Abstract

This study examines how English newspapers portrayed the First Saudi State (FSS) between 1794 and 1819, focusing on their role in shaping European perceptions. The starting point, 1794, corresponds to the earliest located article mentioning the FSS, while 1819 marks the final reports on its downfall, including the fall of Diriyah in 1818 and the execution of Imam Abdullah bin Saud. While most historical research on the FSS has analyzed travelogs and diplomatic reports, this study highlights newspapers as a contemporaneous and underexplored source. It finds that English press coverage primarily relied on Ottoman and allied sources, often lacking direct Saudi perspectives. As a result, articles frequently framed the FSS as a rebellious religious sect rather than a legitimate state-building effort. Using a qualitative content analysis of 55 randomly selected newspaper articles, the study identifies recurring themes, sources, and biases. Coverage peaked during major geopolitical events, but inaccuracies, sensationalized terminology, and selective reporting reinforced negative stereotypes about the Saudis. By filling a gap in historiography, this research underscores how newspapers shaped public perceptions and foreign policy decisions toward Arabia. It also highlights the broader implications of media dependency in shaping historical narratives.

1. Introduction

The ascension of Imam Muḥammad bin Saud (1727–1765) in Diriyah in 1727 inaugurated a transformative period in Arabian history. This event led to the establishment of the First Saudi State (FSS), a development that gradually reshaped political authority in Arabia. Various historians have offered differing explanations of the FSS’s emergence. Early Saudi historians, in particular, placed religious factors at the forefront, underscoring the influence of Sheikh Muḥammad bin ʿAbdul-Wahhāb’s teachings despite the time gap between the unification of Diriyah under Imam Muḥammad bin Saud and the arrival of the Sheikh (Alareeny 2017; Determann 2014).

Subsequent scholarly works expanded on non-religious factors contributing to the FSS’s consolidation. These included sociopolitical needs, such as pressures on growing urban populations and evolving economic contexts—especially expanded trade routes and integration into global transportation lines (Al-Juhani 2002). The FSS’s ability to ensure the security of trade caravans garnered widespread public support, strengthening its regional influence (Cook 1991; Halevi 2023). Al-Dakhil (2009), for instance, argued that religion served as a unifying force that complemented social and political drivers in establishing a cohesive nation. In more recent discourse, Saudi historians have formally recognized 1727 as the foundational start of Saudi history, reflecting an integration of political, social, and religious considerations (Saudi Press Agency 2021).

Under the leadership of Imam ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (1765–1803), the FSS expanded its reach, culminating in the reign of Imam Saud (1803–1814), when strong administrative and political frameworks were established. However, the Ottoman Empire dismissed the FSS as a mere religious sect, aiming to undermine its political significance and thwart its ambition to unify Arabia under an Arab-led polity. Eventually, Ottoman-led military campaigns advanced into Diriyah in 1818. After a prolonged siege, Imam Abdullah bin Saud (1814–1818) surrendered and was taken to Constantinople and later executed, which marked the end of the FSS (El-Shaafy 1967).

1.1. Research Gap and Questions

Numerous local, regional, and European sources have documented the historical development of the FSS. European materials include governmental records, diplomats’ correspondence, and travel accounts, offering diverse perspectives. Despite extensive scholarship on these foreign writings—especially travelogs, diplomatic reports, and early books referencing the FSS—less attention has been devoted to contemporary newspaper coverage. Yet newspapers were an important medium in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Europe, shaping public consciousness about global events, including those in Arabia (Mussell 2012).

This study addresses the research gap by focusing on how English newspapers portrayed and influenced perceptions of the FSS between the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While prior scholarship has highlighted the impact of the travel literature and official documents, few works have systematically examined newspaper content as a contemporaneous and potentially influential source. Against this background, this study aims to analyze topics related to the FSS covered by English newspapers and explore the reasons behind their interest in reporting on the FSS. Additionally, the study aims to examine how these newspapers portrayed key figures, cities, and events associated with the FSS. It also seeks to identify the broader global and regional factors that influenced English press coverage of the FSS. Finally, the study aims to assess how this coverage shaped or reflected European public perceptions of the FSS.

This study also examines how news items were duplicated and circulated across various British newspapers through practices such as “exchange journalism”, in which identical reports appeared in multiple publications. As many of these reports were drawn from Ottoman sources—often produced in Constantinople, where British diplomatic missions were based—such duplication likely amplified the Ottoman narrative. Consequently, the English press served, perhaps inadvertently, as a vehicle for reproducing Ottoman perspectives on the FSS, often at the expense of more balanced or locally grounded viewpoints. Understanding this process is essential to assessing the mechanisms through which early nineteenth-century British readers formed impressions of Arabia and its political transformations.

1.2. Significance of the Study

By uncovering how the English press covered the FSS, this research contributes new insights into the interplay between media, perceptions, and historical events. Drawing on media dependency theory (Baran and Davis 2010), it underscores how readers in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain relied on newspapers to understand distant developments. Such reliance could have shaped stereotypes, reinforced political agendas, and influenced policy stances toward Arabian affairs. Moreover, this study enriches the understanding of the early Saudi state by integrating a source that has been underutilized in academic analyses—newspapers.

1.3. Outline of the Paper

Following this introduction, the paper surveys the existing literature on European writings about the FSS and the evolution of the English press during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Next, the methodology section describes the qualitative descriptive approach adopted to categorize and analyze newspaper content. The subsequent sections detail the study’s findings, discuss them in light of historical and media theories, and offer conclusions about the image of the FSS in English newspapers and its implications for understanding Saudi and British historical perspectives.

2. Literature Review

This section reviews key contributions that have examined historical sources on the FSS, highlighting how foreign writings—mainly European travel accounts and diplomatic reports—have shaped modern understandings. It then addresses the development and role of the English press at the turn of the nineteenth century, underscoring the gap this research seeks to fill.

2.1. European Writings About the First Saudi State Until 1818

Arabia attracted a steady stream of European explorers, diplomats, and writers beginning in the late eighteenth century, driven partly by rising European political interests worldwide and the geopolitical value of the Middle East. Events such as the French Revolution (1789) and Napoleon’s campaigns—especially the 1798 expedition to Egypt—intensified European power struggles. In pursuit of strategic and commercial interests, prominent states, including France and Britain, sought to monitor developments in Arabia (Ingram 2013; Mens 2020). Consequently, travelers such as Carsten Niebuhr, William George Browne, and Guillaume-Antoine Olivier wrote extensively—albeit often second hand—about the burgeoning FSS.

