Abstract

Voice syncretism is widely attested crosslinguistically. In this paper, we discuss three different types of Voice syncretism, under which the same morpheme participates in different configurations. We provide an approach under which the same Voice head can convey different interpretations depending on the environment it appears in, thus building on the notion of allosemy. We show that, in all cases under investigation, allosemy is closely associated with the existence of idiosyncratic patterns. By contrast, we notice that allosemy and idiosyncrasy are not present in analytic passive and causative constructions across different languages. We argue that the distinguishing feature between the two types of constructions is whether the passive and the causative interpretation comes from the Voice head, thus forming a single domain with the vP or whether passive and causative semantics are realized by distinct heads above the Voice layer, thus forming two distinct domains.

Keywords:

voice syncretism; middle voice; passive; anticausative; reflexive; reciprocal; antipassive; causative; allosemy; idiosyncrasy 1. Introduction

This paper deals with Voice syncretism across languages. In particular, we look at patterns in which the same morphology appears in different types of argument structure alternations. This involves a variety of different constructions, with the most well-discussed types being:

- Type A: The middle syncretism in which the same morpheme appears at least in reflexive, (reciprocal), anticausative and passive constructions.

- Type B: The antipassive, reflexive, (reciprocal), anticausative, passive syncretism.

- Type C: The causative/anticausative/passive syncretism (attested mostly in Korean and Tungusic languages).

While these types of syncretism, and especially type A and type C, have been extensively discussed in typological research, there have been few attempts to explain multifunctionality from a compositional point of view. Most studies are concerned with the middle syncretism which is widely attested crosslinguistically (Alexiadou and Doron [1] for Greek and Hebrew, Alexiadou et al. [2], Kastner [3], Kastner [4]). For type B syncretism, there are some works discussing antipassive constructions providing a unified account with other constructions (e.g., Basilico [5]) but not for the entire array of complex syncretism attested in several languages. For type C syncretism, there are works mostly on Korean which are attempting a partial unified analysis, see, e.g., [6], who presents a unifying analysis of the morpheme -I- in causatives and anticausatives, or a unified analysis of causatives and adversative passives but not an analysis of all the constructions exhibiting the same morpheme [6,7,8,9]. While in principle it is possible that the syncretism observed does not imply a unifying analysis, we consider it important that especially type A and type B syncretisms are widely attested in a number of genetically and geographically unrelated languages, as recently shown by the extensive crosslinguistic survey of syncretism in [10].

Thus, in this paper, we make an attempt to address this issue of multifunctionality from a minimalist point of view. In particular, following a contextual allosemy analysis within the Distributed Morphology framework [11,12,13,14,15,16], we argue that the syncretic morphemes are Voice heads in the sense that, at least partially, they convey some information about the external argument. In this way, we tackle the question of multifunctionality from a compositional perspective. The main contribution of this work, however, is not the modeling of contextual allosemy in these syncretic environments but rather to establish a distinction between heads that are contextually allosemic and heads which have a designated interpretation and are not affected by their complements. In particular, we compare these constructions with the analytic passive and causative in certain languages, arguing that the analytic passive/causative are different from the passive/causative in syncretic constellations in the following ways:

- 1

- All cases of syncretic Voice involve synthetic morphology (i.e., a suffix/prefix) (clitics, e.g., sich/se, will not be considered).

- 2

- Analytic (periphrastic) passives of the form (AUX + PRTC) do not exhibit the same multifunctionality. In languages which have both synthetic and analytic constructions, analytic constructions always have a designated interpretation.

- 3

- In most cases reported in the literature, and the ones that we focus on in the paper, the kind of interpretation derived depends on the properties of its complement.

- 4

- Synthetic but not analytic morphology can lead to idiosyncratic gaps or idiosyncratic/idiomatic interpretations.

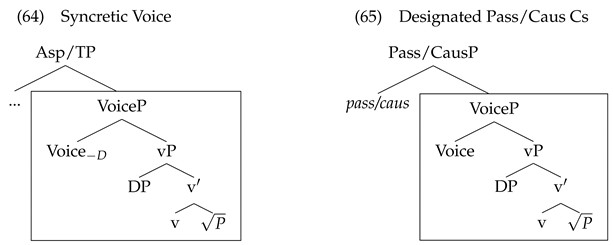

We aim to explain these properties (i.e., multifunctionality, vP dependency, idiosyncrasies) within a Distributed Morphology framework under which a synthetic Voice construction can create a phasal domain with its complement [2,12,13,17,18]. In particular, we analyze the syncretic morphology in the aforementioned constructions as an exponent of a Voice head forming a single domain with the embedded vP. By contrast, we argue that the analytic constructions under discussion involve an additional passive/causative head above the Voice layer, forming two domains instead and preventing vP dependency and idiosyncrasies (following [1,2] that Voice in Greek (and other “middle” languages) is lower than the so called passive Voice head in English [19].

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, we introduce a background into the notion of Voice and provide our definition of Voice that we use throughout the paper. In Section 3, we discuss type A syncretism, focusing on Greek. In Section 4, we discuss type B syncretism, providing an analysis of antipassive as involving a specifierless expletive Voice head. In Section 5, we discuss type C syncretism, focusing on Korean. Throughout these sections, we emphasize the contextual dependencies and the idiosyncrasies that emerge. In Section 6, we discuss the difference between synthetic and analytic constructions, accounting for the fact that the latter do not exhibit the same dependencies and idiosyncrasies. We conclude with open questions and further ways to restrict the proposed analysis.

2. Background: The Notion of Voice and Valency Operations

In this section, we briefly outline our basic assumptions for verbal constructions and the notion of Voice. Voice is used in very different ways in linguistic works. Voice has been used as a term to describe the familiar active/passive alternation in many Indo-European languages, but it is also widely used to describe argument increasing/decreasing alternations, such as the so-called middle Voice which refers to reflexive, reciprocal, benefactive, dispositional middle, passive, deponent and other constructions [1,20,21,22]. In addition, causative formation is sometimes referred to as causative Voice. The constructions in which the internal argument is demoted was termed antipassive Voice as the counterpart of passive in ergative–absolutive languages. The use of the term Voice alternations for all these types of constructions, both in typological research as well as in the generative framework, carries different connotations depending on the type of analysis assumed for the category Voice. In the generative framework, the term Voice was originally used to refer to the active/passive alternation as a transformation [23]. However, in the 1990s, the term was used more and more in association with the external argument. Angelika Kratzer, in [24], building on accumulated evidence for argument-related heads [25,26,27,28,29,30], provided an explicit analysis of a Voice head which introduces the external argument. In a different style, around the same time, Embick analyzes Greek non-active Voice morphology as an exponent of little-v in the absence of an external argument. Essentially, the way Voice is used in the two cases is quite different. Under Kratzer’s view, Voice has semantic content, introducing the external argument [24]. Embick concentrates more on the morphology, treating Voice as a morphological exponent for the absence of an external argument [16,31]. Despite the different way that Voice is approached in the two works, as we will see, a lot of work afterward combined insights from both approaches to formulate an analysis regarding argument structure alternations in various languages.

Typological research brings forth important crosslinguistic patterns of Voice syncretism, mostly concerning the middle Voice (involving at least the reflexive, reciprocal, anticausative and passive constructions) [20,21,22] but also other correlations between the antipassive and the reflexive/anticausative in ergative–absolutive languages and the passive/causative in Korean and Tungusic languages [32,33]. These studies concentrate on figuring out common semantic or syntactic properties between the different classes (i.e., affectedness in middle Voice or demotion of an argument in passive/antipassive constructions), without, however, providing a compositional account for how to derive the different interpretations.

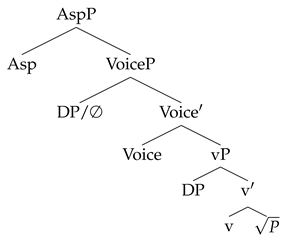

In this paper, Voice is a head that merges with the vP and specifies the requirement for an external argument. We follow Schäfer’s analysis in [34], and much subsequent work, in which Voice can be either semantically contentful, introducing a thematic argument, or it can be expletive. Crucially, we also adopt the idea discussed in [2,34,35] that Voice is obligatory only when the verbal root carries a specification in the lexicon as [+EXT], a feature that requires the verbal root to be embedded under a VoiceP, whether it is semantically contentful or null. We also distinguish between argument-related heads above the VoiceP layer, i.e., a causative or a passive head above VoiceP or a high-Appl and below the VoiceP, i.e., lower argument introducing head as in ditransitives/low applicatives. With these considerations in mind, we take (1) to represent the typical syntax of Voice.

- (1)

- Basic configuration with Voice.

3. Type A Syncretism (Reflexive, Reciprocal, Anticausative, Passive) ⇝ [-D]

The term middle Voice as a cover term for all the constructions in (2) is introduced in typological studies (e.g., Kemmer 1993). The multifunctional character of such morphemes has also received great attention within the generative framework for different languages [2,4,36,37,38]. The analysis in the current section largely builds on these works.

