Abstract

The endangered freshwater fish Gobiobotia brevibarba is endemic to Korea and threatened by habitat disturbance in major river systems. We investigated four wild populations from the Han River basin (IJR, BHR, NHR) and the Geum River basin (GR) using eleven microsatellite loci to assess genetic diversity, population structure, and contemporary gene flow. All populations showed relatively high genetic diversity (HO = 0.709–0.800, HE = 0.707–0.803) and no evidence of inbreeding, although bottleneck signals under the infinite allele mutation model were detected in IJR and BHR. Contemporary effective population size was large in IJR (Ne = 2463) and moderate in NHR (Ne = 467), whereas estimates for BHR and GR were imprecise. Genetic differentiation was very low within the Han River basin (FST = 0.009–0.027) but weak and significant between Han and Geum (FST = 0.085–0.096), and clustering analyses (STRUCTURE, DAPC, find.cluster) consistently supported K = 2, separating Han from Geum River. Gene flow analyses indicated extremely limited interbasin gene flow (<4%) but asymmetric contemporary migration from BHR into both IJR and NHR; all other migration rates were similarly low. These results show that G. brevibarba currently maintains high genetic diversity and two basin-level genetic clusters, underscoring the need to manage Han and Geum River populations as separate units and conserve riffle habitats and longitudinal connectivity.

Key Contribution:

We identified significant genetic differentiation between Han and Geum River populations of Gobiobotia brevibarba, supporting the designation of separate management units (MUs) for conservation strategies. The findings underscore the need to avoid cross-basin translocations and to conserve riffle habitats and gene flow pathways within river systems.

1. Introduction

Across Korea, many freshwater fishes have become threatened or endangered as a result of rapid habitat loss, channelization, and water quality degradation [1,2,3,4,5]. Indeed, the construction of large-scale hydraulic structures such as dams and weirs has transformed lotic reaches into impounded, slow-flowing environments, leading to the loss or fragmentation of riffle habitats [3,6,7,8]. These changes can reduce habitat availability for rheophilic species, disrupt longitudinal connectivity, and impede upstream–downstream movements that are critical for completing life cycles [3,9]. Gobiobotia brevibarba is a small, riffle-dwelling cyprinid endemic to the Korean Peninsula and is currently listed as an endangered freshwater fish species [10,11]. This species is restricted to two major river systems in Korea, the Han River basin and the Geum River basin, where it occupies shallow (20–80 cm), fast-flowing reaches (0.50–1.50 m/s) with coarse substrates primarily composed of cobble and pebble [10,11,12]. Such riffle habitats provide high dissolved oxygen (typically >8.5 mg L−1), specific flow regimes, and heterogeneous microhabitats that are essential for feeding [10,11], spawning in May with the production of adhesive and demersal eggs, and early life stages [11]. Because G. brevibarba is tightly associated with strong currents and shallow riffles, it is particularly sensitive to alterations in flow and channel morphology [10]. For G. brevibarba, the conversion of riffles into pools and reservoirs can directly reduce suitable spawning and feeding areas and increase exposure to lentic predators and competitors [6,10]. Long-term habitat disturbance is therefore expected to drive local population declines and increase extinction risk, even when demographic and genetic indicators appear stable in the short term [13,14,15]. Against this broader backdrop of widespread endangerment in Korean freshwater fishes, understanding how habitat alteration affects the ecology and persistence of riffle specialists such as G. brevibarba has become a key priority for conservation and river management [4].

In conservation biology, genetic diversity is widely recognized as a fundamental component of population viability, and numerous studies on freshwater fishes have quantified allelic richness and heterozygosity to assess the status of wild populations [1,16,17,18,19]. For endangered species, measures such as the number of alleles, observed heterozygosity (HO), and expected heterozygosity (HE) provide essential baseline information that can be used to evaluate the impact of habitat disturbance, overexploitation, and restocking programs [1,2,3,4]. High genetic diversity is generally associated with a greater capacity to adapt to environmental change, resist emerging diseases, and recover from demographic fluctuations, whereas reduced diversity can limit evolutionary potential and increase extinction risk [16]. Importantly, genetic diversity is closely linked to effective population size (Ne), which reflects the number of breeding individuals that contribute genes to the next generation and is often much smaller than census population size [16]. Because Ne determines the rates of genetic drift and inbreeding, it is a key parameter for predicting how quickly genetic variation will be lost in small or fragmented populations [16,20]. Conservation guidelines therefore emphasize minimum Ne thresholds for avoiding short-term inbreeding depression and for maintaining long-term adaptive potential, and recent work has argued that endangered populations should ideally achieve Ne values in the hundreds to thousands of individuals [1,3,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. In freshwater fishes with restricted ranges and fragmented habitats, Ne can be substantially reduced by barriers to dispersal, episodic recruitment failure, and skewed reproductive success [1,3,4,19]. Monitoring both genetic diversity and Ne in endangered fishes such as G. brevibarba is thus essential for identifying hidden genetic erosion that may not yet be apparent from census counts alone [1,4]. Such information can inform decisions about habitat restoration, harvest control, and potential supplementation or reintroduction programs [23]. Ultimately, integrating estimates of genetic diversity and effective population size into management planning provides a quantitative basis for setting conservation targets and evaluating whether existing populations are demographically and genetically robust enough to persist under ongoing environmental change [23,24,25].

