Zebrafish Girella zebra (Richardson 1846): Biological Characteristics of an Unexploited Fish Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Regime and Length and Weight Measurements

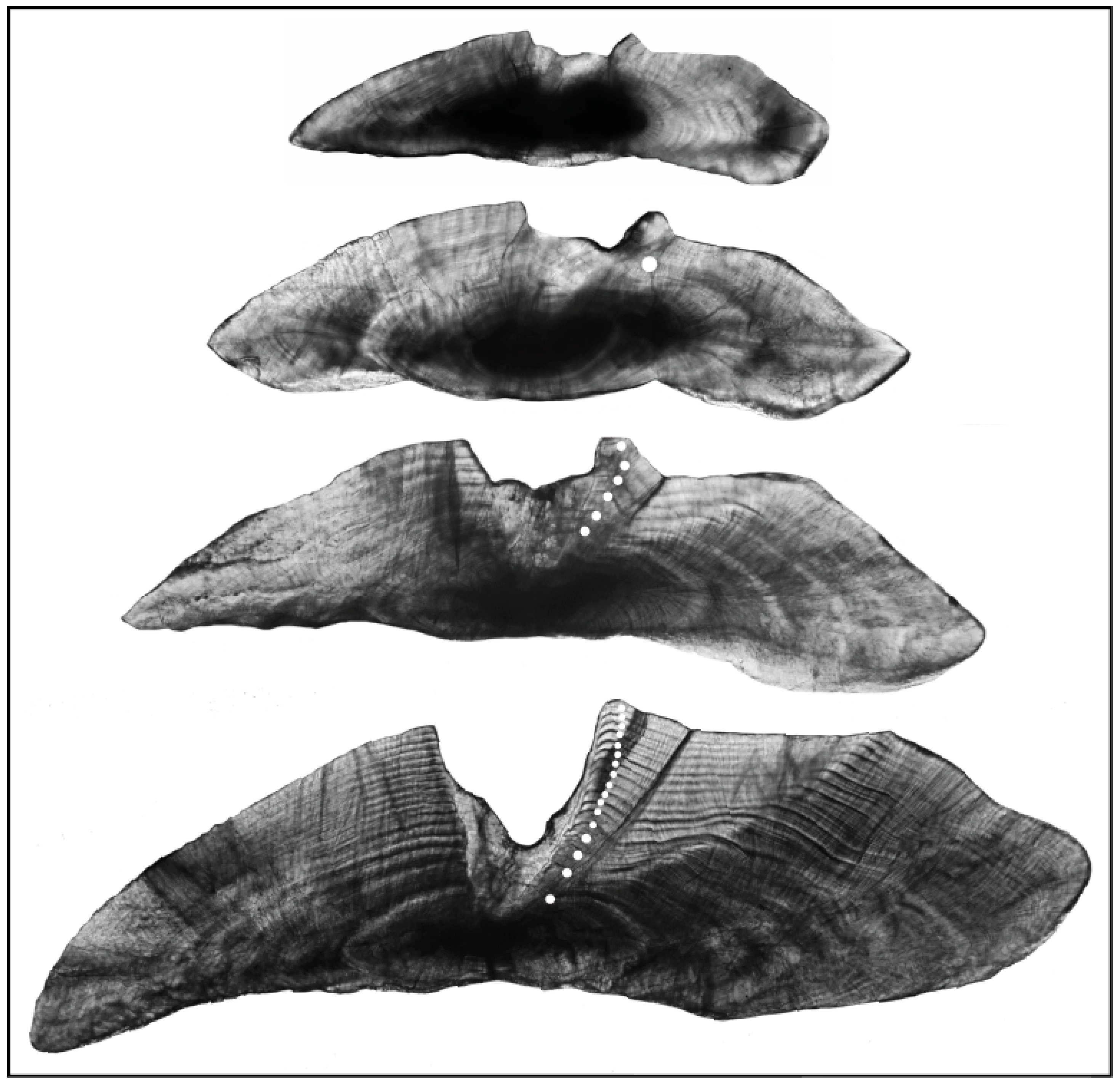

2.2. Age Determination and Validation

2.3. Growth and Mortality

2.4. Duration and Prevalence of Spawning and Maturation

3. Results

3.1. Interpretation of Otoliths and Age Validation

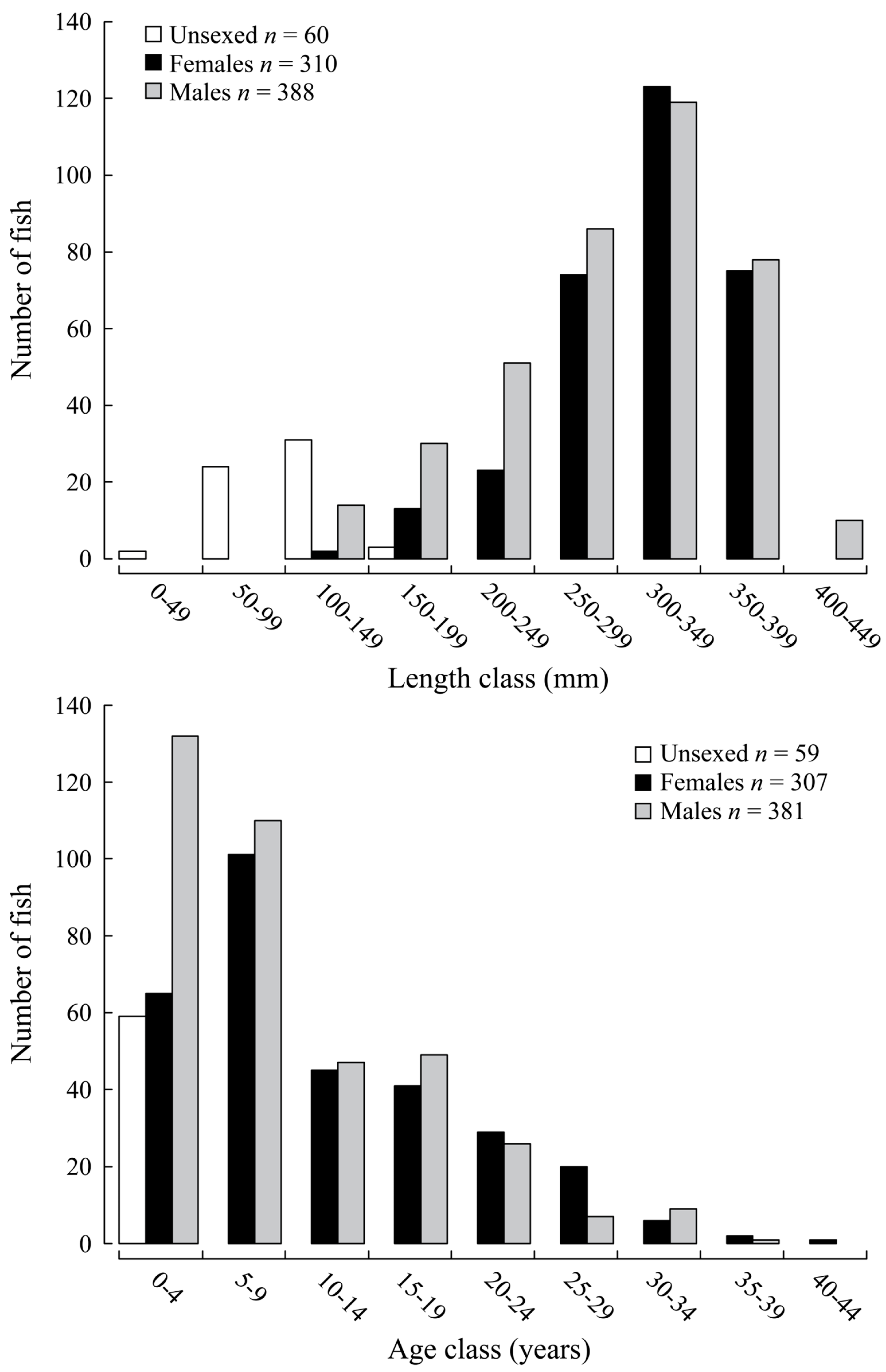

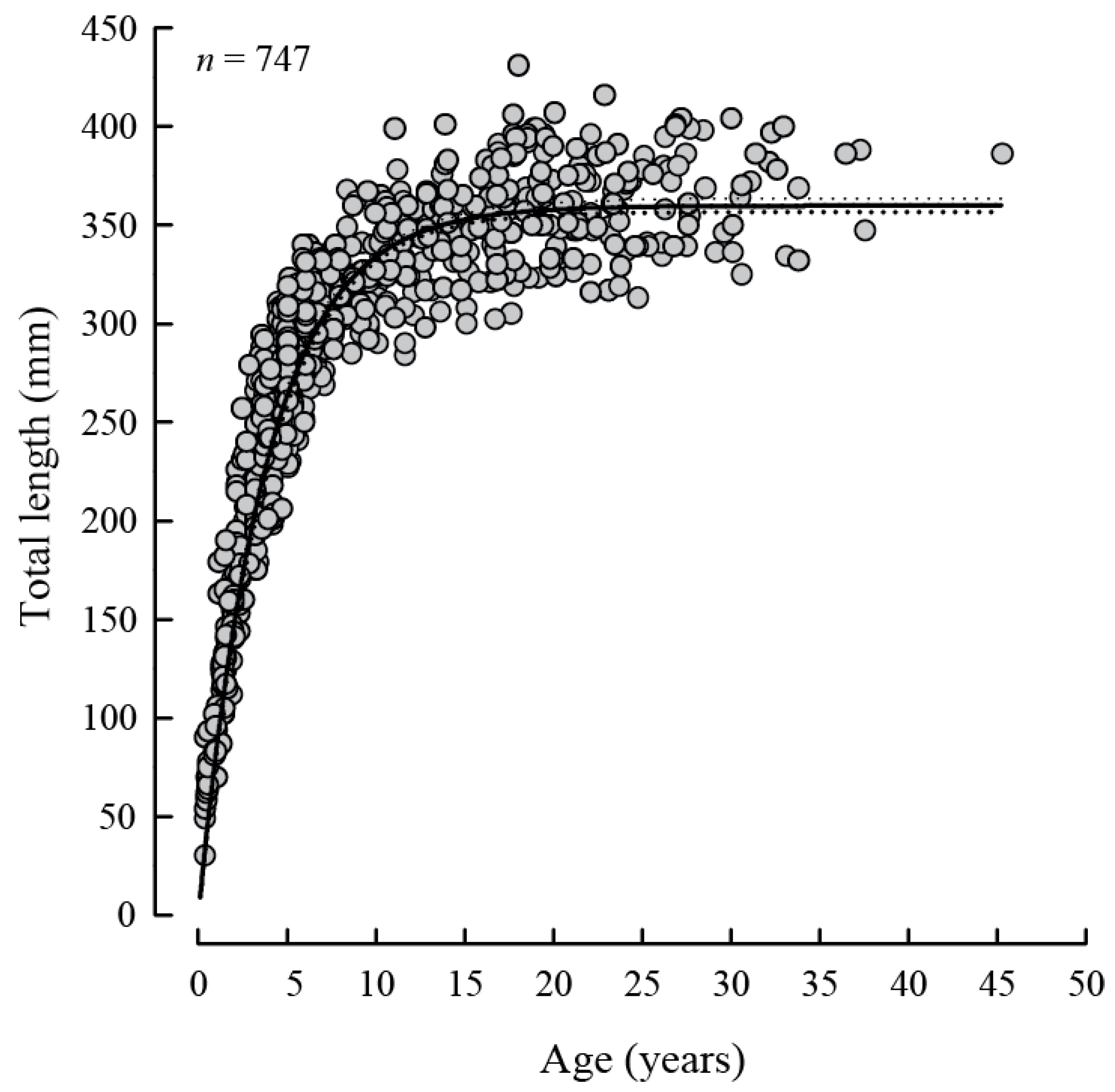

3.2. Length and Age Composition, Growth and Mortality

3.3. Evidence of Spawning Time and Duration

3.4. Lengths and Ages at Maturity

4. Discussion

4.1. Age, Growth and Mortality

4.2. Spawning

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TL | Total length |

| GSI | Gonadosomatic indices |

| vBGC | von Bertalanffy growth curves |

| CV | coefficient of variation |

| M | Natural mortality |

| Z | Total mortality |

| MI | marginal increments |

References

- Hutchins, B.; Swainston, R. Sea Fishes of Southern Australia; Swainston Publishing: New South Wales, Australia, 1986; p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D.J. Kyphosus vaigiensis in Fishes of Australia. 2018. Available online: https://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/genus/751 (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Yagishita, N.; Nakabo, T. Revision of the genus Girella (Girellidae) from East Asia. Ichthyol. Res. 2000, 47, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V.H. Fishes of the World, 5th ed.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; p. 651. [Google Scholar]