Middle Voice, in most languages, involves at least the categories in (2).1 The reflexive in (2a) indicates that Ana pinched herself. In (2b), there is a special type of reflexive, termed figure reflexive, indicating that Ana pushed herself into the cave. The reciprocal always requires a plurality of individuals as in (2c). The sentence in (2d) is most naturally interpreted as an anticausative, i.e., that Ana got scratched by mistake. As we will see later, other interpretations are not excluded. Finally, (2e) is most naturally interpreted as a passive construction with an implicit or explicit agent.

- (2)

- Middle Voice patterns.

- a.

- I Ana tsimbithike (gia na di an onirevete). Reflexivethe Ana pinch.Nact.pst.3sg (for subj see.3sg if dream.3sg)‘Ana pinched herself to check if she was dreaming.’

- b.

- I Ana hothike mesa sti spilia. Figure Reflexivethe Ana cram.Nact.pst.3sg into the cave‘Ana pushed herself into the cave.’

- c.

- I Ana ke o Petros agaliastikan. Reciprocalthe Ana and the Peter hug.Nact.pst.3sg‘Ana and Peter hugged.’

- d.

- I Ana gratzunistike. Anticausativethe Ana scratch.Nact.pst.3sg‘Ana got scratched.’

- e.

- I Ana eksetastike apo ti giatro. Passivethe Ana examine.Nact.pst.3sg by the doctor‘Ana was examined by the doctor.’

Although the patterns in (2a–2e) are the most commonly discussed in type A syncretism, there are more mentioned in various studies. Another construction is the feel-like construction which is common in many languages with middle Voice [39,40,41]. Here, we present an example from Albanian, as in (3a), in which the experiencer argument surfaces with dative case and the internal argument receives nominative as discussed in [40]. Similarly, in Russian, the feel-like construction requires a dative experiencer as discussed by [42] and if there is an internal argument it is expressed with nominative case [41]. This construction is another instance of [-D] Voice:

- (3)

- Feel-like construction.

- a.

- Anës i lexo-het një libër.Ann.dat her.cl.dat read.nact.pres.3sg a book‘Ann feels like reading a book.’

- b.

- Segodnja mne ne rabotaetsja.Today me.dat not work.3sg.NAct‘Today I don’t feel like working.’

The feel-like construction is not attested across all languages. Greek, for example, does not have this function with non-active Voice, although a feel-like interpretation is associated sometimes with non-active morphology but without a dative construction (e.g., ksinome ‘I feel like scratching’). Notice, however, that [43] reports that in the northern Greek dialect of Naousa, a dative feel-like construction is possible as exemplified in (4). The availability of this construction in the northern dialect of Naousa is important because it shows that the licensing conditions for the emergence of certain constructions exist and under the appropriate circumstances (in this case, as [43] explains, it is language contact with southern Slavic dialects) these constructions can become available in the language.

- (4)

- Mu pin-ete enas kafes.I.dat.1sg drink.nact.pres.3sg a.nom coffee‘I feel like drinking coffee. [43] (7)

Furthermore, as [41] discusses, within the languages that exhibit these patterns, there are restrictions for the predicates allowing this type of interpretation.

Another construction which is often reported for various languages is the benefactive reflexive (do sth for oneself). Although benefactive reflexives were very productive in Ancient Greek (e.g., leg-ō ‘pick up’ → legomai ‘pick up for myself’) [44], they are not productive in Modern Greek, but there are some intransitive predicates with self-benefactive interpretation derived from transitive predicates as illustrated in (5).

- (5)

- I Ana psonistike. Benefactive reflexivethe Ana shop.Nact.pst.3sg‘Ana shopped for herself.’

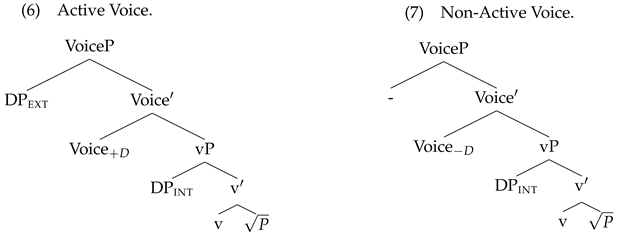

Various ways have been suggested to account for the different interpretations with middle Voice. Here, we follow an approach which builds on the original proposal by [16,31], and it is further elaborated in the bivalent Voice system suggested in [2] under which Voice can have a [-D] feature, suggesting the lack of a DP specifier. Under this view, non-active morphology is the exponent of Voice [-D]. Thus, the unifying feature across all the different constructions is Voice [-D]. However, other than this unifying property, the constructions differ a lot in their syntax and semantics. The different interpretations that emerge depend on the properties of the embedded vP. This leads us to an account based on the notion of allosemy [12,13,37,45]. Allosemy emerges when the same head receives a different interpretation depending on the context it appears in. The fact that the allowed interpretations with non-active Voice are largely dependent on the properties of the embedding predicates suggests that this analysis is on the right track. Thus, under this system, Voice differs as to whether it has a DP specifier as in the case of active in (6) or lacks one as in non-active Voice (7). Type A syncretism refers to all constructions that involve the configuration in (7).

Now, the question is how the different interpretations arise under the general syntactic representation in (7). As we have outlined in the introduction, we follow an allosemic approach, based on which the different interpretations depend on the properties of the embedded vP. The idea of allosemy is developed in a series of works [12,13,14,45,46]. The work of [2] that we build on partly relies on an allosemic account, which we extend to account for non-active reflexives and reciprocals, building on [47,48].

The first thing that we need to do in order to define the interpretation of Voice under an allosemy approach is to define the different environments that Voice[-D] emerges. Below, we distinguish four different environments to account for passives, reflexives, reciprocals and anticausatives. A basic question for all allosemic approaches is how the relevant semantic properties of the vP are encoded in grammar.2 For example, what do we mean by agentive? Is there an agentivity feature associated with the root? This issue is discussed in [2,13,34,35] where it is pointed out that agentivity is a property that is defined with respect to the entire vP, i.e., the root with the verbalizer and the internal argument (see also Kratzer [24], Marantz [25]). In other words, the insight in these works is that there is no feature attached to the root which indicates agentivity but is an interpretation which has to do with the meaning of the entire vP. However, we want to argue that a feature at the root level is important. In particular, we argue that roots can come with different features. For example, the verbs pleno ‘wash’ or fotografizo ‘photograph’ are optionally reflexive, i.e., they are defined in the lexicon as [+/−Refl]. By contrast, the verb katigoro ‘accuse’ is [-Refl]; thus, it cannot have a reflexive interpretation in non-active Voice. This is because Voice only acquires this interpretation in the context of a [+Refl] vP. Of course, whether a predicate has an agentivity/reflexivity/reciprocity feature depends on its lexical meaning and our encyclopedic knowledge. Crucially, whereas there are many properties which are relevant for the lexical meaning of a verb (i.e., whether it has a positive or negative effect), only certain properties are relevant for the interpretation of Voice. Agentivity, reflexivity and reciprocity are the relevant features for the interpretation of Voice and thus they are part of the information encoded in our lexicon. Although these features do not result in a different denotation for the vP, they result in different semantics for the VoiceP, thus deriving the attested syncretism. Below, we elaborate for each pattern in order to clarify how the different interpretations are derived.

When Voice[-D] merges with an agentive predicate, it gives rise to a passive interpretation under which the Voice head introduces an existentially bound agent [1,2], as shown in (8a). When the embedded predicate is reflexive (either as a natural reflexive verb or marked with a reflexive prefix which, in the case of Greek, is afto ’self’), a reflexive interpretation arises under which the agent is identified with the theme argument, as illustrated in (8b). This analysis shares with the analysis in [49] for French reflexives the idea that Voice is responsible for identifying the external with the internal argument. The critical difference between Labelle’s approach and the current approach is that, under her analysis, reflexives are unergatives, i.e., Voice actually introduces a syntactic argument in its specifier, while under the current proposal, the theme argument is saturated in its base position and Voice simply introduces an identity relation between the agent and the theme of the event without adding an extra syntactic argument.

A different possibility is that the embedded vP has a reciprocal interpretation. We present in (8c) a simplified interpretation for reciprocal predicates under which there are only two subevents. The core meaning is that there is a superevent which involves at least two subevents and and the agent in is the theme in and the agent in is the theme in . Similar to reflexives, we have an identification of the agent and the theme in a superevent, in this case in a symmetric reciprocal relation. This analysis bears many similarities with Siloni’s account in [50]. The main difference in our account is that identification is part of the semantic composition during the syntactic derivation, and it is not a lexical operation (see also [51]). It is also important to notice that, under the current analysis, non-active reflexive and reciprocal verbs are unaccusatives (see [52,53]).

For anticausatives, we follow [34], and much subsequent work building on [34], in assuming that Voice has no semantic contribution in these constructions, thus yielding an identity function, as shown in (8d).

