Abstract

This study discusses the issue of designing reverse curves, i.e. a geometric system consisting of two circular arcs (usually with different radii), directed in opposite directions and directly connected to each other. The design is performed in an appropriate local Cartesian coordinate system. The origin of this system is located at the point of intersection of adjacent main directions of the route. Unlike other geometric situations, reverse curves have three main directions, which significantly complicate the design process. The initial values of the radii of the reverse arcs must correspond to the existing system of main directions. The introduction of transition curves causes these radii to decrease; their values are determined iteratively. A set of formulas for creating a geometric system of reverse curves is presented. These formulas were used in the calculation example. A graph of the horizontal curvature of the track axis and a method for determining the possible train speed, both without the use of cant on an arc and with the use of cant, are shown. The presented procedure is universal and can be applied to other geometric situations involving the design of reverse curves. It is also necessary to emphasize the practical usefulness of the discussed method not only in the design process, but also to pay attention to the cognitive value of the article.

1. Introduction

In the field of railways, numerous research works are currently being carried out, among which the following can be distinguished: high-speed railways (e.g., [1,2,3,4,5]), rolling stock and its maintenance (e.g., [6,7,8]), and in the field of railway superstructure, the issue of interactions in the rail vehicle–track system (e.g., [9,10,11,12,13]). However, when it comes to designing track geometric layouts, there is a growing belief that conducting research on this topic is currently of less importance. This is undoubtedly due to the fact that for many years, design documentation for railways has been developed using commercial computer software [14,15]. Of course, such work is carried out [16,17,18,19], most often limited to such issues as transition curves [20,21,22,23] or railway turnouts [24,25,26,27].

Newly constructed railway lines are generally adapted to accommodate increased train speeds; in fact, a significant part of them are high-speed lines. However, the railway industry has a very long history. In terms of length, traditional lines, mostly built in the 19th century and still in operation today, still dominate. Undoubtedly, these lines would need to be adapted to modern requirements. This is particularly true for railway lines running through challenging terrain (e.g., mountainous terrain), which feature small horizontal arc radii and controversial geometric configurations, such as compound curves and reverse curves. Trains on these lines typically operate at low speeds. Improving this situation requires appropriate modernization efforts. Meanwhile, it seems that these lines do not have sufficient interest in research activities.

This article addresses the design of reverse curves, a geometric arrangement consisting of two consecutive circular arcs (usually with different radii), oriented in opposite directions and directly connected. These curves have existed since the dawn of railway engineering, but they create certain operational problems due to the rapid changes in curvature that occur on them. Subsequent advances in computational technology have also addressed them to a lesser extent. The design of reverse curves differs from other geometric arrangements in terms of their level of complexity. From a scientific perspective, there is relatively little interest in this problem; rather, the practical aspects of the issue are exposed [28].

The goal was also to be able to recreate (i.e., model) the existing geometric layout with reverse arcs in order to potentially correct the horizontal ordinates in the area where the circular arcs connect. It was, therefore, necessary to develop an effective design method that could be used not only to determine the coordinates of the new reverse curve but also to model the existing system (with a view to its subsequent modification).

It should be noted here that an analytical method for designing reverse arcs had already been developed and presented in [29]. It involved a model solution, i.e., creating a geometric system from scratch in which reversely directed circular arcs of different radii are connected by an appropriate transition curve. The classic reverse arc, in which the transition curve does not occur, was a special case in this method. Modification of the existing geometric system was not considered. However, it seems that this is most often the real problem to be solved.

In this paper, the solution to the problem is achieved analytically. The standard procedure of the analytical design method requires operating in a local coordinate system. In its initial versions [30], it was characterized by a lack of knowledge of the origin of this system relative to the corresponding global coordinate system (in Poland—with respect to flat coordinates—this is the national spatial reference system PL-2000 [31]). Full integration of both systems requires the design procedure to be carried out in the local coordinate system until the very end. The location of the origin of this system relative to the corresponding main point of the route, and its resulting coordinates in the global coordinate system, were determined only in the final phase of the procedure. This could have been the fundamental methodological objection to the discussed design method. For this reason, certain interpretation problems could also arise.

As it turns out, these difficulties can be avoided if the origin of the local coordinate system is located at the point of intersection of two main directions of the route, the Cartesian coordinates of which are known in the global system. This version of the analytical design method was presented in [32]; it is universal in nature and covers the areas where adjacent main directions of the railway route connect (both when using the same transition curves and when varying the lengths of these curves). In this paper, a similar approach was applied to the design of reverse curves.

However, reverse curves present a fundamental difference compared to most cases of analytical design methods. In geometric systems, two adjacent main directions of the route are most often identified and further processed (including the creation of a local coordinate system). With reverse curves, a third main direction appears, significantly complicating matters by limiting the versatility of the developed method. However, when it comes to the local coordinate system, the adopted principle has been retained: it is determined using two adjacent principal directions.

To some extent, reference was made to the method of modeling compound curves on railway lines presented in [33]. However, the third main direction, which appears in the reverse arch, does not allow for a universal design method to be presented in symbolic notation, as is the case with compound curves. Therefore, in each stage of the entire procedure, appropriate theoretical formulas had to be directly applied to a specific calculation example. At the same time, the possibility of extending the scope of applications of the developed method through an analogy was indicated.

2. Layout of the Main Directions of the Route

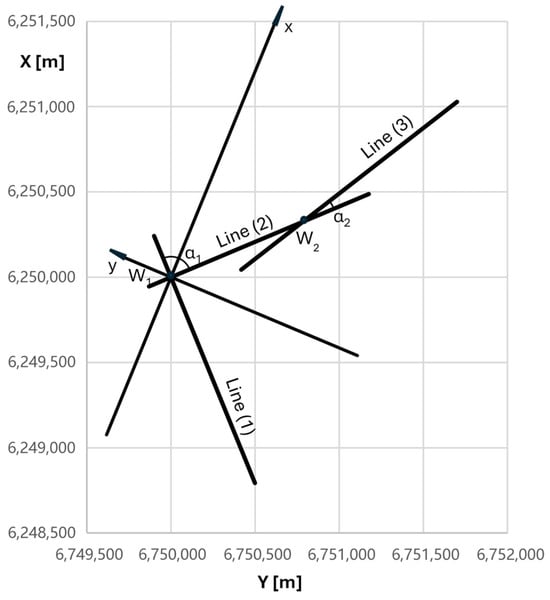

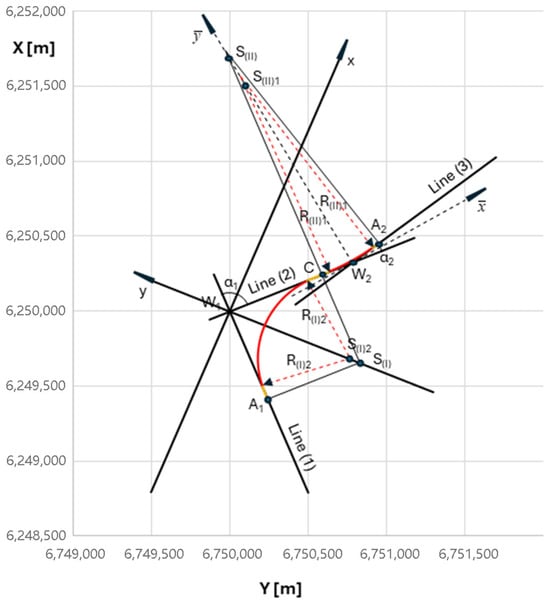

When considering the horizontal plane of a railway line, the geometric arrangement of reverse curves includes three consecutive main directions (labeled Line 1, Line 2, and Line 3), with the last direction (Line 3) deviating from the preceding direction (Line 2) in the opposite direction. These directions intersect at points W1 (Line 1 with Line 2) and W2 (Line 2 with Line 3). Figure 1 shows an example of the geometric situation of these main directions in the PL-2000 system. This system has an easting coordinate axis, Y, and a northing coordinate axis, X.

