Abstract

During the long nineteenth century, Western publics experienced the invention and proliferation of commercial games for children. Card games, board games, and other parlor games were no longer for adults only; these new offerings formalized some aspects of what it meant for a child to engage in play. Many games centered travel, becoming sites for children to simulate adult agency in movement through space. This paper examines the stories told by narrative card games and board games about travel, especially travel within and between urban centers. The games present the city as microcosm of the world. Child players are invited to construct multiple national and ethnic identities as they pretend to be city travelers. The games attempt to teach children, and their caregivers, how to travel. I argue that the structures and aims of the games evolve over time, keeping pace with new mores surrounding work and leisure travel. I also argue for connections between games and the “set moves” of narrative fiction and theatre.

Keywords:

childhood; spatial turn; play; travel; the city; storytelling; commerce; Henry James; Robert Louis Stevenson 1. Introduction

In Henry James’ novella What Maisie Knew (1897), Maisie becomes a pawn in her divorced parents’ games of domination. James references gaming to help his readers understand Maisie’s strange dance between power and powerlessness, chance and choice. After both of her parents are unhappily remarried to younger spouses—Sir Claude and Mrs. Beale (née Overmore), who are also playing romantic games with each other—Sir Claude begins to realize how profoundly Maisie’s formal education has been neglected. Sir Claude purchases multiple commercial games for Maisie to play with her similarly positioned caretaker, Mrs. Wix. The “ever so many games in boxes, with printed directions” (James [1897] 1923, p. 71), mystify Maisie and Mrs. Wix, but certainly plant ideas in their minds about adult game-playing that will come to fruition later. The effect of the games on Maisie is described thoroughly:

The passage reveals how readily available games were by the late nineteenth century, and how some caretakers had begun to see these games as a passive form of edutainment. The problem, however, comes when children (and others who are deemed outside of the circles of power) are being asked to play by rules, made by others, that they do not fully understand. Maisie and Mrs. Wix respond by doing what we must all do when confronting incomplete records and partial artifacts—try to glean what they can about the makers and purchasers and players, even if they cannot fully recover the conditions of play. They weren’t able to master the games, but poring over the games offered an opportunity to swap stories about their purchaser, Sir Claude. In the narrative proper, Maisie leaves her parlor to Channel hop with her fickle guardians, with emigration a constant threat or promise. The play that is meant to distract her also prepares her for the uncertain experience of being pulled along on paths adults laid out for her.The games were, as he said, to while away the evening hour; and the evening hour indeed often passed in futile attempts on Mrs. Wix’s part to master what ‘it said’ on the papers. When he asked the pair how they liked the games they always replied ‘Oh immensely!’ but they had earnest discussions as to whether they hadn’t better appeal to him frankly for aid to understand them. This was a course their delicacy shrank from; they couldn’t have told exactly why, but it was a part of their tenderness for him not to let him think they had trouble.(James [1897] 1923, pp. 71–72).

By the 1870s, comments like the following abounded in periodicals: “Of cardboard games, a great variety can be purchased at toyshops, some of them merely entertaining, but others conveying useful historical, geographical, and general knowledge” (Macauley 1875, p. 62). Such mass-produced games were fragile, with pieces that were easy to lose and instructions that were easy to misplace (Liman 2017, p. 23). Nevertheless, ardent collectors have left us enough artifacts from the past to make a valiant attempt at recovering—through literary references and through the objects themselves—what previous players came to know.

This project uses commercially available games for children from the nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century to investigate the relationship between simulated travel for children and the commercial and transatlantic interests and investments of adults, with a focus on products available across British and American markets. Between the years 1815 and 1915, writes Josephine McDonagh, 12 million British citizens emigrated permanently, many to the United States and others to Canada, South Africa, and Australasia (McDonagh 2021, pp. 3–4). These numbers do not include military deployments, the movements of colonial administrators, migrant work, or the burgeoning tourism industry; all together, it is appropriate to see the period as an unprecedented one for the circulation of bodies, objects, and ideas (McDonagh 2021). Travel almost always challenges ideas and beliefs, as “space” is “an agent in fashioning important aspects of human life such as selfhood, social relationships, and ideology” (Kozlovsky 2013). Scholars of “the ‘spatial’ turn in the social sciences and the humanities” taken by “Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, and Henri Lefebvre” among others (Kozlovsky 2013), have analyzed the interactions between space, power, and belief, across the disciplines. An analysis of racing games and narrative games that involve travel offers up the spatial turn in miniature.

In reusing existing maps for commercial games, “cartographers capitalized on public interest in vicarious travel, imperialism as an abstraction, and exotic locales”, merging the games in purpose and effect with “the travelogue” (Davies 2023, p. 25). Most American games “were imports or slightly varied copies of popular British games” (Guerra 2018, p. 39) until the middle of the nineteenth century, when the rise of Milton Bradley and the McLoughlin Brothers sent the flow of influence in the other direction. In examining these games, I ask, how were players encouraged to move through space? What educational aims seem embedded in these games? I will also discuss how these games often borrowed from literary tropes, and in some cases specific works of imaginative literature. Companies producing books for children went on to make and market many of these commercial games (Liman 2017, p. 14).

