Abstract

Fisheries are fundamental for food security, and enhancing fishery industry chain resilience (FCR) is essential for safeguarding national supply and promoting high-quality development. With the rapid advancement of new quality productivity (NQP), its integration into the fishery industry chain provides a critical pathway to resilience enhancement and modernization. Using provincial-level data from China between 2012 and 2022, this study evaluates FCR across 29 provinces. A dual machine-learning framework is applied to assess the effects of a provincial NQP index on FCR and its underlying mechanisms. The results show that NQP has a statistically significant positive effect on overall FCR, with estimated coefficients ranging from 0.221 to 0.223 across model specifications. Dimension-specific analysis reveals pronounced heterogeneity: NQP significantly enhances resistance and recovery capacity (rr) as well as innovation and transformation capacity (it), while exerting a negative effect on adjustment and adaptive capacity (aa). Its impact on green ecological restoration capacity (ger) is positive but not statistically significant. Regional heterogeneity analysis shows that the resilience-enhancing effect of NQP is more pronounced in coastal provinces than in inland regions. Mechanism analysis suggests that improvements in labor productivity constitute a key channel through which NQP strengthens FCR. These findings highlight the importance of regionally differentiated strategies for promoting resilient and sustainable fishery development.

Keywords:

new quality productivity; fishery industrial chain resilience; fishery labor productivity; dual machine learning Key Contribution:

This study makes marginal contributions to the following aspects. Firstly, this study introduces the concept of new quality productivity—an innovation-driven, high-tech, and sustainable productive force—to analyze its impact on fisheries supply chain resilience, offering a novel theoretical framework that enriches existing fisheries economics literature. Secondly, it identifies fisheries labor productivity as a key pathway through which new quality productivity enhances fisheries supply chain resilience, contributing to both theoretical and empirical understanding of its mechanisms. Thirdly, it analyses the difference in the impact of new quality productivity on the fishery industrial chain resilience from the perspective of heterogeneity in different regions, so as to provide better guidance for governments to implement precise policies. Finally, it applies a dual machine learning model to improve the accuracy and robustness of empirical estimation, effectively addressing common issues such as the “curse of dimensionality” and model specification bias in traditional econometric methods.

1. Introduction

General Secretary Xi Jinping has emphasized that “we need food from rivers, lakes, and seas,” highlighting the strategic importance of developing sea pastures and “blue granaries” [1]. Fisheries represent the most critical pathway for realizing this goal. As the world’s largest producer and consumer of aquatic products, China has maintained the leading position in total fishery output for 35 consecutive years. However, its output value per unit of water is only one-third that of Norway, indicating that low productivity remains a major bottleneck to efficiency and growth. Addressing this challenge requires strengthening the resilience of the fishery industry chain. Without resilience, efforts to expand production may prove unsustainable, whereas resilience provides the foundation for stable growth, quality enhancement, efficiency gains, and effective risk management. The 2025 Central Document No.1 explicitly introduced the concept of “new quality productivity (NQP) in agriculture”, underscoring innovation-driven transformation. Within this context, fisheries, as an integral part of agriculture, are embracing new development opportunities. NQP, driven primarily by scientific and technological innovation, emphasizes leveraging knowledge and technology to enhance industrial competitiveness and strengthen the capacity to withstand external shocks [2]. Thus, restructuring the fishery industry ecosystem and enhancing industry chain resilience through NQP has become a strategic pathway for modernizing the fishery sector and safeguarding national food security.

‘Chain resilience’ was introduced into industrial economics as an extension of the broader notion of resilience. It refers to the capacity of an industrial chain to recover and rebuild in the face of unexpected risks [3,4,5]. Specifically, when confronted with internal or external shocks, resilient chains are able to rapidly mitigate disruptions, adapt to new conditions, and ultimately restore operational stability [6]. In fisheries, resilience is commonly understood as the capacity to withstand, respond to, recover from, or adapt to external pressures in order to maintain the sustainability of marine ecosystems, fishery resources, and human livelihoods. Existing studies have largely examined fisheries resilience from a socio-ecological perspective, while relatively little attention has been devoted to the resilience of the fisheries industry chain and its determinants. Ojea et al. [7] highlighted the importance of improving the social and institutional environment of fisheries to enhance resilience under climate change. Kleisner et al. [8] evaluated the strengths and weaknesses of multiple fishery systems against socio-ecological criteria, and proposed resilience-building strategies for selected cases. Mason et al. [9] identified 38 attributes—such as assets, flexibility, organization, learning, and mobility—to assess resilience across ecological, social, economic, and governance dimensions. In addition, Malthy et al. [10] conducted a systematic review and underscored both the diversity and ambiguity of the concept of socio-ecological resilience, while also outlining challenges and future opportunities for resilience research. In summary, although considerable progress has been made in socio-ecological resilience studies, systematic investigation of fisheries industry chain resilience and its key influencing factors remains insufficient. Advancing research in this area will not only fill existing knowledge gaps but also provide a stronger theoretical basis for designing more targeted and comprehensive fisheries management strategies.

