Strategies for Broodstock Farming in Arid Environments: Rearing Juvenile Seriola lalandi in a Low-Cost RAS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

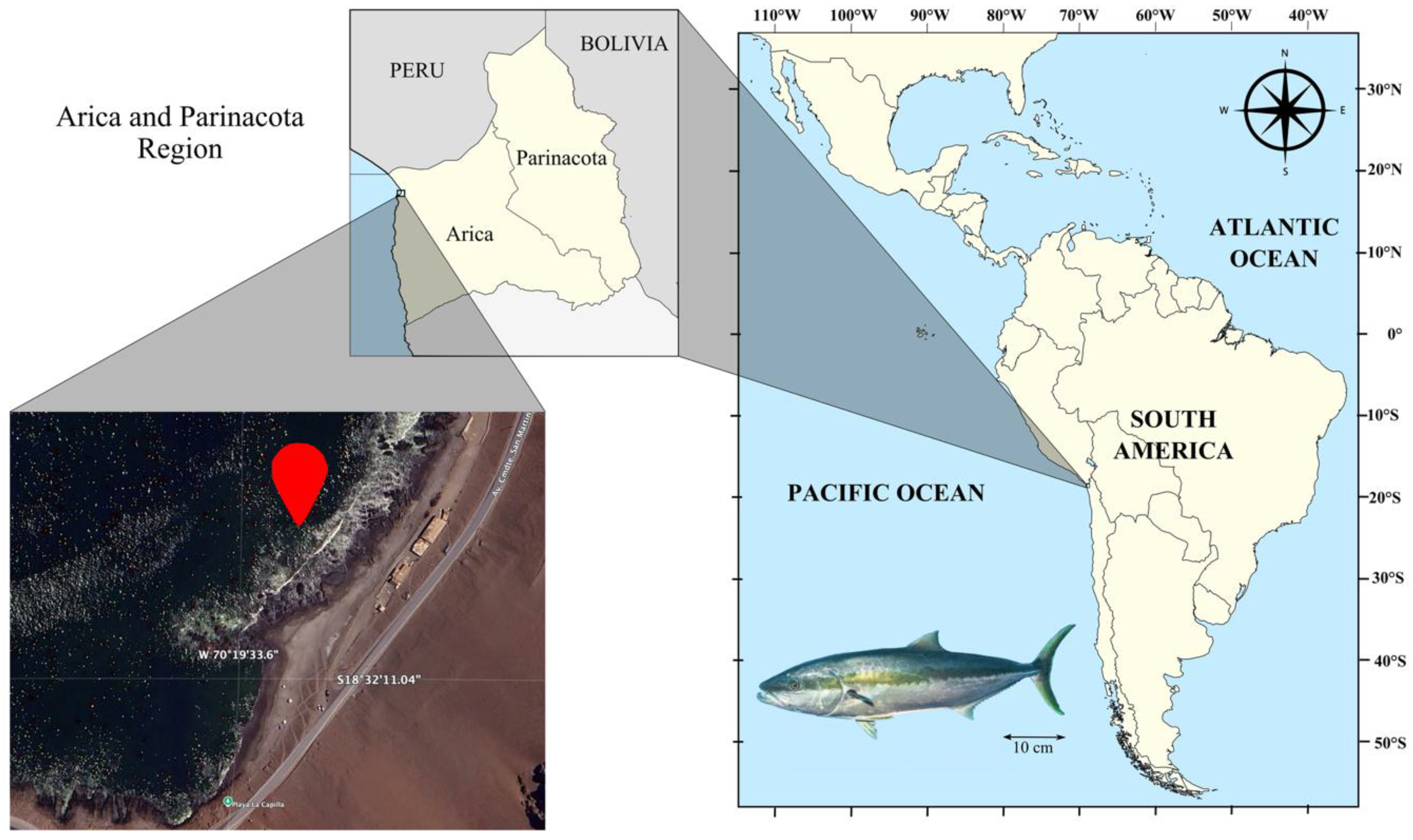

2.1. Study Area

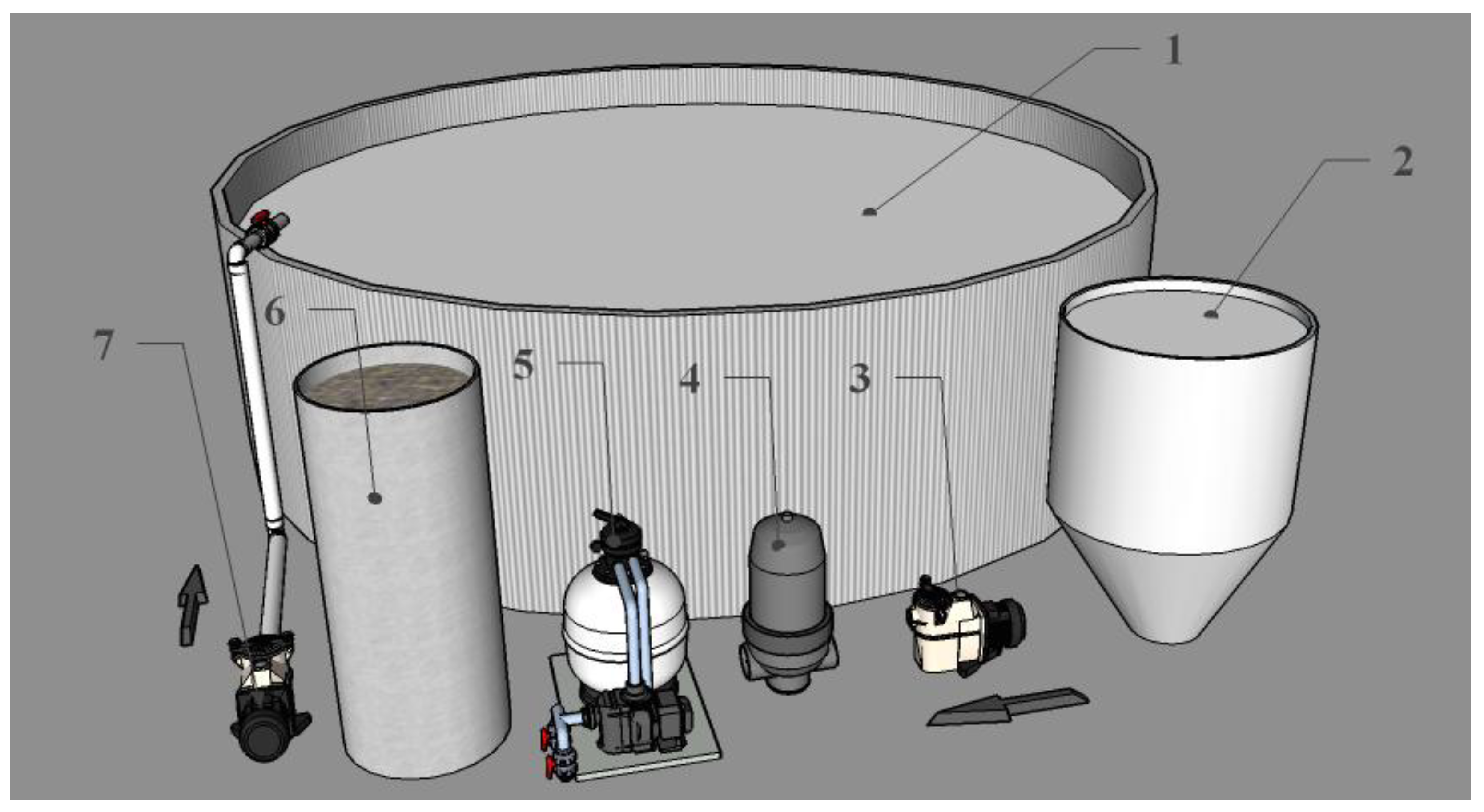

2.2. Recirculating Aquaculture System

2.3. Water Quality Parameters

2.4. Growth

2.4.1. Specific Growth Rate (SGR)

- Wi = Initial weight

- Wf = Final weight

- t = Time (days)

2.4.2. Weight Gain Percentage (%WG)

2.4.3. Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR)

- Fc = Feed consumed (kg)

- Wg = Weight gain (kg)

2.4.4. Survival Rate (%S)

- ni = Initial number of individuals

- nf = Final number of individuals

2.4.5. Fulton’s Condition Factor (K)

- W = Wet body (g)

- L = Length (cm)

