Abstract

Climate change poses increasing risks to the ecological and social foundations of Nature-Based Tourism (NBT), particularly within urbanized and protected landscapes. This study examines how the existing literature conceptualizes climate vulnerability and resilience across Urban Protected Areas (UPAs) and Natural Protected Areas (NPAs), addressing an identified gap in comparative NBT scholarship. Using a semi-systematic literature review of 72 peer-reviewed studies published between 2010 and 2025, guided by PRISMA procedures, the analysis synthesizes conceptual framings, methodological orientations, and thematic trends across ecological, social, and demographic dimensions. Results reveal a persistent geographical bias toward the Global North and a strong emphasis on NPAs (67%), where resilience is primarily understood as an ecological or governance attribute. In contrast, UPA studies increasingly adopt participatory, health-adaptive, and accessibility-oriented approaches, though only about 10% explicitly consider aging populations. Comparative synthesis highlights distinct methodological preferences and a continued underrepresentation of health, well-being, and equity dimensions within current adaptation frameworks. The literature indicates that advancing climate-resilient tourism depends on hybrid models that link urban innovation, ecosystem restoration, and inclusive governance. Integrating regenerative tourism principles, traditional ecological knowledge, and health-adaptive infrastructure emerges as a promising direction for promoting socially equitable and ecologically robust adaptation strategies in protected areas affected by accelerating climate change.

1. Introduction

As one of the world’s fastest-growing industries, nature-based tourism (NBT) plays a pivotal role in linking biodiversity conservation with sustainable development, providing vital sources of conservation financing, supporting local livelihoods, and promoting environmental education [1,2,3,4]. A significant portion of NBT occurs within urban protected areas (UPAs) and natural protected areas (NPAs), each serving as a key interface between ecological conservation and human well-being. These areas support biodiversity conservation and deliver essential ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration, water regulation, and recreation [5,6,7]. However, increasing climatic variability and anthropogenic pressures are transforming the ecological and social dynamics of these landscapes, demanding a more integrated understanding of how vulnerability and resilience are conceptualized and assessed across diverse spatial and demographic contexts [8,9].

Both UPAs and NPAs play an essential role in supporting human health and well-being by providing spaces for recreation, social interaction, and exercise [10,11]. Access to natural environments contributes not only to physical activity but also to emotional stability, social connection, and cognitive restoration. Yet, these benefits are not evenly distributed, as demographic changes, particularly the growing proportion of older adults among tourists and local populations, affect exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity [12]. Persistent challenges, including restricted access, inadequate infrastructure, and environmental degradation, limit participation, particularly among vulnerable groups such as older adults and people with disabilities [13]. Consequently, adapting NBT management to evolving climatic and demographic realities has become both an ecological necessity and a social justice imperative

Despite increasing scholarly attention to these issues, the literature on vulnerability and resilience assessments in NBT remains conceptually fragmented and methodologically diverse. Existing studies employ a wide array of frameworks and indicators, ranging from biophysical and modeling approaches to participatory and indicator-based assessments, with limited integration across ecological and social domains [14,15,16]. This fragmentation hinders comparability and limits the development of evidence-based and policy-relevant frameworks for resilience assessment in protected area management [17].

To address these shortcomings, this study seeks to conduct a semi-systematic review of peer-reviewed literature to examine how vulnerability and resilience are conceptualized and operationalized within NBT research across UPAs and NPAs. While UPAs are primarily characterized by vulnerabilities associated with population density, infrastructure pressures, and heat exposure, NPAs face challenges driven by ecological sensitivity, climatic variability, and biodiversity loss [18,19]. By juxtaposing these two contexts, the study develops an integrative analytical framework that links ecological and socio-demographic resilience, thereby advancing a comparative perspective on climate adaptation in protected areas. Both UPAs, oriented toward human well-being, and NPAs, focused on ecological conservation [20], share a common imperative to adapt to climatic stressors that threaten environmental quality, ecosystem services, and tourism sustainability.

Accordingly, this review is guided by four key research questions, formulated in relation to the existing literature:

- How are climate vulnerability and resilience conceptualized in the literature within the framework of NBT under changing climate conditions?

- What methods, indicators, and frameworks have been applied in the literature to assess socio-ecological dimensions regarding climate shifts in UPAs versus NPAs?

- To what extent do current literature approaches integrate human health, well-being, and aging considerations within NBT assessments?

- What conceptual and methodological gaps remain, and how might future frameworks advance inclusive, climate-resilient management of protected areas?

By addressing these questions, the paper aims to contribute a comparative, demographically sensitive synthesis of how vulnerability and resilience are conceptualized in NBT scholarship. Although recent studies increasingly link climate adaptation, tourism, and human health, explicit integration of aging and equity dimensions remains limited. This study therefore provides a novel conceptual synthesis that informs adaptive governance and policy innovation, aligning conservation and public health objectives with the context of accelerating climate change.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Interplay Between Climatic Shifts and Socio-Ecological Systems

Nature plays a fundamental role in sustaining human well-being, as emphasized by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [21], which classified ecosystem services (ES) into provisioning (food and water supply), regulating (climate, disease control), supporting (formation, nutrient cycle, pollination), and cultural categories (tourism, spiritual enrichment). Among these, Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES), which represent the non-material benefits gained from nature, highlight the intrinsic values and experiences that contribute to human quality of life [22]. As a subset of CES, NBT takes place in natural and urban environments, relying on a full spectrum of ecosystem services. Typically, rural areas host NPAs such as national parks, wilderness areas, and marine reserves. In these areas, management priorities center on biodiversity protection and habitat integrity, often requiring strict visitor regulation. In contrast, urban NBT occurs in city parks, botanical gardens, urban reserves, and green belts, components of urban green and blue (water) infrastructure that provide accessible opportunities for recreation, education, and psychological restoration [20]. Although situated within densely populated regions, many UPAs are formally protected and function as critical spaces that enhance both ecological quality and human well-being.

Climate change poses systemic threats to economic and ecological foundations of NBT. Protected areas, whether UPAs or NPAs, are increasingly exposed to intensified climatic hazards, altered ecosystems, and shifting visitor dynamics [23,24]. Tourism-dependent destinations face challenges from extreme weather events, changing seasonality, biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation, which collectively threaten both visitor experiences and conservation objectives [25,26,27,28]. Addressing these challenges requires understanding resilience as a dynamic property of coupled social–ecological systems, reflecting the capacity to anticipate, absorb, and recover from disturbances while maintaining essential functions [29]. Recognizing socio-ecological systems as integrated systems of people and nature, Folke et al. [30] underscore the necessity of cross-disciplinary approaches that integrate ecological, social, and demographic perspectives [31].

The demographic transition toward population aging represents a defining challenge of the twenty-first century. Globally, the number of people aged 60 years or older is projected to more than double, from 761 million in 2021 to 1.6 billion by 2050, significantly expanding the share of older adults in societies worldwide [32]. Older adults gain significant enjoyment and satisfaction from experiencing nature through observing, being in, and interacting with natural environments, which positively contributes to their well-being and overall quality of life [33]. Evidence indicates that elderly visitors to UPAs and NPAs experienced improved mood, reduced loneliness, and enhanced motivation for low-intensity outdoor exercise [34,35,36]. Exposure to nature has also been linked to lower levels of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress [37,38]. However, these benefits are not automatically realized, as accessibility barriers, inadequate infrastructure, and increased exposure to climatic stressors may limit participation among older and vulnerable groups.

Exploring the resilience of NBT in UPAs and NPAs through the lens of demographic aging is therefore critical for advancing climate adaptation, risk management, and policy interventions that jointly address conservation, health, and well-being objectives [12,25].