- Carsten Niebuhr (1733–1815): Among the earliest to reference the expanding Saudi influence during Imam Muḥammad bin Saud’s reign, Niebuhr’s writings were based mainly on information gleaned from individuals outside the state’s borders (Al-ʿUthaymīn 1978). Although his descriptions contained inaccuracies—such as misrepresenting religious dimensions or conflating Sheikh Muḥammad bin ʿAbdul-Wahhāb’s role—Niebuhr’s works formed a baseline for subsequent European authors (Bonacina 2015).

- French Diplomatic and Consular Writings: Figures such as Jean Raymond (Raymond 2003), Corancez (Al-Biqāʿī 2004b; Corancez 2005), and Jean-Baptiste Rousseau (Al-Biqāʿī 2004a) published detailed descriptions of the Saudi state, often influenced by second-hand sources. Their reports underscored the religious aspect of the FSS, characterizing it as a “new sect” or a “reformist” movement, though their interpretations occasionally conflated religious reform with political ambitions (Al-Biqāʿī 2002, 2004b; Hogarth 1904; Seetzen 1805; Raymond 2003).

- Direct Observers: As the FSS expanded, more direct observers emerged. Domingo Badía y Leblich (Ali Bey Al-Abbasi) traveled through Hijaz and performed the Hajj in 1807, offering a firsthand account of the Saudi administration in Mecca (Badía Leblich 1836; Ralli 2009). Likewise, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784–1817) visited Mecca and Madinah in 1814–1815, recording his observations on economic, social, and administrative structures within the FSS. Unlike earlier authors, Burckhardt challenged the notion of a wholly “new religion”, emphasizing a reform-oriented movement that retained its Islamic roots (Al-Shaʿafī 1979; Burckhardt 2003; Hogarth 1904).

Overall, these European accounts helped shape early Western conceptions of the FSS, though they often suffered from factual errors, limited access, or political bias. Nonetheless, they provided a foundational corpus for later historians and researchers interested in the region.

2.2. The English Press at the End of the Eighteenth and Beginning of the Nineteenth Century

Newspapers emerged as a pivotal medium in late eighteenth-century Britain. The so-called “age of enlightenment”, coupled with Britain’s growing global interests, fostered an environment where newspapers enjoyed relatively greater freedom than in other European contexts. By the early nineteenth century, numerous newspapers—ranging from The Times to specialized regional weeklies—had become vital instruments for shaping public opinion (Black 1987; Rudin and Ibbotson 2002; Williams 2009a).

Technological advancements in printing and expanding postal services propelled newspapers’ popularity. Although tri-weekly or weekly publications initially dominated, the demand for timely news spurred the rise in daily morning and evening editions. This proliferation enabled broader social strata to access international coverage (Barker 2014; Botein et al. 1981; Williams 2009b).

Major geopolitical shifts—such as France’s ambitions in the Near East and Britain’s efforts to safeguard routes to India—heightened the British public’s curiosity about Arabia (Barker 2014; Tusan 2016). Newspapers served as windows into distant conflicts and reforms, including coverage of the Saudi expansion. English readers, dependent on newspapers for foreign affairs updates, received periodic news items that interpreted FSS-related developments through British strategic lenses, occasionally revealing editorial biases or reliance on incomplete dispatches.

While travelogs and consular reports have frequently been analyzed, systematic studies that focused on press coverage of the FSS are comparatively few. Yet newspapers were essential mediums for disseminating information among general readers, who had limited access to specialized diplomatic or scholarly works. By examining archived news items—some of which contained maps, sketches, or eyewitness quotes—researchers can gain insight into how the British public perceived and reacted to the rapid changes unfolding in central Arabia.

2.3. Previous Analyses of Foreign Coverage of the First Saudi State

Recent scholarship has noted the importance of contemporary foreign writings on the FSS. Al-Biqāʿī highlighted the earliest French books on the so-called “Wahhabis”, emphasizing their role as seminal sources influencing later European publications (Al-Biqāʿī 2002, 2004b). Likewise, Bonacina (2015) examined how foundational European narratives framed the FSS in religious and political terms. At the same time, Al-ʾAḥmarī (2017) traced the stereotypical images that early Western travelers and consuls projected onto Sheikh Muḥammad bin ʿAbdul-Wahhāb’s call.

Despite these valuable contributions, few studies have systematically scrutinized English newspaper archives from the period in question. Such archives offer a contemporaneous snapshot of how news items about the FSS were selected, relayed, and interpreted for a British readership. Moreover, projects digitizing historical newspapers (e.g., The British Newspaper Archive1 and Times Digital Archive2) have made revisiting and analyzing these sources easier for scholars. This has opened new pathways to understanding the interplay between media narratives and the formation of cultural or political perceptions regarding the FSS.

In sum, the existing body of research attests to a rich array of foreign sources—ranging from the travel literature to diplomatic correspondence—that inform our understanding of the FSS. However, newspapers, as a critical medium of public discourse, remain a largely underexplored resource. Building on both historical studies of European writings and contemporary inquiries into the shaping of public perceptions, this research adopts a focused approach to newspaper content, thereby filling a substantial gap in the historiography of the FSS and its global resonance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Rationale

This study adopted a qualitative descriptive approach to explore how English newspapers portrayed the (FSS) between 1794 and 1819. Building on media and historical studies, the research aims to describe, categorize, and analyze the content of newspaper articles relevant to the FSS during this period. This design aligns with the study’s primary questions:

- What topics related to the FSS were covered?

- What sources of information were used?

- Who were the historical figures mentioned?

- Which Saudi cities and regions were mentioned?

- How was the information evaluated?

- What technical features characterized the coverage of the FSS?

- What journalistic forms were employed?

3.2. Data Collection

A comprehensive search was conducted on The British Newspaper Archive to identify all items referring to the FSS within the study’s timeframe, 1794–1819. This period was selected based on the earliest located article in 1794, which coincided with the FSS’s growing regional influence and expansion into key territories like Al-Ahsa, and 1819, which marked the final reports on the fall of Diriyah 1818 and execution of Imam Abdullah bin Saud, signifying the official end of the FSS. Keywords such as “Wahhabees”, “Saud”, “Diriyah”, and “Nejd” were used to locate relevant articles, yielding 275 news items directly referencing events, figures, or regions associated with the FSS.

