Abstract

This paper presents an approach to risk mitigation strategies through seismic vulnerability of buildings’ non-structural elements (NSEs) proposing practical and accessible strategies for risk reduction aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) framework. NSEs play a crucial role in the overall safety and resilience of built environments during seismic events. However, their vulnerability is often underestimated, despite their potential to cause significant human, economic, and social losses. Moreover, NSEs remain widely overlooked in both seismic risk assessments and mitigation strategies, including risk education. This issue directly impacts multiple SDGs. NSE damage exacerbates poverty by increasing financial burdens due to repair and recovery costs. It also affects access to quality education, not only by disrupting school infrastructure but also by limiting access to knowledge, which is essential for strengthening the coping capacity of communities. Furthermore, seismic risk mitigation must be inclusive to reduce inequalities, ensuring that safety is not a privilege but a right for all. Lastly, NSE vulnerability directly influences the resilience and sustainability of cities and communities, affecting urban safety and disaster preparedness. Simple mitigation actions, such as proper anchoring, reinforcement, or improved design guidelines, could drastically reduce their vulnerability and related consequences. Raising awareness of this underestimated issue is essential to foster effective policies and interventions.

1. Introduction

Earthquakes rank among the most catastrophic natural disasters recorded in history and continue to cause high death tolls despite major advances in understanding the associated risk [1,2]. Earthquakes’ impacts can range from localized effects to extensive consequences for communities, the economy, and the environment, even across wide areas experiencing non-heavy damage. In some cases, earthquakes can cause cross-border impacts and cascading events, namely tsunamis, landslides, liquefaction phenomena, fire, industrial accidents, business interruption, etc. [3]. Besides population at risk, earthquakes account for over a quarter (25.6%) of global economic disaster losses. Between 1970 and 2023, the economic cost of earthquakes accounted for an estimated USD 1.59 trillion [2]. Earthquakes can lead to prolonged and, in specific cases, multi-generational consequences, depending on the magnitude of the event, the vulnerability and aggregation of assets in areas prone to seismic activity, and the capacity of individuals and communities to withstand disruptive events [3].

Seismic risk expresses the expected probable losses due to earthquake’s ground shaking, measured through different metrics, e.g., economic, social, and environmental [4,5]. Since seismic activity is triggered by the movement of tectonic plates, regions where the boundaries of plates lay are naturally more prone to earthquakes, and this phenomenon is indeed a continuous, long-term process. Thus, areas with a history of earthquakes and active faults remain the most likely locations for future earthquakes, where seismic risk is not only high but is also a persistent global challenge.

The most impressive damage after an earthquake is structural failures, where buildings can be heavily damaged or even collapse. In masonry buildings, seismic damage is mostly associated with structural overloads induced by heavy earthen roofs and with overturns of out-of-plane walls due to inadequate wall-to-wall and wall-to-roof connections, along with the absence of ring beams and presence of large openings [6]. Moreover, the use of poor seismic performance material, often locally selected for the ease of construction, is another major factor contributing to the vulnerability and failure of these structures [6,7]. However, buildings are also affected by the often-overlooked vulnerability of non-structural elements (NSEs). These elements, although not part of the load-bearing system, are subjected to the building’s dynamic response during seismic events. Common NSEs, which have been often damaged during earthquakes and exhibit high seismic vulnerability, are listed as follows:

- -

- Suspended ceilings;

- -

- Fire sprinkler piping systems;

- -

- Partition walls;

- -

- Precast cladding panels;

- -

- Glazed curtain wall.

Damage to non-structural elements can cause injuries, disrupt services, hamper recovery, and account for a significant portion of the overall building cost. For instance, in commercial structures, expenditure related to non-structural elements range from 65% to 85% of the total cost [8]. Estimates of economic losses caused by NSEs have been computed for a specific earthquake [9], for a particular county [10], city [11], or for a database of sample buildings [8]. It is important to note that these costs are typically derived from existing data, often adjusted to potential future scenarios. Across all these assessments, losses attributed to NSEs range from 40% to 70% of the total for concrete structures. The share is significantly lower for wood structures (around 25%), but in such a case, losses related to contents can rise to 65% of the total [12]. Nevertheless, the issue of NSEs still receives limited attention in public discourse and policy, even though such damage can occur for low-magnitude seismic events, making it a critical topic for awareness raising, including in areas where earthquakes are not the main threat.

In most cases, NSEs are purchased by owners or tenants after the construction of a building, without the involvement of any design professional. This has both drawbacks and advantages: it makes each building unique and introduces specific vulnerabilities, yet individual occupants can effectively manage these elements. Indeed, damage to NSEs can be prevented if good practices are followed, which often require nothing more than appropriate behaviors by citizens.

In this paper, we discuss the impact of NSEs in reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These 17 goals [13] were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030, all people enjoy peace and prosperity. We explain how the decrease in non-structural elements’ seismic vulnerability can contribute to risk reduction strategies and support the achievement of selected SDGs.

2. Methodological Framework

This study is grounded in the central question: “Do on-structural elements (NSEs) affect the achievement of the Sustainable Development and if so, how?” The conceptual framework developed to address this question links NSEs to broader sustainable development outcomes, exploring how seismic damage to these elements can impact the SDG agenda. The analysis is not intended as a quantitative performance assessment of NSEs, but rather as a qualitative exploration of causal relationships between the impacts that seismic damage may have on selected SDG targets. The framework builds upon the existing literature in earthquake engineering, disaster risk reduction, and sustainability studies, integrating insights from these domains to identify the pathways through which NSE fragility can hinder or, conversely, support the attainment of the SDGs.

