Abstract

Access to safe water and sanitation remains a pressing challenge in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rapid urbanisation, fragile governance, and increasing climate hazards continue to undermine the sustainability of WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) services. This study examines whether Mozambique’s normative and institutional framework effectively supports sustainable urban WASH service delivery in Beira, the country’s second-largest city. Combining a critical policy review with six semi-structured interviews involving institutional actors and community leaders, the research employs a qualitative, phenomenological design to explore the interaction between national frameworks and local practices. Findings reveal five interrelated dimensions shaping sustainability: governance coordination, infrastructure robustness and maintenance, community participation, climate resilience, and financial viability. Although post-disaster investments and recent policy reforms have led to improvements, significant challenges persist. These include overlapping institutional mandates, underdeveloped preventive maintenance systems, limited recognition and support for community-led initiatives, fragmented climate adaptation efforts, and strong dependence on external funding. The study also reveals how historical legacies, particularly colonial-era governance structures, continue to shape water and sanitation delivery. By integrating policy analysis with local perspectives, the paper contributes to debates on WASH sustainability in African cities, particularly in climate-vulnerable secondary urban centres. It highlights the need for systemic reforms that clarify institutional roles, institutionalise maintenance practices, formalise community engagement, embed nature-based adaptation strategies, and strengthen financial transparency. These changes are essential if Beira, and similar cities across sub-Saharan Africa, are to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 6 under mounting climate pressure.

1. Introduction

Access to safe water and sanitation is recognised as a fundamental human right [] and constitutes the core of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6, which aims to ensure universal and equitable access by 2030. Despite international commitments and substantial investments, progress remains uneven across Sub-Saharan Africa, where urban growth, fragile governance, and climate-related hazards pose critical challenges to the sustainability of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services [,]. Recent reviews further emphasise that rurality, climate change, low investment in infrastructure, and weak community engagement remain key barriers to meeting SDG 6 in the region [,].

Mozambique illustrates these dynamics. National surveys indicate that only 61% of the urban population and 45% of the rural population have access to safely managed drinking water, while sanitation services lag even further behind []. According to the most recent national assessment, only 64% of Beira’s households are connected to the piped water network, while less than 40% have access to improved sanitation facilities [,]. The government has advanced successive reforms in the sector, most notably through the Water Law (1991, revised 2016) [,], the National Water Policy (1995), and, more recently, the drafting of a new Water and Sanitation Law aimed at improving service regulation and sustainability. Yet, despite these efforts, a persistent disconnect remains between national policy frameworks and implementation capacity, particularly in secondary cities [].

Beira, Mozambique’s second-largest urban centre by population [], exemplifies the interplay of opportunities and challenges in urban water governance. While often classified as a secondary city in global urban typologies, Beira plays a nationally significant role as Mozambique’s main coastal and economic hub outside the capital. With a rapidly expanding population and a strategic coastal location, Beira faces recurrent extreme weather events, notably Cyclones Idai (2019) and Eloise (2021), which severely disrupted WASH infrastructure. Studies show that these shocks deepened existing inequalities and highlighted the fragility of basic services [,]. Post-disaster investments have prioritised drainage rehabilitation and coastal protection, but questions remain regarding institutional coordination, preventive maintenance, and financial viability of services [].

Existing research highlights the need for integrated approaches that bridge governance structures, community engagement, and climate resilience [,]. However, few studies in Mozambique systematically combine sectoral policy analysis with the lived experiences of institutional and community actors, particularly in secondary urban contexts beyond the capital. This study responds to that gap by focusing on Beira — a mid-sized, climate-vulnerable city where colonial legacies in spatial planning and fragmented governance continue to shape uneven patterns of service delivery [].

Furthermore, while Mozambique has adopted progressive sectoral frameworks aligned with SDG 6, their realisation is frequently constrained by overlapping mandates, donor-driven projects, and under-resourced municipal systems. These constraints are common in other African cities as well [,].

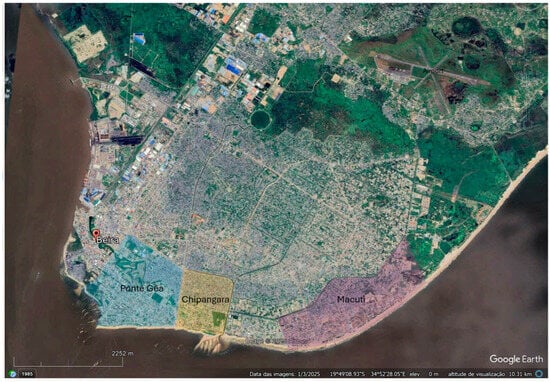

Against this background, this study investigates the sustainability of urban water and sanitation services in Beira, Mozambique. It explores how national policies and institutional arrangements are perceived and enacted by municipal authorities, service providers, regulators, and community leaders. By triangulating policy review and interview data, the research identifies critical gaps and opportunities across five dimensions: governance and institutional coordination, infrastructure robustness, community participation, climate resilience, and financial viability. The interviews with institutional and community actors were conducted between 10 June and 25 July 2025, across the neighbourhoods of Ponta Gêa, Chipangara, and Macuti.

The study contributes to both academic debates on WASH governance and to policy discussions on SDG implementation by offering insights grounded in local realities of a highly exposed and often-overlooked secondary city. Building upon these aims, the study was guided by two hypotheses: (i) institutional fragmentation among water and sanitation agencies constrains the long-term sustainability of service delivery in Beira, and (ii) limited community participation diminishes adaptive capacity and undermines system resilience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background on Beira

To support the geographic context of this study, two location maps are included. Figure 1 shows the position of Beira within Southern Africa, highlighting its coastal location and regional relevance. Figure 2 provides a detailed view of Beira’s urban layout, including the key neighbourhoods analysed in this study: Ponta Gêa, Chipangara, and Macuti.

