Abstract

City walk is an emerging form of short-term urban activity in which participants explore city streets and alleys to perceive distinctive cultural symbols, social connections, and spatial organizations of a place. This practice provides a new pathway for understanding urban placeness. Drawing on both humanistic and structuralist geographical theories of placeness, this study applies the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic model to identify latent themes in online textual data and constructs an evaluation framework for placeness together with a set of indicators for selecting city walk neighborhoods. Taking Singapore as a case study, the research identifies neighborhoods with high potential for city walk experiences and visualizes walking routes using ArcGIS10.8.1 network analysis tools. The case study demonstrates the feasibility and applicability of the proposed methodological framework, offering practical insights for urban design and place-based spatial planning.

1. Introduction

City walk refers to a short-term urban activity in which participants explore city neighborhoods on foot [1]. It has recently gained popularity as it meets the leisure demands of contemporary young people who experience fast-paced and fragmented daily schedules [2]. Meanwhile, the increasing verticalization of modern cities has limited people’s engagement with urban spaces. Developing “CityWalks”-oriented urban forms that encourage people to move from indoor to outdoor environments has thus become a new direction for global urban development [3]. Unlike traditional tourism, city walk—characterized by walking as the primary mode of travel—emphasizes the agency of participants during the travel process [2]. Walkers can adjust their pace to fully enjoy spatial and temporal freedom [4], thereby exercising the “right to slow down” [5]. Through bodily practices, sensory experiences, and imagination, walkers construct spatial meanings [6], which resonate with discussions on the space–place dialectic and the processes of place formation [7]. Therefore, city walk serves as an important practical pathway through which walkers, within limited time–space conditions, can rapidly perceive and understand the characteristics and placeness of unfamiliar urban environments.

City walks are usually conducted at the neighborhood scale. Since factors such as personal time and energy impose constraints on walking activities, the neighborhood environment becomes crucial in shaping walking experiences from a place-based perspective [8]. For instance, diverse land-use patterns may enhance walkers’ understanding of local culture [9]. Hence, identifying neighborhoods with strong placeness value for city walk activities has become a key issue that merits exploration.

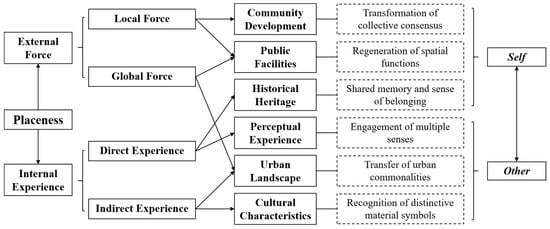

From the perspective of humanistic geography, the roles of different agents in the formation of placeness should not be overlooked. Local residents, as the self, and visitors, as the other, possess distinct sources of subjective experience and thus influence placeness formation differently. While local residents emphasize the historical development of place, visitors tend to focus on visible cultural elements and sensory experiences. Through different perceptual pathways, both groups jointly participate in and shape urban placeness. Integrating these two perspectives helps to combine direct and indirect experiences, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of place within a shorter time frame.

In contrast, structuralist geography focuses mainly on the external forces shaping placeness, paying less attention to differences among subjects. Beyond direct and indirect experiences, it proposes another logic of placeness formation—through the interaction between global and local dynamics. Each theoretical approach offers distinct insights, and together they provide a complementary framework for understanding placeness practices.

Therefore, this study integrates these two theoretical perspectives, incorporating both subjective diversity and external forces into a unified analytical framework of placeness. It develops an evaluation system of placeness that serves as the basis for neighborhood selection and route design in city walk studies. Methodologically, the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic model is employed to identify key placeness evaluation elements from the perspectives of both self and other Drawing on the theoretical synthesis of humanistic and structuralist geography, a set of neighborhood-level placeness evaluation indicators is constructed. Based on fieldwork conducted in 2023 and 2024, Singapore is used as a case study to identify neighborhoods suitable for city walk activities. The Chinatown neighborhood is further selected as a representative example, where walking routes are visualized using ArcGIS network analysis tools.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the theoretical differences and connections between the understandings of placeness in humanistic and structuralist geography, and discusses how the concept of placeness can be interpreted through city walk practices. Section 3 introduces the case selection, data sources, and methodological framework, including the LDA-based placeness evaluation and network analysis for route design. Section 4 presents the design results of the placeness evaluation framework. Based on the theoretical synthesis and methodological procedures introduced earlier, this section constructs a multi-dimensional indicator framework for assessing neighborhood placeness. Section 5 applies the proposed framework to Singapore, evaluating neighborhood placeness from both self and other perspectives and visualizing city walk routes using ArcGIS network analysis, with Chinatown serving as a detailed case study. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Differences in the Mechanisms of Placeness Formation Under Two Theoretical Perspectives

Place is one of the core concepts in human geography, and the distinctiveness that differentiates one place from another constitutes its placeness [10]. Both humanistic and structuralist geographies focus on the essential characteristics of place specificity, yet they interpret the mechanisms of its formation differently [11,12,13].

Humanistic geography emphasizes the role of the subject in the formation of placeness [14]. Individuals have emotional needs toward place [15], and place is inseparable from human consciousness [16]. Thus, placeness is not merely a geographical phenomenon but a manifestation of rich human experiences [17]. Since experiences vary among individuals, their perceptions and identifications of the same place also differ, leading to diverse descriptions of placeness [18]. The three epistemological characteristics of humanism—self-oriented thinking, emotional expression, and perceptual understanding [19]—help explain how placeness is formed through subjective experience.

First, different cognitive subjects (the self) perceive spatial objects differently based on their experiential foundations. Second, varying personal experiences lead to divergent emotional responses toward the same spatial object, resulting in heterogeneous understandings. Finally, through both experiential and transcendental thinking, the subject’s insight transforms space into a place with which emotional attachment is established—thus generating placeness.

Accordingly, the perceptions of the self (locals) and the other (visitors) toward a given place inevitably diverge, as they stem from distinct emotional experiences. Sense of place refers to the cognition and attachment to place formed by individuals or groups through affective experience and meaning-making, which enriches the connotation of placeness via social practices and personal experience. Yi-Fu Tuan attributed such differences to variations in emotional attachment and identification with space [20]. For example, the same place may be perceived as a “home” by the self but as a “tourist site” by the other, reflecting underlying cultural distinctions between groups [21].

Local residents, as the self, develop shared understandings of place through collective living, which are reflected in the local landscape and spatial knowledge [22]. Visitors, as the other, often construct their sense of place indirectly through mediated experiences rather than direct familiarity, forming attachments during processes of mobility and temporary dwelling [23]. Tourism, as a manifestation of human subjectivity, requires the local cultural system to undergo certain adjustments and negotiations between residents’ and visitors’ imaginations of place [21].

Fried [24] noted that sense of place is discontinuous—environmental change can cause the loss of emotional attachment—implying that placeness is both stable and fragile. Lewicka further argued that placeness derived from place attachment depends on spatial scale; long-term residence, social ties, and historical–cultural attributes are key determinants. For outsiders lacking prolonged residence, indirect experiences alone are insufficient for grasping local characteristics; they must shift observational perspectives through direct spatial engagement, attempting to view place as if they were insiders.

