Abstract

This article proposes a redefinition of scientific authorship under conditions of algorithmic mediation. We shift the discussion from the ontological dichotomy of “tool versus author” to an operationalizable epistemology of contribution. Building on the philosophical triad of instrumentality—intervention, representation, and hermeneutics—we argue that contemporary AI systems (notably large language models, LLMs) exceed the role of a merely “mute” accelerator of procedures. They now participate in the generation of explanatory structures, the reframing of research problems, and the semantic reconfiguration of the knowledge corpus. In response, we formulate the AI-AUTHorship framework, which remains compatible with an anthropocentric legal order while recognizing and measuring AI’s cognitive participation. We introduce TraceAuth, a protocol for tracing cognitive chains of reasoning, and AIEIS (AI epistemic impact score), a metric that stratifies contributions along the axes of procedural (P), semantic (S), and generative (G) participation. The threshold between “support” and “creation” is refined through a battery of operational tests (alteration of the problem space; causal/counterfactual load; independent reproducibility without AI; interpretability and traceability). We describe authorship as distributed epistemic authorship (DEA): a network of people, artifacts, algorithms, and institutions in which AI functions as a nonsubjective node whose contribution is nonetheless auditable. The framework closes the gap between the de facto involvement of AI and de jure norms by institutionalizing a regime of “recognized participation,” wherein transparency, interpretability, and reproducibility of cognitive trajectories become conditions for acknowledging contribution, whereas human responsibility remains nonnegotiable.

1. Introduction

The rapid advance of generative artificial intelligence is reshaping the contours of scientific production, moving the question of “instrumental” use of computational means squarely into the domain of cognitive participation in the creation of scientific meaning. Whereas classical research infrastructures—from measurement devices to statistical software—have been understood as extensions of a scientist’s practical capabilities, large language models (LLMs) and their surrounding data ecosystems now embed themselves directly in the semiotic and epistemic fabric of inquiry. Currently, they propose hypotheses and sketch explanatory architectures, curate and synthesize literature, shape interim interpretations, and at times set modeling heuristics. In place of a simple human–tool dichotomy, we encounter a spectrum of roles in which AI may act as a procedural amplifier, a cognitive assistant, and, at the limit, a coagent in scientific semiosis.

Luciano Floridi’s philosophy of information offers a crucial vantage point on this shift: within the “infosphere,” informational processes do not merely serve human activity; rather, they constitute forms of social being and knowing [1]. Consequently, the evaluation of a scientific result cannot be reduced to provenance (“who produced it”) but must also analyze the informational mechanisms through which it was constructed—mechanisms whose transparency, explainability, and reproducibility are essential. This perspective points toward epistemic participation without an ontological subject: AI, while neither a legal person nor a moral agent, can contribute to knowledge production in ways that are traceable and auditable.

In parallel, science and technology studies—especially Bruno Latour’s actor–network perspective—have shown that scientific facts are stabilized within heterogeneous networks of humans and artifacts, where instruments, documents, and algorithms serve as nodes of translation and transformation [2]. For epistemology, this implies that “authorship” is less an attribute of a solitary subject than a function of a network that distributes roles, responsibilities, and means of validation. In contemporary disciplines where a significant share of work is executed within digital pipelines, AI services become constitutive elements of such networks, shaping interpretive trajectories and the very form of explanatory objects. The boundary between “instrument” and “coauthor,” therefore, ceases to be ontological and becomes a question of participation regimes and degrees of cognitive impact [3].

Research on data infrastructures reinforces this claim. In the “data-centric” paradigm vividly described by Sabina Leonelli, “data travel” through standards, platforms, and curatorial practices, and infrastructures—including algorithms—codetermine the epistemic status of results [4]. The insertion of LLMs into these trajectories makes them not external utilities but coupling links of cognition: literature filtering, heuristic summarization, and preliminary modeling, among other components where AI can exert semantic influence on the research process. At this juncture, the latent question of “AI authorship” properly becomes a question of the transparency of cognitive contribution and the methods by which it is verified.

Against this backdrop, our proposal—AI-AUTHorship, operationalized via TraceAuth and quantified by AIEIS—seeks to bridge de facto AI involvement with de jure recognition without displacing human accountability. What matters is not the ontological status of AI but the auditable structure of participation within distributed epistemic authorship.

Editorial and ethical standards have already begun to respond to this challenge. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) has updated its recommendations [5], mandating disclosure and imposing limits on the use of AI in peer review and manuscript preparation. These and similar documents (including those by COPE) simultaneously acknowledge AI’s de facto participation in the research ecosystem while preserving a de jure, anthropocentric authorship framework—thus opening a normative gap between practice and its recognition.

In parallel, major publishers—most prominently Springer Nature—have harmonized their policies: AI systems cannot be listed as authors; the generation of images by generative models is restricted; and reviewers and editors are instructed not to upload manuscripts to open AI services because of confidentiality risks [6]. At the same time, publishers are deploying AI-assisted tools to support editorial checks for compliance with ethical and integrative standards. This evidence highlights the deep institutionalization of AI at the level of processes without—yet—revising the formal rules of authorship.

The public debate intensified after early cases in which ChatGPT was named a coauthor and the ensuing editorial responses [7,8]. These episodes, despite their demonstrative nature, merely illuminate the structural problem: there are no accepted mechanisms for measuring and attributing AI’s cognitive contribution that would allow us to distinguish between “augmentation” and “creation.” At one pole lie warnings about the “stochastic eloquence” of LLMs—hallucinations, citation artifacts, and scalable biases. On the other hand, there is a persistent practical effect: accelerated knowledge synthesis and the emergence of heuristics productive for hypothesis generation. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that a new methodological linkage is needed—one that simultaneously mitigates risks and acknowledges factual contribution.

This article offers a systematic response to that challenge.

First, we develop an ontology of instrumentality that differentiates “passive” from “active” modes of instrumental participation and identifies the threshold at which AI begins to perform semantic (interpretive) and generative functions.

Second, we introduce operational mechanisms: TraceAuth, a protocol for tracing the cognitive chain of participation (from ideation through interpretation to text), and AIEIS (AI epidemic impact score), a metric of epistemic impact that assesses contributions along the axes of procedural, semantic, and generative participation.

Finally, we discuss how these mechanisms integrate with existing norms (COPE, ICMJE, and publisher policies), showing how a transparent cartography of contribution enables us not to “reinvent” authorship but to recalibrate the criteria for its recognition within a distributed cognosphere.

In theoretical terms, we shift the debate over “AI authorship” from a moral-legal register to an epistemology of contribution, characterizing AI as a cognitive agent without ontological subjecthood. Methodologically, we propose a measurable and auditable architecture that remains compatible with current norms: TraceAuth renders the process legible (who participated, where, and by what means), whereas AIEIS quantifies the effect (the extent to which AI participation reshaped the work’s explanatory structure).

Our approach does not displace anthropocentric responsibility; rather, it builds a bridge between practice and norm, enabling editors, reviewers, and authors to make well-grounded determinations about the status of AI’s contribution in specific manuscripts—from honest acknowledgment of instrumental assistance to a justified qualification of cognitive coauthorship within a regime of distributed authorship.

In summary, we reconstruct the philosophical foundations of an ontology of instrumentality and delineate the boundaries of “passive” and “active” tools; we analyze the cognitive turn and describe how AI can become a producer of meaning (hypotheses, models, interpretations), comparing its role with that of human participants (a graduate student, a colleague, and a consortium). We systematize prevailing norms and risks (COPE, ICMJE, publisher policies, and cases of ambiguity). Finally, we introduce the methodological and conceptual framework of AI-AUTHORSHIP.

The paper advances three linked claims. First, we develop an ontology of instrumentality showing why AI cannot be treated as a neutral tool but rather as a mediator that may become cognitively active under specific conditions (Section 2). Second, we propose distributed epistemic authorship (DEA) as a descriptive framework that recognizes AI as a node in epistemic networks while maintaining moral responsibility (Section 3). Third, we operationalize these insights through two design mechanisms—TraceAuth (a trace protocol) and AIEIS (an epistemic impact score)—intended for editorial and peer-review use, including proportional disclosure and enhanced verification triggers (Section 4 and Section 5).

