Abstract

A cancer diagnosis has long-term physical and psychological consequences, and patients vary considerably in their mental health outcomes during the disease process. Psychological resilience has been identified as a protective factor, yet the mechanisms through which it influences mental health remain unclear. This study aims to examine the mediating role of psychological flexibility in the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health among individuals diagnosed with cancer. A total of 234 cancer patients participated in this cross-sectional study. Data were collected using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale–Short Form, and the Psychological Flexibility Scale. Path analysis was conducted to test the proposed mediation model. The results indicated that psychological resilience was positively associated with psychological flexibility, and psychological flexibility was negatively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. Psychological flexibility fully mediated the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health. These findings suggest that psychological flexibility plays a key role in explaining how psychological resilience contributes to better mental health outcomes in cancer patients. Interventions aiming to enhance psychological flexibility may therefore be beneficial in psychosocial support programs for individuals coping with cancer.

1. Introduction

Promising developments in medical treatments enable high levels of cure in some types of cancer. As a result of advances in diagnosis and treatment, the cancer process has become a more controllable process [1]. Cancer shows different characteristics depending on the organ in which it is located. Therefore, there are many different types of cancer and conditions. In addition to promising developments regarding treatment processes, there also appears to be an increase in its prevalence. According to the World Health Organization, in 2022 [2], there were 19.9 million reported cancer cases and 9.7 million cancer-related deaths globally. Future projections estimate that by 2045, cumulatively 32.6 million people will be diagnosed with cancer, and 16.9 million will die as a result [3]. In Turkey, 240,000 people were diagnosed with cancer in 2022, with 129,000 cancer-related deaths. Projections indicate that by 2045, there will be 419,000 cases of cancer and 256,000 related deaths in Turkey [3]. Cancer patients endure not only physical challenges but also mental health struggles. Research has revealed that those diagnosed with cancer are at risk of developing psychological disorders, such as major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder [2,4,5,6]. According to a study, one-third of cancer patients were found to have symptoms of depression and anxiety [7]. On the other hand, cancer patients react differently after diagnosis [8,9,10]. When the reasons for these differences are examined, it is seen that there are factors such as behavioral differences, life events, coping styles, personality, and resilience [11].

According to research findings, psychological resilience is pivotal in this context. Psychological resilience is commonly defined as the capacity to adapt successfully to adversity from significant stressors [12]. In the context of chronic illness, such as cancer, resilience reflects individuals’ capacity to maintain daily functioning and psychological stability and to restore emotional equilibrium following disruptions caused by ongoing health-related stressors [13,14]. Importantly, contemporary models conceptualize resilience not merely as a fixed personality trait but as a relatively stable yet context-sensitive psychological resource that can fluctuate depending on situational demands [15,16]. Individuals exhibiting high levels of resilience typically encounter fewer emotional challenges and demonstrate more adept problem-solving capacities than those with lower resilience levels [17,18]. Studies have shown that cancer patients possessing elevated resilience levels tend to experience diminished psychological distress throughout their illness [19]. Studies have also revealed that psychological resilience mediates stress and quality of life for cancer patients. During the cancer trajectory, individuals frequently confront psychological and emotional hurdles [14]. Although resilience has historically been conceptualized as a relatively stable personal trait, contemporary perspectives increasingly emphasize its context-sensitive and dynamic nature, particularly in the face of chronic illness such as cancer. Measures such as the CD-RISC-10 capture individuals’ perceived adaptive capacity under current life circumstances rather than immutable personality characteristics. In this sense, resilience can be understood as a relatively stable psychological resource that remains sensitive to situational demands, making it theoretically appropriate to examine its associations with process-oriented constructs such as psychological flexibility.

Cancer patients with lower psychological resilience have been found to experience lower body image, quality of life, and higher levels of intense disease symptoms [20]. With cancer, people may engage in fewer behavioral activities and social relationships [21]. Individual factors and social relationships are among the factors that may negatively affect the psychological resilience of cancer patients [22]. Social isolation has been observed especially in people with prostate, lung, and breast cancers [23,24,25].

According to the broaden and build theory developed by Frederickson [26], positive emotions (such as friendship or happiness) can also activate a person’s behavior. For example, interacting with a stranger may lead to a new friendship. Thus, this situation can make a positive contribution to the person’s psychological resilience levels [27]. At this point, it is thought that when psychological resilience increases, factors such as living with values, values and committed action, being present, and acceptance, which are among the factors that constitute psychological flexibility, will also increase [28,29].

