Abstract

In the Spanish Empire, the term mestizo/mestiza denoted, overwhelmingly, people of so-called “mixed” European and indigenous ancestry, but there existed also some regional adaptations with differing genealogies such as the mestizos de sangley in the Philippines. The article traces some developments of the application and racialization of the term mestizo shortly after the end of the Spanish Empire in the Philippines under U.S. rule. It will look at photographs that were taken in by Dean Worcester, secretary of the interior, and his staff, in order to apply and develop theories of the biologist racism, which in the early twentieth century was en vogue all over the globe. Worcester and his crew took the photographs during their expeditions and used them to illustrate their hypotheses about racialized taxonomies, adapting and further developing Spanish colonial ideas. I will contrast them with a photograph from a local studio in Mindanao. The photographs stem from the photographic collection of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne, Germany.

1. Introduction

This article engages with an especially problematic kind of photography: anthropometric “types”, mostly elaborated by (sometimes self-declared) anthropologists who used these stereotypical and degrading pictures of human beings to support and develop theories of the so-called “scientific” racism—which from today’s point of view has nothing scientific about it.1 In their majority, these anthropometric types display indigenous peoples (or Africans outside Africa—(Ermakoff 2004). These types of photographs have been amply studied for different parts of the globe (Poole [1997] 2021; Justnik 2012; Hight and Sampson 2002; Blumauer 2014; Calvo and Semper-Puig 2023; Jordán 2016; Onken 2015; Reinert 2017; Jäger 2006) including the Philippines (Cañete 2008; Rice 2014; Rohde-Enslin 1999; Vergara 1995; Fernandez 2023; Best 2023; Halpern 2018; van Muijzenberg 2008; Rafael 2014). This article focuses on another categorization in these photographs: “mestizos” and “mestizas”. In the Spanish Empire, the term mestizo/mestiza denoted, overwhelmingly, people of so-called “mixed” European and indigenous ancestry, but there existed also some regional adaptations with differing genealogies such as the mestizomestizos de sangley in the Philippines. This categorization was taken over and adapted by the U.S. colonial administration under whose rule also “American Mestizos” came into being as a new categorization (Trajano Molnar 2017). There is ample research about the mestizo as a colonial categorization in the Philippines (cf. below), but little about its visual representation in the early twentieth century. Therefore, this article brings together the research about the colonial categorization mestizo/mestiza and photographic types, which have been largely analyzed separately until now, with the exception of specific aspects studied by Rafael (2014) and Trajano Molnar (2017).

Chronologically, the article focuses on the first years of U.S. colonial rule in the Philippines. This was also a period which saw an important advancement in the technology of photography. The bulky cameras, which required glass plates and chemicals, began to be replaced by the much lighter, portable, inexpensive Kodak Brownie camera with rolled gelatin-film. This made the already highly popular technology usable for non-expert photographers. In addition, it became increasingly used in anthropology, a still relatively young discipline at the time (Mendoza 2010, p. 598; Halpern 2018, pp. 187–88).

Though the article focuses on the depiction of mestizos and mestizas under U.S. rule, it occasionally looks back to Spanish rule in order to understand the development of this colonial categorization and will also briefly look into how German anthropologists had their share in creating racist taxonomies both during Spanish and U.S. rule. The latter seems pertinent both due to the relevance of their influence and because the photographs studied here stem from a German anthropological museum. Last but not least, it will very briefly point to Filipino perceptions of the categorization.

Miscegenation played an important role in theories of racism and, therefore, also the categorization of the mestizo/mestiza. In this article, I will first provide context by defining anthropometric types, then sketch out the meaning of the term mestiza/mestizo in the Philippines, followed by an analysis of the photographic examples that all stem from the collection Küppers-Loosen in the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum (henceforth RJM) in Cologne, Germany. Most of the photographs from the Philippines preserved in the RJM were produced by the Philippine’s secretary of the interior, Dean Worcester, and his team, but a few were acquired by the collector Küppers-Loosen directly from local photo studios. These examples will be used to explain some mechanisms that furthered the dissemination of ideas about racialization. How were the aesthetics of anthropometric types staged, published, distributed, and consumed by a broad audience? How did the organization of forms of visual representation work on the ground? I will show that there is quite some heterogeneity as to the visual representation of mestizos and mestizas.

2. Analyzing Anthropometric Types

Types are photographs of people who were no supposed to represent specific individuals with their names (although of course they were representations of individuals), but they were intended to represent a specific populational group (Justnik 2020, p. 5). A type would, thus, typically depict either a certain profession or a cultural, ethnic, or racialized group; sometimes both collapsed. Gender and age were crosscutting categorizations. As Burke (2001, p. 138) has put it, the authors or photographers of types “generally concentrated on traits which they considered to be typical, reducing individual people to specimens of types to be displayed in albums like butterflies”. They created what Gilman (1995) has called “images of difference”. Anthropometric types were typically elaborative of non-European, indigenous, or Afrodescendant persons (Hight and Sampson 2002, p. 3), but also within Europe certain groups were similarly represented, especially in Eastern Europe (Hoyer and Röger 2023; Justnik 2012).

Types have existed in a broad variety of media, but this article will focus on photographs. Photographic types were both taken in and outside the studio. Essential in the definition of types are captions and the use of the image. A picture taken of a certain individual in a photographic studio can theoretically be both: on the one hand the portrait of an individual whose name is known and whose portrait is destined for the album of family or friends or, on the other hand, a type, sold by the studio to national and international tourists. In fact, as Justnik (2020, p. 7) has shown, sometimes one and the same picture was used both as an individual portrait and as a type.2

The stereotypical representation of certain populational groups has a long tradition in European art, being the early modern costume books, which focused mostly on the dress and profession of peoples in certain regions, the best known example (Mentges 2015). Similarly successful were the casta paintings in eighteenth-century New Spain, which categorized the represented couples with their offspring according to their degree of European-African-Indigenous miscegenation (Katzew 2004; Castañeda García 2020). At about the same time as the first casta paintings, a broad cultural phenomenon called costumbrismo emerged in the Hispanic world. A sub-genre of the costumbrismo were the tipos y costumbres, the types and customs, which played an important role in the forging of nationalism and in debates about modernity, also in the Philippines, which still continued to be subject to Spain until 1898. These types were conceived as typical for a certain nation or ethnic group, often with a focus on profession, in a highly gendered and racialized way. They were produced in an ample number of media: watercolours, lithographs, woodcut prints, ceramics, wax figurines, and, as the nineteenth century progressed, increasingly in photographs (Barros and Buenrostro 1994, pp. 20–21). These types are sometimes denominated as “tipos del país” (types of the country) or as “tipos populares” (popular types). Despite aiming to show something typical of a certain place, sometimes the images were not produced locally, as the example of the production of Peruvian types in Chinese studios in the nineteenth century shows (Majluf 2006, pp. 40–41).

Photography was introduced to the Philippines in 1841 (Go 2014). Photographic types were first disseminated in the form of cartes de visites from the 1850s onwards (Uslenghi 2019, p. 520) and from the 1890s onwards, often as postcards (Onken 2019, pp. 28–29), as well as in scientific publications and magazines, such as National Geographic, where also Worcester, an important figure in the early U.S. administration of the Philippines, published amply (Worcester 1913).

Anthropology, established as an academic discipline in the nineteenth century, also made use of the technology of photography to produce what could be called anthropometric types. Here, the focus was not always on professions, culture, or clothing but often more on the physical traits of the represented peoples. These types had precedents in other media and genres, most notably travel reports. Starting during the eighteenth century and experiencing a heyday during the nineteenth century, European illustrated travellers, most of them men, had set off to explore and measure the world, with an intent to construct a “global-scale meaning through the descriptive apparatuses of natural history” (Pratt [1992] 2008, p. 15), the zoological taxonomy developed by Linnaeus being a key inspiration for human taxonomies (Hund 2010, p. 2193).