The framework proceeds from two key concepts:

- The relevance of seismic performance of non-structural elements. Even when buildings remain structurally intact after an earthquake, the failure of NSEs can trigger severe disruptions in essential services, generate economic losses, and compromise safety and well-being.

- Such disruptions have cascading effects that extend beyond the immediate physical damage, influencing community resilience, equity, and sustainability, which are core pillars of the SDG framework.

Based on these premises, the paper qualitatively maps and discusses the relationship between NSE damage and the SDGs most likely to be affected, namely those presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The impact that NSEs have on SDGs. Only those most impacted are shown.

- SDG 1 (No Poverty), through the loss of assets, income, and livelihoods.

- SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), through the reduced functionality of healthcare facilities.

- SDG 4 (Quality Education), through the disruption of educational continuity.

- SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), as unequal access to mitigation and recovery resources deepens disparities.

- SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), due to impaired urban functionality and reduced resilience.

- SDG 13 (Climate Action), given the environmental costs of reconstruction and waste generation.

This target-based qualitative mapping approach enables the identification of specific SDG targets where the mitigation of NSE vulnerabilities can yield co-benefits across sectors. The framework thus positions NSE risk reduction not only as an engineering concern but as a strategic enabler of sustainable development, highlighting its cross-sectoral relevance to the 2030 Agenda.

3. Non-Structural Elements: Why Are They Relevant?

In earthquake engineering, the term non-structural elements (NSEs) pertains to building components or contents that are not included in the primary structural system designed to resist seismic forces. The definition and identification of NSEs in a building have undergone significant evolution, beginning with the pioneering description contained in the third edition of the FEMA-74 guide [14] as a list of items to the latest edition, FEMA E-74 [15], in which they are defined as “all building parts and contents except for those previously described as structural. These components are generally specified by architects, mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, and interior designers. However, they may also be purchased and installed directly by owners or tenants after the construction of a building has been completed. In commercial real estate, the architectural and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems may be considered a permanent part of the building and belong to the building owner; the furniture, fixtures, equipment, and contents, by contrast, typically belong to the building occupants”. According to [15], NSEs are categorized into three groups: (1) architectural components, (2) mechanical, electrical, and plumbing components, (3) furniture, fixtures, and equipment and contents. Table 1 summarizes a list of NSEs for each category.

Table 1.

List of NSEs for the three categories defined by FEMA-E74 [15]. The list of non-structural components is constantly evolving, as new technologies alter our built environment.

Most architectural elements are not intended to be load-bearing structural elements but are usually attached to the structural framing. Often, they are non-permanent, like partitions and ceilings, which are in turn moved or relocated to meet the needs of the house tenants. Recent studies discuss the role of some of these architectural components (i.e., infill walls). They conclude that these NSEs may affect the behavior of a building during a seismic event and should be included in the seismic design [16,17,18]. NSEs do not directly contribute to the load-bearing structure of a building and, in the case of an earthquake, the damage to NSEs does not affect the building’s stability; nevertheless, they can be adversely affected, potentially leading to damage, failure, and posing risks to the safety of occupants [19]. In a survey conducted to assess the usability of school buildings following the 2016 events in Central Italy, Di Ludovico et al. [20] found that after the first shock of 24 August, 164 school buildings had suffered no structural damage but severe NSE damage, and they were to be evaluated under usability category B (the building is temporarily unfit for use, necessitating short-term repairs to restore usability), C (the building is partially unfit for use), or deemed completely unusable. In this context, it also needs to be considered that damage to brittle partitions often begins at drift levels smaller than those required to induce damage in the structure: in practice, damage to NSEs can occur even for low-magnitude seismic events and in cases in which the building remains structurally intact [21].

Taghavi and Miranda [8] underline that NSEs play a crucial role in performance-based earthquake engineering. These elements cause operational failures and damage, particularly during low-to-moderate earthquakes [22], which are the most frequent seismic events. Regardless of the amount of damage caused, economic losses can be produced from a temporary loss of function of the building. In addition, damaged or falling NSEs can pose serious risks to human safety, causing injuries or fatalities, and can compromise the ability to perform the intended functions of a facility.

With few exceptions, NSEs represent a major portion of the total cost of the building [8,9,10,11,12] and thus a large portion of the potential loss to owners, occupants, and insurance companies. A particular category is represented by “valuable NSEs”, defined as NSEs that, due to their economic, cultural, or strategic importance, cannot be damaged in the case of seismic events (e.g., medical devices, plants, data servers, artistic assets—both exposed or stored) and, therefore, have to be protected [23]. In fact, it must be underlined that, beyond their economic value, in most cases, the term “valuable” applies to significant cultural, historical, and esthetic value that is separate from their physical structure, contributing to urban identity, collective memory, and a sense of place. Their value is determined by the meaning people give them, and thus by their societal values. Just to give an example, museum artifacts like statues and busts are assets of the world’s cultural heritage and, thus, are priceless, valuable NSEs [24].

Recent years have seen growing interest in the seismic assessment of NSEs, e.g., [22,25,26,27,28]. Kaw et al. [29] provide a thorough literature review for quantifying, classifying, and suggesting improvements in the building codes of seismic risk of non-structural elements. Parallel to these technical studies, research has increasingly focused on raising awareness of the importance of NSEs in ensuring safety during earthquakes [30,31,32,33].

