Abstract

This study investigates how the traditional Chinese “philosophy of self-cultivation and awakening” (xiu-wu) can be systematically harnessed to foster Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) among undergraduates. Through historical–philosophical reconstruction and conceptual analysis, the study distills three recurring instructional principles—gradual cultivation (jian-xiu), gradual awakening (jian-wu), and sudden awakening (dun-wu), and their dialectical synthesis, and re-casts them as design parameters for thinking-centered instruction. These principles are then translated into a macro-level instructional metaphor, the Bridge-Building Model, which sequences curricular elements as bridge piers (the teaching process of “gradual cultivation”), bridge deck (student-constructed “an isolated fragments of knowing”), and final closure (holistic knowledge). The model integrates constructivist, behaviorist and intuitive dimensions: repetitive, scaffolded tasks foster behavioral automaticity; guided reflection precipitates incremental insight; and calibrated “epistemic shocks” elicit sudden reorganization of conceptual schemata. The framework clarifies the locus, timing and contingency of each phase while acknowledging the metaphysical indeterminacy of ultimate “holistic” mastery. By translating classical Chinese pedagogical insights into operational design heuristics, the paper offers higher-education instructors a culturally grounded, theoretically coherent blueprint for systematically nurturing HOTS without sacrificing the spontaneity essential to creative cognition.

1. Introduction

In the philosophical traditions epitomized by Confucian, Daoist and Buddhist schools in China, scholars have universally aspired to a “meta-physical” spiritual horizon. Confucius and Mencius denominated it “Ren-yi” (humaneness and rightness)1; Laozi and Zhuangzi termed it the “Dao” (The Way of Nature)2; Buddhist teachings designate it “Guo-wei” (fruit of awakening)3. Subsequent developments produced Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism’s “Tian-li” (Heavenly Principle)4 and Wang Yangming’s “Liang-zhi” (conscience)5. Because these ideals are philosophically consummate yet cognitively indeterminate, they elude discursive articulation and are proclaimed the constant Dao.” Consequently, their epistemological character is marked by mysticism and a quasi-religious dimension.

Across millennia of Chinese philosophical evolution, innumerable thinkers have subjected the question of how this “meta-physical” state might be attained to rigorous theoretical inquiry and embodied praxis. These investigations yielded systematic philosophical positions endowed with pragmatic efficacy. Especially noteworthy are the “Zen” (Chan)6 traditions that arose in the early Tang Dynasty, within which two paradigmatic soteriological modalities—“Jian-xiu” (gradual cultivation)7 and “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening)8—emerged. Although their procedural methods diverge sharply, both aim at the realization of Buddhist truth and have generated extensive documentary evidence of successful exemplars. This empirical success has elicited sustained scholarly attention and catalyzed a prolific corpus of theoretical elaborations in subsequent ages.

In higher-education practice, the central instructional objective of cultivating High-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) exhibits a similarity with the classical Chinese quest for a “meta-physical” spiritual horizon. First, Chinese philosophy’s emphasis on holism, ethics, and introspection provides a rich foundation for developing HOTS such as systemic thinking, ethical reasoning, socio-emotional knowledge, metacognition, critical thinking, and creativity [1,2]. Secondly, the goals of both have a certain degree of “unpredictability”, making it difficult to provide a unified and clear definition and description. Third, from the perspective of transfer and continuity, ancient Chinese philosophical practices inherently promote “far transfer” due to their holistic nature, similarly, the continuous practice and internalization of these philosophical tenets, akin to the concept of “continuity,” ensure that HOTS become an integral part of an individual’s intellectual and ethical development [3]. Consequently, the Chinese Xiu-wu9 philosophy—originating in Zen Buddhism’s dialectic of “Jian-xiu” (gradual cultivation) and “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening)—may have potential value for the methods of cultivating high-level thinking abilities of contemporary college students.

Current studies about the “Xiu-wu” (self-cultivation and awakening) philosophy has already offered conspicuous methodological insights for education. Scholarly analyses of Zen pedagogy have focused primarily on (a) analogies between the gradual-cultivation paradigm and educational processes [4], (b) the moral-education value of Zen thought [5], and (c) the educational significance of “Wu-xing Si-wei” (awakening-oriented thinking)10 [6,7]. These studies advance propositions of general import, demonstrating that the essence of education lies in learners’ self-directed elevation and excavation of the authentic self, and that, consonant with constructivist learning theory, the subjectivity inherent in awakening-oriented thinking facilitates students’ autonomous construction of knowledge systems. On the one hand, only a few studies have explored the impact of Xiu-wu philosophy on modern pedagogy. On the other hand, no research has yet conducted an in-depth analysis of the insights that Xiu-wu philosophy offers for the cultivation of high-order thinking skills.