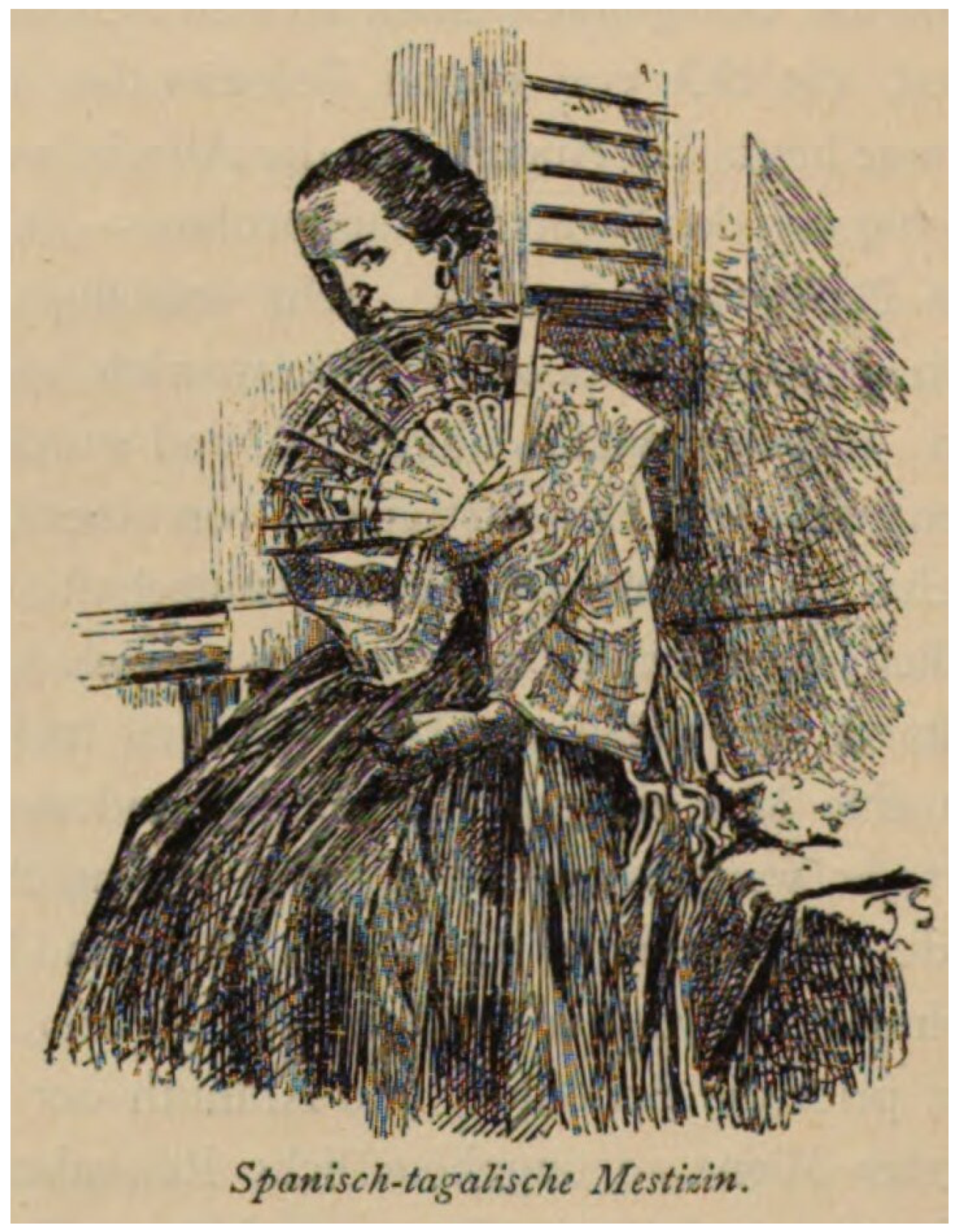

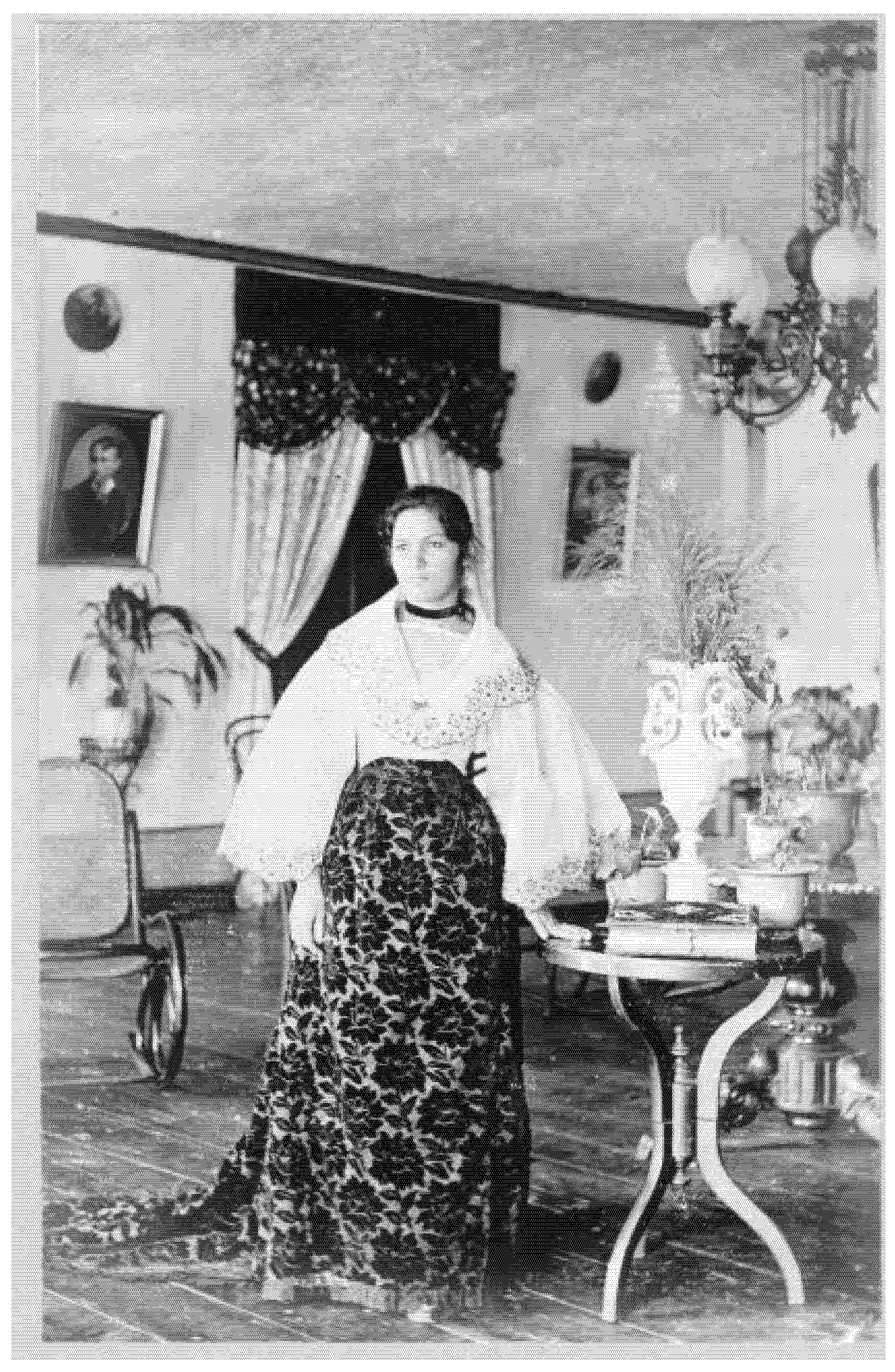

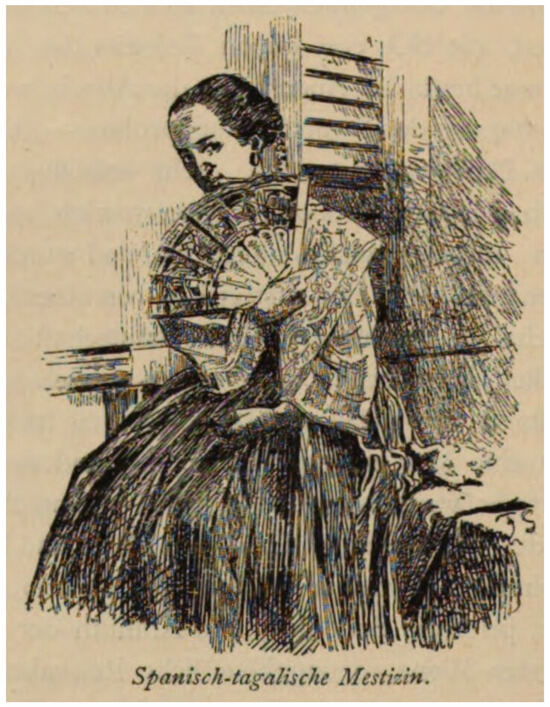

Examples for such images in travel reports from the Philippines are the illustrations accompanying Murillo Velarde’s 1749 history of the Jesuit province in the Philippines (Murillo Velarde 1749) or drawings such as the “Spanish-Tagalog mestiza” in the 1873 travel report by the German ethnographer Fedor Jagor—cf. Figure 1 (Jagor 1873, p. 184; van der Wall 2018). Interestingly, also in the German edition of his book, Jagor uses the Germanized form of the Spanish word “mestiza”, i.e., “Mestizin”, which shows that he was acquainted with the local terminology. Also, the Filipino painter José Honorato Lozano, trained in Chinese painting techniques, elaborated a broad number of tipos filipinos, Filipino types, including several depictions of mestizos and mestizas (Lozano 1847).

Figure 1.

“Spanish-Tagalog Mestiza” depicted on p. 184 of (Jagor 1873). Digitalization retrieved from the Staatsbibliothek Berlin at http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000384B00000218 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

Though most of these illustrations are generally categorized as costumbrista images, the difference between anthropomorphic and costumbrista types is not categorical, but gradual. The aesthetic of anthropometric types is closer to criminal photography, typically portraying the persons both in frontal and profile views, although sometimes in the posterior view; in some instances they included the entire body and in others only head and shoulders. Often, the background is neutral or white, and sometimes some kind of improvised measuring stick is included in the photograph, making reference of the method of anthropometric photography proposed by Jones H. Lamprey in 1869 (Hockley 2010, p. 7), though none of the photographs actually uses the full-fledged Lamprey Grid. Sometimes, the represented individuals are naked or half-naked. These characteristics were intended to ease anthropometric measurements of head and body, integral characteristics of the methodology of biologist racism, which developed craniology, cephalometry, and biometry as own subdisciplines (I. Hannaford 1996, pp. 260–62). Rafael (2014, p. 90) has called them aptly “dead images of living beings”. As Sámano Verdura (2014, p. 41) has adequately pointed out, anthropometric types intended a racialized classification and costumbrista types a social one.3 Or, we could argue, in costumbrista depictions, the peoples were at least partly shown as living beings in their social life—as artificial as the representations and the posing sometimes might have been. Costumbrista types tended to focus more on profession and clothing than on the body and orchestrated the people in a supposed day-to-day setting, either staged in the studio or in apparent snapshots (that were mostly not really spontaneous due to the limitations of technology) in city or countryside. Generally, they have been interpreted as constituting a key visual element in the construction of the newly formed or forming nations (Rojas Rabiela and Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba 2018, p. 24; Majluf 2006, p. 16; Conrad 2006; Justnik 2020, p. 7; Massé 2014, p. 45; Rodríguez Bolufé 2021, p. 140). However, racialization and nationalism as well as enduring colonial structures were not mutually exclusive, quite the contrary.

The overlapping of both aesthetics and the use of anthropomorphic and costumbrista types can be seen in a variety of examples. For instance, anthropologists also employed costumbrista images for their research. As Poole ([1997] 2021, pp. 134–35) has demonstrated for the Andes, several European and U.S.-American scholars bought cartes de visites, displaying Andean indigenous peoples and employed them for their taxonomic studies.4 As we will see below, also Dean Worcester and his crew produced both anthropometric and costumbrista types, sometimes within the same series, depending on what argument they wanted to make with the photographs. Worcester was both interested in cultural elements such as clothing and in the strictly racializing anthropometric measurements. Sometimes, the choice for the aesthetic was related to the position in his racist taxonomy attributed to the individuals being photographed.

As elsewhere in the world, the production and distribution of types obtained a boost in the Philippines with the introduction of photography. There is evidence of types produced in the form of daguerreotypes already in the 1840s (Sierra de la Calle 2022, pp. 252–53). By the 1860s, a significant number of photo studios existed in Manila, most of them located on the Escolta road, and their number continued to grow in the following decades— in Manila and in other cities and on other islands. Many were run by foreigners, especially Europeans, but there were some run by Filipinos (Sierra de la Calle 2022). Some of the studios, such as M.A. Honis, continuously sold photographic types, as can be seen in their advertisements in travel guides (Gonzalez Fernandez 1875, p. 669). One of the most famous Filipino photographers, Félix Laureano, published a book in Barcelona, which contains several types from Ilo Ilo (Laureano 1895).

Already during the U.S. takeover of the Philippines, many U.S. photographers came to the Philippines—the first to document the war and then the newly obtained colonies. Their photographs were distributed, among others, as postcards and in books (E. Hannaford 1900; Anonymous 1900; Landor 1904). Sometimes, the photographs were published together with photographs from Cuba and Puerto Rico, which were also acquired as colonies/protectorates as a result of the war (de Olivares 1899). U.S. anthropologists joined the ranks of European anthropologists that had shown an interest in the Islands since the nineteenth century, many of them Germans. Some of them published photographic types in album-like books (Meyer and Schadenberg 1891; Reed 1904; Scheerer 1905). Robert Bean (1910) even published a manual as to how to determine Filipino types according to the racist anthropometric methodology of the time. The Ortigas Foundation in Manila, which has hundreds of digitized photographic types from the turn of the century, many of them in the form of postcards, also preserves photos of mestizas and some mestizos, mainly from the U.S. colonial period (The Ortigas Foundation Library 2025).

The best-known photographic types from the Philippines of that time are the ones elaborated by the secretary of the interior, Dean Worcester, and his crew. Worcester’s photographs of mestizas and “mixed” individuals demonstrate ideas about race from the point of view of a U.S. colonial administrator (Worcester 1898, 1913, 1914). This article analyzes a selection of Worcester’s photographs, in contrast with an exemplary depiction of a mestiza taken by a local, Filipino-owned photography studio.

To fully comprehend the analysis, the meaning of the term mestizo/mestiza in the Philippines must be explained.

I would like to remark that I employ the categorizations used in the captions of the photographs and in the sources more generally in quotation marks to distance myself from their oftentimes racist and derogatory character.

3. Mestizos and Mestizas in the Philippines

From their annexation by the Spaniards in 1565 until Mexico’s/New Spain’s independence from Spain in 1821, the Philippines was administered via the viceroyalty of New Spain. This meant that their economies and societies were entangled and that they had in principle a common legislation, which was, however, casuistic in nature. One part of this legislation pertained to the colonial categorization of the mestizo. In Spanish America, it came to denote some decades after the initial conquest, the offspring of Spanish and Indigenous parents. In the Philippines, this kind of individuals was denoted “Spanish mestizo” (mestizo de español) to separate them from the “Chinese” or “Sangley mestizos” (mestizos de sangley). The latter were the descendants of indigenous Filipinos and the Chinese, i.e., the sangley population in the Philippines, the latter being far more numerous than the former. In contrast to Indigenous people and (at least theoretically) free Afrodescendants, (Spanish) mestizos were exempted from tribute payments and labour corvée. Mestizos de sangley, however, were tribute payers, but did not have to do corvée labour (Albiez-Wieck 2021). During the course of the nineteenth century, the colonial categorizations continued and, according to Abinales and Amoroso (2005, p. 89), mestizomestizos de sangley continued to pay less taxes than sangleyes but more than rich, urbanized indios until tribute was abolished in 1884.

