Abstract

Monitoring fish skin health is essential in aquaculture, where scale loss serves as a critical indicator of fish health and welfare. However, automatic detection of scale loss regions remains challenging due to factors such as uneven underwater illumination, water turbidity, and complex background conditions. To address this issue, we constructed a scale loss dataset comprising approximately 2750 images captured under both clear above-water and complex underwater conditions, featuring over 7200 annotated targets. Various image enhancement techniques were evaluated, and the Clarity method was selected for preprocessing underwater samples to enhance feature representation. Based on the YOLOv8m architecture, we replaced the original FPN + PAN structure with a weighted bidirectional feature pyramid network to improve multi-scale feature fusion. A convolutional block attention module was incorporated into the output layers to highlight scale loss features in both channel and spatial dimensions. Additionally, a two-stage transfer learning strategy was employed, involving pretraining the model on above water data and subsequently fine-tuning it on a limited set of underwater samples to mitigate the effects of domain shift. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves a mAP50 of 96.81%, a 5.98 percentage point improvement over the baseline YOLOv8m, with Precision and Recall increased by 10.14% and 8.70%, respectively. This approach reduces false positives and false negatives, showing excellent detection accuracy and robustness in complex underwater environments, offering a practical and effective approach for early fish disease monitoring in aquaculture.

Key Contribution:

An enhanced YOLOv8m model with transfer learning and attention mechanisms was developed for fish scale loss detection under challenging underwater conditions. The method achieves higher accuracy and robustness, offering a practical and effective approach for early fish disease monitoring in aquaculture.

1. Introduction

Aquaculture has become a crucial component of global protein supply and plays a significant role in meeting human nutritional needs [1,2]. With the increasing stocking density and the widespread adoption of intensive farming systems, the health of aquatic animals has received growing attention [2]. Fish scales serve as a vital physical barrier, and when scale loss occurs, the integrity of the skin is compromised, facilitating pathogen invasion through the resulting wounds [3]. This condition also impairs osmoregulation, resulting in excessive water influx in freshwater fish and excessive water loss in marine fish, both of which lead to osmotic imbalance and energy depletion. As a clear indicator of skin damage or lesions, scale loss often serves as an early sign of bacterial infections, parasitic infestations, or water quality degradation [4]. Therefore, scale loss represents not only a superficial symptom but also a warning signal of osmotic imbalance, pathogen invasion, and metabolic disruption. If not promptly detected and appropriately managed, it may trigger a large-scale disease outbreak, resulting in substantial economic losses.

Traditional fish health monitoring primarily relies on manual observation. However, under high-density aquaculture conditions, manual inspection is labor-intensive, time-consuming, subjective, and prone to misjudgments, making it impractical for large-scale and real-time health management [5]. With rapid advancements in computer vision and deep learning, intelligent detection methods based on image recognition have emerged as promising solutions for the early diagnosis of aquaculture-related diseases. The YOLO (You Only Look Once) series of object detection algorithms, known for their high accuracy and real-time performance [6,7,8], has been widely applied in fields such as medical imaging, industrial defect detection, and animal recognition, offering robust technical support for underwater fish skin health monitoring.

Nevertheless, the underwater environment presents unique challenges for lesion detection, including unstable natural or artificial lighting causing shadows and highlights, suspended particles leading to scatter and blur, and color distortion. Scale loss regions are often small, irregularly shaped, and exhibit low contrast against the surrounding fish skin tissue, increasing the likelihood of detection omission or misclassification [9,10,11]. Moreover, the majority of current research has primarily concentrated on detecting lesions such as white spots and erythema, or on general fish body localization, while publicly available datasets and specialized algorithms for scale loss detection remain limited [12,13,14,15].

In recent years, substantial advancements have been made in real-time visual monitoring of fish skin health. Yu et al. developed an enhanced YOLOv4-based system for the online detection of four common skin diseases (septicemia, saprolegniasis, lernaea, and ciliates) in deep-sea cage environments, achieving a 12.39% improvement in mAP and a 19.31 FPS increase in inference speed over the original YOLOv4, thereby improving its practical applicability in real-world aquaculture operations [12]. Wang et al. proposed DFYOLO, an improved YOLOv5m model with grouped convolution and CBAM attention mechanisms, which elevated mAP50 from 94.52% to 99.38% in real farm environments, significantly improving detection robustness and consistency [13]. Li et al. introduced YOLO-FD, a multi-task framework combining detection and lesion segmentation, providing a direct and effective technical solution for quantitative assessment of skin abnormalities such as scale loss [14]. Huang et al. integrated YOLOv8 with behavioral features to develop an online early warning system for largemouth bass nocardiosis, demonstrating the potential of multimodal fusion in disease prediction [16]. In parallel, several studies have focused on underwater visual detection and small target fish recognition under complex aquatic environments [17,18,19]. Zhang et al. proposed an improved YOLOv8n model for fish detection in natural water environments, demonstrating enhanced performance for small targets [17]. Wang et al. introduced HRA-YOLO by integrating high-resolution feature maps and attention mechanisms to improve robustness under blur and occlusion [18]. Liu et al. developed SD-YOLOv8 for accurate fish detection in marine aquaculture scenarios [19]. Moreover, Zhang et al. proposed an improved YOLOv4-based method for underwater small-target detection by integrating SemiDSConv with the FIoU loss function [20].

While the aforementioned studies demonstrate significant progress in aquatic computer vision, they primarily address the detection of fish bodies, common diseases, or are optimized for general small objects. A distinct research gap remains for the automated detection of fish scale loss, which presents unique challenges: (i) Lesion Specificity: Scale loss manifests as small, irregular, and low-contrast regions, differing markedly from the more distinct appearances of spots or ulcers. (ii) Data Scarcity: No large-scale, publicly available benchmark dataset exists for this specific condition. (iii) Domain Adaptation Need: The pronounced domain shift between clear, controlled above-water imagery and complex, in situ underwater environments is particularly acute for subtle textures like missing scales. Existing YOLO-based underwater detectors are not explicitly designed to address this combination of subtlety and domain shift.

