Abstract

Against the backdrop of the continuous expansion of the global aquaculture industry and the growing demand for high-quality feed protein, the development of sustainable alternative protein sources to fishmeal is crucial. Cottonseed protein, particularly cottonseed protein concentrate, has emerged as a highly promising plant-based alternative raw material due to its high protein content and cost advantages. This review systematically evaluates the application effects, challenges, and mechanisms of action of cottonseed protein in fish feed. Core analysis indicates that the primary limiting factor of cottonseed protein is the antinutritional factor free gossypol. High-level replacement (typically >30%) of fishmeal can inhibit fish growth, reduce protein deposition, and impair intestinal health. These adverse effects are closely associated with the downregulation of the hepatic mTOR signaling pathway—a central regulator of protein synthesis and cell growth—shifting the organism’s energy allocation from growth to stress adaptation. Furthermore, the unique fatty acid profile of cottonseed protein may exacerbate energy metabolism imbalance. To overcome gossypol toxicity, physical, chemical, and biological detoxification technologies have been widely applied. Among these, biological methods (such as Bacillus subtilis fermentation and CotA laccase-catalyzed degradation) are particularly outstanding, not only efficiently removing gossypol (removal rate > 90%) but also degrading macromolecular proteins into more digestible and absorbable small peptides and amino acids, significantly enhancing the nutritional value of cottonseed protein. Although the application prospects for cottonseed protein are broad, gaps remain in current research, particularly concerning the deeper metabolic pathways, nutrient utilization efficiency, and long-term impacts on metabolic homeostasis of detoxified cottonseed protein in fish. Future research needs to employ molecular nutrition and multi-omics technologies to elucidate its metabolic mechanisms and optimize detoxification processes and precision feeding strategies. Glandless cottonseed varieties, which fundamentally address the gossypol issue, are considered the most transformative development direction. Through continuous technological innovation, cottonseed protein is expected to become a core feed protein ingredient promoting the sustainable development of the global aquaculture industry.

Key Contribution:

This review highlights the potential of cottonseed protein as a sustainable aquaculture feed ingredient by assessing its nutritional benefits. It further identifies strategies to overcome gossypol-related limitations; outlining a path toward its safe and effective application.

1. Introduction

The global aquaculture industry is experiencing rapid expansion and has become a key pillar for ensuring global food security and nutrition [1,2] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), aquaculture production has continued to rise in recent years, driving a sharp increase in the demand for high-quality feed protein [3]. In traditional aquafeed formulations, fishmeal has long served as the primary protein source due to its balanced amino acid profile and high digestibility [4,5]. However, the scarcity of fishmeal resources has become increasingly evident. Price volatility and ecological pressures associated with overfishing of fishmeal raw materials collectively pose challenges to the sustainability of conventional protein sources, constraining the sustainable development of aquaculture [3]. Against this backdrop, the development of cost-effective, widely available, and nutritionally favorable fishmeal alternatives has emerged as a critical research direction in the field of aquafeed.

Among numerous plant protein candidates, cottonseed protein exhibits particularly prominent advantages. Prior to addressing feed protein sources, three key concepts are defined as follows (see Table 1):

Table 1.

Comparison of main definitions and characteristics of cottonseed-derived protein products and aquafeed.

As shown in Table 1, cottonseed meal (CSM), cottonseed protein (CSP) and cottonseed protein concentrate (CPC) represent a series of products with progressively higher protein purity and lower levels of anti-nutritional factors, derived from the processing of cottonseed [13]. CSM is the initial by-product after oil extraction, typically containing 40–50% crude protein and significant amounts of free gossypol [14]. CSP is produced through further physical or chemical processing of CSM to remove a portion of the gossypol and carbohydrates, resulting in a protein content of 50–60% [15]. CPC undergoes more advanced solvent extraction and processing, achieving the highest protein concentration of 60–65% and the lowest free gossypol content among the three, making it the most refined and nutritionally superior product for animal feed [16].

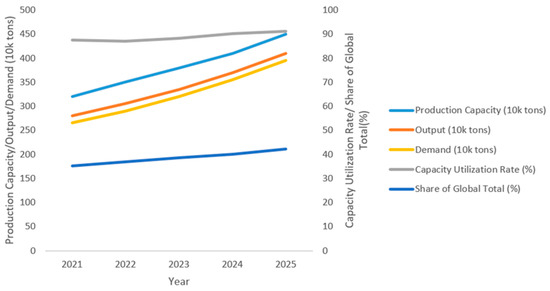

The dual-axis line chart depicts the development trend of China’s cottonseed protein industry from 2021 to 2025. According to the Figure 1, cottonseed protein production capacity, output, and demand all show steady, continuous growth, reflecting the industry’s rapid expansion. Concurrently, capacity utilization has remained above 87% (a high level), directly indicating strong market demand and efficient production operations. Notably, China’s share of global cottonseed protein output has steadily increased, underscoring its growing strategic significance in the global supply chain.

Figure 1.

The data for this line chart is sourced from “Cottonseed Protein Market Report 2025—Global and Chinese Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis” (Prof-Research, a global professional market research platform) and the “China Agricultural Products Processing Industry Development Report” (Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, CAAS, updated annually with cottonseed protein segment data), illustrating the development trends of China’s cottonseed protein industry from 2021 to 2025.

This growth is primarily driven by two key factors: first, strong demand from the aquafeed industry for sustainable fishmeal alternatives [17]; second, advancements in processing technologies—particularly the widespread adoption of low-free-gossypol products such as cottonseed protein concentrate—which have effectively mitigated the antinutritional factor gossypol, markedly improving the safety and applicability of cottonseed protein in feed formulations [18].

In summary, cottonseed protein has been established as a reliable fishmeal substitute, and its industrial chain—both in China and globally—is transitioning into a more mature, large-scale development phase.

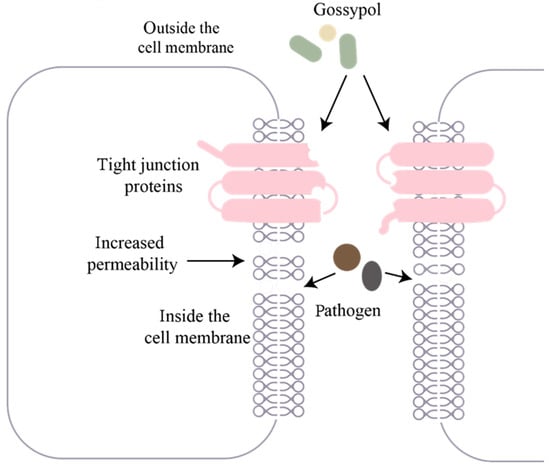

Despite the broad application prospects of cottonseed protein, it still exerts certain adverse effects on fish. As illustrated in the figure, gossypol can disrupt the tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-1, Occludin) between fish intestinal epithelial cells, leading to increased intercellular gaps and abnormal elevation of intestinal permeability [19]. Disruption of this physical barrier allows harmful substances such as pathogens and toxins in the intestinal lumen to more easily cross the intestinal barrier and enter the body, thereby triggering infections and systemic inflammatory responses [20,21,22,23,24].

Currently, there are still some limitations in research on cottonseed protein. Firstly, there are significant species-specific differences in the tolerance of different fish species to cottonseed protein; for instance, herbivorous and carnivorous fish exhibit marked variations in their tolerance to antinutritional factors in cottonseed protein [25], yet the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying these differences have not been clearly elucidated. Secondly, natural antinutritional factors in cottonseed protein, such as gossypol and phytic acid, exert adverse effects on fish growth, intestinal health, and nutrient metabolism. Currently [26], there is a lack of systematic and in-depth investigation into efficient removal technologies for these antinutritional factors and strategies to mitigate their negative impacts. Thirdly, the molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying the effects of cottonseed protein on fish nutrient metabolism—such as digestive enzyme activity and amino acid transporter expression in protein metabolism, as well as the regulation of genes related to lipid synthesis and decomposition in lipid metabolism—have not been thoroughly analyzed [27]. The existence of these research gaps poses multiple challenges to the application of cottonseed protein in aquafeeds, while also pointing out directions for future studies. Therefore, systematically summarizing the effects of cottonseed protein on fish growth and nutrient metabolism not only helps promote the diversification of protein sources in aquafeeds but also provides solid theoretical support for the efficient and safe utilization of cottonseed protein—this is the core value of this review.

