Abstract

The article straddles the intersection of legislation, planning guidelines, and housing policy studies in the neoliberal era. Its objective is to examine the right to a home within urban renewal projects. It addresses the gap between residents’ experience of housing as “home” and private developers’ view of housing as strictly an investment. This raises the question: how do laws, planning guidelines, and scholarly studies reflect the meaning of home? This question is examined through the Israeli case study. The method is parallel and interpretive content analysis of laws, guidelines, and research spanning more than a decade. The results indicate that in response to rapid population growth, urban renewal in Israel relies heavily on demolition and rebuilding. Low-rise buildings accommodating mainly disadvantaged populations are replaced by high-rises, to which these populations are expected to return. The conclusion is that the neoliberal perspective dominates the discourse. Despite the financial and human costs associated with high-rise living, the relevant literature pays insufficient attention to the loss of the right to a home. Accordingly, financial compensation for disadvantaged populations is recommended by legislation and research, along with limiting residents’ responsibility to their apartment as a planning solution for the eroded right to a home.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Right to a Home

Home is integral to emotional life. A large and steadily growing body of literature has examined people’s emotional relationships with their domestic environment. For the purpose of this study, it is assumed that home serves as a central locus for feelings of comfort, belonging, and security [1]. It is further assumed that the neighborhood and community serve as emotionally significant extensions of home [2].

The close association of home and its residents leads to the notion that improving the home and the neighborhood may also enhance residents’ quality of life and well-being. Poor housing quality correlates with diminished self-esteem and reduced willingness or capacity for social interaction [3]. Conversely, improvements in the home environment are associated with lower levels of depression and with reductions in harmful behaviors such as alcohol and drug use [2].

Undermining the right to a home—even when accompanied by housing improvements—often leads to anxiety, stress, and depression [4]. Displacement from the neighborhood, which involves removal from both the physical environment and the community’s social networks, can be traumatic [5]. Studies have shown that displaced residents cannot easily reestablish their spatial and community relationships in unfamiliar neighborhoods [6]. Moreover, housing improvements may also have unintended mental health consequences due to pressures associated with rising living costs (such as rent, maintenance fees, municipal taxes, and commuting to previous workplaces) and the destruction of social networks. A study with 4657 participants in Glasgow revealed a link between residents’ subjective assessments of their health and their perception of home and sense of control within it, concluding that when the right to a home is not undermined, health outcomes improve [2].

1.2. The Right to a Home in the Neoliberal Era

The right to a home in the Western democratic world has been increasingly undermined in recent years due to the adoption of neoliberal approaches [1]. Neoliberalism endorses self-realization free of bureaucracy: individuals are held responsible for their own self-interested choices, which are assumed to promote their personal well-being [7]. As an economic doctrine, neoliberalism emerged in the late 1970s and was designed to reorganize global capitalism and the conditions for capital accumulation [8]. The economic competition central to extends beyond national borders [9]. As a result, economic policy relies less and less on elected governments and increasingly on the interests of multinational corporations. The aim of policy is to facilitate the unrestricted operation of “the market”. This has led, among other things, to the enforcement of low wages and precarious working conditions, restrictions on both tenants’ and workers’ rights, and the privatization of public monopolies over urban services such as sanitation and mass transit. At the same time, public lands and open spaces are also privatized. Consequently, the use of infrastructures has become more costly, with parts of them remaining out of the reach of disadvantaged populations [10].

A caveat is necessary here: despite the definition adopted in this article, scholarly views on neoliberalism and its outcomes are far from unanimous. Some argue that not everything that appears neoliberal is necessarily so. In certain cases, what may seem neoliberal is merely cost-reduction or efficiency for its own sake—measures that could also be compatible with liberal economic thinking [11]. Pinson and Morel Journel (2016) [12] outline different interpretations of neoliberalism across disciplinary fields: intellectual history, anthropology, Foucauldian approaches, and neo-Marxist class-based perspectives. According to their argument, only the fifth school of thought, influenced by Harvey (2005) [8], provides the most systematic analysis of the relationship between neoliberalism and urban environments.

With respect to the right to housing, the state has been gradually retreating from its historical responsibility to provide fair housing for its citizens, as was the case in Europe after World War II [13]. Instead, national and local authorities have transferred power to commercial actors [14]. In the absence of a strong public body to regulate some form of “spatial justice”, the city becomes a patchwork that deepens disparities between different areas: attractive neighborhoods become even more attractive, while poor neighborhoods suffer under austerity measures [10].

Homeownership rates in most Western capitalist countries have dropped dramatically in recent decades, as purchasing a home has increasingly escaped the reach of even higher-income groups [15]. Concurrently, home has shifted from being considered a basic human right [16] to a financial commodity [1]. Housing has become just another asset on the market [17]. Consequently, as states and municipalities withdraw from their responsibility to provide fair housing, the profit of private developers becomes the central focus, often to the detriment of residents [18].

1.3. Undermining the Right to a Home in Urban Renewal Projects

In light of the discussion above, it is evident that contemporary urban renewal is also a product of neoliberalism [14], since it is driven by entrepreneurial profit (and facilitated by the state and municipality). The conversion of former industrial sites into apartments, the proliferation of high-rise buildings and shopping malls, and even public spaces adorned with branded restaurants are all designed to present a new urban image through which the city can attract investors, affluent residents, and tourists [19].

Conversely, declining urban areas and disadvantaged populations are deemed undesirable. Urban renewal that excludes these populations through gentrification becomes inevitable, and indeed, such processes have spread widely in recent years [20]. Weber (2002) [21] argues that the neoliberal alibi for clearing and demolishing poor neighborhoods is the rhetoric of “obsolescence”. Once framed in this way, there is no longer any need to demonstrate that the buildings being renovated or demolished fail to serve their residents—the process is depicted as “natural”, unavoidable, and irreversible.

The first victims are residents of public housing. Their dwellings are transferred to private developers, who then demand renovation costs [17], which may amount to 30–60% of the former rent [7]. Those unable to meet such payments are excluded from both public housing and their neighborhoods, thereby losing their right to a home. In the next stage, it is the same disadvantaged groups that fail to secure affordable housing.