Genetic diversity, the spatial pattern of genetic variation and population genetic structure play crucial roles in the conservation of endangered freshwater fishes [14]. Genetic structure reflects historical and contemporary processes such as dispersal, gene flow, drift, and local adaptation, and its characterization allows the identification of evolutionarily or demographically distinct population units [26]. In a conservation framework, such units are often formalized as management units (MUs), which guide how populations should be monitored, managed, and, when necessary, restored [13,26,27]. For endangered fishes confined to multiple river basins or tributaries, delineating MUs based on genetic structure is particularly important because it can reveal cryptic differentiation among populations that are geographically close but demographically independent [27]. If genetically distinct populations are managed as a single unit, translocations or stocking programs may inadvertently mix locally adapted gene pools, leading to outbreeding depression or genetic homogenization [28]. Conversely, recognizing distinct MUs enables managers to prioritize the protection of unique genetic lineages and avoid cross-basin or cross-tributary movements that could erode local adaptation [29]. Analyses of gene flow and migration rates provide an additional layer of information by indicating whether populations are functionally connected or effectively isolated [30]. In restoration contexts, estimates of contemporary gene flow can identify potential source populations for recolonization, reveal barriers that disrupt connectivity, and evaluate the effectiveness of fishways or other mitigation structures at dams and weirs [3,31].

In this study of the endangered river-dwelling species G. brevibarba, we provide essential data to (i) compare genetic diversity across populations and estimate effective population sizes, (ii) understand how populations are structured within and between the Han and Geum River basins and how gene flow is mediated through natural pathways and anthropogenic barriers, and (iii) inform habitat restoration or reintroduction efforts by proposing appropriate management units (MUs).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Genomic DNA Extraction

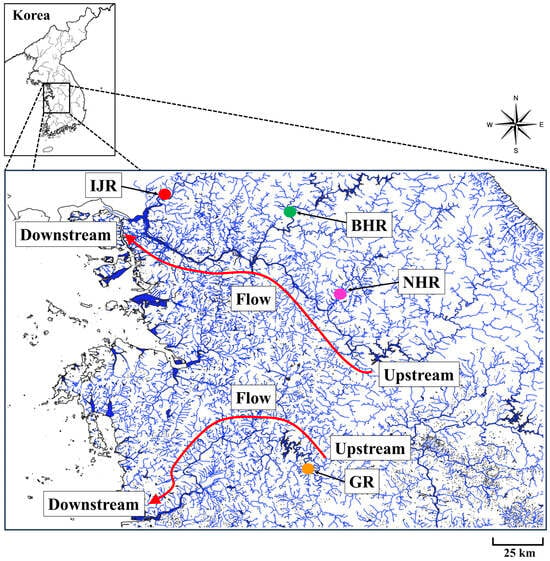

Gobiobotia brevibarba is an endangered freshwater fish species in Korea that is distributed in the Geum, Imjin, Bukhan, and Namhan Rivers (Figure 1). Specimen collection was conducted under animal ethics approval issued by the Ministry of Environment (Geum River Basin Environmental Office: permit no. 2010-03; Wonju regional Environmental Office: permit no. 2010-07; Han Drainage Basin Area Environment Office: permit no. 2010-09). Detailed sampling localities of G. brevibarba in the Geum, Imjin, Bukhan, and Namhan Rivers are provided in Table S1. The collection of this species was conducted in March and April of 2010, with 30 specimens collected at each site by sampling upstream and downstream of GPS points established in the field. This process involved sampling at least three riffles at each site. Due to its designation as an endangered species under Republic of Korea law, the total number of individuals collected was strictly limited to a maximum of 30 specimens per site. This species exhibits a specific microhabitat preference, exclusively inhabiting riffles, and this preference was used to target collection efforts. The specimens were collected directly using a seine net (mesh size: 4 × 4 mm). Only adults with a total length of 10 cm or greater were selected and retained following confirmation of their size in the field. The pelvic fin was selected because partial fin clipping is a minimally invasive and commonly used sampling method in teleost fishes, reflecting the strong regenerative capacity of fin tissues and their negligible long-term effects on survival, growth, and behavior [32,33,34]. The preserved tissues were subsequently incubated in TNES-urea buffer containing 8 M urea, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 125 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS for genomic DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted following the protocol of Asahida et al. [35]. The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA were assessed spectrophotometrically using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Figure 1.

Sampling sites for G. brevibarba in the Geum, Imjin, Bukhan, and Namhan River. Groups codes are defined in Table S1, and the initial numeral in each code denotes the year of sampling. IJR, Imjin River; BHR, Bukhan River; NHR, Namhan River; GR, Geum River. The arrows on the red line indicate flow from upstream to downstream.

2.2. Microsatellite Genotyping

Eleven primers developed exclusively for this species were selected (Table S2) and used in this study [2]. Each PCR reaction contained approximately 10 ng of genomic DNA, 0.5 U of Ex Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan), 1× Ex Taq buffer, 200 µM of each dNTP (2.5 mM stock), 0.4 μM of the forward primer, 0.8 μM of the reverse primer, and 0.4 μM of a fluorescently labeled M13 primer, in a total volume of 20 μL. The M13 primer sequence (TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT) was labeled with one of four fluorescent dyes (FAM, HEX, NED, or PET). PCR amplification followed a modified Schuelke protocol [36]: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56–58 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; followed by an additional 8 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min before holding at 4 °C. Amplification success and approximate fragment size were checked on 2% agarose gels. For fragment analysis, microsatellite PCR products were mixed with GeneScan™ 500 ROX size standard (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and HiDi™ formamide (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), denatured at 95 °C for 2 min, and then snap-cooled at 4 °C. Allele lengths were determined on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and genotypes were scored using GeneMarker® v2.6.7 (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, USA). The microsatellite markers were deposited in GenBank (JX179136–JX179146).

2.3. Microsatellite-Based Genetic Diversity Analyses

Genotyping quality at microsatellite loci was first evaluated with MICRO-CHECKER v2.2.3 [37] to detect potential scoring artifacts such as null alleles, large-allele dropout, or stutter-related errors. The effect of null alleles on genetic differentiation was further evaluated using the ENA correction implemented in FreeNA following the method of Chapuis and Estoup, 2007 [38]. Standard measures of genetic diversity, including the number of alleles per locus (NA), observed heterozygosity (HO), and expected heterozygosity (HE), were then calculated in CERVUS v3.0 [39]. Departures from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and population inbreeding coefficients (FIS) were assessed using GENEPOP v.1.2 [40] in conjunction with ARLEQUIN v3.5 [41].