Given the technological constraints of the time, certain articles appeared in multiple newspapers as syndicated reports, leading to potential duplication. To ensure accuracy, items with identical wording and source attributions were cross-checked, documented, and flagged as duplicates to prevent double counting in the final analysis. By examining this timeframe, the study captures both the rise and decline of the FSS as reported in contemporary British media, offering insights into how European perceptions evolved over time.

3.3. Sample Selection

Analyzing every piece out of the total 275 items in depth was beyond the scope of this study owing to resource and time constraints. Consequently, a simple random sample of approximately 20% (n = 55) of the articles was selected via Microsoft Excel’s randomization tool (Supplementary Materials S1). This sampling percentage was chosen to balance manageability with representativeness. A brief review of article distribution across key events (e.g., the FSS’s expansion in 1803, assassination of Imam ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz in 1804, and Ottoman campaigns in 1811 and 1818) confirmed that the random sample encompassed coverage from these pivotal years.

3.4. Instrument Development

A content analysis form was created to systematize the examination of newspaper items. Drawing upon the relevant literature, prior research on historical media coverage, and expert consultation, the initial form was refined to ensure it measured the intended constructs. The final form contained 21 statements divided into three domains:

- Journalistic features (e.g., headline style, type of source, and presence of editorial bias)

- Historical information (e.g., key figures, places, and events)

- Article direction (i.e., tone or stance regarding the FSS: supportive, hostile, or neutral)

3.5. Data Analysis Procedure

Each of the 55 sampled articles was coded using the content analysis form. To track trends and patterns, descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were computed for each domain. Additionally, cross-tabulations were performed to observe relationships between certain variables (e.g., tone of coverage vs. date of publication). The following steps were consistently applied:

- Initial screening: Articles were read in full to confirm relevance and clarity.

- Coding: Each article’s features were categorized according to the 21-item form.

- Tabulation: The coded data were entered into Microsoft Excel for frequency and percentage calculations.

- Charting: Visual representations (e.g., bar charts and line graphs) were generated to illustrate coverage trends over time.

3.6. Reliability and Validity

3.6.1. Reliability

To ensure consistent application of the content analysis form, two authors independently analyzed a subset of 20 articles randomly chosen from the sample. Holsti’s Reliability Coefficient was then calculated:

where M = number of agreed-upon coding decisions, N1 = total coding decisions by the first author, and N2 = total coding decisions by the second author.

Reliability = 2M/(N1 + N2)

The coefficient reached 0.95 (95%) (Table 1), indicating a high level of coder agreement. Given that a reliability coefficient of 80% or above is generally considered acceptable in content analysis, the form was deemed highly reliable for this study.

Table 1.

Holsti’s reliability coefficient analysis.

3.6.2. Validity

Face and content validity were addressed by refining the analysis form with expert feedback from historians and media specialists. Their input ensured that each item corresponded to the study’s objectives and accurately reflected relevant historical and journalistic dimensions. This iterative process helped confirm that the instrument measured what it was intended to measure.

3.7. Limitations

While this study offers important insights, several limitations should be acknowledged:

- Archival completeness: The British Newspaper Archive, although extensive, may not encompass all relevant publications from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Missing or deteriorated issues could limit the comprehensiveness of the dataset and affect the breadth of historical insight.

- Sample size: Owing to resource and time constraints, only 20% of the collected items were analyzed in detail. Although random sampling was employed to enhance representativeness, certain nuances or perspectives from the remaining articles could remain undiscovered.

- Duplicate content: Common syndication practices of that era led to repeated articles across multiple outlets. Although this study flagged identical texts to avoid direct duplication, overlapping content might still influence the perceived frequency or prominence of certain stories.

- Textual degradation and digitization errors: Some newspaper pages were partially illegible owing to faded print, ink stains, or typographical wear intrinsic to older printing methods. Additionally, the digitization process used by the archive might have introduced spelling inconsistencies or misread text, occasionally hindering keyword-based searches. As a result, several potentially relevant items might have been overlooked, which could have affected the scope and representativeness of the final sample.

3.8. Ethical and Procedural Considerations

All collected materials are in the public domain or accessible under The British Newspaper Archive’s licensing arrangements. No ethical clearance was required as the study did not involve human participants or sensitive personal data. The digital metadata of each article (date, publication, and volume/issue numbers) were carefully documented to maintain a transparent audit trail.

4. Results

4.1. Frequency and Distribution of Coverage

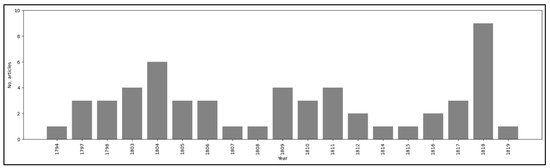

According to (Figure 1), English newspapers began regularly reporting on the FSS in 1794, following its extension of influence into Al-Ahsa in eastern Arabia—a region of considerable strategic and economic importance. This period likewise marked the onset of FSS expansion northward and westward toward the Hijaz—developments that had significant repercussions for neighboring territories.

Figure 1.

Articles by year.

The steady coverage in subsequent years suggests a pronounced editorial interest in events related to the FSS. Reporting intensified during major milestones: in 1803, when Saudi forces entered Mecca for the first time; in 1804, coinciding with the assassination of an Imam; in 1811, upon the initial Ottoman campaigns against the FSS; and in 1818, when Diriyah was besieged and fell, which prompted a surge of nine articles.

These spikes indicate that the FSS attracted substantial international attention during critical moments.

Furthermore, our analysis (Supplementary Materials S2) reveals variations in how individual newspapers treated FSS-related news. Of the 55 articles published across 31 newspapers, Sun and The Caledonian Mercury printed the highest number—five articles each. The Times, The Morning Chronicle, Saint James’s Chronicle, and The Evening Post followed with three articles each. Meanwhile, The Observer, Saunders’ Newsletter and Daily Advertiser, Hull Advertiser, Hampshire Chronicle, Commercial Chronicle London, Calcutta Gazette, Bombay Gazette, Aberdeen Journal, and General Advertiser each featured two articles. The remaining 17 newspapers published only one article apiece. Overall, 69% of these newspapers exhibited considerable interest in Arabian affairs—particularly in the FSS—while 31% displayed relatively low levels of coverage.

