Abstract

Yi’an Reservoir is located on a major tributary of the Baoquan River and hosts abundant aquatic resources, with Cyprinus carpio, Carassius auratus, and Hemiculter leucisculus as the dominant fish species. Water quality parameters significantly shape fish gut microbiota, which in turn plays a crucial role in host physiological functions. This study aimed to characterize the water quality parameters in Yi’an Reservoir and identify the microbial communities in both the aquatic environment and fish guts (C. carpio, C. auratus, and H. leucisculus) through 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing. The objective was to examine the associations of water quality parameters and aquatic environmental microbiota with the assembly of gut microbial communities in fish inhabiting this reservoir system. The water quality parameters showed significant site-specific differences, of which temperature and dissolved oxygen were highest at Location B, while pH was highest at Location A. The Cyanobium_PCC-6307 was identified as a major differentially abundant taxon at the genera level across different sampling sites. Furthermore, the gut microbiota of the same fish species exhibited substantial variation across different sampling sites. Redundancy analysis identified distinct environmental drivers at each location. Specifically, pH, conductivity, and total dissolved solids (TDS) showed positive correlations with the gut microbiota at Location A. In contrast, temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and the environmental abundance of Cyanobium PCC-6307 were positively correlated with the gut microbiota at Locations B and C. This study provides important insights for the conservation and management of aquatic resources in reservoir ecosystems.

Keywords:

16S ribosomal RNA sequencing; Cyanobium_PCC-6307; redundancy analysis; microbial community assembly; environmental drivers Key Contribution:

1. pH, conductivity, and total dissolved solids (TDS) was identified as a key driver shaping the assembly of fish gut microbiota collected at Location A. 2. Temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and cyanobacterial abundance were found to be key drivers influencing the assembly of fish gut microbiota obtained from Locations B and C.

1. Introduction

The microbiota in water environments constitutes a vast, complex, and ecologically essential component of global ecosystems, comprising diverse microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi, and protists) that inhabit aquatic systems. This aquatic microbial community plays a fundamental role in driving energy flow and biogeochemical cycling within aquatic environments [1,2,3]. Far from a passive assemblage, it functions as a dynamic and interconnected network that regulates the ecological health and functioning of water bodies worldwide. Thus, it is integral to global biogeochemical processes, climate modulation, and societal sustainability [4,5].

The genetic characteristics of gut microbes have garnered substantial research interest in recent years, as the intestinal microbiota is frequently regarded as the “second genome” of animals and plays a crucial role in host physiology [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. It has been established that distinct microbial compositions influence host homeostasis, physiological functions, metabolic profiles, growth, and susceptibility to disease [13,14,15,16]. The gut microbiota, dominated by bacterial phyla such as Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (alongside Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and others), as well as fungi (e.g., Candida, Saccharomyces), viruses, and archaea, is essential for the host [17,18,19].

Some studies indicate that fish species serves as a primary determinant in shaping intestinal microbial communities [20,21]. Each species may develop its own specific microbial symbionts, influenced by factors such as dietary habits, microhabitat preferences, and mating behavior, which collectively shape host-specific ecological traits [22]. Beyond this, aquatic environmental factors also play a significant role in shaping distinct microbiota enterotypes [23,24,25], which in turn facilitate the adaptation of host fish to environmental changes [26,27,28,29,30], highlighting a dynamic bidirectional interaction between host and microbiome. The gut microbiota significantly influences host stress responses by modulating feeding behavior and energy homeostasis [31,32], and there is evidence it can even affect brain function [33]. The gut is also recognized as a reservoir for discovering novel microbial species [34].

16S ribosome RNA (16S rRNA) gene sequencing is a foundational molecular method for bacterial identification and microbiome analysis. Its core principle involves sequencing the hypervariable regions of the conserved 16S rRNA gene, which is present in all bacteria. By comparing the resulting sequences against public taxonomic databases (e.g., Silva), researchers can accurately classify known bacterial species and discover novel ones. This technique is particularly crucial for analyzing complex, mixed-bacterial communities, such as those found in environmental or human microbiome samples. It works by assigning taxonomic identities to sequenced reads and using their abundance to calculate the relative frequency of different organisms within a sample [35]. Consequently, 16S rRNA sequencing has become the standard and reliable approach for profiling the composition and relative abundance of bacteria in diverse ecosystems [36].

Yi’an Reservoir is located in Qiqihar City, Heilongjiang Province, situated on a primary tributary of the Baoquan River, with a controlled watershed area of 2.9 square kilometers. It plays a significant role in flood control, irrigation, and aquaculture, safeguarding the lives and property of residents in the downstream areas [37]. Yi’an Reservoir boasts abundant aquatic resources, with Cyprinus carpio, Carassius auratus, and Hemiculter leucisculus constituting its dominant naturally occurring fish species. C. carpio, recognized as one of major freshwater fish species in China with annual production of over 3 million tons in 2024, possesses substantial economic and nutritional importance. It is extensively cultivated in northern China owing to its palatable flesh and strong disease resistance [38]. C. auratus is an important species of freshwater cultured fish in China with the annual production of 2.85 million tons in 2024 [39]. H. leucisculus are small omnivore freshwater fish with a wide distribution in the drainage basin of countries of East Asia [40]. They are abundant and are easily caught for sampling.

