Abstract

Identifying the environmental and social factors that influence crime is crucial for effective crime prevention and for building safer cities. Boundary areas are often neglected, despite being hotspots for criminal activity. However, previous studies have primarily focused on physical boundaries, with insufficient attention paid to social boundaries shaped by factors such as population composition and socioeconomic disparities. Additionally, existing research methods remain limited in scope, with models that struggle to capture the nonlinear and complex nature of these relationships. This study proposes a comprehensive approach by measuring both multidimensional physical and social boundaries within urban environments. Using machine learning models, we present three main findings: urban boundaries are strong predictors of crime; boundary variables show stronger correlations with crime than intra-area variables; and both social and physical boundaries warrant equal attention. These findings suggest that governments should enhance problem-oriented policing at boundary hotspots in urban boundary areas while also promoting social integration to address the root causes of crime.

1. Introduction

In the context of rapid urbanization, crime reduction has become a core objective for achieving safe, stable, and sustainable urban governance. Existing studies have shown that criminal behavior is rarely randomly distributed. Instead, it is often closely associated with specific urban environments [1]. Therefore, identifying spatial environments that are more prone to crime is crucial for optimizing police deployment and enhancing urban safety [2]. In this regard, urban boundaries have been recognized as spatial zones where crime is more likely to occur [3,4]. These boundaries can be broadly categorized into physical boundaries and social boundaries. Physical boundaries refer to areas where there is a significant transformation in the built environment, such as highways, rivers, and railways. These areas often suffer from poor visibility, limited surveillance, and unstable pedestrian flows, which in turn increase anonymity and the opportunity for criminal activity [5]. Social boundaries stem from divisions between social groups, such as stark income disparities or ethnic segregation, that create intangible lines of separation. These divisions often result in low levels of social cohesion, which may trigger latent conflict and weaken informal social control over criminal behavior [3,4].

While the relationship between physical boundaries and crime has been relatively well-documented, research on social boundaries has primarily focused on racial boundaries, with limited attention given to how multidimensional social boundaries may influence crime patterns. For instance, previous studies have shown that areas near physical boundaries, such as highways, rivers, and park boundaries, tend to exhibit significantly higher crime rates compared to other urban areas, and may even become spatial hubs for illicit markets such as drug trafficking [6,7,8]. In comparison, studies on social boundaries have largely identified divides based on race or home values, finding elevated rates of violent and property crimes in these areas [3,4]. However, these studies often adopt a narrow definition of “social boundaries,” overlooking the broader and more nuanced conceptualizations emphasized in sociological perspectives.

Lamont & Molnár conceptualize social boundaries as the objectified forms of social differences, manifested through the unequal distribution of resources and opportunities [9]. Boundary intensity reflects the degree of spatial inequality in four types of social boundaries, often characterized by the measurable differences in social attributes (such as race) between the two sides of the boundary [3]. Beyond race, factors such as social class, education, employment, and knowledge structures can also constitute social boundaries. These structural differences often result in sharp discontinuities between communities in terms of residential conditions, economic resources, and social capital, ultimately contributing to spatial social segregation [4], which may, in turn, create conditions conducive to crime. This issue is particularly salient in Global South cities, where urban areas face more complex social structures and governance challenges. Compared to racial divisions, socioeconomic inequalities such as income disparities, differences in educational attainment, and property values are more pronounced. Therefore, broadening the conceptualization of social boundaries beyond racial boundaries and employing boundary strength to quantify the degree of this inequality can help generate more generalizable conclusions and enhance both the explanatory power of theory and the applicability of policy recommendations.

Moreover, existing research also faces certain methodological limitations. Most current empirical studies rely on traditional statistical approaches, such as distance decay models and negative binomial regression. For example, Brantingham et al. identified gang territory boundaries through spatial features and employed Lotka–Volterra competition model to reveal the spatial patterns of violent crime [10]. Similarly, Song et al. constructed buffer zones around actual boundaries to examine whether crime becomes more concentrated near highways and land-use boundaries. However, traditional regression methods often struggle to capture the potential non-linearities and complex interaction effects that may exist between boundary-related variables and crime outcomes [8,11].

Previous studies have shown that the relationships between various environmental and social factors and crime are often complex and non-linear. As such, models capable of capturing such complexities may be more suitable for investigating the relationship between urban boundaries and crime. For instance, Kim and Lee found that the effects of built environment and street network variables on crime vary in both direction and magnitude across different value ranges [12]. Similarly, the relationship between home value and crime rates does not follow a simple linear pattern but may shift across phases of facilitation, suppression, or neutrality. Buonanno and Leonida further argued that education influences criminal behavior through mechanisms such as social cognition and opportunity costs, resulting in a more intricate relationship between the two [13]. Moreover, Kim and Hipp identified collinearity and interaction effects between boundary variables and the internal characteristics of the areas they demarcate, which leads to challenges that traditional regression models often fail to address [3]. Given the non-linearity and coupling inherent in such problem structures, machine learning (ML) models, which do not require predefined assumptions about variable relationships, offer a significant advantage. Algorithms such as K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), and Adaboosted Decision Tree (AdaBoost-DT) are particularly effective in capturing non-linear associations and complex feature interactions through distance-based classification, hierarchical partitioning, and ensemble learning mechanisms [14]. Their ability to automatically detect non-linear patterns and high-order interactions makes them particularly well-suited to modeling the complex interplay of urban spatial structures and social dynamics [12,15,16]. Therefore, ML provides valuable methodological expansion and theoretical advancement for exploring the links between urban boundaries and crime.

In summary, existing research reveals two major gaps: (1) The measurement of social boundaries remains overly narrow, lacking a systematic integration and spatial representation of multidimensional social disparities such as income, home value, education, and employment. This limits the ability to capture the complex mechanisms of social segregation within cities. (2) The methodological approaches employed are largely conventional and limited in scope, making it difficult to detect potential non-linear relationships between variables and to address collinearity between boundary and internal variables. These limitations constrain a deeper understanding of the relationship between urban boundaries and crime, as well as the identification of underlying mechanisms.

