Purse Seine Capture of Small Pelagic Species: A Critical Review of Welfare Hazards and Mitigation Strategies Through the fair-fish Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Neglect of Animal Welfare in Capture Fisheries: An Urgent and Overlooked Ethical Frontier

1.2. Four Small Pelagic Species and the Prevalence of Purse Seining to Catch Them

1.3. The fair-fish Database: An Open-Access Scientific Platform for Aquatic Animal Welfare

1.4. The Method Profile: A Novel Approach to Fisheries Welfare Assessment

1.5. Objectives

- Describes the operational phases of the purse seine fishing method and identifies welfare hazards at each stage for these small pelagic species;

- Discusses bycatch and discarding issues in addition to environmental impacts, such as ghost fishing, which are related to purse seine fishing of these small pelagic species;

- Explores practical and theoretical strategies to mitigate welfare hazards, including operational improvements, gear modifications, and management measures;

- Proposes research priorities, integrative approaches, policy and management frameworks, and compliance mechanisms to address the welfare of these small pelagic species during purse seining.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Methods

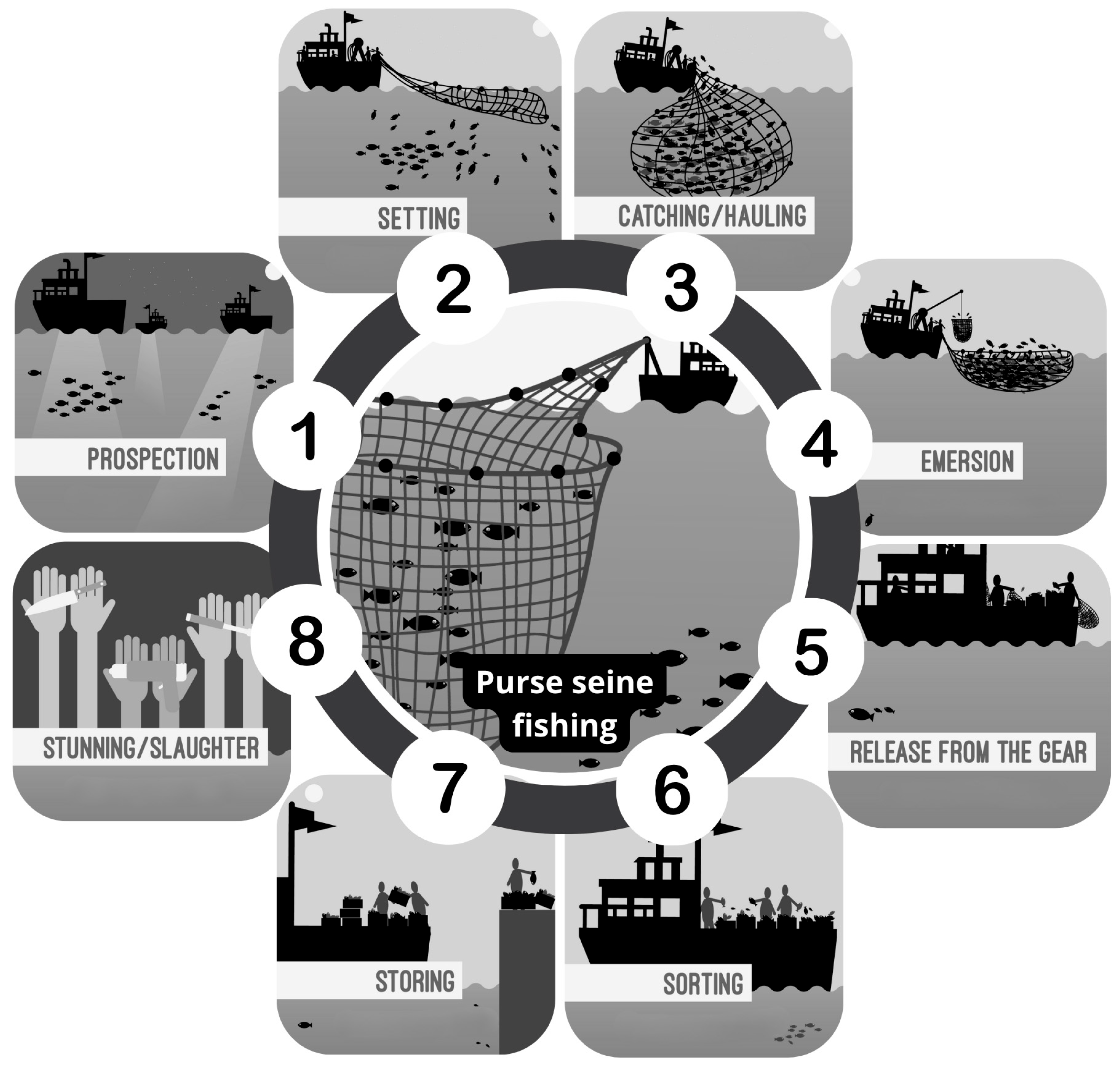

2.2. Welfare Hazards During Purse Seine Fishing Operations

2.2.1. Prospection and Setting

2.2.2. Hauling and Crowding

2.2.3. Scooping or Pumping on Board

2.2.4. Handling and Sorting Procedures

2.2.5. Storage

2.2.6. Stunning and Slaughter

2.3. Mitigation Strategies to Improve Welfare During Purse Seine Fishing Operations

2.3.1. Prospection and Setting

2.3.2. Hauling and Crowding

2.3.3. Scooping or Pumping on Board

2.3.4. Handling and Sorting Procedures

2.3.5. Storage

2.3.6. Stunning and Slaughter

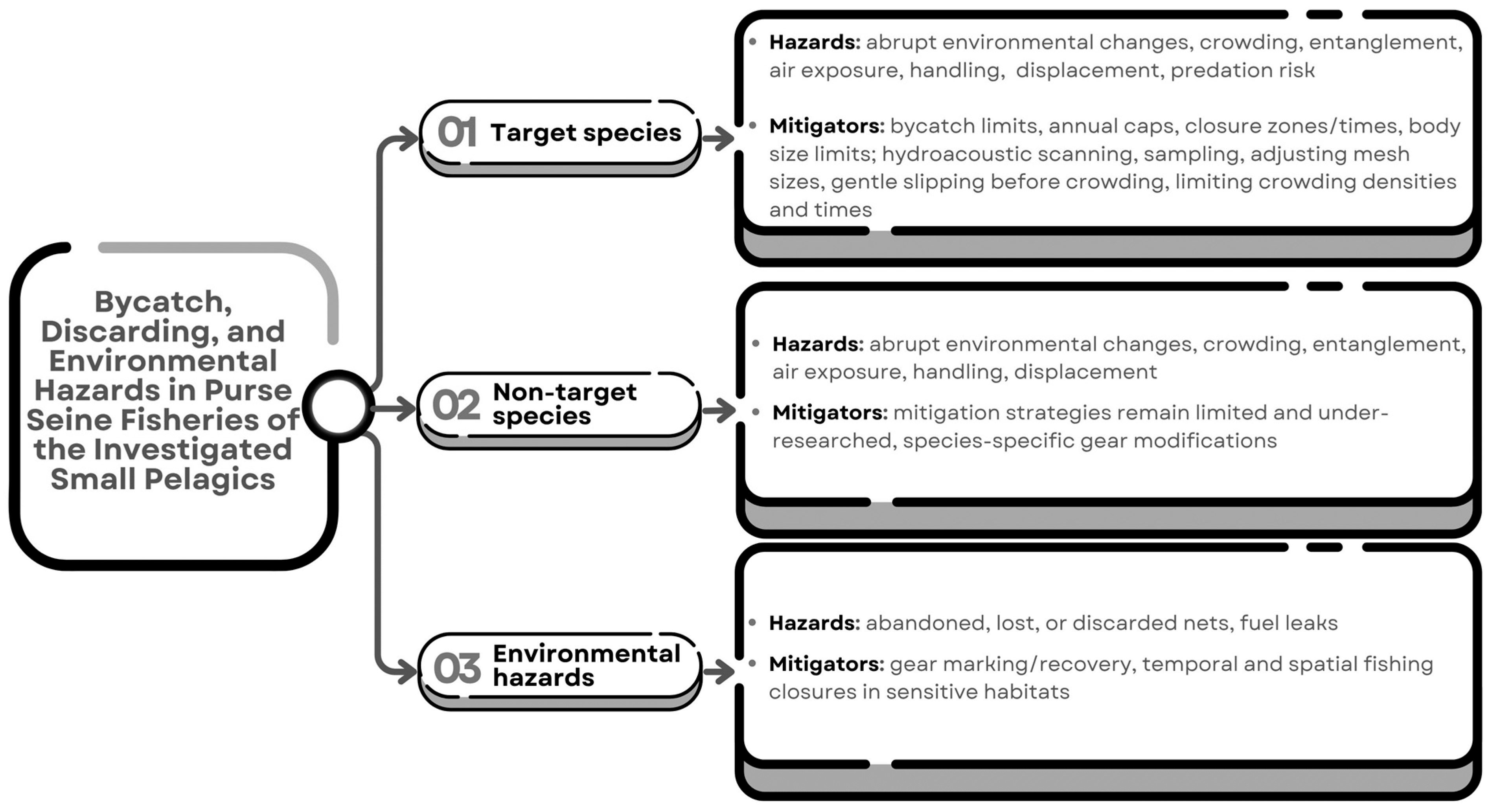

2.4. Bycatch, Discarding, and Environmental Hazards

2.4.1. Bycatch and Discards

2.4.2. Ghost Fishing and Other Environmental Impacts

2.5. Current Mitigation Efforts for Bycatch, Discard, and Environmental Hazards

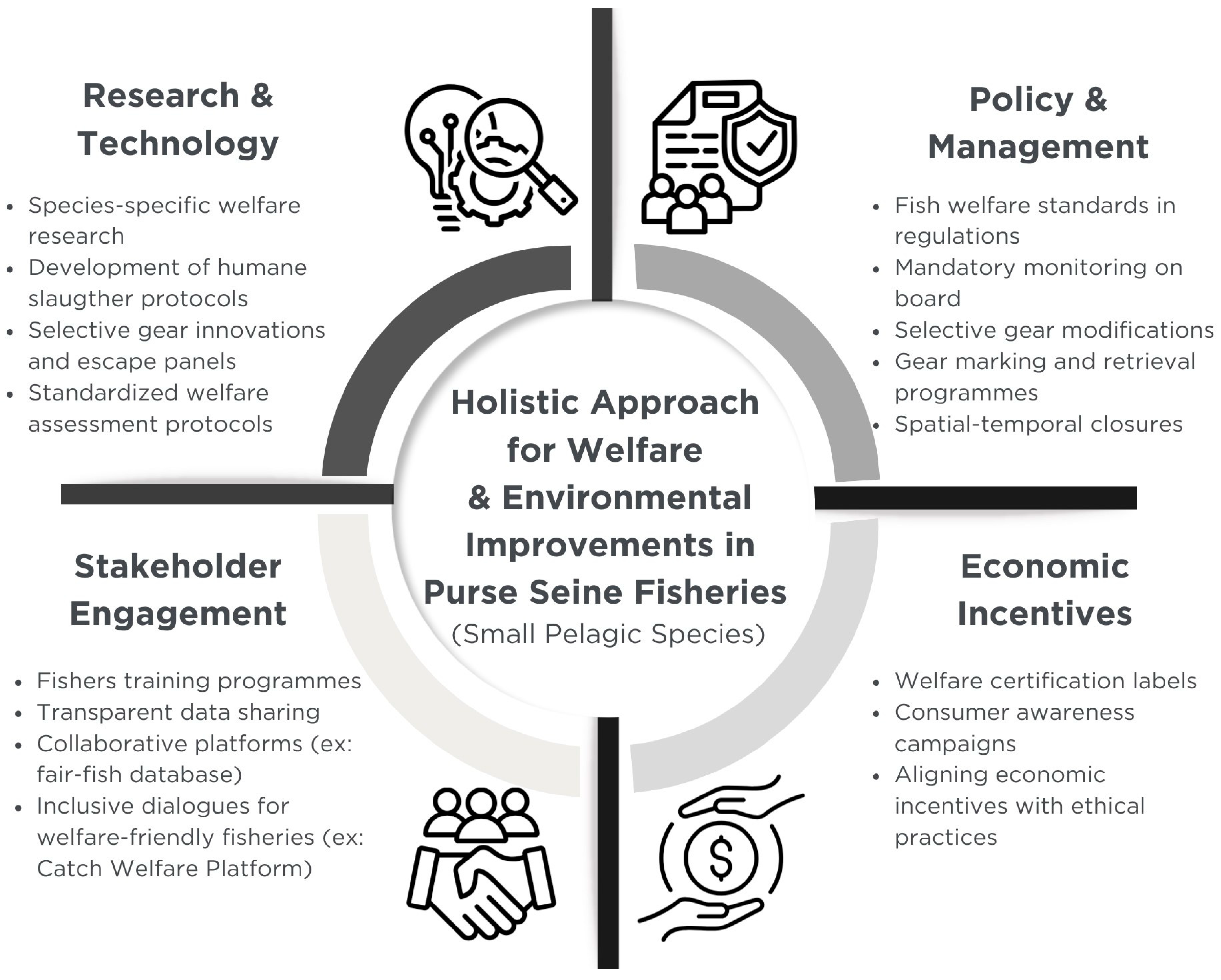

3. Recommendations for Welfare and Environmental Improvements

3.1. Policy and Management Frameworks, Economic Incentives

3.2. Research Priorities and Technological Innovations

3.3. Stakeholder Engagement and Compliance Mechanisms