Based on this background, we hypothesized that the assembly of fish gut microbiota is linked to both water quality parameters and the aquatic environmental microbiota in Yi’an Reservoir, thereby impacting the physiological functions of local fish species. Consequently, a systematic investigation into the relationships among water quality parameters, aquatic environmental microbiota, and fish gut microbiota assembly within this reservoir system is imperative. In the present study, water quality parameters were measured at three sampling sites in the Yi’an Reservoir. Additionally, the microbial communities in both the water environments and the intestinal tracts of fish species (C. carpio, C. auratus, and H. leucisculus) collected from these sites were analyzed using 16S rRNA sequencing to investigate the distribution, diversity, and abundance of microbiota across these samples. The findings offer valuable insights into the associations between the gut microbiota of fish and water quality parameters, as well as aquatic microbial communities, within the Yi’an Reservoir ecosystem.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measurement of Water Qualities

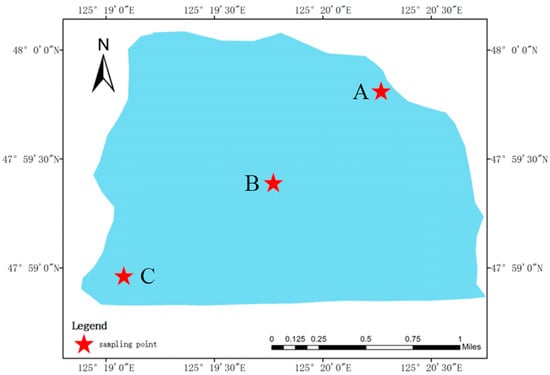

Water quality parameters were monitored at 9:00 a.m. across three sampling sites within Yi’an Reservoir during the autumn period from 17 to 19 September 2025: the upstream (Location A, 125°19′38″ E, 47°59′03″ N), the midstream (Location B, 125°20′18″ E, 47°59′35″ N), and the downstream (Location C, 125°20′45″ E, 48°00′06″ N) (Figure 1). The distances between Location A and Location B, as well as between Location B and Location C, are each approximately 3 km. At each sampling site, measurements were taken at three distinct points spaced 50 m apart. Surface water samples were collected at a consistent depth of 0.5 m below the water surface at each of these points. A multiparameter water quality meter (Henxin 86031, Dongguan, Guangdong, China) was used to determine pH, water temperature, dissolved oxygen concentrations, conductivity and total dissolved solids (TDS).

Figure 1.

Sampling locations for water and fish in Yi’an Reservoir. Sites A, B, and C denote the three sampling sites in the present study.

2.2. Isolation of Microbiota from Water Samples and Fish Samples

Water and fish samples were collected concurrently from the three sampling sites at 9:00 a.m. each day. For water sampling, a 1 km2 square area was delineated at each location. From each square, a total of 2 L of water was, respectively, collected at a depth of 0.5 m below the surface at the center and four corners. The collected water was then composited to obtain a representative sample of the microbiota in each water environment [41]. Each composite sample was placed in sterile jars and immediately filtered in triplicate through 0.22 µm sterile membranes using a manual pump equipped with a sterile filtration unit. The filters were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction.

In the present study, specimens of C. carpio, C. auratus, and H. leucisculus were collected at each sampling site. Eight sampling points were established per site along a 1000 m river reach. Fish were collected using five mesh gill nets (mesh sizes: 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 cm; net height: 1 m; length: 200 m each) and three bottom-set cages (length: 80 m, height: 0.4 m, mesh: 0.5 cm). The total length, body length, and body weight of each fish specimen are provided in Table 1. Gut tissues were immediately collected from 15 individuals of each fish species at each sampling site after capture. The entire gut tract was dissected from each individual fish. For each fish species at each sampling site, the gut tissues from five individuals were pooled to form one biological replicate. Three biological replicates were prepared per site. All gut samples were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction.

Table 1.

The body size of the sampled fish.

2.3. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

Prior to DNA extraction, filters were washed with three washing solutions [Tris-HCl (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), EDTA (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and Triton X-100 (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)] to remove extracellular DNA and improve PCR amplification efficiency [42]. Total microbial genomic DNA was extracted from water samples and fish gut samples using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA quality was assessed by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis, and concentration was measured with a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

The hypervariable V3–V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) [43] using an Eppendorf thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). PCR was carried out in 20 µL reactions containing 4 µL of 5× Fast Pfu buffer (Tiangen, Beijing, China), 2 µL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 µL of each primer (5 µM), 0.4 µL of Fast Pfu polymerase, 0.2 µL of BSA, 10 ng of template DNA, and ddH2O to volume. Thermal cycling conditions were: 95 °C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min and hold at 4 °C. All samples were amplified in triplicate.

PCR products were visualized on 2% agarose gels and purified with the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified amplicons were quantified using a Quantus™ Fluorometer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Sequencing libraries were prepared with the NEXTFLEX Rapid DNA-Seq Kit following the supplier’s guidelines. Amplicon sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform (Shanghai Meiji Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

2.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

Raw FASTQ files from all water and fish gut samples were demultiplexed with a custom Perl script. Subsequently, sequence reads were quality-filtered and trimmed using fastp version 0.19.6 [44], and overlapping paired-end reads were merged using FLASH version 1.2.7 [45]. The resulting high-quality sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold using UPARSE version 7.1 [46]. The most abundant sequence within each OTU was selected as its representative sequence. Taxonomic classification of each OTU representative sequence was performed with the RDP Classifier version 2.2 [47] against the SILVA 16S rRNA gene database (release 138) under a confidence threshold of 0.7, yielding the final annotated taxonomy table [48].

Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was performed using the R package microeco version 0.2.1 [49] to identify microbial taxa with statistically significant differences in the gut microbiota of the same fish species sampled from different sites, based on the OTU data. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted using the R package vegan [50] to examine the associations of water quality parameters and aquatic environmental microbiota with the composition of fish gut microbial communities. All data visualizations were generated with the R package ggplot2 [51].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences in water quality parameters among the three sampling sites were assessed by one-way analysis of variance, followed by the least significant difference post hoc test. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement of Water Qualities

The water quality parameters of the three sampling sites are summarized in Table 2, including water temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, and TDS. The water temperatures at locations A, B, and C were 16.8–17.0 °C (mean ± SD: 16.87 ± 0.12 °C), 18.9–19.4 °C (19.2 ± 0.26 °C), and 17.1–17.5 °C (17.33 ± 0.21 °C), respectively. The temperature at location B was significantly higher than at locations A and C (p < 0.05). The pH at location A ranged from 9.65 to 9.93 (9.76 ± 0.15), which was significantly higher than at location B (8.82–9.01; 8.91 ± 0.01) and location C (8.85–9.12; 8.96 ± 0.14) (p < 0.05). Dissolved oxygen at location B ranged from 8.2 to 8.5 mg/L (8.37 ± 0.15 mg/L), significantly exceeding levels at location A (6.9–7.2 mg/L; 7.07 ± 0.15 mg/L) and location C (7.6–7.8 mg/L; 7.7 ± 0.1 mg/L) (p < 0.05). At location B, conductivity and TDS ranged from 189.2 to 189.7 (189.43 ± 0.25) and 94.5 to 94.8 (94.67 ± 0.15), respectively. These values were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than those recorded at location A (conductivity: 188.2–189.1, 188.73 ± 0.47; TDS: 94.0–94.3, 94.17 ± 0.15) and location C (conductivity: 184.1–184.5, 184. 33 ± 0.21; TDS: 90.7–91.2, 90.9 ± 0.26).

Table 2.

The measurement of water qualities in three sampling sites.

3.2. The Changes in Bacterial Phylum in Water Samples Across These Three Sampling Sites

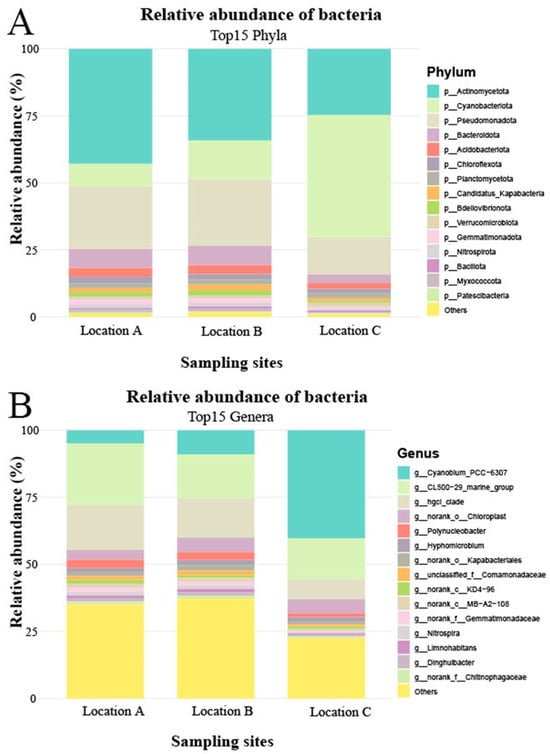

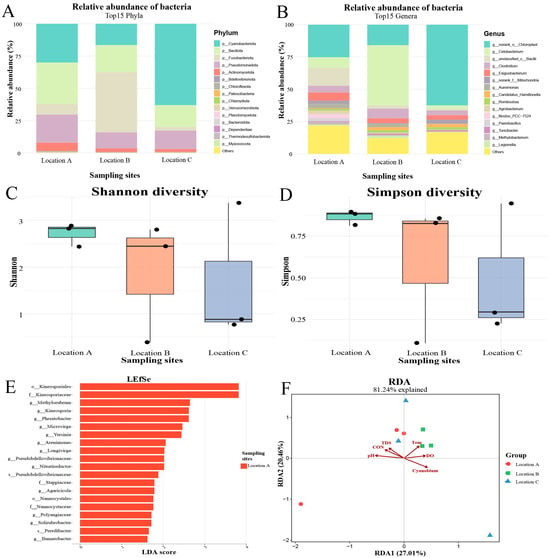

Although the water samples analyzed in the present study exhibited similar bacterial taxonomic composition, significant differences were observed in the relative abundances at both the phylum and genus levels. Bacterial communities at Locations A and B demonstrated comparable abundance patterns at taxonomic levels. At the phylum level, Actinomycetota dominated in water samples from Locations A and B, followed by Pseudomonadota and Cyanobacteriota. In contrast, Cyanobacteriota was the most abundant phylum in Location C, with Actinomycetota and Pseudomonadota ranking second and third, respectively (Figure 2A). At the genus level, the dominant identified taxa in Locations A and B were CL500-29_marine_group, followed by hgcI_clade and Cyanobium_PCC-6307. Conversely, Cyanobium_PCC-6307 predominated in Location C, succeeded by CL500-29_marine_group and hgcI_clade (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Microbial community composition in water samples. Panel (A) shows the distribution of bacterial phyla as a percentage of the total identified sequences for each water sample. Panel (B) displays the distribution of bacterial genera as a percentage of the total identified sequences for each water sample.

The Shannon diversity indices for Locations A, B, and C were 3.45, 3.62, and 2.74, respectively, while the corresponding Simpson indices were 0.91, 0.93, and 0.80. Notably, Cyanobium_PCC-6307 emerged as the major differentially abundant taxon among the three sampling sites and may potentially influence the assembly of the gut microbiota in fish.