It has been stated that the mestizomestizos de sangley or Chinese mestizos played an important role in the formation of the evolving middle class of the Philippines however problematic this term might be (Tan 1986, p. 141; Coo 2019, p. 28). Undoubtedly, several mestizomestizos (and mestizas) de sangley pertained to the group of Philippine intellectuals called ilustrados (“illustrated”), which played an important role in the process of the short-lived independence at the end of the nineteenth century (Tolliver 2019, p. 242), with José Rizal, the Philippine hero of Independence being the most famous example. However, as Abinales and Amoroso (2005, p. 99) have argued, “ethnic distinctions between Chinese and Spanish mestizos and indio elites had become anachronistic and were replaced by class-, culture-, and profession-based identities. The three groups gravitated toward a common identity and found it in the evolving meaning of ‘Filipino’”. However, whom the term Filipino referred to and to whom not was still being debated among the ilustrados. Though their opinions differed on certain aspects, they generally shared a certain depreciation towards non-Christianized Indigenous groups such as the Igorrots, the Aetas, and also the Muslim groups in the South. Furthermore, they believed in the theory of the three waves of migration to the Philippines of which the Aetas constituted the first one, and that they were on the verge of extinction. The “true” Filipinos were supposedly the “Malayans” of the supposed third wave of immigrants (after the “Indonesians”), which were Christianized and had occasionally “mixed” with Spaniards and Chinese (Rizal 1913; Paterno 1915, p. 9). These beliefs were heavily influenced by the work of German-speaking anthropologists, being Ferdinand Blumentritt the most famous example since he was a close friend of Rizal and also was in contact with Pedro Paterno (Ariffin 2019, pp. 86–87; Rath 2016, p. 227). He was a Bohemian teacher and arm-chair anthropologist, who never visited the Philippines and based his publications mainly on Spanish reports (Rice 2014, pp. 24–25; Weston 2020, p. 52). Blumentritt shared with other anthropologists of the time the special interest in the Aetas and also in miscegenation (Blumentritt 1892, 1893; Tolliver 2016). German-speaking anthropologists and travellers akin to Jagor were also among those who started to publish photographs of types (both costumbrista and anthropometric), being the already mentioned album by (Meyer 1885; Meyer and Schadenberg 1891), published both in German and Spanish are especially well known. However, van Muijzenberg (2008, pp. 13–14) has called into question whether the Spaniards used them for their ideological projects. It has to be stated that certain Spaniards, among them some Jesuits, already began with anthropometric measurements in the last decades of their rule (Ariffin 2019, p. 138).

The Philippines only gained independence from Spain in 1898 as a result of the Spanish–U.S.-American war, only to almost immediately become a U.S. colony, having suffered from several massacres by the U.S. army in the process (Wagner 2024). When the USA took over colonial rule from the Spaniards—to whom they paid 20 million dollars—they came with a historical and cultural baggage with respect to racism that differed profoundly from the Spanish colonial experience. In the Jim Crow U.S., the one-drop-rule and a system of segregation was institutionalized, and racialized “mixing” even became a felony (Hund and Emmerink 2018). Or, as Buscaglia-Salgado (2018, p. 115) has put it for the U.S., “miscegenation is the criminalization of mestizaje”. However, these regulations were not applied in the Philippines. But they are important to understand the background the U.S. administrators in the Philippines brought with them.

Though both in the USA and in the Spanish Empire, ancestry tied to slavery was seen as despicable, in the U.S., skin colour (and, most of all, blackness) was a more important factor of differentiation. This can be seen, amongst other in the U.S. censuses in the Philippines from 1903, 1918, and 1939, which introduced the section “Color” or “Race” and divided the population into “Brown”, “White, “Black”, and “Yellow” as well as “Mixed” or “Half-Breed”. The Aetas, who had been classified as “indios” under Spanish rule, came to be classified as black (Ariffin 2019, pp. 197–221).

In the Spanish Empire, the different categorizations were more—though by no means exclusively—legal, than racialized (Tolliver 2016, p. 109; Albiez-Wieck 2021). However, like Spaniards and ilustrados as well as Germans, the U.S. Americans also brought with them a profound interest in miscegenation as, among others, Trajano Molnar (2017) and Halpern (2018, p. 190) have convincingly shown. As Winkelmann (2023) has demonstrated, in the early 20th-century Philippines both U.S. and Spanish views on social differentiation converged, being continuously influenced by works of anthropologists coming from different national backgrounds, with the Germans continuing to play an important role under U.S. rule. In some cases, Germans that had established themselves in the Philippines prior to U.S. takeover acted as mediators. An important case in point was Otto Scheerer, a businessman who lived in Baguio and was married to a Filipina, Margarita Asunción de la Cruz (Winkelmann 2023, chap. 2). U.S. colonial rule continued with the differentiation between Christian and non-Christian groups—though now Protestantism began to rival with Catholicism. The Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes was created as being responsible for their administration. “Tribe” began to be used as a term for the different groups inhabiting the Philippine Islands. With regard to mestizos, the U.S. administration abolished the former differentiation between “Spanish-Filipino” and “Chinese-Filipino” as census categorizations—but it maintained differentiating the “Chinese”. This was accompanied by discriminatory measures against them (Abinales and Amoroso 2005, p. 124). thereby following contemporary ideas of racialized inferiority of Chinese, which were present in the USA (Volpp 2000). At the same time, and in line with policies in the U.S. and elsewhere, many U.S. administrators considered racialized “mixing” as something leading to degeneration. However, there were also voices in the U.S., such as that of Frederick Chamberlain, author of the book “the Philippine problem” (Chamberlain 1913, p. 234) who thought that the “mixing” of Filipinos with Europeans and Chinese had positive effects in the past since he considered the “mixed” children to be much better than their Filipino parent. But overall, these voices could not impose themselves.

In the following, I will take a look at how mestizos were represented in photographs, contrasting the case of Dean Worcester and his crew and a local studio.

4. Dean Worcester’s Vision on Mestizas in the Philippines

The best-known U.S. administrator and researcher of the Philippines who fostered a racialized perception of the Filipino population was Dean Worcester. He had visited the Philippines under Spanish rule from 1887 to 1888 as a student in two expeditions and later became a member of the Schurmann and Taft commissions. He was appointed secretary of the interior of the Philippines in 1901 and stayed in office until 1913. As such, he created in 1901 the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes as well as the Bureau of Science. For the former, he personally nominated the director David Barrows (Ariffin 2019, p. 117). In the meantime, he had resigned from his position of teaching zoology at the University of Michigan. From early on, he showed an interest in miscegenation (Winkelmann 2023, p. 125). He and his team produced more than 5000 negatives of the Philippine’s population, mostly on trips that took place between 1900 and 1911. Worcester himself had learned photography as a young man (Capozzola 2014, p. 3). He had already taken photographs during the Steere and Menage expeditions when the Philippines were still under Spanish rule (Ariffin 2019, p. 146) and already in 1898 published a book about the Philippines (Worcester 1898). Interestingly, he often used a camera with glass-plate negatives instead of a portable Kodak Camera, which Rice (2014, p. 9) has interpreted as a sign that “he wanted his photographs to be more than just ‘snap-shots’”. His trips and those of the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes were, in his view, scientific expeditions, which took with them not only photographic equipment but also instruments for anthropometric measurements. They all have very similar aesthetics, independent of the photographer who actually took them. Many, but by no means all of the people he and his team photographed were naked, sometimes with their clothing still lying by their feet on the photos and sometimes they were made to stand before a white cloth or neutral background. Usual positions are front and side views and sometimes from the back. Sometimes, only specific parts of body were photographed. Other photographs did have a clearer focus on cultural elements and clothing and showed the peoples carrying out certain activities. Many photographs were taken outdoors, but some in the studio. It is noteworthy that Worcester’s first book, published in 1898, did contain only photos of costumbrista types (including two mestizas, cf. below) but no anthropometric ones (Worcester 1898). Ultimately his goal was to further and legitimize U.S. rule in the Philippines, which he argued to be necessary since he did not see the Filipinos and Filipinas he photographed fit to rule themselves. His team members, including the photographers, worked with him together on that same goal; resulting in a common aesthetic, which reflected the racialized hierarchical taxonomy developed by Worcester.

His photographs have been studied amongst others by Rice (2011, 2014), Vergara (1995), Fernandez (2023), and Capozzola (2014), but with a focus on his representations of Indigenous groups, especially in Luzón. Worcester took a very active role in distributing a considerable part of these photographs worldwide. He sold and donated them to museums and collectors in the USA and Europe, published books (Worcester 1898, 1914) and articles in the widely read National Geographic (Worcester 1913), and gave highly successful lantern shows in the US (Rice 2014, chap. 4). Both his publications and lantern show a clear preponderance on the photographs of the what he called “Non-Christian Tribes” and especially the indigenous group he called “Negritos”—similarly to the anthropologists and administrators of the time. Today “Negritos” are known and self-identify as Aetas. His interest in the Aetas, like that of German and US anthropologists (Reed 1904; Bean 1910, p. 234; Blumentritt 1893), but also of Filipino ilustrados such as Pedro Paterno (1915, p. 9), was fueled by the assumptions that Aetas had constituted the first immigrants of the Philippines, and that they were of “pure blood” and at the same time on the verge of disappearance (Worcester n.d., p. 88; 1913, p. 1158; 1914, p. 532). This was a common trope attributed to many Indigenous peoples by anthropologist of that time all over the world (Poole 2005, p. 164; Halpern 2018, p. 190).

More than three thousand positives by Worcester are today in the collection of the ethnographic Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum (hereafter RJM) in Cologne, Germany, and these were the ones consulted for this article, with special emphasis on those depicting mestizos and mestizas. In a letter to Küppers-Loosen, the collector who acquired the prints, Worcester stated that he had sold a very similar collection to Mr. Ayer in the US (Worcester 1906, pp. 3–5). Furthermore, a printed list of prices is included in the documentation, a print that would not have been made if there would not have been a considerable number of buyers.5 Rohde-Enslin, who studied part of the RJM collection in the 1990s, tells us that 829 of the 3477 photographs of the collection have been published 1167 times in total (Rohde-Enslin 1999, p. 278). Having in mind the influence of German anthropologists on racialized taxonomies in the Philippines, it seems only consequential that photos from the Philippines made it back to Germany—bought by a German collector, who later became the director of the RJM—thereby somehow closing the circle.

