Abstract

Background: Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease worldwide. Motor and non-motor symptoms of PD cause functional disabilities. Aquatic-based therapeutic exercise (AT) is a potential approach that may improve the management of PD, given its hydrostatic and hydrodynamic properties. We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of AT compared to traditional land-based therapeutic exercise (LT) in patients with PD. Methods: Based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, we systematically reviewed studies indexed in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PEDro, CINAHL, and Cochrane. Registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024528310), this review involved original studies published from 2014 to December 2024, with a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design, in which the intervention group performed AT, and the control group performed LT. The outcomes evaluated were balance, gait, quality of life, strength, mental health, pain, flexibility, and sleep quality. Results: Of the 413 records identified, 135 duplicates were removed, and 265 did not meet the selection criteria. Thirteen RCTs comprising 511 patients (age range: 50–80 years) were eligible. Most studies reported beneficial effects of AT, with no serious adverse events. Compared to LT, AT led to significant improvements (p < 0.05) in quality of life, mental health, pain, flexibility, and sleep quality. No evidence was provided of the beneficial effects of AT compared to LT on balance, gait, and strength; however, significant improvements were observed in the AT group from baseline (p < 0.05). Conclusions: AT appears to be a safe and effective intervention for improving the quality of life, mental health, pain, flexibility, and sleep quality in PD patients. While balance, gait, and strength may also benefit, the evidence comparing AT to LT remains inconclusive due to variability in study protocols.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multisystem neurodegenerative disease characterized by deposits of α-synuclein in multiple regions of the nervous system [1,2]. The main regions are the substantia nigra, nucleus basalis of Meynert, and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve [2,3]. Patients with PD exhibit motor symptoms such as resting tremors, bradykinesia, stiffness, postural instability, and postural and gait alterations [1,2,4]. Non-motor symptoms, although often underestimated, can be equally disruptive motor symptoms, severely affecting patients’ quality of life (QoL) and autonomy [4]. These include fatigue, sleep disturbance, depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, dementia, hallucinations, urinary problems, and sexual dysfunction [2,3,4,5]. PD has become one of the main causes of disability worldwide, being the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s Disease [6]. The prevalence of PD in industrialized countries is estimated to be 0.3%, affecting up to 3% of the population over 80 years old [2]. PD is experiencing an alarming global increase, from 2.5 million cases in 1990 to 6.1 million in 2016, and these rates are expected to double by 2030 [1,3]. This high increase has led some researchers to characterize PD as a pandemic due to its wide geographical spread and exponential growth [7,8]. PD has a considerable impact on public health and the global economy. The United States spent USD 14.4 billion in 2010 on PD treatment, equivalent to USD 22,800 per patient [9]. For all these reasons, PD has become a major public health problem requiring an urgent solution.

Despite advances in the understanding of PD, there is currently no treatment able to stop or reverse the neurodegenerative process [1]. Conventional treatment is focused on symptom control, mainly through the administration of levodopa in combination with carbidopa [1,2]. Although this drug therapy has increased survival from 9 to 13 years [2], side effects such as fatigue, dyskinesias, anxiety, and somnolence are common and can complicate the management of the disease [4]. In order to reduce doses and modulate side effects, therapeutic exercise has been proposed as a possible adjuvant [10,11,12,13,14]. In particular, aquatic therapy (AT) has emerged as an alternative therapeutic option due to water properties like floatability, hydrostatic pressure, viscosity, and thermodynamics [15,16]. AT is considered a non-invasive, non-pharmacological treatment for chronic diseases [17,18]. AT has been shown to significantly improve balance, gait, strength, and QoL in patients with PD [19,20,21]. However, there is no consensus on the effectiveness of AT compared to land-based therapeutic exercise (LT). Some authors argue that AT provides greater benefits than LT [20,22,23], while others recognize its benefits but do not consider AT superior to LT [19,24]. The effectiveness of AT in PD has been the subject of several reviews in the scientific literature [20,21,23,24,25,26]. However, these reviews have highlighted substantial limitations, including small sample size [21,24], inclusion of uncontrolled clinical trials [25], and control group heterogeneity [20,23,26]. These methodological shortcomings underline the need for a rigorous systematic review that addresses the current evidence and provides a critical assessment of the effectiveness of AT compared to LT. In this context, the aim of the present study was to systematically review the available scientific evidence on the effectiveness of AT compared to LT in patients with PD, analyzing aspects such as QoL, balance, gait, and strength.

2. Materials and Methods

The present systematic review was conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [27] (Appendix A). The systematic review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024528310).

2.1. Search Strategy

The PICO question model was used according to the recommendations of Evidence-Based Medicine [28]: P (population): men and women diagnosed with PD classified within stages 1–3 on the Hoehn and Yahr Scale (H&Y), excluding patients with dementia, cognitive impairments, cardiac pathologies, or other associated conditions. I (intervention): aquatic-based therapeutic exercise. C (comparison): land-based therapy. O (outcomes): balance, gait, QoL, strength, pain, flexibility, mental health, and sleep quality. S (study design): randomized clinical trial. For article selection, a structured search was carried out using the electronic databases Medline (PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), CINAHL, and Cochrane between October and December 2024. The search strategy, detailed in Appendix B, contained a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free words such as “Parkinson Disease”, “Parkinson”, “Parinson’s Disease”, “Aquatic Therapy”, “Aquatic Exercise Therapy”, “Water Exercise Therapy”, and “Ai Chi Therapy” linked by the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”. Two authors independently performed the search for published studies, and a third reviewer participated in case of disagreement. In addition, the bibliographic references of all included articles and some of the excluded articles were reviewed, and ResearchGate was checked in order to identify relevant titles that might have been missed by the search strategy.