Figure 1.

The layout of the main directions of the route in the PL-2000 system.

In the analytical method of designing track geometric systems [32], basic computational operations are performed in the local coordinate system x, y. This system is defined by two intersecting main directions, arranged symmetrically; their intersection point is the origin of the system in question. In the case of modeling reverse curves, it was decided to maintain this principle, determining the local coordinate system (LCS) based on the location of Line 1 and Line 2. This is illustrated in Figure 1 by showing the position of the LCS axes in the PL-2000 system.

The equation of Line 1 in the PL-2000 system is as follows:

and the equation of Line 2 has the form:

where YW1 and XW1 are the coordinates of point W1, and Φ1 and Φ2 are the inclination angles of Line 1 and Line 2, respectively.

When adopting the appropriate numerical values in the calculation example, we were guided by the desire to obtain the greatest possible clarity of the geometric system in the LCS. Therefore, in this case, the coordinates of the main point YW1 = 6,750,000 m, XW1 = 6,250,000 m, and the slope of Line 1 equal to Φ1 = −3π/8 rad were assumed. The assumed angle of return of the route α1 = π/2 rad results in the slope of Line 2 equal to Φ2 = Φ1 + α1 = π/8 rad. The above data give the required values of the shifts YW1 and XW1 and the rotation angle β = Φ2 + α1/2 = 3π/8 rad, leading to the transformation of coordinates from the PL-2000 system to the local coordinate system. This is performed using the following formulas [34]:

The angle of inclination of the x-axis in the PL-2000 system is Φx = β = 3π/8 rad, so its equation is as follows:

The angle of inclination of the y-axis in this system is equal to Φy = β − π/2 = −π/8 rad; hence, the equation of this axis is

Since the assumed angle of the route at point W2 is equal to α2 = π/12 rad, the slope of Line 3 is Φ3 = Φ2 + α2 = π/6 rad. From the point of view of operations carried out in the LCS, it turned out to be advantageous to adopt the coordinates of the next principal point: YW2 = 6,750,783.938 m and XW2 = 6,250,324.718 m. The given data result in the equation of Line 3:

3. Local Coordinate System

It should be noted from the outset that the alignment of the main directions of the route in the PL-2000 coordinate system can vary greatly. However, after transformation to the local coordinate system, there are only two possible positions for the designed geometric system: under the x-axis, with negative ordinates and the convexity of the curvilinear elements directed upwards, and above the x-axis, with positive ordinates and the convexity of the curvilinear elements directed downwards [32]. Therefore, strictly speaking, both possible cases should be taken into account when determining the appropriate computational algorithms.

The main directions in Figure 1 indicate that in the LCS, the geometric system under consideration lies below vertex W1 and its ordinates are negative. This is the case that will be the subject of this article. The resulting formulas can also be applied to the system positioned above the x-axis, after making minor adjustments to the plus and minus signs.

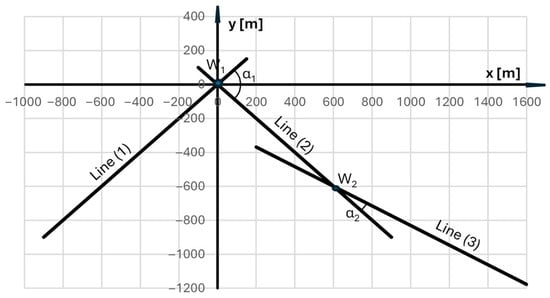

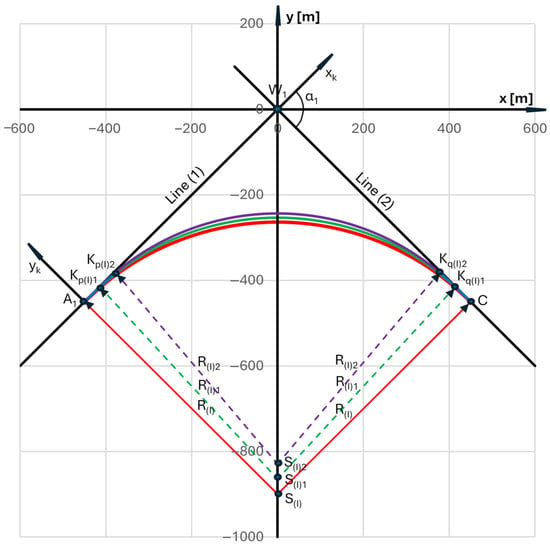

The transfer of the route’s main directions in Figure 1 to the local coordinate system is performed using Equations (3) and (4). This creates the situation shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The system of main directions of the route in the local coordinate system.

The origin of the local coordinate system, in which further detailed considerations will be conducted, is located at point W1(0,0), where Line 1 and Line 2 intersect. This is characteristic of the LCS used in the analytical method of designing geometric systems of the track [32].

The equations of the intersecting lines result from the angle of the route α1 for the first circular arc (marked as Arc I) and are as follows:

where φ1 and φ2 are the inclination angles of Line 1 and Line 2 in the LCS. In the given case, the assumed turning angle is α1 = π/2 rad.

The second circular arc (marked as Arc II) is directed opposite to the preceding arc and connects Line 2 with Line 3. Both lines intersect at point W2, the coordinates of which, xW2 and yW2, result from the coordinates YW2 and XW2. The equation of Line 3 results from the return angle α2 for the second circular arc:

where φ3 is the angle of inclination of Line 3 in the LCS. In the case under consideration, the coordinates of point W2 are xW2 = 600 m, yW2 = −600 m, and the angle of inclination of the line is equal to φ3 = −π/6 rad.

As can be seen, the numerical parameters of the considered system of the main directions of the route in the LCS allow for convenient tracking of the design procedure, including, among others, defining individual geometric elements. After completing this procedure, the obtained solution is transferred to the PL-2000 system using transformation formulas [34]:

4. Reverse Arcs Radii

The values of the radii of the reverse arcs must correspond to the existing system of main directions. The key issue here is to choose the correct point of connection of both arcs. This point (marked C in Figure 3) is located on Line 2, and the condition holds. For the assumed xC, we determine yC using the formula

Then we calculate the distances and .

Of course, the condition must be met

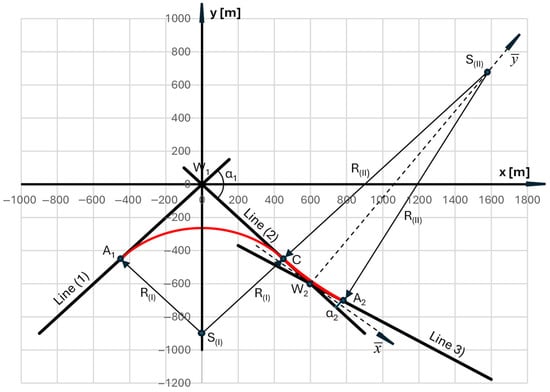

Figure 3.

