Abstract

The behavior of shield tunnel lining structures is known to be influenced by segmental joints. Most studies conducted in this area use simplified models, which may not properly simulate the behavior of the segmental joints. This study utilizes a full-reinforced concrete segment model to rigorously investigate the seismic behavior of joints in a segmental tunnel lining, explicitly accounting for segment–segment contact, interaction, and joint bolts. Specifically, a comprehensive full dynamic analysis of a two-dimensional (2D) lining–soil model, incorporating nonlinear constitutive models for both concrete (CDPM) and soil (Mohr–Coulomb), was conducted to investigate the effects of joint bolt type, seismic intensity, and vertical excitation component on the seismic response. The lining–soil model was excited using three ground motions. The results indicate that the joint rotation is significantly influenced by the amplitude and frequency content of ground motions, which has implications for the watertightness of the gasketed joint. In particular, including the vertical component of the excitations was found to increase the diametral deformation by at least 150% and tended to increase other structural responses. Moreover, the bolt tension increased significantly by over 400% with only a 150% increase in seismic intensity, highlighting the strong nonlinear sensitivity. However, due to the inherent constraints of the 2D plane-strain assumption, the influence of the bolt type remains inconclusive.

1. Introduction

The shield tunneling technique, a fully mechanized method of excavation (or boring) consisting of a shield (i.e., a protective cylindrical structure) and trailing support mechanisms, has been extensively used to construct tunnels in urban and non-urban areas across the globe. The tunnels are used for either transportation or water conveyance and are often circular. The lining structure of a segmental tunnel consists of multiple precast segments linked by well-designed joints. These joints typically comprise steel bolts, gasket grooves, and gaskets. Generally, the overall behavior of the tunnel lining is governed by the joint. Accordingly, many researchers have investigated the mechanical behavior of segmental joints through analytical modeling [1], numerical analyses [2], full-scale in situ experiments [3], full-scale experiments [4], and model-scale experiments [5,6].

Similarly to other structures, underground tunnels are designed to meet functional and load-carrying capacity requirements. Specifically, waterproofness is a key aspect of the functional requirements of the tunnel. According to Dammyr et al. [7] and Zhang et al. [8], potential leakage paths in tunnel linings are cracks in the concrete segment, grouting sockets, and segment joints. Leakages through the segmental joints, however, are the most common [9]. The joints in one-pass segmental lining systems are fitted with elastomeric rubber gaskets to prevent groundwater ingress and guarantee the watertightness of the tunnel. As a result, revealing the leakage behavior of the gasketed joint is critical to ensuring the serviceability of the tunnel structure. The literature on the sealant behavior of gasketed joints is vast. The studies, comprising numerical and experimental investigations, have focused on both the mechanical and waterproofing behaviors of gaskets by applying static, water pressure, and cyclic loadings. A major observation from these studies, which is of interest to the present study, is that a large joint opening (greater than 6 mm), joint rotation, and joint offset have adverse effects on the waterproofing performance of the segmental joints [10,11,12,13,14,15].

The gasket contact pressure developed in installed lining rings can be altered by opening segment joints. Such alterations may arise as a result of imperfections and/or construction errors, or ground static loads and ground shaking. These loads cause the tunnel lining to deform into an oval shape, thereby causing joint rotation and offsetting the segmental linings at the joint. The degree of lining segment deformation and joint rotation depends significantly on the lining and soil stiffness. The stiffness of the tunnel lining is influenced by factors such as (i) interaction between segments of adjacent rings, (ii) bolting and relative stiffness between the segments, (iii) the shape of the joint contact surfaces, and (iv) the number of segments in each ring [16].

The design of segmental tunnel linings accommodates distortions and deflections caused by ground and surcharge loads [17,18]. During the operation phase, tunnels may be subjected to cyclic loading, such as ground motions due to earthquakes. While tunnels generally perform better than above-ground structures during earthquakes, the damage to some tunnels during past earthquake events has highlighted the need to account for seismic load in the design of tunnels [19]. The behavior of segmental joints under the excitations is critical because most tunnel deformation occurs at the joints, which may lead to excessive joint distortion that can affect the waterproofing function of the gasket sealant.