2.2. Selection Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were established for the studies selection: (1) Patients with PD (excluding studies whose population had other associated pathologies); (2) Intervention group (IG) treated with AT; (3) Control group (CG) treated with LT; (4) Randomized clinical trials that report primary or secondary outcomes on QoL, balance, gait, strength, flexibility, pain, sleep quality, or mental health; (5) Score equal to or greater than 6 on the Critical Appraisal Skills Program in Spanish (CASPe) questionnaire [29]; (6) Published in Spanish, English, Italian and Portuguese; (7) Published from 2014 onwards.

All studies that did not meet these criteria were excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction

The first author’s surname, year of publication, country of publication, sample size, gender, age, intervention of IG and CG, measurement scales used, and final results were extracted from all included studies. The data extraction process was independently carried out by two researchers using a spreadsheet (Microsoft Inc., Seattle, WA, USA). In case of disagreements, a third reviewer was involved in this process.

2.4. Assessment of Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias

The CASPe questionnaire [29] was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Additionally, the risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [30].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

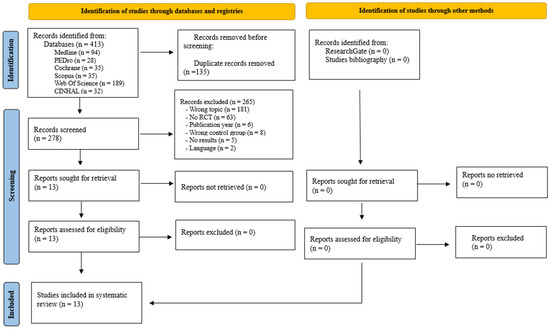

The literature search resulted in a total of 413 records from Medline (n = 94), PEDro (n = 28), Cochrane (n = 35), Scopus (n = 35), Web of Science (n = 189), and CINAHL (n = 32). No eligible studies were identified in ResearchGate or the reference list of relevant studies. After duplicate removal (n = 135), the titles and abstracts of the remaining 278 publications were analyzed. A total of 265 publications were eliminated for not being related to the topic of interest (n = 181), not being randomized clinical trials (n = 63), having been published prior to 2014 (n = 6), having a CG who did not perform LT (n = 8), being protocols without results (n = 5), and being in a language other than English, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese (n = 2). The remaining 13 trials were examined in full text and met the selection criteria for inclusion in the systematic review [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection for the literature review (PRISMA) [27].

3.2. Assessment of Methodological Quality

All included articles met the minimum requirements for methodological quality, scoring above 6 on the CASPe questionnaire [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Scores ranged from 8 [37,40] to 10 points [32,36,38,39]. Due to the type of intervention, none of the trials met the criterion of complete blinding. All therapists and participants knew the group to which they had been assigned [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. However, in nine studies, the assessors were blinded [31,33,34,35,37,38,40,41,43]. The effect sizes were large (d = 0.8) [31,32,37,39,40,43], medium (0.5 < d < 0.8) [36,38,42], and small (d < 0.5) [33,34,35,41] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of methodological quality assessment of included studies of Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASPe) [29].

3.3. Characteristics of Participants and Interventions

The total initial number of volunteers was 511, of which 464 completed this study, representing a dropout rate of 9.19% [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. A total of 64% of the participants were men, and 36% were women between the ages of 50 and 80 years [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. All studies included men and women in their samples [31,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], except Shahmohammadi et al. [36], who only included men. Participants had PD stages 1–3 on the H&Y scale [33,34,35,37,38,40,41,42], 2–3 H&Y [31,32,36], and 2.5–3 H&Y [39,43]. The investigation was conducted during ON [31,32,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] or OFF [33,34,35] periods of medication (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of studies included in the systematic review—participants, intervention characteristics, outcomes, and results.

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the interventions. Ten studies proposed the same protocol duration and frequency, duration, and intensity of the sessions for the IG and the CG, differing only in the type of exercise performed [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,42]. In the remaining three studies [31,40,43], the IG performed the same LT program as the CG in addition to AT. The duration of the protocols varied from 4 [31,43] to 12 weeks [37,41,42]. Each week, one [37], two [33,34,35,40,41,42], three [31,36,43], or five [32,38,39] sessions were performed. The duration of the session ranged from 30 [40] to 60 min [31,32,36,37,38,39,41,42,43]. All sessions were supervised by a qualified professional [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. The techniques used in the main part were Ai Chi [32,33,34,35], WATSU [40], Halliwick [37], gait work [31,36,41,42], balance [37,38,39,41,42,43], proprioception [31,43], coordination [41,43], strength work [37,39,41,42], aerobic work [37], and joint mobility [37,42,43].

Table 3.

Characteristics of intervention group and control group interventions.