4.2. Topics Related to the FSS

Analysis of the sampled articles (Supplementary Materials S3) reveals that English newspapers covered a diverse array of topics concerning the FSS. These topics encompassed religious, political, and military dimensions:

- –

- The reform call and its religious implications;

- –

- FSS expansion across Arabia;

- –

- The assassination of Imam ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz;

- –

- Relations between the FSS and Qawasim;

- –

- The Ottoman Empire’s war efforts against the Saudis;

- –

- Preparations made by the Ottoman Empire for military expeditions from Baghdad, the Levant, and Egypt;

- –

- Details of the Ottoman campaigns dispatched from Egypt (e.g., itineraries and clashes in Wadi Al-Safra, Turuba, Basil, Mawiya, Al-Rass, and Al-Qassim);

- –

- The siege of Diriyah and ultimate downfall of the FSS.

These recurring themes underscore the English press’ focus on conflicts, territorial expansions, and pivotal events that shaped the geopolitical landscape of Arabia.

4.3. Information Sources

Most FSS-related news items were drawn from foreign correspondents and news agencies based in Ottoman cities such as Cairo, Constantinople, and Aleppo. Several articles also cited European cities like Milan and Florence, such as reports in the Aberdeen Journal and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland (15 October 1798, p. 3), Evening Mail (5 October 1798, p. 4), The Times (8 October 1798, p. 2), and The Morning Chronicle (12 December 1818, p. 2). These papers often used vague phrases such as: “According to letters received from Aleppo…”, “The latest dispatches from Constantinople…”, or “Extracted from a report printed in Milan”, without specifying authors or eyewitnesses. The frequent reliance on the passive voice and absence of named informants indicate a lack of direct access and over-reliance on intermediary narratives.

For instance, a dispatch in The Times (2 December 1811) stated the following: information was transmitted through Constantinople, where letters from Syria described disturbances in the interior. A similar passage appeared days later in The Calcutta Gazette, suggesting that the content had been republished verbatim, a common feature of “exchange journalism”. This duplication extended to Indian newspapers, particularly those based in Madras and Calcutta, which often cited “ships arriving from Mecca” as sources—although these were rarely verified or expanded upon. Such repetition across geographically distant outlets exemplifies how British imperial networks helped circulate and amplify a narrow, often Ottoman-aligned portrayal of the FSS.

These patterns suggest a highly centralized model of news production and dissemination, where Ottoman accounts—particularly from Constantinople—dominated the information available to the English-speaking world. In the absence of Saudi voices or direct British reporting from within the FSS territories, this structure allowed subjective and politically influenced narratives to become entrenched across multiple regions.

4.4. Historical Figures

English newspapers frequently mentioned leading FSS figures (Imam ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, Imam Saud, and Imam Abdullah) using terms such as “leader” or “chief”, rather than their formal titles of “Imam”. In contrast, non-Saudi actors often received official military or political titles (e.g., “Imam of Muscat”, “Pasha of Egypt”, “Ibrahim Pasha”).

Additionally, misspellings and inconsistencies abounded:

- Sheikh Muḥammad bin ʿAbdul-Wahhāb: Often simply called “ʿAbdul-Wahhāb”, sometimes with varied transliterations or spellings.

- Prince Fīṣal bin Saud: Mentioned sporadically in connection with the Battle of Turuba, but sometimes with incomplete or incorrect details.

- Distorted assassination reports: Several articles erroneously conflated the assassination of Imam ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz with that of “ʿAbdul-Wahhāb”, introducing confusion about which figure was actually targeted.

- The spelling of Saudi figures was not always accurate; some names, such as ʿAbdul-Wahhāb, Wahhabis, and Abdullah bin Saud, were misspelled in different ways.

Certain negative labels consistently emerged—terms such as “insurgents”, “banditti”, and “fanatics”—indicating a prevalent negative slant in portraying the Saudis.

4.5. Cities and Regions

Articles mentioned a range of locations within the FSS’ dominion—Najd, Diriyah, Mecca, Madinah, Jeddah, Mawiya, Buraidah, Unayzah, Qassim, Al-Rass, Al-Ahsa, Qatif, Turuba, Taif, Zulfi, Hijaz, and Al-Uyaynah. Spelling variations were common across newspapers, whereas well-known sites outside Arabia (e.g., Egypt, Aleppo, Baghdad, Yemen, Persia, Arabian Gulf, Red Sea, and the Gulf of Suez) were typically spelled consistently and more accurately.

This contrast suggests that less familiar Arabian places were subject to greater transliteration errors, which may reflect limited geographical knowledge among British journalists.

4.6. Information Evaluation

When content accuracy was reviewed, several issues surfaced:

- Misinterpretations of political developments: Newspapers conflated the reform call with the formation of the FSS, referring to the Saudis uniformly as “Wahhabis” and denying statehood by calling them a “sect” (Caledonian Mercury, 15 February 1819, p. 2).

- Inaccuracies about the state’s end: Some reports claimed Imam Abdullah escaped or was captured via a “secret plan” by Ibrahim Pasha, rather than surrendering to save Diriyah (Weekly Dispatch, 27 December 1818, p. 1).

- Distortions of religious context: Allegations of a “new religion” or describing Sheikh Muḥammad bin ʿAbdul-Wahhāb as an “alleged prophet” reflect misunderstandings or deliberate sensationalism (Caledonian Mercury, 3 May 1794, p. 3).

- Event–place mismatches: Turuba was occasionally labeled a “major” (Sun, 1 January 1816, p. 1) or “inner” capital (Commercial Chronicle, 2 January 1816, p. 4), which hinted at confusion between administrative centers.

- Personal and chronological errors: Recurring mistakes in the narratives of Imam ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz’s assassination (e.g., attributing it to Sheikh Muḥammad bin ʿAbdul-Wahhāb) and misinformation about Prince Fīṣal bin Saud’s movements (Calcutta Gazette, 1 June 1815, p. 10)

- Explicit bias: Terms such as “unpleasant news” (Caledonian Mercury, 10 July 1806a, p. 4) or “disappointing” (Caledonian Mercury, 28 August 1806b, p. 2) expansions highlight some newspapers’ negative stances toward Saudi advances, framing the FSS as a rebellious or threatening entity (Caledonian Mercury, 10 July 1806a, p. 4; The Observer, 18 March 1804, p. 2; Bombay Courier, 10 March 1818, p. 4).3

- The results showed that certain topics—particularly the early reform movement, the expansion of Saudi authority, the entry into Mecca and Medina, and the supervision of Hajj—were consistently portrayed in negative terms. These topics appeared more frequently in hostile or alarmist contexts compared to others, reflecting a recurring pattern of biased representation.

