factors [3,25]. Such domain-level comparisons are essential for clarifying whether social, environmental, or infrastructural dimensions play the dominant role in shaping recreational accessibility. Third, most existing work remains largely descriptive and relies on traditional regression models, without fully exploiting interpretable machine-learning tools capable of capturing nonlinear thresholds and cross-domain interactions. As a result, we still know relatively little about how complex, interacting determinants of park visitation change between pre- and post-pandemic contexts.

To address these gaps, this study develops an interpretable, multi-year analytical framework that traces the temporal and contextual evolution of park visitation inequalities in Las Vegas from 2019 to 2022. Using weekly smartphone-based park visitation records from Safe Graph [26,27,28], combined with socio-demographic, housing, environmental, health, and infrastructural indicators at the neighborhood scale, we examine citywide visitation levels and their determinants over the full 2019–2022 period, and, for RQ3, we further investigate how key determinants shifted between pre- and post-pandemic periods. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression provides a transparent linear benchmark, while Random Forest models, interpreted through tools such as SHAP values and Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) plots, capture nonlinear responses and cross-domain interactions [29,30,31,32,33,34].

Specifically, the study addresses three research questions: (RQ1) How well do different modeling approaches explain overall variation in park visitation across Las Vegas between 2019 and 2022? We hypothesize that interpretable machine-learning models, such as Random Forests with SHAP and ALE, will outperform linear regression in capturing the combined effects of socio-economic, environmental, and infrastructural factors. (RQ2) What are the main socio-economic, environmental, and infrastructural determinants responsible for differences in park use between neighborhoods? We expect that socio-economic vulnerability, particularly poverty, lack of health insurance, and disability, will exert stronger and more consistent influence than environmental or infrastructural variables alone. (RQ3) How did the relative importance and nonlinear responses of these determinants change between pre- and post-pandemic periods? Here we hypothesize a temporal shift in the burden of constraints, from patterns more strongly shaped by environmental and infrastructural conditions to those increasingly dominated by social and health-related vulnerabilities after COVID-19.

This study makes three contributions to the literature on urban parks, environmental justice, and pandemic resilience. First, it offers multi-year empirical evidence on how the COVID-19 pandemic reshaped park visitation dynamics in a highly constrained desert metropolis, documenting both the initial shock and subsequent recovery patterns. Second, it systematically compares the domain-specific explanatory power of socio-economic, environmental/health, housing, and infrastructural factors, clarifying which dimensions most strongly drive park visitation inequalities. Third, it integrates interpretable machine-learning algorithms with phase-specific analysis to reveal nonlinear and temporal mechanisms underlying visitation disparities, thereby advancing methodological approaches for analyzing complex socio-environmental systems.

2. Method

2.1. Study Area

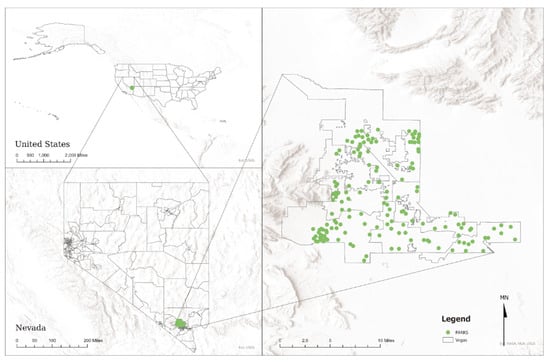

The study area is the city of Las Vegas, Nevada (Figure 1), a prototypical desert metropolis characterized by rapid urbanization, limited green space, and pronounced demographic diversity. The population has grown from approximately 1.3 million in 1998 to over 2.7 million in recent years. However, this expansion has not been accompanied by a proportional increase in green infrastructure, intensifying the urban heat island effect [18,35]. The distribution and quality of green spaces are highly uneven across the metropolitan area. In particular, the City of Las Vegas has been identified as a region with limited park accessibility and lower-quality recreational environments, conditions that have been linked to reduced physical activity and community well-being [19]. Against this backdrop, the Las Vegas metropolitan region marked by the intersection of rapid growth, green-space scarcity, and demographic diversity provides an ideal and representative setting for examining environmental and social inequalities in park visitation. Given its pronounced environmental constraints and socio-economic disparities, Las Vegas serves as a natural laboratory for exploring how external shocks such as COVID-19 exacerbate or reshape inequalities in public space use.

Figure 1.

Study Area.

2.2. Study Design and Framework

This study is structured around three core research questions addressing the overall, domain-specific, and temporal dynamics of urban park visitation in Las Vegas between 2019 and 2022. Building on the literature reviewed in Section 1, we develop an interpretable analytical framework that links each research question to a specific modeling strategy.

The first research question (RQ1) asks how well alternative modeling approaches explain spatial variation in park visitation across Las Vegas neighborhoods over the full study period. To address this, we compare a transparent linear regression benchmark with a nonlinear machine-learning model, estimating Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Random Forest (RF) specifications on the same set of predictors (Section 2.4) [26,27]. All models for RQ1 are estimated on the pooled 2019–2022 sample.

The second research question (RQ2) examines which predictor domains are most strongly associated with visitation levels and how much each domain contributes to explaining disparities in park use. We organize all predictors into five conceptual domains demographic, socio-economic, housing and accessibility, environmental and health exposure, and infrastructure and lighting and assess their relative explanatory strength using domain-specific models (Section 2.3) [36,37]. Like RQ1, all analyses for RQ2 rely on the pooled 2019–2022 dataset and the same predictor set, ensuring that differences in explanatory power reflect domain-level effects rather than changes in the underlying sample.

The third research question (RQ3) investigates how the importance and effects of these determinants evolve across pandemic phases by assessing whether the strength or direction of key predictors shifts between pre-pandemic and post-pandemic periods. To ensure comparability when addressing RQ3, we apply the same modeling configuration and interpretability tools (feature importance, SHAP values, and Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) plots) to the temporal subsets and compare results across phases [31,32,33,34].

To operationalize RQ1 and RQ2, we first construct a pooled full-period dataset covering 2019–2022. To address RQ3, we then define two temporal subsets based on official policy timelines and pandemic milestones: a pre-epidemic period spanning from the week of 31 December 2018 up to 1 March 2020, and a post-epidemic period from 2 March 2020 to 1 January 2023. The pre-epidemic start date corresponds to the first full weekly record in the SafeGraph dataset, which begins on 31 December 2018 but is reported as part of the 2019 data. Policy information was derived from the Nevada state COVID-19 emergency declaration (https://lasvegassun.com/news/2020/mar/12/nevada-in-uncharted-territory-sisolak-declares-sta/ accessed on 12 July 2025) and supplemented with additional scholarly sources [31,38,39].