3.4. Evaluation of the Results

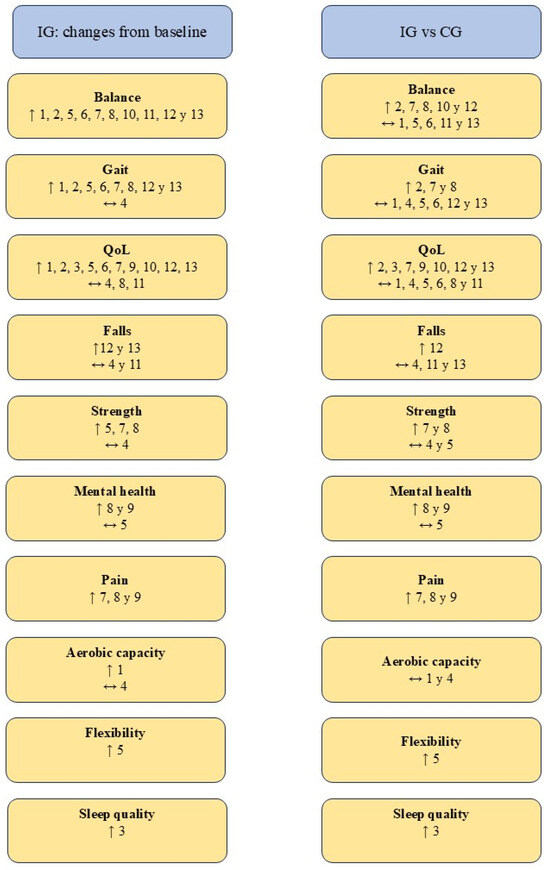

The parameters assessed and the results obtained after the interventions are presented in Table 2. In addition, the main findings are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of the results obtained. Abbreviations. ↑ Statistically significant improvements (p < 0.05); ↔ No statistically significant difference (p > 0.05); CG: control group; IG: intervention group; QoL: Quality of life. Authors. 1. Clerici et al. [31], 2. Kurt et al. [32], 3. Loureiro et al. [40], 4. Nogueira et al. [41], 5. Nowak [42], 6. Palamara et al. [43], 7. Pérez de la Cruz [35], 8. Pérez de la Cruz [34], 9. Pérez de la Cruz [33], 10. Shahmohammadi et al. [36], 11. Terrens et al. [37], 12. Volpe et al. [39], 13. Volpe et al. [38].

3.4.1. Balance

Changes in balance were assessed by 10 of the studies included in this systematic review [31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,42,43]. The 10 trials found statistically significant (p < 0.05) improvements in IG balance from baseline [31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,42,43]. However, only five of them reported statistically significant (p < 0.05) improvements over CG [32,34,35,36,39], while the remaining five did not find any difference (p > 0.05) [31,37,38,42,43].

3.4.2. Gait

Nine of the 13 included studies evaluated the effects of AT on gait [31,32,34,35,38,39,41,42,43]. All studies, with the exception of Nogueira et al. [41], reported statistically significant (p < 0.05) improvements in IG gait from baseline [31,32,34,35,38,39,42,43]. A greater disparity has been observed in relation to changes in IG compared to CG. Three studies reported significant improvements (p < 0.05) [32,34,35] in contrast to the remaining six studies, which showed no differences between groups (p > 0.05) [31,38,39,41,42,43].

3.4.3. Quality of Life

QoL related to PD symptomatology has been the most studied parameter, assessed by all 13 studies [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Ten of the studies recorded statistically significant (p < 0.05) increases in the IG compared to baseline [31,32,33,35,36,38,39,40,42,43]. However, only seven of them found better results in IG (p < 0.05) than in CG [32,33,35,36,38,39,40], while the remaining six did not show significant differences (p > 0.05) [31,34,37,41,42,43].

3.4.4. Strength

Lower limb strength was assessed by four trials using the Sit-to-stand test [34,35,41,42]. Three of them found statistically significant (p < 0.05) increases in IG over baseline [34,35,42], but only Pérez de la Cruz [34,35] reported statistically significant (p < 0.05) increases over CG. In a complementary way, Nowak [42] assessed the isometric strength of the knee and ankle musculature and the isokinetic strength of the knee. In none of these parameters, IG was superior to CG (p > 0.05) despite significant increases (p < 0.05) compared to baseline [42].

In addition, Nogueira et al. [41] and Nowak [42] assessed upper limb strength with manual dynamometry. The results of the two studies indicate that there are no significant differences (p > 0.05) between groups [41,42].

3.4.5. Other Parameters Evaluated

The effect of AT on mental health was evaluated by three studies [33,34,42]. Pérez de la Cruz [33,34] found in his two studies statistically significant (p < 0.05) improvements in IG compared to CG, while Nowak [42] did not find differences in IG compared to CG or baseline. Pain was studied by Pérez de la Cruz in his three investigations [33,34,35]. This author reported a statistically significant (p < 0.05) reduction in pain in IG relative to CG and baseline in all three studies [33,34,35]. Aerobic capacity was assessed by Clerici et al. [31] and Nogueira et al. [41], neither of whom found significant differences between groups (p > 0.05). Lower limb flexibility was studied by Nowak [42], who reported significant increases (p < 0.05) in the IG with respect to the CG and baseline. Finally, Loureiro et al. [40] evaluated the effect of TA on sleep quality, finding a significant increase (p < 0.05) in IG compared to CG and baseline.

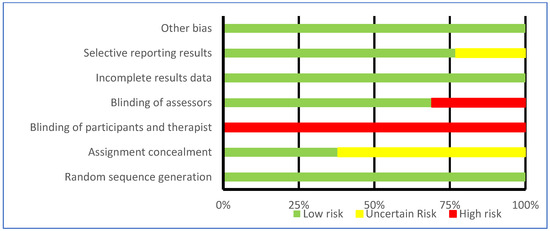

3.5. Bias Assessment

The assessment of bias is represented in Table 4 and Figure 3 according to Cochrane recommendations [30]. All studies showed low risk in random allocation of participants, incomplete outcomes data, and other biases [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. In contrast, all studies were at high risk of blinding participants and therapists [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Eight of the studies did not specify in the methodology how allocation concealment was performed [32,33,34,35,36,39,41,42]. The three studies by Pérez de la Cruz [33,34,35] had an unclear risk of selective reporting of results.

Table 4.

Results of risk of bias assessment of included studies—Cochrane tool [30].

Figure 3.

Results of risk of bias assessment of included studies—Cochrane tool [30].

4. Discussion

Overall, AT has been demonstrated to be an effective therapeutic approach in improving balance, gait, QoL, strength, pain, mental health, flexibility, and sleep quality. In addition, participants who practiced AT showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher improvements in QoL, mental health, flexibility, sleep quality, and pain compared to LT. However, there is no evidence of superior effects of AT on balance, gait, and strength. It is important to note that none of the 13 clinical trials reviewed reported that LT was superior to AT in any of the parameters assessed. Therefore, AT has been shown to be a superior or at least equal alternative to LT in the treatment of PD. No adverse effects of AT practice have been reported in PD patients, demonstrating that AT is a safe therapy [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. To ensure safety, all interventions were supervised by a qualified physiotherapist following Australian Physiotherapy Association guidelines [44].