Consequently, low-income populations lose power and control over their home, which renders them marginalized and forces them out [22]. Relocation to a cheaper neighborhood often entails changing workplaces, giving up proximity to urban centers near the older neighborhoods located in city cores, and transferring children to new schools. The latter are directly affected by their parents’ housing insecurity and often suffer deterioration [23]. Note that the rising cost of housing (and living in general) affects not only disadvantaged populations but also young people, students, artists, and other middle-class groups, who can no longer afford to live in the neoliberal city [24].

By now, housing instability, benefiting the wealthy elites, has become normalized [1]. Over several decades, the embedding of neoliberal ideology has intertwined public and private strategies with national and local policies actively promoting gentrification and the deliberate displacement of marginalized populations. Left, right and center, potential political opponents are now aligning with the new metropolitan mainstream [7]. On the surface, these processes appear to be driven purely by economic considerations; yet the discourse often fails to acknowledge the sense of home, its loss, and their profound implications for human identity. This silencing of the human toll of urban renewal is also reflected in the research literature: whereas the destruction of homes in war is well-researched, the everyday mechanisms through which homes are dismantled for entrepreneurial profit receive little scholarly attention [1].

1.4. The Current Study

The present article is situated at the intersection of planning legislation, planning guidelines, and research on housing policy in the neoliberal era, which constitutes its contribution to the discourse. The article deepens the discussion of the right to a home for disadvantaged populations in Western democracies. Whereas housing serves clearly as a “home” for residents, developers view it narrowly as a financial instrument. The research question is therefore: which view predominates in documents produced by the other actors involved in the urban renewal process, able to set limits on market power? To address this question, this article examines the content of legislative documents, government planning guidelines, and research studies regarding urban renewal projects.

In the Israeli case under study, renewal projects are based primarily on the demolition of old buildings in favor of new high-rise developments. They are particularly relevant to this research since as early as the 1960s, international studies found that disadvantaged residents in new high-risers could not afford the maintenance of extensive shared spaces and infrastructures such as elevators, water pumps, fire sprinklers, and parking facilities. As a result, the buildings physically deteriorated [25].

Ultimately, the high-rise buildings intended to replace aging neighborhoods ended up producing vertical slums. The iconic image of the demolition of several high-rise buildings in the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis in 1972 cemented the perception that low-income populations lacked the organizational and financial wherewithal to maintain such housing [26]. To this day, urban renewal projects that resettle disadvantaged populations in high-rises carry a well-documented potential for decline, crime and vandalism [27], excluding these populations from their right to a home by detaching them from their surroundings.

The right to home for disadvantaged populations in high-rise buildings is examined below from three perspectives. The first is the perspective of the law, which may be expected to restrain the market. The second is that of planning guidelines by professional architects employed by the Ministry of Housing, whose mandate is to protect disadvantaged groups. Finally, the third perspective is that of urban renewal research. The article examines whether those actors have also embraced neoliberalism or retain a distinct voice that keeps the to right a home in clear focus.

The decision to analyze the content of public—some of them official—documents, rather than investigate the positions of their creators through ethnographic research, stemmed from the following reasons. With regard to legislation, lawmakers and legal advisors are not credited; their identities remain anonymous and therefore cannot be known. With regard to planners, most of them were never required to engage directly with disadvantaged populations, and most of the planning guidelines were not designed to deal with such populations. Extracting information from these spatial guidelines makes it possible to understand what the approach toward these populations is, without the statements being explicitly made or even consciously formulated by the authors. As for researchers, their perspectives can be inferred directly from the content of their studies, and therefore direct interviews are unlikely to offer substantial added value.

The article proceeds as follows. Following Section 2, which identifies the case study and the content analysis approach, Section 3 analyzes Israeli legislation on the subject (Section 3.1), planning guidelines prepared by the Ministry of Housing (Section 3.2), and local research addressing disadvantaged populations in urban renewal projects (Section 3.3). Section 4 compares the local results to developments in Western democracies and frames them within broader discourses, with subsections parallel to the previous section. It highlights the article’s contribution at the intersection of planning legislation, planning guidelines, and research on housing policy in the neoliberal era. Section 5 proposes alternative courses of action.

2. Materials and Methods

Israel is used as a case study because it embodies neoliberalization processes while simultaneously challenging them through the managerial and architectural manner in which urban renewal is carried out. First, for historical reasons related to the origins of the country’s elite [28], Israel perceives itself as a Western state. Its planning ideologies align with Western ideologies, and its planning practice mirrors developments in democratic countries [29]. The same applies to the Israeli transition from socialism to neoliberalism with regard to construction practices [30].

Second, like Western countries, Israel was founded with a centralized interventionist planning apparatus designed to achieve national and metropolitan population dispersal [31]. At the same time, the state sought to provide modern and affordable housing for disadvantaged populations, much like West European countries after World War II [16]. In Israel, this meant Jewish immigrants who tripled the country’s original population within a decade after gaining independence in 1948 [32]. Motivated by concern for these disadvantaged groups, the Ministry of Housing directly built new towns, neighborhoods, and residential buildings in areas lacking private initiative during the first three decades of statehood. Subsequently, even when the ministry built less directly or worked through private developers, it still regarded itself as responsible for these populations. This concern was expressed through initiating and supervising planning schemes for new towns and neighborhoods and producing planning guidelines informed thereby [30]. Thus, examining the views of planners working for the ministry is particularly relevant.

Third, population growth and the ecological aspiration to preserve open spaces have encouraged compact urban planning [33], including urban renewal based on demolition and reconstruction. In 2013, the government declared renewal a “national necessity” and set specific targets for the number of housing units it would provide [34]. In 2025, the National Urban Renewal Authority envisioned that by 2030, 35% of newly added housing units would be located within already built-up areas [35]. The authority’s report further stated that “urban renewal processes focus on improving conditions for the existing population and on restoring a diverse and multi-generational population to city centers and older neighborhoods” [35] (p. 12).

Accordingly, high-demand low-rise buildings in inner-city areas—typically inhabited by disadvantaged populations in affordable housing—are demolished and replaced by new construction to accommodate both the original residents and a socioeconomically stronger population. Thanks to the influx of this new population, the neighborhood is expected to undergo physical, symbolic, and social renewal.