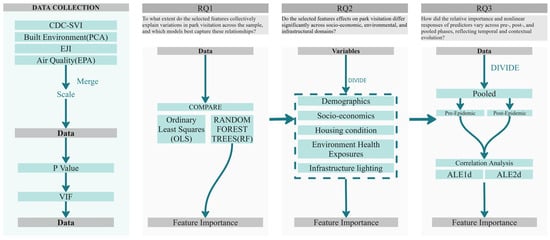

For the phase-specific analyses in RQ3, we estimate RF models separately on the pre-epidemic and post-epidemic subsets, using the same predictor set, RF model structure, and tuned hyperparameters as in the pooled model. We evaluate performance using R2, MAE, and RMSE so that differences in performance and variable importance can be attributed to temporal dynamics rather than to changes in model specification. Standardized visitation is used as the dependent variable for all subsamples. By design, this phase-based specification captures behavioral and policy shifts before and after the pandemic, while the pooled models for RQ1 and RQ2 summarize overall patterns for the full 2019–2022 period. Figure 2 summarizes the overall research framework, integrating multi-domain predictors with pooled, domain-specific, and phase-specific analyses [31,32,34].

Figure 2.

Research framework.

2.3. Data Preprocessing and Variable Construction

The dependent variable in this study is the weekly park visitation count per park, operationalized using the SafeGraph “visits_all_scaled” metric, which represents standardized weekly foot-traffic to points of interest (POIs) classified as parks and open spaces. SafeGraph anonymized mobile device data provide high spatiotemporal resolution and coverage, offering a reliable indicator of population activity patterns before, during, and after the COVID-19 outbreak; prior research has demonstrated the validity of this data source for urban mobility and behavior studies [27,28].

The dataset initially included 199 parks in Las Vegas with weekly visitation records from January 2019 through December 2022. To ensure temporal consistency, parks with missing weekly records exceeding 10% of the total observation period were excluded. After excluding parks or weeks with empty visitation values, 182 parks remained with continuous weekly series spanning up to 208 weeks. Missing weeks were rare (<2%) and were removed rather than imputed to ensure data integrity. The final dataset therefore represents consistent weekly park-level observations and provides a balanced temporal structure for subsequent pooled analyses (addressing RQ1 and RQ2) and for the phase-specific comparisons conducted for RQ3.

We assembled a comprehensive set of independent variables capturing socio-demographic, economic, housing, environmental, and infrastructural characteristics for each park and its surrounding community. To align with RQ2, all predictors were organized into five conceptual domains that reflect key mechanisms potentially influencing park visitation: (i) demographic variables describing the age structure and racial or ethnic composition of the park’s neighborhood (e.g., the percentages of seniors and different racial and ethnic groups); (ii) socio-economic variables representing social and economic vulnerability, including income levels, poverty rate, unemployment rate, uninsured rate, disability prevalence, and related indicators largely drawn from the CDC Social Vulnerability Index (SVI, 2022); (iii) housing and accessibility variables characterizing housing conditions and accessibility constraints, such as housing cost burden, the prevalence of single-parent households, the percentage of households with no vehicle (from SVI 2022), housing vacancy rates, renter occupancy rates, median year built of the housing stock, and the typical distance traveled from home to the park derived from SafeGraph’s distance-from-home data; (iv) environmental and health exposure variables capturing environmental risks and community health burdens, including exposure indices for ambient air pollution (ozone, fine particulate matter PM2.5) [40] and proximity to major transportation infrastructure (railways, highways, and airports) obtained from the CDC/ATSDR Environmental Justice Index (EJI, 2022), which provides standardized 0–100 scores for multiple exposure factors, together with public health indicators such as the estimated prevalence of asthma, high blood pressure, cancer, and poor mental health in the community, sourced from CDC datasets; and (v) infrastructure and lighting variables describing built-environment qualities around each park, focusing on street-level infrastructure within a 1 km radius, including the density and quality of street lighting (average mast height, average wattage, and counts of lights in good versus poor condition) and the presence of green streetscape features.

All covariates were obtained from authoritative sources such as the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS, 2022), the CDC (SVI 2022, EJI 2022, and related health datasets), SafeGraph POI and mobility records, NOAA monthly climate records (2023–2024), and municipal infrastructure inventories, as summarized in Table 1. Detailed street-lighting information was obtained from the City of Las Vegas ArcGIS pro 2024 streetlight inventory, which provides geolocated records of pole-mounted light fixtures; to enhance coverage and verify accuracy, this dataset was cross-validated using high-resolution satellite imagery and Google Street View through manual inspection in GIS [35]. Physical lighting metrics including average mast length (AVG_MASTLENGTH), lamp wattage (AVG_WATT), and counts of functional versus deteriorated lights (COUNT_GOOD, COUNT_BAD) were computed using Python 3.12-based spatial aggregation within a 1 km buffer of each park.

Table 1.

Variable category and resources.

Finally, a composite “Green Streetscape” index (AVG_PCA1–4) was derived through principal component analysis (PCA) on vegetation structure and design variables around each park. Components were retained based on eigenvalues greater than 1 and inspection of the scree plot, and the first four components, which summarized the main gradients in streetscape greenness and enclosure, were averaged to obtain a single composite index used in subsequent models.

To minimize spatial and temporal inconsistencies among data sources, all variables were harmonized to the park-level 1 km buffer resolution: original input variables were spatially aggregated or joined to this buffer level before model estimation. Continuous predictors were standardized using z-score transformation to reduce scale discrepancies across demographic, environmental, and infrastructural features, while categorical or proportion variables were already expressed as ratios (0–1) and therefore required no additional scaling. Missing values accounted for less than 2% of the total dataset and were imputed using domain-wise mean substitution within each variable group to preserve relative distribution patterns; sensitivity tests comparing imputed and complete-case models revealed negligible differences in model performance (ΔR2 < 0.01), confirming that imputation did not materially affect the results.

Potential multicollinearity was examined using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), with predictors exceeding conventional thresholds (VIF > 5) excluded or merged through PCA. Spatial dependence among parks was assessed using Moran’s I and Lagrange Multiplier diagnostics computed on OLS residuals and park centroids, indicating no significant spatial autocorrelation (p > 0.10). Residual diagnostics for the OLS models also suggested approximate normality and homoskedasticity. Together, these procedures ensured that data preprocessing, normalization, and spatial validation met standard statistical and spatial-analytic requirements prior to model estimation (Section 2.4 and Table 1).

It is important to acknowledge the strengths and limitations of the smartphone-based visitation data. SafeGraph point-of-interest records offer substantial advantages for capturing spatiotemporal dynamics, including rapid acquisition of large volumes of observations at fine temporal resolution, which enables near-real-time analysis of park use. However, these data inherently represent only individuals carrying location-enabled mobile devices, meaning certain groups such as young children, some elderly people, and individuals without smartphones or with location services disabled are likely underrepresented. This potential sampling bias is partly mitigated by the large number of observations and by the consistency of visitation patterns observed over multiple years, which enhance the statistical robustness of our findings. We therefore interpret the mobile-device data as complementary to, rather than a replacement for, traditional survey-based and observational methods: surveys can provide detailed demographic and attitudinal information, whereas large-scale mobility data capture revealed behavior across space and time. Integrating both approaches in future research would allow a more comprehensive understanding of urban park use and its social determinants. In this study, we proceed with explicit recognition of these representativeness considerations and focus on relative comparisons between neighborhoods and over time, under the assumption that any sampling biases are relatively uniform across the city.