- (8)

- Voice / vP=. &

- Voice / vP=&

- Voice / vP=&&&

- Voice / vP=

The allosemy approach makes certain predictions for the derived patterns. First, we predict that non-agentive predicates cannot form a passive. As discussed in [1,35], in Greek as well as in other languages, the so-called mediopassive is formed with agentive verbs and only agentive by-phrases are licensed. For example, psychological predicates with an experiencer as an external argument are predicted to not form a passive as illustrated in (9b) [47,54,55]:

- (9)

- I theates apolafsan tin parastasi.the audience enjoy.Nact.pst.3pl the show‘The audience enjoyed the show.’

- *I parastasi apolafstike apo tus theates.the performance enjoy.Nact.pst.3sg by the audience‘The performance was enjoyed by the audience.’

Notice that certain subject experiencer verbs can form a passive but, in these cases, an agentive interpretation is acquired not referring to an actual psychological state but rather to a process which involves an agentive interpretation. In (10), it has an interpretation that the performance was approved and supported by the audience.

- (10)

- I parastasi agapithike apo tus theates.the performance love.Nact.pst.3sg by the audience‘The performance was loved by the audience.’

The allosemy approach also predicts that there is real ambiguity between a reflexive and a passive construction. For example, for a construction as in (11), we predict an ambiguity between a passive interpretation in which there is an unknown agent (11a) and a reflexive interpretation under which Maria is both the agent and the theme (11b):

- (11)

- I Maria vaftike.the Maria paint.Nact.pst.3sg

- a.

- .. &&

- b.

- . & =

This analysis differs from the analysis in [53], followed also in [2], under which naturally reflexive verbs have a passive interpretation as in (11a) and due to their lexical meaning (i.e., grooming verbs, etc.), they pragmatically acquire a reflexive interpretation. Crucially, this possibility is only available in the medio-passive and not the English passive for which it has been claimed that there is obligatory disjointness between the agent and the theme in passives. The conjunction test presents a potential diagnostic to differentiate between an underpspecification analysis and an allosemy analysis that we adopt here. The underspecification analysis predicts that the sentence in (12) should allow both interpretations in (12a–12b) whereas under the current approach the interpretation in (12b) is not allowed due to the semantic identity requirement in ellipsis. We have a strong preference for the passive interpretation for both conjuncts despite the fact that vafome ‘paint.NAct’ is most naturally interpreted as reflexive with human subjects.

- (12)

- Prota vaftike i Maria ke meta to prosopio tis.First paint.Nact.pst.3sg the Maria and then the mask her

- a.

- Somebody painted Maria and then he painted her mask.

- b.

- Maria painted herself and then somebody (possibly Maria) painted her mask.

However, given that our analysis, in line with [53] does not impose a disjointness requirement for passives, we cannot preclude the meaning (12b) questioning the validity of the diagnostic in this case. Despite lack of conclusive evidence, we follow a semantic analysis of reflexivity in light also of the reciprocal construction which is less straightforward to be analyzed in terms of pragmatic enrichment, since its syntactic properties suggest that reciprocity is part of its meaning (i.e., discontinuous reciprocals and comitative arguments) (For an alternative analysis to voice reflexives in Hebrew see also Kastner [3,56]). It is worth emphasizing that the choice between the two analyses does not affect the overall analysis in the paper, since under both analyses a requirement remains that there is a Voice head and not a designated passive head.

In the case of reciprocal constructions, it is clear that we are dealing with a semantically reciprocal interpretation with multiple subevents and at least two distinct agents. The way we have set up the meaning of Voice, in the context of a reciprocal vP in (8c), captures the main difference with analytic reciprocal constructions involving reciprocal pronouns. In verbal reciprocals, the subevents are obligatorily conceived as part of a collective superevent which is interpreted with respect to a particular time t. By contrast, analytic reciprocals can have a distributive interpretation involving different events taking place at different times (see [51,57] for a detailed discussion and diagnostics). As illustrated in (13a), the analytic reciprocal construction with the reciprocal o enas ton alo ‘each other’ is compatible in a context in which Peter hit John on Monday and John hit Peter on Tuesday. This interpretation is not possible with the verbal reciprocal in (13b), which is understood as a single superevent comprising of two subevents in which Peter hit John and John hit Peter, but as part of a collective interpretation.

- (13)

- O Janis ke o Petros htipisan o enas ton alo.the John and the Peter hit.Act.pst.3pl the one the other‘John and Peter hit each other.’

- O Janis ke o Petros htipithikan.the John and the Peter hit.Nact.pst.3pl‘John and Peter hit each other.’⇝ They fought and hit each other as part of a single supervent.

The same contrast applies with alilo-marked reciprocals as suggested by the contrast in (14). The analytic construction in (14a) is fine in a context in which the two suspects have never met or talked to each other and one accused the other to different people in a different set up. The verbal reciprocal in (14b) is not felicitous in this context and it suggests that they accuse each other in the same set up, favoring an interpretation in which the two talk to each other.

- (14)

- I dio ipopti katigorun o enas ton alo gia tin ekriksi.the two suspects accuse.Act.pst.3pl the one the other for the explosion‘The two suspects accuse each other for the explosion.’

- I dio ipopti alilokatigorunde gia tin ekriksi.the two suspects accuse.Nact.pst.3pl for the explosion‘The two suspects accuse each other for the explosion.’⇝ They accuse each other in the face of each other.

Middle reciprocals have received the least attention among the middle constructions discussed in this paper, and thus there are many open questions to be addressed. We set them aside here as they go beyond the goals of the present paper (see [50,51,57] for an extensive discussion of the properties of reciprocals as well as the attested differences in verbal reciprocals).

The last point to be discussed concerning the allosemy of Voice in (53) is the nature of change of state verbs. Under the present account, when Voice[-D] merges with a vP which encodes a change of state it will denote an identity function, thus being expletive. Thus, it is predicted that non-active change of state verbs can never have a passive interpretation [2,54]. This prediction is confirmed in some cases. For example, the majority of change of state psychological predicates cannot form an passive as illustrated in (15) [47,54,55]. However, in many cases, such as with change of state verbs such as skizo ‘tear’ in (16), it is possible to have an agentive passive [58]. Using the adverbial epitides ‘on purpose’ as a diagnostic, we notice that this is infelicitous with the middle-marked verb sigino ‘move’ in (15b), but it is felicitous with the middle-marked verb skizo in (16b).

- (15)

- ?I Maria siginise tin Ana epitides.the Maria move.Act.pst.3sg the Ana on-purpose‘Maria moved Ana on purpose.’

- i Ana siginithike apo tin Maria #epitides.the Ana move.Nact.pst.3pl by the Maria on-purpose‘Ana was moved by Maria on purpose.’

- (16)

- I Maria eskise to ptihio epitides.the Maria tear.Act.pst.3sg the degree on-purpose‘Maria tore her degree on purpose.’

- To ptihio skistike apo tin Maria epitides.the degree tear.Nact.pst.3pl by the Maria on-purpose.‘The degree was torn by Maria on purpose.’

We take the availability of the passive interpretation with the verb of skizo to be another instance of ambiguity. In particular, skizo can be a pure change of state verb or it can be interpreted as an agentive predicate similar to agentive change of state predicates such as murder (cf. Martin and Schaefer [59]). When skizo has a pure change of state interpretation with no agentivity feature, only the anticausative interpretation is possible as predicted by the present analysis. Alternatively, skizo can be conceived as an agentive verb, thus allowing a passive interpretation as in (16b). When there is an understood agent, the focus is on the manner of the process, whereas when the non-active variant is understood as a pure anticausative, the focus is on the result state (cf. [60,61,62] for the causative/anticausative with a focus on Slavic). Other verbs behaving in a similar way are the verbs katastrepho ‘destroy’, skotono ‘kill’, kovo ‘cut’, keo ‘burn’, tsalakono ‘crumble’.3 Crucially, there seems to be variation among speakers as to which change of state predicates can form a passive [2].

Under this analysis, we predict a large-scale ambiguity for many predicates which can receive a reflexive, a reciprocal, a passive or an anticausative interpretation. This is illustrated with the verb tsimbao ‘pinch’ which can have all four interpretations as shown in (17):

- (17)

- O Petros tsimbithike apo ti Marina.the Peter pinch.Nact.pst.3pl by the Marina.‘Peter was pinched by Marina.’

- O Petros tsimbithike gia na di an onirevete.the Peter pinch.Nact.pst.3pl for to see if dreams.‘Peter pinched himself to see if he dreams.’

- O Petros ke i Marina tsimbiunde oli tin ora.the Peter and the Marina pinch.Nact.pres.3pl all the time.‘Peter and Marina pinch each other all the time.’

- Tsimbithike to dahtilo mu sto agathi.pinch.Nact.pst.3pl the finger my in-the thorn.‘My finger got pinched in the thorn.’