Therefore, accurate detection of fish scale loss can be characterized as a small object detection problem under domain shift.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a novel underwater fish scale loss detection framework. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- A dual-domain dataset for fish scale loss detection was constructed, containing ~2750 annotated images and over 7200 instances from both above-water and underwater conditions.

- An improved YOLOv8m model was developed by incorporating BiFPN for multi-scale feature fusion and CBAM to enhance attention to scale loss regions.

- A teacher–student transfer learning strategy was designed, enabling effective pre-training on above-water data and fine-tuning on limited underwater samples to reduce domain shift.

- Extensive experiments were conducted, and a mAP50 of 96.81% was achieved, demonstrating strong effectiveness and robustness for aquaculture monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Due to the lack of publicly available annotated datasets for fish scale loss, a specialized dataset was independently collected and constructed for this study. The images were captured in a culture pond at the Animal Husbandry Facility Technology Development Research Center in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China. The pond measures 3 m × 3 m, with water temperature maintained between 25 and 28 °C (Figure 1). On 10 September 2024, a camera was installed at a depth of 0.8 m to continuously record crucian carp for one week. Imaging was performed using a DJI ACTION5 PRO camera (DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), which recorded at a resolution of 3840 × 2160 pixels and a frame rate of 30 FPS, equipped with a 155° wide-angle lens. Video footage was extracted from the built-in storage card and transferred to a computer, where individual frames were sampled and processed for annotation and model training.

Figure 1.

Culture Pond Environment.

The dataset consists of two parts: an above-water image set and an underwater image set. The above water images were captured under controlled and favorable imaging conditions, in which fish were collected from the pond using nets and photographed against green and white background boards at a height of 0.2–0.8 m. This setup ensured high image clarity and minimal noise. A total of 2150 fish body images were acquired, each annotated manually to delineate regions of scale loss on the fish surface using rectangular bounding boxes labeled as “flaky”. Since some fish exhibited multiple areas of scale loss, multiple targets were annotated within a single image. Overall, the above-water dataset contains 6625 annotated scale loss instances, averaging approximately three per image.

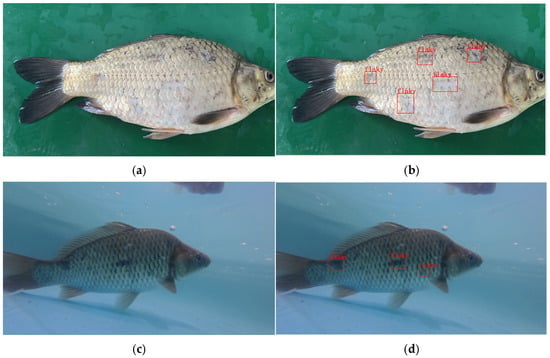

The underwater image dataset consists of 600 group images of fish, captured using a submerged camera installed in the culture pond. These images presented more challenges due to uneven lighting, interference from suspended particles, and significant color distortion. The annotation process followed the same protocol as that used for the above water dataset, with rectangular bounding boxes marking the regions of scale loss. A total of 1210 scale loss instances were annotated in the underwater image dataset, averaging two per image. Notably, the scale loss regions in these underwater images were often small in size and exhibited low contrast against surrounding tissues, which complicates both manual annotation and subsequent detection tasks. Across both datasets, scale loss manifestations exhibited considerable variability, ranging from minor abrasions that caused the loss of a few scales to severe infections or mechanical injuries causing extensive desquamation. Annotation was performed by a team of three annotators using LabelImg. To ensure consistency, a common guideline was established, and a subset of 100 images was cross-annotated. The dataset was randomly split into training (80%), validation (10%), and testing (10%) sets at the image level, separately for the above-water and underwater subsets. Representative examples of above-water and underwater images with annotations are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Representative samples from the dataset. (a) Original above-water image of a fish with visible scale loss. (b) The same image with manually annotated bounding boxes (in red) labeling ‘flaky’ regions. (c) Original underwater image showing fish in a pond environment. (d) The corresponding annotated underwater image.

2.2. Data Augmentation

To enhance the model’s robustness in complex underwater environments and increase the diversity of training samples, extensive data augmentation was performed on the underwater image dataset. Three image enhancement methods were implemented: OpenCV-based detail enhancement, the multi-scale Retinex method, and a Clarity-based sharpness enhancement algorithm. These approaches enhance underwater image quality by improving clarity, correcting color distortions, reducing noise, and restoring details [21,22]. Specifically, the OpenCV-based method used the detailEnhance function from the OpenCV library to strengthen fine-grained textures, thereby enhancing local feature discriminability and facilitating more accurate identification of subtle scale loss regions. The multi-scale Retinex method applied the Retinex theory of multi-scale retinal adaptation for color correction, effectively reducing the pervasive color cast in underwater images, improving color balance and contrast, and increasing the distinction between target features and the background. The Clarity-based algorithm utilized adaptive sharpening to enhance edge and texture information, making blurred details more distinct, particularly improving the visibility of scale edges and desquamated regions. Representative original and enhanced images are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Visual comparison of different image enhancement methods. (a) Original underwater image. (b) Result after OpenCV detail enhancement. (c) Result after Multi-scale Retinex color correction. (d) Result after Clarity-based sharpness enhancement.