It is then evident that NSEs impact various aspects of individuals’ lives and, more broadly, those of a community. Indeed, the occurrence of damage to non-structural elements can have repercussions on the economy, health, and the sustainability of communities. These factors are all addressed within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Thus, it is reasonable to discuss how much these factors affect the attainment of the SDGs and if and how far the mitigation of these can contribute to the SDGs, which will be introduced in the Discussion section of this paper.

4. Sustainable Development Goals Most Affected by NSE Vulnerability

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030, all people enjoy peace and prosperity [13]. The aim of these goals is to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. All stakeholders’ governments, civil society, and the private sector are expected to contribute to the implementation and success of the 17 goals through nationally owned and country-led sustainable development strategies. A total of 169 specific, measurable targets are associated with the SDGs, and they provide a sound framework for action across global challenges like poverty, hunger, health, education, gender equality, climate change, and responsible consumption, aiming to “leave no one behind”.

There is an unexplored link between SDGs and earthquakes that also passes through NSEs. Earthquakes can impact communities at risk by causing life loss, disrupting urban infrastructure, and displacing populations. They affect economic losses, hindering the progress of various development targets. Such impacts on communities at risk occur in different ways. Heavy disruption, structural failure, and life losses are caused by strong, yet not frequent, earthquakes. However, earthquakes can impact people’s lives in a subtler way in response to low and moderate earthquakes. These are more frequent, affect large areas, far away from the epicenter of strong earthquakes, and are relevant to the vulnerability of NSEs.

Seismic risk is thus a significant obstacle to achieving some of the Sustainable Development Goals (Figure 1), especially those dealing with ending poverty (SDG 1), good health and well-being (SDG 3), quality education (SDG 4), decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), reducing inequalities (SDG 10), and developing sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11). It may affect even actions to contrast global warming (SDG 13). In the following, we will address how earthquakes affect the achievement of these SDGs. We will examine the targets of each SDG that specifically relate to the interaction with NSEs. We must bear in mind that the SDGs suggest wide-ranging actions, and not all of these are applicable to natural hazards, including earthquakes. As an example, Table 2 lists the targets for SDG1: some of them, marked in bold, may partially gain from increased attention to NSEs.

Table 2.

SDG 1 targets. Those in bold could potentially benefit, at least in part, from enhanced attention to NSEs.

SDG 1 focuses on the eradication of poverty worldwide by 2030, aiming to eliminate extreme deprivation and improve access to essential services. However, over 700 million people remain in extreme poverty, struggling to secure access to health, education, water, and sanitation. In such contexts, disaster preparedness is often deprioritized, and earthquake risk may not be perceived as an urgent issue [34]. Data from 100 reporting countries show that, in 2023, the largest part of government spending on essential services was devoted to education, health, and social protection [13], yet a 20-point gap separates advanced and developing economies [35] in terms of expenditure on these essential services [13]. Disaster preparedness is not classified as an essential service and tends to be overlooked, particularly in areas affected by poverty [34].

This lack of preparedness is compounded by the underestimated vulnerability of non-structural elements, whose seismic fragility can cause severe functional disruptions and significant economic losses. Repair and replacement costs impose financial burdens that disproportionately affect low-income countries, some of which lie along plate boundaries, where large populations are exposed to high seismic hazards. Here severe structural damage may occur in the event of strong earthquakes but NSE failure, occurring even during moderate shaking, may extend disruption well beyond the areas affected by structural collapse. Infrastructure functional disruptions can interrupt small businesses and essential services, reducing household incomes and local economic productivity. The challenge is further magnified by the fact that more than 50% of the world’s urban population currently lives in slums, informal settlements, or inadequate housing [8], conditions that significantly heighten vulnerability and put the 2030 goal even further out of reach.

Targets 1.1 and 1.2 of SDG 1 (see Table 2), which focus on eradicating extreme poverty and reducing the proportion of people living in poverty, only marginally benefit from enhanced attention to NSEs. In contrast, target 1.5, which aims to strengthen resilience (see Table 2), can benefit substantially from such measures, as reducing NSE vulnerability directly lessens exposure to economic and social shocks, helping to prevent setbacks in poverty alleviation efforts.

SDG 3 emphasizes ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all, with target 3.D specifically aiming to “Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks”. The target promotes a proactive approach, focusing on preventing and mitigating health risks before they become large-scale emergencies. This preparedness may also be improved by addressing NSEs, as will be discussed later. Earthquakes represent a critical challenge to the achievement of SDG3, as they can compromise hospitals and healthcare facilities [36,37]. These facilities are critical infrastructures, and their functionality depends largely on NSEs, including medical equipment, electrical and mechanical systems, and internal utilities. Damage to these components, even in structurally sound buildings, can severely disrupt essential medical services. Such disruptions hinder the capacity of hospitals to deliver urgent care during the emergency phase, directly affecting the effectiveness of response operations. At the same time, prolonged unavailability of healthcare services undermines the recovery process, as communities remain without the medical support needed to restore normality and address post-disaster health needs. These cascading impacts highlight that reducing NSE vulnerability strengthens [37] the resilience of healthcare facilities, ensuring that essential medical services continue to function during emergencies. By minimizing service disruptions, it directly supports timely emergency response and accelerates community recovery, thereby contributing significantly to the achievement of SDG 3. Enhancing hospital functionality in seismic contexts is therefore a cornerstone for advancing SDG 3, ensuring that the right to health and well-being is protected across both the response and recovery phases of disaster management.