Signals of recent reductions in effective population size were investigated with BOTTLENECK v1.2.02 [42], applying heterozygosity-excess tests under the infinite alleles model (IAM) [43], the stepwise mutation model (SMM), and a two-phase mutation model (TPM) that incorporated 95% SMM and 15% multistep changes [44]. For each mutation model, 10,000 simulation iterations were run, and statistical significance of heterozygosity excess was evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [45]. To infer recent demographic bottlenecks, we calculated the M-ratio for each microsatellite locus following Garza and Williamson, 2001 [46]. Contemporary effective population size (Ne) was estimated from linkage disequilibrium using LDNe [47].

2.4. Population Genetic Structure and Gene Flow Analysis

Pairwise genetic differentiation (FST) and analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) among populations were estimated for microsatellite data using ARLEQUIN v3.5 [41]. Bayesian clustering of multi-locus microsatellite genotypes was conducted in STRUCTURE v2.3 [48] to infer the most likely number of genetically homogeneous clusters (K) across individuals. Values of K from 1 to 10 were tested, with 10 independent runs per K. Each run consisted of a burn-in phase of 50,000 MCMC iterations followed by 100,000 additional iterations, assuming an admixture model appropriate for potentially interconnected water systems. The optimal K was identified following the ΔK approach of Evanno et al. [49] implemented in STRUCTURE SELECTOR [50]. To further explore and visualize genetic structuring, discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC) was performed on the microsatellite dataset with the R package adegenet v2.1.3 [51], using a genind object as input and retaining 40–60 principal components and three discriminant functions for four genetic clusters. Microsatellite genotypes in GenAlEx format were imported as a genind object (poppr), genetic distance matrices were computed (adegenet), and principal coordinates analysis (PCoA; ape) was performed to visualize the first three axes (PCo1–PCo3) in three dimensions [51]. Contemporary migration rates (gene flow) among the four groups were estimated with the Bayesian assignment method implemented in BA3, an extension of BayesAss [52], under the default parameter settings.

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity

MICRO-CHECKER detected evidence of null alleles at a single locus (GB258), and this signal was confined to the NHR group. No stuttering or large-allele dropout was detected at any locus. ENA correction showed that global and pairwise FST values were nearly identical before and after correction (global FST = 0.05498 vs. 0.05424; Δ FST < 0.002), indicating that null alleles had negligible effects on estimates of population differentiation. Therefore, all loci, including GB258, were retained for downstream analyses. Genetic diversity was assessed across the four groups (Table 1). The mean number of alleles ranged from 9.8 to 13.0, the HO ranged from 0.709 to 0.800, the HE ranged from 0.707 to 0.803, and the AR (n = 29) ranged from 9.7 to 12.9. Genetic diversity (HE) was highest in BHR and lowest in GR. Deviation from HWE was detected only in NHR, whereas the remaining groups conformed to HWE. FIS was highest in NHR and lowest in GR, but there were no significant differences.

Table 1.

Microsatellite-based genetic diversity summary of G. brevibarba.

The bottleneck inference results showed that bottlenecks existed in IJR and BHR under the IAM (Table 2). No evidence of bottlenecks was found in the remaining two populations. The mean M-ratio differed slightly among populations. The Geum River population showed the lowest mean M-ratio (M = 0.72), followed by the Imjin River (M = 0.78), Namhan River (M = 0.79), and Bukhan River populations (M = 0.83). No population exhibited a mean M-ratio clearly lower than the empirical threshold value (M ≈ 0.68) proposed for detecting recent bottlenecks. The effective population size estimation results were 2463 for IJR and 467 for NHR, while the remaining groups, BHR and GR, could not be estimated.

Table 2.

Inference of bottlenecks and effective population sizes for four groups of G. brevibarba.

3.2. Population Genetic Structure

There was little genetic differentiation (FST value) between IJR, BHR, and NHR (0.027–0.009, p < 0.05), while there was a weak but significant differentiation between IJR, BHR, and NHR vs. GR (0.085–0.096, p < 0.05, Table 3).

Table 3.

FST among four groups of G. brevibarba according to the eleven microsatellite loci datasets.

The AMOVA test results showed a difference of 6.61% between IJR, BHR, NHR vs. GR, and there was little difference between populations within the IJR, BHR, and NHR groups at 2.03% (Table 4). Among groups, variance was modest (6.61%) but highly significant (p < 0.001) and exceeded the within-basin component (2.03%), indicating that basin-level differentiation between the Han and Geum Rivers is stronger than fine-scale divergence within the Han River system. These results were consistent with a hierarchical structure in which the drainage basin constitutes the primary axis of genetic differentiation.

Table 4.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) summary statistics for four groups of G. brevibarba.

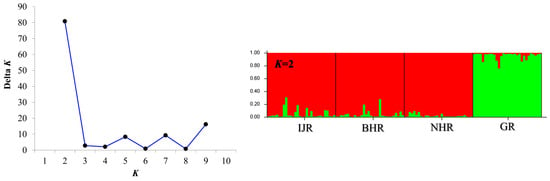

The genetic structure of the population was clearly evident at K = 2 (Figure 2), with the highest delta K value. Therefore, the whole dataset was divided into two groups, one represented by IJR, BHR, and NHR sampling sites and the other represented by GR group. Although delta K values exceeded 10 at K = 9, the difference was not significant, and the bar graph showed results similar to those at K = 2. The DAPC scatterplot results showed that IJR, BHR, and NHR were grouped together, while GR was separated (Figure 3). 3D PCoA analysis also showed that IJR, NHR, and BHR were clustered together, and separated from GR (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Population structure of G. brevibarba inferred using STRUCTURE. (Left) Evanno’s ΔK across K = 1–10, showing a pronounced peak at K = 2. (Right) STRUCTURE bar plots for K = 2 under the admixture model (10 replicate runs per K; burn-in = 50,000; MCMC = 100,000). Each vertical bar represents an individual, colored segments indicate membership coefficients (q) for the inferred clusters, and individuals are grouped by sampling locality (IJR = Imjin River, BHR = Bukhan River, NHR = Namhan River, GR = Geum River). In the STRUCTURE bar plot (K = 2), each vertical bar represents an individual and the red and green colors indicate the estimated membership proportions (Q-values) in the two inferred genetic clusters. In line with the ΔK peak, the bar plots reveal a clear subdivision into two groups across localities. The strongest support at K = 2 indicates that a single population is genetically divided into two distinct groups.

