Abstract

Early childhood is a critical period for physical and motor development with implications for long-term health. This systematic review examined the relationship between anthropometric characteristics and measures of physical fitness and motor skills in preschool-aged children (typically 2–6 years). The search strategy was applied in four databases (PubMed, ProQuest Central, Scopus, and Web of Science) to find articles published before 11 April 2024. The results consistently demonstrated significant associations between anthropometric variables (height, weight, body mass index [BMI], body composition) and physical performance measures. Notably, height and mass were often better predictors of fitness status than BMI alone. Indicators of undernutrition (stunting, wasting) were negatively associated with motor development, emphasizing the importance of adequate nutrition. While some studies reported impaired fitness and motor skills among overweight/obese preschoolers compared to normal-weight peers, others found no differences based on weight status. Relationships between physical activity levels, anthropometrics, and motor outcomes were complex and inconsistent across studies. This review highlights key findings regarding the influence of anthropometric factors on physical capabilities in early childhood. Early identification of children with impaired growth or excessive adiposity may inform tailored interventions to promote optimal motor development and prevent issues like obesity. Creating supportive environments for healthy growth and age-appropriate physical activity opportunities is crucial during this critical developmental window.

1. Introduction

Early childhood, defined as the period from birth to 8 years old, is a critical stage for physical, cognitive, and socioemotional development [1]. During this time, children experience rapid growth and acquire fundamental skills that lay the foundation for future health and well-being [2]. One key aspect of early childhood development is the attainment of age-appropriate physical fitness and motor skills, which are essential for engaging in physical activity, exploring the environment, and developing social competencies [3].

Physical fitness refers to a set of attributes related to the ability to perform physical activities, including cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular strength and endurance, flexibility, and body composition [4]. Motor skills, on the other hand, encompass the coordinated movement patterns that enable the performance of everyday tasks, such as locomotor skills (e.g., running, jumping), object control skills (e.g., throwing, catching), and stability skills (e.g., balancing) [5]. Both physical fitness and motor skill proficiency have been linked to numerous health benefits in children, including improved cardiovascular function, bone health, cognitive development, and psychosocial well-being [6,7].

The development of physical fitness and motor skills in early childhood is influenced by a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors [8]. Among these factors, anthropometric characteristics, such as height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and body composition, have been recognized as potential determinants of physical performance and motor development [9]. However, the nature and extent of these relationships remain unclear, with conflicting findings reported in the literature.

Several previous studies have explored related topics, such as the relationship between BMI and motor competence in preschoolers [10], the association between overweight/obesity and fundamental movement skills [11], or the influence of physical activity and sedentary behavior on physical fitness in this age group [12]. Rodrigues et al. [10] found a negative association between BMI and motor competence, suggesting that excess weight may hinder the development of motor skills. Similarly, Cattuzzo et al. [11] reported an inverse relationship between overweight/obesity and fundamental movement skills. Additionally, Poitras et al. [12] examined the relationship between physical activity, sedentary behavior, and physical fitness in preschoolers, emphasizing the importance of considering multiple anthropometric and behavioral factors in promoting healthy development. Finally, a longitudinal study conducted by Jaakkola et al. [13] found inconsistent evidence regarding the association between BMI and motor skills in children aged 3 to 12 years, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

While these studies provide valuable insights, they often focus on specific aspects or age groups. For instance, Rodrigues et al. [10] examined across childhood and adolescence or Cattuzzo et al. [11] focused on children aged 3–5 years. Age is an important factor that may influence the association between anthropometric characteristics and physical fitness and motor skills, as the rate and patterns of growth and development vary across different stages of early childhood [8]. In this sense, there is a need for a more comprehensive synthesis by examining the influence of various anthropometric characteristics, including height, weight, BMI, and body composition, on both physical fitness and motor skill development in the broader preschool population. By considering a wider range of anthropometric factors and their relationships with multiple domains of physical performance, this review seeks to elucidate the complex interplay between growth, body composition, and motor development during this critical yet dynamic period of rapid physical and neurodevelopmental changes [6,9].