The primary geometric arrangement of reverse arcs in the local coordinate system.

We treat and as tangents of the corresponding reverse circular arcs. First, we determine the radius R(I) of Arc I. Since its angle of return is , for φ1 = π/4 rad, φ2 = −π/4 rad, we obtain α1 = π/2 rad. From the formula for the value of the tangent

It follows that

The return angle of Arc II, with radius R(II), is . Since in the case under consideration φ2 = −π/4 rad, φ3 = −π/6 rad, we obtain α2 = π/12 rad. The formula for the value of the tangent is

hence

Table 1 presents the values of the radii of the reverse arcs determined for different coordinates of point C in the considered calculation example.

Table 1.

Example values of radii R(I) and R(II) for different coordinates of point C.

As can be seen, for a given arrangement of the main directions of the route and the assumed location of the circular arc connection, there is a specific relationship between the values of these arc radii. Therefore, reverse arcs cannot be shaped arbitrarily; various conditions must be taken into account. Based on the data from Table 1, the case xC = 450 m, yC = −450 m was qualified for further analysis. The driving force behind this decision was the desire to achieve a relatively favorable arc radius R(I) (i.e., one that allows for the highest possible speed), without excessively restricting the area occupied by Arc II. Of course, this decision is purely arbitrary, but Table 1 clearly shows that as R(I) increases, the value of t2 decreases. As a result, it was necessary to consider the initial values of the circular arc radii R(I) = 636.396 m and R(II) = 1611.303 m.

Entering the designated arcs into the system of main directions allows us to create the original geometric system of reverse arcs. This requires first determining the coordinates of the starting point A1 for the arc with radius R(I) and the ending point A2 for the arc with radius R(II) (Figure 3). The coordinates of the point where both arcs join (i.e., point C) are already known.

The following formulas apply:

In the case shown in Figure 3, the determined coordinates are as follows: xA1 = −450 m, yA1 = −450 m, xA2 = 783.712 m and yA2 = −706.066 m.

In the next step, the coordinates of the centers of both circular arcs are determined. For Arc I, lines perpendicular to the corresponding main directions are drawn from points A1 and C. The center of the arc S(I) lies at the intersection of these lines. After solving the appropriate system of equations, the formulas for its coordinates are obtained:

The equation of Arc I is as follows:

In the case under consideration, xS(I) = 0, yS(I) = −900 m, and the arc equation has the form

The procedure for Arc II is analogous. Lines perpendicular to the corresponding main directions are drawn from points C and A2. After solving the appropriate system of equations, the formulas for the coordinates of the center of the arc S(II) are obtained:

The equation of Arc II has the following form:

In the case under consideration xS(II) = 1589.363 m, yS(II) = 689.363 m, and the arc equation is as follows:

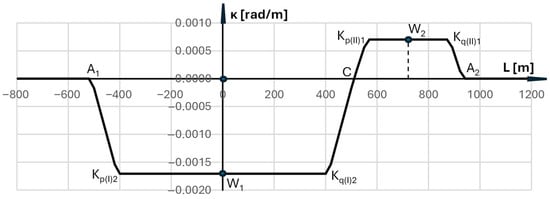

5. Curvature of the Primary Reverse Arc System

The arrangement of primary reverse curves shown in Figure 3 raises serious concerns. These arise from the occurrence of very unfavorable lateral accelerations when the rail vehicle is traveling at a given speed V. This is best seen in the curvature diagram of the geometric system, from which these accelerations directly result.

To determine the curvature graph along the length of the geometric system, a rail vehicle model was used in the form of its rigid base with a length of lb = 20 m. The curvature value is obtained by tracking the position of the moving center of the rigid base. Of course, this is a very simplified model. In analyzing the mechanical system of a rail vehicle and track, it would be necessary to consider the vehicle’s dynamic characteristics (such as the suspension system and the geometry of the wheel–rail contact). However, in the situation under consideration, this was not necessary. The kinematic parameters used in the design of track geometry assume linear changes over time (and therefore also over length). This applies to both the acceleration rate and the lifting speed of the rolling stock wheel on the gradient due to cant. Figure 4 shows the curvature graph obtained for the system of reverse arcs from Figure 3.

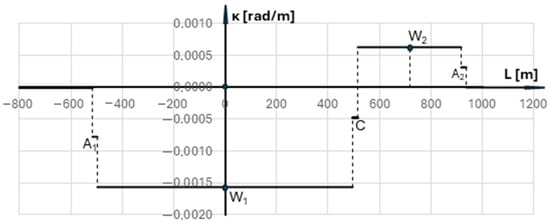

Figure 4.

Curvature diagram over the length of the primary reverse arc system.

As can be seen in the graph, there are sudden, abrupt changes in curvature around points A1, C, and A2. This causes two impacts at each point, transverse to the track, which can be easily observed, for example, on tram lines. However, travel on these lines in areas of abrupt changes in curvature is usually very slow. On railway lines, much higher speeds apply, meaning travel times are shorter, and therefore, the impact-mitigating effect of the rigid base is limited. Therefore, from a theoretical perspective, travel on the discussed geometric configuration could be achieved at low speeds.

Because in the real track, due to its stiffness, the curvature at the joints of individual geometric elements is smoothed out, certain simplifying assumptions can be made to estimate the possible train speed. This involves the assumption (which is highly debatable, by the way) that the change in curvature at critical points occurs not abruptly, but linearly along the length of the rigid base.

The velocity on the geometric system of reverse curves results from the situation occurring at point C, i.e., at the point of contact of Arc I and Arc II. These are curves without cant (i.e., h1 = 0 and h2 = 0). The values of unbalanced acceleration, directed in opposite directions, are as follows:

where the velocity V is expressed in km/h, the radii R(I) and R(II) in meters, and the accelerations am1 and am2 in m/s2.

According to Polish regulations [35], acceleration values should be less than aper = 0.85 m/s2, but this condition is insufficient. The acceleration increase condition should also be checked:

for the assumed length of the rigid wagon base, where ψ is expressed in m/s3. The acceleration increase should be smaller than ψper = 0.5 m/s3 [36]. The relevant analysis is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Determining the approximate train speed for the original reverse curves system.

In the case under consideration, this gives a speed of Vmax = 60 km/h for which ψ = 0.507399 m/s3, i.e. it is lower than the permissible value. This speed is relatively low and, moreover, not entirely reliable. Therefore, modeling of reverse curves should be continued by introducing transition curves for both existing circular arcs. This is possible if there is an appropriate distance between vertices W1 and W2 (it cannot be too small).

The transition curves are entered separately for Arc I and Arc II. As a result of this operation, the radii of these arcs are reduced. The corresponding calculation procedure for Arc I is performed in the local coordinate system, while for Arc II in the auxiliary coordinate system, with subsequent transfer of the obtained solution to the LCS.

The decision was made to use transition curves in the form of a clothoid, written as parametric equations x(l) and y(l). It was recognized that the analytical design method should not utilize simplified solutions, which undoubtedly include the third-degree parabola (also known as the cubic parabola). When determining the equation of this curve, it is assumed that the modeled curvature κ(l) refers to its projection onto the x-axis (i.e., that l = x), and creates an incorrect formula ; after double integration, the equation of the curve is obtained in the form of an explicit function y(x). The third-degree parabola is still commonly used on railways, but with current computational capabilities, it no longer has any practical justification.