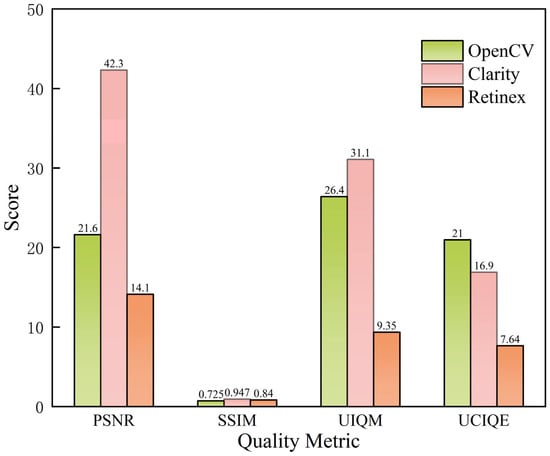

After completing the aforementioned augmentation operations, the overall performance of the three image enhancement methods was evaluated using four widely adopted image quality assessment metrics: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity index (SSIM), Underwater Image Quality Measure (UIQM), and Underwater Color Image Quality Evaluation (UCIQE) [23]. These metrics were used to comprehensively assess and compare the enhanced images, helping to determine the most suitable data augmentation strategy for this task. The results of each enhancement method are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Evaluation metrics of each enhancement method.

Based on the experimental results, the Clarity enhancement method exhibited superior performance in terms of PSNR and SSIM, achieving average values of 42.32 and 0.947, respectively. This indicates its strong effectiveness in improving image clarity and preserving structural details. The OpenCV-based detail enhancement method achieved relatively higher scores in UIQM and UCIQE, with values of 26.41 and 20.96, respectively, suggesting its effectiveness in emphasizing edge and texture information. In contrast, the Retinex enhancement method underperformed across all metrics, with UIQM and UCIQE values of only 9.35 and 7.64, respectively, due to excessive color stretching and detail loss when processing noisy underwater images. To directly evaluate the impact of preprocessing on the downstream task, we trained the baseline YOLOv8m model on the underwater dataset processed with each method. The model trained on Clarity-enhanced images achieved the highest mAP50 of 90.9%, compared to 79.3% (OpenCV), 81.9% (Retinex), and 88.1% (Original images). In summary, the Clarity method was selected as the primary preprocessing technique for subsequent stages.

2.3. Overview of YOLOv8

YOLOv8 is a state-of-the-art, single-stage object detector known for its speed and accuracy [24]. Its architecture comprises a backbone for feature extraction, a neck for multi-scale feature fusion, and a detection head. The neck typically employs a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) combined with a Path Aggregation Network (PAN). The detection head utilizes an anchor-free, decoupled design. In this work, we use YOLOv8m as our baseline and modify its components as described below.

2.4. Model Improving

2.4.1. BiFPN Feature Fusion

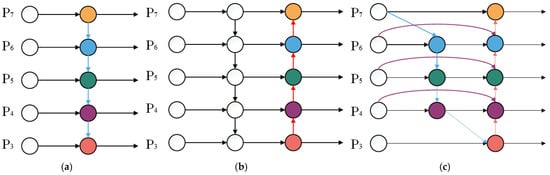

To further enhance the YOLOv8m model’s ability to detect fish scale loss regions, the original FPN + PAN feature fusion structure was replaced with a BiFPN module. Learnable weights were incorporated to enable adaptive multi-scale feature fusion, allowing the network to automatically assign importance to features from different scales. The architectural designs of FPN, FPN + PAN, and BiFPN are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Structural diagrams of various feature fusion networks: (a) FPN; (b) FPN + PAN; (c) BiFPN. Colored circles represent feature maps at different pyramid levels, while arrows indicate the directions of feature information flow and fusion across scales.

BiFPN establishes bidirectional cross-scale connections, enabling both top-down and bottom-up feature fusion, which facilitates repeated interaction between high-level semantic features and low-level detailed features [25]. During the feature fusion process, BiFPN incorporates learnable weighting coefficients to adjust the contribution of features from different scales to the final output.

The weighted fusion operation is expressed as (see [25] for details):

Here, denotes learnable non-negative weights, is the i-th input feature map, and ε is a small constant.

In this study, the original neck feature fusion module of YOLOv8 was replaced with BiFPN, which operates in conjunction with the subsequently introduced attention mechanism. This modification enables the improved YOLOv8 to more effectively integrate multi-scale information. Under complex underwater imaging conditions, the incorporation of BiFPN facilitates superior capture of fish scale details and edge information, thereby enhancing the model’s sensitivity and detection accuracy for scale loss targets.

2.4.2. Convolutional Block Attention Module

To enhance the model’s ability to focus on local-scale loss features of fish bodies, a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) was embedded into key layers of the feature fusion structure [26]. CBAM is a lightweight channel–spatial attention mechanism that sequentially generates channel attention and spatial attention maps for a given intermediate feature representation. The channel attention map is computed using global average and max pooling, followed by a shared MLP. The spatial attention map is computed by applying average and max pooling along the channel dimension, followed by a convolution. The final output F″ is obtained by sequentially applying the attention maps: , where denotes element-wise multiplication. For complete formulations, refer to the original paper [26].

The integration of CBAM into the model effectively enhances its ability to capture scale loss features. In this study, the CBAM was embedded into key layers of the feature fusion network, allowing the attention mechanism to work in conjunction with BiFPN.

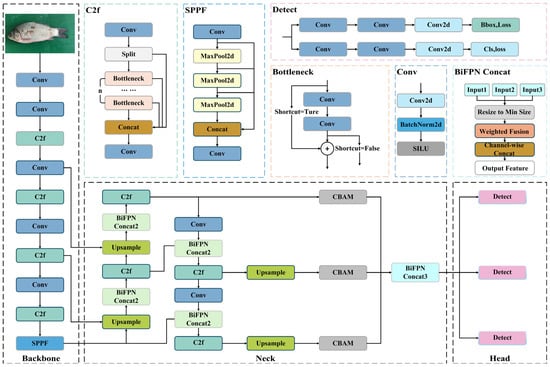

2.4.3. Improved YOLOv8 Model

The original FPN + PAN structure in the YOLOv8 neck was redesigned into a BiFPN module, while preserving the multi-scale features extracted by the backbone. Through bidirectional cross-scale connections, BiFPN performs cross-scale fusion of the P3, P4, and P5 feature maps, enabling more effective information flow and enhanced feature refinement. Prior to being fed into the detection head, each BiFPN output feature map is processed by an embedded CBAM. By combining channel and spatial attention, CBAM suppresses background interference and highlights fish scale loss regions, thereby improving detection accuracy and robustness. With these structural optimizations, the model better exploits both high-level semantic information and fine-grained visual details in the images, thereby enhancing its ability to detect fish scale loss regions under complex underwater conditions. An overview of the modified YOLOv8 architecture is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The improved YOLOv8 architecture.