The seismic behavior of tunnels has been investigated using various approaches: numerical modeling, physical model tests, and empirical and analytical methods. The necessity of ignoring segmental joints and soil–structure interactions (when using empirical and analytical methods) and the difficulty in observing complex tunnel behavior due to the high cost associated with the tests (the physical model test) have led to the extensive use of numerical modeling to investigate tunnel behavior [20]. Numerical techniques involve either pseudo-static or full dynamic analysis. Full dynamic analysis is considered reliable and precise, albeit computationally expensive [20,21]. To date, several researchers have applied numerical analysis to investigate the behavior of segmental tunnels [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Most studies modeled tunnels as elastic beams and simulated the joints using pin, hinge, or spring models. Such modeling techniques may not properly/accurately simulate segmental joint behavior because they fail to consider the contact and interaction between the segmental linings as well as the effect of joint bolts. Moreover, modeling the joints of segmental tunnels as springs with certain stiffnesses may not realistically simulate the complex behavior of the joints under varying loading conditions [14]. Explicitly modeling the segmental tunnel lining and joints will enhance our understanding of the behavior of tunnels subjected to seismic excitations, leading to the development of improved methodologies for the reliable design of segmental tunnel structures.

The authors acknowledge that the use of a 2D plane-strain model is a simplifying assumption for segmental tunnel linings, as joints and bolts are inherently three-dimensional. However, it is widely accepted for capturing the global circumferential behavior of linings under uniform or slowly varying longitudinal loads, where plane-strain conditions are approximately satisfied. In mechanized tunneling, higher longitudinal stiffness means that lining response is dominated by circumferential bending and joint rotation, which can be effectively represented in 2D using appropriate joint constitutive models. While longitudinal joint interaction and ring-to-ring effects may influence localized stresses and bolt forces, these are generally secondary for global lining behavior. Such three-dimensional effects become critical mainly under pronounced longitudinal irregularities (i.e., sharp longitudinal curvature, fault crossings, or significant construction imperfections) [29,30,31], and their detailed assessment is therefore beyond the scope of the present study.

The current study utilizes a full-reinforced concrete segmental lining model to investigate the seismic behavior of the lining and segmental joints. A two-dimensional (2D) finite element (FE) model, comprising bolted reinforced segmented linings and a soil medium, is exposed to full seismic excitation via nonlinear time history analysis. The numerical results highlight the influence of joint bolt type, seismic intensity, and vertical excitation on joint behavior. This paper is organized as follows. A brief description of the tunnel lining adopted for the study is presented in Section 2. Section 3 discusses the numerical modeling of the tunnel lining, as well as the analysis conducted to investigate the seismic response of the tunnel lining. The static and dynamic behavior of the tunnel lining is discussed in Section 4. Finally, the conclusions of this study are summarized in Section 5.

2. Description of Prototype Segmental Tunnel Lining

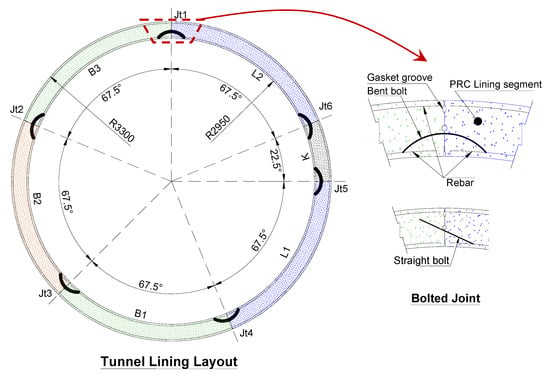

The segmental tunnel lining considered in this study was adapted from the lining used in the study by Zhang et al. [14]. The lining consists of rings of precast reinforced concrete segments connected by bolts and sealed using rubber gaskets. The layout (or transverse profile) of a typical ring of segments is shown in Figure 1. The tunnel cross-section has an external diameter of 6.6 m and an internal diameter of 5.9 m. One key segment (K), two adjacent segments (L1–L2), and three standard segments (B1–B3) are included in an integrated ring. Bent bolts, denoted as B1, are used to connect the segments in the prototype lining. Additionally, straight inclined bolts (denoted as B2) connect the segments in this study for comparison. The segmented ring has a thickness of 350 mm and a width of 1500 mm. Two 30 mm bolts spaced 785 mm apart connect the segments along the longitudinal joints. The precast segments were assumed to be reinforced with 14 mm bars placed at 150 centers.

Figure 1.

Layout of the precast reinforced concrete (PRC) segments in the prototype lining (Unit: mm). The colors delineate the individual lining segments: red and green indicate the three standard segments (B1–B3), blue indicates the two adjacent segments (L1–L2), and black indicates the key segment (K).