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

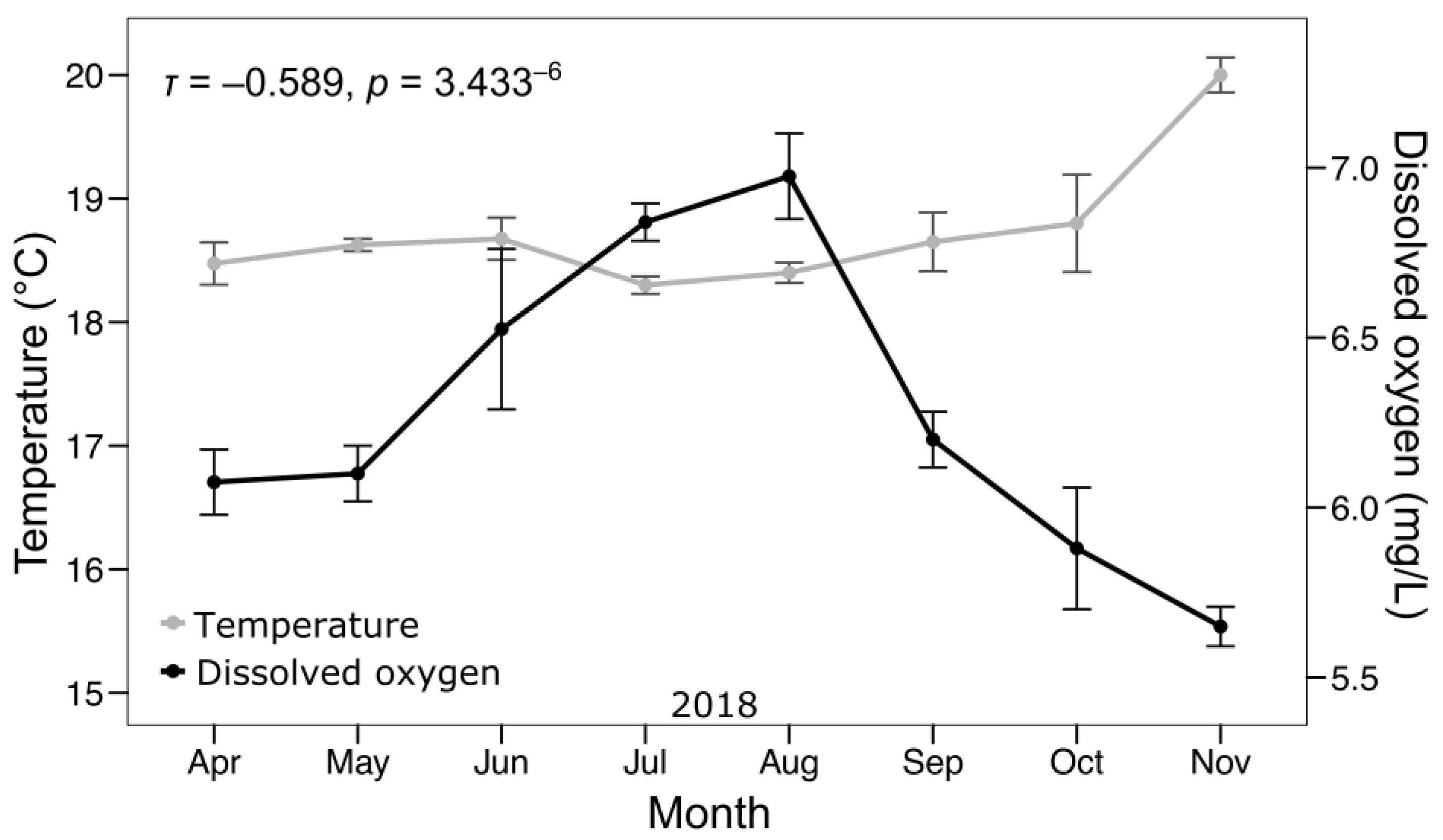

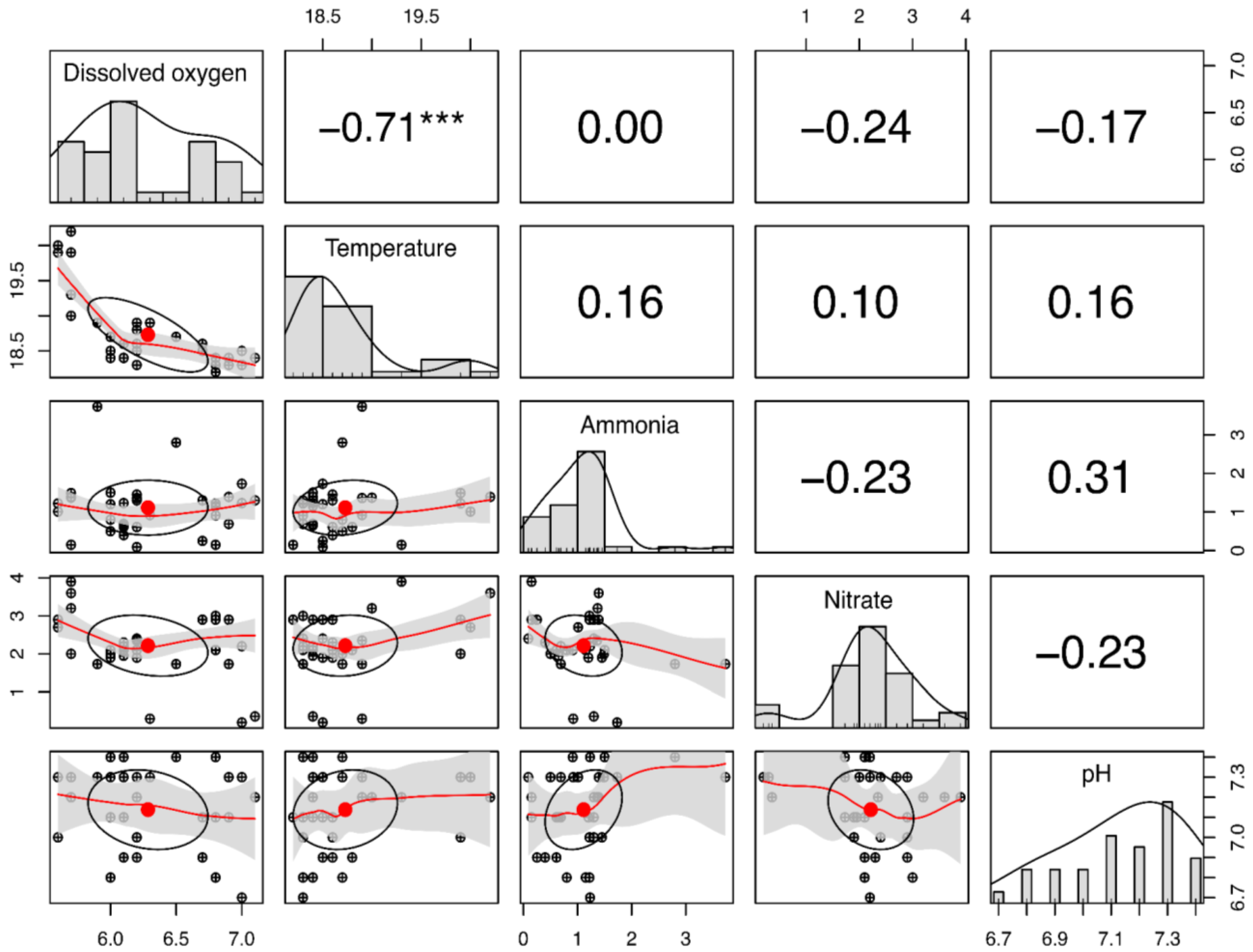

3.1. Water Quality

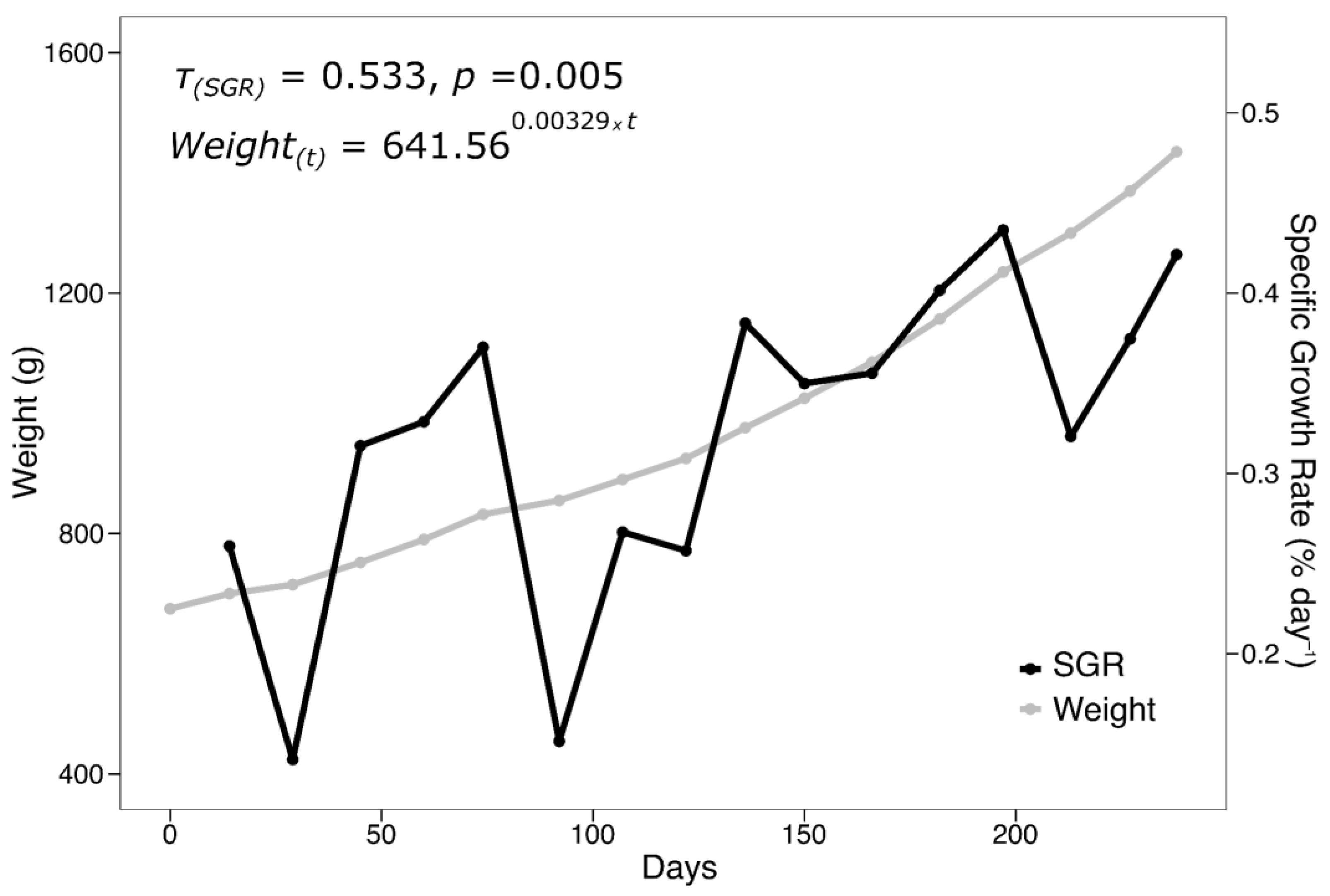

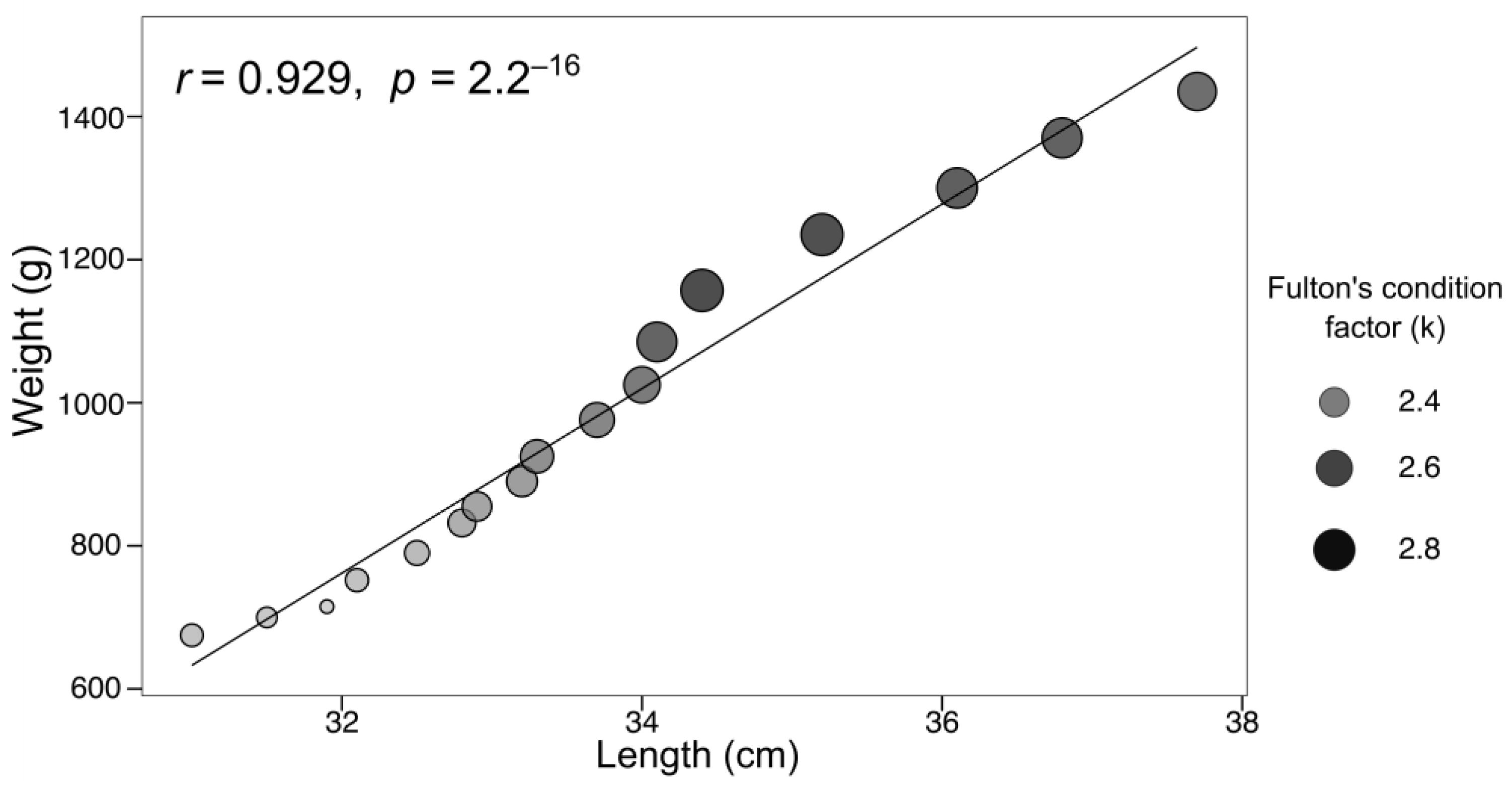

3.2. Evaluation of Growth Parameters

4. Discussion

4.1. Adaptation of S. lalandi to the Culture Tank

4.2. Water Quality

4.3. Growth Parameters

4.4. Difference Between LOW-Cost and High-Cost RAS

4.5. Perspectives and Development of Marine Fish Conditioning

5. Conclusions

- S. lalandi demonstrated successful physiological adaptation to confinement in a low-cost RAS system under arid conditions, reflected in low mortality, progressive acceptance of formulated feed, and sustained growth—supported by positive indicators such as specific growth rate (SGR), Fulton’s condition factor, and the weight–length relationship.

- Water quality remained within suitable parameters throughout the experimental period, although a strong negative correlation between temperature and dissolved oxygen was evident. This reinforces the importance of monitoring these factors in warm environments to optimize the welfare and zootechnical performance of pelagic fishes.

- This experience validates the use of low-cost recirculating systems as a technically and productively viable alternative for conditioning marine species in arid regions, contributing to the diversification of national aquaculture. Although the results of this study are promising and provide a solid basis for future experiments, caution is advised when applying these findings on a large scale, as the study is still in its preliminary stages.