The emergence of NQP provides sustained momentum for strengthening the resilience of the fishery industry chain. The concept was first introduced by General Secretary Xi Jinping during his visits to Sichuan and Heilongjiang. At its core, NQP emphasizes technological innovation as the primary driver, coupled with the innovative reallocation of production factors, to promote the comprehensive transformation and upgrading of industries [11]. Cultivating and advancing NQP is therefore a critical pathway for modernizing the fishery sector and reinforcing industry chain resilience. A growing body of literature has examined the role of NQP in enhancing industry chain resilience across different sectors. Cui et al. [12] from the perspective of the overall industry chain, indicate that the NQP makes a positive contribution to the enhancement of the toughness of the industry chain. Chen et al. [13] explored digital transformation under the framework of NQP, finding that the integration of digitalization and NQP significantly reduces stock market risks and enhances market resilience.

These research results have greatly enriched the theoretical framework about the role played by the NQP in the process of industrial development and provided important theoretical resources for further exploration in related fields. Based on the relevant results, it can be found that, firstly, the current academic research on the impact of NQP on the toughness of the industry chain lacks research on the impact effect between NQP and the toughness of the fishery industry chain. As a result, analyzing the impact of NQP on the resilience of the fishery industry chain and its internal mechanism is of great guiding significance and helps to find an effective way to achieve high-quality development and modernization of the fishery industry. Secondly, although some scholars have analyzed the toughness of marine fisheries, there is little literature on the toughness of freshwater and seawater overall fisheries, and this research expands the research on the impact of NQP on the toughness of the overall fishery industry chain.

Although substantial research has examined both fishery industry chain resilience (FCR) and NQP, relatively few studies have integrated these two perspectives within a unified analytical framework. To address this gap, this study investigates 29 Chinese provinces (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Qinghai) from 2012 to 2022, measuring provincial-level FCR and analyzing the heterogeneous effects of NQP across regions. The potential contributions of this paper are threefold. First, by quantitatively assessing provincial FCR and incorporating new quality productivity into the analytical framework, we construct a research system that combines theoretical logic with empirical testing, thereby systematically revealing the role of new quality productivity in strengthening industry chain resilience. Second, from the perspective of improving labor productivity, we examine the transmission mechanisms through which NQP enhances FCR, offering a valuable extension to the existing literature. Finally, by employing a dual machine learning model, we leverage the advantages of machine learning algorithms in handling high-dimensional and non-parametric prediction problems. This approach alleviates the challenges of dimensionality and model bias inherent in traditional econometric models, thereby improving the robustness and credibility of the results.

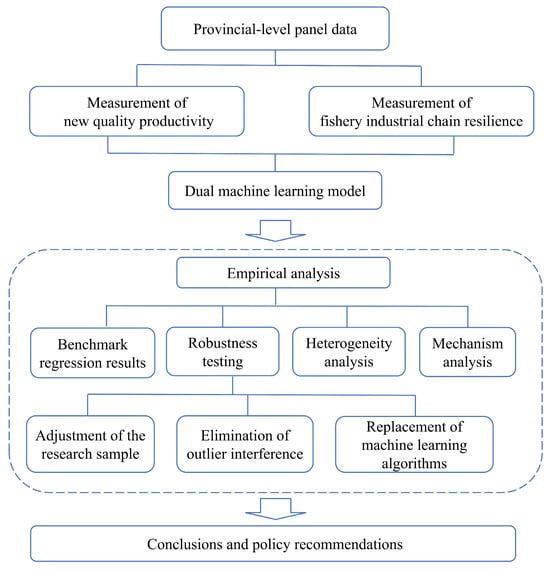

Following the introduction, Section 2 reviews the related literature and conceptualizes the impact pathways between NQP and FCR. Section 3 describes the construction of the analytical framework, including the measurement of key variables, the methodological approach, and the data sources. Section 4 reports the empirical results, while Section 5 concludes with the main findings and policy implications. Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow of this study. The analytical process begins with provincial-level panel data, which are used to construct the independence variable (NQP) and the dependent variable (fishery industry chain resilience). These measurements are then incorporated into a dual machine learning framework to conduct empirical analyses, including benchmark regression, robustness testing, heterogeneity analysis, and mechanism analysis. The process concludes with the derivation of research conclusions and corresponding policy recommendations.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework of the study.

2. Theoretical Hypothesis

Firstly, NQP enhances the resistance and recovery capacity(rr) of the fisheries sector. Driven by NQP, fishery technologies such as the Internet of Things and biotechnology are continuously evolving, fundamentally transforming production and management practices. These innovations not only improve breeding efficiency and product quality but also accelerate the realization of scientific aquaculture, thereby strengthening the sector’s ability to withstand and recover from risks. In parallel, NQP fosters the development of digital infrastructure, which bolsters risk resistance across the entire fisheries value chain. For instance, blockchain and IoT-based monitoring systems improve transparency and information sharing, enable real-time supervision, and facilitate early detection of potential risks, thus reinforcing the industry’s capacity to manage uncertainties [14]. Furthermore, with the deepening of digitalization, more fishers are leveraging online platforms to analyze consumer preferences, guide product development, and enhance the value-added of the industry chain, thereby strengthening resilience against market volatility.

