Abstract

Reverse engineering (RE) is essential in the automotive and aerospace industries for reconstructing high-precision components, such as exhaust valves, when design documentation is unavailable. However, different measurement methods introduce varied errors that can affect engine performance and safety. This study presents a comparative analysis of contact and optical measurement systems—specifically the CMM Accura II (ZEISS Group, Oberkochen, Germany), Mahr MarSurf XC 20 (Esslingen am Neckar, Germany), GOM Scan 1 (ZEISS/GOM, Braunschweig/Oberkochen, Germany) and MCA-II with an MMD×100 laser head (Nikon Metrology, Leuven, Belgium)—to assess their accuracy in reconstructing exhaust valve geometry. The research procedure involved measuring global surface deviations and critical functional parameters, including stem diameter, straightness, and seat angle. The results indicate that tactile methods (CMM and Mahr) provide significantly higher accuracy and lower dispersion than optical methods. The Mahr system was the most effective for stem precision, while the CMM was the only system to pass the seat angle tolerance requirement unambiguously. In contrast, the MCA-II laser system failed to meet the required precision–mechanical tolerances. The findings suggest that an optimal industrial strategy should adopt a hybrid methodology: utilizing rapid optical scanning (GOM) for general geometry and high-precision tactile systems (CMM, Mahr) for critical functional features. This approach can reduce total inspection time by 30–40% while ensuring technical safety and preventing catastrophic engine failures.

1. Introduction

Reverse engineering (RE) is a fundamental process in modern industry, involving the reconstruction of a digital 3D model of a physical object whose original design documentation is unavailable or requires verification [1,2]. In the rebuilding of model geometry, two paths can be distinguished: medical and technical. The medical path is based on data acquired using medical diagnostic systems (including multidetector computed tomography, cone-beam computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging). The data collected along this path primarily consist of 2D images. These images are converted into a three-dimensional model of the anatomical structure using specialized software. The goal of this path is to develop custom-fitted surgical templates and implants tailored to a specific patient [3,4]. In the technical path, the reverse engineering process involves reconstructing the existing geometry, mainly representing a machine part, from data obtained using contact [5,6] or optical measurement methods [5,6,7]. This process can be divided into four phases: Data Acquisition [5,6], Triangulation [8], Computer-Aided Design (CAD) modeling [9,10], and Model Manufacture (e.g., using subtractive [11] or additive methods [12,13]). RE in the technical path is most commonly used in the automotive [14] and aerospace [15] industries for the following purposes:

- Creating geometrically complex elements that are difficult to model in CAD software;

- Overcoming obstacles in data exchange and integrity;

- Reconstructing complex geometries that may not have an existing CAD model;

- Solving and correcting problems resulting from discrepancies between the CAD model and the actual tooling or as-built part;

- Accelerating innovation in areas such as ergonomic, retro-inspired design, and aerodynamic design;

- Ensuring quality and efficiency through computer-aided inspection and analysis.

Beyond these applications, RE is vital for reconstructing legacy and obsolete components that lack original documentation, particularly in long-life industrial systems where support has ended. Numerous studies confirm that RE enables functional geometry recovery, supporting remanufacturing and extending the lifespan of mechanical systems. Publication [16] demonstrated RE’s effectiveness in recovering worn or broken parts without original design data, while [17] identified RE as an indispensable tool for servicing obsolete machinery and adapting it to modern manufacturing. In the automotive sector, [14] emphasized its role in reproducing discontinued components and supporting short-series production. Furthermore, [18] highlighted RE as a strategic approach for knowledge recovery and the modernization of technically obsolete but operational products, particularly in the aerospace industry.

The accuracy of geometric model reconstruction in the technical path largely depends on the quality of the collected measurement data and on the methods used for triangle-mesh processing and CAD modeling [18,19]. A lack of appropriate skills in this area can significantly degrade the reconstructed model’s quality relative to the replicated counterpart, potentially increasing shape deviations in the geometry representation. Consequently, the reconstructed object may fail to meet design specifications for sealing, accuracy, fit, and the interelement connections (tolerancing). The acquisition of new data along the technical path is performed using various types of measuring instruments, ranging from contact systems such as a Coordinate Measuring Machine (CMM) [19] or a measuring arm [20] to 2D [21] and 3D optical scanners [10]. It is also possible to digitize the geometry of machine components using a tomography system [5]. It is important to note that in mass production, functional verification is often performed using hard gauges (go/no-go) or pneumatic measuring systems (air gauges). While these methods are highly efficient for pass/fail quality control, they do not provide the digital coordinate data necessary for the Reverse Engineering process. Consequently, this study focuses exclusively on coordinate measuring systems capable of generating the digital point clouds required for surface reconstruction and CAD modeling.

The human factor, particularly operator training and experience, is a significant yet often underestimated source of error in reverse engineering. Studies [19,22] demonstrate that operator-dependent decisions in scanning strategies, alignment, and filtering strongly affect geometric accuracy and measurement repeatability, especially in optical systems. Publication [23] further emphasized that inexperienced operators often employ inappropriate surface segmentation and fitting strategies, resulting in systematic deviations in CAD models. Additionally, publication [20] confirmed that articulated arm systems are particularly susceptible to operator-induced errors due to manual handling and structural rigidity.

Beyond the human factor, errors also arise from the equipment’s technical specifications. Depending on the measurement system used, the magnitude of these errors is influenced by factors such as resolution, repeatability, the measurement area range, and the system’s resistance to environmental conditions [22]. After obtaining measurement data as a three-dimensional point cloud, further transformations are necessary, which can introduce additional sources of error. These result from the need to remove measurement noise [24], fill scan gaps caused by insufficient data points, and align and merge point clouds to achieve a complete geometric representation [8]. Furthermore, during the transformation of the point cloud to a Stereolithography (STL) file, standard software errors can occur, including intersecting triangles, inverted normal vectors, or holes in the mesh. It is important to emphasize that this discretization into a triangular mesh entails an approximation that inherently introduces error [8,24].

Subsequently, during the transformation of the 3D-STL model into a 3D-CAD model, errors associated with parametric generation also arise. At this stage, surface-fitting errors may occur when matching parametric surfaces to the triangle mesh, depending on the method used [10,25]. Additionally, maintaining curve continuity (G2, G3)—crucial for the quality of freeform surfaces—presents significant difficulties [25]. Therefore, developing a methodology that minimizes errors at every stage of geometry digitization, data processing, and CAD modeling is essential in reverse engineering.

To address these challenges, numerous methodological approaches have been developed to reduce errors occurring during the transformation of measurement data into parametric CAD geometry. These methods include advanced point cloud filtering and noise reduction techniques, such as statistical, bilateral, and curvature-based filters, that aim to improve data quality before surface reconstruction [23]. Further approaches focus on mesh repair and optimization, including hole filling, correction of inverted normal vectors, and triangle quality control to ensure the geometric consistency of STL models [8]. Feature-based and template-based reconstruction strategies have also been proposed, particularly for mechanical components with well-defined functional geometry, enabling more reliable generation of parametric CAD features [26]. In addition, adaptive surface-fitting and segmentation methods have been developed to mitigate overfitting and preserve surface continuity (G2/G3) during NURBS-based reconstruction [9,24]. For axisymmetric and hybrid geometries, combined strategies that integrate freeform surfaces with analytically defined primitives have proven particularly effective in reducing systematic modeling errors [27,28]. Finally, iterative CAD-to-measurement validation loops are widely used to identify and compensate for residual deviations by repeatedly comparing the parametric model with the original measurement data [24].

Problems in the reconstruction process also stem from the type of scanned geometry [25,28]. Depending on whether regular shapes or free-form geometries characterize the object, or if it is axisymmetric, various kinds of errors may arise at each stage of reconstruction [27]. Therefore, it is essential to develop a procedure tailored to specific geometry types that minimizes errors during digitalization, data processing, and CAD modeling. For axisymmetric objects, the literature notes that, despite their relatively simple geometry, difficulties may arise in measurement data registration [29], scan alignment, loss of axiality, shape deviations [30,31], and parametric modeling [29]. One notable example of an axisymmetric component in the reconstruction process is the exhaust valve, as one of the most critical and thermally stressed components of an internal combustion engine, the piston’s precise geometry is of paramount importance for combustion efficiency, proper cylinder scavenging, chamber tightness, and overall engine durability [31]. Even minimal deviations in key parameters—such as the angles and filet radii of the valve head or the degree of valve seat wear—can lead to power loss, increased fuel consumption, and reduced engine lifespan [32]. Consequently, the exhaust valve was selected as a representative case study because it is a fundamental industrial component in which local geometric inaccuracies may lead to functional failure, unlike the simplified benchmark geometries commonly used in the literature. It combines global axisymmetry with locally critical functional features—including the valve seat angle, filet radii, and stem straightness—which are highly sensitive to reconstruction errors. Therefore, in the context of reverse engineering, the required accuracy for reconstructing this geometry must be extremely high. Despite these stringent requirements, there are few comprehensive studies on the safety-critical workflow for reconstructing high-precision engine components such as exhaust valves. This study addresses this gap by evaluating not only dimensional accuracy but also the functional risk associated with relying solely on optical digitization for components such as exhaust valves. The novelty lies in defining a validated hybrid workflow that ensures technical safety while leveraging the speed of Industry 4.0 digitization.