Figure 3.

A scatterplot of discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC). Groups labels are abbreviated. Each sample site has its own color and symbol for each point. The right panel displays the retained principal components and discriminant functions used in the analysis. Each point in the scatterplot represents a single individual, and the spatially coherent point clouds represent two genetically distinct clusters. IJR, Imjin River; BHR, Bukhan River; NHR, Namhan River; GR, Geum River. PCA eigenvalues: Inset shows the proportion of variance explained by the retained (black) versus discarded (grey) PCA components used as input to DAPC. DA eigenvalues: Inset shows the eigenvalues of the discriminant analysis axes retained in DAPC, reflecting their relative discriminating power (black = retained; grey = not retained/remaining).

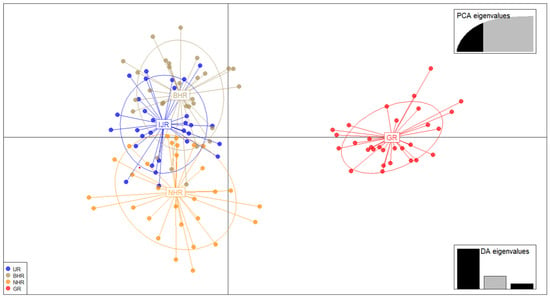

Clustering analysis using the find.cluster function in adegenet with 80 principal components showed that Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) decreased from K = 1 to K = 2 and then increased monotonically for larger K (Figure 4). The global minimum BIC occurred at K = 2, indicating that a model with two genetic clusters provides the best balance between goodness of fit and model complexity for these data.

Figure 4.

Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values for different numbers of clusters (K) obtained with the find.cluster function in adegenet, using 80 principal components. The BIC reaches its minimum at K = 2 and increases thereafter, indicating that two genetic clusters provide the best-supported partition of the G. brevibarba samples.

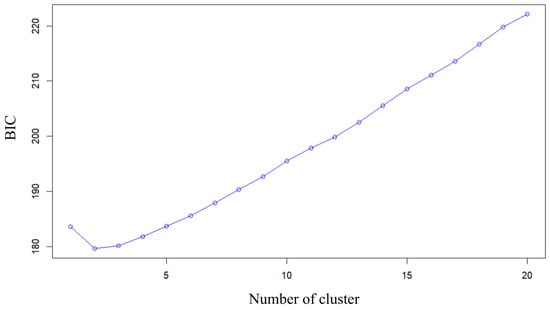

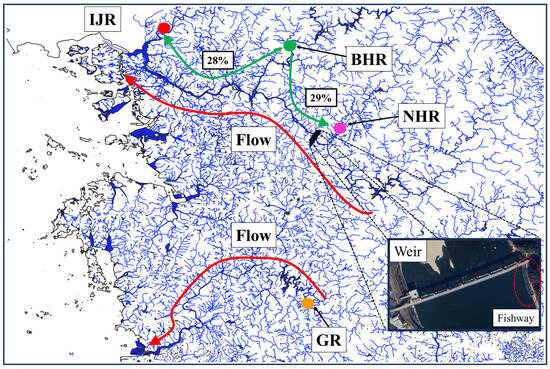

BA3 analysis revealed asymmetric contemporary gene flow concentrated in the northern part of the range, with high migration from BHR into both IJR and NHR (posterior mean migration rates: 28–29%) (Figure 5, Table S3). In contrast, all other pairwise migration rates among rivers were <4% and were therefore not depicted.

Figure 5.

Gene flow among the four G. brevibarba groups inferred using BA3. Circles indicate sampling localities and arrows depict the main migration pathways: green arrows show high recent gene flow from BHR to IJR (28%) and from BHR to NHR (29%), and red arrows illustrate downstream and upstream movement along the river network. The black trapezoidal symbols indicate weirs, and the enlarged images show the weirs, while the dotted circular symbols denote fishways. IJR, Imjin River; BHR, Bukhan River; NHR, Namhan River; GR, Geum River.

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Diversity

Genetic diversity is typically evaluated by the number of alleles and heterozygosity indices (HE and HO) across many species, including freshwater fish [1,4,17,18,21]. The endangered fish of the same genus (Gobiobotia) showed HO = 0.718 and HE = 0.827, which were relatively high compared to the present study (HO = 0.709–0.800, HE = 0.707–0.803) [4]. Genetic diversity continues to decline along with population decline when a species is caught in an extinction vortex [16]. For genetic diversity, if HE is 0.7 or higher, it is reported as high genetic diversity [19,53]. High genetic diversity is linked to strong adaptive potential, though genetic diversity loss following rapid habitat loss typically occurs over a longer timescale [3]. The rivers within the study area have experienced frequent habitat disturbance due to the construction of dams and weirs [6,54,55,56]. G. brevibarba, a species native to areas with strong currents and microhabitats, is particularly vulnerable to the construction of weirs and dams that destroy these currents [10,11,56]. Although the endangered fish in this study did not show low genetic diversity, the current threat of microhabitat disturbance, such as dams and reservoirs, may lead to a long-term trend of decreasing genetic diversity [3]. Inbreeding also causes population declines in endangered fish species, but the current study found no evidence of inbreeding.

