Abstract

Despite their ecological importance, discarded species with low commercial value are often overlooked in marine research. This study examined the age structure and feeding habits of the large-scaled gurnard (Lepidotrigla cavillone) and the spiny gurnard (Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei) in the Gulf of Cádiz (SW Iberian Peninsula). A total of 225 specimens were collected during 19 fishing trips at depths of 15–550 m. Ages were estimated from otolith readings, and stomach contents were analysed to describe diet composition, niche breadth, and overlap. Both species showed positive allometric growth, with the most frequent age class being 5+ in L. cavillone and 5+–6+ in L. dieuzeidei. Crustaceans dominated the diet, with mysids accounting for >80% of the index of relative importance (IRI) in L. cavillone, but L. dieuzeidei displayed a broader diet including mysids (45% IRI) and decapods (32% IRI). Feeding patterns varied with time of day, depth, and size, reflecting ontogenetic and environmental influences. Levin’s index indicated stronger specialization in L. cavillone (BA = 0.090) than in L. dieuzeidei (BA = 0.208), while the Schoener index (0.575) showed moderate overlap. These findings provide the first biological insights into these discarded species in Atlantic waters, contributing to ecosystem-based fisheries management.

Key Contribution:

Mean total length was 8.3 cm (3.9–14.2 cm) in L. cavillone and 9.3 cm (4.0–13.8 cm) in L. dieuzeidei. Both species showed positive allometric growth, with 5+ being the most abundant age in L. cavillone and 5+–6+ in L. dieuzeidei. Diets were dominated by mysids in L. cavillone (>80% IRI) and by mysids and decapods in L. dieuzeidei (45% and 32% IRI, respectively). Feeding patterns varied with time of day, depth, and size, revealing moderate dietary overlap (Schoener index = 0.575).

1. Introduction

Fishing has undergone remarkable technical evolution, progressing from local and artisanal practices to the development of factory and industrial vessels [1,2]. However, fishing is not without problems arising from its activity, one of the most important being discards, which account for a significant portion of the catch, representing up to 10% of the annual global catch (9.1 million out of 84.4 million tonnes) in 2018 [3]. Discards refer to the practice of returning unwanted or undersized fish, or other marine organisms caught as by-catch, back into the sea, whether dead or alive [4]. These discards cause alterations in the marine environment, such as imbalances in food webs, due to the disruption of interactions between species and the elimination of links in the food chain. However, they also provide feeding opportunities by making large quantities of easily accessible and catchable food resources available to numerous wild species populations [5,6]. Therefore, studying the age and feeding structure of discarded species is essential for proper ecosystem-based fisheries management.

In Spain, trawl fisheries generate considerable amounts of discards, which include species of low commercial value. Among these discarded species are those belonging to the Triglidae family: the large-scale gurnard (Lepidotrigla cavillone) and the spiny gurnard (Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei). These are two small benthic species, which can reach up to 20 cm in length [7,8], inhabiting sandy and muddy bottoms at depths of 20–350 m. They are distributed throughout the North-East Atlantic, from France to Mauritania, including the Mediterranean Sea [9]. Both L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei are of little commercial interest; despite the fact that in 2023 some 310 tonnes of L. cavillone and 6 tonnes of L. dieuzeidei were caught between Italy, Portugal, and Spain [10], they are commonly discarded by the trawling fleet [11]. Several studies have been conducted throughout the Mediterranean Sea on the feeding [12,13,14], reproduction and growth [15,16,17,18,19], and general biology [20] of both species, with more research focused on L. cavillone than on L. dieuzeidei. However, in Atlantic waters, there is a clear lack of studies on the biology of both species.

Therefore, due to the prevalence of both species in fishing discards and the limited information available on them in the North-East Atlantic, particularly in the south-west of the Iberian Peninsula, the objectives of this study were: (1) to determine the ages of L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei specimens caught and discarded by the trawl fleet in the Gulf of Cádiz; (2) to investigate the diet and feeding habits of both species, as well as their variations according to time of day, depth, and size; and (3) to calculate possible overlaps in the diet of both species in the environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Design

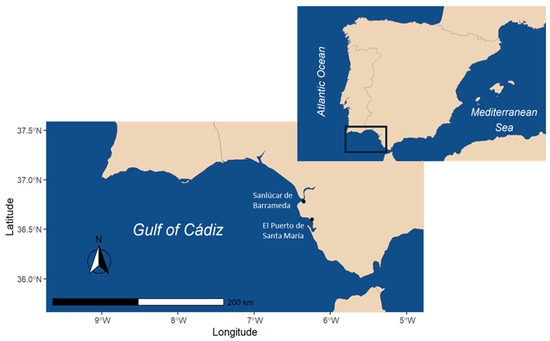

The study area is located in the Gulf of Cádiz (Figure 1), in the southwestern Iberian Peninsula (36°51′ N, 06°55′ W), encompassing 407 km of coastline from the mouth of the Guadiana River to Tarifa [21]. This region is characterized by high biodiversity, ranging from plankton to cetaceans [22], and holds significant importance for fisheries. Its productivity is enhanced by the exchange of mass and energy with the Guadalquivir and Guadiana rivers [23], the connection between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea via the Strait of Gibraltar, and the easterly winds that promote both primary and secondary production [24,25]. These conditions make the areas near river mouths key nursery habitats for juvenile species [22,26], and they support commercially valuable fishing grounds where species such as Norway lobster (Nephrops norvegicus), European hake (Merluccius merluccius), deep-water rose shrimp (Parapenaeus longirostris), blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou), monkfish (Lophius spp.), and wedge sole (Dicologlossa cuneata) are harvested by both artisanal and trawl fleets [27].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area (Gulf of Cádiz, SW Iberian Peninsula). The black dots represent the two ports of origin of the trawl fleet.

Samples of both target species were obtained through the ECOFISH+, and ECOFISH 4.0. projects, by participating in fishing trips with the artisanal trawl fleets operating out of Sanlúcar de Barrameda and Puerto de Santa María. The ECOFISH project, through its successive phases (ECOFISH 2, ECOFISH+, and ECOFISH 4.0.), has promoted sustainable fisheries in the Gulf of Cádiz. Across these stages, the project has assessed and characterized the discards produced by the trawling fleet, implemented initiatives to study interactions between fisheries and seabirds, and addressed the issue of marine litter collected by trawlers in the Gulf of Cádiz. During the trips, approximately 10 kg of discards were randomly collected from each haul and stored in separate containers on board for transport to the laboratory. A total of 19 trips were made between 2021–2022 (~2 trips per month), with three hauls per trip, at depths ranging from 15 to 550 m, which are the typical operational depths of the local trawl fleet. Sampling was opportunistic, based on trawl fishery discards that reflected the natural occurrence of each species in the discard fraction. No samples were collected between 15 September and 31 October due to the closed season for the trawl fishery in the Gulf of Cádiz. The fishing gear complied with the legal minimum cod-end mesh size of 100 mm, as established in [28]. The typical trawling speed of the demersal fleet operating in the Gulf of Cádiz ranges between 2.5 and 3.5 knots, consistent with regional scientific surveys. Once in the laboratory, the samples were sorted by species, identified, and labeled for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Sampling Process

Specimens were identified using the identification guide by [29], and their biometric measurements were taken using an ichthyometer (Aquatic Biotechnology, El Puerto de Santa María, Cádizm, Spain) with a precision of ±0.1 cm. Total length (TL) was recorded. A digital scale (Auxilab. Beriáin, Navarra, Spain) with a precision of ±0.01 g was used to determine total weight (TW) and gutted weight (GW), while a precision scale (±0.0001 g) was employed to measure the weight of the full digestive tract (Dig. full) and the empty digestive tract (Dig. empty).