Secondly, NQP effectively strengthens the adjustment and adaptive capacity(aa) of the fishery industry chain. Climate change poses direct challenges to fisheries [15]. However, advances in NQP have substantially improved production flexibility, enabling the sector to better cope with climatic variability and other external shocks. Progress in digital technologies is driving fisheries toward greater intelligence and standardization, thereby reducing uncertainties in production processes. Digital innovations play a critical role in governance. Internet platforms and mobile applications enhance access to and sharing of reliable data, such as catch statistics and management regulations. At the same time, smart aquaculture tools, such as monitoring, forecasting, and decision-support systems, improve the ability of production processes to adjust and adapt to natural and market risks [16]. Moreover, NQP facilitates the flexible reallocation of key production factors, including labor and aquaculture equipment, via digital platforms, allowing rapid deployment of emergency responses and helping to maintain operational continuity. Consequently, NQP substantially enhances the adjustment and adaptive capacity of the fisheries sector and contributes to overall resilience.

Thirdly, the development of NQP can effectively enhance the innovation and transformation capacity(it) of the fishery industry. As a concentrated expression of technological and organizational innovation, NQP promotes collaborative innovation and alliances among different actors in the fishery industry chain, thereby strengthening the chain’s ability to cope with external shocks. Through blockchain technology, each link of the industry chain forms a value co-creation network, breaking down information barriers and facilitating closer cooperation between upstream and downstream enterprises. Real-time sharing of sales and production data across farming, fishing, processing, and logistics links enables more efficient scheduling and coordination, further improving the industry’s innovation and transformation capacity [17]. Additionally, digital twin technology, artificial intelligence, and other advanced tools are deeply integrated into the life-cycle management of the fishery industry, driving the evolution of the industrial system toward intelligence [18]. Growth model optimization and disease prediction systems based on machine learning algorithms have significantly enhanced the accuracy of biomass monitoring. The integrated application of these technologies substantially strengthens the industry’s capacity for innovation and transformation, contributing to greater overall resilience.

Fourthly, the development of NQP can effectively improve green ecological restoration capacity(ger). NQP, driven by scientific and technological innovation, relies on digital technologies to achieve precise monitoring and dynamic regulation of the fishery ecosystem. For example, the integration of the Internet of Things, remote sensing, and intelligent sensors enables the construction of comprehensive data collection networks, providing real-time access to water quality parameters, biological behavior, and environmental changes. This information supports the accurate formulation of pollution prevention strategies and resource management plans, thereby strengthening the industry’s capacity for green ecological restoration [19]. In addition, NQP emphasizes the synergistic enhancement of human capital and digital infrastructure. This synergy not only promotes the effective application of ecological restoration technologies but also improves their practical effectiveness by enhancing practitioners’ digital literacy and capacity for technological innovation [20]. Such improvements not only advance professional skills but also facilitate the translation of technological innovations into practical operations, further promoting green management and ecological restoration across the fisheries sector.

Based on the above analyses, hypothesis 1 is proposed: new quality productivity can promote the resilience of the fishery industry chain.

The development of NQP has also brought about new workers, objects and means of labor into the fishery industry. First, by cultivating more skilled and versatile workers, NQP will improve the quality of workers in all links of the fishery industry chain, thereby boosting the efficiency of fishery labor production and thus enhancing fishery industrial chain resilience. Experienced and skilled fishery workers can better adapt to the development of sophisticated equipment, which is an important technical talent pool to enhance the resilience of the fishery industry chain. Second, NQP has transformed the objects of labor. Advances in biotechnology have produced disease-resistant, fast-growing, and marketable aquatic varieties, significantly increasing output per unit of water and improving labor productivity. These improvements contribute to greater stability and resilience throughout the industry chain. Third, NQP has diversified and modernized the means of labor. Production now incorporates digital labor, advanced technologies, and intelligent equipment, such as smart sensing devices. Supported by mechanization and modernization, these innovations further enhance labor productivity and reinforce the resilience of the fishery industry chain.

Based on the above analysis, hypothesis 2: new quality productivity promotes fishery industrial chain resilience by improving labor productivity.

3. Study Design and Methods

3.1. Study Area

This study constructs a provincial-level panel dataset covering 29 Chinese provinces over the period 2012–2022. The sample period is chosen because China’s official statistical system for fisheries and related sectors has become increasingly standardized since 2012, with improved data coverage, consistency, and reliability across regions. Tibet, Qinghai, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan are excluded from the sample. Including these regions would undermine data consistency and weaken the comparability of interprovincial observations. The data are primarily sourced from the China Fishery Statistical Yearbook and the China Statistical Yearbook, which provide authoritative and continuous statistics. To ensure temporal continuity of the panel dataset, a small number of missing observations for individual indicators are imputed using linear interpolation.

In this study, the complete dataset includes all variables used to construct the fishery industrial chain resilience (Table 1), new quality productivity index (Table 2), the control variables, and the mechanism variable. All raw variables are obtained directly from official statistical yearbooks, and their measurement units strictly follow the official standard (units are listed in Table 1 and Table 2 to ensure clarity and consistency).

Table 1.

Indicator system for measuring fishery industrial chain resilience (FCR), the dependent variable.

Table 2.

Indicator system for measuring new quality productivity (NQP), the independent variable.

3.2. Variable Definitions and Indicator Systems

Based on the constructed dataset, this study defines the dependent variable, independent variable, control variables, and mechanism variable. Several composite indices are constructed using multi-dimensional indicators to capture complex economic and structural characteristics.