The concept of psychological resilience, which refers to one’s ability to cope with life’s challenges, is closely related to psychological flexibility [20]. The term psychological flexibility refers to the ability to cope with challenging situations while staying committed to one’s goals and values [21]. Within acceptance- and mindfulness-based frameworks, psychological flexibility is understood as a multidimensional construct encompassing acceptance of internal experiences, present-moment awareness, and engagement in value-consistent behavior. These dimensions enable individuals to remain functionally engaged in life despite distress, rather than attempting to control or avoid difficult thoughts and emotions [30]. Although psychological resilience and psychological flexibility are closely related constructs, they remain conceptually distinct. Psychological resilience refers to the capacity to recognize, mobilize, and flexibly utilize internal and external resources in response to situational, cultural, and contextual demands when encountering adversity [15]. In this sense, resilience reflects a broader adaptive capacity that enables sustained engagement with challenging life circumstances and effective coping across prolonged stressors, such as cancer. In contrast, psychological flexibility describes a moment-to-moment, context-sensitive regulatory process that reflects how individuals relate to their internal experiences rather than how they control them [31]. It encompasses openness to internal experiences, present-moment awareness, and engagement in value-guided committed action, even in the presence of distress. Accordingly, while resilience represents an overarching capacity for adaptation, psychological flexibility constitutes a core process through which this capacity is enacted in everyday functioning, particularly under conditions of psychological strain.

It is known that psychological flexibility, which is associated with psychological resilience, plays a crucial role in the relationship between disease symptoms and patient functionality in individuals with chronic pain [22]. Psychological flexibility, a factor in psychotherapy for cancer patients, is studied in acceptance and commitment therapies and cognitive behavioral therapies [23,24]. It is aimed to increase the psychological flexibility levels of cancer patients experiencing psychological difficulties during the psychological treatment process [25]. Considering the studies, it is thought that psychological flexibility may be an important factor between psychological resilience and mental health. In this context, the study aimed to reveal the mediating role of psychological flexibility in the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health.

H1.

Psychological resilience in cancer patients significantly affects their psychological flexibility.

H2.

Psychological flexibility in cancer patients significantly affects their mental health.

H3.

Psychological flexibility mediates the interaction between psychological resilience by cancer patients and mental health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Procedure

The research was conducted face-to-face with 234 cancer patients at Gaziantep University Hospital and living in Turkey. The mean age of the participants was 34.95 years (SD = 13.499; range 18–64), and the majority were female (149 females and 85 men). Potentially eligible participants were identified by the trainee psychologist during the hospital visit. Potentially eligible participants were defined as individuals aged 18 years or older who had received a cancer diagnosis, were cognitively able to complete self-report questionnaires, and voluntarily agreed to participate in the study. Patients with severe cognitive impairment or acute psychiatric conditions that could interfere with informed consent or questionnaire completion were not included. In parallel, psychology students voluntarily supported the researchers in the data collection process. Participants were informed about the study before starting any procedures. Informed consent was signed by participants who agreed to participate. Participants were asked to contact us if they had any questions. Their demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained through their statements. Patients were asked questions such as age, gender, previous/current psychiatric treatment, and whether they had received chemotherapy.

2.2. Sample Size Determination

The sample size required for this study was determined using G*Power 3.1 (Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) software [32]. A priori power analysis indicated that a minimum of 68 participants would be sufficient to detect medium effect sizes (f2 = 0.15) with a power of 0.80 and α = 0.05 in a model with two predictors. Given that the study included 234 participants, the sample size was considered adequate for the planned regression-based path analyses.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used to measure mental health. DASS-21 is a self-report scale developed by Lovibond and Lovibond to assess the presence and severity of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in the past week [33]. The Turkish version of the scale consists of 21 items [34], three subscales (depression, anxiety, and stress), and a four-point Likert scoring system (0: Never and 3: Always) [27]. High scores indicate that the person’s emotions are intense for the relevant sub-dimension. The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficients for the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales are 0.89, 0.87, and 0.90, respectively. The total Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient for this study was calculated as 0.93. For this study, the total score Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficients were calculated as 0.94.

2.3.2. Psychological Resilience

The abbreviated version of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale–Short Form (CD-RISC-10), consisting of 10 items derived from the original 25-item scale, was used to assess psychological resilience [28,29]. Kaya and Odacı adapted the scale to Turkish culture, and the internal consistency coefficient was 0.81 [35]. The scale consisted of 10 items and a 5-point Likert scale, with 0 “not true” and 4 “Always true”, in the Turkish validity and reliability study. High scores indicate a high level of psychological resilience. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability was found to be 0.89.

2.3.3. Psychological Flexibility

Francis [36] developed this scale [37]. The original version of the scale consists of 23 items and includes three sub-dimensions (openness to experience, behavioral awareness, and valuing action). The Turkish version of the Psychological Flexibility (PF) scale is a 28-item, seven-point Likert-type measure consisting of five subscales (values and committed action, self-as-context, cognitive defusion, contact with the present moment, and acceptance). The items were rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). High scores refer to high levels of presence of psychological flexibility (Cronbach’s α = 0.79). The adaptation of the scale into Turkish was carried out by Karakuş and Akbay [38]. For this study, the total score Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficients were calculated as 0.66.

2.4. Control Variables

Five control variables are used in this study. Age, gender, relapse, receiving chemotherapy, and work experience were included as control variables during the analyses because they were significantly related to the mental health of cancer patients.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alphas, and correlations using SPSS 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for major variables, including means and standard deviations. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess correlations among psychological resilience, psychological flexibility, and mental health. Regression-based path analysis using maximum likelihood estimation via AMOS 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was conducted to examine our main research hypotheses regarding the mediating effect of psychological flexibility on the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health.

