Optimizing Impervious Surface Distribution and Rainwater Harvesting for Urban Flood Resilience in Semi-Arid Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. Italian City-2

2.1.2. Rizgary Neighborhood

2.2. Soil Conservation Service Curve Number (SCS-CN) Methodology

- Determine the Curve Number (CN):

- Calculation of Potential Maximum Retention ():

- Calculation of the Initial Abstraction ():

- Calculation of Runoff ():

2.3. Rainfall Data

3. Results and Discussion

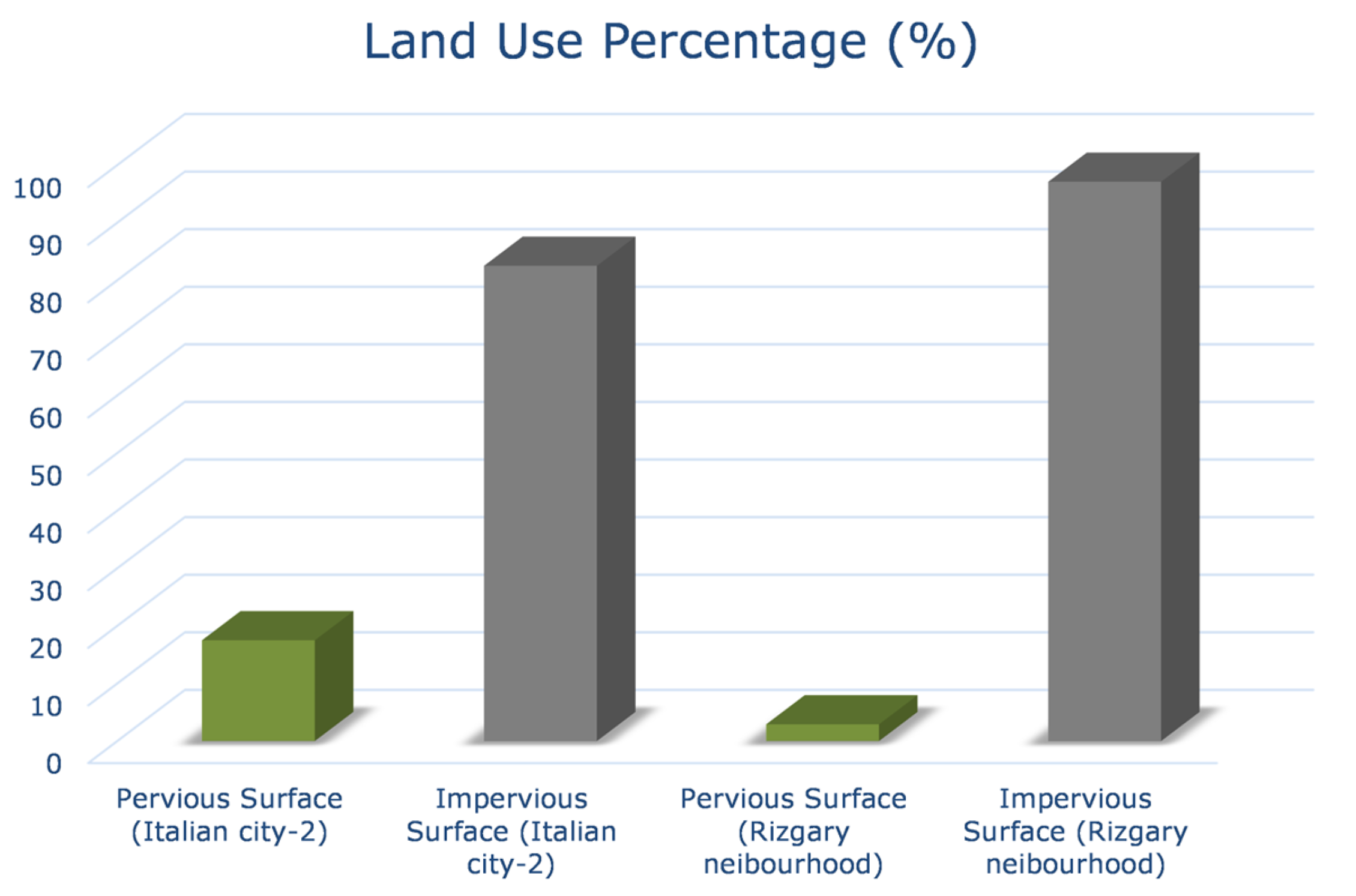

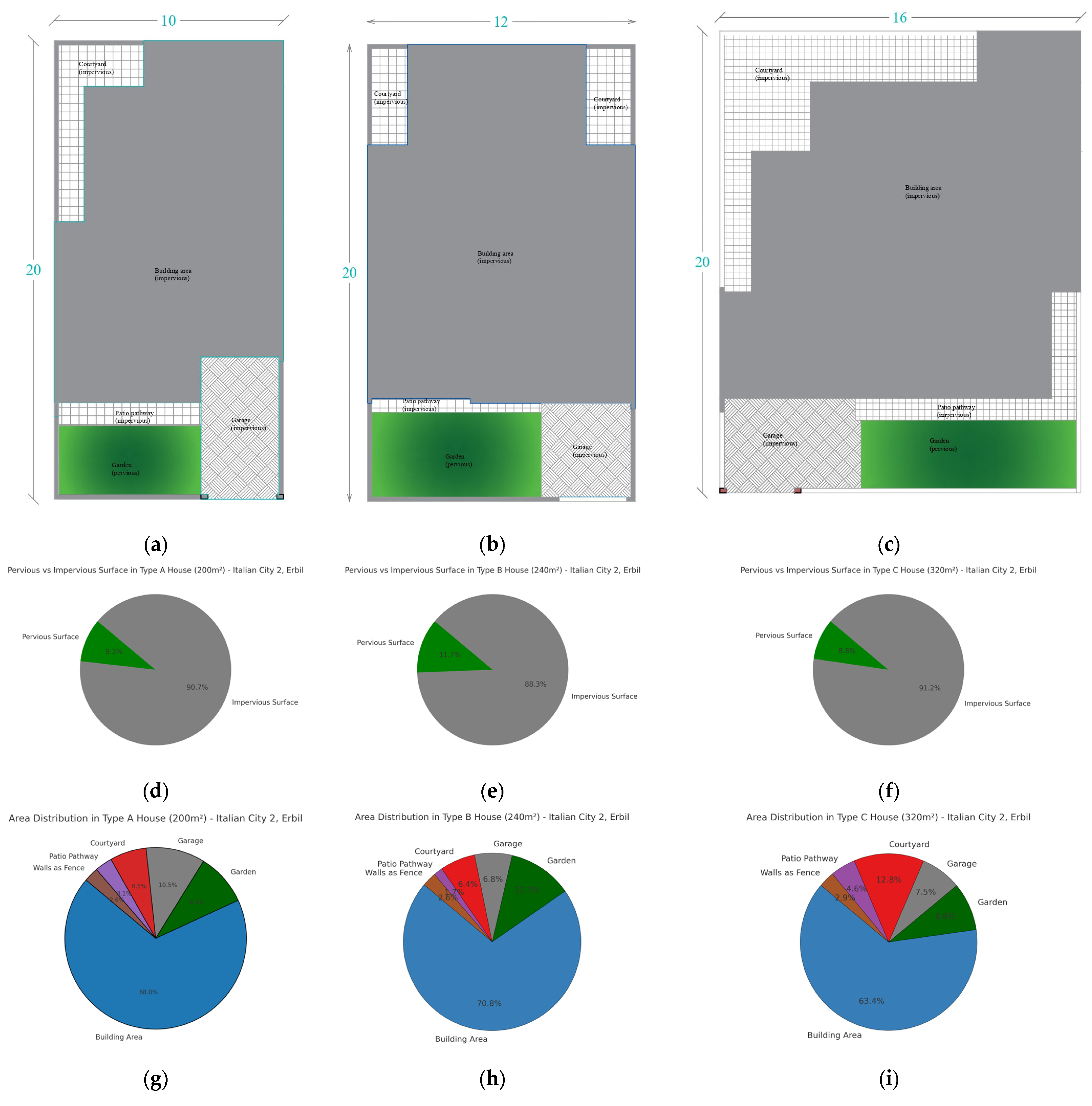

3.1. LULC Analysis by Residential Units

3.1.1. LULC Analysis of Italian City-2 by Residential Units