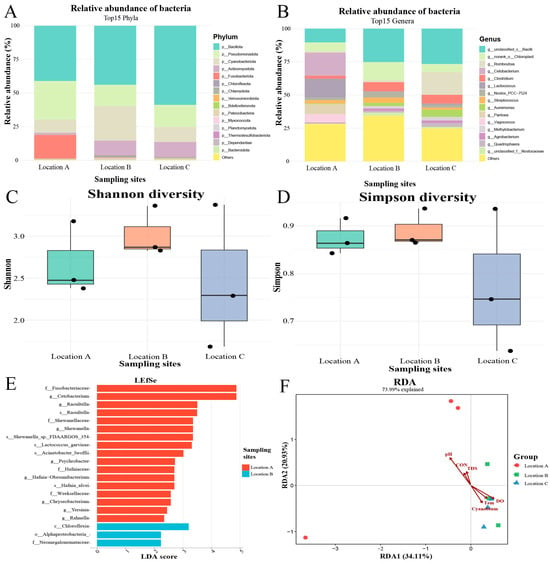

3.3. Associations Between Water Qualities and Gut Microbiota Composition in C. carpio

The gut microbiota of C. carpio across the three sampling sites was characterized at both the phylum and genus levels. At the phylum level, Bacillota was identified as the dominant bacterial phylum in all examined individuals, though its relative abundance varied greatly among different sampling sites. In fish sampled from Location C, Bacillota accounted for over 50% of the bacterial community, whereas its relative abundance in Locations A and B was approximately 40% (Figure 3A). Additionally, the second and third most abundant phyla in Locations A and C were Pseudomonadota and Cyanobacteriota, respectively, while in Location B this ranking was reversed, with Cyanobacteriota exceeding Pseudomonadota in relative abundance (Figure 3A). At the genus level, the most abundant identified microbiota in Locations B and C was unclassified_c__Bacilli, whereas in Location A the predominant genus was Cetobacterium (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Associations of water quality parameters with the gut microbial community of C. carpio. (A) Relative abundance of bacterial phyla in each gut sample. (B) Relative abundance of bacterial genera in each gut sample. (C) Shannon diversity indices of the gut microbiota. (D) Simpson diversity indices of the gut microbiota. (E) Differentially abundant microbial taxa in fish guts across sampling sites. (F) RDA of the influence of water quality parameters on gut microbial composition. CON: conductivity; Cyanobium: Cyanobium_PCC-6307; DO: dissolved oxygen; TDS: total dissolved solids; Tem: temperature.

The Shannon diversity indices for fish sampled from Locations A, B, and C were 3.00, 3.14, and 2.90, respectively (Figure 3C), whereas the corresponding Simpson indices were 0.91, 0.90, and 0.88 (Figure 3D). The LEFSe method was employed to identify microbial biomarkers and representative taxa exhibiting significant differences in the gut microbiota of C. carpio, C. auratus, and H. leucisculus across distinct sampling sites. Compared to the other two sites, a total of 17 significant biomarkers were detected in the guts of fish from Location A, while three were identified in those from Location B. In contrast, no significant biomarkers were found in specimens from Location C. The most differentially abundant biomarkers in Location A included Fusobacteriaceae and Shewanellaceae at the family level, Cetobacterium and Raoultella at the genus level, and Raoultella at the species level. For Location B, the differential biomarkers comprised Chloroflexia at the class level, Alphaproteobacteria at the order level, and Neomegalonemataceae at the family level (Figure 3E).

RDA revealed that pH, conductivity, and TDS were positively correlated with the gut microbiota from Location A, but negatively correlated with those from Location C. In contrast, temperature, DO, and the environmental abundance of Cyanobium PCC-6307 showed positive correlations with the gut microbiota in Location C, while displaying negative correlations in Location A (Figure 3F).

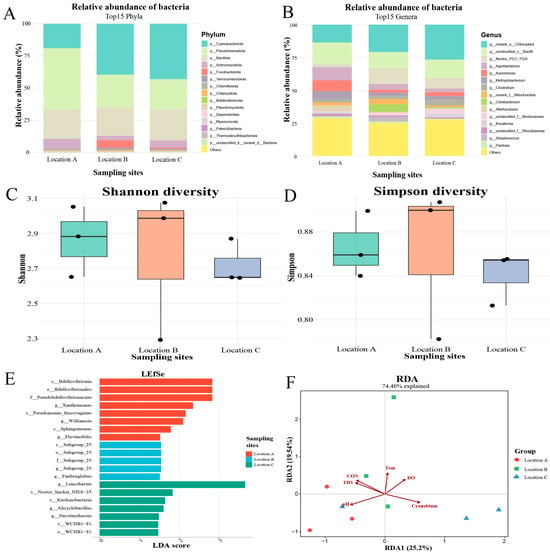

3.4. Associations Between Water Qualities and Gut Microbiota Composition in C. auratus

At the phylum level, Cyanobacteriota was the most abundant microbiota in individuals from Locations B and C, comprising approximately 40% of the bacterial community. In contrast, Pseudomonadota dominated in individuals from Location A, accounting for about 50% of the total (Figure 4A). At the genus level, norank_o__Chloroplast was the most abundant taxon in Locations B and C, whereas in Location A the dominant genus was unclassified_c__Bacilli (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Associations of water quality parameters with the gut microbial community of C. auratus. (A) Relative abundance of bacterial phyla in each gut sample. (B) Relative abundance of bacterial genera in each gut sample. (C) Shannon diversity indices of the gut microbiota. (D) Simpson diversity indices of the gut microbiota. (E) Differentially abundant microbial taxa in fish guts across sampling sites. (F) RDA of the influence of water quality parameters on gut microbial composition. CON: conductivity; Cyanobium: Cyanobium_PCC-6307; DO: dissolved oxygen; TDS: total dissolved solids; Tem: temperature.