2.2. Research Design

This study adopted a qualitative research design with a phenomenological orientation, suitable for capturing the perceptions and lived experiences of actors involved in the provision and use of WASH services. Such an approach allows moving beyond descriptive accounts to uncover shared meanings and underlying dynamics in how policies and institutional arrangements translate into practice [].

The phenomenological orientation enabled the study to understand how stakeholders make sense of service delivery dynamics, rather than merely describing institutional performance. This approach is particularly relevant in fragile governance and climate-vulnerable settings, where local agency and institutional interplay often shape service outcomes are shaped by the interaction between formal institutions and community agency [,].

Figure 1.

Regional location of Beira within Mozambique and Southern Africa. Source: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), under the United Nations Open Data License [].

Figure 2.

Urban map of Beira showing the study neighbourhoods. Image source: Google Earth, © Google 202. Map prepared by the authors for illustrative purposes.

2.3. Study Context

The research was conducted in Beira, Sofala Province, Mozambique. Fieldwork took place between 10 June and 25 July 2025 and involved interviews with institutional representatives and community leaders from the neighbourhoods of Ponta Gêa, Chipangara, and Macuti. Beira is the country’s second-largest urban centre, with over half a million residents [,].

The city’s water supply and sanitation system involves multiple entities: Serviços de Água e Saneamento da Beira (SASB, Water and Sanitation Services of Beira), Águas da Região Centro (AdRC, Waters of the Central Region), Administração de Infraestruturas de Água e Saneamento (AIAS, Water and Sanitation Infrastructure Administration), Conselho de Regulação de Águas (CRA, Water Regulatory Council), and the Conselho Municipal da Beira (CMB, Beira Municipal Council). Alongside these formal actors, community-based committees manage localised standpipes and small-scale infrastructure, reflecting broader debates on decentralisation and community participation in Mozambique [].

2.4. Participants and Sampling

A total of six semi-structured interviews were conducted between June and July 2025, involving two categories of participants:

- Institutional actors (n = 3): representatives from Serviços de Água e Saneamento da Beira (SASB, Water and Sanitation Services of Beira), Águas da Região Centro (AdRC, Waters of the Central Region), and Administração de Infraestruturas de Água e Saneamento (AIAS, Water and Sanitation Infrastructure Administration). These participants were selected through purposive sampling given their strategic roles in water supply and sanitation management in Beira.

- Community leaders (n = 3): recognised leaders from the neighbourhoods of Ponta Gêa, Chipangara, and Macuti. These participants were identified via snowball sampling starting with local water committees, ensuring diverse perspectives from areas with varying levels of service coverage and vulnerability to climate risks.

Although the sample size was small (n = 6), thematic saturation was reached after the fifth interview, with no new relevant themes emerging. This follows established qualitative guidance on sample sufficiency in phenomenological designs [].

All interviews were conducted in alignment with ethical research principles. Participants were informed of the study’s objectives, provided verbal and written consent, and agreed to audio recording. Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured throughout. Institutional consent for interviews was obtained where required.

Table 1 provides a summary of the methodological design adopted in this study.

Table 1.

Summary of the methodological design of the study, including sampling, data collection, and analysis.

2.5. Data Collection

A semi-structured interview guide was developed drawing on the WASH sustainability framework proposed by Van der Byl & Carter [], and adapted to the Mozambican context. It covered five domains: (i) governance and coordination, (ii) infrastructure and operations, (iii) participation and inclusion, (iv) climate resilience, and (v) financial viability. The interview guide is included in Appendix A to ensure transparency.

Interviews lasted on average 48 min, were conducted in Portuguese, and included ad hoc translation into Sena when required. To ensure accuracy, translations were validated by a bilingual assistant and cross-checked during transcription.

2.6. Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using Microsoft Excel. A hybrid thematic approach [] was used, combining deductive coding (based on the five sustainability domains) with inductive identification of emergent themes.

Although Excel is not a dedicated qualitative software, it enabled effective coding and categorisation through a structured matrix. A codebook was developed and maintained throughout the process to ensure traceability.

To ensure analytical reliability, 30% of the transcripts were double-coded independently by two researchers, resulting in a Cohen’s Kappa score of 0.81, indicating substantial inter-coder agreement.

2.7. Research Rigour

The study applied the four trustworthiness criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba [] to strengthen qualitative rigour:

- Credibility was enhanced through member checking with four participants;

- Transferability was supported through thick description of the study context and participant profiles;

- Dependability was addressed by maintaining an audit trail of coding decisions and reflections;

- Confirmability was ensured through reflexive journaling and peer debriefing during analysis [].

Extended summaries of all interviews are provided in Appendix B, and additional analytical material is included in Appendix C to support transparency and allow readers to evaluate the validity of interpretations.

3. Results

The analysis of six interviews and supporting policy documents revealed five interdependent dimensions shaping the sustainability of WASH services in Beira: (i) governance and institutional coordination, (ii) infrastructure robustness and maintenance, (iii) community participation, (iv) climate resilience, and (v) financial viability. These are presented below with illustrative quotations from institutional and community actors.

3.1. Governance and Institutional Coordination

Respondents consistently emphasised the problem of fragmented and overlapping mandates among AIAS, AdRC, SASB, and the Municipality. While national legislation assigns responsibilities, operational boundaries remain unclear, often leading to duplication or inaction.

“When a pipe bursts, sometimes two different institutions claim responsibility, and sometimes nobody comes. The community does not know who to call.”(Institutional actor, July 2025)

Community leaders confirmed this perception, noting that lack of clarity delayed responses and reduced accountability. Some expressed optimism that the new Water and Sanitation Law, once regulated, could bring greater clarity. However, institutional participants also warned that without functional mechanisms for coordination, legal reforms alone would not resolve the issue.

