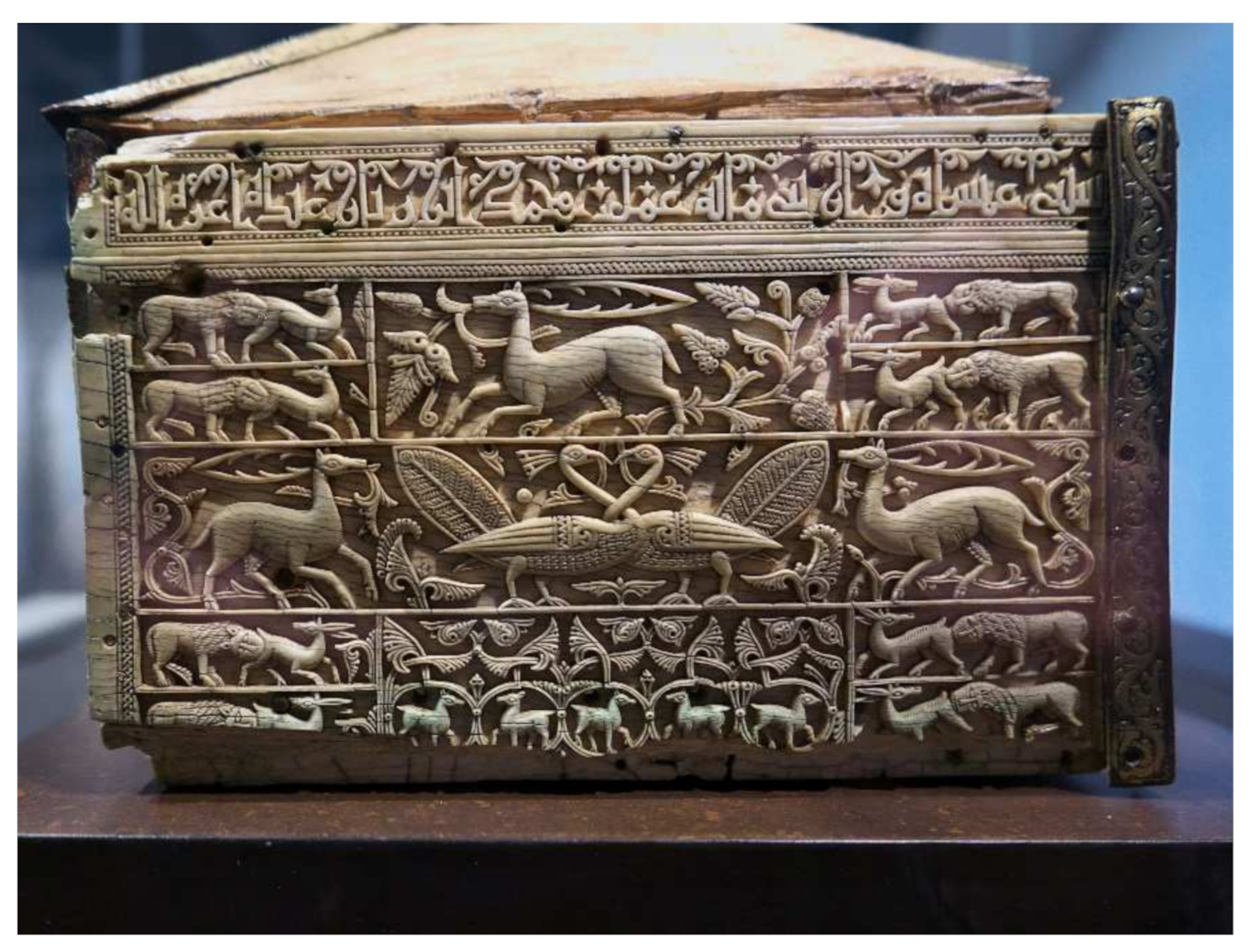

Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and the Iberian Christian Kingdoms: The Role of the Ivory Casket from Santo Domingo de Silos

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Transfers between Andalusi Art and the Spanish Romanesque

2. The Attribution of New Meanings to Andalusi Pieces in the Northern Kingdoms and the Silos Casket Case Study: A Methodological Proposal