- Repetitive syndication: Articles were frequently duplicated verbatim across outlets, magnifying the spread of inaccuracies (Aberdeen Journal and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland, 15 October 1798, p. 3; Evening Mail, 5 October 1798, p. 4; The Times, 8 October 1798, p. 2; London Chronicle, 19 December 1817, p. 1; Inverness Courier, 25 December 1817, p. 2).

A handful of articles praised the security and stability under the FSS, noting that foreign travelers could cross Arabian territories safely (Oracle and the Daily Advertiser, 14 October 1803, p. 1; Star, 14 October 1803, p. 2).

4.7. Technical Features of English Newspaper Coverage

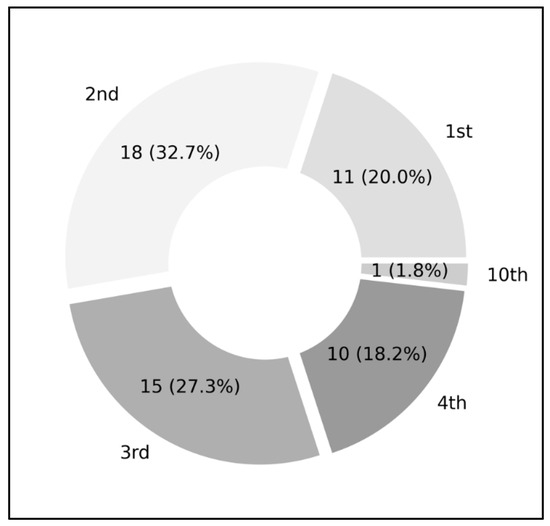

According to Figure 2, most of the 55 analyzed articles appeared on key pages of newspapers, reflecting editorial interest: second page—32.7%; third page—27.3%; first page—20.0%; fourth page—18.2%; and tenth page—1.8%.

Figure 2.

News location on newspaper pages.

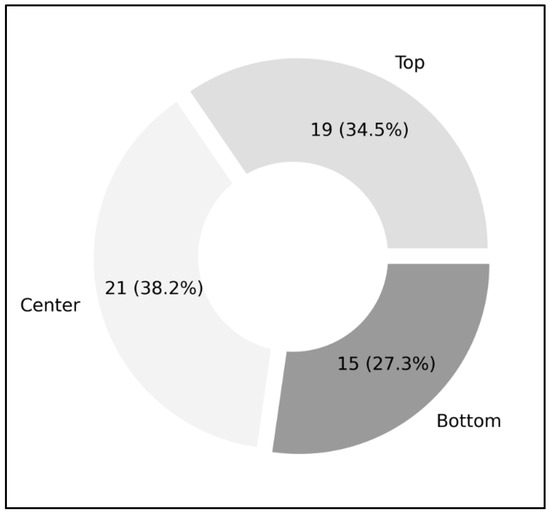

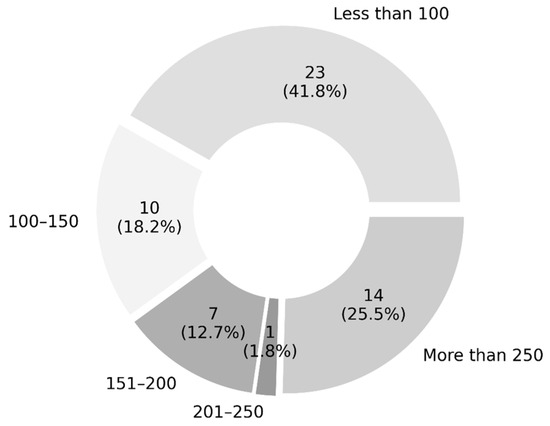

As illustrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4, most articles (72.7%) were printed near the top or center of the page, suggesting a relatively prominent placement. However, the length of coverage tended to be short, with telegram-like news (under 150 words) predominating. Only 14 articles (25.45%) exceeded 250 words, limiting in-depth analysis or detailed background on FSS events.

Figure 3.

Placement of articles on a page.

Figure 4.

Word counts.

The brevity of newspaper articles often constrained the depth and accuracy of reporting on the FSS. Limited space forced journalists to oversimplify events, prioritize dramatic aspects, and omit critical historical and cultural contexts, which might have led to skewed representations. Research on media framing has suggested that shorter articles tend to sacrifice nuance for readability, influencing public perceptions through selective reporting (Galtung and Holmboe Ruge 1965; Tuchman 1978). These constraints likely shaped how European audiences understood the FSS, reinforcing stereotypes or partial narratives rather than offering a balanced historical account.

4.8. Journalistic Forms

The prevalence of the straight news format in most articles, focusing solely on factual statements addressing “who, what, when, where”, limited their ability to provide deeper context or analysis. While this format might have contributed to a sense of objectivity, it also meant that reporting often lacked the necessary depth to explore the complexities of the FSS. In contrast, the subset of interpretive articles, which offered opinions or assessments, was largely shaped by Ottoman or allied sources without incorporating Saudi perspectives. This selective framing reinforced a one-sided portrayal of events, leading to skewed narratives that aligned with the interests of dominant geopolitical powers.

The absence of multi-perspective narratives significantly impacted the role of these articles in shaping European perceptions. Without diverse viewpoints, English newspapers presented a filtered version of events that often framed the FSS through the lens of Ottoman adversaries, portraying it as a disruptive force rather than a legitimate political entity. This contributed to stereotypes depicting the Saudis as rebels or extremists rather than as leaders of a structured state with its own political, religious, and social dynamics. Such narratives, once embedded in public discourse, became self-reinforcing, influencing both contemporary European policies toward the region and long-term historical interpretations. When reporting lacks balance and relies predominantly on one source, it fosters a biased worldview that can persist over time (Entman 1993). Thus, the reliance on Ottoman sources not only diminished the credibility of these articles but also played a crucial role in constructing a lasting—and often inaccurate—image of the FSS in European consciousness.