After biometric measurements, both otoliths and stomach contents were extracted. Cleaned otoliths were stored dry in 0.5 mL Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf SE, Hamburgo, Germany) for subsequent analysis. Stomach contents were preserved in 5 mL vials containing 70% ethanol for later examination.

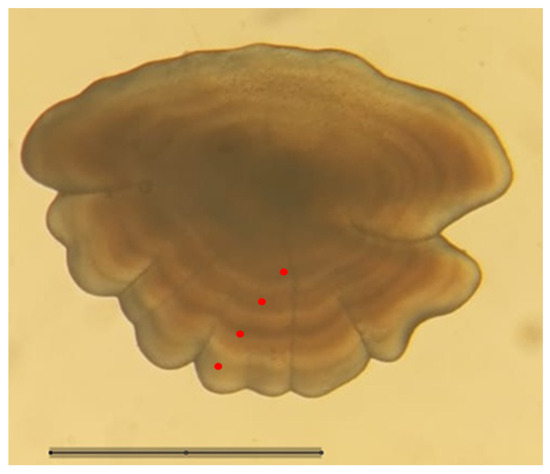

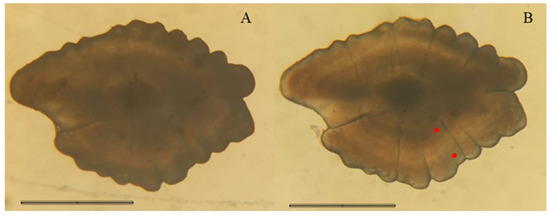

To determine specimen age, otoliths were analyzed by counting growth rings under a Leica Wild M10 stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) with bottom lighting. In L. cavillone, the rings were clearly visible without any prior treatment (Figure 2). In contrast, due to the greater thickness of L. dieuzeidei otoliths, they were clarified in a 1:1 solution of ethanol and glycerol for 10–15 min prior to reading (Figure 3). Each otolith was read twice by two independent observers. Discrepant readings were discarded following the criteria established by [30] for distinguishing true growth rings from false rings.

Figure 2.

Right saggitae otolith of large-scaled gurnard (L. cavillone) without any clarification process. Growth rings are marked with red dots. Scale bar: 1 mm. Total Length (TL) = 9.7 cm.

Figure 3.

Left saggitae otolith of spiny gurnard (L. dieuzeidei) before (A) and after the clearing process (B). Growth rings are marked with red dots. Scale bar: 1 mm. Total Length (TL) = 4.0 cm.

Stomach contents of each specimen were analyzed using a Leica Wild M10 stereomicroscope, with all identifiable items being counted and taxonomically classified to the lowest possible level using the identification manual by [31]. The various prey items in each sample were then sorted, preserved in 0.5 mL Eppendorf tubes containing 70% ethanol, and weighed individually using an Explorer Semi-Micro EX125D scale (Ohaus, Parsippany-Troy Hills, NJ, USA) with an accuracy of ±10−5 g.

2.3. Data Analysis

To assess changes in body length during the development of both species and to accurately describe the total length (TL) frequency distribution, histograms were constructed for each species using 2 cm length classes. The Length–Weight Relationship (LWR) was calculated following the equation proposed by [32]:

where TW is the total weight in g, TL is the total length in cm.

The parameters of the LWR were estimated following the least squares method using linear regression:

The parameter a provides information about the species’ body form, while b indicates the type of growth. A value of b = 3 suggests isometric growth, proportional increases in length and weight. Values of b < 3 indicate negative allometric growth (greater increase in length than in weight), whereas b > 3 suggests positive allometric growth (greater increase in weight relative to length) [33]. A chi-squared test was used to assess significant differences in abundance among age classes in relation to time of day and depth.

For individuals with empty stomachs, the vacuity index (Vi) was calculated as:

The use of specific resources by individuals was expressed through the frequency of occurrence (%Fi):

The numerical percentage (%Cni), representing the proportion of each prey type relative to the total number of prey items found, was calculated as:

The gravimetric percentage (%Cwi), reflecting the contribution of each prey type by weight, was calculated as:

The overall importance of each prey item was assessed using the Index of Relative Importance (IRI), according to the modified formula by [34]:

Dietary niche breadth was calculated using Levin’ standardized index (BA):

where pj is the proportion of individuals consuming resource j (or the proportion of resource j in the total diet), and n is the total number of prey categories. The index ranges from 0 to 1, where lower values indicate dietary specialization (few prey types consumed), and higher values indicate generalist feeding behavior (diverse diet) [35,36].

The possible overlap between the diets of both species was studied using the Schoener index (Ojk):

In this index, pji and pki represent the estimated proportions by weight of prey item i in the diets of species j and k, respectively. The value of the overlap index varies on a scale between 0 and 1 depending on the taxonomic level at which the food items are identified [37]. Langton’s convention [38] has been used, which classifies the overlap index into three ranges: 0.00–0.29, low similarity; 0.30–0.60, medium similarity; and >0.60, high similarity, with the closer to 1, the greater the similarity between the diets of the two species.

For the analysis of the diet according to the time of day when the specimens were caught, the hauls were divided according to the time when they were carried out, with Haul 1 being at night (between 5 a.m. and 9 a.m.), Haul 2 in the morning (between 9 a.m. and 1 p.m.) and Haul 3 in the afternoon (between 1 p.m. and 5 p.m.). Based on depth, L. cavillone grouped into two depth intervals: <45 m and >45 m. On the other hand, L. dieuzeidei grouped into three depth ranges: <45 m, 45 m to 80 m, and >80 m. In terms of size, both species were classified into 2 cm intervals, from 3–5 cm (the smallest) to 13–15 cm (the largest).

To accurately assess the diet of both species, it was essential to determine the minimum number of stomachs required for analysis. This was achieved by comparing the cumulative number of prey taxa with the cumulative number of randomly selected stomachs. The appearance of an asymptotic curve indicated that a sufficient number of samples had been collected to reliably characterize the diet of the species [39,40,41]. To reduce potential bias, stomachs were randomly resampled 500 times.

A permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted to detect significant differences in prey abundance according to time of day, depth, and size class. This analysis was based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity indices [42], and p-values were obtained through 9999 unrestricted permutations of the data [43,44,45].

Additionally, a one-way Analysis of Similarities (ANOSIM) was used to evaluate differences in dietary composition across time of the day, depth, and size categories. ANOSIM compares mean inter-group distances with intra-group distances using a Bray–Curtis similarity matrix, which is widely applied in ecological studies to assess community composition. The Bray–Curtis index ranges from 0 (indicating identical species proportions across samples) to 1 (completely different species in each sample), providing a more nuanced view of dietary variability than presence/absence data alone [41]. After constructing the dissimilarity matrix, ANOSIM produced two main metrics: a p-value indicating statistical significance, and an R-statistic that measures the degree of dissimilarity between groups. An R-value close to 1 reflects strong differences among groups, while values near 0 suggest no meaningful separation [46,47].

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.1.3; [48]), with a significance level (α) set at 0.05. The following packages were used: “tidyverse” [49]—including “dplyr” [50] and “ggplot2” [51]—“lubridate” [52], “vegan” [53], “reshape2” [54], “forcats” [55], “modelr” [56], “gridExtra” [57], and “devtools” [58].

3. Results

3.1. Biometric Analysis

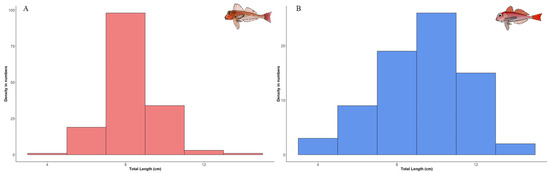

A total of 151 specimens of L. cavillone and 74 specimens of L. dieuzeidei were obtained. The mean total length (TL) of L. cavillone was 8.34 ± 1.38 cm, ranging from 3.9 to 14.2 cm. The mean total weight was 5.9 ± 3.7 g, ranging from 0.44 to 33.33 g. In the case of L. dieuzeidei, the mean TL was 9.33 ± 2.10 cm, with values ranging from 4.0 to 13.8 cm. The mean total weight was 9.61 ± 6.22 g, ranging from 0.5 to 27.81 g. For L. cavillone, most individuals measured between 7 and 9 cm, whereas for L. dieuzeidei, most were between 7 and 11 cm (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Size distribution of L. cavillone (A) and L. dieuzeidei (B) captured in the study.

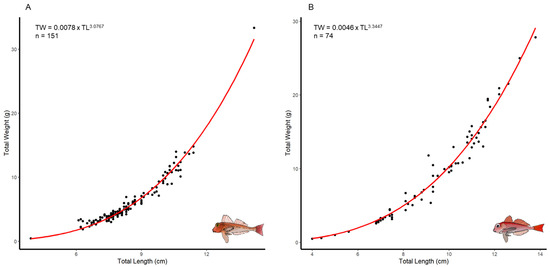

The length–weight relationship (LWR) for L. cavillone had parameters of a = 0.008 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.006–0.010) and b = 3.077 (95%CI: 2.965–3.189), with R2 = 0.9628 (Figure 5A). For L. dieuzeidei, the LWR parameters were a = 0.005 (95% CI: 0.004–0.006) and b = 3.345 (95% CI: 3.233–3.457), with R2 = 0.9671 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Length–Weight Relationship of (A) Lepidotrigla cavillone and (B) L. dieuzeidei in the Gulf of Cádiz (SW Iberian Peninsula). The red line indicates the relationship adjustment line.

3.2. Age Determination

Otoliths were extracted from 151 specimens of L. cavillone and 71 specimens of L. dieuzeidei, with the minimum age recorded being 3 years for L. cavillone and 2 years for L. dieuzeidei (Table 1). In both species, the maximum age was 8 years. Most specimens of L. cavillone were aged 5+ years (46.36%), whereas for L. dieuzeidei, the most common ages were 5+ (35.62%) and 6+ (34.25%).

Table 1.

Statistical summary of the lengths and ages of large-scaled gurnard (Lepidotrigla cavillone) and of spiny gurnard (Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei) present in discards from the Gulf of Cádiz. n: Sample size, % Percentage of age class to total; TL: Total length.

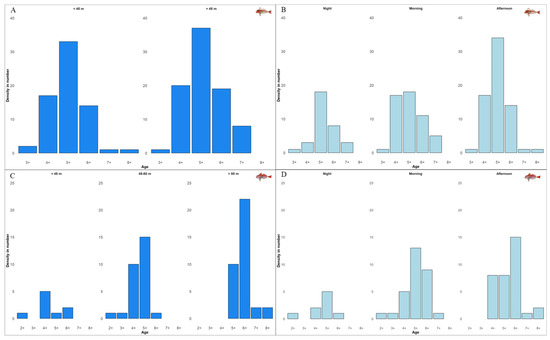

The abundance of different age classes was analyzed according to time of day (Figure 6A,B) and depth (Figure 6C,D). With respect to time of day, neither L. cavillone (Figure 6A; p > 0.05, χ2 = 12.649) nor L. dieuzeidei (Figure 6B; p > 0.05, χ2 = 13.102) showed significant differences in abundance. In both species, the most abundant age class at all three times of day was 5+, with L. cavillone being more abundant in the afternoon, while L. dieuzeidei peaked in abundance in both the morning and afternoon.

Figure 6.

Abundance of age classes of L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei as a function of and depth (A,C) and time of day (B,D).

Regarding depth, L. cavillone (Figure 6C) did not show significant differences in abundance by age class (p > 0.05, χ2 = 6.149), with the 5+ class being the most abundant across both depth ranges; however, greater overall abundance was observed at depths greater than 40 m. In contrast, L. dieuzeidei (Figure 6D) showed significant differences by depth (p < 0.001, χ2 = 32.333). At depths less than 24 m, the predominant age classes were 6+ and 5+, whereas at depths greater than 24 m, specimens aged 4+ and 5+ years dominated, with a higher abundance of younger age classes also recorded at these depths.

3.3. Feeding Habits

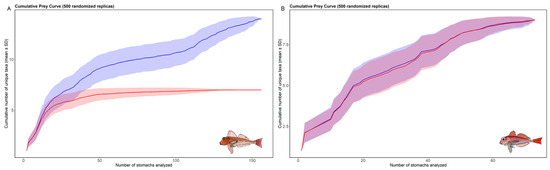

The Cumulative Prey Curves (CPCs) for both species did not reach an asymptote (Figure 7, blue line). A second curve, considering only prey items contributing ≥1% to the Relative Importance Index (%IRI), reached stabilization at 110 specimens for L. cavillone, while for L. dieuzeidei, stabilization was not achieved. Consequently, only a descriptive dietary analysis was performed for L. dieuzeidei.