Interest in games among scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—including the relation between games and narrative—is likely to rise, due to recent works by Matthew Kaiser, Douglas Guerra, Megan Norcia, Siobhan Carroll, and others. The Victorian moment is the right starting point, as “the playing of formal games—as opposed to ‘just playing’—has throughout history been an essentially adult activity”, with board games for children “dating back not much further than the late eighteenth century” (Partlett 1999, p. x; See also Kaiser 2012, p. 104; Heath 2021, p. 195). In his monograph about play, Kaiser rejects an easy distinction between rules-based “games” and unstructured “play”. He suggests that Victorians could identify or generate rules to govern play, and could achieve spontaneity and improvisation while engaging formal games (Kaiser 2012, pp. 16–17). I draw from discussions of games in print culture, games held in the Brian Sutton-Smith Archive at the Strong Museum of Play, as well as collections that have been digitized in online databases or published alongside museum exhibits. In each section that follows, I move in chronological order through the artifacts so that readers can detect the developmental trajectory for in each kind of game—increasing interest in the global diversity of local spaces within the card-based Word Games, and increased compression, abstraction, and a sense of urgency in the racing games. Both tendencies relate to how corporate entities managed and packaged the experience of an increasingly vast, complex, and interlocking web as towns exploded into cities and the circulation of people and goods multiplied exponentially. Children role-played as adult travelers when they participated in these games, thus constructing and deconstructing different models for national identity in the global and interconnected world.

2. Card-Based Word Games

Most commercial games “operate as a form of collaborative storytelling, in which the players are engaged as coauthors” (Hoffman 2017, p. 22). Some games literalize this feeling, offering co-created stories as the outcome of game play. What we now know as Mad Libs (a franchise that began in the US during the mid-20th century (Stern 2024)), was for previous generations a parlor game called Consequences (Augarde 1984), or the “Game of Transformations” (Guerra 2018). In the informal game-play version of Consequences, as described in books such as Parlour Pasttimes for the Young (1857, see further Stern 2024), participants generate words that fall into certain categories, such as proper names, and the words are used to complete a humorous narrative (Augarde 1984, p. 194); as with Mad Libs, the full story is withheld until the words are generated. Here I will describe two card games with an international focus that formalize this kind of parlor game, providing filler words on decks of cards. Those games are strongly analogous to the experience of collaborative group storytelling, humorous wordplay, or amateur theatre (Stewart 1993, p. 7). The decks contain nouns naming people and objects, and they accompany a pamphlet with a story that contains several blank spaces. The goal is to use the nouns on the cards, at random in one game and by choice in the other, to complete the story’s sentences when prompted. The games I will discuss are examples of games in which “play was strategically nationalized” (Norcia 2004, p. 296).

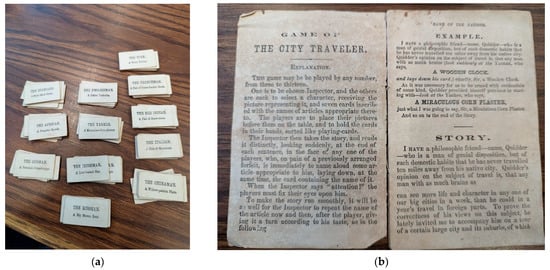

The Game of the City Traveler (McLoughlin Brothers 1880), also called Game of the Nations (Figure 1), which was produced in New York but set in London, tells the story of an Englishman named Quiddler, who has decided to travel more than 10 miles from his home for the first time in his life. London becomes the center of Quiddler’s encounters with individuals from all over the world. The game play dramatizes city life from a provincial perspective and encourages bold travel even within a small geographical space. Each player is assigned a specific national and/or ethnic identity, such as “Englishman”, “Red Indian”, “African”, and “Yankee”. A deck of cards, divided based on the nationality or race assigned to each player, facilitates the completion of Quiddler’s story.

Figure 1.

Game of the City Traveler (McLoughlin Brothers 1880). (a) Choice cards connecting different international characters with their goods. (b) First pages of the accompanying narrative booklet, explaining the rules of the game and presenting the first two paragraphs of the story. Images provided by the author.

How should we imagine the experience of the child who has been asked to play the “Turk” and chooses to fill his assigned sentence with an “Arab Steed” or “pair of Morocco slippers” when prodded to do so by the narrator? What is the experience of the narrator, who is deemed the “Inspector” in the game rules and encouraged to speak as an official would? Children process various racial and national hierarchies that could play out differently based on the choices made by both the Inspector (which nationality to call upon) and the players (which word to use to fill in the blank). One can imagine, for instance, an Inspector who does not call on all players with equal frequency. Children learn to laugh when the “Italian” introduces a “dish of macaroni”, a “ring-tailed monkey”, or “a jar of olives” into Quiddler’s day in London. In such games children learn to think about foreignness in relation to products of consumer culture (Norcia 2004). Writes Susan Stewart of the souvenir, “the function of belongings within the economy of the bourgeois subject is one of supplementarity, a supplementarity that in consumer culture replaces its generating subject as the interior milieu substitutes for, and takes the place of, an interior self” (Stewart 1993, p. xi). With this game, children enact this substitution in real time, surrounding themselves with the things that come to represent the assumed self, and reading the selfhood of others through their things. The inspector, like a star actor in a stage production, is given extra performance suggestions in the instructions, such as “to repeat the name of the article now and then, after the player, giving it a turn according to his taste” (McLoughlin Brothers 1880, p. 2), which is the Inspector’s opportunity to put his stamp on the imported goods. The children playing the foreigners lean into their performances as well, as with character actors aided by cue cards. The humor of the performance comes from the incongruity of the word inserted into the story, even though in this case the word inserted is the product of the Inspector’s choice of speaker, followed by the performer’s choice of representative word (Augarde 1984). In a regular game of Consequences, “one of the nice things … is that it is not a competitive game: everyone cooperates”, and the collaborative storytelling creates “a real game of chance” (Augarde 1984, p. 195).