- This study demonstrates that S. lalandi can successfully adapt to a low-cost RAS system in arid conditions. However, future research should focus on hormonal induction and photothermal manipulation strategies to induce spawning, as well as long-term broodstock management to optimize reproduction and ensure the sustainability of farming in arid regions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. Políticas de Pesca y Acuicultura de Chile; OECD, Ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009; ISBN 9789264077188. [Google Scholar]

- SERNAPESCA. Anuario Estadístico de Pesca y Acuicultura 2023; SERNAPESCA: Valparaíso, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Miranda, L.; Ortega, A.; Merino, G. First Natural Spawning of Wild-Caught Premature South Pacific Bonito (Sarda chiliensis chiliensis, Cuvier 1832) Conditioned in Recirculating Aquaculture System and a Descriptive Characterization of Their Eggs Embryonic Development. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 19, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Miranda, L.; Ortega, A.; Merino, G. Descriptive Morphology and Allometric Growth of the Larval Development of Sarda chiliensis chiliensis (Cuvier, 1832) in a Hatchery in Northern Chile. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 19, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, M. Capture-Based Aquaculture of Yellowtail; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008; Volume 508. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, M.A.; Allan, G.L.; Pirozzi, I. Estimation of Digestible Protein and Energy Requirements of Yellowtail Kingfish Seriola lalandi Using a Factorial Approach. Aquaculture 2010, 307, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Abarca, F.; Pepe-Victoriano, R. Peces Marinos del Norte de Chile. Guía Para la Identificación y Mantenimiento en Cautiverio, 1st ed.; Fundación Reino Animal, Ed.; Fundación Reino Animal & ONG Por la Conservación de la