The Shannon diversity indices for fish sampled from Locations A, B, and C were 2.95, 2.99, and 2.94, respectively (Figure 4C), whereas the corresponding Simpson indices were 0.88, 0.90, and 0.88 (Figure 4D). The LEFSe analysis identified 8, 5, and 7 significant microbial biomarkers in the fish guts from Location A, B, and C, respectively. The most differentially abundant biomarkers in Location A were represented by Bdellovibrionia at the class level, Bdellovibrionales at the order level, Pseudobdellovibrionaceae at the family level, Xanthomonas at the genus level, and Pseudomonas fuscovaginae at the species level. In Location B, the differential biomarkers comprised taxa assigned to Subgroup_25 across class, order, family, and genus levels, alongside Fimbriiglobus at the genus level. For Location C, the most notable biomarkers included Leucobacter, Alicyclobacillus, and Parviterribacter at the genus level, Nostoc linckia NIES-25 at the species level, and Ktedonobacteria at the class level (Figure 4E).

RDA revealed positive correlations between the gut microbiota sampled from Location A and pH, conductivity, and total TDS, whereas DO and the environmental abundance of Cyanobium PCC-6307 showed negative correlations. In contrast, at Location C, temperature was negatively associated with gut microbiota composition. These environmental factors, however, showed only limited associations with the gut microbiota at Location B (Figure 4F).

3.5. Associations Between Water Qualities and Gut Microbiota Composition in H. leucisculus

At the phylum level, Bacillota was the most abundant microbiota in individuals from Location A, representing approximately 30% of the total microbial community, while Fusobacteriota and Cyanobacteriota predominated in Locations B and C, accounting for about 50% and 65%, respectively (Figure 5A). At the genus level, Cetobacterium was the dominant taxon in Location B, comprising roughly 50% of the microbiota. In contrast, norank_o__Chloroplast was the most abundant genus in Locations A and C, representing approximately 25% and 65% of the total microbiota, respectively (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Associations of water quality parameters with the gut microbial community of H. leucisculus. (A) Relative abundance of bacterial phyla in each gut sample. (B) Relative abundance of bacterial genera in each gut sample. (C) Shannon diversity indices of the gut microbiota. (D) Simpson diversity indices of the gut microbiota. (E) Differentially abundant microbial taxa in fish guts across sampling sites. (F) RDA of the influence of water quality parameters on gut microbial composition. CON: conductivity; Cyanobium: Cyanobium_PCC-6307; DO: dissolved oxygen; TDS: total dissolved solids; Tem: temperature.

The Shannon diversity indices for fish sampled from Locations A, B, and C were 2.96, 1.23, and 1.96, respectively (Figure 5C), whereas the corresponding Simpson indices were 0.89, 0.75, and 0.60 (Figure 5D). LEFSe analysis identified a total of 20 significant microbial biomarkers in fish guts from Location A, whereas no significant biomarkers were detected in samples from Location B and Location C. The most differentially abundant biomarkers in Location A were Kineosporiales at the order level, Kineosporiaceae at the family level, and the genera Methylorubrum, Kineosporia, and Phreatobacter (Figure 5E).

RDA revealed that the pH value showed a positive correlation with the gut microbiota sampled from the Location A, but the environmental abundance of Cyanobium_PCC-6307 showed a negative correlation. In contrast, temperature and DO were positively correlated with the gut microbiota of individuals from the Location B (Figure 5F).

4. Discussion

Yi’an Reservoir, a major tributary of the Baoquan River, supports rich aquatic resources. Fish gut microbiota plays diverse functional roles, such as facilitating digestion, promoting nutrient assimilation, modulating immune responses, and supporting overall growth and productivity [37]. Nevertheless, the association of water quality and environmental microbiota on the assembly of fish gut microbial communities remains poorly understood in Yi’an Reservoir. This study therefore aimed to measure key water quality parameters at three sampling sites and characterize the microbiota in both water and fish gut samples collected from these locations. Through this approach, the ultimate goal is to elucidate the regulatory effects of water quality and environmental microbial communities on the assembly of gut microbiota in fish inhabiting Yi’an Reservoir.

In the present study, the water temperature, DO, conductivity and TDS sampled from the Location B was significantly higher than other sampling sites, while the pH value at Location A was significantly higher than other sampling sites. In addition, the diversity of Cyanobium_PCC-6307 at the genera level showed significant difference among the sampling sites, indicating Cyanobium_PCC-6307 was the main environmental microbiota, which was sensitive to the changes in water environment. This finding aligns with previous studies indicating that water quality parameters serve as key drivers in shaping microbiota communities in aquatic environments [52,53]. Cyanobium PCC-6307 is widely distributed across diverse freshwater environments, including lakes, reservoirs, and rivers. It constitutes a core microbial component within both water columns and sediments of many freshwater ecosystems, particularly in reservoirs [54]. Variations in its abundance can indicate changes in water trophic status or broader ecological shifts [55]. Cyanobium performs oxygenic photosynthesis, using light energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into organic compounds while releasing oxygen. In parallel, Cyanobium functions as a foundational element of aquatic food webs, facilitating carbon fixation through photosynthesis and supplying energy to zooplankton and organisms at higher trophic levels [56].