In some games, in being “taught to perceive themselves as occupying a nexus of global exchange” (Norcia 2004, p. 300), children have their Englishness emphasized. However, in this game they are being taught to perceive themselves as actors outside of their home culture, with their performances providing the game’s comedy. In this game the “Englishman” and the “Yankee” join the cast of characters as equals, disrupting the narrative alongside the rest of the performers. Finally, children learn that the performance of specific racial or national identities can be assumed or discarded from one instance of game play to the next. This performance aspect is discussed explicitly in the story, when an African character in the tale complains about black faced impostors, saying, “spurious Africans, made up with burn’t cork, were going about the country representing themselves as the real thing” (McLoughlin Brothers 1880, pp. 11–12).

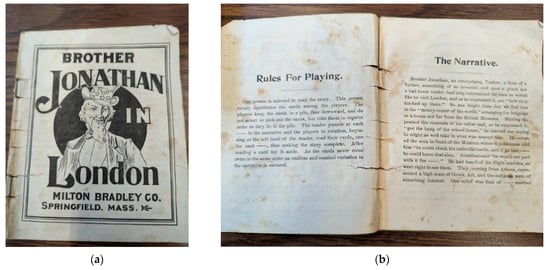

The narrative card game Brother Jonathan in London [Figure 2], was produced in the United States in 1910 by the prominent game maker Milton Bradley, which purchased McLoughlin Brothers ten years after releasing Brother Jonathan (Milton Bradley Company 1910). In the United States, McLoughlin Brothers, Parker Brothers, and Milton Bradley were the big three who “came to dominate the Anglophone archive” (Carroll 2021, p. 256). McLoughlin Brothers was founded as a book publisher by the Scottish immigrant John McLoughlin; the company became an internationally known American publisher of illustrated children’s books (Wasowicz et al. 2017). Milton Bradley “began as a maker and seller of lithographic prints” (Milton Bradley Company 1910, p. 9), and was important to the history of New England from its founding in 1860 to the present day (Shea 1973).

Figure 2.

Brother Jonathan in London (1910). (a) Cover of the Story Booklet, depicting Brother Jonathan, as conflated with Uncle Sam (b) First two pages of the Story Booklet, showing the rules and the start of the narrative. Photos by the author.

Brother Jonathan in London, with its simple rules and streamlined game play, is decidedly for children. Instead of cards being divided by national or ethnic “character”, words are read aloud in the order of the randomly shuffled pile. Per the game’s instructions, “As the cards never come twice in the same order an endless and comical variation in the narrative is to be secured” (Milton Bradley Company 1910, p. 2).

Children who play this game get a crash course in American/British relations and stereotypes. Brother Jonathan, the “enterprising Yankee”, appropriately resembles Uncle Sam on the cover of the game, as the character Brother Jonathan, popularized during the Revolutionary War, becomes Uncle Sam after the War of 1812 (Braun 2019; The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2024). In this game, Brother Jonathan is a Gulliver-like figure who allows the American game-player to laugh at himself, or the British player to laugh at the conventions of tourism in their heavily trafficked city. The original novelization of Brother Jonathan introduces him as an “incorrigible Yankee” (Neal 1825, p. 9) whose studies belie his rough exterior, and who can get the best of supposed experts in an argument (Neal 1825; The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2024). In Neal’s account, Brother Jonathan

By contrast, the 1910 version of Brother Jonathan lacks awareness of what he is seeing but retains the confidence of perfect knowledge; he becomes a counterexample for the game players, who absorb more about London through the comic tale than he does. The new Brother Jonathan’s lack of interest in London’s most famous historical landmarks, and in London’s history in general, transforms the whole city into all that it is in his mercenary American eyes, “the money center of the world” (Milton Bradley Company 1910, p. 2). For example, one sentence reads, “In St Paul’s, the third largest church in Christendom, he was disappointed in the size; it seemed no taller than _____” (Milton Bradley Company 1910, p. 9), where the blank could be filled, for example, by “an agitated old maid” or “a portrait of the prince of Wales”. The silly ending of the sentence is a fun way to drill the fact that St. Paul’s is the third largest church in Christendom. The child player thus sees more than Brother Jonathan’s eyes can manage, and is able to measure the edifice comparatively and properly.like most of his countrymen, had a way of doing whatever he did, in the shape of dispute, so thoroughly. He would always put his finger upon the place, give chapter and verse; prove it all with chalk and compasses; an old map and a tattered ‘geography;’ by bell, book, and candle, as it were;—nor did he give it up, notwithstanding all the cross looks, and pouting of the women people, until he had proved, perhaps, to the satisfaction of everybody but Mr. Deacon Brigadier Johnson, that he, the said brigadier, had been talking for twenty-five years about a matter, of which he knew nothing at all.(Neal 1825, p. 9)