Figure 7.

Cumulative prey curves for the total number of stomachs analysed for L. cavillone (A) and L. dieuzeidei (B). The blue line represents the cumulative prey curve using all different taxa found in the stomachs, and the red line represents the cumulative prey curve using only those prey with an importance index of at least 1%.

The vacuity index showed that 18% (28 specimens) of L. cavillone stomachs and 28% (21 specimens) of L. dieuzeidei stomachs were empty. Twelve prey items were identified for L. cavillone and nine for L. dieuzeidei (Table 2). Prey were grouped into crustaceans, molluscs, fish, and algae for L. cavillone, and crustaceans, molluscs, and fish for L. dieuzeidei. Crustaceans dominated both diets in terms of relative importance, numerical abundance, and frequency of occurrence. In L. cavillone, mysids were nearly exclusive, contributing ~80% of the IRI, whereas L. dieuzeidei had a more diverse diet, with mysids and decapods contributing 45% and 32% of the IRI, respectively.

Table 2.

Diet composition of large-scale gurnard (Lepidotrigla cavillone) and spiny gurnard (Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei) expressed as frequency of occurrence (%F), numerical percentage (%Cn), gravimetric percentage (%Cw), and Relative Importance Index (IRI).

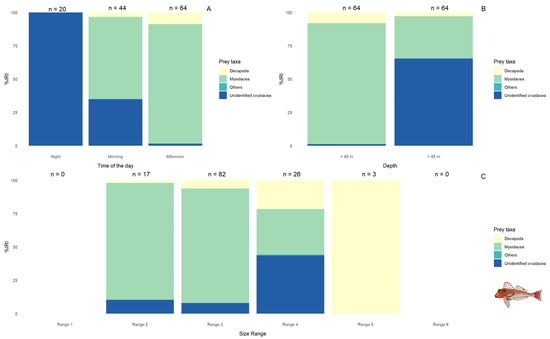

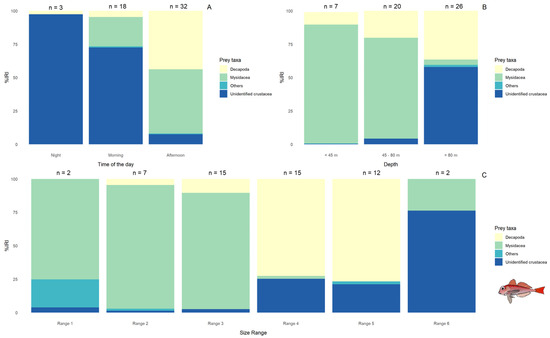

Table 3 shows the specimens of L. cavillone for each variable. PERMANOVA showed that significant differences in prey abundance for L. cavillone occurred across times of day and depth (p < 0.001), with no significant differences with size and the interaction between the variables (p > 0.05). At night, both species mainly consumed unidentified crustaceans (100% IRI for L. cavillone; 97% for L. dieuzeidei). In the morning, L. cavillone fed primarily on mysids (62% IRI) and unidentified crustaceans (34%), while L. dieuzeidei still consumed mainly unidentified crustaceans (72% IRI) with an increase in mysids (22%). In the afternoon, L. cavillone focused almost exclusively on mysids (90% IRI), whereas L. dieuzeidei consumed both mysids (48% IRI) and decapods (43%). The ANOSIM results showed significant differences depending on the time of day for L. cavillone (p < 0.001, R = 0.119).

Table 3.

Number of large-scaled gurnard (L. cavillone) specimens of each variable used for the PERMANOVA and ANOSIM tests. Size ranges 1 and 6 were not taken into account, as they included specimens with empty stomachs.

Diet composition also varied with depth. In L. cavillone, mysids dominated shallow waters (<45 m; 91% IRI), with decapods as a minor component, whereas deeper waters (>45 m) were dominated by unidentified crustaceans (65% IRI) with fewer mysids (33%). Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei showed a similar pattern in shallow waters and mid-waters (<45 m; 89% IRI mysids, and 45–80 m 76% IRI mysids), while deeper waters (>80 m) featured a more balanced diet of unidentified crustaceans (58% IRI) and decapods (37%). Depth-related differences in diet were significant for L. cavillone (p < 0.001, R = 0.179).

The diet composition varied with size in both species (Figure 8C and Figure 9C). In L. cavillone, smaller individuals (5–9 cm) fed mainly on mysids (>85% IRI), whereas larger specimens (9–13 cm) showed an increasing contribution of decapods to the diet. In L. dieuzeidei, mysids also dominated the diet of smaller individuals (3–9 cm), while decapods became more important in larger size classes (9–15 cm). ANOSIM analysis confirmed significant differences in diet composition by size for L. cavillone (p < 0.05; R = 0.0186).

Figure 8.

Comparison between the percentage relative importance of items found in the stomachs of L. cavillone based on time of day (A), depth (B) and size range (C). Groups with a sample size < 5 require cautious interpretation.

Figure 9.

Comparison between the percentage relative importance of items found in the stomachs of L. dieuzeidei based on time of day (A), depth (B) and size range (C). Groups with a sample size < 5 require cautious interpretation.

The Levin index showed a value of 0.208 for L. dieuzeidei and 0.090 for L. cavillone, indicating greater trophic breadth in the former species. The dietary overlap between the two species, calculated using the Schoener index, was 0.575, indicating moderate overlap.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that both L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei display a feeding pattern primarily based on mysids and decapods, consistent with the trophic habits reported for triglids species in other Mediterranean regions [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. The observed ontogenetic shift from mysid to decapod consumption suggests a gradual broadening of the dietary spectrum with growth, particularly in L. dieuzeidei, which also showed a wider niche breadth according to Levin’s index.

The size ranges recorded for the specimens (L. cavillone: 3.9–14.2 cm TL; L. dieuzeidei: 4.0–13.8 cm TL) are consistent with those reported in other studies in the Mediterranean, including the Tyrrhenian Sea (3–12 cm Standard Length (SL), [20]), the Aegean Sea (3.4–15.2 cm TL, [15]), the Cyclades and Dodecanese Islands (4–14 cm TL, [14]), the Sardinian Seas and Sicilian coasts (4.3–14.1 cm TL, [19]), and the Adriatic Sea (7.6–15.3 cm TL, [17]) for L. cavillone, as well as in the Adriatic Sea (7.5–14.6 cm TL, [18]) and the northeastern Mediterranean (7.1–15.9 cm TL, [59]) for L. dieuzeidei. Minor differences among studies may be attributed to seasonal variations, geographical differences between the Mediterranean and Atlantic regions, or differences in the selectivity of the fishing gear used [60].

