‘Clan’ and ‘Family’: Transformations of Sociality among the Wampar, Papua New Guinea

Abstract

1. Introduction

‘Marital relations among the Laewomba [old ethnonym for ‘Wampar’, BB] are the saddest imaginable. The Laewomba does not know love or affection in the Christian sense. The woman, because she has to be bought, is only a commodity to him, the Laewomba does not know a cordial affection in the Christian sense. [] Husband and wife never eat together […] When husband and wife go to the field, the wife always walks a few steps behind him, so that strangers have the impression, that they are not at all related.’

2. Social Science Research on the Rise of the Family

2.1. Emerging Middle Classes

2.2. Adoption, Fosterage and the Circulation of Children

“Adoption is widespread in Enkop [her fieldsite, a Maasai village] despite pressures of family nuclearization arising from land tenure transformations, expansion of education and Christianity, and various developmental initiatives aimed at modernizing family life. Children continue to circulate within and across households and the Maasai uphold proudly ideological notions that children belong to no single person or place. However, and unlike many other studies on child circulation in sub-Saharan Africa, pervasive sedentarizing discourses and pressures seem to have pushed parents in Enkop towards a more unitary concept of parenthood and sedentary concept of home.”[26] (p. 238)

2.3. Romantic Love and Companionate Marriage

2.4. Sociology of the Family

3. Circulating Concepts of ‘Clan’ and ‘Family’

4. Inclusion and Exclusion in ‘New’ Social Entities: ‘Patrilineal Clans’ (sagaseg)

5. The Rise of the Nuclear Family among Wampar

5.1. Christianisation

5.2. Marriage, Gender Relations and Domesticity

5.3. Parenting and Education

6. Conclusions: Transformations of Sociality

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | ‘Die ehelichen Verhältnisse sind bei den Laewomba die denkbar traurigsten. Eine eheliche Liebe oder Zuneigung im christlichen Sinn kannte der Laewomba nicht. Die Frau, weil sie gekauft werden muss, ist ihm nur Handelsware, eine herzliche Zuneigung im christlichen Sinne kannte der Laewomba nicht. […] Mann und Frau nehmen niemals die Mahlzeiten zusammen ein. […] Gehen Mann und Frau ins Feld, so geht die Frau immer einige Schritte hinter dem Manne her, sodass der Fremde den Eindruck haben würde, dass diese beiden gar nicht zusammengehören.’ |