Therefore, the present systematic review aims to address this gap by systematically summarizing the existing literature on the relationship between anthropometric characteristics (e.g., height, weight, BMI, body composition) and measures of physical fitness and motor skills in preschool-aged children (typically aged 2–6 years). The findings can inform tailored interventions and strategies to support optimal physical development, prevent obesity, and promote healthy lifestyles from an early age. Understanding these relationships is crucial for developing effective interventions and strategies to promote optimal physical development and prevent childhood obesity and the associated health risks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach to the Problem

The PRISMA guidelines [14] and the guidelines for performing systematic reviews in sport sciences [15] were used for conducting this systematic review.

2.2. Information Sources

The search strategies were designed with the following characteristics:

Date: 11 April 2024.

Databases: PubMed, ProQuest Central, Scopus, and Web of Science.

2.3. Search Strategy

The P (Population), I (intervention), C (comparison), and O (Outcomes) strategy was applied for designing the search strategy, as suggested by those guidelines used for conducting this systematic review:

(preschool OR kindergarten OR “early childhood”) AND (anthropometric OR morphology) AND (“physical fitness” OR “motor skill*”)

This search string was adapted for use across the PubMed, ProQuest Central, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. Controlled vocabulary searching was supplemented with keyword searching to enhance retrieval. The searches were run to capture studies with no other restrictions on date of publication, language, or study design.

Citation searches were also performed for key included studies. When full-text articles could not be obtained through institutional subscriptions or open access, attempts were made to contact the corresponding authors directly.

2.4. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The search was run out by two authors, who identified the most relevant information from each of the papers. Then, the information (title, authors, date, and database) was downloaded to an excel document, where duplicates were selected and removed. If any relevant study was found that was not through the search strategy, it was added as “added from external sources”. Each of the articles was analyzed for this eligibility following the inclusion–exclusion criteria detailed in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

2.5. Data Extraction

All the studies included in the excel document were checked to determine if each passed or not all the inclusion criteria. The process was independently conducted by the two authors. Any disagreements (5% of the total) on the final inclusion–exclusion status were resolved through discussion in both the screening and excluding phases and a final decision was agreed upon. In this discussion, both authors analyzed the article at the same time, looking for the exclusion criteria following all the criteria detailed in the Table 1, in the same order. This process was registered in the excel document.

2.6. Methodological Quality

To evaluate the risk-of-bias, each of the included articles was evaluated using an adapted version [16] from the original version developed by Law et al. [17]. This scale was composed by 16 items, detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methodological assessment of the included studies.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Selection of Studies

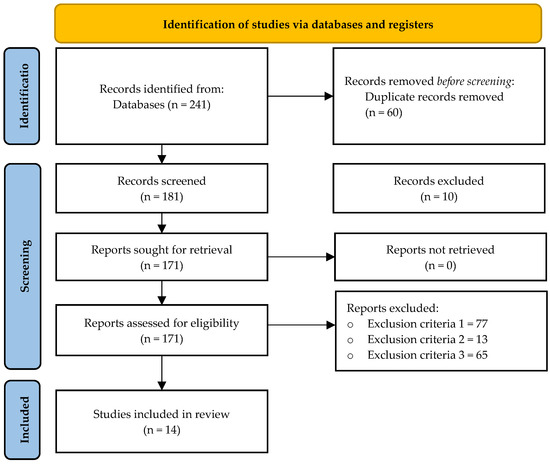

In total, 241 original articles were initially found, from which 60 were duplicated. The remaining 181 original articles were checked against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. After this analysis, 155 articles were eliminated because they did not meet one of the inclusion criteria detailed in the Table 1:

- -

- Inclusion criteria number one: 77

- -

- Inclusion criteria number two: 13

- -

- Inclusion criteria number one: 65

After this process, 14 articles meet all the inclusion criteria. All of them were evaluated for risk-of-bias, and then, included in Table 3, for extracting all the relevant information (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies included in this systematic review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the systematic review.