Gustafson proposed a tripartite framework to interpret the multiple meanings of sense of place from the dimensions of self, others, and environment [25], discussing how place relates to personal identity, how social relations influence spatial perception, and how the physical environment shapes place meanings. Although this framework includes the perspective of others it refers primarily to “others within local society”—that is, other members of the community rather than external visitors. How the external other can rapidly form a relatively comprehensive understanding of placeness through the combination of direct and indirect experience remains a question for further discussion.

With growing reflection on the subjectivism of humanistic geography, some scholars have turned to structural perspectives to reassess the formation mechanisms of placeness. Structuralist geography posits that placeness is independent of individual emotional attachment or subjective consciousness [15]; instead, it arises from functional interdependencies among regional subsystems [26]. From this perspective, placeness is shaped not only by location or natural conditions but also by the broader global political and economic order [27]. Thus, placeness should be analyzed within an encompassing social framework rather than solely as a product of personal experience [28].

Structuralist interpretations of placeness formation focus on spatial interrelations—that is, the internal logic among geographical phenomena—and reject isolated, localized analyses [29]. Furthermore, geographical phenomena are determined by underlying social structures, requiring attention to deep-seated forces such as national policies, globalization, and tourism-driven restructuring, alongside non-structural dynamics like community relations and migrant interactions [28]. Finally, placeness formation must be understood through the complex interactions operating across multiple spatial scales.

2.2. Connections Between the Two Theoretical Perspectives

Completely denying the role of human agency in social and historical contexts is evidently one-sided [29]. The real world is complex and multifaceted; therefore, reconciling both perspectives is essential for understanding placeness formation. In fact, when humanistic geography introduces the concepts of the self and the other it implicitly reflects the relational logic between global and local, and between native and foreign forces—linking it conceptually to the structuralist concern with external dynamics. The two theoretical approaches are thus complementary rather than oppositional in explaining the genesis of placeness. Specifically, the humanistic perspective highlights how individuals construct meaning through embodied experience, while the structuralist perspective emphasizes how broader political–economic forces shape the conditions under which such meanings emerge. The formation of placeness therefore results from the interplay between subjective attachment and objective constraints, rather than from either dimension alone.

Humanistic geography typically defines local residents as the self and non-resident outsiders as the other [20]. The difference between these perspectives stems not only from experiential pathways but also from structural forces. For example, locals’ perceptions of place are shaped by their embeddedness in community networks, whereas travelers’ entry into a place as others embodies global and structural processes—such as globalization and tourism—that intervene in and reconstruct place [28]. Moreover, individuals may shift between the two roles through migration or mobility, suggesting that self and other should be understood as situational rather than fixed identities. Ultimately, the formation of placeness must be examined through the heterogeneity of both experiential and structural sources. This duality implies that internal experience and external force are not separate analytical domains but mutually constitutive processes that jointly produce place meanings.

Soja’s concept of the Thirdspace [30] further underscores the complexity of space and place. The Firstspace refers to the objective physical environment (e.g., buildings and streets); the Secondspace involves imagined or symbolic representations, emphasizing how people interpret space through language and culture; and the Thirdspace integrates both, constituting a field where material and experiential dimensions coexist. Here, spatial meanings are co-produced through history, culture, and power relations. Under globalization, place development is influenced by transnational capital flows, technological diffusion, and cultural exchanges, making it no longer dependent solely on local resources. The interaction between global forces and local resources transforms place into a hybrid space imbued with multiple meanings. Although Soja’s Thirdspace does not explicitly differentiate cognitive perspectives based on experiential origins [31], it highlights the need to synthesize humanistic and structuralist viewpoints when evaluating placeness, thereby constructing a framework that accounts for both experiential diversity and structural dynamics. In other words, Thirdspace functions not as a third independent paradigm but as a meta-framework that accommodates the experiential emphasis of humanistic geography and the structural explanations of structuralist geography within a single interpretive space. By positioning placeness within Thirdspace, this study conceptualizes it as an emergent outcome of internal experience, material conditions, and external forces—thus clarifying the logical relationship among the three theoretical components.

2.3. Interpreting Placeness Through City Walk

Compared with traditional tourism, city walk is characterized by two main features. First, it typically lasts only half a day, requiring less time and energy. Second, it focuses on a segment of the urban environment—often at the neighborhood scale—and reinterprets the urban image through thematic narration, thereby exhibiting a trend of de-scenicization [6].

Urban neighborhoods are vital carriers of placeness. They function not only as conduits for pedestrian and material flows but also as everyday spaces for residents’ social interactions, ultimately forming the emotional dimension of sense of place. During a city walk, individuals can determine their own walking pace [3], freely observe their surroundings, and thereby strengthen subjective perception and place identity. Unlike tourist attractions, neighborhoods embody both cultural and social functions [32]; they serve as “windows” through which walkers perceive urban characteristics [33], offering spaces for interaction between local selves and visiting others. This enables walkers to understand the city from multiple perspectives.

Neighborhoods also respond to the intersections of local and global forces. World cities with global economic and cultural influence often display distinctive spatial forms [34], such as the coexistence of corporate clusters, traditional markets, and ethnically diverse social spaces shaped by transnational migration. These types of globalized urban spaces are interrelated rather than isolated, and they emerge through interactive rather than singular processes. Through walking observation, the dynamic transitions between different spatial zones can be perceived in real time, transforming the urban structure from a static form into a processual understanding—helping to deconstruct the logic of urban spatial formation.

Modern urban spaces are often iterative creations built upon historical layers; the historical elements accumulated during urban development remain integral to the spatial fabric of neighborhoods. By observing such elements, walkers can trace urban evolution longitudinally and gain deeper insights into city-specific characteristics. Hence, despite temporal and spatial limitations, well-selected and thematically designed walking routes across representative neighborhoods can help walkers grasp the core features of a city and interpret its placeness.

Although placeness theory has been applied in studies of tourist destination image and visitor identity [15,35], its use in research on neighborhood selection and route design for city walk remains limited. Conventional tourism geography studies often employ GIS grid analysis [36] and shortest-path algorithms [37] for route planning. While these methods assist in designing intra-neighborhood routes, there is still a lack of research on identifying neighborhoods with high walking value at the city scale.

From an applied perspective, this scale of analysis provides a scientific basis for urban construction and neighborhood renewal. First, these spatial methods primarily focus on quantifiable attributes such as accessibility, distance, or service density, and thus overlook the experiential, symbolic, and socio-cultural dimensions that are central to placeness. Second, most studies operate at a fine spatial scale and are unable to identify neighborhoods with high walking value across the city as a whole, leaving a methodological gap at the city-scale selection stage. Third, although there are some conventional approaches incorporate user-generated content, especially in tourism studies, they rarely combine visitors’ perspectives with locals’ lived experiences. As a result, evaluations may fail to capture how walkers perceive, engage with, or attach meaning to urban spaces in a multidimensional manner. From an applied perspective, addressing these limitations is essential for developing a more comprehensive approach to city-walk planning. Therefore, this study proposes a framework that integrates LDA-based thematic extraction with placeness theory to overcome these shortcomings and support evidence-based identification of walkable neighborhoods.

