Right-Biassed Crystalline Lens Asymmetry in the Thornback Ray (Rajiformes: Rajidae: Raja clavata): Implications for Ocular Lateralisation in Cartilaginous Fish

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Single-predictor models: W, Age, TL, Sex, and Site (fixed factor).

- Additive two-predictor models: W + TL, W + Sex, TL + Sex.

- Full additive: W + TL + Sex.

- Interaction: W × TL,

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Lens Asymmetry

3.2. Directionality of Asymmetry

3.3. Predictors of Asymmetry

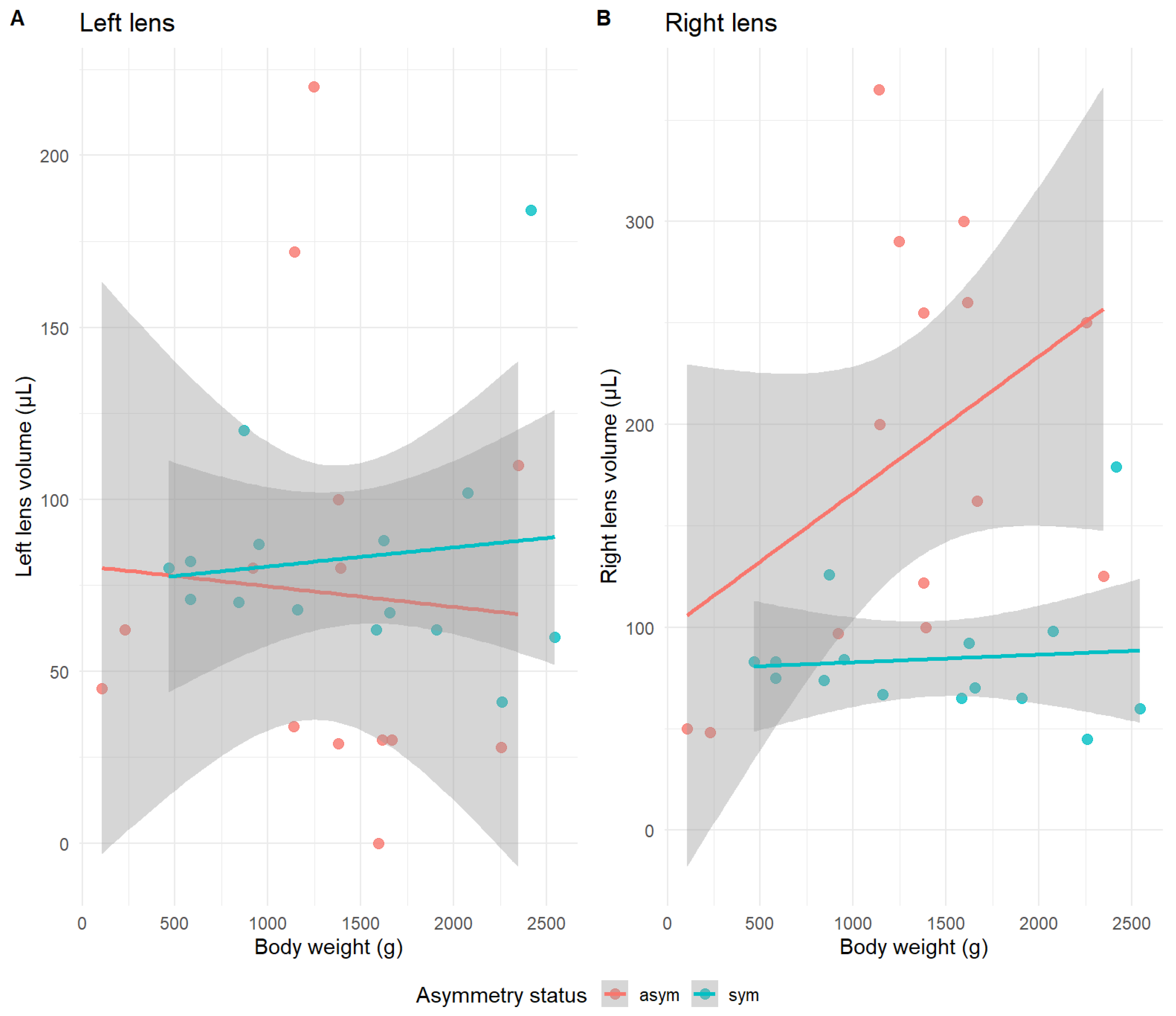

3.4. Lens Size Differences in Function of Body Weight

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterisation of Crystalline Lens Asymmetry