The cultivation of higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) in students is a critical area of contemporary educational research, reflecting a global shift towards fostering competencies beyond rote memorization for 21st-century challenges [8]. Several studies highlight diverse approaches and frameworks for developing these essential skills. For instance, an authentic assessment model has been shown to significantly improve students’ literacy skills by promoting higher-order thinking, particularly in analysis, evaluation, and creation, aligning with OECD standards [9]. Furthermore, integrating creative pedagogy within Problem-Based Learning (PBL) in natural science education has been found to substantially enhance students’ HOTS, enabling them to critically analyze, evaluate, and devise innovative solutions for complex problems [10]. From a conceptual standpoint, HOTS encompass problem-solving, metacognition, critical thinking, teamwork, and innovation development, with critical thinking and innovation identified as the most crucial dimensions for K-12 students [11]. Research also indicates a growing trend in the study of HOTS, especially within blended learning environments, emphasizing the importance of fostering these skills in flipped classrooms and through scaffolding activities [12]. In higher education, various teaching strategies, including scaffolding instruction, heuristic instruction, project-based instruction, collaborative learning, and diversified assessment feedback, have been proposed and validated for cultivating HOTS in college students [9]. These studies collectively underscore the multifaceted nature of HOTS development and the necessity of adopting varied pedagogical and assessment approaches to effectively equip students with these vital cognitive abilities. It is of great academic value to conduct research on the methods for enhancing HOTS in a broad sense from a philosophical perspective.

Therefore, in order to fill the research gap, apply the past to the present, and provide new ideas for the cultivation methods of HOTS, this study takes the Chinese “Xiu-wu” (self-cultivation and awakening) philosophy as its point of departure, translating insights from the thinkers related to Zen Buddhism since then into principles for cultivating HOTS, and synthesizes them into a pedagogical model for undergraduates, thereby supplying both methodological guidance and theoretical grounding for HOTS education.

2. Historical Development of the Xiu-Wu Philosophy in Chinese Traditional Culture

To study the implications of Chinese philosophy of “self-cultivation and awakening” on the cultivating of HOTS, it is first necessary to summarize and analyze the historical development of the philosophy of “self-cultivation and awakening”. Some research shows that philosophy of “self-cultivation and awakening” witnessed significant development and improvement in the Tang Dynasty, Song Dynasty, Ming Dynasty and modern times due to the theories of some great philosophers [13]. In order to simplify the analysis process and highlight the development context, this article only selects the viewpoints of these great philosophers as the research focus for analysis.

Zen Buddhism, an indigenous Chinese offshoot of Buddhism, posits that the mind is intrinsically pure and that Buddhahood is originally inherent. It advocates attaining enlightenment through direct, unmediated experience of one’s own mind. It is said that it was introduced to China by Bodhidharma during the Northern and Southern Dynasties, who was venerated as the First Patriarch. During that period, Zen Buddhism began to collide with Chinese local philosophical thoughts such as Taoism and integrated the concept of enlightenment with local concepts [14,15]. This process of localization also promoted thoughts on the diversification of cultivation methods, laying the ideological foundation for the subsequent sudden and gradual disputes [16]. Then Zen Buddhism spread widely among the populace, and in the early Tang dynasty it flourished through the Southern School of Huineng (the Sixth Patriarch) and the Northern School of Shenxiu.

With respect to soteriological doctrine, Shenxiu of the Northern School and Huineng of the Southern School diverge markedly. Revered as “foremost in comprehensive and luminous discernment,” Shenxiu composed the gāthā:

- “The body is the Bodhi tree,

- The mind a bright mirror-stand;

- Ever and again polish it with care,

- Lest dust upon it land.”

The verse enjoins sustained, meticulous cultivation of daily conduct so that the mind—likened to a polished mirror—remains unsullied; only thus can awakening and Buddhahood be realized. This position advocates gradualism: “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening.”11 [17]. Its rationale rests on both philosophical and religio-historical grounds: the Dharma is profound and therefore demands protracted reflection and inquiry, and the historical Buddha himself attained realization only after years of ascetic practice [18]. Yet the Northern School takes long periods of sitting in meditation and contemplation as the main approaches to gradual cultivation [19]. This means that at that time, practitioners often could not balance their cultivation and labor, and long time of practice is easy to make people discouraged. Therefore, Shenxiu’s theory of cultivation did not enable the Northern School to be widely spread.

Upon hearing Shenxiu’s verse, the Sixth Patriarch Huineng is said to have replied:

- “Bodhi originally has no tree,

- The bright mirror is not a stand;

- From the outset not one thing exists—

- Where, then, could dust alight?”

Grounded in this insight, he articulated the Southern School’s doctrine of “direct pointing to the human mind, sudden awakening to Buddhahood.” Sudden awakening (Dun-wu) posits that, given the right moment and an apt pedagogical trigger, enlightenment can occur instantaneously. Canonical support abounds in texts such as the “Visuddhimagga” and the “Platform Sūtra” [20]. However, compared with the gradual cultivation that leads to gradual awakening, this approach lacks a rigorous rational structure; it relies more heavily on the practitioner’s individual insight and innate aptitude [21]. Moreover, as the idiom “a blow and a shout to the head” intimates, sudden enlightenment hinges on the master’s timely, well-calibrated intervention; the guide’s artful pedagogy is itself a decisive condition. Conversely, by de-emphasizing gradual practice and affirming that awakening is possible without becoming a monk, the Southern School—despite its high demands on both practitioner and teacher—spread widely among laypeople and ultimately became Chan’s dominant form.