4.1. Balance

Balance disturbances and falls are among the motor symptoms that most concern PD patients, second only to tremors [45]. As PD progresses, the processing of vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive signals responsible for maintaining balance becomes impaired [46]. In this context, all 10 clinical trials assessing balance reported statistically significant (p < 0.05) increases after AT [31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,42,43]. The aquatic environment may compensate for the altered proprioceptive signal processing by acting on peripheral sensory receptors [47]. Increased proprioceptive input may contribute to improved balance and body alignment [47]. In addition, AT, due to the floatability and viscosity of water, helps to organize the information and response of cortical regions, providing coordinated motor strategies and improving balance [21]. Finally, in-water training reduces the fear of falling and allows more challenging balance exercises to be performed for longer periods of time [48].

There is no consensus on the effectiveness of AT compared to LT on balance. Five trials have reported that AT was superior to LT [32,34,35,36,39], while the remaining five have found no significant difference between groups [31,37,38,42,43]. The only difference in the protocols used seems to be in water temperature. Authors who found superior AT kept the water at 30–32 °C [32,34,35,36,39], while authors who did not find a difference maintained it at 34–34.7 °C [31,37] or did not specify it [38,42,43]. Water temperature is an important factor to consider. It has been suggested that warm water may stimulate skin thermoreceptors and increase the activity of cortical sensory and motor areas, promoting sensory-motor integration [23]. It would, therefore, have a positive effect on balance. However, it should be noted that warm water also reduces muscle tone. A plausible hypothesis is that excessively hot water drastically reduces the tone of the musculature responsible for maintaining balance, impairing the correct performance of its function. A final point to highlight is that neither of the two studies that added AT to LT found improvements with respect to CG [31,43]. This suggests that practice AT does not provide additional benefits when LT is already being performed.

4.2. Gait

Following AT intervention, gait improved significantly (p < 0.05) in eight [31,32,34,35,38,39,42,43] of the nine studies that assessed it [31,32,34,35,38,39,41,42,43]. Gait improvement has been reported to be closely related to the balance benefits mentioned above [49]. Increasing postural stability allows patients to focus on walking correctly, which reduces the freezing of gait episodes [49]. In addition, walking underwater can positively influence motor learning, allowing patients to adapt to environmental perturbations [50]. AT achieves changes in spatiotemporal parameters and lower limb kinematics, generating clinically significant effects [50]. On the other hand, AT was only superior to LT in trials that used Ai Chi [32,34,35], indicating that it is the most effective methodology in improving gait. A previous systematic review reported that Ai Chi is effective in improving balance, pain, and functional mobility in healthy adults and patients with neurological diseases [48]. This is consistent with the results found in this review, especially in relation to gait. Many of the Ai Chi benefits are thought to come from conscious movement, giving it superior effects to LT and other types of AT [48].

Freezing of gait, despite being a very limiting phenomenon and a frequent cause of falls [51], has only been evaluated by one study [31]. Clerici et al. [31] reported that AT significantly (p < 0.05) reduces freezing of gait but did not find a difference with LT. In their protocol, Clerici et al. [31] added AT to LT, which might indicate that AT does not bring additional benefits when LT is already performed, as in the case of balance. Considering that the freezing of gait is caused by a loss of sensory information at the central level [52], AT could be expected to reduce the freezing of gait by increasing sensory information [47]. However, future studies are needed to clarify the effectiveness of AT alone on freezing gait.

4.3. Quality of Life

Participants’ QoL improved significantly (p < 0.05) after AT practice [31,32,33,35,36,38,39,40,42,43]. Seven studies have found that TA was superior (p < 0.05) to LT in improving QoL [32,33,35,36,38,39,40], while six studies did not report a difference (p > 0.05) [31,33,37,41,42,43]. Similarly, a recent systematic review by Gomes-Neto et al. [53] concluded that AT provides greater benefits than LT on QoL. AT could increase the QoL of PD patients for the following four reasons: (1) The improvements in balance and gait discussed in the previous points. (2) AT achieves mental health benefits superior to LT [33,34]. It has been reported that AT can increase self-efficacy, improve mood and self-esteem, relieve stress, and reduce anxiety and depression, helping to increase QoL [54,55,56]. (3) AT results in superior improvements in sleep quality than LT [40]. Given that sleep disorders negatively affect QoL and cognitive status, their correction could have a positive impact on QoL [57,58]. (4) AT reduces pain significantly more than LT [33,34,35]. Pain sensitivity is increased in PD due to abnormal temporal summation and impaired central pain processing, with lower pain thresholds [23]. However, pain is underestimated, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in PD [48]. Hot water immersion has anti-allodynic effects mediated by peripheral opioid, cannabinoid, and adenosine receptors in animal models [59]. This makes AT an effective option for pain management in PD by increasing QoL.

4.4. Strength and Flexibility

Strength was assessed by four studies [34,35,41,42]. Three of them found significant (p < 0.05) increases over baseline [34,35,42], but only two over CG [34,35]. Analyzing the trial protocols, the pattern identified above is repeated, with only Ai Chi achieving greater increases in strength than LT [34,35]. Ai Chi is not only effective in increasing strength in PD, but it has also been reported to provide benefits in strength in other diseases, such as multiple sclerosis [60]. Changes in strength after performing an AT protocol may be due to an increase in resistance to movement produced by water viscosity. This requires a greater involvement of the muscle strength components during exercise [61].

The impact of AT on flexibility was only evaluated by Nowak [42], who found significant (p < 0.05) increases over LT. This may be attributed to the fact that immersion in warm water increases the extensibility of collagen tissue and inhibits stretch reflex excitability, improving flexibility and relieving muscle stiffness [23].