- Swainston, R. Swainston’s Fishes of Australia: The Complete Illustrated Guide; Penguin Australia Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2020; p. 832. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, S.; Edgar, G. (Eds.) Chapter 16: Bottom-feeding fishes. In Ecology of Australian Temperate Reefs: The Unique South; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2013; pp. 395–418. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.; Hughes, J.M. Longevity, growth, reproduction and a description of the fishery for silver sweep Scorpis lineolatus off New South Wales, Australia. N. Z. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2005, 39, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.A.; Ives, M.C.; Macbeth, W.G.; Kendall, B.W. Variation in growth, mortality, length and age compositions of harvested populations of the herbivorous fish Girella tricuspidata. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 76, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, P.G.; Potter, I.C.; Hall, N.G. The biological characteristics of Scorpis aequipinnis (Kyphosidae), including relevant comparisons with those of other species and particularly of a heavily exploited congener. Fish. Res. 2012, 125, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, K.D.; Choat, J.H. Comparison of herbivory in the closely-related marine fish genera Girella and Kyphosus. Mar. Biol. 1997, 127, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. Herbivorous fishes. In Under Southern Seas: The Ecology of Australia’s Rocky Reefs; Andrew, N., Ed.; UNSW Press: Sydney, Australia, 1999; pp. 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, A.M.; Harvey, E.S.; Knott, N.A. Herbivore abundance, grazing rates and feeding pathways on Australian temperate reefs inside and outside marine reserves: How are things on the west coast? J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2017, 493, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.C. Population and standing crop estimates for rocky reef fishes of North-Eastern New Zealand. N. Z. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1977, 11, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.P. Ecology of rocky reef fish of north-eastern New Zealand: A review. N. Z. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1998, 22, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford, M. The distribution patterns of exploited girellid, kyphosid and sparid fishes on temperate rocky reefs in New South Wales, Australia. Fish. Sci. 2002, 68, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.; Wernberg, T.; Harvey, E.S.; Santana-Garcon, J.; Saunders, B.J. Tropical herbivores provide resilience to a climate-mediated phase shift on temperate reefs. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.A.; Haddy, J.A.; Fearman, J.; Barnes, L.M.; Macbeth, W.G.; Kendall, B.W. Reproduction, growth and connectivity among populations of Girella tricuspidata (Pisces: Girellidae). Aquat. Biol. 2012, 16, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, Y.; Furumitsu, K.; Kiriyama, T.; Yamaguchi, A. Using optimised otolith sectioning to determine the age, growth and age at sexual maturity of the herbivorous fish Kyphosus bigibbus: With a comparison to using scales. Mar. Freshw. Res 2019, 71, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, P.G. The age estimation of an extremely old Silver Drummer Kyphosus sydneyanus (Günther 1886) from southern Western Australia. Pac. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 29, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.A.; Branch, T.A.; Ranasinghe, R.A.; Essington, T.E. Old-growth fishes become scarce under fishing. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 2843–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, P.G. The life-history of Cheilodactylus rubrolabiatus from south-western Australia and comparison of biological characteristics of the Cheilodactylidae and Latridae: Support for an amalgamation of families. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 94, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trip, E.D.L.; Raubenheimer, D.; Clements, K.D.; Choat, J.H. Reproductive demography of a temperate protogynous and herbivorous fish, Odax pullus (Labridae, Odacini). Mar. Freshwat. Res. 2011, 62, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A. The Life History and Ecology of Bluefish, Girella cyanea, at Lord Howe Island. Master’s Thesis, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stocks, J.R.; Gray, C.A.; Taylor, M.D. Synchrony and variation across latitudinal gradients: The role of climate and oceanographic processes in the growth of a herbivorous fish. J. Sea Res. 2014, 90, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, J.D.; Wilcox, C.; Hall, N. How to estimate life history ratios to simplify data-poor fisheries assessment. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 80, 2619–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, D.J. Girella zebra in Fishes of Australia. 2023. Available online: https://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/470 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Chang, W.Y.B. A statistical method for evaluating the reproducibility of age determination. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1982, 39, 1208–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E. Accuracy, precision and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. J. Fish Biol. 2001, 59, 197–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Cerrato, R.M. Interpretable statistical tests for growth comparisons using parameters in the von Bertalanffy equation. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1990, 47, 1416–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.J.; Deriso, R.B. Quantitative Fish Dynamics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. 517. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenig, J.M. Empirical use of longevity data to estimate mortality. Fish. Bull. 1983, 82, 898–903. [Google Scholar]