The “Northern gradualism versus Southern suddenness” controversy did not terminate with the latter’s institutional and doctrinal victory; subsequent thinkers continued to interrogate the dialectic of Jian (gradualism)12 and Dun (suddenness)13, Xiu (cultivation)14 and Wu (awakening)15. Within Cheng–Zhu Neo-Confucianism, the maxim “today investigate one thing, tomorrow another” prescribes a cumulative, incremental approach to enlightenment through the exhaustive study of external phenomena. By emphasis on Ge-wu-zhi-zhi (investigating things to extend knowledge), Cheng–Zhu school treats exhaustive, incremental study of external phenomena as the route to progressively apprehending the universal “Li”16. In this process, knowledge and understanding are acquired through gradual accumulation and progressive steps. Therefore, it can be considered that the philosophy of cultivation in Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism approaches the theory of “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening” [22].

On this basis, Wang Yangming’s School of Mind also carried out further exploration and development. Its “Si-you” (Four-With)17 thesis maintains that the mind is constituted of innate elements whose refinement through disciplined practice progressively elevates one to the state of Liang-zhi (innate good knowing), thus exhibiting clear gradualist features. Conversely, the “Si-wu” (Four-Without)18 thesis posits a transcendent, originally immaculate nature; realization here is conceived as a discontinuous, horizon-level event, implicitly embracing sudden awakening [23]. Wang Ji explicitly designates Dun-wu (sudden awakening) as the optimal modality for accessing the “Si-wu” (Four-Without) state [24]. Yet even Four-Without praxis requires prior purification via introspective discipline, thereby integrating rather than repudiating the logic of gradualism. Consequently, the gradualism and suddenness strands function complementarily. Wang Yangming believed that through the practice of “stillness”, one could have a slight enlightenment of the conscience, that is, “to be still and enlightened, to have a slight understanding of one’s true nature”, which was an endorsement of the theory of “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening). However, Wang Yangming also believed that it is difficult for an individual to fully understand the “Liang-zhi” (conscience) in one enlightenment. A single enlightenment can only recognize a part of the “Liang-zhi” (conscience), which is called “an isolated fragment of knowing”19. Only through multiple enlightenments can one gradually expand from “an isolated fragment of knowing” to “holistic knowledge”20. This is a process of continuously deepening and thoroughly recognizing one’s own conscience, and it is also a process of “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening” [25].

Modern Chinese philosophers have likewise re-examined the Zen dialectic of “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening) and “Jian-xiu” (gradual cultivation). Drawing on the records of Shenhui and Esoteric Buddhism, Hu Shi proposed a fourfold taxonomy of Zen “awakening”:

- Sudden awakening-sudden cultivation: awakening resembles severing a tangled skein with one stroke; cultivation is like plunging white silk into a vat—red becomes red, black becomes black, instantaneously and without remainder.

- Sudden awakening-gradual cultivation: comparable to a newborn whose sex and faculties are fully present at birth (sudden awakening), yet who must grow and be educated to become a complete person (gradual cultivation). Thus, post-awakening practice remains indispensable.

- Gradual cultivation-sudden awakening: analogous to felling a tree—after a thousand axe-strokes it still stands (gradual cultivation), but the thousand-and-first stroke brings it crashing down (sudden awakening). The final fall is not due to the last blow alone, but to the cumulative momentum of all preceding strokes.

- Gradual cultivation–gradual awakening: like polishing a mirror from coarse bronze to reflective brightness, or like archery progressing from total misses to eventual bulls-eyes [26].

Hu Shi’s typology lucidly differentiates these philosophy of cultivation and yields practical pedagogical judgments. He argues that “sudden awakening-gradual cultivation” and “gradual cultivation-sudden awakening” are both realizable through instructional design; “gradual cultivation-gradual awakening” represents the ordinary learning trajectory most congruent with everyday experience; only “sudden awakening-sudden cultivation” is untenable, for it admits of no teachable method [26]. Hu’s stance is grounded in a rationalist methodology that privileges intellect, reason, and historical praxis [27].