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braithwaite, V.; Boulcott, P. Pain Perception, Aversion and Fear in Fish. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2007, 75, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. Fish Intelligence, Sentience and Ethics. Anim. Cogn. 2015, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, L.U. Do Painful Sensations and Fear Exist in Fish. In Animal Suffering, from Science to Law: International Symposium/Under the Direction of Thierry Auffret van der Kemp and Martine Lachance; Auffret van der Kemp, T., Lachance, M., Eds.; Carswell: Toronto, Ontario, 2013; pp. 93–112. ISBN 978-2-89635-919-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon, L.U. Evolution of Nociception and Pain: Evidence from Fish Models. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20190290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneddon, L.U.; Braithwaite, V.A.; Gentle, M.J. Do Fishes Have Nociceptors? Evidence for the Evolution of a Vertebrate Sensory System. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Moccia, R.D.; Duncan, I.J.H. Investigating Fear in Domestic Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, Using an Avoidance Learning Task. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 87, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucon-Xiccato, T.; Loosli, F.; Conti, F.; Foulkes, N.S.; Bertolucci, C. Comparison of Anxiety-like and Social Behaviour in Medaka and Zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximino, C.; Marques De Brito, T.; Dias, C.A.G.D.M.; Gouveia, A.; Morato, S. Scototaxis as Anxiety-like Behavior in Fish. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazeaud, M.M.; Mazeaud, F.; Donaldson, E.M. Primary and Secondary Effects of Stress in Fish: Some New Data with a General Review. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1977, 106, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaras, A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Basal and Post-Stress Circulating Cortisol Concentration in an Important Marine Aquaculture Fish Species, European Sea Bass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Animals 2023, 13, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendelaar Bonga, S.E. The Stress Response in Fish. Physiol. Rev. 1997, 77, 