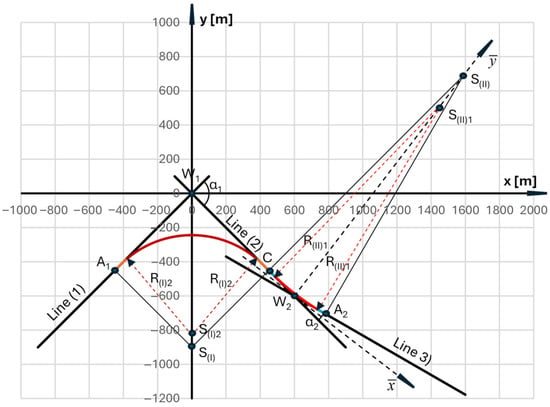

6. Applying Transition Curves for the First Circular Arc

For Arc I, with the primary (initial) radius R(I), transition curves of different lengths L(I)i, i = 1, 2, … can be used. Figure 5 shows a fragment of the local coordinate system containing the effects of using symmetric transition curves of length 50 m and 100 m. It should be noted here that no detailed analysis was planned regarding the selection of transition curve lengths. In the case of reverse curves, train speeds were determined not by the lengths of transition curves (which could be easily corrected), but by the value of the smaller radius of the circular arc. The initial geometric system is marked in red; the system with curves of length L(I)1 = 50 m is marked in green; and the system with curves of length L(I)2 = 100 m is marked in purple.

Figure 5.

Effects of using symmetrical transition curves of 50 m and 100 m length for Arc I (in the local coordinate system).

The given task is to introduce transition curves p and q in the form of a clothoid with an assumed, differentiated length L(I)i at both ends of Arc I (i.e., originating from points A1 and C). Since the designed geometric system is symmetrical, it is sufficient to consider one (in this case, the left) half of it (i.e., with transition curve p) in detail. The straight segment on the left side of the system (i.e., Line 1) is the abscissa axis of the Cartesian coordinate system xk, yk, associated with the given transition curve. The origin of this system is at point A1. We are interested in the coordinates of the curve’s endpoint (i.e., point Kp(I)i) in this system; they result from the corresponding parametric equations xk(l) and yk(l) for l = L(I)i. Since—as it turns out—we must take into account the need to correct the radius of the circular arc, the transition curve equations must use different values of the arc radius R(I)i. When using a transition curve in the form of a clothoid, the following parametric equations apply in the xk, yk system:

while the angle of inclination at the end of the curve is determined from the relationship

The transformation of the transition curve to the x, y coordinate system is performed by rotating the reference system by an angle of α1/2 and shifting the curve origin to point A1. The corresponding formulas depend on the direction of rotation. This operation yields the desired values of the transition curve projections onto the horizontal and vertical axes, which are the coordinates of the curve’s endpoint. If the xk, yk system is rotated clockwise (as in Figure 5), the following relations are obtained:

The angle of inclination Θ(L(I)i) at the end of the curve is determined from the formula

Since the introduction of this transition curve is performed while maintaining the position of its starting point (i.e., point A1), it is necessary to correct the position of the circular arc so that it starts at the point with coordinates xKp(I)i and yKp(I)i, the angle of inclination of the tangent is ΘKp(I)i and the condition of symmetry of the entire system is met (i.e., Θ(0) = 0). This is illustrated in the situation shown in Figure 5.

In this situation, the condition Θ(0) = 0 requires a correction of the arc radius value. This is directly related to the assumed transition curve length. The final solution to the problem is achieved for a specific value of L(I)i, which is considered the most favorable.

Determining the corrected radius R(I)i requires determining the coordinates of the center S(I)i of the corresponding circular arc. It lies on the line perpendicular to the tangent at the end of the transition curve, with the equation

at a distance R(I)i from the point Kp(I)i; it follows from this

By solving the appropriate system of equations, we obtain the desired coordinates

The necessity of fulfilling the condition xS(I)i = 0 means that

determining the coordinates of point S(I)i with a changing value of this radius.

Direct determination of the corrected arc radius R(I)i using Equation (35) is obviously impossible, because both xKp(I)i and ΘKp(I)i depend on the value of R(I)i. What remains is the iterative way, i.e., substituting changing values of R(I)i until the key condition xS(I)i = 0 is met. There was no need to specify the number of iterations, computation time or convergence speed; the end of the calculations was determined by the practical accuracy of determining the radius value, which was 1 mm. The final part of the calculations for the selected case (with α1 = π/2 rad, xA1 = −450 m, yA1 = −450 m and L(I)1 = 50 m) is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Determining the corrected radius of the first arc for L(I)1 = 50 m.

Taking into account the appropriate number of decimal places for the determined abscissa, xS(I)1 indicated the corrected circular arc radius R(I)1 = 611.227 m (marked in bold in Table 3). Thus, the circular arc of radius R(I), which is part of the reverse arc, is replaced by a circular arc of radius R(I)1 and two transition curves of length L(I)1 = 50 m (Figure 5).

The general equation of a circular arc with radius R(I)i has the form

Taking into account the existing symmetry, the entire arrangement of the first arc is described as follows:

- for , that is

- for , where xKq(I)i = −xKp(I)i

- for , that is

In the situation shown in Figure 5, L(I)1 = 50 m was first assumed. Since α1 = π/2 rad, xA1 = −450 m and yA1 = −450 m, the coordinates of the end of the first transition curve in the xk, yk system are as follows: xk(L(I)1) = 49.992 m, yk(L(I)1) = −0.665 m. The angle of inclination of the tangent is Θ(L(I)1) = −0.03928 rad. The coordinates of the center of the corrected arc are: xS(I)1 = 0, yS(I)1 = −864.647 m. This corresponds to the following values in the local coordinate system: xKp(I)1 = −414.187 m, yKp(I)1 = −415.113 m, ΘKp(I)1 = 0.746114 rad, x(0) = 0, y(0) = −253.420 m, xKq(I)1 = 414.187 m, yKq(I)1 = −415.113 m, ΘKq(I)1 = −0.746114 rad, xC = 450 m and yC = −450 m. The entire geometric system is shown in Figure 5 (the circular arc is marked in green).

The next step was to assume the length L(I)2 = 100 m (while maintaining α1 = π/2 rad, xA1 = −450 m, and yA1 = −450 m). As before, the radius R(I)2 should be determined numerically by specifying the coordinates of point S(I)2 with varying values of this radius. The basic criterion for solving the problem is to meet the key condition xS(I)2 = 0. The final part of the calculations for the discussed case is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Determining the corrected radius of the first curve for L(I)2 = 100 m.

Taking into account the appropriate number of decimal places for the determined abscissa xS(I)2 indicates a corrected circular arc radius R(I)2 = 585.697 m. Thus, the circular arc of radius R(I), which is part of the reverse arc, is replaced by a circular arc of the given radius and two transition curves of 100 m length. This is shown in Figure 5, where the circular arc is marked in purple.

