Abstract

Background: Body physique refers to body size, structure, and composition. PS is used to describe the profile of athletes in different sports. Aims: To determine body physique and body fat percentage in elite athletes using the Hattori chart and to identify the elite zone. Methods: Scoping review. The search was performed in PubMed, Google Scholar, Ovid Books, CAB eBooks, Clarivate InCites, MyiLibrary, Web of Science, Taylor & Francis Online, Core Collection, and Scopus. The search strategy was “body physique” OR “anthropometric” OR “body composition” AND “elite athlete” OR “athlete” OR “elite”. Results: Using indirect methods, elite athletes showed intermediate solid body physique (male) and lean intermediate body physique (female), and 13.6% ± 3.6% (male) and 22.3% ± 2.8 (female) body fat. Using doubly indirect methods, elite athletes showed lean intermediate body physique (male), and intermediate body physique (female), and a percentage of body fat of 13.7% ± 5.2% (male) and of 21.7% ± 4.3% (female) of body fat. Conclusions: Hattori’s chart facilitates the visualization of changes in body mass index, fat-free mass index, fat mass index, and percentage of body fat, helping personalize training, monitor composition changes, and guide nutrition programs to optimize performance and health.

1. Introduction

Body physique refers to body size, structure, and composition [1] and is used to describe the profile of athletes in different sports [2]. The Heath & Carter [3] somatotype is one of the most common methods for classifying somatotypes, which divides morphology into fat, musculoskeletal development, and relative linearity. Another method is the modified weight somatogram [4], which distinguishes muscular and non-muscular areas. The Phantom proportionality model [5] evaluates body proportions subjectively, without relying on absolute measurements. The Hattori chart [6] used the fat-free mass index (FFMI) and the fat mass index (FMI) to represent body physique, combining the percentage of body fat (BF%), a key component of body physique, and the body mass index (BMI). This last method is flexible and applicable to any population group. All of these methods can be applied to athletes of all sports [7], evaluating both muscle development [8] and body physique [9]. This method is flexible, applicable to any population group, and allows comparisons across sexes, disciplines, and performance levels. Furthermore, unlike the other methods mentioned above, which can mask differences in FMI and FFMI, the Hattori chart separates fat and lean contributions, providing a more precise morphological phenotype into nine categories. Given these advantages, the Hattori method offers clearer interpretability for sport scientists aiming to monitor body composition changes, classify physique types, and identify morphological zones associated with performance.

Morphological optimization is essential to maximize performance and monitor training success [10]. BF% is a crucial performance indicator for elite athletes in sports such as boxing, wrestling, and athletics. In aerobic disciplines such as marathon, low BF% and control of lean mass improves performance and helps to meet weight classes. Conversely, a high BF% may be beneficial in sports where body weight is relative, such as kayaking and canoeing [11]. Methods to measure BF% have evolved, from invasive procedures to more accessible indirect non-invasive techniques. However, despite the advances, differences between methods and the lack of standardization make it difficult to compare their precision [12].

Elite athletes are noted for their superior performance, consistent achievements, and years of experience [13]. Particularly, endurance athletes exhibit better adaptations in anaerobic threshold and VO2max [14]. Over time, athletes have shown increases in height and body mass, outpacing trends in the general population. This change has been associated with better performance and economic benefits. However, in some sports, athletes are required to maintain a specific range of body size, which has led to a stable morphology [15].

The evaluation of body physique in athletes is essential to classify and establish differences in terms of size, structure, and composition. This allows precise monitoring of performance, as well as comparisons between positions and other sports, helping to evaluate changes throughout macrocycles and facilitating the monitoring of morphological optimization. These results can be useful as a basis for future research, helping sports professionals to make appropriate decisions to improve the physique and performance of athletes. The evaluation of body physique in elite athletes has been used in fencing, artistic gymnastics, and combat sports to evaluate body composition, weight categories, styles of sport disciplines, and differences between sexes [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. The performance of elite athletes is closely linked to their body physique, especially BF%. Despite biological and adaptive differences in body physique among elite athletes, few studies have summarized BF% data. Research in this area has been scarce lately, focusing on data from athletes prior to the year 2000 [11,16,24,25,26]. However, despite the greater availability of body composition studies in international athletes, the body physique and variation in fat percentage in modern elite athletes of both sexes has been scarcely determined [16]. The novelty of this scoping review lies not in the use of Hattori’s chart for elite athletes, but in its comprehensive synthesis of the available information, identification of gaps in knowledge, and provision of a solid basis for future research on the body physique of elite athletes of both sexes. Therefore, this scoping review aimed to determine body physique and body fat percentage in elite athletes using the Hattori chart [6] and to identify the elite zone.

2. Methods

Design. This study was carried out based on the 2018 PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA—ScR) guideline [27]. As this study is a scoping review, it was not registered in PROSPERO.

Eligibility criteria. The studies included in this scoping review were published between 1995 and 2024. From this date, indirect methods such as air-displacement plethysmography (ADP) and dual x-ray densitometry (DXA) were more widely used in assessment of body composition [28]. During the analysis of these data, an attempt was made to represent the secular evolution in the morphology of the elite athlete. Articles in English, Portuguese, and Spanish languages were selected, and studies on elite male and female athletes aged 12 to 45 were reviewed. This broad age spectrum was chosen because the highest performance varies widely across sports, occurring mainly in adolescence for several specialized disciplines such as gymnastics, but extending into the late 20s, 30s, or even 40s in endurance and strength events [29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Articles that did not specify age (n = 3) or with open category for age (n = 1) were also included. The athletes were elite level, senior, Olympic, first division professionals, world record, world class, national level representatives, black belt, French Rating Scale of minimum 7a, non-professional sports with at least 10 years of experience, TOP ranking 10th at the national or international level, or high-level collegiate (world class, national representatives, or first division of the National Collegiate Athletics Association or first league of universities) [36].

The indirect methods used to assess body composition were hydrostatic weighing, air-displacement plethysmography (ADP) and dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The doubly indirect methods considered were bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) with a minimum of four electrodes, ultrasounds, and anthropometry with equations derived from two-, three-, and four-compartment models. In papers that showed measurements with several methods, priority was given to data derived from the following techniques in this order: ADP, DXA, hydrostatic weighing, BIA, ultrasound, and anthropometry. Studies that calculated BF% with at least three skinfolds, including those for calculating body density, were also considered. When a study did not report the BF%, this value was determined as: BF% = fat mass (kg) * 100/body mass (kg). Finally, body composition data in basal, initial, or pre-competition periods were considered.

Articles that featured male and female athletes at the amateur, recreational, Paralympic, preschool, and school level (under 12 years of age), second and third division athletes, those with less than 9.9 years of experience, extreme sports, and winter sports were excluded. Winter sports were excluded because their environmental and physiological demands such as cold exposure and thermoregulation, as well as equipment constraints create morphological patterns not comparable to those of non-winter sports. Including winter sports would have reduced conceptual and methodological consistency in the analysis.

However, an article on an amateur athlete with a national TOP ranking of 7 was included. Articles from elite athletes that did not specify sex, sport practiced, reported median, or reported grouped body composition data were not considered. Also, those who used formulas to obtain BF% with less than two skinfolds and who did not present fat mass data (kg) were not considered.

Information sources. The literature search was carried out in the electronic databases Medline via PubMed, Google Scholar, Books Ovid, CAB eBooks, Clarivate InCites, MyiLibrary, Web of Science, Taylor & Francis Online, Core Collection, and Scopus. All studies from 1995 to 2024 were filtered. The first author conducted the search strategy and then discussed them with all authors. To conduct a more comprehensive scoping review, within the selected articles, other potential references were identified through manual searching, allowing them to add relevant articles not considered in the initial search.

Search. The search strategy for each electronic database included the terms “physical status” OR “anthropometric” OR “body composition” AND “elite athlete” OR “athlete” OR “elite”. Additionally, article references from other reviews were manually retrieved.