The American character is most impressed with authority and mobility; he tells a fellow traveler catching the steamer at Liverpool that “the policemen and the omnibuses” (Milton Bradley Company 1910, p. 13) are the highlight of London for him. Earlier in the story, while riding on a double-decker bus, he proclaims, “Now spread yourself like _____ and fire all the information you have at me. I came from the U.S.A, I did, and don’t take a back seat for anyone, so let your tongue fly like ____ in a mill race” (Milton Bradley Company 1910, p. 4). Of course, Brother Jonathan is not in the proverbial driver’s seat; he must go where the double-decker bus takes him, and that route is the route of the paid tourist. Players of the game, getting to see London repeatedly through Brother Jonathan’s slightly shifting experience, also experience a feeling of partial control over the journey, limited to the shuffle of the deck at the start of the game, and, as with Game of the City Traveler (McLoughlin Brothers 1880), any tonal or dramatic improvisations introduced by the reader. Brother Jonathan travels by boat, steamer, and double-decker bus, but again he can’t get as close to the seats of power as he hoped: “Unfortunately he could not see the Queen; this made him as mad as ____, and what made him feel more vexed was because she being at home he could not see the Royal Gallery and that part of the Castle” (Milton Bradley Company 1910, p. 11). In a precursor of sorts to the hilarious National Park Yelp reviews published online in the early 2020s (Averill 2023), this story of Brother Jonathan offers a counterexample for children about how to travel respectfully through a foreign land. The game provides a baseline narrative that offers legitimate facts about London travel and London life, undercut by deliberately incongruous insertions by the limited power of the co-authors. In this second precursor to narrative roleplaying games, children are guided through space on a pre-determined track. However, as with the racing games I will discuss in the next section, after introducing one more card game that morphed in its Depression- and War-era versions, there is always the possibility that the child will find different ways to veer off the set course. Those opportunities for improvisation are embedded in the games themselves.

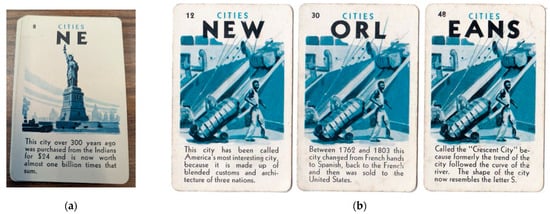

The Game of Cities (EE Fairchild Corporation [1932] 1945) requires players to collect “books” of three cards, each spelling out one third of the name of a famous American city [Figure 3]. The first edition featured 17 cities, and the second war-time edition featured 12 cities. In both versions, each book is united by one repeated illustration, and by facts that tie each American city to indigenous origins, industrial outputs, or internationalist flavor. For instance, the “Orl” card in the New Orleans book reads, “Between 1762 and 1803 this city changed from French hands to Spanish, back to the French and then was sold to the United States”. The “Le” of Seattle reads, “The bulk of all the raw silk shipped from the Orient is unloaded and reshipped to all parts of the United States from this city. The “Wy” of New York boasts, “In this city there are more Germans than in Bremen, more Italians than in Rome and more Irish than in Dublin”. To capture any one book is to passively absorb three ways in which that city is a microcosm not only of one community, but of a globally integrated space. The greatest number of points comes from collecting the largest city by population (New York in both versions), and the smallest from collecting the card for the smallest city featured in the game, Houston in 1932 and Washington in 1945. The one city that leads players to lose points (100 points) in the 1932 version only, is the imaginary city of Taboo, the only city on the board in which “the Indians played no part in the early history”, there is “no commerce and industry”, and there is no “good harbor, fertile lands, natural resources and navigable rivers”. The Taboo city encourages young players to seek the real and avoid the imaginary. Understanding any real city in the twentieth century involves understanding its origins in the native and its dependence on imports from abroad.

Figure 3.

Cities: A Card Game (a) card from the 1945 version of the game. The 1945 version, created during wartime, has fewer internationally facing facts on the playing cards than did the 1932 version, and does away with the fake city of Taboo. However, it maintains references to the Native American inhabitants of various cities. Photo by the author: (b) Full book of the 1932 version of Cities, with an internationalist focus and featuring a worker of color as the signature image. Image of the 1932 version courtesy of The World of Playing Cards: www.wopc.co.uk/usa/fairchild/cities (accessed on: 7 March 2024).