2. Materials and Methods

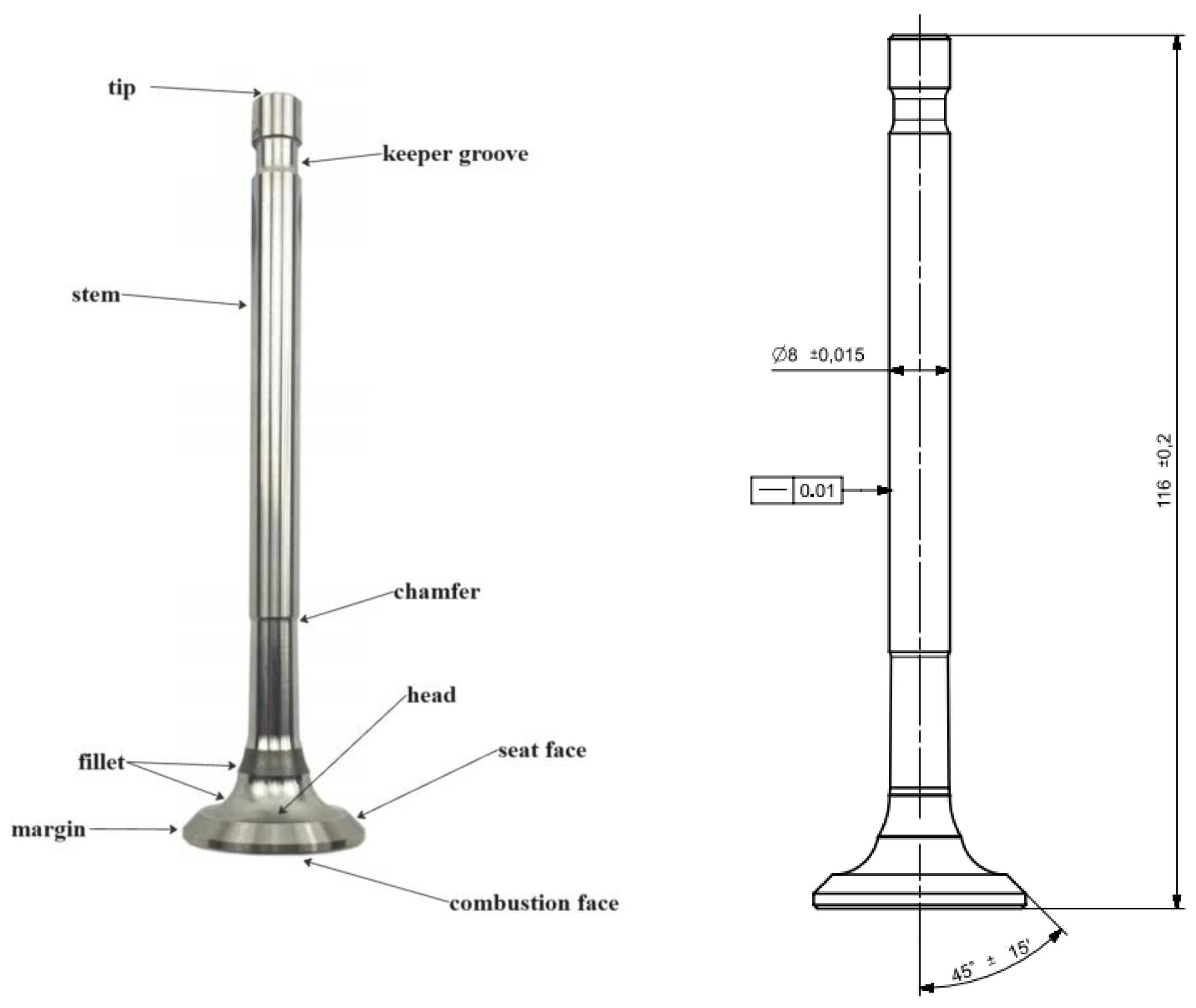

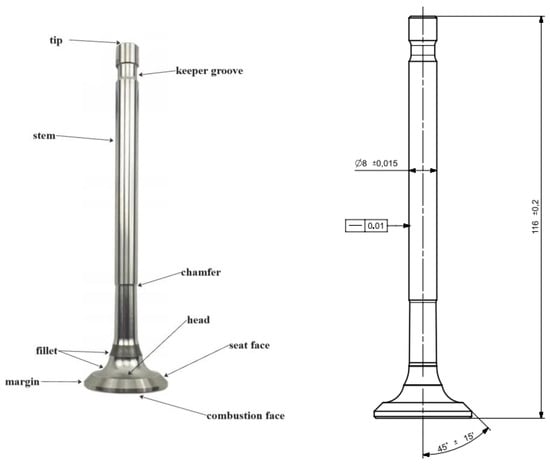

In this study assessing reconstruction accuracy for axisymmetric objects, an exhaust valve was selected (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Physical model showing characteristics examined in article.

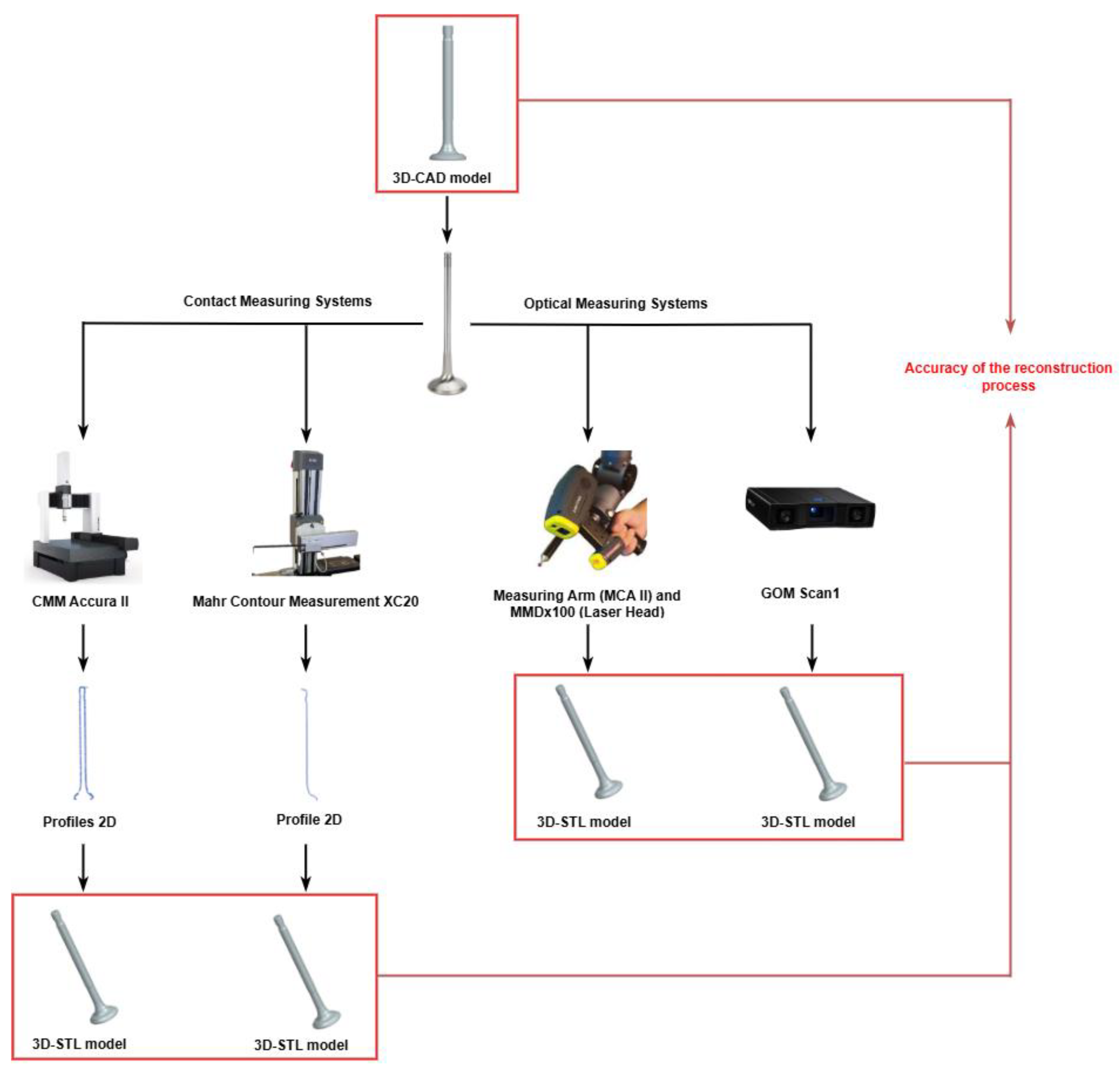

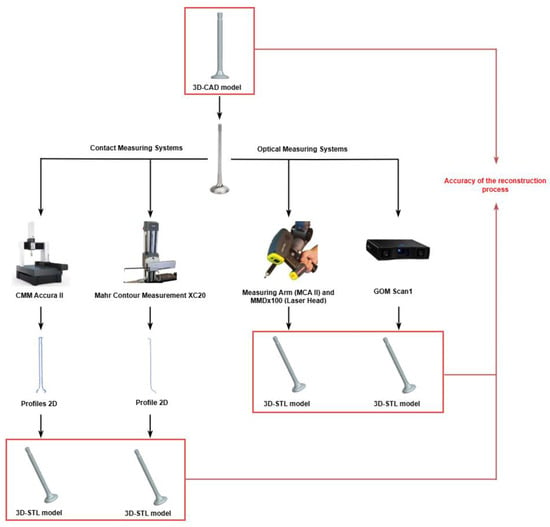

During data collection, contact (Coordinate Measuring Machine (CMM) and contour graph) and optical (laser scanner and structured light scanner) measurement systems were employed. For all measurement systems, the maximum resolution is the resolution with which they can record measurement data. To assess the accuracy of the reconstruction process, the measured data were compared with the developed 3D-CAD model of the exhaust valve (Figure 2). For the exhaust valve model, we distinguish two critical areas: the stem and the head and seat face. The stem is responsible for guiding the valve in its seat and transmitting forces. The head and seat face are responsible for sealing the combustion chamber and effectively transferring heat to the cylinder head. The exhaust valve investigated was a new, unused component manufactured in accordance with standard industrial specifications and exhibited no operational wear or surface degradation. The use of a new part ensured that the measured geometric deviations resulted exclusively from the measurement and reconstruction processes rather than from wear-related surface alterations, thereby improving repeatability and enabling a reliable comparison between contact and optical measurement systems.

Figure 2.

Diagram of Research Procedure.