According to capitalist or neoliberal practices, as described by Storper (2016) [11], or by Mayer [10], private developers carry out most demolition-and-reconstruction projects. They are responsible also for providing temporary housing for the original residents during the interim period. To offset the significant costs and maximize profits, developers build more housing units on the site, typically in the form of high-rise buildings. The lower the land value, the denser and taller the planned development. Conversely, in high-demand areas, the new construction is somewhat lower, with the original housing stock multiplied “only” two- or threefold [36]. The spatial outcome is thus often paradoxical: plans dominated by high-rise buildings, disconnected from their surroundings and from housing demand in peripheral cities or neighborhoods, versus lower-rise developments in central, high-demand areas. This makes the Israeli case particularly relevant for examining the right to housing in urban renewal projects. These high-rise buildings, also intended for the original disadvantaged population, pose a significant challenge to their ability to continue residing in the area (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

On the edge of a high-demand area in central Israel, Neve Monson neighborhood is undergoing demolition and reconstruction. High-rise buildings (four times the height of the original houses) replace the low-rise structures (left), which are slated for demolition. Most of the latter are home to disadvantaged populations. Photograph: Author.

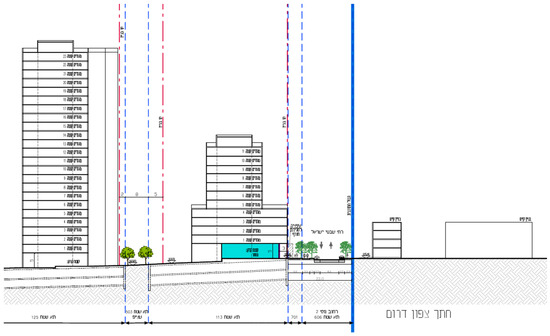

Figure 2.

Partial architectural section (in the north–south direction) of an urban renewal plan in Kiryat Gat, a city located outside Israel’s central high-demand areas. Next to the original three-story buildings on the right, one can see the new buildings being erected, reaching heights of 11 and 23 stories (approximately seven to eight times taller). Design: Yoav Hashimshoni, D.S. Urban Design Architects and Planning Ltd., Tel Aviv, Israel [37].

Figure 3.

Visualization of the urban renewal project in Kiryat Gat, as shown in Figure 2, designed by Yoav Hashimshoni, D.S. Urban Design Architects and Planning Ltd., 2019, Tel Aviv, Israel [38].

This qualitative study relied on a parallel content analysis of documents from three fields of knowledge. Regarding legislation, it identified laws related to urban renewal processes based on demolition and reconstruction, as well as legislation aimed at supporting disadvantaged populations in those projects. The legislation examined spanned the years 2006–2023.

In addition, I examined planning guidelines published by the Israeli Ministry of Housing as it is the only authority that explicitly prioritizes the spatial needs of disadvantaged populations. Guidelines addressing the design of buildings and neighborhoods were selected, since no guidelines were written for areas undergoing renewal based on demolition and reconstruction. Note that unlike other Western countries, Israel still constructs new cities and neighborhoods on state-owned land [39]. The planning guidelines allow insight into the ministry’s approach to neighborhood spaces and preferred buildings and help understand the planners’ perspective toward disadvantaged populations. The guidelines analyzed here were published from 2005–2017.

Finally, studies were examined that focus on high-rise housing and the situation of disadvantaged populations following demolition and reconstruction projects. These studies were written between 2001 and 2022. Initially, urban renewal through demolition and reconstruction of an entire complex was still theoretical, and the studies addressed high-rise construction in general. From 2019 onward, it became possible to examine the immediate outcomes of such projects.

The study is theoretical, interpretive, and qualitative. It provides a parallel content analysis of legislation, government planning guidelines, and research. Although it examines documents over a 12–21-year period, it is not a genealogical study requiring a longer timeframe, as the process in question is still in its early stages. Thus, it can form the basis for future research.

3. Results

3.1. Legislation

Israeli legislation promoting demolition-and-reconstruction projects is two-pronged. On the one hand, in 2006 the state determined that such projects could move forward even with the agreement of only 80% of residents [40]. In 2023, the law was amended to allow a two-thirds majority of residents to impose such a project. According to the legislator, the will of the majority outweighs the personal interest of an individual resident who refuses the project [41].

On the other hand, the state has taken measures to ease the burden on disadvantaged populations. With the enactment of the Urban Renewal Authority Law in 2016, the status of public housing tenants was formally recognized. Unlike private market renters, who received no legal protection, public tenants were granted rights. The law stipulated that tenants could choose between renting an apartment in the newly built complex and receiving an alternative public housing unit. In addition, the law capped rental payments for public housing tenants in their new apartments, as well as the building’s management fees [34].

The refusal of older individuals to participate in projects was deemed reasonable. Projects take years to complete, and many elderly residents would not live to enjoy their new apartments. Moreover, many face physical and cognitive difficulties in adapting to a new environment. Consequently, in 2018, the law was amended to broaden compensation options for elderly residents. These included: (1) relocation to assisted living and compensation equivalent to the value of the new property; (2) the purchase of a comparable apartment near the original one; (3) a cash payment for the original property; (4) the purchase of two smaller apartments instead of one, or of a smaller apartment plus compensation equal to the value of the new property [34].

The Urban Renewal Law also addressed the needs of disadvantaged homeowners wishing to return to the renewed neighborhood. To help them meet the higher maintenance fees, the law granted a five-year discount on municipal property taxes for the additional floor area added to their apartments [34].

In summary, while the state allows two-thirds of residents to impose demolition-and-reconstruction projects on the remaining third, it provides protections for public housing tenants and eases the transition for elderly residents. With regard to disadvantaged homeowners, however, the state offers only partial compensation, and private-market renters receive no protection at all.

3.2. Planning Guidelines of the Ministry of Housing

The planning guidelines of the Ministry of Housing were authored by professional architects working in the private sector who were also engaged in government projects. These guidelines were not issued as binding regulations but rather as a structured tool for planners regardless of the commissioning body—whether the ministry or private developers. Beyond specific recommendations, the guidelines represent a broader planning-ideological orientation. They articulate what planners within the ministry regard as the optimal urban environment, aligned with Western planning conventions. As mentioned in the previous section, these guidelines pertain to new construction, as no guidelines have yet been established for urban renewal projects involving demolition and reconstruction.