On the other extreme, there are predicates which can only convey a reflexive or reciprocal interpretation and which necessarily appear with non-active Voice. For example, antagonizomai ‘compete’ always involves a reciprocal relation and thus it is expected that it will surface with non-active Voice interpreted as exclusively reciprocal as shown in (18):4

- (18)

- O Petros ke i Marina antagonizonde oli tin ora.the Peter and the Marina compete.Nact.pres.3pl all the time.‘Peter and Marina compete each other all the time.’

Psychological predicates encode pure change of state and thus can only form an anticausative. The following sentence with stenahorieme ‘get-sad’ can only be interpreted as anticausative as shown by the fact that epitides ‘on purpose’ is not licit [47,54,55].

- (19)

- I Ana stenahorithike apo tin Maria #epitides.the Ana got-sad.Nact.pst.3pl by the Maria on-purpose‘Ana was saddened by Maria on purpose.’

Allosemy, thus, arises in the context of vPs with different properties distinguishing at least among four different types of vPs. A reviewer raises the question regarding the difference between an allosemy and a polysemy approach. As the reviewer notices, under a polysemy approach we would expect that Voice can have multiple interpretations as the ones in (8a–8d) and if the type of predicate is not compatible with the interpretation of Voice, this combination should be ruled out. However, this is not what we notice in languages with type A syncretism. In many cases, a predicate is consistent with a reflexive or a reciprocal interpretation and yet non-active Voice with these predicates cannot yield a reflexive or a reciprocal interpretation. For example, although the verb vrizo ‘swear at’ can yield a reflexive interpretation when it combines with a reflexive pronoun as in (20a), the non-active variant as in (20b) only yields a passive interpretation. On the contrary, a verb like tsimbao ’pinch’ in (17b) can obtain a reflexive interpretation.

- (20)

- I Ana vrizei ton eafto tis.the Ana swear-at.Act.pres.3sg the self her‘Ana is sweared at herself.’

- I Ana vrizete.the Ana swear-at.Nact.pres.3sg‘Ana is sweared at.’

The contrast in (20) suggests that the properties of the predicate are critical for the interpretation of the Voice. There is more to it than compatibility with an interpretation. In the same direction, additional examples from reciprocals show that although a reciprocal interpretation is perfectly consistent with a predicate, the non-active variant cannot receive a reciprocal interpretation. For example, wash each other is fine, but the predicate pleno ‘wash’ in non-active can only have a passive or a reflexive interpretation, not a reciprocal one. Within an allosemy account, these restrictions can be accounted for assuming that certain features on the vP ‘activate’ a particular meaning for Voice. This means that certain ontological concepts become relevant for the semantic derivation.

Closely connected with allosemy are the idiosyncratic patterns with non-active Voice which are attested in all languages with type A syncretism. Within a polysemy account, we would need an independent explanation for these cases, whereas under the present analysis, idiomaticity is associated with the fact that Voice is dependent on the vP and thus combined they can give rise to idiomatic patterns.5 In Greek, there are numerous cases of idiosyncratic interpretations arising with non-active voice (see Alexiadou [68] a.o.). The verb tsimbao ‘pinch’ that we mentioned above can also have an idiosyncratic interpretation conveying that Peter fell in love with Maria. This interpretation only arises with non-active Voice without any transparent derivational connection with the original meaning of tsimbao.

- (21)

- O Petros tsimbithike me ti Marina.the Peter pinch.Nact.pst.3pl with the Marina.‘Peter fell in love with Marina.’

Deponent verbs, which are middle-marked verbs without an active-marked counterpart, can be treated as a special type of idiosyncrasy. Deponent verbs are attested in the majority of languages with type A syncretism and type B syncretism. As mentioned above, many instances of deponent verbs can be analyzed as involving a Voice[-D]. However, as emphasized by Grestenberger in [66,67], there are cases in which deponency is associated with an agent as in (22). For these cases, [44,66,67] propose an analysis according to which an agent is introduced lower than Voice, thus leading to Voice[-D].

- (22)

- I Ana ekmetaleftike ton Petro. Deponentthe Ana exploited the Peter‘Ana exploited Peter.’

This type of analysis is relevant for type B syncretism that we investigate in the next section.

4. Type B Syncretism (Antipassive + Type A syncretism) ⇝ [-D]

The type of syncretism discussed in this section involves the familiar type A syncretism plus the antipassive construction. An example of an antipassive construction is given in (23) from Halkomelem [69].6 In (23a), there is a transitive construction with a transitivizing morpheme (tr) which is obligatory. In (23b), the middle marker –əm appears and the object is demoted or it appears as an oblique argument, as indicated by the oblique marker ʔə.7

- (23)

- Niʔ qwəl-ət-əs tθə sce:ɫtən.aux bake-tr-3ergdet salmon‘He cooked/barbecued the salmon.’

- Niʔ qwəl-əm ʔə tθə sce:ɫtən.aux bake-midobldet salmon‘He cooked/barbecued the salmon.’ [69] (31b–c)

The antipassive construction, compared to the passives, reflexives and anticausatives, presents an unexplored territory as discussed in [71]. Furthermore, as [72] notes, constructions called antipassive crosslinguistically exhibit quite different properties, thus presenting further challenges for their analysis. The goal of this section is not to provide an analysis of antipassives in general. Rather, we focus on languages in which the antipassive shares the same morphology with the reflexive, anticausative and passive presenting a case of antipassive plus type A syncretism. For example, as [73] reports, in Kuku Yalanji of the Australian Aboriginal family, the morpheme -ji appears in antipassive constructions as illustrated in (24).8 In (24a), the construction is transitive, as shown by the fact that the subject appears with ergative case and the object with absolutive. In (24b), the morpheme -ji attaches to the verb and the object is expressed with locative case while the subject appears with absolutive.

- (24)

- Kuku Yalanji antipassive construction.

- Nyulu dingkar-angka minya nuka-ny.3sg.nom(a) man.erg:pt(a) meat.abs(o) eat.pst‘The man ate meat.’

- Nyulu dingkar minya-nga nuka-ji-ny.3sg.nom(s) man.abs(s) meat-loc eat-mid-pst‘The man had a good feed of meat (he wasted nothing).’ [73]: (365)

Patz et al. [73] shows that the same morpheme -ji appears in reflexives (25a–25b), in anticausatives (25c–25d), in passive (25e) or passive-like dispositional constructions (25h), i.e., a wide range of constructions participating in type A syncretism that we discussed above.

- 25

- Kuku Yalanji.

- Karrkay julurri-ji-y. Reflexive:(336)child.abs(s) wash-mid-nonpst’The child is washing itself. ’

- Bunjil yaka-n-yaka-ji-ny. Reflexive:(337)widow.abs(s) cut-n-redup-mid-pst’The widow kept cutting herself.’

- Nyulu jalbu naybu-bu yaka-ji-ny, minya3sg.nom(s) woman.abs(s) knife.inst cut-mid-pst meat-abs(o)yaka-l-yaka-nya. Anticausative:(344)cut-I-redup-sub’The woman cut herself with a knife while cutting meat. ’

- N gayu yinil-kanga-ji-ny bilngkumu-ndu. Anticausative:(354)I sg.nom(s) fear-cs-mid-pst crocodile.loc:pt’I was given a fright by the crocodile. ’

- Warru (yaburr-undu) bayka-ji-ny. Passive:(345b)yg.man.abs(s) shark-loc:pt bite-mid-pst’The young man was bitten (by a shark). ’

- lalbu-ndu jarba baka-ji-ny. Accidental Passive:(346)woman-loc:pt snake.abs(s) poke-mid-pst’The woman happened to poke a snake.’

- Nyulu maral ngulkurr nyaji-ji-y. Dispositional:(360)3sg.nom(s) girl.abs(s) good see-mid-nonpst’The girl looks nice.’ (lit. is good to look at [by anyone])

- Yanya mayi ngulkurr nuka-ji-y. Dispositional:(361)this.abs(s) food.abs(s) good eat-mid-nonpst’This food tastes nice.’ (lit. is good to eat by anyone)

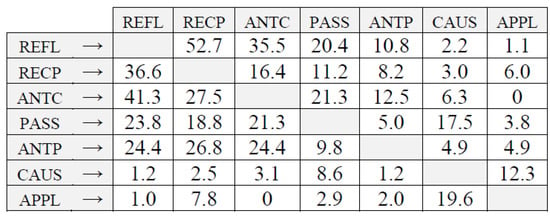

The syncretic morphology of antipassive with the morphology in type A middle syncretism is not a peculiarity of Kuku Jalanji or Halkomelem. As mentioned in the introduction, Bahrt’s typological quantitative research is illuminating in this respect. Bahrt [10] conducted a survey of syncretic Voice patterns in a language sample of 222 languages, selected based on the Genus-Macroarea sampling method. His survey shows that the probability for antipassive to be syncretic with the reflexive-anticausative is almost equivalent (and a bit higher) with the probability of passive to be syncretic with these Voices.9

The relevant probabilities for all seven Voices examined in [10] are given in Figure 1 ([10]; p.192; Table 27):

Figure 1.