To address the aforementioned research gaps, this study utilizes open-access high precision data to systematically construct a set of multidimensional social boundary indicators, including GDP, home value, salary, and education level, alongside physical boundary indicators, in order to comprehensively characterize urban boundaries within cities. By incorporating a range of ML models, the study investigates three key questions: (1) Are urban boundaries effective crime predictors? (2) Are boundary areas more prone to crime than interior zones? Based on the above theories, it is hypothesized that boundary areas tend to exhibit higher theft risks due to weaker social cohesion and greater spatial anonymity. (3) Which has a greater impact on crime, physical boundaries or social boundaries? The analysis focuses on theft, one of the most common types of urban crime, given its extensive data availability, broad spatial distribution, and significant socioeconomic consequences [17,18]. This study not only contributes to the theoretical development of boundary concepts in urban crime research but also provides empirical evidence and methodological tools to support targeted crime prevention and urban spatial planning.

2. Data and Methods

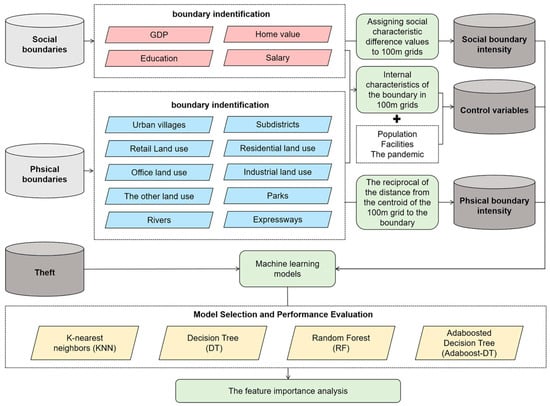

Figure 1 concludes the whole flow of this study. This study first calculates the intensity of social and physical boundaries as independent variables, incorporating their internal characteristics and common predictors of theft as control variables. Machine learning models are then applied to analyze the impact of different boundary intensities on theft, using feature importance to interpret their relative influence.

Figure 1.

Research flowchart.

2.1. Study Area

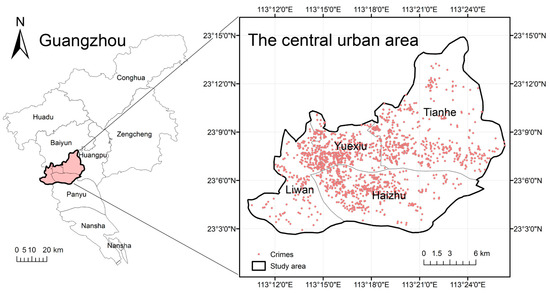

As shown in Figure 2, the study area is the central urban area of Guangzhou, China, with an area of 350 km2, and a population of 10.3 million. It comprises 4 districts, 79 subdistricts. With a developed economy, concentrated population, and relatively high crime rates, this area is a representative area of crime-related research [19,20].

Figure 2.

Study area and crime locations.

The study unit of this article is a spatial grid with a 100 m × 100 m resolution. Grids with this resolution are more spatially accurate and homogeneous in size and shape. They can be adapted to most types of open-source data and make the results of measurements better for high-precision crime prediction [12,21]. In this research, grids over 50% covered by water, forest, or mountain were excluded as the probability of crime is negligible due to lack of human activity. The final analysis included 35,196 grids in total.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this research is the number of thefts in a 100 m × 100 m grid. Theft data were assembled from first-instance judgements issued between 2019 and 2021, which were available on China Judgements Online (https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/, accessed on 1 May 2023). When obtaining the exact geo-location of each observation, duplicate items (i.e., stealing multiple items at once) were excluded. Crimes on public transport were excluded only when judgements did not provide specific station or stop information, but instead described the location generically as “on metro line 3” or “on bus route 15”. Because such descriptions refer to entire routes that extend for many kilometers, they cannot be reliably geocoded to a single grid cell, whereas incidents with explicit station names were retained in the dataset. In this study, crime counts are coded as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5, indicating that within each 100 m × 100 m grid there were 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or at least 5 crimes, respectively. In other words, any grid with a count of 5 or more is recorded as 5, to avoid very sparse categories that the model would struggle to predict reliably. To validate the representativeness of judicial records for mapping theft hotspots, we conducted a qualitative comparison with police call out data. Given the confidential nature of police call out data, which are not publicly disclosed, we relied on an hotspot map generated from police call out records by the Guangzhou Municipal Public Security Bureau in existing literature [22]. This map covers Haizhu District within our study area, and a qualitative comparison shows that the spatial pattern of theft hotspots based on first instance judicial records during 2019 to 2021 closely matches the hotspots identified from police call outs, particularly around major commercial and transport hubs. This comparison, presented in Supplementary Figure S1, supports the validity of using judicial records to represent the spatial distribution of theft hotspots.

2.2.2. Social Boundaries

The independent variable in this study is boundary intensity, which includes both social and physical boundaries. Among them, social boundary intensity reflects the degree of spatial inequality in four types of social boundaries: economy, housing, occupation, and knowledge. In this study, the data of these social characteristics are collected and statistically analyzed within the grid, and the boundary intensity is defined by calculating the size of the numerical difference in social characteristics between adjacent grids, which can reflect the degree of spatial inequality on both sides of the boundary.

This study collects multi-source big data to quantify social characteristics. First, a GDP grid dataset based on grid-level decomposition of multivariate data predictions with 1000 m accuracy in 2020 [23] was used to measure the economic level. Second, Anjuke (https://guangzhou.anjuke.com/, accessed on 1 May 2023), a popular real estate trading platform in China, was used to obtain home listing prices for 31,297 data points in May of each year from 2019 through 2021 to measure area home value. Last, the job posting data on the recruiting website 58 Tongcheng (https://www.58.com/job/, accessed on 1 May 2023) from February to March 2023 was collected. The minimum educational requirement of a job was utilized to measure the workforce’s education level, while the minimum salary was employed to indicate the salary level.

To standardize the measurement of social boundary intensity and assign values to a 100 m × 100 m grid, ensuring consistency with the unit of analysis used for the dependent variable, this study adopts a four-step measurement approach based on Kim and Hipp [3], as outlined below:

Step 1 Calculate the exact value of social characteristics. Since social boundaries are tend to appear between communities and neighborhoods, and in the construction of community groups in China, the size of the scale of a community group and its influence sphere is consistent with a 500 m × 500 m grid [24]. Therefore, this study summarizes the source data onto a 500 m × 500 m grid for statistical analysis. Since the GDP data is a 1000 m × 1000 m grid data, the GDP values within the 500 m × 500 m grid are obtained by dividing the values into four equal parts. The point data of housing, occupation and knowledge are aggregated to the 500 m × 500 m grid to calculate the average values of home value, salary and education level.