The LWR results indicate a tendency towards positive allometric growth (b = 3.077 for L. cavillone; b = 3.345 for L. dieuzeidei), in agreement with previous findings for these species in the Gulf of Cádiz [61] and southern Portugal [62], as well as with other triglids species [63]. Understanding these relationships is a crucial tool for population studies, not only for commercially valuable species but also for discarded species, facilitating better stock management [64].

The predominant age for both species was 5+ (46.36% in L. cavillone; 35.62% in L. dieuzeidei), with age 6+ also being common in L. dieuzeidei (34.25%). Significant differences in age-class distribution with depth were only observed in L. dieuzeidei. Species of the genus Lepidotrigla show considerable variation in longevity across regions, likely influenced by ecological factors affecting growth and maximum age. Fishing effort and sampling methods do not directly alter longevity but can bias the age classes captured, leading to non-homogeneous age representations in studies. For instance, relatively low maximum ages for L. cavillone have been reported in some Mediterranean areas, possibly because larger, older individuals—particularly in commercially targeted regions—are retained by fisheries and do not appear in discards [15,18,19,20,59,65]. In this context, the dominance of mid-aged individuals (mainly 5+ and 6+) in discards from the Gulf of Cádiz is consistent with such selectivity effects and with regional differences in population structure.

Environmental factors such as temperature, food availability, competition, and fishing pressure also influence growth and distribution patterns [66]. Consequently, the variations observed in the abundance of age classes throughout the day and across depths may reflect behavioral segregation strategies aimed at reducing interspecific competition for food and space [67,68]. This appears to be the case for L. dieuzeidei, in which the age of individuals increases with depth, possibly as a response to such segregation mechanisms.

In our study, the main prey of L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei were mysids, although for the latter, decapods also played an important role in their diet. This agrees with studies conducted in the Mediterranean for L. cavillone [12,13,14] but differs from the findings of [69] for L. dieuzeidei in the Mediterranean, which reported decapods as the most abundant prey, with mysids being scarcely represented. These variations in diet could be attributed to geographical differences between the Mediterranean, where ref. [69] was conducted, and the Atlantic, where our study took place, or to differences in sample size (360 specimens in [69] vs. 74 in our study). The predominance of mysids and decapods in the diet of both species is consistent with general patterns observed in the Triglidae family, reflecting their benthic predatory behavior [12,70]. It is important to emphasize that the results obtained for L. dieuzeidei are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution, as the number of specimens analyzed was insufficient to fully represent its diet. The dietary composition could vary with a larger sample size. Therefore, future studies with a greater number of specimens will be necessary to confirm these findings. Additionally, although sampling avoided the trawl closed season, this period may correspond to important biological processes such as spawning or shifts in feeding intensity, which were not captured in our study. Consequently, the exclusion of this season could introduce temporal bias affecting both the age structure and feeding data for L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei. Future research should aim to include this period to provide a more comprehensive understanding of these species’ biology.

Significant differences in the diet of L. cavillone were also observed depending on the time of day, both in prey composition and abundance. Both species exhibited similar feeding patterns, with peaks in mysid and decapod consumption in the afternoon and minimal feeding at night. These temporal differences are linked to prey behavior, as small crustaceans such as mysids perform vertical migrations during the night, becoming available again to benthic predators like L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei during the morning and afternoon [71,72,73]. This pattern aligns with [14], who reported that L. cavillone feeds primarily on mysids during daylight hours, shifting to less active benthic prey at night, with L. dieuzeidei potentially exhibiting similar behavior.

Depth also influenced diet composition. Lepidotrigla cavillone showed significant changes with increasing depth, as both species fed mainly on mysids in shallower waters (<45 m for L. cavillone and <45 m and 45–80 m for L. dieuzeidei), whereas at greater depths their diets became more diversified. This pattern likely reflects the higher primary and secondary production in shallow coastal areas, which rapidly decreases with depth [74]. Furthermore, ref. [75], in the Catalan Sea (northwestern Mediterranean), observed that mysid diversity declined with increasing depth. Therefore, the greater abundance of mysids in shallow waters may result from their higher productivity, while individuals inhabiting deeper areas rely on a more varied diet to meet their nutritional requirements.

This pattern is consistent with the environmental characteristics of the Gulf of Cádiz, a highly productive region influenced by the confluence of Atlantic and Mediterranean waters, coastal upwelling, and strong seasonal dynamics [76]. These conditions enhance the abundance of planktonic and benthic crustaceans, including mysids, especially in shallow and coastal zones [77]. Therefore, the strong reliance of both L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei on mysids may reflect the high productivity and prey availability typical of these nearshore habitats.

The diet based on specimen size also showed significant differences in L. cavillone, shifting from a predominance of mysids in smaller and medium-sized individuals to larger crustaceans in larger fish. These results are consistent with observations by [13], who reported ontogenetic dietary changes in L. cavillone on the continental shelf of Crete (Mediterranean Sea), and by [78] for Lepidotrigla mulhalli and L. vanessa in southeastern Australia. Such patterns are likely related to an energy optimisation strategy, whereby fish select prey that provide greater relative benefit in terms of capture effort. Despite these differences, both species feed predominantly on small prey throughout their size range, likely due to the reduced morphology of their mouths [79]. They can thus be classified as scitulus-type predators, characterised by active feeding on small prey through rapid movements or specialised strategies [80]. Similar ontogenetic shifts in predation have been observed in other triglids species, such as Chelidonichthys obscurus and C. lastoviza [69], suggesting that these changes occur not only at the species level but also across the family.

Levin’s index results indicate that both L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei exhibit a specialised diet focused on mysids and decapods. These findings align with those of [13] for L. cavillone, who obtained a Levin index of 0.25, comparable to our value of 0.208, and with [12], who also describe the species as a selective predator. This specialisation is likely facilitated by the high abundance and accessibility of prey, such as mysids, whose gregarious behavior makes them particularly available to opportunistic species [81,82]. Other triglids species, such as C. lastoviza, exhibit similar levels of dietary specialisation, as indicated by Levin’s index [13].

Schoener’s overlap index yielded a value of 0.575, indicating moderate dietary overlap between the two species. Although no studies have specifically addressed diet overlap between L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei, [14] reported similar low-to-moderate trophic overlap among other triglid species. Values above 0.6 are generally considered indicative of significant overlap [83,84]. Variation in this index may reflect changes in the availability of key prey, such as decapods and mysids, which depends not only on abundance but also on prey size, mobility, and predation success [85,86]. In environments where resources are relatively abundant, such as many continental shelf areas, low interspecific competition may favour specialised feeding patterns, while resource availability and niche differentiation reduce direct competition, facilitating coexistence of cohabiting species. These findings highlight how both spatial distribution and body size-related dietary preferences may contribute to niche segregation between the two species.