(1) Dependent variable: Fishery industrial chain resilience (FCR).

Fishery industrial chain resilience is measured as a composite index reflecting the ability of the fishery sector to resist external shocks, adjust and adapt to changing environments, promote innovation-driven transformation, and achieve green and sustainable development. Accordingly, FCR is selected as a dependent variable in this study. Based on the existing literature and data availability, an indicator system is constructed from four dimensions: resistance and recovery capacity, adjustment and adaptive capacity, innovation and transformation capacity, and green ecological restoration capacity, forming a total of 14 measurement indicators, as reported in Table 1. In general, higher values of these indicators correspond to stronger resilience. However, total direct economic losses from fishery disasters and industrial wastewater discharges reflect adverse shocks and environmental pressure on the fishery system; therefore, higher values of these indicators indicate weaker resilience.

To eliminate the influence of heterogeneous measurement units and ensure cross-indicator comparability, all indicators are normalized using the min–max method within the entropy value framework. Negative indicators are transformed inversely prior to normalization. The entropy value method is then employed to objectively determine indicator weights based on information entropy, and a composite FCR index is obtained through weighted aggregation of all normalized indicators. The resulting index ranges between 0 and 1 and is used in the subsequent empirical analysis to examine the impact of new quality productivity on fishery industrial chain resilience.

(2) Independent variable: New quality productivity (NQP)

New quality productivity is selected as independent variable in this study. As shown in Table 2, an evaluation index system for NQP is constructed based on three dimensions: workers, labor objects, and labor materials [21]. These dimensions capture the quality of labor, the modernization of production inputs, and the digital–technological foundation that jointly shape productivity under the new development paradigm.

Indicators are obtained directly from official statistical yearbooks and maintained in their original measurement units. To ensure comparability across indicators and eliminate the influence of heterogeneous scales, all variables are normalized using the min–max method within the entropy value framework. The entropy value method is then employed to determine indicator weights objectively based on information entropy, and a composite NQP index is calculated through weighted aggregation.

(3) Control variables

To mitigate omitted-variable bias and capture regional conditions that may concurrently affect both new quality productivity (NQP) and fishery industrial chain resilience (FCR), a set of control variables is included in the empirical models. Financial support (Gov) is measured as the ratio of local general budget expenditure to GDP. Urbanization level (Urb) is defined as the proportion of the urban resident population to the total population at the end of the year. Openness to the outside world (Open) is expressed as the ratio of total local imports and exports to GDP. Technology market development (Tech) is measured as the ratio of technology market turnover to GDP. Financial development (Fin) is represented by the ratio of outstanding loans of financial institutions to GDP. Direct economic losses from natural disasters (Dln) are measured by the monetary value of such losses. Industrial structure upgrading (Lo) is defined as the ratio of the combined GDP of the secondary and tertiary fishery industries to the total GDP of the fishery industry.

In addition, to improve model fit, quadratic terms of each provincial variable are included in the regressions, while controlling for both time and province fixed effects to enhance the accuracy of the estimates.

(4) Mechanism variable

To further uncover the internal pathway through which new quality productivity (NQP) influences fishery industrial chain resilience (FCR), this study incorporates a mediating variable reflecting productivity improvement within the fishery sector. Labor productivity in fisheries (Lab) is measured as the ratio of the total economic value of fisheries to the number of employed fishery workers. Please refer to Table 3 for specific descriptions of each variable. The variable Dln (Direct economic losses from natural disasters) exhibits relatively large values because it is measured in monetary terms and captures regional economic scale and extreme events. These large magnitudes do not affect the estimation, as the double machine learning framework effectively removes confounding influences and accommodates nonlinearities and heterogeneity.

Table 3.

Variable Description Table.

3.3. Model

3.3.1. Model Specification

Based on the above theoretical analysis, the paper will empirically investigate the effect of NQP on the resilience of the fishery industry chain. Chernozhukov et al. [22] proposed a dual machine learning (DML) model that can effectively portray the nonlinear relationship between variables. In the development process of FCR, interactions among variables are often nonlinear, and the machine learning algorithms embedded in the DML framework can handle such nonlinearities while enhancing model explanatory power. Compared with the traditional causal inference method, DML is particularly suitable for this study because the resilience of the fishery industry chain is influenced by multiple factors, including technological development and industrial structure optimization. Traditional approaches often face the “curse of dimensionality,” whereas the regularization procedures within DML can automatically select high-dimensional control variables and identify a subset of key predictors with significant explanatory power, thereby reducing estimation bias. Accordingly, the partial linear model for double machine learning is specified as follows:

where is the resilience of the fishery industry chain in the province in year , and denotes the level of NQP in the province in year ; is a set of control variables; and is the error term with a conditional mean of zero. By directly estimating Equations (1) and (2), the estimator can be obtained as follows

where denotes the sample size. Based on the above estimator, its potential estimation bias can be further examined as follows:

where are assumed to follow mean-zero normal distributions. . It should be noted that the double machine learning approach relies on machine-learning and regularization algorithms to estimate the unknown functional form . Such procedures inevitably introduce regularization bias. Although regularization prevents the variance of the estimator from becoming excessively large, it simultaneously implies that the estimator is not strictly unbiased. In particular, the convergence rate of toward the true function is relatively slow, typically on the order of , which is less rapid than the parametric rate . As a result, when , the term may diverge, making it difficult for the estimator to converge to the true parameter .