Probability of language featuring simplex voice syncretism.

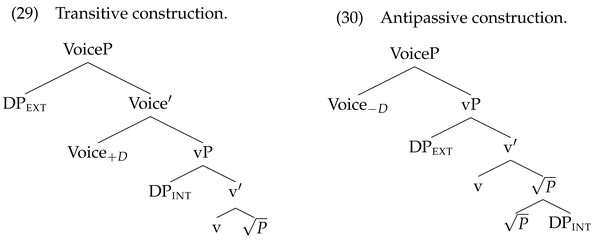

Thus, under this prism of syncretism, our main question is whether there is a unifying feature between the antipassive and the middle constructions discussed in Section 3. The difficulty lies in that, whereas middle Voice in type A syncretism appears to operate on the external argument, formalized as [-D], the antipassive seems to operate on the internal argument leaving the external argument untouched. Below, we put forth a hypothesis under which this is only epiphenomenal. We argue that both the internal and the external argument are affected in the antipassive construction. The core idea is that the internal argument is reanalyzed as an argument of the root and that the external argument is introduced lower, and not by the Voice head, thus enforcing Voice[-D] in this environment. Our analysis builds on Basilico’s insight regarding the analysis of antipassives in [5] and on Tollan’s analysis of unergatives in [74], who argues for a lower external argument, a low agent as opposed to a high agent (see also [75,76]). Moreover, it shares certain aspects with Grestenberger [67]’s analysis of deponent constructions in which there is a lower agent and Alexiadou [77]’s discussion of unergative nominalizations as involving lower agents. Basilico [5] discusses the antipassive construction in the Eskimo Aleut language family, in which there is no syncretism with other middle constructions, and suggests that in the antipassive construction, the oblique antipassive object occupies a different position than in the transitive construction. In particular, he argues that it is introduced by the root. Under this analysis, the antipassive morpheme is analyzed as a morpheme attached to the root changing its valency and turning it into a one-place predicate. The antipassive alternation in Baffin Island Inuktikut is presented at (26b), taken from [78,79]:

- (26)

- Baffin Island Inuktikut.

- a.

- Piita-up naalautiq surak-taa.Peter.erg radio.abs break.part.3sg.s/3sg.o‘Peter broke the radio.’

- b.

- Piita surak-si-juq (naalauti-mik).Peter.abs break.ap.3sg radio.obl‘Peter is breaking the radio.’ [5]: (1)

The semantic contribution of the antipassive morpheme in Baffin Island Inuktikut, according to [5], is given in (27) where it appears to directly combine with the root and inserting the internal argument:

- (27)

- surak: e [break(e)]

- surak-si: xe [break(e) & UND(e,x)] [5]: (3)

In this way, the internal argument is introduced inside the VP and not by a higher transitivizer head. This idea builds on the observation that the set of the verbs which undergo antipassivization are the so-called core transitive verbs (e.g., change of state verbs such as break, cut, destroy).10 By contrast, non-core transitives such as eat can omit their object without an antipassive morpheme (they cannot be morphologically antipassivized). In this paper, we do not discuss antipassive in the Eskimo-Aleut language family, as the syncretism observed is different from the type of syncretism we are interested in. According to [5], the same morpheme appears in anticausatives and benefactive applicatives, thus his motivation to treat the antipassive morpheme as an argument introducing head.

We follow from the analysis in [5] the idea that the internal argument in antipassives is reanalyzed as being part of the verb base. In this way, the external argument is introduced by the v-head which in transitive constructions introduces the internal argument. Thus, under this view, antipassives behave like unergatives in which the external argument is introduced by little-v according to [74,75]. The difference with the antipassives is that the verb root still requires a Voice head which is realized as an expletive Voice[-D].11 The idea of a lower agent is not new in the literature. Tollan and Oxford [75,76] argue for a group of pseudo-transitive verbs which are analyzed as having an external argument that is introduced lower in the structure, by little-v, and not from a Voice head. Laura Grestenberger explains morphology mismatches in deponent verbs as the result of the agent being introduced lower than the VoiceP [44,66]. Alexiadou capitalizes on this as an option to explain unergative nominalizations [77].

Thus, for an antipassive configuration as the example in (23b) repeated in (28) from Halkomelem, we propose the configuration in (30). The crucial difference from a transitive construction, as in (29), is that the external argument is introduced lower, which we call a low-agent argument (pace Tollan [74]). Voice[-D] merges to satisfy the requirement of the root for Voice. Under this view, in this environment, Voice will be expletive; thus, it will return an identity function as shown in (31).

- (28)

- Niʔ qwəl-əm ʔə tθə sce:ɫtən.aux bake-midobldet salmon‘He cooked/barbecued the salmon.’

- (31)

- Voice / vP=

Under this analysis of antipassives, we can explain why they share the same morphology with anticausatives, reflexives and reciprocals, and in certain cases, with passives. In all of these cases, we have a Voice[-D].

Indirect evidence for analyzing the external argument in antipassives introduced lower than Voice comes from different directions. First, causativization has been shown to be restricted in many cases to intransitive predicates (see [81] a.o.). Tollan and Oxford [75] notices this restriction for Algonquian languages and they interpret the intransitivity restriction as an indication for the lack of VoiceP, in the sense of lacking an external argument. Alternatively, under a theory of expletive Voice, we could reformulate the intransitivity restriction in certain languages as a restriction in the absence of an external argument introduced by Voice.12 This is our explanation for the licensing of causativization in Halkomelem. As [69] points out, the antipassive is compatible with causativization as shown in (32b). By contrast, the transitive version with the transitivizer -ət is ungrammatical under the causative marker -stəxw as in (32a). Notice that the two constructions appear to be the same otherwise. Under the current analysis of the -əm antipassive, causativization is licensed because the external argument is introduced lower than Voice. A caus-head can appear in the context of a specifierless Voice head but not above a fully-fledged VoiceP with an external argument.13

- (32)

- *Niʔ cən qwəl-ət-stəxw (ʔə) tθə sce:ɫtən.aux1.sub bake-tr-csobldet salmon‘I made him cook/barbeque the salmon.’

- Niʔ cən qwəl-əm-stəxw ʔə tθə sce:ɫtən.aux1.sub bake-mid-cs obldet salmon‘I made him cook/barbeque the salmon.’ [69]: (33–34)

The present hypothesis, under which certain antipassives involve a lower external argument, is linked indirectly with the observation that antipassives are associated with imperfective semantics. As [71] puts it, the observation is that if an antipassive construction can have a perfective (telic) interpretation, it must also have an imperfective (non-telic) interpretation (Polinsky [71]; 20). Rebecca Tollan in [74] indicates that the distinction between high and low agents is relevant for telicity. In particular, she argues that whereas both types of agents initiate an event, high agents are associated with the completion of the event, whereas low agents do not obligatorily bring about a change of state (Tollan [74]; 20). Tollan herself acknowledges that it is not a necessary condition that lower agents are associated with atelic events but it is rather a tendency. Her observations correlate nicely with the observation that antipassives crosslinguistically show a tendency for atelic interpretations but not necessarily. In the case of the Halkomelem antipassive with the middle marker -əm, things are not clear since, according to [69], the -əm antipassive appears to be compatible both with imperfective and perfective aspect.14 Given that atelicity is not a necessary condition for either the low-agent hypothesis or antipassive constructions, we cannot make a strong claim based on the data. At this point we can only notice that the correlation of antipassives with atelicity is supportive of their analysis as involving a low-agent.

Additional evidence for the low agent in antipassives comes from observations in other languages, regarding the character of antipassive subjects. For example, Austin [83] offers some crucial data from a geographically and genetically unrelated language, Diyari, an Australian Aboriginal language. In [83] it is noticed that when the antipassive tharri morpheme is inserted, the predicate conveys that the action is accidental not purposeful. This is illustrated in (33). The transitive construction in (33a) indicates that finding involves purposeful search, whereas the antipassive in (33b) conveys that the finding was accidental.

- (33)

- Ngathu yinanha danka-rna wara-yi.1sg.erg2sg.acc find-prtcaux-pres‘I found you (I was looking for you and I found you).’

- Nganhi danka-tharri-rna wara-yi yingkangu.1sg.nom find-ap-prtc aux-pres2sg.loc‘I found you (accidentally).’ [83] (352–353)

Volitionality is a property associated with high agents according to [74] and not with low agents, something which seems to be replicated in the contrast between the transitive and the antipassive construction in (33a) and (33b), respectively. Of course, as we said, our analysis concerns antipassives which also participate in type A syncretism, but it remains to be seen whether a more general claim can be made for low agency and antipassives crosslinguistically.

These observations converge to the hypothesis that, at least in some cases, the antipassive construction is associated with the introduction of a lower external argument lacking certain high-agent role properties. The presence of a lower external argument enforces a Voice[-D] to satisfy the requirement of the root.