591–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinrinade, I.; Kareklas, K.; Teles, M.C.; Reis, T.K.; Gliksberg, M.; Petri, G.; Levkowitz, G.; Oliveira, R.F. Evolutionarily Conserved Role of Oxytocin in Social Fear Contagion in Zebrafish. Science 2023, 379, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Zeller, D. Catch Reconstructions Reveal That Global Marine Fisheries Catches Are Higher than Reported and Declining. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashion, T.; Al-Abdulrazzak, D.; Belhabib, D.; Derrick, B.; Divovich, E.; Moutopoulos, D.K.; Noël, S.-L.; Palomares, M.L.D.; Teh, L.C.L.; Zeller, D.; et al. Reconstructing Global Marine Fishing Gear Use: Catches and Landed Values by Gear Type and Sector. Fish. Res. 2018, 206, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mood, A.; Brooke, P. Estimating Global Numbers of Fishes Caught from the Wild Annually from 2000 to 2019. Anim. Welf. 2024, 33, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, N.; Hannaas, S.; Saltskår, J.; Schuster, E.; Tenningen, M.; Totland, B.; Vold, A.; Øvredal, J.T.; Breen, M. Vitality as a Measure of Animal Welfare during Purse Seine Pumping Related Crowding of Atlantic Mackerel (Scomber scrombrus). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, B.; Skåra, T. Pre Mortem Capturing Stress of Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus) in Purse Seine and Subsequent Effect on Welfare and Flesh Quality. Fish. Res. 2021, 244, 106124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Cordova, J.F.; Roque, A.; Ruiz-Gómez, M.D.L.; Rey-Planellas, S.; Boglino, A.; Rodríguez-Montes De Oca, G.A.; Ibarra-Zatarain, Z. Farmed Fish Welfare Research Status in Latin America: A Review. J. Fish Biol. 2025, 106, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, J.L.; Arechavala-Lopez, P. Welfare of Fish—No Longer the Elephant in the Room. Fishes 2019, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.; Anders, N.; Humborstad, O.-B.; Nilsson, J.; Tenningen, M.; Vold, A. Catch Welfare in Commercial Fisheries. In The Welfare of Fish; Kristiansen, T.S., Fernö, A., Pavlidis, M.A., van de Vis, H., Eds.; Animal Welfare; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 401–437. ISBN 978-3-030-41675-1. [Google Scholar]