Vida Salvaje: Arica, Chile, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, K. Ken Schultz’s Field Guide to Saltwater Fish, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gomon, M.F.; Glover, J.C.M.; Kuiter, R.H. The Fishes of Australia’s South Coast. In The Flora and Fauna of South Australia Handbooks; Reed New Holland: Sydney, Australia, 2008; pp. 1–928. [Google Scholar]

- Symonds, J.E.; Walker, S.P.; Pether, S.; Gublin, Y.; McQueen, D.; King, A.; Irvine, G.W.; Setiawan, A.N.; Forsythe, J.A.; Bruce, M. Developing Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi) and Hapuku (Polyprion Oxygeneios) for New Zealand Aquaculture. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2014, 48, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, G.; Cichero, D.; Patel, A.; Martinez, V. Genetic Structure of Chilean Populations of Seriola Lalandi for the Diversification of the National Aquaculture in the North of Chile. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2015, 43, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechaly, A.S.; Elizur, A.; Escobar-Aguirre, S.; Hirt-Chabbert, J.; Inohuye-Rivera, R.B.; Knibb, W.; Nocillado, J.; Pérez-Urbiola, J.C.; Premachandra, H.K.A.; Somoza, G.M.; et al. Advances in Reproduction, Nutrition and Disease Research in the Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi) Aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, 70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, C.; Katharios, P.; Tsalafouta, A.; Anastasiadis, P.; Henry, M.; Kotzamanis, I.; Izquierdo, M.; Montero, D.; Fernández-Palacios, H.; Hernandez-Cruz, C. Manual Técnico—Seriola (Seriola dumerili); Centro Oceanográfico de Canarias: Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shu-Chien, A.C.; Setiawan, A.; Camara, M.; Wilson, C.; Forsythe, A.; Pether, S.; McQueen, D.; Irvine, G.; Gublin, Y. A Review of Seriola lalandi Aquaculture with a Focus on Recirculating Aquaculture Systems: Synthesis of Existing Research and Emerging Challenges. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, 70059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Aravena-Ambrosetti, H.; Huanacuni, J.I.; Méndez-Abarca, F.; Godoy, K.; Álvarez, N. Feeding Habits of Sarda chiliensis chiliensis (Cuvier, 1832) in Northern Chile and Southern Perú. Animals 2022, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, F.W. Aquacultural Engineering, 1st ed.; Robert, E., Ed.; Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, FL, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Piedrahita, R.; Merino, G.; Uribe, E.; Araneda, M.; Morey, R.; Barraza, J.; Krokordt, K. Tecnología de Recirculación de Agua Aplicada a Cultivos Marinos; Universidad Católica del Norte: Coquimbo, Chile, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Araya, M.; Wurmann, C.; Mery, J.; Vélez, A.; Oxa, P.; León, C.; Fuentealba, S.; Canáles, R. Estrategia Para El Desarrollo de La Acuicultura En La Región de Arica y Parinacota, 2015–2024; CORFO: Arica, Chile, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MINSA. Tabla de Peruana de La Composición Química de Los Alimentos; Reyes-García, M., Gómez-Sanchez Prieto, I., Espinoza-Barrientos, C., Eds.; MINSA: Lima, Perú, 2017; Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/4565836/Tablas-peruanas.pdf?v=1684253633 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ricker, W.E. Growth Rates and Models. In Fish Physiology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume VII, pp. 677–743. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 5th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780131008465. [Google Scholar]