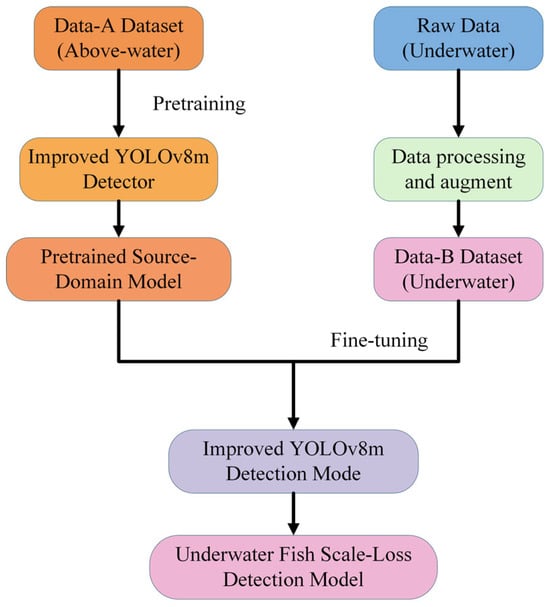

2.5. Training Procedure and Transfer Learning Approach

A two-stage transfer learning pipeline was established to bridge the gap between the above-water and underwater domains to address the challenges of limited underwater training samples and domain discrepancies, which often lead to slow convergence and overfitting [27,28,29]. To fully leverage source domain knowledge, the improved YOLOv8 model was first pretrained on the above water image dataset. These pretrained weights were then transferred to the underwater image dataset for fine-tuning. This approach enables knowledge acquired in the source domain to be efficiently adapted to the target domain, thereby enhancing detection performance under low data regimes in underwater environments.

During the fine-tuning stage, the backbone feature extraction layers, including the BiFPN module, were frozen, and only the neck and detection head were trained. The learning rate was reduced to 0.0001 to ensure a stable transfer process and prevent drastic updates to pretrained features. To further improve generalization, both online data augmentation (including random flipping, mosaic augmentation, affine transformations) and offline augmentation (comprising brightness perturbation, color shifting, blurring) were applied, increasing the diversity of underwater samples and enhancing robustness to varying image distributions. Additionally, an early stopping mechanism was employed to monitor validation performance and terminate training if accuracy showed no improvement over successive epochs. The overall training and transfer learning workflow is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The overall training and transfer learning process.

2.6. Implementation Details

The model was implemented in PyTorch 2.4.1. We used the default YOLOv8 loss function, which is a weighted sum of bounding box regression loss (CIoU), distribution focal loss for classification, and a binary cross-entropy loss for objectness. The input image size was fixed at 640 × 640. During training, mosaic augmentation (probability = 0.5), random horizontal flip (probability = 0.5), and color space adjustments were applied. The optimizer was SGD with an initial learning rate of 0.01, momentum of 0.937, and weight decay of 0.0005. A cosine annealing scheduler was used. For inference, the confidence threshold was set to 0.25 and the Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) IoU threshold was set to 0.45. These hyperparameters were kept consistent across all compared models.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Environment and Conditions

All YOLOv8 baseline and improved models were implemented using the PyTorch deep learning framework. The detailed hardware and software configurations are summarized in Table 1. Training and testing were conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel i9-13900K CPU (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPU (Santa Clara, CA, USA), running Windows 11 with CUDA 12.1. The software environment was based on PyTorch 2.4.1 and Python 3.8.20. For training, the batch size was set to 8, and the number of training epochs was fixed at 100. To ensure a deterministic and directly comparable evaluation across all models, a fixed random seed was used for all experiments.

Table 1.

Training environment parameters.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance, common object detection metrics were adopted, including Precision (P), Recall (R), and mean Average Precision (mAP). The formulas are defined as follows Equations (1)–(3):

where denotes the number of true positives, i.e., samples correctly identified as belonging to the positive class, and denotes the number of false positives, referring to negative samples that are incorrectly classified as positive.

where represents the number of false negatives, referring to positive samples that are incorrectly classified as negative.

Based on the precision and recall values, a Precision–Recall (P–R) curve can be constructed to compute the Average Precision (AP). Since the detection task in this study involves only a single class, the mAP is equivalent to AP. The AP is calculated as:

where mAP denotes the mean Average Precision, AP represents the average precision for a single class, P(R) is the precision as a function of recall, and R denotes the recall value ranging from 0 to 1.