We assume that the conceptual architectures of TraceAuth and AIEIS emerge at the intersection of several intellectual traditions concerned with the relationships among tools, knowledge, and agency. In particular, the classical philosophy of instrumentality [9,10,11] questions the presumed neutrality of tools as mere extensions of human intention. Likewise, later epistemological and sociological approaches [12,13] treat scientific instruments not as passive reflectors of knowledge but as active participants in their production.

More broadly, contemporary debates on artificial intelligence and the reproducibility of science highlight the epistemic opacity of algorithmic systems. Against this backdrop, our work proposes an ontological synthesis to identify the moment when mediation becomes cognition. The paradigms we introduce—TraceAuth and AIEIS—are conceived not as regulatory mechanisms but as operationalized forms of transition from instrumental to cognitive action, linking phenomenological philosophy, the philosophy of science, and AI ethics.

The present conceptual study relies primarily on an analytic–design approach rather than an empirical methodology. Our aim is to develop and operationalize the TraceAuth and AIEIS framework, which integrates AI participation into the epistemic logic of scientific authorship. In this sense, our analysis unfolds in three stages:

- Philosophical grounding;

- Structural formalization;

- Normative–ethical synthesis.

To avoid possible misinterpretations of the proposed approach, we consider it necessary to clarify several fundamental aspects concerning authorship, responsibility, and the practical scope of TraceAuth and AIEIS within contemporary editorial standards.

First, our work does not advocate unconditional or unequivocal recognition of artificial intelligence systems as authors of scientific publications. In line with the COPE and ICMJE recommendations, authorship remains an exclusively human category—grounded in responsibility, intentionality, and the ability to respond to scientific critique. Our approach should be interpreted as introducing a category of acknowledged participation rather than authorship, functioning as a philosophical–methodological and operational instrument. Within this framework, the proposed paradigms of TraceAuth and AIEIS are designed to document and articulate epistemic contributions without altering the legal or ethical status of authorship.

Second, TraceAuth is not a mechanism of oversight, surveillance, or administrative control. We conceptualize it as a voluntary research log intended for documenting only those epistemic steps in which a researcher consciously engages AI and deems such participation necessary to record. In this interpretation, the protocol does not imply automatic data collection, does not require exhaustive logging, and does not obligate authors to disclose routine digital or infrastructural processes (e.g., search engine operations, indexing functions, or standard editorial tools). Its purpose is to support transparency solely in cases where the researcher deliberately involves AI in the formation of hypotheses, interpretations, or models.

Third, through AIEIS, we do not seek to quantify the entire algorithmic mediating environment already deeply embedded in contemporary scientific infrastructures. Large-scale algorithmic systems used in search engines, recommendation tools, analytic platforms, and text editors operate as background layers of scientific practice. In this notation, our index applies exclusively to explicit, author-initiated semantic or generative interventions and is not designed to detect, rank, or regulate the latent influence of infrastructural algorithms.

Fourth, academic autonomy and human responsibility remain foundational principles. Our proposed architecture aims to reinforce them. Specifically, TraceAuth and AIEIS clarify the boundary between procedural assistance and cognitive intervention without undermining or redistributing responsibility. Human authors therefore remain the sole bearers of responsibility for the interpretive content of the work, irrespective of the extent of AI participation documented through TraceAuth or quantified by AIEIS.

Finally, the mechanisms we propose are fully compatible with current editorial and ethical norms, as they do not entail altering the status of authorship. In our interpretation, they perform an intermediate epistemic function: enabling more precise articulation of AI’s contribution in hybrid human–algorithmic research configurations without attributing agency or subjectivity to algorithms. We believe this distinction provides a clear demarcation between instrumental support and participation in meaning generation.

Taken together, these clarifications, in our view, accurately and appropriately delineate the ethical, practical, and epistemological boundaries of the proposed approach and confirm its compatibility with established standards of scholarly communication.

2. Structure and Operationalization

2.1. Ontology of Instrumentality: From Epistemic Mediation to Procedural Amplification

The notion of a “tool” in science is rarely neutral. Instruments and computational means do not merely accelerate the scientist’s labor; they mediate and structure the very object of inquiry, the modes by which a phenomenon becomes visible, and the forms of epistemic inference. Scientific rationality thus appears to be technically mediated: experimental “construction of the phenomenon” transforms the instrument from an auxiliary accessory into a condition of possibility for theory itself [14]. Don Ihde’s postphenomenology [15] articulates a characteristic “double move” of any instrumentality as amplification/reduction: an instrument amplifies certain aspects of a phenomenon while inevitably reducing others, thereby preconfiguring the hermeneutics of its readouts. Ian Hacking radicalizes this insight with his thesis of instrumental realism: to know is to be able to intervene [16]. What we can reliably produce and stabilize by means of instruments thereby acquires ontological robustness. From this perspective, the distinction between “theory” and “instrument” is less fundamental than the difference between regimes of intervention and interpretation.

Sociology of science deepens the picture. For Bruno Latour, scientific facts emerge within heterogeneous networks of humans and artifacts in which instruments, protocols, visualizers, databases, and algorithms operate as agents of “translation.” Peter Galison [17] articulates how “cultures of image and logic” generate distinct epistemic machines—ranging from bubble chambers to electronic detectors—and shift standards of evidentiality. Hans-Jörg Rheinberger [18] introduced the notion of experimental systems, in which instruments and specimens form a productive “coupling of indeterminacy” that yields new objects of knowledge. In the digital era, such couplings increasingly run through data infrastructures. Sabina Leonelli demonstrated how the “travel” of data across platforms, standards, and curatorial practices codetermines not only the pace but also the very shape of explanations. Taken together, these strands outline the ontological profile of instrumentality: the scientific instrument as a mediator that constructs access to the phenomenon and coparticipates in the formation of epistemic results.

Accordingly, the ontology of the instrument can be schematized as a triad: intervention, representation, and hermeneutics. In intervention, the instrument creates the conditions under which a phenomenon can manifest: it stabilizes parameters, amplifies signals, and suppresses noise. In representation, it generates signs (numbers, plots, images) that subsequently enter into reasoning. In hermeneutics, it sets the rules for reading those signs (calibration, confidence intervals, error models, assumptions). Each link bears its own norms of responsibility and criteria of reliability: reproducibility, traceability, measurement and model validity, and interpretability.

This triad is crucial for assessing contemporary computational tooling, including AI. An algorithmic pipeline (data collection/cleaning, transformations, modeling, visualization/text) is not a “backdoor” to truth; it rewrites the same three links: it intervenes (through filtering and transformations), represents (via vector features, probability distributions, compressed latent representations), and hermeneutically orients (through quality metrics, hyperparameter heuristics, and templates for interpreting results). The question “Is AI merely instrumental?” is thus always a question of epistemic mediation: what, precisely, is being amplified; what is being reduced; where the bounds of permissible intervention lie; and how interpretability is maintained.

The distinction between a “passive” and an “active” instrument is not an ontological dichotomy but an operational scale along which concrete technological configurations are arrayed. We propose four complementary criteria that mark the transition from passivity to activity:

- 1.

- Locus of goal setting:

A passive instrument executes an externally specified goal (measure, compute, visualize) within a predefined operation space. An active instrument can reframe the task: suggest an alternative problem formulation, redefine relevant variables, or reorganize the design (e.g., recommending a different class of models or heuristics without the human’s explicit enumeration).

- 2.

- Semantic Autonomy:

A passive instrument does not produce new meaning units beyond preagreed interpretations (e.g., calibrated readouts, statistical summaries). An active instrument generates candidates for explanation—hypotheses, interpretations, conceptual linkages—and thereby intervenes in the semiosis of inquiry rather than merely its mechanical execution.

- 3.

- Counterfactual Sensitivity:

A passive instrument reproduces results robustly under counterfactual variations within the specification; an active instrument displays structural sensitivity to alternative solution spaces, initiating transitions among them (e.g., proposing a change in model, metrics, or literature-selection criteria as a system-led initiative).

- 4.

- Traceability/Interpretability:

The fewer auditable traces an instrument leaves (causal rationales for steps, data sources, prompts, and versions), the closer it is to a “black box.” Recognition of “activity” requires not only influence on content but also explainability of that influence; otherwise, “activity” collapses into an artifact of eloquence.

