Abstract

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic condition that causes the degeneration of motor neurons in the spinal cord. Newborn blood spot (NBS) screening can potentially enable diagnosis before symptoms, and presymptomatic treatment is considered to be more effective than symptomatic treatment. In this paper, we present an overview of a cost-effectiveness model of NBS screening for SMA in the UK, informed by key clinical trials and the relevant published literature. Our analyses suggest that implementing screening could result in better outcomes and lower costs compared to the current approach of no screening plus treatment. However, several uncertainties and limitations of the model remain. These include uncertainty in the reimbursement status of nusinersen and risdiplam in the future; the ‘actual’ costs of treatments, as they are under confidential commercial agreements; uncertainty in the long-term effectiveness of presymptomatic and symptomatic treatment; and uncertainty around the incidence of SMA and the costs and the accuracy of NBS screening. An SMA in-service evaluation (ISE) that could capture data specific to the UK is under consideration, and an appropriately designed ISE with ongoing data collection could support periodic updates of clinical and cost-effectiveness estimates of NBS screening for SMA in the UK.

1. Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive disease involving degeneration of the alpha motor neurons in the spinal cord, resulting in symmetrical muscle weakness and atrophy, with the impact upon the muscles used to support breathing leading to lethal consequences. SMA is traditionally categorised into five different types according to the age of symptom presentation and diagnosis, from type 0 (the most severe, identified at birth) to type 4 (becoming symptomatic in adulthood and usually constituting mild disease). The vast majority of SMA cases (95%) are due to a homozygous deletion in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, which leads to a decrease in the functional SMN protein and ultimately leads to patients developing SMA. The related survival motor neuron 2 (SMN2) gene can also produce SMN protein, but only approximately 10% of the SMN protein coming from this route is functional [1,2].

There are now three treatments available for patients with SMA: nusinersen (Spinraza) and risdiplam (Evrysidi) are recurrent treatments, while onasemnogene abeparvovec (Zolgensma) is a one-off gene therapy. The national criteria for treatment in England are determined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). From the limited evidence that is available, it appears that presymptomatic treatment is more effective than symptomatic treatment, and newborn blood spot (NBS) screening potentially allows babies to be diagnosed before they show signs or symptoms [3,4,5,6]. Decision making on treatment options after NBS screening is based on presymptomatic diagnosis using SMN2 copy numbers, with a higher number of SMN2 copies generally correlating with reduced disease severity but imperfectly correlating with clinically defined SMA types [7].

In the four UK countries, the UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) advises ministers and the National Health Service (NHS) about all aspects of screening, including the case for introducing new conditions to the NHS NBS Screening Programme [8,9]. The UK NSC also maintains oversight of the evidence relating to the balance of good and harm and the impact on healthcare costs and health consequences of existing, new, or modified screening programmes [9]. Decision-analytic models offer a structured framework to simulate the potential pathways of care for different strategies of screening programmes compared with no screening and a mechanism to bring together all available, relevant evidence on effectiveness, harms, health benefits, and healthcare costs. Decision-analytic modelling to estimate cost-effectiveness (also referred to as ‘modelling studies’) is increasingly being used in the development of UK NSC recommendations on NBS screening [10]. Modelling studies can usefully address the absence of clinical trial evidence comparing screening with no screening or current practice. However, modelling studies are based on data from different sources and are constrained by a range of issues that are intrinsic to the rare disease setting. These include small sample sizes of clinical studies; lack of head-to-head data on treatment options; uncertainty in the benefits and harms conceptualised in NBS screening models; and limited availability of long-term data relating to the modelled strategies. These limitations create uncertainty about both clinical and cost-effectiveness results and their generalisability to UK healthcare jurisdictions [10,11,12,13].

In the UK, the UK NSC makes use of in-service evaluation (ISE) activity to test a proposal for a new screening programme or a change to an existing one within ‘real world’ NHS service delivery. The primary aim of ISE is to deliver robust evidence, generated in an NHS setting, to support a UK NSC recommendation to the four UK nations. When the remaining evidence gaps can only feasibly be filled by large-scale work in live NHS services, then the UK NSC can recommend ISE work [14]. Recently, an ISE for newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) was completed in England [15,16], and another one in the cancer screening setting has also recently been commissioned [17]. There are several uncertainties that specifically relate to estimating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of NBS screening for SMA in the UK. These include uncertainty in accurately predicting severity or type of SMA from genetic information alone, reimbursement status of symptomatic and presymptomatic treatments for SMA currently in England in the NHS (NICE is currently appraising nusinersen and risdiplam for symptomatic and presymptomatic treatment of SMA with the recommendations scheduled for early 2026 [6]), and the cost of treatments (all the treatments for SMA are under confidential patient access schemes in the NHS, and as such, the “actual” prices of these treatments are unknown).

A ‘flexible’ model, commissioned by the UK NSC, was developed to address these uncertainties. This paper presents a brief overview of the model and describes how the modelling results assisted in identifying priorities for a future ISE of NBS screening for SMA.