To accelerate convergence and ensure that the estimator remains unbiased in small samples, the following auxiliary regression is constructed:

where denotes the regression function of the disposal variable on the high-dimensional control variable, and is the error term with a conditional mean of 0. A machine learning algorithm is used to evaluate and compute its residuals, residuals ; meanwhile, a machine learning algorithm is used to estimate , to obtain . serves as an orthogonalized treatment variable. To avoid overfitting and ensure Neyman orthogonality, cross-fitting is employed when estimating the nuisance functions and . The resulting coefficient estimates are as follows:

Similarly, Equation (7) can be approximated as follows:

In this context, follows a mean-zero normal distribution. Because the two machine-learning procedures are used to estimate the unknown functions, the term converges at a rate determined by how fast approaches and how fast approaches , that is, at the rate . Compared with Equation (4), the term thus converges more rapidly to zero, enabling the estimator to achieve an unbiased estimate of the disposition coefficient.

3.3.2. Training Strategy and Implementation Details

This study applies the Double Machine Learning (DML) framework. To model the high-dimensional relationship between fishery industry chain resilience and NQP, Lasso regression is employed for its regularization and variable selection properties, effectively identifying key covariates and controlling overfitting. Estimation uses a five-fold cross-fitting procedure, where models are iteratively trained on subsets of data to predict the conditional expectations of the treatment and outcome variables, ensuring robustness and asymptotic normality of the estimators. All implementations are executed in Stata 18 using the ddml and pystacked modules, with a fixed random seed for reproducibility, while keeping the treatment (NQP) and controls consistent across model specifications.

This approach leverages machine learning’s flexibility to capture complex relationships while preserving the rigor of causal inference. The result is a statistically robust and interpretable estimate of the causal effect of NQP on fishery industry chain resilience.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Benchmark Regression Results

Based on China’s provincial-level data from 2012 to 2022, the paper explores the impact of NQP on the resilience of the fishery industry chain. The analysis employs the NQP index of each province as a continuous treatment variable and measures FCR across 29 provinces (excluding Qinghai, Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) using a dual machine learning model. Under the setting of sample split ratio of 1:4, the Lasso regression algorithm was applied to estimate both the main and auxiliary regressions. The core results, which report the estimated causal effects of NQP from the DML framework, are presented Table 4. Columns (1) and (2) present results for the comprehensive FCR index, while columns (3) to (6) detail the effects on its four dimensions: resistance and recovery capacity (rr), adjustment and adaptive capacity (aa), innovation and transformation capacity (it), and green ecological restoration capacity (ger). The notations “Yes” or “No” specify the model specification: “Yes” indicates the inclusion of the corresponding set of variables (quadratic terms of controls, year fixed effects, or province fixed effects) in the final causal estimation. Statistical inference relies on robust standard errors, and the use of Lasso regularization with cross-fitting ensures stable estimation.

Table 4.

Baseline regression results.

In column (1), after controlling for year and province fixed effects and linear control terms, NQP increases FCR by 0.223 (p < 0.01). When quadratic terms of controls are additionally included in column (2), the coefficient remains highly stable (0.221, p < 0.01), with decreasing by only 0.9%, indicating strong robustness to model specification. These estimates suggest that a one-unit increase in NQP is associated with approximately a 22% improvement in the composite resilience index when standardized variables are considered.

In addition, this paper further explores the specific impacts of NQP on the dimensions of FCR, and columns (3) to (6) show the regression coefficients of NQP on resistance and recovery capacity, adjustment and adaptive capacity, innovation and transformation capacity, and green ecological restoration capacity. The results show that NQP significantly improves resistance and recovery capacity (0.353, p < 0.01) and innovation and transformation capacity (0.338, p < 0.01). These effect sizes are economically meaningful: a one-unit rise in NQP strengthens rr and it by 35.3% and 33.8%. By advancing technological innovation and integrating digital technologies into the fishery sector, NQP enhances total economic output and raises fishermen’s income, incentivizing technology adoption. This process improves aquaculture efficiency, strengthens disease prevention, and helps balance production areas with disaster risks, thereby increasing the industry chain’s resistance and recovery. Meanwhile, greater technological penetration elevates product quality and cost efficiency, reduces reliance on imported seedlings, and reinforces the industry chain’s innovation and transformation capacity. In contrast, the coefficient for adjustment and adaptive capacity is negative and statistically significant (–0.161, p < 0.10), indicating that a one-unit rise in NQP reduces aa by 16.1%. This suggests that capital-intensive technological upgrading may reduce labor flexibility, decrease traditional vessel numbers, and increase maintenance burdens, jointly weakening adaptive capacity. Finally, for green ecological restoration capacity, although the coefficient is positive (0.048), it is not statistically significant. While the development of NQP supports “green expansion” and promotes technologies that align environmental and industrial development, its effects on local environmental protection expenditures unfold slowly, leading to a delayed and currently unobservable ecological impact.