- Waley, D.; Harris, M.; Goulding, I.; Correira, M.; Carpenter, G. Catching Up: Fish Welfare in Wild Capture Fisheries; Catching Up; Eurogroup for Animals: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Álvarez, M.J. Clupea harengus (WelfareCheck|catch: Purse Seines); In fair-fish Database; fair-fish, Ed.; World Wide Web Electronic Publication. Version A | 0.2 (Pre-Release). 2024. Available online: https://fair-fish-database.net (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Maia, C.M. Scomber colias (WelfareCheck|catch: Purse Seines); In fair-fish Database; fair-fish, Ed.; World Wide Web Electronic Publication. Version A | 0.2 (Pre-Release). 2024. Available online: https://fair-fish-database.net (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Volstorf, J. Engraulis ringens (WelfareCheck|catch: Purse Seines); In fair-fish Database; fair-fish, Ed.; World Wide Web Electronic Publication. Version A | 0.2 (Pre-Release). 2024. Available online: https://fair-fish-database.net (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Volstorf, J.; Maia, C.M. Scomber scombrus (WelfareCheck|catch: Purse Seines); In fair-fish Database; fair-fish, Ed.; World Wide Web Electronic Publication. Version A | 0.1 (Pre-Release). 2025. Available online: https://fair-fish-database.net (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Anders, N.; Roth, B.; Breen, M. Physiological Response and Survival of Atlantic Mackerel Exposed to Simulated Purse Seine Crowding and Release. Conserv. Physiol. 2021, 9, coab076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K.L.; Aparicio, S.P.; Jayasuriya, N.S.; Herath, T.K.; Lines, J.; Sneddon, L.U.; Amarasinghe, U.S.; Randall, N.P. Humane Stunning or Stun/Killing in the Slaughter of Wild-Caught Finfish: The Scientific Evidence Base. Anim. Welf. 2025, 34, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, J.D. Welfare in Wild-Capture Marine Fisheries. J. Fish Biol. 2009, 75, 2855–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuizen, L.J.L.; Berentsen, P.B.M.; De Boer, I.J.M.; Van De Vis, J.W.; Bokkers, E.A.M. Fish Welfare in Capture Fisheries: A Review of Injuries and Mortality. Fish. Res. 2018, 204, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Chopin, F.; Suuronen, P.; Ferro, R.S.T.; Lansley, J. Classification and Illustrated Definition of Fishing Gears; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Papers; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134514-6. [Google Scholar]