City walk represents a process of spatial re-cognition and re-production [38], carrying intrinsic geographical significance. First, as a behavioral–geographical process, it reflects how individuals perceive and experience localized urban spaces through bodily senses [39], embodying the cultural–geographical implications of placeness. Second, city walk offers both residents and visitors spatial modes of cognition and exploration grounded in personal goals, influencing not only individual understandings and practices of urban space but also informing urban preservation, renewal, and development. Selecting neighborhoods for city walk based on placeness theory allows walkers to efficiently capture core urban features within limited time, while also providing urban planners with a framework to identify and preserve neighborhoods of significant placeness value.

3. Case Selection and Research Methods

3.1. Case Selection

This study takes Singapore as the case for city walk neighborhood selection and route design, based on two main considerations. First, after Singapore implemented a visa-free policy for holders of ordinary Chinese passports, the number of Chinese tourists increased significantly, providing opportunities for city walk practices among visitors. Second, as a city-state, Singapore’s unique spatial structure and urban characteristics have emerged from the interplay of globalization and localization forces. The coexistence of global, national, urban, and neighborhood-scale landscapes within a relatively compact territory enables travelers to perceive urban placeness while also making Singapore an ideal site for examining the mechanisms of placeness construction through city walks.

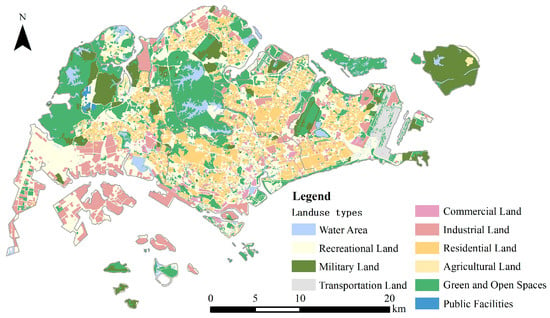

Driven by global economic forces and its own open policies, Singapore has attracted large inflows of foreign investment, rapidly integrating into the global economy and becoming an international financial center that draws increasing numbers of immigrants. The first space—its physical urban structure (Figure 1)—has undergone profound transformations, forming globally oriented and modern business, financial, and commercial districts such as Marina Bay Financial Centre, Raffles Place, and Orchard Road.

Figure 1.

The physical urban structure of Singapore.

Meanwhile, Singapore—home to diverse ethnic groups such as Chinese, Malays, and Indians—has maintained plural cultural traditions and lifestyles through policy guidance and cultural inclusiveness. Ethnic neighborhoods such as Little India, Chinatown, and Kampong Gelam have developed around distinct cultural identities, while the “Garden City” image has reshaped people’s perceptions and imaginations of place, forming the second space. As a typical example where globalization and local identity coexist, Singapore not only illustrates how global forces transform urban space and economic structures, but also how local cultures maintain and reconstruct their identities within global flows—creating a complex third space where globalization and placeness intersect.

3.2. Neighborhood Selection

This study focuses on the formation of placeness through the interaction between self and other perspectives. The self refers to local residents, while the other represents tourists or temporary visitors. Influenced by their differing experiences and motivational sources, these two groups perceive and evaluate places differently, yet jointly contribute to the construction of placeness.

Online textual data, as a form of user-generated content (UGC), can authentically reflect users’ narratives and perceptions of places from different identity positions. This study employs the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic model to identify latent themes within online textual data and construct placeness evaluation indicators for assessing urban neighborhoods.

3.2.1. LDA Topic Model and Evaluation

The LDA model, a three-layer Bayesian probabilistic generative model, is widely used in textual analysis. It assumes that a document is a probability distribution over topics, and a topic is a probability distribution over words [40]. The probability of a word w appearing in a document is defined as follows:

Here, the topic vector and word vector follow Dirichlet priors with parameters and , respectively. w stands for word and t stands for topic. The joint probability distribution can thus be expressed as:

Intuitively, LDA assumes that a document is composed of multiple latent topics, and each topic is a distribution over words. When generating a document, the model first chooses a topic according to the topic distribution of the document, and then draws a word according to the word distribution of that topic. Thus, the goal of LDA is to reverse-engineer these hidden distributions. means how much each topic contributes to a document; means how strongly each word is associated with a topic.

To estimate these latent distributions, Gibbs sampling is employed. The posterior probability distribution is obtained as:

where denotes the number of words in document m not assigned to topic k; denotes the number of times word t is not assigned to topic k; denotes the number of unassigned feature words across topics in the news document; and denotes the number of times each feature word under topic k is unassigned. Based on known data and generation rules, parameter estimation yields the maximum values of the hyperparameters α and β, thereby uncovering latent thematic structures in the corpus.

The perplexity and log-likelihood metrics are commonly used to assess model performance and determine the optimal number of topics. The perplexity of an LDA model is defined as:

where M is the number of documents, is the number of words in document d, and p() is the likelihood of document d. Lower perplexity indicates a better model fit, while higher log-likelihood suggests improved model performance.

The parameter selection for the LDA model (e.g., number of topics and hyperparameters) is determined through a combination of perplexity, log-likelihood trends, and topic coherence, supplemented with qualitative inspection to ensure semantic clarity. This mixed evaluation strategy helps reduce overfitting and improves the interpretability of topic structures derived from potentially biased UGC data.

3.2.2. Data Sources

The self perspective textual data were collected from the My Community official website (https://mycommunity.org.sg/ accessed on 3 April 2024) under the Guided Tour section. My Community is a non-profit organization dedicated to documenting social memory, celebrating civic life, and promoting the preservation of community art and cultural heritage. It organizes guided tours, exhibitions, festivals, and place-making projects to encourage civic participation in cultural management and urban governance. Eighteen articles introducing community activities and heritage walk routes were collected from this website, totaling 54,705 words and covering 18 neighborhoods or sites (Table 1).

Table 1.

The sample neighborhoods or sites selected for self perspective placeness evaluation.

The other perspective textual data were obtained from tourist reviews on Ctrip (https://www.ctrip.com/), a leading Chinese online travel platform. As a form of online travel narrative, these reviews authentically reflect tourists’ perceptions and emotional identification within specific sociocultural contexts [41]. Ctrip data are widely used in geography and tourism research due to their reliability and representativeness [42].

Considering the functional heterogeneity of Singapore’s districts, five neighborhoods or attractions were selected from each of the following categories based on the self perspective sample: (1) public/commercial areas, (2) mixed entertainment zones, (3) historic-cultural districts, and (4) ecological and leisure spaces (Table 2). A total of 20 neighborhood samples were then matched with corresponding tourist reviews from Ctrip.

Table 2.

The sample neighborhoods or sites selected for other perspective placeness evaluation.

Although the self and other textual samples do not fully overlap, the focus of the LDA analysis is to identify placeness-related semantic features from different perspectives rather than to conduct direct spatial comparisons. Therefore, variations in neighborhood samples do not affect the validity or interpretability of the evaluation results. To ensure data quality, up to 200 top-ranked reviews were collected for each location (or all reviews if fewer than 200), yielding 2262 valid comments after deduplication and cleaning. The selection of MyCommunity and Ctrip reviews was motivated by their representativeness for two distinct groups: local residents (MyCommunity) and Chinese-speaking international tourists (Ctrip). However, relying on these platforms inevitably introduces data biases related to cultural preferences, travel styles, and expression habits. These perceptual differences may influence the relative prominence of certain themes in the LDA outputs. Given the limitations of data availability, this study was unable to triangulate findings with additional platforms (e.g., TripAdvisor, Google Reviews) or official survey data. Nevertheless, the dual-source design still captures two important and differentiated perspectives—resident-based (self) and visitor-based (other)—which helps partially mitigate single-source bias. Future research may enhance generalizability by integrating multi-platform data or combining UGC with structured survey instruments.