2.4. Modeling Configuration and Validation

We employed two modeling techniques in parallel, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression and a Random Forest (RF) ensemble, to examine park visitation drivers [7,20]. The OLS model serves as a transparent linear benchmark in which standardized coefficients can be directly interpreted as marginal effects under the linearity assumption, while the RF model is a non-parametric ensemble of regression trees that can capture complex nonlinear relationships and interactions among predictors. Both models were specified using the same set of predictor variables described above, enabling a direct comparison of their performance and addressing RQ1. For RQ1 and RQ2, model estimation was conducted on the pooled 2019–2022 data.

For RQ3, we additionally re-estimated the RF models on each of the temporal subsets defined in Section 2.1 (pre-epidemic and post-epidemic), using identical preprocessing and model configurations for consistency. The response variable, weekly visits, was log-transformed or standardized if needed, and the visits_all_scaled metric was already normalized by the data provider [27,28]. All continuous independent variables were standardized with mean 0 and standard deviation 1 before modeling so that coefficient magnitudes and feature importance scores could be compared on a common scale.

For model training, the OLS models were fit in a standard linear regression framework including all candidate predictors simultaneously. For the Random Forest, we conducted a grid search to tune key hyperparameters and ultimately selected an ensemble of 500 trees with a maximum tree depth of 10 and a minimum of 2 samples required to split a node, because these values offered the best cross-validation performance [31,32,33,34]. The RF was run with bootstrap sampling and mean squared error as the splitting criterion, which is appropriate for regression.

To evaluate model performance and guard against overfitting, we implemented a grouped five-fold cross-validation strategy [31,32,33,34]. In each fold, data were partitioned so that all observations from a subset of parks were held out for testing, while the remaining parks were used for training. This park-grouped cross-validation ensured that the model was tested on entirely unseen parks in each fold and prevented information leakage that could occur if different weeks of the same park appeared in both training and test sets. We computed performance metrics including the coefficient of determination R2, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) on each fold’s predictions and reported the average across the five folds. Table 2 summarizes the training sample sizes and cross-validated performance for each model and research question. Overall, the RF models consistently outperformed the OLS models in predictive accuracy, with higher R2 and lower errors, suggesting that nonlinear interactions among the predictors substantially improve explanatory power [25,26,29,32,33,34]. The RF also maintained stable performance across the pooled and phase-specific subsets, indicating robustness over time. We further observed that the RF advantage over OLS was more pronounced in the post-pandemic period, which hints at more complex dynamics emerging after COVID-19 and is explored further in Section 3. All model development and validation steps were conducted using Python 3.12 scikit-learn and statsmodels libraries.

Table 2.

Model Training and Validation Summary.

2.5. Interpretability Methods

To ensure that the models’ results are interpretable and to uncover the mechanisms behind the observed patterns, we applied a suite of post hoc interpretability techniques to both the OLS and the Random Forest models [22,31,33,34]. Together, standardized OLS coefficients, RF feature-importance metrics, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values, and Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) plots provide complementary perspectives on the drivers of visitation inequalities, capturing both global contributions of predictors and local marginal effects and thresholds.

For the RF, we calculated two forms of feature importance: the default impurity-based importance (mean decrease in mean squared error for each variable) and a permutation-based importance as a robustness check [32,34]. Impurity-based importance reflects each feature’s contribution to reducing prediction error in the RF, although it does not directly indicate effect direction. The permutation importance was used to verify that no single predictor’s importance was grossly overstated due to potential biases in the impurity metric. All interpretability analyses were performed on standardized input variables so that comparisons between predictors are meaningful.

We applied the interpretability techniques in alignment with the three research questions. For RQ1 (overall effects), we identified the dominant predictors of park visitation by comparing standardized OLS coefficients with RF feature-importance rankings on the full dataset [29,30,32,33]. Statistically significant predictors in the OLS model (p < 0.05) were noted as having robust linear associations, while RF feature importance and SHAP values highlighted variables that contributed most strongly to predictive performance, including nonlinear and interaction effects.

For RQ2 (domain-level explanatory power), interpretability focused on evaluating how different predictor domains contribute to visitation disparities. Within each variable category, standardized OLS coefficients revealed the direction and relative magnitude of effects, whereas RF feature importance scores captured nonlinear contributions. SHAP and ALE plots derived from the pooled RF model illustrated how key variables within each domain influenced visitation dynamics under varying socio-environmental conditions, allowing us to compare the roles of socio-economic, environmental/health, housing, and infrastructural factors.

For RQ3 (temporal shifts in determinants), a hierarchical interpretability framework was adopted. Feature-importance scores were compared across pooled, pre-epidemic, and post-epidemic samples to identify shifts in predictor relevance over time. One-dimensional ALE plots illustrated phase-specific marginal relationships, while correlation analysis (|r| > 0.5, p < 0.05) was employed to screen variable pairs that potentially explained phase-specific variations and interactions. Taken together, this integrated interpretability framework provides a systematic basis for evaluating both individual and interacting effects, revealing how the mechanisms shaping urban park visitation evolved across pandemic phases and socio-environmental contexts.

3. Results

3.1. RQ1: Overall Effects

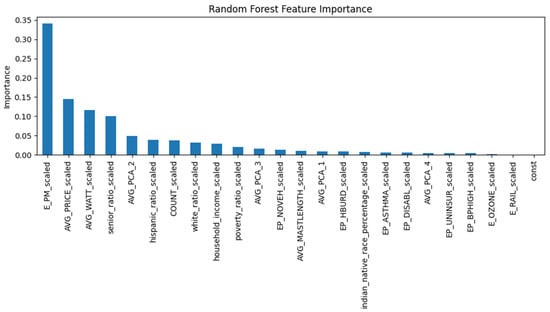

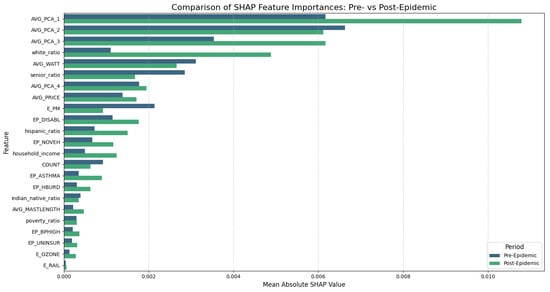

To evaluate to what extent the selected features collectively explain variations in park visitation preferences across Las Vegas, we trained both OLS and RF models on the same set of predictors for 2019–2022 and evaluated their performance using five-fold cross-validation. In each fold, models were fitted on four-fifths of the data and assessed on the held-out fifth, and the reported metrics summarize the mean out-of-sample performance across folds. The OLS model explained only a limited portion of the variance (mean out-of-sample R2 ≈ 0.26, RMSE = 0.066), whereas the RF model achieved substantially higher predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.81, MAE = 0.016) (Table 3). This performance gap indicates that nonlinear patterns and interaction effects are essential for capturing the underlying visitation dynamics. In the following subsections, SHAP value decompositions and Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) plots are used to more formally examine which predictors and nonlinear responses drive these gains. Significant differences in variable importance were observed between social and environmental predictors. (Figure 3) According to SHAP analysis, particulate matter (PM), average housing price, senior population share, and Hispanic ratio showed the strongest contributions. PM concentration significantly decreased visitation once it exceeded moderate levels, while housing price and senior share tended to increase visitation but with diminishing marginal returns. (Table 4). Quantitatively, the OLS results showed that senior population share (β = 0.11, p < 0.01) and Hispanic ratio (β = 0.06, p < 0.05) had significant positive associations with park visitation, whereas poverty rate (β = −0.10) exhibited a weak negative effect. Among environmental predictors, PM2.5 concentration (β = 0.16, p < 0.01) and ozone level (β = 0.04, p < 0.05) showed positive coefficients, likely reflecting the clustering of parks and activity centers in more urbanized areas rather than a direct health benefit. Proximity to rail infrastructure (β = −0.03) and high blood pressure prevalence (β = −0.05) were negatively related to visitation but statistically insignificant.