- Marçalo, A.; Breen, M.; Tenningen, M.; Onandia, I.; Arregi, L.; Gonçalves, J.M.S. Mitigating Slipping-Related Mortality from Purse Seine Fisheries for Small Pelagic Fish: Case Studies from European Atlantic Waters. In The European Landing Obligation: Reducing Discards in Complex, Multi-Species and Multi-Jurisdictional Fisheries; Uhlmann, S.S., Ulrich, C., Kennelly, S.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 297–318. ISBN 978-3-030-03308-8. [Google Scholar]

- Misund, O.A. Avoidance Behaviour of Herring (Clupea harengus) and Mackerel (Scomber scombrus) in Purse Seine Capture Situations. Fish. Res. 1993, 16, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Watson, R., IV. 10 Spatial Dynamics of Marine Fisheries. In The Princeton Guide to Ecology; Levin, S.A., Carpenter, S.R., Godfray, H.C.J., Kinzig, A.P., Loreau, M., Losos, J.B., Walker, B., Wilcove, D.S., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 501–510. ISBN 978-1-4008-3302-3. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, J.; Tyedmers, P. Fuel Use and Greenhouse Gas Emission Implications of Fisheries Management: The Case of the New England Atlantic Herring Fishery. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.E.; Oppedal, F.; Tenningen, M.; Vold, A. Physiological Response and Mortality Caused by Scale Loss in Atlantic Herring. Fish. Res. 2012, 129–130, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenningen, M.; Vold, A.; Olsen, R.E. The Response of Herring to High Crowding Densities in Purse-Seines: Survival and Stress Reaction. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2012, 69, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenningen, M.; Pobitzer, A.; Handegard, N.O.; de Jong, K. Estimating Purse Seine Volume during Capture: Implications for Fish Densities and Survival of Released Unwanted Catches. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 76, 2481–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digre, H.; Tveit, G.M.; Solvang-Garten, T.; Eilertsen, A.; Aursand, I.G. Pumping of Mackerel (Scomber scombrus) Onboard Purse Seiners, the Effect on Mortality, Catch Damage and Fillet Quality. Fish. Res. 2016, 176, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, N.; Roth, B.; Grimsbø, E.; Breen, M. Assessing the Effectiveness of an Electrical Stunning and Chilling Protocol for the Slaughter of Atlantic Mackerel (Scomber scombrus). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgreen, A.H.; Slinde, E.; Møller, D.; Roth, B. Effect of Various Electric Field Strengths and Current Durations on Stunning and Spinal Injuries of Atlantic Herring. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 2008, 20, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mood, A. Worse Things Happen at Sea: The Welfare of Wild-Caught Fish; Fishcount.org.uk. 2010. Available online: https://www.fishcount.org.uk/published/standard/fishcountfullrptSR.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Maia, C.M.; Saraiva, J.L.; Volstorf, J.; Gonçalves-de-Freitas, E. Surveying the Welfare of Farmed Fish Species on a Global Scale through the fair-fish Database. J. Fish Biol. 2024, 105, 960–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, C.M.; Cabrera-Álvarez, M.J.; Volstorf, J. fair-fish Database|catch: A Platform for Global Assessment of Welfare Hazards Affecting Aquatic Animals in Fisheries. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2025, 291, 106732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, J.L.; Arechavala-Lopez, P.; Castanheira, M.F.; Volstorf, J.; Heinzpeter Studer, B. A Global Assessment of Welfare in Farmed Fishes: The FishEthoBase. Fishes 2019, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.W. Key Principles for Understanding Fish Bycatch Discard Mortality. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2002, 59, 1834–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlotto, F.; Castillo, J.; Saavedra, A.; Barbieri, M.A.; Espejo, M.; Cotel, P. Three-Dimensional Structure and Avoidance Behaviour of Anchovy and Common Sardine Schools in Central Southern Chile. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2004, 61, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivle, L.D.; Kvadsheim, P.H.; Ainslie, M.A.; Solow, A.; Handegard, N.O.; Nordlund, N.; Lam, F.-P.A. Impact of Naval Sonar Signals on Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus) during Summer Feeding. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2012, 69, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, A.D.; Roberts, L.; Cheesman, S. Responses of Free-Living Coastal Pelagic Fish to Impulsive Sounds. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 135, 3101–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, H.; Macaulay, G.J.; Ona, E.; Vatnehol, S.; Holmin, A.J. Estimating Individual Fish School Biomass Using Digital Omnidirectional Sonars, Applied to Mackerel and Herring. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 78, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickney, A.P. Factors Influencing the Attraction of Atlantic Herring, Clupea harengus, to Artificial Lights. Fish. Bull. Natl. Ocean. Atmos. Adm. 1969, 68, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman, B. F/V Ruth & Pat Herring Seining 2013 Season (YouTube). 2013. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SFCuSJ1ypY (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Lockwood, S.J.; Pawson, M.G.; Eaton, D.R. The Effects of Crowding on Mackerel (Scomber scombrus L.)—Physical Condition and Mortality. Fish. Res. 1983, 2, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawn, V.M. Physical Properties and Hydrostatic Function of the Swimbladder of Herring (Clupea harengus L.). J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1962, 19, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçalo, A.; (Algarve Centre of Marine Sciences (CCMAR), Faro, Portugal). Personal communication, 2023.