2. Methods

The model structure and inputs were developed through findings from cost-effectiveness models of NBS screening for SMA [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], and reviews on presymptomatic treatment for SMA and accuracy of newborn screening for SMA [27,28]. In addition, 4 online workshops with key experts were conducted between September 2023 and November 2024, with around 20 participants in each workshop. The workshops elicited expert input to finalise the model assumptions, to identify the best sources of data for populating the model, to address key uncertainties in the modelling and input data, and to identify any changes needed following presentation of the preliminary results.

2.1. Model Overview

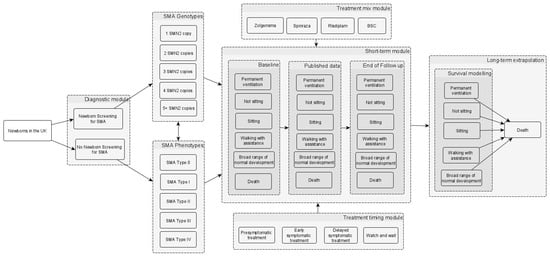

A model was developed to estimate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of NBS screening for SMA, informed by key clinical trials and the relevant published literature [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. As shown in Figure 1, the model uses a decision tree (for the screening phase), followed by a 3-year short-term model (for incorporating treatment effectiveness based on clinical study data) and long-term modelling (for extrapolation based on survival modelling) using a six-month model cycle. A best supportive care (BSC) arm (BSC refers to symptom management/watch and wait for cases of milder disease or it refers to palliative type care for patients with SMA type 0 and those with very severe disease) was also included as a comparator to explore the magnitude of clinical effect of the three treatments in settings with and without screening, similar to the approach used in other evaluations [38,39]. The aim of including BSC was to provide further perspective on the improvement of outcomes from SMA within these respective settings. While the comparator for cost-effectiveness was ‘no screening’ (i.e., use of the three treatments in clinically diagnosed SMA), the BSC arm provided security against the uncertainty relating to the status of two of the drugs in the NICE evaluation process. For example, if risdiplam and/or nusinersen are not approved for routine use in the NHS by NICE [6], it will be important to capture the untreated groups as part of both the no screening and screening arms in future iterations of the model.

Figure 1.

Simplified model structure of NBS screening for SMA. The model begins with the population (a hypothetical cohort of newborns in the UK). The population in the no NBS screening arm is the same as in the NBS screening arm in terms of the incidence of SMA and the proportions of different genotypes and phenotypes (i.e., the different SMA types). The box labelled “short-term module” represents a 3-year short-term model which incorporates the motor function milestones gained (i.e., sitting, walking with assistance, and broad range of normal development), the need for permanent ventilation, the time to death, and the treatment effectiveness based on clinical study data. In the short-term module box, the “baseline”, “published data”, and “end of follow-up” in the different columns relate to the 6-monthly time intervals, where data on the proportions of patients in the different health states are sourced from the key clinical studies of the different treatments. The long-term model on the right involves the extrapolation of the motor function milestones, the need for permanent ventilation, and mortality, which are assumed to be conditional on the health states reached by the end of the 3-year model. The long-term model uses 6-monthly time cycles to estimate the lifetime costs and quality-adjusted life years. Although not depicted in the figure, a BSC scenario was also included as a comparator. Abbreviations: BSC: best supportive care; NBS: newborn blood spot; SMA: spinal muscular atrophy; SMN: survival motor neuron. Source: [40].

2.2. Model Inputs

The model inputs are sourced from the relevant published literature and supplemented with expert opinion where necessary, as shown in Table 1. A brief overview of the model inputs is presented here, and a detailed description of the model inputs, sources, and assumptions is presented in the Supplementary Material (File S1).

Table 1.

Summary of model inputs and sources.

The epidemiological data includes the incidence of SMA and the proportions of different genotypes, with the mapping between genotypes and phenotypes ensuring that the population in the no NBS screening arm is the same as in the NBS screening arm.

The treatment effectiveness is based on the proportions of patients receiving the different treatments (zolgensma, nusinersen, risdiplam, or BSC), either presymptomatically or symptomatically, according to the number of SMN2 copies (1, 2, 3, 4, 5+) in the NBS screening arm and the different SMA types (0, 1, 2, 3, 4) in the no NBS screening arm.

Data on motor function milestones, permanent ventilation, and mortality over different time points were extracted from the relevant trials/studies and additional follow-up data from registry data [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Long-term survival is assumed conditional on health states, so that each model health state (permanent ventilation (PV), not sitting, sitting, walking with assistance, and broad range of normal development (BRND)) has a mortality risk, and the impact of SMA symptoms on the patient is modelled using health state-specific costs and utilities.

The costs of NBS screening, costs of confirmatory tests, costs of symptomatic diagnosis, and costs of treatments were sourced from the published literature and expert opinion.