All user-generated content (UGC) data employed in this study were collected from publicly accessible online platforms. Only review text and non-identifiable metadata were used, and no personally identifiable information was collected, stored, or processed at any stage. The analysis was conducted on aggregated textual data, ensuring that individual users cannot be traced or re-identified. Data collection and use strictly followed the platforms’ terms of service and complied with institutional ethical guidelines for research involving publicly available online information. Therefore, the study poses minimal risk with respect to privacy and data protection.

3.3. Route Design Within Neighborhoods: Network Analysis

As city walkers explore neighborhoods primarily on foot, this study uses ArcGIS Network Analysis to plan optimal walking routes. The “Best Path Planning” tool in ArcGIS calculates the most efficient route from a starting point to an endpoint based on given constraints and objectives. The network model comprises two main elements—edges (streets or paths) and junctions (nodes such as intersections or key walking points). The road network data were obtained from OpenStreetMap.

Because walking is not influenced by vehicular congestion, this study focuses primarily on distance cost in route selection. Under the constraint of avoiding repeated paths, the Dijkstra algorithm is applied to determine the shortest path, which is considered the optimal walking route. The Dijkstra algorithm is expressed as:

where denotes the total cost of path P, e represents each edge (road segment), and is the distance weight of edge e. Assuming a walking speed of 60 m/min, the study also estimates walking time within neighborhoods, excluding stops for observation. Since most streets within the neighborhoods are pedestrian-oriented and exhibit minimal variation in slope, road hierarchy, and pavement quality, these factors were not modeled explicitly. Given this relatively homogeneous streetscape environment, walking-time estimation was based primarily on distance rather than differentiated street attributes.

4. Results of the Placeness Evaluation Framework Design

4.1. Results of the LDA Model

Using Python 3.8, the study employed the nltk and jieba language processing libraries to segment the textual data collected from My Community and Ctrip Travel. The document collections were then vectorized using standard vectorization tools. After multiple calibration tests, the key parameters of the LDA models for both the self and other perspectives were set as α = 0.5 and β = 0.01, with 20 iterations.

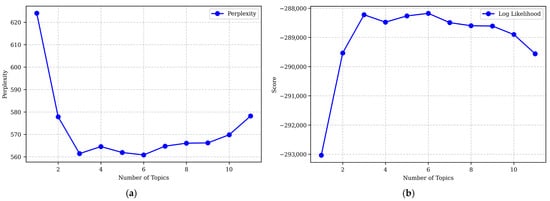

The study evaluated model fit across candidate topic numbers using perplexity and log-likelihood as quantitative indicators of predictive performance, and complemented them with topic-coherence scores and manual inspection to ensure semantic interpretability. Perplexity is a monotonic transformation of the held-out log-likelihood; lower perplexity and higher log-likelihood generally indicate better generalization. However, prior studies have emphasized that the absolute extremum of these metrics often does not correspond to the most semantically coherent or robust topic structure, and that sharp fluctuations in perplexity or log-likelihood signal model instability rather than genuine improvement [43,44]. Consequently, these metrics should be interpreted in terms of trend continuity rather than point estimates.

For the self perspective model (Figure 2), perplexity reached its minimum and log-likelihood its maximum at , but both curves exhibited a sudden and discontinuous change when , indicating overfitting and reduced model stability. For the other perspective model (Figure 3), perplexity and log-likelihood achieved their optimal point at , while values for changed more gradually and remained unstable at higher topic numbers.

Figure 2.

(a) The perplexity results of self perspective LDA model. (b) The likelihood results of self perspective LDA model.

Figure 3.

(a) The perplexity results of other perspective LDA model. (b) The likelihood results of other perspective LDA model.

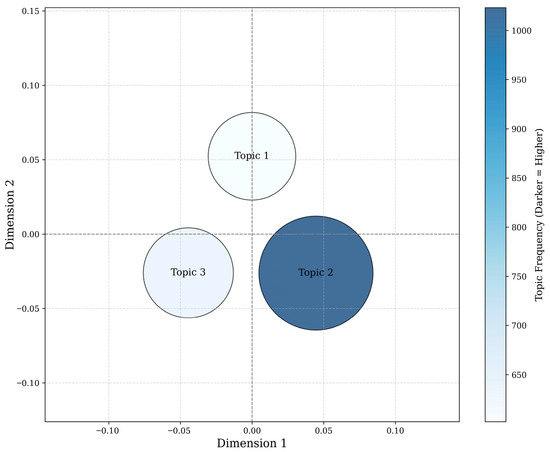

Given that abrupt improvements followed by immediate deterioration are typically regarded as indicators of unreliable model behavior rather than meaningful structural information, we prioritized parameter stability and semantic clarity over numerical extremum. Across both models, provided (1) smoother perplexity and log-likelihood trajectories, (2) higher topic coherence, and (3) clearer and non-overlapping semantic themes during manual inspection. Therefore, was selected as the optimal and most robust topic number for both models.

To verify the model’s effectiveness at k = 3, a two-dimensional visualization of the document–topic hierarchy was generated. The results showed that the three topics were clearly separated without overlap (Figure 4 and Figure 5), confirming that three topics provide a valid thematic structure for both the self and other perspectives.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional visualization of the document–topic hierarchy in the LDA model from the self perspective (k = 3).

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional visualization of the document–topic hierarchy in the LDA model from the other perspective (k = 3).

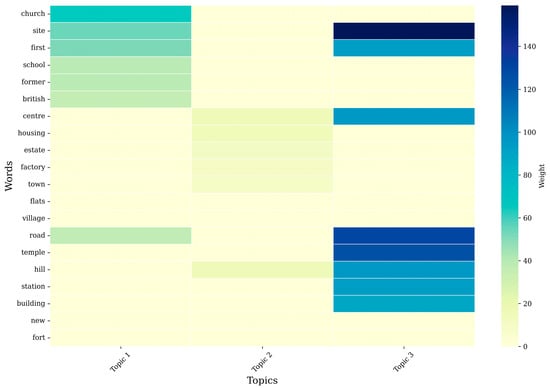

At the topic–word level, meaningless conjunctions, quantifiers, pronouns, and specific place names (e.g., “also”, “would”, “Tanglin”; “一个 (one)”, “这里 (there)”, “可以 (can)”) were removed. Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the top 20 high-frequency words and their topic associations.

Figure 6.

Heatmap of the topic–word hierarchy in the LDA model from the self perspective.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of the topic–word hierarchy in the LDA model from the other perspective.

For the self perspective model,

- Topic 1 contains high-frequency words such as church, site, first, school, former, British, and road. The frequent occurrence of British may be related to Singapore’s colonial past, while words such as church, site, and school indicate the importance of religious institutions, heritage sites, and historical schools in shaping local placeness under a multicultural background.

- Topic 2 includes words such as centre, housing, estate, factory, town, and hill, reflecting attention to land use patterns and urban functions. The frequent appearance of centre and town highlights the central business district’s and functional zones’ roles in the construction of placeness.