2.2. Cross-Disciplinary Knowledge for Strengthening NBT Resilience

Climate vulnerability and climate resilience are closely interconnected concepts that together shape how social, ecological, and socio-ecological systems respond to climate-related stressors. Vulnerability refers to the degree to which a system is exposed, sensitive, and unable to cope with adverse climatic impacts, while resilience describes the system’s capacity to absorb disturbances, adapt to change, and reorganize without losing essential functions [39]. Higher levels of vulnerability typically indicate limited adaptive capacity, making systems more susceptible to climate shocks, whereas resilience reflects the mechanisms (social, economic, institutional, and ecological) that reduce vulnerability over time. Rather than opposing forces, vulnerability and resilience are complementary analytical lenses that together illuminate system weaknesses and adaptive strengths under climatic uncertainty.

Protected areas operate as coupled social–ecological systems, where resilience emerges from the interplay between ecological feedback, governance structures, and community engagement [8]. In UPAs, resilience mechanisms often depend on infrastructure adaptation, emergency response networks, and community-based planning that enhance preparedness and recovery during climate extremes such as heatwaves or flooding [40]. In contrast, NPAs rely more heavily on ecosystem-based approaches like biodiversity management, habitat connectivity, and landscape restoration to maintain ecological integrity and long-term adaptive potential [41].

Because tourism constitutes a major socio-economic driver in both urban and rural contexts, ensuring its resilience requires strengthening institutional capacity, improving governance, and securing financial resources for adaptation and learning [42]. This includes establishing mechanisms that safeguard natural resources while supporting human health and safety. In the tourism sector, resilience manifests through robust infrastructure [43], flexible operational practices [44], and institutional and social learning [45].

Integrating demographic and health considerations into resilience frameworks is critical for equitable adaptation [46]. Adaptive capacity is often unevenly distributed, with vulnerable and marginalized groups, such as older adults, facing financial, physical, or information resource challenges [47]. Age-sensitive strategies such as shaded walkways and hydration stations, guided tours and adaptive scheduling, or the provision of on-site medical support could significantly improve visitor safety and inclusivity. By linking ecosystem preservation with human health outcomes, protected areas can strengthen socio-ecological resilience across scales [48,49,50]. Additionally, economic valuation of ecosystem services and adaptation measures allows for quantifying the costs of inaction and the benefits of resilience-building investments [51].

Ultimately, fostering resilience in NBT requires an integrated approach that connects ecological management, social equity, adaptive governance, and sustainable financing. Despite a growing body of literature addressing these issues, comparative analyses between UPAs [52,53] and NPAs [54,55] remain rare, particularly regarding the integration of aging and health within resilience assessments. According to Ostrom [17], integrating multiple knowledge domains within a shared analytical framework enhances ability to explain the degradation of natural resources and ecosystem services, especially in complex socio-ecological systems (SES). Building on this perspective, the present review synthesizes existing knowledge on NBT vulnerability and resilience to inform adaptive strategies that promote the safety, health, and inclusivity of older visitors [30].

2.3. Applied PRISMA Methodology for a Semi-Systematic Literature Review

This study adopts a semi-systematic literature review following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [56] to identify, evaluate, and synthesize peer-reviewed research on vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation in NBT in UPAS and NPAs. The review focuses on comparing conceptual and methodological approaches to assessing climate-related risks and adaptive capacities that support health considerations regarding elderly visitors. A semi-systematic design was chosen to combine the methodological transparency of synthetic reviews with the flexibility required to integrate conceptual, theoretical, and policy-oriented studies, which are often excluded from fully systematic protocols.

The PRISMA-based protocol ensured transparency and replicability throughout the selection process, capturing studies published in the selected period in relevant databases. To ensure comprehensive disciplinary coverage, both the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases were used. Recent studies identify WoS as the most widely applied bibliometric source due to its rigorous indexing standards and extensive coverage of tourism, climate change, and environmental management journals [57,58,59]. WoS, integrating references from over 22,000 peer-reviewed journals, ensures the inclusion of high-impact, quality-controlled literature [60]. Scopus was incorporated to enhance disciplinary diversity and minimize database bias. Grey literature was excluded due to the absence of peer review and inconsistent methodological standards, ensuring reliability and comparability of the analyzed sources.

3. Materials and Methods

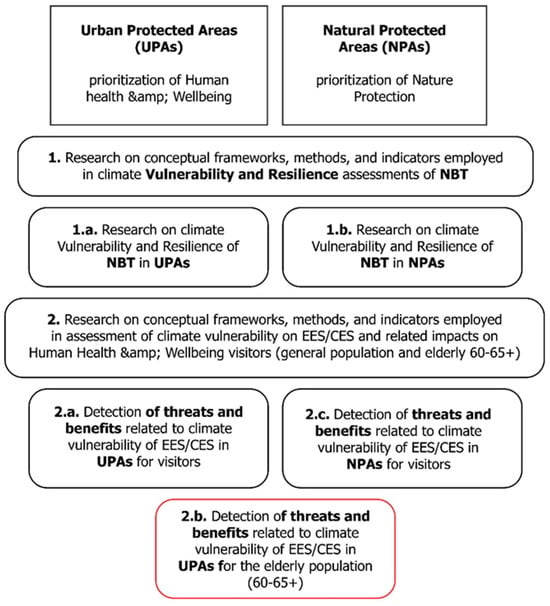

To identify studies relevant to the scope of this research, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology was applied as a structured and transparent approach to literature screening and selection. The analytical design of the review was structured around two interrelated components that guided data extraction and synthesis (Figure 1). The first component focused on assessing how climate vulnerability and resilience are defined and operationalized in NBT, distinguishing between UPAs, where social, infrastructural, and health-related factors strongly influence adaptive capacity, and NPAs, where emphasis is placed on ecological sensitivity, biodiversity-dependent recreation, and conservation-based resilience strategies. The second component examined how climate change affects ES and CES and their implications for human health, well-being, and aging populations. This involved identifying context-specific risks and benefits, such as accessibility constraints, changes in scenic or recreational quality, and adaptive responses among older visitors across UPAs and NPAs. Together, these two components provide the conceptual foundation for the analytical framework developed in the following section, enabling a comparative and integrative assessment of climate vulnerability, resilience, and socio-demographic well-being within diverse NBT contexts. Through this structured approach, the final dataset represents the most relevant, peer-reviewed, and thematically aligned evidence base available for synthesis.

Figure 1.

Methodological design of the semi-systematic review: comparative analytical components and key dimensions.

The 2010–2025 timeframe was selected because scholarship on climate vulnerability, resilience, aging populations, and nature-based tourism underwent substantial conceptual and methodological development after 2010. Research published during this period reflects contemporary understandings shaped by the IPCC AR5 (2014) [29,61], AR6 (2021–2022), the Paris Agreement (2015), and the SDGs [62]. In contrast, pre-2010 literature frequently relies on outdated terminology and fragmented frameworks that limit comparability. Additionally, empirical work on nature-based tourism, older-adult mobility, regenerative tourism, and climate-sensitive destination management expanded considerably from 2010 onward, creating a methodologically coherent body of evidence suitable for semi-systematic synthesis. This 15-year span ensured inclusion of both foundational and contemporary literature, reflecting the evolution of conceptual frameworks, methodological innovations, and increasing attention to human health and aging in climate-resilient tourism.

To enhance disciplinary coverage and reduce database bias, two major bibliographic databases, Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus, were searched in parallel. WoS was selected for its rigorous indexing and cross-disciplinary reach, while Scopus expanded coverage in environmental and social sciences. Grey literature was excluded due to the absence of peer review and inconsistent methodological transparency. All data were retrieved on 23 May 2025 (WoS) and 2 December 2025 (Scopus).

A semi-systematic review was selected because the field of nature-based tourism, climate adaptation, and demographic aging is heterogeneous, spanning environmental science, public health, geography, tourism studies, and social policy. This heterogeneity makes a fully systematic, protocol-driven review less suitable, as it would exclude conceptual and policy-oriented works that are central to this inquiry [63]. This approach combines structured database searches with qualitative thematic synthesis, ensuring methodological rigor while allowing for conceptual inclusivity.