- Bar, I.; Dutney, L.; Lee, P.; Yazawa, R.; Yoshizaki, G.; Takeuchi, Y.; Cummins, S.; Elizur, A. Small-Scale Capture, Transport and Tank Adaptation of Live, Medium-Sized Scombrids Using “Tuna Tubes”. Springerplus 2015, 4, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wexler, J.; Scholey, V.P.; Olson, R.J.; Margulies, D.; Nakazawa, A.; Suter, J.M. Tank Culture of Yellowfin Tuna, Thunnus Albacares: Developing a Spawning Population for Research Purposes. Aquaculture 2003, 220, 327–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowyer, J.N.; Qin, J.G.; Stone, D.A.J. Protein, Lipid and Energy Requirements of Cultured Marine Fish in Cold, Temperate and Warm Water. Rev. Aquac. 2013, 5, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.M.; Pate, W.M.; Hansen, A.G. Energy Density and Dry Matter Content in Fish: New Observations and an Evaluation of Some Empirical Models. Trans. Am. Fish Soc. 2017, 146, 1360392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, K.R.; Drawbridge, M.A. Captive Spawning and Larval Rearing of California Yellowtail (Seriola lalandi). Aquac. Res. 2013, 44, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portz, D.E.; Woodley, C.M.; Cech, J.J. Stress-Associated Impacts of Short-Term Holding on Fishes. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2006, 16, 125–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, R.; Takeuchi, Y.; Amezawa, K.; Sato, K.; Iwata, G.; Kabeya, N.; Yoshizaki, G. GnRHa-Induced Spawning of the Eastern Little Tuna (Euthynnus affinis) in a 70-M3 Land-Based Tank. Aquaculture 2015, 442, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, C.C.; Fostier, A.; Zanuy, S. Broodstock Management and Hormonal Manipulations of Fish Reproduction. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 165, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakriadis, I.; Miccoli, A.; Karapanagiotis, S.; Tsele, N.; Mylonas, C.C. Optimization of a GnRHa Treatment for Spawning Commercially Reared Greater Amberjack Seriola Dumerili: Dose Response and Extent of the Reproductive Season. Aquaculture 2020, 521, 735011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkoff, G.; Broadhurst, A. Intensive Production of Turbot, Scophthalmus maximus, Fry. In Turbot Culture: Problems and Prospects; Lavens, P., Remmerswaal, R.A.M., Eds.; European Aquaculture Society: Oostende, Belgium, 1994; Volume 1, pp. 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez, A.; McEvoy, L.A.; Bell, J.G.; Sargent, J.R. Growth, Survival, Lipid Composition and Pigmentation of Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) Larvae Fed Live-Prey Enriched in Arachidonic and Eicosapentaenoic Acids. Aquaculture 1999, 180, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Araya, M.; Faúndez, V.; Rodríguez, M. Optimización En El Manejo de Reproductores Para Una Mayor Producción de Huevos y Larvas de Psetta maxima (Linneaus, 1758). Int. J. Morphol. 2013, 31, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. Incubation of Turbot Eggs Scophthalmus maximus Publicacions Do Seminario de Estudos Galegos. In Cuadernos da Área de Ciências Marinas; Iglesias, J., Ed.; Edicions do Castro: Sada. A Coruña, Spain, 1989; Volume 1, pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, D.; Quantz, G. Some Effects of Temperature and Salinity on the Embryonic Development and Incubation Time of the Turbot Scophthalmus maximus L., from the Baltic Sea. Meeresforschung 1980, 28, 172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia, E.; Munoz, A.; Flores, H. Water Flow Requirements Related to Oxygen Consumption in Juveniles of Oplegnathus insignis. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2012, 40, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, I.D.; Smol, J.P. Wetzel’s Limnology: Lake and River Ecosystems, 4th ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; ISBN 9780128227015. [Google Scholar]

- Deacutis, C.F. Dissolved Oxygen; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 202–203. [Google Scholar]