The coordinates of the end of the first transition curve in the xk, yk system are as follows: xk(L(I)2) = 99.927 m, yk(L(I)2) = −2.844 m. The angle of inclination of the tangent is Θ(L(I)2) = −0.085368 rad. The coordinates of the center of the corrected arc are: xS(I)2 = 0, yS(I)2 = −829.306 m. This corresponds to the following values in the local coordinate system: xKp(I)2 = −377.330 m, yKp(I)2 = −381.352 m, ΘKp(I)2 = 0.70003 rad, x(0) = 0, y(0) = −243.609 m, xKq(I)2 = 377.330 m, yKq(I)2 = −381.352 m, ΘKq(I)2 = −0.70003 rad, xC = 450 m and yC = −450 m.

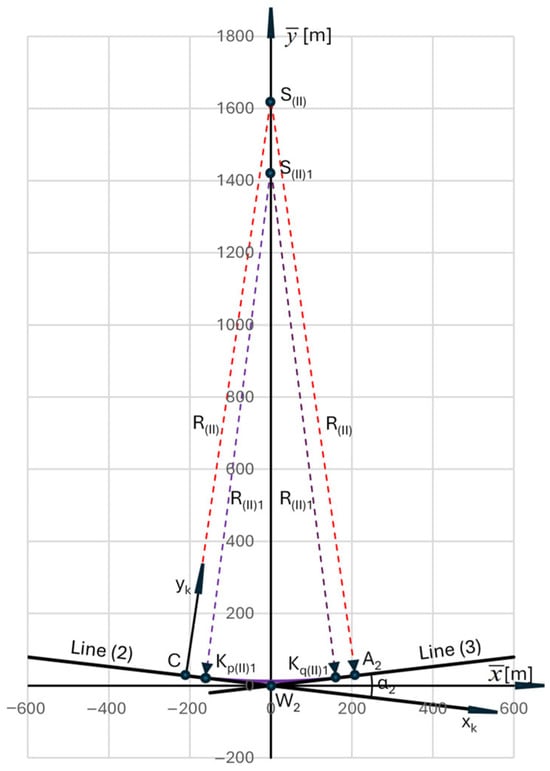

7. Applying Transition Curves for the Second Circular Arc

The transition curves at Arc II (with radius R(II)) are inserted in the auxiliary coordinate system (Figure 3). This system has its origin at point W2, and the ordinate axis on the line passing through points W2 and S(II). The equation of the axes in the LCS is as follows:

The axis passes through point W2 perpendicularly to the axis; therefore, it is described by the equation

The separated auxiliary coordinate system is shown in Figure 6. It contains the effects of applying symmetrical transition curves in the form of a clothoid for an arc with an initial radius R(II). The primary geometric system (without transition curves) is marked in red, which, however—in the adopted drawing scale—has been obscured by the system with curves of length L(II)1 = 50 m, marked in purple.

Figure 6.

A circular arc with a larger radius (located between points C and A2), corrected by introducing transition curves (marked in purple).

In the system, the inclinations of the main directions intersecting at point W2(0,0) result from the angle of inclination α2. The angle of inclination of Line 2 is −α2/2, and of Line 3: α2/2. The abscissa of point S(II) is equal to zero, and the ordinate results from the relationship:

Point C has coordinates:

and point A2:

The equation of Line 2 has the form

and the equation of Line 3

The radius of the arc starting from point C lies on the line with equation

and the radius originating from point A2 is located on the straight line

The equation of Arc II is as follows:

In the example considered, α2 = π/12 rad. We therefore obtain

We introduce transition curves p and q in the form of a clothoid of length L(II)i, i = 1, 2, … at both ends of Arc II (i.e., starting from points C and A2). For symmetry reasons, we consider only the left half of the geometric system (with curve p). The segment of Line 2 is the abscissa axis of the Cartesian coordinate system xk, yk, associated with the given transition curve. The origin of this system is at point C. We are interested in the coordinates of the endpoint of the curve in this system (i.e., point Kp(II)i). As in Section 6, in the equations of the transition curve, we must operate with different values of R(II)i of the arc radius. When using a transition curve in the form of a clothoid, Equation (27) applies to xk(L(II)i), and Equation (49) applies to yk(L(II)i)

while the angle of inclination Θk(L(II)i) at the end of the curve is determined from the dependence

The transformation of the transition curve into the coordinate system is performed by rotating the reference system by an angle α2/2 and shifting the curve origin to point C. The corresponding formulas depend on the direction of rotation. This operation results in the desired values of the projections of the transition curve onto the horizontal and vertical axes, which are the coordinates of the end Kp(II)i of the curve. If the xk, yk system is rotated to the left (as in Figure 6), the following values are obtained:

The angle of inclination Θ(L(II)i) at the end of the curve is determined from the relationship

Since the introduction of this transition curve is performed while maintaining the position of its starting point (i.e., point C), it is necessary to correct the position of the circular arc so that it starts at the point with coordinates and , the angle of inclination of the tangent is there and the condition of symmetry of the entire system is met (i.e., ). This last condition requires the value of the arc radius to be corrected. This is directly related to the assumed length of the transition curve. Determining the corrected radius R(II)i requires determining the coordinates of the center S(II)i of the corresponding circular arc. It lies on the line perpendicular to the tangent at the end of the transition curve, with the equation

The center of the corrected circular arc lies on this line, at a distance R(II) from the point Kp(II)i. This gives the system of equations:

By solving this system of equations, we obtain the desired coordinates

The correct solution requires that the condition . This means that

In the above relation, the abscissa is described by Equation (51), in which xk(L(II)i) and yk(L(II)i) depend on the radius R(II)i; this also applies to the angle .

In this situation, as in Section 6, the radius R(II)i should be determined iteratively, changing the values of this radius when determining the coordinates of point S(II)i. The solution to the problem is determined by fulfilling the condition . The final fragment of the calculations for the selected case (with α2 = π/12 rad, xC = −210.317 m, yC = 27.689 m and L(II)i = L(II)1 = 50 m) is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Determining the corrected radius of the second arc.

Taking into account the appropriate number of decimal places for the determined abscissa, xS(II)i indicated the corrected circular arc radius R(II)i = R(II)1 = 1421.338 m. Thus, the circular arc of radius R(II), which is part of the reverse arc, is replaced by a circular arc of radius R(II)1 and two transition curves of length L(II)1 (Figure 6).

The equation of a circular arc with radius R(II)i in the system has the form

The entire system is described as follows:

- for , that is

- for , where

- for , that is

In the situation shown in Figure 6, L(II)i = L(II)1 = 50 m was assumed. The coordinates of the end of the first transition curve in the xk, yk system are as follows: xk(L(II)1) = 49.998 m, yk(L(II)1) = 0.293 m, and the angle of inclination of the tangent is Θk(L(II)1) = 0.017589 rad. For α2 = π/12 rad, = −210.317 m and = 27.689 m, this corresponds to the following values in the coordinate system: = −160.708 m, = 21.453 m, = −0.11331 rad, = 0, = 12.339 m, = 160.708 m, = 21.453 m, = 0.11331 rad, = 210.317 m and = 27.689 m.

At the end of the discussed procedure, we transfer the obtained solution from the auxiliary coordinate system to the x, y system. To do this, we move the origin of the system to point W2 in the LCS and rotate it counterclockwise by an angle . Since in the considered case φ3 = −π/6 rad, and α2 = π/12 rad, hence, the angle γ = 5π/24 rad. The following transformation formulas apply [34]:

where .