Free gossypol is the primary antinutritional factor limiting the application of cottonseed protein. Besides its well-documented adverse effects on growth performance, intestinal health, and energy metabolism (which will be the focus of this review), its metabolic fate in the organism—particularly the processes of accumulation, metabolism in the liver, and excretion via bile—is considered the basis of its core toxic mechanism. However, since this review primarily focuses on the metabolic and physiological effects of cottonseed protein as an integral nutritional source, the detailed pharmacokinetics and hepatotoxic mechanisms of gossypol in fish remain to be further elucidated by future studies. Additionally, defining the precise safe inclusion levels of free gossypol (mg/kg) in diets for different fish species will be crucial for promoting the safe application of cottonseed protein.

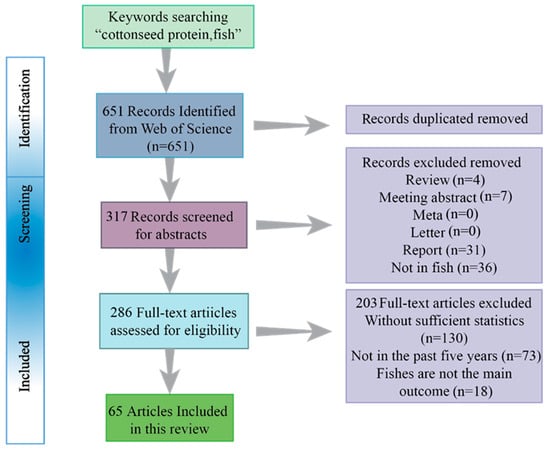

We established a meta-analysis dataset (Figure 2) to systematically assess the current understanding of cottonseed protein replacement effects in fish. Literature was retrieved from Web of Science and PubMed, with the figure illustrating the numbers of records identified and retained through the screening process. Inclusion required studies to focus specifically on cottonseed protein in fish, thus excluding monographs, reviews, and research on non-fish species. Furthermore, studies that only superficially mentioned cottonseed protein without providing substantial supporting data (e.g., adequate sample size or variance measures) were categorized as “unqualified” and excluded [28]. A total of 36 articles were excluded during screening, all of which were subsequently consulted to inform this review.

Figure 2.

The systematic selection of studies included in the meta-analysis dataset, with numerical values representing the quantity of records identified and retained at each stage of the literature screening process. The search was conducted using the Web of Science database.

The systematic literature screening process of this review is summarized in Figure 2. First, a total of 651 records were initially identified from the Web of Science database using the core keyword combination "cottonseed protein, fish". After removing duplicates, 317 records proceeded to the abstract screening stage. At this stage, publications that were not original research articles on fish (e.g., reviews, conference abstracts, reports, etc.) were excluded. Subsequently, 286 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. The main reasons for exclusion at the final stage were the lack of sufficient statistical data for quantitative analysis or the publications falling outside the prioritized timeframe (the past five years). Ultimately, 65 articles met all the inclusion criteria and formed the core evidence base for the meta-analysis and comprehensive synthesis presented in this review.

2. The Effect of Cottonseed Protein on Fishes

2.1. Comparative Effects of Different Plant Proteins on Fish Health

The search for sustainable alternatives to fishmeal in aquaculture has intensified due to declining marine resources, price volatility, and environmental concerns [29]. Plant proteins offer a promising solution, with cottonseed, soybean, rapeseed meal, and lupin representing widely studied options [30,31,32]. These ingredients can reduce reliance on finite marine resources while providing cost-effective nutrition. However, their integration into fish diets is complicated by species-specific responses [33] and the presence of antinutritional factors (ANFs), which may impair growth and health [34].

As demonstrated in Table 2, Cottonseed protein, valued for its high protein content, exemplifies this duality. While it can effectively replace fishmeal in terms of crude protein provision, its free gossypol content poses risks such as growth inhibition and intestinal damage [35]. Similarly, soybean protein boasts a balanced amino acid profile but contains trypsin inhibitors that can trigger enteritis [36]. Rapeseed meal is economically appealing yet burdens the liver due to glucosinolates and phytate [37]. Lupin protein, despite high digestibility and beneficial carbohydrates, is limited by alkaloids and phytic acid [38].

Table 2.

This table summarizes the primary antinutritional factors, core nutritional value, main negative impacts, and fishmeal replacement/additive levels for the selected plant protein sources used as alternative feed ingredients in fish diets. The information presented in the column for Main Negative Impacts and Fishmeal Replacement/Additive Levels is derived from the most favorable data reported in the literature, specifically where no adverse effects were observed on the aquatic species. The referenced information is sourced from studies conducted on specific fish species, highlighting both their strengths and limitations. However, the generalizability of these findings to all fish species remains uncertain and warrants further comprehensive investigation.

These plant proteins share common advantages: they are more sustainable and often cheaper than fishmeal. Yet, their ANFs can disrupt nutrient absorption, cause organ stress, and reduce feed palatability [55,56]. Critically, the physiological and behavioral differences among fish species lead to species-specific responses to dietary plant proteins, both in terms of the nature and magnitude of the effects [57,58]. However, when it comes to replacing fishmeal in aquafeeds or its inclusion levels, cottonseed protein demonstrates superior advantages. Through breeding techniques, glandless cottonseed protein is fundamentally “detoxified” at the source [59]. In contrast to other plant proteins, which can only be included using optimal strategies but still have limitations, glandless cottonseed protein stands out as other plant proteins cannot fully replace fishmeal.

Based on the above, while plant proteins are viable partial substitutes for fishmeal, their application must be species-specific. Future work should prioritize ANF mitigation strategies—such as processing technologies and genetic improvement—and expand research to cover a wider range of fish species to ensure broader and safer application.

2.2. Integrated Effects of Cottonseed Protein on Protein and Energy Metabolism in Fish

As plant-derived protein ingredients, cottonseed meal (CSM) and its concentrated product, cottonseed protein concentrate (CPC), exert multifaceted impacts on protein metabolism in fish, primarily attributed to their intrinsic amino acid imbalance and the presence of specific antinutritional factors (ANFs) [60]. A crucial disadvantage of CSM/CPC is their deficiency in essential amino acids, particularly lysine and methionine [61], which limits the bioavailability of dietary protein and directly impairs protein synthesis efficiency [62]. Consequently, while moderate inclusion can partially replace fishmeal, substitutions exceeding 30% often lead to growth retardation and reduced protein retention rates across various fish species, a finding corroborated by studies on rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) [63,64].

At the molecular level, the growth inhibition caused by excessive CSM/CPC inclusion is directly associated with the suppression of anabolic pathways [65,66]. The Target of Rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway, a central regulator of protein synthesis, is a key affected node. For instance, in silver sillago (Sillago sihama), replacing fishmeal with defatted CSM significantly downregulated the expression of hepatic TOR pathway-related genes, providing a mechanistic explanation for impaired cellular protein synthesis capacity [67].

To counteract these negative effects, researchers have explored various nutritional regulation strategies. A promising approach is dietary supplementation with sulfated algal polysaccharides (SAPs). In rainbow trout and Pacific white shrimp fed CPC-based diets, SAPs have been shown to improve intestinal morphology, enhance digestive capacity, and strengthen antioxidant defense systems, thereby promoting protein utilization efficiency [68,69]. Additionally, precise balancing of dietary protein and energy levels is crucial. Leveraging the protein-sparing effect—by optimizing non-protein energy sources such as lipids and carbohydrates—can redirect amino acids toward growth rather than catabolism for energy, thereby improving feed efficiency and reducing environmental nitrogen emissions [70]. However, this balance is delicate: energy deficiency can trigger protein catabolism, while energy excess may lead to reduced feed intake and lipid deposition, further impairing protein metabolism [71].