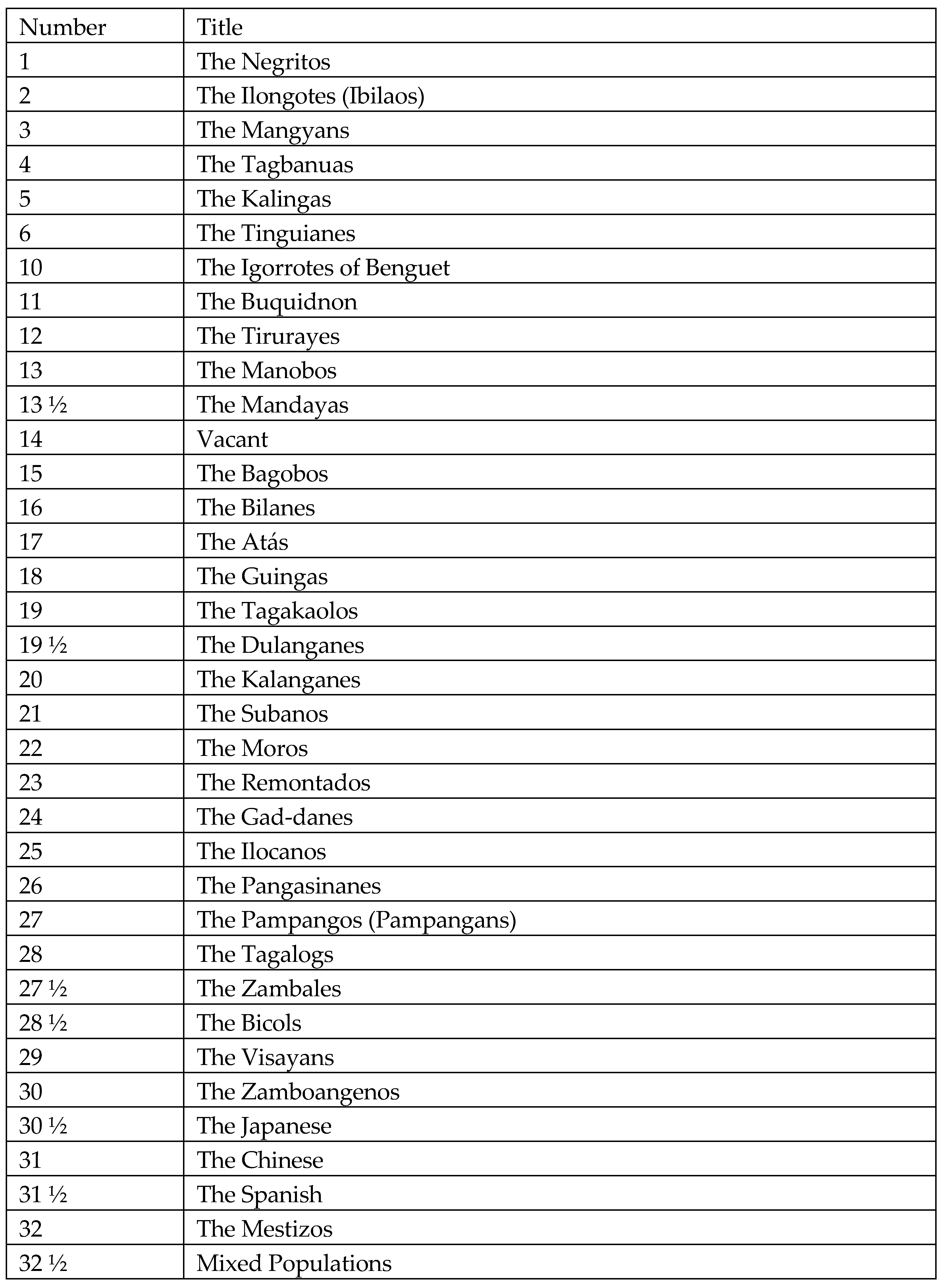

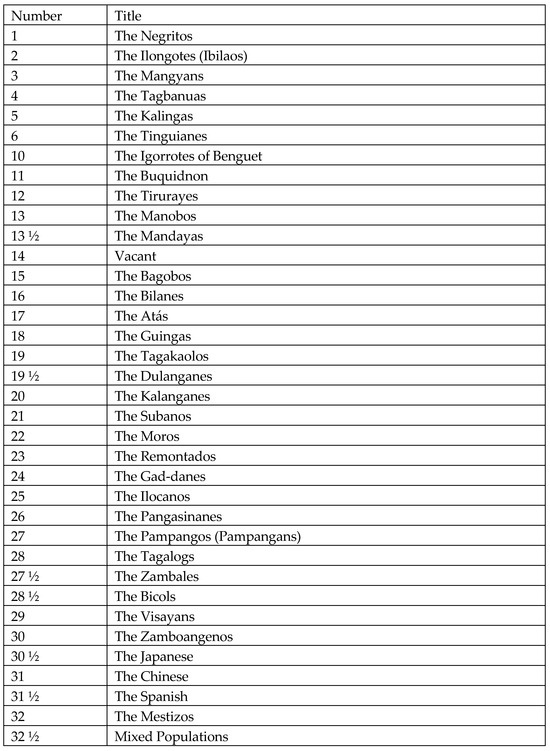

These photographs were an important tool in the elaboration of a detailed racialized and hierarchical taxonomy of the population, which is reflected in the organizational schemes of Worcester’s various versions of the catalogues of these photographs.6 As Rice (2014, pp. 34–35) has shown, these lists were not completely concordant in their numeration, but their general racist logic was consistent. It intersected with religious discrimination—90% of the photographs were taken of what he labelled as Non-Christian groups. The original list consisted of thirty-six hierarchized categories, with a series of numbers not being filled. In a 1902 and 1905 Index and in the Archive of the University of Michigan of Ann Arbor, where most of the negatives of Worcester are preserved, the group he called “Negritos” was always labelled as belonging to the lowest category, no. 1, since he felt them to be the less civilized. Quite surprisingly, mestizos (numbered 31) and “mixed populations” (numbered 32) had the highest numbers and were, therefore, located at top of this hierarchy (Rice 2014, p. 29). In the Index of photographic positives, which Worcester sold to Küppers-Loosen and that are preserved in the RJM, mestizos and “mixed populations” were both numbered 32—cf. Figure 2. They come after the Japanese (number 30) and the Chinese as well as the Spanish who share number 31. “Pure Americans” and “American Mestizos” are nowhere to be found in this list, but individual U.S. citizens are occasionally listed with their names and are photographed—but not as anthropometric types. This in spite of the fact that the descendants of U.S. Americans and Filipinas, the “American Mestizos” were displayed in this period in type-like photographs, as Trajano Molnar (2017, pp. 87–93) has shown.

Figure 2.

List of Series of populational groups as categorized by Worcester as they appear in the Index to Photographic Prints in the RJM, Köln, OAHFPhi, S. 611-1164. Some numbers (7–9) do not appear in the Index or are titled as “Vacant” (14). Subseries are not mentioned in this table.

In the following, I will analyze how mestizos and “mixed” people are represented and described in the Philippine materials contained in the RJM. Most of the photographs whose author is being identified in the catalogue or the Index elaborated by Worcester were taken by Dean Worcester or a member of his crew, C. Martin and J. Diamond. There are, however, a few photographs with the label “Dyonisio Encinas” (sometimes alternatively spelled Dionisio) or “Piang Studios” (on the photographs and/or in the catalogue), seemingly a Filipino photographer and his studio, which were located in Zamboanga, Mindanao. It is unclear from the pertaining documentation if they were sold by Worcester to Küppers-Loosen or if Küppers-Loosen, who visited the Philippines in 1906 (Englehard and Rohde-Enslin 1997, p. 34), did purchase them directly himself.7

In the digital inventory of the RJM, 81 prints refer to “mestizos” or person labelled as being of “mixed blood”, picking up the original captions of the photographs in the Museum collection. Contrary to Jagor, here the German words “Mischblut” and “Mischling”8 are employed, which was used in the German colonies, not the Spanish term mestizo, which was also used in English (Bauche 2022). This could either point to the fact that Küppers-Loosen—or the staff at the Museum were less familiarized with the terminology of the Philippines, or that Jagor had not used the German colonial term because at the time of the publication of his book, the German empire had not yet acquired colonies.9

Mestizo, like many other categorizations and stereotypes, is a term that Worcester adopted from the Spanish colonial terminology (Cf. Rohde-Enslin 1999, p. 283). It is worth taking a closer look the subcategories of “mestizos” and “mixed populations” in the RJM collection. In the digital inventory of the RJM, 26 entries refer to “mestizos” and 56 to “mixed populations”. The former, mestizos, are divided into “Spanish, Chinese, German, American”, i.e., “mixtures” of Filipinos with national groups outside of the Philippines. The latter, “mixed populations” were divided into “Ilocanos and God-Danes of Isabela” and “Tagalogs and Ilocanos, Nueva Ecija”, i.e., different groups original to the Philippines (Worcester n.d., p. 37).

The separation of different types of “mixture” implied a hierarchization between the two. This becomes clear if one reads first the initial description of the Series 32:

The MestizoMestizos

“Mestizo” is a word applied in the Philippine Islands to a person of mixed race. The most intelligent and highly educated and influential men in the Islands are Spanish mestizomestizos. Many of the best business men are Chinese mestizomestizos, and those two classes are numerically and in every other way by far the most important classes which exist.

There may be found a limited number of French and German mestizomestizos, and since the American occupation many children have been born of American fathers (both white and black) and Filipino mothers.(Worcester n.d., p. 641)

Later on, in the same series, he differentiates the mestizos, from what he calls “mixed populations”:

In some provinces there is such a mixture of representatives of the different civilized tribes, that it is impossible to determine to which one of the many tribes any given individual or family probably belongs without actually inquiring, as there is nothing in dress, manner or customs to afford an unfailing index to the tribal relations of such people. This is especially the case in the Provinces of Cagayan, Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya, where Ilocano immigrants are inextricably confused with the old Gad-dan settlers. In the following small series of views no attempt has been made to distinguish between the two tribes.(Worcester n.d., p. 648)

Here, Worcester speaks of “mixtures” only among what he considered to be “civilized tribes”, which meant that they were Christianized. However, in other parts of the Index, he also speaks of persons of “mixed blood” (e.g., Worcester n.d., p. 111) among the “Negritos”/Aetas, the Non-Christian group he labelled as less “civilized” and which occupied the lowest echelon in his racist taxonomy. In the descriptions, he seems to claim that he could tell apart degree of “mixtures”, as in the following description of the picture numbered 1-b 49: “Group of five Negrito men of mixed blood; indeed the man at the left seems to have no Negrito blood at all and the man at the right has very little” (Worcester n.d., p. 111). This contrasts with the quote above where he said that he could not tell apart visual differences among the “civilized” peoples who intermarried with each other. This is in line with the conclusion of Enslin and Englehard who studied mainly the photographs of the “Non-Christian tribes”. They state that there is a certain degree of arbitrariness and manipulation in the captions, which show us that the categorizations were not very convincing (Englehard and Rohde-Enslin 1997, p. 41; Rohde-Enslin 1999, p. 283).

In the following, I will briefly analyze four photographs of people labelled as “mestizos” or of “mixed blood” in the Küppers-Loosen collection. All four images were donated to the RJM by Ms Küppers, as part of her late brother’s collection in May 1911. Only the first three bear the additional remark that they had been bought by Mr. Küppers-Loosen from the Bureau of Science in Manila in 1906. The first three photographs are good examples as to how Worcester and his crew staged their photographs in order to exemplify his racist taxonomy, though only one of them is a clearly anthropometric photograph. I hypothesize that the fourth one is probably not a photograph by Worcester or his crew but one made by a Filipino studio, possibly the already mentioned Piang studio and probably acquired directly by Küppers-Loosen during his stay in Manila. Only the first one is a typical example of an anthropometric type. While the first one can be seen as paradigmatic of hundreds of similar photos in the collection, the second, third and especially the fourth constitute exceptions. Photos like the first one were of the type which was distributed most widely through publications and lantern shows by Dean Worcester (Rice 2014, chap. 4).