Table 3.

OLS and RF regression.

Figure 3.

Random Forest Feature importance.

Table 4.

Variable importance.

Feature importance results from the RF model corroborated these trends but emphasized different magnitudes of influence. To enhance transparency, we additionally report the mean absolute SHAP values and their 95% confidence intervals in Supplementary Table S1. PM2.5 concentration accounted for over one-third of total predictive importance, followed by average housing price, lighting wattage, and senior share. Social indicators such as Hispanic ratio and household income showed moderate contributions, while poverty and health exposure variables had smaller yet consistent effects. Taken together, these findings suggest that social and demographic factors primarily determine the direction of visitation differences, whereas environmental and infrastructural factors drive the magnitude of nonlinear variation across neighborhoods (Table 3; Figure 1).

3.2. RQ2: Group Explanatory Differences

To assess the relative explanatory capacity of different predictor domains, all variables were grouped into five conceptual categories: demographics, socio-economics, housing, environmental/health, and infrastructure/lighting.

Significant differences in model performance were observed across these groups (Table 4). The socio-economic group achieved the highest explanatory power, with an RF R2 of approximately 0.88, followed by housing (R2 = 0.70), environmental/health (R2 = 0.70), and infrastructure/lighting (R2 = 0.70). Demographic variables yielded the weakest performance (R2 = 0.39). (Table 5) Across all groups, RF models consistently outperformed OLS regressions, confirming that nonlinear relationships considerably improved predictive accuracy.

Table 5.

Variable group importance.

To identify the most influential variables, we first examined their statistical significance (p < 0.05) and multicollinearity (VIF < 5) in OLS regressions. Subsequently, SHAP values from the Random Forest model were used to rank and interpret variable importance within each predictor group. Within individual groups, several predictors showed distinct levels of influence (Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10). The uninsured ratio exhibited the strongest effect among socio-economic factors, while housing burden, vehicle ownership, PM, ozone, and streetlight wattage also contributed substantially to explaining visitation variation. Demographic indicators, such as the shares of senior and White populations, had comparatively weaker yet directionally consistent effects.

Table 6.

Demographics group importance.

Table 7.

Socio-economic factors group importance.

Table 8.

Housing factors group importance.

Table 9.

Environmental health factors group importance.

Table 10.

Lighting factors group importance.

Overall, socio-economic disparities accounted for the largest share of variation in park visitation, whereas environmental and infrastructural factors acted as secondary but reinforcing determinants. These findings highlight that social vulnerability rather than demographic composition alone served as the dominant explanatory mechanism of neighborhood-level visitation inequality during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the poverty ratio remained relatively stable across pre- and post-epidemic phases, indicating that the observed patterns were not affected by sample imbalance.

3.3. RQ3: Phase-Specific Mechanisms of Park Visitation

To clarify this pattern, we explicitly note that the shift from a U-shaped to a monotonic positive association for poverty reflects a consistent increase in visitation across the mid-to-upper range of observed poverty levels, rather than only at extreme values. This trend can be visually verified in the phase-specific ALE curves (Table 10), where the post-pandemic trajectory exhibits a continuous upward slope without a secondary turning point.

Significant differences in model performance were observed across phases. The explanatory power of the RF model increased from R2 = 0.84 before the pandemic to R2 = 0.87 after it, indicating that visitation patterns became more systematically associated with socio-economic and health-related characteristics (Table 11).

Table 11.

Model performance across time periods.

Marked shifts in variable importance were also identified. Before the pandemic, demographic and environmental factors, particularly senior population share, White/Hispanic ratios and PM concentration played dominant roles. After the pandemic, socio-economic and health burdens such as poverty, uninsured rate, and asthma prevalence became more influential, reflecting a structural reweighting toward social vulnerability as the principal driver of phase-specific visitation inequality.

Nonlinear effects captured by one-dimensional ALE plots revealed several turning points. Prior to COVID-19, visitation increased sharply when the senior share exceeded 0.55 and followed a U-shaped pattern with poverty. In the post-pandemic phase, poverty emerged as a monotonic positive driver, while PM’s negative effect flattened, suggesting weakened environmental constraints. The effective illumination threshold (streetlight wattage) decreased from approximately 20 to 15, implying reduced lighting sufficiency in the later phase.

Correlation analysis further demonstrated strengthened socio-economic × health interdependencies. High uninsured rates combined with elevated PM or asthma prevalence significantly suppressed visitation, particularly in socio-economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. Correlation matrices confirmed that interdependencies among poverty, uninsured, and disability rates intensified after the pandemic, revealing that compounded social and environmental disadvantages increasingly constrained park accessibility.

Overall, temporal heterogeneity in park visitation increased markedly after COVID-19, driven primarily by reinforced socio-economic and health vulnerabilities rather than demographic or purely environmental factors.