“The law will not solve things if there is no daily cooperation between institutions.”(Institutional actor, June 2025)

This institutional fragmentation undermines service efficiency and erodes community trust, reinforcing a gap between policy frameworks and practice [,]. Similar coordination challenges have been reported in other Southern African contexts, where overlapping mandates and weak inter-agency communication hinder effective WASH service delivery [].

3.2. Infrastructure Robustness and Maintenance

Infrastructure weaknesses were highlighted as a major source of service disruptions. Frequent water supply pipeline bursts, ageing networks, and delayed repairs were reported across multiple neighbourhoods.

“In December 2024, a major pipe in Inhamízua broke, and it took more than a week to repair. People survived with water from neighbours’ wells and informal vendors.”(Community leader, June 2025)

Institutional actors acknowledged that although donor-funded projects have recently supported drainage rehabilitation and coastal protection, preventive maintenance remains underdeveloped. Most interventions are reactive, responding to crises rather than preventing them.

Community leaders noted that minor issues, such as broken taps at standpipes, could sometimes be addressed locally, but larger problems were beyond their capacity.

“We manage to replace small parts, but when the pipes underground collapse, it is out of our hands.”(Community leader, July 2025)

This highlights the mismatch between large-scale infrastructure investments and the neglect of small-scale, daily maintenance needs. This pattern has been observed across sub-Saharan Africa, where preventive systems are often weak or underfunded [,].

3.3. Community Participation and Empowerment

The role of community water committees varied significantly across neighbourhoods. In general, these committees operated informally, with limited financial and technical resources. Leaders expressed frustration over the lack of recognition and integration into official decision-making structures.

“We try to mobilise neighbours to contribute small amounts, but without recognition from the authorities, our work is limited.”(Community leader, July 2025)

An exception was Ponta Gêa, where a self-managed standpipe system allowed the community to collect and use revenues to fund small repairs. This model was widely praised by interviewees as an example of effective local management.

“Here in Ponta Gêa, when something breaks, we have funds collected from users to fix it quickly. We don’t wait for the Municipality.”(Community leader, June 2025)

This case suggests that empowering community structures with formal recognition and modest resources could strengthen sustainability, provided mechanisms for accountability are also in place []. Comparative studies in East and Southern Africa support this perspective, showing that community-led systems can increase responsiveness and ownership when appropriately supported [,].

3.4. Climate Resilience to Extreme Events

All respondents recognised climate shocks as a central challenge for WASH sustainability in Beira. Cyclones Idai (2019) and Eloise (2021) disrupted services for weeks, destroying infrastructure and contaminating water sources.

Institutional actors reported some progress in integrating resilience, including drainage rehabilitation and nature-based interventions such as wetland restoration along the Chiveve River. However, most of these initiatives were described as project-driven and donor-led, without integration into long-term planning.

“The drainage system is being improved, but adaptation projects depend on external funding. They are not yet part of our routine planning.”(Institutional actor, July 2025)

Community members, meanwhile, emphasised recurring flooding and the lack of green spaces to absorb excess water.

“Every rainy season we are afraid. The water rises quickly, and our wells are contaminated.”(Community leader, July 2025)

The interviews suggest that while resilience is increasingly acknowledged, it remains fragmented and insufficiently mainstreamed into WASH and urban planning systems [,,].

Recent studies reinforce this finding, highlighting that climate resilience measures in African cities are often implemented in isolation, without systemic integration or long-term planning frameworks [].

3.5. Financial Sustainability

Finally, financial viability was widely perceived as a bottleneck for sustaining WASH services. Institutional actors explained that tariffs remain too low to ensure cost recovery, forcing reliance on cross-subsidies and donor financing.

“The social tariff is necessary for poor families, but it does not cover operational costs. Without external funding, the system cannot survive.”(Institutional actor, June 2025)

Community leaders, however, questioned the fairness of tariff increases when service quality remained unreliable.

“We are asked to pay more, but the water does not come every day. People lose trust.”(Community leader, July 2025)

Several participants suggested that more transparent communication on tariff-setting and reinvestment of revenues into visible service improvements could increase willingness to pay. Similar tensions between affordability and cost-recovery have been documented in other African cities [,,].

Recent reviews confirm that weak tariff structures, donor dependence, and poor transparency remain major barriers to financial sustainability in urban WASH systems [,].

In summary, Beira’s WASH sector shows progress in post-disaster investments and policy reform, but systemic challenges persist. Institutional overlaps and unclear mandates undermine governance. Infrastructure remains fragile due to underfunded preventive maintenance. Community participation, though present, lacks formal recognition and resources. Climate adaptation measures are emerging but remain fragmented. Financial sustainability is weakened by low tariffs, dependency on donors, and limited transparency.

4. Discussion

The sustainability of WASH services in Beira reflects broader tensions between ambitious national policy frameworks, donor-driven investments, and the everyday realities of service provision in a climate-vulnerable secondary city. The findings confirm that despite important reforms, including the drafting of a new Water and Sanitation Law, the implementation gap between policy and practice remains wide. Section 4 situates Beira’s case within regional and global debates, drawing out implications for governance, infrastructure, participation, climate resilience, and financial sustainability.

4.1. Governance and Institutional Complexity

The interviews revealed widespread concern about overlapping mandates among local water and sanitation authorities. This fragmentation weakens accountability and delays responses to breakdowns, undermining trust in formal systems. Similar patterns have been observed in Lusaka, Dar es Salaam, and Maputo, where decentralisation has devolved responsibilities without adequate mechanisms for coordination [].

The persistence of these overlaps cannot be understood solely as administrative inefficiency. As Santos et al. [] argue, Mozambique’s colonial spatial planning left a legacy of fragmented urban governance, with responsibilities split across layers of centralised and municipal institutions. Beira exemplifies how such historical “moorings” still influence contemporary service provision. Unless reforms explicitly address these path dependencies, the new Water and Sanitation Law risks reproducing the same institutional weaknesses under new labels.