2.3. Model Analyses

The base case analysis in the model used an NHS and personal social services perspective, using the mean values of parameters to estimate cost-effectiveness [i.e., cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)] results. To account for non-linearities amongst the model inputs, probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was undertaken using appropriate distributions to represent the uncertainty in the data inputs. The treatment prices used in the model are those publicly reported (list prices—see Table S16 in Supplementary Material, File S1), as the actual prices paid by the NHS are confidential. Sensitivity analyses assuming discounted prices were undertaken as the NHS is sometimes able to negotiate confidential discounts for individual drugs. The base case analysis included all available treatments at list price, and another analysis assuming a 30% discount for Zolgensma and a 90% discount for risdiplam and nusinersen. Zolgensma is a one-off treatment, so a lower discount was assumed, while the other two drugs have to be administered through the patient’s lifetime, so a greater discount was assumed. Scenario analyses were also performed using Zolgensma only, using list price and price discount, as presented elsewhere [40].

3. Results

3.1. Short-Term Outcomes

Table 2 provides an overview of the proportion of SMA cases identified symptomatically and presymptomatically in the different arms of the model. Using an annual cohort of 600,000 newborns in the UK, and an incidence rate of 1 in 8200 for SMA, results in 73.17 cases of SMA. In the BSC arm, it was assumed that all 73.17 cases of SMA would be diagnosed symptomatically and would receive BSC. In the No NBS screening arm of the model, 0.73 cases of SMA were detected presymptomatically via family history, with the remaining 72.44 cases detected symptomatically. In the NBS screening arm of the model, most of the SMA cases (n = 69.44) were detected presymptomatically, with the remaining 3.73 cases detected symptomatically (i.e., the 5% of patients who do not have homozygous deletions in SMN1).

Table 2.

Patients identified by SMA type and SMN2 copy numbers.

3.2. Mid-Term Outcomes (Outcomes at the End of 3 Years)

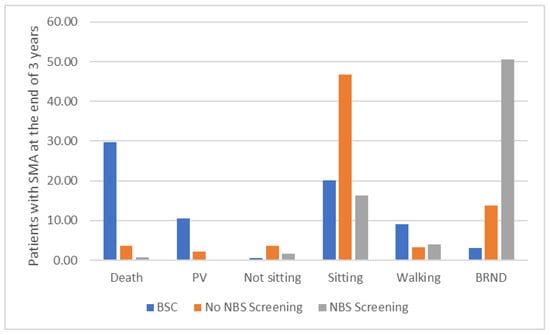

Figure 2 presents the comparison between the BSC arm, the No NBS screening arm, and the NBS screening arm at the end of the 3 years. This suggests that compared with the current practice (i.e., assuming all three drugs are available), NBS screening would prevent 2 cases requiring permanent ventilation, around three early deaths, and about 30 cases who do not progress beyond a sitting state. NBS screening also enables about 37 more cases who experience few or no significant limitations. However, NBS screening will identify around three cases with five SMN2 copies who will not experience symptoms until adulthood, if at all, and identification may even be detrimental to their health and wellbeing. In the BSC arm, as the patients are detected symptomatically and only receive BSC (i.e., no pharmacological treatment), the outcomes at the end of the 3 years suggest that there are many deaths (29.69) and patients on permanent ventilation (10.54).

Figure 2.

Patients at the end of 3 years in the BSC arm, the No NBS screening arm, and the NBS screening arm. The figure shows that, at the end of the 3 years, in the BSC arm, as the patients are detected symptomatically and only receive BSC (i.e., no pharmacological treatment), there are many deaths and patients on permanent ventilation. In the No NBS screening arm, where patients are detected symptomatically and receive pharmacological treatment, the number of deaths and patients on permanent ventilation are reduced substantially, but most of the patients are in the sitting health state, with only a few patients achieving walking with assistance or broad range of normal development. In the NBS screening arm, where most patients receive pharmacological treatment presymptomatically, the number of deaths and patients on permanent ventilation and patients in a sitting health state are further reduced, with most of the patients achieving broad range of normal development. Abbreviations: BRND: broad range of normal development; BSC: best supportive care; NBS: newborn blood spot; PV: permanent ventilation.