These criteria align with classical views of the instrument as a hermeneutic mediator (Ihde), with knowledge as intervention (Hacking), with science as networked engineering of facts (Latour), and with later work on interpretability in machine learning, where explainability is a precondition of epistemic acceptability [19].

Against this backdrop, we can define with some precision the status of AI as a procedural amplifier. By this, we mean a systemically integrated means that:

- (a)

- Expands procedural capacity—speed, scale, and depth of standard operations (literature search/curation; data cleaning, aggregation, and transformation; generation of utility code; summarization and stylistic editing; construction of visualizations and reports);

- (b)

- Operates within externally framed tasks: the goal, quality criteria, and class of admissible solutions are set by the researcher and/or disciplinary norms;

- (c)

- Leave a traceable operational record (prompts, versions, parameters, sources) that enables audit and subsequent replication;

- (d)

- Does not claim autonomous introduction of new explanatory units (hypothesis-level content) without explicit human authorization and validation.

This status differentiates a procedural amplifier from a cognitive coauthor much as a scientific visualizer differs from a theory. The former contributes to the formation of epistemic artifacts (tables, figures, summaries, and codes); the latter contributes to the substantive structures of explanation. In practice, LLM systems may function as literature triagers that extract and reorganize existing claims, as generators of utility code and pipelines that accelerate routine workflows, as text rephrasers that improve readability without altering meaning, and even as ideational “echolocators” that surface possible directions without asserting their truth. In all these roles, the system remains a procedural amplifier insofar as it does not introduce new explanatory units or initiate causal constructions that reconfigure the research plan. The boundary is crossed when AI participation begins to shape the explanatory architecture itself rather than merely assisting its execution.

A crucial corrective here is the problem of LLMs’ “stochastic eloquence.” High fluency can mask the absence of warrants and create the appearance of “meaningful contribution”, where there has been only linguistic smoothing. Hence, the regime of procedural amplification requires institutional guarantees of transparency: maintaining trace logs (prompt/version histories), citing sources, employing interpretability instruments (feature attributions, exemplars, counterfactual checks), and, where substantive proposals emerge, documenting human validation. This is precisely where our proposed TraceAuth (a protocol for mapping the cognitive chain of participation) and AIEIS (a metric of AI’s epistemic impact) become apt. The former provides a cartography of operations; the latter supplies a quantitative stratification of contributions along procedural, semantic, and generative axes.

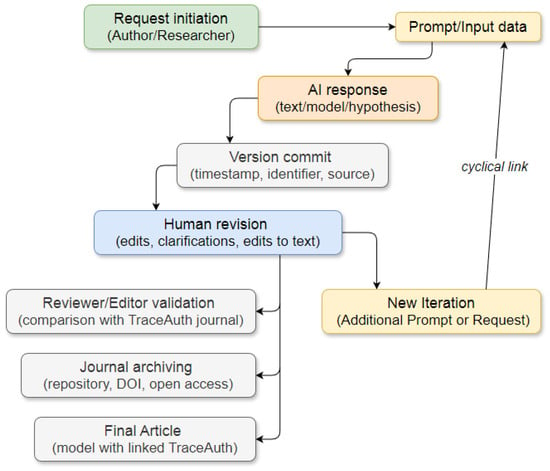

Figure 1 presents the architecture of the TraceAuth cognitive participation chain.

Figure 1.

TraceAuth: Protocol for the Cognitive Chain of Participation.

The TraceAuth flowchart (Figure 1) operationalizes a protocol for tracing the cognitive contribution of AI within a scientific workflow. Our central premise is to convert a researcher’s interaction with AI into a transparent, recorded, and auditable cognitive chain that is comparable to a laboratory notebook.

The scheme begins with query initiation: the researcher formulates a task and provides initial inputs. This is followed by interaction with the AI—the generation of an output in the form of text, a hypothesis, a model, or an interpretation. Each such output is subject to mandatory versioning with a timestamp, unique identifier, and source reference.

Next, we review a human editorial in which the researcher either revises the AI-produced result or integrates it into the main body of the work. At this point, the scheme accommodates an iterative loop: refined prompts lead to new outputs, which are again versioned and edited.

Once the work cycle is complete, the materials undergo validation, during which reviewers or editors check the consistency of the presented results against the TraceAuth record. The process concludes with archiving—for example, depositing the TraceAuth log in a repository with the possibility of obtaining a DOI and enabling open access. The end product is a finalized article or model into which the TraceAuth journal is embedded, making the cognitive trajectory reproducible.

We contend that TraceAuth is not an additional layer of bureaucracy but performs three key functions:

- Transparency. Every AI intervention is recorded along with original inputs, versions, and edits, enabling reconstruction of the cognitive evolution of the text or model.

- Institutionalization of responsibility. The scheme makes clear that AI participation is always accompanied by human editing. Responsibility is anchored at the human editorial stage, where the decision to incorporate a result into the research is made.

- Reproducibility and audit. A fixed log with timestamps and identifiers allows reviewers and auditors to reproduce interactions, verify the interpretive accuracy, and assess the warrant for the results.

Importantly, TraceAuth addresses the typical “black box” problem of generative models: in place of an opaque output, it yields a traceable cognitive sequence.

TraceAuth implements the previously defined ontological principle through verifiable records of AI participation.

Since AI models evolve and earlier versions may become unavailable, TraceAuth incorporates a mechanism for long-term reproducibility. Each journal entry includes the model identifier, hashed version, and date of use; these metadata may then be deposited in open or institutional repositories (such as Zenodo or OSF) with an assigned DOI. We believe that this ensures that auditors can reconstruct the computational context even if a model is deprecated or retired.

In particular, authors may choose to disclose prompts either fully or partially (excluding commercially sensitive components), thereby maintaining an appropriate balance between transparency and the protection of intellectual property. In this sense, we are confident that TraceAuth provides both reproducibility and temporal robustness.

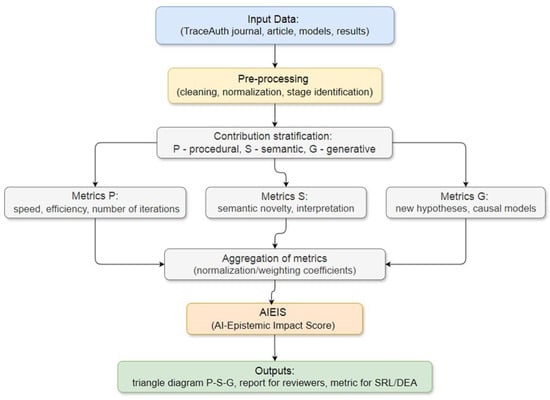

Figure 2 presents the architecture of AIEIS (AI epistemic impact score), a metric that evaluates AI contributions along the axes of procedural, semantic, and generative participation.

Figure 2.

AIEIS (AI epistemic impact score).

Figure 2 visualizes a procedure for quantitatively assessing AI’s cognitive contribution to scientific work. The core principle is a three-tier stratification of contributions: procedural (P), semantic (S), and generative (G).

The process begins with inputs: the TraceAuth log (capturing the cognitive chain of human–AI interaction), the article or model itself, and the results of experiments or computations. During preprocessing, the data are cleaned and normalized, and the stages at which AI exerts influence are identified.

The stratification stage then classifies contributions by level: P (procedural) as acceleration of computation, automation of processing, and efficiency gains; S (semantic) as data interpretation, surfacing novel meanings, and formulation of working hypotheses; and G (generative) as the construction of causal models, creation of explanatory structures, and articulation of new theoretical frames.

At the next tier, level-specific metrics are computed for each dimension—for example, the number of iterations and time savings (P), the degree of semantic novelty and originality of interpretations (S), and the incidence and substance of newly generated hypotheses and models (G).

All indicators undergo aggregation, which includes normalization and the application of discipline-sensitive weights suited to the research type and context. The output is a scalar AIEIS index (0–100) expressing the overall degree of AI’s epistemic impact.

Naturally, we fully acknowledge and accept that the tripartite taxonomy (P/S/G) is heuristic rather than exhaustive. Its advantage lies in providing a minimal, discipline-neutral coordinate system that can be expanded and reconfigured as needed. The weighting procedure is implemented through expert calibration (a Delphi-style approach), in which representatives of different scientific fields adjust the coefficients according to their epistemic traditions—from an emphasis on reproducibility to an emphasis on generative modeling.