In the present study, the overall taxonomic composition of dominant bacteria in the guts of conspecific fish was generally similar across sampling sites. However, notable variations were observed in the relative abundances of both phyla and genera, indicating that water quality parameters and the ambient microbial community significantly influence the structure of the intestinal microbiota in fish from Yi’an Reservoir, which is consistent with the previous publications. In Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), developmental shifts in gut bacterial communities closely paralleled changes in the surrounding water microbiota, with successful transfer of water-derived bacteria into the intestinal tract [57]. Differences in water management have been shown to alter the microbiota of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) larvae, especially between recirculating aquaculture systems and flow-through systems [58]. Furthermore, when water treatment systems were modified, no persistent legacy of initial rearing conditions was detected in cod microbial communities; instead, the host microbiota shifted in synchrony with environmental changes [59]. The structure and composition of the microbiota in the Heilongjiang River have been found to directly influence and modulate the gut microbial communities of resident fish populations [41]. Under such low-stress conditions, stochastic processes appear to govern the introduction of transient waterborne microbes into the host [60,61]. The prevailing understanding, that fish microbiota is strongly influenced by and co-vary with the ambient microbial community, is now well-accepted and informs microbial management strategies in commercial aquaculture [62].

Several studies have employed multiple linear regression in conjunction with RDA to assess the relationships between predictor variables and individual response variables [63,64,65,66]. RDA is recognized as a particularly suitable method for analyzing the influence of water quality parameters on the structure of intestinal microbiota communities in fish [41,67]. In the present study, the RDA results suggest distinct environmental influences on gut microbiota composition across different sampling sites. At Location A, pH, conductivity, and TDS were consistently positive correlation with the gut microbiota of all three fish species. In contrast, at Locations B and C, temperature, DO, and the environmental abundance of Cyanobium PCC-6307 generally showed positive associations. These patterns imply that pH, conductivity, and TDS may function as a primary environmental regulator at Location A, whereas temperature, DO, and cyanobacterial abundance appear to be key structural determinants of the gut microbiota at Locations B and C in this reservoir system. In the present study, water and fish gut samples were collected only during a single season, thereby limiting the analysis to preliminary associations between water quality parameters, aquatic environmental microbiota, and the assembly of fish gut microbiota. In future research, we will conduct sampling across multiple seasons to dynamically analyze the influence of water quality parameters on the formation of microbial communities in both aquatic environments and fish guts.

5. Conclusions

The water quality parameters exhibited considerable variation across the three sampling sites, which in turn influenced the microbiota communities in both the aquatic environment and fish guts. At the genus level, significant differences were observed in the aquatic environmental microbiota and in the gut microbiota of the same fish species among the three sampling sites. RDA revealed that pH, conductivity, and TDS likely serves as a primary environmental driver at Location A, whereas temperature, DO, and cyanobacterial abundance act as key determinants of gut microbiota structure at Locations B and C. Conducted in the Yi’an Reservoir, the present study reveals significant associations between water quality parameters, aquatic environmental microbiota, and the assembly of fish gut microbial communities, providing valuable insights for the conservation of reservoir water resources and fish populations.

Author Contributions

J.W.: Conceptualization, software, writing—review and editing; T.L. (Tienan Li): writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition; P.Q.: data curation, formal analysis; N.Z.: investigation, validation; W.G.: formal analysis, resources; S.L.: software, data curation; T.L. (Tingyu Li): data curation, resources; J.C.: formal analysis, software. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from Technical research on source tracing and evaluation of pollutants in small water bodies (CZKYF2023-1-B038).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Permissions for the experiments involved in the present study were obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Ethics Committee of the Heilongjiang Province Hydraulic Research Institute (Harbin, Heilongjiang, China) (Authorization NO.20250821002, 21 August 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data of the present study have been submitted to NCBI with the accession numbers PRJNA1395804. All other data are contained within the main manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shen, M.; Li, Q.; Ren, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Li, T.; Zhao, J. Trophic status is associated with community structure and metabolic potential of planktonic microbiota in plateau lakes. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tee, H.S.; Waite, D.; Lear, G.; Handley, K.M. Microbial river-to-sea continuum: Gradients in benthic and planktonic diversity, osmoregulation and nutrient cycling. Microbiome 2021, 9, 190. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Luo, J.; Xu, Y.J.; Zhang, L.; Ye, C. Hydrological seasonality and nutrient stoichiometry control dissolved organic matter characterization in a headwater stream. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solange, D. The microbial phosphorus cycle in aquatic ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 4, 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, S.; Rout, A.K.; Ghosh, K.; Jana, A.K.; Behera, B.K. Microbial Ecology in Microplastics: Impact on Aquatic Ecosystems and Bioremediation. In Current Trends in Fisheries Biotechnology; Behera, B.K., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, W.; He, C.; Honaker, C.F.; Zhai, Z.; Sun, Z.; Siegel, P.B. Body weight selection affects quantitative genetic correlated responses in gut microbiota. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blekhman, R.; Goodrich, J.K.; Huang, K.; Sun, Q.; Bukowski, R.; Bell, J.T.; Spector, T.D.; Keinan, A.; Ley, R.E.; Gevers, D.; et al. Host genetic variation impacts microbiome composition across human body sites. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, T.D.; Pao, Y.Y.; Chen, P.; Weng, F.C.H.; Jean, W.D.; Wang, D. Effects of host phylogeny and habitats on gut microbiomes of oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.C.R.; Snowberg, L.K.; Gregory Caporaso, J.; Knight, R.; Bolnick, D.I. Dietary input of microbes and host genetic variation shape among-population differences in stickleback gut microbiota. ISME J. 2015, 9, 2515–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauers, L.A.; Sadd, B.M. An interaction between host and microbe genotypes determines colonization success of a key bumble bee gut microbiota member. Evolution 2019, 73, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Bian, B.; Teng, L.; Nelson, C.D.; Driver, J.; Elzo, M.A.; Jeong, K.C. Host genetic effects upon the early gut microbiota in a bovine model with graduated spectrum of genetic variation. ISME J. 2020, 14, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanglard, L.P.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Gray, K.A.; Linhares, D.C.L.; Yeoman, C.J.; Dekkers, J.C.M.; Niederwerder, M.C.; Serão, N.V.L. Investigating the relationship between vaginal microbiota and host genetics and their impact on immune response and farrowing traits in commercial gilts. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2020, 137, 84–102. [Google Scholar]