Exhaust Valve Geometry Measurement

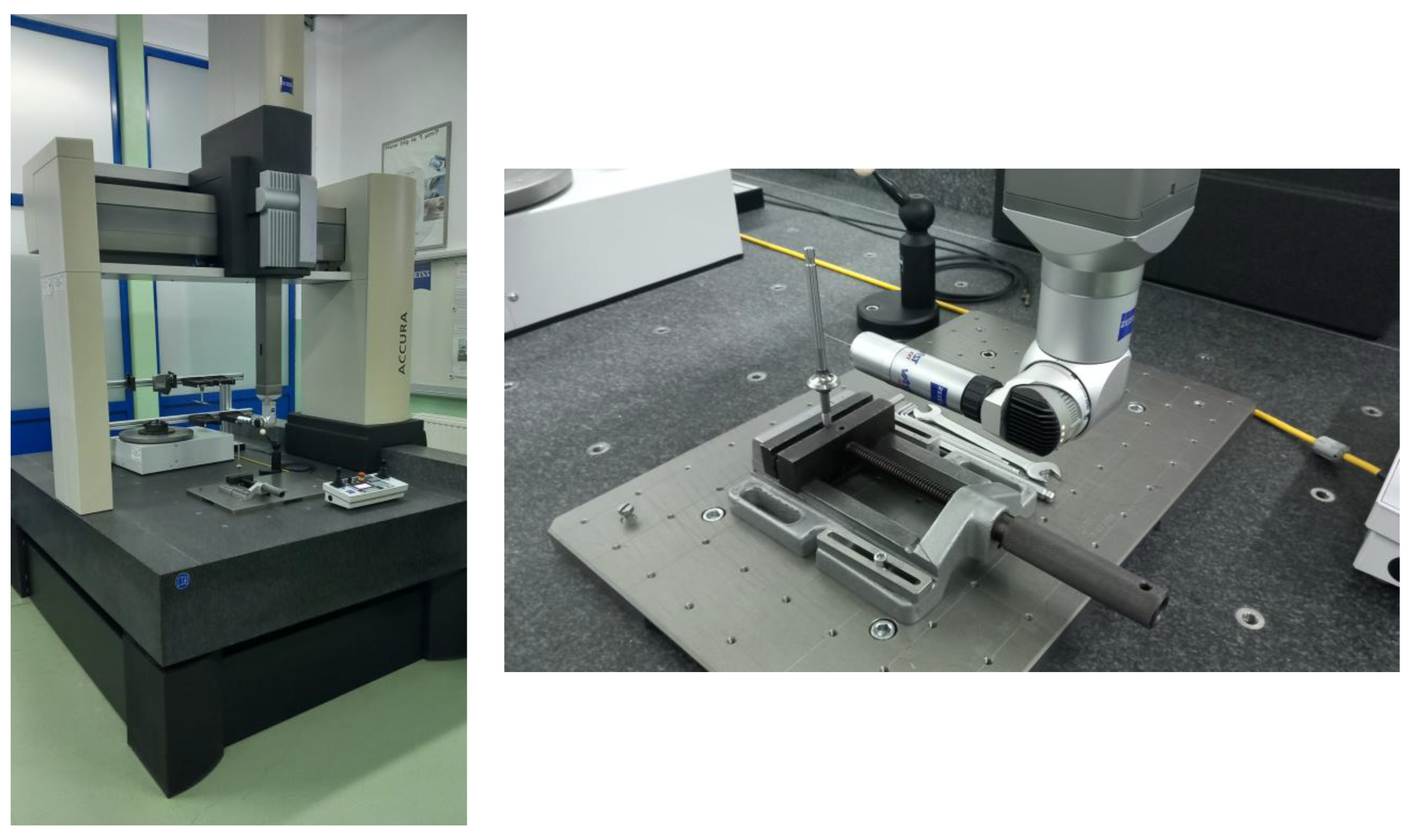

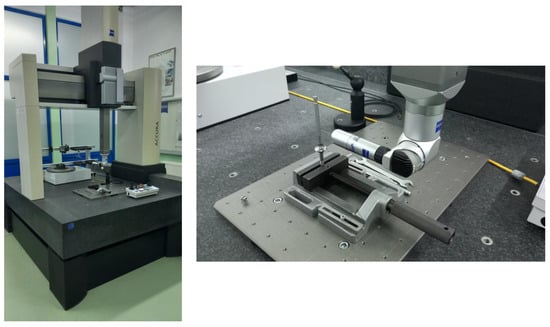

The CMM Accura II was selected as the reference system for this study due to its high precision, characterized by a Maximum Permissible Error (MPE) of E0, MPE = 1.6 + L/333 [µm]. To justify its use as a baseline, an expanded measurement uncertainty budget (U95) was calculated for the critical stem diameter (11 mm), yielding a UCMM ≈ of approximately 1.8 µm. Given that the valve stem’s manufacturing tolerance is ±15 µm (total tolerance zone of 30 µm), the measurement capability ratio is sufficient to treat the CMM data as the reference for comparative analysis with optical systems exhibiting significantly higher uncertainty.

Before measurement, a calibration was performed in accordance with ISO 10360-2:2010 [33] and ISO 10360-5:2020 [34], with the results presented in Table 1. After cleaning, the valve was mounted on a vertical axis using a machine vise on the CMM base plate, supplemented by a MATRIX-type specialized metrological clamping system. This setup ensured the part’s stability during tactile scanning, which is crucial for maintaining the repeatability of results.

Table 1.

Results of the performance verification of the Mahr MarSurf XC 20 system.

The measurement was conducted using a VAST XXT scanning (ZEISS - Germany - Oberkochen) head mounted on an RDS articulating (tilt–rotate) probe head (Figure 3). This configuration enabled the stylus to be positioned perpendicular to the measured side surfaces of the valve. To obtain representative 3D geometry data from 2D profiles, a measurement strategy was implemented that sampled four planes evenly distributed around the circumference at 90° intervals.

Figure 3.

Measurement of Exhaust Valve Profiles on CMM Accura II.

The 2D Curve function was used during measurement to enable precise tracking of the valve’s geometric contour. For each of the four positions, identical and rigorous data-acquisition parameters were applied, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Established measurement parameters for the CMM Accura II.

To obtain the 3D-STL model, instead of directly connecting points into a mesh, geometric fitting algorithms based on the least squares method were applied. Based on the acquired profiles, mathematical solids were defined in Siemens NX (version 23.06.3001) software, such as cylinders for the valve stem and cones for the valve seat. The final 3D-STL model was produced through tessellation, in which the generated CAD surfaces were subdivided into a dense triangular mesh and exported to a binary format. The precision of this transformation was ensured by applying a Chordal Tolerance of 0.0025 mm, which constrained the maximum linear distance between the triangular facets and the nominal CAD surfaces. Furthermore, an Angular Tolerance of 3.0° was applied to refine mesh density in regions of high curvature, such as the transitions between the valve stem and the head, thereby ensuring a smooth surface representation without discretization artifacts. These restrictive parameters were chosen to minimize approximation errors during the tessellation stage, providing a high-fidelity reference model for subsequent metrological comparisons and deviation analysis.

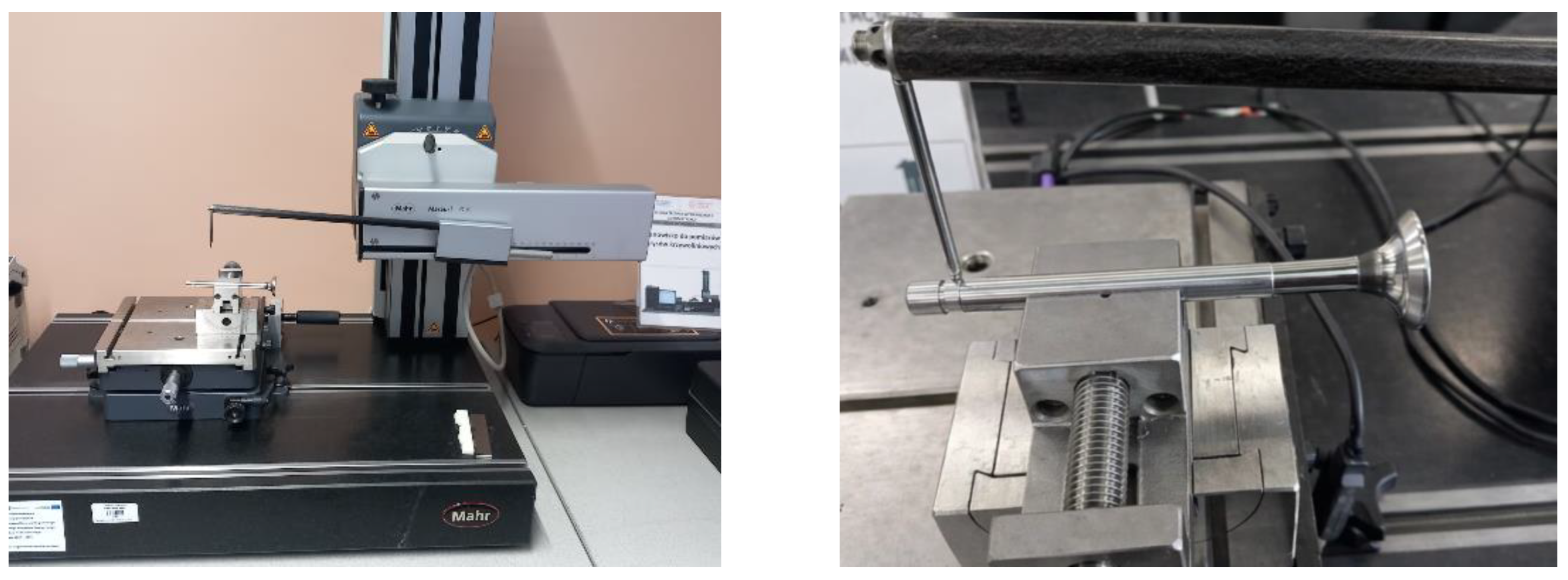

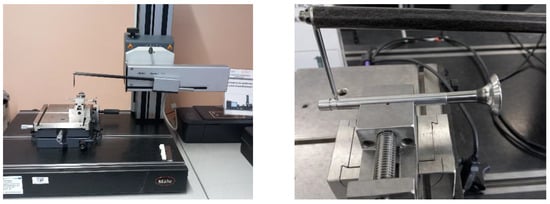

Before measuring the valve with the Mahr Contour Measurement XC 20 system, the system was calibrated. This was carried out in accordance with VDI/VDE 2631 [35] and ISO 12181-1 [36] standards. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The results of verification of the Mahr Contour Measurement XC 20 system using the standard procedure.

The contour of the exhaust valve was measured using the Mahr Contour Measurement XC 20 system in a single-clamping setup, justified by the assumed axial symmetry of the component (Figure 4). This measurement method minimized errors arising from potential shifts. It ensured a more accurate representation of the valve’s geometry along its axis of symmetry. The system was equipped with a carbon fiber arm, which provided high stiffness and low mass, effectively minimizing the influence of vibrations and deformations. To achieve the highest possible precision, the measurement was conducted with a resolution of 0.001 mm and a minimum scanning speed of 0.2 mm/s.

Figure 4.

Measurement of Exhaust Valve Profile on Mahr MarSurf XC 20 Contour Measurement System.

The high-density 2D profile data, consisting of X- and Z-coordinates recorded in MarWin, served as the basis for the subsequent reconstruction of the 3D-STL model. Upon importing the point set into the NX Siemens software, a profile revolution algorithm was applied. The 2D contour was ‘swept’ through 360 degrees around the component’s designated axis of symmetry, creating a precise solid of revolution. This approach eliminated local surface irregularities that could arise from circumferential scanning, ensuring ideal symmetry of the reconstructed geometry. The procedure concluded with the automatic triangulation of the solid’s surfaces, which were exported as a closed shell in the STL format, utilizing the previously defined tessellation parameters to maintain maximum geometric fidelity.

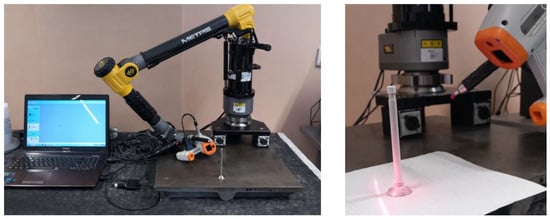

A coordinate measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100) was also used in the geometry reconstruction process. Before taking measurements, the arm and optical system were calibrated. The American standard ASME B89.4.22 [37] was used for the MCA II arm. The laser head calibration process was carried out in accordance with ISO 10360-8 [38]. Based on the tests conducted, the results presented in Table 4 were obtained.

Table 4.

The results of verification of the measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100) system using the standard procedure.

Before measuring the exhaust valve geometry, the surface was cleaned of contamination. Due to the surface reflectivity, it was necessary to coat the model with a Helling 3D matting agent (single coat). The average thickness of the layer applied to the model surface is 0.013 mm [39]. Immediately before measurement, the exhaust valve model was placed on a stable surface (plate) to prevent displacement due to vibrations. The MMD×100 laser scanner is mounted on the MCA II measuring arm, whose components are made of carbon fiber. As a result, the arm is lightweight yet highly durable. It allows the operator to maneuver the laser scanner freely, while minimizing fatigue and increasing measurement precision. It also effectively dampens vibrations, which is essential for maintaining accuracy during scanning and for minimizing vibrations transmitted to the scanning head. This, in turn, translates into a more precise representation of the scanned object. During measurement, laser scanner settings were used to obtain a three-dimensional scan of the digitized object at the highest measurement resolution (Table 5). The system was operated at a sampling frequency of 150 Hz, ensuring a point spacing of 0.01 mm. The environmental conditions were strictly controlled at 20 ± 0.5 °C to mitigate thermal expansion errors of the exhaust valve material (X45CrSi9-3).