3.2. Quality Assessment

Table 2 presents a methodological assessment of multiple studies, evaluating their quality based on specific criteria. Most studies scored between 13 and 16 out of 16 points, indicating generally high methodological quality, although some variations in scores were observed, suggesting differences in methodological rigor among the studies.

3.3. Study Characteristics

Table 3 summarizes 14 studies that investigated the relationships between anthropometric characteristics, physical activity levels, motor skills, and physical fitness among preschool children. The key variables examined across these studies included height, weight, body mass index, skinfold thicknesses, circumferences, physical activity measures, and fitness test scores.

Several studies aimed to develop equations or critical values to predict physical fitness status from simple anthropometric measures like height and weight [18,19]. Others explored how anthropometric indicators of growth and nutritional status were associated with motor skill development [21,30] or risk of overweight/obesity [25,26,27].

The influence of weight status on performance in motor skills and fitness tests was examined [25,26,31], as was the relationship between physical activity, sedentary behavior, body composition, and fitness [23,24,29]. Some studies also described norms or percentiles for motor development scores relative to anthropometric measures [22,28].

4. Discussion

The results demonstrated significant associations between anthropometric variables such as height, weight, BMI, waist circumference, and measures of physical fitness and motor skills in preschool children. These findings are consistent with previous research that have reported inverse relationships between excess weight/obesity and motor competence [10,11] and physical fitness [12] in young children. However, the present review extends these findings by examining a broader range of anthropometric indicators and their relationships with multiple aspects of physical performance and motor development.

First, the results consistently demonstrate the importance of anthropometric measurements, particularly height, mass, and body composition, in influencing physical performance and motor development in preschool children. Several studies reported positive significant associations between these anthropometric variables and measures of physical fitness, such as muscular strength, endurance, and cardiorespiratory fitness [18,19,20,21,22]. In this sense, Kondrič et al. [18] found that height and mass were better predictors of fitness status than BMI or skinfold measurements, suggesting the potential value of these easily obtainable anthropometric indicators as screening tools in this age group. These findings are supported by studies suggesting BMI may not accurately capture musculoskeletal development importance for motor skills [32,33]. Additionally, studies found that stunting, underweight, and other indicators of malnutrition were negatively associated with motor development. [21,22,30]. These results align with previous evidence linking malnutrition to impaired growth and neurodevelopment [34,35]. This underscores the importance of adequate nutrition for supporting optimal physical and cognitive development and growth.

The influence of anthropometric characteristics on motor skills was also evident in the reviewed studies [21,22,23]. Sudfeld et al. [21] reported linear associations between height and motor development, while mass was linearly related to motor skills only in wasted children. Selvam et al. [22] derived age-specific norms for developmental milestones and found that stunted and underweight children exhibited significantly lower scores for communication and motor skills compared to their normal-weight counterparts. Similarly, Silventoinen et al. [19] observed associations between chest circumference and motor development, indicating the potential influence of prenatal and early postnatal factors on later motor abilities.

Another noteworthy finding from the reviewed studies was the relationship between anthropometric measures and weight status (e.g., overweight/obesity) in preschool children. Several studies reported impaired physical fitness and motor performance among overweight and obese preschoolers compared to their normal-weight counterparts [25,26,31]. For example, Agha-Alinejad et al. [25] reported that overweight and obese preschoolers demonstrated inferior performance in various fitness tests compared to their normal-weight peers. In contrast, De Toia et al. [26] found no significant differences in motor abilities between overweight/obese children and their normal/underweight counterparts, except for underweight children performing worse in flexibility tests aligning with inconsistent evidence reported in longitudinal studies [13]. The discrepancies between studies may be attributable to variations in study populations, measurement techniques, or the specific skills assessed [36,37]. These findings underscore the importance of early intervention and prevention strategies to promote healthy growth and development, as well as the potential implications for later health outcomes.