4.2. Robustness Testing

4.2.1. Adjustment of the Research Sample

Considering that natural disasters, such as typhoons and red tides, may affect the impact of NQP on FCR, regression analyses based on all 29 provinces could introduce estimation bias. Therefore, this paper excludes the two provinces, Hainan and Guangdong, where typhoons and red tides are frequent natural disasters, from the list of 29 provinces. The specific regression results are shown in Table 5 (1). After adjusting the province sample, the regression coefficient of NQP on FCR is slightly reduced, and the significance level decreases from 1% to 5%. Nevertheless, the core conclusion remains unchanged: NQP still has a statistically significant positive effect on the resilience of the fishery industry chain, indicating that the findings are robust.

Table 5.

Robustness test (1).

4.2.2. Elimination of Outlier Interference

To further enhance the robustness of the estimation results, all variables in the paper were reduced-tailed. We performed 1% and 5% winsorization for all variables, in order to reduce the impact of outliers on the regression results. The regression results are shown in Table 5 (2). After controlling for outliers, the significance of the main variables remains unchanged, indicating that the core conclusions of this study are highly robust across different winsorization settings.

4.2.3. Replacement of Machine Learning Algorithms

The split ratio between the main sample and the negative sample in the benchmark regression of this paper is 1:4. To examine whether the split ratio affects the regression results, the ratio was adjusted to 1:2 and 1:7, and the results are reported in Table 6 (1). The regression coefficients of NQP on FCR remain positive and statistically significant, confirming the robustness of the benchmark regression findings. Furthermore, to test whether different dual machine learning algorithms influence the results, the main and auxiliary regressions were re-estimated using the random forest (RF) algorithm. As shown in Table 6 (2), the replacement of the algorithm does not materially alter the conclusions, further supporting the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

Table 6.

Robustness test (2).

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

To further investigate potential regional heterogeneity in the impact of NQP on FCR, this study examines differences between coastal and inland regions. Guided by the 2025 Fisheries and Fisheries Administration Work Deployment Conference, which emphasizes “strengthening inland and marine aquaculture and optimizing marine fishing” [23], the analysis explores how the effects of NQP vary geographically. The regression results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity Analysis.

Table 7 shows clear quantitative differences. In coastal regions (columns (1)), the coefficient of NQP is 0.216 and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating a positive and economically meaningful enhancement of FCR. By contrast, in inland regions (columns (2)), the coefficient is –0.831 and not statistically significant, suggesting that NQP does not exert a measurable effect on FCR in these provinces. This contrast highlights pronounced regional heterogeneity. This suggests that NQP significantly enhances the resilience of the fishery industry chain in coastal areas, but its effect in inland regions is limited. This regional disparity can be explained by the growing phenomenon of talent migration from inland to eastern coastal areas, often referred to as “the peacock flying southeast”. Inland regions face considerable pressure from brain drain, while coastal areas attract highly skilled professionals due to their favorable geographic and economic conditions. The concentration of talent in coastal regions facilitates the rapid adoption and diffusion of new technologies and equipment promoted by NQP, thereby strengthening the resilience of the industry chain. In addition, the presence of marine universities, research institutes, and corporate research and development centers in coastal areas creates a complete system linking industry, academia, research, and application. This integrated system improves scientific and technological innovation, promotes knowledge transfer and technology application, and further enhances industry chain resilience. By contrast, inland regions produce fewer patents and scientific publications, reflecting relative disadvantages in research capacity, innovation resources, and technological application.

4.4. Mechanism Analysis

According to the previous theoretical analysis, NQP is expected to enhance the resilience of the fishery industry chain by improving labor productivity. To empirically test this mechanism, the study employs a causal mediation approach as proposed by Jiang [24]. The results of the mechanism test are presented in Table 8, confirming Hypothesis 2.

Table 8.

Mechanism Validation.

From the results in Table 8, the regression coefficient of NQP is positive and significant, indicating that NQP enhances labor productivity. Specifically, the coefficient of NQP is 36.722 and statistically significant at the 1% level. The development of NQP has brought about significant technological innovation and equipment upgrading in the fishery sector, and this progress is mainly reflected in the application of high technology, such as precision fishery technology and an intelligent farming system. These advanced technologies and equipment, by effectively reducing human errors and improving the controllability and stability of the production process, have significantly increased the output and efficiency of fishery production, thus enhancing the labor productivity of the fishery industry. At the same time, the wide application of IoT technology greatly promotes the refinement of fishery production management, making the fishery production process more accurate and efficient. This refined management directly improves fishery labor productivity, which is manifested in the significant shortening of the growth cycle of fish. Specifically, a shorter growth cycle means that more production cycles can be completed within the same period of time, thus creating more elastic space for fishery production. This increased flexibility not only improves the flexibility and adaptability of fishery production but also accelerates the speed of capital turnover and improves the overall efficiency of industrial operations. Rapid capital turnover enables the industry to respond more flexibly to market changes. When market demand fluctuates or prices fluctuate, the industry can respond quickly by adjusting its production program, improving its resilience.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Research Conclusions

This study situates new quality productivity (NQP) within the specific context of the fishery industry chain and examines its role in shaping industry chain resilience. Existing studies have mainly explored the relationship between productivity upgrading, digital transformation, and resilience in manufacturing or service sectors, while empirical evidence from primary industries, particularly fisheries characterized by biological uncertainty and ecological constraints, remains relatively scarce. This research makes distinct contributions on multiple fronts. Theoretically, it extends the discourse on NQP and industrial resilience into the domain of resource- and ecology-dependent primary industries, elucidating how productivity upgrading operates within the context of sector-specific biological and environmental constraints. Methodologically, it employs a double machine learning framework to robustly identify the causal effect of NQP on resilience, effectively addressing potential endogeneity and model specification biases common in related empirical analyses. Empirically, it provides granular, dimension-specific evidence on the multifaceted impacts of NQP on fishery chain resilience. The main findings can be summarized as follows.