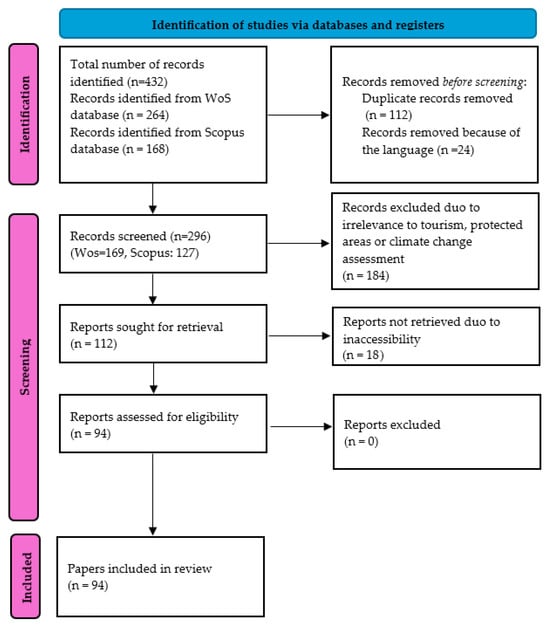

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) addressed vulnerability, resilience, or adaptation assessment within tourism or protected area contexts, and (2) explicitly considered socio-demographic dimensions, accessibility, or aging populations. The search strings applied were (“nature-based tourism” OR “ecotourism” OR “protected areas” OR “conserved areas”) AND (“climate change” OR “climate adaptation” OR “vulnerability” OR “resilience”) AND (“urban heat” OR “heat stress” OR “well-being”). Exclusion criteria removed studies focused solely on climate mitigation, those unrelated to tourism or protected areas, and those without relevance to health and aging. Duplicates were manually eliminated, and all bibliographic records were exported to Microsoft Excel for data organization and analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2) summarizes the selection process, indicating the number of records retrieved, screened, excluded, and retained. The eligibility of studies was assessed through a two-stage screening process. In the first stage, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers to determine relevance based on predefined inclusion criteria. In the second stage, full texts of potentially eligible studies were independently reviewed by the same reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. No automation tools were used in the screening or selection process. This review was not prospectively registered, as semi-systematic designs are exploratory by nature and emphasize conceptual synthesis rather than exhaustive inclusion.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Of the initial records retrieved, 264 papers originated from WoS and 168 from Scopus, with 112 overlapping publications. After deduplication, the combined dataset included 296 records subjected to title and abstract screening. Following exclusion based on relevance, 112 studies advanced to full-text review, of which 18 were removed due to inaccessibility. A total of 94 publications met all inclusion criteria and were retained for qualitative synthesis.

Qualitative content analysis was applied to identify conceptual trends, methodological approaches, and indicator frameworks. Each study was coded according to five predefined categories (Table 1): (1) Type of protected area (Urban Protected Area—UPA, Natural Protected Area—NPA, or mixed context); (2) Conceptual focus (vulnerability, resilience, or integrated assessment); (3) Methodological approach (indicator-based, participatory, modeling, or mixed-method); (4) Key variables and indicators (environmental, social, economic, and health-related dimensions); and (5) Consideration of population groups, with emphasis on aging and health outcomes.

Table 1.

Coding categories with definitions and examples.

Analytical coding combined inductive and deductive techniques to identify recurring patterns in how vulnerability and resilience were defined and operationalized. Axial coding was subsequently applied to consolidate codes into higher-order themes. The coding manual was iteratively refined, and inter-reliability was verified (Cohen’s K > 0.80) to ensure consistency. Data was managed in MaxQDA and Excel, with each study treated as an independent unit of analysis. Thematic saturation was achieved when no new conceptual categories emerged.

Horizontal comparison between UPAs and NPAs identified shared and divergent analytical orientations, while vertical analysis within each subset captured variations by methodological type and disciplinary focus.

The analysis tested four analytical hypotheses derived from prior literature:

- H1: In the NBT contexts, climate vulnerability is primarily conceptualized through environmental and socio-economic impacts, while resilience is framed through adaptive capacity and resource management strategies [64].

- H2: UPAs employ more integrated frameworks incorporating socio-economic and demographic indicators, whereas NPAs emphasize ecological and environmental metrics [65].

- H3: Existing vulnerability assessments insufficiently integrate the health and well-being dimensions for aging populations, particularly in UPAs, where socio-demographic factors are pronounced [66,67].

- H4: Current research lacks longitudinal and cross-regional analyses critical for understanding dynamic vulnerabilities and resilience trajectories over time [68].

To promote transparency and inclusiveness, only open-access publications were included to ensure accessibility and replicability of findings. While this may introduce minor selection bias, given regional disparities in open-access availability, the approach strengthens transparency. The certainty of evidence was appraised narratively due to heterogeneity in study design and outcomes. Methodological quality was evaluated using a simplified matrix adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) [69] (Table 2), assessing clarity of aims, methodological transparency, analytical rigor, relevance, and robustness of evidence. Each study was assessed across five dimensions with three scoring levels (High/Moderate/Low). The purpose was not to exclude lower-quality studies but to assess analytical validity and reproducibility.

Table 2.

Quality appraisal matrix.

The final comparative synthesis yielded a typology of assessment methods, consolidated indicator domains relevant to aging and health, and identified policy-relevant insights for strengthening context-specific adaptation pathways. By integrating systematic review principles with qualitative thematic synthesis, this study develops a comprehensive, demographic-sensitive framework for evaluating vulnerability and resilience in both urban and natural protected areas under accelerating climate change.

4. Results

The following section presents the results of the semi-systematic literature review, emphasizing thematic trends, methodological patterns, and comparative insights between UPAs and NPAs. The section also interprets how these methodological orientations influence reported vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies, highlighting conceptual advances and remaining research gaps. To facilitate comparative interpretation, Table 1 summarizes the reviewed studies across three protected area categories: Urban, Natural, and Mixed/Indigenous, highlighting their conceptual foci, methodological orientations, key indicators, and population considerations. This structure enables the identification of both thematic overlaps and context-specific divergences in how vulnerability and resilience are conceptualized across ecological, social, and demographic dimensions of NBT.

4.1. Descriptive Trends

The temporal and geographical distribution of the reviewed studies reveals a rapid growth in scholarly attention to climate vulnerability and resilience within NBT (Table 3). More than 75% of the analyzed papers were published between 2018 and 2025, underscoring the increasing policy relevance of climate adaptation in tourism and conservation. No publications met the inclusion criteria prior to 2010, confirming that this interdisciplinary field has only recently consolidated within sustainability and tourism research. A clear regional imbalance persists, with over 70% of studies originating from high-income countries, particularly the United States (28%), United Kingdom (18%), Australia (17%), and Canada (12%), while only isolated contributions stem from emerging economies such as China and Spain (≈10% each). This linguistic and regional bias indicates a Global North dominance, with limited representation from regions in the Global South that are often the most exposed to climate hazards [70,71,72]. Such concentration of evidence restricts the external validity of current frameworks and emphasizes the urgent need for comparative, context-sensitive research in underrepresented regions [73,74].

Table 3.

Analytical typology of vulnerability and resilience assessment approaches in NBT.

Descriptive mapping of methodological foci indicates that most studies emphasize ecological and environmental indicators (62%) over social (24%) or demographic (14%) dimensions. However, only about 8% of reviewed studies explicitly consider older adults as a focal socio-demographic group, indicating a substantial gap in the integration of aging, accessibility, and health considerations within NBT research [75,76]. When aging was mentioned, studies linked older adults’ participation in NBT to factors such as heat exposure, mobility constraints, and perceived well-being, emphasizing the need for inclusive, age-sensitive planning and management [79,80,94,95]. These findings call for systematic integration of demographic and health metrics within resilience frameworks, aligning ecological adaptation with social equity.