3.3. Ablation Study and Results

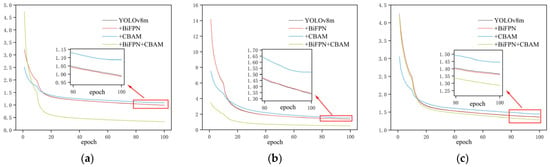

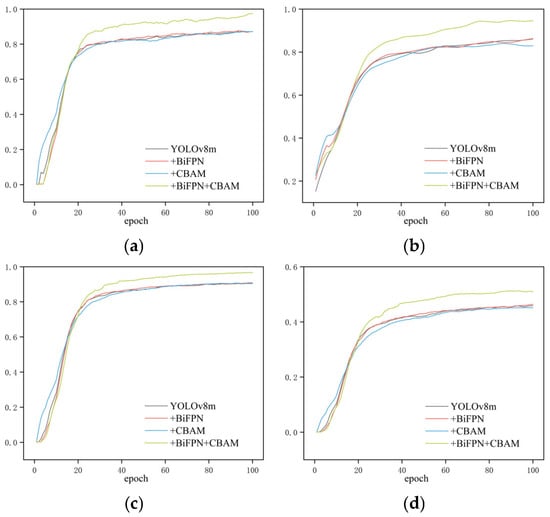

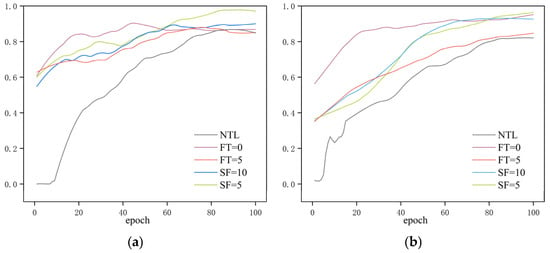

To assess the individual contributions of the proposed modules to detection performance, four groups of ablation studies were conducted: the baseline YOLOv8m, the model with BiFPN only, the model incorporating only CBAM, and the combined model integrating both BiFPN and CBAM. All models were trained and evaluated using identical datasets and training conditions to ensure fairness. The training loss curves and performance metric curves are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively, while the detailed quantitative results are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 8.

Loss function curves of the ablation study during training: (a) Bounding box loss; (b) Classification loss; (c) Distribution focal loss.

Figure 9.

Evaluation metric curves of the ablation study during training: (a) Precision; (b) Recall; (c) mAP50; (d) mAP50:95.

Table 2.

The results of the ablation experiment.

As shown in Table 2, the introduction of the BiFPN and CBAM improved the model’s performance, with their combination achieving the most significant enhancement. Specifically, compared to the baseline YOLOv8m, incorporating BiFPN alone resulted in a nearly unchanged Precision, while Recall increased slightly from 85.8% to 86.0%, and mAP50 remained almost stable. This indicates that the multi-scale feature fusion of BiFPN had a marginal positive effect, slightly improving localization accuracy but contributing only limited gains likely because YOLOv8m already employs an efficient feature fusion architecture. In contrast, using CBAM alone preserves precision but reduces recall from 85.8% to 82.9%, leading to a minor decrease in mAP50 from 90.8% to 90.4%. This suggests that the channel–spatial attention mechanism in isolation did not improve detection and may cause the model to over attend to the local features, resulting in missed detections.

When BiFPN and CBAM were jointly integrated, the model achieved substantial improvements: precision increased from 87.1% to 97.5%, recall from 85.8% to 94.8%, and mAP50 from 90.8% to 96.6%. These results demonstrate the strong synergistic effect of the two modules BiFPN enhanced the multi-scale feature representation by facilitating cross-level feature fusion, while CBAM dynamically assigned attention weights to these features, guiding the model to focus on scale loss regions of the fish body and suppress irrelevant background noise. Their integration effectively reduced both false negatives and false positives simultaneously, thereby enhancing both detection accuracy and localization precision [26,30,31]. The ablation results reveal a strong synergistic effect. Their combination creates a stable and effective pipeline: BiFPN builds a rich, multi-resolution feature pyramid, and CBAM subsequently acts as a dynamic feature selector within this pyramid. This underscores the importance of co-designing feature fusion and attention mechanisms for complex fine-grained detection tasks.

Overall, the improved model achieved a precision of 97.5% and a recall of 94.8%, representing gains of approximately 10 and 9 percentage points compared to the baseline, demonstrating its enhanced capability to accurately and comprehensively detect underwater fish scale loss regions.

3.4. Comparative Experiments and Results with Mainstream Models

The preceding section presented an analysis of the improved YOLOv8m model, with experimental results demonstrating its high detection accuracy for fish scale loss. To enable a more comprehensive evaluation, the proposed model was compared with the original YOLOv8m baseline and other state-of-the-art object detection models. It is acknowledged that the incorporation of BiFPN and CBAM introduces additional parameters and computational overhead. While a detailed analysis of efficiency metrics is beyond the primary scope of this accuracy-focused comparison, the observed substantial improvement in mAP50 justifies this cost for the critical application of early disease detection. The model remains suitable for real-time analysis. The comparison results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

A Comparative Analysis of the Performance of Different Object Detection Models.

As shown in Table 3, the classical SSD and Faster R-CNN models achieved relatively high precision values of 91.47% and 91.49%, respectively. However, their recall rates were notably low, indicating a higher rate of missed detections in complex underwater environments. In particular, the insufficient recall of Faster R-CNN resulted in an mAP50 of only 72.75%. In contrast, the YOLO series models maintained high recall while improving overall detection performance. Specifically, YOLOv8m achieved a recall of 86.14% and an mAP50 of 90.83%, significantly outperforming the two conventional detection methods. YOLOv10m and YOLOv11m further increased recall to 85.10% and 88.04%, with corresponding mAP50 values of 90.72% and 92.25%, respectively, demonstrating the advantages of the improved network architectures in feature extraction and multi-scale detection. Nevertheless, YOLOv8m exhibited slightly higher recall than YOLOv10m, suggesting that differences in detection strategies among model versions may influence performance on specific tasks.

Compared with the aforementioned methods, the proposed YOLOv8m + BiFPN + CBAM model achieved the highest performance across all three core metrics. Specifically, precision reached 97.47%, representing an improvement of 9.12 percentage points over YOLOv11m; recall increased to 94.84%, with a gain of 6.80 percentage points; and mAP50 rose to 96.81%, reflecting a 4.56 percentage point enhancement. These results demonstrate that the incorporation of BiFPN based feature fusion and the CBAM attention mechanism effectively reduced both missed and false detections, while also significantly enhancing localization accuracy. Overall, although traditional methods excelled in precision, they were prone to missed detections in complex backgrounds and low-contrast underwater images. The YOLO series methods provided a more balanced trade-off in terms of recall and mAP, while the proposed approach significantly outperformed all comparison models in precision, recall, and mAP50, confirming its effectiveness and robustness for detecting fish scale loss in underwater environments.