Accordingly, the guidelines advocate for compact development, high accessibility and connectivity, mixed land uses, and human interaction among diverse populations [30]. In this respect, they do not differ from parallel conceptions of “good urbanism” in Western Europe [42,43]. With regard to neighborhood design, the Ministry of Housing maintains that a sustainable neighborhood is one that retains its value over time: it does not deteriorate, is not abandoned, and is not expected to undergo massive demolition and reconstruction [30]. Whereas the ministry’s guidelines make no specific reference to planning high-rise neighborhoods for diverse populations, several guidelines analyzed below provide insights into its position on that matter.

The “Neighborhood 360” guideline provides a scoring method for evaluating neighborhood sustainability, based on indicators developed in Australia and the UK. Its underlying premise is that the more diverse a neighborhood is the more sustainable it becomes [44]. In the optimal neighborhood, the main routes are designed as streets that accommodate diverse forms of mobility, provide access to residences, and support mixed uses [45]. Along these streets, commercial services and public facilities should be built [46], either independent, connected, or integrated with housing [47]. Implicitly, the optimal neighborhood should be adapted to different populations, and therefore be diverse in its housing, paths and uses. Access to buildings and services should be visible and open to all, and thus they need to be located along the edge of a public resource such as a street.

Other relevant guidelines recommend studying the type of population and locality prior to adopting specific planning instructions. These include a planning guideline for allocating land for public purposes [48], and a guideline for planning open spaces [49]. The characteristics of the relevant population are defined according to general human needs, such as visibility and accessibility, as well as demographic variables such as age, socioeconomic status, and cultural practices. With respect to disadvantaged populations, the authors rely on the above-mentioned lessons of the past and acknowledge their difficulties in maintaining extensive shared spaces over time.

In light of these insights, two guidelines address housing more specifically. The first recommends that plots designated for neighborhood development be relatively small. A small plot ensures that the shared spaces of the building erected upon it remain limited, and therefore affordable by disadvantaged populations. Specifically, direct access to the plot from a continuous street would reduce friction among neighbors and minimize shared spaces that might otherwise become neglected [50]. The second guideline recommends that apart from a shared garden connected to the building’s entrance, any remaining open land should be allocated to the ground-floor apartments. In addition, residential buildings are to be of high construction and finishing quality, and to include a minimum of shared systems, so as to prevent deterioration of the building and its infrastructure in the absence of organized tenant associations to finance maintenance [51]. The conclusion of these two guidelines is an explicit rejection of high-rise construction. Low-rise buildings with a larger footprint are preferred to a single tall building; multiple stairwells are favored over one large shared stairwell; and several entryways are preferred to a single entrance serving all residents.

In summary, the guidelines identify the neighborhood as the fundamental planning unit and assume that a good neighborhood is diverse. In practice, the reliance on street-oriented, low-rise, high-coverage construction with small plots, along with minimized shared spaces, is informed by the understanding that disadvantaged populations are unable to organize or otherwise finance the maintenance of high-rise housing. Hitherto, no guideline has attempted to develop spatial models that would allow disadvantaged groups to live sustainably in high-rise environments.

3.3. Research

High-rise housing began attracting scholarly attention in Israel in the early 2000s, reflecting a correct reading of densification trends and public preferences. A study on the impacts of high-rise construction noted: “A city of towers, which only a generation ago was uniquely American, will gradually spread and become the dominant urban landscape of the coming decades in many cities” [52] (p. 1). At the same time, the public was drawn to the prestigious image of residential high-rise buildings, which replaced the earlier aspiration for a detached private home. The pursuit of individual distinction led residents to regard high-rise buildings—with their grand lobbies, parking spaces, oversized apartments, and open vistas —as symbols of success and self-fulfillment.

The desired tranquility of tower residents in their immediate surroundings precluded mixed uses—in contrast to the planning guidelines reviewed earlier. Complexes of high-rise residential buildings around or within undefined open spaces came to characterize private construction. These sought-after complexes were intended from the outset for middle- and upper-middle-class populations [30] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Ir Yamim neighborhood in Netanya: a model of a luxury high-rise neighborhood designed exclusively for affluent populations. Photograph: Author.

The studies have replicated earlier findings that high-rise living was unsuitable for low-income families [25,26]. The researchers argued that high-rise housing was also inappropriate for young children, given their need for outdoor play, while being more suitable for older adults and single individuals in comfortable economic circumstances [52]. As for urban renewal, research suggested that most young people—who contribute to the vibrancy sought by renewal projects—were not natural candidates for this type of urban renewal. Furthermore, the unique character of traditional urban centers could be undermined by the addition of contemporary high-rise construction, leading to a loss of distinctive identity and sense of place: tower cities tend to resemble one another [53].

Despite the studies noted above, high-rise construction has increasingly become a solution both for new urban neighborhoods seeking socioeconomically strong populations and for urban renewal projects. The professional terminology has shifted accordingly: buildings that until recently were considered “high-rise” in Israel (10 stories) are now classified as “mid-rise”. High-rise construction is currently defined as 14 stories or more, though in practice buildings of 16 stories and above are being built [54].

Consequently, demolition-and-reconstruction urban renewal projects implemented in several complexes in central Israel have generated new research focusing on the integration of long-standing residents. At the neighborhood level, studies point to the displacement of residents as a result of gentrification. Renters find themselves compelled to leave due to rising rents, elderly residents pass away during the lengthy course of projects, and disadvantaged homeowners are often unable to afford the increased maintenance cost [55]. Theoretically, owners have several residential options in demolition-and-reconstruction projects. If they are wealthy (and likely have rented out their apartments prior to renewal), they may choose to reside in the renewed neighborhood, to sell, or to rent out the property. If they are disadvantaged, they may choose to sell or rent out the property, or to return to live in the renewed neighborhood at the cost of reduced disposable income. In all options—except for returning to the neighborhood—a socioeconomically stronger population enters the neighborhood, while disadvantaged residents are displaced [56].

Kainer-Persov (2019) studied the first demolition-and-reconstruction project in Israel, in the Tel Aviv suburb of Kiryat Ono (completed in 2014). She found that only 40% of residents in the demolished complex returned to live in it, constituting just 13% of the population at the time of study, with high maintenance costs threatening their continued residence [57]. Geva and Rosen (2019) studied six complexes in central Israel that underwent demolition and reconstruction, and found that half of the apartment owners returned, making up 14% of the total residents [58]. Similarly, Brodkin and Mualem (2022) examined a complex in high-demand Tel Aviv and found that about half of the apartment owners returned, representing 11% of the total residents [59]. Thus, when at most 50% of the original residents return immediately after renewal, the other half of long-standing residents lose affordable housing.