3.4. Accumulated Local Effects Analysis

3.4.1. One-Dimensional Marginal Effects

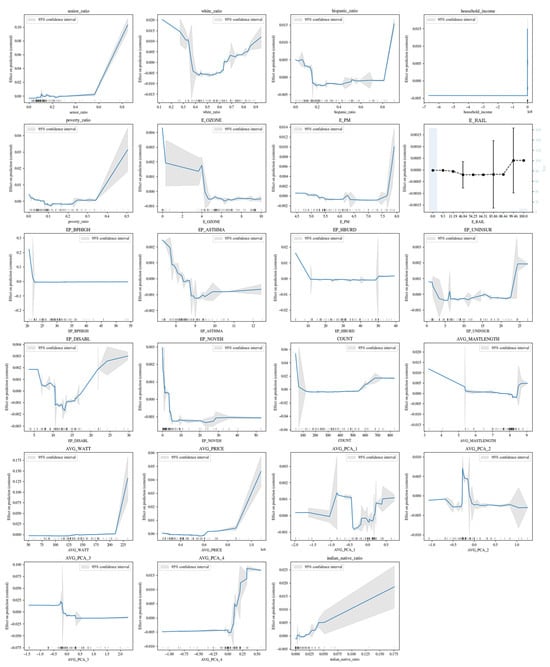

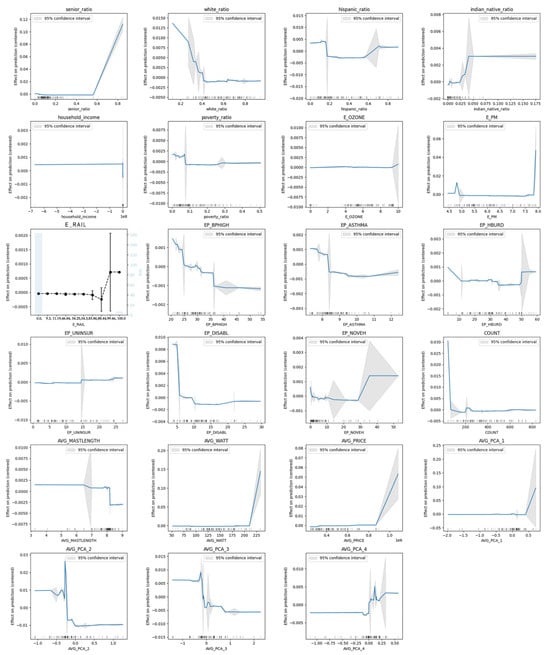

To further examine nonlinear marginal relationships, we first generated pooled one-dimensional ALE plots for all key predictors, providing an overview of demographic, socio-economic, environmental, and infrastructural responses. Figure 4 presents these pooled ALE curves, summarizing the overall nonlinear effects before distinguishing phase-specific patterns.

Figure 4.

Pooled one-dimensional accumulated local effects (ALE) of key predictors. Blue line—one-dimensional ALE effect of each predictor on the model output (centered at 0: positive/negative values indicate increase/decrease in prediction relative to the average). Gray band—95% confidence interval for the ALE curve. Black dots (with vertical error bars)—empirical bin-wise means of the model prediction with 95% CIs (equal-frequency bins), providing a distribution-aware check against the smooth ALE. Short tick marks along the x-axis show the data density.

As shown in Figure 4, several predictors exhibit clear nonlinear threshold behaviors—for example, senior population ratio and average lighting wattage show sharp increases beyond specific ranges, while environmental exposures such as PM and ozone reveal threshold-type declines or plateaus. These general patterns motivated a phase-specific comparison to understand how these relationships evolved across epidemic stages.

Figure 5 reveals a notable shift in importance: environmental and infrastructural predictors were more influential before the epidemic, whereas socio-economic characteristics, particularly demographic composition and poverty-related indicators, became increasingly important afterward. These shifts suggest changes in behavioral constraints and neighborhood dependencies during the recovery period.

Figure 5.

Comparison of SHAP Feature Importances: Pre- vs. Post-Epidemic.

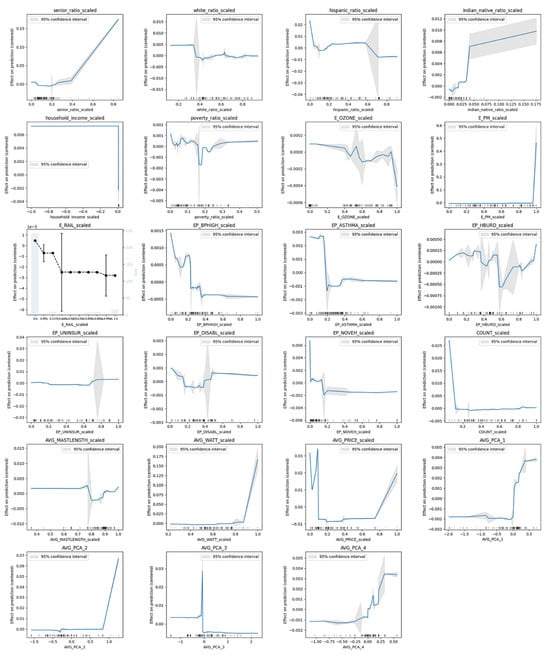

To investigate these shifts more closely, Figure 6 and Figure 7 provide phase-specific ALE plots, enabling a detailed comparison of nonlinear effects within each period.

Figure 6.

Pre-epidemic one-dimensional ALE effects for key predictors. Blue line—one-dimensional ALE effect of the predictor on the model output (centered at 0, so values above/below 0 indicate increasing/decreasing effect). Gray band—95% confidence interval for the ALE. Black dots—empirical bin-wise means of the model prediction (equal-frequency bins) with 95% CI error bars; these provide a distribution-aware check against the smooth ALE curve. Short tick marks along the x-axis show the data density for each predictor.

Figure 7.

Post-epidemic one-dimensional ALE effects for key predictors. Blue line: model-estimated effect of the feature on the prediction (centered at 0); gray band = 95% confidence interval. Black dots (with vertical bars): empirical bin-wise means of the model prediction with 95% CIs; they provide a distribution-aware check of the smooth effect. Rug marks/histogram indicate the density of feature values.

Before the epidemic (Figure 6), the senior ratio displayed a strong positive nonlinear effect once the share exceeded roughly 0.55, whereas this slope became flatter post-epidemic (Figure 7), indicating reduced advantage for senior-dominant neighborhoods. Poverty ratio shifted from a U-shaped pre-epidemic pattern to a monotonic positive relationship post-epidemic, implying more active park use among moderately disadvantaged areas after the crisis. Environmental drivers such as PM and ozone weakened substantially after the epidemic, with flatter or near-neutral slopes. Infrastructure-related predictors—especially lighting wattage—showed clearer thresholds pre-epidemic, while the effective threshold dropped sharply post-epidemic, suggesting that lower lighting levels became sufficient to support visitation. Overall, these patterns indicate that environmental and infrastructural influences were more pronounced before the epidemic, whereas socio-economic determinants became increasingly dominant afterward.

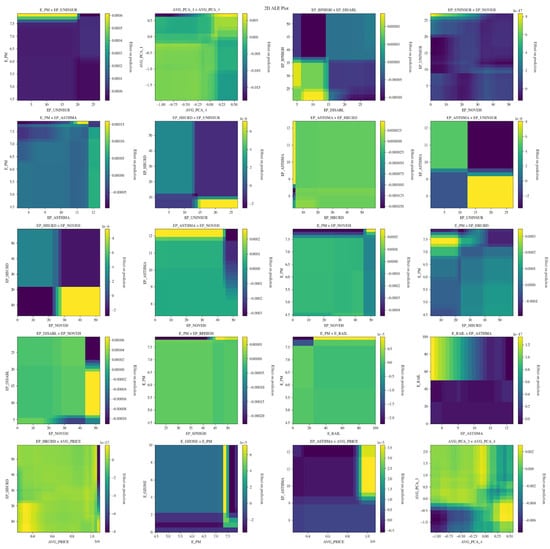

3.4.2. Two-Dimensional Marginal Effects

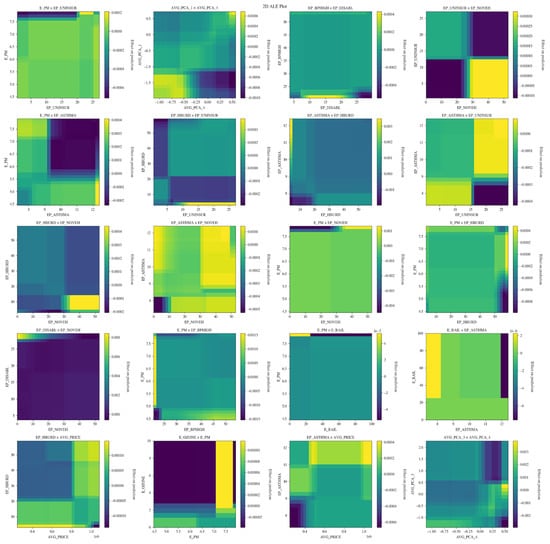

To capture joint nonlinear effects, we generated two-dimensional ALE plots for predictor pairs with significant correlations (|r| > 0.5, p < 0.05). Figure 8 presents the pooled 2D ALE surfaces, offering an overall view of how socio-economic, environmental, and infrastructural variables interact to shape visitation responses.