First, NQP significantly enhances the overall resilience of the fishery industry chain, and this effect remains robust across alternative model specifications, indicating that NQP constitutes an important driver of resilience improvement in fisheries. Second, the impacts of NQP differ across resilience dimensions. NQP exerts a strong positive influence on resistance and recovery capacity and innovation and transformation capacity, while its effect on adjustment and adaptive capacity is negative, suggesting that short-term adjustment frictions may arise during technological upgrading. Its impact on green ecological restoration capacity is positive but weak and statistically insignificant, implying that ecological effects tend to materialize more gradually. Third, mechanism analysis confirms that NQP strengthens industry chain resilience through the labor productivity channel, highlighting the role of technological upgrading, intelligent equipment adoption, and refined management in improving production efficiency and operational stability. Fourth, the resilience-enhancing effect of NQP exhibits clear regional heterogeneity, with stronger effects observed in coastal provinces, reflecting differences in digital infrastructure, human capital accumulation, and industry–research linkages.

Several limitations merit attention. First, although the analytical framework and empirical strategy adopted in this study can, in principle, be applied to other industries, the estimated effects and underlying mechanisms are derived from the fishery sector and may not be directly transferable to industries with different production technologies, organizational forms, or regulatory environments. Second, the use of provincial-level data may obscure intra-regional heterogeneity and micro-level adjustment processes. Future research could extend this framework to other primary or secondary industries and employ firm-level or project-level data to further test the external applicability and dynamic effects of NQP. Despite these limitations, this study deepens the understanding of how NQP operates under sector-specific constraints and provides a targeted reference for policies aimed at enhancing resilience and high-quality development in the fishery industry.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

To promote the development of new quality productivity in China, enhance labor productivity in fisheries, and strengthen the resilience of the fishery industry chain, this study formulates the following policy recommendations in light of the empirical findings. Firstly, the cultivation and development of NQP should be reinforced to provide a strong impetus for the modernization of the fisheries industry. Fishery enterprises and research institutions should be encouraged to increase investment in the development of innovative fishery technologies and production models, thereby enhancing the overall NQP of the sector. Policy support is also essential to stimulate the innovative capacity of fishery enterprises. The government should introduce measures such as tax incentives and financial subsidies to facilitate technological transformation and innovation, promoting the advancement of NQP in fisheries. Finally, human capital is a key driver of industrial development. Efforts should be made to cultivate and attract professionals with advanced technical and management expertise in fisheries, providing essential intellectual support for the growth of NQP in the industry.

Secondly, the productivity of fishery labor should be enhanced. Training programs should be strengthened to improve the skills of fishermen. Traditional fishing and aquaculture methods can no longer meet the demands of a resilient and responsive fisheries industry. The government should provide systematic and professional training to help fishermen adapt to new technologies and equipment, reducing productivity losses caused by inadequate skills. In addition, such training enables fishermen to better understand market dynamics and management practices, enhancing their ability to make informed decisions and further improving labor productivity. Furthermore, promoting mechanization and automation in fisheries is an important means to increase labor productivity. The adoption of advanced machinery and equipment can significantly reduce manual labor, improve production efficiency, and increase operational precision. The government should actively support the deployment of fishery machinery and automation technologies, which can not only raise the level of mechanization and productivity but also expand production flexibility, thereby strengthening the resilience of the fishery industry chain.

Thirdly, NQP should be promoted in conjunction with green and sustainable development to strengthen the resilience of the fishery industry chain. As a key driver of fishery development, NQP should be advanced under the principle of green development, balancing ecological protection and production, strengthening green prevention and ecological restoration, and ensuring the high-quality and sustainable development of the industry chain. In practice, local governments should increase fiscal expenditures on environmental protection and establish stable funding mechanisms to support green transformation and ecological restoration. At the same time, the number and capacity of fishery law enforcement organizations should be enhanced to strengthen supervision of illegal fishing and pollution discharge. Moreover, stricter control over industrial wastewater discharges and the promotion of clean production and green technologies are essential to reduce environmental risks at the source and improve the capacity of the fishery industry chain to withstand external shocks.

Fourthly, NQP should be advanced in line with regional realities to promote coordinated development. To address regional disparities, the state should increase policy and resource support for inland areas, enhance investment in education and scientific research, improve research conditions, and strengthen talent training. Preferential policies, such as housing subsidies and research start-up funds, can also be introduced to attract talents from coastal regions to inland areas. For coastal regions, while maintaining their advantages, more efforts should be devoted to technological transformation and innovation in traditional industries, steering development toward high-end, intelligent, and green directions. At the same time, coastal and inland regions should strengthen collaboration by establishing cross-regional cooperation mechanisms to facilitate the sharing of scientific and technological resources and the transfer of research outcomes. Universities and research institutes in coastal areas are encouraged to engage in joint research and technological cooperation with inland enterprises, thereby building an innovation system that deeply integrates industry, academia, and research. In addition, the government may set up dedicated support funds to promote key technology R&D and demonstration projects, narrowing regional gaps and fostering coordinated and common progress.