Recent regional reviews also emphasise the need for integrated institutional frameworks and clearer accountability chains to strengthen WASH service delivery in secondary urban centres [].

Importantly, local perspectives in this study emphasised not only confusion about mandates but also a lack of day-to-day cooperation between agencies. This suggests that beyond legal clarity, functioning coordination platforms and shared operational protocols are necessary to ensure responsive service provision.

4.2. Infrastructure: From Rehabilitation to Sustainable Maintenance

Infrastructure robustness emerged as another key challenge. While post-Idai investments have channelled substantial resources into drainage rehabilitation and coastal protection, everyday service reliability remains compromised by ageing networks and delayed repairs. This confirms what regional studies have found: that African WASH sectors often prioritise high-visibility, donor-funded projects over long-term maintenance systems [].

A recent water supply pipeline burst in Inhamízua illustrates the costs of reactive approaches, forcing residents to rely on unsafe sources and informal vendors. In Beira, as elsewhere, the neglect of preventive maintenance creates a paradox where capital investments deteriorate quickly, undermining their intended benefits. Emerging literature from other fragile contexts confirms that maintenance budgets, asset registries, and repair teams at the municipal level are critical for system resilience [,].

4.3. Community Participation: Between Informality and Innovation

Community-level participation in Beira presents both limitations and opportunities. Water committees in Chipangara and Macuti operated with minimal resources and lacked legal recognition, limiting their effectiveness. Yet, Ponta Gêa’s self-managed standpipe system stands out as a positive example of local innovation, where user fees are reinvested into small-scale repairs, reducing dependence on formal institutions.

This echoes findings from other African contexts, where empowered and formally recognised community structures contributed to more sustainable services [,]. However, research also warns that community participation often remains symbolic unless accompanied by institutional support and safeguards against elite capture [].

A pilot programme in Tanzania similarly showed that structured community participation, when supported by formal institutions, can significantly enhance service sustainability and public health outcomes [].

In Beira, the results suggest that scaling up participatory models could increase responsiveness and resilience, particularly if accompanied by technical training and modest operational funds for water committees.

4.4. Climate Resilience and the Challenge of Mainstreaming

Beira’s location on a low-lying coastal plain exposes it to extreme climate risks, making resilience a cornerstone of sustainability. The interviews underscored the devastating impacts of Cyclones Idai and Eloise. Post-disaster projects indicate growing recognition of the role of climate adaptation.

Yet, as in many African cities, resilience measures remain fragmented and project-driven, heavily reliant on donor funding []. Institutional actors acknowledged that climate considerations are not yet systematically embedded into WASH planning. This reflects a broader trend across African cities, where Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) and green infrastructure are promoted but not fully operationalised due to governance gaps [].

Recent work also recommends the integration of wetland restoration, urban drainage improvements, and local green space management into broader WASH infrastructure planning to build systemic resilience [].

4.5. Financial Viability: Balancing Affordability and Cost Recovery

The study found that financial fragility continues to undermine sustainability. While social tariffs are vital for ensuring access among poor households, they fall short of covering operational costs, leaving utilities dependent on donor transfers [,,].

From the community perspective, tariff increases without visible service improvements erode trust. This aligns with regional analyses showing that participatory tariff-setting processes, coupled with clear reinvestment strategies, can enhance compliance and reduce resistance [].

In Beira, enhancing transparency and engaging users in financial decision-making could be achieved through communication campaigns and the publication of simplified budget performance reports at neighbourhood level.

4.6. Comparative Analysis Across Neighbourhoods

Although the previous thematic sections addressed common challenges affecting Beira’s water and sanitation system, the interviews reveal notable differences across the three studied neighbourhoods, Ponta Gêa, Chipangara, and Macuti, in terms of infrastructure quality, community engagement, exposure to climate risks, and perceived institutional responsiveness. Section 4.6 highlights these differences to underscore the uneven geography of service provision in the city.

Infrastructure reliability varies markedly between the neighbourhoods. In Ponta Gêa, residents benefit from relatively stable service coverage. While occasional issues such as pipe bursts and low pressure on upper floors are reported, access is generally consistent. In contrast, Chipangara faces systemic failures: entire units have experienced more than a year without piped water, despite continuing to receive water bills. The infrastructure is old and frequently damaged, and responses to breakdowns are often delayed or absent. Macuti falls between these extremes—it has some coverage, but its coastal location makes the network highly susceptible to flood-related disruptions and erosion.

“We went more than a year without piped water but still received bills. We complained, but nothing changed.”(Community leader, Chipangara, July 2025)

Levels of community participation differ significantly across the neighbourhoods. In Ponta Gêa, a relatively strong example of participatory water governance is evident in a self-managed standpipe, where local committees oversee maintenance, resolve user disputes, and encourage water conservation. Chipangara also has water committees, but these are largely inactive due to a lack of training, financial support, and recognition by service providers. Macuti shows moderate engagement, participating in public meetings and project consultations, particularly during flood response planning, but its participation tends to be reactive and inconsistent.

“We have a committee in Ponta Gêa, and even though we lack formal support, we manage our standpipe and make sure people don’t misuse the water.”(Community leader, Ponta Gêa, July 2025)

The interviews clearly show that Macuti is the most climate-exposed of the three neighbourhoods. Located along the coast, it suffers from tidal surges, coastal erosion, and storm impacts. Residents describe frequent latrine overflows during rainy seasons, creating severe sanitation hazards. Chipangara, located in a low-lying floodplain, also experiences heavy flooding that disrupts water and sanitation infrastructure, but is somewhat better protected from tidal activity. Ponta Gêa, although not immune to storm events, has comparatively better drainage and receives faster institutional responses to climate-related emergencies.