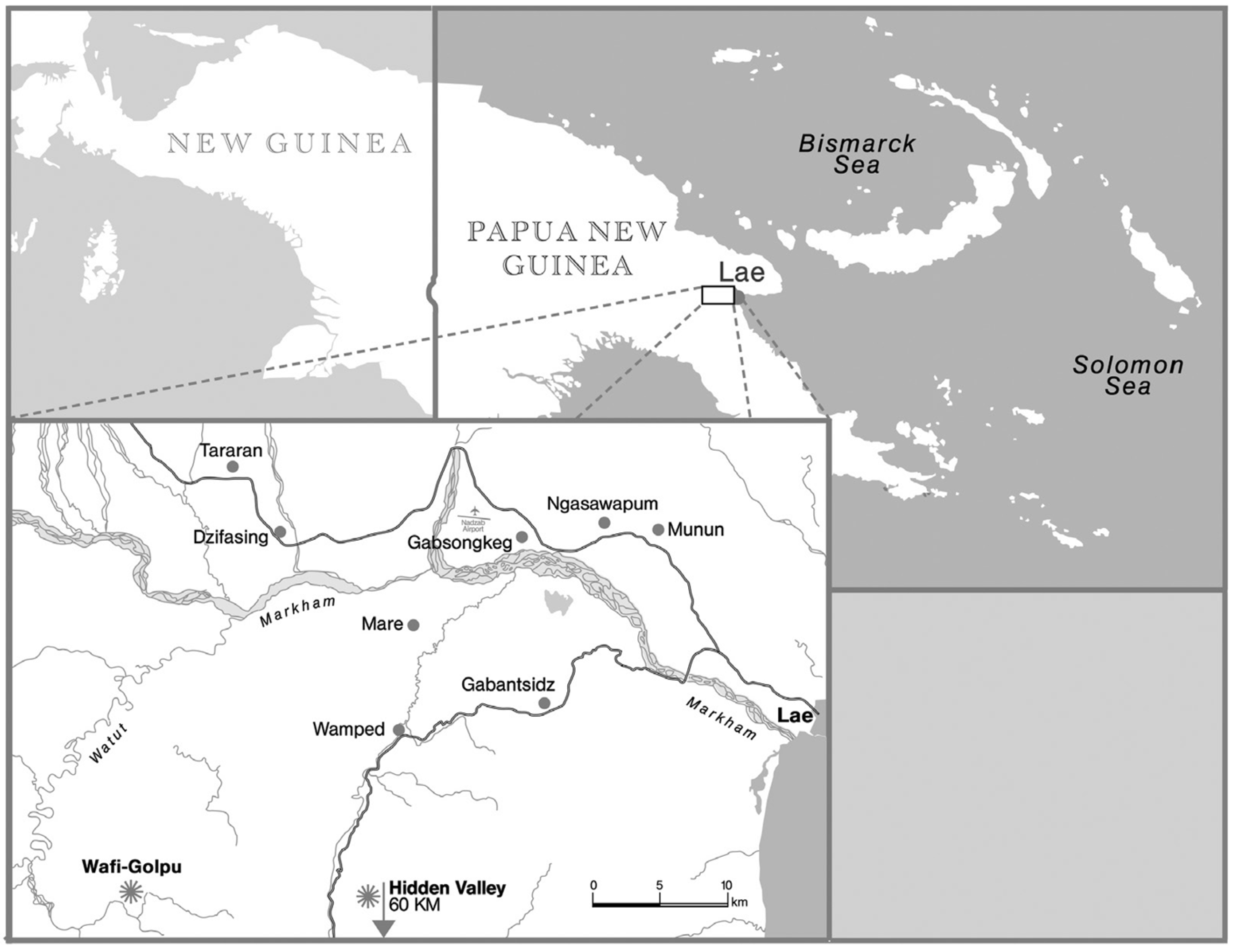

| 3 | The considerations presented here are part of a comparative longitudinal ethnography of international capital and local inequality among the Wampar in the Markham Valley. Our research aims to identify the micro-level interactions that constitute local, district and regional networks of sociality in three Wampar villages. Doris Bacalzo, Willem Church, Tobias Schwoerer and the author has been working as a team in this project, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF). The arguments are based on fieldwork the author has conducted since 1997 (1999/2000, 2002, 2003/2004, 2009, 2013, 2016, 2017). These were funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF), and the University of Lucerne Research Committee (FoKo). The article is also based on published [82,83] and unpublished manuscripts written by Hans Fischer. |

| 4 | In fact, the specifics of New Guinea societies led anthropologists to re-evaluate the models of descent as they had been applied in Africa too. |

| 5 | Strathern [51] characterised ‘dividuality’ as follows, ‘Melanesian persons are as dividually as they are individually conceived. They contain a generalized sociality within. Indeed, persons are frequently constructed as the plural and composite site of the relationships that produced them. The singular person can be imagined as a social microcosm.’ For a critique of these binary conceptions of Western and non-Western personhood and/or self, see Smith [84]. |

| 6 | A critical appraisal of New Kinship Studies would be inappropriate here, and would exceed the space available. Such an appraisal, grounded in empirical research, is the subject of a forthcoming SNF-financed project entitled De-Kinning and Re-Kinning? Estrangement, Divorce, Adoption and the Transformation of Kin Networks. Our project investigates parent–child and affinal relations, and their ruptures, as forces fundamental to kinship networks. |

| 7 | Fischer [62] reports that until the 1970s, all Wampar conceptualized themselves as members of one of the roughly thirty named social units called sagaseg. Wampar today speak of sagaseg as patrilineal groups, but the incorporation of non-patrilineal kin remains common. Moreover, the fusion of non-related sagaseg and the fission of large sagaseg is historically verifiable. |

| 8 | In 2016, for the first time, while conducting census interviews, I met young Wampar who did not know to which sagaseg they belonged. This could be specific for the Gabsongkeg village and might have changed again with the importance of land claims and conflicts. |

| 9 | A women’s dress introduced by the missions to cover naked breasts. It is also cut very wide to hide the shape of the body, somewhat in the manner of maternity clothing. |

| 10 | It ranges from group, family, household, lineage, to clan, descendants and ‘tribe’ or people. |