Author Contributions

Methodology, validation, formal analysis, S.C.; Investigation, resources and writing—review & editing, D.W.; Methodology, software, validation, formal analysis and writing—review & editing, Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Major Program of the National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC), grant number 21&ZD100, project title: Evaluation of the Development Potential of the Deep Blue Fisheries Industry under Climate Change; the China Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System Support Project, grant number CARS-47-G29; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), grant number 72573107, project title: A Study on the Bioeconomic Mechanisms of Dominant Seawater Fish Farming Models in China from the Perspective of Green Development.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles and guidelines. All research involving human participants was carried out with their informed consent, ensuring they were fully aware of the study’s purpose, procedure potential risks, and benefits. Participation was voluntary, and participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their data, which was used exclusively for research purposes. The authors declare no conflicts of interest, and the research was conducted independently and impartially.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, W.; Xie, S.; Xu, H.; Shan, X.; Xue, C.; Li, D.; Yang, H.; Zhou, H.; Mai, K. High-Quality Development Strategy of Fisheries in China. Strateg. Study Chin. Acad. Eng. 2023, 25, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Tong, X. How New Quality Productivity Affects Industrial Chain Resilience: Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Evidence. Chin. J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 40, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarov, S.Y.; Holcomb, M.C. Understanding the Concept of Supply Chain Resilience. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2009, 20, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Y. The Impact of Digital Infrastructure on Industrial Chain Resilience: Evidence from China’s Manufacturing. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 37, 1112–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Meng, T.; Fang, D. Enhancing Infrastructural Dynamic Responses to Critical Residents’ Needs for Urban Resilience through Machine Learning and Hypernetwork Analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 106, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J. Assessing the Link between Digital Government Development and Urban Industrial Chain Resilience: Evidence from Public Data Openness. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 112, 107796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojea, E.; Fontán, E.; Fuentes-Santos, I.; Bueno-Pardo, J. Assessing Countries’ Social-Ecological Resilience to Shifting Marine Commercial Species. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleisner, K.M.; Ojea, E.; Battista, W.; Burden, M.; Cunningham, E.; Fujita, R.; Karr, K.; Amorós, S.; Mason, J.; Rader, D.; et al. Identifying Policy Approaches to Build Social–Ecological Resilience in Marine Fisheries with Differing Capacities and Contexts. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 79, 552–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.; Eurich, J.G.; Lau, J.; Battista, W.; Free, C.M.; Mills, K.L.; Tokunaga, K.; Zhao, L.; Dickey-Collas, M.; Valle, M.; et al. Attributes of Climate Resilience in Fisheries: From Theory to Practice. Fish Fish. 2021, 23, 522–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, K.; Mills, K. What’s the Story? Using News Articles to Examine Resilience Pathways and Domains in the Southern New England American Lobster (Homarus americanus) Fishery. Ecol. Soc. 2024, 29, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, R.; Cai, X. New Quality Productivity and China’s Strategic Shift towards Sustainable and Innovation-Driven Economic Development. J. Interdiscip. Insights 2024, 2, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Du, D. New Quality Productive Forces, Urban-Rural Integration and Industrial Chain Resilience. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Alexiou, C. Digital Transformation as a Catalyst for Resilience in Stock Price Crisis: Evidence from a “New Quality Productivity” Perspective. Asia-Pac. Financ. Mark. 2025, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.N.; Peko, G.; Sundaram, D.; Piramuthu, S. Blockchain-Based Agile Supply Chain Framework with IoT. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 24, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopp, L.; Resplandy, L.; Orr, J.C.; Doney, S.C.; Dunne, J.P.; Gehlen, M.; Halloran, P.; Heinze, C.; Ilyina, T.; Séférian, R.; et al. Multiple Stressors of Ocean Ecosystems in the 21st Century: Projections with CMIP5 Models. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 6225–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, L. Development Path, Foreign Experiences and Countermeasures of China’s Digital Development in Aquaculture. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2025, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino-Zondervan, F.; Ngoc, P.T.A.; Roskam, J.L. Use Cases and Future Prospects of Blockchain Applications in Global Fishery and Aquaculture Value Chains. Aquaculture 2022, 565, 739158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Lv, H.; Fridenfalk, M. Digital Twins in the Marine Industry. Electronics 2023, 12, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gui, F. The Application and Research of New Digital Technology in Marine Aquaculture. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Wu, M.; Zhang, D. Evidence of the Contribution of the Technological Progress on Aquaculture Production for Economic Development in China—Research Based on the Transcendental Logarithmic Production Function Method. Agriculture 2023, 13, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, R. New Quality Productivity: Index Construction and Spatiotemporal Evolution. J. Xi’an Univ. Financ. Econ 2024, 37, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Demirer, M.; Duflo, E.; Hansen, C.; Newey, W.; Robins, J. Double/Debiased Machine Learning for Treatment and Structural Parameters. Econom. J. 2018, 21, C1–C68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministry Deploys Fishery and Fishing Administration Work for 2025 [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202502/content7005728.html (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Jiang, T. Mediating Effects and Moderating Effects in Causal Inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.