- Topic 3 features words such as site, first, road, temple, centre, station, building, new, and fort, emphasizing public infrastructure and the transformation of urban landmarks in the contemporary context.

Accordingly, the self perspective’s placeness themes can be summarized as historical heritage, community development, and public facilities.

For the other perspective model,

- Topic 1 includes high-frequency words such as India, feeling, culture, exotic, special, and lively. These words suggest tourists’ impressions of Singapore’s multi-ethnic culture, where India and culture point to ethnic enclaves and special or lively describe sensory engagement with cultural diversity.

- Topic 2 contains garden, park, bay, attraction, plants, hotel, and light, emphasizing the “Garden City” image of modern Singapore, which reshapes visitors’ imagination and perception of place.

- Topic 3 includes architecture, food, bar, night, specialty, lively, and restaurant, reflecting tourists’ multisensory experiences related to taste, sound, and vision, as well as encounters with local cuisine and artistic culture.

Thus, the other perspective’s placeness themes can be summarized as cultural characteristics, urban landscape, and perceptual experience.

In summary, through the LDA-based textual analysis, this study identified six core thematic dimensions of urban placeness: (1) Historical heritage, (2) Community development, (3) Public facilities, (4) Cultural characteristics, (5) Urban landscape, and (6) Perceptual experience. These themes reveal how residents (the self) and tourists (the other) perceive and co-construct the city’s placeness through distinct yet complementary discursive frameworks.

The six thematic dimensions were derived through an iterative coding process that combined LDA topic modeling with qualitative interpretation. After generating latent topics through LDA, members of the research team independently reviewed representative keywords and sample texts for each topic. The coding criteria for assigning topics to thematic dimensions were based on theoretical definitions of placeness, and the semantic convergence of high-probability words within each topic. Coding decisions were then jointly discussed among the research team to reach consensus, and discrepancies were resolved through group deliberation rather than relying on a single coder. This collaborative cross-checking process helped reduce subjectivity and enhance the reliability of theme construction.

4.2. Interpretation and Indicator Construction of Placeness Evaluation

4.2.1. Historical Heritage

Local residents are often deeply familiar with the historical and cultural evolution of their communities. Compared with the other perspective, which tends to emphasize globally renowned heritage sites, the self perspective highlights historically significant landmarks tied to residents’ daily lives. For instance, My Community published an article introducing the Tanglin Halt neighborhood and proposed a “Cultural Heritage Trail” connecting Singapore’s first public housing estate, first library branch, first polyclinic, and first neighborhood sports complex—all of which hold symbolic and emotional meaning for local residents. A long-term resident M recalled:

“I could grow vegetables, rear chickens and fruit trees at the open space in front of my house. My neighbour would then rear tilapia, goldfish—all types of fishes. He used to have a Christmas tree that was around 10 m tall!”

Another resident N, who served as a librarian at the first branch library from 1982, said,

“Throughout the years, many ex-residents have returned to the library and bought us kueh kueh even though they have shifted out of the estate. Besides being an identity marker, the library certainly holds fond memories for past and present residents.”

These narratives embody the humanistic epistemology in which affective perception connects people and space, transforming locations into emotionally charged places. Shared experiences among residents—such as collective memories of living in public housing—help foster a sense of communal identity [45]. Therefore, indicators such as the age of neighborhoods and the presence of heritage sites can reflect placeness in the self perspective, emphasizing the emotional bonds between residents and local history.

4.2.2. Community Development

Modern urban spaces evolve through iterative accumulation of historical elements, making community development a processual manifestation of place-making. From a structuralist geographical viewpoint, both structural forces (e.g., state policy) and non-structural forces (e.g., community relations, narratives) jointly influence placeness formation [28]. Taking Redhill as an example, the neighborhood has transformed from a self-sufficient village into a modern satellite town. The non-structural force is represented by the local Malay legend of Sejarah Melayu, which tells of a boy who saved villagers from swordfish attacks but was later executed out of jealousy—his blood staining the hill red. The legend celebrates sacrifice and heroism, forming the emotional basis for local identity among “those who call Redhill home”.

Meanwhile, structural forces are reflected in state-led urban renewal. In celebration of Singapore’s 50th anniversary, the Prime Minister launched a redevelopment initiative to build inclusive public spaces in Redhill, stating that,

“We must continue to build a more inclusive society, valuing everyone and promoting active citizenship.”

This illustrates how both bottom-up narratives and top-down planning interact to produce new collective meanings—such as “inclusiveness” and “civic consciousness”—in the evolution of community-based placeness.

4.2.3. Public Facilities

Globalization and extra-local forces also shape the self perspective of placeness. The establishment and transformation of public facilities often reflect a locality’s embeddedness in global economic and cultural networks. For example, during the colonial period, the warehouses along the Singapore River served as key nodes in the British free-trade port’s logistics system. However, with the global shift toward containerized shipping in the 1970s, the river could no longer accommodate large vessels, prompting spatial and functional transformations of the area.

“Today, Clarke Quay and Robertson Quay have been revitalised into bustling entertainment and commercial districts that offer quality dining options and a vibrant night life.”

This transformation exemplifies urban deindustrialization and port relocation under global restructuring. Both national urban revitalization plans (structural forces) and private market participation (non-structural forces) contributed to this spatial regeneration and the reconfiguration of local placeness. Thus, the existence of large-scale public facilities, special land-use functions, and international investment projects can serve as indicators capturing the interplay between global and local forces in shaping placeness.

4.2.4. Cultural Characteristics

Tourists, as the other, typically possess limited firsthand knowledge of a place and rely on indirect experiences to form their perceptions. They are often drawn to distinctive cultural features that differentiate one city from another.

Singapore’s multicultural composition—shaped by its immigrant history—creates unique ethnic enclaves that attract visitors seeking diverse cultural experiences:

“Kampong Glam has a strong Islamic atmosphere.”

“Holland Village’s European-style architecture reflects its early expatriate settlers.”

“Little India amazed me—it’s my first time seeing a Hindu temple, and the Indian vibe is everywhere.”

Because the dataset was drawn from Ctrip, a major Chinese travel platform, it can be inferred that many reviewers have limited direct experience with Islamic, Dutch, or Indian cultures. Their perceptions of “exotic” culture rely on symbolic representations and media-based imaginaries, such as mosques, spices, or murals. These visual and material symbols become mediators through which tourists rapidly recognize cultural differences and construct their sense of placeness.

Hence, iconic cultural elements, local crafts, and ethnic architecture are important indicators for evaluating cultural placeness from the other perspective.

4.2.5. Urban Landscape

The visual similarity among global cities allows tourists to transfer their lived experiences from familiar to unfamiliar urban contexts. This intertextual comparison shapes their understanding of place:

“The bay at night reminds me of Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour or Shanghai’s Bund.”

“The Singapore River is like Shanghai’s Huangpu River—the mother river connecting finance, politics, and culture.”

Such comparisons reveal how global cityscapes facilitate meaning-making through analogy. Furthermore, the use of symbolic labels—such as the “Garden City” identity—enables visitors to ascribe coherent meaning to spatial experiences:

“The Singapore Botanic Gardens played a vital role in the Garden City movement—it’s truly beautiful!”

“Marina Bay Park fully deserves its reputation as part of the Garden City.”

“Jewel Changi is breathtaking—the greenery makes you feel refreshed even from afar.”