Bottleneck tests under the IAM suggested historical demographic contractions in the IJR and BHR groups, whereas no bottleneck signals were detected under the SMM or TPM, which are considered more appropriate mutation models for microsatellite loci [57,58]. Because the IAM assumes that each mutation produces a novel allele, it is known to be overly sensitive to recent reductions in allele number and can therefore produce false positives when applied to microsatellite data [44,59]. In contrast, the allele frequency distributions in both populations exhibited an L-shaped pattern, which is characteristic of populations at mutation–drift equilibrium or those that have recovered from a bottleneck [44,45]. In addition, no population showed a mean M-ratio below the empirical threshold value for detecting recent bottlenecks (M ≈ 0.68) [46], further supporting the absence of a strong and ongoing demographic contraction.

Given that major dams in the IJR and BHR systems were constructed mainly in the early to mid-2000s, and that genetic diversity metrics such as heterozygosity and allele number typically respond to demographic changes with a temporal lag of several generations, the detected signals are more consistent with historical rather than recent bottleneck events [60,61]. Taken together, these results indicate post-disturbance demographic recovery and current population stability rather than a recent bottleneck [42].

Furthermore, the size of Ne was estimated at 2463 for IJR, which exceeds 1000, suggesting that the current state is likely to facilitate long-term population maintenance in the absence of external disturbance [20]. Ne for NHR was also greater than 100, suggesting that, although not as long-term as for IJR, it is suitable for short-term population maintenance [20]. In contrast, Ne could not be reliably estimated for the BHR and GR populations using the linkage disequilibrium method, likely due to weak linkage disequilibrium associated with large effective population sizes rather than a true biological absence of reproductive potential [47,62,63]. Therefore, the absence of Ne estimates reflects a known methodological limitation of the LD-based approach in large populations and does not constitute evidence of low population viability.

As noted above, high genetic diversity and a large Ne do not necessarily imply a low risk of extinction, because genetic indices often lag behind demographic declines [20,60]. In freshwater fishes, disturbances to microhabitats can rapidly trigger population declines and drive populations into an extinction vortex, thereby necessitating careful and continued genetic monitoring [3].

4.2. Population Structure

We investigated genetic differentiation in G. brevibarba by comparing three groups within the Han River basin (IJR, NHR, BHR) and one genetic population from the Geum River basin (GR). Within the same basin, pairwise FST values were very low (<0.027) but statistically significant (p < 0.05), which is consistent with substantial gene flow driven by the movement of freshwater fishes within a shared drainage system [19,64]. G. brevibarba showed weak but statistically significant genetic differentiation between the Han and Geum River basins. This pattern is consistent with a scenario in which the Han (IJR, NHR, BHR) and Geum Rivers (GRs) were historically connected and experienced gene flow, but later became isolated and diverged, leaving a signature of recent genetic differentiation [65]. STRUCTURE analysis identified K = 2 as the most appropriate number of clusters, indicating that genetic populations from the Han River (IJR, NHR, BHR) are genetically distinct from those in the Geum River. Likewise, the DAPC scatterplots, which provide a model-free assessment of genetic structure, clearly resolve two groups, and the find.cluster function also yields the lowest BIC at K = 2, together providing strong support for a subdivision into two genetic clusters. Genetic differentiation between populations within a species influences the establishment of management units (MUs) [26,29,66]. In particular, when genetic differentiation exists in endangered fish, attention must be paid to preventing genetic contamination between watersheds [26,66]. While genetic exchange within watersheds occurs due to fish migration, differentiation is minimal between watersheds, leading some to argue that genetic differentiation already exists between watersheds, necessitating the conservation of MUs [66]. Therefore, we synthesize the results of FST, STRUCTURE, DAPC, and find.cluster to suggest that the Han River (IJR, NHR, BHR) and the Geum River (GR) should be considered as independent units in conservation strategies.

Management units (MUs) can be delineated based on the genetic differentiation observed among populations in this study; however, there remains a risk of genetic contamination from human-mediated activities. In particular, artificial translocation, cross-basin stocking, and the introduction of non-native or hatchery-reared fishes may facilitate unintended hybridization or introgression, potentially eroding basin-specific genetic structure and local adaptation [17,67,68,69]. The greatest threat of genetic pollution in endangered species is the phenomenon of ‘outbreeding depression’ [70,71]. This occurs because interbreeding between genetically distant populations actually reduces the viability and fertility of offspring, resulting from the breakdown of unique ‘local adaptation’ gene complexes that have evolved to be specialized for each environment [70,71]. When such genetic mixing occurs, ‘genetic homogenization’ proceeds, causing the loss of unique genetic characteristics that each population has preserved [72]. This reduces the overall genetic diversity of the entire species, severely compromising its adaptive potential to respond to new diseases or future climate change [28]. Furthermore, when an endangered species, which already has a small population, interbreeds with genetically incompatible individuals, it results in offspring with low viability, effectively wasting precious reproductive resources [28,73]. The accumulation of such reproductive failures accelerates population collapse, ultimately leading to catastrophic consequences that greatly increase the species’ risk of extinction [73,74].

Because cases of cross-basin stocking have already been reported in Korea among several fish species, and have been indirectly confirmed genetically [17,75], a key difference between those studies and our results is that, whereas hybridization has been genetically documented in species of the genus Coreoleuciscus [75], no evidence of introgression was detected in G. brevibarba in the present study. Instead, our analyses indicate that inter-basin gene flow between the Han and Geum Rivers is currently negligible, despite weak but statistically significant genetic differentiation. This suggests that hybridization has not yet occurred in G. brevibarba but could become a substantial risk if artificial translocation or cross-basin stocking were introduced.

Accordingly, we recommend the following preventive measures: (i) strict prohibition of cross-basin stocking or translocation, (ii) use of locally sourced broodstock only, and (iii) routine genetic screening of hatchery and wild individuals where supplementation is unavoidable. Similar strategies have been widely recommended and successfully applied to reduce genetic risks to wild fish populations [28,71,76].