- Then, A.Y.; Hoenig, J.M.; Hall, N.G.; Hewitt, D.A. Evaluating empirical estimators of natural mortality. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 72, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, O.S.; Cope, J.M. Development and considerations for application of a longevity-based prior for the natural mortality rate. Fish. Res. 2022, 256, 106477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alverson, D.L.; Carney, M.J. A graphic review of the growth and decay of population cohorts. J. Cons. Int. Explor. Mer. 1975, 36, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, W.E. Computation and interpretation of biological statistics of fish populations. Bull. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1975, 191, 1–382. [Google Scholar]

- Laevastu, T. Manual of Methods in Fisheries Biology; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson, P.G.; Hall, N.G.; Potter, I.C. Biological characteristics of three co-occurring species of armorhead from different genera vary markedly from previous results for the Pentacerotidae. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 89, 1393–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, D.V.; Dimmlich, W.F.; Potter, I.C. Length and age compositions and growth rates of the Australian herring Arripis georgiana in different regions. Mar. Freshw. Res 2000, 51, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford, M.J.; Underwood, A.J.; Kennelly, S.J. Humans as predators on rocky reefs in New South Wales, Australia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1991, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.L.; Bell, J.D.; Pollard, D.A.; Russell, B.C. Catch and effort of competition spearfishermen in southeastern Australia. Fish. Res. 1989, 8, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzioumis, V.; Kingsford, M.J. Reproductive biology and growth of the temperate damselfish Parma microlepis. Copeia 1999, 1999, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.R. Age, growth and spatial and interannual trends in age composition of jackass morwong, Nemadactylus macropterus, in Tasmania. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2001, 52, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, G.P.; Lyle, J.M.; Murphy, R.J.; Kalish, J.M.; Ziegler, P.E. Validation of age and growth in a long-lived temperate reef fish using otolith structure, oxytetracycline and bomb radiocarbon methods. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2007, 58, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pape, O.; Bonhommeau, S. The food limitation hypothesis for juvenile marine fish. Fish Fish. 2015, 16, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, N.; Fletcher, W.J.; Pearce, A.; Chubb, C.F. Effect of the Leeuwin Current on the recruitment of fish and invertebrates along the Western Australian coast. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1996, 47, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molony, B.W.; Newman, S.J.; Loll, L.; Lenanton, R.C.J.; Wise, B. Are Western Australian waters the least productive waters for finfish across two oceans? A review with a focus on finfish resources in the Kimberley region and North Coast Bioregion. J. R. Soc. West. Aust. 2011, 94, 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, T.M. Fish Physiology: Environmental Influences on Gonadal Activity in Fish; Hoar, W.S., Randall, D.J., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1983; pp. 65–116. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson, P.G. The life history characteristics of Neosebastes pandus and the relationship between sexually dimorphic growth and reproductive strategy among Scorpaeniformes. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 98, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, B.; Potter, I.C.; Hesp, S.A.; Coulson, P.G.; Hall, N.G. Biology of the harlequin fish Othos dentex (Serranidae), with particular emphasis on sexual pattern and other reproductive characteristics. J. Fish Biol. 2014, 84, 106–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, C.B.; Potter, I.C.; Hall, N.G.; Lenanton, R.C.J.; Hesp, S.A. Marked variations in reproductive characteristics of snapper (Chrysophrys auratus, Sparidae) and their relationship with temperature over a wide latitudinal range. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 72, 2341–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, P.G.; Hesp, S.A.; Hall, N.G.; Potter, I.C. The western blue groper (Achoerodus gouldii), a protogynous hermaphroditic labrid with exceptional longevity, late maturity, slow growth, and both late maturation and sex change. Fish. Bull. 2009, 107, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cossington, S.; Hesp, S.A.; Hall, N.G.; Potter, I.C. Growth and reproductive biology of the foxfish Bodianus frenchii, a very long-lived and monandric protogynous hermaphroditic labrid. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 77, 600–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocks, J.R.; Gray, C.A.; Taylor, M.D. Intra-population trends in the maturation and reproduction of a temperate marine herbivore Girella elevata across latitudinal clines. J. Fish Biol. 2015, 86, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenanton, R.; StJohn, J.; Keay, I.; Wakefield, C.; Jackson, G.; Wise, B.; Gaughan, D. Fisheries Research Report No. 174. Spatial Scales of Exploitation Among Populations of Demersal Scalefish: Implications for Management, Part 2: Stock Structure and Biology of Two Indicator Species, West Australian Dhufish (Glaucosoma hebraicum) and Pink Snapper (Pagrus auratus), in the West Coast Bioregion; Fisheries Research and Development Corporation on Project Number 2003/052, Final Report; Department of Fisheries: Perth, Australia, 2009; p. 189.