Concerning the “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening) philosophy that eludes rational or discursive analysis, several modern scholars have re-interpreted it through the lens of intuitionism. Both “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening) and intuition are held to disclose the ultimate noumenon and to effect the passage from the empirical ego to the transcendental ego; hence the two doctrines exhibit extensive theoretical congruence [20]. Liang Shuming, a pioneer of New Confucianism, argued that “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening) achieved via intuition cannot be submitted to scientific logic or to invariant, replicable laws, thereby tacitly endorsing its religio-mystical character [28]. Building upon this, Xiong Shili reframed the temporal dimension of “sudden enlightenment” and intuition: their emergence should not be reduced to sheer brevity; by extending the temporal horizon, the intrinsic rapport between intuition and logical deliberation can itself become an object of philosophical inquiry [29]. Hence, only after a certain threshold of cumulative epistemic capital has been attained can an individual’s cognition leap into a genuinely intuitive insight. Moreover, people readily achieve a comprehensive Wu (awakening) to the whole, and this very awakening facilitates the subsequent accretion of finer details. Thus, gradual cultivation furnishes the discursive groundwork for sudden awakening, while the sudden awakening of “an isolated fragment of knowing” supplies the orienting vision for further gradual cultivation. In actual cultivation practice, The question of which precedes the other-“Jian-xiu” (gradual cultivation) or “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening)-admits no fixed sequence. Studies conclude that Xiong Shili regards logical and discursive reason, deployed as an analytic instrument, not only as a necessary preparation for “shen-wu” (mystical apprehension, intuitive realization, etc.)21, but also as the very means by which the content of such realization can be systematically articulated and “ecured and sustained for knowledge through practice.” In effect, Xiong adumbrates the twofold problem of “post-discursive intuition” and the “intellectualization of intuitive gains” [30].

In his methodological reflections, Feng Youlan distinguishes two approaches: the “positive method” of logical analysis and the “negative method” of intuitionism. He conceives them as the mutually indispensable moments of “Li” (establishment)22 and “Po” (sublation)23 within the process of “Wu” (awakening): without sublation there is no establishment, and without establishment no sublation; only their dialectical interplay gives rise to “Wu” (awakening). Feng further offers an explicit definition of “Wu” (awakening) as “the momentary conjunction of concepts with immediate experience within a comparatively brief span of time.” Feng further offers an explicit definition of “Wu” (awakening) as “the momentary conjunction of concepts with immediate experience within a comparatively brief span of time.” [31] Concepts and direct experience are supplied by the positive method; their conjunction is effected through the negative method. Moreover, Feng insists that the use of “Ji-feng” (clever repartee)24 or “Bang-he” (blows and shouts)25 as pedagogical devices does not itself constitute metaphysical intuition; since these tactics are rule-governed, they remain rational and logical [32]. This theory integrates the philosophical foundations of “Jian-xiu” (gradual cultivation) and “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening), positing their dialectical unity. His disciple Feng Qi further advanced the notion of “rational intuition,” offering a penetrating account of how knowledge and wisdom interpenetrate. For Feng Qi, rational intuition is the synthetic unity of sensibility and reason, as well as the unity of subject and object; it delivers a sudden, all-encompassing illumination. Far from being esoteric, this intuition pervades every domain of spiritual activity—scientific research, the arts, moral life, and religious experience alike. It both transcends reason and remains open to rational argument and verification. Rational intuition is thus a unified epistemic method in which the subject’s sensibility and reason coincide—a synthesis of rationality and intuition. This theory thereby furnishes a philosophical corroboration that gradual cultivation and sudden awakening are inseparable and mutually enabling.

3. Insights from the “Cultivation-and-Awakening” Philosophy for Cultivating Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS)

The author contends that the Zen pedagogical dialectic of “gradual cultivation-gradual awakening” and “sudden awakening,” along with its subsequent elaboration, can be applied to analyze specific teaching environments and thereby formulate customized teaching models consistent with the operational principles of that environment. The cultivation of HOTS constitutes a core objective of higher education; yet, HOTS differs from knowledge-based outcomes in that it resists an unequivocal, exhaustive definition and its emergence cannot be fully explicated by logical analysis alone. As noted earlier, the process of cultivating HOTS parallels the traditional Chinese “self-cultivation and awakening” quest for a metaphysical plane of mind. The methodology of “cultivation-and-enlightenment” philosophy can be employed to investigate the cultivation of HOTS and to design an applicable model for its development.

“HOTS” is a general term for a series of ontological multiple thinking abilities, including but not limited to: associative ability, analytical ability, planning ability, decision-making ability, critical thinking ability, creative thinking ability, etc. These competences resist explication through strictly linear-logical pathways and are, more often than not, instantiated via acts of “Wu” (awakening). Consequently, the first task is to interrogate what Zen canonical thought and its pedagogical experience can contribute to HOTS development. Unlike Zen’s focus on ontological self-awareness to achieve metaphysical awakening, HOTS also entails exerting transformative influence upon the external world. Hence, the Northern School’s gradual-cultivation philosophy—grounded in drawing wisdom from continuous engagement with the external, material world—must inevitably inform the cultivation of HOTS.

When the Zen doctrine of “gradual cultivation, gradual awakening” is applied to HOTS development, the immediate questions are what is to be cultivated? and how to awaken? The “living Zen” or “everyday Zen” model proposes that the entirety of daily life becomes the locus of cultivation; meticulous attention to each mundane act is itself Zen practice, attaining in existential awakening. Since HOTS is fundamentally the capacity to transform external information into internal thought—a species of learning—the same logic suggests that routine study and reflection can incubate HOTS, a stance consonant with constructivist pedagogy. Yet such undifferentiated practice is insufficient for cultivating HOTS; beyond Everyday Zen, content-specific and method-specific learning must be introduced so that students can, in the very process of study, awaken to discrete aspects—or the full architecture—of HOTS.