This situation likely occurs in the Gulf of Cádiz, where high productivity [76] supports the presence of species with similar feeding habits, including not only L. cavillone and L. dieuzeidei but also several elasmobranch species [87]. Although competition is unlikely under such resource-rich conditions, environmental changes, such as increasing ocean temperatures due to climate change, could modify prey availability and species composition within the same trophic niche, potentially leading to stronger interspecific competition [88,89].

Studies on the biology of discarded species, for instance, their age and feeding habits, are essential due to their importance in ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM). Such research provides valuable information on population dynamics and ecological traits, which are fundamental for sustainable fisheries management and for understanding marine food-web functioning [90]. Moreover, although further studies are needed, there may be dietary overlaps with other commercial species, such as juvenile hake (Merluccius merluccius) [91], or with other organisms sharing similar feeding habits. Therefore, research aimed at refining this knowledge and identifying potential interactions among these species within the ecosystem is of great importance. Studies like the present one, focused on non-commercial and relatively understudied species, are crucial to improving our understanding of their ecological role and relationship with fisheries.

5. Conclusions

Lepidotrigla cavillone and L. dieuzeidei in the Gulf of Cádiz primarily feed on crustaceans, especially mysids and decapods. Their diet varies with depth, with mysids dominating in shallower waters and larger decapods in deeper areas, likely influenced by prey availability and vertical migration. Both species show a clear diurnal feeding pattern, peaking during daylight hours. Larger individuals consume larger prey, reflecting an energy-optimization strategy. These results provide valuable insights into the feeding ecology of the species and their role within the benthic ecosystem. However, in the case of L. dieuzeidei, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of specimens collected and their low representativeness. Further studies based on a larger sample size would be necessary to confirm these observations. Similarly, since commercial trawling in the Gulf of Cádiz is temporarily banned for a month and a half (15 September–31 October), potential biases may arise from the temporal and spatial origin of samples obtained from this commercial fleet. Future studies based on oceanographic surveys would help to strengthen the conclusions drawn from this work.

Author Contributions

C.R.-G.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and data curation. Ó.L.-P.: investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and data curation. J.S.-C.: data curation, writing—review and editing. R.C.-C.: investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, data curation, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out within the framework of the ECOFISH projects: ecoinnovative strategies for sustainable fishing in the Gulf of Cadiz SPA. This initiative was supported by the Biodiversity Foundation, the Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge, through the Pleamar Program, co-financed by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) [grant number: 2021/PV/PLEAMAR20-21/PT; 2021-060/PV/PLEAMAR21/PT].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The specimens used in this work have never been subjected to animal experimentation. These specimens come from catches made by professional fishermen and are subject to European regulations on fish discards.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The publication of this work was made possible thanks to the ECOFISH+, and ECOFISH 4.0. projects in collaboration with the Biodiversity Foundation of the Ministry of Ecological Transition, through the Pleamar Program, co-financed by the EMFF. The authors would like to thank the observers (Andrea, Tania, and Zaida) for going on the fishing vessels and for collecting the specimens sampled and the professional fleet of Puerto de Santa María and the Cofradía de Pescadores de Sanlúcar de Barrameda. We would also like to express our gratitude to INMAR (Instituto Universitario de Investigación Marina) for allowing us to use their laboratories to carry out all of the precision measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mineva, T.D. Efectos Negativos del Sector Pesquero en el Medio Marino. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. FAO. 2024. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd0683en (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, S.; Rajan, R. By-catch and Discard Management towards Sustainable Fisheries. In Revolutionizing Fisheries Management and Conservation: The Role of AI and GPS; Sahu, A., Ranjan, D., Satkar, S., Iqbal, G., Kumar, N., Eds.; International Books & Periodical Supply Service: New Delhi, India, 2025; p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- Sherley, R.B.; Ladd-Jones, H.; Garthe, S.; Stevenson, O.; Votier, S.C. Scavenger communities and fisheries waste: North Sea discards support 3 million seabirds, 2 million fewer than in 1990. Fish Fish. 2020, 21, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, A.; Rodríguez-García, C.; Cabrera-Castro, R.; Arroyo, G.M. Correlation between seabirds and fisheries varies by species at fine-scale pattern. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 80, 2427–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hureau, J.-C. Triglidae. In Fishes of the North-Eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean Vol. 3; Whitehead, P.J.P., Bauchot, M.-L., Hureau, J.-C., Nielsen, J., Tortonese, E., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1986; pp. 1230–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Bauchot, M.L. Poissons osseux. In Fiches FAO D’identification pour les Besoins de la Pêche. (rev. 1). Méditerranée et mer Noire. Zone de pêche 37. Vol. II; Fischer, W., Bauchot, M.L., Schneider, M., Eds.; Commission des Communautés Européennes and FAO: Rome, Italy, 1987; pp. 891–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. FishBase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. Available online: https://www.fishbase.org (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- FAO. FishStat. Global Capture Production QUANTITY (1950–2023). Available online: https://fao.org/fishery/statisticsquery/en/capture/capture_quantity (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Marano, C.A.; Marsan, R.; Marzano, M.C.; Ungaro, N. Note sull’accrescimento di Lepidotrigla cavillone (Lacepède, 1802)–Osteichthyes, Triglidae-nelle acque del basso Adriatico. Biol. Mar. Mediterr. 1999, 6, 584–586. [Google Scholar]