In addition, AIEIS incorporates an “uncertainty zone” for the S+G components, capturing cases of undervalued cognitive contribution. In our view, this mechanism prevents the systematic underestimation of AI’s role at the level of meaning formation.

Finally, the system produces a set of artifacts: a ternary plot visualizing the P/S/G distribution, a reviewer-facing report, and a numeric score that can be integrated into scientific readiness frameworks (e.g., DEA (Distributed Epistemic Authorship)).

The AIEIS schema underscores that assessing AI’s cognitive contribution cannot be reduced to a binary judgment (“author/not author”) but requires a multilevel quantitative system. Unlike traditional productivity indicators (publication counts, citations), AIEIS focuses on the qualitative nature of cognitive participation.

At the procedural level (P), the emphasis is on instrumental assistance—AI as an accelerator of standard operations. At the semantic level (S), AI intervenes in interpretation, helping to formulate working hypotheses and reveal latent patterns. At the generative level (G), AI becomes a source of new models and explanatory structures, approaching the role of a cognitive coauthor.

AIEIS is designed to avoid overestimating the role of AI. If the contribution is limited to speeding up computation, the score will be high on P but low on S and G. If AI proposes new causal models, the G dimension will rise accordingly. In this way, the index captures the structure of cognitive participation, not merely its presence.

Overall, AIEIS addresses a central problem in contemporary science: distinguishing mere automation from genuine cognitive contribution. Figure 2 articulates that a credible answer is possible only through systematic stratification and quantitative assessment.

- Unified editorial rubric. Instead of vague disclosures (“AI assisted in preparing the text”), reviewers and editors receive a concrete evaluation of both the level and character of participation.

- Metascientific potential. Comparing AIEIS across articles or projects allows tracking the evolution of AI’s cognitive contribution across disciplines.

- Ethical transparency. If TraceAuth records the cognitive chain, AIEIS quantifies it—turning AI’s role into a measurable parameter open to discussion and verification.

In practice, the TraceAuth journal includes (or may include) a minimal set of fields—prompt text, model version, data source, timestamp, and editing protocol—sufficient to reconstruct every iteration of interaction between the researcher and the AI system. The AIEIS metric relies on normalized indicators (P, S, G) combined with discipline-specific weighting coefficients (α, β, γ) to ensure comparability across scientific fields.

In particular, the brief synthetic example (“AI-assisted literature review”) illustrates how TraceAuth records the sequence of interactions, whereas AIEIS assigns a final epistemic score (e.g., 68, corresponding to the upper semantic range). We believe that these clarifications authentically demonstrate the applicability and adaptability of the proposed frameworks.

Finally, the system enables the embedding of AI’s cognitive contribution into existing scientific readiness indices (SRLs) and the DEA framework, paving the way for integration into national and international research-assessment standards.

In summary, Figure 2 articulates that only through transparent stratification and quantitative fixation can AI cognitive participation be adequately appraised, preserving the balance between recognizing contribution and maintaining human responsibility.

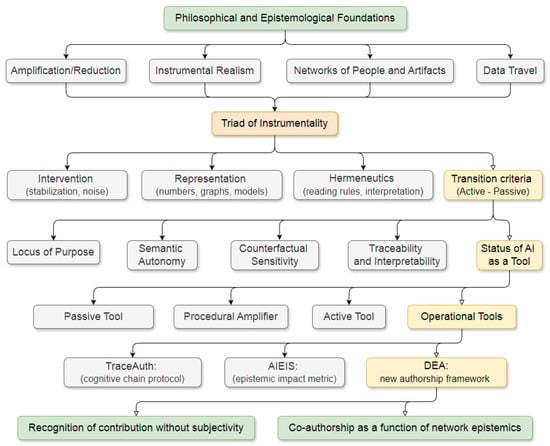

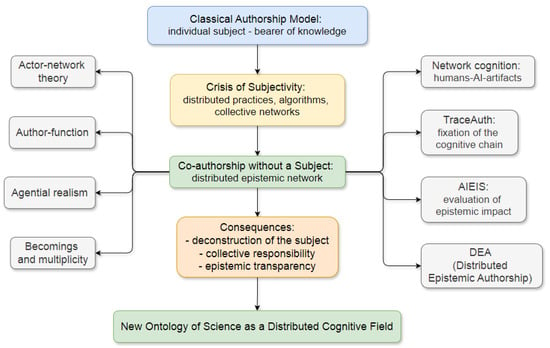

Figure 3 presents a block diagram that traces the evolution and conceptual architecture of the ontology of instrumentality in science.

Figure 3.

Logic of the ontology of instrumentality.

The block diagram is conceived as a multilayered architecture comprising the following core paradigms:

- Philosophical–epistemological foundations (Ihde, Hacking, Latour, Leonelli) establish a baseline in which the instrument is not a neutral means but a mediator that coconstitutes knowledge.

- The triad of instrumentality—intervention–representation–hermeneutics—forms the structural core: an instrument not only measures but also shapes access to phenomena, produces signs, and prescribes rules for their interpretation.

- Criteria for the transition from passive to active instruments locate the point at which AI ceases to be a “mute accelerator” and begins to intervene cognitively: goal setting, semantic autonomy, counterfactual sensitivity, and traceability.

- The status of AI as an instrument is differentiated into three categories: passive instruments, procedural amplifiers, and active instruments (cognitive coauthors).

- **Operational mechanisms—TraceAuth and AIEIS—** provide methods for tracing and quantifying AI’s cognitive contribution.

- A new authorship framework (DEA) describes distributed epistemic authorship, in which AI functions as a node in a network rather than as a subject, while its contribution is recorded and assessed.

Figure 3 traces the progressive dismantling of the false dichotomy “instrument or author.” Instrumentality does not vanish even in active mode; it is transformed:

- Philosophical grounding (Ihde, Hacking, Latour) articulates that instruments are embedded in the production of meaning rather than merely serving research.

- The epistemological triad clarifies that all knowledge is technically mediated at the levels of phenomenon disclosure, representation, and interpretation.

- The transition criteria demonstrate that “passive–active” is not an ontological split but an operational spectrum determined by the mode of intervention.

- AI status is dynamic: it may remain a procedural amplifier under strict traceability or become a cognitive agent when it generates hypotheses.

- Operational mechanisms institutionalize transparency: TraceAuth creates a journal of cognitive events, and AIEIS measures the degree of epistemic impact.

- DEA resolves the “AI authorship” problem by recognizing the networked nature of authorship: AI’s contribution is recorded, but responsibility remains with humans.

Accordingly, Figure 3 presents the ontological dynamics of instrumentality as part of a broader “cognitive turn” in science. This articulates that AI does not merely assist the researcher; it can reshape the problem space and the semantic horizons of inquiry.

Notably, Figure 3 does not depict a version-control mechanism but rather a hermeneutic feedback loop demonstrating the transition from instrumental operation to epistemic agency. The sequence “intervention—representation—hermeneutic return” illustrates how a tool, when repeatedly involved in interpretation, begins to reshape the very framework of understanding. Here, the “hermeneutic circle” functions as a model of cognitive recursion—that is, the moment when procedural execution transforms into generative reinterpretation.

TraceAuth and AIEIS operate as practical correlates of this cycle. Specifically, TraceAuth records the depth of mediation, whereas AIEIS quantitatively expresses the resulting epistemic impact. Thus, the diagram reflects not terminology but a dynamic threshold at which mediation becomes cognition.

The scheme links the philosophy of technology and the methodology of science to concrete operational mechanisms (TraceAuth, AIEIS), thereby rendering philosophical insights operationalizable. Special emphasis falls on traceability and interpretability, which mark the boundary between procedural amplification and cognitive intervention.

The DEA framework elevates the discussion to the level of distributed epistemology, aligning with the contemporary reality of science in which knowledge is produced by networks of people, algorithms, and institutions rather than by isolated individuals.

In sum, the ontology of instrumentality—so understood—dissolves the false dilemma of “either instrument or coauthor.” Instrumentality does not disappear even in active regimes; it is reconfigured as infrastructural coauthorship, where recognition is governed by traceability, interpretability, and validity of contribution. Conversely, contemporary AI can remain strictly procedural when transparent usage frameworks are maintained and epistemic functions demanding human responsibility for theoretical content are not delegated to it.