3. Numerical Modeling and Analysis

3.1. Lining–Soil Model

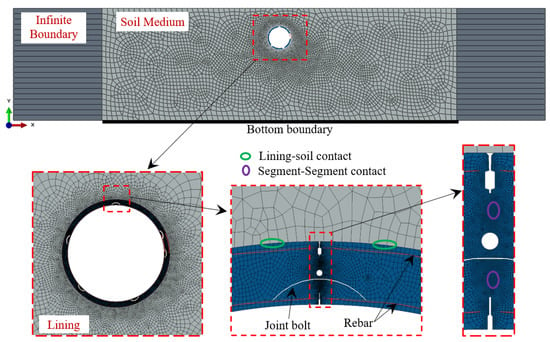

The 2D plane-strain lining–soil numerical (finite element) model developed to investigate the behavior of the segmental tunnel linings under seismic excitation is shown in Figure 2. The model comprises the reinforced concrete segmental lining, joint bolts, and surrounding soil. The numerical model is 225 m wide in the horizontal direction and 31.6 m high in the vertical direction. A 150 m-width soil deposit was adopted to minimize the influence of boundaries on the tunnel response. In order to simulate an infinite elastic space, infinite boundaries [32] were placed at the left- and right-side borders of the model to avoid wave reflection. Moreover, a sensitivity study established that the tunnel–soil structure interaction region may extend up to three diameters from the tunnel center [20]. The lateral boundaries in this study extended more than 11 tunnel diameters. The tunnel was buried 5 m below the ground surface. The finite element model was developed using the ABAQUS 2020 software package [32]. The concrete and soil components were discretized using a combination of 4-node bilinear, reduced integration with hourglass control (CPE4R) and 3-node linear (CPE3) elements, whereas the rebars and bolts were discretized using a 2-node linear 2-D truss (T2D2) element. CINPE4 elements were used to model the infinite boundaries. The whole mesh comprised 45,164 elements. The adequacy of the element size was determined by applying an accuracy-based adaptive remeshing technique in ABAQUS to the model, as well as by satisfying Equation (1) [33], which ensures the accurate representation of the transmission of the seismic wave through the model mesh.

where is the side length of the element, is the shear wave velocity of interest, and is the highest predominant frequency of the lining–soil system but not less than 5–6 Hz.

Figure 2.

Schematic of lining–soil finite element model.

3.1.1. Material Model

The concrete damage plasticity model (CDPM) was used to model the behavior of the precast segment. The material parameters of the CDPM included the uniaxial stress–strain relationships, damaged plasticity, and elasticity. The elastic parameters of the concrete, namely the mass density, elastic modulus, and Poisson’s ratio, were assumed to be 2450 kg/m3, 35,000 MPa, and 0.2, respectively. For the CDPM parameters, the default values of 0, 0.667, 1.16, 0.1, and 31 were adopted for the viscosity parameter, ratio of the second stress invariant on the tensile meridian to that on the compressive meridian (K), ratio of initial equibiaxial compressive yield stress to initial uniaxial compressive yield stress (fb0/fc0), flow potential eccentricity, and dilation angle, respectively. The concrete class was assumed as C40/50, and the constitutive parameters (stress–strain relationship of the concrete) were adopted from the literature [34].

The steel reinforcement had the following mechanical properties: a mass density of 7800 kg/m3, an elastic modulus of 200,000 MPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3. An idealized tensile stress–strain relationship with a yield strength of 360 MPa and an ultimate tensile stress and plastic strain of 400 MPa and 0.0567, respectively, were assigned to this material. Similarly, the high-tensile steel bolt had the following mechanical properties: a mass density of 7800 kg/m3, an elastic modulus of 210,000 MPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3. Moreover, an idealized tensile stress–strain relationship with a yield strength of 640 MPa and an ultimate tensile stress and plastic strain of 800 MPa and 0.0471, respectively, were assigned to this material. In the plane-strain Abaqus model, the longitudinally spaced bolts are represented using 2D truss elements with an equivalent smeared stiffness formulation. Since the physical bolts are installed at discrete points along the tunnel axis, the truss cross-sectional area is scaled by the bolt spacing to ensure stiffness equivalence per unit tunnel length, such that . This approach avoids unrealistically representing the bolts as a continuous steel layer and prevents overestimation of joint stiffness.

The Mohr–Coulomb plasticity model (or failure criterion) was adopted as the soil constitutive model. Even though Do et al. [20] noted that the choice of the soil constitutive model could influence overall tunnel behavior, they observed that its effect at low to moderate excitation intensity is negligible. In this study, the soil material was assigned the following properties: a mass density of 1800 kg/m3, an elastic modulus of 450 MPa, a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3, a friction angle of 30°, a dilation angle of 1°, and a cohesion yield stress of 0.1 MPa.

3.1.2. Contact Model

The surface-based contact model in ABAQUS was used to explicitly model the lining-soil and segment–segment interactions, as shown in Figure 2. The hard-contact and Coulomb friction models were implemented to simulate the contact interactions in the normal and tangential directions, respectively. Friction coefficients of 0.6 [35] and 0.45 [36], applied in the tangential direction, were used for the segment–segment and lining–soil contact, respectively.