Like the “holistic knowledge,” the full landscape of HOTS lacks exhaustive articulation; yet its constituent “an isolated fragment of knowing” are determinate and amenable to rational specification. By the classify by Marzano, the HOTS indicators included were comparison, classification, association, deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning, error analysis, construction, analysis perspective, abstraction, decision-making, investigation, problem solving, inquiry experiment, innovation finding, and so on [33], among others, can each be given clear, logically grounded definitions. Moreover, although these discrete “an isolated fragment of knowing” conform to rational logic, their acquisition by students necessarily involves intuition and an element of awakening that cannot be attained through logic alone—thereby corroborating the thesis that discursive inquiry undergirds intuitive insight. Take associative ability as an example. Simply explicating its definition and presenting illustrative cases through didactic instruction is demonstrably inefficient for engendering the capacity itself. A method that is more in line with educational theory and the philosophy of “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening.” is to have things with certain similarities but also with thinking breakpoints repeatedly appear in the teaching process, and through the guidance of teaching methods, help students think independently and explore independently, and assist students in generating associations about the relationships between these things on their own. The ability to associate thus emerges naturally. By studying this process, it can be found that this teaching method, which conforms to the philosophy of “gradual cultivation and gradual enlightenment”, in the part of gradual cultivation, conforms to the teaching theory of behaviorism. It needs to emphasize students’ autonomous behavior. Through a certain amount of repetitive stimulation, it strengthens students’ way of thinking in a certain situation. After completing the reinforcement of the way of thinking, students have already developed the habit of completing this kind of thinking. The process of internalizing ability requires the participation of “insight”. The part of gradual enlightenment conforms to the constructivist ideology in terms of educational theory. While emphasizing students’ autonomy, it also highlights the guidance of teachers at critical moments. However, due to the repeated stimulation of the gradual practice part, it also provides many opportunities for enlightenment. Therefore, in principle, as long as the number of repetitions is sufficient, the vast majority of students can gradually achieve “knowledge of one section” through this “gradual practice and gradual understanding” teaching method. This method is feasible and efficient.

There are also deficiencies in merely adopting this “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening” teaching method to cultivate HOTS abilities. This teaching model, due to its long process and low feedback frequency, exhausts the patience of practitioners in the high time cost and the lengthy process lacking feedback, and even makes them hesitate before they even start. Therefore, introducing the “sudden awakening” theory into the learning process is conducive to enhancing learning outcomes. At the same time, it is necessary to take the lack of feedback in the “sudden enlightenment” theory as a warning. Thus, in the process of cultivating HOTS, it is necessary to break down the longer cultivation process into sections, reduce the difficulty of achieving the learning goals in each section, and provide positive feedback in a timely manner through assessment and other means. Attention should also be paid to the frequency of positive feedback throughout the process to continuously motivate students and maintain their enthusiasm. The above-mentioned methods also conform to the teaching theory of behaviorism.

Secondly, in the aforementioned “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening” teaching method, the “gradual cultivation” part has relatively high requirements for students’ initiative, self-study ability and independent thinking ability. In the “gradual awakening” section, students are also required to be able to think independently. It is evident that before the above-mentioned shaping methods, it is necessary to train students on their basic learning habits and skills. The learning habits and skills that need to be trained include: the autonomous awareness of active learning, the learning habit of lifelong learning, the channels and skills for consulting materials, the methods and tools for organizing materials, group learning through cooperation and division of labor, the way of thinking from others’ perspectives, the awareness of questioning, and the awareness of empirical evidence, etc. This process also needs to pay attention to the frequency of positive feedback and enhance the motivation for students.

Thirdly, the “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening” teaching method is relatively suitable for methodological philosophy that is closely related to the material world. However, most of the learning objectives in the above-mentioned HOTS cultivation methods belong to methodological philosophy and require the addition of the “sudden awakening” theory. According to the theory of “sudden awakening”, whether students’ epistemology can be influenced in the initial stage of the teaching process will have a significant impact on their initiative, sense of purpose and the way of “awakening”. Therefore, in order to effectively influence students’ epistemology in a short period of time, the “a blow and a shout delivered at the critical moment” method in Zen Buddhism can be applied. By using vivid cases, students can be made to have intense doubts about their existing understanding in a short time. This part employs the relevant theory of the “negative method”. Then, use the “positive method” to instill a highly impactful new epistemology and establish a conceptual understanding of “holistic knowledge”.