The analysis of the -əm morpheme in Halkomelem, as an exponent of Voice[-D], also provides a way to account for other constructions which are not the typical middle constructions that we mentioned in the previous section.15 Gerdts and Hukari [69] argue that -əm is a middle marker based on its distribution and the relevant typological work on middle type languages; however, the question is whether it can be treated as an exponent of Voice[-D]. First, they present verbs which appear with the suffix -əm without obviously being associated with a particular function. For example, the verbs in (34) obligatorily appear with the suffix -əm.

- 34

- nəqəm ‘growl’

- hesəm ‘sneeze’

- taqəm ‘cough’

- hetəəm ‘breath’

- qewəəm ‘rest’

- qəwəm ‘kneel’

- lewsəm ‘rest’

They also report, in [69], that the -əm-suffix is often used to derive verbs from nouns (e.g., kəpú ‘coat’ →kəpúʔəm ‘put on one’s coat’, qəwət ‘drum.n’ →qəwətəm ‘drum.v’). Moreover, change of state verbs are derived from adjectives with the suffix -əm (e.g., ʔiyəs ‘happy’ →ʔiyəsəm ‘get happier’ or it can attach to other verbs without any change in the argument structure (e.g., ʔitət ‘sleep’ → ʔitətəm ‘get sleepy’). As Gerdts and Hukari explain in [84], in Salish languages, and more particular in Halkomelem, the inchoative form is morphologically unmarked, with the causative being marked with a transitivizer. However, they mention eight inchoative verbs which are derived with the middle suffix -əm (e.g., təyqəm ‘move’, qiɫxəm ‘slide’, yiqəm ‘fall, tip over’, see [84]; 13).16 As [69] notice, many of these patterns are typical patterns for the middle-type languages we discussed above.

Unlike middle-type languages (such as Greek, Russian, etc.), simple reflexives in Halkomelem have a designated morpheme, -θət, and thus they do not appear with the -əm suffix.17 In [69] two different types of reflexives with the -əm suffix are reported. The first one resembles what is often referred to as the pragmatic antipassive in Russian [87]. In particular, the object is lexicalized on the verb and the middle suffix is added to express reflexive possession. This construction is particularly common especially with objects usually expressing body parts or clothing, in order to express a reflexive action, i.e., wash my feet as in (35b). Example (35a) shows that the canonical reflexive morpheme -θət is ungrammatical in this construction. The middle -əm suffix makes the sentence grammatical in (35b).

- (35)

- *Niʔ cən tθəxw-šé-θət.aux1.sub wash-foot-refIntended: I washed my feet.

- Niʔ cən tθəxw-šé-əm.aux1.sub wash-foot-mid‘I washed my feet.’ [69] (14a–b)

Crucially, according to [69], this construction is derivative of an external possession construction in which the notional possessor is the object of the clause (see also [86]). When the possessor is distinct from the agent, it is realized as the syntactic object as illustrated in (36):

- (36)

- Niʔ tši-ʔqw-t-əs ɫə sɫeniʔ kwθə sqwəméy.aux comb-hair-tr-3ergdet woman det dog‘The woman combed the dog.’ [69] (12)

Thus, the fact that the middle -əm appears in this construction suggests that a reflexivization strategy applies similar to the reflexivization in type A languages, in which the agent is identified with the possessor and a Voice[-D] appears.

The second reflexive construction which involves the -əm morpheme is described as logophoric. This is a benefactive reflexive construction in which the benefactor is obligatorily understood to be the speaker and the agent is either the speaker or the addressee. Gerdts and Hukari observe that the most common construction is the imperative as in (37a), but it can also be a 2nd person question (37b) or 1st person statement (37c).

- 37

- Nem č ʔiləq-əɫc-əm ʔə kw səplíl.Go you buy-ben-midobldet bread‘Go buy some bread for me/*yourself/*him!’

- Niʔ ʔə č kwən-əɫc-əm ʔə kw təməɫ?auxq2.sub get-ben-midobldet money‘Did you get me some money?’

- Niʔ cən qwəl-əɫc-əmaux1.sub cook-ben-mid‘I cooked it for myself.’ [69]: (22, 24, 26)

Crucially, the subject of the clause cannot be 3rd person unless it is the indirect argument of a tell verb, as shown below. In (38), the external argument of the embedded clause is understood as the addressee of tell, i.e., the woman.

- (38)

- Cse-t cən ceʔ ɫə sɫeniʔ ʔəẃ qwəl-əɫc-əm-əs ʔə kwθə sce:ɫtən.tell-tr1.subfutdet woman link cook-ben-mid-3subobldet salmon‘I’m telling the woman to cook the salmon for me.’ [69]: (27)

Thus, logophoric reflexives in Halkomelem seem to present a case in which two thematic participants are defined via logophoric agreement. Of course, the details of the construction remain to be further explored but the crucial observation is that the external argument is not filled by a DP but is rather derived via a mechanism of logophoric agreement on Voice which still remains to be understood. We conjecture that Voice[-D] occurs in a logophoric benefactive construction preventing the introduction of an argument which would block logophoric agreement for the benefactor. To our knowledge, this pattern has not been analyzed as Voice[-D] and it remains to be seen if similar patterns occur in other type A/B syncretic languages and if they can receive an analysis along the lines presented here.

Regarding transitivity, Gerdts and Hukari point out that it is difficult to detect whether the construction is transitive or intransitive. However, they notice that the compatibility of the logophoric reflexive construction with the control reflexive suffix -namət, as shown in (39), indicates that logophoric reflexives have an intransitive-like behavior. The control suffix -namət takes intransitive verbs and means ‘manage to’.

- (39)

- Niʔ ʔə č kwən-əɫc-əm námət?auxq2.sub get-ben-midlc.ref‘Did you manage to get it for me?’ [69]: (29)

Finally, the -əm suffix also appears in passive constructions as exemplified in (40). The transitive construction in (40a) is passivized in (40b) in which the agent man is demoted and appears with oblique case (cf. [88]).18

- (40)

- Niʔ pas-ət-əs tθə swayqəʔ tθə speʔəθ.aux hit-tr.3sg.ergdet man det bear.‘The man hit the bear (with a thrown object).’

- Niʔ pas-ət-əm ʔə tθə swayqəʔ tθə speʔəθ.aux hit-tr.3sg.midobldet man det bear.‘The man hit the bear; the bear was hit by the man.’

Although we think there is a lot more to say about the -əm-constructions in Halkomelem, we take the distribution of this morpheme in passive and reflexive constructions to provide evidence in favor of analyzing it uniformly as Voice[-D].

For the rest of this section, we turn our attention to antipassive constructions in Russian, which is considered one of the typical examples of type A syncretism. In Russian, the morpheme -sja appears in all constructions that we presented in the previous section as instantiating type A syncretism (i.e., reflexives, reciprocals, anticausatives, passives and the feel-like construction). Importantly, in addition to these constructions, the morpheme -sja has been argued to participate in antipassive constructions.

According to [89], Russian has three types of antipassive constructions. The first one, and probably the most widely discussed, is the construction in (41) which has a generic/dispositional interpretation, i.e., it refers to the ability/disposition of a dog to bite. As [89] mentions, this type of antipassive is restricted to verbs which usually express ‘aggressive physical behavior’ (e.g., bodat’(sja) ‘to butt’, ljagat’(sja) ‘to kick (about a horse)’ etc) [Say [89]; 427]

- (41)

- Sobaka kusaet-sja.dog bite.3sg-sja‘The dog bites (is a biter).’

This type of antipassive can be accommodated under the present analysis of antipassive as involving a lower external argument, since in these cases the predicate is understood as a disposition and the external argument as more of a state holder than a volitional agent. That is, we take it that the so called antipassive in Slavic languages attested in Russian, Slovene, Czech, Polish and also Latvian and Lithuanian (see [72]) involves a low agent in the sense of [74] which is introduced at Spec, vP. Under this configuration, an expletive Voice head, as in (31), merges to satisfy the requirements of the root deriving a structure as the one we presented in (30). In this way, we are able to explain why the same morpheme -sja appears in the so-called middle constructions and in the antipassive, since in all contexts it realizes a [-D] exponent of Voice (cf. [90]).

The other two -sja constructions, which are discussed below, have been termed antipassives but as we show they should not be considered true antipassives, but rather a special type of reflexive constructions (see also the discussion in [91]). The reason why we discuss them in the end of this section is because their characterization as antipassives is illuminating for the ways in which the term antipassive has been associated with reflexive constructions. Moreover, the availability of these reflexive constructions with an antipassive make-up, not only in Russian but marginally in Greek as well, instantiates the flexibility of Voice [-D] to appear in different environments and give rise to different interpretations.

Say in [89] classifies as antipassives the predicates in (42) in which the understood object, which cannot be overt, expresses inalienable possession. These cases can be reduced to reflexivization (via the part–whole relation) as in (42). For example, the pattern in (42a–42b) is also possible to be understood in this way in many languages of type A syncretism, including Greek.