4.2. Comparative Thematic Analysis

4.2.1. Methodological Orientations

Across the 94 publications analyzed, 65 focused exclusively on Natural Protected Areas (NPAs), 18 on Urban Protected Areas (UPAs), and the remainder adopted mixed or cross-contextual perspectives. UPA-focused studies tended to apply environmental and urban-planning methodologies, while NPA research employed broader ecosystem-based and community-oriented frameworks.

UPAs predominantly employed indicator-based macroecological analyses, reported in approximately 80% of these studies (Table 4), often incorporating soil and vegetation assessments [76], remote sensing, GIS mapping [84], participatory surveys [82], and thermal comfort indices to evaluate urban heat islands and social vulnerability [81]. Health and aging were moderately addressed, appearing in 32% of studies, with indirect benefits to human well-being assessed through urban ecosystem services [83].

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of UPAs and NPAs.

In contrast, NPAs were typically investigated using mixed-method approaches, representing 66% of papers (Table 4), which combined biophysical monitoring (50%) [93,99] with qualitative interviews (36%) [91], focus groups (20%) [102], DPSIR frameworks (10%) [97], ecosystem service modeling (15%) [114], and hierarchical regression analyses (8%). Environmental indicators, reported in 62% of NPA studies, included biodiversity, ecosystem services, natural capital, and climate change impacts, while social and economic dimensions [86,89,97], addressed in 38% of studies, captured local governance, community engagement, livelihoods, and ecotourism [99,102]. Health outcomes, such as subjective well-being, resilience, and nutrition, were occasionally considered (15%), whereas aging populations were rarely targeted (4%).

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which constitute approximately 40% of the NPA studies analyzed, employed a diverse set of methods, including case studies, participatory approaches, remote sensing, modeling, and bibliometric analyses [113,119]. While these studies frequently evaluated ecosystem degradation and livelihood impacts, few explicitly linked climate adaptation to demographic or public health outcomes.

Mixed and Indigenous Protected Areas used qualitative, participatory, and system-based approaches (e.g., photovoice, policy analysis, adaptive management) [97,123,127]. These studies demonstrated higher integration of social and cultural resilience indicators but continued to neglect aging populations as a discrete demographic dimension.

4.2.2. Vulnerability and Adaptation

Comparative synthesis reveals notable differences in the manifestation of vulnerability and adaptation approaches across protected area types. In UPAs, dominant stressors included urban heat (70%) [84], air pollution (32%) [81], and habitat fragmentation (26%). Adaptation strategies (70%) were largely engineered and governance-based, emphasizing green infrastructure, urban greening, and adaptive zoning [83]. Although urban proximity facilitates integration of well-being metrics, aging-specific measures appear sporadically and often lack empirical grounding.

NPAs, by contrast, faced stressors associated with climate-induced habitat loss (55%), biodiversity shifts (21%), and invasive species (32%). Adaptation was primarily ecosystem-based and community-driven (41%), often incorporating connectivity conservation measures and Indigenous knowledge systems. Despite these inclusive approaches, few studies systematically addressed aging or health outcomes, reflecting a persistent disciplinary gap between ecological adaptation and demographic resilience [101,105].

In MPAs, vulnerability was influenced by climate and anthropogenic stress, species redistribution, coral survival, and freshwater pressures [114,131]. Adaptation relied on ecosystem management, nature-based solutions, and policy interventions, with human well-being assessed through food security, mental well-being, and equitable access to resources [111], although aging populations were not specifically considered.

In Mixed and Indigenous protected areas, in almost all studies integrated, community-centered resilience approaches addressed ecological, social, and economic dimensions simultaneously [122]. Transformative governance, ecosystem-based adaptation, and regenerative tourism were central frameworks [126]. These studies exhibited the most holistic understanding of resilience, yet demographic inclusivity, particularly aging, remains an emerging theme requiring deeper theoretical and empirical integration.

4.2.3. Socio-Demographic Considerations

Socio-demographic considerations revealed that only approximately 8% of reviewed studies explicitly included older adults as a focal population, highlighting a substantial gap in the integration of aging, accessibility, and health within nature-based tourism research [75,76,77,78,79,80]. Where included, studies emphasized age-sensitive planning [86], considering factors such as heat exposure (all studies) and perceived well-being [80]. Across all protected area types, inclusive approaches integrating ecological adaptation with social equity remain limited, though they are most advanced in Mixed and Indigenous contexts [125].

The reviewed literature indicates that older adults are particularly vulnerable to climate-related health risks, including heat- and cold-related illnesses, cardiovascular stress, dehydration, and mental health impacts [88,131]. In urban contexts, urban heat islands, air pollution, and social isolation exacerbate these risks, with UPAs reported to mitigate impacts through urban greening, shaded areas, and accessible infrastructure [89]. In NPAs, natural landscapes provide stress reduction, cognitive benefits, and opportunities for physical activity suitable for older adults, while cooler microclimates, clean air, and social engagement further reduce vulnerability [132]. Few studies propose actionable frameworks for integrating gerontological insights into NBT resilience planning.

4.2.4. Synthesis Across Ecological, Social, Economic, and Health Dimensions

Thematic synthesis identifies distinct but interlinked resilience pathways across four analytical dimensions, including ecological, social, economic, and health. Ecologically, biodiversity, ecosystem services, habitat connectivity, coral bleaching, and climate impacts were consistently evaluated, though the emphasis varied according to context [109,114,123], with UPAs focusing on urban biodiversity and heat mitigation [82,84], and Mixed/Indigenous areas integrating land, marine, and social–ecological systems [125].

Socially, community engagement, governance, equity, and well-being were increasingly considered, with UPAs addressing urban planning and social vulnerability [85], NPAs examining local livelihoods and participatory governance [89], and Mixed/Indigenous studies emphasizing transformative governance and cultural resilience. Economically, tourism, livelihoods, provisioning, and adaptation benefits were commonly addressed, with UPAs linking economic outcomes to urban planning, NPAs measuring income and ecotourism [99], MPAs analyzing fisheries [121] and the water–energy–food nexus [110] and Mixed/Indigenous areas evaluating tourism, ecosystem-based adaptation, and social benefit–cost outcomes [124]. Health dimensions were most systematically integrated in UPAs and Mixed/Indigenous areas, including indicators of subjective well-being, mental and physical health, resilience, nutrition, and accessibility, though older adult populations were rarely explicitly targeted [83,125]. Overall, the evidence base underscores the need for integrated frameworks that connect ecological resilience with social equity and demographic inclusivity to inform adaptive management of NBT under climate change.

5. Discussion

5.1. Mapping Climate Vulnerability and Resilience Across UPAs and NPAs

This review demonstrates that vulnerability and resilience assessments in nature-based tourism (NBT) have expanded rapidly over the past decade, consistent with the broader rise of climate-risk scholarship in conservation and tourism studies [133]. More than 75% of the analyzed studies were published between 2018 and 2025, highlighting the growing significance of climate adaptation within tourism and conservation. However, the synthesis also reveals substantial conceptual fragmentation and limited demographic inclusivity, particularly regarding aging and health-related dimensions.

Empirical evidence linking ecosystems, human well-being, and adaptive management remains geographically skewed toward Europe and North America, while studies from Africa, Central and South America, and parts of Asia are scarce. This concentration underscores a persistent epistemic bias that constrains the generalizability of climate resilience frameworks, necessitating greater emphasis on Global South perspectives and cross-regional case studies [134,135]. These findings support H1, confirming that vulnerability in NBT is primarily conceptualized through environmental and socio-economic mechanisms, whereas resilience is framed through adaptive management and resource-based strategies.