3.3. Long-Term Outcomes

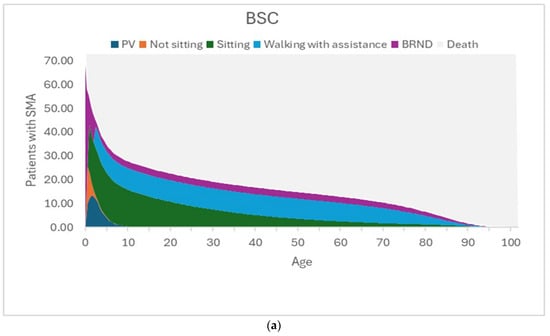

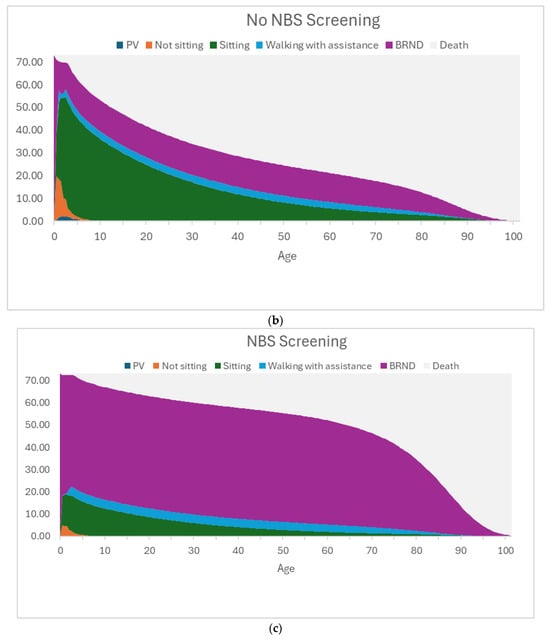

The model assumes that the motor function milestones achieved at the end of the 3-year short-term model are sustained until death, and the mortality in the long-term is modelled using survival curves for each of the motor function milestones based on data from the published literature [46,47]. Figure 3a–c present the time spent in different health states in the BSC arm, the No NBS screening arm, and the NBS screening arm.

Figure 3.

(a) Graphical representation of the time spent in each health state for the best supportive care arm. The figure shows the time spent in the different health states by the 73.17 patients with SMA. In this BSC arm, there are many deaths and patients on PV, with some patients in the sitting health state and a few in the walking with assistance health state. The lower survival of patients in the permanent ventilation and sitting health states is reflected in the long-term outcomes of patients in BSC. (b) Graphical representation of the time spent in each health state for the No NBS screening arm. The figure shows the time spent in the different health states by the 73.17 patients with SMA. In this No NBS screening arm, most of the patients are in the sitting health state and some are in the BRND state, and only a few patients are in the walking with assistance state. The survival in the No NBS screening arm is higher than that in the BSC arm due to lower short-term deaths and fewer patients in PV, but the lower survival of patients in sitting health states is reflected in the long-term outcomes of patients in the No NBS screening arm. (c) Graphical representation of the time spent in each health state for the NBS screening arm. The figure shows the time spent in the different health states by the 73.17 patients with SMA. In this NBS screening arm, the number of deaths and patients on PV and patients in the sitting health state are further reduced, with most of the patients achieving BRND. The survival in the NBS screening arm is much higher than that in the No NBS screening arm due to lower short-term deaths, fewer patients in PV, and fewer patients in sitting health states. Most of the patients in the NBS screening arm are in the BRND state (which assumes survival of the general population), and this is reflected in better long-term outcomes of patients in the NBS screening arm. Abbreviations: BRND: broad range of normal development; BSC: best supportive care; NBS: newborn blood spot; PV: permanent ventilation. Source: [40].

In the BSC arm, the majority of patients die or are receiving PV, with smaller numbers of patients limited to the sitting health state, and a few achieving the walking with assistance and BRND health states. The lower survival of patients in PV and sitting health states is reflected in the long-term outcomes of patients in this BSC arm.

In the No NBS screening arm, most of the patients are in the sitting health state, and some are in the BRND state, and only a few patients are in the walking with assistance state. The lower survival of patients in sitting health states is reflected in the long-term outcomes of patients in the No NBS screening arm.

In the NBS screening arm, the number of deaths and patients on PV and patients in a sitting health state are reduced, with most of the patients achieving BRND. The survival in the NBS screening arm is much higher than that in the BSC and No NBS screening arms due to fewer early deaths, fewer patients in PV, and fewer patients in sitting health states. Most of the patients in the NBS screening arm are in the BRND state (whose survival is similar to that of the general population), and this is reflected in better long-term outcomes of patients in the NBS screening arm.

3.4. Cost-Effectiveness Results

Table 3 presents the cost-effectiveness results of the base case analysis, i.e., using all the treatments currently eligible (see report for the treatment mix describing the proportions of patients receiving the different treatments [40]) and using list prices and treatments assuming price discounts. Table 3 suggests higher total QALYs and lower total costs in the NBS screening arm compared to the No NBS screening arm, resulting in NBS screening dominating the No NBS screening arm. When using list prices, PSA results presented in the Supplementary Material (File S2) suggest that, at a threshold of GBP 20,000/QALY, NBS screening has a 90% probability of being cost-effective compared to No NBS screening. However, it should be noted that No NBS screening is not cost-effective compared to BSC, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of GBP 606,516/QALY. The ICER of NBS screening compared to BSC is GBP 219,393/QALY, suggesting that NBS screening is not cost-effective when compared to BSC at the typical NICE thresholds of GBP 20,000 to GBP 30,000/QALY.

Table 3.

Cost-effectiveness results using all available treatments, using list prices and price discounts.