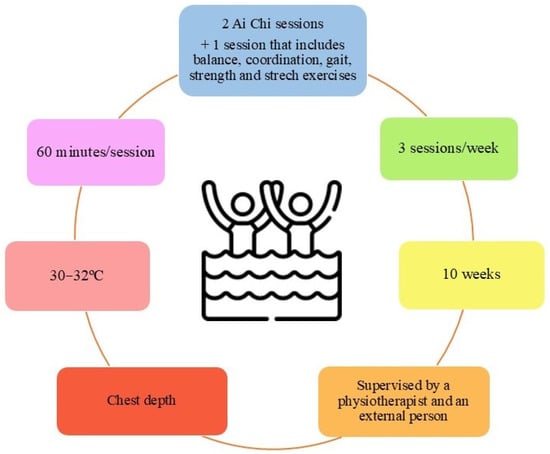

4.5. Practical Applications

In order to unify the wide variety of AT protocols designed for PD patients, an evidence-based AT protocol from the 13 trials included in this review is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Proposed protocol for aquatic therapy in patients with Parkinson’s Disease.

4.6. Reflections on the Role of Aquatic and Land-Based Physical Exercise in Parkinson’s Disease

Strong clinical evidence has shown a positive correlation between physical exercise and the amelioration of symptoms and side effects of Parkinson’s disease. In this context, the question arises as to which approach, aquatic or land-based, may be of most benefit to Parkinson’s sufferers. The underlying molecular mechanisms may shed some light on the results reported and guide sports therapies in this regard.

Irrespective of whether it is aquatic or land-based, physical exercise has shown cognitive improvements in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. Most cognitive benefits associated with exercise have been related to the production of growth factors at local and systemic levels within the hippocampus [62]. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is involved in the expansion of neural networks and cognitive–behavioral functions, plays a key role. Notably, a decrease in BNDF has been characterized in the pathological picture of Parkinson’s disease, and the increase in this neurotrophin is, in itself, a potential therapy for the condition [62]. Szuhany et al. [63] review in a meta-analysis of 14 studies how physical exercise leads to a significant increase in BNDF levels. At the brain level, despite the multitude of studies documenting this issue, it is not known how exercise stimulates BDNF production. However, the hemodynamic hypothesis suggests that the elevation of cerebral blood flow by exercise increases the activity of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which is responsible for cleaving proBNDF and producing mature BNDF [64].

Wrann et al. [65] demonstrated through their research that FNDC5, an exercise-induced muscle protein initially secreted as irisin, correlates with BNDF expression. FNDC5 is regulated by PGC-1α and has been shown to increase under conditions of hippocampal endurance exercise. The increased expression of FNDC5 in primary cortical neurons results in the upregulation of BNDF expression [65]. Water exercise leads to an increase in BNDF and, consequently, cognitive function [66,67]. Although an increase in BNDF is also found in floor exercises, we suggest that the properties of water may help to achieve higher levels of BNDF, not necessarily due to the type of exercise, but rather because it allows more effort to be exerted without feeling fatigued. This leads to increased performance, which could result in higher levels of BNDF.

An additional beneficial effect of exercise would be on AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity in skeletal muscle. This has a positive impact on several brain processes, including improved learning and memory abilities, increased neurogenesis, and regulation of genes associated with mitochondrial function in the hippocampus [68]. Aquatic exercise programs reduce chronic low-grade inflammation by decreasing pro-inflammatory markers like tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 10 (IL-10). This anti-inflammatory response may indirectly enhance pathways like AMPK [68]. The hydrostatic pressure of water may improve circulation and lymphatic drainage, enhancing the systemic anti-inflammatory response. Additionally, the cooling effect of water reduces exercise-induced inflammation, further promoting cytokine balance [69].

Physical activity has also been shown to increase circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). This hormone seems to contribute to the alleviation of Parkinson’s symptomatology by increasing hippocampal cell supersurvival capacity and being protective against brain injury [66]. It also has the ability to cross the BBB and induce BDNF synthesis in response to exercise [66]. Studies comparing aquatic and non-aquatic exercises found that IGF-1 levels increased significantly in both modalities. However, Aquatic exercise also stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which works synergistically with IGF-1 to enhance vascularization and cognitive function [66]. This dual effect may be less pronounced in non-aquatic settings due to differences in exercise dynamics. Also, the buoyancy of water reduces joint stress, allowing participants to engage in higher-intensity movements safely, which may enhance the release of growth factors like IGF-1 compared to LT.

It is, therefore, suggested that aquatic exercises may provide unique physiological benefits due to the properties of water (buoyancy, resistance, hydrostatic pressure) that favor and enhance the exercise-associated synthesis of key molecules in cognitive enhancement, neuroprotection, and reduction in inflammation.

4.7. Future Lines

During the course of this systematic review, a number of knowledge gaps have been identified and need to be addressed. Firstly, future research should clarify the effectiveness of AT alone on freezing of gait, a symptom that significantly affects PD patients’ mobility. Also, no study has evaluated the effectiveness of AT on transfers nor the effect of Ai Chi on falls. On the other hand, the effect of AT on strength should be further studied, as only four studies evaluated it, leaving a considerable gap in the understanding of how AT may influence this parameter. Similarly, flexibility and sleep quality were assessed by only one trial, indicating an urgent need for further research.

4.8. Limitations and Strengths

The authors of this review acknowledge some limitations. First, the number of studies that met the selection criteria was limited. However, PRISMA guidelines [27] were followed, six relevant databases were searched, and the grey literature was included. In addition, to ensure the methodological quality of the included studies, the CASPe scale [29] and the Cochrane bias assessment tool [30] were used. Due to the type of intervention, it was not possible for the therapists and participants to remain blinded. However, in nine trials [31,33,34,35,37,38,40,41,43], the assessors remained blinded, ensuring the absence of bias in this regard. On the other hand, there is great heterogeneity in the parameters assessed and the assessment tool used, which impedes the development of a meta-analysis. In addition, there is significant methodological heterogeneity among the studies, particularly in the AT protocols applied (e.g., type of exercises, session duration, frequency, water temperature), which limits the ability to compare results across interventions and draw generalizable conclusions. Finally, this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024528310) to guarantee its originality.