3.5. Analysis of Transfer Learning Experimental Results

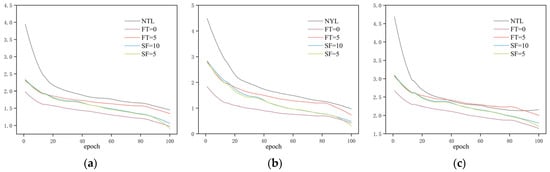

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed two-stage transfer learning strategy and to build upon the best model from the ablation study (YOLOv8m + BiFPN + CBAM), we compared different fine-tuning approaches using this improved architecture as the base model., five different training strategies were designed:

(1) No Transfer Learning (NTL): the model is trained from scratch without using any pretrained weights. (2) Fine-tuning = 0 (FT = 0): pretrained weights are utilized, and all network layers are fine-tuned during training. (3) Fine-tuning = 5 (FT = 5): pretrained weights are applied, with the initial part of the backbone frozen and the final five layers fine-tuned. (4) Stage-wise Freezing = 10 (SF = 10): the first ten layers of the backbone are initially frozen and progressively unfrozen during training. (5) Stage-wise Freezing = 5 (SF = 5): the first five layers of the backbone are initially frozen, followed by a staged unfreezing strategy [13,14,15,30,32].

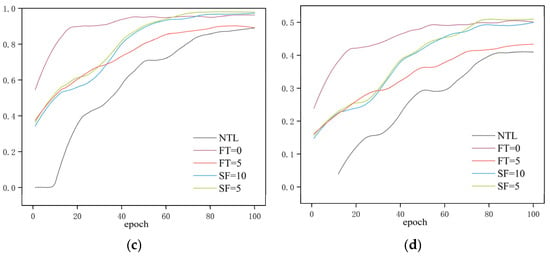

All models were trained and evaluated under identical datasets and training conditions. Variations in the loss functions and evaluation metrics during training are shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, while the detailed experimental results are provided in Table 4.

Figure 10.

Loss curves during transfer learning training. (a) Bounding box loss; (b) Classification loss; (c) Distribution focal loss.

Figure 11.

Evaluation metric curves during the transfer learning training process. (a) Precision; (b) Recall; (c) mAP50; (d) mAP50:95.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different transfer learning strategies.

As shown in Table 4, all models employing transfer learning strategies significantly outperformed the baseline model trained without transfer learning across all evaluation metrics. Specifically, the baseline model achieved only 88.1% mAP50 on the underwater dataset. In contrast, transfer learning led to substantial improvements: full fine-tuning and stage-wise unfreezing with the first 10 backbone layers frozen achieved 96.1% and 97.1% mAP50, respectively. The highest performance was achieved with stage-wise unfreezing starting from the first five frozen backbone layers, reaching 98.1% mAP50. These results demonstrate that features learned in the source domain can significantly enhance detection performance in the target domain.

Among the various transfer learning strategies, the full fine-tuning model demonstrated strong performance in key metrics such as mAP and Recall, improving mAP50 by approximately 1.3 percentage points compared to the partial freezing strategies. This suggests that allowing the backbone network to further adapt to the characteristics of underwater images during transfer contributes to higher detection accuracy. Meanwhile, the stage-wise unfreezing strategy with the first five frozen backbone layers achieved the highest overall performance, suggesting that a balanced approach involving moderate parameter freezing followed by progressive unfreezing helps preserve training stability while optimizing the transfer learning efficacy. In summary, whether all parameters are fine-tuned or not, transfer learning strategies effectively improve both precision and recall in the underwater scale loss detection task, validating the effectiveness and generalizability of the proposed approach. In particular, transfer learning models exhibit enhanced robustness under conditions of limited sample size or suboptimal image quality, highlighting their adaptability in challenging data environments.

3.6. Visualization Analysis

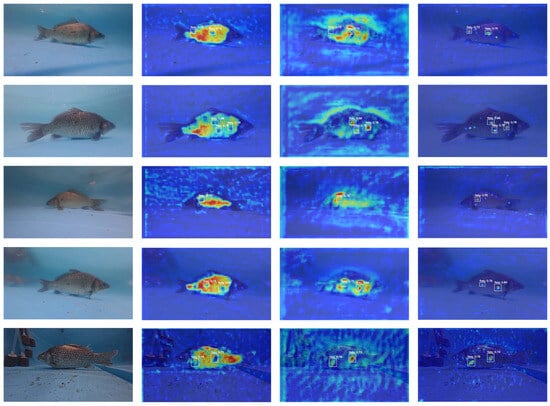

To intuitively demonstrate the detection performance of the proposed method in complex underwater environments and to interpret the model’s decision making process, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was employed to visualize the discriminative features learned by the improved model [32]. Several representative underwater samples were selected, including scenes with uneven illumination, suspended particles, and background interference, with visualizations for the “flaky” class presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Grad-CAM visualizations for the ‘flaky’ class at different network depths. For each sample, from left to right: Original image; activation heatmap from a shallow backbone layer (P5); heatmap from an intermediate layer after BiFPN fusion (P15); heatmap from a deep layer near the detection head (P28). Warmer colors (red) indicate higher relevance to the model’s detection decision.

Grad-CAM heatmaps were extracted from three semantic levels: a shallow layer in the backbone (5th layer), an intermediate layer following BiFPN fusion (15th layer), and a deep layer near the detection head (28th layer). Each set of images is arranged from left to right as follows: the original image, the P5 heatmap, the P15 heatmap, and the P28 heatmap. The colormap range from blue to red, representing increasing contribution strength to the current detection outcome.