In the model, age, gender, relapse status, chemotherapy status, and work experience were included as control variables, as previous research suggests these factors may significantly influence the mental health of cancer patients. These variables were added to the model to account for potential confounding effects and increase the accuracy of the mediation analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Results

Of the total sample (N = 234), 63.7% were women and 36.3% were men. In terms of employment status, 61.1% were not working, while 38.9% were employed. Regarding treatment status, 41.9% were receiving chemotherapy, and 58.1% were not. Additionally, 23.6% of the participants had experienced a relapse, whereas 76.4% had not. When it comes to psychological support, 83.3% were currently receiving psychological support, and 16.7% were not. A total of 66.2% had received psychological support in the past, while 33.8% had not.

3.2. Correlation Analysis Between the Variables and Descriptive Statistics

In this part of the study, the psychological flexibility, psychological resilience, and mental health means, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis values of the variables and correlations are calculated, and the obtained values are briefly summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s r correlations among psychological resilience, psychological flexibility (total and subdimensions), and depression, anxiety, and stress variables (N = 234).

The results of descriptive, reliability, and correlational analyses are shown in Table 1. The distribution was evaluated in terms of kurtosis and skewness values; a normal curve appeared [39]. The correlation analysis revealed a positive association between psychological resilience and psychological flexibility (r = 0.484, p < 0.01), valued living (r = 0.669, p < 0.01), defusion (r = 0.482, p < 0.01), and self as context (r = 0.588, p < 0.01). It means increasing psychological resilience of cancer patients was related to more psychological flexibility and valued living, defusion, and self as context, which are psychological flexibility components. Psychological resilience was correlated negatively with acceptance (r = −0.480, p < 0.01) and contact with the present moment (r = −0.218, p < 0.01). In addition, psychological resilience and psychological flexibility were also correlated with depression, anxiety, and stress negatively (r = −0.193, p < 0.01; r = −0.355, p < 0.01), implying that the more psychological resilience and psychological flexibility of cancer patients progress, the stronger their mental health they are. Depression, anxiety, and stress was negatively correlated with valued living (r = −0.175, p < 0.01), contact with present moment (r = −0.333, p < 0.01), self as context (r = −0.129, p < 0.05) but were not significantly correlated with acceptance (r = 0.036, p < 0.05) and defusion (r = −0.007, p > 0.05).

3.3. Path Analysis

A regression-based path analysis was conducted using AMOS 25 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to test the proposed mediation model. Resilience, psychological flexibility, depression, anxiety, and stress were included as observed variables, operationalized using total scores from their respective scales. Gender and work experience were included as observed exogenous variables. Indirect effects were tested using Model 4 with 1000 bootstrap samples, and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals were computed. Unstandardized estimates of indirect effects were −0.254 and −0.085 for psychological flexibility (see Table 2). Confidence intervals that did not include zero were interpreted as indicating statistically significant mediation effects.

Table 2.

Direct effects.