- Pica, A.; (Friend of the Sea®, Milan, Italy). Personal communication, 2023.

- Domenici, P.; Silvana Ferrari, R.; Steffensen, J.F.; Batty, R.S. The Effect of Progressive Hypoxia on School Structure and Dynamics in Atlantic Herring Clupea harengus. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2002, 269, 2103–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltonen, H.; Vinni, M.; Lappalainen, A.; Pönni, J. Spatial Feeding Patterns of Herring (Clupea harengus L.), Sprat (Sprattus sprattus L.), and the Three-Spined Stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus L.) in the Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2004, 61, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmus Nielsen, J.; Lundgren, B.; Jensen, T.F.; Stæhr, K.-J. Distribution, Density and Abundance of the Western Baltic Herring (Clupea harengus) in the Sound (ICES Subdivision 23) in Relation to Hydrographical Features. Fish. Res. 2001, 50, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handegard, N.O.; Tenningen, M.; Howarth, K.; Anders, N.; Rieucau, G.; Breen, M. Effects on Schooling Function in Mackerel of Sub-Lethal Capture Related Stressors: Crowding and Hypoxia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenningen, M.; Peña, H.; Macaulay, G.J. Estimates of Net Volume Available for Fish Shoals during Commercial Mackerel (Scomber scombrus) Purse Seining. Fish. Res. 2015, 161, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenningen, M.; Vold, A.; Isaksen, B.; Svalheim, R.; Olsen, R.E.; Breen, M. Magnitude and Causes of Mortality of Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus) Induced by Crowding in Purse Seines. In Proceedings of the 2012 Annual Science Conference, Bergen, Norway, 17–21 September 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, G.M.; Anders, N.; Bondø, M.S.; Mathiassen, J.R.; Breen, M. Atlantic Mackerel (Scomber scombrus) Change Skin Colour in Response to Crowding Stress. J. Fish Biol. 2022, 100, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobuk, M. 2021 Bait Herring Season: Commercial Fishing Alaska (YouTube). 2022. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h9K2JLduw_Q (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Saldaña, M. Faena de Pesca (YouTube). 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Mb-7Fm7ySU (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- TASA. Conoce Nuestro Proceso de Cala 2018 (YouTube). 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NF12_pzniHk (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Huse, I.; Vold, A. Mortality of Mackerel (Scomber scombrus L.) after Pursing and Slipping from a Purse Seine. Fish. Res. 2010, 106, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, N.; Howarth, K.; Totland, B.; Handegard, N.O.; Tenningen, M.; Breen, M. Effects on Individual Level Behaviour in Mackerel (Scomber scombrus) of Sub-Lethal Capture Related Stressors: Crowding and Hypoxia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejerina, R.; Hermida, M.; Faria, G.; Delgado, J. The Purse-Seine Fishery for Small Pelagic Fishes off the Madeira Archipelago. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 41, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenningen, M.; Macaulay, G.J.; Rieucau, G.; Peña, H.; Korneliussen, R.J. Behaviours of Atlantic Herring and Mackerel in a Purse-Seine Net, Observed Using Multibeam Sonar. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallias, S.L. La Pêche Aux Maquereaux En Corse—PECHE CORSE—Décembre 2018 (YouTube). 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=II67cyPSefM (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Fréon, P.; Avadí, A.; Soto, W.M.; Negrón, R. Environmentally Extended Comparison Table of Large- versus Small- and Medium-Scale Fisheries: The Case of the Peruvian Anchoveta Fleet. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 71, 1459–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-But, J.C.; Sepúlveda, M. Incidental Capture of the Short-Beaked Common Dolphin (Delphinus delphis) in the Industrial Purse Seine Fishery in Northern Chile. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2016, 51, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, A.; Anguita, C.; Daigre, M.; Arce, P.; Vega, R.; Luna-Jorquera, G.; Portflitt-Toro, M.; Suazo, C.G.; Miranda-Urbina, D.; Ulloa, M. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Beached Seabirds along the Chilean Coast: Linking Mortalities with Commercial Fisheries. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 256, 109026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, J.; Monroy, A.; Acha, E.M.; Mianzan, H. Jellyfish Bycatch Diminishes Profit in an Anchovy Fishery off Peru. Fish. Res. 2013, 139, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, I. Pesca de Cerco—Playa Astilleru (YouTube). 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-lPfRAct3w (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Valla, R. Asi Se Pesca La Anchoveta En El Perú (YouTube). 2014. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UXXDsw340NE (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Misund, A.; Beltestad, K. Size-Selection of Mackerel and Saithe in Purse Seine; ICES CM: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1994; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Misund, O.A.; Beltestad, A.K. Survival of Herring after Simulated Net Bursts and Conventional Storage in Net Pens. Fish. Res. 1995, 22, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, D.; Hyldig, G. Influence of Handling Procedures and Biological Factors on the QIM Evaluation of Whole Herring (Clupea harengus L.). Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, N.; Eide, I.; Lerfall, J.; Roth, B.; Breen, M. Physiological and Flesh Quality Consequences of Pre-Mortem Crowding Stress in Atlantic Mackerel (Scomber scombrus). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangua, D.C. Pesca de Anchoveta En Peru (YouTube). 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lpP4shi6QYw (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Tolstorebrov, I.; Eikevik, T.M.; Indergård, E. The Influence of Long-Term Storage, Temperature and Type of Packaging Materials on the Lipid Oxidation and Flesh Color of Frozen Atlantic Herring Fillets (Clupea harengus). Int. J. Refrig. 2014, 40, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carefish/Catch Consortium. Carefish Report—Welfare Assessment in Purse Seine Fisheries. 7p. 2023. Available online: https://carefish.net/catch/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Wahlberg, M. Sounds Produced by Herring (Clupea harengus) Bubble Release. Aquat. Living Resour. 