Step 2 Calculate the regional spatial differences in social characteristics to obtain the boundary intensity. To avoid scale effects arising from dimensional differences between indicators, all precise numerical values of social characteristics were standardized and converted into z-scores. Subsequently, boundary intensity was calculated, defined as the difference between the two sides of the divider of 500 × 500 m grids. The calculation formula is as follows:

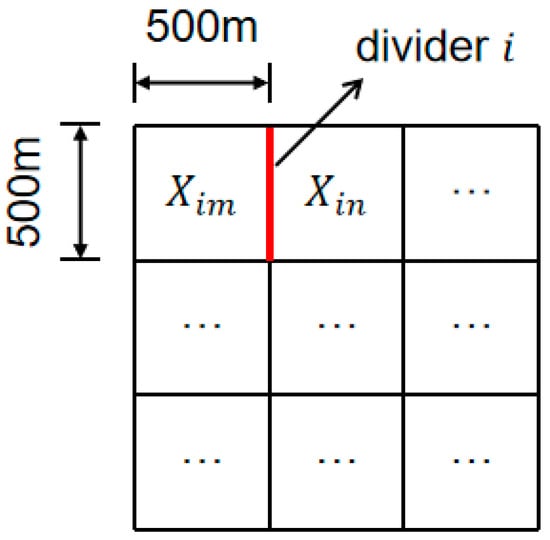

where represents the difference across the divider i of grids im and in and (see Figure 3) and refer to the standardized values of the given social characteristic of the grid im and in on two sides of divider i, respectively.

Figure 3.

The schematic diagram of ‘divider i’.

Step 3 The boundary intensity calculated in the 500 m × 500 m grids is directly assigned to the corresponding 100 m × 100 m grid it covers in order to integrate the physical boundary, the social boundary, and the number of crimes at the same scale. The 100 m × 100 m grids are strictly nested within the 500 m × 500 m grids (each 500 m grid consists of 5 × 5 sub-cells). Therefore, the boundary intensity of each 500 m divider was directly assigned to the corresponding 100 m cells it covers, without additional length-based weighting.

Step 4 Statistically analyze the boundary intensity to extract the social boundaries. Social boundaries are defined as the locations where boundary intensity values exceed a percentile threshold. To ensure comparability with physical boundaries, this study tested three representative thresholds (the 75th, 80th and 90th percentiles). The 75th percentile produced social boundaries whose total lengths (approximately 160–880 km across indicators) were comparable to those of the physical boundaries (approximately 140–830 km). The 80th percentile yielded moderately shorter boundaries (approximately 100–650 km) while preserving a very similar spatial pattern to the 75th percentile. Using the same RF modeling framework, applying the 80th percentile led to only modest changes in model performance, with ACC, F1, and AUC decreasing by 0.0267, 0.0249, and 0.0039, respectively, compared with 75th percentile. In contrast, the 90th percentile generated only very short boundary segments (45–70 km), which were too sparse to support robust spatial analysis. The 75th percentile was therefore selected as a balanced and interpretable threshold that provides both conceptual comparability and sufficient spatial coverage for subsequent modeling and factor analysis.

2.2.3. Physical Boundaries

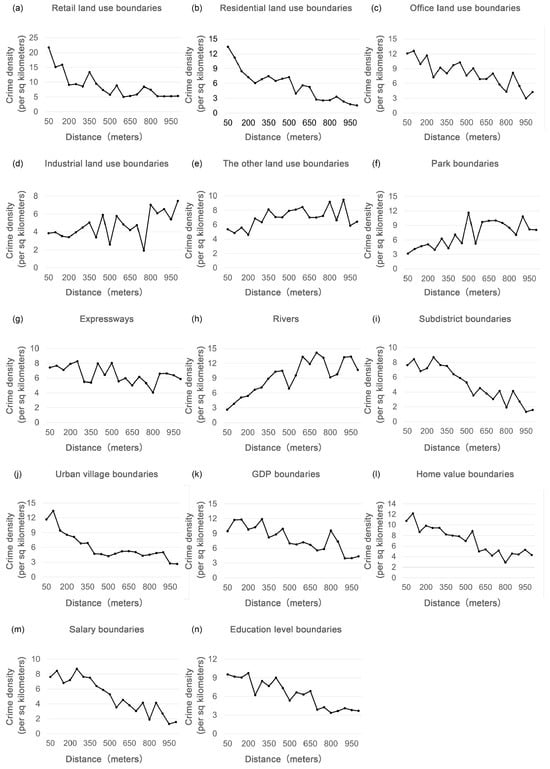

Common physical boundaries were also considered, including the boundaries of parks, expressways and rivers, subdistrict boundaries, land use boundaries and China’s unique urban village boundaries to examine the effects of these physical boundaries on crime [3,6]. The park boundaries can be obtained from the Area of Interest (AOI) data of the Baidu Map in 2022. And expressways and rivers can be determined using OpenStreetMap, with subdistrict boundaries retrieved from the National Center for Basic Geographic Information (NCBGI). Meanwhile, the 2018 open-source urban land use dataset based on the decoding of multi-source data was used to determine land use boundaries, and the basic unit of the data was the land plot, as they proposed [25]. 2018 is the closest year with high quality citywide land use data. Previous remote sensing studies indicate that land use patterns in Guangzhou change slowly at the municipal scale, with annual changes well below 1% of the total area, so using the 2018 map to approximate conditions in 2019 to 2021 is acceptable for this analysis [26]. urban village boundaries were extracted from Feng et al. [27] and then calibrated with the latest Baidu map satellite imagery to obtain the fine urban village boundaries. Referring to the practice of Kim and Hipp [3], land uses were divided into five categories. This study followed Kim and Hipp [6] and constructed the boundary variable as the reciprocal of the distance from the centroid of the grid to the boundary. Given the singularity of this function form as d approaches zero, we have set a minimum threshold of 1 for d. Thus, when d ≤ 1, the value of this variable is treated as 1 to avoid issues of infinity. This construction was consistent with our intensity measure of social boundaries below and reflected the distance decay effect in boundary crime studies [3,8]. Our results in Figure 4 demonstrated the rationality of this operation.