4.2. Structural and Directional Constraints on Possible Mechanisms

4.3. Predictors of Asymmetry and Ontogenetic Scaling

4.4. Functional Lateralisation Versus Asymmetric Degeneration

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DA | Directional asymmetry |

| TL | Total length |

| W | Weight |

| 3VBGF | Von Bertalanffy Growth Equation |

References

- Holló, G. Demystification of Animal Symmetry: Symmetry Is a Response to Mechanical Forces. Biol. Direct 2017, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.H.; Raz, S.; Hel-Or, H.; Nevo, E. Fluctuating Asymmetry: Methods, Theory, and Applications. Symmetry 2010, 2, 466–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongen, S.V. Fluctuating Asymmetry and Developmental Instability in Evolutionary Biology: Past, Present and Future. J. Evol. Biol. 2006, 19, 1727–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiper, M.L. Evolutionary and Mechanistic Drivers of Laterality: A Review and New Synthesis. Laterality 2017, 22, 740–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.R. Animal Asymmetry. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, R473–R477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovrano, V.A. Visual Lateralization in Response to Familiar and Unfamiliar Stimuli in Fish. Behav. Brain Res. 2004, 152, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallortigara, G.; Chiandetti, C.; Sovrano, V.A. Brain Asymmetry (Animal). Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2011, 2, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Chen, H.-M. Directional Asymmetry in Gonad Length Indicates Moray Eels (Teleostei, Anguilliformes, Muraenidae) Are “Right-Gonadal”. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirlanda, S.; Vallortigara, G. The Evolution of Brain Lateralization: A Game-Theoretical Analysis of Population Structure. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2004, 271, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahé, K.; MacKenzie, K.; Ider, D.; Massaro, A.; Hamed, O.; Jurado-Ruzafa, A.; Gonçalves, P.; Anastasopoulou, A.; Jadaud, A.; Mytilineou, C.; et al. Directional Bilateral Asymmetry in Fish Otolith: A Potential Tool to Evaluate Stock Boundaries? Symmetry 2021, 13, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisney, T.J.; Collin, S.P. Retinal Ganglion Cell Distribution and Spatial Resolving Power in Elasmobranchs. Brain Behav. Evol. 2008, 72, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, B. Flatfish Metamorphosis, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; ISBN 9789811978586. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, J.E. The Optics of Life: A Biologist’s Guide to Light in Nature. Sonke Johnsen. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2012, 52, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.N. Vision and Bioluminescence in Cephalopods. Ph.D. Thesis, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, V.F.L.; Glaser, Y.; Iwashita, M.; Yoshizawa, M. Evolution of Left-Right Asymmetry in the Sensory System and Foraging Behavior during Adaptation to Food-Sparse Cave Environments. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall-Bar, J.M.; Vyssotski, A.L.; Mukhametov, L.M.; Siegel, J.M.; Lyamin, O.I. Eye State Asymmetry during Aquatic Unihemispheric Slow Wave Sleep in Northern Fur Seals (Callorhinus ursinus). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Russi, G.; Bertolucci, C.; Lucon-Xiccato, T. Artificial Light at Night Impairs Visual Lateralisation in a Fish. J. Exp. Biol. 2025, 228, JEB249272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Higuchi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Oda, Y. Dominant Eye-Dependent Lateralized Behavior in the Scale-Eating Cichlid Fish, Perissodus microlepis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenbach, D.M. Fluctuating Asymmetry and Exogenous Stress in Fishes: A Review. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2011, 21, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongen, V.; Lens; Molenberghs. Mixture Analysis of Asymmetry: Modelling Directional Asymmetry, Antisymmetry and Heterogeneity in Fluctuating Asymmetry. Ecol. Lett. 1999, 2, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulbay, M.; Wu, K.Y.; Nirwal, G.K.; Bélanger, P.; Tran, S.D. Oxidative Stress and Cataract Formation: Evaluating the Efficacy of Antioxidant Therapies. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, B.; Lal, K.; Liu, H.; Tran, M.; Zhou, M.; Ezugwu, C.; Gao, X.; Dang, T.; Au, M.-L.; et al. Antioxidant System and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Cataracts. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 4041–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, S.; Nania, G.; Caruso, V.; Zicarelli, G.; Leonetti, F.L.; Giglio, G.; Fedele, G.; Romano, C.; Bottaro, M.; Mangoni, O.; et al. Bioaccumulation of Trace Elements in the Muscle of the Blackmouth Catshark Galeus melastomus from Mediterranean Waters. Biology 2023, 12, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte, P.; South, A. Rnaturalearth: World Map Data from Natural Earth, CRAN[Code]. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/ropensci/rnaturalearth (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Carbonara, P.; Bellodi, A.; Palmisano, M.; Mulas, A.; Porcu, C.; Zupa, W.; Donnaloia, M.; Carlucci, R.; Sion, L.; Follesa, M.C. Growth and Age Validation of the Thornback Ray (Raja clavata Linnaeus, 1758) in the South Adriatic Sea (Central Mediterranean). Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 586094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. A Quantitative Theory of Organic Growth (Inquiries on Growth Laws. Ii). Hum. Biol. 1938, 10, 181–213. [Google Scholar]