4.3. Gene Flow

We investigated whether there was contemporary gene flow among populations and found that migration rates between the Han (IJR, BHR, NHR) and Geum River (GR) basins were <4%, indicating that gene flow between basins is highly limited. Within the Han River basin, however, we detected gene flow among IJR, BHR and NHR, which is generally consistent with the expectation that, in the absence of major artificial barriers such as weirs and dams, longitudinal connectivity allows upstream–downstream gene flow in riverine fishes. Nonetheless, population structure analyses consistently grouped IJR, BHR, and NHR into a single genetic cluster, indicating that these sampling sites effectively represent one genetic population. Consistently, pairwise FST values among them were very low (0.009–0.027), indicating only weak genetic differentiation, so any fine-scale interpretation of migration patterns must be treated with caution. Despite their location in the upper Han River basin, virtually no gene flow was detected between the two headwater populations NHR and IJR; instead, asymmetric gene flow was inferred only from BHR into both IJR and NHR. The migration rate between NHR and IJR was extremely low at only 1.0–1.3% (Table S3). Although some topographic connectivity exists between watersheds, the increased distance between sampling sites may have led to restricted movement and, consequently, reduced gene flow. Because G. brevibarba is a riffle-dwelling species that can generally move against fast currents [10], some upstream movement between upper and lower reaches of BHR is expected, and the absence of detectable gene flow between IJR and NHR suggests that dispersal distances may be limited or spatially constrained between those two tributaries. We initially hypothesized that movements into the upper NHR might be restricted by in-stream barriers such as weirs and dams within the Han River system [6], but BA3 nonetheless detected gene flow from BHR to NHR. Field observations confirmed the presence of a fishway adjacent to a weir located approximately 15 km downstream from the NHR sampling site, and this structure likely facilitates upstream movement and maintains longitudinal connectivity. At the same time, the inferred migration patterns should be interpreted as genetic connectivity rather than direct movement rates, because the present study did not include direct field-based measurements of dispersal, habitat quality, or fish passage efficiency. The usefulness of fishways has also been reported in other fish species, and many fish are believed to utilize fishways and maintain longitudinal connectivity [31,77]. Thus, population structure and BA3 analyses indicate that ecological connectivity within the Han River basin is not uniform. Although fish passage structures may facilitate movement in some river sections, gene flow between NHR and IJR appears to be effectively absent, while asymmetric gene flow is restricted to routes involving BHR. Therefore, connectivity within the basin should be interpreted as partial and spatially constrained rather than continuous, and the effectiveness of fishways may be limited to specific reaches rather than promoting basin-wide movement.