2.2. The Cognitive Turn: AI as a Producer of Meaning

The transition from an instrumental to a cognitive status for artificial intelligence (AI) in science becomes apparent wherever algorithms cease to be “mute accelerators of procedures” and begin to participate in the semiosis of inquiry—most notably in the generation of hypotheses, the construction of models, and the interpretation of results. Traditional epistemology, which distinguishes measurement, representation, and explanation, has long maintained a hard boundary between instrument and theory: instruments “deliver” data, whereas explanatory structures “belong” to humans. However, the practice of the past two decades articulates a gradual dissolution of this boundary—from machine discovery of laws (symbolic regression), through causal modeling and programmable synthesis heuristics, to generative language systems that suggest meaningful, testable, and at times unexpected lines of investigation. This, we argue, is the cognitive turn: AI becomes embedded not only in the operational but also in the explanatory contours of science.

To translate this cognitive shift into an operational form, we introduce the AI epidemic impact scale (AIEIS), a framework that enables the quantitative assessment of AI’s role in the research process. In conjunction with the TraceAuth protocol, which records the provenance of interactions, AIEIS measures cognitive impact along three axes: procedural (P), semantic (S), and generative (G). We believe this makes it possible to transform the distinction between passive and active AI participation from a purely philosophical notion into one that is measurable and reproducible.

Classical work on machine discovery of laws (e.g., Eureqa in [20]) demonstrated that symbolic regression algorithms can recover compact formulas from raw data that researchers subsequently recognize as plausible explanations. In biomedicine, the search for new antibiotics [21] offered a more “engineering” example: a trained model selected from an immense chemical space and a compound later named halicin with a nontrivial mechanism of action. While human-crafted heuristics guided the screening, the candidate itself was proposed by the algorithm, thereby setting the direction for subsequent experimental testing.

From an epistemological standpoint, the “hardest” criterion of creativity is the construction of models endowed with explanatory power. We contend that algorithms can extract analytic expressions corresponding to latent physical relationships. In a methodologically different paradigm—yet with an analogous epistemic effect—lie causal-graph approaches [22,23]. Given sufficiently rich data and appropriate assumptions, they recover oriented structures of causal relations, i.e., they build an explanatory architecture suitable for counterfactual interventions. Finally, in structural biology, AlphaFold [24] does not merely predict protein conformations; more importantly, it has reorganized the research agenda. The model functions as a provisional explanatory map from which experimental projects now proceed, including hypotheses about functions and interactions.

On the “softer” pole of cognitive contribution lies interpretation and meta-analysis, where generative language models serve as aggregators, contextualizers, and combiners of meanings. Their productivity is not a matter of what they “know” but of how they reorganize the literature, suggest alternative frames for reading empirical results, and build bridges across fragmented subfields. Here, interpretability is paramount: textual coherence and rhetorical force alone do not guarantee epistemic validity (the “stochastic eloquence” effect [25]). Recognition of AI’s interpretive contribution is possible only when explicit support is present: citation trails, verifiable sources, transformation logs, and clearly specified limits of generalization.

Juxtaposing AI with familiar human figures of scientific collaboration (the Graduate Student, the Colleague, the Consortium) helps clarify in what sense AI’s contribution may be acknowledged as cognitive without collapsing into “mere assistance.”

Graduate Student (novice researcher):

Their contribution often takes the form of “directed heuristics”: formulating working hypotheses, sketching preliminary models, and offering initial interpretations. Hallmark attributes include learnability, reflexivity, and responsibility: the student can account for decisions taken, justify methodological choices, and revise strategy in light of objections. An AI acting as a “student assistant” may emulate much of this labor (e.g., propose a reasonable spectrum of hypotheses or seed models) but lacks reflexive responsibility; its attribution must be reassigned to the human supervisor—a normative point of principle.

Colleague:

Collegiality presumes mutual recognition of competence and the exchange of critical judgments. Initiative matters: a colleague can reset goals, propose an alternative research program, and engage in substantive disputes. Contemporary AI systems exhibit limited but growing initiative (e.g., heuristic suggestions about model classes or reconfiguration of the literature base). However, such initiative is externally programmable and devoid of moral standing; accountability must be formally redirected to humans.

Consortium:

A consortium is a distributed agent that combines expertise, infrastructures, coordination rules, and verification mechanisms. Structurally, it most closely resembles the nexus of people–artifacts–algorithms–institutions, i.e., distributed epistemic authorship. In this setting, AI functions as one node—sometimes a pivotal one (as in structural biology)—but never as a substitute for the institutional tissues of responsibility and control. In other words, AI is closer to the consortium’s “laboratory machine” than to a human participant. However, in cases of high S/G (semantic/generative) contribution, it becomes a structuring element of collective intelligence.

To avoid conflating the rhetoric of a “smart instrument” with the recognition of creative contributions, an operational demarcation is needed. We propose four complementary tests compatible with editorial practice and principles of reproducibility:

- (i)

- Task–Space Shift Test.

If AI intervention merely accelerates standard procedures (searching, cleaning, coding, and rephrasing) while the problem space remains unchanged, we observe support. If the system reconfigures the space (e.g., proposes a new formulation, alternative variables, or a nontrivial model decomposition), we have creation.

- (ii)

- Causal and counterfactual load tests.

We interpret support as an improvement of the predictive “surface” and creation as the introduction of a structure apt for counterfactual reasoning (causal graphs, analytic dependencies, and mechanistic hypotheses). If the AI output can serve as a basis for “what-if” interventions, its contribution becomes explanatory.

- (iii)

- Independent reproducibility without AI.

If, after demonstration, a human can independently reconstruct the path to the result without AI, this indicates supportive status. If, by contrast, the key explanatory construction was initiated by AI and would not have arisen trivially within a reasonable timeframe under standard expertise, a case for creative contribution emerges.

- (iv)

- Interpretability and trace test.

Absent traceability (prompts, versions, sources) and explainability (local/global explanations, verifiable citations, data links), one cannot distinguish stochastic eloquence from meaning production. A deficit of explainability blocks recognition of creation, even when the output appears impressive.

These tests can be institutionalized via TraceAuth (the journal of the cognitive chain of participation) and AIEIS (the metric of epistemic impact) introduced in this work. The former records where and how AI intervenes in meaning-making; the latter grades contributions along the axes of procedural (P), semantic (S), and generative (G) participation and sets a threshold for a “coauthorship zone” when the S+G component predominates. We emphasize that even under high S/G scores, legal authorship remains human. Recognizing AI as a “producer of meaning” is an epistemological qualification, not an attribution of subjecthood.

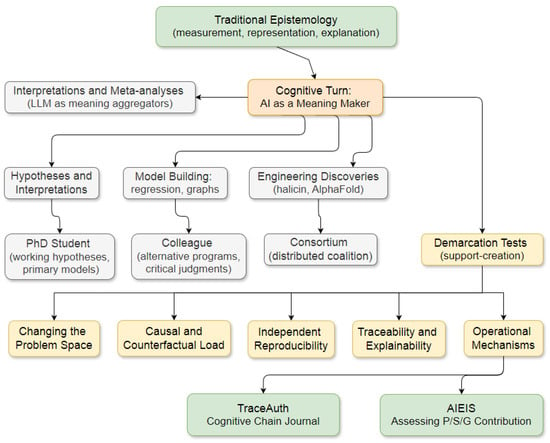

Figure 4 presents the process by which traditional epistemology (measurement, representation, explanation) transitions to a new stage—the cognitive turn—in which AI functions as a producer of meaning.

Figure 4.

Process model of the epistemological transition to the cognitive turn.

Figure 4 depicts the transition from traditional epistemology (measurement, representation, explanation) to a new stage—the cognitive turn—in which AI functions as a producer of meaning.

The center of the diagram is as follows:

- Forms of AI’s cognitive contribution: generation of hypotheses and interpretations; construction of models (symbolic regression, causal graphs); engineering discoveries (e.g., halicin, AlphaFold); interpretations and meta-analyses performed by LLMs (AI-assisted drafting tools were used under full human authorship and conceptual supervision).

- Comparators from human scientific collaboration: graduate students (working hypotheses, preliminary models), colleagues (alternative programs, critical commentary), and consortia (distributed coagency).