3.1.3. Boundary Conditions

A two-step analysis—static and then dynamic—was applied in this study. Only the self-weight of the lining–soil structure was considered in the static step. Hence, the vertical and horizontal movement and the in-plane rotation (U1 = U2 = R3 = 0) were restrained at the bottom boundary. However, in the dynamic step, only the vertical movement was restrained (U2 = 0) when the ground motion acceleration time history was applied to the bottom boundary in the horizontal direction only. No restraint was applied to the structure when the model was excited using both the horizontal and vertical acceleration time histories.

3.2. Numerical Analysis

The numerical analysis performed on the model involved two loading steps—gravity (static) and seismic (dynamic). For the dynamic analysis, a full time history analysis based on the Hilber–Hughes–Taylor (HHT) integration procedure [37] was performed using the ABAQUS software. The analysis time step varied from 5 × 10−3 to 10−6 s according to convergence demands. In solving for the response of a structural system under time-dependent loading, the dynamic equation of motion in the HHT procedure is expressed as follows.

in the form

where [M], [C], and [K] are the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively; , , and are the acceleration, velocity, and displacement vectors, respectively; is the external force vector; t is time; is the time increment; and , , and are control, accuracy, and stability parameters, where , , and .

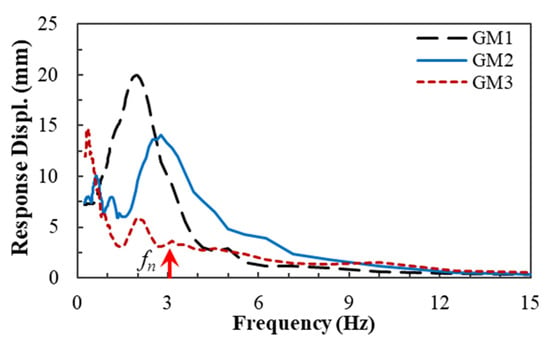

Rayleigh damping was used in the dynamic simulations to approximate the energy dissipation in the system due to viscous damping. The frequencies for Rayleigh damping, 3.05 Hz and 4.63 Hz, were determined from an undamped analysis. The damping ratio of the tunnel lining and soil medium was assumed to be 5% of critical damping. Seismic signals from three earthquakes, randomly selected from the Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER) ground motion database [38], were considered in this study. The details of the ground motions are presented in Table 1. Further, the displacement response spectra of the ground motions are shown in Figure 3. The three ground motions, GM1, GM2, and GM3, were scaled to peak ground accelerations of 0.17 g and 0.42 g to investigate the effects of ground motion intensity on the concrete segment stress, joint rotation and displacement, and bolt tension responses of the segmental lining structure.

Table 1.

Details of ground motions employed in this study.

Figure 3.

Displacement response spectra of the three ground motions.

4. Results

This section presents results obtained from the analysis performed on the lining–soil model. Note that the static response of the model is not presented separately but integrated into the seismic analysis, as the static analysis under gravity loading serves as the initial stage of the dynamic (seismic) analysis. The discussion on the seismic response of the model is presented in terms of the diametral deformation of the lining, stress response in the concrete segments, displacement and rotation at the joints, and tension in the bolts by considering the effects of bolt type, seismic intensity, and vertical excitation component.

4.1. Diametral (Or Cross-Sectional) Deformation of the Lining

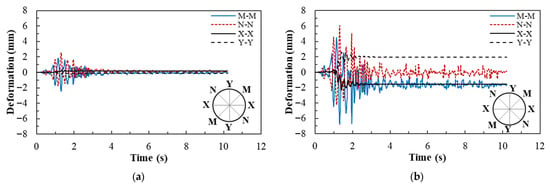

The diametral (or cross-sectional) deformations of the lining along the horizontal direction (X-X), vertical direction (Y-Y), and diagonal directions (M-M and N-N) during the Lytle Creek (Cedar Springs Pumphouse) earthquake of 1970 (GM2), scaled to a peak ground acceleration (PGA) of 0.17 g and 0.42 g are shown in Figure 4. Noticeably, the maximum elongation and closing of the lining occur along the diagonal directions, consistent with the deformation mode (ovaling) of tunnels with circular sections subjected to shaking in the transverse direction [39]. Furthermore, the residual (or irreversible) deformation under the 0.42 g-amplitude shaking is approximately 11 times more than that under 0.17 g. The maximum diagonal diametral deformation under three ground motions, considering the horizontal (H) and horizontal and vertical (H+V) excitations, is summarized in Table 2. The differences in the responses under the horizontal excitations of amplitudes 0.17 g and 0.42 g are attributable to the frequency content of the earthquakes. The responses caused by GM2 exceeded those by GM1 and GM3 under all excitation conditions. GM2 excited a higher displacement response (Figure 3) that produced the observed larger diametral and residual deformations. The results also revealed that including the vertical excitation increased the diametric deformation by approximately 150% for both GM1 and GM2 and 420% for GM3. Thus, considerable deformation of the lining could be induced under multicomponent excitations due to the vibration response characteristics of the ground.