“When the floods come, sewage mixes with rainwater in the streets. It happened during Idai and still happens today.”(Community leader, Macuti, June 2025)

Perceptions of how institutions respond to community needs are sharply divided. In Ponta Gêa, residents feel moderately supported; they are often consulted in infrastructure planning processes and feel they can reach municipal staff when issues arise. Chipangara residents, however, express deep frustration with institutional inaction, citing ignored complaints, lack of clarity on responsibility, and prolonged service disruptions. Macuti receives intermittent attention, particularly for climate resilience projects like coastal defences and drainage cleaning, but community leaders remain sceptical about the durability and reach of such interventions.

“We report issues, but no one knows if it’s the municipality, AIAS or AdRC who should fix it. It’s always unclear.”(Community leader, Chipangara, June 2025)

These differences are summarised in Table 2, which consolidates the key distinctions in service provision, community engagement, climate vulnerability, and institutional response across the three neighbourhoods.

Table 2.

Comparative Differences Across Neighbourhoods in Beira (Based on field interviews, June–July 2025).

This comparative analysis underscores the territorial inequalities in service provision and institutional responsiveness within Beira. It reveals how location, infrastructure condition, and community organisation shape the lived experiences of urban water and sanitation. These differences highlight the need for context-specific interventions that move beyond generic, city-wide approaches. For example, Chipangara may require emergency infrastructure renewal and consumer protection mechanisms. Ponta Gêa presents an opportunity to scale up community-led water management models, while Macuti demands stronger integration into climate adaptation plans, particularly for sanitation and drainage.

These territorial disparities mirror broader patterns of intra-urban inequality across African cities, highlighting the need for spatially differentiated WASH strategies [].

4.7. Integrating the Five Dimensions: Towards Systemic Reform

The five dimensions identified are not isolated but mutually reinforcing. Weak governance undermines infrastructure maintenance; poor maintenance increases costs and strains finances; limited financial resources hinder resilience measures; and the marginalisation of communities reduces accountability and responsiveness.

What emerges is a picture of systemic vulnerability, where partial reforms are unlikely to succeed unless pursued holistically. For Beira, this means that clarifying mandates, embedding maintenance systems, formalising community roles, mainstreaming climate adaptation, and ensuring transparent financial management must be advanced together.

Recent policy frameworks suggest that integrating WASH into city-wide climate action plans and budgeting processes is not only possible but increasingly necessary to ensure long-term sustainability [].

4.8. Contribution to Knowledge and Policy Relevance

This study advances debates on urban WASH governance in three ways:

- Historical depth: By highlighting the colonial legacies that continue to shape institutional fragmentation, it extends analyses that often treat governance challenges as contemporary administrative issues [].

- Everyday perspective: By triangulating policy documents with the voices of community leaders, it bridges the gap between official frameworks and lived experiences, often overlooked in Mozambique-focused research.

- Resilience integration: It demonstrates that resilience in secondary cities like Beira is still fragmented and donor-driven, reinforcing the need for systemic integration into planning.

For policy, the findings underscore that achieving SDG 6 in Beira requires more than legal reforms and donor projects. It demands institutional reforms that are historically informed, socially inclusive, financially transparent, and climate sensitive.

While much of the literature has focused on capital cities, this study offers a unique perspective by centreing on Beira, a strategically located mid-sized coastal city. It contributes to the emerging recognition of secondary cities as innovation hubs for climate adaptation and urban governance, positioning Beira as a strategic frontier in the pursuit of SDG 6.

The analysis reveals that the five sustainability dimensions identified in this study are deeply interconnected rather than independent variables. Governance and institutional coordination form the foundation for effective infrastructure maintenance and financial planning, which together determine the reliability and adaptability of WASH services. Financial viability influences both the capacity for preventive maintenance and the responsiveness to climate shocks, while climate resilience depends on continuous investment and flexible management structures. At the same time, community participation operates as both a catalyst and a feedback mechanism, strengthening accountability and reinforcing adaptive governance. These interlinkages suggest that improving one dimension in isolation is unlikely to achieve systemic sustainability; instead, progress requires integrated reforms that recognise the mutually reinforcing relationships among governance, infrastructure, finance, resilience, and participation.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the sustainability of urban water and sanitation services in Beira, Mozambique, by combining a review of the national policy framework with the perspectives of institutional actors and community leaders. The findings revealed five interrelated dimensions shaping service sustainability: governance and institutional coordination, infrastructure robustness, community participation, climate resilience, and financial viability.

Although Mozambique has advanced progressive sectoral policies and has mobilised significant post-disaster investments, substantial implementation challenges persist in translating these frameworks into everyday practice. Institutional overlaps, fragile and reactive maintenance systems, under-recognised and under-resourced community structures, fragmented and donor-dependent climate adaptation, and financial fragility continue to undermine service reliability and resilience.

The study contributes to knowledge by highlighting the influence of historical legacies in shaping contemporary governance, demonstrating the value of community voices in identifying sustainability gaps, and situating Beira within broader debates on WASH resilience in climate-vulnerable African cities. It also reinforces the relevance of secondary cities as key sites for innovation in urban governance and climate-responsive service delivery.

From a policy perspective, five priorities emerge:

- Clarify institutional mandates and formalise inter-agency coordination through operational planning platforms, performance monitoring, and accountability frameworks.

- Embed preventive maintenance and infrastructure asset management into municipal and utility-level plans and budgets, supported by decentralised repair capacity.

- Recognise and strengthen community-based water committees as partners in service provision, including through legal recognition, training, and modest operational funding.

- Mainstream climate adaptation—including Nature-Based Solutions—into city-wide WASH strategies, with stable financing and alignment across infrastructure, housing, and environmental sectors.

- Enhance financial transparency and participatory tariff-setting to balance affordability with cost recovery, including clear reinvestment mechanisms to improve public trust.