The analysis shows that UPAs and NPAs are shaped by distinct methodological paradigms. UPAs rely heavily on indicator-based, GIS-driven and thermal comfort assessments, mirroring the urban climate adaptation literature where heat islands, air pollution, and accessibility dominate analytical priorities [136,137]. This technocratic orientation treats resilience as a management outcome rather than as a socially embedded capacity, reflecting an overreliance on engineered and governance-based metrics. Conversely, NPA studies robustly monitor environmental indicators but rarely integrate social or health metrics, thus underrepresenting human-centered resilience [1,53,83]

Recent empirical studies further enrich this comparative picture. In the case of Potatso National Park in China [97], it was demonstrated that hybrid ecological compensation (EC) mechanisms, combining cash payments, employment support, and education incentives, significantly enhanced the livelihood resilience of ethnic minority communities, with increases of up to 0.074 in livelihood score and 37.65% in social benefit at modest cost. These findings highlight the importance of diversified, cost-effective EC policies for reconciling biodiversity conservation with socio-economic well-being, particularly in minority-dominated or economically fragile regions. Such hybrid models represent an emerging adaptation pathway that bridges ecological and social resilience, providing a practical mechanism for equitable climate adaptation in NPAs. Moreover, the marked Global North bias and limited cross-regional or longitudinal designs substantiate H4, revealing that existing studies rarely explore the temporal evolution of vulnerabilities or resilience trajectories across contexts. This pattern highlights an emerging but fragmented evidence base that remains largely descriptive and geographically uneven.

A synthesis of methodologies (Table 3) underscores the necessity of adopting integrated, hybrid assessment frameworks that combine ecological indicators, human-centered metrics, and climate projections. For instance, approaches integrating remote sensing of environmental variables with participatory social assessments have been shown to improve the precision of ecosystem monitoring while capturing community-specific vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities [75,88,89]. Such frameworks thus emerge as essential tools for evidence-based planning, enabling inclusive management and the co-design of adaptive strategies that enhance both ecosystem resilience and human resilience [49,77,78]. In relation to UPAs, NPAs predominantly adopt mixed-methods and ecological monitoring approaches, aligning with social–ecological systems thinking [30] and the ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) paradigm [138]. Marine studies further reflect global concerns around ocean warming, coral bleaching, and blue-carbon loss [130]. However, attention to the social dimensions of climate impacts on local coastal populations remains limited, with notable exceptions including social–ecological well-being frameworks [139], practitioner-focused adaptation studies [140], and localized assessments of MPAs as community-level adaptation measures [141]. Mixed and Indigenous protected areas show the highest integration of social, cultural, ecological, and governance dimensions, consistent with literature highlighting Indigenous knowledge systems as central to climate resilience and landscape stewardship [142,143]. These studies reflect a shift toward participatory and transformative governance frameworks, though operationalization remains context-specific and rarely applied in urban or strictly natural areas. However, the methodological diversity within NPAs supports an integrated understanding of biophysical and social vulnerability but remains uneven in its treatment of social equity and health outcomes. Incorporating multi-scalar and cross-disciplinary data thus strengthens the capacity of managers and policymakers to implement interventions that are both ecologically effective and socially equitable, addressing conservation, livelihoods, and well-being simultaneously [96].

The comparative synthesis presented in Table 4 highlights key differences in how climate vulnerability emerges in UPAs compared to NPAs, carrying important implications for the resilience of nature-based tourism and for adaptive governance. In UPAs, compounded stressors such as heat island effects, air pollution, and habitat fragmentation [82] create unique challenges for maintaining ecosystem services critical for tourism and recreation. For instance, Šalkovič et al. [84] demonstrated that urban heat islands in Bratislava’s green corridors significantly decreased recreational usability and thermal comfort, particularly during summer peaks. Urban Protected Areas studies more frequently incorporate human health and well-being variables because of their direct links to public health, accessibility, and socio-demographic diversity, including older adults [75,89]. Common methodological tools in UPAs include GIS spatial mapping, heat stress indices, surveys, and participatory assessments that evaluate accessibility, thermal comfort, and social engagement. In contrast, NPAs face vulnerabilities that stem from climate-driven ecosystem degradation. Examples include coral bleaching [106] and forest ecosystem decline due to deforestation and drought stress [88], demonstrating how climate change alters biodiversity-dependent attractions and tourism economies.

5.2. Resilience Pathways in UPAs and NPAs

Findings reveal that vulnerability drivers are strongly dependent on context. UPAs face heat exposure, pollution, and fragmentation that are widely recognized as stressors in urban ecology [143], while NPAs are shaped by climate-induced habitat shifts, species redistribution, and anthropogenic pressures, consistent with global reports on biodiversity loss and climate impacts [144,145].

The contrast between UPAs and NPAs thus reflects two complementary resilience logics. UPAs tend to rely on engineered and governance-based measures, such as urban greening, cooling infrastructure, and multi-level climate governance [95]. NPAs, conversely, rely more on ecosystem-based and culturally rooted strategies, including connectivity conservation, Indigenous-led management, and hybrid ecological compensation [97,123]. Integrating these approaches could yield hybrid adaptation models that strengthen both ecological and social resilience, combining urban innovation with traditional ecological knowledge and livelihood-based compensation mechanisms.

Marine and coastal NPAs present further complexity. The 2014–2017 global coral bleaching event [106] revealed that even well-managed marine protected areas could not fully buffer against global-scale stressors such as marine heatwaves, which caused widespread coral mortality and long-term degradation of reef structure and tourism potential. However, Claar et al. [116] found evidence of adaptive coral symbioses, in which some corals survived prolonged heatwaves through shifts to heat-tolerant symbionts, suggesting that biological adaptation can complement human-led resilience efforts. Similarly, Lloret et al. [89] highlighted that offshore wind energy projects in the Mediterranean, if poorly planned, could undermine marine biodiversity and protected area integrity, emphasizing the need to balance climate mitigation goals with biodiversity protection through spatial planning and precautionary principles.

The integration of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) is emerging as a unifying framework across both UPAs and NPAs. Chee et al. [115], through a Malaysian case study, underscored that regionally trialed NbS approaches, such as mangrove restoration, coral rehabilitation, and seagrass protection, can provide scalable blueprints for sustainable tourism and climate adaptation but require policy integration, knowledge sharing, and sustainable finance instruments to achieve full uptake. The comparative synthesis also resonates with broader research priorities identified by Friedman et al. [108], who argue that achieving healthy marine ecosystems and human communities under climate change demands cross-sectoral, anticipatory, and justice-oriented approaches. These approaches bridge ecological science with social equity, health, and governance dimensions, directly aligning with the human-centered adaptation challenges faced in both UPAs and NPAs.

Resilience strategies diverge across contexts but share complementary potential. UPAs emphasize technological and institutional solutions, including green infrastructure, heat-mitigation design, and multi-level governance [95], whereas NPAs show greater reliance on ecological restoration, connectivity conservation, and the application of Indigenous and local knowledge systems [123]. This complementarity suggests opportunities for integrated adaptation strategies that couple urban governance innovations with ecosystem-based approaches. A persistent gap across both contexts is the limited integration of human health within climate adaptation and resilience planning. Although Knudson and Rose [85] documented health benefits of NBT, systematic health impact assessments remain rare, particularly for vulnerable or aging visitors exposed to climate extremes. Bridging these paradigms calls for trans-scalar adaptation frameworks that link urban innovation, community participation, and ecosystem-based conservation.

The emerging paradigm of regenerative tourism [130] provides a promising integrative pathway, fostering positive feedback loops between visitor well-being, local livelihoods, and ecosystem restoration across both urban and natural settings. However, this finding indicates a missed opportunity to align tourism and conservation management with public health adaptation agendas. Although the growing field of regenerative tourism [130] could offer a unifying framework for advancing such integrated approaches, attention should also be paid to the limitations and several challenges of regenerative tourism. This concept can often be misinterpreted or superficially applied [146], leading to “greenwashing”, where businesses claim to be regenerative without implementing substantive changes [147]. Furthermore, there could be tensions between tourism development and local community needs, which may require careful management and dialogue to ensure that benefits are equitably shared.