- Demarcation tests (the boundary between support and creation): task-space transformation; causal and counterfactual load; independent reproducibility without AI; traceability and explainability.

- Operational mechanisms: TraceAuth (a journal of the cognitive chain of participation); AIEIS (assessment of epistemic contribution along the P/S/G axes: procedural, semantic, generative).

Figure 4 underscores that the cognitive turn is not merely an expansion of instrumental capabilities but a qualitative shift in the role of AI. Unlike the classical picture, in which instruments “deliver data” and theory “belongs to” humans, AI begins to generate hypotheses, interpret results, and propose explanatory models. The comparison with the figures of graduate students, colleagues, and consortia articulates that AI can be conceived of as a cognitive participant at different levels, from an auxiliary generator of ideas to an infrastructural node of distributed authorship. The demarcation tests prevent conflation: not every display of eloquence is creative; the distinction lies where AI restructures the problem space and produces explanatory constructions. The operational mechanisms secure the contribution: TraceAuth ensures transparency of steps, whereas AIEIS quantifies the contribution and guards against overestimation.

The cognitive turn, as introduced here, makes it evident that twenty-first-century science has become a domain of hybrid meaning-making:

- Epistemology: the traditional boundary between “instrument” and “theory” is blurred. AI does not merely service inquiry; it opens new trajectories of interpretation.

- Scientific practice: Cases such as halicin and AlphaFold show that algorithms can initiate discoveries that are otherwise inaccessible within reasonable timeframes.

- Risks and challenges: Productivity comes with the danger of stochastic eloquence, where fluent text masks the absence of warrants.

- Normative framework: tests and mechanisms (TraceAuth, AIEIS) are necessary to distinguish support from creation and to keep responsibility anchored in human agents.

Thus, the cognitive turn is not a transfer of authorship to AI but rather the institutionalization of its contribution as a cognitive agent without a subject, which is consistent with distributed epistemic authorship (DEA). In this light, the cognitive turn constitutes a methodological and epistemological shift that calls for new protocols of documentation and assessment—without abrogating the anthropocentric responsibility at the core of scientific practice.

For example, in biomedical modeling, an AI system involved solely in data preprocessing would receive a high P score but low S and G scores. Conversely, a system that assists in formulating hypotheses would exhibit a substantial S component. A weighted combination of these indicators yields a normalized epistemic-impact index (0–100).

We emphasize that, in this context, AIEIS is not conceived as a rhetorical metaphor but as a formalized analytical instrument for assessing AI’s contribution to the process of meaning-making.

2.3. Precedents, Risks, and Limitations

With the rise of generative AI systems, questions about their role in scientific production have moved rapidly from laboratory practice to the center of the publishing agenda. Early attempts to list ChatGPT as a coauthor triggered a broad response from editors and professional associations. Journals suddenly faced the phenomenon of a “persuasively fluent yet unaccountable author”—an agent capable of producing convincing text while being entirely unable to bear responsibility for its content. In the early weeks of 2023, several outlets recorded instances of ChatGPT being added to author lists and swiftly adopted prohibitive policies, arguing that AI cannot meet the basic requisites of authorship: assent and responsibility. These episodes functioned as a collective stress test. Editorial teams simultaneously acknowledged AI’s de facto involvement in manuscript preparation and established normative boundaries for its permissible use.

By 2025, the positions of key norm-setting bodies had consolidated around two theses: (1) AI cannot be an author, and (2) its use must be transparently disclosed and, in some contexts—notably peer review—restricted. The canonical cases from early 2023 (adding ChatGPT to author lists) illustrate a categorical breach: AI was presented as a subject of authorship despite being unable to discharge the attendant duties. In parallel, covert AI use emerged. Texts exhibiting “machine” stylistics, inaccurate references, or unusual phrasing entered peer review and publication, prompting investigations and retractions. A telling development concerned the citation “hallucinations”: Retraction Watch [26] documented retracted or soon-to-be-retracted books and materials at major publishers owing to nonexistent sources in bibliographies—symptomatic of uncritical reliance on generative models for citation generation. Such cases demonstrate how the rhetorical fluency of AI can mask the absence of verifiable warrants.

A further axis of uncertainty concerns the use of AI in peer review. Despite explicit prohibitions, reports continue to surface of confidential manuscripts uploaded to public LLM services, violating nondisclosure obligations and potentially contravening data protection requirements. Associations and publishers have issued additional advisories and clarifications [27], whereas journals have strengthened policy sections on confidentiality and the inadmissibility of uploading manuscripts to AI services. This front exposes a particularly vulnerable zone: regulating reviewer behavior. Detection is difficult, and the potential harms—text leaks, data exposure, and the disclosure of personal information—may be irreversible.

Finally, the boundaries of good-faith disclosure remain blurry. Some authors resort to generic statements (“we used ChatGPT for minor editing”) without prompts, version histories, or source traces. Others omit disclosure entirely, even when linguistic fingerprints and atypical references betray AI involvement. Surveys of editorial practice and investigative journalism highlight the difficulty of identifying and verifying AI use from the final text alone [28]. This fuels skepticism toward self-declarations and amplifies the demand for traceable artifacts—prompts, version diffs, and logs—precisely the materials we propose to institutionalize via TraceAuth.

This brings us to a central ethical aporia: how should significant cognitive contributions by AI be related to human responsibility? Current norms rightly prohibit naming AI as an author. In that case, a regime of recognized participation without authorship must be formalized; otherwise, genuine epistemic contributions will either be concealed or overvalued. What is required are operational mechanisms—our TraceAuth (cognitive chain of participation) and AIEIS (epistemic impact metric)—which separate support from creation while keeping responsibility with humans. This logic accords with current ICMJE positions, but unified verification protocols are still lacking.

The picture that emerges from recent precedents and norms is as follows: the publishing ecosystem already accepts AI as a participant in processes while preserving anthropocentric authorship. The gap between de facto participation and de jure recognition generates risks—covert use, leaks, fabricated citations, and ethical–legal collisions. We do not see the solution in granting AI authorship but rather in institutionalizing a regime of recognized participation: transparent disclosure (what, where, and how), verifiable traces (prompts, versions, and sources), and metrics/thresholds that distinguish support from creation. In this context, our pairing of TraceAuth (a protocol for the cognitive chain of participation) and AIEIS (assessment of epistemic impact) addresses the methodological shortfall between COPE/ICMJE norms and real-world practice, enabling acknowledgment of AI’s meaningful contribution without undermining regimes of responsibility and protection.

It is evident that viewing AI solely as a technological tool risks obscuring its genuine ontological status. In the classical philosophy of science, instruments extend human perception without reshaping its epistemic grammar (Heidegger; Ihde). However, we argue that AI does not merely amplify observation; it restructures the very field of interpretation. The Hubble Telescope increases visibility but does not alter the conceptual apparatus; a language model, by contrast, actively participates in the formation of hypotheses and semantic structures. For us, this marks a transition from functional mediation to semantic coparticipation.

In this sense, TraceAuth and AIEIS function not as regulatory mechanisms but as ontological markers of a threshold—capturing the moment when mediation becomes cognitive. AI ceases to be merely a tool and becomes a meta-tool for those who interpret tools. Thus, we conclude that the boundary of instrumentality is reached precisely where mediation begins to transform the conditions of meaning-making rather than merely improving access or efficiency.

To facilitate cross-disciplinary application, the four demarcation tests distinguishing procedural, semantic, and generative participation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demarcation tests for AI participation.

As shown in Table 1, these tests define the boundaries between mechanical execution, semantic contribution, and generative synthesis. They allow reviewers and editors to assess whether AI participation remains instrumental or enters the epistemic domain.

2.4. AI-AUTHORSHIP: A New Authorship Framework

Classical scientific instruments intervene in nature, present data, and assist in interpretation, yet their role remains fundamentally passive: they extend human perception without restructuring the underlying problem. As we noted earlier, a telescope magnifies but does not reinterpret; a pen records but does not reformulate. Artificial intelligence, by contrast, introduces active instrumentality—a state in which mediation becomes recursive. The system not only performs a task but also redefines it, generating new hypotheses, formulations, and symbolic structures.