Selection and sources of evidence. The first author reviewed the articles in duplicate, and the second author performed a review to ensure that they met all inclusion criteria. The authors then examined 233 data from elite athletes and sought information on each body composition team that met the eligibility criteria. In articles that used published equations to predict BF%, the original sources were consulted to verify the correct transcription of the equations used. Three meetings were held between May and August (2024) to review the database. The review resulted in deleting 111 articles. The data from the studies collected included the following: last name of the first author, year published, title of the article, sport, type of sport, athlete level, specialty or position, body composition method, skin caliper, equation used, software version or model of the equipment (ADP, DXA, and BIA,), age, sex, height (cm), body mass (kg), BF%, and/or fat mass (FM).

Data collection process. Following the deleted articles, a meeting was held with all authors to discuss data elements relevant to a scoping review. The data for the development of the Hattori chart [6] were body mass (kg), height (m), BMI (kg/m2), and BF%. To prepare the body physique tables, the Nutri Solver® software v.1 was used [36]. As quality control, the fat mass index (FMI) and fat-free mass index (FFMI) values were compared between the software and those calculated using Excel®. For the analysis of BF% and BMI, the D’Agostino Kurtosis descriptive statistical test was carried out to evaluate whether the data were normally distributed.

Data elements. To develop the results tables of this study, information on the country of origin or type of competition, athlete level, first author, year of publication, age, body mass, height, BMI, FMI, and FFMI were extracted from the publications, and the classification of body physique according to Hattori’s chart [7] was followed. To prepare the body physique graphs, FMI, FFMI, and athlete type data were used; moreover, the weighted average of BMI and BF% were obtained.

The elite zone was determined by integrating four variables: BMI, BF%, FMI, and FFMI. The FMI and FFMI were used to position athletes within the Hattori chart, as these indices independently represent fat and lean tissue adjusted for height and therefore define the compositional basis of the physique categories. BMI and BF% were analyzed alongside FMI and FFMI because they are consistently reported across studies using indirect and doubly indirect methods, enabling the synthesis of heterogeneous datasets. Moreover, BMI and BF% define the external phenotype in Hattori’s conceptual framework and allow the construction of interpretable boundaries that reflect the distribution of elite athletes. The mean and standard deviation of BMI and BF% were calculated across all included samples, and the ±1 SD and ±2 SD limits were used to outline the central morphology of elite athletes within the FMI–FFMI coordinate space. This combined approach provides both compositional precision and practical interpretability for sport scientists.

Synthesis of results. Studies were grouped by doubly indirect methods and indirect methods (male and female elite athletes), which were presented in tables separately by method and sex. To graph the results, the NCSS-8 program version 8.0.24, (Number Cruncher Statistical Systems, Kaysville, UT, USA) was used [37]. Body physique categories were derived from the mean and standard deviation (SD) of BMI and FFMI of adults aged 20.0 to 29.9 years [38] based on the third survey of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). This age was selected since the elite athletes in the current study showed a mean age of 24.0 ± 5.4 years. The equation to determine BMI was body mass (kg)/height (m)2. In accordance with Hattori’s methodology [39], fat mass and fat-free mass were adjusted by the subject’s height to obtain body composition indices: FMI = fat mass (kg)/height (m)2 and FFMI = fat-free mass (kg)/height (m)2. The FMI and FFMI cut-off points were calculated from the mean ±1 SD. The FMI was placed on the Y-axis and the FFMI on the X-axis. The resulting categories are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Categorization of the fat mass index (FMI) and free-fat mass index (FFMI) according to the body physique classification.

The combination of the coordinates of the X-axis (FFMI) and Y-axis (FMI) resulted in nine categories that determined different body physique morphotypes according to Hattori et al. [39] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nomenclature of the nine categories of body physique.

The weighted means of BF% and BMI were used only to plot the group’s central point in the Hattori chart. To draw the constant BF% lines, BF% was derived from the mathematical relationship between FMI and FFMI using Hattori’s equation BF% = FMI/(FMI + FFMI) (100) [39]. This equation was applied exclusively to generate the lines in the chart and not to estimate the BF% of individual athletes, whose values were extracted directly from the original studies. In the second chart, the elite zone for athletes was represented as ±1 SD for BMI and BF% (68.2% of athletes). The second elite zone, ±2 SD of BF% and BMI, encompassed 95.45% of the population. To prepare the descriptive tables of the body physique categories, the weighted means of BMI, BF%, FMI, and FFMI were also determined. The risk of bias in the studies, summary measures, and additional analyses of the included studies was not assessed [27].

3. Results

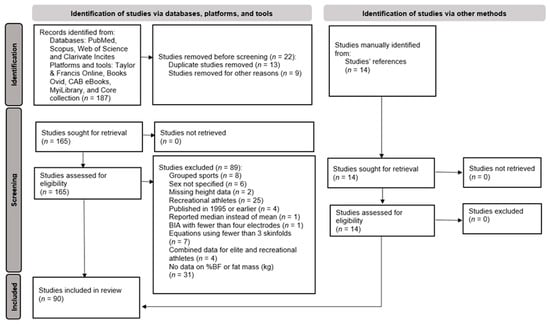

From the initial searched articles (n = 187), 14 articles were added through manual searching in review studies, resulting in 201 obtained articles. Duplicate studies (n = 13) and keywords (n = 9) were screened and deleted. Next, 165 articles were evaluated for eligibility; 89 studies were excluded and 90 were included for the final review. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow-chart for the inclusion, exclusion, and removal of studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow-chart of the process.

The main characteristics of the selected studies were presented with the following data: sport practiced, elite level, reference, age (years), height (meters), BMI (kg/m2), BF%, FMI (kg/m2), FFMI (kg/m2), and body physique. Likewise, the body composition results of elite athletes were shown with a total of 232 data points. Data from indirect methods in male athletes (n = 43) are shown in Table 3. The least used was hydrostatic weighing (n = 1), followed by ADP (n = 10) and DXA (n = 32). Data on elite female athletes (n = 18) are shown in Table 4. All data were obtained by DXA. See Supplemental Figures S1 and S2 for males and females, respectively.

Table 3.

Body composition in elite male athletes with indirect methods.

Table 4.

Body composition in elite female athletes with indirect methods.

Table 5 shows the body composition results of the elite male athletes (n = 115) that were measured with doubly indirect methods such as ultrasound (n = 3), BIA (n = 22), and anthropometry (n = 90). Table 6 shows articles from elite female athletes (n = 56). The methods reported were ultrasound (n = 3), BIA (n = 17), and anthropometry (n = 36). In total, combining indirect and doubly indirect methods, data from 232 athletes from 61 sports were considered. The risk of bias of the studies and additional analyses of the included studies were not assessed [27].

Table 5.

Body composition of elite male athletes with doubly indirect methods.

Table 6.

Body composition in elite female athletes with doubly indirect methods.

Body composition assessment using doubly indirect methods was applied in 65 papers, of which 47 used anthropometry. The equations most used in articles to calculate body composition in elite male athletes were Jackson and Pollock [63] (n = 9), followed by Durnin and Womersley [66] (n = 8) and Withers et al.’s unpublished data [10] (n = 7). In elite female athletes, the most used equations were Jackson et al. [124] (n = 7), Durnin and Womersley [66] (n = 5), Yuhasz [87] (n = 3), and Withers et al. [135] (n = 3).

The body physique of male elite athletes was lean intermediate with a BF% of 14.1 ± 5.4% (elite zone ±1 SD for BF%: 8.7% to 19.5%; BMI: 21.3 to 28.7 kg/m2). Similarly, female elite athletes exhibited lean intermediate physique with a BF% of 21.8 ± 4.1% (elite zone ±1 SD for BF%: 17.7% to 25.9%; BMI: 20.5 to 23.6 kg/m2).

A predominantly intermediate solid body physique (41.9%), followed by lean intermediate (23.3%) and lean solid (20.9%), adipose solid (9.3%), and intermediate (4.7%) physiques, was defined using indirect methods in 26.5 ± 5.2-year-old elite male athletes. The average BF% was 13.6% ± 3.6. Dominant body physiques of lean intermediate (38.9%), intermediate (33.3%), intermediate solid (22.2%), and lean solid (5.6%) were defined in 23.4 ± 5.6-year-old elite female athletes. The BF% in elite female athletes, measured by indirect methods, was 22.3% ± 2.8.