These comments demonstrate how physical landscapes and symbolic labels intertwine in the construction of urban placeness. Therefore, landmark uniqueness, landscape connectivity, and alignment with symbolic urban identities can be key indicators of urban landscape placeness.

4.2.6. Perceptual Experience

Perceptual experience represents the most immediate way for the other to engage with a place. It extends beyond visual impressions to include multisensory perceptions such as smell, sound, and taste:

“Visiting Little India feels like being in New Delhi—the colors are vibrant, and the air is filled with the scent of curry and spices.”

“The night view at Clarke Quay is stunning—the river breeze carries a sweet fragrance as you enjoy drinks and music.”

“The Sichuan restaurant’s aroma of chili and pepper adds to the local charm.”

These descriptions show how tourists employ multiple senses to acquire direct experiences and thereby construct placeness. Thus, the number of restaurants, shopping malls, and entertainment venues can serve as quantitative indicators of perceptual experience, representing how sensory engagement fosters the other’s construction of placeness.

Figure 8 illustrates the mechanism of placeness formation through the interaction between the self and the other. The analytical framework integrates humanistic and structuralist geographical theories by emphasizing two dimensions: (1) the difference between direct and indirect experience, and (2) the relationship between local and global forces. Through these intersecting logics, both residents and tourists co-produce urban placeness via distinct thematic pathways.

Figure 8.

Mechanism of Placeness Formation Based on the Interaction Between Internal Experience and External Force.

On the experiential side, the self as residents, constructs placeness primarily through direct internal experience, accumulated through long-term everyday life in the locality. In contrast, the other, as visitors, forms placeness largely through indirect internal experience, drawing on symbolic cultural representations and the meanings transported from other places. On the structural side, the external forces shaping placeness also diverge between the self and the other: the placeness of local residents is influenced mainly by locally rooted forces, whereas visitors are more strongly shaped by global forces that frame their perception and interpretation of the place. The mechanism therefore demonstrates that placeness is not produced by internal experience alone nor determined solely by external forces. Instead, it arises from their interaction across self–other positionalities. The model clarifies how humanistic and structuralist perspectives complement each other and provides the theoretical foundation for the empirical analysis in this study.

Based on this dual-perspective framework, the study further operationalized the six thematic dimensions into measurable indicators (Table 3). The selected indicators were derived from the LDA results and grounded in the mechanism of placeness formation. Actually, indicators such as the number of restaurants or the presence of heritage sites are commonly used in urban-geography and tourism studies as proxies for placeness or urban vitality [46,47]. Thus, the operationalization of the study draws not only on thematic content derived from UGC and LDA analysis, but also on empirically validated measures in prior research.

Table 3.

Indicators for Placeness Evaluation.

5. Neighborhood Selection and Route Design for City Walk in Singapore

5.1. Evaluation of Neighborhood Placeness

Neighborhoods were selected using the placeness evaluation indicators developed earlier. Since the original sample contained entities at both neighborhood and attraction scales, attractions with similar cultural and landscape characteristics were merged into corresponding neighborhoods to meet the spatial granularity requirements of city walk design. After removing duplicates and cases with incomplete evaluation information, 20 neighborhoods remained as final samples (Table 4). Although the Southern Islands occupy a large total area, they exhibit high landscape homogeneity and were thus evaluated as a single entity. Data for the indicators were obtained from fieldwork conducted in 2023 and 2024, supplemented by official sources such as the National Heritage Board, Singapore Tourism Board, and Singapore Economic Development Board, as well as user-generated data from Ctrip and Google Maps. While the selected neighborhoods vary in spatial extent and functional composition, UGC reviews are spatially anchored to specific POIs, and the extracted LDA themes represent conceptual rather than purely spatial dimensions of placeness. Therefore, despite minor spatial misalignment, the thematic outputs remain comparable across neighborhoods.

Table 4.

Sample Neighborhoods for Evaluating Sense of Place in Singapore City Walk.

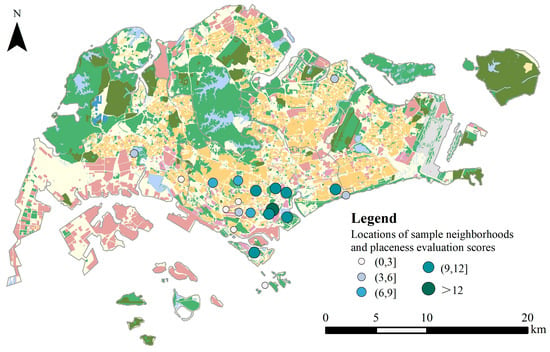

Each neighborhood was assessed using the indicators in Table 3. To eliminate dimensional effects, the data were normalized, resulting in a total score of 18, with 9 points each representing the self and other perspectives. The results are presented in Table 5 and Figure 9 and Figure 10. To ensure the robustness of the composite placeness scores, two sensitivity checks were conducted. First, the normalization method was varied by replacing Min–Max scaling with Z-score standardization. The resulting neighborhood rankings remained highly consistent, indicating that the index is not sensitive to alternative scaling choices. Second, a leave-one-out test was performed by removing each indicator individually and recalculating the placeness index. The top-ranked neighborhoods showed minimal variation across all scenarios, suggesting that no single indicator disproportionately drives the results. These robustness checks confirm the stability of the highest-scoring neighborhoods identified in this study.

Table 5.

Evaluation Results of Placeness in Sample Neighborhoods of Singapore.

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of neighborhoods and results of the placeness evaluation. Landuse colors are the same as in Figure 1.

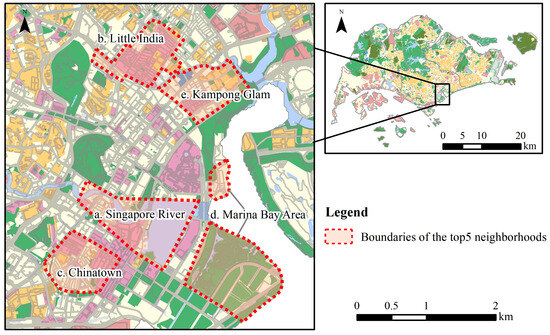

Figure 10.

Map of the top five neighborhoods ranked by placeness scores. Landuse colors are the same as in Figure 1.

Among all neighborhoods, the Singapore River and its surrounding area scored the highest in both overall placeness and the insider-perspective evaluation. Located in the city center, the 3.2 km-long Singapore River—stretching from Boat Quay through Clarke Quay and Robertson Quay to Marina Bay—is the birthplace of modern Singapore. It serves not only as a natural waterway but also as a witness to the nation’s collective memory and global transformation. Public spaces such as bridges and quays along the river embody the process of functional regeneration under the interaction of global and local forces—“the story of the Singapore River is one of transformation…it mirrors Singapore’s evolution from a fishing village to a vibrant metropolis and global city” (Urban Redevelopment Authority). From the self’s perspective, the river area carries shared memories and collective identity—“though the interiors of these buildings have greatly changed, they retain the façades of old warehouses and are painted with bright colors to enliven the area” (My Community). Developers preserved architectural features while introducing commercial facilities, showing respect for the self’s sense of memory and placeness. Simultaneously, this design facilitates the other’s construction of placeness—“allowing visitors a glimpse of the river’s historic charm” (URA), helping them quickly acquire direct experiential knowledge. This case exemplifies the structuralist notion of placeness as shaped by the interplay of global and local forces, as well as the convergence of insider and outsider perspectives.