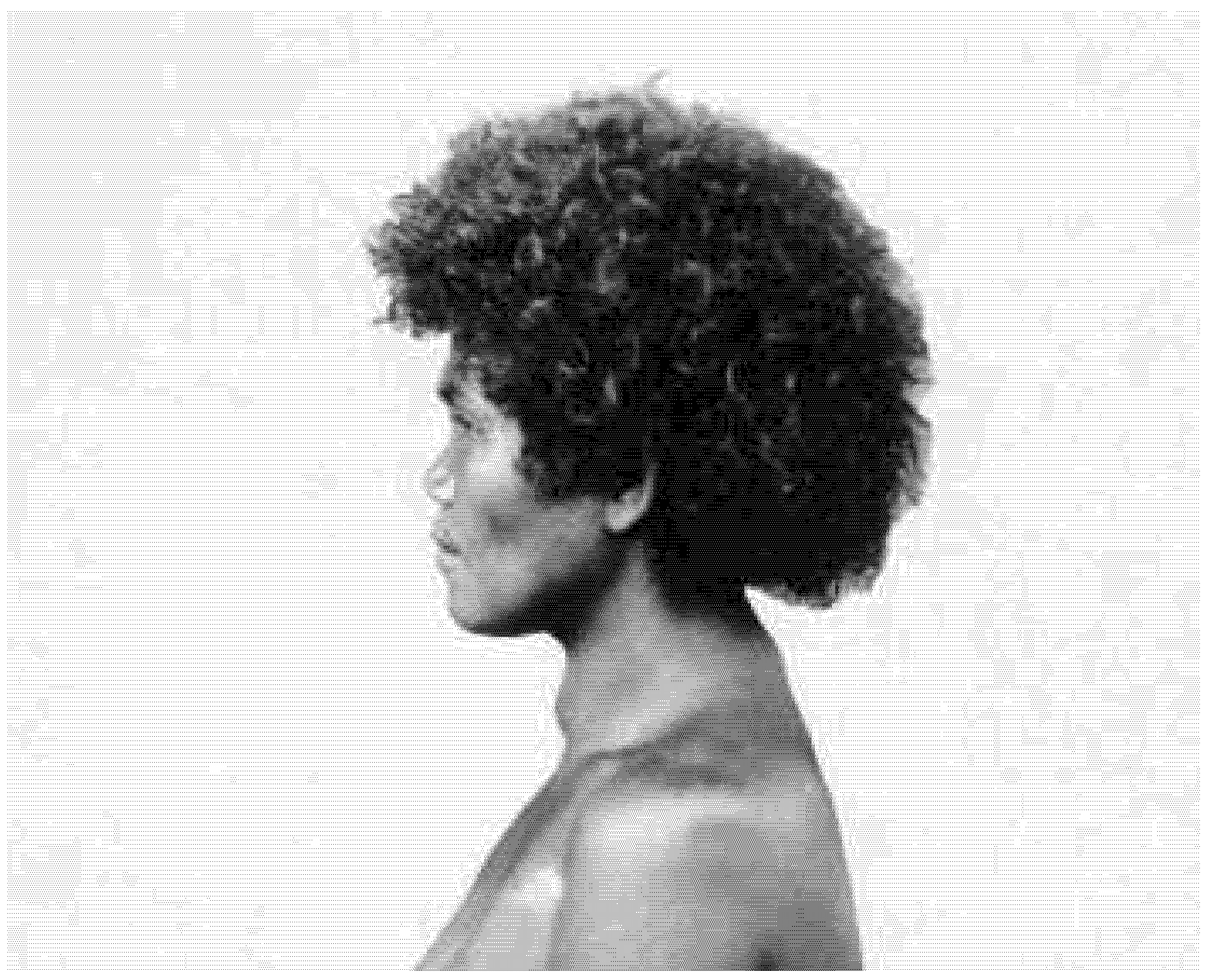

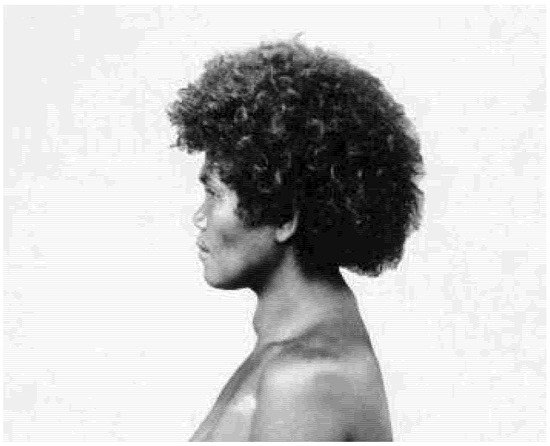

The first image (cf. Figure 3) carries the inventory number 5806 in the RJM, but it also has an original number from the Index elaborated by Worcester/the Bureau of Science, which is 1b68. The number one attributes it to the “Negritos”/Aetas-series, which occupied the lowest echelon in Worcester’s taxonomy. The letter “b” is a geographic indication, referring to the province Zambales on the main Island Luzón. The number 68 results from the numeration of the photographs in this series. The representation of those “Negritos” categorized as being of “mixed blood” does not differ from the depiction of “Negritos” categorized by Worcester and his crew as “pure”. Everything labelled by him as “Negrito woman of mixed blood” (Worcester n.d., p. 114) (“Negrito-Weib. Mischblut” in the German caption) tells us about Worcester’s depreciation for this group—from the derogatory name “Negrito” instead of Aeta to the “half length side view” (Worcester n.d., p. 114), which was used for anthropometric measurements to the relatively short curly hair. None of the mestizos categorized as more civilized in the series 32 is photographed in this position nor are they depicted with bare breasts, an element of eroticization typical in colonial contexts, which has already been pointed out for Worcester’s work (Rohde-Enslin 1999, pp. 238, 287–90; Rice 2011, 2014) and which I deliberately omitted here by cropping the image. Also in the longer texts about the “Negritos” in the Index and in his publications, Worcester makes his contempt for the “Negritos” clear (Worcester n.d., pp. 88–143). This contempt is also evident in Worcester’s description of the Aetas in his 1914 book The Philippines, Past and Present: “They seem to be incapable of any considerable progress and cannot be civilized. Intellectually they stand close to the bottom of the human series” (Worcester 1914, p. 532).

Figure 3.

Detail of “Negrito” woman categorized by Worcester as “mixed blood” (No. 5806 RJM—1b68 Index).

This racist view of the “Negritos”/Aetas—categorized either as “mixed” or “pure” was not only distributed widely by the photographs Worcester employed in his publications and highly successful public talks with lantern shows, but also in publications by (former) members of Worcester’s crew (Rice 2011; 2014, pp. 19–21). In the Index, Worcester or the Bureau of Science created for Küppers-Loosen, Worcester mentions that several photographs were used in the publication “The Negritos of Zambales by Mr. Wm A. Reed, formerly an employee of the Ethnological Survey” (Worcester n.d., p. 109). And in fact, the photograph analyzed here is contained in that said publication with the caption “Negrito woman of Zambales (mixed blood). Photo by Diamond” (Reed 1904). Here, and in the preface, it becomes clear that the photographs from Zambales were not taken by Worcester himself but by the photographer J. Diamond. Reed fully agrees with Worcester’s vision on the “Negritos”. Employing a terminology typical for the racism of the period, Reed concludes the following with regard to the “mixture” of the “Negritos”/Aetas:

After all, Blumentritt’s opinion of several years ago is not far from right. Including all mixed breeds having a preponderance of Negrito blood, it is safe to say that the Negrito population of the Philippines probably will not exceed 25,000. Of these the group largest in numbers and probably purest in type is that in the Zambales mountain range, western Luzon.(Reed 1904)

Blumentritt is one example of several, including Küppers-Loosen, which show how German/German-speaking anthropologists equally contributed to the distribution of a vision of the racialized Filipinos as culturally and corporally inferior (Weston 2020). As Ariffin (Ariffin 2019, p. 90) has pointed out, Worcester himself also quoted the works by Blumentritt and other German-speaking anthropologists since early in his career.

As I will show with the analysis of the next two photographs, mestizos with some part of European ancestry in the Philippines were esteemed as being completely different than those of “Negritos”. The second photograph bears the RJM inventory number 9032 and the original Index number 32c3–cf. Figure 4. Therefore, it is attributed to the “Mestizo” series in the subgroup “German mestizos”. Only three pictures and no introductory text make up this series. All three show the same young woman, first with her father and then twice alone. Winkelmann (2023, pp. 35–39) has identified the young woman as Graciana, daughter of the German Otto Scheerer and the Filipina Margarita Asunción de la Cruz. The family was living in Baguio, and Scheerer assisted Worcester in his trip to the region.

Figure 4.

Portrait of a young woman categorized as “German mestiza” by Worcester (No. 9032 RJM—32c3 Index).

The captions, however, only state that the father is German and that his daughter was born “by a Spanish mestizo wife” (Worcester n.d., p. 647). The terminology regarding the posture implies a similar terminology of anthropometry as the posture is termed as “full length”. However, the aesthetic of the picture is very different from the one of the “Negrito” woman above. Neatly coiffed Graciana poses with a smile and an elaborate dress in a garden, slightly reclining herself on a chair. The white, long embroidered dress has a train and long flowing angel sleeves, the latter, as well as the pañuelo possibly of piña fabric. It has many elements typical of wealthy mestizas of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, also called traje del país, ‘country’s costume’. This is described by Coo as consisting of “baro with wide, flowing angel sleeves, pañuelo, and saya with no tapís”.10 Worcester (1898, p. 33) himself was of the opinion that “[w]hen good materials are used, the dress of the native and mestizo women is very pretty, and it is so comfortable that many of their European sisters adopt it during leisure hours at home”. It is safe to assume that this photograph was taken in circumstances where much less power hierarchies were involved as in the previous one. In fact, the relationship between Worcester and Scheerer was quite good, and Scheerer later on was appointed provincial secretary of the newly formed Benguet Province (van Muijzenberg 2008, p. 221). Moreover, Scheerer himself published a number of anthropological and linguistical studies in German and English, among them a report on the “Nabaloi-Dialect” in Benguet, which contains photographs attributed in the captions to Worcester, e.g., Plate LXXI entitled “Ibaloi Women” (Scheerer 1905).

The photographs of this “German mestiza” alias Graciana circulated much less widely than the photographs by “Negritos”; in fact, until now, I have found no contemporary publication of this photo. Only very recently did Winkelmann (2023, p. 34) publish another photo of the series in which Graciana is portrayed together with her father.