SDG 4 encompasses key measures aimed at ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education, including the guarantee of free and compulsory schooling, the expansion of the teaching workforce, the improvement of basic educational infrastructure, and the integration of digital transformation as a core component of learning. It is well known that a student informed about natural hazards will be a resilient citizen. Education is simultaneously a requirement and a means to obtain specialized training in the realm of natural phenomena. Among the goals of SDG4, 4.7 particularly emphasizes education for sustainable development and lifestyle, creating a connection between the educational system and preparedness.

SDG 10 emphasizes reducing inequalities, focusing on income, opportunity, and access to resources. Seismic damage to NSEs disproportionately affects those with fewer resources, who are least able to invest in mitigation or recovery, and this amplifies socio-economic disparities, thereby directly undermining the targets 10.1 (by 2030, progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40% of the population at a rate higher than the national average) and 10.3 (ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard). Disaster preparedness is frequently framed as a privilege of wealthier communities, leaving marginalized groups without adequate coping capacity [34]. By reducing NSE vulnerabilities through inclusive seismic risk reduction strategies, disadvantaged populations are better protected, which mitigates disproportionate losses and supports the narrowing of socio-economic gaps. Safety is thereby a universal right, and inclusive mitigation not only reduces poverty but also prevents the amplification of inequalities in the aftermath of disasters.

SDG 11 aims at building infrastructures that can withstand natural disasters and adapt to the impacts of climate change; thus, integrating seismic risk mitigation and reducing the vulnerability of non-structural elements into urban planning is crucial for achieving SDG 11 and ensuring long-term sustainability. These are envisaged by almost all targets of the SDG 11, where the words safe (11.1, 11.2, 11.4, 11.7), vulnerable situations (11.2, 11.5), resilience to disasters (11.B), and sustainable (11.2, 11.3, 11.C) may be found.

The SDG 11 involves including NSEs in building codes, retrofitting existing structures, and developing early warning systems to increase the capacity of communities to cope with seismic hazards. Some of these actions have already been undertaken. Summaries of many important aspects of the seismic behavior of non-structural building elements as well as the evolution of research and code efforts in the last 30 years can be found in Soong Filiatrault and Christopoulos and Filiatrault et al. [38,39,40]. It must be underlined that damage to non-structural elements does not depend solely on the magnitude of the event but rather on how these elements are incorporated into the living environment and how they are managed by the property owners. This implies that even if vulnerability is reduced, the issues regarding building contents during an earthquake should still be addressed and resolved to increase the resilience of communities at risk.

SDG 13 calls for urgent action to combat climate change and its consequences. However, current mitigation and adaptation strategies largely neglect the need to address increased seismic hazards in the context of a warming climate. NSE seismic damage interacts with climate action in two ways.

First, seismic events often necessitate demolition and reconstruction, generating greenhouse gas emissions from debris removal, material production, and construction activities [41,42,43]. It must be mentioned that the construction sector is the main source of greenhouse gas emissions [44]. Building construction is responsible for 40% of the world’s waste (by volume) and 20–35% of global warming and smog [45]. In such a frame, debris management and reconstruction after an earthquake heavily contributes to CO2 emissions, even if it only applies to NSEs. Using sustainable or recycled materials in buildings and adopting low-carbon retrofitting practices [46] align seismic risk reduction with the climate action envisaged in targets 13.1 (strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries) and 13.2 (integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning).

Second, changes in glacial mass and surface loads induced by climate change can influence crustal stress and seismicity [47], potentially increasing the frequency and severity of events that damage NSEs.

5. Discussion

Natural disasters represent a major obstacle to sustainable development, as they undermine the social, economic, and environmental foundations upon which progress relies. Earthquakes, in particular, account for more than a quarter (25.6%) of global economic disaster losses [2] and their consequences often extend across generations [3,48]. The burden is disproportionately concentrated in developing countries [35,47], where limited resources, weaker governance structures, and higher exposure combine to magnify the disruption. Unlike other disasters with slower dynamics, seismic events generate abrupt shocks that trigger immediate causalities, widespread destruction of infrastructure, and prolonged disruptions to essential services. These cascading effects directly compromise the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations in 2015, which provide a comprehensive framework to eradicate poverty, reduce inequalities, and promote resilience for future generations.

Earthquakes represent a systemic challenge to these objectives, not only through structural collapse but also through the consequential damage to the non-structural elements of buildings. The vulnerability of NSEs remains an underestimated issue in disaster risk reduction, largely because building codes worldwide prioritize life safety and structural integrity. As a result, NSE failure is often perceived as less urgent, despite its far-reaching implications. Since NSEs can sustain significant damage even under moderate shaking, their failure occurs more frequently than structural collapse and generates cascading consequences, such as economic losses, service disruptions, and social instability, that directly challenge sustainable development.

The implications for the SDGs are profound. SDG 1 (No Poverty) is undermined when households lose homes, jobs, and assets due to seismic damage, often pushing vulnerable families into cycles of long-term poverty. Similarly, SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) is jeopardized when hospitals and healthcare facilities, whose operability often depends heavily on non-structural systems such as medical equipment, oxygen lines, or electrical installations, are rendered inoperative during emergencies [22,25,27,28]. Evidence from recent seismic events shows that while buildings may survive structurally, damage to NSEs frequently disrupts hospital operations, reducing their capacity to deliver urgent care and to sustain recovery in the aftermath [22,25,27,28]. Effectively mitigating NSE seismic damage generates cross-cutting benefits that directly support multiple SDGs by maintaining essential services and enhancing community resilience.