- McCormick, M.I. Reproductive ecology of the temperature reef fish Cheilodactylus spectabilis (Pisces: Cheilodactylidae). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1989, 55, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; Norriss, J.V.; Mackie, M.C.; Hall, N.G. Spatial variation in life history characteristics of snapper (Pagrus auratus) within Shark Bay, Western Australia. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2010, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, C.B. Annual, lunar and diel reproductive periodicity of a spawning aggregation of snapper Pagrus auratus (Sparidae) in a marine embayment on the lower west coast of Australia. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 77, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platten, J.R.; Tibbetts, I.R.; Sheaves, M.J. The influence of increased line-fishing mortality on the sex ratio and age of sex reversal of the venus tusk fish. J. Fish Biol. 2002, 60, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.L.; Caselle, J.E.; Standish, J.D.; Schroeder, D.M.; Love, M.S.; Rosales-Casian, J.A.; Sosa-Nishizaki, O. Size-selective harvesting alters life histories of a temperate sex-changing fish. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 2268–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueck, N.; Marshell, A.; Coulson, P.G.; Sharples, R.; Cresswell, K.; Tracey, S. Southern Sand Flathead Assessment 2023; Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania: Hobart, Australia, 2023; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Chong-Montenegro, C.; Craig, M.T.; Castellanos-Galindo, G.A.; Erisman, B.; Coulson, P.G.; Krumme, U.; Baos, R.; Zapata, L.; Vega, A.; Robertson, D.R. Age and growth of the Pacific goliath grouper (Epinephelus quinquefasciatus), the largest bony reef fish of the Tropical Eastern Pacific. J. Fish Biol. 2025, 107, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J. Evidence of age-class truncation in some exploited marine fish populations in New South Wales, Australia. Fish. Res. 2011, 108, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.R.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Newman, S.J.; Stapley, J.M.; Allsop, Q.; Sellin, M.J.; Welch, D.J. Spatial variation in life history reveals insight into connectivity and geographic population structure of a tropical estuarine teleost: King threadfin, Polydactylus macrochir. Fish. Res. 2012, 125, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TL∞ | k | t0 | r2 | n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined | Estimate | 360 | 0.26 | −0.35 | 0.91 | 747 |

| Upper | 364 | 0.28 | −0.25 | |||

| Lower | 357 | 0.25 | −0.48 | |||

| Females | Estimate | 354 | 0.27 | −0.26 | 0.91 | 337 |

| Upper | 359 | 0.29 | −0.10 | |||

| Lower | 350 | 0.25 | −0.44 | |||

| Males | Estimate | 365 | 0.26 | −0.41 | 0.91 | 410 |

| Upper | 370 | 0.27 | −0.26 | |||

| Lower | 360 | 0.24 | −0.60 |

| TL50 | TL95 | A50 | A95 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Estimate | 290 | 346 | 6.7 | 11.5 |

| Upper | 312 | 392 | 7.7 | 13.9 | |

| Lower | 268 | 299 | 5.8 | 9.5 | |

| Males | Estimate | 269 | 322 | 4.9 | 7.4 |

| Upper | 289 | 358 | 5.3 | 9.4 | |

| Lower | 252 | 283 | 4.4 | 6.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Coulson, P.G. Zebrafish Girella zebra (Richardson 1846): Biological Characteristics of an Unexploited Fish Population. Fishes 2026, 11, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010024

Coulson PG. Zebrafish Girella zebra (Richardson 1846): Biological Characteristics of an Unexploited Fish Population. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoulson, Peter Graham. 2026. "Zebrafish Girella zebra (Richardson 1846): Biological Characteristics of an Unexploited Fish Population" Fishes 11, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010024

APA StyleCoulson, P. G. (2026). Zebrafish Girella zebra (Richardson 1846): Biological Characteristics of an Unexploited Fish Population. Fishes, 11(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010024