In fact, cottonseed protein products (especially insufficiently defatted ones) contain cottonseed oil, which is characterized by a high proportion of linoleic acid (18:2 n-6, an n-6 PUFA) and low levels of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs) such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [72,73]. Fish fed cottonseed protein exhibit a significant increase in n-6 PUFA levels and a decrease in n-3 PUFA levels in tissues (e.g., muscle and liver), which alters cellular membrane lipid composition [74] and physiological functions [5]. The lipids inherent in cottonseed protein provide additional energy that fish can utilize as a primary energy source, thereby diverting more dietary protein toward growth (protein synthesis) rather than oxidation for energy [75].

Gossypol toxicity may impair hepatic function, and hepatic dysfunction can hinder fat export, leading to hepatic steatosis [76]. High inclusion levels of cottonseed protein—particularly those with high gossypol content—result in hepatic enlargement, pale coloration, and fatty infiltration in fish [77]. This phenomenon reflects not only dyslipidemia but also an imbalance in energy metabolism.

Recent research indicates that fermented or detoxified cottonseed protein can significantly alleviate these adverse metabolic effects; in some fish species such as grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), it may even enhance feed utilization efficiency [78]. This aligns with the broader regulatory pattern of cottonseed protein on fish metabolism, which includes mTOR-mediated modulation of muscle texture and dose-dependent effects on carbohydrate metabolism—with inclusion levels exceeding 30% potentially inducing metabolic disruptions due to gossypol, while processed forms exhibit reduced toxicity. Future optimization of cottonseed protein application in aquafeeds should therefore focus on species-specific formulations and detoxification protocols to maximize its potential as a sustainable component.

2.3. Cottonseed Protein Affects Fish Muscle Texture via mTOR Signaling and Ultrastructure

Muscle development and ultrastructure are core determinants of meat quality, regulated primarily by the dynamic balance between protein synthesis and degradation [79,80]. Studies have shown that dietary supplementation of cottonseed protein concentrate (CPC) affects this regulatory network. In Sillago sihama, replacing fishmeal with defatted cottonseed meal led to a significant downregulation of hepatic TOR pathway genes, indicating systemic suppression of anabolic signaling [81]. Such molecular-level changes are often reflected in alterations in muscle tissue composition. For example, in Micropterus salmoides, CPC-based diets increased flavor-related free amino acids (e.g., aspartic acid and glutamic acid) while reducing intramuscular lipid content [82]. Since lipid content is associated with muscle tenderness and juiciness, its reduction may directly impact sensory quality.

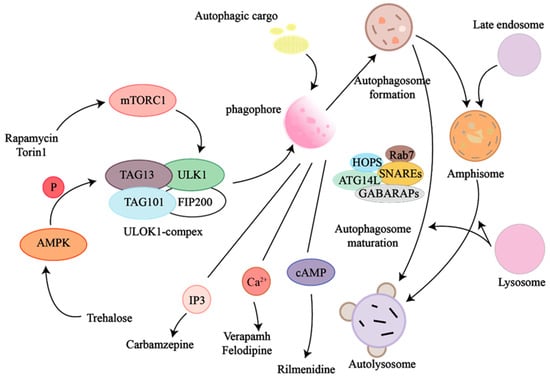

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a core regulator of protein synthesis and cell growth, which integrates nutritional and hormonal signals to regulate muscle hypertrophy in fish [83]. The mTOR signaling pathway exerts its functions through two functionally distinct complexes: mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR Complex 2 (mTORC2). As illustrated in Figure 3 mTORC1 acts as a nutrient-sensing hub that integrates environmental signals (e.g., amino acids, growth factors) [84]; its activation induces the phosphorylation of downstream effectors such as ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1), thereby promoting protein synthesis and cell proliferation [85]. Conversely, nutrient deprivation suppresses this pathway, leading to growth retardation [86]. mTORC2 primarily regulates cell survival through the phosphorylation of protein kinase B (Akt/PKB) [87].

Figure 3.

Fish mTOR pathway (central regulator of growth, development, metabolic homeostasis, stress adaptation) is evolutionarily conserved, centered on mTOR kinase, via mTORC1/mTORC2.

Although the core structure of the mTOR pathway is highly conserved among vertebrates, fish exhibit unique regulatory adaptations within this pathway [88]. In fish, mTORC1 specifically mediates tissue hypertrophy and hyperplastic growth [89,90], and enhanced mTOR signaling is associated with accelerated somatic growth and improved feed conversion efficiency [91,92].

Based on these findings, we propose that the regulation of fish muscle quality by cottonseed protein is a coordinated regulatory process dominated by systemic signals. We hypothesize that the downregulation of the hepatic mTOR signaling pathway serves as the “trigger” initiating this process, which may induce systemic metabolic reprogramming to prioritize basic life activities at the expense of traits such as intramuscular lipid deposition. This precisely reflects an adaptive strategy of fish under nutritional stress. Future studies need to verify the “liver-muscle axis” hypothesis and further explore how to adopt precision nutrition strategies (e.g., supplementation of specific amino acids or use of fermented cottonseed protein). Furthermore, a study by He et al [82] demonstrated that diets based on cottonseed protein concentrate (CPC) can alter muscle composition by increasing the content of flavor-related free amino acids and reducing intramuscular lipid content. These compositional changes are critical as they are known to influence sensory attributes; however, their net effect on overall sensory quality (including both flavor and texture) requires further direct evaluation via sensory panels or instrumental texture analysis. In particular, the reduction in intramuscular lipid content may compromise muscle juiciness and tenderness, highlighting a potential trade-off between flavor enhancement and textural properties.

Based on the available evidence, cottonseed protein exhibits significant potential as a sustainable fishmeal alternative. However, while it can partially replace fishmeal, inclusion levels exceeding 30% often suppress fish growth and systemic metabolism—an effect primarily mediated by the downregulation of the hepatic mTOR pathway, a central regulator of protein synthesis. This regulation triggers a shift in fish physiological status, redirecting energy allocation from growth toward metabolic stress adaptation. Future breakthroughs in the application of cottonseed protein will depend on the synergistic innovation of precision nutrition technologies and advanced processing techniques. Among these, glandless (gossypol-free) cottonseed varieties are regarded as the most promising development direction, holding the potential to unlock its full application potential without compromising fish health or product quality.

3. Cottonseed Protein and Gossypol

3.1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Cottonseed Protein as a Fishmeal Substitute

According to Table 3 CSP and CPC show high crude protein content, demonstrating potential to replace fish meal. However, their lysine and methionine levels require supplementation. Advanced processing reduces free gossypol in CPC to a safe level (<0.04%). Cottonseed Protein (CSP) contains 50–60% crude protein, while Cottonseed Protein Concentrate (CPC) reaches 60–65% [93], providing a high-protein basis for fishmeal replacement. However, both CSP and CPC have significantly lower lysine levels than fishmeal and soybean meal, requiring supplementation with crystalline lysine or blending with lysine-rich ingredients. CSP has higher methionine content than soybean meal and CSM-type fishmeal (0.5–0.6%) and is comparable to CPC (0.9–1.1%), yet remains lower than fish-type fishmeal (1.9–2.2%). Despite its relatively high methionine level, supplementation is still necessary. Methionine is involved in methylation reactions and antioxidant metabolism, with its concentration potentially affecting fish growth and metabolic efficiency. Free gossypol content is 0.04–0.1% in CSP and <0.04% in CPC, significantly lower than that in cottonseed meal (0.1–1.2%) [94,95,96]. This confirms that processing technologies effectively reduce gossypol, improving its safety for use in fish feed.