Inclusive strategies to reduce NSE seismic vulnerability also contribute to SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by ensuring that protective measures are accessible to low-income and marginalized households. Because many NSE interventions require minimal financial resources or technical skills, they can be widely adopted, reducing disparities in disaster vulnerability. By increasing the seismic capacity of personal property and livelihoods, these measures help break disaster–poverty cycles and prevent economic shocks from becoming long-term structural disadvantages. NSE risk reduction is therefore not merely a technical concern but a strategic enabler of sustainable and equitable development, as it protects households, communities, and local economies.

Efforts to improve education and public awareness of NSE risks also support SDG 3 (Good Health), SDG 4 (Quality Education), and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). Integrating targeted communication and educational tools facilitates the comprehension of NSE-related risks and promotes understanding NSE relevance and encourages actionable responses. Integrating NSE-focused seismic safety modules into formal and informal education, especially in schools and public institutions, enables the early and widespread dissemination of knowledge [31]. To maximize these benefits, the reduction in NSE vulnerability must be systematically integrated into disaster risk reduction (DRR) and sustainable development policies. National building codes should mandate standards for NSE safety, while inspection and certification procedures should explicitly address both structural and non-structural components. Educational initiatives must be both linguistically and culturally inclusive, reducing barriers to access and participation. Collaboration with civil protection organizations, schools, and local authorities is critical to reach underserved populations and ensure that the benefits of risk reduction are distributed equitably.

Educational programs and community-based initiatives complement regulatory frameworks by raising awareness of low-cost mitigation measures that households and small businesses can implement. Aligning NSE mitigation with international frameworks such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and SDG monitoring enables governments to systematically track progress and mobilize resources. Financing mechanisms, such as micro-grants, insurance incentives, and subsidies, can further encourage the adoption of best practices, especially among vulnerable populations. Collectively, these interventions rise NSE risk reduction from a neglected technical issue to a cornerstone of resilient, inclusive, and sustainable development strategies.

Even simple, low-cost interventions, such as anchoring furniture or securing equipment, can yield disproportionately high benefits by reducing potential economic losses and preventing injuries. These measures are particularly effective in schools and community facilities, where they also foster public engagement and promote a culture of preparedness. By increasing the seismic resistance of hospitals, schools, and other critical facilities, NSE risk reduction enhances the resilience of communities, ensuring the continuity of essential services, enabling faster and more effective response and recovery, and ultimately strengthening social stability.

Addressing NSE risk also strengthens urban resilience within the broader context of climate change, aligning with SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Buildings must be resistant not only to structural collapse but also to cascading failures of non-structural components during ground shaking. Integrating NSE safety into building audits, climate adaptation strategies, and emergency preparedness programs enhances the overall resilience of urban environments.

The implementation of vulnerability reduction measures requires dedicated resources, with success influenced by many factors, including the urban layout, the construction materials and practices, and the age of the building. Consequently, fulfilling SDG-related objectives in the context of seismic risk entails substantial national investments, with variation depending on geological factors.

Seismic preparedness is part of a comprehensive approach to sustainable, livable, and adaptive cities, underscoring the interconnection between disaster risk reduction, social equity, and broader sustainability objectives. Community-based initiatives that link risk awareness to daily environments empower individuals to reduce vulnerability at home, work, and in public spaces, establishing a long-term culture of risk awareness and making seismic preparedness a shared societal value from early education onward. Many NSE mitigation measures can be implemented at little or no cost by property owners themselves. Citizen engagement, when opportunely guided, can effectively reduce NSE seismic vulnerability through do-it-yourself (DIY) actions. For example, a simple and commonly used strategy to secure small and light NSEs is practiced based on common sense. This strategy is largely applicable to objects that cannot be physically connected with the structural elements, e.g., small-sized glass crockery, bottles on kitchen shelves, and books on library shelves. For instance, a string or a front panel plate can be provided in racks or shelves to hold a group of crockery on cupboards, bottles on kitchen shelves, or books on library shelves to prevent them from falling [49].