Figure 4.

Diametral deformations of the lining under the Lytle Creek earthquake (GM2), considering two amplitude levels: (a) excitation amplitude of 0.17 g; (b) excitation amplitude of 0.42 g.

Table 2.

Maximum diametral (cross-sectional) deformation (mm).

4.2. Segmental Joint Displacement and Rotation

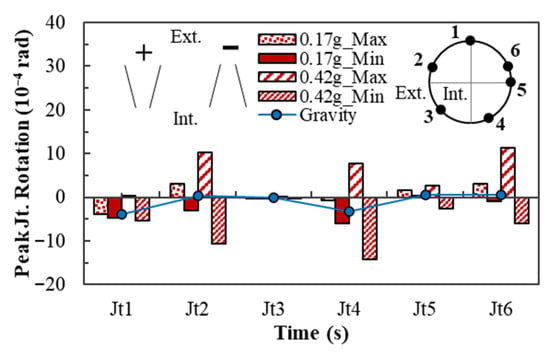

The segmental joint deformation is expressed in terms of the tangential joint displacement and joint rotation. The angle of rotation at the joints is defined as the ratio of the difference between the exterior and interior tangential joint displacements to the tunnel lining thickness. The peak clockwise and counterclockwise (“+/−”) joint rotations under the horizontal (H) and horizontal and vertical (H+V) acceleration time histories of the Lytle Creek (Cedar Springs Pumphouse) earthquake (GM2) are shown in Figure 5. Further, the “+” and “−” joint rotations are illustrated in Figure 5. The figure typifies the rotational joint behavior for all the ground motions considered. Notably, the joint rotation behavior exhibited significant variability. According to Figure 5, rotation under the gravity load is high at joints Jt1 and Jt4, whereas rotations under the excitation occur at joints Jt2, Jt4, and Jt5. The larger amplitude shaking excites higher positive (+) rotations at joints Jt2, Jt4, and Jt5, making them more susceptible to groundwater ingress due to the geometric configuration of the gasketed joint. The above observation reveals that the rotation of the joints can be significantly affected by ground shaking, and the effects could vary greatly depending on the amplitude of the excitations.

Figure 5.

Peak radial joint rotation under the gravity and Lytle Creek earthquake (GM2) loadings.

The maximum joint rotation in the lining under the three ground motion records (GM1, GM2, and GM3) for two joint bolt types (bent, B1, and straight, B2) and the three excitation conditions (H_0.17 g, H_0.42 g, and H+V_0.17 g) are summarized in Table 3. Similarly to the response of the diametral deformation and stress in the segment, the rotation of the joint is positively influenced by the frequency content and amplitude of the earthquake. As presented in Table 3, the inclusion of vertical excitation tends to increase the maximum joint rotation. Similarly, using straight but inclined bolts instead of bent ones at the joint can increase joint rotations. The maximum tangential displacements at the joints under the GM1, GM2, and GM3 were estimated as 0.05 mm, 0.14 mm, and 0.03 mm, respectively. The estimated displacements (or openings) were insufficient to allow groundwater leakage through the gasket opening during excitation [8,14].

Table 3.

Maximum joint rotations (×10−4 rad).

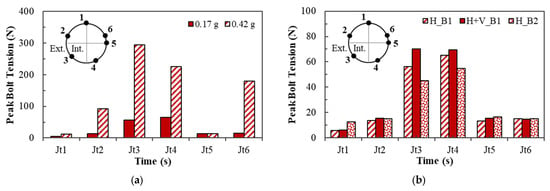

4.3. Tension in the Segmental Joint Bolts

The seismic response of the segmental joint can also be expressed in terms of bolt tensions. The tension in the bolts at the six joints under the 0.17 g and 0.42 g seismic intensities and the horizontal and vertical time histories of the Lytle Creek earthquake are shown in Figure 6. According to Figure 6a, the bolt tension is the largest for bolts at joints Jt3 and Jt4 under the 0.42 g and 0.17 g amplitude excitation. The higher bolt tension in the bolt at Jt4 is consistent with the observed distribution of the magnitude of joint rotation (Figure 5). However, the bolt tension observed at Jt3 indicates the restraint provided by the bolt to tangential joint opening instead of joint rotation. Figure 6b compares the influence of the bolt type (B1 and B2) and the excitation component on the bolt tension. Noticeably, the inclusion of the vertical excitation increases the bolt tension. Conversely, the straight and inclined bolt type B2 causes a significant decrease in the bolt tension at Jt3 and Jt4—the joints with the largest response.