4.9. Concluding Remarks on Results

In summary, the data reveal both sustained editorial interest in the FSS—evidenced by the prominence of news articles and recurring reports—and substantial inaccuracies or biases in portrayal. The reform call and expansion of the FSS elicited varied coverage in the English press, but consistent misrepresentations, transliteration errors, and reliance on indirect sources limited factual precision. While some newspapers acknowledged the security and order established in areas under FSS control, the dominant narrative framed the Saudis as a religious “sect” challenging Ottoman authority.

These findings provide a foundation for analyzing how and why such patterns of coverage emerged, exploring influences such as British strategic interests, editorial norms, and the broader European perception of Arabian affairs. The subsequent discussion will delve into these aspects more deeply, examining how newspapers shaped public opinion and reflecting on the broader implications of media dependency during the early nineteenth century.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the portrayal of the (FSS) in a sample of English newspaper articles, assess the accuracy of the information conveyed, and explore how these accounts shaped broader perceptions of the FSS. The results revealed both high public interest in the FSS—evidenced by frequent coverage of its religious, political, and military aspects—and a lack of reliable sources, as evidenced by inconsistencies, errors, and negative framing in the news items.

5.1. Main Findings and Interpretations

The findings demonstrate that newspapers generally prioritized novelty and conflict in selecting stories about the FSS. Topics ranged from the assassination of Imam ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz to various military engagements and the eventual siege of Diriyah. These themes align with conventional news values, where disputes, wars, and political tension attract readership and editorial attention. This pattern is consistent with existing historiographical evidence indicating European powers’ strategic interest in Arabia owing to competing trade routes and broader geopolitical concerns.

However, substantial inaccuracies emerged in the portrayal of events and figures. Newspapers often relied on unnamed foreign correspondents and official military or diplomatic sources, without consulting any direct Saudi sources. While such reliance on intermediaries was common in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century journalism, it introduced biases and distortions—a phenomenon also noted in earlier works by Al-Biqāʿī and Al-ʾAḥmarī, which highlighted how Niebuhr and Corancez gathered information indirectly, leading to misunderstandings about the FSS’ political and religious context.

The study observed that the information sources cited by various newspapers were primarily located in Constantinople—the capital of the Ottoman Empire—and other key cities within its provinces, including Cairo, Alexandria, Aleppo, Basra, and Baghdad. Several factors may explain this pattern. These Ottoman cities functioned as hubs for diplomatic missions, consular presence, and foreign commercial activities, particularly due to the growing interests of European powers and the operations of the British East India Company in the region (Louis 1967; Çelik 1992). Diplomats based in these cities often maintained close ties with Ottoman administrative officials and served as intermediaries between local developments and international news outlets. It is therefore plausible that many of the reports published in the British press were influenced, if not directly shaped, by diplomatic correspondence rather than independent journalism. A historical parallel can be found in French coverage of the FSS, which relied heavily on reports from French consular agents.

The lack of Saudi sources further indicates that British correspondents did not have direct access to FSS territories. Although several foreign individuals—including Renaud, Badía, and Burckhardt—traveled to the region during this period, they did not act as journalists. Rather, they served as diplomatic envoys or researchers, and their writings were not published until after the fall of the FSS. Additionally, the absence of a local print culture limited the availability of indigenous sources, leaving foreign media reliant on external, often politically influenced, narratives.

5.2. The Absence of Direct Contact and Its Consequences

A central observation is that no English newspaper in the sample referenced direct interviews with or statements from FSS leaders. Instead, reporters frequently cited intelligence networks, letters, or other publications, such as those in Hamburg or Florence. This indirect approach fostered one-sided narratives, often painting the Saudis as “rebels” or “fanatics”. Such negative epithets not only reinforced stereotypical views but also obscured the nuanced political and religious reforms underway (Aberdeen Journal and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland, 15 October 1798, p. 3; Evening Mail, 5 October 1798, p. 4; The Times, 8 October 1798, p. 2).

The timing of publication played a role in perpetuating these inaccuracies. The study shows that more balanced or firsthand European accounts—such as those of Badía (Ali Bey) and Johann Ludwig Burckhardt—were either published shortly before the FSS fell or released afterward, which reduced their influence on shaping real-time perceptions. By the time these more impartial narratives reached the European public, misleading initial portrayals were already embedded in collective consciousness.

It is also observed that the absence of a Saudi perspective contributed significantly to the distortion of British understanding of regional developments. At the time, there were no Saudi media outlets capable of presenting or defending the image of the FSS. Printing technology had not yet reached the region, and foreign newspapers were neither accessible nor known within FSS territories, making it nearly impossible for any direct response or counter-narrative to emerge.

Local writings about the FSS were not published until the twentieth century, and even then, they remained in Arabic and have rarely been translated into other languages. As a result, the image propagated by foreign press outlets remained largely unchallenged in subsequent scholarship. While considerable academic attention has been given to travel accounts, official reports, and early books, contemporary English newspaper coverage of the FSS has received comparatively limited scholarly analysis, particularly in terms of its framing and editorial tone.

5.3. Confusions Between Religious Reform and State Formation

A further point highlighted by this research is the frequent conflation of the reform call led by Sheikh Muḥammad bin ʿAbdul-Wahhāb with the establishment of the FSS under Imam Muḥammad bin Saud. Many articles mistakenly viewed the FSS as a purely religious “sect”, misunderstanding its political and administrative structures. This confusion mirrors earlier foreign writings where travelers and diplomats often collapsed religious reform and political unification into a single, oversimplified narrative. Consequently, Imam Muḥammad bin Saud was rarely mentioned, even though he played a pivotal role, partly because the news coverage rose to prominence only after his death, when the state’s expansion caught the attention of international observers.

5.4. Negative Framing and Its Impact

The prevalence of terms such as “insurgents”, “banditti”, and “fanatics” in reference to the Saudi leadership indicates a deliberate framing that skewed readers’ perspectives toward hostility and suspicion. Such language not only reflected editorial or political biases but could also resonate with broader European concerns about maintaining stable trade routes and containing perceived threats to Ottoman authority. As a result, readers were often left with a simplified and adversarial image of the FSS, perpetuating a narrative of rebellion against the Ottomans rather than legitimate state-building efforts.