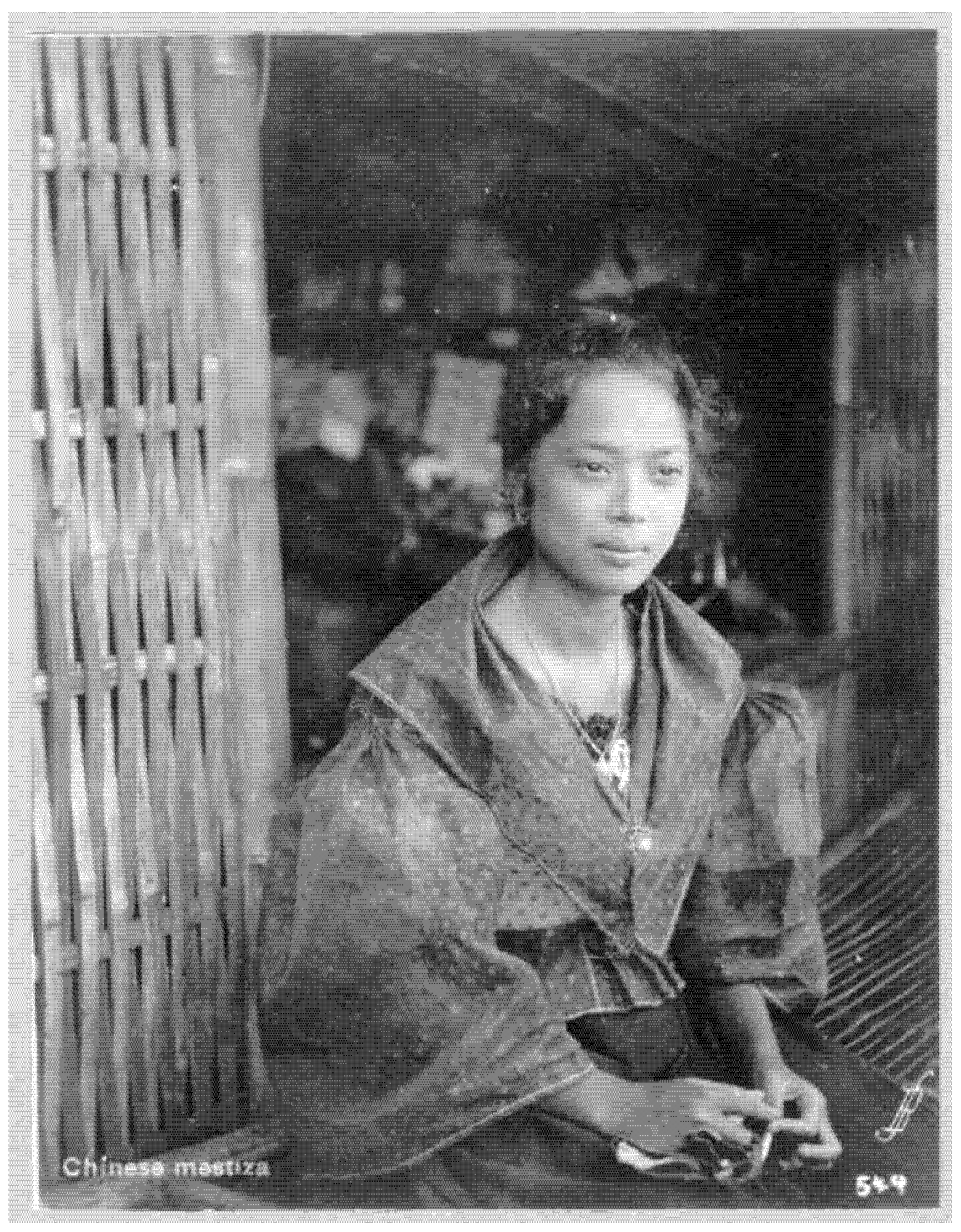

But in several of Worcester’s major publications, photos of Spanish mestizas are shown. In his 1914 book, Philippines Past and Present, a picture of “a typical Spanish mestiza” is included, who wears a similar hairdo and attire in black (Worcester 1914, vol. II, p. 938). In his previous, 1898 book, The Philippine Islands and their people, Spanish mestizas are depicted twice, on pages 34 and 231 (Worcester 1898). The mestiza from p. 261 in this book is also contained among the photographs of the Küppers-Loosen collection and shown below—cf. Figure 5.

Figure 5.

“Spanish mestiza girls at Eastern Negros” (32a2) (No. 9009 RJM—32a2 Index).

The Index from the Küppers-Loosen collection puts this photo together with the next, very similar photograph and gives them the joint caption “32-a 2 and 3. Spanish mestiza girls of Eastern Negros” INDEX part II, p. 0642. The inventory of the RJM translates that as “Mädchen, Mischblut auf Eastern Negros” and dates the photo to 1890. The next photograph, with the inventory number 90010, shows a young woman standing in the same position in the exact same room on the same spot but with a more European-style dress (no angel sleeves) and carrying a closed umbrella. The caption from the Index is similar to the caption in the 1898 book, which states “A Spanish Mestiza—Bais, Negros”.

In Worcester’s book, the second line of the caption of the photograph shown here adds an interesting detail that is not included in the Index: “Taken at the house of Sõr. Montenegro” (Worcester 1898, p. 261). The young woman is, therefore, not named, but more individualized than the Aeta woman mentioned above through her association with the owner of the house, Mr. Montenegros—possibly at the same time indicating also gender norms of the time by privileging the name of the male owner over the name of the “Spanish mestiza”.

For both images of Spanish mestizas, Frank S. Bourns is mentioned as a photographer. Bourns was the chief photographer on the Menage expedition in the late 1880s. In 1897 he published, together with Worcester, the article “Spanish rule in the Philippines” in the Cosmopolitan magazine. Many of the other photographs in Worcester’s 1898 book had also been taken by Bourns (Rice 2014, pp. 2–4; 2018).

The same photo is also included in the digital online collection of the Filipinas Heritage Library where it is labelled as “Spanish mestiza” and dated to 1895 (Spanish Mestiza n.d.).

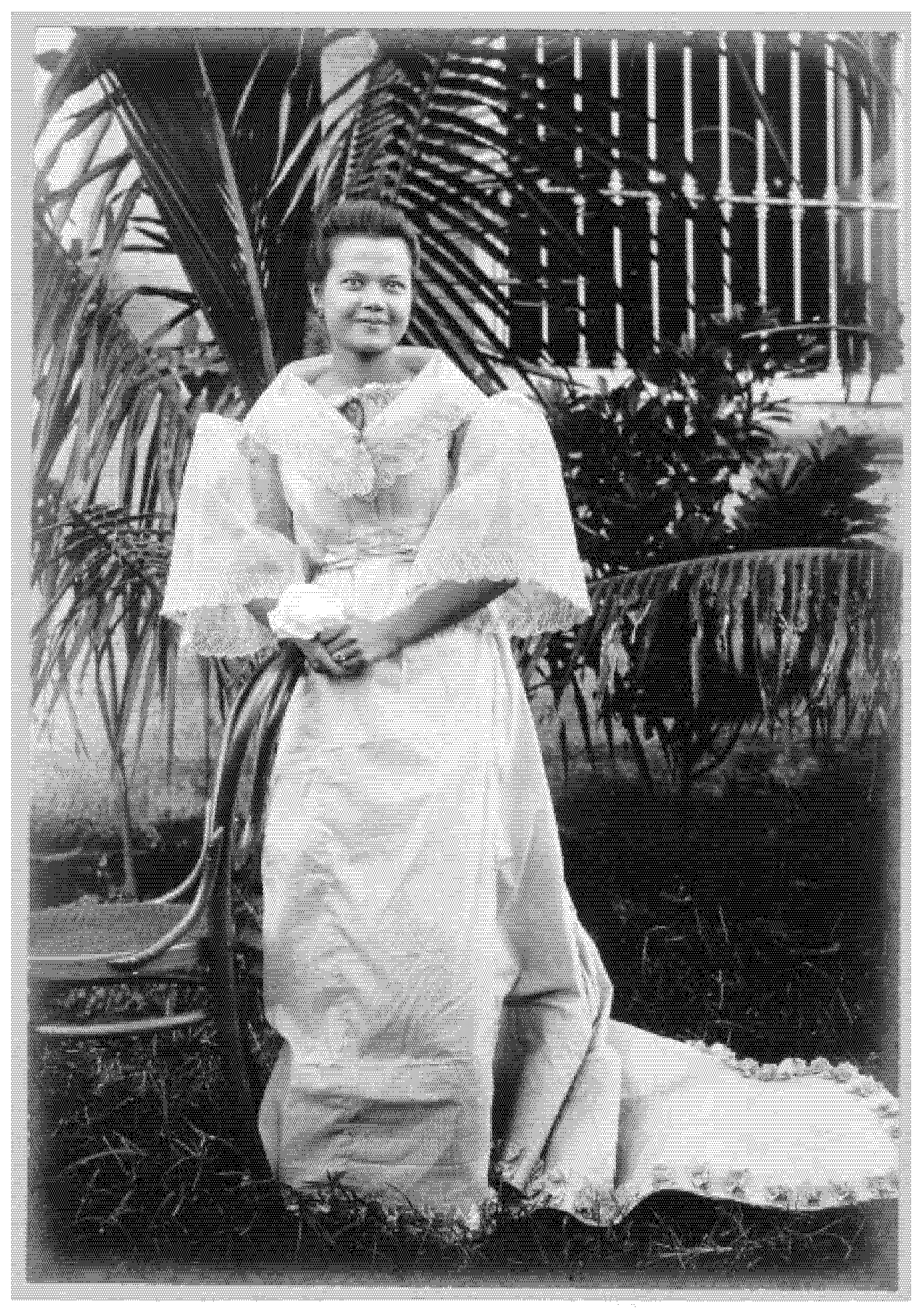

The picture of the Spanish mestiza by Bourns is similar to a photograph by the contemporary Filipino photographer Felix Laureano entitled “la mestiza” published at the end of the Spanish colonial period (Laureano 1895, p. 106)11 and the sketch shown above of a Spanish mestiza by Jagor (1873, p. 184); the latter yet again showing similarities between German and U.S. depictions of the inhabitants of the Philippines. We also see a similarity in the attire of these women. This type of dress was indeed worn by many well-to-do mestizas of varying ancestry and can be seen in the fourth photograph (cf. Figure 6 and also (Coo 2019)), in which the woman wears a similar dress but of a dark tone. However, this photograph, which I will analyze in the next part, was not taken by Worcester or his crew.

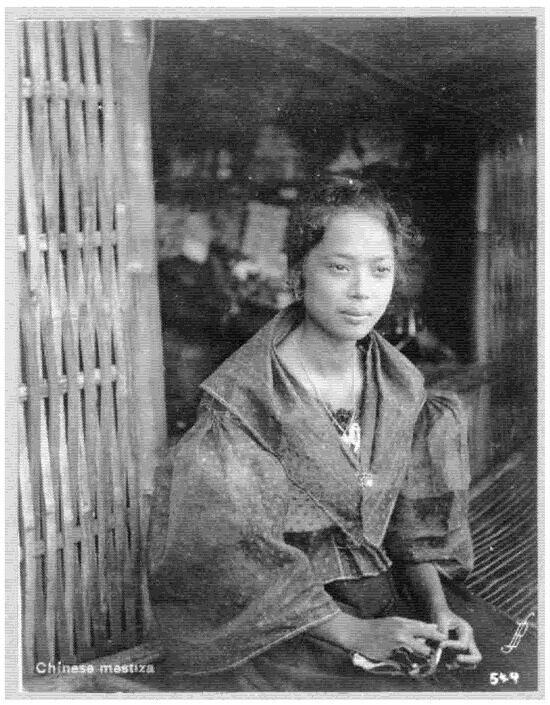

Figure 6.

“Chinese mestiza” (no. 10188 RJM).

5. The Vision of a Mestiza by a Local Photo Studio

This fourth picture from the collections (here Figure 6) is different from the previous three. Here, the posing for the photographer is less apparent, which gives it the appearance of a snapshot, something very difficult to obtain with the technical possibilities of that time (Lederbogen 1990, pp. 26–27). The depicted woman is seated in a slight angle to the camera and does not look at the photographer; contrary to the “German mestiza” and the “Spanish mestiza” she does not smile. She seems to be playing distractedly with an object in her bosom, which could be a purse. Similarly to Graciana, she wears earrings and additionally a necklace, which probably shows a certain wealth. She sits on a bench and in front of a wall which seems to be made of bamboo; on the side of a window which blurrily shows the interior of a room, maybe a shop. Contrary to the previous photographs, this one contains a caption written in white on its front, “Chinese mestiza” on the lower left side, and the number “549” together with a stylized monogram containing the letter “E” and “B”. Several photographs, with inventory numbers close to this one, contain similar inscriptions on the front side. Some of them are clearly studio portraits and some of them contain the inscription “Piang Studios” or “Dionisio Encinas”. The inscriptions indicate that the picture belongs to a series of numbered postcards, produced by a professional photographer. The inscription is in English seems to imply that they were produced for foreigners, probably mainly U.S. soldiers and officials as well as tourists and other travellers who collected these types of postcards for their private collections and sometimes with academic intentions—just like Küppers-Loosen.