By addressing these interconnected dimensions simultaneously, Beira can move closer to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6, while providing lessons for other African secondary cities facing similar challenges of urban growth, climate vulnerability, and institutional fragmentation.

In doing so, Beira not only illustrates systemic constraints but also offers entry points for context-specific, inclusive, and forward-looking reforms. As secondary cities navigate the twin pressures of climate risk and institutional fragility, Beira’s case offers critical lessons for building equitable, adaptive, and resilient urban service systems in Africa.

Future research should adopt mixed methods designs combining policy diagnostics with household surveys and spatial indicators to validate and generalise these findings across other secondary coastal cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.M.S.; methodology, M.M.S.; formal analysis, M.M.S.; investigation, M.M.S. and B.R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.M.S., A.V.F., J.C.G.L. and B.R.C.; supervision, A.V.F. and J.C.G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to Article 3(2) of Decree No. 36/2023, published in the Boletim da República, Series I, No. 81, of 27 April 2023 (Mozambique), which stipulates that only biomedical or interventional studies involving human biological material, medical procedures, or identifiable personal data require ethics committee approval. As this research is social, non-interventional, and anonymised, it does not fall within the mandatory scope of ethics committee review. Formal authorisations to conduct the fieldwork were obtained from the relevant local institutions and authorities prior to data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Institutional actors and community leaders were briefed on the study’s objectives, interview procedures, and confidentiality protocols, and gave verbal or written consent before participating.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study consist of anonymised interview transcripts and summary tables. Due to ethical restrictions and the anonymity of participants, full transcripts cannot be made publicly available. However, extended summaries of all interviews are included in Appendix B and Appendix C of the manuscript. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of local institutions and community leaders in Beira, who generously contributed their time and insights to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AIAS | Administração de Infraestruturas de Água e Saneamento (Water and Sanitation Infrastructure Administration) |

| AdRC | Águas da Região Centro (Central Region Water Utility) |

| CMB | Conselho Municipal da Beira (Beira Municipal Council) |

| CRA | Conselho de Regulação de Águas (Water Regulatory Council) |

| DNAAS | Direção Nacional de Abastecimento de Água e Saneamento (National Directorate of Water Supply and Sanitation) |

| FIPAG | Fundo de Investimento e Património do Abastecimento de Água (Water Supply Investment and Asset Fund) |

| NBS | Nature-Based Solutions |

| ODS/SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SASB | Serviços de Água e Saneamento da Beira (Beira Water and Sanitation Services) |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Fund |

| WASH | Water, Sanitation and Hygiene |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

This appendix provides the full semi-structured interview guide used for data collection with institutional actors and community leaders in Beira, Mozambique. The guide was structured around five sustainability dimensions: governance and coordination, infrastructure and operations, participation and inclusion, climate resilience, and financial viability. Questions were adapted according to the role of the respondent, grouped here into institutional actors and community leaders, to preserve anonymity and reflect stratified sampling.

Appendix A.1. Institutional Actors (Water and Sanitation Governance Bodies)

Objective: Understand the institutional roles, strategies, and challenges in managing urban water and sanitation systems in Beira, including coordination, infrastructure, financing, and climate adaptation.

Main Questions:

- What is your institution’s role in managing or supporting urban water and/or sanitation services in Beira?

- How is coordination conducted with other relevant entities (e.g., AdRC, AIAS, the Municipality, DNAAS)?

- Are there existing plans or strategies to promote sustainability of water supply and/or urban drainage services?

- How does your institution address the challenges of service delivery in informal or peri-urban settlements?

- What are the key approaches for ensuring technical and financial sustainability of water and sanitation infrastructure?

- How are maintenance and rehabilitation projects planned and financed?

- Are communities involved in decision-making or implementation of water-related projects?

- What are the observed impacts of climate-related events (e.g., cyclones, floods) on your operations?

- What are the main challenges and opportunities for achieving long-term sustainability in Beira, including in neighbourhoods like Ponta Gêa?

Appendix A.2. Community Leaders/Neighbourhood Councils (Peri-Urban and Informal Zones)

Objective: Understand community perceptions on water access, service quality, institutional support, and climate vulnerability.

Main Questions:

- What are the main problems related to water access in your neighbourhood?

- Are there formally managed water points? Who is responsible for their maintenance?

- Is there any collaboration with institutions such as AdRC, AIAS, or the Municipality?

- Does the population participate in decisions about water or sanitation infrastructure?

- What are your priorities for improving local water and sanitation services?

- How do you understand the concept of “sustainability” in relation to water access?

- What are the main challenges and opportunities for improving WASH services in your neighbourhood and in Beira more broadly?

Appendix B. Summaries of Institutional Actor Interviews

Appendix B.1. SASB—Serviços de Água e Saneamento da Beira (Beira Water and Sanitation Services)—(June 2025)

The SASB representative highlighted the municipality’s pivotal role in sanitation, drainage, and regulation, noting its leadership in faecal sludge management and urban resilience planning. Coordination with AdRC, AIAS, FIPAG, and DNAAS is frequent, especially in the context of post-cyclone recovery efforts. Strategic frameworks include the Beira Master Plan 2035 and the Municipal Recovery and Resilience Plan, which emphasise integrated infrastructure rehabilitation and climate-proofing.

The official underscored that sustainability depends on three pillars: (i) institutional clarity and stronger municipal authority, (ii) financial viability of services, and (iii) active community involvement. The interview stressed the strain of unplanned urban growth, particularly the expansion of informal neighbourhoods with low WASH coverage, which places additional pressure on limited municipal resources. Equity was a central concern: wealthier households often have better service, while the urban poor face disproportionate risks from flooding and lack of sanitation.

Despite these constraints, the representative identified opportunities in mobilising international donor support, expanding community-level participatory platforms, and reinforcing the municipality’s regulatory powers. They pointed out that ongoing investments in drainage and coastal protection could serve as a basis for mainstreaming resilience across all WASH planning.