Using doubly indirect methods, the mean age of the elite male athletes was 23.8 ± 5.7 years. They showed a predominant body physique of lean intermediate (42.6%), followed by intermediate (27.0%), lean solid (14.8%), intermediate solid (12.2%), adipose solid (2.6%), and lean slender (0.9%). The average BF% was 13.7% ± 5.2. The elite female athletes assessed with the doubly indirect method had an average age of 23.3% ± 4.8 and an intermediate dominant body physique (44.6%), followed by lean intermediate (41.1%), lean solid (7.1%), and intermediate solid (7.1%). The mean BF% was 21.7% ± 4.3.

The elite zone of the athletes was defined as ±1 SD and ±2 SD for BF% and BMI. With indirect methods, the elite zone of BF% in male athletes at ±2 SD was from 6.4% to 20.8% and for BMI, from 19.8 to 33.8 kg/m2. In female athletes at +2 SD, the elite zone of BF% was 16.7% to 27.9% and for the BMI of 18.4 it was 25.2 kg/m2. With the doubly indirect methods, the elite zone of BF% in male athletes (±2 SD) was from 3.3% to 24.1% and for BMI, from 19.5 to 28.3 kg/m2.

In female athletes, the elite zone at ±2 SD of BF% was from 13.1% to 30.3% and for BMI, from 19.2 kg/m2 to 25.2 kg/m2. The elite zone at +2 SD encompassed five morphotypes in male and female athletes of indirect and doubly indirect methods: intermediate slender, intermediate, intermediate solid, lean solid, and lean intermediate. None of the elite athletes were in the lean intermediate quadrant, even though the elite zone encompassed this morphotype.

A description of the different categories of body physique for indirect and doubly indirect methods in elite athletes was made. Applying indirect methods, the predominant body physique in male athletes was intermediate solid (BMI 30.1 ± 3.4; BF% 15.9 ± 2.6; BMI 4.8 ± 1.2; FFMI 25.2 ± 2.5) (Table 7). In female elite athletes assessed with indirect methods, the dominant body physique was lean intermediate (BMI 20.2 ± 0.9; BF% 20.9 ± 1.7; 4.1 ± 0.6; FFMI 16.0 ± 0.7) (Table 7). With the doubly indirect methods, in elite male athletes, the predominant body physique was lean intermediate (BMI 22.2 ± 1.1; BF% 9.8 ± 2.1; BMI 2.1 ± 0.5; FFMI 20.0 ± 1.0) (Table 8). In female elite athletes assessed with doubly indirect methods, the dominant body physique was intermediate (BMI 22.9 ± 0.8; BF% 24.4 ± 2.4; IMG 5.5 ± 0.7; FFMI 17.2 ± 0.5) (Table 8). See Supplemental Figures S3 and S4 for males and females, respectively.

Table 7.

Description of body physique categories measured with indirect methods in elite athletes.

Table 8.

Description of body physique categories measured with doubly indirect methods in elite athletes.

4. Discussion

This study shows that male elite athletes measured using indirect methods predominantly had an intermediate solid body physique. In female elite athletes, the dominant body physique was lean intermediate. Using the doubly indirect methods, male elite athletes had a lean intermediate body physique, whereas female elite athletes had an intermediate body physique.

The variability in indirect and doubly indirect methods to estimate BF% varies between ethnic groups due to differences in subcutaneous fat distribution [140]. Accordingly, this review reported the methods separately. Moreover, the heterogeneity and accuracy of body composition methods may affect the assessment of body physique, mainly due to the limitations of each method, and then affect the classification of athletes in categories according to those described in Table 2.

In a study conducted in young adults, several methods were compared, including hydrostatic weighing, BIE (doubly indirect method), and DXA (indirect method); the last is considered the gold standard. It was observed that hydrostatic weighing (indirect method) showed the highest data in women, overestimating BF% by 2.9%, followed by BIE (doubly indirect method), which overestimates it by 2.7%. Anthropometric equations (doubly indirect method) can show significant variations in BF% ranging between 8.0% and 29.0% in women, and between 6.0% and 29.0% BF in men. Therefore, the choice of any equation must be made with caution, considering its precision and the characteristics of the population to be measured [141].

In the same discipline, in this case ballet, differences in BF% of 6.2% were observed between hydrostatic weighing and DXA (indirect methods) and BIE (doubly indirect method) [59]. Differences have also been found in elite gymnasts when comparing methods such as DXA with anthropometry (doubly indirect method) with a difference of 3.0% [57]. But even between DXA equipment with differences between pencil beam and fan beam, differences of 0.9% were found in Australian football players [46]. These discrepancies underline the importance of considering the methodological error that affects the comparison of results. As has been generally observed, DXA (indirect method) is used as a precise method for evaluating body composition in athletes [12,142,143,144].

Male elite athletes evaluated with indirect methods are mostly classified as intermediate solid, characterized by a high FFMI (25.2 ± 3.0 kg/m2), a moderate FMI (4.8 ± 1.2 kg/m2), and a mean BF% of 15.9 ± 2.6, classified as “Fair” according to the American College of Sports Medicine [145]. This body physique includes American football players, judokas, water polo players, and rugby players, who require strength and power, although they showed differences depending on the specific demands of each sport. In American football, positions could change according to strength and body mass, while speed and agility are more important in other positions such as linebackers and running backs [146]. In sports such as rugby and water polo, higher aerobic ability is required due to continuous physique activity, while judokas tended to have a low BF% and high muscle mass, which favors their performance [147]. Strength athletes are characterized by high body mass and bone mineral content, with a high BMI and a significant amount of fat mass [42,56,148,149,150,151]. The adipose solid category includes offensive and defensive linemen, who have a large size and high level of strength to absorb impacts [50,152,153] Sumo wrestlers are characterized by their high body mass, fat, and muscle [16,154,155]. Endurance sports, and those divided into weight categories tend to have the lowest BF% values, while in sports where body size is advantageous, there may be higher BF%.

In female elite athletes measured with indirect methods, the main body physique was lean intermediate, its main characteristics were a moderate FFMI (16.0 ± 0.7 kg/m2) and a low FMI (4.1 ± 0.6) with a mean BF% of 20.9% ± 1.7, within the “Fair” classification [145]. In this category are ballet dancers, soccer players, field runners, and gymnasts, who, despite their morphological differences, have a lower BMI that highlights their muscle tone. Ballet dancers have a higher BF% and lower muscle mass than gymnasts, but they stand out for their biomechanical and balanced skills. Dancers, field runners [156] and gymnasts [157] face health problems associated with low energy availability and bone mineral density. Female soccer players showed better biomechanical patterns and bone health in general [158,159,160].

Applying the doubly indirect methods, male elite athletes showed a predominantly lean intermediate physique, with a moderate FFMI (20.0 ± 1.0 kg/m2), a low FMI (2.1 ± 0.5 kg/m2), and a BF% of 9.8 ± 2.2, classified as “Excellent” [145]. This body physique, which emphasizes muscle definition and lean appearance, includes volleyball players, basketball players, boxers, taekwondo athletes, rowers, marathon runners, triathletes, sprinters, gymnasts, sprint swimmers, and other athletes who benefit from a low BF%. These characteristics improve agility, speed, endurance, and ability to change direction rapidly [121,161,162,163,164,165,166]. In the adipose solid body physique, athletes showed a mean FFMI of 28.1 ± 2.2 kg/m2, an FMI of 10.8 ± 0.3 kg/m2, and a BF% of 27.9 ± 2.1. This group includes heavy-weight powerlifters, where high fat-free mass is crucial to maximize squat, bench press, and deadlift performance [167,168,169]. However, high FMI can negatively affect relative strength [169].