| 11 | |

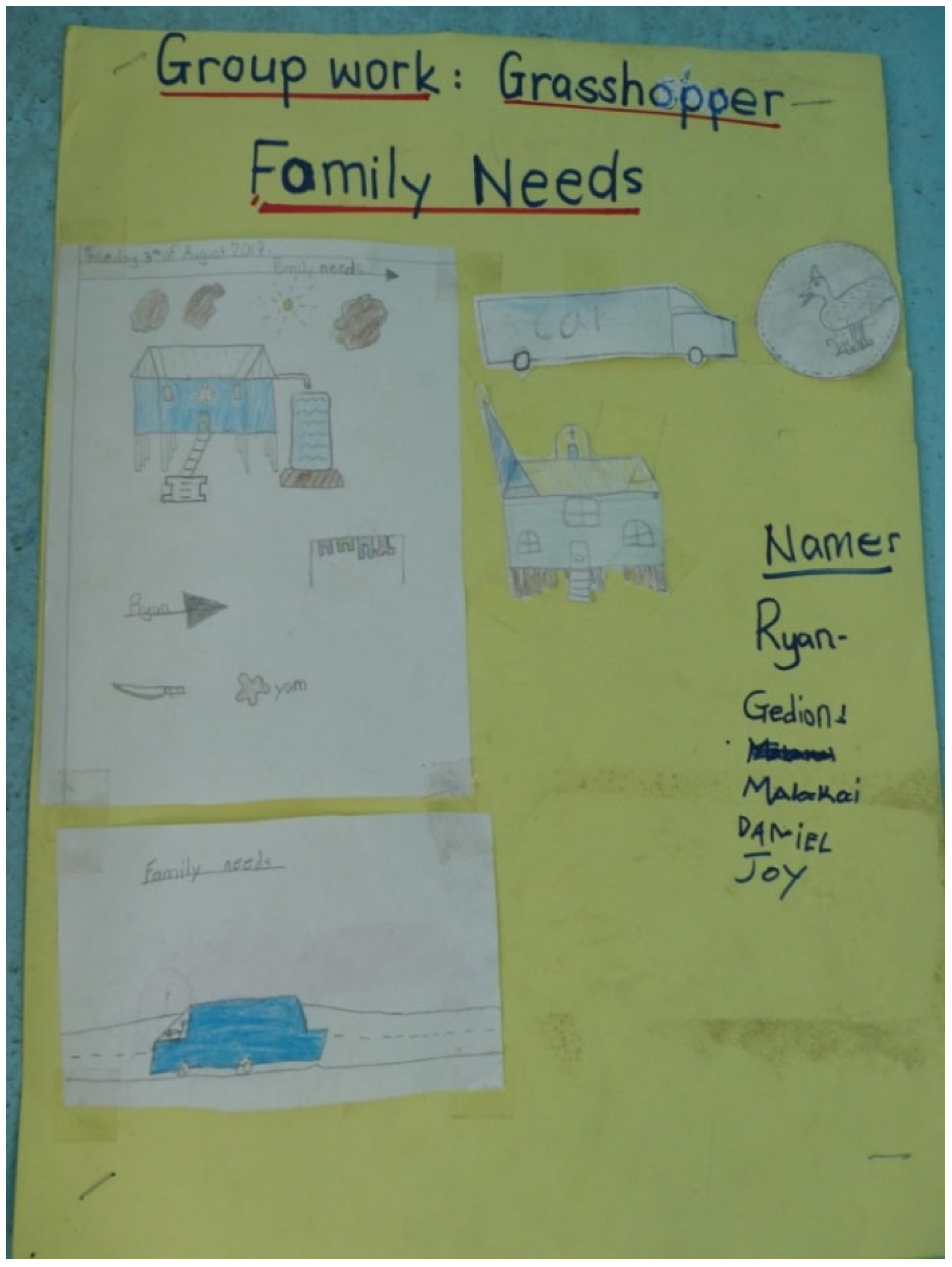

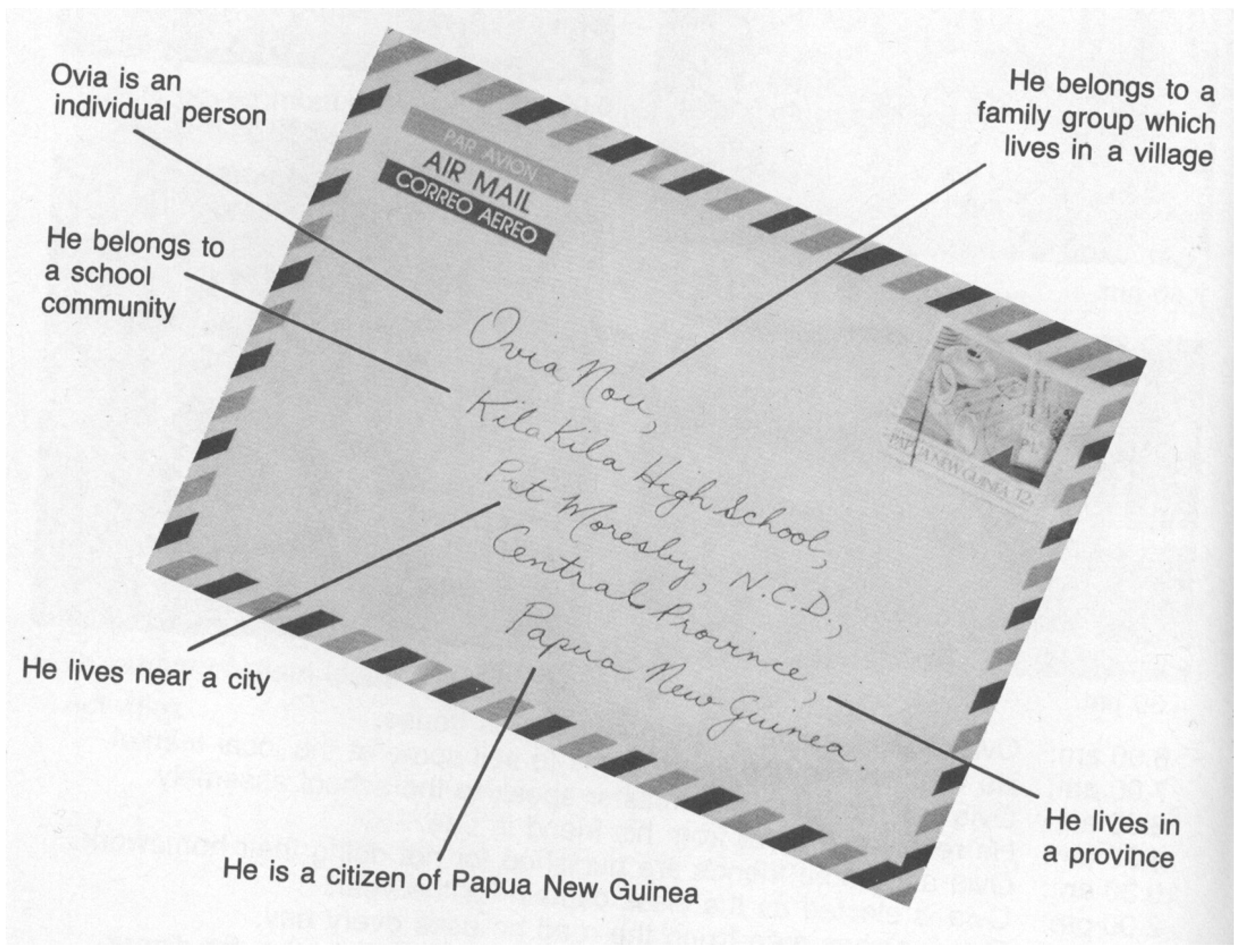

| 12 | First name and family names are listed for each class, the production of lists is one of the colonial techniques which has been taken over and is used for all kinds of occasions with great diligence. In addition, this occurs in more traditional areas, as for example the collection of contributions to bride prices (see Anthony Pickles on listing bridewealth contributions [85]). |

| 13 | In the case of girls—as in former times—the namesakes will receive according to their contribution a share or even the full bridewealth paid sometime after marriage of her or his namesake. |

| 14 | The Bank of the South Pacific, for example, ran a 2015 promotion in which a young man who had won 20000 kina and was quoted that his win had changed his life because he now had a basis for hoping his wish to build a ‘family home’ might come true. |