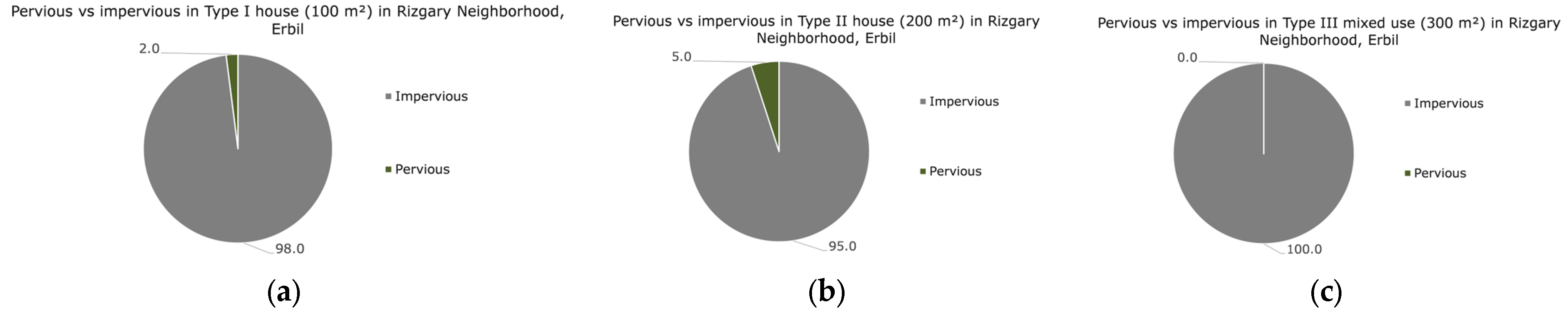

3.1.2. LULC Analysis of Rizgary Neighborhood by Residential Units

- Type I: Units of 100 m2

- Type II: Units of 200 m2

- Type III: Units of ≥300 m2, predominantly located along main roads and currently functioning as commercial buildings with no green cover or pervious surfaces.