Appendix B.2. AIAS—Administração de Infraestruturas de Água e Saneamento (Water and Sanitation In-Frastructure Administration)—(June 2025)

The AIAS representative explained that the agency is responsible for planning, developing, and maintaining large-scale water and sanitation infrastructure, often in collaboration with international partners. They stressed that while national laws provide a clear mandate, coordination at the municipal level is still weak, with overlapping responsibilities between AIAS, AdRC, and the Municipality.

From their perspective, sustainability means ensuring that infrastructure investments are not limited to construction but include long-term maintenance systems. A major bottleneck is financial dependency: many projects are donor-funded, and municipalities struggle to sustain them once external support ends. The representative recognised that the post-Idai reconstruction provided opportunities to upgrade systems but admitted that resilience integration was still project-based and lacked systematic planning.

Challenges include rapid population growth in Beira, vulnerability to cyclones, and insufficient local technical capacity. Opportunities identified were increased donor interest in climate-resilient infrastructure, the drafting of the new Water and Sanitation Law, and the potential to formalise community roles in maintenance and monitoring.

Appendix B.3. AdRC—Águas da Região Centro (Central Region Water Utility)—(June 2025)

AdRC’s representative described their role as the main operator for water supply in Beira, acting under delegated management from FIPAG. They outlined key services: managing treatment plants, distribution networks, and customer billing. The interview highlighted improvements in supply capacity yet admitted to persistent service interruptions caused by ageing pipelines, storm damage, and electricity shortages affecting pumping stations.

Sustainability was defined as the ability to provide reliable, continuous supply while maintaining financial solvency. However, the representative acknowledged that customer trust is low due to cases of billing without supply, slow repairs, and lack of transparency. Coordination with AIAS, SASB, and the Municipality was described as “functional but inconsistent,” often depending on project-specific arrangements rather than long-term structures.

Main challenges included high operational costs, limited cost recovery from tariffs, and weak enforcement of payment. The official stressed the need for tariff reforms coupled with visible service improvements, investment in preventive maintenance, and stronger regulatory oversight by CRA. They also noted opportunities linked to international financing (World Bank, KfW, Invest International) and the expansion of smart metering technologies to improve efficiency and trust.

Appendix C. Summaries of Community Leader Interviews

Appendix C.1. Bairro Chipangara (July 2025)

The community leader in Chipangara described serious water access challenges that have persisted for over a year in some parts of the neighbourhood. Several households reported being billed despite not receiving water, creating a sense of injustice and eroding trust in service providers. Infrastructure is visibly deteriorated, with frequent pipe bursts and leakages. Collaboration with institutional actors such as AdRC, AIAS, and the Municipality was acknowledged, but the leader noted that responses are often slow and insufficient, leaving residents to rely on unsafe sources or informal vendors.

The leader emphasised that true sustainability means not only expanding the network but ensuring continuous, affordable, and reliable service. For Chipangara, community participation is considered weak: committees exist but are under-resourced and lack institutional support. Specific priorities highlighted included the rehabilitation of distribution pipelines, installation of new safe water points, and upgrading of drainage to mitigate frequent floods. The community also expressed concern that climate-related events such as cyclones repeatedly damage already fragile infrastructure. Despite these challenges, the leader pointed to opportunities, including ongoing municipal requalification programmes, potential partnerships with NGOs, and the use of technologies such as smart water metres to improve transparency.

Appendix C.2. Bairro Ponta Gêa (July 2025)

The community leader in Ponta Gêa reported better service coverage compared to peripheral bairros, though the area still experiences intermittent cuts, irregular pressure, and occasional failures in sanitation systems. The neighbourhood has a history of community management of fountain stands, with committees formally recognised by FIPAG and functioning in partnership with local authorities. This has fostered relatively strong coordination with AdRC, AIAS, and the Municipality, including consultations on resettlement processes and integration in the Beira Master Plan 2035.

The leader defined sustainability as the combination of resilient infrastructure, affordability, and participatory governance. Community members are generally more satisfied than in other bairros but remain concerned about climate vulnerability, particularly flooding and storm surges that disrupt supply lines. The restoration of the Chiveve River and green infrastructure projects were seen as positive examples of adaptation, though maintenance remains a concern. Key challenges identified were ageing infrastructure, financial limitations to expand services, and dependence on external funding. On the other hand, opportunities include leveraging donor support, consolidating the master plan vision, and scaling up successful participatory management experiences from Ponta Gêa to other bairros.

Appendix C.3. Bairro Macuti (July 2025)

The community leader in Macuti reported that water and sanitation services are highly unreliable, with long supply interruptions, weak drainage, and high exposure to flooding. Residents often rely on informal vendors and unsafe sources, which increases household costs and health risks. The leader pointed out that although infrastructure exists, it is poorly maintained and quickly deteriorates after cyclones.

Sustainability, from their perspective, means continuous, safe, and affordable access, with clear accountability from institutions. They criticised the limited visibility of community committees, which are often excluded from decision-making. Key challenges include ageing infrastructure, recurrent flooding, and lack of responsiveness from service providers.

On the positive side, opportunities include community willingness to collaborate, ongoing donor-funded projects, and the potential to integrate green infrastructure (such as mangrove restoration and flood-buffer zones) into the neighbourhood. The leader expressed hope that the Beira Master Plan could bring more inclusive and resilient planning to Macuti if properly implemented.