- Caragitsou, E.; Papaconstantinou, C. Food and feeding habits of large scale gurnard, Lepidotrigla cavillone (Triglidae) in Greek Seas. Cybium 1990, 14, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Labropoulou, M.; Machias, A. Effect of habitat selection on the dietary patterns of two triglid species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1998, 173, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Terrats, A.; Petrakis, G.; Papaconstantinou, C. Feeding habits of Aspitrigla cuculus (L., 1758) (red gurnard), Lepidotrigla cavillone (Lac., 1802) (large scale gurnard) and Trigloporus lastoviza (Brunn., 1768) (rock gurnard) around Cyclades and Dodecanese Islands (E. Mediterranean). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2000, 1, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlkyaz, A.T.; Metin, G.; Soykan, O.; Kinacigil, H.T. Growth and reproduction of large-scaled gurnard (Lepidotrigla cavillone Lacepède, 1801) (Triglidae) in the central Aegean Sea, eastern Mediterranean. Turk. J. Zool. 2010, 34, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başusta, A.; Özer, E.İ.; Girgin, H. Akdeniz deki Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei (Blanc & Hureau, 1973) Populasyonunda Otolit Biyometrisi-Balık Uzunluğu Arasındaki İlişki. Aquac. Stud. 2013, 3, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobroslavić, T.; Sulić Šprem, J.; Prusina, I.; Kožul, V.; Glamuzina, B.; Bartulović, V. Reproduction biology of large--scaled gurnard Lepidotrigla cavillone (L acepède, 1801) from the southern Adriatic Sea (Croatia). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2015, 31, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobroslavić, T.; Conides, A.; Šprem, J.S.; Glamuzina, B.; Bartulović, V. Reproductive strategy of spiny gurnard Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei Blanc and Hureau, 1973 from the south-eastern Adriatic Sea. Acta Adriat. 2021, 62, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellodi, A.; Asciutto, E.; Malara, D.; Longo, F.; Agus, B.; Bacchiani, C.; Follesa, M.C.; Porcu, C.; Mangano, M.C.; Battaglia, P. Age determination, growth and otolith shape analysis of Lepidotrigla cavillone from Sardinian and Sicilian waters (Mediterranean Sea). J. Fish Biol. 2025, 107, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colloca, F.; Cardinale, M.; Ardizzone, G.D. Biology, spatial distribution and population dynamics of Lepidotrigla cavillone (Pisces: Triglidae) in the Central Tyrrhenian Sea. Fish. Res. 1997, 32, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, E.; Rueda, J.L.; Bruque, G.; López-González, N.; Fernández-Salas, L.M.; Farias, C.; Díaz del Río, V. Evaluación espacial de la actividad pesquera de arrastre en un campo somero de volcanes de fango del Golfo de Cádiz/Spatial assessment of trawling activity in a shallow mud volcano field of the Gulf of Cádiz. In Proceedings of the VIII Simposio MIA15, Málaga, Spain, 21–23 September 2015; Available online: https://files.core.ac.uk/download/71779831.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Llope, M.; de Carvalho-Souza, G.F.; Baldó, F.; González-Cabrera, C.; Jiménez, M.P.; Licandro, P.; Vilas, C. Gulf of Cadiz zooplankton: Community structure, zonation and temporal variation. Prog. Oceanogr. 2020, 186, 102379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Martínez, M.J.; Miró, J.M.; Vicente, L.; Megina, C.; Donázar-Aramendía, I.; García-Gómez, J.C.; González-Gordillo, J.I. Mesozooplankton assemblage in the gulf of cádiz estuaries: Taxonomic and trait-based approaches. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 198, 106554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llope, M. The ecosystem approach in the Gulf of Cadiz. A perspective from the southernmost European Atlantic regional sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaucao, A.; González-Ortegón, E.; Jiménez, M.P.; Teles-Machado, A.; Plecha, S.; Peliz, A.J.; Laiz, I. Assessment of the spawning habitat, spatial distribution, and Lagrangian dispersion of the European anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) early stages in the Gulf of Cadiz during an apparent anomalous episode in 2016. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 781, 146530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, J.M.; Megina, C.; Donázar-Aramendía, I.; Reyes-Martínez, M.J.; Sánchez-Moyano, J.E.; García-Gómez, J.C. Environmental factors affecting the nursery function for fish in the main estuaries of the Gulf of Cadiz (south-west Iberian Peninsula). Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 737, 139614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulland, J.A.; García, S. Observed patterns in multispecies fisheries. In Explotation of Marine Communities; May, R.M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; pp. 155–190. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2019/1241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on the Conservation of Fisheries Resources and the Protection of Marine Ecosystems Through Technical Measures, Amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1967/2006, (EC) No 1224/2009 and Regulations (EU) No 1380/2013, (EU) 2016/1139, (EU) 2018/973, (EU) 2019/472 and (EU) 2019/1022 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 894/97, (EC) No 850/98, (EC) No 2549/2000, (EC) No 254/2002, (EC) No 812/2004 and (EC) No 2187/2005). Official Journal of the European Union, L 198, 25 July 2019, pp. 105–201. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1241/oj/eng (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Lloris, D. Ictiofauna Marina: Manual de Identificación de los Peces Marinos de la Península Ibérica y Balears; Omega: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, M.E.; Kerstan, M. Age validation in horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) otoliths. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2001, 58, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, P.J.; Ryland, J.S. Handbook of the Marine Fauna of North-West Europe; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ricker, W.E. Computation and Interpretation of Biological Statistics of Fish Populations; Bulletin of Fisheries Research Agency. Board Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1975; p. 382. [Google Scholar]