Figure 4.

Distance decay effect of crime on physical boundaries and social boundaries.

2.2.4. Control Variables

Established studies have shown that population, density of public facilities, and the pandemic all have great impact on crimes [12,28]. Therefore, this article takes these factors into account as control variables. Among them, the population data were obtained from the WorldPop2020 100 m resolution dataset for mainland China. The 2020 version was adopted because it is the only publicly available dataset with national coverage and fine resolution; population distribution generally remains stable over a short two–three year period, making it representative for 2019–2021. The density of various types of facilities (commercial, entertainment, and security facilities), namely, the number of facilities occupied per 100 people in the grid, was calculated using the Point of Interest (POI) data from Baidu Maps in Guangzhou in 2021. The 2021 dataset was selected due to incomplete POI records in 2019–2020 caused by the pandemic, ensuring more reliable classification of facilities. Data on CCTV density are not publicly released by security authorities for confidentiality reasons. However, the inclusion of security facility POIs (e.g., police stations and community patrol offices) partially captures the monitoring effect. A dummy variable was also included to account for the possible impact of COVID-19 during the sample period. The variable equals 1 if there were cases of the pandemic in the grid. The data were collected from the National Health Commission of China from April 2019 to December 2021.

Moreover, variables representing the internal characteristics of the boundary were introduced to distinguish the effects of the boundary itself from those of its internal properties. These included the respective percentages of each land use and urban village in the grid. Moreover, the 100 m × 100 m grid-level values of GDP, home value, salary, and education level were also taken in, which were simultaneously generated in the procedure of social boundary intensity measurement. All variables are listed below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary statistics and data sources of all variables.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. ML Models

ML models have been proven to fit well the non-linear relationship between multi-dimensional urban environment, socioeconomic characteristics, and crime [12,15,29]. Therefore, this study conducted ML models of boundary intensity on theft crimes. This study used four main ML multiple classification models: KNN, DT, RF, and Adaboost-DT, referring to Dev and Eden [30]. Before model training, we applied filter-based feature selection methods including ReliefF and Fisher score. ReliefF evaluates feature relevance by measuring how well a feature distinguishes between neighboring samples from different classes while remaining consistent within the same class [31]. Higher scores indicate stronger local discriminative ability. Fisher score ranks features based on the ratio of between-class variance to within-class variance [32]; a higher score reflects greater class separation. These two methods are suitable for multi-class classification problems. We averaged the rankings from both methods, and excluded the lowest-ranked variables to avoid introducing noise and ensure model robustness. To cope with the problem of imbalanced data on the dependent variable, we treat each ML model accordingly. SVMSMOTE was employed to oversample smaller proportions of data before using the KNN model. SVMSMOTE is a variant of the SMOTE algorithm that uses a support vector machine to identify borderline and hard-to-learn instances, and then generates synthetic samples in their neighborhood. This approach reduces the risk of producing noisy synthetic points far from the decision boundary, making it suitable for neighborhood-based classifiers such as KNN, where decision boundaries are highly sensitive to the local density of training samples [33,34]. The category weight adjustment was used for DT, RF, and Adaboost-DT. Class weighting assigns larger penalty values to misclassified minority classes by weighting the loss function inversely proportional to class frequency, without altering the sample distribution. This method is well-suited for ensemble models, since tree split criteria can naturally incorporate weights and handle class imbalance without duplicating or synthesizing data [35]. Table 2 reports the class distribution of crime counts before and after applying SVMSMOTE to the training data, showing how oversampling reshaped the distribution toward a more balanced structure. The resampled data is only applied in training folds. To mitigate spatial leakage, we applied GroupKFold for 5-fold, group-based cross-validation. The grouping key was the administrative subdistrict identifier (subdistrict_id), so that all 100 m × 100 m grid cells within the same subdistrict were always assigned to the same fold. In each iteration, 1 fold served as the test set and the remaining 4 folds formed the training set, ensuring that the same spatial group never appeared in both training and test sets. We then reported the mean and standard deviation of the performance metrics across the 5 iterations. Metrics are out of fold: for each of the k spatial folds, the model was trained on k − 1 folds and evaluated on the held fold. The study performed hyperparameter grid search to arrive at the optimal combination of hyperparameters.

Table 2.

Theft counts before and after SVMSMOTE.

2.3.2. Model Performance Evaluation

This study compares the performance of four ML models and selects the ML model with the highest accuracy for subsequent analysis. To represent the performance of the model, ACC (the accuracy) and AUC (area under the ROC curve) were calculated. A model is considered excellent performance when ACC and AUC are above 0.9 [36]. Specifically, ACC is calculated as follows:

where (true positive) and (true negative) are the number of pixels that are correctly classified and (false positive) and (false negative) are the numbers of pixels incorrectly classified [37]. Since the model was built based on unbalanced data, this study used several indicators to judge the performance of the model, including precision, recall, F1 score, and a classification matrix report. The closer the above metrics are to 1, the better the performance of the model.

2.3.3. The Feature Importance Analysis

In order to examine whether boundary effects are stronger than those of internal variables, we fitted three models using RF: an internal only model, a boundary only model, and a combined model including both sets of variables. To assess the significance of the differences between models, we used a paired bootstrap with B = 1000 resamples and computed the differences in performance (ΔACC, ΔF1, and ΔAUC). We report the mean differences and two sided bootstrap p values.