Table 5.

Established measurement parameters for the measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100).

The exhaust valve was measured using a single-model setup (Figure 5). This approach avoided errors arising from merging two geometry scans obtained at different positions. The number of geometry scans required per setup was also minimized. Ultimately, three scans were needed to complete the digitalization of the geometry.

Figure 5.

Measurement of the Exhaust Valve geometry on the measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100) system.

The 3D-STL model was generated through direct triangulation algorithms. This process involves connecting the individual points recorded during the laser line sweeps into a network of interconnected triangles. Given the nature of manual laser scanning, which is susceptible to "hand-shake" effects and surface reflections, the algorithm incorporates specific filtering routines to remove "spikes " and redundant data points. The resulting mesh provides a detailed representation of the scanned geometry. However, it requires careful control of point density to ensure structural integrity along the complex edges of the exhaust valve.

The exhaust valve geometry was also measured using the GOM Scan 1 scanner (ZEISS/GOM, Braunschweig/Oberkochen, Germany). The calibration of the GOM Scan 1 scanner was performed in accordance with VDI/VDE 2634-2 [40]. The values obtained during the calibration process are presented in Table 6. The system utilized a fringe projection technology with a calibrated volume of 100 mm × 65 mm × 400 mm. The environmental conditions were strictly controlled at 20 ± 0.5 °C to mitigate thermal expansion errors of the exhaust valve material (X45CrSi9-3).

Table 6.

The results of verification of the GOM Scan1 system using the standard procedure.

When measuring the geometry using the GOM Scan 1 scanner, the exhaust valve model surface was first cleaned of contaminants. Then, due to the reflectivity of the model surface, a Helling 3D anti-reflective coating was applied to it (single coat). The average thickness of the layer applied to the model surface is 0.013 mm [41]; no additional markers needed to be applied to the model surface. To minimize the influence of external factors, the measurement was conducted in an air-conditioned, shaded room. To obtain high-quality data reflecting the geometry of the exhaust valve, parameters were applied that enable measurement with the highest possible resolution (Table 7).

Table 7.

Established measurement parameters for the GOM Scan 1.

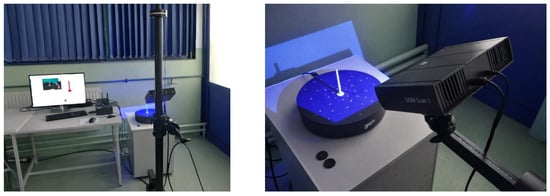

The measurement was performed in a single model setup, with 3 table rotations. Three rotations of the measurement table were entirely sufficient to obtain a complete representation of the exhaust valve’s geometry. When testing two rotations, the resulting three-dimensional point cloud was incomplete. During the measurement, the scanner projects a pattern of light fringes (structured light) onto the object. It then analyzes their distortions using cameras to determine the surface coordinates (Figure 6). Based on phase differences and triangulation, the spatial coordinates of the points are computed, yielding the 3D point cloud.

Figure 6.

Measurement of exhaust valve geometry on GOM Scan 1 system.

The transformation of the acquired point cloud into a 3D-STL model in the GOM Scan 1 system was performed using a voxel-based meshing algorithm. This approach involves partitioning the measurement space into a three-dimensional grid of volumetric units (voxels). By analyzing the point density within each voxel, the algorithm effectively averages measurement noise and filters out local outliers caused by optical reflections. This volumetric reconstruction allows for the generation of a continuous, high-quality polygonal mesh that accurately represents the valve’s surface while maintaining a closed-shell topology, which is essential for precise deviation analysis.

3. Results

The accuracy of the exhaust valve geometry reconstruction was evaluated by comparing measurement data obtained from four systems—the CMM Accura II coordinate measuring machine, the Mahr MarSurf XC 20 profilometer, the MCA-II measuring arm equipped with an MMD×100 laser head, and the GOM Scan 1 structured light scanner. The analysis covered both global surface geometric deviations and selected functional and geometric parameters critical to the valve’s proper operation. In the process of determining the accuracy of the exhaust valve reconstruction process, the deviation in the accuracy of geometric shape mapping was taken into account, as well as the following:

- Global Deviations.

- Stem Diameter: achieving the required accuracy of ±0.015 mm ensures a precise interference fit in the valve guide.

- Stem Straightness: achieving a required deviation of 0.01 mm or less will minimize side stresses and guide wear.

- Seat Angle: achieving the required accuracy in the range of ±15′ is necessary to obtain the optimal contact surface and sealing.

- Face Dimension (Valve Length): achieving the required accuracy in the range of ±0.2 mm affects valve clearance.

The alignment of the acquired point clouds with the nominal CAD geometry was performed using a Global Best-Fit strategy based on the Gauss least-squares criterion. This algorithm iteratively minimizes the objective function, defined as the sum of squared distances between corresponding points of the digitized dataset and the reference surface. Such a global approach is particularly advantageous for the geometry of engine valves; by distributing measurement uncertainties—such as sensor noise or the influence of the anti-reflective coating—across the entire surface, it prevents local geometric features from biasing the overall spatial registration. Furthermore, the least-squares method provides a statistically robust and objective framework for comparing datasets with significantly different point densities, such as those obtained from the GOM Scan 1 and the MMD×100 laser head. For cylindrical components, this strategy ensures stable centering of the valve stem axis, which is critical for the subsequent high-precision assessment of form deviations and surface accuracy. To ensure data consistency and eliminate software-induced bias, all point clouds were exported to a familiar metrological environment, Zeiss Inspect 2023, for final comparative analysis.

3.1. Global Geometric Surface Deviations

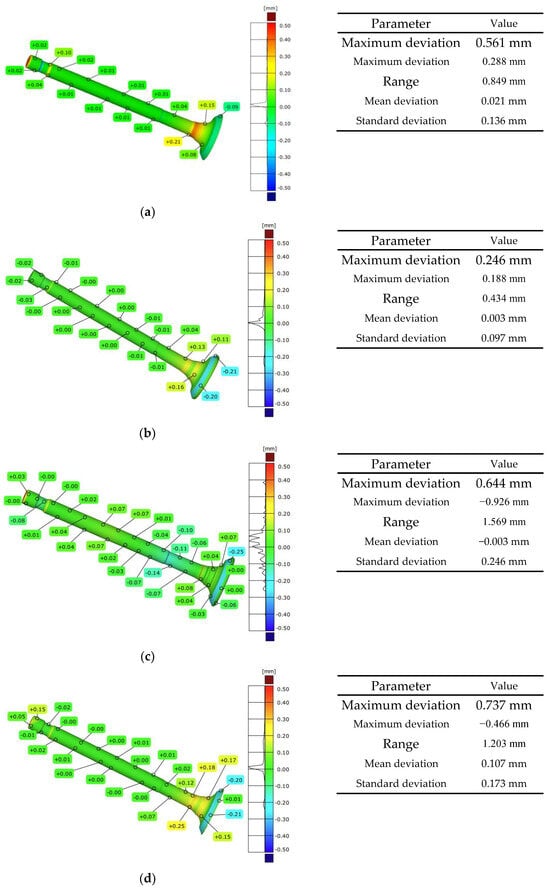

The deviation distributions, along with statistical parameters for the individual measurement systems, are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Global deviations in surface geometry obtained from measurements using: (a) CMM Accura II; (b) Mahr MarSurf XC 20 Contour Measurement System; (c) Measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100) system; (d) the GOM Scan1 system.

For the CMM Accura II, the maximum positive and negative deviations were 0.561 mm and −0.288 mm, respectively, yielding a total deviation of 0.849 mm. The mean deviation reached 0.021 mm, with a standard deviation of 0.136 mm, indicating good stability and repeatability of measurements across the entire valve surface. The smallest deviation range was observed for the Mahr MarSurf XC 20 contour graph. The maximum deviations were 0.246 mm and −0.188 mm, respectively, yielding a total range of 0.434 mm. The mean deviation was close to zero (0.003 mm). In contrast, the standard deviation was 0.097 mm, confirming the high accuracy of tactile profile measurements for axisymmetric geometries. For the MCA-II measuring arm with the MMD×100 laser scanner, the most significant dispersion of deviations was observed. The maximum positive deviation was 0.644 mm, while the negative was −0.926 mm, giving the widest deviation range of 1.569 mm. Despite this, the mean deviation was close to zero (−0.003 mm), whereas the standard deviation increased to 0.246 mm, indicating greater measurement noise and local reconstruction discontinuities. The GOM Scan 1 scanner was characterized by maximum deviations of 0.737 mm and −0.466 mm, corresponding to a total range of 1.203 mm. The mean deviation was 0.107 mm, and the standard deviation was 0.173 mm. These results indicate a systematic shift relative to the nominal model, which may be attributable to surface preparation and optical measurement conditions. The results evaluating global deviations for the measurement systems selected in the research process indicate that tactile methods exhibit significantly more minor global deviations than optical methods, and they also show lower dispersion of deviation values across the entire model surface.

To verify whether the observed differences between the measurement systems were statistically significant, a significance test was performed. First, Levene’s test was conducted to assess the equality of variances. The test confirmed that the variances across the groups were significantly different (p < 0.05), which corresponds to the wide range of standard deviations observed (from 0.097 mm for the Mahr system to 0.246 mm for the MCA-II). Due to the violation of the homogeneity of variances assumption, Welch’s ANOVA was employed instead of the standard one-way ANOVA. The analysis confirmed that the differences in measurement accuracy between the systems are statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Subsequently, a Games–Howell post hoc test was applied to identify specific differences between pairs of systems. The analysis revealed no statistically significant difference between the tactile methods (CMM Accura II and Mahr MarSurf XC 20) (p > 0.05), confirming their high mutual consistency. However, statistically significant differences were found between the reference CMM system and the optical solutions. Specifically, the GOM Scan 1 system exhibited a statistically significant mean shift relative to the reference, likely attributable to the systematic offset introduced by the anti-reflective coating. In the case of the MCA-II arm, the statistical analysis confirmed that its variance is significantly higher than that of the tactile systems, indicating lower repeatability of the measurement process.

3.2. Accuracy of Reconstruction of Selected Geometric Parameters

In addition to analyzing global geometric deviations, the accuracy of reproduction of selected functional and geometric parameters critical to the proper operation of the exhaust valve was evaluated. The analysis covered parameters directly influencing valve guidance, system tightness, and assembly conditions, namely stem diameter, stem straightness, seat angle, and total valve length.