- Froese, R. Cube law, condition factor and weight–length relationships: History, meta-analysis and recommendations. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006, 22, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyslop, E.J. Stomach contents analysis—A review of methods and their application. J. Fish Biol. 1980, 17, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.N.; Ezzi, I.A. Feeding relationships of a demersal fish assemblage on the west coast of Scotland. J. Fish Biol. 1987, 31, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J. Ecological Methodology; Longman: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stergiou, K.I. Feeding habits of the Lessepsian migrant Siganus luridus in the eastern Mediterranean, its new environment. J. Fish Biol. 1988, 33, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, R.W. Diet overlap between the Atlantic cod Gadus morhua, silver hake Merluccius bilinearis and fifteen other northwest Atlantic finfish. Fish. Bull. 1982, 80, 745–759. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry, L.A.; Caillet, G.M. Sample size and data analysis: Are we characterizing and comparing diet properly? In Feeding Ecology and Nutrition in Fish, Symposium Proceedings; MacKinlay, D., Shearer, K., Eds.; American Fisheries Society: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Matić-Skoko, S.; Tutman, P.; Bojanić Varezić, D.; Skaramuca, D.; Đikić, D.; Lisičić, D.; Skaramuca, B. Food preferences of the Mediterranean moray eel, Muraena helena (Pisces: Muraenidae), in the southern Adriatic Sea. Mar. Biol. Res. 2014, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Gutiérrez, J.; García-González, A.; Rodríguez-García, C.; Domínguez-Bustos, Á.R.; Cabrera-Castro, R. Age, growth, and feeding of boarfish, Capros aper (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Southwest of the Iberian Peninsula. Mar. Biol. Res. 2023, 19, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. Permutation tests for univariate or multivariate analysis of variance and regression. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2001, 58, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; ter Braak, C.J.F. Permutation tests for multifactorial analysis of variance. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2003, 73, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warton, D.I.; Wright, T.W.; Wang, Y. Distance-based multivariate analyses confound location and dispersion effects. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation; R package version 1.1. 2. 2023. Available online: https://dplyr.tidyverse.org (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grolemund, G.; Wickham, H. Dates and times made easy with lubridate. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 40, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.6-4. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Wickham, H. Reshaping Data with the reshape Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Forcats: Tools for Working with Categorical Variables (Factors). 2023. Available online: https://forcats.tidyverse.org/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Wickham, H. Modelr: Modelling Functions that Work with the Pipe. R Package Version 0.1.11. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=modelr (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Auguie, B. GridExtra: Miscellaneous Functions for “Grid” Graphics. R Package Version 2.3. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gridExtra (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Hester, J.; Chang, W.; Bryan, J. Devtools: Tools to Make Developing R Packages Easier. R Package Version 2.4.5. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=devtools (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Başusta, A.; Başusta, N.; Calta, M.; Ozcan, E.I. A study on age and growth characteristics of spiny gurnard (Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei Blanc & Hureau, 1973), northeastern Mediterranean Sea. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2017, 33, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, N.; Ferro, R.S.T.; Karp, W.A.; MacMullen, P. Fishing practice, gear design, and the ecosystem approach—Three case studies demonstrating the effect of management strategy on gear selectivity and discards. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2007, 64, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.A.; Ramos, F.; Sobrino, I. Length–weight relationships of 76 fish species from the Gulf of Cadiz (SW Spain). Fish. Res. 2012, 127, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olim, S.; Borges, T.C. Weight–length relationships for eight species of the family Triglidae discarded on the south coast of Portugal. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006, 22, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallisneri, M.; Montanini, S.; Stagioni, M. Size at maturity of triglid fishes in the Adriatic Sea, northeastern Mediterranean. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2012, 28, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, C.; Castro-Gutiérrez, J.; Domínguez-Bustos, Á.R.; García-González, A.; Cabrera-Castro, R. Every fish counts: Challenging length–weight relationship bias in discards. Fishes 2023, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toğulga, M.; Uçkun, D.; Akalın, S. Study on the biology of the large-scaled gurnard (Lepidotrigla cavillone Lacepede, 1801) in the Gülbahçe Bay (Aegean Sea). Ege Univ. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2000, 17, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherley, A.H.; Gill, H.S. Growth increases produced by bovine growth hormone in grass pickerel, Esox americanus vermiculatus (Le Sueur), and the underlying dynamics of muscle fiber growth. Aquaculture 1987, 65, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Trait response in communities to environmental change: Effect of interspecific competition and trait covariance structure. Theor. Ecol. 2010, 5, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutrage, L.; Anik, B.; Chouvelon, T.; Spitz, J. High trophic specialization structures the epi-to bathypelagic fish community in the Bay of Biscay. Deep. Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2024, 209, 104347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobroslavić, T. Biološko-Ekološke Karakteristike Kokotića Lepidotrigla dieuzeidei Blanc & Hureau, 1973 i Kokotića Oštruljića Lepidotrigla cavillone (Lacepede, 1801) na Području Južnog Jadrana. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Split, Split, Kroatien, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boudaya, L.; Neifar, L.; Taktak, A.; Ghorbel, M.; Bouain, A. Diet of Chelidonichthys obscurus and Chelidonichthys lastoviza (Pisces: Triglidae) from the Gulf of Gabes (Tunisia). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2007, 23, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, Y. Vertical migration of zooplankton: A game between predator and prey. Am. Nat. 1982, 120, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberá, C. Misidáceos (Peracarida: Crustacea) Asociados a Fanerógamas Marinas en el SE Ibérico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat d’Alacant/Universidad de Alicante, San Vicente del Raspeig, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bandara, K.; Varpe, Ø.; Wijewardene, L.; Tverberg, V.; Eiane, K. Two hundred years of zooplankton vertical migration research. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 1547–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddy, J.F.; Sharp, G.D. An ecological Framework for Marine Fishery Investigations; Food & Agriculture Org.: Rome, Italy, 1986; 152p. [Google Scholar]

- Cartes, J.E.; Sorbe, J.C. Deep-water mysids of the Catalan Sea: Species composition, bathymetric and near-bottom distribution. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 1995, 75, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Lafuente, J.; Ruiz, J. The Gulf of Cádiz pelagic ecosystem: A review. Prog. Oceanogr. 2007, 74, 228–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Martínez, M.J.; Ruiz-Delgado, M.C.; Sánchez-Moyano, J.E.; García-García, F.J. Biodiversity and distribution of macroinfauna assemblages on sandy beaches along the Gulf of Cadiz (SW Spain). Sci. Mar. 2015, 79, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Park, J.M.; Gaston, T.F.; Williamson, J.E. Resource partitioning in gurnard species using trophic analyses: The importance of temporal resolution. Fish. Res. 2017, 186, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labropoulou, M.; Tserpes, G.; Tsimenides, N. Age, Growth and Feeding Habits of the Brown Comber Serranus hepatus (Linnaeus, 1758) on the Cretan Shelf. Estuarine, Coast. Shelf Sci. 1998, 46, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.T. Patterns of resource partitioning in searobins (Pisces: Triglidae). Copeia 1977, 1977, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froneman, P.W. Feeding ecology of the mysid, Mesopodopsis wooldridgei, in a temperate estuary along the eastern seaboard of South Africa. J. Plankton Res. 2001, 23, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, A.M.; Jones, M.B. Correlation of the distribution of Mesopodopsis slabberi (Crustacae, Mysidacea) with physico-chemical gradients in a partially-mixed estuary (Tamar, England). Aquat. Ecol. 1993, 27, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keast, A. Trophic and spatial interrelationships in the fish species of an Ontario temperate lake. Environ. Biol. Fishes 1978, 3, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.K. An assessment of diet-overlap indexes. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1981, 110, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.M.; Harrison, H.M., Jr. Food habits of the southern channel catfish (Ictalurus lacustris punctatus) in the Des Moines River, Iowa. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1948, 75, 110–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D. Prey availability and the food of predators. Ecology 1975, 56, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, C.; Gonçalves Neto, J.B.; García-Romero, C.; Domínguez-Bustos, Á.R.; Cabrera-Castro, R. Feeding habits of two shark species: Velvet belly, Etmopterus spinax (Linnaeus, 1758) and blackmouth catshark, Galeus melastomus (Rafinesque, 1810), present in fishing discards in the Gulf of Cádiz. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2024, 107, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachiller, E.; Giménez, J.; Albo-Puigserver, M.; Pennino, M.G.; Marí-Mena, N.; Esteban, A.; Lloret-Lloret, E.; Bellido, J.M.; Coll, M. Trophic niche overlap between round sardinella (Sardinella aurita) and sympatric pelagic fish species in theWestern Mediterranean. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 16126–16142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennino, M.G.; Coll, M.; Albo-Puigserver, M.; Fernández-Corredor, E.; Steenbeek, J.; Giráldez, A.; González, M.; Esteban, A.; Bellido, J.M. Current and future influence of environmental factors on small pelagic fish distributions in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, Ö. Length-weight relationships of eight discarded flatfish species from Gallipoli Peninsula (Northern Aegean Sea, Türkiye): An evaluation for ecosystem-based fisheries management. Palawan Sci. 2022, 14, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, P.; Colloca, F.; Cardinale, M.; Belluscio, A.; Ardizzone, G.D. Feeding habits of European hake (Merluccius merluccius) in the central Mediterranean Sea. Fish. Bull. 2005, 103, 411–416. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).