8. The Resulting Geometric Arrangement of Reverse Curves

The final solution to the problem was a geometric system consisting of a circular arc of radius R(I)2 = 585.697 m with two hundred-meter transition curves in the form of a clothoid (determined in Section 6) and an inversely directed arc of radius R(II)1 = 1421.338 m with two fifty-meter curves in the form of a clothoid (determined in Section 7). The entire system is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The determined geometric system of reverse arcs with transition curves in the local coordinate system.

After transferring the obtained solution to the PL-2000 system, using Equations (8) and (9), the situation shown in Figure 8 arises.

Figure 8.

Designated geometric system of reverse arcs with transition curves in the PL-2000 coordinate system.

9. Evaluation of the Obtained Solution

To evaluate the geometric system shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8, it is necessary to first determine its horizontal curvature along its length and then analyze the achievable train speed. The curvature diagram was based on the model of a moving rigid base of a rail vehicle, as used in Section 5. Figure 9 shows the curvature diagram for the resulting reverse curve system.

The curvature diagram in Figure 9 indicates that both horizontal curves can be considered independently, and the train speed on the entire system will be determined by the curve with the greater curvature (i.e., the arc with radius R(I)2. The first step is to check the possible speed without the use of cant. This is shown in Table 6, separately for both curves under consideration. The formulas for accelerations am1 and am2 from Section 5 (taking into account the corrected radii) and the formulas for the acceleration increase

Table 6.

Determination of train speeds in the absence of cant for both corrected curves.

Table 6 shows the values of key kinematic parameters and the resulting speed derived from them. For both circular arcs, the differential impact of acceleration and acceleration increase on the achieved speed is evident. On the arc with a smaller radius (i.e., Arc I), the acceleration parameter plays a decisive role, determining Vmax = 80 km/h. The acceleration gain condition would result in Vmax = 100 km/h, but the lower value is valid. On the curve with a larger radius (i.e., Arc II), the opposite occurs: the acceleration gain plays a decisive role, determining Vmax = 105 km/h (the acceleration condition would result in Vmax = 125 km/h). Of course, on the entire reverse curve system, in the absence of cant, the determined speed is Vmax = 80 km/h.

In the next step, the effects of applying cant to an arc will be examined. Table 7 presents the appropriate procedure for a circular curve with a smaller radius. The following formula for unbalanced acceleration was used:

where h1—cant value in millimeters, g—acceleration of gravity (g = 9.81 m/s2), s—center distance of rails (on standard gauge lines, s = 1500 mm).

Table 7.

Determining the train speed for the corrected first curve, along with the selection of the cant value.

The formula for the increase in acceleration ψ1 is the same as that used in Table 6, but the lifting speed of the rolling stock wheel on the gradient due to cant must be determined using the formula

The f1 value should not be greater than 50 mm/s [35].

As it turns out, this speed is determined by the unbalanced acceleration occurring on the curve. The highest achievable speed on Arc I is 115 km/h, with an applied cant of 140 mm. For this speed, all required kinematic conditions are met.

A similar procedure performed for Arc II is illustrated in Table 8. The designation h2 refers to the cant value on this curve. The following calculation formulas were used:

Table 8.

Determining the train speed for the corrected second curve, along with the selection of the cant value.

In Table 8, unlike Table 7, the speed is determined by the acceleration increase on the transition curve. The highest speed achieved in this analysis on Arc II is 120 km/h, with a cant of 45 mm. Of course, this speed could be significantly increased by further increasing the cant on the curve. However, this would not make much sense, as the speed on the reverse curves will be determined by the speed on the arc with a smaller radius anyway. Therefore, in the case under consideration, trains could run at 115 km/h.

To summarize the analysis of the achievable train speeds presented in this article, the effects of subsequent actions can be identified for the geometric system under consideration. In the absence of transition curves and cant on the arc, the speed is very limited, and the value of V = 60 km/h given in Table 2 is highly questionable. The use of transition curves allows for increasing this value to V = 80 km/h. Finally, the introduction of cant on the circular arc (and therefore also a gradient due to cant) determines the speed of V = 115 km/h. Higher train speeds increase the capacity of the railway line and bring specific economic benefits.

The presented procedure is universal and can be applied to other geometric situations involving the design of reverse curves. For a given layout of the main directions of a railway line, it allows for the selection of the initial radii of both circular curves, which can then be adjusted by introducing transition curves of varying lengths. The basic criterion for evaluating the resulting solution is the train speed, which can be changed by making appropriate corrections to the geometric layout.

10. Conclusions

On railway lines, due to competitive conditions with other transport systems, the most important issues currently seem to be those related to increasing train speeds; this is reflected in the dominance of high-speed rail. Traditional, existing railway lines (mostly built in the 19th century) are often overlooked in research, as they would need to be modified to meet contemporary requirements. This is particularly true for railway lines running through difficult terrain (e.g., mountainous terrain), which feature small horizontal arc radii and controversial geometric configurations such as compound curves and reverse curves. Improving the quality of these lines, leading to increased speeds, requires appropriate modernization activities.

This article addresses the design of reverse curves: a geometric system composed of two circular arcs (usually with different radii) oriented in opposite directions and directly connected. The goal is also to be able to recreate (i.e., model) an existing geometric system with reverse curves, so that subsequent corrections to the horizontal ordinates in the area where the circular arcs connect can be made. An effective design method needs to be developed that can be used not only to determine the coordinates of a new reverse curve but also to model the existing system (with a view to its subsequent modification). In the case of an existing system, measurement data obtained in the PL-2000 system can be transferred to the local coordinate system and processed there in order to determine the basic geometric parameters.

The solution to the problem is obtained analytically. Individual elements of the geometric system are described using mathematical equations, and the design itself is performed in the appropriate local Cartesian coordinate system, based on the symmetrically arranged adjacent main directions of the route. However, in the case of reverse curves, there is a fundamental difference from most analytical design methods. In geometric systems, two adjacent main directions are most often identified and incorporated into further procedures (including the creation of a local coordinate system). In reverse curves, a third main direction appears, significantly complicating the matter, limiting the universality of the developed method. However, with regard to the local coordinate system, the adopted principle was retained: it is determined using two adjacent main directions. The origin of this system is located at its intersection, the coordinates of which are known in the global coordinate system.

The radii of the reverse arcs must correspond to the existing system of main directions. The key issue here is to select the correct connection point for both arcs. Therefore, reverse arcs cannot be arbitrarily shaped; various conditions must be taken into account. Entering the determined arcs into the system of main directions allows for the creation of the initial geometric system of the reverse arcs. Then, transition curves are introduced for both existing circular arcs. This is possible if there is an appropriate distance between the points of intersection of the main directions (which cannot be too small). As a result, the arc radii are reduced. Their values are determined iteratively. The corresponding calculation procedure for the first arc takes place in the local coordinate system, while the procedure for the second arc takes place in the auxiliary coordinate system, with the resulting solution subsequently transferred to the local coordinate system.

This article presents a set of formulas for creating a geometric system of reverse curves. These formulas were used in the calculation example. A graph of the horizontal curvature of the track axis and a method for determining train speed are shown. The train speed on the entire system is determined by the curve with the greatest curvature. In the first stage, the achievable speed without the use of cant on the curve was determined. Next, the effects of applying cant were discussed. The presented procedure is universal and can be applied to other geometric situations involving the design of reverse curves.