In female elite athletes measured using doubly indirect methods, an intermediate body physique predominated, characterized by a moderate FFMI (17.2 ± 0.5 kg/m2) and FMI (5.5 ± 0.7 kg/m2) and a BF% of 24.4% ± 2.4 of poor classification [145]. Within this morphotype, open water swimmers benefit from higher BF%, which provides them with buoyancy and reduces water resistance; they tend to be smaller and lighter than competitive pool swimmers, which helps them in their endurance performance [170,171]. Female basketball and tennis players share several physical characteristics, including a lean body composition, high agility, significant aerobic and anaerobic capacity, and strong coordination and movement skills. These attributes are essential for the fast and dynamic movements required in both sports [172,173]. Female kayakers generally have larger body sizes, including higher body mass and height. This larger body size is associated with the specific demands of their sport [174]. There are also softball players, who tend to be taller and have larger biacromial and iliocristal diameters of the femur, as well as a greater femoral bicondylar diameter [175].

Comparing Hattori’s chart [39] with Heath and Carter’s [3] somatotype, the mesomorphic component, which reflects musculoskeletal robustness [176], is related in Hattori’s chart to the lean solid body physique. Ectomorphy corresponds to lean slender, and endomorphy to adipose intermediate. Studies in elite athletes [177] showed similarities between mesomorphy and the categories of Hattori’s chart. While somatotype focuses on a single component, Hattori’s chart classifies mesomorphic into four types, providing a more precise evaluation. However, few studies categorized body physique in elite or recreational athletes using the categories proposed by Hattori [6,39,178]. Among the studies published using this methodology, most of them focused on high or low FMI or FFMI [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. In summary, the Hattori chart is useful for classifying body physique and monitoring changes in body composition, offering comparative references. However, it is suggested that further studies be conducted across disciplines and among elite female athletes.

In this study, the elite zone was identified in male athletes using indirect methods with BF% between 6.4% and 20.8% and BMI from 19.8 kg/m2 to 33.8 kg/m2. In female elite athletes, the range was 16.7% to 27.9% for BF% and 18.4 kg/m2 to 25.2 kg/m2 for BMI. For the doubly indirect methods, the male elite zone was established with a BF% of 3.3% to 24.1% and a BMI of 19.5 kg/m2 to 28.3 kg/m2, while in women it was from 13.1% to 30.3% for BF% and from 19.2 kg/m2 to 25.2 kg/m2 for BMI. The morphotypes analyzed at ±2 SD included categories such as adipose solid, intermediate slender, intermediate, and intermediate solid, and lean slender, lean intermediate, and lean solid.

It was observed that SDs reflect variations in the athletes’ body physique, depending on the sport, and even the position or category within the same discipline. For example, gymnasts fall into the lean category, while sumo wrestlers and football linemen fall into the adipose solid category. These variations optimize sports performance according to the specific demands of the sport, such as judo, boxing, or rowing, where body composition directly influences performance [177].

To our knowledge, only one study differentiated the elite zone into categories for sumo wrestlers compared to the general population [16]. Identifying the elite zone could facilitate the monitoring of athletes in the different disciplines. The elite zone is a universal phenomenon experienced by almost all elite athletes, and it has been described as the pinnacle of achievement for an athlete and characterizes a state in which an athlete performs to the best of his or her ability [175,176]. The ±1 SD (±2 SD) zone would help identify differences between sports and optimize body composition to improve training cycles and sports performance or take advantage of biomechanical advantages, obtaining the highest performance in each sport discipline.

Identifying the elite zone (BMI ± 2 SD and BF% ± 2 SD) offers sport scientists a reference for monitoring athletes’ morphological changes throughout a training cycle. Athletes whose values fall outside this zone can be evaluated to determine whether the deviation reflects desired adaptations (e.g., increases in muscle mass) or potential issues such as excessive fat gain, low energy availability, or loss of lean mass. The elite zone can guide nutritional planning, training adjustments, and return-to-play decisions. In weight-category or aesthetic sports, the ±1 SD range may help identify when an athlete is approaching thresholds associated with increased injury risk or reduced energy availability, while the ±2 SD boundaries can serve as upper and lower limits beyond which performance may be compromised.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The main novelty of this study lies in the breadth of the review or in the comprehensive identification of the “elite zone” across a wider spectrum of sports and genders. Frisancho’s [38] cut-off points for ages 20 to 29.9 years were chosen due to the average age of the athletes evaluated. Although this reference is used as a growth curve because it is derived from the US NHANES surveys, it cannot adequately represent the body size and composition of athletes or all ethnicities. Elite athletes generally have lower body fat percentages compared to the general population, with significant variations by sport. However, this reference can be used as a basis to allow comparison of studies in which variables such as somatotype are used.

Furthermore, each method of estimating body composition has limitations that can influence the classification of athletes. Hydrostatic weighing (indirect method) appears to be unsuitable for athletes who focus on strength due to its demanding technique, and DXA (indirect method) has variations in manufacturers’ algorithms and differences between pencil and fan beams [174]. BIA (doubly indirect method) can be affected by factors such as limb length and hydration [179]. Ultrasound (doubly indirect method), although useful, requires considerable skill and is not standardized [174]. ADP and anthropometry (doubly indirect method) also have limitations in their accuracy. Anthropometry (doubly indirect method) is less precise than DXA (indirect method) and requires specific equations to avoid significant errors in athletes [174,180]. Although the aforementioned methods such as hydrostatic weighing, ADP, and DXA (both indirect methods) are considered reference methods for evaluating body composition in athletes, they are not widely accessible in most evaluation centers. Another limitation is that indirect methods (e.g., DXA) have higher precision than those that are doubly indirect (e.g., BIA).

Regarding anthropometric equations, the algorithm most used to predict BF% in elite athletes was previously proposed [63,124]. Although it does not specifically include athletes, its popularity is broad. Many of the equations reported by the studies are not generalizable to all athletes, since they are not a main part of the sample or are only specific to certain disciplines. Each equation is specific to the population studied, and the structure, body composition, and exercise habits of the population from which they are derived.

5. Conclusions

Body physique measured with indirect methods was intermediate solid in male elite athletes, and lean intermediate in elite female athletes. Body physique measured using doubly indirect methods was lean intermediate in male elite athletes, and intermediate in female elite athletes. Hattori’s chart facilitates the visualization of changes in body mass index, fat-free mass index, fat mass index and percentage of body fat, helping personalize training, monitor composition changes, and guide nutrition programs to optimize performance and health. Future research could apply Hattori’s method to differentiate athletes’ body composition by category, specialty, position, and training period.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jfmk11010013/s1, Figure S1: Body composition Fat-free mass index vs. fat mass index) in elite male athletes measured with indirect methods. Figure S2. Body composition Fat-free mass index vs. fat mass index) in elite female athletes measured with indirect methods. Figure S3. Body composition Fat-free mass index vs. fat mass index) in elite male athletes measured with doubly indirect methods. Figure S4. Body composition Fat-free mass index vs. fat mass index) in elite female athletes measured with doubly indirect methods.

Author Contributions

All authors provided literature searches, reviewed the literature, and prepared the main outline of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

S.G., C.B., E.A., and J.A.T. were funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the Fondo de Investigación para la Salud (CIBEROBN CB12/03/30038), which is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund, Red EXERNET-Red de Ejercicio Físico y Salud (RED2022-134800-T) Agencia Estatal de Investigación (Ministerio de Ciencias e Innovación, Spain), and IDISBA Grants (FOLIUM, PRIMUS, SYNERGIA, and LIBERI). The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