3. Racing Games

While story games imitated periodical stories, novels, and novellas, racing games brought illustrations from geography texts and storybooks to life. The narrative card games I described helped orient youth within individual cities. Racing games move them between cities. They are “ideally suited to expressing the bewilderment and powerlessness felt by nineteenth-century Britons in an increasingly internationalized world” (Carroll 2021, p. 244). Whether the landscape was recognizable from life or a product of the imagination, the gamification of the landscape turned the board into an opportunity for teaching. Allegorical games based on works such as Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (McLoughlin Brothers 1890b) are precursors to modern games such as The Game of Life, which figures the passage from birth to death (or the span from first employment to retirement, the economic version of birth to death), as a journey across a landscape marked by different obstacles. Such games seem to be a natural outgrowth of the Victorian era in particular, argues Matthew Kaiser, drawing on Gerhard Joseph and Herbert Tucker, as “the Victorians could view even death itself as a ‘prize,’ a moral reward for a race well run, a life well lived” (Kaiser 2012, p. 15). Other racing games had such familiar rules that game play could transcend language barriers. For instance, prior to the eighteenth century the popular game of Goose could be a “mediator of social relations between people from disparate places (Carroll 2021, p. 245). When the landscape mapped real cities and routes instead of allegorical routes as in Pilgrim’s Progress-style games, or abstract stylized squares as in the game of Goose, players found ways to travel otherwise unfathomable distances with a single roll of the dice or spin of the teetotum, gaining new feelings about the earth as traversable and conquerable, with some skill and not a small amount of luck.

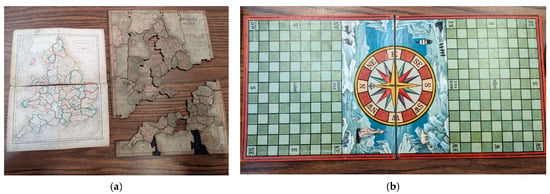

Many racing games derived from maps and drawings, sometimes detailed and accurate maps of real places. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, geography was a valued academic subject, but was often taught in dry ways (Alexander 1999, p. 6). In the growing market for board games, geography was “among the favorite subjects” because “travel was limited, even within England” (Liman 2017, p. 15). As relates to the construction of a self as traveler, games remind us that “[t]o a child in London, even Scotland, not to mention the continent, was far away” (Liman 2017, pp. 15–16). The games were one concrete and interactive way to understand one’s place in the larger networks of cities and towns, both at home and abroad. Indoor games that featured geography competed against the romantic allure of imaginative play in nature. In fiction and memoirs, indoor games are often depicted as the antithesis of travel and mobility. They are more often connected with adults than with children, who are instead depicted taking sides in physical games in a schoolyard. Yet, games and puzzles that repurpose maps turn geography into a game (Liman 2017).

The march across a century of geography games involves increasing abstraction and compression; as the sense of the world becomes less bounded, it becomes more challenging to fit everything onto one board. For example, any “dissection”—jigsaw puzzle (Nadel 1982)—such as A Map of England Dissected to Teach Youth Geography (Longman, Rees, Ohme, Brown & Green 1829, Figure 4a), rewards attention to minute local geographical detail. The pieces are cut alongside legal, official boundaries between counties, boundaries that the puzzle-makers want children to recognize and respect. Because dissections had to be completed with a silversmith’s saw, “and it being a matter of some difficulty to turn the saw accurately in a small circle” (Whitehouse 1971, p. 84), it is rare to see a puzzle that has this many small pieces; however, this puzzle is typical in having pieces that are not interlocking and a key based on an actual traveler’s map. By contrast, racing games of conquest and exploration tended to simplify the geographical map greatly, as in the Game of the Mariner’s Compass (McLoughlin Brothers 1890a, Figure 4b) that features only New York, London, and the game’s goal, the North Pole. This was one of several North Pole race games near the end of the century; in all cases the competition is “notable primarily for its attempts at national glory” (Heath 2021, p. 202). This game pits two players, one leaving from London and the other from New York, to see who can reach the North Pole first. This streamlined, goal-based approach to the geography of the world deals in extremes, reflecting the set moves of accounts of the feats of exploration that grabbed headlines during the era. Exploration offers an opportunity to collect material goods, to be sure, but also offers opportunities to display national grit and ingenuity, with the details of day-to-day travel eclipsed by the overarching race to the final goal.

Figure 4.

(a) A Map of England Dissected to Teach Youth Geography (Longman, Rees, Ohme, Brown & Green 1829). Left: The map provided with the puzzle pieces to guide the solve. Right: A partially solved puzzle. (b) Board of play for Game of the Mariner’s Compass (McLoughlin Brothers 1890a).