5. Conclusions

The efficacy of AT compared to LT for improving balance, gait, and strength in adult PDs appears to be limited. However, preliminary scientific evidence suggests that AT may be particularly superior to LT for improving quality of life, mental health, pain, flexibility, and sleep quality. Ai chi appears to be the most effective therapeutic exercise modality. It has been observed that the practice of supportive therapy does not provide additional benefits when LT is already being performed. No adverse events related to AT have been reported, supporting the fact that AT is a safe treatment strategy. In addition, AT may offer unique physiological advantages, including potential effects on cognitive enhancement, neuroprotection, and inflammation reduction, factors particularly relevant in neurodegenerative diseases. Finally, AT appears to offer benefits in certain outcomes compared to LT, although further studies are needed on biomarkers such as strength and gait, the impact of AT intensity on short- and long-term efficacy, and adherence strategies to aquatic therapy. Moreover, standardizing intervention protocols is essential to improve comparability across studies and to facilitate more robust conclusions in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S., M.F.-G. and D.F.-L.; data curation, G.S.; formal analysis, G.S. and D.F.-L.; funding acquisition, D.F.-L. and B.G.G.; investigation, G.S. and D.F.-L.; methodology, G.S., D.F.-L. and M.F.-G.; project administration, D.F.-L.; resources, D.F.-L.; software, D.F.-L.; supervision, M.F.-G. and D.F.-L.; validation, M.F.-G., Á.M., E.G.-A., B.G.G. and D.F.-L.; visualization, M.F.-G., Á.M., E.G.-A., B.G.G. and D.F.-L.; writing—original draft, G.S. and D.F.-L.; writing—review and editing, M.F.-G., Á.M., E.G.-A. and B.G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been financed by the Department of Education of the Junta de Castilla—León and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) by TCUE Plan 20242027, approved in the Order of 16 September 2024, grant no. 067/230003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Education of the Junta de Castilla–León for funding this study. Also, the authors want to thank the Neurobiology Research Group, Faculty of Medicine of the University of Valladolid, for their collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AT | Aquatic-based therapeutic exercise |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CASPe | Critical Appraisal Skills Program in Spanish |

| CG | Control group |

| FNDCS | Fibronectin type III domain-containing proteins |

| IG | Intervention group |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin 10 |

| LT | Land-based therapeutic exercise |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| PEDro | Physiotherapy Evidence Database |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| PGC-1α | Peroxime proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| Tpa | Tissue plasminogen activator |

Appendix A. Checklist PRISMA 2020 [27]

| Section and Topic | Item | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | 1–2 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for this review in the context of existing knowledge. | 2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 2 |

| Methods | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | 3 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists, and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 3 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers, and websites, including any filters and limits used. | 3 and 29 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of this review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 3 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 3 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | 3 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | 3 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess the risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study, whether they worked independently, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in this process. | 3 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | - |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | - |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling missing summary statistics or data conversions. | - | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | - | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s) and method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity and software package(s) used. | - | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | - | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | - | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | - |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | - |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in this review, ideally using a flow diagram. | 3–5 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | 3–5 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | 8 and 10–18 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | 6–8 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | 8–16 and 19 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarize the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | - |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was performed, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | - | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | - | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | - | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | - |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | - |

| Discussion | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 19–23 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in this review. | 23 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 23 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 21–23 | |

| Other information | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for this review, including register name and registration number, or state that this review was not registered. | 2 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | 2 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | 2 | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for this review and the role of the funders or sponsors in this review. | 24 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | 24 |

| Availability of data, code, and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in this review. | - |

Appendix B. Search Strategy Employed in Databases

| Database | Search Strategy |

| Medline/Pubmed | (Parkinson Disease (MeSH) OR Parkinson OR Parkinson’s Disease) AND (Aquatic Therapy (MeSH) OR Aquatic Exercise Therapy OR Water Exercise Therapy OR Ai Chi Therapy) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“parkinson disease” OR Parkinson OR “Parkinson’s Disease”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Aquatic Therapy” OR “Aquatic Exercise Therapy” OR “Water Exercise Therapy” OR “ai chi therapy”)) |

| Web of Science | Parkinson Disease (topic) AND Aquatic Therapy (Topic) |

| PEDro | Parkinson disease AND hydrotherapy, balneotherapy |

| CINAHL | (Parkinson disease OR Parkinson OR Parkinson’s Disease) AND (Aquatic therapy OR Aquatic Exercise Therapy OR Water Exercise Therapy OR ai chi therapy) |