3.2. Runoff Volume for Residential Units

3.2.1. Runoff Volume Estimation for Residential Units in Italian City-2

3.2.2. Runoff Volume Estimation for Residential Units in Rizgary Neighborhood

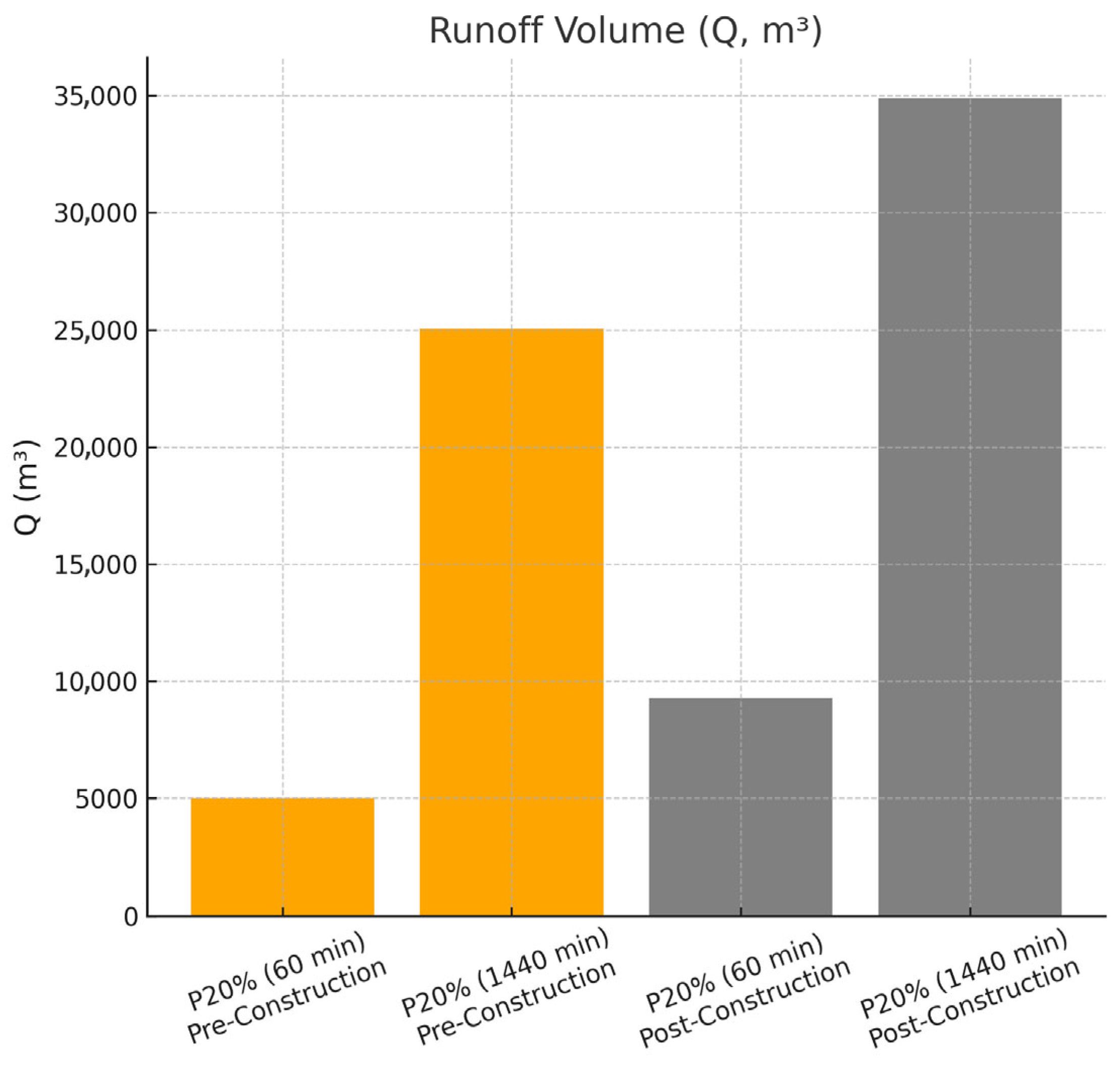

3.3. Hydrological Responses of the Entire Italian City-2

3.4. Rainwater Harvesting Potential and Runoff Reduction in Italian City-2

- 321 houses of 200 m2 (avg. rooftop = 104 m2)

- 635 houses of 240 m2 (avg. rooftop = 123 m2)

- 605 houses of 320 m2 (avg. rooftop = 146 m2)

- Using a design rainfall depth of 54.78 mm (P20%, 1440 min event), the total volume of harvestable rainwater is:

3.5. Redevelopment Proposal for Rizgary Neighborhood Using Multi-Story Buildings

- Reduce impervious surfaces such as roofs, paved yards, and internal driveways;

- Increase pervious areas through the allocation of larger public gardens and green strips;

- Enhance neighborhood functionality by providing more space for public services such as schools, health centers, playgrounds, and parking lots;

- Widen road networks to improve accessibility and reduce congestion.

- Total area of Rizgary Neighborhood: 732,180 m2

- Current unit distribution (approximate based on municipality data and land use analysis):

- Type I (100 m2 plots): 58% of residential lots

- Type II (200 m2 plots): 25% of residential lots

- Type III (≥200 m2 plots along main roads which considered as bussiness and comercial units): 17%

- Multi-story buildings (4–6 floors) will replace all existing units.

- Residential footprint will occupy only 35% of the total area, down from 47.9%.

- Green areas and parks will increase from 2.9% to approximately 20%. This rate include the green and pervious surfaces in residential units, public services and roads.

- Roads will be redesigned with standard widths of 12–15 m (30%).