Figure 8.

Pooled two-dimensional ALE surfaces for key predictor pairs.

As shown in Figure 8, several interactions display clear nonlinear and suppressive zones. For example, jointly high PM concentrations and uninsured rates produced strong declines in visitation, while housing-burden × non-vehicle interactions showed intensified negative effects at higher joint levels. These pooled patterns indicate that many cross-domain interactions particularly socio-economic × environmental and socio-economic × mobility factors play substantial roles in shaping park accessibility.

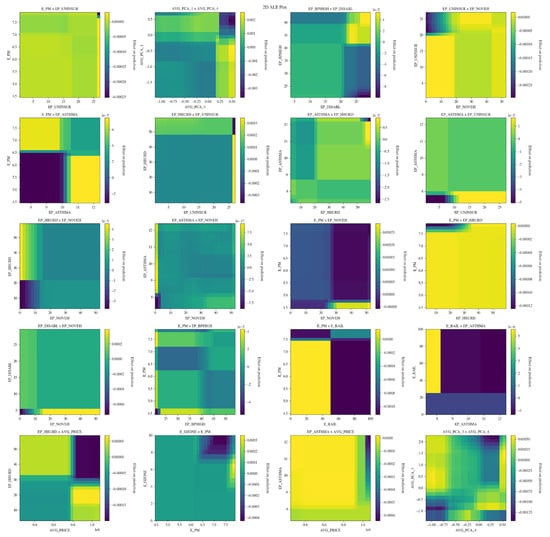

To examine whether these patterns evolved across epidemic phases, Figure 9 and Figure 10 provide phase-specific 2D ALE surfaces, allowing us to compare pre- and post-epidemic interaction structures.

Figure 9.

Pre-epidemic two-dimensional ALE surfaces for key predictor pairs.

Figure 10.

Post-epidemic two-dimensional ALE surfaces for key predictor pairs.

Before the epidemic (Figure 9), jointly elevated pollutant concentrations produced broad declines in visitation, while socio-economic × health interactions—such as high asthma prevalence combined with high uninsured rates—exhibited strong nonlinear suppressive zones. After the epidemic (Figure 10), these effects became more spatially localized: environmental interactions weakened overall, whereas socio-economic × financial stress couplings (e.g., housing burden × uninsured ratio) intensified markedly. Disability paired with poverty or low vehicle access remained consistently negative across both phases, though with reduced magnitude after the epidemic.

After the epidemic, interaction patterns changed considerably. Figure 10 presents the post-epidemic 2D ALE surfaces, allowing direct comparison with the pre-epidemic interaction structures.

Post-epidemic interactions became more spatially localized and generally weaker for environmental drivers. The joint influence of PM and ozone contracted into smaller, less intense suppressive zones. In contrast, socio-economic × financial stress interactions intensified: housing burden combined with high uninsured rates generated sharper and more concentrated declines. Disability paired with poverty or limited vehicle access remained consistently negative but exhibited reduced magnitude, suggesting partial behavioral adaptation during recovery.

Collectively, these results highlight that epidemic-induced behavioral shifts were not limited to single-variable effects but were reinforced through cross-domain interactions, particularly socio-economic × health and socio-economic × environmental couplings, which became increasingly decisive in shaping post-epidemic park visitation patterns.

4. Discussion

This study shows that inequalities in park visitation during and after COVID-19 in Las Vegas arose from the interaction of social, environmental, and infrastructural factors rather than from any single driver [2,3,20,22,23,25]. Socio-economic indicators especially poverty, uninsured rates, and housing burden were consistently the most influential predictors [25,32,33,41], indicating that economic and health vulnerability shaped residents’ capacity to engage in outdoor recreation more strongly than environmental conditions alone [1,2,20,23]. As restrictions eased, these social and health disadvantages became even more decisive, suggesting a relative reweighting toward social vulnerability rather than a complete shift from environmental to social exclusion [11,23,32]. In other words, the post-pandemic pattern reflects a reordering of mechanisms that were already present before COVID-19.

The transformation of poverty from a U-shaped relationship with visitation in the pre-pandemic period to a monotonic positive association afterward illustrates a constraint-driven adaptation process. When other leisure opportunities were curtailed, residents in lower-income neighborhoods appear to have relied more heavily on nearby parks as one of the few affordable and accessible public amenities [10,13,36,37]. This should not be interpreted as improved equity, because increased use is driven by limited choice rather than by expanded opportunities [22,23,41]. Similarly, the apparent attenuation of PM2.5 and ozone effects does not imply that environmental inequalities disappeared. Instead, it likely reflects selective behavioral responses and changing mobility patterns, whereby some residents curtailed trips during pollution peaks, avoided certain locations, or concentrated visitation in parks perceived as safer and more usable [11,18,19,23]. In this sense, social vulnerability, mobility constraints, and differences in park usability may interact with environmental risk in ways that partially obscure its direct statistical signal rather than canceling environmental inequality [25,32,42].

Infrastructure findings reinforce this perspective. The lower street-lighting threshold associated with visitation in the post-pandemic phase suggests evolving perceptions of safety or increased tolerance for outdoor activity under constrained conditions, potentially shaped by both behavioral habituation and municipal upgrades [26,27,34]. Such nonlinear responses highlight how physical design interacts with social context to mediate environmental comfort and perceived security [27,42]. Together, these patterns portray park use as the outcome of layered constraints economic, health-related, environmental, and infrastructural—rather than a simple response to any single factor. The Random Forest models are well suited to capturing these nonlinear associations and thresholds but do not establish causality [34,37,43]; accordingly, the identified mechanisms should be viewed as empirically grounded hypotheses for future causal investigation into how crises redistribute the relative influence of social versus environmental determinants of outdoor behavior [3,11,20,22,25].

The results broadly align with international evidence showing that COVID-19 substantially altered park-use dynamics. Consistent with previous studies, Las Vegas experienced an initial sharp decline in visitation followed by a partial recovery as residents sought outdoor alternatives to restricted indoor spaces [3,4,43]. Similarly to findings from Shenzhen and several U.S. metropolitan areas, socio-economic disadvantage particularly poverty burden and lack of health insurance—emerged as the strongest driver of uneven recovery, confirming that communities with limited health coverage and financial resilience were disproportionately constrained in accessing green spaces [11,13]. By extending the analysis over multiple years (2019–2022), this study adds evidence that these inequalities were not transient but persisted well beyond the early pandemic period. Methodologically, the combination of OLS and interpretable Random Forest models advances prior work by revealing nonlinear thresholds such as particulate matter inflection points, declining lighting wattage requirements, and the poverty U-to-positive transition that are unlikely to be detected in purely linear models.