| Cochrane | Parkinson Disease AND Aquatic Therapy |

References

- Cabreira, V.; Massano, J. Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical Review and Update. Acta Med. Port. 2019, 32, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, M.T. Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonism. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnecke, T.; Lummer, C.; Wilhelm, R.; Claus, I.; Lüttje, D. Parkinson’s disease. Inn. Med. 2023, 64, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, S.; Savitt, J. Parkinson’s Disease. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 103, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, S.; Mus, L.; Blandini, F. Parkinson’s Disease in Women and Men: What’s the Difference? J. Park. Dis. 2019, 9, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascherio, A.; Schwarzschild, M. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease: Risk factors and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, E.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.; Bloem, B. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L. Are we facing a noncommunicable disease pandemic? J. Epidemiol. Glob. Heal. 2017, 7, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, V.; Belbasis, L.; Tzoulaki, I.; Evangelou, E.; Ioannidis, J. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson’s disease: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvingelby, V.; Glud, A.; Sorensen, J.; Tai, Y.; Andersen, A.; Johnsen, E.; Moro, E.; Pavese, N. Interventions to improve gait in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and network meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 4068–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, P. Effects of Ten Different Exercise Intervention on Motor Function in Parkinson’s Disease Patients: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randommized Controlled Trials. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Li, F.; Wang, D.; Ba, X.; Liu, Z. Exercise sustains motor function in Parkinson’s Disease: Evidence from 109 randomized controlled trials on over 4600 patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1071803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, S.; Kumaresan, A.; Suganthirababu, P.; Vishnuram, S.; Srinivasan, V. A need to reconsider the rehabilitation protocol in patients with idiopatic Parkinson’s disease: Review analysis. Biomedicine 2022, 42, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hayek, M.; Lobo Jofili, J.; LeLaurin, J.; Gregory, M.; Abi Nehme, A.; McCall-Junkin, P.; KLK, A.; Okun, M.; Salloum, R. Type, Timing, Frequency, and Durability of Outcome of Physical Therapy for Parkinson Disease: A systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2324860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooventhan, A.; Nivethitha, L. Scientific evidence-based effects of hydrotherapy on varius systems of the body. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 6, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BE, B. Aquatic Therapy: Scientific foundations and clinical rehabilitation applications. PM R 2009, 1, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coraci, D.; Tognolo, L.; Maccarone, M.C.; Santilli, G.; Ronconi, G.; Masiero, S. Water-Based Rehabilitation in the Elderly: Data Science Approach to Support the Conduction of a Scoping Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Dai, S. Efficacy of aquatic exercise in chronic musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faíl, L.; Marinho, D.; Marques, E.; Costa, M.; Santos, C.; Marques, M.; Izquierdo, M.; Neiva, H. Benefits of Aquatic exercise in adults with and without chronic disease-A systematic review with meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2022, 32, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugusi, L.; Manca, A.; Bergamin, M.; Di Blasio, A.; Monticone, M.; Deriu, F.; Mercuro, G. Aquatic Exercise improves motor impairments in people with Parkinson’s disease, with similar or greater benefits than land-based exercise: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2019, 65, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methajarunon, P.; Eitivipart, C.; Diver, C.; Foongchomcheavy, A. systematic review of published studies on aquatic exercise for balance in patientes with multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and hemiplegia. Foongchomcheavy 2016, 35, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plecash, A.; Leavitt, B. Aquatherapy for neurodegenerative disorders. J. Huntingtons. Dis. 2014, 3, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Yuan, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wen, S. Effects of aquatic exercise on the improvement of lower-extremity motor function and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1066718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritz, T.; Snowdon, D.; Peiris, C. combining aquatic physiotherapy with usual care physiotherapy for people with neurological conditions: A systematic review. Physiother. Res. Int. 2020, 25, e1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrens, A.; Soh, S.; Morgan, P. The efficacy and feasibility of aquatic physiotherapy for people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 2847–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, M.; Laster, J.; Rogers, L.; Schultz, A.; Babl, R. The Effects of Aquatic Therapy on Gait, Balance, and Quality of Life in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. J. Aquat. Phys. Ther. 2019, 27, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Santos, C.M.; de Mattos Pimenta, C.A.; Nobre, M.R.C. The PICO Strategy for the Research Question Construction and Evidence Search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello López, J. Lectura Crítica de la Evidencia Clínica, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2021; ISBN 9788491138839. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerici, I.; Maestri, R.; Bonetti, F.; Ortelli, P.; Volpe, D.; Ferrazzoli, D.; Frazzitta, G. Land Plus Aquatic Therapy Versus Land-Based Rehabilitation Alone for the Treatment of Freezing of Gait in Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2019, 99, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, E.; Büyükturan, B.; Büyükturan, Ö.; Erdem, H.; Tuncay, F. Effects of Ai Chi on balance, quality of life, functional mobility, and motor impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-de la Cruz, S. Mental health in Parkinson’s disease after receiving aquatic therapy: A clinical trial. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2019, 119, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-de la Cruz, S. A bicentric controlled study on the effects of aquatic Ai Chi in Parkinson disease. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 36, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de la Cruz, S. Effectiveness of aquatic therapy for the control of pain and increased functionality in people with Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmohammadi, R.; Sharifi, G.; Melvin, J.; Sadeghi-Demned, E. A comparison between aquatic and land-based physical exercise on postural sway and quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled pilot study. Sport Sci. Health 2017, 13, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrens, A.; Soh, S.; Morgan, P. The safety and feasibility of a Halliwick style of aquatic physiotherapy for falls and balance dysfunction in people with Parkinson’s Disease: A single blind pilot trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, D.; Giantin, M.; Manuela, P.; Filippetto, C.; Pelosin, E.; Abbruzzese, G.; Anttonini, A. Water-based vs. non-water-based physiotherapy for rehabilitation of postural deformities in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled pilot study. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, D.; Giatin, M.; Giantin, M.; Maestri, R.; Frazzitta, G. Comparing the effects of hydrotherapy and land-based therapy on balance in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled pilot study. Clin. Rehabil. 