CIBEROBN is an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boileau, R.A.; Lohman, T.G. The Measurement of Human Physique and Its Effect on Physical Performance. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 1977, 8, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, M.; Christ, C. The role of body physique assessment in sport science. In Body Composition Techniques in Health and Disease, Society for the Study of Human Biology Symposium Series, Symposium 36; Davies, P., Cole, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 166–195. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, B.; Carter, L. A modified somatotype method. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1967, 27, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katch, F.I.; Behnke, A.R.; Katch, V.L. The Ponderal Somatogram: Evaluation of Body Size and Shape from Anthropometric Girths and Stature. Human 1987, 59, 439–458. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, W.D.; Wilson, N.C. A stratagem for proportional growth assessment. Acta Paediat. Belg. 1974, 28, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hattori, K. Body Composition and Lean Body Mass Index for Japanese College Students. J. Anthropol. Soc. Nippon. 1991, 99, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, T.; Michalíková, M.; Bednarčíková, L.; Živčák, J.; Kneppo, P. Somatotypes in sport. Acta Mech. Automat. 2014, 8, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuempfle, K.J.; Drury, D.G.; Petrie, D.F.; Katch, F.I. Ponderal Somatograms Assess Changes in Anthropometric Measurements Over an Academic Year in Division III Collegiate Football Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.E.L. Body Composition of Montreal Olympic Athletes. Med. Sport Sci. 1982, 16, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, K.; Olds, T. Anthropometrica; University of New South Wales Press: Sydney, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, S.J. Body composition of elite American athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 1983, 11, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, A.M.; Langan-Evans, C.; Hudson, J.F.; Brownlee, T.E.; Harper, L.D.; Naughton, R.J.; Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L. Come Back Skinfolds, All Is Forgiven: A Narrative Review of the Efficacy of Common Body Composition Methods in Applied Sports Practice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, C.; Moran, A.; Piggott, D. Defining elite athletes: Issues in the study of expert performance in sport psychology. Psychol. Sport Exer. 2015, 16, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.S.; Reiman, M.P.; Lehecka, B.J.; Naylor, A. What Performance Characteristics Determine Elite Versus Nonelite Athletes in the Same Sport? Sports Health 2013, 5, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, K.; Olds, T. Morphological Evolution of Athletes Over the 20th Century Causes and Consequences. Curr. Opin. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 763–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, K.; Kondo, M.; Abe, T.; Tanaka, S.; Fukunaga, T. Hierarchical differences in body composition of professional Sumo wrestlers. Ann. Human. Biol. 1999, 26, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterkowicz-Przybycień, K. Body composition and somatotype of the elite of Polish fencers. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 33, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sterkowicz-Przybycień, K. Technical diversification, body composition and somatotype of both heavy and light Polish ju-jitsukas of high level. Sci. Sports 2010, 25, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterkowicz-Przybycień, K. Body composition and somatotype of the top of Polish male karate contestants. Biol. Sports 2010, 27, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansba, R.; Sterkowicz, S.; Belkacem, R.; Sterkowicz-Przybycien, K.; Mahdad, D. Anthropometrical and physiological profiles of the Algerian Olympic judoists. Arch. Budo 2010, 6, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sterkowicz-Przybycień, K.; Almansba, R. Sexual dimorphism of anthropometrical measurements in judoists vs untrained subject. Sci. Sports 2011, 26, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterkowicz-Przybycień, K.; Sterkowicz, S.; Zarów, R.T. Somatotype, body composition and proportionality in polish top greco-roman wrestlers. J. Human Kinet. 2011, 28, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterkowicz-Przybycień, K.; Sterkowicz, S.; Biskup, L.; Zarów, R.; Kryst, Ł.; Ozimek, M. Somatotype, body composition, and physical fitness in artistic gymnasts depending on age and preferred event. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.A.; Rivera-Brown, A.M.; Frontera, W.R. Health Related Physical Fitness Characteristics of Elite Puerto Rican Athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1998, 12, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Malina, R.M. Body Composition in Athletes: Assessment and Estimated Fatness. Clin. Sports Med. 2007, 26, 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, D.A.; Dawson, J.A.; Matias, C.N.; Rocha, P.M.; Minderico, C.S.; Allison, D.B.; Sardinha, L.B.; Silva, A.M. Reference values for body composition and anthropometric measurements in athletes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Int. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Lohman, T.G.; Wang, Z.; Going, S.B. Composición Corporal; McGraw-Hill Interamericana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, H.; Toussaint, J.-F. Growth, Peaking, and Aging of Competitive Athletes. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1165223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.V.; Hopkins, W.G. Age of Peak Competitive Performance of Elite Athletes: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, M.; Güllich, A.; Macnamara, B.N.; Hambrick, D.Z. Predictors of Junior Versus Senior Elite Performance Are Opposite: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Participation Patterns. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1399–1416. Erratum in Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01625-4. [CrossRef]

- Boccia, G.; Brustio, P.R.; Moisè, P.; Franceschi, A.; La Torre, A.; Schena, F.; Rainoldi, A.; Cardinale, M. Elite National Athletes Reach Their Peak Performance Later than Non-Elite in Sprints and Throwing Events. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2019, 22, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, P.A.; Hopkins, W.G.; Paulsen, G.; Haugen, T.A. Peak Age and Performance Progression in World-Class Weightlifting and Powerlifting Athletes. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, P.T.; Knechtle, B. Performance in 100-km Ultra-Marathoners-At Which Age It Reaches Its Peak? J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1409–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, C.G.S.; Scharhag, J. Athlete: A working definition for medical and health sciences research. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-López, E. Nutri Solver. Fitness de Composición Corporal. 2018. Available online: https://nutrisolver.com/fitness-composicion-corporal.php (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Hintze, J. NCSS 8; Number Cruncher Statistical Systems: Kaysville, UT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frisancho, R. Anthropometric Standards, 2nd ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, K.; Tatsumi, N.; Tanaka, S. Assessment of Body Composition by Using a New Chart Method. Am. J. Human. Biol. 1997, 9, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittich, A.; Oliveri, M.B.; Rotemberg, E.; Mautalen, C. Body composition of professional football (soccer) players determined by dual X-ray absorptiometry. J. Clin. Densitom. 2001, 4, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Torine, J.C.; Silvestre, R.; French, D.N.; Ratamess, N.A.; Spiering, B.A.; Hatfield, D.L.; Vingren, J.L.; Volek, J.S.; Kraemer, A.; et al. Body size and composition of National Football League players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 485–489. [Google Scholar]