References

- Anderson, T. Land and Livelihoods in Papua New Guinea; Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne: Australian, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, B. Gender and inequality in a postcolonial context of large-scale capitalist projects in the Markham Valley, Papua New Guinea. Aust. J. Anthropol. 2018, 29, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.; Beer, B. Wampar—English Dictionary with an English—Wampar Finder List; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J. House, Family, Kinship: Domestic Terminologies: House, household, family. In Historical Handbook of the Domestic Sphere in Europe; Eibach, J., Lanzinger, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H. (Ed.) Wampar: Berichte über die Alte Kultur Eines Stammes in Papua New Guinea; Übersee-Museum Bremen: Bremen, Germany, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hrdy, S.B. Mother Nature. In Maternal Instincts and How They Shape the Human Species; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, J.; Thomas, L.M. (Eds.) Love in Africa; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, J.S.; Wardlow, H. (Eds.) Modern Loves. In The Anthropology of Romantic Courtship & Companionate Marriage; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heiman, R.; Freeman, C.; Liechty, M. (Eds.) The Global Middle Classes: Theorizing through Ethnography; Sar Press: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker, L.; O’Kane, D.; Scharrer, T. (Eds.) Middles Classes in Africa: Changing Lives and Conceptual Challenges; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lentz, C. African middle classes: Lessons from transnational studies and a research agenda. In The Rise of Africa’s Middle Class; Melber, H., Ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2016; pp. 17–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rosi, P.; Zimmer-Tamakoshi, L. Love and Marriage Among the Educated Elite in Port Moresby. In The Business of Marriage: Transformations in Oceanic Matrimony; Marksbury, R., Ed.; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA; London, UK, 1993; pp. 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- King, M. Elites, Suburban Commuters and Squatters. The Emerging Urban Morphology of Papua New Guinea. In Modern Papua New Guinea; Zimmer-Tamakoshi, L., Ed.; Thomas Jefferson University Press: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1998; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J. ‘Grassroots’, ‘Elites’ and the New ‘Working Class’ of Papua New Guinea. In Brief; State, Society & Governance in Melanesia; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2014; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J. Fast Money Schemes Hope and Deception in Papua New Guinea; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.; Macintyre, M. Christian Marriage, Money Scams, and Melanesian Social Imaginaries. Oceania 2014, 84, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewertz, D.; Errington, F.K. Emerging Class in Papua New Guinea: The Telling of a Difference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gewertz, D. Retelling Chambri Lives: Ontological Bricolage. Contemp. Pac. 2016, 28, 347–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coe, C. What is the impact of transnational migration on family life? Women’s comparisons of internal and international migration in a small town in Ghana. Am. Ethnol. 2011, 38, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, C. The Scattered Family: Parenting, African Migrants, and Global Inequality; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parreñas, R.S. Long distance intimacy: Class, gender, and intergenerational relations between mothers and children in Filipino transnational families. Glob. Netw. 2005, 5, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreñas, R.S. Children of Global Migration: Transnational Families and Gendered Woes; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Drotbohm, H. Horizons of long-distance intimacies: Reciprocity, contribution and disjuncture in Cape Verde. Hist. Fam. 2009, 14, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drotbohm, H. Familie als zentrale Berechtigungskategorie der Migration: Von der Transnationalisierung der Sorge zur Verrechtlichung sozialer Bindungen [Family as a category of entitlement for migration: From the transnationalisation of the concern to the juridification of social bonds]. In Kultur, Gesellschaft, Migration: Die Reflexive Wende in der Migrationsforschung [Culture, Society, Migration: The Reflexive Turn in the Studies of