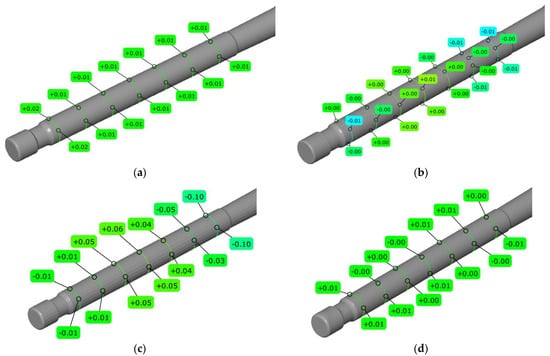

The accuracy of stem diameter reconstruction was evaluated with a tolerance of ±0.015 mm, which is critical for proper valve fit within its guide. As shown in Figure 8a,b, the contact methods—CMM Accura II and Mahr MarSurf XC 20—produced results that fell entirely within the required tolerance range across the entire length of the stem. This high level of accuracy was also observed for the GOM Scan 1 optical system (Figure 8d). In contrast, the results for the laser scanner (Figure 8c) revealed local exceedances of the permissible diameter values. The observed inaccuracies are primarily attributable to the difficulty of capturing rapidly changing geometry due to surface curvature, as well as significant challenges in stitching data across the boundaries of different geometric features during point cloud alignment. Furthermore, the results may have been influenced by optical artifacts at the edges of the metallic surface due to light reflection. It is also essential to consider the impact of the anti-reflective spray applied to the valve. Although necessary for optical measurement of metallic parts, the coating thickness can introduce subtle dimensional offsets or slightly blur the sharpness of geometric transitions, contributing to the local exceedances observed in the laser scan data.

Figure 8.

Stem diameter obtained from measurements using (a) CMM Accura II; (b) Mahr MarSurf XC 20 Contour Measurement System; (c) Measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100) system; and (d) the GOM Scan1 system.

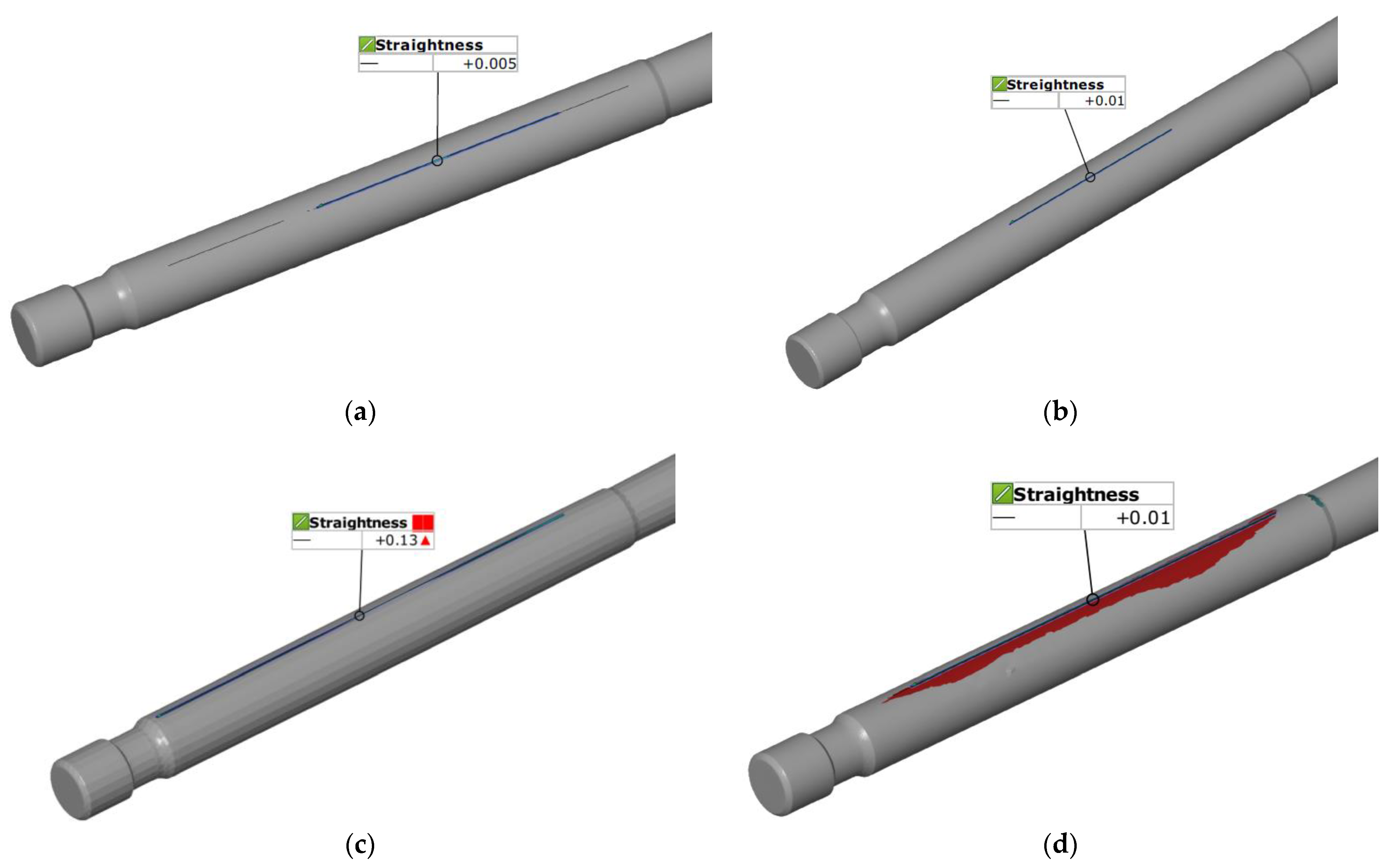

Stem straightness was evaluated against an acceptance criterion of ≤0.01 mm. The Chebyshev criterion (Minimum Zone Tolerance) was applied to determine the deviation values. Both contact methods demonstrate that the valve stem meets the strict straightness requirement (Figure 9a,b). The measurement curves remain stable and fluctuate well within the 0.01 mm limit. These results confirm the component’s high geometric quality as measured by high-precision tactile sensors. The structured light scanner GOM Scan 1 also demonstrates high compliance with the criteria (Figure 9d). Although the signal exhibits higher-frequency noise than contact methods, the overall trend of the curve remains within the 0.01 mm threshold, making it a reliable optical alternative for this parameter. The results from the laser head system indicate that it is the most sensitive to external factors (Figure 9c). The graph shows several instances in which the recorded values approach or exceed the 0.01 mm acceptance criterion, particularly at the beginning and end of the measurement path. This discrepancy is primarily attributable to the application of an anti-reflective spray layer, in which the uneven coating thickness can artificially increase the recorded straightness deviation. Furthermore, inherent point cloud noise typical of optical systems generates measurement “spikes” that frequently exceed the narrow acceptance threshold. These issues are exacerbated by boundary effects, which represent the persistent difficulty of maintaining optical accuracy near the geometric transition between the valve head and the stem.

Figure 9.

Stem straightness obtained from measurements using (a) CMM Accura II; (b) Mahr MarSurf XC 20 Contour Measurement System; (c) Measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100) system; and (d) the GOM Scan1 system.