- Tsekouras, Y.E.; Kavouras, S.A.; Campagna, A.; Kotsis, Y.P.; Syntosi, S.S.; Papazoglou, K.; Sidossis, L.S. The anthropometrical and physiological characteristics of elite water polo players. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 95, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.; Fields, D.A.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Sardinha, L.B. Body composition and power changes in elite judo athletes. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.A.; Silva, A.M.; Matias, C.N.; Fields, D.A.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Sardinha, L.B. Accuracy of DXA in estimating body composition changes in elite athletes using a four-compartment model as the reference method. Nutr. Metabol. 2010, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghloum, K.; Hajji, S. Comparison of diet consumption, body composition and lipoprotein lipid values of Kuwaiti fencing players with international norms. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2011, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.; Fraser, W.D.; Sharma, A.; Eubank, M.; Drust, B.; Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L. Markers of bone health, renal function, liver function, anthropometry and perception of mood: A comparison between flat and national hunt jockeys. Int. J. Sports Med. 2012, 34, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liiv, H.; Wyon, M.; Jürimäe, T.; Purge, P.; Saar, M.; Mäestu, J.; Jürimäe, J. Anthropometry and somatotypes of competitive DanceSport participants: A comparison of three different styles. HOMO-J. Comp. Human. Biol. 2014, 65, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsborough, J.C.; Greenway, K.; Opar, D.; Livingstone, S.; Cordy, J.; Coutts, A.J. The accuracy and precision of DXA for assessing body composition in team sport athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemski, A.J.; Slater, G.J.; Broad, E.M. Body composition characteristics of elite Australian rugby union athletes according to playing position and ethnicity. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anding, R.; Oliver, J.M. Composición corporal del jugador de futbol americano: Importancia del monitoreo para el rendimiento y la salud. Sports Sci. Exch. 2015, 28, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, M.J.; Bansil, K.; Hind, K. Total, regional and unilateral body composition of professional English first-class cricket fast bowlers. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 34, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trexler, E.T.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Bryan Mann, J.; Ivey, P.A.; Hirsch, K.R.; Mock, M.G. Longitudinal body composition changes in NCAA division I college football players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, R.; Burke, L.M.; Cox, G.R.; Slater, G. Body composition of elite Olympic combat sport athletes. Eur. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 20, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, F.; Munguía-Izquierdo, D.; Suárez-Arrones, L. Validity of Field Methods to Estimate Fat-Free Mass Changes Throughout the Season in Elite Youth Soccer Players. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthumus, L.; Macgregor, C.; Winwood, P.; Darry, K.; Driller, M.; Gill, N. Physical and fitness characteristics of elite professional rugby union players. Sports 2020, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.; Caldwell, L.K.; Post, E.M.; Dupont, W.H.; Martini, E.R.; Ratamess, N.A.; Szivak, T.K.; Shurley, J.P.; Beeler, M.K.; Volek, J.S.; et al. Body Composition in Elite Strongman Competitors. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 3326–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutz, R.C.; Benardot, D.; Martin, D.E.; Cody, M.M. Relationship between energy deficits and body composition in elite female gymnasts and runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, G.; Brooks, A.; Withers, R.; Dollman, J.; Leaney, F.; Chatterton, B.; Australia, S.; Osmond, G. Body composition changes in female bodybuilders during preparation for competition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmerding, M.V.; McKinnon, M.M.; Mermier, C. Body composition in Dancers A Review. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2005, 9, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanese, C.; Piscitelli, F.; Lampis, C.; Zancanaro, C. Anthropometry and body composition of female handball players according to competitive level or the playing position. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randers, M.B.; Andersen, L.J.; Orntoft, C.; Bendiksen, M.; Johansen, L.; Horton, J.; Hansen, P.R.; Krustrup, P. Cardiovascular health profile of elite female football players compared to untrained controls before and after short-term football training. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blue, M.N.M.; Hirsch, K.R.; Pihoker, A.A.; Trexler, E.T.; Smith-Ryan, A.E. Normative fat-free mass index values for a diverse sample of collegiate female athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 1741–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.S.; Pollock, M.L. Generalized Equations for Predicting Body Density of Men. Br. J. Nutr. 1978, 40, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbo, L.A.; Papst, R.R.; Oliveira, F.; Ferreira, C.; Cuattrin, S.; Serpeloni, E. Perfil antropométrico da seleção brasileira de canoagem. Reviata Bras. Ciência Mov. 2002, 10, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jeličić, M.; Sekulic, D.; Marinovic, M. Anthropometric characteristics of high level European junior basketball players. Coll. Antropol. 2002, 26, 69–76. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10822429 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Durnin, J.V.; Womersley, J. Body Fat Assessed from Total Body Density and Its Estimation from Skinfold Thickness: Measurements on 481 Men and Women Aged from 16 to 72 Years. Br. J. Nutr. 1974, 32, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimber, N.E.; Ross, J.J.; Mason, S.L.; Speedy, D.B. Energy balance during an ironman triathlon in male and female triathletes. Int. J. Sport. Nutr. Exerc. Metabol. 2002, 12, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, E. Gender-related differences in elite gymnasts: The female athlete triad. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 2146–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechue, W.F.; Abe, T. The role of FFM accumulation and skeletal muscle architecture in powerlifting performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 86, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Kondo, M.; Kawakami, Y.; Fukunaga, T. Prediction Equations for Body Composition of Japanese Adults by B-Mode Ultrasound. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 1994, 6, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso da Silva, P.R.; de Souza, R.; De Rose, E. Body composition, somatotype and proporcionality of elite bodybuilders in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2003, 9, 408–412. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, J. Physiology of Swimming and Diving. In Exercise Physiology; Falls, H., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 415–447. [Google Scholar]