The findings also contribute to ongoing debates in environmental justice and resilience theory. In contrast to earlier work that emphasized air quality as a principal constraint on outdoor activity, the diminished influence of PM and ozone after COVID-19 indicates a behavioral reordering in which weakened social safety nets and heightened financial stress can outweigh environmental conditions in shaping park use [41]. At the same time, the observed increases or stability in visitation among some moderately disadvantaged neighborhoods suggest that social disadvantage does not uniformly suppress outdoor activity. Under prolonged crisis conditions, certain communities may adapt by repurposing nearby parks as accessible refuges, illustrating how adaptive behaviors can emerge from structural inequality and become part of urban resilience dynamics [11,20,25]. These insights underline that resilience and vulnerability are co-produced: the same socio-economic constraints that limit options can also drive creative forms of adaptation, but often at the cost of reinforcing underlying exposure to risk.

From a theoretical perspective, the study strengthens the argument that socio-economic and infrastructural factors mediate how environmental opportunities are realized during public health crises. The consistent dominance of socio-economic predictors across models and phases, together with the changing roles of environmental and lighting variables, suggests that resilience frameworks need to account for evolving interactions between social vulnerability and environmental quality [6,25,32]. The integrated use of OLS and interpretable machine learning demonstrates the value of combining transparent linear estimates with flexible nonlinear tools to visualize behavioral thresholds and risk conditions across neighborhoods, offering a template for future urban analytics.

Practically, the results highlight the need for equity-oriented park and urban planning strategies that explicitly target socially vulnerable neighborhoods. Improving infrastructure and lighting safety, enhancing affordable healthcare access, and aligning green-infrastructure investments with social vulnerability indicators are essential steps to ensure that environmental improvements translate into equitable behavioral benefits rather than reinforcing pre-existing disparities. Incorporating composite measures of social vulnerability and health burden into park planning and recovery frameworks would help prioritize interventions in communities where constraints on outdoor activity are most acute. In the longer term, integrating mobility data, environmental monitoring, and community-based knowledge can support more responsive and inclusive green-infrastructure policies.

At the same time, several limitations should be acknowledged. Smartphone-based SafeGraph data may underrepresent children, seniors, and low-income individuals with limited digital access, which could bias visitation estimates toward more connected populations. The classification of parks based on commercial POI metadata may not perfectly align with official park boundaries, and Random Forest models capture associations rather than causal effects. In addition, the analysis focuses on Las Vegas, a desert metropolis with distinctive socio-environmental conditions, so results may not generalize directly to temperate or coastal cities. Future research should therefore combine mobility traces with survey-based perceptions, apply causal inference frameworks such as double machine learning or spatial panel models, and extend the analytical framework to multi-city comparisons and longer post-pandemic periods to assess whether the behavioral inequalities documented here persist, widen, or gradually converge.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study used multi-year SafeGraph mobility data for 182 parks in Las Vegas (2019–2022) combined with Ordinary Least Squares and interpretable Random Forest models to examine how socio-economic, environmental, and infrastructural factors shape inequalities in park visitation before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The comparison between model types shows that nonlinear machine-learning methods explained spatial variation in visitation substantially better than linear regression (RF R2 ≈ 0.81 vs. OLS R2 ≈ 0.24), confirming Hypothesis 1 and answering RQ1 by demonstrating that interpretable machine learning captures combined socio-environmental effects more effectively than a linear benchmark.

Across predictor domains, socio-economic vulnerability indicators especially poverty, uninsured rates, housing burden, and health-related burdens consistently exhibited the strongest contributions to explaining neighborhood differences in park use, while environmental exposures and lighting conditions played secondary but reinforcing roles. These findings answer RQ2 and strongly support Hypothesis 2: social and health disadvantages, rather than demographic composition or physical infrastructure alone, were the primary drivers of uneven visitation during the study period.

Phase-specific analyses further reveal that, after the onset of COVID-19, park visitation patterns became more tightly coupled with socio-economic and health characteristics. Poverty changed from a U-shaped to a monotonic positive association with visits, indicating constraint-driven reliance on nearby parks in disadvantaged neighborhoods, whereas the influence of PM2.5, ozone, and lighting thresholds weakened but did not disappear. This pattern answers RQ3 and provides partial support for Hypothesis 3: social and health-related burdens became more salient after the pandemic, but environmental conditions and infrastructure continued to modulate park accessibility. Overall, the results show that pandemic-related inequalities in park visitation were structurally persistent and underscore the need for recovery strategies that prioritize socially vulnerable neighborhoods while improving environmental quality and basic green-infrastructure provision.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/urbansci9120545/s1, Table S1.: Mean absolute SHAP values and 95% confidence intervals.