- Samaras, A.; Tsoukali, P.; Katsika, L.; Pavlidis, M.; Papadakis, I.E. Chronic Impact of Exposure to Low Dissolved Oxygen on the Physiology of Dicentrarchus labrax and Sparus aurata and Its Effects on the Acute Stress Response. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Araya, M.; Faúndez, V. Efecto de La Temperatura En La Supervivencia Embrionaria y Primeros Estadios Larvales de Psetta maxima. Int. J. Morphol. 2012, 30, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candebat, C.L.; Booth, M.; Williamson, J.E.; Pirozzi, I. The Critical Oxygen Threshold of Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola lalandi). Aquaculture 2020, 516, 734519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.; King, H.; Carter, C.G. Hypoxia Tolerance and Oxygen Regulation in Atlantic Salmon, Salmo salar from a Tasmanian Population. Aquaculture 2011, 318, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowyer, J.N.; Booth, M.A.; Qin, J.G.; D’Antignana, T.; Thomson, M.J.S.; Stone, D.A.J. Temperature and Dissolved Oxygen Influence Growth and Digestive Enzyme Activities of Yellowtail Kingfish Seriola lalandi (Valenciennes, 1833). Aquac. Res. 2014, 45, 2010–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.D.; Seymour, R.S. Cardiorespiratory Physiology and Swimming Energetics of a High-Energy-Demand Teleost, the Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola lalandi). J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 3940–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harford, A.R.; McArley, T.; Morgenroth, D.; Danielo, Q.; Khan, J.; Sandblom, E.; Hickey, A.J.R. Effects of Manipulating Kingfish (Seriola lalandi) Routine Oxygen Demand and Supply on Ventricular and Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Function. Aquaculture 2024, 589, 740969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkhani, S.; Zaker, N.H. The Effects of Climate Change on the Thermal Stratification of the Gulf of Oman. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 2025, 110, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morée, A.L.; Clarke, T.M.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Frölicher, T.L. Impact of Deoxygenation and Warming on Global Marine Species in the 21st Century. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 2425–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wei, D.; Ding, R.; Wu, Y.; Gao, H.; Liao, A.; Tang, Y.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; et al. Tailor-Made Ammonia Nitrogen Risk Management with Machine Learning Models for Aquatic Environments in the Mainland of China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netten, J.J.C.; van der Heide, T.; Smolders, A.J.P. Interactive Effects of PH, Temperature and Light during Ammonia Toxicity Events in Elodea canadensis. Chem. Ecol. 2013, 29, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ye, Z.; Qi, M.; Cai, W.; Saraiva, J.L.; Wen, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, J. Water Quality Impact on Fish Behavior: A Review From an Aquaculture Perspective. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, 12985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J.; Hartemink, A.E. The Effects of PH on Nutrient Availability Depend on Both Soils and Plants. Plant Soil. 2023, 487, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temporetti, P.; Beamud, G.; Nichela, D.; Baffico, G.; Pedrozo, F. The Effect of PH on Phosphorus Sorbed from Sediments in a River with a Natural PH Gradient. Chemosphere 2019, 228, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhappel, T.K.; Burman, O.H.P.; John, E.A.; Wilkinson, A.; Pike, T.W. The Impact of Water PH on Association Preferences in Fish. Ethology 2019, 125, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownscombe, J.W.; Raby, G.D.; Murchie, K.J.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Cooke, S.J. An Energetics–Performance Framework for Wild Fishes. J. Fish. Biol. 2022, 101, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wootton, R.J. Growth: Environmental Effects. In Encyclopedia of Fish Physiology: From Genome to Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 1–3, pp. 1629–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gairin, E.; Dussenne, M.; Mercader, M.; Berthe, C.; Reynaud, M.; Metian, M.; Mills, S.C.; Lenfant, P.; Besseau, L.; Bertucci, F.; et al. Harbours as Unique Environmental Sites of Multiple Anthropogenic Stressors on Fish Hormonal Systems. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2022, 555, 111727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kır, M. Thermal Tolerance and Standard Metabolic Rate of Juvenile Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata) Acclimated to Four Temperatures. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 93, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, I.; Åm, A.L.; Kolarevic, J.; Ytrestøyl, T.; Vadstein, O.; Attramadal, K.J.K.; Terjesen, B.F. Microbial Community Dynamics in Semi-Commercial RAS for Production of Atlantic Salmon Post-Smolts at Different Salinities. Aquac. Eng. 2017, 78, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, P.; Dioguardi, M.; Cammarata, M.; Zupa, W.; Vazzana, M.; Spedicato, M.T.; Lembo, G. Basic Knowledge of Social Hierarchies and Physiological Profile of Reared Sea Bass Dicentrarchus labrax (L.). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0208688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.; Fernandes, I.M.; Penha, J.; Mateus, L. Intra and Not Interspecific Competition Drives Intra-Populational Variation in Resource Use by a Neotropical Fish Species. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2019, 102, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahida, R.; Rajesh, M.; Sharma, P.; Pandey, N.; Pandey, P.K.; Suresh, A.V.; Angel, G.; Chadha, N.K.; Sawant, P.B.; Pandey, A.; et al. Stocking Density Affects Growth, Feed Utilisation, Metabolism, Welfare and Associated MRNA Transcripts in Liver and Muscle of Rainbow Trout More Pronouncedly than Dietary Fish Meal Inclusion Level. Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okendro, S.N.; Paul, A.K.; Wasi Alam, M.D. Non-Linear Models to Describe Growth Pattern of Tor Putitora (Hamilton) under Monoculture and Polyculture Systems. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 77, 1346–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue, C.G.; Partridge, G.J.; Sequeira, A.M.M. Bioenergetic Growth Model for the Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola lalandi). Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdaoui, A.; Khoufi, W.; Hmila, W.; Mahé, K.; Jabeur, C. Enhancement of Growth Estimates for Under-Sampled Species Using a Bayesian Approach, Case of Seriola dumerili (Risso, 1810) in the Southern Centre of the Mediterranean Sea. Biol. Bull. 2023, 50, S637–S646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, M.J.; Bonifacio, A.F.; Brito, J.M.; Rautenberg, G.E.; Hued, A.C. Length–Weight Relationships and Body Condition Indices of a South American Bioindicator, the Native Neotropical Fish Species, Cnesterodon decemmaculatus (Poeciliidae). J. Ichthyol. 2023, 63, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, F.; Yadav, S.; Yadav, A.; Serajuddin, M. Length-Weight Relationship and Condition Factor of Four Actinopterygii, Perciformes Ray-Finned Fish Species of India. Isr. J. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 71, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.S.S.; Balasubramanian, C.P.; Aravind, R.; Biju, I.F.; Rajan, R.V.; Vinay, T.N.; Panigrahi, A.; Sudheer, N.S.; Rajamanickam, S.; Kumar, S.; et al. Reproductive Performance of Captive-Reared Indian White Shrimp, Penaeus indicus, Broodstocks over Two Generations. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, K.M. The Effect of Temperature on Growth of Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua L.). ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1995, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Pepe-Vargas, P.; Huanacuni, J.I.; Aravena-Ambrosetti, H.; Olivares-Cantillano, G.; Méndez-Abarca, F.; Méndez, S.; Espinoza-Ramos, L. Conditioning of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Broodstock in a High-Altitude Recirculating Aquaculture System: First Spawning at 3000 m.a.s.l. in Northern Chile. Animals 2025, 15, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Pepe-Vargas, P.; Pérez-Aravena, A.; Aravena-Ambrosetti, H.; Huanacuni, J.I.; Méndez-Abarca, F.; Olivares-Cantillano, G.; Acosta-Angulo, O.; Espinoza-Ramos, L. Evaluation of Water Quality in the Production of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) in the Precordilleran Region of Northern Chile. Water 2025, 17, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genaro Soto-Zarazúa, M.; Herrera-Ruiz, G.; Rico-García, E.; Toledano-Ayala, M.; Peniche-Vera, R.; Ocampo-Velázquez, R.; Guevara-González, R.G. Development of Efficient Recirculation System for Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Culture Using Low Cost Materials. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 5203–5211. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Jia, C.; Gui, F.; Xu, J.; Yin, X.; Feng, D.; Zhang, Q. Recent Advances in the Hydrodynamic Characteristics of Industrial Recirculating Aquaculture Systems and Their Interactions with Fish. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, J.L.; Arechavala-Lopez, P.; Sneddon, L.U. Farming Fish. In Routledge Handbook of Animal Welfare; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey, L.; Fontaine, P.; Lecocq, T. Unlocking the Intraspecific Aquaculture Potential from the Wild Biodiversity to Facilitate Aquaculture Development. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2212–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, M.B.; Ebeling, J.M.; Piedrahita, R.H. Acuicultura En Sistemas de Recirculación; Cayuga Aqua Ventures: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sirakov, I.; Velichkova, K. Factors Affecting Feeding of Fish Cultivated in Recirculation Aquaculture System: A Review. Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2023, 16, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Attramadal, K.J.K.; Salvesen, I.; Xue, R.; Øie, G.; Størseth, T.R.; Vadstein, O.; Olsen, Y. Recirculation as a Possible Microbial Control Strategy in the Production of Marine Larvae. Aquac. Eng. 2012, 46, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attramadal, K.J.K.; Øie, G.; Størseth, T.R.; Alver, M.O.; Vadstein, O.; Olsen, Y. The Effects of Moderate Ozonation or High Intensity UV-Irradiation on the Microbial Environment in RAS for Marine Larvae. Aquaculture 2012, 330–333, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorson, H.O.; Quezada, F. Marine Biotechnology. In Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences; Cochran, J.K., Bokuniewicz, H.J., Yager, P.L., Eds.; Credo Reference; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; Volume 5, pp. 615–621. ISBN 9780128130827. [Google Scholar]