- Additional 15% of space will be dedicated to public services and parking.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klein, T.; Anderegg, W.R.L. A vast increase in heat exposure in the 21st century is driven by global warming and urban population growth. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 73, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Teng, M.; He, W.; Liu, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, P. Impervious surface area is a key predictor for urban plant diversity in a city undergone rapid urbanization. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.; Page, J.; Zhang, L.; Cong, C.; Ferreira, C.; Jonsson, E.; Näsström, H.; Destouni, G.; Deal, B.; Kalantari, Z. Understanding interactions between urban development policies and GHG emissions: A case study in Stockholm Region. Ambio 2020, 49, 1313–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.A.; Stratopoulos, L.M.; Moser-Reischl, A.; Zölch, T.; Häberle, K.-H.; Rötzer, T.; Pretzsch, H.; Pauleit, S. Traits of trees for cooling urban heat islands: A meta-analysis. Build. Environ. 2020, 170, 106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Szydłowski, M. The Impact of Spatiotemporal Changes in Land Development (1984–2019) on the Increase in the Runoff Coefficient in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, W. Europe’s deadly floods leave scientists stunned. Science 2021, 373, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegaz, R.; Wang, F.; Xu, J. History, causes, and trend of floods in the US: A review. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 13715–13755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, I.A.; Asim, M.; Aslam, A.B.; Jamshed, A. Disaster management cycle and its application for flood risk reduction in urban areas of Pakistan. Urban Clim. 2021, 38, 100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Nielsen, M.; Greatrex, H. Causes, impacts, and mitigation strategies of urban pluvial floods in India: A systematic review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 93, 103751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Zhang, X. Increasing urban flood risk in China over recent 40 years induced by LUCC. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 219, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, T. A weighted overlay analysis for assessing urban flood risks in arid lands: A case study of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Water 2024, 16, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.P.; Al Ruheili, A.; Almarzooqi, M.A.; Almheiri, R.Y.; Alshehhi, A.K. The rain deluge and flash floods of summer 2022 in the United Arab Emirates: Causes, analysis and perspectives on flood-risk reduction. J. Arid Environ. 2023, 215, 105013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaj, M.R.; Noor, H.; Dastranj, A. Investigation and simulation of flood inundation hazard in urban areas in Iran. Geoenviron. Disasters 2021, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansari, N. Topography and climate of Iraq. J. Earth Sci. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nassar, A.R.; Kadhim, H. Mapping flash floods in Iraq by using GIS. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2021, 8, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, A.M.; Muhammed, H.H.; Szydlowski, M. Extreme rainfalls as a cause of urban flash floods: A case study of the erbil-kurdistan region of iraq. Acta Sci. Pol. Form. Circumiectus 2019, 18, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, N.; Al-Ansari, N.; Sissakian, V.; Fahmi, K.J.; Abed, S.A. Climate change: Droughts and increasing desertification in the Middle East, with special reference to Iraq. Engineering 2022, 14, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muhyi, A.H.A.; Aleedani, F.Y.K. Impacts of global climate change on temperature and precipitation in basra city, iraq. Basrah J. Sci. 2022, 40, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethaib, S.; Zubaidi, S.L.; Al-Ansari, N. Evaluation water scarcity based on GIS estimation and climate-change effects: A case study of Thi-Qar Governorate, Iraq. Cogent. Eng. 2022, 9, 2075301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, F.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, S.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, S. Permeability control and flood risk assessment of urban underlying surface: A case study of Runcheng south area, Kunming. Nat. Hazards 2022, 111, 661–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Kim, J.-H.; Li, W.; Yang, P.; Cao, Y. Exploring the impact of green space health on runoff reduction using NDVI. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 28, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, M.; Hu, Y.; Shi, T.; Qu, X.; Walter, M.T. Effects of urbanization on direct runoff characteristics in urban functional zones. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöman, J.D.; Gill, S.E. Residential runoff–The role of spatial density and surface cover, with a case study in the Höjeå river catchment, southern Sweden. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, W.D.; Bonta, J.; Thurston, H.; Warnemuende, E.; Smith, D.R. Impacts of impervious surface on watershed hydrology: A review. Urban Water J. 2005, 2, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Engel, B.A.; Chen, J.; Sun, H. Green infrastructure practices simulation of the impacts of land use on surface runoff: Case study in Ecorse River watershed, Michigan. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoener, G. Urban Runoff in the U.S. Southwest: Importance of Impervious Surfaces for Small-Storm Hydrology. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2018, 23, 05017033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Chen, L.; Wei, W. Exploring the Linkage between Urban Flood Risk and Spatial Patterns in Small Urbanized Catchments of Beijing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirker, A.N.; Toran, L. When impervious cover doesn’t predict urban runoff: Lessons from distributed overland flow modeling. J. Hydrol. 2023, 621, 129539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, U.; Vahmani, P.; Jones, A.D. Quantifying the city-scale impacts of impervious surfaces on groundwater recharge potential: An urban application of WRF–Hydro. Water 2022, 14, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabr, C. A study on the urban form of Erbil city (the capital of Kurdistan region) as an example of historical and fast growing city. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. CD-ROM 2014, 3, 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Ma, C.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, K.; Han, H. A review on applications of urban flood models in flood mitigation strategies. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C.M.; Liu, J. Review on urban storm water models. Eng. J. Wuhan Univ. 2018, 51, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). National Engineering Handbook: Part 630—Hydrology; USDA Soil Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 11–15.