Migration]; Nieswand, B., Drotbohm, H., Eds.; VS Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alber, E.; Notermans, C.; Martin, J. (Eds.) Child Fostering in West Africa; New Perspectives on Theory and Practices; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Archambault, C. Fixing families of mobile children: Recreating kinship and belonging among Maasai adoptees in Kenya. Childhood 2010, 17, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinaweaver, J.B. The Circulation of Children: Kinship, Adoption, and Morality in Andean Peru; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leinaweaver, J.B.; Marre, D.; Frekko, S.E. ‘Homework’ and Transnational Adoption Screening in Spain: The Co-Production of Home and Family. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2017, 23, 562–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The Dialectics of Shopping; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. What is a Relationship? Is Kinship Negotiated Experience? Ethnos 2007, 72, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bales, R.F.; Parsons, T. Family, Socialization, and Interaction Process; Routledge: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, A. Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Impact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakody, R.; Thornton, A.; Axinn, W. (Eds.) International Family Change: Ideational Perspectives; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. Family Connections: An Introduction to Family Studies; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. Acquaintances: The Space between Intimates and Strangers; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. Rethinking Family Practices; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Widmer, E.D. Family configurations. A Structural Approach to Family Diversity; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nave-Herz, R. Familie Heute: Wandel der Familienstrukturen und Folgen für die Erziehung [Family Today: Change of the Family Structures and Consequences for the Education]; Primus Verlag: Darmstadt: Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, L. Intimacy: Personal Relationships in Modern Societies; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, L. Intimacy Transformed? A Critical Look at the ‘Pure Relationship’. Sociology 1999, 33, 477–494. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, L. Intimacy as a Concept: Explaining Social Change in the Context of Globalisation or Another Form of Ethnocentricism? Sociol. Res. Online 2011, 16, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.A. African Models in the New Guinea Highlands. Man 1962, 62, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacalzo, D.; Beer, B.; Schwoerer, T. Mining narratives, the revival of «clans» and other changes in Wampar social imaginaries: A case study from Papua New Guinea. Journal de la Société des Océanistes 2014, 138–139, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacalzo Schwoerer, D. Transformations in kinship, land rights and social boundaries among the Wampar in Papua New Guinea and the generative agency of children of interethnic marriages. Childhood 2012, 19, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacalzo Schwoerer, D. Processes of becoming: Transcultural socialization and childhood among the Wampar. Tsantsa 2011, 16, 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, B.; Schroedter, J.H. Social Reproduction and Ethnic Boundaries: Marriage Patterns through Time and Space Among the Wampar, Papua New Guinea. Sociologus 2014, 64, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Tamakoshi, L. Development and Ancestral Gerrymandering: Schneider in Papua New Guinea. In The Cultural Analysis of Kinship: The Legacy of David M. Schneider (187–203); Feinberg, R., Ottenheimer, M., Eds.; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, D. A Critique of the Study of Kinship; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Strathern, M. Kinship, Law and the Unexpected. Relatives Are Always a Surprise; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, J. After Kinship; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Strathern, M. The Gender of the Gift; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1988; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, S. On Kinship and Marriage: A Critique of the Genetic and Gender Calculus of Evolutionary Psychology. In Complexities Beyond Nature & Nurture; McKinnon, S., Silverman, S., Eds.; University of Chicage Presss: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 2005; pp. 106–131. [Google Scholar]