We interpret this hermeneutic autonomy not as a metaphor but as an ontological shift from functional mediation to epistemic coparticipation. Active instruments reconfigure the problem space, whereas passive instruments merely execute the subject’s intentions. In this sense, AI occupies a liminal position: instrumental in function yet generative in meaning. This is precisely why frameworks such as TraceAuth and AIEIS are necessary because they register and evaluate the scope of these reinterpretations.

The advent of generative and causally oriented AI systems has revealed a mismatch between the actual roles that algorithms play across the research cycle and the legal/ethical construct of authorship. Traditionally, authorship has been reserved for agents capable of intention, consent, accountability, and response to critique—that is, for human beings. However, within the infrastructure of contemporary science, a significant share of epistemic labor is executed by hybrid constellations of people–artifacts–algorithms. The result is a growing fraction of AI’s cognitive participation (hypotheses, model sketches, interpretations) alongside a de jure, anthropocentric authorship regime (COPE, ICMJE).

We therefore propose AI-AUTHORSHIP, a framework that does not confer author status on AI but renders its contribution visible, traceable, and assessable—via a scalable contribution taxonomy, the TraceAuth tracing protocol, the AIEIS metric, and the category of distributed epistemic authorship (DEA), which captures the distributed production of scientific meaning.

At the core of the framework lies a distinction among procedural, semantic, and generative roles. The procedural contribution concerns the acceleration and scaling of standard operations (literature curation, data cleaning, code generation, and summarization); the semantic contribution covers the proposal of hypotheses, alternative interpretive frames, and the semantic recomposition of the corpus; and the generative contribution involves the construction of explanatory schemes and model structures suitable for counterfactual reasoning (causal graphs, analytic dependencies, and mechanistic scenarios). This stratification aligns with the philosophical triad of intervention–representation–hermeneutics and helps to identify the threshold at which support becomes creation.

Operationally, we implement the scale as a three-dimensional P/S/G coordinate system with phase normalization across the research cycle (ideation–design–analysis/modeling–interpretation–content). Each phase poses distinct epistemic risks and therefore receives different weights; for example, semantic and generative components count more in ideation and interpretation than in routine data cleaning. A key principle is a penalty for noninterpretability: if an AI’s contribution in a given phase lacks explainable traces (prompts, versions, sources, local/global explanations), the corresponding axis is set to zero. In this way, the scale hardwires interpretability requirements and counters the effect of “stochastic eloquence,” where fluent prose masks the absence of epistemic warrants.

Crucially, the scale does not displace human responsibility or legal authorship. It introduces epistemic participation as a measurable quantity, shifting the assessment of AI’s role from moral rhetoric to procedures amenable to audit and replication.

If the scale specifies what is measured, TraceAuth (the protocol for tracing the cognitive chain of participation) specifies how it is recorded. We define TraceAuth as a standardized journal of cognitive participation, key to the stages of a manuscript’s lifecycle and to the artifacts in which these stages unfold. In our own practice, for example, we often use three AI-inflected tools: SciSpace (and occasionally Mendeley) for discovering and analyzing related literature (used in this study), a Jupyter Notebook (version 7.5.1) environment for running Python scripts, and diagrams (app.diagrams.net) for visualization (the block diagrams in this paper were created in Diagrams).

For each such epistemic event (E-event), the protocol requires documentation of the initiator (human/AI/mixed), the contribution type (P/S/G), the degree of AI autonomy (manual trigger, semiautonomous toolchains, agentic scenarios), evidentiary artifacts (prompts, version diffs, code changes, data sources, citations), and the form of human sign-off (human validation and acceptance of responsibility).

TraceAuth is aligned with prevailing norms. It does not attribute “authorship” to AI; it provides transparent usage disclosure and auditability—precisely what ICMJE requires. For editors and reviewers, a TraceAuth log can function as a verifiable appendix. Reviewers may request it when AI involvement is suspected and compare the declared roles with the manuscript text. For authors, the protocol constitutes a minimum standard of good practice: specify stages and boundaries of AI intervention, record sources and reproducible steps, and clearly separate substantive proposals (S/G) from rhetorical editing (P).

The AI epistemic impact score (AIEIS) aggregates the AI contributions captured by TraceAuth into a single metric interpretable as epistemic impact. Formally, AIEIS is a weighted sum of P, S, and G components across research phases, normalized to the discipline-specific maximum allowed by the protocol. We underscore that AIEIS is not an “authorship score” and not a legal criterion; it is an indicator that helps distinguish support from creation. We introduce a threshold AIEIS*: when exceeded—because the combined (S + G) component materially reshapes the work’s explanatory architecture—it triggers heightened requirements for reporting, independent replication without AI for key results, and, where appropriate, an explicit manuscript statement noting substantial cognitive participation by AI.

The epistemic rigor of AIEIS is secured by three mechanisms. First, the noninterpretability penalty (above): without explainability, contribution is indefensible. Second, the Delphi-style calibration of weights with editors and methodologists ensures that disciplinary differences (e.g., biomedicine vs. computational linguistics) are reflected in the sensitivity of the scale. Third, a counterfactual check is performed: if a key result can be independently reconstructed without AI, within a reasonable timeframe and by standard means, the S/G assessment is reduced—guarding against overestimation where AI merely accelerates the obvious.

The category of distributed epistemic authorship (DEA) conceptualizes knowledge production as the outcome of distributed coagency among people, artifacts, algorithms, and institutions. Unlike traditional “many hands” authorship lists consisting exclusively of humans, DEA emphasizes that epistemic functions (selection, modeling, interpretation, and verification) are networked. Within that network, AI operates as an infrastructural node—often structurally important but not a bearer of responsibility. This is not the personification of a machine; it is the institutionalization of a fact: significant segments of reasoning can be initiated and shaped within the data–algorithm–human oversight nexus.

DEA does not contradict the de jure prohibition on AI authorship; it supports it by shifting focus from titular status to traceable roles. In editorial practice, DEA is compatible with the CRediT taxonomy but adds an AI-participation axis: who initiated S/G interventions; which algorithms and configurations were used; and who executed human sign-offs. In the spirit of actor–network theory and data-infrastructure studies, DEA treats authorship not as a substance but as a function of a network of evidence. Within this logic, AI-AUTHORSHIP operationalizes DEA: TraceAuth maps the network, AIEIS evaluates the nodes’ contributions, and the P/S/G scale calibrates the degree of semantic impact.

The AI-AUTHORSHIP framework also sets a minimum practice standard for authors, editors, and reviewers. For authors, it enables a shift from vague declarations (“we used ChatGPT for editing”) to auditable disclosure (TraceAuth) and quantitative assessment (AIEIS) with explicit S/G thresholds. For editors, it supports dual-track oversight: compliance with COPE/ICMJE and legal requirements (confidentiality, data protection) plus epistemic checks (explainability; independent reproduction without AI for key results when AIEIS is high). For reviewers, it entails refraining from uploading manuscripts to public LLMs and/or using closed environments alongside the right to request the TraceAuth appendix. For metascience, it couples with SRL (scientific readiness level) [29]: a high early-phase AIEIS may signal intensive cognitive outsourcing, warranting elevated scrutiny of explainability and human control without substituting for scientific novelty per se.

The framework’s most consequential effect, in our view, is to close the normative gap between AI’s factual cognitive participation and anthropocentric authorship. Contribution is acknowledged and quantified; responsibility remains human; epistemic validity is safeguarded by traceability and explainability; and legal propriety is maintained through adherence to existing policies.

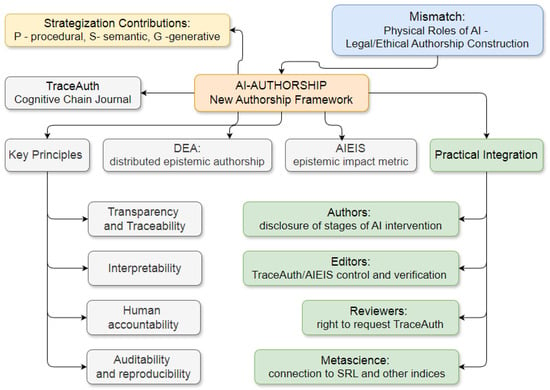

Figure 5 structures the AI-AUTHORSHIP concept as a response to the widening gap between AI’s de facto cognitive participation in the production of scientific knowledge and existing legal–ethical constructions of authorship. The foundational problem is a mismatch: on the one hand, AI actively contributes to hypothesis generation, model formation, interpretation of results, and textual composition; on the other hand, editorial and ethical norms continue to reserve authorship exclusively for humans.