2003, 16, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misund, O.A.; Beltestad, A.K. Survival of Mackerel and Saithe That Escape through Sorting Grids in Purse Seines. Fish. Res. 2000, 48, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, S.C.; Robb, D.H.; van de Vis, J.W. Protocol for Assessing Brain Function in Fish and the Effectiveness of Methods Used to Stun and Kill Them. Vet. Rec. 2002, 150, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. International Guidelines on Bycatch Management and Reduction of Discards|Responsible Fishing Practices for Sustainable Fisheries; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Bellido, J.M.; Santos, M.B.; Pennino, M.G.; Valeiras, X.; Pierce, G.J. Fishery Discards and Bycatch: Solutions for an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management? Hydrobiologia 2011, 670, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Haynes, D.; Talouli, A.; Donoghue, M. Marine Pollution Originating from Purse Seine and Longline Fishing Vessel Operations in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, 2003–2015. Ambio 2017, 46, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Vince, J.; Wilcox, C. Global Estimates of Fishing Gear Lost to the Ocean Each Year. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq0135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.L.; Lane, D.E.; Aldous, D.G.; Nowak, R. Management of the 4WX Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus) Fishery: An Evaluation of Recent Events. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1993, 50, 2742–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, F.; Baptista, V.; Erzini, K. Reconstructing Discards Profiles of Unreported Catches. Sci. Mar. 2018, 82, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FishChoice Atlantic Herring. Available online: https://fishchoice.com/buying-guide/atlantic-herring (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Gamito, R.; Teixeira, C.M.; Costa, M.J.; Cabral, H.N. Are Regional Fisheries’ Catches Changing with Climate? Fish. Res. 2015, 161, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, I.; Feijó, D.; Marçalo, A.; Guerreiro, P.M.; Silva, A. Pilot Experiment to Evaluate the Survival of Chub Mackerel (Scomber colias) after Slipping in the Purse Seine Fishery. In Proceedings of the Iberian Symposium on Modeling and Assessment of Fishery Resources (SIMERPE), Vigo, Spain, 19–22 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, D.J. Blood Component Value Changes in the Atlantic Mackerel (Scomber scombrus L.) Subjected to Capture, Handling and Confinement. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 1983, 76, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, N.; Breen, M.; Saltskår, J.; Totland, B.; Øvredal, J.T.; Vold, A. Behavioural and Welfare Implications of a New Slipping Methodology for Purse Seine Fisheries in Norwegian Waters. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.L. Using Behaviour of Herring (Clupea harengus L.) to Assess Post-Crowding Stress in Purse-Seine Fisheries. Master’s Thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Feijó, D.; Marçalo, A.; Bento, T.; Barra, J.; Marujo, D.; Correia, M.; Silva, A. Trends in the Activity Pattern, Fishing Yields, Catch and Landing Composition between 2009 and 2013 from Onboard Observations in the Portuguese Purse Seine Fleet. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2018, 23, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, I.C.; Marçalo, A.; Feijó, D.; Domingos, I.; Silva, A.A. Interactions between the Common Dolphin, Delphinus delphis, and the Portuguese Purse Seine Fishery over a Period of 15 Years (2003–2018). Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2022, 32, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes, C.M.S.; Velez, J.A.; Nieto, G.C. Workshop of the Classification of the Fishing Gears of the Peruvian Artisanal Fishery; Instituto Del Mar Del Peru: Paita, Peru, 2015; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.; Lankaster, K. Catch Shares in Action: Peruvian Anchoveta Northern-Central Stock Individual Vessel Quota Program; Environmental Defense Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, D.A.; Barrera-Guevara, J.C. Alternativas Tecnológicas Para el Control de Descartes y Reducción de Captura de Juveniles en la Pesquería de Anchoveta; Síntesis Ejecutiva–Versión en Español para Oceana Perú; OCEANA—Protegiendo los Océanos del Mundo: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- SeaChoice Atlantic Herring. SeaChoice. 2023. Available online: https://www.seachoice.org/our-work/species/atlantic-herring/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- FAO. Report of the FAO Working Group on the Assessment of Small Pelagic Fish off Northwest Africa; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; Volume 1247, p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- Perea, Á.; Peña, C.; Oliveros-Ramos, R.; Buitrón, B.; Mori, J. Potential Egg Production, Recruitment, and Closed Fishing Season of the Peruvian Anchovy (Engraulis ringens): Implications for Fisheries Management. Cienc. Mar. 2011, 37, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FromNorway.com Herring. Available online: https://fromnorway.com/seafood-from-norway/herring/ (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- NOAA Fisheries Atlantic Herring Catch Cap|NOAA Fisheries. Available online: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/new-england-mid-atlantic/sustainable-fisheries/atlantic-herring-catch-cap (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Drinkwin, J.; Antonelis, K.; Calloway, M. Methods to Locate and Remove Lost Fishing Gear from Marine Waters; Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada Sustainable Fisheries Solutions and Retrieval Support Program: Glace Bay, NS, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Suazo, C.G.; Cabezas, L.A.; Moreno, C.A.; Arata, J.A.; Luna Jorquera, G.; Simeone, A.; Adasme, L.; Azócar, J.; García, M.; Yates, O.; et al. Seabird Bycatch in Chile: A Synthesis of Its Impacts, and a Review of Strategies to Contribute to the Reduction of a Global Phenomen. Pac. Seab. 2014, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.; Dorey, C. Pain and Emotion in Fishes—Fish Welfare Implications for Fisheries and Aquaculture. Anim. Stud. J. 2019, 8, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.; Isaksen, B.; Ona, E.; Pedersen, A.O.; Pedersen, G.; Saltskår, J.; Svardal, B.; Tenningen, M.; Thomas, P.J.; Totland, B.; et al. A Review of Possible Mitigation Measures for Reducing Mortality Caused by Slipping from Purse-Seine Fisheries. In Proceedings of the 2012 Annual Science Conference, Bergen, Norway, 17–21 September 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fishing Stage | Main Hazards | Potential Mitigation Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Prospection and setting | Noise (sound emission patterns); artificial light; density increase during net setting; contact with net/conspecifics. | Use lower-frequency or passive acoustic devices; limited submerged artificial light exposure; monitor/control fish density in the net. |