2014, 28, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A.; Burkot, J.; Oliveira, J.; Barbosa, J. WATSU therapy for individuals with Parkinson’s disease to improve quality of sleep and quality of life: A randomized controlled study. Complement. Ther. Med. Pract. 2022, 46, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.; dos Santos, M.; Passos-Monteiro, E.; Wolffenbuttel, M.; Gimenes, R.; Zimmermann, M.; Janner, A.; Palmeiro, L.; Gomez, L.; Gomes, F.; et al. The effects of Brazilian dance, deep-water exercise and nordic walking, pre- and post-12 weeks, on functional-motor and non-motor symptoms in trained PwPD. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 118, 105285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, I. The Effect of Land-Based and Aquatic Exercise Interventions in the Management of Parkinson’s Disease Patients; University of Johannesburg: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Palamara, G.; Gotti, F.; Maestri, R.; Bera, R.; Gargantini, R.; Bossio, F.; Zivi, I.; Volpe, D.; Ferrazzoli, D.; Frazzitta, G.; et al. Land Plus Aquatic Therapy Versus Land-Based Rehabilitation Alone for the Treatment of Balance Dysfunction in Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Controlled Study With 6-Month Follow-Up. Phys. Ther. 2017, 98, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association, A.P. Australian Guidelines for Aquatic Physiotherapist Working in and/or Managing Hydrotherapy Pools. 2015. Available online: https://docslib.org/doc/11521132/australian-guidelines-for-aquatic-physiotherapists-working-in-and-or-managing-hydrotherapy-pools (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Port, R.; Rumsby, M.; Brown, G.; Harrison, I.; Amjad, A.; Bale, C. People with Parkinson’s Disease: What Symptoms Do They Most Want to Improve and How Does This Change with Disease Duration? J. Park. Dis. 2021, 11, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samoudi, G.; Jivegard, M.; Mulavara, A.; Bergquist, F. Effects of Stochastic Vestibular Galvanic Stimulation and LDOPA on Balance and Motor Symptoms in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Stimul. 2015, 8, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, M.; Liao, Y.; Xie, X.; Zhu, P.; Liu, Y.; Tan, C. Long-term efficacy of hydrotherapy on balance function in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1320240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, E.; Lambeck, J.; Gobert, D. ai Chi for Balance, Pain, Functional Mobility, and Quality of Life in Adults: A scoping Review. J. Aquat. Phys. Ther. 2021, 29, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutz, D.; Benninger, D. Physical Therapy for Freezing of Gait and Gait Impairments in Parkinson Disease: A systematic Review. PM R 2020, 12, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, D.; Pavan, D.; Morris, M.; Guiotto, A.; Lansek, R.; Fortuna, S.; Frazzitta, G.; Sawacha, Z. under water gait analysis in Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture 2017, 52, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, J.; Bloem, B.; Giladi, N.; Hallet, M.; Horak, F.; Nieuwboew, A. Freezing of gait: Moving forward on a mysterious clinical phenomenon. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, Y.; Hwang, S.; Kim, K.; Chung, W.; Youn, J.; Cho, J. Postural sensory correlates of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s Disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 25, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Neto, M.; Pontes, S.; Almeida, L.; Da Silva, C.; da Conceicao Sena, C.; Saquetto, M. Effects of water-based exercise on functioning and quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liposcki, D.; da Silva, I.; Silvano, G.; Zanella, K.; Schneider, R. Influence of a Pilates exercise program on the quality of life of sedentary elderly people: A randomized clinical trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2019, 23, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, L.; Tortelli, L.; Motta, J.; Menguer, L.; Marinano, S.; Tasca, G.; Silveira, G.; Pinho, R.; Silveira, P. Effects of aquatic exercise on mental health, functional autonomy and oxidative stress in depressed elderly individuals: A randomized clínical trial. Clinics 2019, 74, e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, L.; Menguer, L.; Doyenart, R.; Boeira, D.; Milhomens, Y.; Dieke, B.; Volpato, A.; Thirupathi, A.; Silveira, P. Effect of aquatic exercise on menthal health, functional autonomy, and oxidative damages in diabetes elderly individuals. Int. J. Enviorn. Health Res. 2022, 32, 2098–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremchuk, K. Sleep Disorders in Elderly. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 34, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohnhofen, H.; Popp, R.; Stieglitz, S.; Netzer, N.; Danker-Hopfe, H. Assessment of sleep and sleep disorders in geriatric patients. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 53, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.; Brito, R.; Stramosk, J.; Batisti, A.; Madeira, F.; Turnes, B.; Mazzardo-Martins, L.; Santos, A.; Piovezan, A. Peripheral neurobiologic mechanisms of antiallodynic effect of warm water immersion therapy on persistent inflamatory pain. J. Neurosci. Res. 2015, 93, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, D.; Guclu-Gunduz, A.; Yazici, G.; Lambeck, J.; Batur-Caglayan, H.; Irkec, C.; Nazliel, B. Effects of Ai-Chi on balance, functional movility, strength and fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. NeuroRehabilitation 2013, 33, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, A.; Reichert, T.; Conceiçao, M.; Delevatti, R.; Kanitz, A.; Kruel, L. Effects of Aquatic Exercise on Muscle Strength in Young and Elderly Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Ranzomized Trials. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 1468–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalzo, P.; Kümmer, A.; Bretas, T.L.; Cardoso, F.; Teixeira, A.L. Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor correlate with motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Bugatti, M.; Otto, M.W. A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 60, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefis, M.; Chaney, R.; Wirtz, J.; Méloux, A.; Quirié, A.; Leger, C.; Prigent-Tessier, A.; Garnier, P. Molecular mechanisms underlying physical exercise-induced brain BDNF overproduction. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1275924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrann, C.D.; White, J.P.; Salogiannnis, J.; Laznik-Bogoslavski, D.; Wu, J.; Ma, D.; Lin, J.D.; Greenberg, M.E.; Spiegelman, B.M. Exercise Induces Hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1α/FNDC5 Pathway. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.W.; Bressel, E.; Kim, D.Y. Effects of aquatic exercise on insulin-like growth factor-1, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and cognitive function in elderly women. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 132, 110842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, M.A.; van Wegen, E.E.H.; Newman, M.A.; Heyn, P.C. Exercise-induced increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor in human Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Neurodegener. 2018, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinha, C.; Ferreira, J.P.; Serrano, J.; Santos, H.; Oliveiros, B.; Silva, F.M.; Cascante-Rusenhack, M.; Teixeira, A.M. The impact of aquatic exercise programs on the systemic hematological and inflammatory markers of community dwelling elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 838580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, E.; Bote, M.E.; Giraldo, E.; García, J.J.; Ortega, E.; Bote, M.E.; Giraldo, E.; García, J.J. Aquatic exercise improves the monocyte pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production balance in fibromyalgia patients. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2012, 22, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).