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis Table of Nutritional Composition of Major Feed Protein Sources (Based on Dry Matter).

Fishmeal has long served as a high-protein aquafeed ingredient, rich in phospholipids, highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs), minerals, and vitamins—components indispensable for aquatic animal nervous system development, survival rate improvement, and stress resistance enhancement [97]. Its comprehensive nutritional value is critical for sustaining aquaculture production efficiency and stability, especially for carnivorous fish. However, rising market prices and limited global supply have made over-reliance on fishmeal economically and environmentally unsustainable [98], making the identification and validation of partial fishmeal alternatives a key priority in modern aquaculture research.

Although soybean meal is widely used as the main plant protein source for herbivorous fish, its application is constrained by high costs and supply chain limitations [99]. Therefore, identifying and optimizing cost-competitive plant protein alternatives with improved nutrient utilization is essential for sustainable aquaculture development.

Cottonseed meal, an economical byproduct of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) oil processing, has high production yields and is widely used in aquafeeds [60]. Via advanced concentration technologies, cottonseed protein concentrate (CPC) has emerged as a novel plant-based protein alternative, featuring high crude protein content (60–65% dry matter) and a rich essential amino acid profile [100]. Nutritional assessments show CPC has high protein bioavailability (apparent digestibility coefficient, ADC > 85%) [101] and low gossypol residues (<0.04% free gossypol) [102]. Combined with its 25–35% cost advantage over fishmeal (FM) [103] and consistent production independent of fishing quotas, these traits make CPC a competitive fishmeal alternative.

3.2. Anti-Nutritional Factors (ANFs)—Gossypol

Antinutritional factors significantly exacerbate these adverse effects, with free gossypol being the most prominent. Gossypol, a naturally occurring polyphenolic terpenoid, is primarily localized in the pigment glands of cotton plants (Gossypium spp.). It exists in two forms: toxic free gossypol, characterized by reactive aldehyde and hydroxyl groups that confer toxicity, and bound gossypol, which forms complexes with other molecules [104]. These functional groups on free gossypol act as a natural defense against pests such as cotton bollworms (Helicoverpa armigera) [105], playing an important protective role during cotton growth.

Figure 4 schematically illustrates the pathological cascade through which dietary gossypol compromises the intestinal barrier integrity of fish. Upon ingestion, free gossypol acts on intestinal epithelial cells, disrupting the expression and assembly of key tight junction proteins such as zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and Occludin [106]. This disruption leads to the breakdown of intercellular sealing structures, with a consequent increase in intestinal permeability [5]. The impaired barrier then allows luminal pathogens, toxins, and other harmful substances to translocate through the intercellular spaces into the intestinal epithelial cells [107]. The influx of these substances activates the local immune system, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and initiating an inflammatory cycle that further damages the epithelial layer, ultimately resulting in systemic health impairments in fish [108].

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of gossypol impairing intestinal barrier integrity in fish.

During processing, free gossypol binds to lysine and iron ions; this interaction reduces red blood cell counts in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), posing health risks [109]. It also impairs gastrointestinal digestive enzyme activity, hinders nutrient digestion and absorption, and suppresses gastrin secretion, leading to bloating and compromised growth performance [110]. The free gossypol content is generally <1200 mg/kg in cottonseed meal and <400 mg/kg in de-gossypollated cottonseed protein and can be further reduced via advanced isolation techniques to 4.8 mg/kg (free gossypol) and 147.2 mg/kg (total gossypol) [111].

Gossypol exerts toxicity through multiple mechanisms: it induces erythrocyte apoptosis by increasing intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, resulting in apoptotic features such as membrane blebbing and cellular shrinkage [112], and disrupts thyroid hormone metabolism in affected animals.

3.3. Detoxification of Cottonseed Protein

Plant protein isolation faces substantial technical challenges due to structural barriers (e.g., resilient cell walls) and differential solubility among protein fractions (globulins, albumins, glutenins, prolamins) [113]. Current industrial processing yields four primary cottonseed protein variants: de-gossypolized cottonseed protein (crude protein ≥ 50%, free gossypol ≤ 400 mg/kg) [114], produced via low-temperature extraction and gossypol removal; cottonseed protein concentrate, manufactured through low-temperature extraction and drying (avoiding thermal degradation of conventional high-temperature processing) [115]; fermented cottonseed protein, produced via solid-state microbial fermentation and enriched with organic acids, digestive enzymes, and bioactive peptides to enhance nutritional quality [116]; and hydrolyzed cottonseed protein, comprising enzymatically derived amino acid/peptide mixtures with improved bioavailability [117].

Free anti-nutritional factors in cottonseed protein require detoxification to mitigate adverse impacts on fish growth. Main detoxification methods include physical, chemical, and biological fermentation approaches. Physical processing has advanced from inefficient traditional extrusion to sophisticated heat treatment techniques that concurrently improve feed nutritional value. Among chemical methods, solvent extraction using aqueous and alkaline systems predominates due to high protein recovery and effective gossypol reduction. The advanced “liquid–liquid–solid three-phase extraction” method [118] has become the production standard for de-gossypolized cottonseed protein, with low-temperature extraction that minimizes nutrient loss and enables efficient gossypol removal. It has addressed historical limitations in protein retention and solvent recovery, establishing itself as an economically feasible and production-ready technology.

Microbial fermentation is particularly effective in reducing free gossypol and other anti-nutritional factors. This biological approach, analogous to enzymatic hydrolysis, employs microbial-derived enzymes to simultaneously degrade cottonseed protein into bioactive peptides and eliminate free gossypol [119], offering a promising avenue for value-added processing.

The extraction of cottonseed protein involves a multi-step process (Figure 5) that begins with the preparation of high-quality cottonseeds, which are carefully selected, cleaned of impurities, and thoroughly washed to facilitate subsequent processing [120]. The seeds are then mechanically dehulled to remove the outer shell and obtain the kernels, which are subsequently ground into a fine powder to enhance protein extraction efficiency [121]. The extraction phase employs solvent-based methods, where the powdered kernels are mixed with water or dilute acid/alkaline solutions under controlled temperature conditions to solubilize the proteins [122]. The extracted protein solution is then concentrated through techniques such as ultrafiltration or membrane separation to increase protein content [123]. Subsequently, the concentrated liquid is dried using spray drying or freezing drying methods to produce a stable protein powder [124]. Finally, the dried powder is further processed through grinding and screening to achieve the desired particle size before packaging [125]. Throughout the entire process, precise control of temperature, pH, and processing time is critical to ensure optimal protein yield and preserve its functional properties.

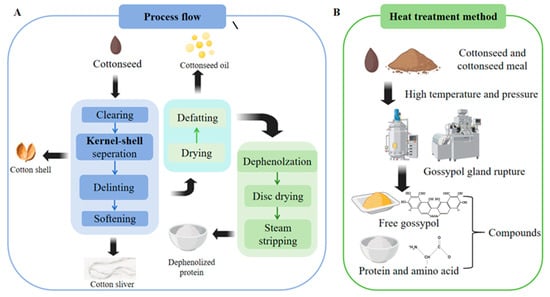

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram illustrating the integrated process for producing detoxified cottonseed meal with high nutritional value. (A) The preparatory steps include seed cleaning, kernel-shell separation, softening, and flaking, followed by oil extraction and key detoxification steps such as drying and dephenolization. (B) The critical heat-treatment stage involves high-temperature and pressure conditioning to rupture the gossypol glands, binding free gossypol and rendering it safe. This conceptual workflow is adapted and synthesized based on established methods reported in the literature [126,127]. In this study, application of this process, particularly the high-temperature detoxification, effectively reduced free gossypol to <0.01% while preserving >85% protein bioavailability and >92% lysine retention, meeting FAO/WHO standards for safe alternative proteins.