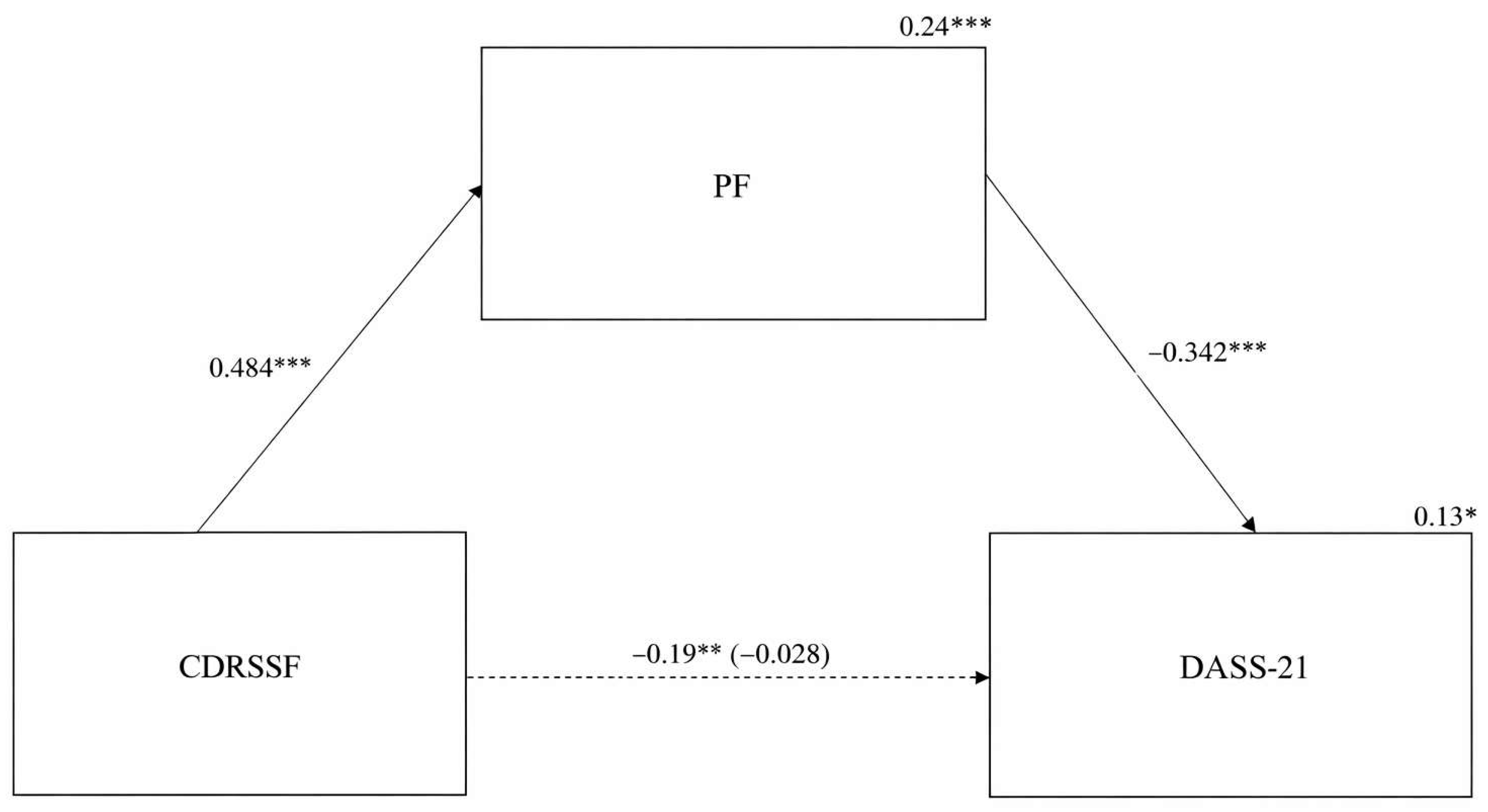

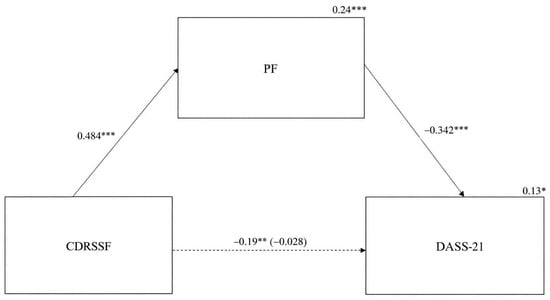

Hypothesis 1 (H1) proposed that psychological resilience would be positively associated with psychological flexibility of cancer patients. The results revealed that psychological resilience had a total effect on psychological flexibility, B = 0.913, SE = 0.108, β = 0.484, p < 0.001; H1 was supported.

Hypothesis 2 (H2) proposed that psychological flexibility would be negatively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress in cancer patients. The results revealed that psychological flexibility had a total effect on depression, anxiety, and stress, B = −0.284, SE = 0.058, β = −0.342, p < 0.001. H2 was also supported.

Hypothesis 3 (H3) proposed that psychological flexibility would mediate the relationship between psychological resilience of cancer patients and their mental health (β = −0.166, p < 0.01). The fact that the estimate for the direct path from psychological resilience to mental health decreased to B = −0.043, SE = 0.109, β = −0.028, p > 0.05 after accounting for the indirect effects reflects full mediation, thus supporting H3. The amount of variance of mental health accounted for by the model was 13%. The proportion of mediation was 16%. The results obtained as a result of the analysis are given in Table 2 and Table 3, and the model is given in Figure 1. The total effect of psychological resilience on mental health was statistically significant (B = −0.30, SE = 0.100, β = −0.193, p < 0.01), with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −0.501 to −0.104.

Table 3.

Indirect effect (1000 boostrap).

Figure 1.

The relationship between psychological resilience and depression, anxiety, and stress (mental health) in cancer patients is mediated by their psychological flexibility. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, CDRSF = psychological resilience, PF = psychological flexibility, DASS-21 = depression, anxiety, and stress (mental health).