In addition to helping students break through epistemology, “sudden awakening” may also occur during the process of refining learning habits and skills after establishing knowledge, as well as the “gradual cultivation” of “an isolated fragment of knowing”. According to Zen theory and Mr. Hu Shi’s explanation, whether “sudden awakening” can be achieved depends on the student’s talent level and whether the postnatal conditions are complete. Then, due to the differences among students, a very small number of students may have already completed the cultivation of methodology before learning, and under the “sudden awakening” of epistemological transformation, they may immediately achieve “holistic knowledge”. Some students may not achieve “sudden awakening” until a long time after completing the teaching process of each link due to a certain opportunity. Therefore, the “sudden awakening” process of mastering “holistic knowledge” has obvious metaphysical characteristics and is difficult to predict and control. Therefore, regarding this aspect in the process of cultivating HOTS, it is also very difficult to design it using rational logical methods. Students should be advised to persist in the study of philosophical theories and self-reflection, constantly improving themselves.

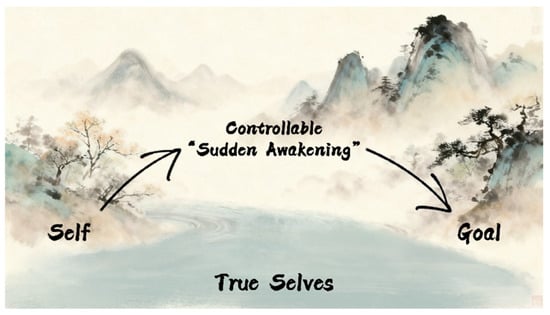

4. A HOTS Cultivation Model Under the Guidance of “Self-Cultivation and Awakening” Philosophy

The process of cultivating HOTS extracted from the “Self-Cultivation and Awakening” Philosophy mentioned above can be compared to a model of building a bridge and crossing a river. A student walked to the bank of a big river and found that the water was wide and magnificent, making it difficult to cross. The vast river here is the “chasm” that needs to be overcome to cultivate HOTS. When students see the big river, they will immediately have the idea of building a bridge to cross it under guidance. This is a process where based on one’s own characteristics, a goal is discovered and, with guidance, a “sudden awakening” can be achieved. Since this process conforms to rational logic on the basis of the learner’s self-pursuit, it is a kind of controllable “sudden awakening”. The process of stage 1: Discover the goal is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stage 1: Discover the goal.

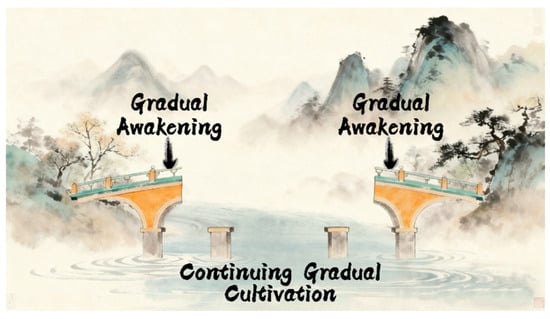

Then, after students have clarified the goal of building the bridge, they need to examine and transform the environmental conditions for bridge construction, which is an examination and transformation of their “true selves”. If the river bed silt is too thick, it is difficult to pile on the river bed to erect piers, even if the forced erection of piers will lead to the destruction. In contrast, if a student’s own learning habits and skills cannot meet the demands of the shaping process, they need to improve themselves. After the environmental conditions have been improved, students need to select an appropriate location to drive piles and erect bridge piers. The process of site selection and pier erection is like students gradually cultivating according to the designed teaching process, laying the foundation for “gradual awakening”, as the stage 2: gradual cultivation shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Stage 2: gradual cultivation.

After the corresponding bridge piers are stabilized, students can start laying this section of the bridge deck. Just like when the “gradual cultivation” of a part is completed, students may “gradual awaken” the “an isolated fragment of knowing” on this basis. This process called the stage 3: gradual awakening is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Stage 3: gradual awakening.

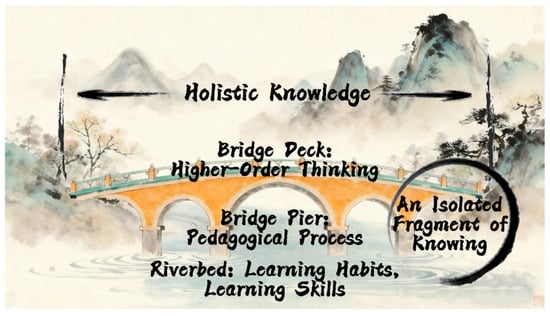

After that, students will be able to repeatedly complete the work of setting up bridge piers and laying the bridge deck until before the bridge to be closed. That is to say, students can gradually achieve the understanding of several “isolated fragment of knowings” through “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening” until before they grasp the “holistic knowledge”, as shown in Figure 4. Finally, the closure of the bridge is no longer a factor within the students’ control. It might be completed smoothly, or the gap between the two sections of the bridge could be very small, and they could cross the river simply by crossing it, in which case there would be no need for the closure. This corresponds to the “metaphysical” attribute of the goal and the unknowability of “sudden awakening”. When and whether the “sudden awakening” that ultimately leads to “holistic knowledge” occurs is not completely controllable.