- Weismantel, M. Making Kin: Kinship Theory and Zumbagua Adoptions. Am. Ethnol. 1995, 22, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godelier, M. The Metamorphosis of Kinship; Verso: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, J.F. The Incorporated What Group: Ethnographic, Economic and Ideological Perspectives on Customary Land Ownership in Contemporary Papua New Guinea. Anthropol. Forum 2013, 23, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Independent State of Papua New Guinea. Land Registration (Amendment) Act; Independent State of Papua New Guinea: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2009.

- Macintyre, M. The Persistence of Inequality. Women in Papua New Guinea since Independence. In Modern Papua New Guinea; Zimmer-Tamakoshi, L., Ed.; Thomas Jefferson University Press: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1998; pp. 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Filer, C.; Le Meur, P.-Y. (Eds.) Large-Scale Mines and Local-Level Politics between New Caledonia and Papua New Guinea; Australian National University Press: Canberra, Australian, 2017; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Minnegal, M.; Lefort, S.; Dwyer, P.D. Reshaping the Social: A Comparison of Fasu and Kubo-Febi approaches to Incorporating Land Groups. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 2015, 16, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, J. ‘Ol Meri Bilong Wok’ (Hard-working women): Women, work and domesticity in Papua New Guinea. In Divine Domesticities: Christian Paradoxes in Asia and the Pacific; Choi, H., Jolly, M., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2014; pp. 167–197. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, S.; Allen, M.; Filer, C. (Eds.) Kastom, Property and Ideology: Land Transformations in Melanesia; Australian National University Press: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H. Gabsongkeg ′71: Verwandtschaft, Siedlung und Landbesitz in Einem Dorf in Neuguinea [Gabsongkeg ′71: Kinship, Settlement and Land Ownership in a Village in New Guinea]; Klaus Renner: München, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bainton, N. Keeping the Network out of view: Mining, Distinctions and Exclusion in Melanesia. Oceania 2009, 79, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilberthorpe, E. Community development in Ok Tedi, Papua New Guinea: The role of anthropology in the extractive industries. Community Dev. J. 2013, 48, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guddemi, P. Continuities, Contexts, Complexities, and Transformations: Local Land Concepts of a Sepik People Affected by Mining Exploration. Anthropol. Forum 1997, 7, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwoerer, T. (Forthcoming). Plantations, Incorporated Land Groups, and Emerging Inequalities among the Wampar of Papua New Guinea. In Capital and Inequality in Rural Papua New Guinea; Asia-Pacific Environment, Monographs; Beer, B., Schwoerer, T., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H. Randfiguren der Ethnologie. Gelehrte und Amateure, Schwindler und Phantasten [Marginal Actors in Ethnology. Scholars and Amateurs, Impostors and Dreamer ]; Kapitel 6: Der Missionar (Chapter 6: The missionary); Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spellenberg, H. Er Führte Mich auf Rechter Straße: Ein Stück Lebensweg von Neuguinea nach Württemberg 1917–1948 [He Led Me on the Right Road: A Piece of the Path of Life from New Guinea to Württemberg 1917–1948]; Eigenverlag: Reutlingen, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Langmore, D. The object lesson of a civilised, Christian home. In Family and Gender in the Pacific: Domestic Contradictions and the Colonial Impact; Jolly, M., Macintyre, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; pp. 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, M.; Macintyre, M. Macintyre Introduction. In Family and Gender in the Pacific: Domestic Contradictions and the Colonial Impact; Jolly, M., Macintyre, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wardlow, H. All’s fair when love is war. Romantic passion & companionate marriage among the Huli of Papua New Guinea. In Modern Loves: The Anthropology of Romantic Courtship and Companionate Marriage; Hirsch, J.S., Wardlow, H., Eds.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2006; pp. 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wardlow, H. The Task of the HIV Translator: Transforming Global AIDS Knowledge in an Awareness Workshop. Med. Anthropol. 2012, 31, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardlow, H. Paradoxical Intimacies: The Christian Creation of the Huli Domestic Sphere. In Divine Domesticities: Christian Paradoxes in Asia and the Pacific; Choi, H., Jolly, M., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2014; pp. 325–345. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education, Government in Papua New Guinea. Social Science Pupil Book; Department of Education: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 1987.

- Fischer, H. Namen als ethnographische Daten [Names as ethnographic data]. In Abhandlungen und Berichte des Staatlichen Museums für Völkerkunde Dresden; Akademie-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1975; Volume 34, pp. 629–654. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H. Wörter und Wandel: Ethnographische Zugänge über die Sprache [Words and Change: Ethnographic Approaches through Language]; Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Independent State of Papua New Guinea. Constitution of the Independent State of Papua New Guinea; Independent State of Papua New Guinea: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 1975.

- Independent State of Papua New Guinea. Familiy Protection Act 2013; Independent State of Papua New Guinea: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2013.

- Therborn, G. Family Systems of the World: Are They Converging? In The Wiley Blackwell Companion on the Sociology of Families; Treas, J., Scott, J., Richards, M., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Canetto, S. What is a normal family? Common assumptions and current evidence. J. Prim. Prev. 1996, 17, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, B.; Church, W. Roads to Inequality: Infrastructure and Historically Grown Regional Differences in the Markham Valley, Papua New Guinea. Oceania 2019, 89, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H. Weisse und Wilde: Erste Kontakte und Anfänge der Mission [Whites and Savages: First Contacts and the Beginning of the Mission]; Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H. Geister und Menschen: Mythen, Märchen und neue Geschichten [Ghosts and Humans: Myths and New Stories]; Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. From dividual and individual selves to porous subjects. Aust. J. Anthropol. 2012, 23, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, A. To Excel at bridewealth, or ceremonies of Office. Anthropol. Today 2017, 33, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beer, B. ‘Clan’ and ‘Family’: Transformations of Sociality among the Wampar, Papua New Guinea. Histories 2022, 2, 15-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2010002

Beer B. ‘Clan’ and ‘Family’: Transformations of Sociality among the Wampar, Papua New Guinea. Histories. 2022; 2(1):15-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeer, Bettina. 2022. "‘Clan’ and ‘Family’: Transformations of Sociality among the Wampar, Papua New Guinea" Histories 2, no. 1: 15-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2010002

APA StyleBeer, B. (2022). ‘Clan’ and ‘Family’: Transformations of Sociality among the Wampar, Papua New Guinea. Histories, 2(1), 15-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2010002