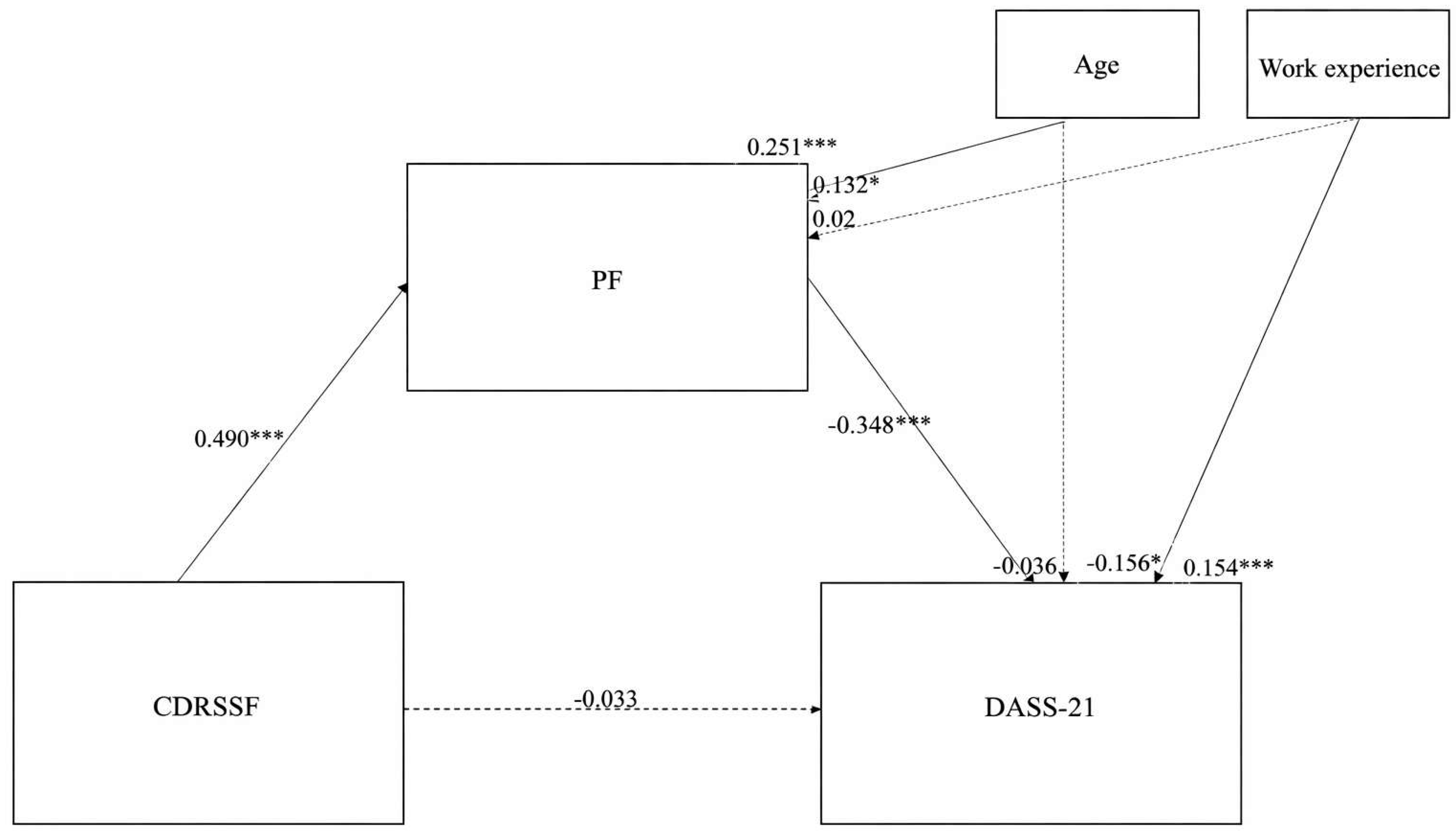

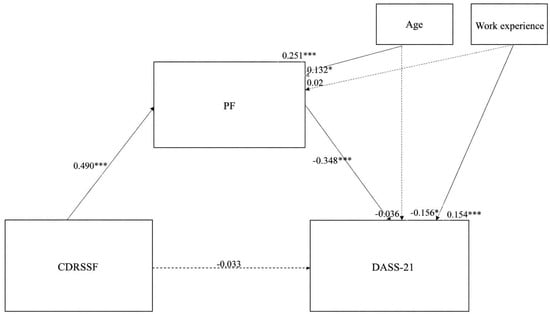

We drew a second path model that examined the mediating role of psychological resilience on mental health when controlled for age and work experience. Studies regard age and work experience as confounding variables [33]. Figure 2 shows the final path model, indicating that psychological flexibility was still a full mediator between psychological resilience and mental health, holding other variables constant. The amount of variance of mental health accounted for by the model was 15%. The proportion of mediation was 17%.

Figure 2.

Final path model for the mediating effect of psychological flexibility on mental health. *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05; CDRSSF = psychological resilience; PF = psychological flexibility; DASS-21 = depression, anxiety, and stress (mental health).

4. Discussion

A particular interest of the present study is whether psychological flexibility might serve as a factor contributing to the positive effects of psychological resilience on cancer patients’ mental health. The relationship between psychological flexibility and resilience can be better understood through the lens of ACT and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. ACT conceptualizes psychological flexibility as the ability to stay in contact with the present moment, regardless of unpleasant thoughts or emotions, while engaging in behavior consistent with personal values [39]. This flexibility enables individuals to adapt to adversity, a core component of resilience. Resilience, in turn, reflects one’s capacity to recover from or adapt positively to significant sources of stress [40]. From a theoretical perspective, psychological resilience can be conceptualized as a distal personal resource reflecting individuals’ general capacity to withstand and adapt to adversity, whereas psychological flexibility represents a proximal, process-oriented mechanism through which this adaptive capacity is enacted in daily life. Within the acceptance and commitment therapy framework, psychological flexibility involves moment-to-moment regulatory processes—such as acceptance, present-moment awareness, and values-based action—that directly shape responses to stress. Similarly, the broaden-and-build theory suggests that broader adaptive resources facilitate flexible behavioral repertoires over time. In this sense, resilience provides the foundational conditions that enable psychological flexibility to operate as a mechanism linking resilience to mental health outcomes. From a theoretical standpoint, resilience may serve as a foundational resource that facilitates flexible engagement with life challenges, while psychological flexibility acts as a dynamic process through which resilient functioning is enacted [41,42]. Findings from the path analysis show that psychological resilience directly predicts psychological flexibility and mental health. In addition, psychological resilience predicts mental health through the mediation of psychological flexibility. According to current results, psychological flexibility has a full mediator role in the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health. Consequently, findings of this study support the important role of psychological flexibility in explaining the association between psychological resilience and mental health and strengthening the positive effects of it on mental health in cancer patients.