With regard to high-rise buildings specifically, many scholars have reiterated the problem of organization and financing among disadvantaged populations, who are required to cover the high costs of maintenance [60,61,62]. They argue that such challenges may lead to the physical deterioration of buildings or to the displacement of long-standing residents who cannot afford the payments.

Regarding social issues, Kainer-Persov (2019) argued that returning residents expressed nostalgia for the warm neighborly relations of the old housing project, which were absent in the new one [57]. Geva and Rosen (2019) [58] examined the social outcomes in six such projects in the Tel Aviv metropolitan area and found variations in the relationships between long-term and new residents, as well as in the displacement of the former. These depended on the socioeconomic gaps between the old and new populations and between the neighborhood and its surrounding areas. The greater these gaps, the more intense the social conflicts and the lower the levels of satisfaction.

From a planning perspective, only Padan (2014) [63] proposed a design-oriented solution specifically tailored to high-rise buildings for disadvantaged populations. She did so by introducing the concept of accessory dwelling unit (ADU). This concept envisions flexible apartment layouts that can be divided into two units—a smaller unit intended for rental and one larger one for the family’s residence (or vice versa, in the case of a single tenant). Rental income would enable disadvantaged households in high-rise buildings to cover high maintenance costs and remain in the neighborhood [60].

Interestingly, studies from around the 2020s assessing the benefits of demolition-and-reconstruction projects for disadvantaged populations have shifted in tone. According to these studies, residents emerge as beneficiaries: the value of their new apartments increases significantly without their own investment; their socioeconomic status is enhanced; and they gain both financial security for the future and inheritance to pass on to their children [55,57,64].

In summary, although scholars are aware of the displacement of disadvantaged populations from urban renewal projects, especially those involving high-rise housing, these projects are also framed as offering financial advantages. Apparently, all parties profit: the state and the municipality gain tax revenues generated by the appreciation of land value and the increase in allowable building density; the city is renewed and better aligns with the environmental demands of the sustainability era; developers profit financially; homeowners benefit from property value gains; and disadvantaged residents receive at least some legal protections.

4. Discussion

The results reveal that legal, planning, and academic approaches to the right to a home for disadvantaged populations are inadequate. This is despite the fact that the state actively promotes demolition-and-reconstruction urban renewal projects, in which disadvantaged groups are expected to live in high-rise buildings whose maintenance costs exceed their financial capacity [25].

4.1. Legislation

A review of Israeli legislation shows that lawmakers are aware of the financial difficulties disadvantaged populations face when living in high-rise buildings. Nevertheless, compensation is primarily financial and highly partial (such as a small property tax reduction for a limited number of years). There is no recognition of the right to a home and to a familiar environment, which constitutes an extension of the home itself. The implicit assumption is neoliberal: disadvantaged populations must cope with their hardships independently.

According to Israeli law, the interest of the majority prevails over the opposition of the individual: two-thirds of residents can impose their will on the remaining third in demolition-and-reconstruction projects. However, not only the interests of residents that are accounted for, but also those of the private developers, the municipalities and the state, which benefit from tax revenues.

Examined against parallel developments in the Western world, the present results can be interpreted historically, using the economics of convention approach. This approach highlights the consolidation of a culture based on individualism and personal interest, in which the individual is alone and responsible for their fate. Within the same context of cultural change, one can also observe the process that began in the 1970s, whereby the state property rights system incentivized individuals to innovate and produce. Naturally, these incentives primarily benefited private developers [65].

The institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework also provides a theoretical lens for interpreting these processes. This framework emphasizes that there is a normative and socially accepted basis for the incentives linking public and private interests. These interests, it is noted, are not solely financial [66]. The displacement of disadvantaged populations from areas undergoing demolition-and-reconstruction-based renewal may in fact serve the municipality. The presence of disadvantaged populations is perceived to undermine the urban image and attractiveness, and if they are welfare-dependent, they also constitute an economic burden.

Le Galès and Vitale (2013) [67], and later, Findeisen and Le Galès (2025) [68], examined the relationship between the multiplicity of interests, policy tools, and metropolitan areas. While the former argued that the boundaries of contemporary metropolises are constantly shifting and chaotic in terms of governance, culture, and unequal control structures [67], the latter focused on the gap between metropolises and peripheries. they asserted that the decentralization of housing policy empowered local authorities. As a result, economically prosperous areas were able to engage additional actors to implement their housing policies (not necessarily the state’s policies) by relying on the private market. In contrast, economically disadvantaged areas deteriorated. From a policy-tool perspective, Findeisen and Le Galès concluded that the multiplicity of policy instruments had exacerbated territorial inequality [68].

Thus, the implementation of legislation favoring developer interests amplifies the municipal gap between high-demand and marginal areas, as well as the national gap between center and periphery. The state is no longer the “responsible adult” moderating disparities and curbing the excesses of the private market or supporting institutions that promote community equity [69]. Instead, it is the “adult” who encourages competition and inequality.

4.2. Planning Guidelines of the Ministry of Housing

An analysis of planning guidelines intended for new construction reveals that planners rely on past and current studies indicating that disadvantaged populations are unable to organize or fund the maintenance of shared spaces independently. The Israeli experience supports this: large communal areas adjacent to collectively owned apartment buildings have suffered from neglect [30]. The conclusion of the guidelines, therefore, is that shared spaces should not be allocated to disadvantaged populations from the outset. Since high-rise housing inherently contains numerous and costly shared spaces—such as parking lots, elevators, automated water systems, and fire safety systems—it is categorically unsuitable for these groups.

In practice, high-rise buildings intended for disadvantaged populations are constructed following urban renewal projects neglected in planning guidelines. This constitutes a significant blind spot. No planning guidelines have been developed with the interests of these populations in mind, suggesting solutions such as dividing the high-rise building into subcomplexes. There is also no development of apartment-level design solutions that would allow disadvantaged populations to live in high-rise housing; for example, apartment layouts enabling subdivision and rental. Nor is there any theoretical framework that challenges neoliberal values or asserts that public authorities should help maintain private shared spaces.