Author Contributions

Writing—review and editing, S.H., Z.Z. and B.L.; writing—original draft, S.H., Z.Z. and B.L.; visualization, S.H. and Z.Z.; software, S.H. and Z.Z.; methodology, S.H. and Z.Z.; data curation, S.H., Z.Z. and B.L.; conceptualization, S.H., Z.Z. and B.L.; supervision, B.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to licensing restrictions from the data providers and therefore cannot be shared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ge Wang for his kind guidance. We also acknowledge Bofan Li and Lu Cao from the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts for their collaboration and support during the early stage of this research. The authors used OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-5, web interface; accessed in March–October 2025) solely to assist with grammar checking, wording clarity, and stylistic consistency of the manuscript. No sections involving study conception, data processing, statistical analysis, modeling, interpretation, or conclusions were generated by the tool. No proprietary or personal data were entered into the system. All AI-assisted suggestions were reviewed and approved by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Urban Green Spaces and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://blogs.ubc.ca/2017wufor200/files/2017/01/Urban-Green-Spaces-and-Health-WHO-2016.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wilson, B.; Neale, C.; Roe, J. Urban green space access, social cohesion, and mental health outcomes before and during COVID-19. Cities 2024, 152, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Mailloux, B.J.; Cook, E.M.; Culligan, P.J. Change of urban park usage as a response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, D.C.; Innes, J.; Wu, W.; Wang, G. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on urban park visitation: A global analysis. J. For. Res. 2020, 32, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jay, J.; Heykoop, F.; Hwang, L.; Courtepatte, A.; de Jong, J.; Kondo, M. Research Note: Use of Smartphone Mobility Data to Analyze City Park Visits during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 228, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Ignatieva, M.; Konstantinova, A.; Vasenev, V.; Dovletyarova, E.; Dvornikov, Y. Human-Nature Interactions during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic in Moscow, Russia: Exploring the Role of Contact with Nature and Main Lessons from the City Responses. Land 2022, 11, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bherwani, H.; Indorkar, T.; Sangamnere, R.; Gupta, A.; Anshul, A.; Nair, M.M.; Singh, A.; Kumar, R. Investigation of Adoption and Cognizance of Urban Green Spaces in India: Post COVID-19 Scenarios. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 3, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Das, M.; Saha, S.; Pereira, P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on cultural ecosystem services from urban green spaces: A case from English Bazar Urban Agglomeration, Eastern India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 65933–65946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, S.; Catania, P.; Greco, C.; Ferro, M.V.; Vallone, M.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G. Rural Landscape Transformation and the Adaptive Reuse of Historical Agricultural Constructions in Bagheria (Sicily): A GIS-Based Approach to Territorial Planning and Representation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz Kiraz, L.; Ward Thompson, C. How Much Did Urban Park Use Change under the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Comparative Study of Summertime Park Use in 2019 and 2020 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J. A quasi-experimental analysis on the causal effects of COVID-19 on urban park visits: The role of park features and the surrounding built environment. Urban For. Urban Green 2023, 82, 127898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Cai, Y.; Wen, Y.; Niu, J.; Chen, M. Assessing the Association Between Urban Amenities and Urban Green Space Transformation in Guangzhou. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadehtazi, B.; Tangtrakul, K.; Woerdeman, S.; Gussenhoven, A.; Mostafavi, N.; Montalto, F.A. Urban Park Usage During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Extrem. Events 2020, 07, 2150008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayen Huerta, C.; Cafagna, G. Snapshot of the Use of Urban Green Spaces in Mexico City during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, C.; Zhao, Q.; Myint, S.W. A Geographically Weighted Regression Approach to Understanding Urbanization Impacts on Urban Warming and Cooling: A Case Study of Las Vegas. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billot, Z. Biodiversity Loss & Urban Heat: A Nature-Based Wildlife Policy for the Las Vegas Metro. UNLV Digital Scholarship Repository; University of Nevada, Las Vegas. 2024. Available online: https://oasis.library.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=brookings_capstone_studentpapers (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Larson, L.R.; Zhang, Z.; Oh, J.I.; Beam, W.; Ogletree, S.S.; Bocarro, J.N.; Lee, K.J.; Casper, J.; Stevenson, K.T.; Hipp, J.A.; et al. Urban Park Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Are Socially Vulnerable Communities Disproportionately Impacted? Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 710243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X. Analyzing Urban Infrastructure and Long-Term User Experience. 2025. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1566253524006924 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Bristowe, A.; Heckert, M. How The COVID-19 Pandemic Changed Patterns of Green Infrastructure Use: A Scoping Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 81, 127848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschroth, F.; Savilaakso, S.; Kowarik, I.; Martinez, P.J.; Chang, Y.; Jakstis, K.; Schneider, J.; Fischer, L.K. Global disparities in urban green space use during the COVID-19 pandemic from a systematic review. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoltek, G. North Las Vegas Has a 3% Tree Canopy, the City is Working to Fix That. Channel 13 Las Vegas News KTNV. 2025. Available online: https://www.ktnv.com/news/north-las-vegas-has-a-3-tree-canopy-the-city-is-working-to-fix-that (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Gao, S.; Zhai, W.; Fu, X. Green space justice amid COVID-19: Unequal access to public green space across American neighborhoods. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1055720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-G.; Park, C.; Seo, J.-Y.; Choi, H. Erratum to: User Hot Spots of Urban Parks Identified Using Mobile Signaling Data—A Case Study of Seongdong-Gu, Seoul-. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 51, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, A.; Yang, Z.; Chen, M.; Wen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, X. Subjective Perception or the Physical Environment: Which Matters More for Public Area Visitation Thresholds across Different COVID-19 Pandemic Stages? Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 109, 128835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brelsford, C.; Moehl, J.; Weber, E.; Sparks, K.; Tuccillo, J.V.; Rose, A. Spatial and Temporal Characterization of Activity in Public Space, 2019–2020. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owuor, I.; Hochmair, H.H. Use of SafeGraph visitation patterns for the identification of essential services during COVID-19. Agil. GIScience Ser. 2023, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Huang, Y.; Zawarus, P.; Kong, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L. Explore a sustainable development education (ESD) framework of planting and environmental design based on the Barriers of Knowledge Dissemination between Academia and practice. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 3248–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Community park visits determined by the interactions between built environment attributes: An explainable machine learning method. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 172, 103423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Kang, J.; Hsu, C.-H.; Shoji, Y.; Kubo, T. Day-night visitor usage of urban parks: Exploring temporal dynamics and driving factors through mobile phone big data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 107, 128818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnell, K.; Fudolig, M.; Bloomfield, L.; McAndrew, T.; Ricketts, T.H.; O’Neil-Dunne Jarlath, P.M.; Dodds, P.S.; Danforth, C.M. Park visitation and walkshed demographics in the United States. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cai, Y.; Shen, X. Integrating Machine Learning, SHAP Interpretability, and Deep Learning Approaches in the Study of Environmental and Economic Factors: A Case Study of Residential Segregation in Las Vegas. Land 2025, 14, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csomós, G.; Borza, E.M.; Farkas, J.Z. Exploring park visitation trends during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary by using mobile device location data. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wei, E.; Cai, X. Empathy and redemption: Exploring the narrative transformation of online support for mental health across communities before and after COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Du, J.; Chen, M.; Lin, Y.; Huang, S.; Cai, Y. Evaluating the spatial-temporal impact of urban nature on urban vitality in Vancouver: A social media and GPS data approach. Land Use Policy 2025, 160, 107824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Zhu, Y.; Deal, B. Did COVID-19 Reshape Visitor Preferences in Urban Parks? Investigating Influences on Sentiments in Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cai, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cai, X. Assessing the Influence of Urban Scene Characteristics on Urban Heat Island: An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach in New York City. Urban Clim. 2025, 62, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhai, W. The Effect of Built Environment on Urban Park Visits during the Early Outbreak of COVID-19. Findings 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W.L.; Pan, B. Understanding changes in park visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A spatial application of big data. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matasov, V.; Vasenev, V.; Matasov, D.; Dvornikov, Y.; Filyushkina, A.; Bubalo, M.; Nakhaev, M.; Konstantinova, A. COVID-19 pandemic changes the recreational use of Moscow parks in space and time: Outcomes from crowd-sourcing and machine learning. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 83, 127911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, K.; Luo, J.; Cai, Y.; Aschebrook-Kilfoy, B. Long-term PM2.5 exposure and mental health disparities: A prospective analysis of the All of Us Research Program. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfin, A.; Hansen, B.; Lerner, J.; Parker, L. Reducing Crime Through Environmental Design: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment of Street Lighting in New York City. J. Quant. Criminol. 2021, 38, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, J.; Sternudd, C.; Johansson, M. “In the evening, I don’t walk in the park”: The interplay between street lighting and greenery in perceived safety. URBAN Des. Int. 2020, 26, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cai, Y.; Guo, S.; Sun, R.; Song, Y.; Shen, X. Evaluating Implied Urban Nature Vitality in San Francisco Using Census Data, Street-View Images and Social-Media Activity. 2024. Available online: https://mingzechen.com/publications/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).