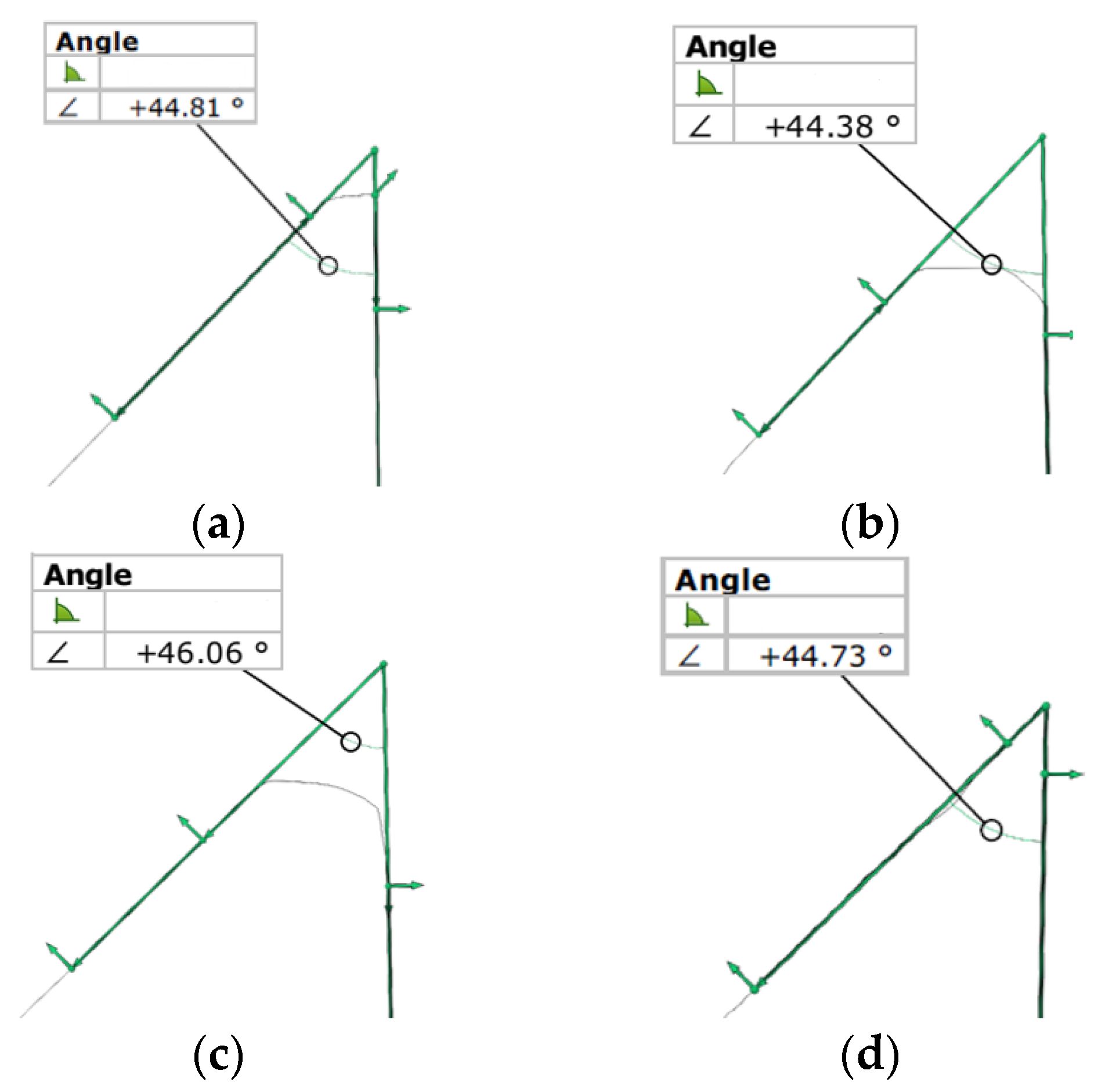

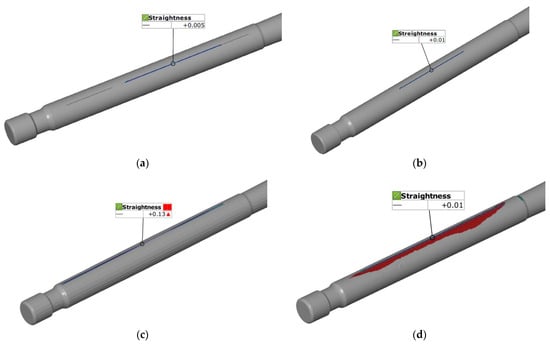

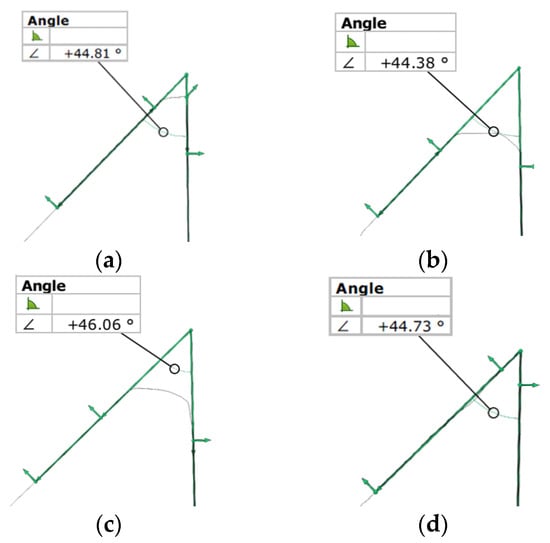

The analysis of the seat angle measurement results, as presented in Figure 10a–d, is critical because this parameter directly determines the combustion chamber’s tightness. The tactile methods demonstrate exceptionally high measurement stability. Their deviation profiles exhibit a flat trajectory, remaining almost entirely within a very narrow range. These methods benefit from the mechanical filtering effect of the measuring probe, which enables precise reproduction of the valve seat cone geometry while effectively eliminating the influence of surface roughness on the angular measurement. Regarding the optical systems, the structured light scanner exhibits a higher noise level than the tactile methods, manifested by minor oscillations in the graph (Figure 10d). Nevertheless, the overall trend and deviation values remain consistent with the reference results from the CMM, suggesting that this method is sufficiently accurate for seat angle inspection. In contrast, the laser scanning results (Figure 10c) display the most significant disturbances, including prominent spikes and fluctuations, particularly at the seat edges. These artifacts are characteristic of laser scanning on inclined and narrow surfaces, where light scattering at geometric boundaries often leads to inconsistencies in the data. Furthermore, the accuracy of the optical results is heavily influenced by the application of the anti-reflective spray; any uneven accumulation of the coating on the narrow seat surface can introduce angular errors of several arcminutes. Consequently, while optical methods enable rapid data acquisition, tactile methods remain the primary reference for functional seal assessment because they more accurately capture the valve seat’s contact profile.

Figure 10.

Seat angle obtained from measurements using (a) CMM Accura II; (b) Mahr MarSurf XC 20 Contour Measurement System; (c) Measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100) system; and (d) the GOM Scan1 system.

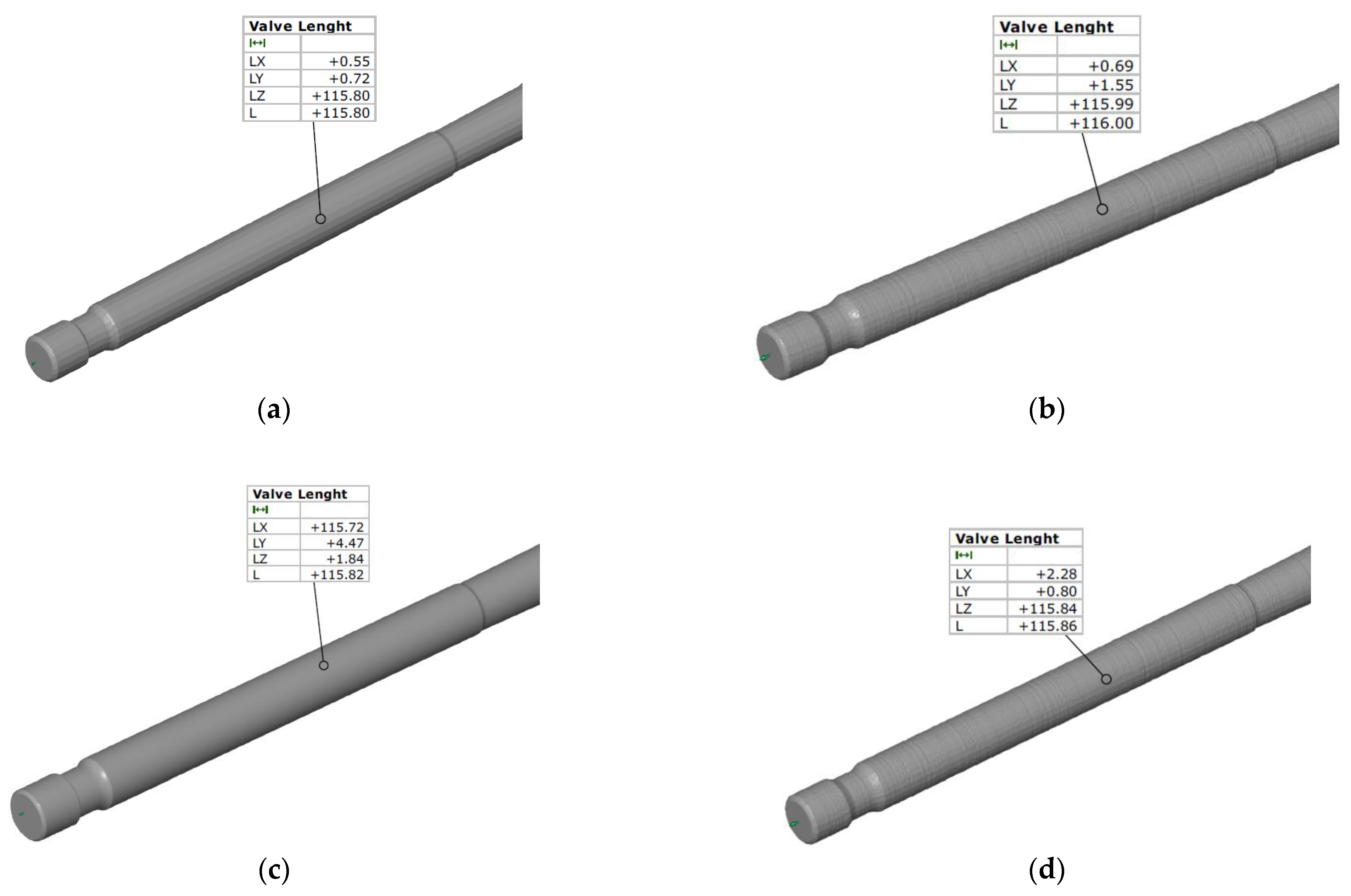

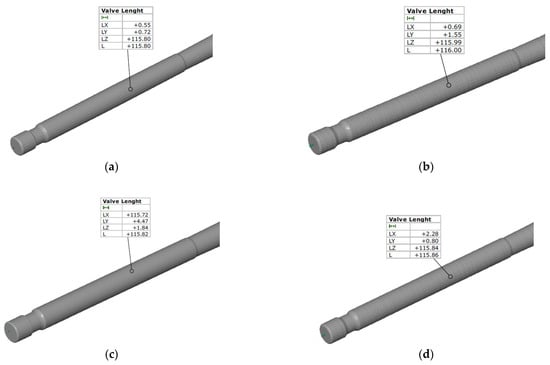

Length measurements of the exhaust valve, performed using four different metrological technologies, demonstrate varied deviations from the nominal value and mutual differences in the interpretation of the object’s geometry. The highest alignment with the nominal dimension was achieved by the contour graph (Figure 11b), which indicated a value of exactly 115.99 mm. However, the model generated by this device exhibits distinct surface roughness on the stem, suggesting that this measurement is susceptible to local material structure. The other three methods yielded results below the nominal value, indicating a negative manufacturing deviation for the valve. The lowest value, 115.80 mm, was recorded for the CMM (Figure 11a). This result, obtained via a tactile method, is considered the most stable reference point, showing a deviation of −0.20 mm relative to the nominal. The laser scanner (Figure 11c) yielded a result very close to the CMM, indicating a length of 115.72 mm, while maintaining the most smoothed visual model of the part. The final method, structured light scanning (Figure 11d), yielded a value of 115.84 mm. The model in this report features a dense mesh structure, which enables precise analysis of the topography of the entire valve surface, but results in a slightly higher length measurement than that obtained with the laser or CMM due to the inclusion of surface micro-irregularities.

Figure 11.

Face dimension (valve length) obtained from measurements using (a) CMM Accura II; (b) Mahr MarSurf XC 20 Contour Measurement System; (c) Measuring arm (MCA-II) with a laser head (MMD×100) system; and (d) the GOM Scan1 system.

The obtained results clearly indicate that tactile measurement methods provide higher accuracy and lower dispersion of deviations in the process of reconstructing the axisymmetric geometry of the exhaust valve (Table 8). Among the analyzed systems, the best results were achieved for the Mahr MarSurf XC 20 contourgraph, both in terms of global surface deviations and the accuracy of functional parameters. While optical methods enabled faster digitalization of the whole geometry, they were characterized by a broader range of deviations and reduced accuracy in key functional areas.

Table 8.

Assessment of meeting tolerance requirements for the analyzed measurement systems.

4. Discussion

The observed discrepancies in the geometry reconstruction of the exhaust valve, obtained through various measurement methods, align with trends documented in the literature on reverse engineering processes and on the comparison of tactile versus optical methods. These findings are consistent with recent systematic reviews on digital model reconstruction for mechanical components, which emphasize the importance of geometric and functional quality in remanufacturing [42]. Numerous studies indicate that the accuracy of geometric reconstruction is heavily dependent on the measuring system’s operating principle, the nature of the measured surface, and the subsequent data-processing stages [22,26,28]. Tactile methods, such as those performed on coordinate measuring machines (CMM) and contour graphs, are widely recognized as reference solutions for geometric accuracy [5,7,19]. Direct contact between the measuring tip and the surface eliminates errors characteristic of optical methods, including light reflection, variable incidence angles, and the optical properties of the surface itself [20,22]. This is evidenced by the smallest range of global deviations and the highest consistency of functional parameters in contour measurements [5,22]. These discrepancies stem primarily from fundamental differences in the physics of data acquisition and like sensor-surface interaction. In tactile methods, such as the CMM Accura II or Mahr MarSurf XC 20, physical contact between the measuring tip and the surface eliminates errors associated with material color or light scattering. Furthermore, the ruby ball acts as a natural mechanical filter, stabilizing results by bypassing surface microporosities. In contrast, optical systems record reflected light; on highly reflective metallic valve surfaces, this generates significant measurement noise and characteristic “spikes”, which inflate the recorded maximum deviations.