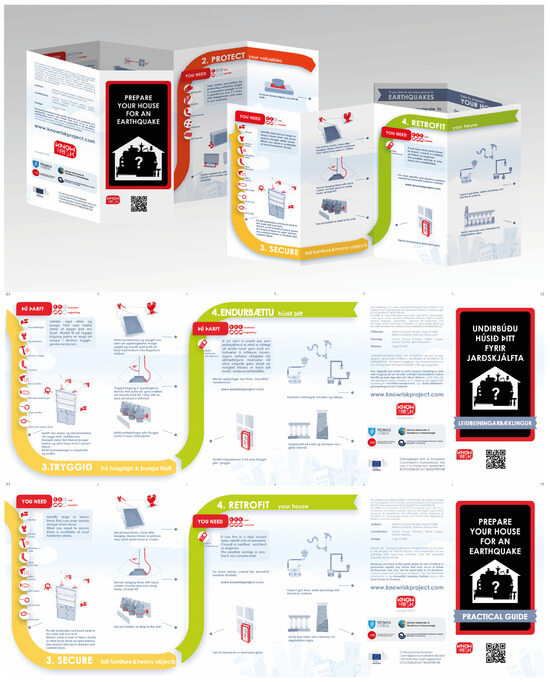

However, citizen engagement is partially hindered by resistance since often individuals tend to underestimate future risks or believe that preventive actions are not cost-effective and do not provide tangible, immediate benefits. Such skepticism about prevention is deeply rooted in society and is partly fostered by the understanding that, typically, earthquakes, notably the intense ones, are uncommon events, sometimes distributed across several generations. One important action against motivational barriers is to prioritize immediate gratification over potential long-term savings or benefits. In such a goal, state economic incentives or insurance companies’ policies could play an important role. Above all, since insufficient awareness of potential problems or a lack of access to training and information can prevent the adoption of best practices, it is crucial to implement actions aimed at raising awareness and educating citizens about risks, beginning from their school years. These are some of the objectives of the KnowRISK [31,50,51] project, in the frame of which educational tools, practical guides, and serious games to inform citizens about mitigating NSE-related earthquake risks in three highly seismic European countries, namely Portugal, Iceland, and Italy, were developed. The Practical Guide for Citizens (Figure 2), one of the project’s key deliverables, is particularly remarkable as it proposes mitigation actions that can be partially carried out on a do-it-yourself basis. It outlines four levels of intervention, organized by rising costs and the necessary technical expertise. They are cost-free actions (rearranging furniture and belongings), minimal-skill measures (protective films, securing straps, curtains), moderate-skill measures (anchoring heavy furniture, mirrors, chandeliers), and professional-level interventions (securing chimneys, railings, balconies). Adopting the guide’s recommendations can decrease damage to non-structural elements, which result not only from ground acceleration but also from structural deformation [52]. Such damage can account for up to 85% of the total construction cost of commercial buildings, and in some cases, losses associated with NSEs have even exceeded those due to structural damage [53]. Thus, in an optimal case, mitigating the effects on NSEs as suggested by the guide can reduce 60% to 80% of the total loss. This result in turn has a considerable impact on the SDGs if actions are undertaken by the whole community. Mitigating or avoiding NSE damage can reduce or even eliminate the loss: the economic balance is always positive even considering the costs for materials/tools/retrofitting.

Figure 2.

The practical guide to support citizens in reducing the seismic vulnerability of NSEs in their households. It assumes that a building which disregards non-structural elements is exposed to risk (high vulnerability, red section). The vulnerability decreases as actions to mitigate NSE damage are undertaken (in three steps from orange to green). The guide has been published in four languages (English, Italian, Icelandic, Portuguese). (Top): Appearance of the whole guide; (middle): the Icelandic version of the last two steps of the path (yellow and green); (bottom):the same pages in English. The written content is shortened to promote the observation of the images.

6. Conclusions

The Sustainable Development Goals represent a long-term commitment to ensuring that future generations inherit a safer, healthier, inclusive, and more equitable world. Within this framework, mitigating damage to non-structural elements after an earthquake emerges as a highly cost-effective pathway to strengthen resilience and accelerate progress towards specific SDGs. Although often overlooked, NSEs are directly tied to the safety of buildings’ occupants, the functionality of critical infrastructures, and the continuity of essential services. Such mitigation can often be achieved through best practices that require minimal resources. They primarily influence the advancement of goals such as poverty reduction (SDG 1), good health and well-being (SDG 3), quality education (SDG 4), reduced inequalities (SDG 10), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), and climate action (SDG 13).

Mitigation strategies can range from low-cost, do-it-yourself actions to professional retrofitting efforts, but their shared value lies in their accessibility. Many effective measures, such as rearranging furniture, applying protective films, or anchoring shelves, require minimal resources and can be implemented by households without specialized expertise. This democratization of risk reduction ensures that even vulnerable communities can take meaningful steps toward improving safety, thereby simultaneously contributing to resilience and equity.

Education plays a pivotal role in scaling these benefits. Risk awareness campaigns and targeted learning modules help transform abstract knowledge into actionable behavior, creating a virtuous cycle of preparedness [54,55,56]. The KnowRISK project systematically addressed this challenge, providing a set of tools designed to promote preventative actions.

Estimating the long-term impact of educational, community-based interventions remains challenging, as benefits often become measurable only after subsequent seismic events or across extended periods. Nevertheless, investments in NSE mitigation are not only justified but urgently required, particularly in seismically active low- and middle-income regions where vulnerability is highest.

Ultimately, every action taken to mitigate the effects of earthquakes contributes to building societal resilience. In the specific case of NSEs, these actions carry the additional advantage of reinforcing multiple SDGs at once, bridging disaster risk reduction with broader global development objectives. By integrating NSE-focused mitigation into education, urban planning, and public policy, societies can enhance safety, reduce inequalities, protect critical infrastructures, and minimize environmental costs of post-disaster reconstruction. In this sense, seismic risk mitigation is not merely a technical objective, but a strategic contribution to sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and G.M.; investigation, S.S., G.M. and E.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, S.S., G.M. and E.E.; visualization S.S. and G.M.; supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to two anonymous reviewers for providing comments that greatly improved the paper. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT-5 for language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NSEs | Non-Structural Elements |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000–2019); UN: New York, NY, USA, 2020; 30p. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2025: Resilience Pays: Financing and Investing for our Future; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; 253p, ISBN 9789211576740. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, M.L.; Tsionis, G. National seismic risk assessment: An overview and practical guide. Nat. Hazards 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musson, R.M.W. The use of Monte Carlo simulations for seismic hazard assessment in the United Kingdom. Ann. Geophys. 2000, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman, A.; Douglas, J.; Tubaldi, E. The assessment of probabilistic seismic risk using ground-motion simulations via a Monte Carlo approach. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 6833–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burak, Y.; Erkut, S.; Onur, O. Earthquakes and Structural Damages. In Earthquakes-Tectonics, Hazard and Risk Mitigation; Zouaghi, T., Ed.; Intechopen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspari, M.; Fabris, M.; Saler, E.; Donà, M.; da Porto, F. Enhancing Asset Management: Rapid Seismic Assessment of Heterogeneous Portfolios. Buildings 2025, 15, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.; Miranda, E. Response Assessment of Nonstructural Building Elements; Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, N.; Kanda, J. Estimation of Failure Costs at Various Damage Statuses. In Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting of Architectural Institute of Japan; B-1, Kanto; Building Research Institute: Tsukuba, Japan, 1997; pp. 75–76. [Google Scholar]