As shown in Figure 12, the shallow-layer heatmaps exhibit scattered responses, with high activations unrelated to the flaky target, indicating that at low-level feature stages, the model primarily focuses on global textures and background noise. In the intermediate layer, the responses begin to concentrate around the flaky regions and their immediate surroundings, while irrelevant background responses are suppressed, suggesting that the multi-scale features fused by BiFPN enhance the model’s attention to lesion areas. At the deep layer, the responses are clearly concentrated on the flaking edges within the predicted bounding boxes, with minimal activation outside. This observation demonstrates that the incorporation of BiFPN multi-scale fusion and the CBAM attention module effectively guides the network from capturing global textures to focusing on lesion regions, ensuring accurate detection of fish scale loss.

4. Discussion

The experimental results clearly demonstrate that the proposed improvement strategies significantly enhance the YOLOv8 model’s performance in underwater fish scale loss detection.

To address the challenges posed by the small size, diverse morphology, and significant environmental interference of underwater scale loss targets, this study incorporated BiFPN and CBAM into the YOLOv8m model. BiFPN enables bidirectional cross-layer connections and learnable weights, promoting comprehensive interaction among multi-resolution features. This enhancement preserves high-level semantic information while reinforcing low-level details, thereby significantly improving sensitivity to small targets and fine-grained textures. CBAM, in contrast, applies adaptive weighting to the feature map through both channel and spatial attention modules, effectively suppressing background noise and highlighting key information such as scale edges and variations. In the ablation study, adding either BiFPN or CBAM alone improved accuracy, but the effect was limited. When both modules were combined, however, precision and recall increased by approximately 10 and 9 percentage points, respectively, and mAP50 rose from 90.8% to 96.8%. The combination of BiFPN and CBAM proved to be particularly effective. BiFPN ensures robust multi-scale feature representations are available, while CBAM acts as a dynamic filter on these representations, selectively amplifying features correlated with scale loss patterns and suppressing irrelevant underwater noise. This synergistic design is a key methodological insight for adapting general-purpose detectors to this specific fine-grained detection task.

To mitigate the challenges of limited underwater samples and domain shift, this study proposes a two-stage transfer learning framework. The model is pretrained on a large-scale fish scale loss dataset from the above water domain, and its weights are transferred to the student model for the underwater domain. Only the neck and detection head layers are fine-tuned. This strategy effectively leverages the scale texture features learned from high-quality above-water images, facilitating rapid model convergence even with a small underwater dataset. Experimental results show that transfer learning strategies, such as full parameter fine-tuning and stage-wise freezing, significantly improve detection accuracy. Among these, freezing the first five layers and progressively unfreezing them achieved the highest mAP50 of 98.1%, a 10-percentage-point improvement over the model without transfer learning. The effectiveness of transfer learning suggests that the visual patterns of fish scale loss exhibit minimal cross-domain discrepancy, and appropriately utilizing source domain knowledge can compensate for the lack of target domain samples.

Furthermore, various enhancement methods were applied for underwater image preprocessing, including Clarity sharpening, Retinex-based color correction, and OpenCV-based detail enhancement. The performance of these methods was evaluated and compared using metrics such as PSNR, SSIM, UIQM, and UCIQE. The results show that Clarity enhancement performed best in terms of SSIM and PSNR, and also achieved high scores in UIQM and UCIQE. As a result, Clarity was selected as the primary enhancement method. Experimental verification demonstrates that moderate sharpening enhances scale texture and reduces color distortion, improving the model’s ability to detect scale loss targets. On the other hand, excessive enhancement, such as multi-scale Retinex, may introduce color oversaturation and increased noise, ultimately degrading detection accuracy.

A comparison was made with mainstream detection models, including SSD, Faster R-CNN, YOLOv10m, and YOLOv11m. The classic SSD and Faster R-CNN models performed well in precision but had lower recall, leading to missed detections. YOLO based methods strike a good balance between real-time performance and accuracy. The proposed improved model achieved an mAP50 of 96.81%, significantly outperforming other models. At the same time, the improved model maintains an acceptable inference speed and parameter count, fulfilling real-time detection requirements. Therefore, the proposed method provides an effective solution for real-time fish disease monitoring in the aquaculture sector.

Although the improved model has shown promising results, several limitations remain to be addressed. First, the scale and diversity of the underwater dataset are limited. The samples were collected from a single aquaculture pond environment, which may not fully represent the variability in water turbidity, lighting conditions, background structures, or fish species found in global aquaculture. Consequently, while the model shows high performance on our test set, its generalization capability to significantly different environments requires further validation with more diverse data. Second, in extremely turbid water or poor lighting conditions, the texture of the scale loss area becomes nearly invisible, and even with enhancement techniques, detection performance degrades, increasing the risk of missed detections. Third, the current model uses rectangular bounding boxes to locate the scale loss areas, making it difficult to accurately quantify the area and shape of the scale loss. Furthermore, for deployment as a continuous monitoring system, several additional processing steps are required beyond single-frame detection. A critical challenge is to avoid repeatedly counting the same scale loss area on a fish as it moves across consecutive video frames. This would necessitate integrating object tracking algorithms to maintain the identity of individual fish and their associated lesions over time.

Future improvements can be made in the following directions:

- (1)

- Construct a larger and more diverse underwater fish disease dataset by incorporating data from various aquaculture systems and multiple fish species, and combining it with publicly available datasets to enhance the model’s generalization ability.

- (2)

- Explore more efficient feature extraction modules, such as pyramid convolutions, dynamic convolutions, and lightweight attention mechanisms, to further improve detection accuracy and speed.

- (3)

- Integrate instance segmentation and keypoint detection techniques to achieve precise contour extraction and area measurement of scale loss regions, providing reliable quantitative data for fish disease diagnosis.

- (4)

- Bridges the domain gap by introducing strategies like adversarial domain adaptation or meta learning to minimize the impact of varying imaging conditions across diverse aquatic environments.

- (5)

- Develop an integrated pipeline combining our robust detector with multi-object tracking and temporal analysis modules to provide actionable, fish-level health reports.