In addition to many studies indicating the relationship between psychological resilience and psychological flexibility [22,43], these results support that psychological resilience is a significant predictor of psychological flexibility. That is, cancer patients who experience higher levels of psychological resilience have higher levels of psychological flexibility. Surviving and adapting to this process during difficult times, such as cancer illness, requires strong psychological resilience and psychological flexibility [19,40]. In the face of adverse life events, people tend to behave in a value-guided manner by using the other processes of psychological flexibility, such as acceptance, cognitive defusion, contact with the present moment, and self-as-context [21].

Cancer patients suffered from more distress and depression [14], hopelessness, fear of death [25], cancer-related fatigue [44] and exhibited poorer social adjustment than people without cancer [35]. Trying to avoid these feelings and thoughts, instead of accepting (embracing even negative experiences) them, is associated with low psychological flexibility [36]. In a study of adolescent cancer survivors, use of acceptance coping strategies, as opposed to avoidance coping strategies, predicted better well-being 2–10 years after cancer treatment [38]. So, these results support that higher psychological flexibility is a significant predictor of mental health. In order not to be preoccupied with negative thoughts for a long time, not to allow thoughts to control behavior, to connect with the present moment without ruminating, and to continue to live a value-oriented life, a high level of psychological flexibility is required [23,32], which is beneficial for mental health [45,46]. Value-oriented living will help people to experience positive emotions more often and increase their behavioral activation, which will help to protect mental health [47,48,49,50]. Research shows that cancer patients who value-oriented living have better mental health [51,52,53].

Psychological flexibility skills have been improved to strengthen the mental health of cancer patients [36,54,55]. In addition, Pellerin [42] suggested that the need for psychological flexibility was a part of the system that human beings use to both regulate their behavior and cope with difficult times [56]. Low psychological resilience causes difficulty in accepting one’s challenging emotions, difficulty in staying in the moment, excessive rumination, and moving away from a value-oriented life [26]. In this sense, the fact that psychological flexibility is related to these skills will help cancer patients to survive the difficult process by supporting their mental health. These results show that in situations where psychological resilience is low, if the individual’s psychological flexibility is high, the individual’s mental health may not be negatively affected.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

This study boasts a large sample of people with cancer and a range of years since their diagnosis occurred. These findings support growing evidence that psychological flexibility and a related set of skills can enhance life after cancer. Despite the promising results reviewed above, the current study is not without limitations. It is important to consider that the participants in our sample were predominantly female (i.e., 63.7%). This raises a concern regarding the generalizability of results to the broader general population. To avoid a gender-related bias, we examined gender differences in all variables in our study and found no significant differences. Another limitation is the study’s cross-sectional design, which enabled us to collect data of only a specific moment of participants’ experiences rather than follow processes over time. It would be profitable to conduct longitudinal research to provide further support for our suggested model and, consequently, target the enhancement of psychological flexibility to reduce psychological distress. Since it is quantitative research, a mixed-method research design can be used to examine the relationships of variables in more depth. In this study, cancer type and stage variables were not included. The focus of this study is to examine the effect of psychological flexibility on psychological resilience and mental health in the general cancer population. By excluding data on cancer type and stage, the researchers avoided complications, such as the need for a larger sample size. Notably, the effects of psychological flexibility may differ among different cancer types and stages, which could be considered an important area of investigation for future research. Finally, the Cronbach’s alpha value of the psychological flexibility scale was below 0.70. Considering that it was 0.79 in the original form, it can be thought that there is a need to develop a new psychological flexibility scale suitable for Turkish culture. Alternatively, a psychological flexibility scale can be developed for patients with cancer. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the defusion subscale of the Psychological Flexibility Scale was found to be 0.534. Although this value appears relatively low, it is consistent with the original validation study of the scale, in which the defusion subscale also demonstrated limited internal consistency (α = 0.59; [38]). This suggests that the lower reliability is not unique to the current sample but may be attributed to the structural characteristics of the subscale itself. Specifically, the items within the defusion dimension may be less homogeneous, which can result in reduced internal consistency. Therefore, this finding should be interpreted in the context of the known psychometric limitations of this particular subscale. Another limitation concerns the non-random, convenience sampling from a clinical setting, which may have caused self-selection bias and reduced the generalizability of the findings. Given the cross-sectional design of the present study, causal conclusions regarding the directionality of the observed relationships cannot be drawn. Although the proposed mediation model is theoretically grounded, alternative directional or reciprocal relationships among resilience, psychological flexibility, and mental health are also plausible. Future longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the temporal ordering of these constructs. Furthermore, the model explained 13% to 15% of the variance in mental health, suggesting that while psychological flexibility is a key mechanism, other unmeasured psychosocial factors also play a role in the complex mental health outcomes of cancer patients.