When modeling an existing geometric system and using survey data, the coordinates of the W1 main point in the PL-2000 coordinate system are naturally subject to a certain error, which affects the local coordinate system and, consequently, the entire calculation process. However, the determination of the designed geometric system in the field will also be subject to error. Therefore, the error will not be generated solely by the calculation phase of the process. The final accuracy will depend on the precision of the measurement (geodetic) technique used.

The presented method enables full control over the reverse curve design process and allows for strategic decision-making regarding the optimal geometric system parameters. It allows for the use of both freely accepted input data and measurement data from the operating railway track. After the calculation procedure is completed in the local coordinate system, data is generated for the establishment of a new geometric system in the field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Arc I | Marking the first circular arc |

| Arc II | Marking the second circular arc |

| A1 | Designation of the starting point of a geometric system |

| A2 | Designation of the end point of a geometric system |

| am1 | Unbalanced acceleration on Arc I |

| am2 | Unbalanced acceleration on Arc II |

| aper | Permissible value of unbalanced acceleration |

| C | Destination of the assumed connection point of reverse arc |

| Distance between points C and W2 | |

| f1 | Lifting speed of the rolling stock on the gradient due to cant for Arc I |

| f2 | Lifting speed of the rolling stock on the gradient due to cant for Arc II |

| g | Acceleration of gravity (g = 9.81 m/s2) |

| h1 | Track cant on Arc I |

| h2 | Track cant on Arc II |

| Kp(I)i | End of the assumed transition curve before Arc I |

| Kp(I)1 | End of the transition curve before Arc I for its assumed length L(I)1 |

| Kp(I)2 | End of the transition curve before Arc I for its assumed length L(I)2 |

| Kq(I)i | End of the assumed transition curve after Arc I |

| Kq(I)1 | End of the transition curve after Arc I for its assumed length L(I)1 |

| Kq(I)2 | End of the transition curve after Arc I for its assumed length L(I)2 |

| Kp(II)i | End of the assumed transition curve before Arc II |

| Kp(II)1 | End of the transition curve before Arc II for its assumed length L(II)1 |

| Kq(II)i | End of the assumed transition curve after Arc II |

| Kq(II)1 | End of the transition curve after Arc II for its assumed length L(II)1 |

| l | Transition curve parameter (distance from the beginning of the curve) |

| lb | Length of the rigid wagon base |

| LCS | Local coordinate system |

| Line 1 | Marking the first main direction of the route |

| Line 2 | Marking the second main direction of the route |

| Line 3 | Marking the third main direction of the route |

| L(I)i | Assumed lengths of the transition curves for Arc I |

| L(I)1 | The first assumed length of the transition curve for Arc I |

| L(I)2 | The second assumed length of the transition curve for Arc I |

| L(II)i | Assumed lengths of the transition curves for Arc II |

| L(II)1 | The first assumed length of the transition curve for Arc II |

| p | Marking the transition curve before the circular arc |

| PL-2000 | The Polish national spatial reference system |

| q | Marking the transition curve after the circular arc |

| R(I) | Initial value of Arc I radius |

| R(I)i | Corrected Arc I radius |

| R(I)1 | Value of corrected Arc I radius after introducing a transition curve of length L(I)1 |

| R(I)2 | Value of corrected Arc I radius after introducing a transition curve of length L(I)2 |

| R(II) | Initial value of Arc II radius |

| R(II)i | Corrected Arc II radius |

| R(II)1 | Value of corrected Arc II radius after introducing a transition curve of length L(II)1 |

| s | Center distance of rails (on standard gauge lines s = 1500 mm) |

| s1 | Slope tangent Line 1 in the LCS |

| s2 | Slope tangent Line 2 in the LCS |

| s3 | Slope tangent Line 3 in the LCS |

| S(I) | Center of the primary Arc I |

| S(I)i | Corrected Arc I center |

| S(I)1 | Corrected Arc I center after introducing a transition curve of length L(I)1 |

| S(I)2 | Corrected Arc I center after introducing a transition curve of length L(I)2 |

| S(II) | Center of the primary Arc II |

| S(II)i | Corrected Arc II center |

| S(II)1 | Corrected Arc II center after introducing a transition curve of length L(II)1 |

| t1 | Value of the tangent to Arc I |

| t2 | Value of the tangent to Arc II |

| V | Train speed |

| Vmax | Maximum speed of trains on the route |

| W1 | Intersection point of the first and second main directions of the route |

| W2 | Intersection point of the second and third main directions of the route |

| Distance between points W1 and C | |

| Distance between points W1 and W2 | |

| X | North coordinate of the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| XW1 | Ordinate of point W1 in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| XW2 | Ordinate of point W2 in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| x | Abscissa of the local coordinate system |

| Abscissa of the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| xA1 | Abscissa of point A1 in the LCS |

| xA2 | Abscissa of point A2 in the LCS |

| Abscissa of point A2 in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| xC | Abscissa of point C in the LCS |

| Abscissa of point C in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| xk | Abscissa in the transition curve coordinate system |

| xKp(I)i | Abscissa of the end of the transition curve before Arc I in the LCS |

| xKq(I)i | Abscissa of the end of the transition curve after Arc I in the LCS |

| Abscissa of point Kp(II)i in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| Abscissa of point Kp(II)1 in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| Abscissa of point Kq(II)i in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| Abscissa of point Kq(II)1 in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| xS(I) | Abscissa of the center of the primary Arc I in the LCS |

| xS(I)i | Abscissa of corrected Arc I center in the LCS |

| xS(I)1 | Abscissa of corrected Arc I center in the LCS after introducing a transition curve of length L(I)1 |

| xS(I)2 | Abscissa of corrected Arc I center in the LCS after introducing a transition curve of length L(I)2 |

| xS(II) | Abscissa of the center of the primary Arc II in the LCS |

| Abscissa of the primary center of Arc II in the auxiliary , coordinate system | |

| xW2 | Abscissa of point W2 in the LCS |

| Y | Easting coordinate of the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| YW1 | Abscissa of point W1 in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| YW2 | Abscissa of point W2 in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| y | Ordinate of the local coordinate system |

| Ordinate of the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| yA1 | Ordinate of point A1 in the LCS |

| yA2 | Ordinate of point A2 in the LCS |

| Ordinate of point A2 in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| yC | Ordinate of point C in the LCS |

| Ordinate of point C in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| yk | Ordinate in the transition curve coordinate system |

| yKp(I)i | Ordinate of the end of the transition curve before Arc I in the LCS |

| yKq(I)i | Ordinate of the end of the transition curve after Arc I in the LCS |

| Ordinate of point Kp(II)i in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| Ordinate of point Kp(II)1 in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| Ordinate of point Kq(II)i in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| Ordinate of point Kq(II)1 in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| yS(I) | Ordinate of the center of the primary Arc I |

| yS(I)i | Ordinate of corrected Arc I center in the LCS |

| yS(I)1 | Ordinate of corrected Arc I center in the LCS after introducing a transition curve of length L(I)1 |

| yS(I)2 | Ordinate of corrected Arc I center in the LCS after introducing a transition curve of length L(I)2 |

| yS(II) | Ordinate of the center of the primary Arc II |

| Ordinate of the primary center of Arc II in the auxiliary coordinate system | |