Bias against the FSS was evident in the British media’s treatment of issues aligned with Ottoman concerns. During its conflict with the FSS, the Ottoman Empire worked to depict it as a radical religious movement threatening both Islam and imperial authority, while downplaying the political transformations taking place in Arabia. The Saudi capture of Mecca and Medina—undermining Ottoman religious legitimacy—further escalated tensions, and this dynamic was mirrored in British press coverage of the reform movement, which often appeared negative and reductive.

The British press frequently echoed the narrative promoted by Ottoman sources, portraying Saudi advances—such as the entry into the Holy Cities and administration of the Hajj—in an unfavorable light. These reports were generally unverified and lacked independent journalistic inquiry. While the media may have reflected broader geopolitical alignments and imperial interests, it is unclear whether it directly influenced British foreign policy or merely reinforced prevailing political narratives.

5.5. Alignment with Previous Studies

These observations are consistent with earlier scholarship noting the general confusion and inaccuracies in first-wave European sources about the FSS. Researchers such as Al-Biqāʿī and Al-ʾAḥmarī have documented how reliance on intermediaries contributed to persistent errors, particularly in identifying key figures or clarifying the interplay between reformist doctrine and political governance. Meanwhile, the belated dissemination of more informed works—by travelers who had first-hand exposure to FSS territories—limited their ability to challenge entrenched, skewed perceptions in real time.

5.6. Implications and Future Directions

The findings underscore the critical role newspapers play in shaping international opinion, especially in periods when editorial norms favor urgent reporting over verified accuracy. Readers at the time relied heavily on such newspapers for foreign affairs news—a dependency that could magnify the impact of any misinformation. This case study thus illustrates how media practices in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries influenced public discourse, diplomatic relations, and policy stances.

Journalists often employed the passive voice, concealing or omitting the original informants’ names. Such reliance on second-hand accounts did not identify local sources and introduced additional layers of ambiguity. References to newspapers in Hamburg, Florence, and Milan highlighted the transnational flow of FSS-related news, which signifies that coverage extended well beyond the immediate region. Moreover, Indian newspapers frequently cited “ships coming from Mecca”, which illustrates the wide geographic range over which information circulated.

Moving forward, more systematic comparisons between contemporary Saudi records (for instance, local manuscripts and chronicles) and European news coverage would help reveal the full extent of these distortions. Researchers could also investigate whether similar inaccuracies persisted in later foreign reporting on the Second and Third Saudi States. To facilitate more comprehensive comparisons, additional steps include the following:

- Future research should focus on comparing the coverage provided by British newspapers to investigate variations in editorial policies and the influence of political factors. Examining how the lack of Saudi voices has shaped British perceptions is crucial, as this will aid in understanding the prevailing one-sided narrative. Furthermore, exploring alternative sources, such as diplomatic records and local accounts, may facilitate the reconstruction of a more balanced perspective. By broadening the scope of analysis, researchers will gain deeper insights into the processes by which historical narratives have been constructed and disseminated within the international press. It is important to emphasize that such research does not aim to reconstruct Saudi history itself, but rather to examine how foreign media shaped international perceptions of the FSS during its formative years.

- Digital archiving of local sources: Research institutions are encouraged to digitize further local Saudi sources—such as manuscripts, chronicles, and administrative documents—pertinent to the FSS. Making these materials readily accessible, complete with translation and text-search capabilities, would enable more precise cross-referencing against foreign newspaper narratives.

- Exploring additional foreign source: Future studies could examine how other European or regional outlets covered the FSS. Such comparative inquiry might reveal consistent patterns of reporting or expose varying national biases and editorial norms.

- Comparative analyses of Saudi and foreign accounts: Investigating local Saudi records (e.g., writings by Ibn Ghannām or Ibn Bishr) in tandem with concurrent English or French newspaper articles could yield deeper insight into discrepancies, omissions, and misinterpretations that shaped readers’ understanding of the FSS.

- Longitudinal evolution of the FSS image: Researchers might trace how portrayals of the FSS shifted over time, transitioning from early English newspapers to later nineteenth-century European and American publications. Evaluating changes in terminology, tone, and thematic focus could illuminate broader trends in international attitudes toward the Arabian Peninsula.

By adopting these measures, future scholarship can more accurately assess the historical narrative of the FSS and better understand the complex interplay between media sources, political agendas, and public perception in the formative stages of modern Middle Eastern history.

6. Conclusions

This study’s examination of English newspaper coverage from 1794 to 1819 reveals that incomplete sources, editorial biases, and reliance on intermediaries led to a predominantly negative and often erroneous portrayal of the FSS. Despite the FSS’s growing regional significance, its foundational leader (Imam Muḥammad bin Saud) was barely mentioned, and the reform call remained conflated with state-building efforts. The few balanced perspectives that did exist reached European audiences too late to correct prevailing misconceptions.

By analyzing newspaper articles as contemporaneous accounts—rather than retrospectively written travelogs or diplomatic reports—this study bridges an essential gap in historiography. It demonstrates how journalism, even in its early forms, had a profound influence on international perceptions of distant regions. Consequently, understanding the extent and nature of media coverage becomes crucial for interpreting European attitudes toward the FSS, particularly regarding religious and political reform in Arabia.

Overall, newspapers played a crucial role in informing (and sometimes misinforming) the public about the FSS during a period of substantial geopolitical change. While coverage often lacked depth and accuracy, its influence on shaping collective perceptions was profound. Recognizing these historical patterns underscores the enduring power of the press and offers lessons for contemporary discussions on media reliability, cultural representation, and the politics of information.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/histories5020022/s1, Supplementary Materials S1: The research sample list; Supplementary Materials S2: Number of articles according to newspaper; Supplementary Materials S3: Topics by year.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A. and S.B.G.; Methodology, M.A.A. and S.B.G.; Validation, M.A.A., S.B.G. and N.R.A.-R.; Formal Analysis, M.A.A. and S.B.G.; Investigation M.A.A.; Resources, M.A.A. and N.R.A.-R.; Data Curation, M.A.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.B.G. and N.R.A.-R.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.A.A.; Visualization, M.A.A.; Supervision, M.A.A.; Project Administration, M.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, and Jouf University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FFS | First Saudi State |

Notes

| 1 | See https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk (accessed on 10 June 2024). |

| 2 | See https://www.gale.com/intl/c/the-times-digital-archive (accessed on 15 May 2024). |

| 3 | Regarding this, American newspapers were publishing similar news: Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 May 1794; Poughkeepsie Journal, 4 June 1794; Farmer’s Library, 6 May 1794, and Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 10 May 1794. |