In the Philippines, photo studios proliferated in Manila, as outlined above. Much less is known for the studios outside Manila and on other islands such as Mindanao. From Wagner’s (2024) study on the well-known photograph of the Bud Dajo Massacre, we know that there were several foreign photographers present during the military encounters in the region. Henry Gibbs, the photographer that had taken the photo of the massacre was a retired US soldier who opened a photo studio in Jolo in 1906, which remained open until 1918 when he returned to the US. Another US photographer who had established himself in Mindanao was Harry Whitfiled Harnish. Harnish, also a retired soldier, founded a photo studio in Zamboanga, together with his wife Josephine Peas Barnes. They took photos at least between 1898 and 1907. They advertised their work with the slogan “For First-Class Filipino and Moro Views got to Mrs. H.W. Harnish’s Gallery, the ONLY experienced Photographer and The ONLY Gallery in Zamboanga” (University of the Philippines Library 1972).

We know little about Piang Studio(s), but many of its photographs circulated widely in the US colonial era.12 According to Zhuang (2016, p. 317), it was located in Dulawan (near Cotabato), capital of the Buayan Sultanate in Mindanao. Zhuang presents some indicators that the studio might have been owned by Datu Piang (born 1850, died 1933), a powerful Muslim ruler of Maguindanao, datu of Cotabato, himself a mestizo born of a Muslim mother and a Chinese father who had learned photography from the US Americans.

On photographs by Piang Studios, both from the RJM collection and from the Ortigas Foundation, there are inscriptions pointing to Piang studios with the additional inscription Zamboanga13—and not Dulawan. This applies also to the photographs by Dionisio Encinas in the RJM collection which often bear the date 1905. There is also a photo by Encinas of Datu Piang himself (“No. 216 Datto Piang, Chief of the Cottabato Valley”, No. 9982 in the RJM). So maybe Zhuang is mistaken about the location of the studio or there existed two studios or maybe branches with the same name. Wherever the studio or studios were actually located, the photo of the mestiza was taken by a local photographer and commercialized. Therefore, this photograph is a good example for types as a form of commodity.

The Küppers-Loosen collection in the RJM shows that both photographs taken for (racist) “scientific” ends and those taken to be sold to tourists could end up in museums where they showed Europeans, in this case the inhabitants of the German city of Cologne, a specific image of the Philippines. It is unclear if some of Küppers-Loosen photographs were exhibited in the opening exhibition of the RJM which took place in 1906 (Geschichte des RJM n.d.). Worcester wrote to Küppers-Loosen in July 1907: “I am very glad to know that some at least of the prints arrived in time for the opening of the museum at Cologne so that visiting scientists were able to see them” (Worcester 1907, p. 34). However, in the first catalogue of the Museum, dating from 1910, no photographs are mentioned. The racist terminology employed in the catalogue, however, is fully in line with the opinions of Worcester (Foy 1910, pp. 260–62). The sale of these photographs to the German museum provided and provides visitors and researchers of the museum a specific view about the early twentieth-century inhabitants of the Philippines. The colonial and racist view has been, in the last couple of years, increasingly been questioned and criticized. Besides scholarly work, the most recent reinterpretation came with the intervention in the permanent exhibition called “Gegenbilder/Counter Images”. It took place in 2021 and 2022 and showed the engagement of several artists with the colonial photographic archive of the RJM. Therein, Kiri Dalena worked with the photographs by Dean Worcester and his crew, critically highlighting their underlying racist assumptions.

6. Conclusions

In the Philippines, under Spanish and U.S. rule, as well as elsewhere on the globe, anthropometric photographic types were an important tool for racism. In this article, I have shown how professional photographers, local and foreign, researchers, and colonial administrators elaborated and distributed photographic types. The selection, staging, and organization of the photographs made by Worcester and his crew manifest their racist theories, even if not always in a straightforward and uniform way. Especially important, therefore, was the selection of those photographs intended for publication and public circulation. They selected mostly photographs of Indigenous peoples, especially Aetas, both categorized as mixed and not-mixed (Rohde-Enslin 1999; Rice 2014). This obsession with “Negritos”/Aetas was shared by other contemporary anthropologists and travellers, many of them Germans (Blumentritt 1892; Meyer and Schadenberg 1891; Reed 1904; Vanoverbergh 1925; Perez 1904). And accordingly, many previous studies have focused mostly on the stereotyped representation of indigenous groups, which were indeed those most often portrayed and most widely distributed.

As I have shown, mestizos and mestizas were also included both in the theoretical and the visual taxonomic hierarchical system of racialization. The visual representation of these mestizos and mestizas was far from being uniform. The proposed (visual) systems of classifications—or visual taxonomies—were often incoherent and the nuances only understandable for viewers familiar with the theories of racism of that time. Especially if we look at unpublished photographs, we can see that some mestizos and mestizas were represented as being supposedly close to Indigenous peoples, and in this case they were, analogously, shown as, in varying degrees, being backward and uncivilized. Very often, these peoples were photographed in an aesthetic of anthropometric types and sometimes additionally subject to the degrading practice of anthropometric measurements of their bodies. Often, they were depicted naked or half-naked. This was the case of the anthropometric types elaborated by Diamond of a “Negrito” woman categorized by the U.S. administrator and zoologist Dean Worcester as “mixed blood” analyzed here.

Mestizos and mestizas who had a partly European ancestry were depicted in a different way. In this article, I have analyzed the case of a photograph of a German mestiza, Graciana Scheerer. She was shown as superior and cultivated, similarly to a nameless Spanish mestiza. The aesthetic of these and similar photographs was rather that of bourgeois portraits, partly resembling costumbrista types. These types of photographs were much less frequently chosen to be published or shown at popular lantern shows in the US or in anthropological publications in the U.S. and Germany.

In the Philippines, photos of both Chinese and Spanish mestizas were quite often published with this label. The postcard with a Chinese mestiza, probably shot and sold by a local photo studio—the Piang studio—is an example for that, although the aesthetic of that picture is not among the most typical. While the mestizo/mestiza as a colonial categorization began to disappear under U.S. rule, apparently it had not yet lost its fascination.

With the example of these photographs, I argued that both ideas about racism and racist photographs were exchanged between the U.S., Germany, and the Philippines. The apparent aesthetic uniformity in the most widely circulated types is not observable if we have a closer look at a broader part of photographic collections—in this case those of mestizos and mestizas in the Küppers-Loosen-collection of the RJM. This is in line with the findings by Poole (2005, p. 165) about the “the instability of the photograph as ethnological evidence”.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC 2060 „Religion and Politics. Dynamics of Tradition and Innovation“—390726036.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I would like to thank the staff of the photographic archives consulted for this study, namely Lucia Halder, Caroline Bräuer, and Martin Malewski in the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne, Germany, as well as the staff of the Ortigas Foundation Library, the University of the Philippines Diliman Special Collections Section University Library, and the American Historical Collection of Ateneo’s Rizal Library. I also would like to appreciate the support of the Cluster of Excellence Religion and Politics of the University of Münster, which funded my research in Manila. Last but not least I would like to thank Mark Rice for comments on a previous version of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This is why I, following the argumentation by Schaub (2019, pp. 109–13), I will not speak of “scientific” racism. Instead, I will sometimes use the term biologist racism to refer to its specific expressions in the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. |

| 2 | He mentions the example of the wedding portrait of Josef and Mitzi Maier which an ethnographer later re-used as type by adding the caption “Upper Austrian bridal couple” (“Oberösterreichisches Brautpaar”). |

| 3 | She calls them physical types (“tipos físicos”) and popular types (“tipos populares”). |

| 4 | As Cánepa Koch (2018, p. 97) arguments for the German anthropologist Brüning in Peru, scholars furthermore employed and exchanged cartes de visites for personal purposes with their acquaintances. |

| 5 | Price List of Philippine Photographs for Sale by the Bureau of Science, Manila, P.I. (Effective 1 February 1912) (RJM n.d.). |

| 6 | Not all of the 3352 photographs listed in the Index (named “catalogue” in the letters) Worcester sent to Küppers-Loosen are contained in the RJM collection. This is probably due to the fact that the prints were sent in several shipments to Küppers-Loosen. In one letter, it is mentioned that Küppers-Loosen possessed an “old copy of the catalogue” (Worcester 1906, p. 22) and that the photographic prints sent to him with this letter were not listed in the catalogue but that he would receive a new catalogue. It is unclear whether the Index contained in the RJM collection is the “old” or “new” one since it is not dated. And in any case, it does not fully coincide with the photographs contained in the collection. Küppers-Loosen paid for 3716 photographs from the collection of the Bureau of Science and it is unclear how many reached him. According to Rohde-Enslin (1999, p. 281) some photographs, among them of naked women, were lost after inventory. According to the current list, the RJM collection contains today 3787 photographs of the Philippines, 3781 of which are part of the Küppers-Loosen collection. Within that, 3476 photographic prints were acquired from Worcester and his Bureau of Science. These date between 1887 and 1907. The RJM, after having acquired the positives in the early twentieth century, inventoried them, pasted the photographs on cardboard and added a handwritten German subtitle on the front and extracts from the English catalogue on the back, which later on was partly standardized in typewritten form. The German subtitles are normally abbreviated translations of the English catalogue’s description. In the process of inventory, the structure of the collection did no longer fully respect the structure of the Index. Rohde-Enslin digitalized 3777 photographs (these are the ones I worked with for this research) and elaborated a digital inventory in Excel which contains the corresponding 3777 entries of prints and, among other information, their German subtitles and parts of the original English captions (Rohde-Enslin 1999, p. 4). In this digital inventory, no difference is made between the prints acquired from the Bureau of Science and others. Both the identification and the origin of the 304 (delta between 3781 and 3476) photographs which are part of the Küppers-Loosen collection but were not acquired from the Bureau of Science are unclear. Englehard and Rohde-Enslin (1997, p. 34) mention 150 photographs which belonged to Küppers-Loosen and were not acquired from the Bureau of Science. They mention, that some of the photographs might have been taken by Küppers-Loosen himself. |

| 7 | Mark Rice (personal communication, 2022), who thoroughly analyzed the Michigan collections of Worcester’s photos is not entirely sure about the provenience of these photographs, but thinks that possibly Küppers-Loosen acquired them himself. Several of them apparently are postcards which were produced with commercial aims. It would not have been the first time that postcards were acquired by scholars and resignified for (pseudo-)scientific goals. Cf. (Cánepa Koch 2018, pp. 80–81). It is worth mentioning that also Encinas produced photographic “types”. An example is the photo numbered 10033 in the RJM catalogue. On the front of the photograph, the following caption is contained in white color “No. 229.—Yacan (Male). Native of Basilan Island, P.I. Encinas, Photo” (Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum n.d., p. 10033). The online Filipinas Heritage Library contains several dozens of Encinas/Piang studio photographs (Filipinas Heritage Library n.d.), as well as the Image Bank Database of the Ortigas Foundation (The Ortigas Foundation Library 2025). Until now, I have found no other photographs with the label “mestizo” explicitly labelled as elaborated by Encinas/Piang Studios. The Filipinas Heritage Library published online more than 200 pictures with the label “mestizo” or “mestiza” by different authors. The situation is similar for the Ortigas Foundation as well as for the American Historical Collection at the Rizal Library of the Ateneo de Manila University. |

| 8 | In the German captions, the words “Mischblut” and “Mischling” are used indiscriminately, the term “Mestize” is only used in a separate row in the Excel sheet, most probably added by Rohde-Enslin. |

| 9 | It has to be noted, however, that the term “Mischling” was already used before Germany had acquired colonies. |

| 10 | Coo (2019, pp. 180–90) tells us that “toward the end of the nineteenth century, the traje de mestiza, also loosely referred to in the present as the Maria Clara dress, became the standard dress for females of various social classes. In the context of the nationalist struggle and eventual revolution, this began to be referred to as the Filipino dress or traje del país”. In the case of the German mestiza shown here, the dress seems to have been a single piece and not consisted of a separate baro and saya. Also Worcester (1898, p. 33) himself in his 1898 book describes the dress in detail: «consists of a thin camisa or waist, with huge flowing sleeves; a more or less highly embroidered white chemise, showing through the camisa; a large panuelo or kerchief folded about the neck, with ends crossed and pinned on the breast; a gaily colored skirt with long train; and a square of black cloth, the lapis, drawn tightly around the body from waist to knees. Camisa and pañuelo are sometimes made of the expensive and beautiful piña or pineapple silk, and in that case are handsomely embroidered. More often, unfortunately, the kerchief is of cotton and the waist of Manila hemp. Stockings are not worn, as a rule, and the slippers which take the place of shoes have no heels, and no uppers except for a narrow strip of leather over the toes. It is an art to walk in these chinclas without losing them off, but the native and mestiza belles contrive to dance in them, and feel greatly chagrined if they lose their foot-gear in the operation». He also notes that «[many of the mestiza women and girls are very attractive». |

| 11 | Also one of the first photographs from the Philippines, taken by the Dutch photographer Francisco van Camp with the title “Indigena de clasa rica (Mestiza Sangley-Filipina)”, dating from the year 1875, shows a woman in a similar dress (Go 2014). |

| 12 | A considerable number of them forms part of the photographic collection of the Ortigas Foundation (The Ortigas Foundation Library 2025). However, neither there nor in other archives in Manila, did I find much information about the studio. |

| 13 | This is the case, for example, of the photograph titled “No. 279. Moro man and wife, Dansalan, Mind [Mindanao], P. I”. (The Ortigas Foundation Library 2025) The same applies for the photograph No. 9949 of the RJM titled “No. 195, Moro Spear Dance”. |