The interpretation of the results aligns with the entrenchment of a culture based on individualism [65]. Reigner (2016) [70] argues that neoliberal rationality subordinates every aspect of social life to economic calculations. Within this framework, citizens are understood as individual clients or entrepreneurs responsible for their living conditions. This explains why planners seek to minimize the spatial responsibilities of disadvantaged residents from the outset. Since these residents are deemed incapable of taking responsibility, it is preferable that their spaces be as limited as possible.

Reigner demonstrates that, under the guise of “rationality”, individuals are encouraged to align their behavior with the interests of capital owners. She argues that the “noble” goals and morality serve as a democratic sedative that neutralizes opposition [70]. The Israeli experience similarly shows that even under the value-laden heading of a “sustainable neighborhood”, the implicit assumption persists that high-rise construction is unsuitable for disadvantaged populations. In practice, given the state’s increasing densification and the vertical expansion of desirable urban areas, there is no room for the disadvantaged in sought-after metropolitan locations.

4.3. Research

A review of Israeli research reveals a multilayered trajectory. Initially, scholars criticized high-rise housing as unsuitable for all populations. Subsequently, the focus shifted to weighing the costs and benefits for disadvantaged groups following demolition-and-reconstruction projects: economic gains versus social or emotional losses. Around the 2020s, a change in tone became evident. Israeli researchers, well aware of the dynamics of gentrification, increasingly emphasized the economic benefits of urban renewal. They began to argue that disadvantaged residents acquired a highly valuable asset at no personal cost, enabling them to bequeath it to their children.

How can these results be explained? First, they reflect a recurring and traditional recognition of the positive relationship between adequate housing, self-image, and personal well-being [2,3]. Second, they reflect the association between homeownership and welfare. Israeli researchers are not unique in this respect. The literature often distinguishes dichotomously between homeownership (linked to stability, capital accumulation, wealth accumulation, and distribution) and renting (linked to instability, lack of capital, and absence of wealth accumulation). Since the rise of neoliberalism in the 2000s, housing has been perceived as an asset providing a safety net, rather than relying on eroding state mechanisms. Consequently, homeownership has become—both materially and ideologically—critical to household economic security and welfare, particularly in the absence of rent regulation [71].

However, Zhang (2023) [71] notes that overburdening households with expenses can create homeowners who are no more secure than renters. Since the 2008 financial crisis, homeownership rates in Western countries have declined. According to Zhang, individuals entering the housing market after 2000 without sufficient means tend to fall into debt and worsen their standard of living. In other words, homeownership alone is not a criterion for welfare support; the critical factor is the ability to maintain one’s residence.

In sum, disadvantaged populations cannot live in high-rise buildings in a manner that ensures well-being, as their income is insufficient. Israeli researchers are aware of this. Nevertheless, in recent studies, they have shifted their tone, emphasizing economic gain over personal welfare. Their perspective therefore adopts a neoliberal value system, in which an individual is measured primarily by the capital they own.

5. Conclusions

Lovering (2007) [19] argues that the adoption of neoliberal assumptions by governments and their agents, particularly at the urban scale, is not a rational and definitely not inevitable adjustment to a new historical reality. Rather, it is an ideological shift that is both local and global. Based on the Israeli urban renewal case study, the current results reinforce that conclusion. The neoliberal paradigm that places its trust exclusively in the private market remains largely unchallenged. There are hardly any fresh, alternative voices calling for the protection of the right to a home in an increasingly higher and unaffordable city.

Even COVID-19 failed to dent this prevailing approach. At first glance, the pandemic seemed to restore power to the state, as governments imposed lockdowns and led mass vaccination campaigns. It also exposed neoliberalism’s failures: global connectivity accelerated the spread of the virus [72]; inequalities in healthcare became evident [73]; and the poor were disproportionately infected, while their small apartments prevented adequate home isolation [74]. Expected to generate deeper criticism of neoliberalism [75], these dynamics proved transitory: as the pandemic subsided, so did the criticism. Lockdowns were eased to restart the economy and avoid recession [76], and housing rights protests that had briefly emerged subsided [77]. What remained was the recognition that spacious housing was preferable to small, overcrowded apartments as it enabled prevention of infection and working from home. This may explain the shift in Israeli scholars’ positions, who, particularly after 2020, increasingly examined urban renewal through a neoliberal lens and saw only benefits in new and more spacious apartments.

Nevertheless, there are solutions. Appropriate policy tools have been tested in the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, and Austria. Jepma et al. (2025) [78] found that in a hundred shared-housing initiatives in these countries, sustainable responses to the affordable housing crisis in neoliberal cities can be achieved. Shared ownership, cooperative and democratic management of residents and common facilities form part of the solutions designed to make housing more affordable. Barenstein et al. (2022) [79] found that housing cooperatives could also provide an effective solution. In cooperatives, rent covers only costs, without entrepreneurial profit, thus providing municipalities and the state with a mechanism to preserve the right to home for disadvantaged populations. The relationship with the municipality and government is essential to this solution: the land is city-owned and leased for decades, and the state assists through loans and favorable mortgages. Some units are designated for housing subsidized by the municipality.

Where such policies do not exist, resistance is also possible, as documented in the research literature. Disadvantaged tenants in Sweden, most of them immigrants, collaborated with local academics to resist large housing companies that had drastically raised rents under the pretext of public housing renovations [17]. In Dublin, the dispossession of marginalized populations in the name of urban renewal led to community activism, including the presentation of alternative development plans and the publication of critical research exposing the true agendas of both the developers and authorities [14].