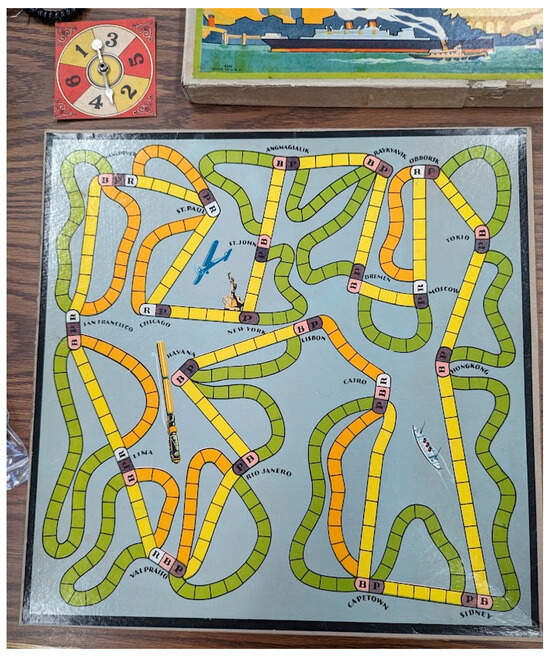

In some games, traveling in a wandering way is a barrier to success. Interest in the square on which one lands may lead one to lose a turn. For example, the games about a race to London made by Edward Wallis in the 1840s slowed the forward progress of players who stopped to learn more about picturesque rural places and out-of-the-way historical landmarks (Nadel 1982, p. 30). Such games installed a “double consciousness” “in which things players knew they should value, such as the picturesque, education, and hard work, became handicaps that would prevent them from winning in a world of rapid movement, superficial social arrangements, and amoral dedication to lucre” (Carroll 2017, p. 251). By the first decades of the twentieth century, a game like the Around the World Game (Milton Bradley Company 1930, Figure 5), tried to cram the whole world into a miniscule space, offering stops in major cities that approximate cardinal directions but ignore distance and scale. This is travelling as pure heady rush, about getting to know how cities relate to each other in space and more about moving faster and farther through more spaces than one’s opponent.

Figure 5.

Game board and spinner for Around the World Game (Milton Bradley Company 1930). Players begin and end play in New York, and the object of the game is to “complete the tour of the world and return to New York” more quickly than the other players. The mode of travel is the main determinant of speed. Some cities can be accessed by Railroad (R), Plane (P), or Boat (B), and others by boat or plane only. The mode of transportation on which one lands (R, B, or P) determines the route one must take to get to the next city. The green tracks are the longest route, orange next, and yellow the most direct.

Where racing games opened up the world—and a child’s sense of identity as belonging to a national team of sorts—similarly to narrative card-based games, is the work of imaginatively placing oneself in multiple, often foreign, roles. For instance, in The Mariner’s Compass game, an American child may have to race from London, and a British child from New York, and in the next play they may switch roles. Extant board games that depicted conquest in the form of war rather than exploration were often similarly international. Writes Davies, in his analysis of games such as Poles and Russians (1840s) and The New Game of the Siege of Paris (1871), “Victorians may indeed have had a fondness for playing with soldiers, but at least in extant boardgames, they were more likely to be Poles, Russians, Ottomans, Parisians, Prussians, or Boers than Britons. In other words, playing as the other” (Davies 2023, p. 277).

In contrast with moral or allegorical racing games, games based in geography focus on the collection of resources and tidbits of information, rather than the collection of virtues through, for example, patiently making one’s way from home to Sunday School (McLoughlin Brothers 1890b). Perhaps, however, there can be something inherently anti-imperial about playing even the most internationalist travel games. When playing a game, “participants must establish a shared understanding of the game’s rules, objectives, and strategies”, skills that allow them, even when playing against each other, to “communicate effectively, anticipate each other’s moves, and empathize with their opponents’ perspectives” (Davies 2023, p. 146). Through the elements of chance, one gets to experience what it feels like to win, and what it feels like to lose, perhaps multiple times in one day.

4. Conclusions

Robert Louis Stevenson, writing in the 1870s about a child’s feelings of wonder, argued for a child’s dependence on props to help them learn how to move through space independently and with confidence. For a child, even small distances can be daunting. He pictured the average small child “wheeled in perambulators or dragged about by nurses in a pleasing stupor” (Stevenson 1878, p. 353), in lost opportunities to encourage a love of exploration. A child’s movement through space, he argues, must be concretized and embodied. Unlike an adult who can sit still and imagine himself flying or riding or jumping, a child must enact the movements he imagines. If a child wants to imagine climbing a mountain he will seek a cabinet or sofa, and “[w]hen he comes to ride with the king’s pardon, he must bestride a chair” (Stevenson 1878, p. 354). If there is something to Stevenson’s hypothesis—some truth to the idea that mental or symbolic motion must be taught, and actual physical motion is a vehicle for the teaching—then the invention of board games and card games becomes to travel what the dollhouse becomes for practice managing a household. Rather than merely look at maps or wonder what it could be like to travel the entire world in a day or engage the diversity of a bustling city, miniaturized versions of cities, counties, and countries can bring travel to life for children. The games facilitate the process of moving from the literal to the symbolic, setting the stage for more appreciative engagement with narrative. Stevenson, a world traveler and a writer of several travel narratives that are now children’s classics, also wrote in 1880, “Fiction is to the grown man what play is to the child”, cementing the idea that games and stories are partners in the trajectory of human development (qtd in Rosen 1995, p. 55). Or, as Susan Stewart writes, “the toy is the physical embodiment of the fiction: it is a device for fantasy, a point of beginning for narrative” (Stewart 1993, p. 56).

Unlike games like checkers, chess, and Whist, which originated long enough ago for the rules to be generally known (by adults, anyway), and easily translated orally from one generation to another as a leisure-time rite of passage, new commercial board games are the invention of one or a few adults, drawing on existing games but also trying to present something entirely new. The rules of each new game have to be learned by everyone who opens the new box and turns to the newly printed instructions. As anyone who has taken the time to learn a new game surely knows, the first play is a struggle. At times, the smooth game play that emerges is riddled with errors that may never be detected by the players. Sometimes the errors become specific to the group that collectively overlooked aspects of the printed instructions. The crowd-sourced adjustments may supplant the official rules, even after the habitual error is detected. If one is to compare this kind of gameplay to narrative, one could think about the tension between authorial intent and reader response, or the role that readers can play in demanding adjustments in real time when reading serial fiction. As with serialized fiction, games are meant to be a repeated experience, and mix familiar elements with unexpected variations. Certain elements stay the same and are reinforced through repetition, but the smallest variations can change the entire outcome of who wins and who loses. A mixture of chance and will can change outcomes, within the framework of how the game is meant to be played (the contract between creators and users). However, that contract can be as tenuous as any other kind of authority, and it is hard to police what individuals will do with the piece of culture once it is unboxed.