References

- Alareeny, Abdulrahman. 2017. The start of Sheikh Muhammad Ibn Abd Al-Wahhab’s Dawa “call” and his move from Huraymila to Al-‘Uyayna and then Al-Diriyah: A historical and comparative study. Journal of Social and Humanities 10: 1647–710. (In Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Al-ʾAḥmarī, Abdulrahman. 2017. Stereotype image of the reform movement of Ash-Shaikh Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab in Western writings about Arabia 1799–1848. Journal of the Saudi Historical Society 18: 153–98. (In Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Al-Biqāʿī, Muhammad. 2002. Louis Alexandre Olivier de Corancez and his book Histoire des Wahabis, depuis leur origine jusqu’a la fin de 1809. Journal of the Saudi Historical Society 3: 165–98. (In Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Al-Biqāʿī, Muhammad. 2004a. Jean-Baptiste-Louis-Jacques Rousseau and his book. Al-ʿArab 40: 227–52. (In Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Al-Biqāʿī, Muhammad. 2004b. The first French books about Sheikh Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab’s reform call. Al-Dārah Journal 30: 9–34. (In Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dakhil, Khalid S. 2009. Wahhabism as an ideology of state formation. In Religion and Politics in Saudi Arabia: Wahhabism and the State. Edited by Mohammed Ayoob and Hasan Kosebalaban. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, pp. 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Juhany, Uwaidah M. 2002. Najd Before the Salafi Reform Movement: Social, Political and Religious Conditions During the Three Centuries Preceding the Rise of the Saudi State. Reading: Ithaca Press. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shaʿafī, Muhammad. 1979. Burckhardt’s books as a historical and economical source of the first Saudi state. Historical Sources of Arabia 2: 461. (In Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Al-ʿUthaymīn, Abdullah. 1978. Niebuhr and the call of Sheikh Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab. Journal of Social Science College 2: 175–83. (In Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Badía Leblich, Domingo. 1836. Viajes de Ali Bey El Abbassi por Africa Y Asia, tomo II (Spanish). Valencia: Mallén y Sobrinos. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, Stanley J., and Dennis K. Davis. 2010. Mass Communication Theory, Foundation, Ferment and Future. Independence: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Hannah. 2014. Newspapers and English Society 1695–1855. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Jeremy. 1987. The English Press in Eighteenth Century. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacina, Giovanni. 2015. The Wahhabis Seen Through European Eyes (1772–1830). Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Botein, Stephen, Jack R. Censer, and Harriet Ritvo. 1981. The periodical press in eighteenth-century English and French society: A cross-cultural approach. Comparative Studies in Society and History 23: 464–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, J. L. 2003. Notes on the Bedouins & Wahábys; Translated by Abdullah Al-ʿUthaymīn. Riyadh: King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives, pp. 22–26. (In Arabic)

- Cook, Michael. 1991. The expansion of the first Saudi state: The case of Washm. In The Islamic World from Classical to Modern Times: Essays in Honor of Bernard Lewis. Edited by Clifford Edmund Bosworth, Charles Issawi, Roger Savory and Abraham L. Udovitch. Princeton: Darwin Press, pp. 678–79. [Google Scholar]

- Corancez, L. A. 2005. Histoire des Wahabis, Depuis leur Origine Jusqu’a la fin de 1809; Translated by Muhammad Al-Biqāʿī, and Ibrahim Al-Balawī. Riyadh: King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives. (In Arabic)

- Çelik, Zeynep. 1992. Displaying the Orient: Architecture of Islam at Nineteenth-Century World’s Fairs. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Determann, Jörg Matthias. 2014. Historiography in Saudi Arabia: Globalization and the State in the Middle East. London and New York: Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shaafy, Muhammad. 1967. The First Saudi State in Arabia (with Special Reference to Its Administrative, Military and Economic Features) in the Light of Unpublished Materials from Arabic and European Sources. Ph.D. thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. [unpublished]. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtung, Johan, and Mari Holmboe Ruge. 1965. The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the Congo, Cuba, and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of Peace Research 2: 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevi, Leor. 2023. Arabians for guns: Wahhabi matchlocks, world trade, and the rise of the first Saudi state. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 33: 401–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, David G. 1904. The Penetration of Arabia: A Record of the Development of Western Knowledge Concerning the Arabian Peninsula. Brooklyn: F. A. Stokes. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, Edward. 2013. In Defence of British India: Great Britain in the Middle East, 1775–1842. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, William Roger. 1967. The British Empire in the Middle East, 1945–1951. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mens, Jay. 2020. “From the Indus to Constantinople”: The Napoleonic Wars and the evolution of a “Middle East”, 1798–1809. Asian Affairs 51: 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussell, James. 2012. The Nineteenth-Century Press in the Digital Age. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ralli, Augustus. 2009. Christians at Mecca; Translated by Ḥasan Ghazāla. Rev. Mahmood Al-Suryānī, and Merag Murzā. Riyadh: King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives, pp. 5–46. (In Arabic)

- Raymond, Jean. 2003. Mémoire sur l’origine des Wahabys; Translated by Muhammad Al-Biqāʿī. Riyadh: King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives. (In Arabic)

- Rudin, Richard, and Trevor Ibbotson. 2002. An Introduction to Journalism: Essential Techniques and Background Knowledge. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Press Agency. 2021. Royal Order: February 22 of Every Year Shall Be Designated to Mark Commemoration of Saudi State Founding Under Founding Day Name. June 24. Available online: https://www.spa.gov.sa/2324647 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Seetzen, Ulrich Jasper. 1805. Auszug aus dem briefe des Hrn. Reinaud an Dr. Seetzen. In Monatliche Correspondenz zur Beförderung der Erd und Himmels-Kunde, XII. pp. 234–46. Available online: https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/rsc/viewer/jportal_derivate_00237208/Monatliche_Correspondenz_130168688_12_1805_0245.tif (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Tuchman, Gaye. 1978. Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tusan, Michelle. 2016. Empire and the Periodical Press. In The Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers. Edited by Andrew King, Alexis Easley and John Morton. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Kevin. 2009a. The first newspapers. In Read All About It! A History of the British Newspaper. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Kevin. 2009b. Knowledge and power. In Read All About It! A History of the British Newspaper. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).