In this spirit, the present article calls upon legislators, policymakers, planners and researchers stop identifying “home” as merely an economic asset, reintroduce the notion of the right to a home into discourse and policy, and offer practical solutions to promote it. First and foremost, it is necessary to initiate a shift in discourse and reach broad consensus that change is required. As Vitale (2010) writes, “Change in urban policy is only possible where the situation and the common feeling with respect to the situation, rules, and preferences are successfully turned around” [66] (p. 43).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this article (legislation, planning guidelines, and research studies) are publicly available and are detailed in the article’s reference list.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Igal Charney for his wise advice to examine the concept of home in relation to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nowicki, M. Bringing Home the Housing Crisis: Politics, Precarity and Domicide in Austerity London; Policy Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.; Kearns, A. Housing improvements, perceived housing quality and psychosocial benefits from the home. Hous. Stud. 2012, 27, 915–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M.; Harris, J.D. Housing quality, psychological distress, and the mediating role of social withdrawal: A longitudinal study of low-income women. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pull, E.; Richard, Å. Domicide: Displacement and dispossessions in Uppsala, Sweden. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2021, 22, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyra, D.S. Conceptualizing the new urban renewal: Comparing the past to the present. Urban Aff. Rev. 2012, 48, 498–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marris, P. Loss and Change (Psychology Revivals): Revised Edition; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ärlemalm, J. Resisting Renoviction: The Neoliberal City, Space and Urban Social Movements; Uppsala Universitet: Uppsala, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tulumello, S. Reconsidering neoliberal urban planning in times of crisis: Urban regeneration policy in a “dense” space in Lisbon. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. Neoliberalism and the Urban. In The SAGE Handbook of Neoliberalism; Swyngedouw, E., Cahill, D., Cooper, M., Konings, M., Primrose, D., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Storper, M. The neo-liberal city as idea and reality. Territ. Politics Gov. 2016, 4, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinson, G.; Morel Journel, C. The neoliberal city–theory, evidence, debates. Territ. Politics Gov. 2016, 4, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H.; Shach-Pinsly, D. Toward a Methodology of Spatial Neighborhood Evaluation to Uncover the “Invisible Spaces” in Neighborhoods Built Through State Initiatives Between 1945 and 1980. Land 2025, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudell, P.; Attuyer, K. Neoliberal ‘regeneration’ and the myth of community participation. In Neoliberal Urban Policy and the Transformation of the City: Reshaping Dublin; MacLaren, A., Kelly, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Arundel, R.; Ronald, R. The false promises of homeownership: Homeowner societies in an era of declining access and rising inequality. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1120–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupers, K. The Social Project: Housing Postwar France; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Listerborn, C.; Molina, I.; Richard, Å. Claiming the right to dignity: New organizations for housing justice in neoliberal Sweden. Radic. Hous. J. 2020, 2, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modlinska, E. Urban Neoliberalism and External Partnerships in the City of Toronto’s Tower Renewal Program. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lovering, J. The relationship between urban regeneration and neoliberalism: Two presumptuous theories and a research agenda. Int. Plan. Stud. 2007, 12, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, T. Missing Marcuse: On gentrification and displacement. City 2009, 13, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R. Extracting value from the city: Neoliberalism and urban redevelopment. Antipode 2002, 34, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFilippis, J. Unmaking Goliath: Community Control in the Face of Global Capital; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Coley, R.L.; Leventhal, T.; Lynch, A.D.; Kull, M. Relations between housing characteristics and the well-being of low-income children and adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, L. Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Urban Marginality; Polity: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, H.J. The failure of urban renewal. Commentary 1965, 39, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol, K.G. The Pruitt-Igoe myth. J. Archit. Educ. 1991, 44, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.; Webber, S. The implications of condominium neighbourhoods for long-term urban revitalisation. Cities 2017, 61, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H.; Orr, Z.; Maizel, Y. Contested homes: Professionalism, hegemony, and architecture in times of change. Space Cult. 2011, 14, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H.; Oxman, R. Of Village and City: Ideology in Israeli Public Planning. J. Urban Des. 2003, 8, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H. The Building Blocks of Public Housing in Israel: Six Decades of Urban Construction Initiated by the State; Ministry of Construction and Housing: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2014. (In Hebrew)

- Gaborit, P. European New Towns the End of a Model? From Pilot to Sustainable Territories. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 230–249. [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson, Y. Demographic Processes in the Land of Israel, 1948–2022; Israeli Institute for National Security Studies (INSS): Tel Aviv, Israel, 2024; Volume 27, p. 37, Update Figure 1. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Asif, S.; Shahar, A.; Aharonson, S.; Spivak, E. Integrated National Master Plan for Construction, Development and Conservation: NOP 35—Main Principles and Policy Measures. Israel. 2005. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ziv, N. Urban renewal in Israel—The dynamics of social and regulatory space. Law Econ. Inst. Isr. 2022, 5, 15–46. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Toledano, H.; Edri, A.; Rotter-Holtz, D. (Eds.) Urban Renewal Report for 2024; Governmental Authority for Urban Renewal: Jerusalem, Israel, 2005. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Shadar, H.; Shach-Pinsly, D. Maintaining Community Resilience through Urban Renewal Processes Using Architectural and Planning Guidelines. Sustainability 2024, 16, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimshoni, Y.; D.S. Building Cities Architects and Planning Ltd. TML 2010 Plan for Urban Renewal, Shivtei Israel Complex. Planning Administration Plans Portal. 2019. Available online: https://www.tabanow.co.il/%D7%AA%D7%91%D7%A2/%D7%A7%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%AA-%D7%92%D7%AA/%D7%AA%D7%9E%D7%9C/2010#google_vignette (accessed on 28 August 2025). (In Hebrew).

- Kiryat Gat Urban Renewal Administration Website (In Hebrew). Available online: https://minheletgat.co.il/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Shadar, H. New Towns: Initial Physical Models, Their Evolution and Future Recommendations. Land 2025, 14, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Israel. Evacuation and Construction Law (Compensation); State of Israel: Jerusalem, Israel, 2006. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- State of Israel. Evacuation and Construction (Compensation) Law, Amendment No. 7; State of Israel: Jerusalem, Israel, 2023. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Freestone, R. A Brief History of New Towns. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberg, S. The Twenty-First-Century New Town Site Planning and Design. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, A.; Salomon-Maman, V.; Moldavsky, Y.; Fundominsky, S.; Mizrahi, A.; Suissa, D. Neighborhood 360°: Indicators for Urban Planning and Development; Ministry of Construction and Housing, Israel Green Building Council: Jerusalem, Israel, 2017. (In Hebrew)

- Frischer, B. Guidelines for Street Planning in Cities: The Street Space; Ministry of Transport and Road Safety, Transportation Planning Department; Ministry of Construction and Housing, Chief Architect’s Department: Jerusalem, Israel, 2009. (In Hebrew)