Figure 6.

Peak joint bolt tension: (a) for two amplitudes of the Lytle Creek earthquake (GM2) (b) for the two bolt types and ground motion excitation component.

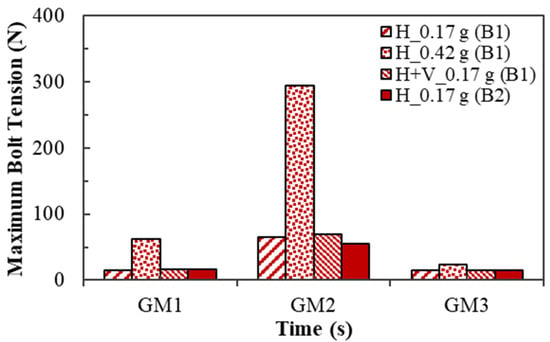

The influence of the three ground motions on the bolt tension is assessed by comparing the maximum bolt tension in the lining, as shown in Figure 7. Similarly to the observations made thus far, the frequency content and amplitude of the earthquake had noticeable effects on the maximum bolt tension. This effect is most pronounced under GM2, particularly when considering the bolt type and the excitation condition. On the contrary, GM1 and GM3 did not appear to influence the bolt tension when considering the different bolt types and the inclusion of vertical excitation.

Figure 7.

Comparison of maximum joint bolt tension for the three excitations considering the effect of seismic intensity, excitation component, and bolt type.

5. Discussion

The numerical results demonstrate that the seismic response of segmental tunnel linings is governed primarily by ovaling deformation and joint behavior, in agreement with classical analytical and numerical studies on circular tunnels subjected to transverse seismic waves [39]. The dominance of diagonal diametral deformation observed in this study confirms that shear-wave-induced distortion remains the primary deformation mechanism for tunnels in soft to medium ground conditions. The pronounced increase in lining deformation and joint rotation with increasing PGA highlights the nonlinear response of both the lining joints and surrounding ground. The significantly larger response under GM2 compared to GM1 and GM3 emphasizes the critical role of earthquake frequency content, consistent with findings by several authors, who demonstrated that ground motion characteristics strongly influence underground structural response beyond PGA alone [25,26,27,28]. The substantial amplification caused by the inclusion of vertical excitation further supports recent numerical and experimental evidence that vertical ground motion can contribute significantly to tunnel lining distress, particularly in jointed linings [25].

Joint rotation patterns indicate that seismic loading can shift the most critical joints away from those governing the static response. This observation has important design implications, as joints that are not critical under gravity loading may become vulnerable during earthquakes. Similar redistribution of joint demand under dynamic loading has been reported in previous segmental lining studies [30,40]. The relatively small joint openings predicted in this study suggest that, for the considered loading levels, gasket integrity is likely maintained, corroborating experimental findings reported by Blom [41]. Bolt tension results reveal a strong coupling between joint kinematics and bolt force demand. The higher bolt forces observed at joints with limited rotation but significant tangential restraint (e.g., Jt3) highlight the importance of bolt axial stiffness in controlling joint opening. The reduction in bolt tension observed for the straight, inclined bolt configuration suggests that bolt geometry can play a beneficial role in redistributing seismic demand, a finding that aligns with recent experimental observations on alternative joint fastening systems.

Overall, the results confirm that simplified plane-strain numerical models, when equipped with realistic joint and bolt representations, can capture key aspects of the seismic behavior of segmental tunnel linings. The study contributes to existing literature by explicitly quantifying the combined effects of vertical excitation and bolt configuration on joint rotation and bolt force demand, aspects that remain insufficiently addressed in current tunnel seismic design guidelines.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigates the seismic behavior of concrete linings and segmental joints of a prototype precast segmental lining structure through full dynamic analysis using a full-reinforced concrete segment model. This approach, which explicitly models contact and interaction, represents an advancement over conventional simplified methods. A lining–soil model was developed for the study. The model was excited using three earthquake acceleration time histories to evaluate the joint rotation and displacement, and bolt tension responses of the segmental lining structure, which were discussed from the perspective of the effects of joint bolt type, seismic intensity, and vertical excitation component on the seismic behavior of the joint and tunnel lining. By considering these parameters and using a full-scale modeling technique, the study makes unique contributions to our understanding of the behavior of segmental tunnels subjected to seismic excitations. The results revealed the following key findings:

- Ground motion characteristics, namely amplitude and frequency content, influenced the joint rotation and displacement, and bolt tension responses of the segmental lining structure. For example, the higher amplitude and frequency time history caused the highest responses and residual deformation. Furthermore, increasing the excitation amplitude by 150% produced an increase in the bolt tension of over 400%.