5.3. Elderly Well-Being at the Climate–Nature Nexus: Risks, Ecosystem Services, and Adaptive Strategies

One of the most striking findings is the systematic underrepresentation of older adults in NBT vulnerability research. Despite strong evidence that older individuals face disproportionate climate-related health risks, including heat stress, cardiovascular strain, reduced mobility, and social isolation [148], only about 10% of reviewed studies considered aging explicitly. This gap mirrors broader inequalities in climate adaptation research where older adults, disabled populations, and other groups with heightened vulnerability remain understudied [149].

In particular, intensifying climate risks pose a growing threat to human health. Its cascading effects range from food and water insecurity and deteriorating air quality to the spread of vector-borne diseases and exacerbations of chronic conditions, underscoring the interconnectedness of environmental and social vulnerability. Older adults are disproportionately affected due to physiological sensitivity to heat and cold stress and limited mobility [131]. They are more susceptible to heat-related illnesses and conditions, such as cardiovascular stress and dehydration, and may face limitations in mobility as well as negative mental consequences like anxiety and trauma [12].

Urban areas, where heat islands and air pollution interact with social isolation and income disparities, magnify these risks. In this context, ecosystem-based adaptation measures, such as urban greening and heat mitigation strategies, can play a critical role in reducing health burdens and mortality among older populations [150]. Beyond urban contexts, protected areas in rural regions offer important health and well-being benefits for elderly visitors. Access to natural landscapes can reduce stress, improve cognitive function, and support physical activity at intensities suitable for older adults [151,152]. Cooler microclimates, cleaner air, and opportunities for social engagement within rural protected areas can further mitigate climate-related health risks [132]. As a result, these landscapes serve not only as conservation zones but also as vital spaces for enhancing overall quality of life of aging populations.

In this research, UPAs were identified as areas that more often incorporate health and accessibility metrics than NPAs, as well as comprehensive age-sensitive planning, but this remains rare. NPAs are even less likely to address aging issues despite the known benefits of natural environments for mental and physical health, stress reduction, and cognitive functioning [153]. This discrepancy illustrates the mismatch between public health evidence and research priorities for nature benefits. Age-friendly design solutions, such as shaded paths, accessible trails, emergency preparedness, and mobility-friendly infrastructure, have been recognized as effective in the health and recreation literature [154], yet are inconsistently integrated across different types of protected areas.

Integrating vulnerability and risk analysis of ecosystem services, vulnerable older people and NBTs relies on multidisciplinary expertise and multi-criteria analysis of spatial, ecological and socio-economic data for specific UAPs or NPAs. Applying this approach could reveal a wider range of negative impacts on health and well-being and suggest solutions to overcome risks for all visitors, especially older people who may have reduced mobility, slower physiological responses and greater susceptibility to heat stress or health complications during extreme events. The failure to address this issue certainly affects the design of adaptive strategies in UPAs and NPAs aimed at the health and well-being of older visitors.

5.4. Synthesis and Implications

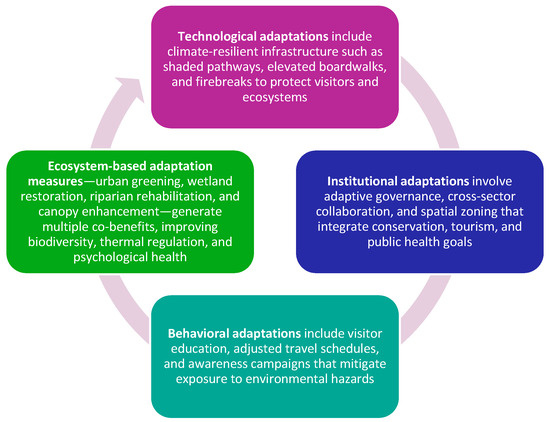

Overall, the literature reveals a growing movement toward integrated frameworks that connect ecological resilience with social and health-oriented adaptation. Such frameworks are crucial for guiding climate adaptation in tourism, ensuring that vulnerable populations, including older adults, can safely engage in nature-based recreation [49,79]. Effective adaptation in NBT requires multi-dimensional responses (Figure 3) encompassing technological, institutional, behavioral, and ecosystem-based measures [61,155].

Figure 3.

Multi-dimensional responses for effective adaptation in NBT [18,24,26,75,77,156,157].

For aging populations, such measures are particularly valuable as they enhance thermal comfort, support safe physical activity, and promote psychological health. Adaptive governance and participatory planning, supported by robust climate-health datasets, are essential to operationalize these strategies and bridge vulnerability assessments with actionable resilience planning [36,80]. Taken together, these findings underscore the need for integrated, evidence-based frameworks that unite ecological, social, and demographic dimensions in managing NBT under climate change. Building climate-resilient tourism system demands that both ecosystem integrity and human well-being, especially among older and vulnerable populations, be treated as interdependent objectives [81,89].

The comparative findings confirm H2, showing a consistent methodological and conceptual divide between UPAs and NPAs. UPA research demonstrates higher integration of socio-economic and demographic data, often linking ecosystem services with urban livability and accessibility metrics, while NPA studies remain ecologically centered, emphasizing biodiversity, habitat integrity, and ecosystem functionality. This division supports the hypothesis that analytical focus differs systematically across contexts. Moreover, the limited engagement with health, aging, and well-being across both types of protected areas validates H3, underscoring a significant research gap in addressing the adaptive needs of older or vulnerable populations. Even when human health variables appear in UPA studies, they are treated as secondary indicators rather than integral components of resilience assessment.

5.5. Integrating Ecosystem Integrity and Human Well-Being in Climate-Resilient Tourism

Results reveal how governance structures shape resilience across contexts. This finding is consistent with previous studies of complex socio-ecological systems [17], which emphasize the importance of bringing together different areas of knowledge within a common analytical framework to improve understanding of why natural resources and ecosystem services deteriorate.

While the Social–Ecological Systems (SES) framework provides a powerful lens for examining interactions between governance, resource systems, and human users, its application to climate-resilient tourism in protected areas reveals several important limitations. First, SES models traditionally assume relatively coherent governance units, yet the findings from UPAs and NPAs demonstrate that governance boundaries rarely align with ecological boundaries in practice. Urban Protected Areas are embedded within highly fragmented municipal jurisdictions that prioritize zoning, infrastructure, and public health, while NPAs often operate under polycentric arrangements involving Indigenous groups, conservation authorities, and tourism actors. This institutional and spatial mismatch challenges the SES framework’s ability to capture multi-level governance complexities, echoing critiques that SES models oversimplify real-world institutional dynamics [158,159]. This suggests that SES models should account for spatial and institutional heterogeneity when assessing climate resilience in protected areas.

Additionally, the differential vulnerability pathways observed in UPAs (heat stress, pollution) versus NPAs (habitat shifts, species loss) challenge traditional tourism vulnerability assessments that treat protected areas as homogeneous systems [94]. Our findings align with Folke’s [30] resilience theory, which emphasizes context-specific adaptation strategies but extends it by showing that UPAs benefit from engineered resilience while NPAs depend on ecological resilience. This implies that tourism resilience models should incorporate place-based adaptation typologies rather than universal solutions.

The neglect of human health dimensions in climate adaptation planning for NBT highlights a critical gap in protected area management theory. While biocentric conservation models (e.g., the Nature Needs Half movement) prioritize biodiversity, our findings suggest that anthropocentric considerations, particularly health equity for aging populations [85], must be embedded in resilience frameworks. This supports Pascual et al.’s [126] call for a “biodiversity–climate–society nexus” in conservation science, where human well-being is explicitly linked to ecosystem health.