- Lerman, A. Guide for Planning, Allocating, and Distributing Commercial Services in Residential Neighborhoods; Ministry of Construction and Housing: Jerusalem, Israel, 2008. (In Hebrew)

- Nussbaum, G. Planning Guidelines for Integrating Public, Commercial, Employment, and Residential Buildings; Institute for Research and Development of Educational and Welfare Institutions; Ministry of Construction and Housing, Planning and Engineering Department; Ministry of Interior, Planning Directorate; Israel Land Administration, Planning and Development Department: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2011. (In Hebrew)

- Yaron, R. Planning Guidelines for Allocating Land for Public Uses; Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, Directorate of Development; Ministry of Interior, Planning Directorate; Ministry of Construction and Housing, Programs Department; Ministry of Finance, Budget Department; Institute for Research and Development of Public Institutions and Welfare: Jerusalem, Israel, 2005. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Trop, T.; Sarig, G. Guide for Planning Public Gardens: By Settlement Type, Population Sector, Climatic Zone, and Topography; Ministry of Construction and Housing, Chief Architect’s Department; Ministry of Environmental Protection; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development; Rotem Productions Ltd.: Jerusalem, Israel, 2012. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Korin, Y. Analysis of Residential Neighborhood Densities; Ministry of Construction and Housing, Chief Architect’s Department: Jerusalem, Israel, 2014. (In Hebrew)

- Farchi Tsafrir Architects in Collaboration with GeoData Ltd. Guidelines for Planning the Condominium; Ministry of Construction and Housing, Chief Architect’s Department: Jerusalem, Israel, 2011. (In Hebrew)

- Shinar, A.; Churchman, A.; Mann, A. Examining high-rise construction: Summary and multidisciplinary perspectives. In Examining High-Rise Construction: Literature Review; A. Mann (Head of the Research Team); Ministry of Interior, Planning Administration, Department for Planning and Building Regulations; Technion Research and Development Foundation; Center for Urban and Regional Studies; National Building Research Institute: Jerusalem, Israel, 2001; Volume A, pp. 1–16. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Shinar, A.; Mann, A. High-rise construction: Aspects of urban design and architecture. In Examining High-Rise Construction: Literature Review; A. Mann (Head of the Research Team); Ministry of Interior, Planning Administration, Department for Planning and Building Regulations; Technion Research and Development Foundation; Center for Urban and Regional Studies; National Building Research Institute: Jerusalem, Israel, 2001; Volume A, pp. 37–59. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Tsaraf Harel, I.; Shadar, H. (University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel). Personal communication on high-rise and urban fabric construction in Israel, 2025.

- Levin, D.; Aharon Gutman, M. The self-leverage generation: Toward a turning point in the social debate on urban renewal in Israel. Theory Crit. 2021, 55, 73–99. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Geva, Y.; Rosen, G. A win-win situation? Urban regeneration and the paradox of homeowner displacement. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2022, 54, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainer-Persov, N. Strategies for urban residential renewal: An assessment from the perspective of social fairness. Planning 2019, 16, 131–133. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Geva, Y.; Rosen, G. Socio-spatial outcomes of “evacuation–construction” projects: Houses from within. Planning 2019, 16, 201–224. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Brodkin, A.; Mualem, N. Gentrification in Israel: Displacement of Residents in Demolition and Reconstruction Projects? Center for Urban and Regional Studies—Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning—Technion: Haifa, Israel, 2022. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Alterman, R. Failing Towers: Long-Term Maintenance Problems in Residential High-Rises; Center for Urban and Regional Studies, Technion: Haifa, Israel, 2009. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Eizenberg, A. Urban renewal. In The Planners, the Second Planning—Where to? Hatuka, T., Fenster, T., Eds.; Resling: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2010; pp. 77–93. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Mualem, N. Forever Young? Maintenance Challenges of High-Rise Buildings: Toward a Comprehensive Policy; Center for Urban and Regional Studies, Technion: Haifa, Israel, 2017. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Padan, Y. Demolition and reconstruction: Destroying the past and building the future. Planning 2014, 11, 24–31. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kainer-Persov, N. Paradigm shift in urban renewal in Israel: From poverty eradication to the renewal of the built housing stock as an economic transaction. Planning 2021, 18, 60–90. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Barbot, M. When the history of property rights encounters the economics of convention. Some open questions starting from European history. Hist. Soc. Res. Hist. Sozialforschung 2015, 40, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, T. Regulation by incentives, regulation of the incentives in urban policies. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2010, 2, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Galès, P.; Vitale, T. Governing the Large Metropolis. A Research Agenda; Working Papers du Programme Cities Are Back in Town; HAL: Lyon, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Findeisen, F.; Le Galès, P. Decentralization, Europeanization, State Restructuring, and the Politics of Instruments Accumulation: The Case of the French Housing Sector. Regul. Gov. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigner, H. Neoliberal rationality and neohygienist morality. A Foucauldian analysis of safe and sustainable urban transport policies in France. Territ. Politics Gov. 2016, 4, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Re-conceptualizing housing tenure beyond the owning-renting dichotomy: Insights from housing and financialization. Hous. Stud. 2023, 38, 1512–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šumonja, M. Neoliberalism is not dead–On political implications of COVID-19. Cap. Cl. 2021, 45, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparke, M.; Williams, O.D. Neoliberal disease: COVID-19, co-pathogenesis and global health insecurities. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2022, 54, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatkin, G.; Mishra, V.; Khristine Alvarez, M. Debates Paper: COVID-19 and urban informality: Exploring the implications of the pandemic for the politics of planning and inequality. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 1771–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H. Crisis, urban fabrics, and the public interest: The Israeli experience. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, D.; Ellis, A.; Lloyd, A.; Telford, L. New hope or old futures in disguise? Neoliberalism, the COVID-19 pandemic and the possibility for social change. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L. How can we quarantine without a home? Responses of activism and urban social movements in times of COVID--19 pandemic crisis in Lisbon. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepma, M.; Savini, F.; Coppola, A. Property and values: The affordability, accessibility, and autonomy of collaborative housing. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2025, 25, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenstein, J.D.; Koch, P.; Sanjines, D.; Assandri, C.; Matonte, C.; Osorio, D.; Sarachu, G. Struggles for the decommodification of housing: The politics of housing cooperatives in Uruguay and Switzerland. Hous. Stud. 2022, 37, 955–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).