- (42)

- umyt’sja ‘wash my face’.

- sosredotočit’sja ‘to concentrate’.

- naxmurit’sja ‘to knit one’s brow, to frown’ (cf. naxmurit’ ‘to knit’).

- vysmorkat’sja ‘to blow one’s nose’ (cf. vysmorkat’ ‘to blow’).

Interestingly, however, the extent to which certain predicates can be understood as being reflexive differs crosslinguistically. The following -sja forms in (43) are classified as lexical antipassivization by [87,89] and they also involve an understood possessive internal argument.

- (43)

- stroit’sja ‘build a living place for oneself, an edifice for living’.

- tratit’sja ‘to spend ones money’.

- propit’sja ‘to drink away everything one possesses’.

- pečatat’sja ‘to have one’s works published (in...)’.

- zapravit’sja ‘to refuel one’s vehicle’.

In other cases, the understood object depends on the context but, crucially, it is always possible to derive a possessive relation between the understood object and the subject. For example, in (44a), Say describes a context in which the saleswoman points at the package when uttering the sentence. For (44b), the context described is a currency exchange office where the security guard addresses a customer, so the understood object is his money. In (44c), the understood object is laundry since the discussion is around a washing machine.

- (44)

- Vy tam sami zavernëte-s’?you there alone wrap.2pl-sja‘Will you wrap-sja yourself?’ (i.e., wrap the package)

- Vy čto, obmenjat’-sja?you.2pl what change.2pl-sja‘Is it to change-sja that you have come?’ (i.e., change money)

- Ja budu stirat’sja potom.I will launder-sja later‘I will launder-sja later.’ (i.e launder clothes)

Interestingly, this type of construction seems to be also marginally represented in Greek with non-active morphology. The sentence in (45a) indicates that Peter spends a lot of his money. The sentence in (45b) can be uttered towards two persons dressed well and well-tidied who have left their stuff here and there.

- (45)

- O Petros ksodevete poli.the Peter spend.nact.pres.3sg much‘Peter spends a lot of his money.’

- Simazeftite!tidy.nact.imp.2pl‘Tidy up your stuff.’

To our knowledge, these patterns have not been discussed for Greek. One can construct more marginal examples such as fularistite interpreted as ‘fill up your cars/vehicles’ which, although they are considered marginal, are perfectly understandable in the right context. These possibilities highlight the flexibility of Voice in the derived interpretations. It becomes clear, also from the data in Greek, that this type of construction should be treated differently than antipassivization, as a reflexivization process which needs to be further examined. However, the important component for our analysis is that all constructions despite their differences involve Voice[-D]. In the following section, we discuss a different type of Voice syncretism.

5. Type C Syncretism (Anticausative, Passive + Causative)

The last type of syncretism that we discuss is type C Syncretism, attested in Korean and many Tungusic languages [7,8,9,32,92,93,94,95,96]. In type C syncretism, the same morphology appears in causative, anticausative and passive constructions. This type of syncretism is less common than type A and B syncretism. According to [10], the probability of causative and anticausative constructions to share the same morphology is very low, 3.1 and 8.6 for passive constructions (see Figure 1).19 Type C syncretism presents special interest exactly because of its rarity, since, as we will see, it is very difficult to define the unifying feature of Voice in causative, anticausative and passive constructions. The discussion in this section focuses on Korean which is one of the most discussed cases of this type of syncretism.

As has long been observed, in Korean there is a single morpheme with four lexically/phonologically conditioned allomorphs (-i, -hi, -li, -ki), glossed as -I-, used in anticausative (46a), causative (46b), passive (46c) and adversity passive constructions (46d) [7,8,9,94,96,97].

- (46)

- Mwun-i cecello yel-li-ess-ta. Anticausative ([7]; 71)door.nom all-by-itself open-I-.past.dec‘The door opened all by itself.’

- Alice-ga mul-ul eol-li-eoss-da. Causative ([6]; 3)Alice.nom water.nom freeze-I-past.dec.‘Alice froze the (glass of) water.’

- Mia-ka Inho-hanthey cap-hi-ess-ta. Passive ([7]; 71)Mia.nom Inho.dat catch-I-.past.dec‘Mia was caught by Inho’

- Minswu-ka kay-eykey tali-lul mul-li-ess-ta Advers-Pass ([8]; 488)Minsu.nom dog.dat leg.acc bite-I-past.dec‘Minsu got bitten his leg by a dog.’

The first thing to notice about this type of syncretism is that if we were to treat the -I- marker as realization of Voice, this cannot be modeled simply as [+/−D]. The morpheme -I- seems to be obligatory whenever a causer argument, which is otherwise not required by the root, is added, or whenever an external argument is demoted. Assuming that -I- appears when Voice is underspecified would not help either because a null exponent is also available in [+/−D] environments. It is also not possible to reduce -I- to causative semantics, because the same marker appears in passive and adversity passive constructions.

Jeong in [6] addresses the issue of syncretism between causative and anticausative constructions in Korean. Her analysis is interesting because it is based on a different analysis of Voice as indicating that a construction is marked in some sense. Thus, according to [6], the morpheme -I- is an exponent of marked Voice. This is quite different from the [+/−D] specification that we have seen so far across the different Voice systems. In addition, it raises the question as to what counts as a marked construction. Below, we outline Jeong’s line of argumentation.

First, as [6] notes, in contrast with languages exhibiting type A and type B Syncretism, in Korean the vast majority of predicates which participate in the causative–inchoative alternation are obligatorily divided into two classes: (i) class-I, verbs with an unmarked causative and a marked causative (0-causative and -I-anticausative, following Jeong’s terms) and (ii) verbs with a marked causative and an unmarked anticausative (-I-causative and 0-anticausative). In other words, unlike in other languages (e.g., Russian, Greek, English, Chukchi), there are very few labile verbs which are both 0-marked (e.g., mumchu-da ‘stop’, is given by Jeong [6] as a labile verb) or, alternatively, verbs in which both versions are marked. The two types of predicates are given in (47–48), from [6]. In (47), the verb yeol- ‘open’ requires overt marking in its anticausative form (47b), whereas the verb eol- ‘freeze’ requires overt marking to form a causative variant. Notice that in Greek (and likewise in English) both variants are labile, i.e., they alternate without any marking.

- (47)

- 0-causative, I-inchoative.

- a.

- Alice-ga moon-ul yeol-eoss-da.Alice.nom door.dat open.past.dec‘Alice opened the door.’

- b.

- Moon-i yeol-li-eoss-da.door.nom open-I-.past-dec‘The door opened.’

- (48)

- 0-inchoative, I-causative.

- a.

- Hosu-ga eol-eoss-da.lake.nom freeze-past.decThe lake froze.

- b.

- Alice-ga mul-ul eol-li-eoss-da.Alice.nom water.acc freeze-I-past.dec‘Alice froze the (glass of) water.’

Jeong takes as a baseline [32,98]’s list of verbs crosslinguistically divided into internally caused (e.g., bloom) vs. externally caused (e.g., explode) and shows that, in Korean, most verbs that are characterized as internally caused form I-causatives, whereas externally caused verbs form I-anticausatives, (cf. Alexiadou [99]). She provides a unified analysis of causatives and anticausatives based on the idea that the main function of the suffix -I- is to reverse the lexically specified canonical property of the verb stem (Jeong [6]; 7), offering two alternatives. Under the first type of analysis, -I- is an exponent of Voice. It attaches to the vP and its function is to return the set of events that are marked (i.e., if it attaches to an internally caused base by default (e.g., freeze), it will return the externally caused set of events, and if it attaches to an externally caused base by default (e.g., open), it will return the set of internally caused events). Under this analysis, -I- is analyzed as affecting the set complementation operation (C).

- (49)

- -I-() ==B - where X denotes a set of canonical events associated with the vP and B is the domain of all possible events associated with the vP. [6]; 3

Jeong points out an apparent problem with this analysis, namely that the verb base should denote the set of all possible events in order for this analysis to work, and -I- suffixation should lead to pick out the ’non-canonical’ marked patterns. She modifies the analysis to treat -I- as picking out the set of events that are non-canonical given the properties of the root.

In our terms, what is important is the markedness effect that the Voice morpheme -I- has in Korean, something that is different from Voice[-D] that we discussed above. This becomes evident by the fact that, in type A and type B languages, the causative—anticausative alternation need not be morphologically marked for a variety of predicates which are difficult to classify as externally or internally caused (for example, both freeze and open are labile verbs in Greek, see [2] for a discussion on this). We take this markedness effect to be a basic ingredient of the Korean Voice system, but the way to define this markedness feature remains open. Even if we try to further elaborate Jeong [6]’s account, the causative—anticausative alternation, her analysis cannot be extended to passive constructions which also have the same morphology.