3. The Iconographic Impact of the Silos Casket in Spanish Romanesque: The Christian Reception of Andalusi Visual Culture

4. Aesthetics as an Element of Cultural Identity

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This is the case of the ivory caskets from Leyre (c. 1004) and Silos (1026), and the silver casket of Hisham II (c. 1010). |

| 2 | Although each piece followed a different pathway and there were other factors that led to the dispersion of the objects (diplomatic gifts, payments of parias or wars and alliances, as in the case of Hisham’s casket), it can be assumed that the events that followed the fitnah of 1009–1031 involved a more massive looting of this type of courtly possesions. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | That is one of the objectives of the research project in which I am currently involved, entitled “Artistic transfer in Iberia (9th to 12th centuries): the reception of Islamic visual culture in the Christian kingdoms” (2021–2024) PI: Inés Monteira. Project of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation PID2020-118603RA-I00. |

| 5 | “Un arca de marfil labrada a la morisca la qual es llena de las reliquias de las honze mil vírgenes”; "An ivory casket in the Moorish fashion which is filled with the relics of the eleven thousand virgins" ([36], p. 219). |

| 6 | Santo Domingo was considered to be a liberator of Christian captives in Islamic lands from the 12th century on, and the monastery of Silos is decorated with numerous fragments of chains carried there by prisoners returned from al-Andalus. ([37], p. 171). |

| 7 | Although this first Silos workshop was traditionally dated to the end of the 11th century, the most recent works point to the first quarter of the 12th century, being a question that is still much debated ([29], pp. 193–225). |

| 8 | Capital nº 13 of the same gallery is very similar. |

| 9 | In the illustration of Noah´s Ark, Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, MS Vtr. 14-2, fol. 109. Nevertheless Boto indicates that “one cannot rule out the possibility that the iconography was already established in the north, and had circulated among earlier Christian miniaturists for use in texts other than the Beatus” ([38], p. 244). |

| 10 | Some elements such as the veil of these figures, their spurs and stirrups, and the type of bow have allowed to identifie them as Almoravid warriors, see ([32], pp. 467–471). |

| 11 | The Conquering lion over the bull represented military victory in the Islamic art. |

| 12 | This is the purpose of the research project mentioned above. |

| 13 | In the 11th and 12th centuries this workshop was intensely active, on the basis of several other manuscripts from this period still preserved today in the monastery’s library, such as the Silos Missal. |

| 14 | In the regions of Soria, Segovia and Gadalajara we find dozens of churches whose capitals follow the models of Silos until the 13th century. |

| 15 | See the interesting proposal by Milgros Guardia on the possible use of birch bark scrolls that served as templates for Romanesque wall paintings ([39], pp. 168–169). The use of paper in Castile did not appear until the 13th century. |

| 16 | Among the preserved examples we have the notebook of Adémar de Chabanne c. 1020, some loose folios kept in the Benedictine abbey of Einsiedeln, Switzerland, from the first half of the 12th century, a Berlin manuscript of the mid- 12th century, as well as another in London (Victoria and Albert Museum), although these are not model notebooks specifically intended for sculpture and could serve scriptoria as well as sculptors ([40], p. 8). The most complete is the late Livre de portraiture de Villard de Honnecourt, with 33 parchment pages with 250 drawings forming prototypes of sculpture and architecture, dated around 1220 and 1240 and, preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris (MS Fr 19093). |

| 17 | See the work of Joubert [41] on the Central Portal of Bourges Cathedral, following the operational model provided by Wilhem Schlink on his work about the west façade of Amiens. |

| 18 | It is a very studied question, see a state of the arts in [33]. |

| 19 | In the collection of drawings by Adhémar de Chabannes (considered by some scholars as an attempt to create a model book) we find a Kufic script. ([42] pp 163–255). At the same time varoius Romanesque buildings in France and Spain feature Arabic inscriptions on their reliefs, that were copied by Christian artists. |

| 20 | On the aesthetic appropriation of Islamic art in the Italian Romanesque see the recent contribution of K. Mathews [43]. |