Furthermore, analysis provides empirical support for regenerative tourism model [130], which moves beyond sustainability toward net-positive outcomes for ecosystems and communities. The success of Indigenous-led conservation in NPAs [123] and community-based resilience in UPAs [100] suggests that regenerative tourism frameworks must incorporate Traditional Ecological Knowledge as a resilience strategy, Health-adaptive tourism infrastructure [89] and Equitable financing mechanisms [101]. This expands the theoretical foundations of sustainable tourism by emphasizing active restoration over passive conservation. Future research should test these propositions through longitudinal case studies and comparative meta-analyses across different biogeographical and socio-political contexts. Such work would further refine theoretical models of climate-resilient tourism in protected areas, ensuring they remain robust in an era of rapid global change.

5.6. Practical Implications

The study findings highlight three strategic priorities for advancing climate-resilient, socially inclusive tourism. First is the development of comprehensive, integrative assessment frameworks. Within the broader debate on the shortcomings of standardization frameworks for assessing vulnerability and adaptation to climate change, it is highlighted that fragmented metrics create a methodological barrier that hinders comprehensive vulnerability and adaptation synthesis [160,161]. Our results support calls for multi-dimensional, socially inclusive approaches that combine ecological monitoring with community engagement, health equity, and demographic sensitivity, aligning with new paradigms of “equitable resilience” and “equitable natural services” [162,163]. Therefore, future research and management should prioritize frameworks that combine ecological, climatic, and socio-demographic indicators, enabling robust and comparable assessments of vulnerability and resilience across heterogeneous socio-ecological systems [94]. This integration is key to bridging the gap between scientific assessment and actionable policy.

Secondly, embedding health-adaptive design in tourism infrastructure. Tourism planning should incorporate design principles that reduce exposure to climate-related health risks, such as shade provision, microclimate regulation, universal accessibility, and emergency response systems. Integrating health and well-being into urban and natural tourism infrastructure can enhance overall destination resilience and improve safety for both residents and visitors, particularly older adults, and climate-vulnerable groups [89].

Finally, innovative financing for climate-resilient tourism. Emerging financial instruments, such as green bonds, biodiversity credits, and performance-based conservation funds, offer new opportunities to link economic sustainability with ecological restoration. Aligning tourism revenue streams with conservation performance (e.g., REDD+-linked mechanisms) can enhance the long-term financial viability of protected area management [101] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Intervention pathways for UPAs and NPAs.

Together, these pathways establish a foundation for transformative adaptation that bridges ecosystem integrity, social equity, and demographic inclusion. This approach operates multiple SDGs [21,22,55] and advances the Paris Agreement’s commitment to resilient, just transitions [164,165,166]. By integrating governance innovation, climate-responsive infrastructure, and sustainable finance, this review repositions NBT as a vital policy arena for fostering regenerative, climate-resilient, and inclusive futures.

6. Conclusions

This study provides an integrative synthesis of how Urban Protected Areas and Natural Protected Areas conceptualize and address climate vulnerability and resilience within Nature-Based Tourism contexts. Employing a semi-systematic literature review guided by PRISMA procedures [56], the analysis of 72 peer-reviewed studies (2010–2025) revealed pronounced conceptual, methodological, and thematic asymmetries, alongside critical research gaps in integrating health, well-being, and aging considerations within resilience frameworks.

In NBT contexts, climate vulnerability is largely framed through environmental and socio-economic pressures, while resilience emphasizes adaptive capacity and resource management (H1). NPAs focus on ecosystem degradation, species loss, and ecological connectivity, whereas UPAs highlight anthropogenic stressors such as urban heat, air pollution, and governance complexity. Synthesizing these strands confirms that resilience in NBT operates as a dynamic, multi-scalar social–ecological process, shaped by interactions between governance structures, ecosystem functions, and human adaptive behaviors. Although 69% of studies focused on NPAs and only 19% on UPAs, this imbalance reveals how prevailing research priorities shape the field rather than representing inherent differences in vulnerability or resilience potential.

As H2 suggests, methodological orientations differ substantially. NPAs employ indicator-based and biophysical models (e.g., DPSIR, ecosystem service frameworks), while UPAs more often apply integrated and participatory approaches, including GIS mapping, heat-stress indices, and stakeholder surveys. Interpreting these approaches as complementary rather than dichotomous underscores the value of hybrid analytical frameworks that merge ecological precision with participatory and health-sensitive perspectives. The synthesis revealed that UPA studies demonstrate greater inclusion of accessibility, equity, and health-related indicators, while NPA studies remain anchored in biophysical and ecosystem-based paradigms.

Furthermore, H3 is validated by the persistent underrepresentation of health and demographic dimensions. Only about 8% of studies explicitly address aging populations or health-related indicators, indicating a structural gap in NBT scholarship and limiting our understanding of how climate change shapes comfort, safety, and participation for older adults and other climate-sensitive groups. H4 is also supported: longitudinal and cross-regional comparative research remains scarce, with most studies regionally clustered in the Global North and limited in temporal scope, reducing the generalizability of findings across socio-ecological contexts.

These findings illustrate that UPAs tend toward engineered and governance-based resilience, while NPAs rely on ecological and community-based strategies. Viewed together, these orientations converge toward a hybrid resilience model aligned with regenerative tourism principles, without implying direct causal relationships among governance, ecological adaptation, and visitor well-being. They also empirically support Duarte et al.’s regenerative tourism paradigm [130], showing that adaptive management rooted in Traditional Ecological Knowledge [123], equitable financing [101], and health-adaptive tourism design [89] can yield net-positive socio-ecological outcomes. Integrating health-adaptive infrastructure [89], traditional ecological knowledge [123], and regenerative tourism principles [130] provides a pathway toward inclusive, net-positive adaptation.

Although PRISMA ensures methodological transparency, several limitations must be acknowledged. The reliance on English-language and peer-reviewed sources introduces regional and epistemic bias, excluding context-specific grey literature and Indigenous knowledge systems critical for place-based adaptation. Furthermore, the rapid growth of post-2015 literature limits historical trend analysis, indicating that the patterns synthesized here reflect dominant academic framings rather than the full diversity of on-the-ground adaptive practices. Addressing these issues requires complementing systematic procedures with narrative synthesis, multilingual searches, and stakeholder consultation to ensure representativeness across diverse social–ecological settings.

Based on previously stated research gaps, three key directions emerged. First, longitudinal comparisons of adaptation trajectories across UPAs and NPAs are needed to identify evolving vulnerabilities and resilience pathways. Second, quantitative assessment of elderly visitors’ exposure and adaptive responses to climate extremes, integrating thermal comfort, accessibility, and well-being indicators, would enhance the empirical basis for inclusive adaptation planning. Third, the development of standardized, multi-scalar resilience metrics linking ecological, social, and governance dimensions is essential for benchmarking and informing policy design.

Finally, UPAs and NPAs require distinct yet complementary adaptation strategies. UPAs benefit from urban green infrastructure, adaptive zoning, and participatory governance, while NPAs depend on ecosystem restoration, connectivity conservation, and co-management with Indigenous communities. Together, these approaches represent dual pathways toward unified policy vision where ecological integrity, human health, and social equity function as interdependent pillars of climate-resilient tourism.