Crucially, the passive construction in Korean exhibits different restrictions from the formation of passive in languages with Voice[-D] that we presented above. In Korean, passivization is subject to an animacy/hierarchical constraint [9,100,101]. As [9] puts it, when there are two arguments, the one that has control (usually the animate argument) tends to be the subject. Thus, while both variants are fine in (50), in which both the external and the internal arguments are animate, in (51), in which the internal argument is inanimate (ball), passivization is not licensed as shown by the ungrammaticality of (51b).

- (50)

- Kyengchal-i totwuk-ul cap-ass-ta.policeman.nom thief.acc catch.past.dec‘The policeman caught the thief.’

- Totwuk-i kyengchal-eykey cap-hi-ess-ta.thief.nom policeman-by catch-I-.past.dec‘The thief was caught by the policeman.’ [9];(21)

- (51)

- Namca-ka kong-ul ccoch-nun-ta.man.nom ball.acc chase.past.dec‘The man is chasing the ball.’

- *Kong-i namca-eykey ccoch-ki-n-ta.ball.nom man-by chase-I-.past.dec‘The ball is chased by the man.’ [9];(23)

In addition, the same morpheme -I- appears in adversative passive, in which the subject is the understood affectee of the passive construction, as illustrated in (52):

- (52)

- Yongswu-ka Swuni-eykey os/somay-lul cap-hi-ess-ta.Yongsu.nom Swuni.dat clothes/sleeve.acc hold-I-.past.dec‘Yongsu had his clothes/sleeve grabbed by Suni.’

- John-i Mary-eykey sinpal-ul palp-hi-ess-ta.John.nom Mary.dat shoe.acc step-on-I-.past.dec‘John had his shoe stepped on by Mary.’ [9]; (34)

Both in the case of passive and in the case of the adversative passive, we cannot extend Jeong [6]’s analysis of the causative—anticausative alternation presented above. However, in all cases that we have discussed so far, there is a common pattern; an argument that is otherwise not salient in the structure is ‘promoted’ to become the subject of the construction. In an internally caused predicate, the causer is not salient; by having -I-Voice, a causer argument is introduced at the Voice level. In externally caused predicates, the salient argument is the causer and the internal argument is not salient. By having -I-Voice, the external causer is demoted and the internal argument becomes salient by becoming the subject of the clause. Similarly, in the case of passive and adversative passive. The animacy/hierarchy restrictions in passives can be taken as additional evidence that Voice is related to a saliency feature. However, it appears to be difficult to define the properties of this feature. Further research in Korean -I-constructions is required in order to further develop this insight into a formal hypothesis. A possibility would be following Nie [82]’s proposal, to define Voice in terms of multiple features, i.e., a [+/−D] feature and a or a different feature in addition. In this case, we could model the -I- morpheme as an instance of a [+D] feature and a salience feature, which needs to be further defined. This would mean that Voice in Korean would always require a specifier which can be either externally merged, i.e., in causatives, or internally merged as in the case of anticausatives and passives. If this line of thought is in the right direction, then we can treat Voice uniformly and define the different interpretations depending on the environment it appears in.

In (53a) and (53b), we present the meaning of Voice in the causative and anticausative construction, respectively. We follow the idea from the previous section that all change of state verbs involve a cause event. However, the difference in Korean is that the notion of internal vs. external causation is important for the grammar (pace Jeong [6]) while it is not in type A and type B languages that we presented above. Thus, when a change of state of verb is classified as internally caused, the Voice[-I-] has the function of introducing an external causer. When the verb is defined as externally caused, Voice[-I-] has an expletive function, similar to what we argued for marked anticausatives in type A and type B syncretism. Assuming an expletive semantics patterns with the observation in [6] that the marked and unmarked anticausatives in Korean exhibit the same syntactic behavior. In this we also follow [8], who, building on the analysis in [35], argues that marked anticausatives in Korean have Voice while 0-marked anticausatives lack Voice. Despite this difference in their syntax, their formal interpretation is identical due to the expletive character of Voice (cf. Alexiadou [99]).

For the passive construction, Voice[-I-] has the function of introducing an existentially bound agent, thus preventing a DP to externally merge in this position. The restrictions on the Korean passive that are not attested in type A languages should be associated with the saliency feature of Voice, whose nature and exact role is still to be explained.

- (53)

- Voice / vP=&

- Voice / vP=

- Voice / vP=. &=x

For adversative passives, we argue, following [100], that in Korean they can be analyzed as a subcase of the passive construction, with the affectedness interpretation being derived as a conventional implicature. Oshima notices in [100] that in Korean the subject needs to be in inalienable or pragmatically tight possessive relation with the object. Additionally, the adversative passive interpretation is primarily available with verbs compatible with a malefactive interpretation. These are also the cases in which an ambiguity can arise between a causative reflexive construction and an adversative passive construction. In (54), the ambiguity is attributed to the negative interpretation of grab [100].

- (54)

- Inho-ka Mina-eykey son-ul cap-hi-ess-ta. Relfexive causativeInho.nom Mina.dat hand.acc grab-I-.past.ind‘Inho made Mina grab his(/??her/??his) hand.’

- Inho-ka Mina-eykey son-ul cap-hi-ess-ta. Adversative passiveInho.nom Mina.dat hand.acc grab-I-.past.ind‘Inho had his hand grabbed by Mina.’ [100]: (53a)

Finally, a note is necessary on causativization. We have discussed only change of state verbs which are causativized in the presence of Voice[-I-]. However, -I-causativization is also possible with transitive predicates which have an external argument as shown by the causativation of the predicate read in (55).

- (55)

- Emma-ka ai-eykey chayk-lul ilk-hi-ess-ta.mother.nom child.dat book.acc read-I-.past.det‘Mother made the child read the book.’ [8]: 488

The question arising is whether, in this case, the -I-morpheme is a Voice morpheme or if it is necessary to assume that it merges above Voice (cf. Nie [82]). In the domain of causatives, various tests have been proposed to distinguish between causatives involving a Voice head below Caus and causatives which only consist of a VoiceP [8,96,102,103,104,105,106,107,108]. Kim in [8] shows for Korean that -I- marked causatives and adversity passives involve a single VoiceP as opposed to analytic/periphrastic causatives.20 Under this view, the embedded external argument should be treated as a lower agent along the lines of the analysis in [75,76]. Evidence for this comes from the fact that agentive expressions (e.g., on purpose) cannot modify the embedded predicate in -I- causatives, as illustrated below:

- (56)

- Swuni-ka Minswu-eykey chayk-lul ppali/*ilpule ilk-hi-ess-taSuni.nom Minsu.dat book.acc quickly/on-purpose read-I-past.dec‘Suni caused [Minsu read the book quickly/*on purpose].’ [8]: (28a)

The binding facts in Korean converge to the same conclusion. The reflexive pronoun caki ‘self’ requires a semantic subject antecedent (Shibatani, 1973). Crucially, in -I-causatives, only the causer can serve as an antecedent. The pronoun caki cannot be bound by the subject the girl of read as illustrated for the I-causative in (1) (Kim [8], p. 502). By contrast, in the analytic causative construction in (2), the embedded subject the girl can bind the pronoun caki, suggesting that the status of the subject in the two constructions is different.

- (57)

- Kimssi-ka ku sonye-eykey caki-uy chayk-lul ilk-hi-ess-taKim.nom the girl.dat self.gen book.acc read-I-.past.dec‘Mr Kim had the girl read his/*her book.’

- Kimssi-nun ku sonye-eykey caki-uy chayk-lul ilk-key.ha-ess-taKim.top the girl.dat self.gen book.acc read-I-.past.dec‘Mr Kim1 had the girl read his/her book.’ [8]: (35–36)

Further evidence in favor of analyzing all instances of the -I- morpheme as Voice comes from the fact that it is not possible to make a morphological -I-causative out of a passive or a morphological -I-passive out of a causative [9,97].21 By contrast, analytic causatives and passives are completely fine on top of each other or on top of -I-causatives and passives. Examples (58a) and (58b) present a simple morphological passive and causative, respectively. In [97] it is shown that the passivized predicate cannot be causativized with the -I-morpheme (59a) but it can be causativized using the periphrastic causative (59b). (60) shows that the -I-passivization of a causativized predicate is ungrammatical (60a), whereas the periphrastic passivization is fine (60b) [97]. Crucially, an analytic over analytic passive/causative is also fine.

- (58)

- Yene-ka kom-eykey mek-hi-ess-ta.salmon.nom bear-by eat-I-.past.dec‘A salmon was eaten by a bear.’

- Mina-ka kom-eykey yene-lul mek-i-ess-ta.Mina.nom bear-by salmon.acc eat-I-.past.dec‘Mina made a bear eat salmon (i.e. Mina fed a bear with a salmon).’ [97]: (55–56)

- (59)

- Periphrastic vs. morphological causative of a passivized predicate.

- a.

- *Mina-ka yene-lul kom-eykey mek-hi-i-ess-ta.Mina.nom salmon.acc bear-by eat-I-I-.past.dec‘Mina made salmon be eaten by a bear.’

- b.