- State of Hawaii, Department of Defense. Earthquake Hazards and Estimated Losses in the county of Hawaii. 2005. Available online: https://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/op/czm/initiative/hazard/earthquake_hazards_hawaii_county.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- González Herrera, R.; Gómez Soberón, C. Methodology to evaluate the participation percentage of the contents, structural and non structural elements in the loss estimation in masonry houses in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Mexico. In Proceedings of the 14th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Beijing, China, 12–17 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes, R. Interstory Drift Design and Damage Control Issues. Struct. Des. Tall Build. 1995, 4, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025; Revision August 2025; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA 74. Reducing the Risks of Nonstructural Earthquake Damage: A Practical Guide; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1994.

- FEMA E-74. Reducing the Risks of Nonstructural Earthquake Damage—A Practical Guide, 4th ed.; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Del Gaudio, C.; De Risi, M.T.; Ricci, P.; Verderame, G.M. Empirical drift-fragility functions and loss estimation for infills in reinforced concrete frames under seismic loading. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 17, 1285–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari, M.; Donà, M.; da Porto, F. Analytical Model for Estimating the Out-of-Plane Behaviour of Masonry. In IB2MaC 2024, Proceedings of the 18th International Brick and Block Masonry Conference, Birmingham, UK, 21–24 July 2024; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Milani, G., Ghiassi, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 613, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, F.; Manfredi, V.; Masi, A.; Salvatori, A.; Vona, M. Performance of non-structural elements in RC buildings during the L’Aquila, 2009 earthquake. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 9, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, A.; Fanning, P.J. Non-structural elements and the dynamic response of buildings: A review. Eng. Struct. 2019, 187, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ludovico, M.; Digrisolo, A.; Graziotti, F.; Moroni, C.; Belleri, A.; Caprili, S.; Carocci, C.; Dall’Asta, A.; De Martino, G.; De Santis, S.; et al. The contribution of ReLUIS to the usability assessment of school buildings following the 2016 central Italy earthquake. Boll. Geofis. Teor. Appl. 2017, 58, 353–376. [Google Scholar]

- Zito, M.; Nascimbene, R.; Dubini, P.; D’Angela, D.; Magliulo, G. Experimental Seismic Assessment of Nonstructural Elements: Testing Protocols and Novel Perspectives. Buildings 2022, 12, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sarno, L.; Magliulo, G.; D’Angela, D.; Cosenza, E. Experimental assessment of the seismic performance of hospital cabinets using shake table testing. Earthquake Engng Struct. Dyn. 2019, 48, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, L.; Bovo, M.; Rocca, I.; Saetta, A.; Savoia, M. Seismic safety of valuable non-structural elements in RC buildings: Floor Response Spectrum approaches. Eng. Struct. 2020, 205, 110081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragiadakis, M.L.; Di Sarno, A.; Saetta, M.G.; Castellano, I.; Rocca, S.; Diamantopoulos, V.; Crozet, I.; Politopoulos, T.; Chaudat, S.; Vasic, I.E.; et al. Seismic response assessment and protection of statues and busts. In Proceedings of the 1st ArCo—Art Collections Cultural Heritage, Safety and Innovation International Conference, Firenze, Italy, 28–30 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angela, D.; Contento, A.; Kampas, G.; Magliulo, G. Seismic Response of Rocking-Dominated Nonstructural Elements: A Comprehensive Review. J. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, D.; Perrone, D.; Filiatrault, A. Influence of gravity load trapezes in the seismic performance of suspended piping systems. Eng. Struct. 2025, 333, 120188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, G.; D’Angela, D.; Bonati, A.; Coppola, O. Cyclic behavior of screw connections in plasterboard partitions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 484, 141780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, G.; D’Angela, D. Seismic response and capacity of inelastic acceleration-sensitive nonstructural elements subjected to building floor motions. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 53, 1421–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaw, A.; Pal, S.; Mitra, S. Evaluation of Seismic Behavior of Non-structural elements in Building. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2025, 70, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidarich, S.; Crescimbene, M.; Musacchio, G.; Sestito, M.G.; Reitano, D.; D’Angela, D.; Perrone, D.; Aiello, M.A.; Magliulo, G. Seismic risk perception of non-structural elements in Italian hospitals: Pilot studies. Bull. Geophys. Oceanogr. 2025, 66, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.A.; Meroni, F.; Azzaro, R.; Musacchio, G.; Rupakhety, R.; Bessason, B.; Thorvaldsdottir, S.; Lopes, M.; Oliveira, C.S.; Solarino, S. What scientific information on the seismic risk to non-structural elements do people need to know? Part 1: Compiling an inventory on damage to non-structural elements. Ann. Geophys. 2021, 64, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Fu, H.; Qu, Z. Full-scale shake table testing method for seismic assessment of nonstructural elements using a universal testbed and a standard building-specific loading protocol. Eng. Struct. 2025, 343, 120969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosapoor, M.; Bessason, B.; Hrafnkelsson, B.; Rupakhety, R.; Bjarnason, J.O.; Erlingsson, S. Damage-informed seismic fragility of non-structural elements in South Iceland: A Bayesian hierarchical approach. Eng. Struct. 2025, 338, 120504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.; Marlowe, J.; Johnston, D. Get prepared: Discourse for the privileged? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 25, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, C. Why Do People Die in Earthquakes? The Costs, Benefits and Institutions of Disaster Risk Reduction in Developing Countries; Policy Research Working Paper 4823; The World Bank Sustainable Development Network Finance Economics and Urban Department: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; 40p. [Google Scholar]