- Shadeed, S.; Almasri, M. Application of GIS-based SCS-CN method in West Bank catchments, Palestine. Water Sci. Eng. 2010, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alataway, A. SCS-CN and GIS-based approach for estimating runoff in Western Region of Saudi Arabia. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2023, 11, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghobari, H.; Dewidar, A.; Alataway, A. Estimation of surface water runoff for a semi-arid area using RS and GIS-based SCS-CN method. Water 2020, 12, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, K.S.; Singh, S.K. Estimation of surface runoff from semi-arid ungauged agricultural watershed using SCS-CN method and earth observation data sets. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2017, 1, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushandi, E.; Al Ajmi, M. Assessment of hydrological extremes for arid catchments: A case study in Wadi Al Jizzi, North-West Oman. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laassilia, O.; Saghiry, S.; Ouazar, D.; Bouziane, A.; Hasnaoui, M.D. Flood forecasting with a dam watershed event-based hydrological model in a semi-arid context: Case study in Morocco. Water Pract. Technol. 2022, 17, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mudaris, S.B. The Residential Pattern in Arbil City (an Analytical Study in Urban Geography); Salahaddin University-Erbil: Erbil, Iraq, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, A.R.A.; Schwamback, D.; Ballarin, A.S.; Ramirez-Avila, J.J.; Vasconcelos Neto, J.G.; Oliveira, P.T.S. Toward a better understanding of curve number and initial abstraction ratio values from a large sample of watersheds perspective. J. Hydrol. 2025, 655, 132941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.H.; Jiang, R.; Woodward, D.; Hjelmfelt, A.; Van Mullem, J.; Quan, Q. Runoff curve number method: Examination of the initial abstraction ratio. In Proceedings of the Second Federal Interagency Hydrologic Modeling Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 28 July–1 August 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, K.J.; Engel, B.A.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Harbor, J. Effects of initial abstraction and urbanization on estimated runoff using CN technology 1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2006, 42, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, D.A.; M Amen, A.R.; Mustafa, A.; Yüce, M.I.; Szydłowski, M. Comparative Analysis of Developed Rainfall Intensity–Duration–Frequency Curves for Erbil with Other Iraqi Urban Areas. Water 2022, 14, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adapt, C. Berlin Biotope Area Factor—Implementation of Guidelines Helping to Control Temperature and Runoff. 2014. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/metadata/case-studies/berlin-biotope-area-factor-2013-implementation-of-guidelines-helping-to-control-temperature-and-runoff (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Aziz, S.Q.; Saleh, S.M.; Muhammad, S.H.; Ismael, S.O.; Ahmed, B.M. Flood Disaster in Erbil City: Problems and Solutions. Environ. Prot. Res. 2023, 3, 217–381. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, D.; Foster, G.; Moldenhauer, W. Storm pattern effect on infiltration, runoff, and erosion. Trans. ASAE 1988, 31, 414–0420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrane, S.J. Impacts of urbanisation on hydrological and water quality dynamics, and urban water management: A review. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016, 61, 2295–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.G.; Aziz, S.Q.; Wu, B.; Ahmed, M.S.; Jha, K.; Wang, Z.; Nie, Y.; Huang, T. Application of Sponge City for Controlling Surface Runoff Pollution. Asian J. Environ. Ecol. 2024, 23, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, D.A.; Ghisi, E. Impact of residential rainwater harvesting on stormwater runoff. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dola, I.A.; Hasan, M.; Rahman, A. Assessment of rooftop area for rainwater harvesting in densely populated city: Advancing sustainable water management practices. Int. J. Energy Water Resour. 2025, 9, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsoom, A.; Aslam, B.; Ismail, S.; Thaheem, M.J.; Ullah, F.; Zahoor, H.; Musarat, M.A.; Vatin, N.I. Assessing rainwater harvesting potential in urban areas: A building information modelling (BIM) approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Peng, C.; Chiang, P.-C.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z. Mechanisms and applications of green infrastructure practices for stormwater control: A review. J. Hydrol. 2019, 568, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrill, S.; Segura-Castillo, L.; Petit-Boix, A.; Rieradevall, J.; Gabarrell, X.; Josa, A. Environmental performance of rainwater harvesting strategies in Mediterranean buildings. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Mahmoud, A.; Jones, K.D.; Bezares-Cruz, J.C.; Guerrero, J. A comparison of three types of permeable pavements for urban runoff mitigation in the semi-arid South Texas, USA. Water 2019, 11, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LULC Category | Runoff CN for Different Soil Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| Impervious areas: Paved parking lots, roofs, driveways, etc. (excluding right of way) | 98 | 98 | 98 | 98 |