Finally, we employed a feature importance assessment method based on performance decay to explore the importance ranking of all variables in terms of their impact on criminal behavior [38]. Specifically, the degree of performance decay refers to the magnitude of the decrease in model performance metrics that occurs after disrupting the relationship between a feature and the target variable by randomly upsetting the value of the feature during model training. If a feature is significant to the model’s prediction, then randomly disrupting the value of that feature will result in a significant decrease in model performance. In this study, the number of times each variable was randomized to arrange the features was set to 30 times. Multiple permutations can quantify the importance of each feature more consistently and avoid misclassification due to chance.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Boundary Measurement

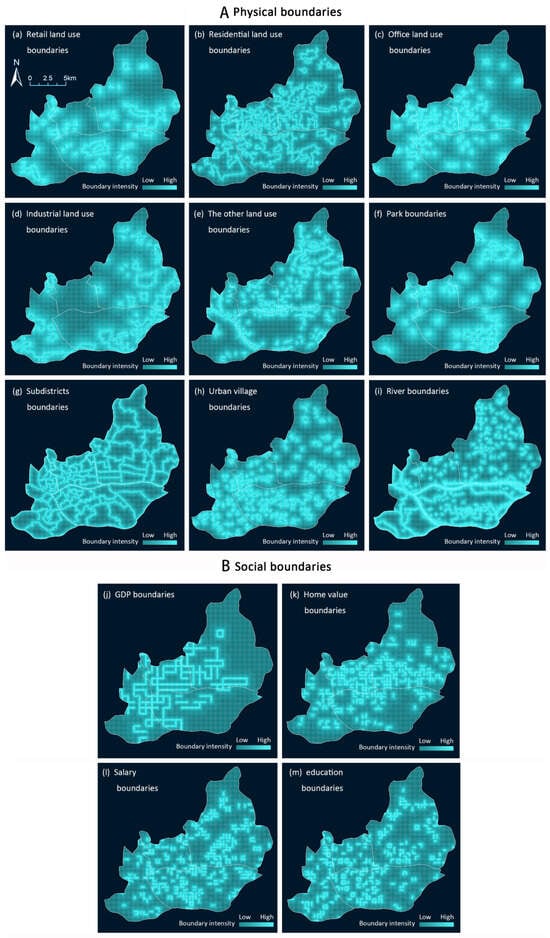

Figure 4 presents the spatial distribution of identified boundary features. Figure 4a–i illustrate the physical boundaries, which show considerable spatial variation across the study area. Retail land use boundaries are relatively sparse and primarily located in the southeastern and central zones, reflecting the concentration of commercial activity in core business areas. Residential and office land use boundaries are more widely distributed in central and western zones, with office areas exhibiting a smaller spatial extent but overlapping with residential zones. In contrast, industrial land use boundaries are mainly found at the urban periphery, especially in the eastern and southern sectors. Other key physical boundaries include rivers and mountains, such as the Pearl River, which marks inter-district divisions, and elevated terrain to the north, which serves as a natural edge. Park boundaries are concentrated around key ecological zones including mountain reserves and wetland belts. Subdistrict boundaries are densest in the central administrative core, while urban village boundaries cluster at the intersection of older urban areas and newly developed zones. Table 3 presents the results of the feature selection methods. Expressways ranked last among all variables. Among the bottom five features, only Percent office land use and Expressways consistently ranked below 20 in both ReliefF and Fisher Score. Given our research objective to compare the effects of spatial boundaries and their corresponding internal characteristics, we retained Percent office land use. Therefore, only Expressways was excluded during the feature selection process.

Table 3.

Results of ReliefF and Fisher score.

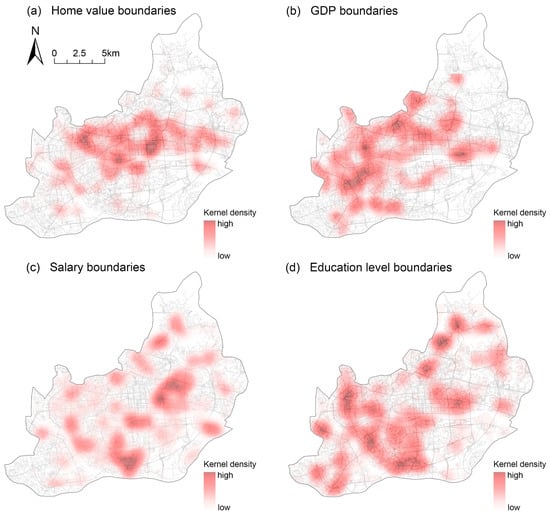

Figure 5B(j–m) display the spatial distribution of social boundaries, with further clarification provided through kernel density analysis in Figure 6. In this figure, darker shading indicates a higher concentration of boundaries, signifying areas with greater socio-spatial discontinuities. These hotspots reflect zones of pronounced segregation in terms of economic status, home value, occupational structure, and educational attainment. While all four dimensions exhibit multiple high-density clusters, home value boundaries are more centrally concentrated, whereas boundaries based on GDP, occupation, and education show a more dispersed spatial pattern. The identified hotspots were cross-referenced with actual urban locations to ensure consistency with real-world urban spatial structures.

Figure 5.

Results of the boundary measurement.

Figure 6.

KDE for multiple social boundaries.

Figure 6 illustrates the spatial clustering of different forms of social inequality in central Guangzhou. Figure 6a highlights areas of pronounced home price disparities, primarily located in interstitial zones between commercial housing estates, state-owned unit compounds, and urban villages. These transitional spaces often exhibit strong income-based residential segregation and are associated with elevated levels of social tension and criminal activity [39]. Figure 6b shows concentrations of economic inequality, especially around the interface of Guangzhou’s old and new central business districts, where GDP boundaries separate vibrant commercial districts from adjacent low-income neighborhoods. Such zones of social friction may intensify conflicts, particularly between residents and non-local visitors [40]. Figure 6c identifies salary boundaries, with the most prominent cluster in a mixed-use industrial area, where traditional light manufacturing zones inhabited by low- to middle-income workers coexist with emerging high-tech industrial parks attracting high-skilled professionals [41]. Finally, Figure 6d reveals education-level boundaries, largely situated near university precincts, reflecting disparities between academic staff and service-sector workers. Overall, the observed spatial patterns align with known socio-economic divides in Guangzhou and lend empirical support to the validity of the social boundary measurements.

3.2. ML Model Analysis Results

The results of the analysis using the four ML models tested are shown in Table 4. All assessment metrics are listed for each model. The results show that most models have high accuracy, and RF performs the best. For accuracy, KNN and RF are above 0.95, DT is about 0.94, while Adaboost-DT is about 0.72 and does not reach 0.85. However, for the PR AUC, all four models are ≥0.80 (RF is the highest). For precision and F1, RF is also the best performing model, with macro Precision ≈ 0.91 and macro F1 ≈ 0.90. Therefore, by combining the performance of each indicator, this study concludes that RF is the most appropriate model to analyze the influencing factors of theft crimes, not only the overall performance of the model is excellent, but also it can effectively deal with the unbalanced data.