Figure 4.

Stage 4: sudden awakening.

Then, the entire bridge-building model can be sorted out and summarized as shown in Figure 5. In metaphor about the process of cultivating HOTS, the great river corresponds to the overall goal of cultivating HOTS; the riverbed corresponds to students’ learning habits and skills. Bridge piers correspond to the teaching process of “gradual cultivation”; the bridge deck corresponds to the HOTS generated by students, which is the specific goal of “gradual awakening” and “sudden awakening”. Especially, there is a corresponding relationship between the bridge deck and the bridge piers. Each “gradual cultivation” content, that is, the section of the bridge deck supported by the bridge pier, is the “an isolated fragment of knowing” corresponding to the HOTS, and the entire bridge deck is the “holistic knowledge” of the HOTS. Due to the influence of a series of complex factors such as students’ own conditions and talents, and the different abilities of instructors to grasp the right time for guidance, the actual process of cultivating HOTS may not conform to every link of the bridge-building model. This model has a guiding significance for the overall process of cultivating HOTS, and for specific problems, specific analysis and flexible handling are needed; it cannot be mechanically applied.

Figure 5.

The Bridge-Building Model.

5. Conclusions

Starting from the “Xiu-wu” (self-cultivation and awakening) philosophy in traditional Chinese culture, this paper studies the analysis of the concepts of “Jian-xiu” (gradual cultivation), “Jian-wu” (gradual awakening)26 and “Dun-wu” (sudden awakening) in ancient and modern Chinese philosophy circles since the Tang Dynasty, draws valuable thoughts from them, and discusses the enlightenment of these thoughts on the cultivation process of Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS): Through a “gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening” teaching process, students’ understanding of “an isolated fragment of knowing” is gradually enhanced one by one, and the role of “sudden awakening” in the teaching process is recognized and encouraged, which can effectively improve students’ Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS). Based on the above inspirations, the Bridge-Building Model was sorted out and proposed, as shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. The model integrates constructivist, behaviorist and intuitive dimensions: repetitive, scaffolded tasks foster behavioral automaticity; guided reflection precipitates incremental insight; and calibrated “epistemic shocks” elicit sudden reorganization of conceptual schemata. The framework clarifies the locus, timing and contingency of each phase while acknowledging the metaphysical indeterminacy of ultimate “holistic” mastery. By translating classical Chinese pedagogical insights into operational design heuristics. This paper offers higher-education instructors a culturally grounded, theoretically coherent blueprint for systematically nurturing HOTS without sacrificing the spontaneity essential to creative cognition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. (Zixu Zhu) and H.D.; methodology, M.H.; validation, H.D. and Z.Z. (Zhihong Zhang); investigation, N.H.; resources, H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z. (Zixu Zhu); writing—review and editing, H.D.; visualization, N.H.; supervision, M.H.; project administration, H.D.; funding acquisition, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Defense and Military Education Discipline Planning Project] grant number [JYKY-C 2025016].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | 仁义—“Ren-yi”—(humaneness and rightness). |

| 2 | 道—“Dao”—(The Way of Nature). |

| 3 | 果位—“Guo-wei”—(fruit of awakening). |

| 4 | 天理—“Tian-li”—(Heavenly Principle). |

| 5 | 良知—“Liang-zhi”—(conscience). |

| 6 | 禅—“Chan”—(Zen). |

| 7 | 渐修—“Jian-xiu”—(gradual cultivation). |

| 8 | 顿悟—“Dun-wu”—(sudden awakening). |

| 9 | 修悟—“Xiu-wu”—(self-cultivation and awakening). |

| 10 | 悟性思维—“Wu-xing Si-wei”—awakening—oriented thinking. |

| 11 | 渐修渐悟—“Jian-xiu-jian-wu”—(gradual cultivation towards gradual awakening). |