So, what relations do we see between the stories about travel offered by commercial games and actual travel through space? What relationship do we see between stories about travel offered by commercial games and imaginative works of fiction? Narrative card games showed children the internal complexity of changing urban centers, while racing games collapsed distances to make the world seem more knowable. In an analysis limited to the nineteenth century, “Teetotum Lives”, Siobhan Carroll suggests that formal game play for children becomes less subversive over time, and more commercialized, as games began to double as overt advertisements for leisure travel. This project is a call to continue tracking paths through the history of gaming, paths that may accommodate regressions, substitutions, pauses, and accelerations. As with the history of literature, in which imaginative works reflect the exigencies of wartime and armistice, feast and famine, conquest and liberation, so, too, may the history of games find stops and starts as humans learn to move through increasingly cramped and interconnected urban spaces.

It would be worth our while to carry such investigations into the present day. A recent Wirecutter advertisement in The New York Times (Wirecutter 2024) touted the 10th anniversary edition of Tokaido (Funforge 2013; Figure 6), a travel game that takes players to “Edo-era Japan”, (seventeenth–nineteenth centuries).

Figure 6.

Advertising Image for Tokaido (Funforge 2013), featuring a White, presumably Western nuclear family “traveling” through Edo-era Japan. The image hearkens to the racing games’ focus on rapid, near simultaneous game play. The image runs counter to the marketing of the game as a turn to a more leisurely, non-competitive, and even respectful re-pacing of foreign travel. Photo credit: Funforge (Wirecutter 2024).

Children of all ages and nationalities have to travel imaginatively in such a game, because Edo (now Tokyo) can no longer be visited in its previous form. Players travel the historic route in a counterintuitive way, as well. As they travel the old road from Kyoto to Edo, they are asked to play slowly, take many stops along the way, and to “reve[l] in the simple pleasures of traveling” (Wirecutter 2024). Attending to the details on the board, linked to historical facts and objects, is how one becomes the “best traveler”, which means savoring “the richest experience by seeing, eating, or doing the most during your trip” (Wirecutter 2024). This game is a combination of racing game and narrative card game, in that players have tokens they move around the board, and cards that describe the people they meet, the experiences they have, the souvenirs they purchase, and the food they sample. A set number of tokens determine what and how many experiences can be purchased. Experiences include stopping for panoramic views of the landscape or relaxing at hot springs. Panorama cards are collected one by one, as “books”, and players collect achievement points for each panorama. There are no spinners or dice to determine how far a player moves on a given turn. Instead, the player who is farthest behind always moves next, and the game does not end until the last player reaches the final inn on the board. The game feels deliberately old-fashioned, but as we have seen, this is a relatively new-fangled way to figure travel in a game, as the first commercial racing games for children privileged speed over leisure, acquisition over relaxation.

Children playing Tokaido engage with the future of travel rather than the past, even while playing a game that represents an inaccessible part of the past. Tokaido represents a kind of non-competitive anti-racing game that still manages to be commercial, though what is being marketed is a leisurely stroll through what almost feels like an imagined utopic space. If it is a strategic game, its strategy favors accumulation, but accumulation of intangible or temporary goods and experiences, such as a fine meal or a beautiful view. Since its introduction, the Tokaido experience has evolved, adding expansion packs, multiple variations of play, and deluxe editions to the base offerings. As with sequels or remakes of existing stories, this strategy board game has evolved, and may certainly have had an impact on what travel games may look like in the future.

There was no such thing as a “strategic race game” in the nineteenth century, or for that matter most of the twentieth century. This means that there was no opportunity for players to decide fully and completely how they wanted to move their pieces without reliance on spinners, cards, or dice (Partlett 1999). In that way, the movement of a player through the rules of a game is not dissimilar from the movement of a reader through a published work of fiction—unless they are determined to be deeply resistant readers. Even when race games offer short cuts and zig-zags, as with mystery stories that offer red herrings, the games “remai[n] essentially linear in the sense that a piece can move only forwards or backwards, but not sideways except at a few points specifically marked as short cuts” (Partlett 1999, p. 10). Although Tokaido eliminated spinners and dice in favor of strategic choices on the part of players, the path from beginning to end of the experience remains linear. Skipping and skimming while reading is not unheard of (see Price 2000) but isn’t yet part of the officially sanctioned mores of reading outside of the very common practice of abridgments or simplifications for children. If we think of the games themselves as simplifications or abridgments of real travel, then, as with a story to be reread to the point of memorization, games, played repeatedly with minor variations, are meant to offer a form of training (Davies 2023, p. 142). Just as narratives of travel draw on gaming as a trope, commercial games draw on narrative tropes (Stewart 1993, p. 56; Carroll 2017, p. 36). The tension between structure and spontaneity, will and chance, varies how children learn to construct themselves as travelers and readers.