- Morán-Rodríguez, S.; Novelo-Casanova, D.A. A methodology to estimate seismic vulnerability of health facilities. Case study: Mexico City, Mexico. Nat. Hazards 2018, 90, 1349–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, S.; Shunshun, P.; Changhai, Z.; Peng, Y. Research Progress on Seismic Resilience of Hospitals. Ind. Costr. 2024, 54, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Soong, T.T. Seismic behavior of nonstructural elements-state-of-the-art-report. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Vienna, Austria, 28 August–2 September 1995; pp. 1599–1606. [Google Scholar]

- Filiatrault, A.; Christopoulos, C. Guidelines, Specifications, and Seismic Performance Characterization of Nonstructural Building Components and Equipment; Report PEER 2002/05; Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; p. 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiatrault, A.; Perrone, D.; Merino, R.J.; Calvi, G.M. Performance-Based Seismic Design of Nonstructural Building Elements. Journ. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 25, 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Ahmed, H.A.; Shahzada, K.; Li, Y. Vulnerability of Non-Structural Elements (NSEs) in Buildings and Their Life Cycle Assessment: A Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhabrinna; Davies, R.J.; Pratama, M.M.A.; Yusuf, M. BIM adoption towards the sustainability of construction industry in Indonesia. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 195, 06003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manjunatha, M.; Preethi, S.; Malingaraya; Mounika, H.G.; Niveditha, K.N. Ravi Life cycle assessment (LCA) of concrete prepared with sustainable cement-based materials. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 3637–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Marin, P.; Chiusi, B.; Thyholt, M.; Rinholm, H.; Resch, E.; Lausselet, C. Greenhouse gas emissions of buildings designed for disassembly across multiple life cycles. Build. Environ. 2025, 282, 113247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme; Yale Center for Ecosystems + Architecture. Building Materials and the Climate: Constructing a New Future; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Costs of Inaction of Environmental Policy Challenges Report; ENV/EPOC(2007)17/REV2; OECD: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sauber, J.; Rollins, C.; Freymueller, J.T.; Ruppert, N.A. Glacially Induced Faulting in Alaska. In Glacially-Triggered Faulting; Steffen, H., Olesen, O., Sutinen, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- De Lucia, M.; Benassi, F.; Meroni, F.; Musacchio, G.; Pino, N.A.; Strozza, S. Seismic disasters and the demographic perspective: 1968, Belice and 1980, Irpinia-Basilicata (southern Italy) case studies. Ann. Geophys. 2020, 63, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, C.V.R.; Goswami, R.; Vijayanarayanan, A.R.; Ramancharla, P.; Mehta, V. Introduction to Earthquake Protection of Non-Structural Elements in Buildings; Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority Government of Gujarat: Gandhinagar, India, 2012; 176p. [Google Scholar]

- Solarino, S.; Ferreira, M.A.; Musacchio, G.; Rupakhety, R.; O’Neill, H.; Falsaperla, S.; Vicente, M.; Lopes, M.; Oliveira, C.S. What scientific information on the seismic risk to non-structural elements do people need to know? Part 2: Tools for risk communication. Ann. Geophys. 2021, 64, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsaperla, S.; Musacchio, G.; Ferreira, M.A.; Lopes, M.; Oliveira, C.S. 2021. Dissemination: Steps towards an effective action of seismic risk reduction for non-structural damage in the KnowRISK project. Ann. Geophys. 2021, 63, SE328. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.A.; Oliveira, C.S.; Lopes, M.; de Sá, F.M.; Musacchio, G.; Rupakhety, R.; Reitano, D.; Pais, I. Using Non-Structural Mitigation Measures to Maintain Business Continuity: A Multi-Stakeholder Engagement Strategy. Ann. Geophys. 2021, 64, SE324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiatrault, A.; Sullivan, T. Performance-based seismic design of non structural building components: The next frontier of earthquake engineering. Earthq. Engin. Engin. Vibr. 2014, 13, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musacchio, G.; Solarino, S. Seismic risk communication: An opportunity for prevention. Boll. Geofis. Teor. Appl. 2019, 60, 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Postiglione, I.; Masi, A.; Mucciarelli, M.; Lizza, C.; Camassi, R.; Bernabei, V.; Piacentini, V.; Chiauzzi, L.; Brugagnoni, B.; Cardoni, A.; et al. The Italian communication campaign “I do not take risks-earthquake”. Boll. Geofis. Teor. Appl. 2016, 57, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, C.; Scolobig, A.; Abderhalden, J.; Weyrich, P.; Stoffel, M. Risk communication policies and strategies in Nepal and Switzerland: A comparative study. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 129, 105773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).