- Residual deformation in the segmental lining structure was more pronounced under high- than low-amplitude time histories.

- Including the vertical component in the analysis caused at least a 150% increase in the diametral deformation of the lining structure. It also showed the tendency to increase the segmental joint rotation and bolt tension. The increase in the estimated responses is attributable to the vibration response characteristics of the ground.

- Bolt-type effects on the segmental tunnel lining and joint behavior are inconclusive. For example, whereas the bolt tension responses were lower for the bent and horizontally placed bolts under GM2, those under GM1 and GM3 demonstrated no noticeable difference for the bent and horizontally placed, and straight and inclined bolts.

This study used a 2D plane-strain model to perform a rigorous nonlinear dynamic analysis. A three-dimensional model of the lining tunnel can be considered to evaluate the effect of the bolt hole on the joint behavior under excitation. Future works may also extend the analysis to fully three-dimensional models to explicitly address ring-to-ring interaction and longitudinal load transfer mechanisms, which are known to influence localized stresses and bolt forces. Generally, this study has highlighted the need to consider multicomponent ground motions when conducting seismic analysis of segmental tunnel linings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K.M. and J.H.; methodology, B.K.M.; software, B.K.M.; validation, J.H., J.-H.A. and K.K.; formal analysis, B.K.M.; investigation, B.K.M.; resources, J.H.; data curation, J.-H.A. and K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.M.; writing—review and editing, J.H., J.-H.A. and K.K.; visualization, B.K.M., J.H. and J.-H.A.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, J.H.; funding acquisition, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Chonnam National University, grant number 2021-3972.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by Chonnam National University (Grant number: 2021-3972).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zhang, L.; Feng, K.; Li, M.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; Xiao, M. Analytical Method Regarding Compression-Bending Capacity of Segmental Joints: Theoretical Model and Verification. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 93, 103083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, H. A Progressive Model to Simulate the Full Mechanical Behavior of Concrete Segmental Lining Longitudinal Joints. Eng. Struct. 2015, 93, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molins, C.; Arnau, O. Experimental and Analytical Study of the Structural Response of Segmental Tunnel Linings Based on an in Situ Loading Test.: Part 1: Test Configuration and Execution. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2011, 26, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Kubota, T.; Furukawa, M.; Nakao, T. Unified Construction of Running Track Tunnel and Crossover Tunnel for Subway by Rectangular Shape Double Track Cross-Section Shield Machine. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2003, 18, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, M.; Ghalandarzadeh, A.; Akhlaghi, T.; Ahmadi, M. Experimental Evaluation of Vulnerability for Urban Segmental Tunnels Subjected to Normal Surface Faulting. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 89, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, M.; Akhlaghi, T.; Ghalandarzadeh, A. Experimental Modeling of Segmental Shallow Tunnels in Alluvial Affected by Normal Faults. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 51, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammyr, Ø.; Nilsen, B.; Thuro, K.; Grøndal, J. Possible Concepts for Waterproofing of Norwegian TBM Railway Tunnels. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2014, 47, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, W.; Cao, W.; Wang, B.; Lai, T.; Guo, W.; Gao, P. A Novel Test Setup for Determining Waterproof Performance of Rubber Gaskets Used in Tunnel Segmental Joints: Development and Application. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 115, 104079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-N.; Huang, R.-Q.; Sun, W.-J.; Shen, S.-L.; Xu, Y.-S.; Liu, Y.-B.; Du, S.-J. Leaking Behavior of Shield Tunnels under the Huangpu River of Shanghai with Induced Hazards. Nat. Hazards 2014, 70, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ding, W.; Soga, K.; Mosalam, K.M.; Tuo, Y. Sealant Behavior of Gasketed Segmental Joints in Shield Tunnels: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 77, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ding, W.; Soga, K.; Mosalam, K.M. Failure Mechanism of Joint Waterproofing in Precast Segmental Tunnel Linings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 84, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ding, W.; Xie, D. Parametric Investigation on the Sealant Behavior of Tunnel Segmental Joints Under Water Pressurization. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 97, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Gong, C.; Mosalam, K.M.; Soga, K. Development and Application of the Integrated Sealant Test Apparatus for Sealing Gaskets in Tunnel Segmental Joints. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 63, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-L.; Zhang, W.-J.; Li, H.-L.; Cao, W.-Z.; Wang, B.-D.; Guo, W.-S.; Gao, P. Waterproofing Behavior of Sealing Gaskets for Circumferential Joints in Shield Tunnels: A Full-Scale Experimental Investigation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 108, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Zhu, B.; Gong, C.; Ding, W.; Liu, L. Sealing Performance of a Precast Tunnel Gasketed Joint Under High Hydrostatic Pressures: Site Investigation and Detailed Numerical Modeling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 115, 104082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalabi, F.I.; Cording, E.J.; Paul, S.L. Concrete Segment Tunnel Lining Sealant Performance Under Earthquake Loading. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2012, 31, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, M.; Nasri, V. New American Concrete Institute (ACI) Code for Design, Manufacturing and Construction of Tunnel Segmental Lining. BHM Berg Und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte 2019, 164, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.C.; Monsees, J.; Munfah, N.; Wisniewski, J. Technical Manual for Design and Construction of Road Tunnels—Civil Elements; AASHTO: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, G.; Calvi, G.M.; Soga, K.; Gong, C.; Ding, W. Cyclic Model with Damage Assessment of Longitudinal Joints in Segmental Tunnel Linings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 103, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.A.; Dias, D.; Oreste, P. 2D Seismic Numerical Analysis of Segmental Tunnel Lining Behaviour. Bull. N. Z. Soc. Earthq. Eng. 2014, 47, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabozzi, S.; Bilotta, E. Behaviour of a Segmental Tunnel Lining Under Seismic Actions. Procedia Eng. 2016, 158, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.-A.; Dias, D.; Oreste, P.; Djeran-Maigre, I. Behaviour of Segmental Tunnel Linings Under Seismic Loads Studied with the Hyperstatic Reaction Method. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 79, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Massimino, M.R. Parametric Analysis of the Seismic Response of Coupled Tunnel–Soil–Aboveground Building Systems by Numerical Modelling. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 15, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, W.; Song, C.; Yu, H.; Yuan, Y. Seismic Response of Segmental Lining Tunnel by Using Shaking Table Test and Numerical Simulation. In Proceedings of GeoShanghai 2018 International Conference: Advances in Soil Dynamics and Foundation Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- Razavian Amrei, S.A.; Vahdani, R.; Gerami, M.; Amiri, G.G. Correlation Effects of Near-Field Seismic Components in Circular Metro Tunnels: A Case Study—Tehran Metro Tunnels. Shock Vib. 2020, 2020, 3016465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, J. 1 g Shaking Table Test of Segmental Tunnel in Sand Under Near-Fault Motions. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 115, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, H. Effect of Excitation Frequency on Segmental Tunnels in Sand Using 1 g Shaking Table Tests. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 34, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, C.; Qiu, J. Experimental Investigation of Seismic Performance of Shield Tunnel Under Near-Field Ground Motion. Structures 2022, 43, 1407–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheri, M.; Ranjbarnia, M.; Dias, D. 3D Numerical Investigation of Segmental Tunnels Performance Crossing a Dip-Slip Fault. Geomech. Eng. 2020, 23, 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Do, N.-A.; Dias, D.; Oreste, P.; Djeran-Maigre, I. 2D Numerical Investigation of Segmental Tunnel Lining Behavior. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2013, 37, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashash, Y.M.A.; Hook, J.J.; Schmidt, B.; I-Chiang Yao, J. Seismic Design and Analysis of Underground Structures. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2001, 16, 247–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABAQUS. ABAQUS Analysis User’s Manual, version 6.20; ABAQUS: Providence, RI, USA, 2020.