- Harun, S.N. Towards Sustainable Aquaculture: A Brief Look into Management Issues. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter/Nutrient | Fresh Food (Odontesthes regia) (MINSA, 2017 [19]) | Commercial Dry Food (Skretting, NOVA ME 2000) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of food | Whole fresh fish | Pellet formulated for marine breeders |

| Pellet size (mm) | - | 1.5–9.0 |

| Crude protein (%) | 19.4 | 52.0 |

| Lipids (%) | 2.4 | 22.0 |

| Crude fiber (%) | - | 1.2 |

| Crude ash (%) | - | 12.0 |

| Moisture (%) | 76.5 | 10.0 |

| Gross energy (MJ/kg) | 0.041 | 22.77 |

| Feeding frequency (times/day) | 1 | 2 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Feed delivered (kg) | 922.78 |

| Initial biomass (kg) | 31.05 |

| Final biomass (kg) | 66.01 |

| Weight input (gr) | 760 |

| Initial density (kg/m3) | 0.52 |

| Final density (kg/m3) | 1.10 |

| Initial number of fish | 46 |

| Final No. of fish | 46 |

| FCA | 1.21 |

| SGR | 0.32 |

| % WG | 112.59 |

| % Survival | 100 |

| Fulton’s condition | 1.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pepe-Victoriano, R.; Pepe-Vargas, P.; Borquez-Segovia, E.; Huanacuni, J.I.; Aravena-Ambrosetti, H.; Méndez-Abarca, F.; Resurrección-Huertas, J.Z.; Espinoza-Ramos, L.A. Strategies for Broodstock Farming in Arid Environments: Rearing Juvenile Seriola lalandi in a Low-Cost RAS. Fishes 2025, 10, 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110579

Pepe-Victoriano R, Pepe-Vargas P, Borquez-Segovia E, Huanacuni JI, Aravena-Ambrosetti H, Méndez-Abarca F, Resurrección-Huertas JZ, Espinoza-Ramos LA. Strategies for Broodstock Farming in Arid Environments: Rearing Juvenile Seriola lalandi in a Low-Cost RAS. Fishes. 2025; 10(11):579. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110579

Chicago/Turabian StylePepe-Victoriano, Renzo, Piera Pepe-Vargas, Elizabeth Borquez-Segovia, Jordan I. Huanacuni, Héctor Aravena-Ambrosetti, Felipe Méndez-Abarca, Juan Zenón Resurrección-Huertas, and Luis Antonio Espinoza-Ramos. 2025. "Strategies for Broodstock Farming in Arid Environments: Rearing Juvenile Seriola lalandi in a Low-Cost RAS" Fishes 10, no. 11: 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110579

APA StylePepe-Victoriano, R., Pepe-Vargas, P., Borquez-Segovia, E., Huanacuni, J. I., Aravena-Ambrosetti, H., Méndez-Abarca, F., Resurrección-Huertas, J. Z., & Espinoza-Ramos, L. A. (2025). Strategies for Broodstock Farming in Arid Environments: Rearing Juvenile Seriola lalandi in a Low-Cost RAS. Fishes, 10(11), 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110579