Detoxified gossypol refers to the process of removing or converting toxic free gossypol in cottonseed into a safe form through physical, chemical, or biological techniques [128]. As can be seen from Table 4, different methods exhibit significant differences in detoxification mechanisms and effects. Biological methods demonstrate distinct advantages in terms of detoxification efficiency and nutritional improvement [129]. Among them, fermentation treatments with Bacillus subtilis and Candida tropicalis, as well as enzymatic catalysis by CotA-laccase, all achieve high gossypol removal rates ranging from 87% to 100% [130]. More importantly, these methods fundamentally enhance the nutritional quality of cottonseed meal: the fermentation process degrades macromolecular proteins into small peptides and amino acids, increasing the proportion of digestible protein by approximately fivefold while significantly elevating the content of digestible essential amino acids [131]. In contrast, the laccase-mediated method is characterized by high efficiency, rapidity (completed within 2 h), and non-toxic degradation products [132].

Table 4.

Comparison of the efficacy of different gossypol detoxification methods in cottonseed meal.

In contrast, physical methods differ in their detoxification mechanisms and objectives. The direct detoxification rate of 45 kGy gamma irradiation is relatively low, and its primary value lies in altering the metabolic pathway of protein in ruminants [136]. This method can effectively form rumen-protected protein, protecting cottonseed protein from degradation by rumen microbes and thereby enabling it to enter the small intestine intact for direct digestion and absorption by the host [137]. However, for aquafeeds containing cottonseed protein, this method requires further research to confirm its efficacy.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

This review systematically evaluates the comprehensive impacts of cottonseed protein as a fishmeal substitute in fish feeds. Cottonseed protein, especially in its concentrated form (CPC), is a highly promising sustainable protein source due to its high protein content and cost advantages. However, its successful application largely depends on the removal of major antinutritional factors, particularly free gossypol. Research has shown that high-proportion replacement of fishmeal (typically >30%) can inhibit fish growth, reduce protein deposition rate, and impair intestinal health due to the presence of gossypol. These adverse effects are largely mediated by the downregulation of the hepatic mTOR pathway—a key regulator of protein synthesis and cell growth. High inclusion levels, especially of non-detoxified products, will continuously inhibit the hepatic mTOR pathway. This inhibition prompts organisms to prioritize homeostasis and stress adaptation over growth and biomass accumulation, which is manifested as reduced protein deposition rate and altered muscle composition characterized by decreased intramuscular lipid content. This represents a potential trade-off between survival adaptation and desirable meat quality. The unique fatty acid profile of cottonseed protein—rich in n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) but deficient in n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs)—will further exacerbate the associated energy metabolic imbalance, potentially altering cell membrane physiology and inflammatory tone.

Despite these challenges, the application prospects of cottonseed protein are promising with advancements in processing technologies. Physical, chemical, and biological detoxification methods—especially biological strategies such as Bacillus subtilis fermentation and CotA laccase-catalyzed degradation—not only efficiently degrade gossypol (removal rate > 90%) but also convert macromolecular proteins into more digestible and absorbable small peptides and amino acids, thereby significantly enhancing the nutritional value of cottonseed protein. From an economic and environmental perspective, the utilization of cottonseed protein reduces feed costs, enhances resilience against fishmeal price volatility, and aligns with the principles of the circular economy by realizing the resource utilization of agricultural by-products and reducing reliance on marine resources.

Although existing studies have made progress in growth performance and some physiological indicators, a critical gap remains in the current knowledge system: Little is known about the deeper metabolic pathways, the absorption and utilization efficiency of nutrients, and the long-term impacts on metabolic homeostasis in fish after ingesting detoxified cottonseed protein. Future research should focus on using molecular nutrition and multi-omics technologies to systematically clarify the metabolic trajectories of cottonseed protein treated with different detoxification processes in fish and evaluate its long-term physiological effects on hepatic metabolism and intestinal health.

In conclusion, in-depth elucidation of the metabolic and physiological mechanisms of cottonseed protein in fish will provide a solid scientific basis for optimizing detoxification processes and formulating precision feeding strategies. In this process, glandless cottonseed, which fundamentally addresses the gossypol issue, is regarded as the most transformative development direction. Through continuous technological innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration, cottonseed protein is expected to evolve from a promising substitute to an economical, safe, and environmentally friendly core feed protein ingredient, making significant contributions to the sustainable development of the global aquaculture industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.C. and D.L.; methodology, J.L. (Jie Luo); software, R.A.-S.D.; validation, E.M.; formal analysis, Y.T. and J.L. (Jiarui Liu); investigation, Q.C.; resources, Q.C.; data curation, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.X.; visualization, Q.C.; supervision, Q.C.; project administration, Q.C.; funding acquisition, Q.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Talent Recruitment Program (24030403699) and Provincial Undergraduate Training Program on Innovation, Entrepreneurship (No.S202410626065 and No.S202510626039) and Sichuan Agricultural University Dual-Branch Plan Special Project of Discipline Construction (2025ZYTS008).

Data Availability Statement

No data is available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Many Thanks to General Manager Liu Jiangang of Sichuan Honglianshan Ecological Agriculture Development Co., Ltd. for his guidance and exchange on nutrition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Norman, R.; Crumlish, M.; Stetkiewicz, S. The importance of fisheries and aquaculture production for nutrition and food security. Rev. Sci. Et Tech. 2019, 38, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jin, M.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zong, J.; Shan, H.; Kang, H.; Xu, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Oxytetracycline-induced oxidative liver damage by disturbed mitochondrial dynamics and impaired enzyme antioxidants in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Aquat. Toxicol. 2023, 261, 106616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024: Towards Blue Transformation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tacon, A.G.J.; Metian, M. Global overview on the use of fish meal and fish oil in industrially compounded aquafeeds: Trends and future prospects. Aquaculture 2008, 285, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Hu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Tang, Y.; Luo, J.; Li, D.; Mbokane, E. Dietary cottonseed protein substituting fish meal induces hepatic ferroptosis through SIRT1-YAP-TFRC axis in Micropterus salmoides: Implications for inflammatory regulation and liver health. Biology 2025, 14, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Cottonseed proteins from meals with high yield for plasticizer-free biofilms with good mechanical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.H.; Oldfield, J.E. Cottonseed meal in aquatic animal diets: A review. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2001, 90, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nagalakshmi, D.; Rao, S.V.R.; Panda, A.K.; Sastry, V.R.B. Cottonseed meal in poultry diets: A review. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, H.; Olk, D.C.; Shankle, M.; Way, T.R. Protein and fiber profiles of cottonseed from upland cotton with different fertilizations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, A.; Raza, S.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.N.; Ahmad, N. Exploring the significance of protein concentrate: A review on sources, extraction methods, and applications. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Wu, Z.; Hang, S.; Zhu, W.; Wu, G. Amino acid composition and digestibility of cottonseed meal protein in animal feeding. Aquaculture 2020, 515, 734589. [Google Scholar]