- Dale Broder, E.; Angeloni, L.M. Predator-Induced Phenotypic Plasticity of Laterality. Anim. Behav. 2014, 98, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayon, J. History of the Concept of Allometry. Am. Zool. 2000, 40, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Robertis, A.; Williams, K. Weight-length Relationships in Fisheries Studies: The Standard Allometric Model Should Be Applied with Caution. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2008, 137, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.R. Symmetry Breaking and the Evolution of Development. Science 2004, 306, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staeudle, T.M.; Parmentier, B.; Poos, J.J. Accounting for Spatio-Temporal Distribution Changes in Size-Structured Abundance Estimates for a Data-Limited Stock of Raja clavata. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2024, 81, 1607–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstulović Šifner, S.; Vrgoč, N.; Dadić, V.; Isajlović, I.; Peharda, M.; Piccinetti, C. Long-Term Changes in Distribution and Demographic Composition of Thornback Ray, Raja clavata, in the Northern and Central Adriatic Sea. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2009, 25, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahti, P.A.; Kuparinen, A.; Uusi-Heikkilä, S. Size Does Matter—The Eco-Evolutionary Effects of Changing Body Size in Fish. Environ. Rev. 2020, 28, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, D.C.; Johnson, N.A.; Ajie, B.C.; Otto, S.P.; Hendry, A.P.; Blumstein, D.T.; Coss, R.G.; Donohue, K.; Foster, S.A. Relaxed Selection in the Wild. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascetti, G.G. Unihemispheric Sleep and Asymmetrical Sleep: Behavioral, Neurophysiological, and Functional Perspectives. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2016, 8, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsueh, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.-N.; Tsao, Y.-T.; Cheng, C.-M.; Wu, W.-C.; Chen, H.-C. The Pathomechanism, Antioxidant Biomarkers, and Treatment of Oxidative Stress-Related Eye Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodella, U.; Honisch, C.; Gatto, C.; Ruzza, P.; D’Amato Tóthová, J. Antioxidant Nutraceutical Strategies in the Prevention of Oxidative Stress Related Eye Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyane, T.S.; Jere, S.W.; Houreld, N.N. Oxidative Stress in Ageing and Chronic Degenerative Pathologies: Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Counteracting Oxidative Stress and Chronic Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borucinska, J.D.; Benz, G.W.; Whiteley, H.E. Ocular Lesions Associated with Attachment of the Parasitic Copepod Ommatokoita elongata (Grant) to Corneas of Greenland Sharks, Somniosus microcephalus (Bloch & Schneider): Ocular Lesions Associated with Parasitic Copepods. J. Fish Dis. 1998, 21, 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. Ophthalmology of Cartilaginous Fish: Skates, Rays, and Sharks. In Wild and Exotic Animal Ophthalmology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerlands, 2022; pp. 47–59. ISBN 9783030713010. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, G.; Lecomte-Finiger, R.; Bartrina, J.; Moné, H.; Sasal, P. Macroparasite Community and Asymmetry of the Yellow Eel Anguilla anguilla in Salses-Leucate Lagoon, Southern France. Bull. Fr. Peche Piscicult. 2005, 378–379, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pečínková, M.; Vøllestad, L.A.; Koubková, B.; Huml, J.; Jurajda, P.; Gelnar, M. The Relationship between Developmental Instability of Gudgeon Gobio gobio and Abundance or Morphology of Its Ectoparasite Paradiplozoon homoion (Monogenea). J. Fish Biol. 2007, 71, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, R.; Vacca, L.; Cariani, A.; Carugati, L.; Charilaou, C.; Di Crescenzo, S.; Ferrari, A.; Follesa, M.C.; Mancusi, C.; Pinna, V.; et al. Baseline Genetic Distinctiveness Supports Structured Populations of Thornback Ray in the Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Conserv. 2023, 33, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.A.; Dando, M.; Fowler, S. Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Model | Predictor | Effect Size | p-Value | AIC | ΔAIC | Akaike Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Age | 1.23 [0.98, 1.59] | 0.0803 | 72.37 | 0.00 | 0.201 |