| Hauling and crowding | Abrupt temperature and salinity changes; crowding (duration and density); lack of oxygen; contact with net/conspecifics. | Keep hauling speed (<0.2 m/s), crowding duration (<0.3 h), catch volumes low; night captures to reduce gear contact; avoid excessive crowding in last 20% of hauling. |

| Scooping or pumping onboard (emersion) | Abrupt temperature changes; crowding; entrapment of juveniles in small mesh; contact with net, gear (scoop net, pump), conspecifics; high pumping velocity/duration/catch volume; air exposure; predators (birds, marine mammals, turtles, sharks). | Avoid fishing days with sharp difference between air and water temperature; avoid excessive crowding in last 20% of hauling; adapt mesh size to species/season; prefer pumping over scooping to reduce air exposure; reduce pumping speed, duration, and volume (e.g., 1.2–1.8 t/min, ≤85 min, ≤80 t). |

| Handling (i.e., release from the gear) and sorting | Air exposure; handling (dropping, hard landing, trampling); manual sorting (throwing, pressure in boxes, crowding, etc.) | Minimize handling/air exposure; use soft/cushioned landing surfaces; perform in-water sorting when possible. |

| Storage | High stocking densities, pressure, and collisions in tanks/cages; air and ice exposure. | Prefer immediate stunning + slaughter; for in-water storage, use large pens (≥4000 m3) in calm/cold waters and tow pens slowly (≤0.5–0.6 m/s); for in-tank storage, immerse in ice or ice water. |

| Stunning and slaughter | Lack of humane stunning protocols: air and ice slurry exposure. | Implement rapid, efficient stunning followed by immediate slaughter; develop/validate scalable humane slaughter methods for purse seine catches. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maia, C.M.; Samel, V.; Volstorf, J. Purse Seine Capture of Small Pelagic Species: A Critical Review of Welfare Hazards and Mitigation Strategies Through the fair-fish Database. Fishes 2025, 10, 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120614

Maia CM, Samel V, Volstorf J. Purse Seine Capture of Small Pelagic Species: A Critical Review of Welfare Hazards and Mitigation Strategies Through the fair-fish Database. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):614. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120614

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaia, Caroline Marques, Vighnesh Samel, and Jenny Volstorf. 2025. "Purse Seine Capture of Small Pelagic Species: A Critical Review of Welfare Hazards and Mitigation Strategies Through the fair-fish Database" Fishes 10, no. 12: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120614

APA StyleMaia, C. M., Samel, V., & Volstorf, J. (2025). Purse Seine Capture of Small Pelagic Species: A Critical Review of Welfare Hazards and Mitigation Strategies Through the fair-fish Database. Fishes, 10(12), 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120614