4.1. Factors Determining Accuracy

A critical factor influencing these results is the requirement for surface preparation before optical measurements, including the application of anti-reflective matting coatings. As emphasized by [26,29], these layers introduce a systematic shift in the actual surface (the so-called offset). At the same time, their thickness and uniformity are difficult to account for unambiguously in the error-compensation process. In the present study, this phenomenon directly contributed to shifts in mean deviations and to an increased range of global deviations for the optical methods. Although the average coating thickness is approximately 0.013 mm [39], its impact on measurement error is complex. A distinction must be made between the nominal layer thickness, which theoretically constitutes a correctable systematic error, and the stochastic nature of manual spray application. Uneven accumulation of the matting material, particularly in areas of high curvature—such as filet radii or the valve seat—generates local geometric distortions that cannot be eliminated through simple constant-offset filtering. Additionally, at junctions between surfaces (e.g., the valve stem and head), the spray coating may thicken in concave corners, thereby exacerbating errors in reconstructing functional features. In the case of laser and structured light systems, these errors are further amplified by optical principles, on edges and highly inclined surfaces (such as the valve seat face), and multipath interference occurs. This leads to artifacts in the point cloud and a characteristic "rounding" effect of sharp geometric transitions. Consequently, despite the use of matting, optical methods demonstrated a lower ability to maintain rigorous dimensional tolerances than tactile methods, which measure the bare metal without introducing an additional material barrier. The deeper analysis of the results suggests that the measurement uncertainty is not solely a function of the sensor’s resolution but is heavily influenced by the spatial distribution of errors. While the GOM Scan 1 showed a consistent systematic offset of +0.013 mm due to the matting layer, its standard deviation remained low, indicating high process stability. In contrast, the MCA-II system exhibited high stochastic noise (spikes), which is evidenced by the maximum deviation reaching 1.569 mm. This behavior is physically linked to the triangulation instability when the laser beam interacts with the complex micro-geometry of the valve seat, where multiple reflections occur. This distinction between systematic bias (correctable) and stochastic noise (non-correctable) is crucial for evaluating the technical safety of the reconstructed parts. To address these limitations, the challenge of compensating for such systematic errors is increasingly being met through the application of Artificial Intelligence. Specifically, neural network-based models now allow for adaptive improvement in optical measurement accuracy by intelligently predicting offsets that traditional filtering fails to capture [43]. Furthermore, utilizing hybrid machine learning frameworks to predict geometric deviations from 3D surface metrology data represents a promising direction for minimizing the impact of both the coating’s stochastic nature and optical artifacts in high-precision components [44].

In addition to the influence of the matting coating, a significant source of error in optical systems (GOM Scan 1 and MCA-II) is physical phenomena occurring at edges and surfaces that are highly inclined relative to the sensor’s optical axis. This phenomenon, characterized by increased measurement noise and the apparent "rounding" of sharp edges, is explained by fundamental principles of optics and triangulation. At geometric edges and in areas of concave transitions (e.g., the filet radius under the valve head), the phenomenon of multipath interference dominates. In such locations, the structured light or laser beam undergoes multiple secondary reflections before returning to the detector. Point reconstruction algorithms, which assume a single direct reflection from the measured surface, misinterpret these distorted signals, thereby generating artifacts and points that lie outside the part’s actual contour. In the case of inclined surfaces, such as the valve seat face, the geometry of the light spot projection and the change in reflected radiation intensity (in accordance with Lambert’s cosine law) are of critical importance. As the surface inclination angle relative to the sensor increases, the projected pixel or laser line undergoes elongation, which drastically reduces the local information density and spatial resolution. This makes it difficult for optical systems to precisely determine the center point of the reflected beam, which in this study translated into larger form deviations in the valve seat area compared to precise tactile measurements. Tactile methods, operating independently of the optical and directional characteristics of the surface, allowed for stable results even in areas with such complex geometry.

The measurement strategy and the structural stability of the measuring systems played a significant role in the achieved results. Literature indicates that errors resulting from the registration and merging of multiple point clouds represent one of the primary limitations of optical methods, particularly for components requiring high co-axiality [26,27]. This challenge underscores the need for hybrid mode sensor fusion, which integrates data from different sensors to improve overall positioning and measurement accuracy [45]. Beyond the physical measurement, the process of converting raw data into 3D-STL models constituted a critical stage of the metrological workflow, generating derivative errors with varying characteristics. As demonstrated by [9,27], the process of point cloud approximation and parametric surface fitting is a significant source of error, especially for data burdened by measurement noise. Optical methods, requiring intensive data filtration and smoothing, proved to be more susceptible to these types of errors than tactile methods, where the scope of necessary data processing was limited. In the CMM Accura II contact system, post-processing did not rely on direct point cloud triangulation but rather on advanced geometric feature synthesis. Based on the gathered points, mathematically ideal solids were defined using the Gaussian algorithm (least squares method), which allowed the fitting error to be limited to below 0.003 mm. Although this method effectively eliminated measurement noise, it could potentially mask local surface micro-damage. The final 3D-STL model was created by tessellating these solids using a rigorous chordal tolerance of 0.0025 mm, rendering the arc approximation error negligible. Stitching errors were completely eliminated by calculating the contact edges as mathematical function intersections. Similar stability was demonstrated for the Mahr MarSurf XC 20 system, where the reconstruction process was based on the profile revolution method. Post-processing utilized precision 2D profiles, which were rotated around a symmetry axis defined by the valve stem. The primary source of error at this stage was the mathematical determination of the rotation axis (alignment error), generating deviations in the range of 0.005–0.01 mm. By generating the mesh from an averaged profile, the STL model was free from stitching errors, and the tessellation error during export was maintained at 0.005 mm. In contrast, for the GOM Scan 1 scanner, data processing was more complex and susceptible to errors characteristic of optical systems. A voxel-based meshing algorithm was applied; while it effectively removed noise by averaging data from overlapping scans, it simultaneously caused edge rounding. This error was estimated at 0.02 mm in the valve seat area. Furthermore, the post-processing had to account for a systematic offset resulting from the necessary surface matting spray (approx. 0.013 mm), which directly shifted the mean deviation values. The most significant impact of post-processing on accuracy degradation was observed for the MCA-II system with the MMD×100 head. The largest dispersion of results recorded for this measuring arm (reaching a range of 1.569 mm) was a direct consequence of both manual operation and subsequent data treatment. Operator-induced vibrations and the lower rigidity of the arm compared to a stationary, bridge-type CMM introduced significant measurement uncertainty. However, the direct triangulation process itself required intensive filtration of “spikes” and redundant points, generating local errors of up to 0.1 mm. The necessity of stitching discontinuous point clouds, combined with the use of hole-filling and smoothing algorithms, significantly distorted the model geometry. These operations on the raw data, rather than the sensor resolution itself, were the primary cause of the widest result dispersion. This confirms that while optical systems facilitate rapid digitization and Industry 4.0 integration, they require rigorous validation and a hybrid approach when applied to high-precision functional components to ensure absolute technical safety. The justification for the higher consistency of results in the CMM and Mahr systems lies in their ability to ignore surface-level optical artifacts. By utilizing the Gaussian least-squares method for geometric feature synthesis, these systems effectively average out local surface roughness, providing a stabilized reference. The optical systems, however, capture the "envelope " of the surface, including the spray coating and reflected light artifacts. Consequently, the observed discrepancies are not merely measurement errors but reflect different metrological definitions of the physical surface, which must be accounted for during the CAD model convergence phase.

4.2. Industrial Implications

The analysis of the tabulated results yields critical insights into the selection of metrological technologies for the reverse engineering and manufacture of high-precision components, specifically engine valves. The CMM Accura II confirms its role as a robust foundation for quality assurance, particularly where the precise determination of angular relationships—such as the seat angle—is paramount. However, its marginal (borderline) performance regarding stem diameter suggests that, in industrial settings, maintaining micrometer-level tolerances requires rigorous calibration protocols and stringent thermal stabilization. Conversely, the Mahr MarSurf XC 20 demonstrates superior efficacy in monitoring finishing operations, such as grinding, where linear precision of the stem is the primary metric. This renders it the optimal solution for in-process inspection stations. Significant implications also arise from the GOM Scan1 results; as an optical solution, it rivals the precision of tactile methods across most parameters. Within the framework of Industry 4.0, this facilitates accelerated digitization and modeling without a critical compromise in accuracy, though angular features may still necessitate tactile verification. At the opposite end of the performance spectrum, the MCA-II system (MMD×100 head) proved entirely inadequate relative to the prescribed tolerances. This serves as a definitive caveat for engineers: mobile measuring arms equipped with this class of laser scanner lack the resolution and stability required for high-precision mechanical reconstruction. Utilizing such systems for critical mating components in the aerospace or automotive sectors could result in catastrophic engine failure due to seal compromise or component seizure. Consequently, an optimized industrial strategy should adopt a hybrid methodology, leveraging the throughput of optical scanning (GOM) for macro-geometry and the superior precision of tactile/profilometric systems (CMM, Mahr) for critical functional features. Such a transition towards integrated metrology for advanced manufacturing is essential to overcome current limitations in precision inspection [43]. Moreover, implementing intelligent positioning through AI-enhanced metrology allows for more adaptive and robust quality control in automated environments [45].

Based on the developed results, it is possible to propose an inspection procedure for the quality department that optimizes measurement cycle times while maintaining absolute technical integrity. Developing this optimal procedure requires the implementation of a hybrid approach, which integrates the rapid 3D data acquisition of optical systems with the metrological precision of tactile devices:

- Phase 1: Preliminary Screening & General Geometry Reconstruction. The GOM Scan1 system should be utilized in the initial stage. Due to its capability to rapidly generate point clouds and perform CAD-to-part comparisons, this system enables the instantaneous detection of gross dimensional deviations. This stage allows for the immediate assessment of material allowances on surfaces such as the valve face (Face dimension), significantly reducing the time required for the initial inspection phase;

- Phase 2: High-Precision Verification of Critical Parameters. the Mahr MarSurf XC 20 plays a pivotal role and should be dedicated exclusively to the verification of stem diameter and straightness. Given that this system is best equipped to handle tight tolerances of ±0.015 mm, its application eliminates the risk of a “borderline” error, which typically occurs when utilizing a CMM for this specific parameter. Simultaneously, to ensure the total sealing integrity of the combustion chamber, the final verification of the seat angle must be performed on the CMM Accura II. As the only system that achieved an unambiguous “PASS” result for this parameter, the CMM guarantees that the valve-to-seat contact geometry is ideal, thereby preventing subsequent valve seat burning.

Implementing the hybrid strategy allows for replacing time-consuming, full CMM scanning (40 min) with rapid optical scanning for global geometry (20 min) and targeted profilometer checks (6 min). This results in a theoretical time saving of approximately 35%, confirming the efficiency gains observed in this study (Table 9).

Table 9.

Comparison of total inspection times (average per part).

Simultaneously, the total exclusion of MCA-II class systems from this procedure for high-precision features eliminates the risk of allowing defective parts into service, which remains a cornerstone of modern quality management in the automotive industry. A process structured in this manner closes the feedback loop between reverse engineering and rigorous technical inspection, ensuring the highest degree of technical safety for the reconstructed part. Furthermore, the integration of these metrological data flows facilitates the creation of a Metrology and Manufacturing-Integrated Digital Twin (MM-DT), enabling continuous monitoring of the component’s functional quality throughout its lifecycle [46].

Although this research focused on a specific type of exhaust valve, the conclusions regarding the performance and limitations of the evaluated metrology systems possess broader industrial applicability. The exhaust valve was selected as a representative benchmark due to its complex combination of high-precision functional surfaces (the stem and seat) and more complex, non-functional transition zones. The observed characteristics, such as the systematic measurement offset in optical systems caused by the anti-reflective coating or the significantly higher data dispersion in laser-based articulated arms (MCA-II), are inherent to the sensor technologies rather than the specific geometry of the part. Consequently, these findings can be generalized to a wide range of precision-machined, rotationally symmetrical components in the automotive and aerospace sectors, including turbocharger shafts, fuel injectors, and small hydraulic pistons. For such components, the recommendation to utilize hybrid metrology—combining the speed of optical scanning with the micrometer-level reliability of tactile probing for critical tolerances—remains a robust strategy for ensuring both efficiency and technical safety in reverse engineering processes.