Table 4.

Comparison of ML models for theft prediction.

3.3. Impact of Multiple Boundary Variables on Crime

The results of assessing the impact of boundary variables on crime in relation to their internal variables show that boundaries are more strongly correlated with the occurrence of crime. As reported in Table 5, the boundary only model outperforms the internal only model across all metrics. Table 6 further confirms this with nested, paired bootstrap comparisons. Relative to the internal only model, the boundary only model increases accuracy by 0.0657, F1 by 0.0674, and AUC by 0.0167, all with p_bootstrap < 0.001. The combined model performs best overall, improving on the boundary only model by 0.0915 in accuracy, 0.0089 in F1, and 0.0056 in AUC, all with p_bootstrap < 0.001. These consistent and statistically significant gains indicate that incorporating boundary variables is appropriate and adds complementary information beyond internal variables. In our setting, boundary variables are stronger predictors of theft crime than internal variables.

Table 5.

Comparison of model performance across boundary model, internal model and combined model (mean ± std).

Table 6.

Nested comparisons and significance (paired bootstrap, b = 1000).

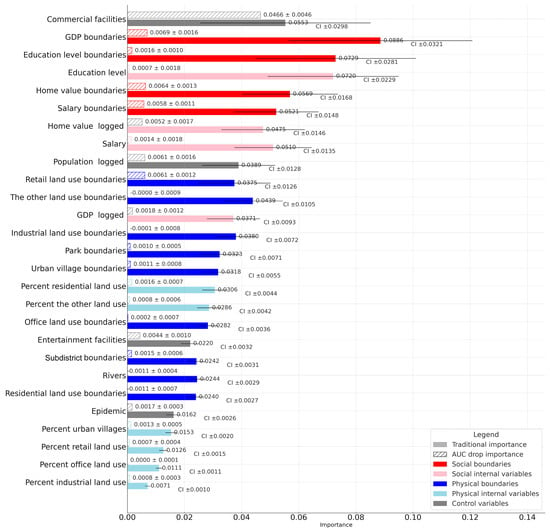

Figure 7 shows the feature importance estimates from the RF model. Indicators are displayed in order of the composite rank, that is, percentile ranks are computed separately for the traditional importance and the AUC drop importance, then averaged to obtain a composite score, from which the composite rank is derived. Variables are colour coded by type to visually illustrate their relative impact on theft crime. The results show that the top 5 variables are commercial facilities, GDP boundaries, education level boundaries, education level, and home value boundaries, indicating that commerce and education exert the strongest influence on crime prediction. GDP boundaries and education level boundaries rank 2nd and 3rd, respectively, which emphasizes the importance of boundaries. In addition, except for residential land use boundaries, all boundaries rank above their corresponding internal variables. This suggests that boundary variables generally contribute more to the prediction of theft than internal variables. Finally, social boundaries predict theft better than physical boundaries. GDP boundaries, education level boundaries, home value boundaries, and salary boundaries all rank within the top 6, whereas the physical boundaries fall between ranks 10 and 22. Additionally, the COVID-19 prevalence variable ranks only 23, indicating that pandemic-related factors play a negligible role in this specific crime type and context. Figure S1 also presents similar conclusions and demonstrates feature attribution consistency.

Figure 7.

The feature importance of the RF model. The lower solid bar shows the traditional importance, namely the feature importance computed by the random forest from the mean decrease in impurity when the feature is used for splits. Values are the mean over 30 repeats. Black error bars show the 95% CI of this mean. The upper hatched bar shows the AUC drop importance, in the same units, representing the decrease in model AUC when the feature is perturbed or removed. The mean and ± sd are labelled.

4. Discussion

4.1. Urban Boundaries as Strong Predictors of Crime Hotspots

This study provides compelling evidence that boundary variables are highly effective predictors of theft crime, as demonstrated by the outstanding performance of the ML models. According to routine activity theory, for a crime such as theft to occur, three conditions must converge: a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of capable guardianship (formal or informal) [42]. Boundary zones often interrupt spatial continuity: they may reduce line-of-sight, fragment pedestrian paths, decrease foot traffic, and weaken natural surveillance. In such fragmented environments, informal guardianship by passersby or residents is less effective, and visibility is lower, which raise the probability that the motivated offender and target will meet undetected [5]. Therefore, boundary zones inherently amplify situational opportunity for theft.

Accurate crime prediction is a cornerstone of effective urban safety management. High-precision crime forecasting enables law enforcement agencies to identify emerging hotspots, optimize resource allocation, and implement targeted interventions. The findings of this study reveal previously under-recognized theft hotspots at urban boundaries, including zones where administrative control is ambiguous or socio-economic transitions are sharp. These areas may lack adequate surveillance or routine monitoring, making them particularly susceptible to opportunistic crimes.

4.2. Boundary Zones Are More Vulnerable to Theft than Interior Areas

The boundary model outperforms the internal model across all evaluation metrics. Furthermore, feature importance rankings consistently show that boundary variables contribute more to crime prediction than their internal counterparts. These findings reinforce the argument that spatial discontinuities are key determinants of crime risk.

This finding aligns with the previous study [4], who observed that violent crimes are more frequent at racial boundaries compared to interior zones with similar demographic characteristics. However, this study extends that insight by demonstrating that heightened crime risks at boundaries are not limited to racial or ethnic divides, but are a more generalizable phenomenon across a variety of physical and social boundaries. Boundaries, whether based on home value, GDP, or salary, appear to fragment urban space in ways that increase the likelihood of criminal events.

From a social mechanism perspective, this can be framed through collective efficacy and informal social control theory. Sharp socioeconomic contrasts across adjacent areas tend to reduce trust, mutual ties, and residents’ willingness to intervene, thereby weakening informal oversight over deviant acts [43,44]. In boundary zones, the mix of transient populations, weak social cohesion, and ambiguous social belonging further inhibit neighborly surveillance or social intervention.