Neighborhoods such as Little India, Chinatown, and Kampong Glam, historically inhabited by Chinese, Indian, and Malay-Muslim communities, respectively, display strong ethnic and religious identities. They confirm the significance of cultural distinctiveness and sensory experience in the outsider’s construction of placeness. Distinct cultural symbols (e.g., temples, costumes) and multisensory stimuli (e.g., food, spices, languages) enable visitors to perceive neighborhood uniqueness and integrate direct and indirect experiences to form placeness. Therefore, these neighborhoods scored higher in the outsider-perspective evaluation.

Additionally, modernized urban areas such as Marina Bay, Sentosa Island, and the Orchard Road commercial district also ranked high from the outsider’s perspective.

Although globalized business districts share similar urban forms, such spaces evoke associations with comparable districts elsewhere, enriching the indirect experience of placeness. Marina Bay Gardens and Sentosa Island successfully integrate modern urban aesthetics with ecological spaces, demonstrating Singapore’s pursuit of a sustainable “garden city.” These landscapes concretize city branding and strengthen visitors’ understanding of Singapore’s identity.

Overall, the quantification of LDA-identified elements through the placeness indicators effectively captured the placeness value of Singapore’s neighborhoods. The results validate the operability of the framework as a computational approach for identifying neighborhoods suitable for city walk practices.

5.2. Route Design: The Chinatown Neighborhood Example

Based on ArcGIS network analysis, walking routes were designed within selected neighborhoods. Using Chinatown as an example, the optimized route is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

City walk route in Chinatown. The route begins near (1) the Singapore City Gallery and (2) Thian Hock Keng Temple, continuing through (3) Nam Cheong Grocery Store, (4) Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum, (5–6) Chinatown Food Street, (7) Sri Mariamman Temple, (8) Masjid Jamae (Chulia Mosque), and (9) Chinatown Heritage Centre, before ending near (10) the MRT station, providing convenient access to subsequent neighborhoods. Excluding visits to the City Gallery, the walking route covers approximately one hour. Landuse colors are the same as in Figure 1.

Starting at the City Gallery allows walkers to first gain an “outside-in” understanding of Singapore’s urban form and planning strategies across global, national, and local scales.

Subsequent movement “within” the streets then transforms this cognition into lived experience, supporting spatial and perceptual conversion.

The route highlights the multicultural landscape of Singapore. It passes three major religious sites: Thian Hock Keng Temple, reflecting Chinese Mazu worship; Sri Mariamman Temple, a Hindu temple built by Tamil immigrants; and Masjid Jamae, the oldest mosque in the neighborhood serving Muslim migrants. Although colonial-era racial segregation policies once separated communities, Chinatown’s strategic location encouraged multiethnic coexistence, resulting in a unique landscape of religious plurality.

Cultural blending is also reflected in everyday practices. The neighborhood retains traditional grocery stores supplying ritual goods for Chinese residents. The Chinatown Food Street features diverse cuisines from Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Peranakan traditions—the latter representing the hybrid culinary culture of Straits-born Chinese who intermarried with Malays, combining Chinese cooking techniques with rich local spices and ingredients.

This sensory diversity—visual, gustatory, and olfactory—enhances walkers’ sense of placeness.

Finally, the Chinatown Heritage Centre presents immersive exhibitions on early Chinese immigrants’ struggles and daily lives, contrasting strongly with earlier walking points and deepening walkers’ understanding of the neighborhood’s placeness and historical transformation.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

City walk, characterized by short-term and neighborhood-scale spatiotemporal activities, provides walkers with opportunities for spontaneous pauses and embodied observation, offering a new practical pathway to understanding urban placeness. How can we identify neighborhoods with high walking value that enable a rapid grasp of urban characteristics and a cognitive leap from the neighborhood to the city scale? This study integrates perspectives from humanistic and structuralist geography to construct a new placeness evaluation framework, providing a methodological solution to this question. Three main conclusions are drawn.

First, the “new synthesis” between humanistic and structuralist approaches reveals the dual logic underlying the formation of placeness, suggesting that these two theoretical perspectives are inherently interconnected rather than oppositional or mutually exclusive. On one hand, direct and indirect experiences play distinct roles in shaping placeness; on the other hand, global and local forces intertwine to jointly influence its formation. The text analysis results show that under the interaction between exogenous dynamics and endogenous experience, both local residents (self) and external visitors (other) participate in and shape urban placeness through different perceptual pathways.

Second, the placeness evaluation framework and indicator system based on the combined perspective of the self and the other include six dimensions: community development, public facilities, historical heritage, perceptual experience, urban landscape, and cultural characteristics. These dimensions reflect the connotative meanings of different spatialities in the “third space” theory, revealing the complexity of placeness and its dependence on multi-scalar spatiotemporal dynamics.

Third, this study identifies Singaporean neighborhoods with high potential for city walk experiences and takes Chinatown as an example to visualize walking routes using ArcGIS network analysis tools. This approach helps to overcome the limitations of existing tourism route design methods that overemphasize rational computation while neglecting local placeness. The proposed framework is simple, operable, and adaptable to practical application.

This study offers both theoretical and practical contributions but also invites further reflection on its broader implications and limitations. First, in relation to existing literature, the findings highlight the extent to which conventional tourism geography and urban walkability studies remain constrained by spatially deterministic assumptions. Prior research largely relies on GIS-based grid analysis and shortest-path algorithms to optimize intra-neighborhood walking routes, yet these approaches tend to overemphasize quantifiable attributes such as distance, accessibility, and service density. As noted in placeness scholarship, experiential, symbolic, and socio-cultural meanings are essential components of how individuals engage with urban spaces—a dimension traditional spatial models insufficiently address. Existing UGC-based studies improve the understanding of visitor preferences but often fail to reconcile visitors’ impressions with locals’ lived experiences, thereby producing partial or skewed representations of urban meaning-making. The present study responds to these gaps through an integrated framework that combines thematic extraction and placeness theory to identify walkable neighborhoods at the city scale.

Beyond these theoretical insights, the study also raises several practical considerations for urban governance. On one hand, the growing demand for personalized engagement with urban local characteristics calls for feasible and well-structured walking routes, which has become an important issue in urban planning and tourism development. On the other hand, city walk practices designed for educational field activities require higher quality and professionalization. A rational and convenient route design method can not only encourage student participation and enhance fieldwork skills but also deepen their understanding of urban placeness. Moreover, placeness profoundly influences how individuals perceive and interact with space, manifesting in both place attachment and shared public imagery [45]. Therefore, urban management authorities can apply the neighborhood selection and route design methods developed in this study to provide residents and visitors with more localized and meaningful walking experiences, thereby promoting city branding, cultural communication, and tourism development.

Singapore provides a compelling case due to its dense cultural landscape and hybridized global–local urban form. However, as a compact and highly managed city-state, it is not fully representative of other urban contexts. The present analysis therefore serves primarily as a demonstration of methodological feasibility rather than a universalizable model. Future research should validate and refine the framework through comparative studies across cities with varied spatial structures, including less compact, polycentric, or rapidly expanding metropolitan regions. In such settings, neighborhood boundaries, mobility patterns, and feasible walking radii may differ substantially. Adjustments—such as expanding the analytical scale, integrating cycling routes, or recalibrating network analysis parameters, may be necessary to ensure methodological applicability.