Funding

This research received funding from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, in the form if a year-long senior faculty research leave. I also received the Mary Valentine and Andrew Cosman Fellowship for summer research in the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to attendees of the Interdisciplinary Nineteenth Century Studies Association conference (2024), for invaluable feedback on a draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alexander, Christine. 1999. Africa as Play in the Childhood of the Brontës. The Journal of African Travel-Writing 6: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Augarde, Tony. 1984. The Oxford Guide to Word Games. Oxford: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Averill, Graham. 2023. The Worst National Park Reviews of the Year. Outside Magazine. Available online: https://www.outsideonline.com/adventure/travel/national-parks/worst-national-parks-reviews/ (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Braun, Adee. 2019. Before American Got Uncle Sam, It Had to Endure Brother Jonathan. Atlas Obscura. Available online: https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/brother-jonathan-uncle-sam (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Carroll, Siobhan. 2017. ‘Play You Must’: Villette and the Nineteenth-Century Board Game. Nineteenth Century Contexts 39: 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Siobhan. 2021. Teetotum Lives: Mediating Globalization in the Nineteenth Century Board Game. In Playing Games in Nineteenth Century Britain and Americ. Edited by Ann R. Hawkins. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 243–61. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Gavin. 2023. Rules Britannia: Board Games, Britain, and the World, c. 1759–1860. Unpublished Dissertation, History, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK. [Google Scholar]

- EE Fairchild Corporation. 1945. Game of Cities: An All Fair Game. New York: EE Fairchild Corporation. First published 1932. Available online: https://wopc.co.uk/usa/fairchild/cities (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Funforge. 2013. Tokaido. Paris: Funforge. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, Douglas A. 2018. Slantwise Moves: Games, Literature, and Social Invention in Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, Michelle Beissel. 2021. The United States as Wonderland: British Literature, U.S. Nationalism, and Nineteenth-Century Children’s and Family Board and Card Games. In Playing Games in Nineteenth-Century Britain and America. Edited by Ann R. Hawkins, Erin N. Bistline, Catherine S. Blackwell and Maura Ives. Albany: SUNY Press, pp. 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, A. Robin. 2017. Introduction. In Georgian and Victorian Board Games: The Liman Collection. Edited by Ellen and Arthur Liman. New York: Pointed Leaf Press, pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- James, Henry. 1923. What Maisie Knew. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. First published 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Matthew. 2012. The World in Play: Portraits of a Victorian Concept. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlovsky, Roy. 2013. The Architectures of Childhood. In The Children’s Table: Childhood Studies and the Humanities. Edited by Anna Mae Duane. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, Part 3, n.p. [Google Scholar]

- Liman, Ellen. 2017. Georgian and Victorian Board Games: The Liman Collection. New York: Pointed Leaf Press. [Google Scholar]

- Longman, Rees, Ohme, Brown & Green, publishers. 1829. A Map of England Dissected to Teach Youth Geography. London: Paternoster Row. [Google Scholar]

- Macauley, James. 1875. Parlour Games. The Leisure Hour: A Family Journal of Instruction and Recreation 1204: 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, Josephine. 2021. Literature in a Time of Migration: British Fiction and the Movement of People, 1815–1876. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin Brothers. 1880. Game of the City Traveler. New York: McLoughlin Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin Brothers. 1890a. Game of the Mariner’s Compass. New York: McLoughlin Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin Brothers. 1890b. Games of the Pilgrim’s Progress. Going to Sunday School and the Tower of Babel. New York: McLoughlin Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Milton Bradley Company. 1910. Brother Jonathan in London. Springfield: Milton Bradley Company. [Google Scholar]

- Milton Bradley Company. 1930. Around the World Game. Springfield: Milton Bradley Company. [Google Scholar]

- Nadel, Ira Bruce. 1982. ‘The Mansion of Bliss’, or the Place of Play in Victorian Life and Literature. Children’s Literature 10: 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, John. 1825. Brother Jonathan; or, The New Englanders. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. [Google Scholar]

- Norcia, Megan A. 2004. Playing Empire: Children’s Parlor Games, Home Theatricals, and Improvisational Play. ChLA Quarterly 29: 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partlett, David. 1999. The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Leah. 2000. The Anthology and the Rise of the Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Michael. 1995. Robert Louis Stevenson and Children’s Play: The Contexts of A Child’s Garden of Verses. Children’s Literature in Education 26: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, James. 1973. The Milton Bradley Story. New York: Newcomen Society in North America. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Leonard. 2024. The History of Mad Libs. Available online: https://www.madlibs.com/history/ (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Stevenson, Robert Louis. 1878. “Child’s Play”. The Cornhill Magazine 37: 352–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Susan. 1993. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2024. Uncle Sam. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Uncle-Sam (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Wasowicz, Laura E., Lauren B. Hewes, Justin G. Schiller, and Kayla Haveles Hopper. 2017. Radiant with Color and Art: McLoughlin Brothers and the Business of Picture Books. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, Francis Reginald Beaman. 1971. Table Games of Georgian and Victorian Days, 2nd ed. Dunstable: Priory Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Wirecutter. 2024. Armchair travel to Japan. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/gifts/best-for-travelers/ (accessed on 4 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).