| Open space (lawns, parks, golf courses, cemeteries, etc.): Good condition (grass cover > 75%) | 39 | 61 | 74 | 80 |

| Bare soil | 77 | 86 | 91 | 94 |

| Duration (min) | 5-Year (P20%) Rainfall (mm) | 100-Year (P1%) Rainfall (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 60 | 20.9 | 35.5 |

| 1440 | 54.8 | 95.6 |

| House Type | Time (60 min) | Time (1440 min) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q (m3) for P1% | Q (m3) for P20% | Q (m3) for P1% | Q (m3) for P20% | |

| Type A | 5.29 | 2.62 | 17.00 | 8.98 |

| Type B | 6.12 | 2.98 | 20.07 | 10.50 |

| Type C | 8.54 | 4.25 | 27.28 | 14.45 |

| House Type | Time (60 min) | Time (1440 min) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q (m3) for P1% | Q (m3) for P20% | Q (m3) for P1% | Q (m3) for P20% | |

| Type I | 2.97 | 1.57 | 8.92 | 4.87 |

| Type II | 5.67 | 2.91 | 17.49 | 9.42 |

| Type III | 9.23 | 4.96 | 27.12 | 14.94 |

| House Type | No. of Houses | Rooftop Area (m2) | Volume per House (m3) | Total Volume (m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A—200 m2 | 321 | 104 | 5.12 | 1645 |

| Type B—240 m2 | 635 | 123 | 6.06 | 3850 |

| Type C—320 m2 | 605 | 146 | 7.19 | 4354 |

| Total | 1561 | – | – | 9849 m3 |

| Scenario | CN Value | Runoff (Q) at P = 20% (60 min) |

|---|---|---|

| Current Urban Fabric | 97.3 | 10,493.18 m3 |

| Redeveloped (Multi-Story) | 92 | 6069.25 m3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustafa, A.; Szydłowski, M.; Qarani Aziz, S. Optimizing Impervious Surface Distribution and Rainwater Harvesting for Urban Flood Resilience in Semi-Arid Regions. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120523

Mustafa A, Szydłowski M, Qarani Aziz S. Optimizing Impervious Surface Distribution and Rainwater Harvesting for Urban Flood Resilience in Semi-Arid Regions. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):523. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120523

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustafa, Andam, Michał Szydłowski, and Shuokr Qarani Aziz. 2025. "Optimizing Impervious Surface Distribution and Rainwater Harvesting for Urban Flood Resilience in Semi-Arid Regions" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120523

APA StyleMustafa, A., Szydłowski, M., & Qarani Aziz, S. (2025). Optimizing Impervious Surface Distribution and Rainwater Harvesting for Urban Flood Resilience in Semi-Arid Regions. Urban Science, 9(12), 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120523