Author Contributions

Methodology, I.M.V.; investigation and validation, I.M.V., M.Z., A.M. and D.Z.; resources, M.Z.; writing—original draft, M.Z., A.M. and I.M.V.; writing—review and editing, D.Z. and A.M.; project administration, I.M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Croatian Science Foundation, within the scope of the project PACT-VIRA (Project code: IP-2024-05-9190). The APC was funded by the same source.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that research was conducted within the scope of the project PACT-VIRA (Project code: IP-2024-05-9190), funded by the Croatian Science Foundation. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Croatian Science Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Buckley, R. Evaluating the net effects of ecotourism on the environment: A framework, first assessment and future research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 643–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmford, A.; Green, J.M.H.; Anderson, M.; Beresford, J.; Huang, C.; Naidoo, R.; Walpole, M.; Manica, A. Walk on the wild side: Estimating the global magnitude of visits to protected areas. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; Silva, L.F.; Vieira, A. Protected areas and nature-based tourism: A 30-year bibliometric review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Beraldo Souza, T.; Spenceley, A.; Bricker, K.; Eagles, P.F.J.; Epler Wood, M.; Green, R.; Haggar, K.; Hvenegaard, G.; Lemieux, C.J.; et al. Strengthening sustainable tourism’s role in biodiversity conservation and community resilience. In IUCN WCPA Issues Paper Series No. 07; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA): Gland, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; McCool, S.F.; Haynes, C.D. Sustainable Tourism. In Protected Areas: Guidelines for Planning and Management, 1st ed.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2002; pp. 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Laurance, W.F.; Franklin, J.F. Global decline in large old trees. Science 2012, 338, 1305–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP-WCMC; IUCN; NGS. Protected Planet Report, 1st ed.; UNEP-WCMC, IUCN and NGS: Cambridge, UK; Gland, Switzerland; Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://protectedplanetreport2020.protectedplanet.net/pdf/Protected_Planet_Report_2018.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- McCool, S.F.; Mandic, A. A Social-Ecological Systems Perspective on Working toward Resilience in Nature-Based Tourism Planning. Tour. Plann. Dev. 2025, 22, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Spenceley, A.; Leung, Y.F. Toward Resilient Nature-Based Tourism in the Post-Pandemic Era: Integrating Governance, Visitor Dynamics, Finance, and Ecosystem Integrity. Tour. Plann. Dev. 2025, 22, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.C.; Maheswaran, R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: A review of the evidence. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrang-Ford, L.; Siders, A.R.; Lesnikowski, A.; Fischer, A.P.; Callaghan, M.W.; Haddaway, N.R.; Mach, K.J.; Araos, M.; Shah, M.A.R.; Wannewitz, M.; et al. A systematic global stocktake of evidence on human adaptation to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przewoźna, P.; Inglot, A.; Mielewczyk, M.; Mączka, K.; Matczak, P. Accessibility to urban green spaces: A critical review of WHO recommendations in the light of tree-covered areas assessment. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Kenter, J.; Bonn, A.; Broad, K.; Burt, T.P.; Fazey, I.R.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Hubacek, K.; Nainggolan, D.; Quinn, C.H.; et al. Participatory scenario development for environmental management: A methodological framework. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schoon, M.L. Principles for Building Resilience. In Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social-Ecological Systems, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Martín-Lucas, M.; Dias, A.; Castellano-Álvarez, F.J. What role geoparks play improving the health and well-being of senior tourists? Heliyon 2023, 9, e22295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human-environment interactions in urban green spaces—A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Rall, E.; Kabisch, N.; Kaczorowska, A.; Kain, J.H.; Artmann, M.; Pauleit, S. The uptake of the ecosystem services concept in planning discourses of European and American cities. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković Vukadin, I.; Dolenc, N.; Opačić, V.T. Diversity, Features, and Challenges of Managing Urban Protected Areas, the Case of Croatia. Tour. Plann. Dev. 2025, 22, 677–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 1st ed.; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- Braat, L.C.; de Groot, R. The ecosystem services agenda: Bridging the worlds of natural science and economics, conservation and development, and public and private policy. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.; Scott, D.; McBoyle, G. Analogue analysis of climate change vulnerability in the US Northeast Ski Tourism. Clim. Res. 2009, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Lemieux, C. The vulnerability of tourism to climate change. In Routledge Handbook of Tourism and the Environment, 1st ed.; Holden, A., Fennell, D.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Becken, S. A climate change vulnerability assessment methodology for coastal tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Hay, J. Climate Change and Tourism: From Policy to Practice, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Challenges of tourism in a low-carbon economy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2012, 3, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Spenceley, A.; Fennell, D.A. Handbook on Managing Nature-Based Tourism Destinations Amid Climate Change (Research Handbooks in Tourism), 1st ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 1–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience (Republished). Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 44. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269991 (accessed on 2 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.; Xepapadeas, T.; Crépin, A.S.; Norberg, J.; de Zeeuw, A.; Folke, C.; Hughes, T.; Arrow, K.; Barrett, S.; Daily, G.; et al. Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: Modeling and policy implications. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2013, 18, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Social Report 2023: Leaving No One Behind in an Ageing World, 1st ed.; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, N.; Wagstaffe, A.; Briscoe, S.; Garside, R. How do older people describe their sensory experiences of the natural world? A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, N.; Lak, A.; Moussavi, A.S.M.R. Green space and the health of the older adult during pandemics: A narrative review on the experience of COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1218091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinger, P.; Dreher, B.L.; Soh, S.E.; Dow, B.; Batchelor, F.; Hill, K.D. Results from the ENJOY MAP for HEALTH: A quasi experiment evaluating the impact of age-friendly outdoor exercise equipment to increase older people’s park visitations and physical activity. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, W.; Cheng, B.; Feng, X.; Zhuang, X. Relationship between urban green space and mental health in older adults: Mediating role of relative deprivation, physical activity, and social trust. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1442560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, E.H.; Min, J.Y.; Choi, B.Y.; Ryoo, S.W.; Min, K.B.; Roberts, J. Spatiotemporal variability of the association between greenspace exposure and depression in older adults in South Korea. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.D.; Zanotta, D.C.; Ray, N.; Veronez, M.R. Earth observation data uncover green spaces’ role in mental health. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Annex II: Glossary. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, 1st ed; Möller, V., van Diemen, R., Matthews, J.B.R., Méndez, C., Semenov, S., Fuglestvedt, J.S., Reisinger, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 2897–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonia, A.; Jezierska-Thöle, A. Sustainable tourism in cities—Nature reserves as a ‘new’ city space for nature-based tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero-Bermejo, I.; Crespo-Luengo, G.; Hernández-Lambraño, R.E.; de la Cruz Rodríguez, D.; Sánchez-Agudo, J.Á. Natural Protected Areas as Providers of Ecological Connectivity in the Landscape: The Case of the Iberian Lynx. Sustainability 2021, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zovko, M.; Marković Vukadin, I.; Zovko, D. Understanding the IPCC Climate Risk-Centered Framework and Its Applications to Assessing Tourism Resilience. Geographies 2025, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ali, Q.; Khan, M.T.I. The role of digitalization, infrastructure, and economic stability in tourism growth: A pathway towards smart tourism destinations. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2025; Volume 49, pp. 1308–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Seow, A.N.; Choong, Y.O.; Low, M.P.; Ismail, N.H.; Choong, C.K. Building tourism SMEs’ business resilience through adaptive capability, supply chain collaboration and strategic human resource. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2024, 32, e12564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Manohar, S.; Mittal, A. Reconfiguration and transformation for resilience: Building service organizations towards sustainability. J. Serv. Mark. 2024, 38, 404–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garschagen, M.; Romero-Lankao, P. Exploring the relationships between urbanization trends and climate change vulnerability. Clim. Change 2015, 133, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Towards “Just Resilience”: Leaving No One Behind When Adapting to Climate Change. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/towards-just-resilience-leaving-no-one-behind-when-adapting-to-climate-change (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Bennett, E.M.; Cramer, W.; Begossi, A.; Cundill, G.; Díaz, S.; Egoh, B.; Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Krug, C.; Lavorel, S.; Lazos, E.; et al. Linking biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human well-being: Three challenges for designing research for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Dietz, T.; Kramer, D.B.; Ouyang, Z.; Liu, J. An integrated approach to understanding the linkages between ecosystem services and human well-being. Ecosyst. Health. Sustain. 2015, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, Q.; He, C.; Chen, P.; Yin, D.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, Y. A bibliographic review of the relationship between ecosystem services and human well-being. Environ. Develop. Sustain. 2024, 25965–25992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]