- Manam, V.K. Fish feed nutrition and its management in aquaculture. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2023, 11, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Klasson, K.T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Pilot-scale production of washed cottonseed meal and co-products. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2016, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świątkiewicz, S.; Arczewska-Włosek, A.; Józefiak, D. The use of cottonseed meal as a protein source for poultry: An updated review. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2016, 72, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, L. Improved quality of cottonseed meal: Effect of cottonseed protein isolate on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and intestinal health in growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 103, skaf057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimidis, K.; Birtsou, C.; Kalfakakou, V.; Fletouris, D. Preparation of an edible cottonseed protein concentrate and evaluation of its functional properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 58, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhao, J.; Huang, J.; Lu, C.; Wu, D.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Zheng, X. Cottonseed protein concentrate as an effective substitute to fish meal in pike perch (Sander luciperca) feed: Evidence from growth performance and intestinal responses of immune function and microflora. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1522005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Yu, D.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Ma, L.; Xu, S. Sustainable utilization of cottonseed meal: Integrated protein extraction and detoxification using deep eutectic solvents. Food Chem. 2025, 485, 144499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, F.; Zhou, N.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z. Probiotic Pediococcus pentosaceus restored gossypol-induced intestinal barrier injury by increasing propionate content in Nile tilapia. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Feng, L.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, P.; Jiang, J. Dietary gossypol reduced intestinal immunity and aggravated inflammation in on-growing grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2019, 86, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, T.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Pyroptosis in fish research: A promising target for disease management. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2023, 139, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhao, J.; He, L.; Zhang, T.; Feng, L.; Jiang, W.; Wu, P.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Evaluation of the dietary L-valine on fish growth and intestinal health after infection with Aeromonas veronii. Aquaculture 2024, 580, 740294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Feng, L.; Jiang, W.; Wu, P.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Evaluation of glycyrrhetinic acid in attenuating adverse effects of a high-fat diet in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Anim. Nutr. 2024, 19, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Cao, Q.; Jin, M.; Shen, T.; Ribas, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. A comprehensive study of enzyme-treated soy protein on intestinal barrier integrity, inflammatory responses, and liver lipid metabolism in Micropterus salmoides. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 22, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.E.; Aksoy, M.; Klesius, P.H. Gossypol in aquaculture diets. In Proceedings of the Aquafeed Technical Workshop, Victam Asia 2006, Bangkok, Thailand, 8–10 March 2006; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Gao, T.; Hao, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X. Anaerobic solid-state fermentation with Bacillus subtilis for digesting free gossypol and improving nutritional quality in cottonseed meal. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1017637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.Y.; Jiang, G.Z.; Cheng, H.H.; Liu, M.Y.; Li, X.F. Replacing fish meal with cottonseed meal protein hydrolysate affects growth, intestinal function, and growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor I axis of juvenile blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 1235–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troell, M.; Naylor, R.L.; Metian, M.; Beveridge, M.; Tyedmers, P.H.; Folke, C.; de Zeeuw, A. Does aquaculture add resilience to the global food system? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13257–13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.M.; Bano, A.A.; Ali, S.; Saghir, M.; Iqbal, S. Substitution of fishmeal: Highlights of potential plant protein sources for aquaculture sustainability. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.F.; Limbu, S.M.; Qiao, F.; Du, Z.-Y.; Zhang, M.-L. Seeking the best alternatives: A systematic review and meta-analysis on replacing fishmeal with plant protein sources in carnivorous fish species. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1099–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.H.; Li, M.H. Use of plant proteins in catfish feeds: Replacement of soybean meal with cottonseed meal and replacement of fish meal with soybean meal and cottonseed meal. J. World Aquac. Soc. 1994, 25, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; He, L.; Shan, H.; Faggio, C.; Cao, Q.; Jiang, J. 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid mitigates adverse effects of high fat diet on liver fibrosis in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) by reducing mitochondrial Ca2+ level. Anim. Nutr. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniasih, T.; Zulkarnain, R.; Wijaya, R.; Lesmana, D.; Mumpuni, F.S.; Panigoro, N.; Sutisna, E.; Heptarina, D.; Fitria, Y. Digestibility of plant-based feeds in omnivorous, carnivorous, and herbivorous fish: A review of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758)), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822)), and grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella (Valenciennes, 1844)). AACL Bioflux 2024, 17, 2994–3014. [Google Scholar]

- Gopan, A.; Lalappan, S.; Varghese, T.; Anikuttan, K.K.; Saravanan, K. Anti-nutritional factors in plant-based aquafeed ingredients: Effects on fish and amelioration strategies. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Commun. 2020, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, H. Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) exhibited better growth potential after adaptation to dietary cottonseed protein concentrate inclusion but experienced higher inflammatory risk during bacterial infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 997985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Ren, M.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Ge, X.; Ji, K.; Liu, B. Excessive replacement of fish meal by soy protein concentrate resulted in inhibition of growth, nutrient metabolism, antioxidant capacity, immune capacity, and intestinal development in juvenile largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Antioxidants 2024, 13, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Danwitz, A.; Schulz, C. Effects of dietary rapeseed glucosinolates, sinapic acid and phytic acid on feed intake, growth performance and fish health in turbot (Psetta maxima L.). Aquaculture 2020, 516, 734624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malarvizhi, K.; Kalaiselvan, P.; Ranjan, A. Unlocking the potential of lupin as a sustainable aquafeed ingredient: A comprehensive review. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageshwaran, V. An overview of gossypol and methods of its detoxification in cottonseed meal for non-ruminant feed applications. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2021, 12, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Xie, D.; Huang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Q. Effects of replacing fish meal with enzymatic cottonseed protein on the growth performance, immunity, antioxidation, and intestinal health of Chinese soft-shelled turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis). Aquac. Nutr. 2023, 2023, 6628805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhong, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Li, W. Gossypol is the main limiting factor in the application of cottonseed meal in grass carp feed production: Involvement of growth, intestinal physical and immune barrier, and intestinal microbiota. Water Biol. Secur. 2024, 3, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.D.; Alam, M.S.; Watanabe, W.O.; Carroll, P.M.; Wedegaertner, T.C. Full replacement of menhaden fish meal protein by low-gossypol cottonseed flour protein in the diet of juvenile black sea bass Centropristis striata. Aquaculture 2016, 464, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, D.; He, S.; Zhang, R.; Gao, K.; Qiu, M.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Xue, S.; Shi, J. Exploring the dual role of anti-nutritional factors in soybeans: A comprehensive analysis of health risks and benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 65, 5772–5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, W.M.; Pezzato, L.E.; Barros, M.M.; Pezzato, A.C.; Furuya, V.R.B.; Miranda, E.C. Use of ideal protein concept for precision formulation of amino acid levels in fish-meal-free diets for juvenile Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.). Aquac. Res. 2004, 35, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Hong, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Tryptophan ameliorates soybean meal-induced enteritis via remission of oxidative stress, mitophagy hyperactivation, and apoptosis inhibition in hybrid yellow catfish gut (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco♀ × Pelteobagrus vachelli♂). Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, J. The effect of fish meal replacement by soyabean products on fish growth: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 1709–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Cao, L. Biotransformation technology and high-value application of rapeseed meal: A review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, E.A.; Matter, A.F.; Mohammed, L.S.; Hassan, A.M.; El-Sayed, H.S. Replacing fish meal with rapeseed meal: Potential impact on the growth performance, profitability measures, serum biomarkers, antioxidant status, intestinal morphometric analysis, and water quality of Oreochromis niloticus and Sarotherodon galilaeus fingerlings. Vet. Res. Commun. 2021, 45, 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Karolina, W.A.; Justyna, N. Rapeseed meal as an alternative protein source in fish feed and its impact on growth parameters, digestive tract, and gut microbiota. Animals 2025, 15, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dossou, S.; Koshio, S.; Ishikawa, M.; Yokoyama, S.; Dawood, M.A.O.; El Basuini, M.F.; Olivier, A. Effect of partial replacement of fish meal by fermented rapeseed meal on growth, immune response and oxidative condition of red sea bream juvenile, Pagrus major. Aquaculture 2018, 490, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schryvers, S.; Jacxsens, L.; Croubels, S.; De Saeger, S.; De Boevre, M. Quinolizidine alkaloids and phomopsin A in animal feed containing lupins: Co-occurrence and carry-over into veal products. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2024, 41, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, G.L.; Booth, M.A. Effects of extrusion processing on digestibility of peas, lupins, canola meal and soybean meal in silver perch Bidyanus bidyanus (Mitchell) diets. Aquac. Res. 2004, 35, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcuy, R.L.; Casaretto, M.E.; Márquez, L.; Rojas, H. Evaluation of phytase impact on in vitro protein and phosphorus bioaccessibility of two lupin species for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac. Nutr. 2024, 2024, 2697729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudaryono, A. The performance of lupin meal as an alternative to fishmeal in diet of juvenile Penaeus monodon under pond conditions. J. Coast. Dev. 2003, 6, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Devarajan, S.; Manickavasagan, A.; Maqsood, S. Antinutritional factors and biological constraints in the utilization of plant protein foods. In Plant Protein Foods; Manickavasagan, A., Maqsood, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 407–438. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, G.; Makkar, H.P.S.; Becker, K. Antinutritional factors present in plant-derived alternate fish feed ingredients and their effects in fish. Aquaculture 2001, 199, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macusi, E.D.; Cayacay, M.A.; Borazon, E.Q.; Abrea, L.A.; Lopez, M.K.P.; Gangan, A.U.; Gutierrez, R.R.; Dagunan, S.L.; Pantallano, A.S.B. Protein fishmeal replacement in aquaculture: A systematic review and implications on growth and adoption viability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, N. A review on replacing fish meal in aqua feeds using plant protein sources. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2018, 6, 164–179. [Google Scholar]