In addition, several studies examined the impact of specific conditions, such as motor delay or foot status, on anthropometric characteristics and motor performance. Hwang et al. [27] found that physical activity was a common predictor of higher BMI in children with and without motor delay. For instance, Kojić et al. [28] reported significant differences in motor status among preschoolers with varying foot statuses, suggesting that even subtle variations in physical characteristics can impact motor skill development. Collectively, these findings emphasize the importance of early identification and intervention for children with impaired growth, development, or specific conditions that may affect their physical fitness and motor skills.

Furthermore, the reviewed studies highlight the complex interplay between anthropometric characteristics, physical activity (PA), and fitness levels in preschool children. Serrano-Gallén et al. [29] reported associations between PA subcomponents (e.g., vigorous PA) and body composition and physical fitness, aligning with evidence linking higher activity levels to better fitness/motor skills [38,39]. On the other hand, some studies conducted by Bergqvist-Norén et al. [23] or Leppänen et al. [24] found no significant relationships between PA and weight status or motor skills. These discrepancies may be due to differences in activity measurement, age ranges, or other contextual factors [40,41]. Finally, it is important to note that the methodological quality of the included studies was generally high, with most studies scoring between 13 and 16 out of 16 points on the quality assessment scale. This indicates a relatively robust body of evidence, although some variations in methodological rigor were observed.

While the present systematic review provides valuable insights into the relationship between anthropometric characteristics and physical fitness and motor skills in preschool children, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. First, the review focused specifically on preschool-aged children, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other age groups. Second, the search strategy and inclusion criteria may have missed potentially relevant studies, introducing potential publication bias. Third, the heterogeneity in study designs, outcome measures, and analytical approaches across the included studies hindered direct comparisons and meta-analytical synthesis. Finally, the review did not assess the risk of bias or study quality using a comprehensive, validated tool, potentially introducing bias in the interpretation of the findings.

5. Conclusions

The present systematic review provides compelling evidence on the influence of anthropometric characteristics, such as height, mass, and body composition, on physical fitness and motor skill development in preschool-aged children. The findings underscore the importance of early identification and intervention for children with impaired growth or development, as well as the potential implications for obesity prevention and promoting healthy lifestyles. This review highlights the complex interplay between anthropometric measures, physical activity, and fitness levels, suggesting the need for a holistic approach in supporting optimal growth and development during this critical period.

The findings from this systematic review have several practical applications for healthcare professionals, educators, and policymakers working with preschool-aged children. Early screening and assessment of anthropometric characteristics, physical fitness, and motor skills can aid in identifying children at risk for developmental delays or health issues. Tailored intervention programs that integrate nutritional rehabilitation, physical activity promotion, and motor skill development can be designed to address the specific needs of these children. Additionally, this review emphasizes the importance of creating supportive environments and implementing policies that encourage healthy growth, active lifestyles, and age-appropriate physical activity opportunities for preschoolers. Collaboration among stakeholders, including healthcare providers, educators, and families, is crucial to ensure a comprehensive approach to promoting optimal development and well-being in this critical stage of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.-G. and C.D.G.-C.; methodology, M.R.-G. and A.P.R.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.A., A.P.R.-A. and C.D.G.-C.; writing—review and editing, M.R.-G. and L.P.A.; project administration, M.R.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood Development. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development; Shonkoff, J.P., Phillips, D.A., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-309-06988-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Britto, P.R.; Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y.; Ota, Y.; Petrovic, O.; Putnick, D.L. Child Development in Developing Countries: Introduction and Methods. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubans, D.R.; Morgan, P.J.; Cliff, D.P.; Barnett, L.M.; Okely, A.D. Fundamental Movement Skills in Children and Adolescents: Review of Associated Health Benefits. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goodway, J.D.; Ozmun, J.C.; Gallahue, D.L. Understanding Motor Development: Infants, Children, Adolescents, Adults; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-284-17494-6. [Google Scholar]