Table 3 also presents the cost-effectiveness results of the analysis using a 30% discount for Zolgensma and a 90% discount for risdiplam and nusinersen. When using price discounts, NBS screening is dominating the No NBS screening arm, and the PSA results presented in Supplementary Material (File S2) suggest 100% probability of NBS screening being cost-effective compared to No NBS screening at thresholds greater than GBP 20,000/QALY. However, it should be noted that No NBS screening is not cost-effective compared to BSC with an ICER of GBP 210,930/QALY. The ICER of NBS screening compared to BSC is GBP 62,217/QALY, which could be considered cost-effective at thresholds of GBP 100,000/QALY used for NICE highly specialised technologies (HSTs) but not cost-effective at the typical NICE thresholds of GBP 20,000 to GBP 30,000/QALY.

4. Discussion

A model was developed to estimate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of NBS for SMA, informed by key clinical trials and the relevant published literature. However, there are several key uncertainties and limitations of the model. NICE is currently appraising nusinersen and risdiplam for symptomatic and presymptomatic treatment of SMA, with the recommendations scheduled for November 2025. As such, there is substantial uncertainty in the reimbursement status of the treatments in the future. Also, the costs of treatments are under confidential patient access schemes in the NHS, and as such, the “actual” prices of these treatments are unknown. There is also uncertainty in the effectiveness of presymptomatic and symptomatic treatment, with limited data on longer-term outcomes [3,4,5,6]. In addition, there is uncertainty in terms of the impact of diagnostic delay during the screening process on the number of patients becoming symptomatic with Type 1 SMA, and subsequently, the impact on outcomes achieved. There is also uncertainty around the incidence of SMA, and the cost, and the accuracy of NBS screening for SMA.

A Health Technology Assessment (HTA) commissioning brief for an ISE for SMA that would compare screened with unscreened populations within England is currently underway to address these uncertainties and provide UK-specific data [55]. Priorities identified for this ISE as part of the modelling work were: epidemiology, feasibility of real-world implementation, including clinical pathway, test methodology and accuracy, screening programme performance, acceptability of screening, and data on treatment effectiveness (particularly longer-term outcomes) and health state costs. Through real-life implementation in live NBS screening services for SMA, an appropriately designed ISE could provide more information on the epidemiology of SMA (i.e., data on incidence, breakdown of SMA types, and copy numbers) and the accuracy and costs of the NBS screening. The model assumed 99.9% sensitivity and specificity for the initial PCR test (excluding other variants, i.e., the 5% of patients who do not have homozygous deletions in SMN1), and the costs were based on expert opinion and a previous SCID evaluation [15,51]. As such, the ISE could provide more information about the clinical pathway and the associated costs/implications of NBS screening.

An ISE could also evaluate the timescales that can be met in UK services at important stages of the screening pathway, including when screening results become available, the timing of clinical referral, and starting treatment, if offered and accepted. The model assumed that around half of the patients diagnosed with two SMN2 copies would show symptoms by treatment start, and these patients would receive early symptomatic treatment, which is likely to be less effective than presymptomatic treatment. An ISE could also address this uncertainty with real-world data on diagnostic and treatment delay, and the effectiveness of early symptomatic treatment.

Expert opinion was solicited to specify the treatment mix in the model (i.e., the proportions of patients receiving the different treatments, according to the different SMN2 copies in the NBS screening arm and SMA types in the no NBS screening arm), and published data from pivotal trials was used to estimate the treatment effectiveness [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. By the time that the ISE begins, NICE will have made recommendations about treatments (currently scheduled for early 2026); therefore, the ISE could provide information on which treatments patients receive in practice, the effectiveness of treatment for presymptomatic and asymptomatic patients, and the likelihood of patients becoming symptomatic due to delays in diagnosis. As such, an ISE could provide information on what treatments patients receive in practice and the treatment effectiveness in presymptomatic and early symptomatic treatment. A number of studies have been published in recent years [56,57,58,59], but uncertainties still remain. Higher quality evidence relies on a robust comparator and, in this rare disease setting, discussion about design options may need to consider the combination of prospective and retrospective datasets to improve the reliability of modelled comparisons.

As the treatments are quite new, further data on the clinical effectiveness in terms of the motor function milestones (i.e., sitting or walking with assistance and BRND) of treating presymptomatic babies is needed, and this could be provided by an ISE. Data on short-term outcomes will contribute evidence on the clinical effectiveness of screening at different time points (e.g., 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years). However, data on longer-term outcomes (e.g., 5 years and beyond) is an equally, if not more, important outcome. Despite the uncertainty on cost, it is assumed that the treatments are expensive. Understanding the clinical value over time is a key issue relating to economic investment, but also for clinicians who need to set realistic expectations for parents of affected babies who may be concerned, for example, about waning treatment effectiveness.