Figure 5.

AI-AUTHORSHIP conceptual framework.

The diagram articulates how AI-AUTHORSHIP bridges this gap by institutionalizing AI’s contribution without attributing subjecthood to it, instead recording participation in a transparent, auditable form. At the center are four key components:

- Contribution stratification into procedural (P), semantic (S), and generative (G) levels.

- TraceAuth, a journal of the cognitive chain that ensures the traceability of AI-driven steps.

- AIEIS is a metric of epistemic impact that quantitatively assesses AI contributions along the P/S/G axes.

- DEA (Distributed Epistemic Authorship) is a conception of authorship as a function of a network of people, artifacts, algorithms, and institutions.

The figure also highlights the principles of AI-AUTHORSHIP—transparency and traceability, interpretability, human responsibility, and audit/reproducibility—which establish normative safeguards to ensure that recognition of AI contributions does not undermine the fundamental requirements of research ethics.

Finally, the scheme illustrates practical integration of the framework for authors (disclosing stages of AI intervention), editors (verifying TraceAuth/AIEIS), reviewers (the right to request the cognitive-chain journal), and metascientific assessments (embedding into SRL and related indices).

Overall, Figure 5 presents a systemic solution to the “AI authorship” problem by shifting the emphasis from “Can AI be an author?” to “How should its cognitive contribution be recorded?” This is the fundamental distinction between AI-AUTHORSHIP and moralizing or purely legal debates. Rather than attributing subjecthood to machines, our framework offers measurable and auditable instruments for accounting for their participation.

P/S/G stratification distinguishes three levels of AI intervention. The procedural level covers the acceleration of standard operations (literature curation, data cleaning, and utility code generation). The semantic level captures contributions to hypothesis formulation, interpretation, and the proposal of new analytic frames. The generative level reflects the construction of explanatory models suitable for counterfactual reasoning. This division prevents the conflation of routine technical assistance with cognitive coauthorship.

TraceAuth introduces mechanisms for documenting the cognitive chain: who initiated an action, which data were used, what prompts were applied, and how versions evolved. This converts AI use from a “black box” into a documented protocol, comparable to a laboratory notebook.

AIEIS complements the system with a quantitative metric. Unlike abstract declarations (“AI assisted”), it measures the strength of epistemic impact across the research cycle. For example, if the S/G component exceeds a defined threshold, this signals substantial cognitive participation by AI, warranting additional review and disclosure.

DEA considers authorship not as a personal attribute but as a distributed network function. It enables the organic inclusion of AI within the epistemic infrastructure without compromising anthropocentric responsibility: the contribution is recorded, whereas responsibility remains human.

Taken together, the AI-AUTHORSHIP diagram in Figure 5 indicates the emergence of a new regime of scientific authorship at the intersection of the philosophy of technology, epistemology, and institutional practice:

- First, AI-AUTHORSHIP dissolves the “tool vs. author” dichotomy. AI is treated as a cognitive agent without a subject: its contribution is recognized, but it does not become an author in legal or moral terms.

- Second, the proposed mechanisms address fears of “stochastic eloquence” in generative models. Transparency and traceability enable verification, whereas AIEIS introduces quantification that differentiates superficial linguistic accompaniment from substantive cognitive intervention.

- Third, the scheme establishes a new norm of interaction among authors, editors, and reviewers: authors must disclose AI interventions; editors gain tools to verify declared contributions; reviewers gain the right to request additional documentation; and metascience gains indicators to evaluate project maturity and rigor.

- Fourth, DEA expands the very notion of authorship. In contemporary science, a paper is not the product of a solitary genius but of a distributed configuration of actors—humans, instruments, algorithms, and institutions. AI-AUTHORSHIP acknowledges this reality and offers operational procedures to institutionalize it.

In summary, Figure 5 proposes that in the era of generative models, the authorship question calls not for metaphysical resolutions but for institutional protocols that make AI contributions visible, measurable, and verifiable while preserving human accountability.

2.5. Philosophical Epilogue: Coauthorship Without a Subject

The guiding intuition of our study is that scientific authorship can be conceived without anchoring it to an ontologically privileged individual subject. This is not a call to personify machines or to extend moral and legal standing to algorithms. Rather, it is a shift in methodological perspective: the explanatory unit of scientific knowledge is not an isolated “I” but a distributed configuration of practices in which human and nonhuman components (instruments, code, formalisms, data infrastructures, editorial procedures) are organized into durable epistemic ensembles. Such a deconstruction of subject-centrism does not abolish intention or responsibility; it relocates them into the plane of roles and traceable functions within networked activity.

This idea of coauthorship without a subject did not arise ex nihilo. From Hacking’s interventionist realism, which roots experimental knowledge in manipulative practice, to instrumental hermeneutics, which treats instruments as mediators of interpretation, from Latour’s assemblages, where scientific facts stabilize in actor networks, to account for knowledge cultures [30] that foreground discipline-specific regimes of evidence—across these horizons, the “author” appears not as a substance but as a nodal effect of interactions. Authorship crystallizes where trajectories of data, methods, and artifacts converge into a form that can be checked, repeated, and inscribed into the collective memory of science.

Against this backdrop, AI endowed with generative and causal-modeling capacities does not require metaphysical subjecthood to have epistemic significance. It functions as a component of distributed cognition, an external module of the extended mind [31], embedded in local discovery pipelines (filtering literature, constructing hypotheses, proposing models and interpretations), but only in tandem with human evaluative judgment, institutional verification, and infrastructures of reproducibility.

We note that AI should not be viewed as a mere procedural amplifier but rather as a generative procedural catalyst. Whereas classical instruments only extend or accelerate existing epistemic operations, AI (particularly large language models) can restructure the very procedures of knowledge production. Its action is clearly not confined to intensifying “input–output” relations; it encompasses the creation of new semantic pathways between data, interpretation, and representation.

In this sense, we argue that generative AI functions not as an enhancer of human cognition but as an epistemic modulator, reshaping the rules by which knowledge is transformed. In both the literature analysis, hypothesis formulation, multimodal synthesis, and ideational recombination via API, LLMs exhibit distinct procedural plasticity—the capacity to reconfigure the underlying logic of the research process. It is precisely this capacity for generative recursion that TraceAuth and AIEIS seek to render transparent—at least to the extent that such transparency is possible.

Accordingly, renouncing subject-centrism does not dissolve responsibility; it clarifies its bearers. From a networked perspective, responsibility is an operator of binding: the signatory of a work undertakes to maintain the link between the published claims and the network of means that produced them (data, methods, computational pipelines, editorial procedures). Where AI has made a substantial semantic/generative contribution, responsibility does not evaporate—it is reinscribed in persons and institutions through procedures of explainability, independent replication, and disclosure of participation. This is “coauthorship without a subject” in the strict sense: the contribution is acknowledged, humans remain the responsible agents, and the category of authorship ceases to be an ontological label, becoming instead a function of networked epistemics.

This redefinition renders visible a longstanding truth of laboratory life: the scientific paper is an artifact of coordination. Its force lies less in the psychology of an individual author than in how it positions itself within trading zones among subcultures of knowledge, how it standardizes and distributes competencies, and how it stabilizes epistemic things through multiple material mediations. Inserted into this fabric, AI does not displace humans; it reconfigures roles. Where manual heuristics once predominated (survey, classification, initial modeling), we now encounter semiautonomous toolchains and agents that demand methodological oversight.

This is precisely why we insist on the pairing of TraceAuth and AIEIS: the former records the cognitive chain of participation; the latter quantifies epistemic impact along the procedural (P), semantic (S), and generative (G) axes, with thresholds that indicate when AI intervention begins to reshape a study’s explanatory structure.

A critic may ask: if there is no subject, how is responsibility possible? The answer follows from the network frame. Responsibility is a role node with rights and duties in an institutional order (journals, funders, universities). It is unambiguously human, but its legitimacy depends on traceability—the ability to reconstruct the trajectories by which data and methods yield conclusions. “Coauthorship without a subject” is therefore an epilogue to the debate on “machine authorship”: we need not endow AI with subjecthood to recognize its contribution; we need only ensure transparent interfaces between human roles and machine operations, where scientific meaning is forged.