- Vanheest, J.L.; Mahoney, C.E.; Herr, L. Characteristics of elite open-water swimmers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Forsyth, H.L.; Sinning, W.E. The Anthropometric Estimation of Body Density and Lean Body Weight of Male Athletes. Med. Sci. Sports 1973, 5, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markou, K.B.; Mylonas, P.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Kontogiannis, A.; Leglise, M.; Vagenakis, A.G.; Georgopoulos, N.A. The influence of intensive physical exercise on bone acquisition in adolescent elite female and male artistic gymnasts. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2004, 89, 4383–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, G.J.; Rice, A.J.; Mujika, I.; Hahn, A.G.; Sharpe, K.; Jenkins, D.G. Physique traits of lightweight rowers and their relationship to competitive success. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.J.; Woodfield, L.; Al-Nakeeb, Y. Anthropometric and physiological characteristics of junior elite volleyball players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40, 649–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, B.; O’connor, H.; Pelly, F.; Caterson, I. Anthropometric Characteristics and Competition Dietary Intakes of Professional Rugby League Players. Int. Sport. Nutr. Exer Metabol. 2006, 16, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Muñoz, C.; Sanz, D.; Zabala, M. Anthropometric characteristics, body composition and somatotype of elite junior tennis players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, J.W.L.; Hume, P.A.; Pearson, S.N.; Mellow, P. Anthropometric dimensions of male powerlifters of varying body mass. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, E.; Nunes, A.V.; Moraes, J.M.; Del Vecchio, F.B. Physical fitness and anthropometrical profile of the Brazilian male judo team. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.A.A.; Rahaman, J.A.; Cable, N.T.; Reilly, T. Anthropometric profile of elite male handball players in Asia. Biol. Sports 2007, 24, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle, B.; Knechtle, P.; Andonie, J.L.; Kohler, G. Body composition, energy, and fluid turnover in a five-day multistage ultratriathlon: A case study. Res. Sports Med. 2009, 17, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailov, M.L.; Mladenov, L.V.; Schöffl, V.R. Anthropometric and Strength Characteristics of World-Class Boulderers. Med. Sport. 2009, 13, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortell-Tormo, J.M.; Pérez-Turpin, J.A.; Cejuela-Anta, R.; Chinchilla-Mira, J.J.; Marfell-Jones, M.J. Anthropometric profile of male amateur vs professional formula windsurfs competing at the 2007 European championship. J. Human Kinet. 2010, 23, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, E.; Huertas, J.; Sterkowicz, S.; Carratalá, V.; Gutiérrez-García, C.; Escobar-Molina, R. Anthropometrical profile of elite Spanish Judoka: Comparative analysis among ages. Arch. Budo 2011, 7, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Yuhasz, M. Physical Fitness Manual; University of Western Ontario: London, ON, Canada, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Diafas, V.; Dimakopoulou, E.; Diamanti, V.; Zelioti, D.; Kaloupsis, S. Anthropometric characteristics and somatotype of Greek male and female flatwater kayak athletes. Biomed. Human Kinet. 2011, 3, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnin, J.V.; Rahaman, M.M. The Assessment of the Amount of Fat in the Human Body from Measurements of Skinfold Thickness. Br. J. Nutr. 1967, 21, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbas, I.; Fatouros, I.G.; Douroudos, I.I.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Michailidis, Y.; Draganidis, D.; Jamurtas, A.Z.; Nikolaidis, M.G.; Parotsidis, C.; Theodorou, A.A.; et al. Physiological and performance adaptations of elite Greco-Roman wrestlers during a one-day tournament. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 1421–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianoli, D.; Knechtle, B.; Knechtle, P.; Barandun, U.; Rüst, C.A.; Rosemann, T. Comparison between recreational male ironman triathletes marathon runners. Percep. Mot. Ski. 2012, 115, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.D.; Altena, T.S.; Swan, P.D. Comparison of Anthropometry to DXA: A New Prediction Equation for Men. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, D.; Zaccagni, L.; Cogo, A.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Body composition and somatotype of experienced mountain climbers. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2012, 13, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernillo, G.; Schena, F.; Berardelli, C.; Rosa, G.; Galvani, C.; Maggioni, M.; Agnello, L.; La Torre, A. Anthropometric characteristics of top-class Kenyan marathon runners. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2013, 53, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Cech, P.; Maly, T.; Mala, L.; Zahalka, F. Body composition of elite youth pentathletes and its gender differences. Sport. Sci. 2013, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Velez, R.; Argothyd, R.; Meneses-Echavez, J.F.; Sanchez-Puccini, M.B.; Lopez-Alban, C.A.; Cohen, D.D. Anthropometric characteristics and physical performance of ColomBIEn elite male wrestlers. Asian J. Sports Med. 2014, 5, 23810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, M.J.; Findlay, M.; Gresty, K.; Cooke, C. Anthropometric variables and their relationship to performance and ability in male surfers. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2014, 14, S171–S177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, L.G.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Norte-Navarro, A.; Cejuela, R.; Cabañas, M.D.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M. Body composition and somatotype in university triathletes. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Rodriguez, A.; Collado, E.R.; Vicente-Salar, N. Body composition assessment of paddle and tennis adult male players. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Lambeth-Mansell, A.; Gillibrand, G.; Smith-Ryan, A.; Bannock, L. A nutrition and conditioning intervention for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Case study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2015, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdampilleta, A.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Valtueña, J.; Holway, F.; Cordova, A. Composición corporal y somatotipo de la mano de los jugadores de pelota vasca. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 2208–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavijo-Redondo, A.R.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R.; López-Miñarro, P.A.; Esparza-Ros, F. Características cineantropométricas de los jugadores de béisbol de élite. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katch, F.I.; McArdle, W. Prediction of Body Density from Simple Anthropometric Measurements in College-Age Men and Women. Hum. Biol. 1973, 45, 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Marinho, B.F.; Vidal Andreato, L.; Follmer, B.; Franchini, E. Comparison of body composition and physical fitness in elite and non-elite Brazilian jiu-jitsu athletes. Sci. Sports 2016, 31, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, T.G. Advances in Body Composition Assessment; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Casals, C.; Huertas, J.; Franchini, E.; Sterkowicz-Przybycien, K.; Gutiérrez-García, C.; Sterkowicz, S.; Escobar-Molina, R. Special Judo Fitness test level and anthropometric profile of elite spanish judo athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, D.; Zaccagni, L.; Babić, V.; Rakovac, M.; Mišigoj-Duraković, M.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Body composition and size in sprint athletes. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2017, 57, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, G.; Mujika, I. Anthropometric profiles of elite open-water swimmers. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryko, K.; Kopiczko, A.; Mikołajec, K.; Stasny, P.; Musalek, M. Anthropometric variables and somatotype of young and professional male basketball players. Sports 2018, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Muñoz, C.; Muros, J.J.; Zabala, M. World and olympic mountain bike champions’ anthropometry, body composition and somatotype. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2018, 58, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz Gamboa, J.; Espinoza-Navarro, O.; Brito-Hernández, L.; Gómez-Bruton, A.; Lizana, P.A. Body composition and somatotype of elite 10 kilometers race walking athletes. Interciencia 2018, 43, 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Palma-Lafourcade, P.; Cisterna, D.; Hernandez, J.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Alvarez, C.; Keogh, J.W. Body composition of male and female Chilean powerlifters of varying body mass. Motriz. Rev. Educ. Física 2019, 25, e101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corluka, M.; Bjelica, D.; Gardasevic, J.; Vasiljevic, I. Anthropometric Characteristics of Elite Soccer Players from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. J. Anthropol. Sport Phys. Educ. 2019, 3, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, R.; Sánchez, C.; Paulucio, D.; Da Silva, I.M.; Velasque, R.; Nogueira, F.S.; Ferrini, L.; Ribeiro, M.D.; Serrato, M.; Alvarenga, R.; et al. A multidimensional approach to assessing anthropometric and aerobic fitness profiles of elite brazilian endurance athletes and military personnel. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levernier, G.; Samozino, P.; Laffaye, G. Force-velocity-power profile in high-elite boulder, lead, and speed climber competitors. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2020, 15, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.M.; Gonzalez-Artetxe, A.; Aguinaco, J.A.; Arcos, A. Assessing the anthropometric profile of Spanish elite reserve soccer players by playing position over a decade. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; López-Domínguez, R.; López-Samanes, Á.; Gené, P.; González-Jurado, J.A.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J. Analysis of sport supplement consumption and body composition in spanish elite rowers. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopsaj, M.; Zuoziene, I.J.; Milić, R.; Cherepov, E.; Erlikh, V.; Masiulis, N.; Di Nino, A.; Vodičar, J. Body composition in international sprint swimmers: Are there any relations with performance? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Longo, G.; Grigoletto, D.; BIEnco, A.; Ferraris, C.; Guglielmetti, M.; Veneto, A.; Tagliabue, A.; Marcolin, G.; et al. Time-restricted eating effects on performance, immune function, and body composition in elite cyclists: A randomized controlled trial. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2020, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Jiménez, L.E.; Paola, Y.; Gutiérrez, A.; Adriana, I.; Rojas, S.; Jazmín Gálvez, A.; Janyn, P.; Buitrago, M. Relación entre marcadores dermatoglíficos y el perfil morfofuncional en futbolistas profesionales de Bogotá, ColomBIE. Retos 2021, 41, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Penichet-Tomas, A.; Pueo, B.; Selles-Perez, S.; Jimenez-Olmedo, J.M. Analysis of anthropometric and body composition profile in male and female traditional rowers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirali, M.; Faradjzadeh Mevaloo, S.; Bridge, C.; Hovanloo, F. Anthropometric Characteristics of Elite Male Taekwondo Players Based on Weight Categories. J. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2021, 4, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachoń, A.; Pietraszewska, J.; Burdukiewicz, A. Anthropometric profiles and body composition of male runners at different distances. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.S.; Pollock, M.L.; Ward, A. Generalized Equations for Predicting Body Density of Women. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1980, 12, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrino, E.; Maestá, N.; Reis, D.; Nardo Junior, N.; Morelli, M.Y.; Santarém, J.; Burini, R. Perfil antropométrico de culturistas brasileiras de elite. Rev. Paul. Educ. Fís 2002, 16, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, E.; Witzel, C.; Schwidergall, S.; Böhles, H.J. Peripubertal perturbations in elite gymnasts caused by sport specific training regimes and inadequate nutritional intake. Int. J. Sports Med. 2000, 21, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, F.; Yilmaz, I.; Erden, Z. Morphological characteristics and performance variables of women soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 480–485. [Google Scholar]