- ASCE 4-98; Seismic Analysis of Safety-Related Nuclear Structures and Commentary. American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7844-0433-1.

- Jankowiak, T.; Łodygowski, T. Identification of Parameters of Concrete Damage Plasticity Constitutive Model. Found. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2005, 6, 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- ACI 318-14; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hill, MI, USA, 2014.

- Sheng, D.; Wriggers, P.; Sloan, S.W. Application of Frictional Contact in Geotechnical Engineering. Int. J. Geomech. 2007, 7, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilber, H.M.; Hughes, T.J.R.; Taylor, R.L. Improved Numerical Dissipation for Time Integration Algorithms in Structural Dynamics. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1977, 5, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER). PEER NGA-West2 Ground Motion Database. Available online: https://ngawest2.berkeley.edu (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Tsinidis, G.; de Silva, F.; Anastasopoulos, I.; Bilotta, E.; Bobet, A.; Hashash, Y.M.A.; He, C.; Kampas, G.; Knappett, J.; Madabhushi, G.; et al. Seismic Behaviour of Tunnels: From Experiments to Analysis. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 99, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Ge, X.W. The Equivalence of a Jointed Shield-Driven Tunnel Lining to a Continuous Ring Structure. Can. Geotech. J. 2001, 38, 461–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, C.B.M. Design Philosophy of Concrete Linings for Tunnels in Soft Soils. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.