- Stodden, D.F.; Gao, Z.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J. Dynamic Relationships between Motor Skill Competence and Health-Related Fitness in Youth. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2014, 26, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J.; Sjöström, M. Physical Fitness in Childhood and Adolescence: A Powerful Marker of Health. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malina, R.M.; Bouchard, C.; Bar-Or, O. Growth, Maturation, and Physical Activity; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-88011-882-8. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, L.M.; Lai, S.K.; Veldman, S.L.C.; Hardy, L.L.; Cliff, D.P.; Morgan, P.J.; Zask, A.; Lubans, D.R.; Shultz, S.P.; Ridgers, N.D.; et al. Correlates of Gross Motor Competence in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1663–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.P.; Stodden, D.F.; Lopes, V.P. Developmental Pathways of Change in Fitness and Motor Competence Are Related to Overweight and Obesity Status at the End of Primary School. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattuzzo, M.T.; Dos Santos Henrique, R.; Ré, A.H.N.; de Oliveira, I.S.; Melo, B.M.; de Sousa Moura, M.; de Araújo, R.C.; Stodden, D. Motor Competence and Health Related Physical Fitness in Youth: A Systematic Review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E.; et al. Systematic Review of the Relationships between Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, T.; Yli-Piipari, S.; Huotari, P.; Watt, A.; Liukkonen, J. Fundamental Movement Skills and Physical Fitness as Predictors of Physical Activity: A 6-Year Follow-up Study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-González, M.; Pino-Ortega, J.; Clemente, F.M.; Los Arcos, A. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Reviews in Sports Science. Biol. Sport 2022, 39, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, H.; Clemente, F.M.; Araújo, D.; Davids, K.; McRobert, A.; Figueiredo, A. What Performance Analysts Need to Know About Research Trends in Association Football (2012–2016): A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 799–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, M.; Stewart, D.; Pollock, N.; Letts, L.; Bosch, J.; Westmorland, M. Critical Review Form—Quantitative Studies; Mac Master University: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kondri, M.; Trajkovski, B.; Strbad, M.; Foreti, N. Anthropometric Influence on Physical Fitness among Preschool Children: Gender-Specific Linear and Curvilinear Regression Models. Coll. Antropol. 2013, 37, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Silventoinen, K.; Pitkäniemi, J.; Latvala, A.; Kaprio, J.; Yokoyama, Y. Association Between Physical and Motor Development in Childhood: A Longitudinal Study of Japanese Twins. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2014, 17, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Gavilán, C.; Vitoria, R.V.; Gómez-Campos, R.; Cossio-Bolaños, A. Desempeño de la condición física de pre-escolares en función de la estatura y el área muscular del brazo. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Comunitaria 2017, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Sudfeld, C.R.; McCoy, D.C.; Fink, G.; Muhihi, A.; Bellinger, D.C.; Masanja, H.; Smith, E.R.; Danaei, G.; Ezzati, M.; Fawzi, W.W. Malnutrition and Its Determinants Are Associated with Suboptimal Cognitive, Communication, and Motor Development in Tanzanian Children. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2705–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, S.; Thomas, T.; Shetty, P.; Zhu, J.; Raman, V.; Khanna, D.; Mehra, R.; Kurpad, A.V.; Srinivasan, K. Norms for Developmental Milestones Using VABS-II and Association with Anthropometric Measures among Apparently Healthy Urban Indian Preschool Children. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1634–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergqvist-Norén, L.; Hagman, E.; Xiu, L.; Marcus, C.; Hagströmer, M. Physical Activity in Early Childhood: A Five-Year Longitudinal Analysis of Patterns and Correlates. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppänen, M.H.; Nyström, C.D.; Henriksson, P.; Pomeroy, J.