5. Conclusions

Our microsatellite-based analysis shows that G. brevibarba retains relatively high genetic diversity and lacks clear signs of inbreeding, despite local bottleneck signals in parts of the Han River basin. Genetic structure is significant between the Han and Geum River basins, and multiple clustering methods consistently support a division into two basin-level genetic groups. Contemporary migration is largely restricted within the Han River, with asymmetric gene flow from BHR to IJR and NHR and virtually no gene flow between basins. These findings support treating Han and Geum populations as separate management units, strictly avoiding cross-basin stocking or translocation, and prioritizing the conservation of riffle habitats and effective fish passage to maintain longitudinal connectivity and long-term evolutionary potential. Microsatellite markers have inherent limitations in detecting fine-scale demographic processes, particularly when the number of loci or samples is limited. Therefore, although the present study provides a robust first assessment of population structure and connectivity, future studies would benefit from incorporating genome-wide approaches such as SNP analyses and long-term genetic monitoring to improve resolution and detect temporal changes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes11010004/s1. Table S1: Sampling sites and number of individuals of G. brevibarba in the study; Table S2: 11 microsatellite loci developed from G. brevibarba; Table S3: Bayesian estimates of posterior mean migration rates among the four populations inferred with BA3; Figure S1: 3D PCoA analysis of microsatellite data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-S.K. and K.-R.K.; methodology, K.-S.K., K.-R.K. and I.-C.B.; software, K.-S.K. and K.-R.K.; validation, K.-S.K. and K.-R.K.; data curation, K.-S.K. and K.-R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.-S.K. and K.-R.K.; writing—review and editing, K.-S.K. and K.-R.K.; supervision, K.-R.K. and K.-S.K.; project administration, I.-C.B.; funding acquisition, I.-C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment (MCEE) of the Republic of Korea through the National Institute of Ecology (NIE) (Grant No. NIE-B-2025-47), and was also supported by Soonchunhyang University (2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the National Institute of Ecology Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol code NIE-IACUC-2020-006 and date of approval: 30 December 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The microsatellite DNA sequence was deposited in GenBank (JX179136–JX179146).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, K.-R.; Kwak, Y.-H.; Sung, M.-S.; Cho, S.-J.; Bang, I.-C. Population structure and genetic diversity of the endangered fish black shinner Pseudopungtungia nigra (Cyprinidae) in Korea: A wild and restoration population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-S.; Lee, H.-R.; Park, S.-Y.; Ko, M.H.; Bang, I.-C. Development and characterization of polymorphic microsatellite marker for an endangered freshwater fish in Korea, Gobiobotia brevibarba. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2014, 6, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.-K.; Kim, K.-R.; Kim, K.-S.; Bang, I.-C. The impact of weir construction in Korea’s Nakdong River on the population genetic variability of the endangered fish species, rapid small gudgeon (Microphysogobio rapidus). Genes 2023, 14, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, J.-Y.; Choi, B.-S.; Hwang, S.-C.; Yang, H. Augmentation and monitoring of an endangered fish, Gobiobotia naktongensis in Naeseongcheon Stream, Korea. Ecol. Resilient Infrastruct. 2015, 2, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.H.; Kim, K.R.; Kim, M.S.; Bang, I.C. Genetic diversity and population structure of the endangered fish Pseudobagrus brevicorpus (Bagridae) using a newly developed 12-microsatellite marker. Genes Genom. 2020, 42, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.U.; Kim, S.K.; Choi, B.; Kim, Y. Impact of hydropeaking on downstream fish habitat at the Goesan Dam in Korea. Ecohydrology 2017, 10, e1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiemann, J.S.; Gillette, D.P.; Wildhaber, M.L.; Edds, D.R. Effects of lowhead dams on riffle-dwelling fishes and macroinvertebrates in a midwestern river. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2004, 133, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Fu, H.; Tan, K.; Ge, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhang, C.; Yan, Y. Role of impoundments created by low-Head dams in affecting fish assemblages in subtropical headwater streams in China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 916873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukuła, K.; Bylak, A. Barrier removal and dynamics of intermittent stream habitat regulate persistence and structure of fish community. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-S.; Byeon, H.-K.; Kwon, O.-K. Reproductive ecology of Gobiobotia brevibarba (Cyprinidae). Korean J. Ichthyol. 2001, 13, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, M.-H.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, I.-R.; Bang, I.-C. Egg development and early life history of the endangered species Gobiobotia brevibarba (Pisces: Cyprinidae). Korean J. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 44, 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D.-S.; Byeon, H.K.; Lee, J.-S. Complete mitochondrial genome of the freshwater gudgeon, Gobiobotia brevibarba (Cypriniformes; Cyprinidae). Mitochondrial DNA 2014, 25, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauer, C.J.; Beheregaray, L.B. Recent and rapid anthropogenic habitat fragmentation increases extinction risk for freshwater biodiversity. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 2857–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, A.; Beheregaray, L.B.; Coleman, R.; Gilligan, D.; Harrisson, K.A.; Ingram, B.A.; Kearns, J.; Lamb, A.M.; Lintermans, M.; Lyon, J. Severe consequences of habitat fragmentation on genetic diversity of an endangered Australian freshwater fish: A call for assisted gene flow. Evol. Appl. 2017, 10, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letcher, B.H.; Nislow, K.H.; Coombs, J.A.; O’Donnell, M.J.; Dubreuil, T.L. Population response to habitat fragmentation in a stream-dwelling brook trout population. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R.; Ballou, J.; Briscoe, D. Conservation Genetics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-R.; Choi, H.-k.; Lee, T.W.; Lee, H.J.; Yu, J.-N. Population structure and genetic diversity of the spotted sleeper Odontobutis interrupta (Odontobutidae), a fish endemic to Korea. Diversity 2023, 15, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-R.; Kim, K.-Y.; Song, H.Y. Genetic structure and diversity of hatchery and wild populations of yellow catfish Tachysurus fulvidraco (Siluriformes: Bagridae) from Korea. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-R.; Sung, M.-S.; Hwang, Y.; Jeong, J.H.; Yu, J.-N. Assessment of the genetic diversity and structure of the Korean endemic freshwater fish Microphysogobio longidorsalis (Gobioninae) using microsatellite markers: A first glance from population genetics. Genes 2024, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R.; Bradshaw, C.J.; Brook, B.W. Genetics in conservation management: Revised recommendations for the 50/500 rules, Red List criteria and population viability analyses. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 170, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-R.; Park, S.Y.; Jeong, J.H.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, H.; Sung, M.-S.; Yu, J.-N. Genetic diversity and population structure of Rhodeus uyekii in the republic of Korea revealed by microsatellite markers from whole genome assembly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-R.; Kim, K.-S.; Yoon, S.J. Genetic Diversity and Structure for Conservation Genetics of Goldeye Rockfish Sebastes thompsoni (Jordan and Hubbs, 1925) in South Korea. Biology 2025, 14, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.K.; Luikart, G.; Waples, R.S. Genetic monitoring as a promising tool for conservation and management. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, M.P.; Nunney, L.; Schwartz, M.K.; Ruzzante, D.E.; Burford, M.; Waples, R.S.; Ruegg, K.; Palstra, F. Understanding and estimating effective population size for practical application in marine species management. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allendorf, F.W.; Luikart, G.H.; Aitken, S.N. Conservation and the Genetics of Populations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Palsbøll, P.J.; Berube, M.; Allendorf, F.W. Identification of management units using population genetic data. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, W.C.; McKay, J.K.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Allendorf, F.W. Harnessing genomics for delineating conservation units. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, F.W.; Leary, R.F.; Spruell, P.; Wenburg, J.K. The problems with hybrids: Setting conservation guidelines. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, C. Defining ‘evolutionarily significant units’ for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1994, 9, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, W.H.; Allendorf, F.W. What can genetics tell us about population connectivity? Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 3038–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, Y.; Vokoun, J.C.; Letcher, B.H. Fine-scale population structure and riverscape genetics of brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) distributed continuously along headwater channel networks. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 20, 3711–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimenko, M.A.; Marí-Beffa, M.; Becerra, J.; Géraudie, J. Old questions, new tools, and some answers to the mystery of fin regeneration. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat. 2003, 226, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosburg, A.J.; Davis, J.L.; Barnes, M.E. Retention of fin clips and fin and operculum punch marks in rainbow trout. Aquac. Fish. 2022, 7, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejřík, L.; Vejříková, I.; Sajdlová, Z.; Kočvara, L.; Kolařík, T.; Bartoň, D.; Jůza, T.; Blabolil, P.; Peterka, J.; Čech, M. A non-lethal stable isotope analysis of valued freshwater predatory fish using blood and fin tissues as alternatives to muscle tissue. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asahida, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Saitoh, K.; Nakayama, I. Tissue preservation and total DNA extraction form fish stored at ambient temperature using buffers containing high concentration of urea. Fish. Sci. 1996, 62, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuelke, M. An economic method for the fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Oosterhout, C.; Hutchinson, W.F.; Wills, D.P.; Shipley, P. MICRO-CHECKER: Software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2004, 4, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuis, M.-P.; Estoup, A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007, 24, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S.T.; Taper, M.L.; Marshall, T.C. Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, M.; Rousset, F. GENEPOP (version 1.2): Population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J. Hered. 1995, 86, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piry, S.; Luikart, G.; Cornuet, J.M. BOTTLENECK: A computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective population size using allele frequency data. J. Hered. 1999, 90, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Fuerst, P.A. Population bottlenecks and nonequilibrium models in population genetics. II. Number of alleles in a small population that was formed by a recent bottleneck. Genetics 1985, 111, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornuet, J.M.; Luikart, G. Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics 1996, 144, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luikart, G.; Cornuet, J.-M. Empirical evaluation of a test for identifying recently bottlenecked populations from allele frequency data. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, J.C.; Williamson, E.G. Detection of reduction in population size using data from microsatellite loci. Mol. Ecol. 2001, 10, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, R.S.; Do, C. LDNE: A program for estimating effective population size from data on linkage disequilibrium. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008, 8, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Liu, J.X. StructureSelector: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T. adegenet: A R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Rannala, B. Bayesian inference of recent migration rates using multilocus genotypes. Genetics 2003, 163, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Fu, Z.; Li, J.; Ye, Y. Genetic Diversity and Structure Revealed by Genomic Microsatellite Markers of Mytilus unguiculatus in the Coast of China Sea. Animals 2023, 13, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Cho, I.-H.; Kim, H.-K.; Hwang, E.-A.; Han, B.-H.; Kim, B.-H. Assessing the impact of weirs on water quality and phytoplankton dynamics in the south Han River: A two-year study. Water 2024, 16, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, D.; Kang, H.; Kim, K.-H.; Choi, S.-U. Changes of river morphology and physical fish habitat following weir removal. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, J.-C.; Lee, H.-J.; Kwon, H.-J.; Yun, J.-H. Microhabitat Characteristics Determine Fish Community Structure in a Small Stream (Yudeung Stream, South Korea). Proc. Natl. Inst. Ecol. Repub. Korea 2021, 2, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Estoup, A.; Jarne, P.; Cornuet, J.M. Homoplasy and mutation model at microsatellite loci and their consequences for population genetics analysis. Mol. Ecol. 2002, 11, 1591–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, K.A.; Toonen, R.J. Microsatellites for ecologists: A practical guide to using and evaluating microsatellite markers. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson-Natesan, E.G. Comparison of methods for detecting bottlenecks from microsatellite loci. Conserv. Genet. 2005, 6, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, F.W. Genetic drift and the loss of alleles versus heterozygosity. Zoo Biol. 1986, 5, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, P.R.; Osler, G.H.; Woodworth, L.M.; Montgomery, M.E.; Briscoe, D.A.; Frankham, R. Effects of intense versus diffuse population bottlenecks on microsatellite genetic diversity and evolutionary potential. Conserv. Genet. 2003, 4, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, R.S. A bias correction for estimates of effective population size based on linkage disequilibrium at unlinked gene loci. Conserv. Genet. 2006, 7, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, R.S.; Do, C. Linkage disequilibrium estimates of contemporary Ne using highly variable genetic markers: A largely untapped resource for applied conservation and evolution. Evol. Appl. 2010, 3, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, B.A.; Cashner, M.F.; Blanton, R.E. Small fish, large river: Surprisingly minimal genetic structure in a dispersal-limited, habitat specialist fish. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 2253–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.-B.; Song, H.Y.; Suk, H.Y.; Bang, I.-C. Phylogeography of the Korean endemic Coreoleuciscus (Cypriniformes: Gobionidae): The genetic evidence of colonization through Eurasian continent to the Korean Peninsula during Late Plio-Pleistocene. Genes Genom. 2022, 44, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, D.J.; Byrne, M.; Moritz, C. Genetic diversity and conservation units: Dealing with the species-population continuum in the age of genomics. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biun, H.; Sade, A.; Robert, R.; Rodrigues, K.F. Phylogeographic structure of freshwater Tor sp. in river basins of Sabah, Malaysia. Fishes 2021, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraner, A.; Unfer, G.; Gandolfi, A. Good news for conservation: Mitochondrial and microsatellite DNA data detect limited genetic signatures of inter-basin fish transfer in Thymallus thymallus (Salmonidae) from the Upper Drava River. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2013, 409, 01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraner, A.; Cornetti, L.; Gandolfi, A. Defining conservation units in a stocking-induced genetic melting pot: Unraveling native and multiple exotic genetic imprints of recent and historical secondary contact in A driatic grayling. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 1313–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmands, S. Between a rock and a hard place: Evaluating the relative risks of inbreeding and outbreeding for conservation and management. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R.; Ballou, J.D.; Eldridge, M.D.; Lacy, R.C.; Ralls, K.; Dudash, M.R.; Fenster, C.B. Predicting the probability of outbreeding depression. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhymer, J.M.; Simberloff, D. Extinction by hybridization and introgression. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1996, 27, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todesco, M.; Pascual, M.A.; Owens, G.L.; Ostevik, K.L.; Moyers, B.T.; Hübner, S.; Heredia, S.M.; Hahn, M.A.; Caseys, C.; Bock, D.G. Hybridization and extinction. Evol. Appl. 2016, 9, 892–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adavoudi, R.; Pilot, M. Consequences of hybridization in mammals: A systematic review. Genes 2021, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Seo, I.-Y.; Bang, I.-C. Species and hybrid identification of Genus Coreoleuciscus species in hwnag-ji stream, nakdong river basin in Korea. Korean J. Ichthyol. 2017, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Laikre, L.; Schwartz, M.K.; Waples, R.S.; Ryman, N. Compromising genetic diversity in the wild: Unmonitored large-scale release of plants and animals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Real, K.M.; Marshall, J.C.; Schmidt, D.J. Extreme genetic structure in a small-bodied freshwater fish, the purple spotted gudgeon, Mogurnda adspersa (Eleotridae). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.