| 12 | 渐—“Jian”—(gradualism). |

| 13 | 顿—“Dun”—(suddenness). |

| 14 | 修—“Xiu”—(cultivation). |

| 15 | 悟—“Wu”—(awakening). |

| 16 | 理—“Li”—(Principle). |

| 17 | 四有—“Si-you”—(Four-With). |

| 18 | 四无—“Si-wu”—(Four-Without). |

| 19 | 一节之知—“Yi-jie-zhi-zhi”—(an isolated fragment of knowing). |

| 20 | 全体之知—“Quan-ti-zhi-zhi”—(holistic knowledge). |

| 21 | 神悟—“shen-wu”—(mystical apprehension, intuitive realization, etc.). |

| 22 | 立—“Li”—(establishment). |

| 23 | 破—“Po”—(sublation). |

| 24 | 机锋—“Ji-feng”—(clever repartee). |

| 25 | 棒喝—“Bang-he”—(blows and shouts). |

| 26 | 渐悟—“Jian-wu”—(gradual awakening). |

References

- Yu, J. Feng, Youlan and Greek Philosophy. J. Chin. Philos. 2014, 41, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, X. The enlightenment of Chinese philosophy to the construction of contemporary ecological civilization. Trans/Form/Ação 2024, 47, e0240070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottaccioli, F.; Bottaccioli, A.G. The suggestions of ancient Chinese philosophy and medicine for contemporary scientific research, and integrative Care. Brain Behav. Immun. Integr. 2024, 5, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Li, Bai’s story of “grinding an iron rod into a needle” and the Chan view of gradual awakening. Extracurricular Chin. 2015, 184. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P. Research on the moral-education thought of the Platform Sutra and its contemporary value. Hangzhou Zhejiang Univ. Financ. Econ. 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, E. Education as ontological self-awareness: On the ontological characteristics of Chan education and their implications. Time Educ. 2015, 53–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. Chan awakening thinking and its implications for education. Abil. Wisdom 2015, 78+80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huan, L.; Kee, C.N.L. Construction of a Teaching Strategy Model for Cultivating Higher-Order Thinking Skills in College Students. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Bus. Manag. 2024, 2, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffah, H.S.; Evie, S.; Suherli, K. Authentic Assessment Based on Higher Order Thinking Skills in Improving Student Literacy. Br. J. Teach. Educ. Pedagog. 2024, 3, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affandy, H.; Sunarno, W.; Suryana, R. Integrating creative pedagogy into Problem-based learning: The effects on higher order thinking skills in science Education. Think. Ski. Creat. 2024, 53, 101575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Cheng, Y. K-12 students’ higher-order thinking skills: Conceptualization, components, and evaluation Indicators. Think. Ski. Creat. 2024, 52, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Swaran, S.C.K.; Ale, E.N. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of higher-order thinking skills in blended learning. Perspect. Sci. Educ. 2022, 59, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C. Review on Research Methodology in Chinese Philosophy and the Way for Modern Development—Also the Relationship Between Creative Capability in Thinking and the Modern Legality. J. Taiyuan Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2005, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Q.; Yao, R. On Multielement of Culture and Literature & Art in Wei and Jin Dynasties and Northern and Southern Dynasties. J. Luoyang Univ. 2002, 3, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yonghai, L. Philosophical Reflections on “Sudden Enlightenment” and “Meditation”. Acad. Mon. 2007, 9, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Litian, F. A Tentative Discussion of the Characteristics of Chinese Buddhism. Chin. Stud. Philos. 1989, 20, 3–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. On the similarities and differences between gradual cultivation and sudden awakening. Relig. Stud. 2002, 58–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kilty, G. Awakening the Mind of Enlightenment. Meditations on the Buddhist Path. Geshe Namgyal Wangchen. Buddh. Stud. Rev. 1990, 7, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T. The intellectual history of Chan Buddhism in the Tang and Song Dynasties and Japanese Zen: Borrowing the perspective of D.T. Suzuki. Stud. Chin. Relig. 2022, 8, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewamanage, W. Sudden Awakening and Gradual Awakening; Wuhan University: Wuhan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. The similarities and differences between Chan Buddhism’s “sudden awakening” and “non-duality” and Bergson’s “intuition” and “duration”. Masterpieces Rev. 2020, 176–177+180. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. A preliminary study of the relationship between Neo-Confucianism and Buddhism in the Song and Ming periods: A comparison of “investigating things thoroughly” and “gradual cultivation leading to sudden awakening”. Study Pract. 2013, 134–140. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Gradual Awakening and Quiet Sitting: Two Paths in Wang Yangming’s Theory of Self-Cultivation; Shanxi Normal University: Linfen, China, 2022; (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Collected Works of Wang Ji; Phoenix Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 2007; pp. 42–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q. Gradualness Within Suddenness and Cultivation Within Awakening; Shandong University: Jinan, China, 2023; (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S. Modern Scholarly Collection on Buddhism: Hu, Shi Volume; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 1995; pp. 259–260. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. An epistemological interpretation of Chan Buddhism’s doctrine of sudden awakening. Philos. Res. 2013, 47–53+65+127–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S. Eastern and Western Cultures and Their Philosophies: Complete Works of Liang Shuming; Shandong People’s Publishing House: Jinan, China, 1989; Volume 1, p. 359. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, S. Essential Sayings of Xiong Shili, Vol. 4, Book 2; Shanghai Classics Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2018; p. 357. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R. Chan Buddhism and modern Chinese philosophical intuitionism: From the perspective of the convergence of Confucianism. Dao. Chan. Mod. Philos. 2023, 136–151. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y. New Treatise on the Nature of Man, in Six Books of the Zhenyuan Period, Volume 2; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2023; pp. 522–523. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q. The Collected Works of Feng Qi, Volume 1: Knowing the World and Knowing Oneself (Revised Edition); East China Normal University Press: Shanghai, China, 2016; pp. 335–339. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Insani, M.D.; Pratiwi, N.; Muhardjito, M. Higher-order thinking skills based on Marzano taxonomy in basic biology I course. J. Biol. Educ. Indones. (J. Pendidik. Biol. Indones.) 2019, 5, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).