| yW2 | Ordinate of point W2 in the LCS |

| α1 | Turning angle of the route at point W1 |

| α2 | Turning angle of the route at point W2 |

| β | Rotation angle of the PL-2000 system when transformed to the LCS |

| γ | Rotation angle of the system when it is transformed to the LCS |

| Θ | Inclination angle at the end of the transition curve in the LCS |

| ΘKp(I)i | Inclination angle at the end of the transition curve before Arc I in the LCS |

| ΘKq(I)i | Inclination angle at the end of the transition curve after Arc I in the LCS |

| Angle of inclination of the tangent at the end of transition curve before Arc II in the coordinate system | |

| Angle of inclination of the tangent at the end of transition curve of length L(II)1 before Arc II in the coordinate system | |

| Angle of inclination of the tangent at the end of transition curve after Arc II in the coordinate system | |

| Angle of inclination of the tangent at the end of transition curve of length L(II)1 after Arc II in the coordinate system | |

| κ | Curvature of the track axis |

| Φ1 | Inclination angle of Line 1 in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| Φ2 | Inclination angle of Line 2 in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| Φ3 | Inclination angle of Line 3 in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| Φx | Angle of inclination of the x-axis in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| Φy | Angle of inclination of the y-axis in the PL-2000 coordinate system |

| Θk | Angle of inclination of the tangent at the end of the transition curve in xk, yk system |

| φ1 | Inclination angle of Line 1 in the LCS |

| φ2 | Inclination angle of Line 2 in the LCS |

| φ3 | Inclination angle of Line 3 in the LCS |

| ψ | Acceleration increase |

| ψ1 | Acceleration increase on the transition curve for Arc I |

| ψ2 | Acceleration increase on the transition curve for Arc II |

| ψper | Permissible value of acceleration increase |

References

- Beria, P.; Grimaldi, R.; Albalate, D.; Bel, G. Delusions of success: Costs and demand of high-speed rail in Italy and Spain. Transp. Policy 2018, 68, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lin, S.; Zhang, J.; He, M. Does high-speed rail promote enterprises productivity? Evidence from China. J. Adv. Transp. 2019, 2019, 1279489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rus, G. The economic rationale for high-speed rail. In International Encyclopedia of Transportation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, F.; Wang, J.; Du, D. High-speed rail heading for innovation: The impact of HSR on intercity technology transfer. Area Dev. Policy 2022, 7, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, L. High-speed railway opening, industrial symbiotic agglomeration and green sustainable development—Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, F.; Bosi, T.; Pineda-Jaramillo, J.; Viti, F. Long-term fleet management for freight trains: Assessing the impact of wagon maintenance through simulation of shunting policies. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2024, 29, 100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, X.; Zeng, J.; Mao, R.; Wei, L.; Wu, S. Innovative method for high-speed railway carbody vibration control caused by hunting instability using underframe suspended equipment. J. Vib. Control. 2024, 31, 3245–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, R.; Mo, J.; Xiang, Z.; Zhou, Z. A cross-domain state monitoring method for high-speed train brake pads based on data generation under small sample conditions. Measurement 2024, 226, 114074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A.; Yin, H.; Sebès, M.; Chollet, H.; Pozzolini, C. A semi-analytical numerical method for modelling the normal wheel-rail contact. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2022, 60, 1322–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.; Jaafar, S.A.; Zhou, W.; Yan, H.; Chen, J.; Meng, X. Wheel-rail contact and friction models: A review of recent advances. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2023, 237, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, G. A transient three-dimensional wheel-rail adhesion model under wet condition considering starvation and surface roughness. Wear 2024, 540–541, 205263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimu, A.; Zhou, W.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y.; Shen, C. Evaluation of the vehicle-cargo and vehicle-trackside clearance of long and big railway freight vehicles. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 119, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, B.; Wu, S.; Wen, Z. Effects of wheel tread hollow wear on wheel-rail adhesion under wet condition. Tribol. Int. 2025, 211, 110927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AutoCAD Civil 3D: Design, Engineering and Construction Software. Available online: http://www.autodesk.pl/products/civil-3d (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Bentley Rail Track: Rail Infrastructure Design and Optimization. Available online: https://www.bentley.com/software/rail-design (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Koc, W. Elements of Track Systems Design Theory; Gdansk University of Technology Publishing House: Gdansk, Poland, 2004. Available online: https://mostwiedzy.pl/pl/publication/elementy-teorii-projektowania-ukladow-torowych.92886-1 (accessed on 6 January 2026). (In Polish).

- Hodas, S. Design of railway track for speed and high-speed railways. Procedia Eng. 2014, 91, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghastya, A.; Prihatanto, R.; Rachman, N.F.; Adi, W.T.; Astuti, S.W.; Wirawan, W.A. A new geometric planning approach for railroads based on satellite imagery. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2671, 50005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, M. Fundamentals of Railway Design, Chapter: The Alignment Design of Ordinary and High-Speed Railways; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 21–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tasci, L.; Kuloglu, N. Investigation of a new transition curve. Balt. J. Road Bridge Eng. 2011, 6, 23−29. [Google Scholar]

- Kobryn, A. Universal solutions of transition curves. J. Surv. Eng. 2016, 142, 4016010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, W. New transition curve adapted to railway operational requirements. J. Surv. Eng. 2019, 145, 4019009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zboinski, K.; Woznica, P. Optimum railway transition curves for different circular arc radii. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2022, 68, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsson, B.A. Design of optimization of switch rails in railway turnouts. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2013, 51, 1610–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, W. Design of High-Speed Railway Turnouts; Theory and Applications; Elsevier Science & Technology: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koc, W. Analytical method of connecting parallel tracks located in a circular arc using curved turnouts. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2020, 146, 4019081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamarat, M.; Papaelias, M.; Kaewunruen, S. Fatigue damage assessment of complex railway turnout crossings via Peridynamics-based digital twin. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonias, E.C.; Tonias, C.N. Compound and reversed curves. In Geometric Procedures for Civil Engineers; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Germany, 2016; pp. 185–242. [Google Scholar]

- Koc, W. Design of reverse curves adapted to the satellite measurements. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2016, 2016, 6503962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, W. Analytical method of modelling the geometric system of communication route. Math. Probl. Eng. 2014, 2014, 679817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 15 October 2012 on the National Spatial Reference System. J. Laws Repub. Pol. 2012. Available online: https://api.sejm.gov.pl/eli/acts/DU/2024/342/text.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026). (In Polish)

- Koc, W. Determination of track axis coordinates in the analytical method of designing railway route geometry. Eur. J. Appl. Sci. 2024, 12, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, W. Modeling of compound curves on railway lines. Geomatics 2025, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, G.A.; Korn, T.M. Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers, 1st ed.; McGraw–Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Technical Standards—Detailed technical conditions for the modernization or construction of railway lines up to a speed of Vmax ≤ 250 km/h. In Volume I—Railroad—Appendix ST-T1-A6—Geometric Layouts of Tracks; PKP Polish Railway Lines S.A.: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; Available online: https://www.plk-sa.pl/klienci-i-kontrahenci/akty-prawne-i-przepisy/standardy-techniczne (accessed on 6 January 2026). (In Polish)

- Regulation of the Minister of Transport and Maritime Economy of 10 September 1998 on the Technical Conditions to Be Met by Railway Structures and Their Location. J. Laws Repub. Pol. 1998. Available online: https://serwisppoz.tarbonus.pl/wp-content/uploads/R980987p.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026). (In Polish).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.