References

- Werckmeister, O.K. The Islamic Rider in the Beatus of Girona. Gesta 1997, 36, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierlin, H. Le Livre de Feu. L´Apocalypse et l´art mozarabe; Sigma: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. Los Beatos and the Reconquista. In Patrimonio Artístico de Galicia y Otros Estudios. Homenaje al Prof. Dr. Serafín Moralejo Álvarez; Dir. y Coord. Á. Franco Mata.; Xunta de Galicia: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2004; Volume 3, pp. 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, P. Im spannungsfeld von endzeitängsten, Konflikten mit dem Islam und liturgischer praxis: Die erneuerung der Beatus-illustration. In Vervuert–Iberoamericana: Cruce de Culturas, Arquitectura y su Decoración en la Península Ibérica del Siglo VI a X/XI; Vervuert – Iberoamericana: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zozaya, J. Interacción islamo-cristiana en el siglo X: El retrato del fº 134rv del Beato de Gerona. In Mundos Medievales: Espacios, Sociedades y Poder: Homenaje al Profesor José Ángel García de Cortázar y Ruiz de Aguirre; Editorial de la Universidad de Cantabria: Cantabria, Spain, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 927–938. [Google Scholar]

- Shalem, A. Islam Christianized. Islamic Portable Objects in the Medieval Church Treasures of the Latin West; Peter Lang: Frankfurt, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser-Owen, M. Islamic Objects in Christian Contexts: Relic Translation and Modes of Transfer in Medieval Iberia. Art Transl. 2015, 7, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, É. Art Musulman et Art Chrétien dans la Péninsule Ibérique. Privat: Paris-Toulouse, France, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Mâle, É. Les influences arabes dans l’art roman. Revue des Deux Mondes 1923, 2, 311–343. [Google Scholar]