- Woznica, A.; Cantley, A.M.; Beemelmanns, C.; Freinkman, E.; Clardy, J.; King, N. Bacterial lipids activate, synergize, and inhibit a developmental switch in choanoflagellates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7894–7899. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wang, B.H.; Zhang, M.H.; Rantalainen, M.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhou, H.K.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.; Pang, X.; Zhang, M.; et al. Symbiotic gut microbes modulate human metabolic phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2117–2122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.; Li, J.V.; Marchesi, J.R.; Nicholson, J.K. Gut microbiota composition and activity in relation to host metabolic phenotype and disease risk. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Holmes, E.; Kinross, J.; Burcelin, R.; Gibson, G.; Jia, W.; Pettersson, S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science 2012, 336, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimpin, L.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Negro, F.; Corbould, E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Webber, L.; Sheron, N. Burden of liver disease in Europe: Epidemiology and analysis of risk factors to identify prevention policies. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laterza, L.; Rizzatti, G.; Gaetani, E.; Chiusolo, P.; Gasbarrini, A. The gut microbiota and immune system relationship in human graft-versus-host disease. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, e2016025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auchtung, T.A.; Fofanova, T.Y.; Stewart, C.J.; Nash, A.K.; Wong, M.C.; Gesell, J.R.; Auchtung, J.M.; Ajami, N.J.; Petrosino, J.F. Investigating colonization of the healthy adult gastrointestinal tract by fungi. mSphere 2018, 3, e00092-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, Y.; Feng, W.; Yan, Q.; Gong, Y. Host species as a strong determinant of the intestinal microbiota of fish larvae. J. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Gooneratne, R.; Lai, R.; Zeng, C.; Zhan, F.; Wang, W. The gut microbiome and degradation enzyme activity of wild freshwater fishes influenced by their trophic levels. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, J.L.; Moustafa, M.A.M.; Mohamed, W.M.A.; Hayakawa, T.; Nakao, R.; Koizumi, I. Comparing the gut microbiome along the gastrointestinal tract of three sympatric species of wild rodents. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S.; Gu, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Lyu, K.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z. Changes in the life history traits of Daphnia magna are associated with the gut microbiota composition shaped by diet and antibiotics. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lai, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, E.; Mai, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, H. Connection between the Gut Microbiota of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) and microbiota of the pond culture environment. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Yao, B.; Romero, J.; Waines, P.; Ringø, E.; Emery, M.; Liles, M.R.; Merrifield, D.L. Methodological approaches used to assess fish gastrointestinal communities. In Aquaculture Nutrition: Gut Health, Probiotics and Prebiotics; Merrifield, D., Ringø, E., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Eiler, A.; Bertilsson, S. Composition of freshwater bacterial communities associated with cyanobacterial blooms in four Swedish lakes. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M.; Kojima, H.; Iwata, T.; Urabe, J.; Fukui, M. Dissolved organic carbon as major environmental factor affecting bacterioplankton communities in mountain lakes of eastern Japan. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, J.; Suzuki, M.T.; Wang, K.; Evans, S.E.; Chen, F. High temporal but low spatial heterogeneity of bacterioplankton in the Chesapeake Bay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 6776–6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massana, R.; Murray, A.E.; Preston, C.M.; DeLong, E.F. Vertical distribution and phylogenetic characterization of marine planktonic Archaea in the Santa Barbara Channel. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, L.; Das, B.C.; Patri, M. Microbial communities modulating brain functioning and behaviors in zebrafish: A mechanistic approach. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 145, 104251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, G.; Zhu, L. Research progress of the gut microbiome in hybrid fish. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Amberg, J.; Chapman, D.; Gaikowski, M.; Liu, W.T. Fish gut microbiota analysis differentiates physiology and behavior of invasive Asian carp and indigenous American fish. ISME J. 2014, 8, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringø, E.; Zhou, Z.; Olsen, R.E.; Song, S.K. Use of chitin and krill in aquaculture-the effect on gut microbiota and the immune system: A review. Aquac. Nutr. 2012, 18, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogtmann, E.; Hua, X.; Zeller, G.; Sunagawa, S.; Voigt, A.Y.; Hercog, R.; Goedert, J.J.; Shi, J.; Bork, P.; Sinha, R. Colorectal cancer and the human gut microbiome: Reproducibility with whole-genome shotgun sequencing. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudadio, I.; Fulci, V.; Palone, F.; Stronati, L.; Cucchiara, S.; Carissimi, C. Quantitative assessment of shotgun metagenomics and 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing in the study of human gut microbiome. OMICS 2018, 22, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, B. Flood Regulation and disaster mitigation measures for the Shuangyang River Reservoir. Heilongjiang Sci. Technol. Water Cons. 2006, 5, 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Tian, J.; Jiang, X.; Li, C.; Ge, Y.; Hu, X.; Cheng, L.; Shi, X.; Shi, L.; Jia, Z. Effects of different dietary protein levels on the growth performance, physicochemical indexes, quality, and molecular expression of Yellow River carp (Cyprinus carpio haematopterus). Animals 2023, 13, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.J.; Zhang, C.; Lu, L.F.; Cui, B.J.; Li, X.Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, S.; Gui, J.F. Autophagic degradation of MAVS-B by Carassius auratus herpesvirus (CaHV) ORF56 suppresses interferon response in polyploid gibel carp. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2026, 168, 111012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhong, Z.; Dai, W.; Fan, Q.; He, S. Phylogeographic structure, cryptic speciation and demographic history of the sharp belly (Hemiculter leucisculus), a freshwater habitat generalist from southern China. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 216. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Li, L.; Lu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, Y.; Wu, D. Identification of the regulatory roles of water qualities on the spatio-temporal dynamics of microbiota communities in the water and fish guts in the Heilongjiang River. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1435360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, N.; Beaumier, D.; Lee, K.; Greer, C.W. Soil washing improves the recovery of total community DNA from polluted and high organic content sediments. J. Microbiol. Methods 2004, 56, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jing, X.; Ma, Z.Y.; He, J.S. A review on the measurement of ecosystem multifunctionality. Biodivers. Sci. 2016, 24, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoc, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cole, J.R.; Rosen, G.L. Using the RDP classifier to predict taxonomic novelty and reduce the search space for finding novel organisms. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Yao, M. Microeco: An R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiaa255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Wagner, H. Vegan: Community Ecology Package; R Package Version 2.0-10; R Project: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ciglenečki, I.; Janeković, I.; Marguš, M.; Bura-Nakić, E.; Carić, M.; Ljubešić, Z.; Batistić, M.; Hrustić, E.; Dupčić, I.; Garić, R. Impacts of extreme weather events on highly eutrophic marine ecosystem (Rogoznica Lake, Adriatic coast). Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 108, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjevac, P.; Korlevic, M.; Berg, J.S.; Bura-Nakić, E.; Ciglenečki, I.; Amann, R.; Orlic, S. Community shift from phototrophic to chemotrophic sulfide oxidation following anoxic holomixis in a stratified seawater lake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Shi, W.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X.; Tan, Z.; Xie, E.; Zhang, D. Impacts of organophosphate pesticide types and concentrations on aquatic bacterial communities and carbon cycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 475, 134824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xv, K.Z.; Zhang, S.; Pang, A.; Wang, T.T.; Dong, S.H.; Xv, Z.K.; Zhang, X.; Liang, J.; Fang, Y.; Tan, B.; et al. White feces syndrome is closely related with hypoimmunity and dysbiosis in Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 38, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, J.; Kopecký, J.; Cepák, V. Generic characters of the simplest cyanoprokaryotes Cyanobium, Cyanobacterium and Synechococcus. Cryptogam. Algol. 1999, 20, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatsis, C.; Sipkema, D.; Smidt, H.; Heilig, H.; Benvenuti, G.; Verreth, J.; Verdegem, M. The impact of rearing environment on the development of gut microbiota in tilapia larvae. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestrum, R.I.; Attramadal, K.J.K.; Winge, P.; Li, K.; Olsen, Y.; Bones, A.M.; Vadstein, O.; Bakke, I. Rearing water treatment induces microbial selection influencing the microbiota and pathogen associated transcripts of cod (Gadus morhua) larvae. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, M.S.; Vadstein, O.; De Schryver, P.; Attramadal, K.J.K. Aquaculture rearing systems induce no legacy effects in Atlantic cod larvae or their rearing water bacterial communities. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jampani, M.; Mateo-Sagasta, J.; Chandrasekar, A.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Graham, D.W.; Gothwal, R.; Moodley, A.; Chadag, V.M.; Wiberg, D.; Langan, S. Fate and transport modelling for evaluating antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments: Current knowledge and research priorities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazzon, M.C.; Ghosh, K.; Ringø, E.; Kokou, F. Chapter 17—The importance of gut microbes for nutrition and health. In Feed and Feeding for Fish and Shellfish; Kumar, V., Ed.; ScienceDirect: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 575–637. [Google Scholar]

- Vadstein, O.; Attramadal, K.J.K.; Bakke, I.; Olsen, Y. K-selection as microbial community management strategy: A method for improved viability of larvae in aquaculture. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Lu, J. Effects of land use, topography and socio-economic factors on river water quality in a mountainous watershed with intensive agricultural production in East China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hou, Z.; Liao, J.; Fu, L.; Peng, Q. Influences of the land use pattern on water quality in low-order streams of the Dongjiang River basin, China: A multi-scale analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 551–552, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, H.Y.; Chuah, C.J.; Yong, E.L.; Snyder, S.A. Effects of land use configuration, seasonality and point source on water quality in a tropical watershed: A case study of the Johor River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, S.L.; Zhong, J.; Li, C. Spatial scale effects of the variable relationships between landscape pattern and water quality: Example from an agricultural karst river basin, Southwestern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 300, 106999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lu, J. Spatial scale effects of landscape metrics on stream water quality and their seasonal changes. Water Res. 2021, 191, 116811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.