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B.; Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Löf, M. Physical Activity Intensity, Sedentary Behavior, Body Composition and Physical Fitness in 4-Year-Old Children: Results from the Ministop Trial. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha-Alinejad, H.; Farzad, B.; Salari, M.; Kamjoo, S.; Harbaugh, B.; Peeri, M. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity among Iranian Preschoolers: Interrelationship with Physical Fitness. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2015, 20, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toia, D.; Klein, D.; Weber, S.; Wessely, N.; Koch, B.; Tokarski, W.; Dordel, S.; Strüder, H.; Graf, C. Relationship between Anthropometry and Motor Abilities at Pre-School Age. Obes. Facts 2009, 2, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A.-W.; Chen, C.-N.; Wu, I.-C.; Cheng, H.-Y.K.; Chen, C.-L. The Correlates of Body Mass Index and Risk Factors for Being Overweight Among Preschoolers With Motor Delay. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2014, 31, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojić, M.; Protić Gava, B.; Bajin, M.; Vasiljević, M.; Bašić, J.; Stojaković, D.; Ilić, M.P. The Relationship between Foot Status and Motor Status in Preschool Children: A Simple, Comparative Observational Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Gallén, G.; Arias-Palencia, N.M.; González-Víllora, S.; Gil-López, V.; Solera-Martínez, M. The Relationship between Physical Activity, Physical Fitness and Fatness in 3–6 Years Old Boys and Girls: A Cross-Sectional Study. Transl. Pediatr. 2022, 11, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worku, B.N.; Abessa, T.G.; Wondafrash, M.; Vanvuchelen, M.; Bruckers, L.; Kolsteren, P.; Granitzer, M. The Relationship of Undernutrition/Psychosocial Factors and Developmental Outcomes of Children in Extreme Poverty in Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Artero, E.G.; Concha, F.; Leyton, B.; Kain, J. Anthropometric Characteristics and Physical Fitness Level in Relation to Body Weight Status in Chilean Preschool Children. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanese, C.; Bortolami, O.; Bertucco, M.; Verlato, G.; Zancanaro, C. Anthropometry and Motor Fitness in Children Aged 6-12 Years. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2010, 5, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesztyüs, D.; Lampl, J.; Kesztyüs, T. The Weight Problem: Overview of the Most Common Concepts for Body Mass and Fat Distribution and Critical Consideration of Their Usefulness for Risk Assessment and Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; de Vijver, F.V.; Baar, A.V.; Mbonani, L.; Kalu, R.; Newton, C.; Holding, P. Socioeconomic Status, Anthropometric Status, and Psychomotor Development of Kenyan Children from Resource-Limited Settings: A Path-Analytic Study. Early Hum. Dev. 2008, 84, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkarnaen, Z. The Influence of Nutritional Status on Gross and Fine Motor Skills Development in Early Childhood. Asian Soc. Sci. 2019, 15, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, E.S.; James, R.S.; Birch, S.L.; Duncan, M. Prediction of Habitual Physical Activity Level and Weight Status from Fundamental Movement Skill Level. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, V.P.; Stodden, D.F.; Bianchi, M.M.; Maia, J.A.R.; Rodrigues, L.P. Correlation between BMI and Motor Coordination in Children. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, I.; Leblanc, A.G. Systematic Review of the Health Benefits of Physical Activity and Fitness in School-Aged Children and Youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmons, B.W.; Leblanc, A.G.; Carson, V.; Connor Gorber, S.; Dillman, C.; Janssen, I.; Kho, M.E.; Spence, J.C.; Stearns, J.A.; Tremblay, M.S. Systematic Review of Physical Activity and Health in the Early Years (Aged 0–4 Years). Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, J.J.; Jackson, D.M.; Montgomery, C.; Kelly, L.A.; Slater, C.; Grant, S.; Paton, J.Y. Total Energy Expenditure and Physical Activity in Young Scottish Children: Mixed Longitudinal Study. Lancet 2004, 363, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.; Schofield, G.M.; Schluter, P.J. Parent Influences on Preschoolers’ Objectively Assessed Physical Activity. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 13, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).