The model used published data for the health state costs and utilities to account for the impact of NBS screening for SMA symptoms on the patient, and the data from an ISE can provide more direct information regarding the quality of life and costs of the different health states. The recent SCID ISE [15,16] provides an example of the way in which data collection on these and other issues improved the quality of the modelled analysis of screening to inform UK NSC discussion. This might provide a useful point of reference for the design of an SMA ISE.

As the costs of treatments are under confidential patient access schemes, the list prices for the treatment costs were used in the base case analyses of the model, and sensitivity analyses were performed using hypothetical discounts. It is not clear whether an ISE would have access to this confidential pricing data, and as such, there is still uncertainty regarding the treatment costs to the NHS.

5. Conclusions

The model was populated using the best available data from the published literature, but key uncertainties and limitations remain. However, as outlined in this paper, an SMA ISE is under consideration, which could capture data specific to the UK. An appropriately designed ISE and ongoing data collection could support updated, periodic estimates of clinical and cost-effectiveness of NBS screening for SMA in the UK.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijns12010003/s1. File S1: Model Inputs; File S2: Results of probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Author Contributions

P.T.: Conceptualisation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, and writing—reviewing and editing. A.B.: Conceptualisation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing—reviewing and editing. R.K.: Writing—reviewing and editing. J.M.: Conceptualisation, supervision, and writing—reviewing and editing. C.V.: Conceptualisation, supervision, and writing—reviewing and editing. M.L.: Writing—reviewing and editing. S.L.: Conceptualisation, project administration, supervision, and writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The clinical and cost-effectiveness model for newborn screening for SMA was commissioned by the UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC), hosted at the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), and carried out by the Sheffield Centre for Health and Related Research (SCHARR) at the University of Sheffield. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK NSC, DHSC, or the University of Sheffield.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Silvia Lombardo, John Marshall, Cristina Visintin, and Miranda Lawton are employed by the UK NSC, hosted at the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). Praveen Thokala is the Director of PT Health Economics Ltd. and has performed consultancy services advising Roche and Novartis on cost-effectiveness analyses of SMA treatments. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wirth, B. Spinal Muscular Atrophy: In the Challenge Lies a Solution. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, T.W.; Swoboda, K.J.; Scott, H.D.; Hejmanowski, A.Q. Homozygous SMN1 Deletions in Unaffected Family Members and Modification of the Phenotype by SMN2. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2004, 130A, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Onasemnogene Abeparvovec for Treating Presymptomatic Spinal Muscular Atrophy [HST24]; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Risdiplam for Treating Spinal Muscular Atrophy [TA 755]; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nusinersen for Treating Spinal Muscular Atrophy [TA588]; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nusinersen and Risdiplam for Treating Spinal Muscular Atrophy (Review of TA588 and TA755) [ID6195]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta11386 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Calucho, M.; Bernal, S.; Alias, L.; March, F.; Vencesla, A.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, F.J.; Aller, E.; Fernandez, R.M.; Borrego, S.; Millan, J.M.; et al. Correlation between SMA Type and SMN2 Copy Number Revisited: An Analysis of 625 Unrelated Spanish Patients and a Compilation of 2834 Reported Cases. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2018, 28, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC). UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC). Our Governance. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/uk-national-screening-committee/about/our-governance (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC). UK National Screening Committee: About Us. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/uk-national-screening-committee/about (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Lombardo, S.; Seedat, F.; Elliman, D.; Marshall, J. Policy-Making and Implementation for Newborn Bloodspot Screening in Europe: A Comparison between EURORDIS Principles and UK Practice. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2023, 33, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Png, M.E.; Yang, M.; Taylor-Phillips, S.; Ratushnyak, S.; Roberts, N.; White, A.; Hinton, L.; Boardman, F.; McNiven, A.; Fisher, J.; et al. Benefits and Harms Adopted by Health Economic Assessments Evaluating Antenatal and Newborn Screening Programmes in OECD Countries: A Systematic Review of 336 Articles and Reports. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 314, 115428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciatore, P.; Visser, L.A.; Buyukkaramikli, N.; van der Ploeg, C.P.B.; van den Akker-van Marle, M.E. The Methodological Quality and Challenges in Conducting Economic Evaluations of Newborn Screening: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, A.; Holle, R.; John, J. Specific Guidelines for Assessing and Improving the Methodological Quality of Economic Evaluations of Newborn Screening. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC). Guidance UK NSC: Evidence Review Process Updated 26 July 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-nsc-evidence-review-process/uk-nsc-evidence-review-process#products (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC). Newborn Screening Programme SCID. Available online: https://view-health-screening-recommendations.service.gov.uk/scid/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Harris, M. UK NSC Consults on Extending the In-Service Evaluation of Screening for SCID. Available online: https://nationalscreening.blog.gov.uk/2025/08/07/uk-nsc-consults-on-extending-the-in-service-evaluation-of-screening-for-scid/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). 23/106 The Use of HPV Self-Sampling within Cervical Screening Programme. Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/23106-use-hpv-self-sampling-within-cervical-screening-programme (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Weidlich, D.; Bischof, M.; O’Rourke, D. Cost Effectiveness of Heel-Prick Screening Test for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) in Ireland. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2023, 65, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiem, H. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis-Cost-Effectiveness of Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Gesundheitsokonomie Qual. 2022, 27, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjunji, R.; Zhou, J.; Patel, A.; Edwards, M.L.; Harvey, M.; Wu, E.; Dabbous, O. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) in the United States. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidlich, D.; Servais, L.; Kausar, I.; Howells, R.; Bischof, M. Cost-Effectiveness of Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in England. Neurol. Ther. 2023, 12, 1205–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, A.; Rothwell, E.; Botkin, J.R.; Anderson, R.A.; Butterfield, R.J.; Nelson, R.E. Cost-Effectiveness of Nusinersen and Universal Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. J. Pediatr. 2020, 227, 274–280.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangouloff, T.; Thokala, P.; Stevenson, M.D.; Deconinck, N.; D’Amico, A.; Daron, A.; Delstanche, S.; Servais, L.; Hiligsmann, M. Cost-Effectiveness of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Newborn Screening Based on Real-World Data in Belgium. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2024, 34, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.T.; Farrar, M.A.; Wiley, V.; Chambers, G. Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy with Disease-Modifying Therapies: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 1296–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landfeldt, E. The Cost-Effectiveness of Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikanova, R.; van der Schans, S.; Bischof, M.; van Olden, R.W.; Postma, M.; Boersma, C. Cost-Effectiveness of Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in The Netherlands. Value Health 2022, 25, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.; Nalbant, G.; Sutton, A.; Harnan, S.; Thokala, P.; Chilcott, J.; McNeill, A.; Bessey, A. Systematic Review of Newborn Screening Programmes for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.; Nalbant, G.; Sutton, A.; Harnan, S.; Thokala, P.; Chilcott, J.; McNeill, A.; Bessey, A. Systematic Review of Presymptomatic Treatment for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.A.; Farrar, M.A.; Muntoni, F.; Saito, K.; Mendell, J.R.; Servais, L.; McMillan, H.J.; Finkel, R.S.; Swoboda, K.J.; Kwon, J.M.; et al. Onasemnogene Abeparvovec for Presymptomatic Infants with Two Copies of SMN2 at Risk for Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1: The Phase III SPR1NT Trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servais, L.; Finkel, R.; Farrar, M.; Vlodavets, D.; Zanoteli, E.; Al-Muhaizea, M.; Araújo, A.; Nelson, L.; Jaber, B.; Gorni, K.; et al. 21O RAINBOWFISH: 2-Year Efficacy and Safety Data of Risdiplam in Infants with Presymptomatic SMA. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2024, 43, 104441.738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, T.O.; Swoboda, K.J.; De Vivo, D.C.; Bertini, E.; Hwu, W.L.; Finkel, R.S.; Kirschner, J.; Kuntz, N.L.; Nazario, A.N.; Parsons, J.A.; et al. Continued Benefit of Nusinersen Initiated in the Presymptomatic Stage of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: 5-Year Update of the NURTURE Study. Muscle Nerve 2023, 68, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deconinck, N.; Baranello, G.; Boespflug-Tanguy, O.; Day, J.; Klein, A.; Masson, R.; Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska, M.; Mercuri, E.; Rose, K.; Servais, L.; et al. FIREFISH Parts 1 and 2: 36-Month Safety and Efficacy of Risdiplam in Type 1 Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.; Finkel, R.S.; Farrar, M.A.; Tulinius, M.; Krosschell, K.J.; Saito, K.; Gambino, G.; Foster, R.; Bhan, I.; Wong, J.; et al. Nusinersen in Infantile-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Results from Longer-Term Treatment from the Open-Label Shine Extension Study. Neurology 2020, 94, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, E.; Darras, B.T.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Day, J.W.; Campbell, C.; Connolly, A.M.; Iannaccone, S.T.; Kirschner, J.; Kuntz, N.L.; Saito, K.; et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darras, B.T.; Farrar, M.A.; Mercuri, E.; Finkel, R.S.; Foster, R.; Hughes, S.G.; Bhan, I.; Farwell, W.; Gheuens, S. An Integrated Safety Analysis of Infants and Children with Symptomatic Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) Treated with Nusinersen in Seven Clinical Trials. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.A.; Farrar, M.A.; Muntoni, F.; Saito, K.; Mendell, J.R.; Servais, L.; McMillan, H.J.; Finkel, R.S.; Swoboda, K.J.; Kwon, J.M.; et al. Onasemnogene Abeparvovec for Presymptomatic Infants with Three Copies of SMN2 at Risk for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: The Phase III SPR1NT Trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, R.; Boespflug-Tanguy, O.; Darras, B.T.; Day, J.W.; Deconinck, N.; Klein, A.; Mazurkiewicz-Bedziska, M.; Mercuri, E.; Rose, K.; Servais, L.; et al. FIREFISH Parts 1 and 2: 24-Month Safety and Efficacy of Risdiplam in Type 1 SMA. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 395–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, K.; Jones, S.A.; Chakrapani, A.; Vijay, S.; Wu, T.; Church, H.; Chanson, C.; Olaye, A.; Miller, B.; Jensen, I.; et al. Exploring the Cost-Effectiveness of Newborn Screening for Metachromatic Leukodystrophy (MLD) in the UK. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC). Adult Screening Programme Cervical Cancer. Available online: https://view-health-screening-recommendations.service.gov.uk/cervical-cancer/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Sheffield Centre for Health and Related Research (SCHARR). Cost-Effectiveness Modelling of Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy-Version: 2 (FINAL). Available online: https://nationalscreening.blog.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/254/2025/07/2025_UK-NSC-SMA-model-report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Dangouloff, T.; Botty, C.; Beaudart, C.; Servais, L.; Hiligsmann, M. Systematic Literature Review of the Economic Burden of Spinal Muscular Atrophy and Economic Evaluations of Treatments. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller-Felber, W.; Blaschek, A.; Schwartz, O.; Glaser, D.; Nennstiel, U.; Brockow, I.; Wirth, B.; Burggraf, S.; Roschinger, W.; Becker, M.; et al. Newbornscreening SMA-From Pilot Project to Nationwide Screening in Germany. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2023, 10, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vill, K.; Schwartz, O.; Blaschek, A.; Glaser, D.; Nennstiel, U.; Wirth, B.; Burggraf, S.; Roschinger, W.; Becker, M.; Czibere, L.; et al. Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Germany: Clinical Results after 2 Years. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boemer, F.; Caberg, J.H.; Beckers, P.; Dideberg, V.; di Fiore, S.; Bours, V.; Marie, S.; Dewulf, J.; Marcelis, L.; Deconinck, N.; et al. Three Years Pilot of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Newborn Screening Turned into Official Program in Southern Belgium. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, S.; Orstavik, K.; Rowe, A.; Strand, J. National Newborn Screening for SMA in Norway. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2023, 33, S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoretti, C.; Ottonello, G.; Chiarini Testa, M.B.; Mastella, C.; Ravà, L.; Bignamini, E.; Veljkovic, A.; Cutrera, R. Survival of Patients With Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1509–e1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerres, K.; Wirth, B.; Rudnik-Schoneborn, S. Spinal Muscular Atrophy-Clinical and Genetic Correlations. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1997, 7, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Bastida, J.; Pena-Longobardo, L.M.; Aranda-Reneo, I.; Tizzano, E.; Sefton, M.; Oliva-Moreno, J. Social/Economic Costs and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) in Spain. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappenden, P.; Hamilton, J.; Kaltenthaler, E.; Hock, E.; Rawdin, A.; Mukuria, C. Nusinersen for Treating Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Single Technology Appraisal; School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR): Sheffield, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Landfeldt, E.; Edstrom, J.; Sejersen, T.; Tulinius, M.; Lochmuller, H.; Kirschner, J. Quality of Life of Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2019, 23, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessey, A.; Chilcott, J.; Leaviss, J.; de la Cruz, C.; Wong, R. A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Newborn Screening for Severe Combined Immunodeficiency in the UK. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2019, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, M.; Tobin, A.; Coy, L.; McDonald, D.; Hennessy, M.; O’Rourke, D. Room to Improve: The Diagnostic Journey of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2023, 42, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, L.; Vita, G.; Marconi, E.; Taddeo, D.; Davi, M.; Lovato, V.; Cricelli, C.; Lapi, F. Opportunities for an Early Recognition of Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Primary Care: A Nationwide, Population-Based, Study in Italy. Fam. Pract. 2022, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, L.; Cairns, J. Review of Economic Modeling Evidence from NICE Appraisals of Rare Disease Treatments for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2023, 23, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). Spinal Muscular Atrophy Screening. Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/funding/spinal-muscular-atrophy-screening/2025338 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Belter, L.; Taylor, J.L.; Jorgensen, E.; Glascock, J.; Whitmire, S.M.; Tingey, J.J.; Schroth, M. Newborn Screening and Birth Prevalence for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in the US. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariyawasam, D.S.; D’Silva, A.M.; Sampaio, H.; Briggs, N.; Herbert, K.; Wiley, V.; Farrar, M.A. Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Australia: A Non-Randomised Cohort Study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2023, 7, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, H.J.; Kernohan, K.D.; Yeh, E.; Amburgey, K.; Boyd, J.; Campbell, C.; Dowling, J.J.; Gonorazky, H.; Marcadier, J.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; et al. Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Ontario Testing and Follow-up Recommendations. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 48, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, O.; Vill, K.; Pfaffenlehner, M.; Behrens, M.; Weiß, C.; Johannsen, J.; Friese, J.; Hahn, A.; Ziegler, A.; Illsinger, S.; et al. Clinical Effectiveness of Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.