- White, S.; Philpot, A.; Green, A.; Bemben, M. Physiological Comparison Between Female University Ballet and Modern Dance Students. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2004, 8, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayios, I.A.; Bergeles, N.K.; Apostolidis, N.G.; Noutsos, K.S.; Koskolou, M.D.; Professor, A.; Also, K.A. Anthropometric, Body Composition and Somatotype Differences of Greek Elite Female Basketball, Volleyball and Handball Players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2006, 46, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Marrin, K.; Bampouras, T.M. Anthropometric and physiological changes in elite female water polo players during a training year. Serbian J. Sports Sci. Orig. 2008, 2, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sedano, S.; Vaeyens, R.; Philippaerts, R.; Redondo, J.C.; Cuadrado, G. The Anthropometric and anaerobic fitness profile of elite and non-elite female soccer players Motor coordination and sport talent in children. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2009, 49, 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Matillas, M.; Valadés, D.; Hernández-Hernández, E.; Olea-Serrano, F.; Sjöström, M.; Delgado-Fernández, M.; Ortega, F.B. Anthropometric, body composition and somatotype characteristics of elite female volleyball players from the highest Spanish league. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mala, L.; Maly, T.; Zahalka, F.; Bunc, V.; Kaplan, A.; Jebavy, R.; Tuma, M. Body composition of elite female players in five different sports games. J. Human Kin. 2015, 45, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haakonssen, E.C.; Barras, M.; Burke, L.M.; Jenkins, D.G.; Martin, D.T. Body composition of female road and track endurance cyclists: Normative values and typical changes. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, R.T.; Whittingham, N.O.; Norton, K.I.; La Forgia, J.; Ellis, M.W.; Crockett, A. Relative Body Fat and Anthropometric Prediction of Body Density of Female Athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1987, 56, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhlouvand, M.; Forbes, S.C. Aerobic capacities, anaerobic power, and anthropometric characteristics of elite female canoe polo players based on playing position. Sport. Sci. Health 2018, 14, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Kawamoto, K.; Dankel, S.J.; Bell, Z.W.; Spitz, R.W.; Wong, V.; Loenneke, J.P. Longitudinal associations between changes in body composition and changes in sprint performance in elite female sprinters. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2019, 20, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellissimo, M.P.; Licata, A.D.; Nucci, A.; Thompson, W.; Benardot, D. Relationships Between Estimated Hourly Energy Balance and Body Composition in Professional Cheerleaders. J. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2019, 1, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.A.; Do Nascimento, M.A.; Cavazzotto, T.G.; Reis Weber, V.M.; Tartaruga, M.P.; Queiroga, M.R. Relative age in female futsal athletes: Implications on anthropometric profile and starter status. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2020, 26, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deurenberg, P.; Deurenberg-Yap, M. Validity of body composition methods across ethnic population groups. Acta Diabetol. 2003, 40, s246–s249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golja, P.; Robič Pikel, T.; Zdešar Kotnik, K.; Fležar, M.; Selak, S.; Kapus, J.; Kotnik, P. Direct Comparison of (Anthropometric) Methods for the Assessment of Body Composition. Ann. Nutr. Metabol. 2020, 76, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, F.; Toselli, S.; Mazzilli, M.; Gobbo, L.A.; Coratella, G. Assessment of Body Composition in Athletes: A Narrative Review of Available Methods with Special Reference to Quantitative and Qualitative Bioimpedance Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, E.; Campa, F.; Buffa, R.; Stagi, S.; Matias, C.N.; Toselli, S.; Sardinha, L.B.; Silva, A.M. Phase angle and bioelectrical impedance vector analysis in the evaluation of body composition in athletes. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, K.; Slater, G.; Oldroyd, B.; Lees, M.; Thurlow, S.; Barlow, M.; Shepherd, J. Interpretation of Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry-Derived Body Composition Change in Athletes: A Review and Recommendations for Best Practice. J. Clin. Densitom. 2018, 21, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Sports Medicine. Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Tufano, J.; Brown, D.; Amonette, W.E.; Coleman, A.E.; Dupler, T.; Wenzel, T.; Spiering, B.A. Physical Determinants of Velocity and Agility in High School Football Players: Differences Between Position Groups. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, S36–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanala, V.; Gunen, E.; Igah, A. Anthropometric characteristics of selected combat athletic groups. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, i38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, D.; Asakura, M.; Ito, Y.; Yamada, S.; Yamada, Y. Physical Characteristics and Performance of Japanese Top-Level American Football Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 31, 2455–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Till, K.; Scantlebury, S.; Jones, B. Anthropometric and Physical Qualities of Elite Male Youth Rugby League Players. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, C.; Till, K.; Weakley, J.; Jones, B. Testing methods and physical qualities of male age grade rugby union players: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, D.; Kinoshita, S.; Sakaguchi, T. Annual Changes in the Physical Characteristics of Japanese Division I Collegiate American Football Players. Int. J. Strength Cond. 2023, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, T.K.; Millard-Stafford, M.; Rosskopf, L. Body Composition Profile of NFL Football Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1998, 12, 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, M.L.; Brown, B.S.; Gorman, D. Strength and Anthropometric Characteristics of Selected Offensive and Defensive University-Level Football Players. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1984, 59, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, H.; Kondo, M.; Ikegawa, S.; Fukunaga, T. Characteristics of Body Composition and Muscle Strength in College Sumo Wrestlers. Int. J. Sports Med. 1997, 18, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekley, M.D.; Abe, T.; Kondo, M.; Midorikawa, T.; Yamauchi, T. Comparison of normalized maximum aerobic capacity and body composition of sumo wrestlers to athletes in combat and other sports. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2006, 5, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, T.; West, B.; Sonneville, K.; Zernicke, R.; Clarke, P.; Harlow, S.; Karvonen-Gutierrez, C. Identifying latent classes of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) consequences in a sample of collegiate female cross-country runners. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 57, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maïmoun, L.; Coste, O.; Georgopoulos, N.A.; Roupas, N.D.; Mahadea, K.K.; Tsouka, A.; Mura, T.; Philibert, P.; Gaspari, L.; Mariano-Goulart, D.; et al. Despite a high prevalence of menstrual disorders, bone health is improved at a weight-bearing bone site in world-class female rhythmic gymnasts. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2013, 98, 4961–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbino, P.G.; Griffin, E.D.; Zurakowski, D. Comparison of standing balance between female collegiate dancers and soccer players. Gait Posture 2007, 26, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutedakis, Y.; Jamurtas, A. The Dancer as a Performing Athlete. Sports Med. 2004, 34, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahedi, H.; Taft, C.; Daum, J.; Dabash, S.; Mcculloch, P.; Lambert, B. Pelvic region bone density, soft tissue mass, and injury frequency in female professional ballet dancers and soccer athletes. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2021, 3, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, J.W.; Marnewick, M.C.; Maulder, P.S.; Nortje, J.P.; Hume, P.A.; Bradshaw, E.J. Are anthropometric, flexibility, muscular strength, and endurance variables related to clubhead velocity in low- and high-handicap golfers? J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, M.; Grgantov, Z.; Chamari, K.; Ardigò, L.P.; BIEnco, A.; Padulo, J. Anthropometric and physical characteristics allow differentiation of young female volleyball players according to playing position and level of expertise. Biol. Sport. 2017, 34, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, C.T.A.; Gomez-Campos, R.A.; Cossio-Bolaños, M.A.; Barbeta, V.J.D.O.; Arruda, M.; Guerra-Junior, G. Growth and body composition in Brazilian female rhythmic gymnastics athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1790–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkaouer, B.; Hammoudi-Nassib, S.; Amara, S.; Chaabène, H. Evaluating the physical and basic gymnastics skills assessment for talent identification in men’s artistic gymnastics proposed by the International Gymnastics Federation. Biol. Sport 2018, 35, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieske, O.; Chaabene, H.; Gäbler, M.; Herz, M.; Helm, N.; Markov, A.; Granacher, U. Seasonal Changes in Anthropometry, Body Composition, and Physical Fitness and the Relationships with Sporting Success in Young Sub-Elite Judo Athletes: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, H. During bodybuilding preparation, is a greater energy deficit related to a lower body fat percentage? Sci. Sports 2023, 38, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromaras, K.; Zaras, N.; Stasinaki, A.-N.; Mpampoulis, T.; Terzis, G. Lean Body Mass, Muscle Architecture and Powerlifting Performance during Preseason and in Competition. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferland, P.M.; Charron, J.; Brisebois-Boies, M.; Miron, F.S.J.; Comtois, A.S. Body Composition and Maximal Strength of Powerlifters: A Descriptive Quantitative and Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2023, 16, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latella, C.; Van den Hoek, D.; Teo, W.-P. Factors affecting powerlifting performance: An analysis of age- and weight-based determinants of relative strength. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 2018, 18, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, R.; Bonifazi, M.; Zamparo, P.; Piacentini, M. Characteristics and Challenges of Open-Water Swimming Performance: A Review. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, T.; Dascombe, B.; Bullock, N.; Coutts, A. Physiological characteristics of well-trained junior sprint kayak athletes. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, G.; Lidor, R. Physical Attributes, Physiological Characteristics, On-Court Performances and Nutritional Strategies of Female and Male Basketball Players. Sports Med. 2009, 39, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, J.; Stein, J.; Keogh, J.; Woods, C.; Milne, N. The Relationship Between Physical Fitness Qualities and Sport-Specific Technical Skills in Female, Team-Based Ball Players: A Systematic Review. Sports Med.-Open 2020, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackland, T.; Lohman, T.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Maughan, R.; Meyer, N.; Stewart, A.; Müller, W. Current Status of Body Composition Assessment in Sport. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, M.; Rathi, B. Kinanthropometric and performance characteristics of elite and non-elite female softball players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2013, 53, 628–634. [Google Scholar]

- Eston, R.; Reilly, T. Kinanthropometry and Exercise Physiology Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ackland, T.; Elliot, B.C.; Bloomfield, J. Applied Anatomy and Biomechanics in Sport, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lentin, G.; Cumming, S.; Piscione, J.; Pezery, P.; Bouchouicha, M.; Gadea, J.; Raymond, J.J.; Duché, P.; Gavarry, O. A Comparison of an Alternative Weight-Grading Model Against Chronological Age Group Model for the Grouping of Schoolboy Male Rugby Players. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 670720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyan, R. Body composition techniques. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2018, 148, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavedon, V.; Zancanaro, C.; Milanese, C. Body composition assessment in athletes with physical impairment who have been practicing a wheelchair sport regularly and for a prolonged period. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.