Finally, although UGC provides valuable insight into collective perceptions of place, it cannot fully capture the demographic composition, motivations, or affective depth of contributors. The transferability of the evaluation model may be limited in cities with sparse or uneven UGC data. Future work could incorporate mixed-methods approaches, such as surveys, ethnographic observation, or participatory mapping, to complement text-based evaluation and enhance robustness. Multi-regional comparison will also help identify the conditions under which the placeness evaluation model performs reliably, thereby advancing its generalizability and relevance for broader urban planning and design practice.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study. Conceptualization, investigation and original draft were performed by H.Z. and Y.W. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Y.W. Supervision, review and editing were performed by H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Teaching Team of Economic Geography at Faculty of Geographical Science, Beijing Normal University (2024-JXTD-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the My Community official website (https://mycommunity.org.sg/ accessed on 3 April 2024) and the Chinese online travel platform Ctrip (https://www.ctrip.com/ accessed on 3 April 2024).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT-4 for language polishing and consistency checking. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Virtual Teaching and Research Laboratory for Human Geography Practice at Beijing Normal University designated as a Pilot Unit for Virtual Teaching and Research Rooms in Beijing Higher Education Institutions (2023) and a Key Construction Project for Undergraduate Pro-grams in Human Geography and Urban-Rural Planning at Beijing Higher Education Institutions (2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Holton, W. Walking Tours for Teaching Urban History in Boston and Other Cities. OAH Mag. Hist. 1990, 5, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cao, C.; Ramachandran, S. A cognitive appraisal of the City Walk travel trend, considering city image, visitor engagement, place attachment, and behavioural intention. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.K.; Khaled, A.G. Towards a Socially Vibrant City: Exploring Urban Typologies and Morphologies of the Emerging “CityWalks” in Dubai. City Territ. Archit. 2023, 10, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Kaja, P.; Mojca, D. Walking the City—A Case Study on the Emancipatory Aspects of Walking. Sport Soc. 2023, 26, 1585–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Kaja, P.; Mojca, D. In Praise of Urban Walking: Towards Understanding of Walking as a Subversive Bodily Practice in Neoliberal Space. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2022, 57, 863–878. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, R.; Van Hecke, E.; Cabus, P. Delineating Tourism: Defining the Usual Environment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyere, A.S.; Frimpong, K.L.; Oviedo, D.; Mensah, S.L.; Fianoo, I.N.; Nieto-Combariza, M.J.; Abunyewah, M.; Adkins, A.; Kita, M. Policy–reality gaps in Africa’s walking cities: Contextualizing institutional perspectives and residents’ lived experiences in Accra. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 2381–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Jin, S. Walk Score and Neighborhood Walkability: A Case Study of Daegu, South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.K.Y. Casual Walking in Urban Tourism Destinations through the Lens of Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) and Hierarchy of Walking Needs Theories. Leis. Stud. 2025, 44, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Huang, A. Applications of Place Theory in Urban Leisure. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 28, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.; Hernández, B. Place Attachment: Conceptual and Empirical Questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T. Structuralist Geography: An Important School of Contemporary Western Human Geography. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yang, H.; Kong, X. Structuralist and Humanistic Analysis of the Formation Mechanism of Placeness: A Case Study of 798 and M50 Art Districts. Geogr. Res. 2011, 30, 1566–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, D.; Huang, P.; Xiong, G.; Li, H. Renewal strategies of industrial heritage based on placeness theory: The case of Guangzhou, China. Cities 2024, 155, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodier, J. The Dictionary of Human Geography (5th Edition). Ref. Rev. 2010, 24, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: Humanistic Geography Perspective. In Philosophy of Geography; Gale, S., Olssen, G., Eds.; D. Reidel Publishing Company: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979; pp. 387–388. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Xu, W.; Li, J. A humanistic geographical analysis of city space: A study of three maps in Beijing’s Context. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. “Place” in the Eyes of Humanistic Geographers. Tour. Trib. 2013, 28, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Segregated Worlds and Self: Group Life and Individual Consciousness; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Veronika, Z. ‘Where are you?’: (Auto)ethnography of elite passage and (non)-placeness at London Heathrow Airport. Mobilities 2023, 18, 936–951. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, M. Continuities and Discontinuities of Place. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. Meanings of Place: Everyday Experience and Theoretical Conceptualizations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The Condition of Postmodernity; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, A. What a Difference the Place Makes: The New Structuralism of Locality. Antipode 1987, 19, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ming, Q.; Han, J. An Analysis of the Dynamic Mechanism of Placeness Construction in Ethnic Tourism Villages from a Structuralist Perspective: A Case Study of Danohhei Village in Shilin. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 33, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Gu, C. Humanistic Geography: A Major School of Contemporary Western Human Geography. Geogr. Territ. Res. 2000, 16, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Third Space: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuolin, A.; Shangyi, Z. Trialectics of Spatiality: The Negotiation Process between Winter Swimmers and the Municipal Government of Beijing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oranratmanee, R.; Sachakul, V. The Use of Public Space for Walking Street Market in Thai Urban Cities. J. Mekong Soc. 2013, 8, 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Detecting Emotional Space of Urban Tourism Based on Street View Photos. Hum. Geogr. 2023, 38, 164–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. The World Cities; Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Feng, X.; Wu, W. A Study on the Perceived Image of Ancient Town Tourism Based on Text Mining: A Case Study of Zhujiajiao. Tour. Sci. 2013, 27, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wu, W.; Ma, N. Tourism Spatial Planning Methods Supported by GIS Grid Analysis: A Case Study of Qingdao City. J. Nat. Resour. 2018, 33, 813–827. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Application of Improved Dijkstra Algorithm in Coastal Tourism Route Planning. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 106, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Fan, B.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, B. Interactions among Trialectic Spaces and Their Driving Forces: A Case Study of the Xisi Historical and Cultural Block in Beijing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, C. Walking and Self-Healing: A Study of “City Walk” Phenomenon among Contemporary Youth from the Perspective of Geo-Psychology. China Youth Study 2024, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yuan, W.; Yuan, W.; Liu, F.; Li, H. Geopolitical Relations in the Arctic Based on News Big Data. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 1090–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Shugliashvili, T.; Pirveli, E. Unveiling news impact on exchange rates: A hybrid model using NLP and LDA techniques. Appl. Econ. Anal. 2025, 33, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, T.; Wang, F.; Wang, X. Urban Tourism Community Image Perception Based on Text Mining: A Case Study of Beijing. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1106–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhodair, S.A.; Fung, B.C.M.; Rahman, O.; Hung, P.C.K. Improving interpretations of topic modeling in microblogs. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 69, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Qi, Y. Selection of the Optimal Number of Topics for LDA Topic Model—Taking Patent Policy Analysis as an Example. Entropy 2021, 23, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalavong, P.; Im, H.N.; Choi, C.G. In What Ways Does Placeness Affect People’s Behavior? Focusing on Personal Place Attachment and Public Place Image as Connecting Parameter. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1394930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; Tang, G. Using Restaurant POI Data to Explore Regional Structure of Food Culture Based on Cuisine Preference. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Song, W. Identification and Geographic Distribution of Accommodation and Catering Centers. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).