Additionally, the proposed method could be deployed on underwater robots platforms or mobile devices to assess its stability and practicality in real-world aquaculture environments.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the critical issue of underwater fish scale loss detection by proposing an automated detection method that integrates an improved YOLOv8m model with a two-stage transfer learning strategy. A fish scale loss dataset, covering both underwater and above water domains, was collected and annotated. To address the degradation of underwater image quality, enhancement methods such as OpenCV-based processing, Retinex color correction, and Clarity sharpening were employed, with the optimal enhancement method selected based on evaluation metrics including PSNR, SSIM, UIQM, and UCIQE, and a direct detection performance evaluation. The YOLOv8m model was enhanced by incorporating two modules: BiFPN, which facilitates bidirectional fusion of multi-scale features, and CBAM, which emphasizes scale loss features through channel and spatial attention, significantly improving precision and robustness in small target detection. After evaluating various indicators, the enhancement strategy was further optimized. A two-stage transfer learning framework was designed to transfer knowledge from the large-scale above-water domain to a limited underwater target domain, addressing domain differences and overfitting issues, while improving training results with limited underwater samples.

Experiments on a self-constructed dataset demonstrated that the improved model achieved an mAP50 of 96.81%, with Precision and Recall increasing to 97.47% and 94.84%, respectively, significantly outperforming the baseline YOLOv8m and other mainstream models. These results validate the effectiveness and practical value of the proposed method. Furthermore, the transfer learning strategy further enhanced the model’s performance under small sample conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y. and X.H.; methodology, Q.W. and X.Y.; software, Q.W. and X.P.; validation, Q.W., Z.Y. and X.P.; formal analysis, Q.W. and X.P.; investigation, Q.W.; resources, X.H. and R.L.; data curation, Q.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.W.; writing—review and editing, X.Y. and X.H.; visualization, Q.W.; supervision, X.Y. and X.H.; project administration, X.Y. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the corresponding author’s institution.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experiments in this article do not involve biological experiments. The experimental materials used in the paper are all from the recording of aquaculture by cameras, and computer vision technology is used for some possible analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during this study is not publicly available due to ongoing proprietary research collaborations but is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request for academic and research purposes.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the experimental site and material support provided by the Engineering Research Center of Animal Husbandry Facility Technology Exploitation. During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT(OpenAI, GPT-4o) in order to improve language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lagno, A.G.; Lara, M.; Cornejo, J. Aquatic Animal Health: History, Present and Future. OIE Rev. Sci. Tech. 2024, Special Edition, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.; Haukenes, A. The Role of Stress in Fish Disease; Southern Regional Aquaculture Center: Stoneville, MS, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Francis-Floyd, R. Stress-Its Role in Fish Disease; Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf Rather, M.; Ahmad, I.; Shah, A.; Ahmad Hajam, Y.; Amin, A.; Khursheed, S.; Ahmad, I.; Rasool, S. Exploring Opportunities of Artificial Intelligence in Aquaculture to Meet Increasing Food Demand. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; pp. 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.W.; Eom, I.K. Underwater Image Enhancement Using Adaptive Standardization and Normalization Networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sun, J.; Zhang, W.; Lin, Z. Multi-View Underwater Image Enhancement Method via Embedded Fusion Mechanism. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 121, 105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, J.; Liang, W.; Wang, D.; Zhao, J.; Xia, X. Underwater Image Quality Assessment. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2023, 40, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, A.; Wan, R. Detection and Identification of Fish Skin Health Status Referring to Four Common Diseases Based on Improved YOLOv4 Model. Fishes 2023, 8, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Wen, L.; Zhao, W. Diseased Fish Detection in the Underwater Environment Using an Improved YOLOV5 Network for Intensive Aquaculture. Fishes 2023, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Chen, C.; Cui, H.; Li, D.; Zhao, R. YOLO-FD: An Accurate Fish Disease Detection Method Based on Multi-Task Learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 258, 125085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wu, M.; Zhu, X.; Qin, Q.; Wang, S.; Ye, H.; Guo, K.; Wu, C.; Shi, Y. Real-Time Detection and Identification of Fish Skin Health in the Underwater Environment Based on Improved YOLOv10 Model. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 42, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Cui, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Qu, K.; Cui, H. Early Warning System for Nocardiosis in Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Based on Multimodal Information Fusion. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qu, Y.; Wang, T.; Rao, Y.; Jiang, D.; Li, S.; Wang, Y. An Improved YOLOv8n Used for Fish Detection in Natural Water Environments. Animals 2024, 14, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, H. HRA-YOLO: An Effective Detection Model for Underwater Fish. Electronics 2024, 13, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, R.; Hou, M.; Zhang, C.; Hu, J.; Wu, Y. SD-YOLOv8: An Accurate Seriola Dumerili Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOv8. Sensors 2024, 24, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Tan, J.; Xue, X. Underwater Target Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv4 with SemiDSConv and FIoU Loss Function. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1153416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhou, T. Multi-Scale Fusion Framework via Retinex and Transmittance Optimization for Underwater Image Enhancement. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogireddy, Y.R.; Gogireddy, J.R. Advanced Underwater Image Quality Enhancement via Hybrid Super-Resolution Convolutional Neural Networks and Multi-Scale Retinex-Based Defogging Techniques. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.14285. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, W. No-Reference Quality Assessment of Underwater Image Enhancement. Displays 2024, 81, 102586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics. YOLOv8. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 10778–10787. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Oza, P.; Sindagi, V.A.; Vs, V.; Patel, V.M. Unsupervised Domain Adaptation of Object Detectors: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 46, 4018–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Y. Scale-Consistent and Temporally Ensembled Unsupervised Domain Adaptation for Object Detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiano, M.; Martina, S.; Giannelli, C.; Caruso, F. Transfer Learning with Generative Models for Object Detection on Limited Datasets. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2024, 5, 035041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.