References

- United Nations General Assembly. The Human Right to Water and Sanitation-Resolution Adopted by the UN General Assembly [A/RES/64/292]; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/687002?v=pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Adams, E.A.; Zulu, L.C. Participants or Customers in Water Governance? Community-Public Partnerships for Peri-Urban Water Supply. Geoforum 2015, 65, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitonge, H.; Mokoena, A.; Kongo, M. Water and Sanitation Inequality in Africa: Challenges for SDG 6. In Africa and the Sustainable Development Goals; Ramutsindela, M., Mickler, D., Eds.; Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlongwa, N.; Nkomo, S.L.; Desai, S.A. Barriers to Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Mini Review. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2024, 14, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseole, N.P.; Mindu, T.; Kalinda, C.; Chimbari, M.J. Barriers and Facilitators to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) Practices in Southern Africa: A Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF; WHO. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2022: Special Focus on Gender; DNAAS: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Direção Nacional de Abastecimento de Água e Saneamento (DNAAS). Relatório Anual Do Setor de Água e Saneamento 2023–2024 (Annual Report of the Water and Sanitation Sector 2023–2024); Boletim da República: Maputo, Mozambique, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Dados Preliminares Do Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2023 (Preliminary Data from the 2023 Demographic and Health Survey); Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE): Maputo, Mozambique, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Assembleia da República. Lei n.o 16/91, de 3 de Agosto. Aprova a Lei de Águas. Boletim Da República, I Série, 31; Boletim da República: Maputo, Mozambique, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Conselho de Ministros de Moçambique. Resolução n.o 42/2016, de 30 de Dezembro. Aprova a Política de Águas. Boletim Da República, I Série, 156; Boletim da República: Maputo, Mozambique, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nhaurire, A.; Capurchande, R. The Sustainability of Water Access Services in Mozambique: From Policy to Practice. Sci. Technol. Public Policy 2025, 9, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, J. Maintaining a City against Nature: Climate Adaptation in Beira. Build. Cities 2024, 5, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C.; McCordic, C.; Doberstein, B. The Compounding Impacts of Cyclone Idai and Their Implications for Urban Inequality. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 86, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.M.; Ferreira, A.V.; Lanzinha, J.C.G. Colonial Moorings on Spatial Planning of Mozambique. Cities 2022, 124, 103619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herslund, L.B.; Jalayer, F.; Jean-Baptiste, N.; Jørgensen, G.; Kabisch, S.; Kombe, W.; Lindley, S.; Nyed, P.K.; Pauleit, S.; Printz, A.; et al. A Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Urban Vulnerability to Climate Change in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, L. The Urban Governance of Climate Change Adaptation in Least-Developed African Countries and in Small Cities: The Engagement of Local Decision-Makers in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, and Karonga, Malawi. Clim. Dev. 2020, 12, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishoge, O.K. Challenges Facing Sustainable Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Achievement in Urban Areas in Sub-Saharan Africa. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.A.; Sambu, D.; Smiley, S.L. Urban Water Supply in Sub-Saharan Africa: Historical and Emerging Policies and Institutional Arrangements. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2019, 35, 240–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dickin, S.; Bisung, E.; Nansi, J.; Charles, K. Empowerment in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Index. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, Å.; Wamsler, C. What Does Resilience Mean for Urban Water Services? Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozambique: Location Map (2025)|OCHA. Available online: https://www.unocha.org/publications/map/mozambique/mozambique-location-map-2025 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Byl, W.; Carter, R.C. An Investigation of Private Operator Models for the Management of Rural Water Supply in Sub-Saharan Africa. Waterlines 2018, 37, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiderska, K.; Roe, D.; Siegele, L.; Grieg-Gran, M. The Governance of Nature and the Nature of Governance: Policy That Works for Biodiversity and Livelihoods; Biodiversity and Livelihoods Issue Paper; IIED: London, UK, 2008; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985; ISBN 9780803924314. [Google Scholar]

- Girotto, C.D.; Behzadian, K.; Musah, A.; Chen, A.S.; Djordjević, S.; Nichols, G.; Campos, L.C. Analysis of Environmental Factors Influencing Endemic Cholera Risks in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, A.L.; Carden, K.; Teta, C.; Wågsæther, K. Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Vulnerability among Rural Areas and Small Towns in South Africa: Exploring the Role of Climate Change, Marginalization, and Inequality. Water 2021, 13, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madon, S.; Malecela, M.N.; Mashoto, K.; Donohue, R.; Mubyazi, G.; Michael, E. The Role of Community Participation for Sustainable Integrated Neglected Tropical Diseases and Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Intervention Programs: A Pilot Project in Tanzania. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 202, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.M.; Ferreira, A.V.; Lanzinha, J.C.G.G. The Possibilities of Capturing Rainwater and Reducing the Impact of Floods: A Proposal for the City of Beira, Mozambique. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiribou, R.; Djene, S.; Bedadi, B.; Ntirenganya, E.; Ndemere, J.; Dimobe, K. Urban Climate Resilience in Africa: A Review of Nature-Based Solution in African Cities’ Adaptation Plans. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanga, R.A.; Wang, Y.; Ayambire, R.A.; Wang, C.; Xu, M.; Li, J. Sister City Partnerships and Sustainable Development in Emerging Cities: Empirical Cases from Ghana and Tanzania. Habitat. Int. 2024, 154, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azunre, G.A.; Azerigyik, R.A.; Amponsah, O.; Kpeebi, Y. The Jugaad Urbanism-Sustainable Circular Cities Nexus: Insights from Sub-Saharan Africa’s Informal Settlements. Habitat. Int. 2025, 158, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, L.; Hofmann, P.; Srikissoon, N.; Campos, L.C.; Mbatha, S.; Lakhanpaul, M.; Mabeer, V.; Steenmans, I.; Parikh, P. Localisation of Links between Sanitation and the Sustainable Development Goals to Inform Municipal Policy in EThekwini Municipality, South Africa. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 2, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Bhattarai, T.N.; Acharya, G.; Timalsina, H.; Marks, S.J.; Uprety, S.; Paudel, S.R. Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene of Nepal: Status, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACS ES&T Water 2023, 3, 1429–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Qiu, H.; Xu, T. Towards Sustainable Urban Water Management: An Ecological Compensation Framework for Sponge Cities. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).