References

- Abinales, Patricio N., and Donna J. Amoroso. 2005. State and Society in the Philippines. State and Society in East Asia Series; Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Albiez-Wieck, Sarah. 2021. Taxing Calidad: The Case of Spanish America and the Philippines. E-Journal of Portuguese History 19: 110–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. 1900. Souvenir from the Philippine Islands. Manila. [Google Scholar]

- Ariffin, Nur Dayana Mohamed. 2019. American Imperialism, Anthropology and Racial Taxonomy in the Philippines, 1898–1946. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, August 19. Available online: https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/36168/Mohamed%20Ariffin2019.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Barros, Cristina, and Marco Buenrostro. 1994. ¡Las Once y Serenooo! Tipos Mexicanos. Sección de obras de historia. Siglo XIX. México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. [Google Scholar]

- Bauche, Manuela. 2022. Die Figur des “Mischling” in der deutschen Anthropologie (1900–1945). In Jenseits von Mbembe—Geschichte, Erinnerung, Solidarität. Edited by Matthias Böckmann, Matthias Gockel, Reinhart Kößler and Henning Melber. Berlin: Metropol, pp. 300–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, Robert Bennett. 1910. The Racial Anatomy of the Philippine Islanders, Introducing New Methods of Anthropology and Showing Their Application to the Filipinos with a Classification of Human Ears and a Scheme for the Heredity of Anatomical Characters in Man. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Jonathan. 2023. Philippine Colonial Photography of the Cordilleras, 1860–1930. Quezon City: Vibal Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Blumauer, Reinhard. 2014. Die Fotosammlung des Wiener Museums für Volkskunde als Knotenpunkt einer typologisierenden Bilderproduktion zwischen 1895 und 1918. In Gestellt: Fotografie als Werkzeug in der Habsburger-Monarchie; erscheint als Nachschrift zur Ausstellung “Gestellt. Fotografie als Werkzeug in der Habsburgermonarchie”, die vom 29. April bis 30. November 2014 im Österreichischen Museum für Volkskunde in Wien gezeigt wurde. Edited by Herbert Justnik. Kataloge des Österreichischen Museums für Volkskunde Bd. 100. Wien: Österr. Museum für Volkskunde; Löcker, pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blumentritt, Ferdinand. 1892. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Negritos: Aus spanischen Missionsberichten zusammengestellt von Prof. Ferd. Blumentritt. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin 27: 63–68. Available online: https://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?PPN391365657_1892_0027 (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Blumentritt, Ferdinand. 1893. Die Negritos am Oberlaufe des Rio Grande de Cagayan: Nach den Missionsberichten des P. Fray Buenaventura Campa. Von Professor Ferdinand Blumentritt. Mittheilungen der Kais. Königl. Geographischen Gesellschaft in Wien 36: 329–31. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2001. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence. Picturing History Series; London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Buscaglia-Salgado, José F. 2018. Race and the Constitutive Inequality of the Modern/Colonial Condition. In Critical Terms in Caribbean and Latin American Thought: Historical and Institutional Trajectories. Edited by Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel, Ben Sifuentes-Jáuregui and Marisa Belausteguigoitia. First softcover. New Directions in Latino American Cultures. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 109–24. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Luis, and Miguel Semper-Puig. 2023. Introduction: Science and Colonialism. Culture & History Digital Journal 12: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete, Aloysius M. L. 2008. Exploring Photography: A Prelude Towards Inquiries into Visual Anthropology in the Philippines. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 36: 1–14. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29792638 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Capozzola, Christopher. 2014. Photography & Power in the Colonial Philippines—2. Dean Worcester’s Ethnographic Images of Filipinos (1898–1912). Cambridge, MA: MIT Visualizing Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda García, Rafael. 2020. Las Pinturas de Castas: Resignificación para la historia social en Nueva España. In Africanos y Afrodescendientes en la América Hispánica Septentrional: Espacios de Convivencia, Sociabilidad y Conflicto. Edited by Rafael Castañeda García and Juan C. Ruiz Guadalajara. San Luis Potosí: El Colegio de San Luis, pp. 459–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cánepa Koch, Gisela. 2018. Imágenes móviles: Circulación y nuevos usos culturales de la colección fotográfica de Heinrich Brüning. In Fotografía en América Latina: Imágenes e identidades a través del tiempo y el espacio. Edited by Gisela Cánepa Koch and Ingrid Kummels. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, pp. 78–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, Frederick. 1913. The Philippine Problem (1898–1913). Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, Deborah. 2006. “Reproducing Nations: Types and Customs in Asia and Latin America, ca. 1800–1860”. An Interview with Natalia Majluf. Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas 39: 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coo, Stephanie. 2019. Clothing the Colony. Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Olivares, Jose. 1899. Our Islands and Their People as Seen with Camera and Pencil. St. Louis: N.D. Thompson. [Google Scholar]

- Englehard, Jutta Beate, and Stefan Rohde-Enslin. 1997. Unterwegs mit dem Werkzeug des ‘bösen Blicks’: Spurensuche im Historischen Photoarchiv des Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museums. Kölner Museums Bulletin 4: 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ermakoff, George. 2004. O Negro na Fotografía Brasileira do Século XIX. Rio de Janeiro: G. Ermakoff Casa Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Juan. 2023. “From Savages to Soldiers”: Igorot Bodies, Militarized Masculinity, and the Logic of Transformation in Dean C. Worcester’s Philippine Photographs. Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 71: 245–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipinas Heritage Library. n.d. Available online: https://www.filipinaslibrary.org.ph/ (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Foy, Willi. 1910. Führer durch das Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum (Museum für Völkerkunde) der Stadt Cöln: Von Dr. W. Foy, Direktor des Museums, 3rd ed. Cöln: Druck der Kölner Verlagsanstalt A.-G. [Google Scholar]

- Geschichte des RJM. n.d. Kulturen der Welt. Available online: https://rautenstrauch-joest-museum.de/Geschichte (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Gilman, Sander L. 1995. Health and Illness: Images of Difference, 1st ed. Picturing history. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Go, Nicholai David. 2014. Origins of Filipino Photography: An Investigation into the Different Photography Methods Used by the Americans During Their Colonial Occupation of the Philippines. Available online: https://de.scribd.com/document/326919795/Origins-of-Filipino-Photography (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Gonzalez Fernandez, Don Ramon. 1875. Manual del Viajero en Filipinas. Manila: Imprenta de Santo Tomás. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, Rick. 2018. The Back of the Photograph. Radical History Review 2018: 187–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannaford, Ebenezer. 1900. History and Description of the Picturesque Philippines, with Entertaining Accounts of the People and Their Modes of Living, Customs, Industries, Climate and Present Conditions …. Springfield: The Crowell & Kirkpatrick Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hannaford, Ivan. 1996. Race: The History of an Idea in the West. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hight, Eleanor M., and Gary D. Sampson, eds. 2002. Introduction: Photography, “Race” and Post-Colonial Theory. In Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)Ing Race and Place. London: Routledge, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hockley, Allan. 2010. John Thomson’s China—I: Illustrations of China and Its People, Photo Albums (1873–1873). Cambridge, MA: MIT Visualizing Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, Vincent, and Maren Röger, eds. 2023. Völker verkaufen: Politik und Ökonomie der Postkartenproduktion im östlichen Europa um 1900. Visuelle Geschichtskultur 22. Dresden: Sandstein Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hund, Wulf D. 2010. Rassismus. In Enzyklopädie Philosophie: In drei Bänden mit einer CD-ROM. Edited by Hans J. Sandkühler, Dagmar Borchers, Arnim Regenbogen, Volker Schürmann and Pirmin Stekeler-Weithofer. Hamburg: Meiner, pp. 2191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hund, Wulf D., and Malina Emmerink. 2018. Rassismus und Kolonialismus. In Deutschland postkolonial? Die Gegenwart der imperialen Vergangenheit. Edited by Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst and Joachim Zeller. Berlin: Metropol, pp. 269–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jagor, Fedor. 1873. Reisen in den Philippinen: Mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und einer Karte. Berlin: Weidmann. [Google Scholar]

- Jäger, Jens. 2006. Bilder aus Afrika vor 1918: Zur visuellen Konstruktion Afrikas im europäischen Kolonialismus. In Visual History: Ein Studienbuch. Edited by Gerhard Paul. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 134–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jordán, Pilar García. 2016. A visual representation of Chiriguano in Torino missionary exposition, 1898. Hispania Sacra: Revista de Historia Eclesiástica 68: 735–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Justnik, Herbert. 2012. “Volkstypen”—Kategorisierendes Sehen und bestimmende Bilder. In Visualisierte Minderheiten: Probleme und Möglichkeiten der musealen Präsentation von ehtnischen bzw. nationalen Minderheiten. Edited by Petr Lozoviuk. Dresden: Thelem, pp. 109–36. [Google Scholar]

- Justnik, Herbert. 2020. Volkstypen. Typisierende Massenbilder: Identifikation und Differenz im 19. Jahrhundert. Nachrichten. Volkskundemuseum Wien 55: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Katzew, Ilona. 2004. Casta Painting: Imaging of Race in 18th-Century Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Landor, Arnold Henry Savage. 1904. The Gems of the East: Sixteen Thousand Miles of Research Travel Among Wild and Tame Tribes of Enchanting Islands; with Numerous Illustrations, Diagrams, Plans, and Map by the Author. London: Macmillan, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Laureano, Felix. 1895. Recuerdos de Filipinas: Album-libro; util para el estudio y conocimiento de los usos y costumbres de aquellas islas 1. Barcelona: López Robert. [Google Scholar]

- Lederbogen, Jan. 1990. Die Fototechnik zur Zeit Enrique Brünings. In Fotodokumente aus Nordperu von Hans Heinrich Brüning (1848–1928). Edited by Corinna Raddatz. Hamburg: Hamburgisches Museum für Völkerkunde, pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, José Honorato. 1847. Album Vistas de las Filipinas y Trages de sus Abitantes. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España. [Google Scholar]

- Majluf, Natalia. 2006. Pattern-Book of Nations: Images of Types and Costumes in Asia and Latin America, Ca. 1800–1860. In Reproducing Nations: Types and Costumes in Asia and Latin America, Ca. 1800–1860. Edited by Natalia Majluf. New York: Americas Society, pp. 15–56. [Google Scholar]