- Sunilkumar, G.; Campbell, L.M.; Puckhaber, L.; Stipanovic, R.D.; Rathore, K.S. Engineering cottonseed for use in human nutrition by tissue-specific reduction of toxic gossypol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18054–18059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.; Robinson, E.H. Use of cottonseed meal in aquatic animal diets: A review. North Am. J. Aquac. 2006, 68, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Ding, Z.L.; He, X.H.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. Cottonseed protein concentrate as fish meal substitution in fish diet: A review. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 51, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbo, N.W.; Madalla, N.; Jauncey, K. Effects of dietary cottonseed meal protein levels on growth and feed utilization of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus L. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2011, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-J. Nutritional and Physiological Studies of Rainbow Trout Following Utilization of Cottonseed Meal-Based Diets. Doctoral Dissertation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.P.; Ramudu, K.R.; Devi, B.C. Mini review on incorporation of cotton seed meal, an alternative to fish meal in aquaculture feeds. Int. J. Biol. Res. 2014, 2, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.M.; Blenis, J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D.M. An emerging role of mTOR in lipid biosynthesis. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, R1046–R1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Habte-Tsion, H.-M.; Ge, X.-P.; Liu, B.; Xie, J.; Chen, R.-L. Growth performance and TOR pathway gene expression of juvenile blunt snout bream, Megalobrama amblycephala, fed with diets replacing fish meal with cottonseed meal. Aquac. Res. 2017, 48, 4119–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakky, M.A.H.; Kang, K.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, J.-M. Utilization of marine macroalgae-derived sulphated polysaccharides as dynamic nutraceutical components in the feed of aquatic animals: A review. Aquac. Res. 2022, 53, 5787–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H. Effects of replacing fishmeal with cottonseed protein concentrate on growth performance, blood metabolites, and the intestinal health of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1079677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Nutrient Requirements of Fish and Shrimp; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzifotis, S.; Panagiotidou, M.; Papaioannou, N.; Pavlidis, M.; Nengas, I.; Mylonas, C.C. Effect of dietary lipid levels on growth, feed utilization, body composition and serum metabolites of meagre (Argyrosomus regius) juveniles. Aquaculture 2010, 307, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, T.; Iqbal, M.W.; Mahmood, S.; Hussain, N.; Younas, A. Cottonseed oil: A review of extraction techniques, physicochemical, functional, and nutritional properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 1219–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassef, E.A.; Shalaby, S.H.; Saleh, N.E. Cottonseed oil as a complementary lipid source in diets for gilthead seabream Sparus aurata juveniles. Aquac. Res. 2015, 46, 2469–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erondu, E.S.; Akpoilih, B.U.; John, F.S. Total replacement of dietary fish oil with vegetable lipid sources influenced growth performance, whole body composition, and protein retention in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fingerlings. J. Appl. Aquac. 2023, 35, 330–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, K.; Li, P.; Zhang, Z.; Song, K. Effects of replacement of dietary fishmeal by cottonseed protein concentrate on growth performance, liver health, and intestinal histology of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 764987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Lipotoxic effects of gossypol acetate supplementation on hepatopancreas fat accumulation and fatty acid profile in Cyprinus carpio. Aquac. Nutr. 2022, 2022, 2969246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Fu, Y.; Feng, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. The effects of fishmeal replacement with degossypolled cottonseed protein on growth, serum biochemistry, endocrine responses, lipid metabolism, and antioxidant and immune responses in black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus). Animals 2025, 15, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y. Dietary Clostridium butyricum metabolites mitigated the disturbances in growth, immune response and gut health status of Ctenopharyngodon idella subjected to high cottonseed and rapeseed meal diet. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2024, 154, 109934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzinger, C.F. Differential response of skeletal muscles to mTORC1 signaling during atrophy and hypertrophy. Skelet. Muscle 2010, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Shan, H.; Zong, J.; Cao, Q.; Jiang, J. Impact of Dietary Glutamate on Growth Performance and Flesh Quality of Largemouth Bass. Fishes 2025, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.Y.; Liu, M.Y.; Cheng, H.H.; Li, X.F.; Jiang, G.Z. Replacing fish meal with cottonseed meal protein hydrolysate affects amino acid metabolism via AMPK/SIRT1 and TOR signaling pathway of Megalobrama amblycephala. Aquaculture 2019, 510, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Q.; Luo, J.; Xie, Y. Effects of cottonseed protein concentrate on growth performance, hepatic function and intestinal health in juvenile largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 23, 101052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 2012, 149, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Sahra, I.; Manning, B.D. mTORC1 signaling and the metabolic control of cell growth. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 45, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efeyan, A.; Comb, W.C.; Sabatini, D.M. Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and pathways. Nature 2015, 517, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, B.D.; Cantley, L.C. AKT/PKB signaling: Navigating downstream. Cell 2007, 129, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena, J.J.; Alonso, M.E.; Gómez-Skarmeta, J.L. Comparative epigenomics in distantly related teleost species identifies conserved cis-regulatory nodes active during the vertebrate phylotypic period. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiliez, I.; Taty-Catala, G.; Dias, K.; Sabin, N.; Gabillard, J.-C. Myostatin induces atrophy of trout myotubes through inhibiting the TORC1 signaling and promoting ubiquitin–proteasome and autophagy-lysosome degradative pathways. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2013, 186, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. Hyperandrogenism in POMCa-deficient zebrafish enhances somatic growth without increasing adiposity. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 12, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Association analysis between feed efficiency and expression of key genes of the avTOR signaling pathway in meat-type ducks. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 3537–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-L.; Li, X.-M.; Cheng, Y.-X.; Liang, J.; Lin, H.-R.; Zhang, Y. The regulation of rapamycin on nutrient metabolism in Nile tilapia fed with high-energy diet. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, J. Feasibility evaluation of cottonseed protein concentrate to replace soybean meal in the diet of juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus): Growth performance, antioxidant capacity, intestinal health and microflora composition. Aquaculture 2024, 593, 741328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Liu, Y.J.; Tian, L.X.; Mai, K.S.; Liang, G.Y.; Yang, H.J.; Huai, M.Y.; Luo, W.J. Effect of dietary carbohydrate-to-lipid ratios on growth performance, body composition, nutrient utilization and hepatic enzymes activities of herbivorous grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquac. Nutr. 2010, 16, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.-Q.; Li, X.-F.; Jiang, G.-Z.; Zhou, H.-H.; Wang, L. The metabolomics responses of Chinese mitten-hand crab (Eriocheir sinensis) to different dietary oils. Aquaculture 2017, 479, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Qin, B.; Chang, Q. Effect of graded levels of taurine on growth performance and Ptry expression in the tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis) postlarvae. Aquac. Nutr. 2016, 22, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.W.; Tacon, A.G.J. Fish meal: Historical uses, production trends and future outlook for supplies. In Responsible Marine Aquaculture; Stickney, R.R., McVey, J.P., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2002; pp. 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Onomu, A.J.; Okuthe, G.E. The role of functional feed additives in enhancing aquaculture sustainability. Fishes 2024, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köprücü, K.; Sertel, E. The effects of less-expensive plant protein sources replaced with soybean meal in the juvenile diet of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella): Growth, nutrient utilization and body composition. Aquac. Int. 2012, 20, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linga Prabu, D.; Karthik, M.; Sivakumar, N.; Prabu, C. Cottonseed protein concentrate as an alternate protein source for fishmeal replacement in aquafeeds: Production optimisation and its nutritive profile. Indian J. Fish. 2021, 68, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yones, A.M.; Abdel-Hakim, N.F. Study on growth performances and apparent digestibility coefficients of some common plant protein ingredients used in formulated diets of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Egypt. J. Nutr. Feed. 2010, 13, 589–606. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z. Dephenolization methods, quality characteristics, applications, and advancements of dephenolized cottonseed protein. Foods 2025, 14, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2021: Sustainability in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, I.A.; Nazir, S. Gossypol. In Handbook of Plant and Animal Toxins in Food; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Krempl, C.; Heidel-Fischer, H.M.; Jiménez-Alemán, G.H. Gossypol toxicity and detoxification in Helicoverpa armigera and Heliothis virescens. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 78, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Qian, K.; Liu, H.; Song, F.; Ye, J. Effects of fish meal replacement with low-gossypol cottonseed meal on the intestinal barrier of juvenile golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Aquac. Res. 2022, 53, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Pasnik, D.; Yildirim-Aksoy, M.; Lim, C.; Klesius, P. Histologic changes in channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus Rafinesque, fed diets containing graded levels of gossypol-acetic acid. Aquac. Nutr. 2010, 16, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Jiang, G.; Cheng, H.; Cao, X.; Shi, H.; Liu, W. An evaluation of replacing fish meal with cottonseed meal protein hydrolysate in diet for juvenile blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala): Growth, antioxidant, innate immunity and disease resistance. Aquaculture Nutrition 2019, 25, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim-Aksoy, M. Growth Performance and Disease Resistance of Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) Fed Diets Containing Natural Gossypol and Gossypol-Acetic Acid. Doctoral Dissertation, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Jiang, W.; Wu, P.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J. Gossypol reduced the intestinal amino acid absorption capacity of young grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture 2018, 492, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.F.; Kwan, S.H.; Lim, B.K. Cottonseed meal protein isolate as a new source of alternative proteins: A proteomics perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tayyar, O.B.A.; Al-Beiati, M.A.; Al-Ubade, S.A. Gossypol effect in some blood parameters, enzymes and pathology of male common carp Cyprinus carpio L. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 2009, 33, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Guerrero, K.; Marches, M.; Duru, M.; Magrini, M.-B.; Meynard, J.-M. Plant proteins for human and environmental health: Knowledge, barriers, and levers for their development, a case study in France. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 45, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Ren, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhou, D.; Tang, S.; Kuang, M.; Du, S. Physicochemical and functional properties of protein isolate obtained from cottonseed meal. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Torres-Lechuga, M.E.; Lei, Y.; Yu, P. Protein molecular structural, physicochemical and nutritional characteristics of warm-season adapted genotypes of sorghum grain: Impact of heat-related processing. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 87, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Li, D.; Zhou, Y. Impacts of dietary protein from fermented cottonseed meal on lipid metabolism and metabolomic profiling in the serum of broilers. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2020, 21, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, J.; He, Z.; Du, R. Plant-derived as alternatives to animal-derived bioactive peptides: A review of the preparation, bioactivities, structure–activity relationships, and applications in chronic diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Q.; Ni, X.; Zeng, L.; Jiang, J.; Li, D. Optimization of protein extraction and decoloration conditions for tea residues. Hortic. Plant J. 2017, 3, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-J.; Xu, Z.-R.; Zhao, S.-H.; Jiang, J.-F.; Wang, Y.-B.; Yan, X.-H. Development of a microbial fermentation process for detoxification of gossypol in cottonseed meal. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2007, 135, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Potkule, J.; Patil, S.; Morya, S.; Singh, M.; Punia, S. Extraction of ultra-low gossypol protein from cottonseed: Characterization based on antioxidant activity, structural morphology and functional group analysis. LWT 2021, 140, 110692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Tomar, M.; Punia, S.; Grasso, S.; Changan, S.; Dhumal, S.; Singh, S. Cottonseed: A sustainable contributor to global protein requirements. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, N.W.; Bernard, J.K.; Tao, S. Production responses to diets supplemented with soybean meal, expeller soybean meal, or dry-extruded cottonseed cake by lactating dairy cows. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2019, 35, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunneley, J.L.; Barnes, M.E.; Gibon, V.P.; Pelletier, M.G. Development of a cottonseed dehulling process to yield intact seed meats. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2013, 29, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, M. Food and nutrition (cotton as a feed and food crop). In Cotton Sector Development in Ethiopia: Challenges and Opportunities; Kebede, M., Ed.; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2024; pp. 379–412. [Google Scholar]