| W | Weight | 1.71 [1.02, 2.99] | 0.0425 | 72.92 | 0.55 | 0.153 |

| INT | Weight | 2.46 [0.47, 13.02] | 0.2730 | 73.43 | 1.06 | 0.118 |

| Total length | 0.64 [0.13, 3.15] | 0.5690 | 73.43 | 1.06 | 0.118 | |

| Weight × Total length | 1.00 [0.63, 1.71] | 0.9960 | 73.43 | 1.06 | 0.118 | |

| WS | Weight | 1.62 [0.95, 2.87] | 0.0773 | 73.46 | 1.09 | 0.117 |

| Sex: male vs. female | 0.69 [0.22, 2.16] | 0.5240 | 73.46 | 1.09 | 0.117 | |

| WTL | Weight | 2.47 [0.64, 10.02] | 0.1880 | 74.03 | 1.67 | 0.087 |

| Total length | 0.65 [0.16, 2.81] | 0.5500 | 74.03 | 1.67 | 0.087 | |

| TL | Total length | 1.59 [0.91, 2.94] | 0.1020 | 74.37 | 2.00 | 0.074 |

| FULL | Weight | 2.35 [0.6, 9.61] | 0.2160 | 74.56 | 2.20 | 0.067 |

| Total length | 0.64 [0.16, 2.79] | 0.5460 | 74.56 | 2.20 | 0.067 | |

| Sex: male vs. female | 0.69 [0.22, 2.15] | 0.5210 | 74.56 | 2.20 | 0.067 | |

| TLS | Total length | 1.49 [0.85, 2.79] | 0.1690 | 74.70 | 2.34 | 0.063 |

| Sex: male vs. female | 0.65 [0.21, 1.99] | 0.4470 | 74.70 | 2.34 | 0.063 | |

| S | Sex: male vs. female | 0.53 [0.18, 1.55] | 0.2490 | 77.09 | 4.72 | 0.019 |

| NULL | 77.60 | 5.23 | 0.015 | |||

| SITE | Cala_11 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 |

| Cala_112 | 1.29 [0.04, 234.63] | 0.8940 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_116 | 0.27 [0, 61.13] | 0.5620 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_119 | 3.00 [0.07, 612.54] | 0.5700 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_13 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_41 | 1.80 [0.05, 339.13] | 0.7560 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_51 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_54 | 0.23 [0, 51.35] | 0.5130 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_56 | 0.60 [0, 142.76] | 0.8210 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_61 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_74 | 1.59 [0.07, 251.77] | 0.7840 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_77 | 9.00 [0.15, 3674.77] | 0.3060 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_78 | 0.88 [0.03, 145.57] | 0.9440 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_8 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| Cala_81 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| RC_CAMP_BIO_25_1 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| RC_CAMP_BIOL_1 | 2.14 [0.07, 369.65] | 0.6670 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| RC_CAMP_BIOL_2 | 3.00 [0.1, 534.3] | 0.5380 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| RC_CAMP_BIOL_3 | 3.00 [0.07, 612.54] | 0.5700 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| RC_CAMP_BIOL_4 | 9.00 [0.15, 3674.77] | 0.3060 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| RC_P._COMM._1 | 3.00 [0.07, 612.54] | 0.5700 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| RC_P._COMM._4 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| SiteRC_P._COMM_2_24 | 0.60 [0, 142.76] | 0.8210 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 | |

| SiteRC_P._COMM_3_24 | 1.00 [0, 257.8] | 1.0000 | 139.83 | 67.46 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fedele, G.; Rima, P.C.; Gallo, S.; Carpino, C.; Valerioti, C.; Giglio, G.; Leonetti, F.L.; Milazzo, C.; Piredda, L.; Zaccaroni, A.; et al. Right-Biassed Crystalline Lens Asymmetry in the Thornback Ray (Rajiformes: Rajidae: Raja clavata): Implications for Ocular Lateralisation in Cartilaginous Fish. Fishes 2026, 11, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010009

Fedele G, Rima PC, Gallo S, Carpino C, Valerioti C, Giglio G, Leonetti FL, Milazzo C, Piredda L, Zaccaroni A, et al. Right-Biassed Crystalline Lens Asymmetry in the Thornback Ray (Rajiformes: Rajidae: Raja clavata): Implications for Ocular Lateralisation in Cartilaginous Fish. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleFedele, Giorgio, Patrizia C. Rima, Samira Gallo, Chiara Carpino, Claudia Valerioti, Gianni Giglio, Francesco L. Leonetti, Concetta Milazzo, Laura Piredda, Annalisa Zaccaroni, and et al. 2026. "Right-Biassed Crystalline Lens Asymmetry in the Thornback Ray (Rajiformes: Rajidae: Raja clavata): Implications for Ocular Lateralisation in Cartilaginous Fish" Fishes 11, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010009

APA StyleFedele, G., Rima, P. C., Gallo, S., Carpino, C., Valerioti, C., Giglio, G., Leonetti, F. L., Milazzo, C., Piredda, L., Zaccaroni, A., Sardo, G., Vitale, S., Gancitano, V., & Sperone, E. (2026). Right-Biassed Crystalline Lens Asymmetry in the Thornback Ray (Rajiformes: Rajidae: Raja clavata): Implications for Ocular Lateralisation in Cartilaginous Fish. Fishes, 11(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010009