However, the implementation of such a hybrid methodology in a real manufacturing environment faces specific practical limitations. The primary constraint is the equipment cost; maintaining both a high-precision CMM and an industrial-grade structured light scanner requires a significant initial capital investment, which may be prohibitive for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). From an implementation perspective, integrating data flows from two disparate software ecosystems (e.g., tactile measurement software and optical inspection suites) requires robust IT infrastructure to ensure seamless data exchange and integrity. Furthermore, personnel training requirements increase substantially. The hybrid approach demands operators with dual competencies: deep metrological knowledge for CMM operation (GD&T interpretation, probe qualification) and advanced digital skills for optical scanning (surface preparation strategy, point cloud processing, and mesh alignment). Finally, unlike fully optical solutions that may operate near the production line, the inclusion of the CMM component mandates strict environmental controls—specifically a temperature-stabilized laboratory to guarantee the micrometer-level accuracy required for critical features like the valve stem and seat.

5. Conclusions

The comparative analysis of contact and optical measurement systems for the reconstruction of exhaust valve geometry leads to the following conclusions:

- Tactile measurement systems (CMM Accura II and Mahr MarSurf XC 20) demonstrate the highest precision, with the lowest global surface deviations and minimal dispersion of results. These systems remain the “gold standard” for verifying critical functional dimensions such as the valve stem and seat.

- Optical systems (GOM Scan 1 and MCA-II) offer significantly faster data acquisition and provide a comprehensive view of the geometry (global deviation maps). However, they are more susceptible to systematic errors, such as the offset introduced by anti-reflective coatings (matting sprays).

- The statistical analysis confirmed significant differences between measurement systems (p < 0.001). While the two tactile methods are statistically consistent with each other, optical methods show significant deviations from the reference CMM, requiring careful calibration and software compensation.

- For high-performance automotive components, a hybrid approach is recommended: using optical scanning for general shape reconstruction and tactile methods for critical tolerances and functional surfaces.

Despite the rigorous experimental setup, certain limitations of this study must be acknowledged. The research focused on a single type of exhaust valve geometry, whereas different materials or surface finishes, such as highly polished metals or ceramic coatings, might affect optical sensor performance differently. Furthermore, the analysis was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, meaning that environmental factors typical of production halls, such as variable ambient light or humidity, were not fully explored. Finally, this study did not account for the long-term wear and tear of tactile probes, which may influence measurement stability in continuous industrial use.

Building on these findings, prospective research should focus on several key areas to further advance the field of high-precision metrology. One promising direction is the automation of hybrid metrology through the development of algorithms for the automatic fusion of point clouds from tactile and optical sensors, aiming to create a single, high-fidelity digital representation. Additionally, there is significant potential in AI-driven error compensation; by implementing machine learning algorithms, it becomes possible to automatically filter measurement noise and predictively remove systematic offsets, such as the "spray-layer " effect, based on local surface curvature. Such advancements pave the way toward fully automated, self-correcting reverse engineering frameworks—effectively evolving into dynamic Digital Twins for powertrain components. Lastly, expanding this research to include a greater diversity of materials, such as advanced composites and ceramic components used in the aerospace industry, would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the versatility and robustness of the proposed methodology in demanding industrial environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T. and J.T.; methodology, P.T., J.T. and P.H.; software, J.T., P.H. and J.M.; formal analysis, P.T.; investigation, P.T., J.T., P.H. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T., J.T., P.H. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, P.T.; visualization, P.T.; supervision, P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Raja, V. Introduction to reverse engineering. In Reverse Engineering: An Industrial Perspective; Raja, V., Fernandes, K.J., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, S.; Lotufo, R.; Berger, T.; Wąsowski, A.; Czarnecki, K. Reverse engineering feature models. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Software Engineering, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–28 May 2011; pp. 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, A.; Nayak, Y.; Ganapathy, A.K.; Chen, D.; Tappa, K.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Ballard, D.H. Reverse engineering and 3D printing of medical devices for drug delivery and drug-embedded anatomic implants. Polymers 2023, 15, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakjira, Y.; Kurukkal, N.S.; Lemu, H.G. Reverse engineering in medical application: Literature review, proof of concept and future perspectives. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapinski, B.; Wieczorowski, M.; Marciniak-Podsadna, L.; Dybala, B.; Ziolkowski, G. Comparison of different method of measurement geometry using CMM, optical scanner and computed tomography 3D. Procedia Eng. 2014, 69, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Longstaff, A.P.; Fletcher, S.; Myers, A. Integrated Tactile and Optical Measuring Systems in Three Dimensional Metrology; University of Huddersfield: Huddersfield, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xian, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Kang, M. Use of coordinate measuring machine to measure circular aperture complex optical surface. Measurement 2017, 100, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, H. Research on Triangulation Method of Object Surface with Holes in Reverse Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Software Engineering, Wuhan, China, 11–13 December 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. An adaptive process of reverse engineering from point clouds to CAD models. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 33, 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, P.; Bezłada, W.; Cierpisz, K.; Dubiel, K.; Frydrych, A.; Misiura, J. Analysis of the accuracy of CAD modeling in engineering and medical industries based on measurement data using reverse engineering methods. Designs 2024, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutak, J.S.; Wiech, J. Horizontal automated storage and retrieval system. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2017, 11, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutak, J.S.; Kołodziej, W. Device to rehabilitate one’s Physical and Learning Abilities. Teh. Vjesn. 2018, 25, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M. Additive manufacturing applications in industry 4.0: A review. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2019, 4, 1930001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefan, K.; Janette, B. Reverse engineering in automotive design component. Industry 4.0 2022, 7, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sikulskyi, V.; Maiorova, K.; Voronko, I.; Kapinus, O.; Skyba, O. Coordination in prototyping high-precision composite aviation parts with connectors and joints based on reverse engineering. Aerosp. Techn. Technol. 2024, 6, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milde, J.; Dubnicka, M.; Buransky, I. Impact of powder coating types on dimensional accuracy in optical 3d scanning process. MM Sci. J. 2023, 2023, 6800–6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dúbravčík, M.; Kender, Š. Application of reverse engineering techniques in mechanics system services. Procedia Eng. 2012, 48, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozesara, M.; Ghazinoori, S.; Manteghi, M.; Tabatabaeian, S.H. A reverse engineering-based model for innovation process in complex product systems: Multiple case studies in the aviation industry. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2023, 69, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, A.; Magdziak, M. Usability assessment of selected methods of optimization for some measurement task in coordinate measurement technique. Measurement 2012, 45, 2330–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, D.M.; Mahmood, A.Z. Improving Reverse Engineering Processes by using Articulated Arm Coordinate Measuring Machine. Al-Khwarizmi Eng. J. 2020, 16, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, P.; Jędras, J. Precision analysis of chain wheel geometry reconstruction based on contact and optical measurement data. J. Eng. Manag. Syst. Eng. 2023, 2, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Barbero, B.R.; Ureta, E.S. Comparative study of different digitization techniques and their accuracy. Comput. Des. 2011, 43, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relvas, C.; Ramos, A.; Completo, A.; Simões, J.A. Accuracy control of complex surfaces in reverse engineering. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2011, 12, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.F.; Jin, J.S.; Wang, M.J.; Jiang, W.; Gao, L.; Xiao, L. A review of algorithms for filtering the 3D point cloud. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2017, 57, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, P.; Bielarski, P.; Czapla, A.; Futoma, H.; Hajder, T.; Misiura, J. Assessment of Accuracy in Geometry Reconstruction, CAD Modeling, and MEX Additive Manufacturing for Models Characterized by Axisymmetry and Primitive Geometries. Designs 2025, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizin, M.; Paryanto, P.; Cahyo, N.; Rusnaldy, R. Investigating the accuracy of boat propeller blade components with reverse engineering approach using photogrammetry method. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.H. A review on shape engineering and design parameterization in reverse engineering. In Reverse Engineering—Recent Advances and Applications; Alexandru, C., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, E. Reverse engineering applications for recovery of broken or worn parts and re-manufacturing: Three case studies. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2009, 40, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palousek, D.; Omasta, M.; Koutny, D.; Bednar, J.; Koutecky, T.; Dokoupil, F. Effect of matte coating on 3D optical measurement accuracy. Opt. Mater. 2015, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonamici, F.; Carfagni, M.; Furferi, R.; Governi, L.; Lapini, A.; Volpe, Y. Reverse engineering of mechanical parts: A template-based approach. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2018, 5, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isermann, R. Engine Modeling and Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, P.; Hollman, P.; Jacobson, S. Wear mechanism study of exhaust valve system in modern heavy duty combustion engines. Wear 2011, 271, 2477–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10360-2:2009; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMM)—Part 2: CMMs Used for Measuring Linear Dimensions. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- ISO 10360-5:2020; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Systems (CMS)—Part 5: Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) Using Single and Multiple Stylus Contact Probing Systems Using Discrete Point and/or Scanning Measuring Mode. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- VDI/VDE 2631; Form Measurement—Virtual Coordinate Measuring Machines. Association of German Engineers (VDI/VDE): Düsseldorf, Germany, 2011.

- ISO 12181-1:2011; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Roundness—Part 1: Vocabulary and Parameters of Roundness. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ASME B89.4.22-2004; Methods for Performance Evaluation of Articulated Arm Coordinate Measuring Machines. American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2004.

- ISO 10360-8:2013; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Systems (CMS)—Part 8: CMMs with Optical Distance Sensors. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Mendřický, R. Impact of applied anti-reflective material on accuracy of optical 3D digitisation. Mater. Sci. Forum 2018, 919, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDI/VDE 2634; Part 2. Optical 3D-Measuring Systems—Optical Systems Based on Area Scanning. Association of German Engineers (VDI/VDE): Düsseldorf, Germany, 2012.

- Debnath, B.; Pourfarash, Z.; Ghorpade, B.; Raman, S. Integrating Reverse Engineering for Digital Model Reconstruction and Remanufacturing of Mechanical Components: A Systematic Review. Metrology 2025, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Ji, L.; Li, Z. AI-Powered Next-Generation Technology for Semiconductor Optical Metrology: A Review. Micromachines 2025, 16, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archenti, A.; Gao, W.; Donmez, A.; Savio, E.; Irino, N. Integrated Metrology for Advanced Manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2024, 73, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masalskyi, V.; Dzedzickis, A.; Korobiichuk, I.; Bučinskas, V. Hybrid Mode Sensor Fusion for Accurate Robot Positioning. Sensors 2025, 25, 3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ul Haq, I.; Carni, D.L.; Lamonaca, F. Intelligent robotic positioning through AI-enhanced metrology. Acta IMEKO 2025, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, H.; Ahsan, M.; Raman, S. Metrology and Manufacturing-Integrated Digital Twin (MM-DT) for Advanced Manufacturing: Insights from CMM and FARO Arm Measurements. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.