4.3. Social Boundaries Are More Important than Physical Boundaries to Urban Crime

The analysis of feature importance reveals that social boundaries are more significant predictors of theft crime than physical boundaries. While previous research has often emphasized the role of physical boundaries in shaping crime patterns [6,7,8,11], this study demonstrates that social boundaries are more important. Relying solely on physical features underestimates the complexity of urban spatial dynamics. The findings therefore call for a more integrative approach to crime prevention and urban planning. On the one hand, surveillance can be enhanced along social boundaries. Additional monitoring can comprehensively cover both pedestrian activity and vehicular access. Concurrently, improving lighting in concealed corners of boundary zones can reduce opportunities for crime. Furthermore, these boundaries offer insights for planning community patrol routes, enabling optimized coverage. On the other hand, to diminish disparities across social boundaries and enhance cohesion, the government should address economic inequality by mandating a proportion of affordable housing within commercial developments. This enables cohabitation of diverse income groups within the same neighborhood. Furthermore, rational planning for shared public amenities such as community parks, fitness facilities, and children’s playgrounds can foster interaction and integration among residents of different housing categories. Only through such comprehensive governance can policymakers effectively address the deep-seated social causes underlying urban security deficits.

4.4. Limitations

This study has certain research limitations. First, due to limitations in data availability, this study has not yet examined social boundary characteristics such as age, gender, migration status, or ethnicity. Should future research gain access to an increased amount of microdata, it will be possible to investigate the impact of these social boundary characteristics on crime. Secondly, as this study relies on publicly available online data, there are variations in the collection times of multiple data sources, such as recruitment data. However, this decision is primarily influenced by the impact of pandemic-related lockdowns on the recruitment market. Therefore, we opted for 2023 recruitment data instead of data from 2021 to 2022. To assess whether this choice affects our findings, we re-estimated the RF models using alternative thresholds of 3 and 5 postings per grid cell and compared the resulting feature importance rankings. Across these specifications, the overall ordering of indicators, combining traditional and AUC based importance, remains essentially unchanged and the key predictors identified in the main analysis continue to occupy the top positions. We further computed Spearman rank correlations of feature importance scores, which confirm high stability for the traditional importance measure, while the AUC-based importance becomes less stable under the strictest threshold. These additional results are reported in Supplementary Figures S3 and S4 and Table S1. Taken together, the analyses suggest that our feature rankings should be interpreted as reflecting predictive associations rather than strong causal effects, but they also indicate that our substantive conclusions are robust to alternative constructions of the recruitment variables and therefore provide a solid and policy relevant description of spatial patterns in theft risk. Collecting data at the same time period, under the assumption of no significant intervening events, would be more advantageous for this research. Thirdly, data on property prices and salaries from online platforms may disproportionately cover communities with high internet penetration and strong economic activity, leading to underrepresentation of low-income groups. Constrained by data availability, this study could not access administrative records at the estate or individual level (such as property registration details from housing authorities or social security contribution data) for point-to-point verification. Future research with access to higher-precision official microdata could further mitigate potential measurement errors and test the robustness of these conclusions. Moreover, future research may incorporate violent crimes such as robbery into its scope, offering significant insights into the mechanisms by which social boundaries facilitate different criminal activities. For instance, conducting empirical studies on specific boundary areas could both calibrate the findings of this paper and uncover the underlying causes. Finally, this study focuses exclusively on Guangzhou’s central urban districts, providing a technical framework for analyzing the impact of boundary spaces on theft offences. This methodology may be replicated in other cities to expand the sample size for this research.

5. Conclusions

Previous research has demonstrated that physical and social boundaries influence crime patterns. However, many important forms of social boundaries remain underexplored, and existing methods often fail to capture the non-linear relationships between urban boundaries and criminal behavior. To address these gaps, this study made full use of open-source big data to examine how inequalities in economic development, home values, occupation, and education shape social boundaries, drawing on their theoretical foundations in sociology. This study also measured the role of urban boundaries in crime prediction.

This study yielded three main findings: (1) Boundary variables are highly effective predictors of theft crime, with machine learning models incorporating these features achieving high accuracy and strong classification performance. They capture situational opportunities at urban boundary areas where visibility and movement are disrupted, consistent with routine activity theory. Including these features improves spatial precision, enabling resources to focus on boundary segments where modest environmental changes can reduce theft risk. (2) Theft risk is higher in boundary zones than in interior areas, with boundary variables showing greater influence than internal factors in crime modeling. Boundaries increase offender anonymity by thinning everyday social contact and weakening eyes on the street, which reduces informal guardianship and raises the probability of undetected encounters between offenders and targets. Recognizing this mechanism places greater emphasis on designing and managing boundary spaces to restore natural surveillance and reduce anonymity. (3) Social boundaries play more significant roles in finding crime hotspots than physical boundaries, suggesting that they should be highlighted in spatial crime analysis. This implies that analysis and policy should combine targeted measures at social boundaries with longer term actions that reduce inequalities and strengthen collective efficacy.

In summary, this study introduces a novel approach to measuring and utilizing social boundaries for theft prediction, and provides new insights into their criminogenic impact. The findings offer practical implications for policy, suggesting that governments should strengthen oversight of boundary zones and promote social integration to address the root causes of urban crime.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/urbansci10010013/s1, Figure S1: Spatial correspondence between theft hotspots mapped from first instance judicial records and police call out data in Haizhu District, Guangzhou; Figure S2: SHAP analysis result of RF model; Figure S3: Feature importance with recruitment threshold of 3 postings per grid cell; Figure S4: Feature importance with recruitment threshold of 5 postings per grid cell; Table S1: Spearman correlations of feature importance across recruitment thresholds.

Author Contributions

T.C.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Project administration. R.C.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Z.X.: Data curation, Software. X.G.: Methodology, Validation, Writing—review and editing C.W.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52078217), the Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2024A1515011998), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, International (Regional) Cooperation and Exchange Program (Grant No. 52561135229). The APC was supported via an article processing charge discount available to authors affiliated with the University of Cambridge through MDPI’s Institutional Open Access Program.