- Hensley, D.W.; Hansen, A.P.; Sorensen, C.M.; Glatz, C.E. A study of factors affecting membrane performance during processing of cottonseed protein extracts by ultrafiltration. J. Food Sci. 1977, 42, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhuzantye, T.; Khaire, R.A.; Gogate, P.R. Enhancing the recovery of whey proteins based on application of ultrasound in ultrafiltration and spray drying. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2019, 55, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chapital, D.C.; Cheng, H.N.; Dowd, M.K. Effects of particle size on the morphology and water-and thermo-resistance of washed cottonseed meal–based wood adhesives. Polymers 2017, 9, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, R.B. Cottonseed toxicity. In Veterinary Toxicology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 973–986. [Google Scholar]

- Ninkuu, V.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, B. The nutritional and industrial significance of cottonseeds and genetic techniques in gossypol detoxification. Plants People Planet 2024, 6, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, M.; Luo, X.; Fan, Y.; Zheng, Z.; He, Z.; Pan, Y. Intramolecular annulation of gossypol by laccase to produce safe cottonseed protein. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 583176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.; Xiong, F.; Pei, S.; Huang, Q.; He, Z. Synergistic fermentation of cottonseed meal using Lactobacillus mucosae LLK-XR1 and acid protease: Sustainable production of cottonseed peptides and depletion of free gossypol. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.P.; Wang, Y.A.; Liu, Y.R.; Ma, Q.G.; Ji, C.; Zhao, L.H. Detoxification of the mycoestrogen zearalenone by spore CotA laccase and application of immobilized laccase in contaminated corn meal. LWT 2022, 163, 113548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.X.; Li, X.Y.; He, Y.; Li, M. Intestinal microbiota mediates gossypol-induced intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in fish. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6688–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Guo, Y. Effective degradation of free gossypol in defatted cottonseed meal by bacterial laccases: Performance and toxicity analysis. Foods 2024, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghinejad-Roudbaneh, M.; Ebrahimi, S.R.; Azizi, O. Influence of roasting, gamma ray irradiation and microwaving on ruminal dry matter and crude protein digestion of cottonseed. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 15, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, F.; Ghoorchi, T.; Shawrang, P.; Mansouri, H.; Torbati Nejad, N.M. Comparison of electron beam and gamma ray irradiations effects on ruminal crude protein and amino acid degradation kinetics, and in vitro digestibility of cottonseed meal. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2012, 81, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaddou, H.; Al-Hakim, M.; Al-Adamy, L.Z.; Mhaisen, M.T. Effect of gamma-radiation on gossypol in cottonseed meal. J. Food Sci. 1983, 48, 988–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.