In addition, the constructs examined in this study—psychological resilience, psychological flexibility, and mental health—are dynamic and conceptually interrelated. Therefore, the observed associations may reflect reciprocal or evolving processes rather than strictly unidirectional effects. Given the correlational nature of the design, it is possible that changes in mental health or psychological flexibility also influence resilience over time. Future longitudinal research is needed to examine these dynamic and bidirectional relationships more clearly.

4.2. Clinical Implications

While our findings are based on cross-sectional data, they suggest that screening for psychological flexibility levels could potentially inform the development of tailored intervention programs, which aim to reduce the negative effects of low psychological resilience on mental health. Future intervention frameworks might consider incorporating strategies such as values exploration and mindfulness to potentially mitigate the impact of lower resilience on mental health. Moreover, the effective intervention programs should focus on how difficult times experienced are associated with a client’s psychological flexibility and mental health. In addition, acceptance and commitment therapy may be particularly appropriate for cancer patients in clinical settings. ACT uses mindfulness training both to reduce stress and to achieve acceptance, appropriate contact with the present moment, defusion, and self as context. Thus, ACT may address a broader range of distress processes and outcomes than other intervention frameworks [25].

5. Conclusions

The current study suggests that psychological flexibility fully mediates the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health. Psychological flexibility plays an important role in reintegrating people with a cancer diagnosis. Not only can mental health professionals improve coping abilities for these individuals, but clinicians can also work with their clients to improve their ability to live a value-oriented life and enable them to accept the positive and negative experiences that will come from diagnosis.

Author Contributions

Methodology, F.T.; Formal analysis, C.B. and F.T.; Investigation, C.B; Resources, C.B; Writing—original draft, F.T.; Writing—review & editing, C.B and F.T.; Visualization, F.T.; Project administration, F.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hasan Kalyoncu University (protocol E-97105791-050.01.01-38698, 2023-07-14).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical restrictions related to the sensitivity of clinical and mental health data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Berlinger, N.; Gusmano, M. Cancer Chronicity: New Research and Policy Challenges. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2011, 16, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Soylu, C. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Cancer Patients. Psikiyatr. Guncel Yaklasimlar/Curr. Approaches Psychiatry 2014, 6, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, M.J.; Riba, M.B.; Spiegel, D. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Cancer. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fafouti, M.; Paparrigopoulos, T.; Zervas, Y.; Rabavilas, A.; Malamos, N.; Liappas, I.; Tzavara, C. Depression, Anxiety and General Psychopathology in Breast Cancer Patients: A Cross-Sectional Control Study. In Vivo 2010, 24, 803–810. [Google Scholar]