Data Availability Statement

Research data has been provided in Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Smith, S.J. Crime, Space and Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986; ISBN 0-521-26456-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Can Streets Be Made Safe? Urban Des. Int. 2004, 9, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-A.; Hipp, J.R. Both Sides of the Street: Introducing Measures of Physical and Social Boundaries Based on Differences Across Sides of the Street, and Consequences for Crime. J. Quant. Criminol. 2022, 38, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legewie, J. Living on the Edge: Neighborhood Boundaries and the Spatial Dynamics of Violent Crime. Demography 2018, 55, 1957–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantingham, P.L.; Brantingham, P.J. Nodes, Paths and Edges: Considerations on the Complexity of Crime and the Physical Environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-A.; Hipp, J.R. Physical Boundaries and City Boundaries: Consequences for Crime Patterns on Street Segments? Crime Delinq. 2018, 64, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengert, G.; Chakravorty, S.; Bole, T.; Henderson, K. A Geographic Analysis of Illegal Drug Markets. Crime Prev. Stud. 2000, 11, 219–240. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Andresen, M.A.; Brantingham, P.L.; Spicer, V. Crime on the Edges: Patterns of Crime and Land Use Change. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 44, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M.; Molnár, V. The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantingham, P.J.; Tita, G.E.; Short, M.B.; Reid, S.E. The Ecology of Gang Territorial Boundaries. Criminology 2012, 50, 851–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Spicer, V.; Brantingham, P. The Edge Effect: Exploring High Crime Zones near Residential Neighborhoods. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics, Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 June 2013; pp. 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S. Nonlinear Relationships and Interaction Effects of an Urban Environment on Crime Incidence: Application of Urban Big Data and an Interpretable Machine Learning Method. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 91, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, P.; Leonida, L. Non-Market Effects of Education on Crime: Evidence from Italian Regions. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2009, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. Crime Prediction Methods Based on Machine Learning: A Survey. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 74, 4601–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.G.A.; Ribeiro, H.V.; Rodrigues, F.A. Crime Prediction through Urban Metrics and Statistical Learning. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2018, 505, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Stewart, K.; Fan, J. Incorporating Space and Time into Random Forest Models for Analyzing Geospatial Patterns of Drug-Related Crime Incidents in a Major U.S. Metropolitan Area. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 87, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, R.J.; Chang, O.Y.; Cowen, C.; Hankins, R.; Langston, S.; Warner, A.; Yang, X.; Louderback, E.R.; Roy, S.S. Spatial Patterns of Larceny and Aggravated Assault in Miami–Dade County, 2007–2015. Prof. Geogr. 2018, 70, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaine, E.E.; Tewksbury, R. Predicting Risks of Larceny Theft Victimization: A Routine Activity Analysis Using Refined Lifestyle Measures. Criminology 1998, 36, 829–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Land, K.C.; Wang, J. Social Ties, Collective Efficacy and Perceived Neighborhood Property Crime in Guangzhou, China. Asian Criminol. 2013, 8, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Liu, L.; Zhou, S.; Song, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, R. Assessing the Impact of Street-View Greenery on Fear of Neighborhood Crime in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounadi, O.; Ristea, A.; Araujo, A.; Leitner, M. A Systematic Review on Spatial Crime Forecasting. Crime Sci. 2020, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Liu, L.; Feng, J.; Song, G.; He, Z.; Cao, J. Comparisons of the Community Environment Effects on Burglary and Outdoor-Theft: A Case Study of ZH Peninsula in ZG City. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Liu, Y.; Cao, G.; Samson, E.L.; Zhang, J. Forecasting China’s GDP at the Pixel Level Using Nighttime Lights Time Series and Population Images. GIScience Remote Sens. 2017, 54, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, P.G.; Forsyth, A.; Kan, H.Y. China’s Urban Communities: Concepts, Contexts, and Well-Being; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-0356-0833-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, P.; Chen, B.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Fang, L.; Feng, S.; et al. Mapping Essential Urban Land Use Categories in China (EULUC-China): Preliminary Results for 2018. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xi, X.; Yang, W.; Liang, L. Monitoring Land Use/Cover Change Using Remotely Sensed Data in Guangzhou of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, H. Fine extraction of urban villages in provincial capitals based on multivariate data. Gtzyyg 2021, 33, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, J.H.; Gallupe, O. Has COVID-19 Changed Crime? Crime Rates in the United States during the Pandemic. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 45, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, L.; Song, G.; Zhu, C. The Long-Term Theft Prediction in Beijing Using Machine Learning Algorithms: Comparison and Interpretation. Crime Delinq 2023, 71, 2061–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, V.A.; Eden, M.R. Formation Lithology Classification Using Scalable Gradient Boosted Decision Trees. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2019, 128, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononenko, I. Estimating Attributes: Analysis and Extensions of RELIEF. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning: ECML-94; Bergadano, F., De Raedt, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Garcia, S.; Herrera, F.; Chawla, N.V. SMOTE for Learning from Imbalanced Data: Progress and Challenges, Marking the 15-Year Anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 863–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liaw, A.; Breiman, L. Using Random Forest to Learn Imbalanced Data; Department of Statistics, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Luu, C.; Pham, B.T.; Phong, T.V.; Costache, R.; Nguyen, H.D.; Amiri, M.; Bui, Q.D.; Nguyen, L.T.; Le, H.V.; Prakash, I.; et al. GIS-Based Ensemble Computational Models for Flood Susceptibility Prediction in the Quang Binh Province, Vietnam. J. Hydrol. 2021, 599, 126500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Pradhan, B.; Hong, H.; Bui, D.T.; Duan, Z.; Ma, J. A Comparative Study of Logistic Model Tree, Random Forest, and Classification and Regression Tree Models for Spatial Prediction of Landslide Susceptibility. CATENA 2017, 151, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Rudin, C.; Dominici, F. All Models Are Wrong, but Many Are Useful: Learning a Variable’s Importance by Studying an Entire Class of Prediction Models Simultaneously. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 20, 177. [Google Scholar]

- He, S. Evolving Enclave Urbanism in China and Its Socio-Spatial Implications: The Case of Guangzhou. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2013, 14, 243–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tung, V.W.S. Residents’ Discrimination against Tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guangzhou Municipal Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources. Haizhu District Branch Office Public Announcement of the Draft National Territory Spatial Planning of Haizhu District, Guangzhou City (2021–2035). 2023; p. 16. Available online: https://www.haizhu.gov.cn/hzdt/hzyw/hzzc/content/post_10199965.html (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kitteringham, G.; Fennelly, L.J. Chapter 19-Environmental Crime Control. In Handbook of Loss Prevention and Crime Prevention, 6th ed.; Fennelly, L.J., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 207–222. ISBN 978-0-12-816459-4. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, B.R.; Hunt, J. Collective Efficacy: Taking Action to Improve Neighborhoods. NIJ J. 2016, 277, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.