- Fikry, A. L’Art roman du Puy et les influences islamiques . (PhD Thesis presented in Paris, 1934), E. Leroux, Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, K. French Romanesque and Islam: Andalusian Elements in French Architectural Decoration c.1030–1180; BAR International Series: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Barral i Altet, X. Sur les supposées influences islamiques dans l’art roman: L’exemple de la cathédrale Notre-Dame du Puy-en-Velay. Cahiers de Saint-Michel de Cuxa 2004, 35, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, J.D. Islam, Christianity, and the Problem of Religious Art. In The Art of Medieval Spain. AD 500–1200; The Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, E.R. Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century. Art Hist. 2001, 24, 17–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, J.D. Algunas reflexiones acerca de las pinturas bajas de San Baudelio de Berlanga. In Pintado en la Pared: El Muro Como Soporte Visual en la Edad Media; Manzarbeitia Valle, S., Azcárate Luxán, M., González Hernandez, I., Eds.; Ediciones Complutense: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Santa-Cruz, N. Talleres estatales de marfil y dirección honorífica en al-Ándalus en época del Califato. El caso de Durri al-Sagir. An. Hist. Arte 2012, 22, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, J.A. Muslim Ivories in Christian Hands: The Leire Casket in context. Art Hist. 1995, 18, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Vilar, F. Circular visions of fertility and punishment: Caliphal ivory caskets from al-Andalus. Muqarnas 1997, 14, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalem, A. From Royal Caskets to Relic Containers: Two Ivory Caskets from Burgos and Madrid. Muqarnas 1995, 12, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.M. Plaquitas y bote de marfil del taller de Cuenca. Miscelánea Estud. Árabes Hebraicos. Sección Árabe-Islam 1987, 36, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Galán y Galindo, Á. Los marfiles musulmanes del Museo Arqueológico Nacional. Boletín Mus. Arqueol. Nac. 2005, 21, 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, M.M. Les Routes de la Foi. Reliques et Reliquaires de Jerusalem á Compostelle; Office du Livre/Bibl. des Arts: Fribourg/Paris, France, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjosé Llongueras, L. Obras Emblemáticas del Taller de Orfebrería Medieval de Silos: «El Maestro de las Aves» y su Círculo; Studia Silensia Series Maior IV; Abadía de Silos: Burgos, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Ansón, M.L. Los esmaltes románicos de Silos. In Cuadernos de Arte Español Historia 16, n° 10; Historia Viva: Madrid, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- García Avilés, A. Arqueta de Silos. In Sancho el Mayor y sus Herederos: [Exposición]: El Linaje que Europeizó los Reinos Hispanos; Bango Torviso, I., Ed.; Fundación para la Conservación del Patrimonio Histórico de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 2006; pp. 514–521. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Capilla, S. De mezquita a iglesia: El proceso de cristianización de los lugares de culto de Al-Andalus. In Transformació, Destrucció i Restauració dels Espais Medieval, 2nd ed.; Pilar, G., Màrius, V., Patrimoni: Barcelona, Italy, 2016; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandis, J. Marfiles Árabes de Occidente; Imprenta Estanislao Maestre: Madrid, Spain, 1931; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez De Urbel, J. El Claustro de Silos; Institución Fernán González: Burgos, Spain, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Senra Gabriel y Galán, J.L. El monasterio de Santo Domingo de Silos y la secuencia temporal de una singular arquitectura ornamentada. In Siete Maravillas del Románico Español; Pedro, L.H., Ed.; Fundación Santa María la Real: Aguilar de Campoo, Spain, 2009; pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R. Sculptors in Medieval Spain following the 1085 Fall of Toledo. In Romanesque and the Mediterranean: Points of Contact across the Latin, Greek and Islamic Worlds c.1000 to c.1250; Bacile, R., Mc Neil, J., Eds.; Maney Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2015; pp. 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Hartner, W.; Ettinghausen, R. The Conquering Lion, the Life Cycle of a Symbol. Oriens 1964, 17, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteira, I. Of Archers and Lions: The Capital of the Islamic Rider in the Cloister of Girona Cathedral. Medieval Encount. 2019, 25, 457–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano López, E. Maestros castellanos del entorno del segundo taller silense: Repertorios figurativos y soluciones estilísticas. In Neue Forschungen zur Bauskulptur in Frankreich und Spanien im Spannungsfeldt des Portail Royal in Chartres und des Portico de la Gloria in Santiago de Compostela. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin-Kunstgeschichtliches Seminar; Vervuert Verlag: Berlin/Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2010; pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Monteira, I. El Enemigo Imaginado. La Escultura Románica Hispana y la Lucha Contra el Islam; Méridiennes-CNRS: Toulouse, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Monteira, I. La influencia islámica en la escultura románica de Soria: Una nueva vía para el estudio de la iconografía en el románico. Cuad. Arte Iconogr. 2005, 14, 8–244. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Santa-Cruz, N. La Eboraria Andalusí. Del Califato Omeya a la Granada Nazarí; BAR Series: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lappin, A. The Medieval Cult of Saint Dominic of Silos; Maney Publishing MHRA: Leeds, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boto Varela, G. The migration of Mediterranean images: Strange creatures in Spanish buildings and scriptoria between the 9th and 11th centuries. In Romanesque and the Mediterranean: Points of Contact across the Latin, Greek and Islamic Worlds c. 1000 to c. 1250; Bacile, R.M., Mc Neill, J., Eds.; British Archaeological Association: Leeds, UK, 2015; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Guardia Pons, M. Difusión de modelos y repertorios en la pintura mural hispánica: Los Pirineos y las tierras castellanas. In Modelo, Copia y Evocación en el Románico Hispano; Huerta, H., Pedro, L., Eds.; Santa María la Real Fundación: Aguilar de Campoo, Spain, 2016; pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Stratford, N. Le problème des cahiers de modèles à l´époque Romane. Cah. St.-Michel Cuxa 2006, 37, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Joubert, F. The Function of Drawings in the Planning of Gothic Sculpture: Evidence from the Archivolts of the Central Portal of Bourges Cathedral. In Arts of the Medieval Cathedrals. Studies on Architecture, Stained Glass and Sculpture in Honor of Anne Prache; Katherine, N., Dany, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- Gaborit-Chopin, D. Les Dessins d’Adémar de Chabannes. Bull. Archéologique 1967, 3, 163–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, K.R. Conflict, Commerce, and Aesthetic of Appropriation in the Italian Maritime Cities, 1000–1150; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monteira, I. Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and the Iberian Christian Kingdoms: The Role of the Ivory Casket from Santo Domingo de Silos. Histories 2022, 2, 33-45. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2010003

Monteira I. Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and the Iberian Christian Kingdoms: The Role of the Ivory Casket from Santo Domingo de Silos. Histories. 2022; 2(1):33-45. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonteira, Inés. 2022. "Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and the Iberian Christian Kingdoms: The Role of the Ivory Casket from Santo Domingo de Silos" Histories 2, no. 1: 33-45. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2010003

APA StyleMonteira, I. (2022). Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and the Iberian Christian Kingdoms: The Role of the Ivory Casket from Santo Domingo de Silos. Histories, 2(1), 33-45. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2010003