- Forni, V.; Stiefel, F.; Krenz, S.; Gholam Rezaee, M.; Leyvraz, S.; Ludwig, G. Alexithymie et psychopathologie de patients atteints de cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2011, 5, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorato, D.B.; Osório, F.L. Coping, Psychopathology, and Quality of Life in Cancer Patients under Palliative Care. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradelos, E.C.; Latsou, D.; Mitsi, D.; Tsaras, K.; Lekka, D.; Lavdaniti, M.; Tzavella, F.; Papathanasiou, I.V. Assessment of the Relation between Religiosity, Mental Health, and Psychological Resilience in Breast Cancer Patients. Contemp. Oncol. Onkol. 2018, 22, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, O.; Theorell, T.; Norming, U.; Perski, A.; Öhström, M.; Nyman, C.R. Psychological Reactions in Men Screened for Prostate Cancer. Br. J. Urol. 1995, 75, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, K.; Glimelius, B. Psychological Reactions in Newly Diagnosed Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients. Acta Oncol. 1997, 36, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, D.K.; Sullivan, M.D.; Massie, M.J. Women’s Psychological Reactions to Breast Cancer. In Seminars in Oncology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 23, pp. 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, A.D.; Bonanno, G.A. Predictors and Parameters of Resilience to Loss: Toward an Individual Differences Model. J. Pers. 2009, 77, 1805–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, A.; Jenewein, J. Resilience in Cancer Patients. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. The Social Ecology of Resilience: Addressing Contextual and Cultural Ambiguity of a Nascent Construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.O.; Masten, A.S.; Narayan, A.J. Resilience Processes in Development: Four Waves of Research on Positive Adaptation in the Context of Adversity. In Handbook of Resilience in Children; Goldstein, S., Brooks, R.B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.-A.; Yoon, S.; Lee, C.-U.; Chae, J.-H.; Lee, C.; Song, K.-Y.; Kim, T.-S. Psychological Resilience Contributes to Low Emotional Distress in Cancer Patients. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2469–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, J. Health Psychology. In Health Studies; Naidoo, J., Wills, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 157–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjemdal, O.; Friborg, O.; Stiles, T.C.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Martinussen, M. Resilience Predicting Psychiatric Symptoms: A Prospective Study of Protective Factors and Their Role in Adjustment to Stressful Life Events. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 13, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristevska-Dimitrovska, G.; Filov, I.; Rajchanovska, D.; Stefanovski, P.; Dejanova, B. Resilience and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Hao, G.; Wu, M.; Hou, L. Social Isolation in Adults with Cancer: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 973640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. Resilience across Cultures. Br. J. Soc. Work 2008, 38, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettridge, K.A.; Bowden, J.A.; Chambers, S.K.; Smith, D.P.; Murphy, M.; Evans, S.M.; Roder, D.; Miller, C.L. “Prostate Cancer Is Far More Hidden…”: Perceptions of Stigma, Social Isolation and Help-Seeking among Men with Prostate Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashi, N.; Kataoka, Y.; Takemura, T.; Shirakawa, C.; Okazaki, K.; Sakurai, A.; Imakita, T.; Ikegaki, S.; Matsumoto, H.; Saito, E. Factors Influencing Social Isolation and Loneliness among Lung Cancer Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 7141–7145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudjawu, S.; Agyeman-Yeboah, J. Experiences of Women with Breast Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Study at Ho Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 3161–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Branigan, C. Positive Emotions Broaden the Scope of Attention and Thought-action Repertoires. Cogn. Emot. 2005, 19, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentili, C.; Rickardsson, J.; Zetterqvist, V.; Simons, L.E.; Lekander, M.; Wicksell, R.K. Psychological Flexibility as a Resilience Factor in Individuals with Chronic Pain. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.E.; Ciarrochi, J.; Heaven, P.C.L. Relationships between Valued Action and Well-Being across the Transition from High School to Early Adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, Processes and Outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackledge, J.T.; Hayes, S.C. Emotion Regulation in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 57, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales; Psychology Foundation of Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sariçam, H. The Psychometric Properties of Turkish Version of Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) in Health Control and Clinical Samples. J. Cogn. Behav. Psychother. Res. 2018, 7, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, F.; Odaci, H. The Adaptation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale Short Form into Turkish: A Validity and Reliability Study. HAYEF J. Educ. 2021, 18, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.W.; Dawson, D.L.; Golijani-Moghaddam, N. The Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Processes (CompACT). J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2016, 5, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, J.A.; Zautra, A.J. Psychological Resilience, Pain Catastrophizing, and Positive Emotions: Perspectives on Comprehensive Modeling of Individual Pain Adaptation. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2013, 17, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakuş, S.; Akbay, S.E. Psikolojik Esneklik Ölçeği: Uyarlama, Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. Mersin Üniversit. Eğitim Fakült. Dergisi 2020, 16, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.; Wilson, K.G. Association for Contextual Behavioral Science; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Stein, M.B. Psychometric Analysis and Refinement of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item Measure of Resilience. J. Trauma. Stress 2007, 20, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, J.J.; Moore, K.A. Psychological Flexibility: Positive Implications for Mental Health and Life Satisfaction. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellerin, N.; Raufaste, E.; Corman, M.; Teissedre, F.; Dambrun, M. Mental Health Trajectories during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Evidence for Resilience and the Role of Psychological Resources and Flexibility. Sci. Rep. 2021, 12, 10674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.; Boysan, M.; Kefeli, M.C. Psychometric Properties of the Turkish Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2018, 46, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sevier-Guy, L.; Ferreira, N.; Somerville, C.; Gillanders, D. Psychological Flexibility and Fear of Recurrence in Prostate Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Ray-Sannerud, B.; Heron, E.A. Psychological Flexibility as a Dimension of Resilience for Posttraumatic Stress, Depression, and Risk for Suicidal Ideation among Air Force Personnel. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2015, 4, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Assessing Normal Distribution (2) Using Skewness and Kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Doorenbos, A.Z.; Jang, M.K.; Hershberger, P.E. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Adult Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Model. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, S.; Suzuki, K.; Ito, Y.; Fukawa, A. Factors Related to the Resilience and Mental Health of Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3471–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R. ACT Made Simple: An Easy-to-Read Primer on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, C.G.; Howard, S.C.; Bouffet, E.; Pritchard-Jones, K. Science and Health for All Children with Cancer. Science 2019, 363, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, G.; Li, Y.; Xu, R.; Li, P. Resilience and Positive Affect Contribute to Lower Cancer-related Fatigue among Chinese Patients with Gastric Cancer. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e1412–e1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.L.; Pakenham, K.I. The Role of Psychological Flexibility in Palliative Care. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 24, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Sack, A.M.; Menna, R.; Setchell, S.R. Posttraumatic Growth, Coping Strategies, and Psychological Distress in Adolescent Survivors of Cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 29, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L.M.; Badinlou, F.; Buhrman, M.; Brocki, K.C. The Role of Psychological Flexibility in the Context of COVID-19: Associations with Depression, Anxiety, and Insomnia. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 19, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the JMMS. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.